Mental Health

On This Page: -->

Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Frequently asked questions, mental health resources.

NIH has compiled a library of resources related to COVID-19 and mental illnesses and disorders, including condition-specific and population-specific resources.

An Urgent Issue

Both SARS-CoV-2 and the COVID-19 pandemic have significantly affected the mental health of adults and children. In a 2021 study, nearly half of Americans surveyed reported recent symptoms of an anxiety or depressive disorder, and 10% of respondents felt their mental health needs were not being met. Rates of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorder have increased since the beginning of the pandemic. And people who have mental illnesses or disorders and then get COVID-19 are more likely to die than those who don’t have mental illnesses or disorders.

Mental health is a focus of NIH research during the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers at NIH and supported by NIH are creating and studying tools and strategies to understand, diagnose, and prevent mental illnesses or disorders and improve mental health care for those in need.

How COVID-19 Can Impact Mental Health

If you get COVID-19, you may experience a number of symptoms related to brain and mental health, including:

Cognitive and attention deficits (brain fog)

Anxiety and depression

Suicidal behavior

Data suggest that people are more likely to develop mental illnesses or disorders in the months following infection, including symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). People with Long COVID may experience many symptoms related to brain function and mental health.

How the Pandemic Affects Developing Brains

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children is not yet fully understood. NIH-supported research is investigating factors that may influence the cognitive, social, and emotional development of children during the pandemic, including:

Changes to routine

Virtual schooling

Mask wearing

Caregiver absence or loss

Financial instability

Not Everyone Is Affected Equally

While the COVID-19 pandemic can affect the mental health of anyone, some people are more likely to be affected than others. People who are more likely to experience symptoms of mental illnesses or disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic include:

People from racial and ethnic minority groups

Mothers and pregnant people

People with financial or housing insecurity

People with disabilities

People with preexisting mental illnesses or substance use problems

Health care workers

People who belong to more than one of these groups may be at an even greater risk for mental illness.

Telehealth’s Potential to Help

The pandemic has prevented many people from visiting health care professionals in person, and as a result, telehealth has been more widely adopted during this time. Telehealth visits for mental health and substance use disorders increased significantly from 2020 to 2021 and now make up nearly half of all total visits for behavioral health.

Widespread adoption of telehealth services may help people who otherwise would not be able to access mental health support, such as people in rural areas or places with few providers.

I have a preexisting mental illness. Is COVID-19 more dangerous to me?

COVID-19 can be worse for people with mental illnesses. Data suggest that people who reported symptoms of anxiety or depression had a greater chance of being hospitalized after a COVID-19 diagnosis than people without those symptoms.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that having mood disorders and schizophrenia spectrum disorders can increase a person’s chances of having severe COVID-19. People with mental illnesses who belong to minority groups are also more likely to get COVID-19. And people with schizophrenia are significantly more likely to get COVID-19 and more likely to die from it.

Despite these risks, effective treatments are available. If you have a preexisting mental illness and get COVID-19, talk to your health care professional to determine the treatment plan that’s appropriate for you.

I’m experiencing symptoms of a mental illness or disorder. What should I do?

If you are experiencing symptoms of anxiety, depression, or any other mental illness or disorder, there are ways you can get help. For immediate help:

Call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 (para ayuda en español, llame al 988)

Call or text the Disaster Distress Helpline , 1-800-985-5990 (press 2 for Spanish)

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration can help you find mental health or substance use specialists.

Talk to your health care professional or mental health care professional. Together, you can work on a plan to manage or reduce your symptoms.

What research is NIH doing on the mental health impacts of COVID-19?

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and other NIH Institutes have created research initiatives to address mental health for people in general and for the most vulnerable people specifically. Examples of this research include:

NIH's Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER) Initiative has launched RECOVER-NEURO , a clinical trial that will test interventions to combat cognitive problems caused by Long COVID, including brain fog, memory problems, difficulty with attention, thinking clearly, and problem solving.

NIMH launched a five-year research study called RECOUP-NY to promote the mental health of New Yorkers from communities hard-hit by COVID-19. The study will test the use of a new care model called Problem Management Plus (PM+) that can be used by non-specialists.

A study funded by NIMH is examining the use of mobile apps to address mental health disparities .

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) is funding research to understand the effects of mask usage for children , including any impacts on their emotional and brain development.

NIMH is funding research on the impacts of the pandemic on underserved and vulnerable populations and on the cognitive, social, and emotional development of children .

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) is funding research on how COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 affect the causes and consequences of alcohol misuse .

A collaborative study supported by NIMH and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) enrolled more than 3,600 people from all 50 U.S. states to understand the stressors affecting people during the pandemic.

Mental Health Resources by Topic

A library of resources related to COVID-19 and mental illnesses and disorders

Page last updated: September 28, 2023

- High Contrast

- Increase Font

- Decrease Font

- Default Font

- Turn Off Animations

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- HIV and AIDS

- Hypertension

- Mental disorders

- Top 10 causes of death

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- Data collection tools

- Global Health Observatory

- Insights and visualizations

- COVID excess deaths

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment case

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Publications detail /

Mental Health and COVID-19: Early evidence of the pandemic’s impact: Scientific brief, 2 March 2022

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a severe impact on the mental health and wellbeing of people around the world while also raising concerns of increased suicidal behaviour. In addition access to mental health services has been severely impeded. However, no comprehensive summary of the current data on these impacts has until now been made widely available.

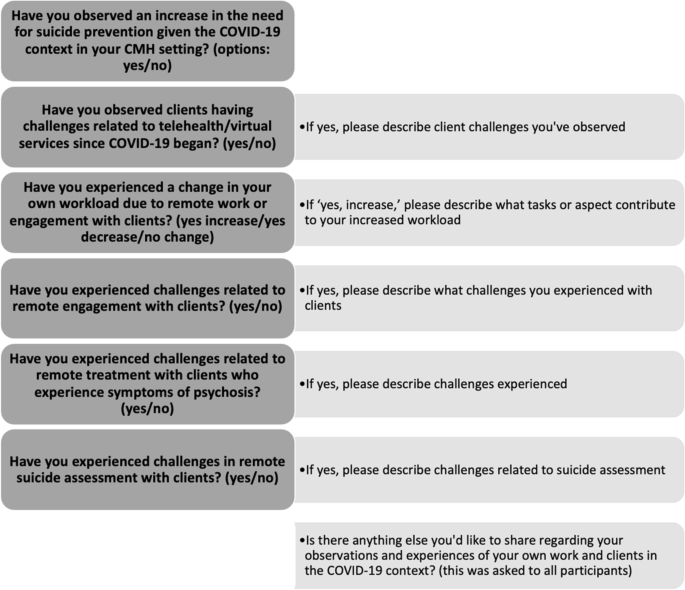

This scientific brief is based on evidence from research commissioned by WHO, including an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses and an update to a living systematic review. Informed by these reviews, the scientific brief provides a comprehensive overview of current evidence about:

- the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence of mental health symptoms and mental disorders

- the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on prevalence of suicidal thoughts and behaviours

- the risk of infection, severe illness and death from COVID-19 for people living with mental disorders

- the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health services

- the effectiveness of psychological interventions adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic to prevent or reduce mental health problems and/or maintain access to mental health services

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 07 March 2024

The impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on mental health patient populations in the United States

- Ibtihal Ferwana 1 &

- Lav R. Varshney ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2798-5308 1

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 5689 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

2436 Accesses

19 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health care economics

- Health policy

During the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, lockdowns and movement restrictions were thought to negatively impact population mental health, since depression and anxiety symptoms were frequently reported. This study investigates the effect of COVID-19 mitigation measures on mental health across the United States, at county and state levels using difference-in-differences analysis. It examines the effect on mental health facility usage and the prevalence of mental illnesses, drawing on large-scale medical claims data for mental health patients joined with publicly available state- and county-specific COVID-19 cases and lockdown information. For consistency, the main focus is on two types of social distancing policies, stay-at-home and school closure orders. Results show that lockdown has significantly and causally increased the usage of mental health facilities in regions with lockdowns in comparison to regions without such lockdowns. Particularly, resource usage increased by 18% in regions with a lockdown compared to 1% decline in regions without a lockdown. Also, female populations have been exposed to a larger lockdown effect on their mental health. Diagnosis of panic disorders and reaction to severe stress significantly increased by the lockdown. Mental health was more sensitive to lockdowns than to the presence of the pandemic itself. The effects of the lockdown increased over an extended time to the end of December 2020.

Similar content being viewed by others

The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic

The real-time infection hospitalisation and fatality risk across the COVID-19 pandemic in England

Risk of COVID-19 death in adults who received booster COVID-19 vaccinations in England

Introduction.

As the COVID-19 pandemic began, confirmed cases rose, and mandated policy responses were enacted, mental health concerns started to be alarming 1 , 2 , 3 . The deterioration of mental health was observed during the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic, March–June 2020 4 , 5 , especially among women and college students 6 , 7 , 8 . Further, people with preexisting psychiatric disorders 9 , 10 and people that encountered COVID-19 itself 4 developed more mental health issues during the pandemic.

In the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, people voluntarily stayed at home and limited their trips for weeks before public policy interventions were imposed 11 . Subsequently, social distancing policies were issued globally as a form of non-pharmaceutical intervention, including limiting people’s gatherings, closing schools, and fully restricting movements by lockdown orders (also called stay-at-home or shelter-in-place orders) 12 , so as to contain virus spread in light of the increasing number of COVID-19 cases and fatalities.

Given that various intertwined events took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, the cause of mental health deterioration is not clear. One possible explanation is the increased severity of COVID-19 which led to increased anxiety, worry, and depression 13 . Another explanation is that policy responses to the pandemic, particularly the lockdown orders, contributed to worsening mental health.

Previous studies observing the decline in mental health have faced a challenge in determining possible causes or selecting direct measures. For example, Refs. 14 , 15 found that depression and anxiety symptoms almost quadrupled from 2019 to June 2020, but could not infer causality given the study design. Other studies found that reduced physical activity resulting from restricted mobility led to higher rates of depression during the pandemic, but could not establish causality since they lacked pre-COVID-19 data 10 , 16 , 17 . Two other important studies by Refs. 18 , 19 used Google search data and found that the timing of lockdown policies has been significantly associated with searches of terms related to worry , sadness , and boredom revealing negative feelings. A recent study established causality of the effect of lockdown restrictions on worsening mental health using a clinical mental health questionnaire in Europe 20 . Although these studies considered pre-COVID-19 trends and have established causality on the lockdown orders, they lacked measures that reflect the rising need for mental health treatment and lacked a large representative population.

Examining the use of mental health resources and the prevalence of mental illnesses would further help in measuring the actual cost of COVID-19 lockdowns on mental health and inform mental health treatment resource planning for future lockdowns. Mental disorders have been more economically costly than any other disease, in which mental disorders were the leading segment of healthcare spending in the United States 21 , with the potential cause of a global economic burden 22 . Mental health has been related to social capital on individual and community levels 23 , 24 . Indeed, good social capital plays a role in promoting healthier public behaviors, especially during COVID-19 25 . The risk of mental health degradation goes beyond to impact the advantage of social capital in the face of viral diseases. Given these consequences of poor mental health on health care systems 26 , it has been essential to mitigate additional mental degradation and avoid potential future economic and social costs.

In this work, we consider measures that reflect the actual seeking of mental health services covering a large fraction of the United States population. To the best of our knowledge, there is no large-scale study that has investigated the effect of lockdown on the usage of mental health resources across the country. We empirically estimate the causal effect of COVID-19 social distancing policies on mental health across counties and states in the United States by comparing the differences in changes between locked and non-locked down regions using a large-scale medical claims dataset that covers most hospitals in the country. Specifically, we are interested to know whether the increase in mental health patients can be explained by COVID-19 lockdowns. Causal inference gives us the tools to uncover causal relationships rather than correlational relationships 27 , in order to understand the impact of COVID-19 policies on mental health.

We use the daily number of patients who visit mental health facilities as a measure for the usage of mental health resources, and we consider emergency department (ED) visits for mental health issues as a proxy for the development of new mental diseases, here, so severe that treatment could not be avoided. We consider ED visits to reflect the utilization of hospital resources under the shortage of medical staff. During COVID-19 there were patients with acute conditions reaching ED in which they have not been in regular outpatient visits 28 . Also, given the shortage in in-patient beds during the pandemic, mental health patients were admitted to ED instead 29 . Therefore, ED visits were of interest to indicate unmet mental health needs. The usage of mental health resources can further trigger analysis of economic costs borne by health care systems and the country as a whole. Mental health ED treatment visits might further reflect the mental health cost on an individual level.

Our results show that extended lockdown measures significantly increase the usage of mental health resources and ED visits. In particular, mental health resource usage in regions with lockdown orders has significantly increased compared to regions without a lockdown. The effect size of lockdowns was not only positive and significant but was also increasing till the end of December 2020. Our results further imply that mental health is more sensitive to policy interventions rather than the evolution of the pandemic itself.

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Institutional Review Board declared this work to be exempt from review. The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Institutional Review Board waived the need for informed consent for the current study. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

We used three sets of data to conduct our study: mental health claims data including emergency department (ED) claims, COVID-19 cases data, and lockdown dates data.

The mental health data is a large de-identified medical claims corpus provided by Change Healthcare for years 2019 and 2020. Change Healthcare serves 1 million providers covering 5500 hospitals with 220 million patients (which is roughly two-thirds of the US population) and represents over 50% of private insurance claims across the United States. It covers 51 states/territories and a total of 3141 counties (and equivalent jurisdictions like parishes). The data set includes millions of claims per month from the private insurance marketplace, and some Medicare Advantage programs and Medicaid programs using private insurance carriers, excluding Medicare and Medicaid indemnity claims, which is a limitation in the dataset coverage.

Given that different age and gender groups were affected differently during the pandemic 6 , 7 , 8 , we consider a variety of population subgroups in our analysis. Specifically, we consider subgroups of different age, gender, and mental health conditions. Not only do we look at the total mental health claims, but we also select specific mental health conditions, such as anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder. Our selected mental health conditions have been also been examined by others 30 during the COVID-19 pandemic. More details on the used clinical codes of mental health records are found in Supplementary Appendix Table 1 . We show summary statistics of the data and its subset representing gender, age, and mental disorders in Table 1 .

For COVID-19 cases, we considered state-level and county-level cases reported in the United States taken from the New York Times database 31 from the first case date in late January 2020 to December 31, 2020, covering 3218 counties in 51 states/territories. Given that reported cases depend on the testing results, thus, the data is limited by the fact that there was a widespread shortage of available tests in different regions at different times. The undercounts of COVID-19 cases used in this study would only weaken the effect we present, and so fixing the data would only strengthen the resultant effect.

For lockdown data, we used the data from the COVIDVis project URL: https://covidvis.berkeley.edu/ led by the University of California Berkeley to track policy interventions on state and county levels, in which they depended on government pandemic responses to construct the dataset. We considered the dates of two order types, shelter-in-place and K-12 school closure at state and county levels. The earliest and latest shelter-in-place orders were on March 14 and April 7, 2020, covering 2598 counties in 43 states. The earliest K-12 school closure was on March 10 and the latest was on April 28, 2020, covering 2465 counties in 39 states. The data is comprehensive, in which states and counties that do not appear in the dataset are considered without officially imposed lockdown. We focus on the impact of the initial shutdowns to avoid complications related to re-opening and repeated closures. Given that in some regions people tend to voluntarily isolate themselves at home and limit their trips before official lockdown orders 11 , therefore, lockdown dates might be limited to reflect the actual social distancing behavior across regions during the pandemic. However, lockdown dates would better reflect the beginning of persistent social distancing behaviors for a larger population group, which is useful to our study, unlike voluntary behaviors.

Difference-in-differences analysis

To estimate the effects of COVID-19 mitigation policies on mental health patients at county and state levels, we conducted a difference-in-differences (DID) analysis, which allows for inferring causality based on parallel trends assumption. For DID analysis we considered daily mental health patients’ visits from the date of September 1, 2019, till December 31, 2020, to observe the prolonged effects since mental health disorders may appear sometime after a trauma 32 . We aim to have balanced periods for pre- and post-lockdown interventions, and this is achievable with this selected range of dates. We used two outcomes, weighted and raw numbers of daily patient visits, weighted outcomes are normalized by the region population.

Our approach leveraged the variation of policy-mandated dates in different counties or states with 8 states that did not declare an official lockdown. Accordingly, we constructed both treated and control groups to implement the analysis. We estimated the following regression as our main equation:

where \(Y_{cd}\) is the outcome in a given region c (county or state) on a date d , \(policy_{jcd}\) indicates whether a policy j has been mandated for a region c on a date d , \(\beta _j\) is the DID interaction coefficient, representing the effect of introducing policy j , and \(\delta _c\) and \(\delta _{d}\) are fixed effects for region and date respectively. The region fixed-effect is included to adjust for time-invariant (independent of time) unobserved regional characteristics that might affect the outcome. For example, each county/state has its local health care system, social capital index, age profile, and socioeconomic status that the fixed effect controls for. Further, the date fixed effect \(\delta _{d}\) is included to adjust for factors that vary over time, such as COVID-19 rates or social behavioral change.

Control by the evolution of COVID-19 cases

Even though DID avoids the bias encountered in time-invariant factors, the bias of time-varying confounders may still be present 33 . Therefore, we consider the COVID-19 confirmed cases \(x_{cd}\) as a main confounder factor in counties or states and we control for it. We follow 34 to use a time-varying adjusted (TVA) model, based on the assumption that the confounding variable affects both treated and untreated groups regardless of policy intervention. We measured the interaction of time and the confounding \(x_{cd}\) covariate at county- and state-levels

Therefore, to mitigate the effect of potential confounders, e.g. socio-economic status and COVID-19 growth, we use several techniques from econometrics 35 . Specifically, we use the fixed effects \(\delta _c\) and \(\delta _d\) in ( 1 ) to adjust for time-invariant confounders related to location and time. Additionally, we use TVA 34 to adjust for time-varying confounders such as COVID-19 growth.

Event-study model

DID models rely on the assumption of parallel pre-treatment trends to exist in both treated and untreated groups. Hence, in the absence of a policy, treated counties or states would evolve similarly as untreated counties or states. To assess equal pre-policy trends, we designed an event-study type model 36 . We calculated k periods before policy implementation and used an event-study coefficient to indicate whether an outcome in specific date d and county/state c is within k periods before the policy implementation 18 , 37 . We estimated the following regression model:

where \(policy_{hsd}^k\) , a dummy variable, equals 1 if policy h took place k periods before the mandate, and zero otherwise. Period k is calculated in months, \(k=\{- 6, - 5, - 4, - 2, - 1, 0\}\) months, and the month of the policy implementation ( \(k=0\) ) is considered as the omitted category. Here, \(\beta _h^k\) is the event-study coefficient and we included all control variables as defined in ( 1 ).

Descriptive analysis

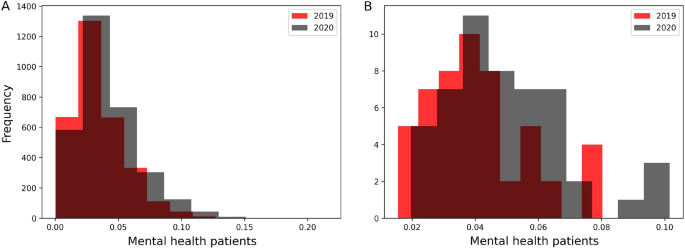

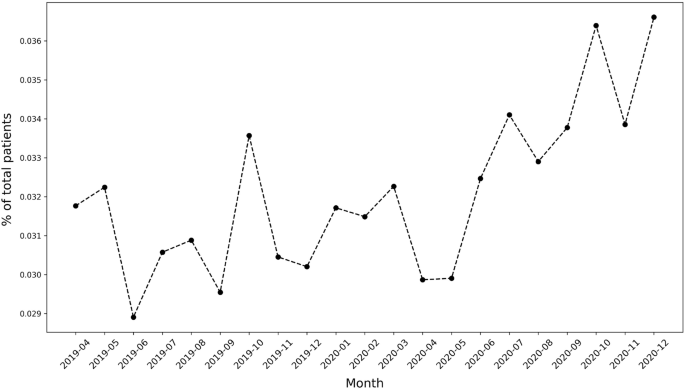

Before we delve into the causal DID inference, we report some statistics to describe the data of mental health patients. Among 16.7 million mental health patients in the United States, the mean age was 38.7 years and 56% were female. As seen in Fig. 1 , the distribution of mental health patients in states and counties shifted between 2019 and 2020. The total increase is 22% of all mental health patients of any mental health disorder as seen in Table 2 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Distributions of mental health patients weighted by regions’ populations in years of 2019 and 2020 in counties ( A ) and states ( B ). The total population increase is 22% in 2020.

Figure 2 shows the increasing trend of the number of mental health daily patients’ visits, though it decreased between March and April 2020, during lockdown mandates.

An obvious increase was during June 2020, which can be attributed to telemedicine options or relaxed lockdown measures.

Mental health patients over time.

Parallel trend assumption

To apply DID, first, we validate the pre-policy parallel trends assumption. We tested the equality of pre-policy trends for counties and states using ( 3 ). We plot the event-study coefficients for 6 months before policy implementation from the models of stay-at-home and school-closure orders and the corresponding 95 % confidence intervals. Figure 1 (in Supplementary Appendix) shows that the event-study coefficients are generally non-significant, therefore we cannot reject the null hypothesis of parallel trends. Accordingly, the key assumption of parallel trends of DID is satisfied for both counties and states.

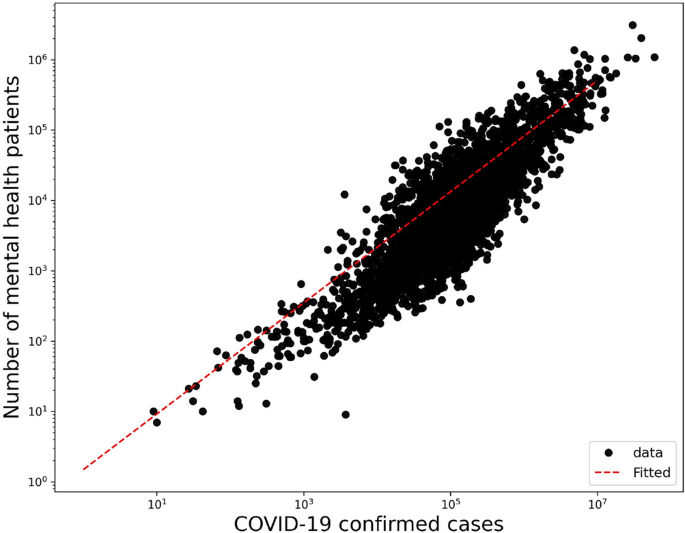

Correlation to COVID-19

Given the possibility that COVID-19 increasing cases act as a confounding factor to the increasing mental health burden, we adjusted our main DID regression to COVID-19 cases using the TVA model in ( 2 ). First, we validate that a correlation exists between mental health visits number and COVID-19 increasing cases. Figure 3 shows that a significant correlation between COVID-19 and mental health patients populations (R \(^2\) = 0.77, p-value < 2 \(\times 10^{-16}\) ) with an increase of 0.043 mental health visits for each new COVID-19 confirmed case. Adjusting for the COVID-19 cases acts as a proxy for adjusting for the pandemic effect itself.

Correlation of mental health daily visits and COVID-19 confirmed cases in a log-log plot with an increase of 0.043 mental health visits for each confirmed COVID-19 case in counties (R \(^2\) = 0.77, p-value < \(2 \times 10^{-16}\) ).

Effects on the usage of mental health resources

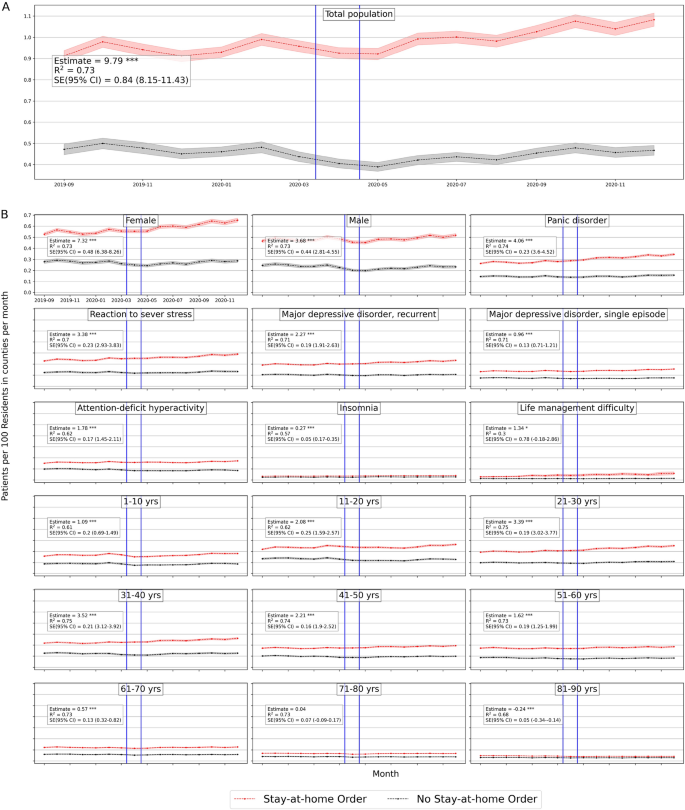

We consider daily visits of mental health patients for the causal DID inference model from September 1, 2019, to December 31, 2020. Figure 4 shows the monthly average mental health visits in counties with stay-at-home orders and without. In general, there is an increase in monthly visits in months after COVID-19 lockdowns in regions with enacted lockdowns. There is also a clear similar trend of visits between regions with and without lockdowns. This pre-COVID-19 trend has been validated in the previously mentioned event study. Figure 2 (in Supplementary Appendix) shows the monthly average visits in counties with and without school closure orders. Similarly, Figs. 3 and 4 (in Supplementary Appendix) show the average monthly visits at the state level.

We further investigate the causality relationship between daily visits and lockdown measures. In Tables 2 and 3 we summarize the estimated effects of COVID-19 lockdown measures on the weighted outcomes for counties and states respectively for different population groups with the adjusted results after controlling for COVID-19 cases. Tables 5 and 6 (in Supplementary Appendix) summarize the raw outcomes. Along with regression estimates, we include significance measures of p-value, 95% confidence intervals of standard errors, and R-squared ( \(R^2\) ). We will further discuss results for each population group in both counties and states in the following sections.

Tables 11 and 12 (in Supplementary Appendix) summarize the estimated effects of Eq. ( 1 ) at different periods of time k where k = {1, 5, 9}-months after lockdowns, to show the dynamic effect of stay-at-home and school closures in counties and states respectively.

Average number of mental health patients over time (September 2019–December 2020) in counties with stay-at-home orders and without. Vertical lines show the first stay-at-home order on 3/14/2020 and last on 4/07/2020 across United States. Difference-in-differences estimates are included for each population. (Detailed average percentage changes are listed in Table 3 ). \(***p < 0.01\) , \(**p < 0.05\) , \(*p < 0.1\) .

Effects on total population

We consider the overall mental health population including all mental health disorders with clinical codes defined in Supplementary Table 1 . Based on Table 2 there is a significant positive effect of stay-at-home order across counties on the weighted population of mental health patients’ daily visits, with a mean difference of 1 in 10,000 daily patient visits between counties with stay-at-home orders and counties without. On average, mental health patients increased by 18.7% but declined by 1% in counties without lockdown (Fig. 4 ). Adjusting for COVID-19 confounding effect preserves the positive effect significant on the mental health population with a similar effect size. School closure has also a significant, but a lower effect on the mental health patient population (estimated mean difference = 8.8 in 100,000 population), with a percentage increase of 17% and 16% in counties with closed schools and without respectively (Table 3 in Supplementary Appendix), with significant similar size effect while adjusted for COVID-19 cases.

Similar results are found at the state level, Table 3 shows that the effect of stay-at-home order is positively significant for total mental health patients (difference estimate is 8.8 and 8.6 when adjusted in 10 \(^5\) population) with 22% increase by December 2020 as compared to less than 2% increase in states without lockdown (Table 4 in Supplementary Appendix). However, school closures have no significant effect at the state level.

We further investigate whether the effect on mental health differs if we shorten the period of observation after lockdown interventions. We applied our main regression model ( 1 ) on outcomes after a 1-month of lockdown (maximum mid-May) and 5-month of lockdown (maximum mid-August) for each region. The sizes of the lockdown effects are positive and significant at different times. Also, they keep increasing from the first month after the lockdown date until the end of the year 2020, for both stay-at-home orders and school closures in counties (Table 11 in Supplementary Appendix) and states (Table 12 in Supplementary Appendix).

We further examined the sensitivity of our DID results by sequentially adding controls to the baseline DID model. Table 7 in the Supplementary Appendix shows results are robust and neither COVID-19 growth nor the social capital index contributed to the effect of lockdowns on mental health populations.

Gender effects

In counties, the estimated effects of stay-at-home orders on both women and men are 6.8 (6.6 when adjusted) and 5.7 (5.7 when adjusted) respectively (Table 2 ). Female patients’ daily visits increased by 24% in counties with stay-at-home orders in comparison with 3% in counties without (Table 3 in Supplementary Appendix). Male patients declined by 5% in counties without stay-at-home orders. Whereas the estimated effects of school closures are negative for females (mean difference = − 1.67, and − 3.89 when adjusted) and significant when adjusted. While for men, school closure effects were significantly positive (mean difference = 4.5 and 3.4 when adjusted) (Table 2 ). This implies that women have been affected more by stay-at-home orders than by school closures across counties.

Similarly in states, the estimated mean difference for women is 5.1 (5.6 when adjusted) and for men is 3.8 (4.1 when adjusted) in 10 \(^5\) population (Table 3 ). Female patients’ daily visits increased by 29% and 6% in states with stay-at-home orders and without respectively, while male patients’ daily visits decreased in states without stay-at-home lockdown (Table 4 in Supplementary Appendix). School closure did not show significant effects on women or men at the state level.

Even at an early stage of the COVID-19 lockdown, mental health visits for female and male patients were larger than in non-locked regions, which they were increasing significantly throughout the year 2020 in counties and states (Tables 11 , 12 in Supplementary Appendix)

Diagnosis effects

We selected the top five mental disorders (e.g. panic disorder ) that peaked in 2020, and other disorders of interest ( insomnia and life management difficulty ) to investigate the effect of lockdowns on patient populations for specific diagnosis. We provide the definition of each considered mental condition in Table 1 in Supplementary Appendix.

In counties, all disorders were positively and significantly affected by stay-at-home orders and by school closures with lower effect sizes. Patients diagnosed with panic disorder (ICD-10: F41) had the largest difference among other mental illnesses and increased in both county groups (31.8% vs 8.88%) with an estimated effect of 3.3 (3.2 when adjusted in 10 \(^5\) population). Patients with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ICD-10: F90) decreased in counties without stay-at-home orders by − 13.6% with an estimated effect of 3.2 (3.1 when adjusted) in 10 \(^5\) population.

Unlikely, patients with insomnia , with a significant estimated effect of \(-\,0.053\) in 10 \(^5\) population when adjusted, increased more in counties without school closures by 24% compared to 17% in counties with closures, which implies that insomnia was more in counties without school closures. Patients diagnosed with life management difficulty disorder increased more in counties without school closures as well by 127.85% compared with 94.64% with closures, and the estimated effect is − 0.6 (in 10 \(^5\) population) when adjusted (Tables 2 , 3 in Supplementary Appendix).

Similarly, at the state level, panic disorder (ICD-10: F41) increased by 38.4% in states with stay-at-home orders (Table 4 in Supplementary Appendix) and had the largest difference effect size with a mean difference of 2 in 10 \(^{5}\) population, similarly when adjusted (Table 3 ). Daily visits of patients with life management difficulty increased more in states without a school closure by 161.49% compared to 123.36% in states with closures with a significant estimated effect of \(-\,0.2\) (in 10 \(^{5}\) population) similarly when adjusted.

Over time, the effect of stay-at-home order kept increasing significantly for all selected mental disorders across counties (Table 11 in Supplementary Appendix) and states (Table 12 in Supplementary Appendix). While school closure effect is significantly increasing for most diagnoses except for life management difficulty diagnosis where the effect kept declining.

Age effects

At the county level, all age groups, both lockdowns have positive significant effects on the mental health patients’ daily visits. Based on Table 2 , the two largest significant differences were for adults between 31 and 40 years old and adults between 21 and 30 years old. Adults in their thirties increased by 20.47% in counties with stay-at-home orders but declined by − 0.1% in counties without, with a mean difference of 3.2 (in 10 \(^5\) population, similarly when adjusted). Adults in their twenties increased more in counties with stay-at-home orders by 30.01% compared to 11% in counties without, with an estimated effect of 1.5 (in 10 \(^5\) population, similarly when adjusted). Daily visits of young patients under 11 and adolescent patients under 21 are lower in counties without stay-at-home orders with significant positive effects of stay-at-home lockdown (Table 2 ).

Similarly, school closures affected patients in their thirties but with lower mean differences of 1.9 in 10 \(^5\) population (not significant when adjusted) (Table 3 ). They increased by 18.75 vs. 18.62 in regions with and without closures respectively. While daily visits of teenagers and adolescent (11 to 20) patients increased more in counties with school closures by 27.16%, compared to 19.17% in counties without closures, with estimated effect 2.2 in 10 \(^5\) population (not significant when adjusted) (Fig. 2 in Supplementary Appendix).

Similar observations are found at the state-level based on Table 3 . For most age groups both stay-at-home and school closure orders show significant positive effects, with the largest effect size for people in their thirties. Mental health patients who are in their thirties increased by 28% and 1% in states with stay-at-home orders and without respectively. Similarly, patients in their twenties increased by 40% and 15% in states with stay-at-home order and without respectively (Table 4 in Supplementary Appendix).

The effect sizes of both lockdowns on most age groups kept increasing significantly throughout the year of 2020. Children less than 11 years old had the largest change of estimation size, which indicates a greater effect on children appeared later on in counties with stay-at-home orders (Table 11 in Supplementary Appendix).

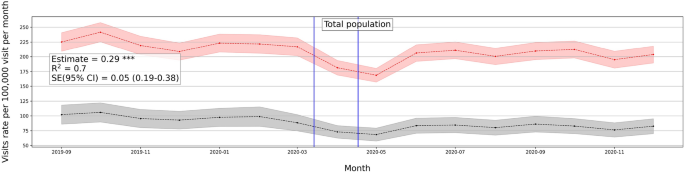

Effects on urgent treatment-seeking

We consider daily emergency department (ED) visits to reflect the emergent need to seek a mental health facility during the COVID-19 pandemic such that the condition is so severe to avoid treatment. The ED visits are defined according to the codes in Table 1 in Supplementary Appendix.

Average number of mental health ED visits over time (September 2019–December 2020) in counties with stay-at-home orders and without. Vertical lines show the first stay-at-home order on 3/14/2020 and last on 4/07/2020 across United States. Difference-in-differences estimates are included for each population. \(***p < 0.01\) , \(**p < 0.05\) , \(*p < 0.1\) .

ED visits decreased at the beginning of the pandemic, with a further finding that only patients with serious medical conditions were seeking care in ED 38 . One reason is that some patients were more willing to self-treat a variety of medical conditions than risk being exposed to COVID-19 in emergency rooms 39 . Given the role played by the ED during the first few months of the pandemic, it is linked with acute conditions for which patients could not avoid treatment

ED visits show a similar increasing positive trend in response to the lockdown measures (see Fig. 5 ). We also investigated ED visits outcomes on different population groups and the trend is consistent (Fig. 5 in Supplementary Appendix).

The effect of stay-at-home order on the overall ED visits is positive and significant with a magnitude of 0.29 weighted by population on state-level, and 0.32 when adjusted to the pandemic factor. Similarly, the effect of school closure is positive and significant with a value of 0.12 weighted by state population, same when adjusted (see Table 9 in Supplementary Appendix). Women and men groups show similar effect sizes with regard to ED visits, with an effect size of 0.2 for both groups even with adjusting for the pandemic factor. Similarly for psychiatric diagnosis, the effects are positive and significant with the largest effect size on panic disorder patients with a magnitude of 0.1 and 0.09 when adjusted. Age groups also show a similar trend of increasing daily ED visits with the largest effect size on the 21–30 age group of 0.07 and 0.05 when adjusted. Younger group ages did not show a significant effect on daily ED visits (Table 9 in Supplementary Appendix). Similar results appear for the school closures and county-level outcomes (Table 8 in Supplementary Appendix).

Robustness check

Given the differences in regions with respect to the number of hospitals, facilities, and patients, we conducted robustness checks of our main analysis to show that dropping multiple states does not change the estimates and that our results are not driven by specific regions. We dropped New York and Ohio states which were two states with the largest patient volume relative to population, and we apply our DID regression model to the weighted outcomes in states. The estimates remained robust, significant, and positive (Table 4 ). We also added all 2019 samples to expand the control group and the pre-intervention period. The relationship inferred from our analysis stayed significant and positive with this expansion.

We also conducted a similar check for ED analysis and found a similar observation of consistent robustness (Table 10 in Supplementary Appendix).

Early in March 2020, non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as social distancing policies, were imposed around the world to contain the spread of COVID-19 and proved to reduce the number of COVID-19 cases and fatalities 3 , 40 , 41 . Mitigation policies come with both costs and benefits, which may be further analyzed to help determine the optimal time to release or stop a policy intervention 42 . Prior research showed significant mental health degradation associated with the COVID-19 pandemic 6 , 7 , 18 , 19 , however, no research investigated the causal relation between COVID-19 mitigation policies and the usage of mental health resources. Yet the effects on the usage of mental health resources can further reflect the economic and health costs brought by the pandemic interventions. In our study, using large-scale medical claims data, we estimated the effects of lockdowns on the usage of mental health facilities and the prevalence of mental health issues at the state- and county levels in the United States.

Our findings demonstrate a statistically significant causal effect of lockdown measures (stay-at-home and school closure orders) on the usage of mental health facilities represented by an increasing number of issued medical claims for mental health appointments during COVID-19 pandemic. Also, ED visits were statistically significant and positive in locked-down regions which reflects the increase in emergent mental help-seeking due to the COVID-19 lockdowns. Results further emphasize the cost brought by extra months of lockdowns, in which effect sizes keep increasing through the end of 2020 in both mental health visits and ED visits. Some sub-population groups were exposed to a larger deterioration effect than other groups, such as women and adolescent groups.

Some mental health conditions were of particular interest to investigate during the COVID-19 lockdown. For example, sleep disturbance have been widely observed 43 specifically being a large concern in Italy 44 and China 45 during COVID-19 lockdown. Our results showed a similar observation, in which insomnia visits increased in counties with lockdowns. Similarly, burnout has been observed among health providers 46 and some working parents 47 during lockdown measures. Life-management difficulty disorder reflects burn-out and mental health issues in the workplace. Although this is not classified as a medical condition, but rather as an occupational phenomenon 48 , it is certainly a public health challenge 49 . Our results show that life management difficulty disorder, including burnout, increased with lockdowns at the state-level.

There have been several observations on the relation of school closures with increased mental health risks. Specifically, it was observed that some children were more likely to suffer from attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic 50 . This further confirms our findings of increased ADHD visits with school closures.

Our findings were observed at two granularity levels, county and state levels, with very similar trends of observations of increasing daily patient visits to mental health facilities. This further strengthens the established relationship of the effect of lockdowns on the mental health population with controlled possible sources of confoundedness. We also note our results stay the same when controlling for the evolution of the pandemic. This adds to the validity and robustness of the effects of lockdown measures on mental health despite the presence of the pandemic. It also implies that mental health is more sensitive to policy measures rather than to the evolution of the pandemic.

Given the various intertwined events and causes during the COVID-19 pandemic, our analysis is limited by several factors. First, it is important to point out that the adoption of lockdowns across states did not happen at random. Differences in shutdown orders’ timings and adoption across regions were associated with the differences in COVID-19 confirmed cases and fatality rates across those regions 51 , 52 and the differences in their health systems capacity 53 . Also, there exist other political, economical, and institutional factors that affect the adoption of COVID-19 measures and their strictness level across countries 54 . Even though the lockdown timing may be affected by regional factors related to the virus, such as the number of cases or institutional factors, however, there is no reason to believe that lockdown timing was affected by the prevalence of mental health in regions. Given that, we have also encountered regional fixed effects in our model to adjust for regional differences. Second, though mental illnesses have a negative economic impact 55 , the opposite is true as well, in which economic disadvantage may lead to a greater mental illness 56 . During COVID-19, there have been negative consequences on individuals in different industry sectors who were more likely to lose their jobs due to the lockdown measures 57 with significant employment loss in occupations that require interpersonal contact 58 . Therefore, the loss of employment due to shutdowns may have a confounding effect on increased mental health issues.

In addition, the medical claims used in this study do not cover Medicare and Medicaid health insurance programs which creates a limitation on our data. Medicare covers most aged and disabled populations across the US, while Medicare covers a wider range of populations including low-income beneficiaries covering 30% of US population 59 . This limitation would impact the representativeness of results since our data misses some population groups in the US. We also note that our medical claims dataset does not provide demographics information such as race and ethnicity. This limitation restricts our analysis to only age and gender demographics information.

Despite the mentioned limitations, our results provide important policy implications from economic and social impacts. There is a notable mental health cost brought by non-pharmaceutical interventions, especially interventions that are extended to longer duration. Our results suggest that there should be considerations to the mental health cost through ensuring mental health treatment capacity.

Furthermore, we showed that number of patients’ daily visits had dropped right after lockdowns and then progressively increased in June and July 2020, supporting the findings of Refs. 60 , 61 . This suggests that people with mental health afflictions did not have the ability to seek immediate care during restrictive lockdowns. Findings suggest that policy interventions should be accompanied by strategies that facilitate mental health treatment reachability despite restrictive lockdowns, in order to avoid the exacerbated effect of delayed treatment.

Data availability

There is a Research Data Access and Services Agreement between Change Healthcare Operations, LLC and the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois, through which data access was granted. This work is exempt from review, as per the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign institutional review board process. Medical claims data analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because it is under the agreement between Change Healthcare, LLC and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. The NYTimes data analyzed during the current study is available in the NYTiems repository, https://github.com/nytimes/covid-19-data . The COVID-19 data analyzed during the current study is available in the COVIDVis repository, https://github.com/covidvis/covid19-vis/tree/master/data .

Thunström, L., Newbold, S. C., Finnoff, D., Ashworth, M. & Shogren, J. F. The benefits and costs of using social distancing to flatten the curve for COVID-19. J. Benefit-Cost Anal. 11 , 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1017/bca.2020.12 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

Anderson, R. M., Heesterbeek, H., Klinkenberg, D. & Hollingsworth, T. D. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? The Lancet 395 , 931–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5 (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fowler, J. H., Hill, S. J., Levin, R. & Obradovich, N. The effect of stay-at-home orders on COVID-19 cases and fatalities in the United States. MedRxiv 1 , 628. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.13.20063628 (2020).

Pfefferbaum, B. & North, C. S. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 383 , 510–512. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2008017 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

File, T. & Marlay, M. Living Alone has More Impact on Mental Health of Young Adults than Older Adults (United States Census Bureau, 2021).

Google Scholar

Elmer, T., Mepham, K. & Stadtfeld, C. Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS ONE 15 , e0236337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M. & Rauh, C. The Impact of the Coronavirus Lockdown on Mental Health: Evidence from the US. Cambridge Working Papers in Economics 2037 (University of Cambridge, 2020).

Wathelet, M. et al. Factors associated with mental health disorders among university students in France confined during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 3 , e2025591. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25591 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zhu, Y. et al. The risk and prevention of novel coronavirus pneumonia infections among inpatients in psychiatric hospitals. Neurosci. Bull. 36 , 299–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264-020-00476-9 (2020).

Melamed, O. C. et al. Physical health among people with serious mental illness in the face of COVID-19: Concerns and mitigation strategies. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 66 , 30–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.06.013 (2020).

Lee, M. et al. Human mobility trends during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. PLoS ONE 15 , 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241468 (2020).

Musinguzi, G. & Asamoah, B. O. The science of social distancing and total lock down: Does it work? Whom does it benefit? Electron. J. Gen. Med. 17 , 230. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejgm/7895 (2020).

Le, K. & Nguyen, M. The psychological burden of the covid-19 pandemic severity. Econom. Hum. Biol. 41 , 100979 (2021).

Czeisler, M. É. et al. Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation During the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 32 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020).

Abbott, A. COVID’s mental-health toll: How scientists are tracking a surge in depression. Nature 590 , 194–195. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-00175-z (2021).

Article CAS PubMed ADS Google Scholar

Giuntella, O., Hyde, K., Saccardo, S. & Sadoff, S. Lifestyle and mental health disruptions during COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118 , e2016632118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2016632118 (2021).

Devaraj, S. & Patel, P. C. Change in psychological distress in response to changes in reduced mobility during the early 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence of modest effects from the US. Soc. Sci. Med. 270 , 113615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113615 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Farkhad, B. F. & Albarracín, D. Insights on the implications of COVID-19 mitigation measures for mental health. Econom. Hum. Biol. 40 , 100963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2020.100963 (2021).

Brodeur, A., Clark, A. E., Fleched, S. & Powdthavee, N. COVID-19, lockdowns and well-being: Evidence from Google Trends. J. Public Econ. 193 , 104346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104346 (2021).

Serrano-Alarcón, M., Kentikelenis, A., Mckee, M. & Stuckler, D. Impact of covid-19 lockdowns on mental health: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in England and Scotland. Health Econ. 31 , 284–296 (2022).

Roehrig, C. Mental disorders top the list of the most costly conditions in the United States: \$201 billion. Health Aff. 35 , 1130–1135. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1659 (2016).

Bloom, D. et al. The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases. Geneva. Tech. Rep (World Economic Forum, 2011).

McKenzie, K. W. S. & Whitley, R. Social capital and mental health. Br. J. Psychiatry 181 , 280–283 (2002).

Berkman, L. F. & Syme, S. L. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am. J. Epidemiol. 109 , 186–204 (1979).

Ferwana, I. & Varshney, L. R. Social capital dimensions are differentially associated with COVID-19 vaccinations, masks, and physical distancing. PLoS ONE 16 , e0260818 (2021).

Simon, N. M., Saxe, G. N. & Marmar, C. R. Mental health disorders related to COVID-19-related deaths. JAMA 324 , 1493–1494 (2020).

Ross, L. & Bassett, D. Causation in neuroscience: Keeping mechanism meaningful. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 1 , 81–90 (2024).

Bommersbach, T. J., McKean, A. J., Olfson, M. & Rhee, T. G. National trends in mental health-related emergency department visits among youth, 2011–2020. JAMA 329 , 1469–1477 (2023).

Kuehn, B. M. Clinician shortage exacerbates pandemic-fueled “mental health crisis’’. JAMA 327 , 2179–2181 (2022).

Cantor, J. H., McBain, R. K., Ho, P. C., Bravata, D. M. & Whaley, C. Telehealth and in-person mental health service utilization and spending, 2019 to 2022. JAMA Health Forum 4 , e232645. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.2645 (2023).

Times, T. N. Y. Coronavirus (Covid-19) Data in the United States. Dataset (2021).

Brooks, S. K. et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet 395 , 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 (2020).

Keele, L. J., Small, D. S., Hsu, J. Y. & Fogarty, C. B. Patterns of effects and sensitivity analysis for differences-in-differences. http://arxiv.org/abs/1901.01869 (2019).

Zeldow, B. & Hatfield, L. A. Confounding and regression adjustment in difference-in-differences studies. Health Serv. Res. 56 , 932–941 (2021).

Angrist, J. D. & Pischke, J.-S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion (Princeton University Press, 2008).

Book Google Scholar

Goodman-Bacon, A. & Marcus, J. Using difference-in-differences to identify causal effects of COVID-19 policies. Survey Res. Methods 14 , 153–158. https://doi.org/10.18148/srm/2020.v14i2.7723 (2020).

Rambachan, A. & Roth, J. An Honest Approach to Parallel Trends. Unpublished (2020).

Hartnett, K. P. et al. Impact of the covid-19 pandemic on emergency department visits—United States, January 1, 2019–May 30, 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 23 , 699–704 (2020).

Kocher, K. E. & Macy, M. L. Emergency department patients in the early months of the coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) pandemic-what have we learned? JAMA Health Forum 6 , e200705 (2020).

Friedson, A. I., McNichols, D., Sabia, J. J. & Dave, D. Did California’s Shelter-in-Place Order Work? Early Coronavirus-Related Public Health Effects. Working Paper 26992 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020).

Cucinotta, D. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Bio-med. 91 , 157–160. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397 (2020).

Layard, R. et al. When to Release the Lockdown? A Wellbeing Framework for Analysing Costs and Benefits IZA. Discussion Papers 13186 (Institute of Labor Economics, 2020).

Gupta, R. et al. Changes in sleep pattern and sleep quality during COVID-19 lockdown. Indian J. Psychiatry 62 , 370–378. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_523_20 (2020).

Gualano, M. R., Lo Moro, G., Voglino, G., Bert, F. & Siliquini, R. Effects of Covid-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 4779. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134779 (2020).

Xiao, H., Zhang, Y., Kong, D., Li, S. & Yang, N. The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med. Sci. Monit. 26 , 1–8. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.923549 (2020).

Joshi, G. & Sharma, G. Burnout: A risk factor amongst mental health professionals during COVID-19. Asian J. Psychiatry 54 , 102300 (2020).

Aguiar, J. et al. Parental burnout and the COVID-19 pandemic: How Portuguese parents experienced lockdown measures. Fam. Relat. 70 , 927–938 (2021).

Murthy, V. H. Confronting health worker burnout and well-being. N. Engl. J. Med. 387 , 577–579 (2022).

Bailhache, M., Monnier, M. & Moulin, F. E. A. Emotional and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms of preterm vs full-term children during covid-19 pandemic restrictions. Pediatr. Res. 92 , 1749–1756 (2022).

Huang, X. et al. The impact of lockdown timing on COVID-19 transmission across US counties. EClinicalMedicine 38 , 101035 (2021).

Loewenthal, G. et al. COVID-19 pandemic-related lockdown: Response time is more important than its strictness. EMBO Mol. Med. 12 , e13171. https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.202013171 (2020).

Gutkowski, V. A. Lockdown Responses to COVID-19. Tech. Rep. (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2021).

Ferraresi, M., Kotsogiannis, C., Rizzod, L. & Secomandi, R. The ‘Great Lockdown’ and its determinants. Econ. Lett. 197 , 109628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2020.109628 (2020).

JoAnn, P., Dooley, D. & Huh, J. Income volatility and psychological depression. Am. J. Community Psychol. 43 , 57–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9219-3 (2009).

Knapp, M. & Wong, G. Economics and mental health: The current scenario. World Psychiatry 19 , 3–14 (2020).

Fana, M., Pérez, S. T. & Fernández-Macías, E. Employment impact of Covid-19 crisis: From short term effects to long terms prospects. J. Ind. Bus. Econom. 47 , 391–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40812-020-00168-5 (2020).

Montenovo, L. et al. Determinants of Disparities in COVID-19 Job Losses NBER. Working Paper 27132 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021).

Klees, B. S. & Curtis, C. A. Brief Summaries of Medicare & Medicaid. Summary Report (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services, 2020).

Trinkl, J. & Muñoz del Río, A. Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic on Visit Patterns for Anxiety and Depression (2020).

Patel, S. Y. et al. Trends in outpatient care delivery and telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Intern. Med. 181 , 388–391. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5928 (2020).

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Change Healthcare team, Craig Midgett, Mina Atia, Andrew Harris, Anil Konda, Tim Suther, and Jaideep Kulkarni for facilitating our access to medical claims data and for their help in large-scale analysis.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Coordinated Science Laboratory, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, 61801, USA

Ibtihal Ferwana & Lav R. Varshney

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

IF was responsible for data curation, formal analysis, writing an original draft, and reviewing. LV was responsible for conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, reviewing, and editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ibtihal Ferwana .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ferwana, I., Varshney, L.R. The impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on mental health patient populations in the United States. Sci Rep 14 , 5689 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55879-9

Download citation

Received : 14 April 2023

Accepted : 27 February 2024

Published : 07 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55879-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Many Americans continue to experience mental health difficulties as pandemic enters second year

Note: For the latest information on this topic, read our 2022 post .

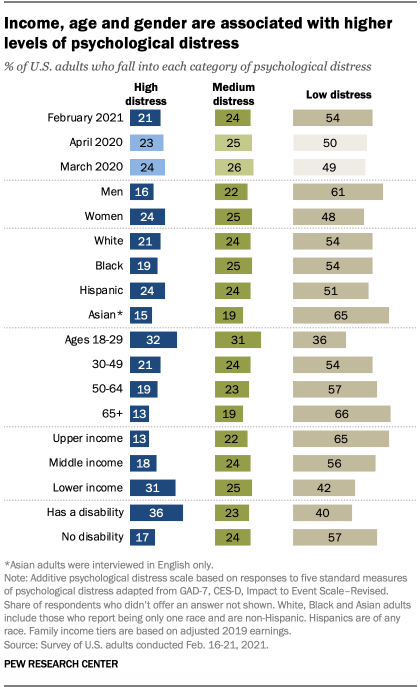

One year into the societal convulsions caused by the coronavirus pandemic , about a fifth of U.S. adults (21%) are experiencing high levels of psychological distress, including nearly three-in-ten (28%) among those who say the outbreak has changed their lives in “a major way.” The share of the public experiencing psychological distress has edged down slightly since March 2020 but remains elevated among some groups in the population. Concerns about both the personal health and the financial threats from the pandemic are associated with high levels of psychological distress.

This assessment of the public’s psychological reaction to the COVID-19 outbreak is based on surveys of members of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) conducted online several times since March 2020. The mental health questions were included on three surveys. The first survey was conducted with 11,537 U.S. adults March 19-24, 2020; a second survey with the question series was conducted April 20-26, 2020, with a sample of 10,139 adults; and the most recent survey was conducted Feb. 16-21, 2021, among 10,121 adults. This analysis also includes questions asked in a survey conducted Jan. 19-24, 2021, with a sample of 10,334 adults.

The ATP is an online survey panel that is recruited through national random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The surveys are weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Here is more information about the ATP.

The psychological distress index used here measures the total amount of mental distress that individuals reported experiencing in the past seven days. The low distress category in the index includes about half of the sample; very few in that group said they were experiencing any of the types of distress most or all of the time. The middle category includes roughly one-quarter of the sample, while the high distress category includes 21%, down slightly from 24% in March 2020. A large majority of those in the high distress group reported experiencing at least one type of distress most or all of the time in the past seven days.

The questions used to measure the levels of psychological distress were developed with the help of the COVID-19 and mental health measurement group from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH): M. Daniele Fallin (JHSPH), Calliope Holingue (Kennedy Krieger Institute, JHSPH), Renee Johnson (JHSPH), Luke Kalb (Kennedy Krieger Institute, JHSPH), Frauke Kreuter (University of Maryland, Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich), Elizabeth Stuart (JHSPH), Johannes Thrul (JHSPH) and Cindy Veldhuis (Columbia University).

Here are the mental health questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and the detailed survey methodology statements for March 2020 , late April 2020 and February 2021 .

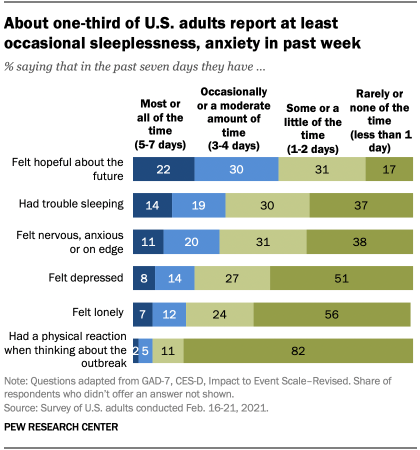

The index of psychological distress is based on a set of five questions asking about anxiety, sleeplessness, depression, loneliness and physical symptoms of distress. Except for the last item, the questions do not explicitly mention the pandemic. But experts have documented that fear and isolation associated with the pandemic have been responsible for a surge of anxiety and depression over the past year. And on the one item that asks about physical reactions when thinking about coronavirus outbreak – such as sweating, trouble breathing, nausea or a pounding heart – 17% report having such reactions at least “some or a little of the time” in the past week.

The five items were combined to create an index, which was then grouped into three categories: high, medium and low distress. The questions were part of a survey conducted online Feb. 16-21 among 10,121 members of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel. Most of those interviewed had also participated in last year’s surveys about reactions to the pandemic.

High levels of distress are being experienced by those who say the coronavirus outbreak is a major threat to their personal financial situation (34% high distress) or to their personal health (28%). Psychological distress is especially common among adults ages 18 to 29 (32%), those with lower family incomes (31%) and those who have a disability or health condition that keeps them from participating fully in work, school, housework or other activities (36%).

The share of adults falling into the high distress group (21%) is now slightly lower than in March of last year: It was 24% then, near the beginning of coronavirus-related lockdowns in the U.S.

Underneath the relative stability of the index, considerable change has occurred. About six-in-ten (61%) of those interviewed in both April 2020 and February 2021 remained in the same category of the index. Just over a fifth (22%) moved from a higher to a lower category of distress, while 16% moved from a lower to a higher category. Of all panelists interviewed in both April 2020 and February 2021, 12% were classified as high in psychological distress in both interviews and 40% were low in both.

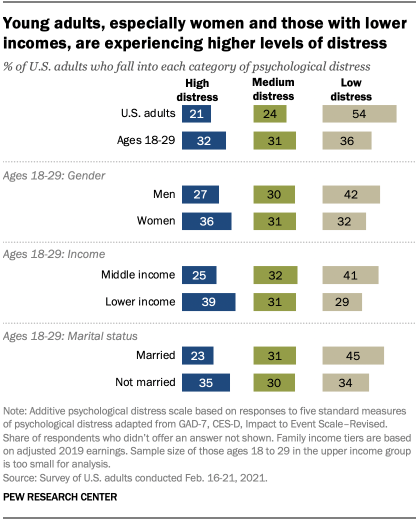

Young people have been a particular group of concern during the pandemic for mental health professionals, and young adults stand out in the current survey for exhibiting higher levels of psychological distress than other age groups. The shutdowns have disrupted job opportunities, college experiences, and the mixing and mingling that marks the transition to adulthood. Among adults ages 18 to 29, women (36%) and those with lower incomes (39%) are especially likely to be in the high distress group. In this age group, those who are unmarried fare worse than the married (35% vs. 23% experienced high levels of distress, respectively).

Adults ages 18 to 29 are especially likely to report anxiety, depression or loneliness compared with other age groups. For example, 45% of those under 30 describe being “nervous, anxious or on edge” at least “occasionally or a moderate amount of time” during the past seven days; among those 30 and older, 28% do so.

Not surprisingly, psychological distress is higher among those who express concern about becoming ill with COVID-19 or believe that the disease is a major threat to their personal health. Among those who are “very concerned” that they might get infected and require hospitalization, 27% score high in psychological distress, compared with just 14% among those who are not too or not at all concerned. Similarly, 27% of those who see the disease as a major threat to their personal health score high in psychological distress, compared with 11% who say it is not a threat. Distress levels are also higher among those who perceive the sign-up process for a coronavirus vaccine in their area as unfair or who say that it has not been easy to find information about the process.

As much as concern about the health implications of the pandemic may be affecting the mental health status of many Americans, financial troubles are also a strong correlate of psychological distress. Pew Research Center surveys, including this one, have documented the substantial negative impact of the pandemic on the financial situation of many Americans. A January survey found that more than four-in-ten adults said that they or someone in their household had lost a job or wages since the beginning of the outbreak, and significant shares of the unemployed acknowledged the emotional toll it had taken.

Among those interviewed in the current survey who say that the pandemic is a major threat to their personal financial situation, 34% are classified as being in high psychological distress. Even greater levels of distress are observed among those who said in a January interview that they worry about how to pay their bills “every day” (40% high psychological distress) or who said they are in “poor” shape financially (44%).

Note: Here are the mental health questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and the detailed survey methodology statements for March 2020 , late April 2020 and February 2021 .

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- COVID-19 & Science

- Happiness & Life Satisfaction

Scott Keeter is a senior survey advisor at Pew Research Center .

How Americans View the Coronavirus, COVID-19 Vaccines Amid Declining Levels of Concern

Online religious services appeal to many americans, but going in person remains more popular, about a third of u.s. workers who can work from home now do so all the time, how the pandemic has affected attendance at u.s. religious services, mental health and the pandemic: what u.s. surveys have found, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

- COVID-19 and your mental health

Worries and anxiety about COVID-19 can be overwhelming. Learn ways to cope as COVID-19 spreads.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, life for many people changed very quickly. Worry and concern were natural partners of all that change — getting used to new routines, loneliness and financial pressure, among other issues. Information overload, rumor and misinformation didn't help.

Worldwide surveys done in 2020 and 2021 found higher than typical levels of stress, insomnia, anxiety and depression. By 2022, levels had lowered but were still higher than before 2020.

Though feelings of distress about COVID-19 may come and go, they are still an issue for many people. You aren't alone if you feel distress due to COVID-19. And you're not alone if you've coped with the stress in less than healthy ways, such as substance use.

But healthier self-care choices can help you cope with COVID-19 or any other challenge you may face.

And knowing when to get help can be the most essential self-care action of all.

Recognize what's typical and what's not

Stress and worry are common during a crisis. But something like the COVID-19 pandemic can push people beyond their ability to cope.

In surveys, the most common symptoms reported were trouble sleeping and feeling anxiety or nervous. The number of people noting those symptoms went up and down in surveys given over time. Depression and loneliness were less common than nervousness or sleep problems, but more consistent across surveys given over time. Among adults, use of drugs, alcohol and other intoxicating substances has increased over time as well.

The first step is to notice how often you feel helpless, sad, angry, irritable, hopeless, anxious or afraid. Some people may feel numb.

Keep track of how often you have trouble focusing on daily tasks or doing routine chores. Are there things that you used to enjoy doing that you stopped doing because of how you feel? Note any big changes in appetite, any substance use, body aches and pains, and problems with sleep.

These feelings may come and go over time. But if these feelings don't go away or make it hard to do your daily tasks, it's time to ask for help.

Get help when you need it

If you're feeling suicidal or thinking of hurting yourself, seek help.

- Contact your healthcare professional or a mental health professional.

- Contact a suicide hotline. In the U.S., call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline , available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Or use the Lifeline Chat . Services are free and confidential.

If you are worried about yourself or someone else, contact your healthcare professional or mental health professional. Some may be able to see you in person or talk over the phone or online.

You also can reach out to a friend or loved one. Someone in your faith community also could help.

And you may be able to get counseling or a mental health appointment through an employer's employee assistance program.

Another option is information and treatment options from groups such as:

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Self-care tips

Some people may use unhealthy ways to cope with anxiety around COVID-19. These unhealthy choices may include things such as misuse of medicines or legal drugs and use of illegal drugs. Unhealthy coping choices also can be things such as sleeping too much or too little, or overeating. It also can include avoiding other people and focusing on only one soothing thing, such as work, television or gaming.