- RMIT Australia

- RMIT Europe

- RMIT Vietnam

- RMIT Global

- RMIT Online

- Alumni & Giving

- What will I do?

- What will I need?

- Who will help me?

- About the institution

- New to university?

- Studying efficiently

- Time management

- Mind mapping

- Note-taking

- Reading skills

- Argument analysis

- Preparing for assessment

Critical thinking and argument analysis

- Online learning skills

- Starting my first assignment

- Researching your assignment

- What is referencing?

- Understanding citations

- When referencing isn't needed

- Paraphrasing

- Summarising

- Synthesising

- Integrating ideas with reporting words

- Referencing with Easy Cite

- Getting help with referencing

- Acting with academic integrity

- Artificial intelligence tools

- Understanding your audience

- Writing for coursework

- Literature review

- Academic style

- Writing for the workplace

- Spelling tips

- Writing paragraphs

- Writing sentences

- Academic word lists

- Annotated bibliographies

- Artist statement

- Case studies

- Creating effective poster presentations

- Essays, Reports, Reflective Writing

- Law assessments

- Oral presentations

- Reflective writing

- Art and design

- Critical thinking

- Maths and statistics

- Sustainability

- Educators' guide

- Learning Lab content in context

- Latest updates

- Students Alumni & Giving Staff Library

Learning Lab

Getting started at uni, study skills, referencing.

- When referencing isn't needed

- Integrating ideas

Writing and assessments

- Critical reading

- Poster presentations

- Postgraduate report writing

Subject areas

For educators.

- Educators' guide

Content in this section

- Introduction to critical thinking

- Finding sources

- Analysing an argument

- Logical fallacies

- Risk Assessment Matrix

- Engaging critically with social media

Critical thinking is an essential skill for succeeding in your studies, and life. These tutorials will take you from understanding the basics of critical thinking, refining your research skills and finally analysing your sources.

Image: melita/stock.adobe.com

Still can't find what you need?

The RMIT University Library provides study support , one-on-one consultations and peer mentoring to RMIT students.

- Facebook (opens in a new window)

- Twitter (opens in a new window)

- Instagram (opens in a new window)

- Linkedin (opens in a new window)

- YouTube (opens in a new window)

- Weibo (opens in a new window)

- Copyright © 2024 RMIT University |

- Accessibility |

- Learning Lab feedback |

- Complaints |

- ABN 49 781 030 034 |

- CRICOS provider number: 00122A |

- RTO Code: 3046 |

- Open Universities Australia

Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking

(10 reviews)

Matthew Van Cleave, Lansing Community College

Copyright Year: 2016

Publisher: Matthew J. Van Cleave

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by "yusef" Alexander Hayes, Professor, North Shore Community College on 6/9/21

Formal and informal reasoning, argument structure, and fallacies are covered comprehensively, meeting the author's goal of both depth and succinctness. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

Formal and informal reasoning, argument structure, and fallacies are covered comprehensively, meeting the author's goal of both depth and succinctness.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

The book is accurate.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

While many modern examples are used, and they are helpful, they are not necessarily needed. The usefulness of logical principles and skills have proved themselves, and this text presents them clearly with many examples.

Clarity rating: 5

It is obvious that the author cares about their subject, audience, and students. The text is comprehensible and interesting.

Consistency rating: 5

The format is easy to understand and is consistent in framing.

Modularity rating: 5

This text would be easy to adapt.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The organization is excellent, my one suggestion would be a concluding chapter.

Interface rating: 5

I accessed the PDF version and it would be easy to work with.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

The writing is excellent.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

This is not an offensive text.

Reviewed by Susan Rottmann, Part-time Lecturer, University of Southern Maine on 3/2/21

I reviewed this book for a course titled "Creative and Critical Inquiry into Modern Life." It won't meet all my needs for that course, but I haven't yet found a book that would. I wanted to review this one because it states in the preface that it... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

I reviewed this book for a course titled "Creative and Critical Inquiry into Modern Life." It won't meet all my needs for that course, but I haven't yet found a book that would. I wanted to review this one because it states in the preface that it fits better for a general critical thinking course than for a true logic course. I'm not sure that I'd agree. I have been using Browne and Keeley's "Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking," and I think that book is a better introduction to critical thinking for non-philosophy majors. However, the latter is not open source so I will figure out how to get by without it in the future. Overall, the book seems comprehensive if the subject is logic. The index is on the short-side, but fine. However, one issue for me is that there are no page numbers on the table of contents, which is pretty annoying if you want to locate particular sections.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

I didn't find any errors. In general the book uses great examples. However, they are very much based in the American context, not for an international student audience. Some effort to broaden the chosen examples would make the book more widely applicable.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

I think the book will remain relevant because of the nature of the material that it addresses, however there will be a need to modify the examples in future editions and as the social and political context changes.

Clarity rating: 3

The text is lucid, but I think it would be difficult for introductory-level students who are not philosophy majors. For example, in Browne and Keeley's "Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking," the sub-headings are very accessible, such as "Experts cannot rescue us, despite what they say" or "wishful thinking: perhaps the biggest single speed bump on the road to critical thinking." By contrast, Van Cleave's "Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking" has more subheadings like this: "Using your own paraphrases of premises and conclusions to reconstruct arguments in standard form" or "Propositional logic and the four basic truth functional connectives." If students are prepared very well for the subject, it would work fine, but for students who are newly being introduced to critical thinking, it is rather technical.

It seems to be very consistent in terms of its terminology and framework.

Modularity rating: 4

The book is divided into 4 chapters, each having many sub-chapters. In that sense, it is readily divisible and modular. However, as noted above, there are no page numbers on the table of contents, which would make assigning certain parts rather frustrating. Also, I'm not sure why the book is only four chapter and has so many subheadings (for instance 17 in Chapter 2) and a length of 242 pages. Wouldn't it make more sense to break up the book into shorter chapters? I think this would make it easier to read and to assign in specific blocks to students.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The organization of the book is fine overall, although I think adding page numbers to the table of contents and breaking it up into more separate chapters would help it to be more easily navigable.

Interface rating: 4

The book is very simply presented. In my opinion it is actually too simple. There are few boxes or diagrams that highlight and explain important points.

The text seems fine grammatically. I didn't notice any errors.

The book is written with an American audience in mind, but I did not notice culturally insensitive or offensive parts.

Overall, this book is not for my course, but I think it could work well in a philosophy course.

Reviewed by Daniel Lee, Assistant Professor of Economics and Leadership, Sweet Briar College on 11/11/19

This textbook is not particularly comprehensive (4 chapters long), but I view that as a benefit. In fact, I recommend it for use outside of traditional logic classes, but rather interdisciplinary classes that evaluate argument read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

This textbook is not particularly comprehensive (4 chapters long), but I view that as a benefit. In fact, I recommend it for use outside of traditional logic classes, but rather interdisciplinary classes that evaluate argument

To the best of my ability, I regard this content as accurate, error-free, and unbiased

The book is broadly relevant and up-to-date, with a few stray temporal references (sydney olympics, particular presidencies). I don't view these time-dated examples as problematic as the logical underpinnings are still there and easily assessed

Clarity rating: 4

My only pushback on clarity is I didn't find the distinction between argument and explanation particularly helpful/useful/easy to follow. However, this experience may have been unique to my class.

To the best of my ability, I regard this content as internally consistent

I found this text quite modular, and was easily able to integrate other texts into my lessons and disregard certain chapters or sub-sections

The book had a logical and consistent structure, but to the extent that there are only 4 chapters, there isn't much scope for alternative approaches here

No problems with the book's interface

The text is grammatically sound

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

Perhaps the text could have been more universal in its approach. While I didn't find the book insensitive per-se, logic can be tricky here because the point is to evaluate meaningful (non-trivial) arguments, but any argument with that sense of gravity can also be traumatic to students (abortion, death penalty, etc)

No additional comments

Reviewed by Lisa N. Thomas-Smith, Graduate Part-time Instructor, CU Boulder on 7/1/19

The text covers all the relevant technical aspects of introductory logic and critical thinking, and covers them well. A separate glossary would be quite helpful to students. However, the terms are clearly and thoroughly explained within the text,... read more

The text covers all the relevant technical aspects of introductory logic and critical thinking, and covers them well. A separate glossary would be quite helpful to students. However, the terms are clearly and thoroughly explained within the text, and the index is very thorough.

The content is excellent. The text is thorough and accurate with no errors that I could discern. The terminology and exercises cover the material nicely and without bias.

The text should easily stand the test of time. The exercises are excellent and would be very helpful for students to internalize correct critical thinking practices. Because of the logical arrangement of the text and the many sub-sections, additional material should be very easy to add.

The text is extremely clearly and simply written. I anticipate that a diligent student could learn all of the material in the text with little additional instruction. The examples are relevant and easy to follow.

The text did not confuse terms or use inconsistent terminology, which is very important in a logic text. The discipline often uses multiple terms for the same concept, but this text avoids that trap nicely.

The text is fairly easily divisible. Since there are only four chapters, those chapters include large blocks of information. However, the chapters themselves are very well delineated and could be easily broken up so that parts could be left out or covered in a different order from the text.

The flow of the text is excellent. All of the information is handled solidly in an order that allows the student to build on the information previously covered.

The PDF Table of Contents does not include links or page numbers which would be very helpful for navigation. Other than that, the text was very easy to navigate. All the images, charts, and graphs were very clear

I found no grammatical errors in the text.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

The text including examples and exercises did not seem to be offensive or insensitive in any specific way. However, the examples included references to black and white people, but few others. Also, the text is very American specific with many examples from and for an American audience. More diversity, especially in the examples, would be appropriate and appreciated.

Reviewed by Leslie Aarons, Associate Professor of Philosophy, CUNY LaGuardia Community College on 5/16/19

This is an excellent introductory (first-year) Logic and Critical Thinking textbook. The book covers the important elementary information, clearly discussing such things as the purpose and basic structure of an argument; the difference between an... read more

This is an excellent introductory (first-year) Logic and Critical Thinking textbook. The book covers the important elementary information, clearly discussing such things as the purpose and basic structure of an argument; the difference between an argument and an explanation; validity; soundness; and the distinctions between an inductive and a deductive argument in accessible terms in the first chapter. It also does a good job introducing and discussing informal fallacies (Chapter 4). The incorporation of opportunities to evaluate real-world arguments is also very effective. Chapter 2 also covers a number of formal methods of evaluating arguments, such as Venn Diagrams and Propositional logic and the four basic truth functional connectives, but to my mind, it is much more thorough in its treatment of Informal Logic and Critical Thinking skills, than it is of formal logic. I also appreciated that Van Cleave’s book includes exercises with answers and an index, but there is no glossary; which I personally do not find detracts from the book's comprehensiveness.

Overall, Van Cleave's book is error-free and unbiased. The language used is accessible and engaging. There were no glaring inaccuracies that I was able to detect.

Van Cleave's Textbook uses relevant, contemporary content that will stand the test of time, at least for the next few years. Although some examples use certain subjects like former President Obama, it does so in a useful manner that inspires the use of critical thinking skills. There are an abundance of examples that inspire students to look at issues from many different political viewpoints, challenging students to practice evaluating arguments, and identifying fallacies. Many of these exercises encourage students to critique issues, and recognize their own inherent reader-biases and challenge their own beliefs--hallmarks of critical thinking.

As mentioned previously, the author has an accessible style that makes the content relatively easy to read and engaging. He also does a suitable job explaining jargon/technical language that is introduced in the textbook.

Van Cleave uses terminology consistently and the chapters flow well. The textbook orients the reader by offering effective introductions to new material, step-by-step explanations of the material, as well as offering clear summaries of each lesson.

This textbook's modularity is really quite good. Its language and structure are not overly convoluted or too-lengthy, making it convenient for individual instructors to adapt the materials to suit their methodological preferences.

The topics in the textbook are presented in a logical and clear fashion. The structure of the chapters are such that it is not necessary to have to follow the chapters in their sequential order, and coverage of material can be adapted to individual instructor's preferences.

The textbook is free of any problematic interface issues. Topics, sections and specific content are accessible and easy to navigate. Overall it is user-friendly.

I did not find any significant grammatical issues with the textbook.

The textbook is not culturally insensitive, making use of a diversity of inclusive examples. Materials are especially effective for first-year critical thinking/logic students.

I intend to adopt Van Cleave's textbook for a Critical Thinking class I am teaching at the Community College level. I believe that it will help me facilitate student-learning, and will be a good resource to build additional classroom activities from the materials it provides.

Reviewed by Jennie Harrop, Chair, Department of Professional Studies, George Fox University on 3/27/18

While the book is admirably comprehensive, its extensive details within a few short chapters may feel overwhelming to students. The author tackles an impressive breadth of concepts in Chapter 1, 2, 3, and 4, which leads to 50-plus-page chapters... read more

While the book is admirably comprehensive, its extensive details within a few short chapters may feel overwhelming to students. The author tackles an impressive breadth of concepts in Chapter 1, 2, 3, and 4, which leads to 50-plus-page chapters that are dense with statistical analyses and critical vocabulary. These topics are likely better broached in manageable snippets rather than hefty single chapters.

The ideas addressed in Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking are accurate but at times notably political. While politics are effectively used to exemplify key concepts, some students may be distracted by distinct political leanings.

The terms and definitions included are relevant, but the examples are specific to the current political, cultural, and social climates, which could make the materials seem dated in a few years without intentional and consistent updates.

While the reasoning is accurate, the author tends to complicate rather than simplify -- perhaps in an effort to cover a spectrum of related concepts. Beginning readers are likely to be overwhelmed and under-encouraged by his approach.

Consistency rating: 3

The four chapters are somewhat consistent in their play of definition, explanation, and example, but the structure of each chapter varies according to the concepts covered. In the third chapter, for example, key ideas are divided into sub-topics numbering from 3.1 to 3.10. In the fourth chapter, the sub-divisions are further divided into sub-sections numbered 4.1.1-4.1.5, 4.2.1-4.2.2, and 4.3.1 to 4.3.6. Readers who are working quickly to master new concepts may find themselves mired in similarly numbered subheadings, longing for a grounded concepts on which to hinge other key principles.

Modularity rating: 3

The book's four chapters make it mostly self-referential. The author would do well to beak this text down into additional subsections, easing readers' accessibility.

The content of the book flows logically and well, but the information needs to be better sub-divided within each larger chapter, easing the student experience.

The book's interface is effective, allowing readers to move from one section to the next with a single click. Additional sub-sections would ease this interplay even further.

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

Some minor errors throughout.

For the most part, the book is culturally neutral, avoiding direct cultural references in an effort to remain relevant.

Reviewed by Yoichi Ishida, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Ohio University on 2/1/18

This textbook covers enough topics for a first-year course on logic and critical thinking. Chapter 1 covers the basics as in any standard textbook in this area. Chapter 2 covers propositional logic and categorical logic. In propositional logic,... read more

This textbook covers enough topics for a first-year course on logic and critical thinking. Chapter 1 covers the basics as in any standard textbook in this area. Chapter 2 covers propositional logic and categorical logic. In propositional logic, this textbook does not cover suppositional arguments, such as conditional proof and reductio ad absurdum. But other standard argument forms are covered. Chapter 3 covers inductive logic, and here this textbook introduces probability and its relationship with cognitive biases, which are rarely discussed in other textbooks. Chapter 4 introduces common informal fallacies. The answers to all the exercises are given at the end. However, the last set of exercises is in Chapter 3, Section 5. There are no exercises in the rest of the chapter. Chapter 4 has no exercises either. There is index, but no glossary.

The textbook is accurate.

The content of this textbook will not become obsolete soon.

The textbook is written clearly.

The textbook is internally consistent.

The textbook is fairly modular. For example, Chapter 3, together with a few sections from Chapter 1, can be used as a short introduction to inductive logic.

The textbook is well-organized.

There are no interface issues.

I did not find any grammatical errors.

This textbook is relevant to a first semester logic or critical thinking course.

Reviewed by Payal Doctor, Associate Professro, LaGuardia Community College on 2/1/18

This text is a beginner textbook for arguments and propositional logic. It covers the basics of identifying arguments, building arguments, and using basic logic to construct propositions and arguments. It is quite comprehensive for a beginner... read more

This text is a beginner textbook for arguments and propositional logic. It covers the basics of identifying arguments, building arguments, and using basic logic to construct propositions and arguments. It is quite comprehensive for a beginner book, but seems to be a good text for a course that needs a foundation for arguments. There are exercises on creating truth tables and proofs, so it could work as a logic primer in short sessions or with the addition of other course content.

The books is accurate in the information it presents. It does not contain errors and is unbiased. It covers the essential vocabulary clearly and givens ample examples and exercises to ensure the student understands the concepts

The content of the book is up to date and can be easily updated. Some examples are very current for analyzing the argument structure in a speech, but for this sort of text understandable examples are important and the author uses good examples.

The book is clear and easy to read. In particular, this is a good text for community college students who often have difficulty with reading comprehension. The language is straightforward and concepts are well explained.

The book is consistent in terminology, formatting, and examples. It flows well from one topic to the next, but it is also possible to jump around the text without loosing the voice of the text.

The books is broken down into sub units that make it easy to assign short blocks of content at a time. Later in the text, it does refer to a few concepts that appear early in that text, but these are all basic concepts that must be used to create a clear and understandable text. No sections are too long and each section stays on topic and relates the topic to those that have come before when necessary.

The flow of the text is logical and clear. It begins with the basic building blocks of arguments, and practice identifying more and more complex arguments is offered. Each chapter builds up from the previous chapter in introducing propositional logic, truth tables, and logical arguments. A select number of fallacies are presented at the end of the text, but these are related to topics that were presented before, so it makes sense to have these last.

The text is free if interface issues. I used the PDF and it worked fine on various devices without loosing formatting.

1. The book contains no grammatical errors.

The text is culturally sensitive, but examples used are a bit odd and may be objectionable to some students. For instance, President Obama's speech on Syria is used to evaluate an extended argument. This is an excellent example and it is explained well, but some who disagree with Obama's policies may have trouble moving beyond their own politics. However, other examples look at issues from all political viewpoints and ask students to evaluate the argument, fallacy, etc. and work towards looking past their own beliefs. Overall this book does use a variety of examples that most students can understand and evaluate.

My favorite part of this book is that it seems to be written for community college students. My students have trouble understanding readings in the New York Times, so it is nice to see a logic and critical thinking text use real language that students can understand and follow without the constant need of a dictionary.

Reviewed by Rebecca Owen, Adjunct Professor, Writing, Chemeketa Community College on 6/20/17

This textbook is quite thorough--there are conversational explanations of argument structure and logic. I think students will be happy with the conversational style this author employs. Also, there are many examples and exercises using current... read more

This textbook is quite thorough--there are conversational explanations of argument structure and logic. I think students will be happy with the conversational style this author employs. Also, there are many examples and exercises using current events, funny scenarios, or other interesting ways to evaluate argument structure and validity. The third section, which deals with logical fallacies, is very clear and comprehensive. My only critique of the material included in the book is that the middle section may be a bit dense and math-oriented for learners who appreciate the more informal, informative style of the first and third section. Also, the book ends rather abruptly--it moves from a description of a logical fallacy to the answers for the exercises earlier in the text.

The content is very reader-friendly, and the author writes with authority and clarity throughout the text. There are a few surface-level typos (Starbuck's instead of Starbucks, etc.). None of these small errors detract from the quality of the content, though.

One thing I really liked about this text was the author's wide variety of examples. To demonstrate different facets of logic, he used examples from current media, movies, literature, and many other concepts that students would recognize from their daily lives. The exercises in this text also included these types of pop-culture references, and I think students will enjoy the familiarity--as well as being able to see the logical structures behind these types of references. I don't think the text will need to be updated to reflect new instances and occurrences; the author did a fine job at picking examples that are relatively timeless. As far as the subject matter itself, I don't think it will become obsolete any time soon.

The author writes in a very conversational, easy-to-read manner. The examples used are quite helpful. The third section on logical fallacies is quite easy to read, follow, and understand. A student in an argument writing class could benefit from this section of the book. The middle section is less clear, though. A student learning about the basics of logic might have a hard time digesting all of the information contained in chapter two. This material might be better in two separate chapters. I think the author loses the balance of a conversational, helpful tone and focuses too heavily on equations.

Consistency rating: 4

Terminology in this book is quite consistent--the key words are highlighted in bold. Chapters 1 and 3 follow a similar organizational pattern, but chapter 2 is where the material becomes more dense and equation-heavy. I also would have liked a closing passage--something to indicate to the reader that we've reached the end of the chapter as well as the book.

I liked the overall structure of this book. If I'm teaching an argumentative writing class, I could easily point the students to the chapters where they can identify and practice identifying fallacies, for instance. The opening chapter is clear in defining the necessary terms, and it gives the students an understanding of the toolbox available to them in assessing and evaluating arguments. Even though I found the middle section to be dense, smaller portions could be assigned.

The author does a fine job connecting each defined term to the next. He provides examples of how each defined term works in a sentence or in an argument, and then he provides practice activities for students to try. The answers for each question are listed in the final pages of the book. The middle section feels like the heaviest part of the whole book--it would take the longest time for a student to digest if assigned the whole chapter. Even though this middle section is a bit heavy, it does fit the overall structure and flow of the book. New material builds on previous chapters and sub-chapters. It ends abruptly--I didn't realize that it had ended, and all of a sudden I found myself in the answer section for those earlier exercises.

The simple layout is quite helpful! There is nothing distracting, image-wise, in this text. The table of contents is clearly arranged, and each topic is easy to find.

Tiny edits could be made (Starbuck's/Starbucks, for one). Otherwise, it is free of distracting grammatical errors.

This text is quite culturally relevant. For instance, there is one example that mentions the rumors of Barack Obama's birthplace as somewhere other than the United States. This example is used to explain how to analyze an argument for validity. The more "sensational" examples (like the Obama one above) are helpful in showing argument structure, and they can also help students see how rumors like this might gain traction--as well as help to show students how to debunk them with their newfound understanding of argument and logic.

The writing style is excellent for the subject matter, especially in the third section explaining logical fallacies. Thank you for the opportunity to read and review this text!

Reviewed by Laurel Panser, Instructor, Riverland Community College on 6/20/17

This is a review of Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking, an open source book version 1.4 by Matthew Van Cleave. The comparison book used was Patrick J. Hurley’s A Concise Introduction to Logic 12th Edition published by Cengage as well as... read more

This is a review of Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking, an open source book version 1.4 by Matthew Van Cleave. The comparison book used was Patrick J. Hurley’s A Concise Introduction to Logic 12th Edition published by Cengage as well as the 13th edition with the same title. Lori Watson is the second author on the 13th edition.

Competing with Hurley is difficult with respect to comprehensiveness. For example, Van Cleave’s book is comprehensive to the extent that it probably covers at least two-thirds or more of what is dealt with in most introductory, one-semester logic courses. Van Cleave’s chapter 1 provides an overview of argumentation including discerning non-arguments from arguments, premises versus conclusions, deductive from inductive arguments, validity, soundness and more. Much of Van Cleave’s chapter 1 parallel’s Hurley’s chapter 1. Hurley’s chapter 3 regarding informal fallacies is comprehensive while Van Cleave’s chapter 4 on this topic is less extensive. Categorical propositions are a topic in Van Cleave’s chapter 2; Hurley’s chapters 4 and 5 provide more instruction on this, however. Propositional logic is another topic in Van Cleave’s chapter 2; Hurley’s chapters 6 and 7 provide more information on this, though. Van Cleave did discuss messy issues of language meaning briefly in his chapter 1; that is the topic of Hurley’s chapter 2.

Van Cleave’s book includes exercises with answers and an index. A glossary was not included.

Reviews of open source textbooks typically include criteria besides comprehensiveness. These include comments on accuracy of the information, whether the book will become obsolete soon, jargon-free clarity to the extent that is possible, organization, navigation ease, freedom from grammar errors and cultural relevance; Van Cleave’s book is fine in all of these areas. Further criteria for open source books includes modularity and consistency of terminology. Modularity is defined as including blocks of learning material that are easy to assign to students. Hurley’s book has a greater degree of modularity than Van Cleave’s textbook. The prose Van Cleave used is consistent.

Van Cleave’s book will not become obsolete soon.

Van Cleave’s book has accessible prose.

Van Cleave used terminology consistently.

Van Cleave’s book has a reasonable degree of modularity.

Van Cleave’s book is organized. The structure and flow of his book is fine.

Problems with navigation are not present.

Grammar problems were not present.

Van Cleave’s book is culturally relevant.

Van Cleave’s book is appropriate for some first semester logic courses.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Reconstructing and analyzing arguments

- 1.1 What is an argument?

- 1.2 Identifying arguments

- 1.3 Arguments vs. explanations

- 1.4 More complex argument structures

- 1.5 Using your own paraphrases of premises and conclusions to reconstruct arguments in standard form

- 1.6 Validity

- 1.7 Soundness

- 1.8 Deductive vs. inductive arguments

- 1.9 Arguments with missing premises

- 1.10 Assuring, guarding, and discounting

- 1.11 Evaluative language

- 1.12 Evaluating a real-life argument

Chapter 2: Formal methods of evaluating arguments

- 2.1 What is a formal method of evaluation and why do we need them?

- 2.2 Propositional logic and the four basic truth functional connectives

- 2.3 Negation and disjunction

- 2.4 Using parentheses to translate complex sentences

- 2.5 “Not both” and “neither nor”

- 2.6 The truth table test of validity

- 2.7 Conditionals

- 2.8 “Unless”

- 2.9 Material equivalence

- 2.10 Tautologies, contradictions, and contingent statements

- 2.11 Proofs and the 8 valid forms of inference

- 2.12 How to construct proofs

- 2.13 Short review of propositional logic

- 2.14 Categorical logic

- 2.15 The Venn test of validity for immediate categorical inferences

- 2.16 Universal statements and existential commitment

- 2.17 Venn validity for categorical syllogisms

Chapter 3: Evaluating inductive arguments and probabilistic and statistical fallacies

- 3.1 Inductive arguments and statistical generalizations

- 3.2 Inference to the best explanation and the seven explanatory virtues

- 3.3 Analogical arguments

- 3.4 Causal arguments

- 3.5 Probability

- 3.6 The conjunction fallacy

- 3.7 The base rate fallacy

- 3.8 The small numbers fallacy

- 3.9 Regression to the mean fallacy

- 3.10 Gambler's fallacy

Chapter 4: Informal fallacies

- 4.1 Formal vs. informal fallacies

- 4.1.1 Composition fallacy

- 4.1.2 Division fallacy

- 4.1.3 Begging the question fallacy

- 4.1.4 False dichotomy

- 4.1.5 Equivocation

- 4.2 Slippery slope fallacies

- 4.2.1 Conceptual slippery slope

- 4.2.2 Causal slippery slope

- 4.3 Fallacies of relevance

- 4.3.1 Ad hominem

- 4.3.2 Straw man

- 4.3.3 Tu quoque

- 4.3.4 Genetic

- 4.3.5 Appeal to consequences

- 4.3.6 Appeal to authority

Answers to exercises Glossary/Index

Ancillary Material

About the book.

This is an introductory textbook in logic and critical thinking. The goal of the textbook is to provide the reader with a set of tools and skills that will enable them to identify and evaluate arguments. The book is intended for an introductory course that covers both formal and informal logic. As such, it is not a formal logic textbook, but is closer to what one would find marketed as a “critical thinking textbook.”

About the Contributors

Matthew Van Cleave , PhD, Philosophy, University of Cincinnati, 2007. VAP at Concordia College (Moorhead), 2008-2012. Assistant Professor at Lansing Community College, 2012-2016. Professor at Lansing Community College, 2016-

Contribute to this Page

Pursuing Truth: A Guide to Critical Thinking

Chapter 2 arguments.

The fundamental tool of the critical thinker is the argument. For a good example of what we are not talking about, consider a bit from a famous sketch by Monty Python’s Flying Circus : 3

2.1 Identifying Arguments

People often use “argument” to refer to a dispute or quarrel between people. In critical thinking, an argument is defined as

A set of statements, one of which is the conclusion and the others are the premises.

There are three important things to remember here:

- Arguments contain statements.

- They have a conclusion.

- They have at least one premise

Arguments contain statements, or declarative sentences. Statements, unlike questions or commands, have a truth value. Statements assert that the world is a particular way; questions do not. For example, if someone asked you what you did after dinner yesterday evening, you wouldn’t accuse them of lying. When the world is the way that the statement says that it is, we say that the statement is true. If the statement is not true, it is false.

One of the statements in the argument is called the conclusion. The conclusion is the statement that is intended to be proved. Consider the following argument:

Calculus II will be no harder than Calculus I. Susan did well in Calculus I. So, Susan should do well in Calculus II.

Here the conclusion is that Susan should do well in Calculus II. The other two sentences are premises. Premises are the reasons offered for believing that the conclusion is true.

2.1.1 Standard Form

Now, to make the argument easier to evaluate, we will put it into what is called “standard form.” To put an argument in standard form, write each premise on a separate, numbered line. Draw a line underneath the last premise, the write the conclusion underneath the line.

- Calculus II will be no harder than Calculus I.

- Susan did well in Calculus I.

- Susan should do well in Calculus II.

Now that we have the argument in standard form, we can talk about premise 1, premise 2, and all clearly be referring to the same thing.

2.1.2 Indicator Words

Unfortunately, when people present arguments, they rarely put them in standard form. So, we have to decide which statement is intended to be the conclusion, and which are the premises. Don’t make the mistake of assuming that the conclusion comes at the end. The conclusion is often at the beginning of the passage, but could even be in the middle. A better way to identify premises and conclusions is to look for indicator words. Indicator words are words that signal that statement following the indicator is a premise or conclusion. The example above used a common indicator word for a conclusion, ‘so.’ The other common conclusion indicator, as you can probably guess, is ‘therefore.’ This table lists the indicator words you might encounter.

Each argument will likely use only one indicator word or phrase. When the conlusion is at the end, it will generally be preceded by a conclusion indicator. Everything else, then, is a premise. When the conclusion comes at the beginning, the next sentence will usually be introduced by a premise indicator. All of the following sentences will also be premises.

For example, here’s our previous argument rewritten to use a premise indicator:

Susan should do well in Calculus II, because Calculus II will be no harder than Calculus I, and Susan did well in Calculus I.

Sometimes, an argument will contain no indicator words at all. In that case, the best thing to do is to determine which of the premises would logically follow from the others. If there is one, then it is the conclusion. Here is an example:

Spot is a mammal. All dogs are mammals, and Spot is a dog.

The first sentence logically follows from the others, so it is the conclusion. When using this method, we are forced to assume that the person giving the argument is rational and logical, which might not be true.

2.1.3 Non-Arguments

One thing that complicates our task of identifying arguments is that there are many passages that, although they look like arguments, are not arguments. The most common types are:

- Explanations

- Mere asssertions

- Conditional statements

- Loosely connected statements

Explanations can be tricky, because they often use one of our indicator words. Consider this passage:

Abraham Lincoln died because he was shot.

If this were an argument, then the conclusion would be that Abraham Lincoln died, since the other statement is introduced by a premise indicator. If this is an argument, though, it’s a strange one. Do you really think that someone would be trying to prove that Abraham Lincoln died? Surely everyone knows that he is dead. On the other hand, there might be people who don’t know how he died. This passage does not attempt to prove that something is true, but instead attempts to explain why it is true. To determine if a passage is an explanation or an argument, first find the statement that looks like the conclusion. Next, ask yourself if everyone likely already believes that statement to be true. If the answer to that question is yes, then the passage is an explanation.

Mere assertions are obviously not arguments. If a professor tells you simply that you will not get an A in her course this semester, she has not given you an argument. This is because she hasn’t given you any reasons to believe that the statement is true. If there are no premises, then there is no argument.

Conditional statements are sentences that have the form “If…, then….” A conditional statement asserts that if something is true, then something else would be true also. For example, imagine you are told, “If you have the winning lottery ticket, then you will win ten million dollars.” What is being claimed to be true, that you have the winning lottery ticket, or that you will win ten million dollars? Neither. The only thing claimed is the entire conditional. Conditionals can be premises, and they can be conclusions. They can be parts of arguments, but that cannot, on their own, be arguments themselves.

Finally, consider this passage:

I woke up this morning, then took a shower and got dressed. After breakfast, I worked on chapter 2 of the critical thinking text. I then took a break and drank some more coffee….

This might be a description of my day, but it’s not an argument. There’s nothing in the passage that plays the role of a premise or a conclusion. The passage doesn’t attempt to prove anything. Remember that arguments need a conclusion, there must be something that is the statement to be proved. Lacking that, it simply isn’t an argument, no matter how much it looks like one.

2.2 Evaluating Arguments

The first step in evaluating an argument is to determine what kind of argument it is. We initially categorize arguments as either deductive or inductive, defined roughly in terms of their goals. In deductive arguments, the truth of the premises is intended to absolutely establish the truth of the conclusion. For inductive arguments, the truth of the premises is only intended to establish the probable truth of the conclusion. We’ll focus on deductive arguments first, then examine inductive arguments in later chapters.

Once we have established that an argument is deductive, we then ask if it is valid. To say that an argument is valid is to claim that there is a very special logical relationship between the premises and the conclusion, such that if the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true. Another way to state this is

An argument is valid if and only if it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false.

An argument is invalid if and only if it is not valid.

Note that claiming that an argument is valid is not the same as claiming that it has a true conclusion, nor is it to claim that the argument has true premises. Claiming that an argument is valid is claiming nothing more that the premises, if they were true , would be enough to make the conclusion true. For example, is the following argument valid or not?

- If pigs fly, then an increase in the minimum wage will be approved next term.

- An increase in the minimum wage will be approved next term.

The argument is indeed valid. If the two premises were true, then the conclusion would have to be true also. What about this argument?

- All dogs are mammals

- Spot is a mammal.

- Spot is a dog.

In this case, both of the premises are true and the conclusion is true. The question to ask, though, is whether the premises absolutely guarantee that the conclusion is true. The answer here is no. The two premises could be true and the conclusion false if Spot were a cat, whale, etc.

Neither of these arguments are good. The second fails because it is invalid. The two premises don’t prove that the conclusion is true. The first argument is valid, however. So, the premises would prove that the conclusion is true, if those premises were themselves true. Unfortunately, (or fortunately, I guess, considering what would be dropping from the sky) pigs don’t fly.

These examples give us two important ways that deductive arguments can fail. The can fail because they are invalid, or because they have at least one false premise. Of course, these are not mutually exclusive, an argument can be both invalid and have a false premise.

If the argument is valid, and has all true premises, then it is a sound argument. Sound arguments always have true conclusions.

A deductively valid argument with all true premises.

Inductive arguments are never valid, since the premises only establish the probable truth of the conclusion. So, we evaluate inductive arguments according to their strength. A strong inductive argument is one in which the truth of the premises really do make the conclusion probably true. An argument is weak if the truth of the premises fail to establish the probable truth of the conclusion.

There is a significant difference between valid/invalid and strong/weak. If an argument is not valid, then it is invalid. The two categories are mutually exclusive and exhaustive. There can be no such thing as an argument being more valid than another valid argument. Validity is all or nothing. Inductive strength, however, is on a continuum. A strong inductive argument can be made stronger with the addition of another premise. More evidence can raise the probability of the conclusion. A valid argument cannot be made more valid with an additional premise. Why not? If the argument is valid, then the premises were enough to absolutely guarantee the truth of the conclusion. Adding another premise won’t give any more guarantee of truth than was already there. If it could, then the guarantee wasn’t absolute before, and the original argument wasn’t valid in the first place.

2.3 Counterexamples

One way to prove an argument to be invalid is to use a counterexample. A counterexample is a consistent story in which the premises are true and the conclusion false. Consider the argument above:

By pointing out that Spot could have been a cat, I have told a story in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is false.

Here’s another one:

- If it is raining, then the sidewalks are wet.

- The sidewalks are wet.

- It is raining.

The sprinklers might have been on. If so, then the sidewalks would be wet, even if it weren’t raining.

Counterexamples can be very useful for demonstrating invalidity. Keep in mind, though, that validity can never be proved with the counterexample method. If the argument is valid, then it will be impossible to give a counterexample to it. If you can’t come up with a counterexample, however, that does not prove the argument to be valid. It may only mean that you’re not creative enough.

- An argument is a set of statements; one is the conclusion, the rest are premises.

- The conclusion is the statement that the argument is trying to prove.

- The premises are the reasons offered for believing the conclusion to be true.

- Explanations, conditional sentences, and mere assertions are not arguments.

- Deductive reasoning attempts to absolutely guarantee the truth of the conclusion.

- Inductive reasoning attempts to show that the conclusion is probably true.

- In a valid argument, it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false.

- In an invalid argument, it is possible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false.

- A sound argument is valid and has all true premises.

- An inductively strong argument is one in which the truth of the premises makes the the truth of the conclusion probable.

- An inductively weak argument is one in which the truth of the premises do not make the conclusion probably true.

- A counterexample is a consistent story in which the premises of an argument are true and the conclusion is false. Counterexamples can be used to prove that arguments are deductively invalid.

( Cleese and Chapman 1980 ) . ↩︎

- The Key is Being Metacognitive

- The Big Picture

- Learning Outcomes

- Test your Existing Knowledge

- Definitions of Critical Thinking

- Learning How to Think Critically

- Self Reflection Activity

- End of Module Survey

- Test Your Existing Knowledge

- Interpreting Information Methodically

- Using the SEE-I Method

- Interpreting Information Critically

- Argument Analysis

- Learning Activities

- Argument Mapping

- Summary of Anlyzing Arguments

- Fallacious Reasoning

- Statistical Misrepresentation

- Biased Reasoning

- Common Cognitive Biases

- Poor Research Methods - The Wakefield Study

- Summary of How Reasoning Fails

- Misinformation and Disinformation

- Media and Digital Literacy

- Information Trustworthiness

- Summary of How Misinformation is Spread

Critical Thinking Tutorial: Argument Analysis

Good arguments vs poor arguments.

Distinguishing good arguments from bad ones can be challenging because arguments are not always neatly packaged in ways that are easy to understand. Analyzing an argument involves

- identifying the premises and the conclusion,

- thinking objectively about the evidence, and

- determining if the conclusion logically follows from the evidence provided.

A good argument is based on sound reasoning ; it contains evidence that is relevant, reliable, and sufficient to support the conclusion. It also addresses possible counterarguments and does not contain any logical fallacies (fallacies are covered in the next module). In contrast, a bad argument may rely on faulty reasoning, use unreliable or irrelevant evidence, and/or contain logical fallacies. It may also fail to address counterarguments.

This video demonstrates how sound reasoning works when analyzing an argument. It is interactive, so respond to the questions to check your understanding.

Source: How to Argue - Philosophical Reasoning: Crash Course Philosophy by Hank Green on YouTube

Argument Terminology - Drag and Drop Activity

- << Previous: Test Your Existing Knowledge

- Next: Learning Activities >>

- Library A to Z

- Follow on Facebook

- Follow on Twitter

- Follow on YouTube

- Follow on Instagram

The University of Saskatchewan's main campus is situated on Treaty 6 Territory and the Homeland of the Métis.

© University of Saskatchewan Disclaimer | Privacy

- Last Updated: Dec 14, 2023 3:51 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usask.ca/CriticalThinkingTutorial

[A] Argument analysis

An important part of critical thinking is being able to give reasons to support or criticize a position. In this module we learn how to construct and evaluate arguments for this purpose.

- [A01] What is an argument?

- [A02] The standard format

- [A03] Validity

- [A04] Soundness

- [A05] Valid patterns

- [A06] Validity and relevance

- [A07] Hidden Assumptions

- [A08] Inductive Reasoning

- [A09] Good Arguments

- [A10] Argument mapping

- [A11] Analogical Arguments

- [A12] More valid patterns

- [A13] Arguing with other people

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.01: Analysis, Standardization, and Diagramming

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 127545

Thaddeus Robinson

- Muhlenberg College

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Analysis, Standardization, and Diagramming

Section 1: introduction.

In this unit, we will focus on argument identification and analysis. Argument identification involves spotting arguments and distinguishing them from their surroundings. We briefly discussed argument identification in Chapter 1, and saw that we need to be on the lookout for particular words (e.g. ‘since’, ‘so’, ‘because’, and ‘hence’) that frequently indicate the presence of an argument. The other skill we will focus on in this unit is argument analysis. In general, to analyze an argument is to determine its intended structure.

As we’ve seen, the crucial elements or “bones” of any argument are its premises and its conclusion, and we determine an argument’s structure by identifying these elements and figuring out how they fit together. We are beginning with the skills of identification and analysis in particular because recognizing and accurately determining argumentative structure are prerequisites for accurate evaluation. After all, we can’t assess whether an argument is good or bad until we know what the argument is supposed to be! More precisely, we can’t say whether an argument is sound or not, unless we know what its conclusion is, and what premises have been offered on its behalf.

Before we get started, it is important to make two notes. First, you are already skilled at argument identification and analysis. Again, these are prerequisites for evaluation, and you have been evaluating arguments almost your whole life. However, these skills are largely intuitive. The goal here, then, is not to develop new skills, but instead to sharpen or enhance existing ones. To this end, we will slow down and think through the steps involved in identification and analysis. By sensitizing ourselves to argumentative language in this way, we will make what is mostly implicit in everyday practice, explicit. More specifically, this will involve giving names to a variety of argumentative moves and situations, identifying a method for seeing behind an author’s words, and learning some techniques for representing arguments. Proceeding in this way will allow us to see in detail how arguments are expressed and structured, and will ultimately put us in a better position to evaluate and engage with arguments.

The second note has to do with reading. We will be focusing on arguments in text, and one of the things that we will find is that in all but the simplest cases, argument analysis requires active engagement with the text. We actively engage with a text when we ask questions of it: what is the author trying to say? What reasons does the author give for the conclusion? Why do they believe the premises are true? We do not always read actively. When we read a magazine or a novel, we normally sit back and let the author provide us with information or tell us a story. However, when it comes to argument analysis passive reading will not do. In most cases, argument analysis will involve actively looking to the text for clues, and using these clues to piece together the author’s intended argument. Active engagement with a text can be demanding—especially at first, but it is an important skill, and something you will likely find becomes easier with practice.

Section 2: Analyzing Simple Arguments

Let’s start with a simple argument.

Since Banana Republic’s sale items will go fast, I think we should go there first.

The first thing we should notice in this case is the word ‘since’. This word typically indicates the presence of an argument, and a look back at the context confirms this. Now that we have an argument, how do we analyze it? We need to break the argument into its components, i.e. its premises and conclusion. Because the word ‘since’ is not only an argument indicator, but a premise indicator, we know that what follows it—‘ Banana Republic’s sale items will go fast’—is being used as a premise. This premise supports the proposition ‘we should go there first’ which is the conclusion. We have captured all there is to say about this argument’s structure, and so our analysis is complete.

Importantly, what makes this argument simple, as we will use the term, is not that it is short or easy to understand. Instead, this argument is simple because it draws only one conclusion. As we will see later in the chapter, simple arguments can be chained together to form complex arguments. For now, however, let us take a look at another simple argument.

The coach will likely be fired, given the allegations of unethical recruiting practices and the team’s sub-par performance the last three years.

The term ‘given’ and a quick look at the context tells us that we have an argument on our hands. ‘Given’ is a premise indicator, and in what immediately follows the author makes two claims. The author is claiming that there are allegations of unethical recruiting practices and that the team’s performance over the last three years has been sub-par. The author is offering these two premises as evidence for the proposition that the coach will likely be fired, and so this latter proposition is the conclusion.

This second example is similar to the first; however, we should note two important differences. First, in this example there are two premises, whereas in Ex. 1 there was only one. This does not change the fact that like Ex. 1, Ex. 2 is a simple argument. Again, what makes an argument simple is that it draws only one conclusion, and this means that simple arguments can have many premises. The second point has to do with order. In Ex. 1 the premise came first and the conclusion last, whereas in Ex. 2 the order is reversed. This teaches us an important lesson: premises are not always presented first, nor are conclusions always presented last . As it turns out, in everyday speech and writing, arguments are presented in many different ways. Sometimes, in fact, the conclusion is placed between premises (as we will see).

Section 3: Representing Argumentative Structure

The point of analyzing an argument is to uncover its structure, and it will be useful to have a uniform or standard way of representing the bones of an argument. For simple arguments we will use the following process of representation. For each distinct part of an argument (each of its premises and its conclusion), we will assign a unique number, assigning the highest number to the conclusion. We will then stack the propositions in numerical order, and add a conclusion indicator to the conclusion for clarity. We will call this way of representing an argument, a standardization .

In Ex.1, the argument consists in two propositions: the premise and conclusion, and so in our standardization we will stack the numbers 1) and 2). We will assign 2) to the conclusion, and then add the conclusion indicator ‘so’ to the argument. This gives us the following standardization of Ex. 1:

- Banana Republic’s sale items will go fast.

- So, we should go there first.

The argument in Ex. 2, consists of three propositions: two premises and the conclusion. As a consequence, our standardization will stack the numbers 1, 2, and 3, we will make 3 the conclusion, and add the indicator word ‘so’ to it. This gives us the following standardization for Ex. 2:

- There have been allegations of unethical recruiting practices.

- The team’s performance over the last three years has been sub-par.

- So , the coach will likely be fired.

Standardizing arguments is a useful way of representing an argument’s structure, but it is not the only way. A different way of representing the bones of an argument is called diagramming . Diagramming is a more abstract way of representing arguments that allows us to see an argument’s structure independently of its subject matter.

Just as we would in a standardization, we start a diagram by assigning each part of an argument a number. We start numbering at one and reserve the highest number for the conclusion. This is where the similarity ends, however. First, when diagramming, we let the assigned number stand in for the whole proposition; we do not rewrite the premises and conclusions as we do in standardizations. Second, when we diagram we will use numbers with circles around them to indicate propositions. Third, we will not stack the numbers, but work horizontally to capture the relation between the premise and conclusion. Doing so, requires the use of two additional symbols: the arrow (‘→’) represents the relationship between an argument’s premises and its conclusion. The arrow points away from the premises, and toward the conclusion the premises purport to establish. Further we will use the plus (‘+’). The + represents the idea that an author intends two or more distinct propositions to be taken together as evidence.

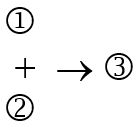

The diagram of Ex. 1 looks like this:

Thus, 1 represents the proposition ‘ Banana Republic’s sale items will go fast’, while 2 represents the conclusion that ‘we should go there first’. Moreover, the arrow points from 1 to 2 because 1 is the evidence that purports to establish 2.

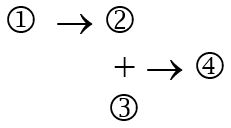

In the case of Ex. 2, the author offers two pieces of evidence on behalf of his conclusion. and this is reflected here by the conjunction of 1 and 2 (which represent the propositions that there are allegations of unethical recruiting practices and that the team’s performance over the last three years has been sub-par).

Diagram of Ex. 2:

It is important to note that standardization and diagramming are distinct ways of representing argumentative structure, and we can use one without the other. That is, we might standardize an argument without diagramming it, and vice versa (though if you choose to diagram an argument without also standardizing it, you’ll have to find a way connect your numbers to the propositions they represent). In this unit, however, we will always standardize and diagram examples, and we will use the numbers assigned in the standardization of an argument for the diagram. Now that we have discussed simple arguments, let’s see how analysis works in more complex cases.

Section 4: Analyzing Complex Arguments

A simple argument draws only one conclusion. However, simple arguments can be put together to create complex arguments. As we will see, complex arguments draw one or more sub-conclusions on the way to the main conclusion. Consider the following case:

You should fill your car’s tires with nitrogen instead of plain air for two reasons. First, nitrogen will diffuse through the tire walls much more slowly than plain air, since nitrogen molecules are bigger than molecules of oxygen. Second, filling your tires with nitrogen keeps water vapor from getting inside your tires.

Uncovering the structure of this argument means isolating all of the parts and determining their relationships. We will begin by using indicator words as our guide. On a first pass, we should be struck by the presence of two indicators: ‘two reasons’ and ‘since’. The author is claiming that there are two reasons for thinking that “You should fill your car’s tires with nitrogen instead of plain air.” The author has numbered these premises using the term ‘first’ and ‘second’. Thus, these two propositions are premises that support the conclusion that you should put nitrogen in your tires. However, there is one other indicator word here—‘since’. This suggests that there is a second justification present. Indeed, the fact that “nitrogen molecules are bigger than molecules of oxygen” is given as a reason to believe that “nitrogen will diffuse through the tire walls more slowly than plain air will.” This means the author’s claim that “nitrogen will diffuse…” is being used as both a premise and a conclusion. On the one hand, it is a premise because it supports the proposition that you should fill your tires with nitrogen. On the other, it is a conclusion because it is supported by the proposition that nitrogen molecules are bigger than oxygen molecules.

Our analysis is complete; we have uncovered all the parts of the argument and we know how they are related. In order to represent this argument’s structure let’s standardize it. As we learned above, we should assign a number to each relevant proposition reserving the highest number for the conclusion. Wait. There are two conclusions in this argument. Which one should we assign the highest number? We will reserve the highest number for the ultimate or main conclusion, which in this case is that “You should fill your car’s tires with nitrogen instead of plain air.” Can we simply assign numbers to the other propositions, and standardize the argument like this:

Standardization for Ex. 3?

- Nitrogen will diffuse through the tire walls much more slowly than plain air.

- Nitrogen molecules are bigger than molecules of oxygen.

- Filling your tires with nitrogen keeps water vapor from getting inside your tires.

- So, you should fill your car’s tires with nitrogen instead of plain air.

No. While this standardization captures all the relevant propositions, it misses an important part of the argument’s structure. Although 1-3 all ultimately support the conclusion, they do not do so in the same way. The proposition that nitrogen molecules are bigger than molecules of air only supports the conclusion because it gives evidence for the proposition that nitrogen will diffuse more slowly than plain air. In other words, 2 only supports 4 through its support of 1; let’s say that 2 offers only indirect support of 4 whereas 1 and 3)offer direct support , and our representation of the argument needs to reflect this. This means that we’ll need to supplement our basic standardization process.

First, let’s follow the convention that conclusions always come after their premises, so we’ll want to assign the proposition ‘nitrogen molecules are bigger than molecules of oxygen’ a higher number than the proposition ‘nitrogen will diffuse through the tire walls much more slowly than plain air’. Second, since the proposition ‘nitrogen will diffuse…’ is a conclusion, we should make it clear by adding an indicator word to our standardization. Last, when there are multiple inferences in an argument we need to know for sure what premises lead to what conclusion. To mark this, let us agree that after every conclusion we will note the premises from which the proposition is drawn. Following these additional rules gives us the following standardization:

Standardization for Ex. 3:

- So , nitrogen will diffuse through the tire walls much more slowly than plain air. (from 1)

- So , you should fill your car’s tires with nitrogen instead of plain air. ( from 2 and 3)

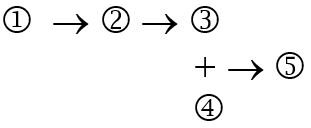

What does a diagram of Ex. 3 look like? We begin our diagrams with the conclusion. Following the number system we used in the correct standardization of Ex. 3, our main conclusion is 4, so we should start by drawing the number four with a circle around it. Evidence is offered on behalf of this conclusion, so we should draw an arrow to the left of our circled number pointing to it. What evidence is offered on behalf of 4? The propositions numbered 2) and 3) above are the direct evidence for 4), and we should connect these pieces of evidence using a plus since it is clear that the author intends these pieces of evidence to be taken together. Last, as we’ve seen, the author offers 1) as evidence for 2), so we should draw an arrow to the left of 2) pointing to it, and 1) to the left of that. This gives us the following diagram:

Diagram for Ex. 3:

The diagram of this argument shows very clearly that this complex argument is built out of two simple arguments. Working backwards from the main conclusion, there is the simple argument with 2 and 3 as premises and 4 as the conclusion. In addition, because the author gives a reason for 2, we have another simple argument from 1 to 2. Let us turn to some exercises.

Exercise Set 3A:

Directions: For each of the following determine whether the passage contains an argument. If it does not, write “no argument”. If it does, then standardize and diagram the argument.

It seems likely that this year will be Morita’s first as a professional without a major win on account of continuing problems with her short game.

Your health care provider will not cover this test on the grounds that it is neither medically necessary nor an expense covered by your policy.

Disney was the first studio to release a truly massive film originally set for theaters onto a streaming platform. To watch their latest version of Mulan, viewers needed to pay close to $30 on top of their Disney+ subscription.

Judging from the astonishing range of daily life and human endeavor reflected in his poems and plays, we can only infer that Shakespeare was a keen observer.

You are not eligible for an upgrade, since you haven’t signed up for our newsletter, and signing up is necessary for eligibility.

Advisory boards are limited in authority, and consequently in legal responsibility, to those powers granted by the local government.

Exercise Set 3B:

We can be sure that the murder was committed by the judge, given that it had to be either the butler or the judge, and we know it wasn’t the butler since he was passionately in love with the victim.

Since goat’s milk contains smaller fat globules than cow’s milk, it is easier to digest than cow’s milk. Consequently, goat’s milk may be a viable alternative for children who have a difficulty digesting cow’s milk.

To insert genes into a cell, scientists often prick it with a tiny glass pipette and inject a solution with the new DNA. The extra liquid and the pipette itself, however, can destroy it. In place of a pipette, scientists at BYU have developed a silicon lance. They apply a positive charge to the lance so that the negative charged DNA sticks. When the device enters a cell, the charge is reversed and the DNA is set free. In a recent study using this method, 72 percent of nearly 3,000 mouse eggs cells survived. [1]

The proposed ban on high-capacity magazines doesn’t make any sense. Think about it: a ban on high-capacity magazines wouldn’t necessarily prevent any of these mass killings, since with practice a person can learn to swap out a depleted 7 round magazine in a couple of seconds or less.

Because attention is a limited resource—we can attend to only 110 bits of information per second, or 173 billion bits in an average lifetime—our moment-by-moment choice of attentional targets determines, in a very real sense, the shape of our lives. [2]

The chief reason painting is superior to sculpture is that painting as a medium affords the artist many more possibilities than sculpture does. After all, how can you sculpt mist or clouds, or the appearance of reflective surfaces? Likewise, in painting the artist can represent impossible objects, and this is not an option for the sculptor who is bound by the laws of space and time.

Exercise Set 3C:

Make up a complex argument and write it out. Once you’ve done this, standardize and diagram your argument.

#2: Below is a standardized argument without any content. Draw the diagram that corresponds to this standardization.

3) So, xxxxxx (from 1 and 2)

4) So, xxxxxx (from 3)

5) So, xxxxxxx (from 4)

Below is an argument diagram. Create the standardization that corresponds to this diagram (don’t worry about content, just follow the xxxxx pattern from above).

What is a “rhetorical question”? Give an example. Can a rhetorical question be part of an argument?

- Adapted from Giller, G. (2014, July 1). Hold Still. Scientific American , 311 (1), 19. ↵

- Adapted from Anderson, S. (2009, May 25). In Defense of Distraction. New York . 43 (18), 28-33, 100-101. ↵

Critical thinking as argument analysis?

- Published: May 1989

- Volume 3 , pages 115–126, ( 1989 )

Cite this article

317 Accesses

11 Citations

Explore all metrics

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Critical thinking as argument analysis?. Argumentation 3 , 115–126 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00128143

Download citation

Issue Date : May 1989

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00128143

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Critical Thinking

- Argument Analysis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

Will A.I. Be a Creator or a Destroyer of Worlds?

By Thomas B. Edsall

Mr. Edsall contributes a weekly column from Washington, D.C., on politics, demographics and inequality.

The advent of A.I. — artificial intelligence — is spurring curiosity and fear. Will A.I. be a creator or a destroyer of worlds?

In “ Can We Have Pro-Worker A.I. ? Choosing a Path of Machines in Service of Minds,” three economists at M.I.T., Daron Acemoglu , David Autor and Simon Johnson , looked at this epochal innovation last year:

The private sector in the United States is currently pursuing a path for generative A.I. that emphasizes automation and the displacement of labor, along with intrusive workplace surveillance. As a result, disruptions could lead to a potential downward cascade in wage levels, as well as inefficient productivity gains. Before the advent of artificial intelligence, automation was largely limited to blue-collar and office jobs using digital technologies while more complex and better-paying jobs were left untouched because they require flexibility, judgment and common sense.

Now, Acemoglu, Autor and Johnson wrote, A.I. presents a direct threat to those high-skill jobs: “A major focus of A.I. research is to attain human parity in a vast range of cognitive tasks and, more generally, to achieve ‘artificial general intelligence’ that fully mimics and then surpasses capabilities of the human mind.”

The three economists make the case that