- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

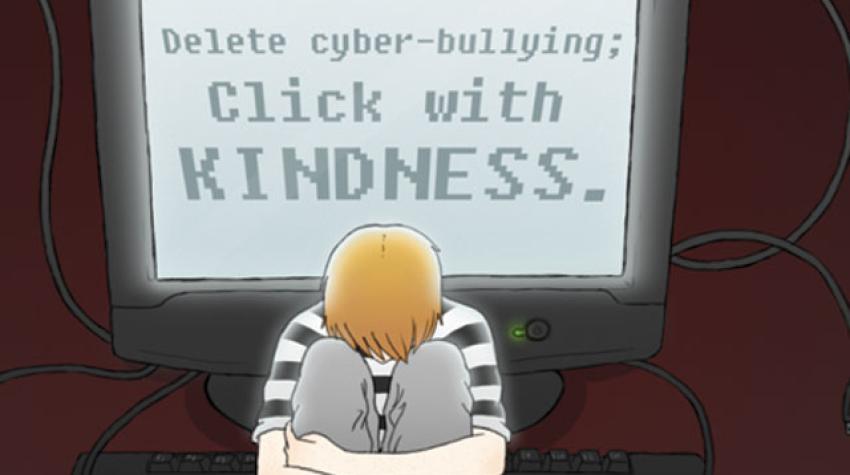

The Psychology of Cyberbullying

Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of The Anxiety Workbook and founder of the website About Social Anxiety. She has a Master's degree in clinical psychology.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ArlinCuncic_1000-21af8749d2144aa0b0491c29319591c4.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

Adah Chung is a fact checker, writer, researcher, and occupational therapist.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Adah-Chung-1000-df54540455394e3ab797f6fce238d785.jpg)

Verywell / Nez Riaz

Forms of Cyberbullying

Why do people cyberbully.

- How Cyberbullying Is Different

Effects of Cyberbullying

Characteristics of victims, how to deal with a cyber bully, what if you are the cyberbully.

Cyberbullying refers to the use of digital technology to cause harm to other people. This typically involves the use of the Internet , but may also take place through mobile phones (e.g., text-based bullying). Social media is one of the primary channels through which cyberbullying takes place, including Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, and more.

Cyberbullying has been deemed a public health problem, with the prevalence of cyberbullying doubling from 2007 to 2019, and 59% of teens in the United States reporting that they have been bullied or harassed online.

In general, cyberbullying is a recent issue with increasing numbers of people using the Internet. Much of the focus of research is on how cyberbullying affects the victim, without a lot of focus on how to cope with cyberbullying, how to reduce cyberbullying, or what to do if you are a cyberbully yourself.

Cyberbullies can appear through social media, inside wellness apps, in public forums, during gaming, and more. However, more personal cyberbullies will operate through email, texting, or direct messaging.

It has been argued that cyberbullying is defined in light of five main criteria: intention to harm, repetition, power imbalance, anonymity, and publicity.

Intention to harm

Cyberbullies generally have the intention to cause harm when they engage in online bullying. However, bullying can still take place without intention if a victim reasonably perceives actions to be harmful.

Repetition is a hallmark characteristic of cyberbullying. This refers to repeated actions on the part of the bully, but also the fact that material that is shared on the Internet could last much longer than the original post through sharing and re-posting by others. This is especially true in the case of sharing personal information or photos as a form of cyberbullying.

Power Imbalance

One of the other hallmark traits of bullying is that victims usually experience a power imbalance with their bully. The power differential can be due to the bully having more status, wealth, popularity, talent, etc. Cyberbullying can be severe and relentless, and the victim often has little control to stop the bullying.

Some cyberbullies make use of anonymity to hide behind their computer screen when they engage in bullying. In this case, there is no need for a power imbalance in the relationship between the bully and the victim, making it possible for anyone to be a bully. Anonymity allows the bully to engage in an increased degree of cruelty that would not occur if their identity was known.

Finally, another trait of cyberbullying is that it sometimes involves the use of publicity. This is especially true for those who choose to publicly humiliate or shame someone which can be especially impactful if it takes place in a public forum with the potential to reach a large audience.

What are the various forms of cyberbullying? Below are the types of cyberbullying that exist.

- Flaming : Flaming (or roasting) refers to using inflammatory language and hurling insults at someone or broadcasting offensive messages about them in the hopes of eliciting a reaction. One example would be Donald Trump's use of the phrases "Crooked Hilary" or "Sleepy Joe Biden."

- Outing : Outing involves sharing personal or embarrassing information about someone on the Internet. This type of cyberbullying usually takes place on a larger scale rather than one-to-one or in a smaller group.

- Trolling : Trolling refers to posting content or comments with the goal of causing chaos and division. In other words, a troll will say something derogatory or offensive about a person or group, with the sole intention of getting people riled up. This type of cyberbully enjoys creating chaos and then sitting back and watching what happens.

- Name Calling : Name-calling involves using offensive language to refer to other people. Reports show that 42% of teens said they had been called offensive names through their mobile phone or on the Internet.

- Spreading False Rumors : Cyberbullies who spread false rumors make up stories about individuals and then spread these false truths online. In the same report, 32% of teens said that someone had spread false rumors about them on the Internet.

- Sending Explicit Images or Messages : Cyberbullies may also send explicit images or messages without the consent of the victim.

- Cyber Stalking/Harassing/Physical Threats : Some cyberbullies will repeatedly target the same people through cyberstalking, cyber harassment, or physical threats. In that same report, 16% of teens reported having been the victim of physical threats on the Internet.

Why do people engage in cyberbullying? There can be numerous different factors that lead to someone becoming a cyberbully.

Mental Health Issues

Cyberbullies may be living with mental health issues that relate to their bullying or make it worse. Examples include problems with behavioral issues such as aggression , hyperactivity, or impulsivity , as well as substance abuse .

In addition, those with personality features resembling the " dark tetrad " of psychopathy , Machiavellianism (deceptive, manipulative), sadism (deriving pleasure from harming others), and narcissism may be at risk for cyberbullying. These individuals tend to violate social norms, have a low level of empathy for other people, and may bully others as a way to increase their sense of power or worth.

Victims of Bullying

Cyberbullies sometimes become bullies after having experienced cyberbullying themselves. In this way, they may be looking to feel more in control or lash out after feeling victimized and being unable to retaliate to the original bully. It may feel like a dichotomous world of "bully or be bullied," not having the insight that there is another pathway.

Result of Conflicts or Breakups

Cyberbullying that takes place between two people who were previously friends or in a relationship may be triggered by conflicts in the friendship or the breakdown of the relationship . In this way, this type of cyberbullying might be viewed as driven by anger, jealousy, or revenge.

Boredom or Trying Out a New Persona

It has been suggested that some people engage in cyberbullying due to boredom or the desire to try out a new persona on the Internet. This is more likely among young adults or teenagers who are still developing their sense of identity. This type of cyberbullying would typically be anonymous.

Loneliness or Isolation

Cyberbullies may also be people who struggle with feeling isolated or lonely in society. If they feel ignored by others, they may lash out as a way to get attention and feel better, or vent their rage at society.

Why People Become Cyberbullies

While some people are bullies both in real life and online, there are others who only become bullies in the digital space. Why is this the case? Why would someone bully others online when they would never do that in their everyday life? There are multiple possible explanations for this behavior.

Non-Confrontational & Anonymous

The first reason why people may become bullies online when they would not bully in their everyday life has to do with the nature of the Internet. A person can bully others online and remain completely anonymous. Clearly, this is not possible with traditional bullying.

In addition, online bullying can be done in a non-confrontational way, particularly if it is anonymous. This means that a cyberbully may skip about the Internet leaving nasty comments and not stick around to hear the replies.

No Need for Popularity or Physical Dominance

In order to be a bully in real life, you typically need to have some advantage over your victim. This might mean that you are physically larger than them. It might mean that you are more popular than them. Or, it might mean that you have some sort of power imbalance over them.

In contrast, anyone can be a cyberbully. There is no need to have physical dominance or popularity. This means that people who want to bully can easily do it on the Internet regardless of their status in their real life.

No Barrier to Entry

Similar to the concept of there being no need to be dominant or popular, there is also a very low barrier to entry to becoming a cyberbully. Anyone with access to the Internet can get started. Friends are defined loosely online, which creates a situation that makes it very easy to bully others.

No Feedback From Victim

Finally, the last reason why people who do not bully in real life may engage in cyberbullying has to do with a lack of feedback from their victim. Cyberbullies usually engage in bullying over an extended period of time, largely because there is generally less personal feedback from the victim and less retaliation compared to face-to-face interaction. Someone, who in real life would see the impact on their victim and back off, may not do the same in the case of cyberbullying.

How Cyberbullying Differs From In-Person Bullying

In the case of cyberbullying, the victim generally has no escape from the abuse and harassment. Unlike real life encounters, online bullying and the Internet never really shut down and bullying may be unrelenting.

This can make victims feel as though they have no escape, particularly if the bullying involves sharing of their personal information or when something posted about them goes viral. This type of bullying can go on for an extended period of time.

There are numerous effects that may be seen in those who are dealing with cyberbullying. It can be helpful to know what to expect to see in a victim, as this can be one way to identify when someone is being bullied online.

Some of these effects are even stronger than what is seen with traditional bullying, as the victim often cannot escape the abusive situation. They may include:

- Feelings of distress and anxiety about the bullying

- Increased feelings of depression and mood swings

- Problems falling asleep or staying asleep (e.g., insomnia)

- Increased feelings of fearfulness

- Feelings of low self-esteem or self-worth

- Social isolation, withdrawing from friend groups, or spending a lot of time alone

- Avoiding doing things that they used to enjoy

- Increased feelings of anger, irritability, or angry outbursts

- Poor academic performance

- Problems in relationships with family members and friends

- Symptoms of post-traumatic stress

- Self-harm (e.g., cutting, hitting yourself, headbanging)

- Suicidal ideation or suicide attempt

- Substance abuse

There are indeed some common aspects of the victim that tend to repeat themselves including the following characteristics:

- Teens and young adults are the most at risk.

- In the case of spreading false rumors and being the recipient of explicit images, girls are more likely to be victims.

- People who are gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender may be victims more often.

- Those who are shy, socially awkward, or don't fit in easily may become victims.

- People from lower-income households are more likely to be victims.

- People who use the Internet constantly are more likely to be victims of online bullies.

Anyone can become a victim of cyberbullying, even people who are considered public figures. People who have large followings on social media often tend to become targets for cyberbullies.

There are many ways to deal with a cyberbully as a child, an adult, or a parent of a child being bullied on the Internet. Let's take a look at each of these issues separately.

As a Child or Teen

Cyberbullying can come from classmates, people in chatrooms, gamers, family members, or anonymous internet trolls. It can be mildly annoying to severely threatening. If you are being harassed, bullied, stalked, or threatened, here are a few things we recommend.

- Talk to an adult that you trust for assistance (parents, a teacher, the principal, or another adult you can rely on). If the bully is making threats, the police may need to get involved.

- Save every form of communication that the bully is sending to you (emails, pictures, texts, links, documents, etc.) and take screenshots if needed.

- Do not feed the lions. Your response can be like "food" for the bully and makes them want to harass you even more.

- Do not give any personal information, such as your address, birthday, phone number, social security number, bank account information, etc.

- Even if you willingly participated in a conversation with someone online, you did not ask to be bullied. Don't let guilt or embarrassment stop you from getting help. It is not your fault.

As a Parent

If your child is being bullied online, the best course of action is to instruct them not to respond to the Internet bully. In addition, tell them to document each instance of cyberbullying by saving text messages, emails, photos, and any other forms of communication. This can be done using screenshots if necessary. Ask your child to forward this information to you so that you have records of everything.

Next, if the bullying originates from a school contact, report the instances of cyberbullying to the teacher, principal, or administrative staff at your school. In the case of extreme bullying or threats, you should also report the bullying behavior to the police.

Finally, it's important to reassure your child that they are not to blame for the bullying online. Some victims may feel that their behavior created the problem or that they are somehow to blame. For this reason, it's important to make sure your child knows that what happened is not their fault.

As an Adult

Many of the same principles as above will apply to your situation as an adult dealing with a cyberbully.

First of all, be sure to keep records of all instances of bullying, whether they come through your text messages, messenger chats, in Facebook groups, Instagram DMs, or other online sources. Take screenshots and keep folders on your computer with evidence of the cyberbullying.

Next, if you know the source of the cyberbullying, determine whether there is a course of action you can take with regard to that person. For example, if it is a work colleague or supervisor, is there someone in HR at work that you can speak to? If it is a family member, is there a way to bring up this issue to other family members to ask for their support? Finally, if it is someone you only know online, can you block and delete them from all your social media?

The best course of action will be to ignore the cyberbullying as much as possible. However, if you are receiving threats, then you will want to report this to the police, along with the evidence that you have collected.

As a Community

It is not enough for victims of cyberbullying to deal with their bullies and try to find solutions. Oftentimes, these victims are emotionally distraught and unable to find help.

It is our job as a community to work toward establishing systems that prevent cyberbullying from taking place at all. Some potential ideas for initiatives are listed below.

Kids and teens who are cyberbullied are still learning how to regulate emotions and deal with social situations. Cyberbullying at this age could have lasting permanent effects. Mental health resources should be put in place to help victims of cyberbullying manage their mental health.

Cyberbullying thrives on status and approval. Cyberbullies will stop when social rejection of cyberbullying becomes so widespread and prevalent that they no longer have anything to gain. This means that every instance of online bullying that is witnessed (especially in the case of troll comments) should be ignored. In addition, there should be awareness campaigns that online bullying is not only not acceptable, but that it is a sign of weak social status.

Schools are the point of contact for parents trying to help their children who are being cyberbullied. For this reason, schools should have programs and protocols in place to immediately and swiftly deal with cyberbullying. Parents should not have to ask multiple times for help without receiving it.

What happens if you are the cyberbully yourself? If you are engaging in cyberbullying and want to stop, you'll need to take stock of your reasons for engaging in the bullying, as this will inform your best course of action. Let's consider each of these and what you could do.

You Are Struggling With a Mental Health Issue

If you feel as though your mental health is not in good shape and this might be contributing to your cyberbullying behavior, make an appointment with your doctor to discuss your options. For example, if you struggle with anger or aggression, you might benefit from an anger management program .

If you have low empathy for others or identify with the traits of psychopathy , then it may be harder for you to find insight and desire to change. However, you could try to channel your energy into different pursuits.

For example, if you are cyberbullying someone because it gives you a thrill, is there a hobby you could take up or business that you could start that would give you a thrill without consequences for another person?

You Were a Victim Yourself

If you were once a victim yourself of cyberbullying, and that is the reason why you are now engaging in cyberbullying yourself, it's time to take a look at your options for change. It could be that you have unresolved anger that needs to be taken out in a different way.

You may also feel more powerful when you bully, which helps you to stop feeling like a victim. In that case, you may need to work on other ways to improve your sense of self so that you can stop feeling helpless and out of control. After all, you were once a victim yourself, and you know how that feels.

Rather than continue a cycle of bullying and victimhood, you have a chance to break the cycle and rise above your past. You'll likely need help to do that, most likely in the form of professional assistance to work through your past.

You Had a Conflict or Breakup

If you are cyberstalking someone because of a conflict you had with them or a bad breakup, it's time to re-evaluate your behavior. What do you hope to achieve from your cyberstalking? Again, you may need the help of a professional to work through your feelings that have led to this behavior.

You Are Lonely or Isolated

What if you are just lonely, and this is the reason you have resorted to cyberbullying? This type of bullying falls into the arena of people who may feel like the world has passed them by. Or that everyone else is out there enjoying life while you are alone.

In this case, find ways to start building up your in-person social connections. Join a club, volunteer somewhere, or take up a hobby to meet other people like yourself.

You Are Bored

If you are cyberbullying because you are bored (and you're not a psychopath), then you'll want to consider why you think it is acceptable to hurt someone else in exchange for making yourself less bored.

Certainly, lots of people are bored in the world but they never cyberbully. Take up a hobby, learn a second language, or find something to do.

A Word From Verywell

If you are a victim of cyberbullying, know that you are not alone and there are options to help. If you are struggling, you can visit the following.

- The CyberBullyHotline

- 1-800-Victims

- StopBullying.gov

Finally, if you are a cyberbully yourself, it's never too late to change. Examine your reasons for being a bully, and see if you can find some alternatives to stop the behavior.

Pacer's National Bullying Prevention Center. Bullying statistics .

Pew Research Center. A majority of teens have experienced some form of cyberbullying .

Nocentini A, Calmaestra J, Schultze-Krumbholz A, Scheithauer H, Ortega R, Menesini E. Cyberbullying: Labels, behaviours and definition in three European countries . Aust J Guid Couns . 2010;20(2):129-142. doi:10.1375/ajgc.20.2.129

Politico. How the psychology of cyberbullying explains Trump's tweets .

Skilbred-Fjeld S, Reme SE, Mossige S. Cyberbullying involvement and mental health problems among late adolescents . Cyberpsychol J Psychosoc Res Cyberspace. 2020 ; 14(1). doi:10.5817/CP2020-1-5

Brown WM, Hazraty S, Palasinski M. Examining the dark tetrad and its links to cyberbullying . Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw . 2019;22(8):552-557. doi:10.1089/cyber.2019.0172

Slonje R, Smith P, Frisén A. The nature of cyberbullying, and strategies for prevention . Computers Hum Behav . 2013;29:26–32. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.05.024

König A, Gollwitzer M, Steffgen G. Cyberbullying as an act of revenge? Aust J Guid Couns. 2010;20(2):210-224. doi:10.1375/ajgc.20.2.210

Varjas K, Talley J, Meyers J, Parris L, Cutts H. High school students' perceptions of motivations for cyberbullying: An exploratory study . West J Emerg Med . 2010;11(3):269-273.

McLoughlin L, Hermens D. Cyberbullying and social connectedness . Front Young Minds . 2018;6:54. doi:10.3389/frym.2018.00054

Nixon CL. Current perspectives: The impact of cyberbullying on adolescent health . Adolesc Health Med Ther . 2014;5:143-158. doi:10.2147/AHMT.S36456

American Psychological Association. Beware of cyberbullying .

Psychology Today. Cyberbullying. From the playground to "Insta" .

By Arlin Cuncic, MA Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of The Anxiety Workbook and founder of the website About Social Anxiety. She has a Master's degree in clinical psychology.

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > BJPsych Bulletin

- > The Psychiatrist

- > Volume 37 Issue 5

- > Cyberbullying and its impact on young people's emotional...

Article contents

The nature of cyberbullying, the impact of cyberbullying on emotional health and well-being, technological solutions, asking adults for help, cyberbullying and its impact on young people's emotional health and well-being.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 January 2018

The upsurge of cyberbullying is a frequent cause of emotional disturbance in children and young people. The situation is complicated by the fact that these interpersonal safety issues are actually generated by the peer group and in contexts that are difficult for adults to control. This article examines the effectiveness of common responses to cyberbullying.

Whatever the value of technological tools for tackling cyberbullying, we cannot avoid the fact that this is an interpersonal problem grounded in a social context.

Practitioners should build on existing knowledge about preventing and reducing face-to-face bullying while taking account of the distinctive nature of cyberbullying. Furthermore, it is essential to take account of the values that young people are learning in society and at school.

Traditional face-to-face bullying has long been identified as a risk factor for the social and emotional adjustment of perpetrators, targets and bully victims during childhood and adolescence; Reference Almeida, Caurcel and Machado 1 - Reference Sourander, Brunstein, Ikomen, Lindroos, Luntamo and Koskelainen 6 bystanders are also known to be negatively affected. Reference Ahmed, Österman and Björkqvist 7 - Reference Salmivalli 9 The emergence of cyberbullying indicates that perpetrators have turned their attention to technology (including mobile telephones and the internet) as a powerful means of exerting their power and control over others. Reference Smith, Mahdavi, Carvalho, Fisher, Russell and Tippett 10 Cyberbullies have the power to reach their targets at any time of the day or night.

Cyberbullying takes a number of forms, to include:

• flaming: electronic transmission of angry or rude messages;

• harassment: repeatedly sending insulting or threatening messages;

• cyberstalking: threats of harm or intimidation;

• denigration: put-downs, spreading cruel rumours;

• masquerading: pretending to be someone else and sharing information to damage a person’s reputation;

• outing: revealing personal information about a person which was shared in confidence;

• exclusion: maliciously leaving a person out of a group online, such as a chat line or a game, ganging up on one individual. Reference Schenk and Fremouw 11

Cyberbullying often occurs in the context of relationship difficulties, such as the break-up of a friendship or romance, envy of a peer’s success, or in the context of prejudiced intolerance of particular groups on the grounds of gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation or disability. Reference Hoff and Mitchell 12

A survey of 23 420 children and young people across Europe found that, although the vast majority were never cyberbullied, 5% were being cyberbullied more than once a week, 4% once or twice a month and 10% less often. Reference Livingstone, Haddon, Anke Görzig and Ólafsson 13 Many studies indicate a significant overlap between traditional bullying and cyberbullying. Reference Perren, Dooley, Shaw and Cross 5 , Reference Sourander, Brunstein, Ikomen, Lindroos, Luntamo and Koskelainen 6 , Reference Kowalski and Limber 14 , Reference Ybarra and Mitchell 15 However, a note of caution is needed when interpreting the frequency and prevalence of cyberbullying. As yet, there is no uniform agreement on its definition and researchers differ in the ways they gather their data, with some, for example, asking participants whether they have ‘ever’ been cyberbullied and others being more specific, for example, ‘in the past 30 days’.

Research consistently identifies the consequences of bullying for the emotional health of children and young people. Victims experience lack of acceptance in their peer groups, which results in loneliness and social isolation. The young person’s consequent social withdrawal is likely to lead to low self-esteem and depression. Bullies too are at risk. They are more likely than non-bullies to engage in a range of maladaptive and antisocial behaviours, and they are at risk of alcohol and drugs dependency; like victims, they have an increased risk of depression and suicidal ideation. Studies among children Reference Escobar, Fernandez-Baen, Miranda, Trianes and Cowie 2 - Reference Kaltiala-Heino, Rimpalä, Rantanen and Rimpalä 4 , Reference Kumpulainen, Rasanen and Henttonen 16 and adolescents Reference Salmivalli, Lappalainen and Lagerspetz 17 , Reference Sourander, Helstela, Helenius and Piha 18 indicate moderate to strong relationships between being nominated by peers as a bully or a victim at different time points, suggesting a process of continuity. The effects of being bullied at school can persist into young adulthood. Reference Isaacs, Hodges and Salmivalli 19 , Reference Lappalainen, Meriläinen, Puhakka and Sinkkonen 20

Studies demonstrate that most young people who are cyberbullied are already being bullied by traditional, face-to-face methods. Reference Sourander, Brunstein, Ikomen, Lindroos, Luntamo and Koskelainen 6 , Reference Dooley, Pyzalski and Cross 21 - Reference Riebel, Jaeger and Fischer 23 Cyberbullying can extend into the target’s life at all times of the day and night and there is evidence for additional risks to the targets of cyberbullying, including damage to self-esteem, academic achievement and emotional well-being. For example, Schenk & Fremouw Reference Schenk and Fremouw 11 found that college student victims of cyberbullying scored higher than matched controls on measures of depression, anxiety, phobic anxiety and paranoia. Studies of school-age cyber victims indicate heightened risk of depression, Reference Perren, Dooley, Shaw and Cross 5 , Reference Gradinger, Strohmeier and Spiel 22 , Reference Juvonen and Gross 24 of psychosomatic symptoms such as headaches, abdominal pain and sleeplessness Reference Sourander, Brunstein, Ikomen, Lindroos, Luntamo and Koskelainen 6 and of behavioural difficulties including alcohol consumption. Reference Mitchell, Ybarra and Finkelhor 25 As found in studies of face-to-face bullying, cyber victims report feeling unsafe and isolated, both at school and at home. Similarly, cyberbullies report a range of social and emotional difficulties, including feeling unsafe at school, perceptions of being unsupported by school staff and a high incidence of headaches. Like traditional bullies, they too are engaged in a range of other antisocial behaviours, conduct disorders, and alcohol and drug misuse. Reference Sourander, Brunstein, Ikomen, Lindroos, Luntamo and Koskelainen 6 , Reference Hinduja and Patchin 26

The most fundamental way of dealing with cyberbullying is to attempt to prevent it in the first place, through whole-school e-safety policies Reference Campbell 27 - Reference Stacey 29 and through exposure to the wide range of informative websites that abound (e.g. UK Council for Child Internet Safety (UKCCIS; www.education.gov.uk/ukccis ), ChildLine ( www.childline.org.uk )). Many schools now train pupils in e-safety and ‘netiquette’ to equip them with the critical tools that they will need to understand the complexity of the digital world and become aware of its risks as well as its benefits. Techniques include blocking bullying behaviour online or creating panic buttons for cyber victims to use when under threat. Price & Dalgleish Reference Price and Dalgleish 30 found that blocking was considered as a most helpful online action by cyber victims and a number of other studies have additionally found that deleting nasty messages and stopping use of the internet were effective strategies. Reference Livingstone, Haddon, Anke Görzig and Ólafsson 13 , Reference Kowalski and Limber 14 , Reference Juvonen and Gross 24 However, recent research by Kumazaki et al Reference Kumazaki, Kanae, Katsura, Akira and Megumi 31 found that training young people in netiquette did not significantly reduce or prevent cyberbullying. Clearly there is a need for further research to evaluate the effectiveness of different types of technological intervention.

Parents play an important role in prevention by banning websites and setting age-appropriate limits of using the computer and internet. Reference Kowalski and Limber 14 Poor parental monitoring is consistently associated with a higher risk for young people to be involved in both traditional and cyberbullying, whether as perpetrator or target. Reference Ybarra and Mitchell 15 However, adults may be less effective in dealing with cyberbullying once it has occurred. Most studies confirm that it is essential to tell someone about the cyberbullying rather than suffer in silence and many students report that they would ask their parents for help in dealing with a cyberbullying incident. Reference Smith, Mahdavi, Carvalho, Fisher, Russell and Tippett 10 , Reference Stacey 29 , Reference Aricak, Siyahhan, Uzunhasanoglu, Saribeyoglu, Ciplak and Yilmaz 32 On the other hand, some adolescents recommend not consulting adults because they fear loss of privileges (e.g. having and using mobile telephones and their own internet access), and because they fear that their parents would simply advise them to ignore the situation or that they would not be able to help them as they are not accustomed to cyberspace. Reference Smith, Mahdavi, Carvalho, Fisher, Russell and Tippett 10 , Reference Hoff and Mitchell 12 , Reference Kowalski and Limber 14 , Reference Stacey 29 In a web-based survey of 12- to 17-year-olds, of whom most had experienced at least one cyberbullying incident in the past year, Juvonen & Gross Reference Juvonen and Gross 24 found that 90% of the victims did not tell their parents about their experiences and 50% of them justified it with ‘I need to learn to deal with it myself’.

Students also have a rather negative and critical attitude to teachers’ support and a large percentage consider telling a teacher or the school principal as rather ineffective. Reference Aricak, Siyahhan, Uzunhasanoglu, Saribeyoglu, Ciplak and Yilmaz 32 , Reference DiBasilio 33 Although 17% of students reported to a teacher after a cyberbullying incident, in 70% of the cases the school did not react to it. Reference Hoff and Mitchell 12

Involving peers

Young people are more likely to find it helpful to confide in peers. Reference Livingstone, Haddon, Anke Görzig and Ólafsson 13 , Reference Price and Dalgleish 30 , Reference DiBasilio 33 Additionally, it is essential to take account of the bystanders who usually play a critical role as audience to the cyberbullying in a range of participant roles, and who have the potential to be mobilised to take action against cyberbullying. Reference Salmivalli 9 , Reference Cowie 34 For example, a system of young cyber mentors, trained to monitor websites and offer emotional support to cyber victims, was positively evaluated by adolescents. Reference Banerjee, Robinson and Smalley 35 Similarly, DiBasilio Reference DiBasilio 33 showed that peer leaders in school played a part in prevention of cyberbullying by creating bullying awareness in the school, developing leadership skills among students, establishing bullying intervention practices and team-building initiatives in the student community, and encouraging students to behave proactively as bystanders. This intervention successfully led to a decline in cyberbullying, in that the number of students who participated in electronic bullying decreased, while students’ understanding of bullying widened.

Although recommended strategies for coping with cyberbullying abound, there remains a lack of evidence about what works best and in what circumstances in counteracting its negative effects. However, it would appear that if we are to solve the problem of cyberbullying, we must also understand the networks and social groups where this type of abuse occurs, including the importance that digital worlds play in the emotional lives of young people today, and the disturbing fact that cyber victims can be targeted at any time and wherever they are, so increasing their vulnerability.

There are some implications for professionals working with children and young people. Punitive methods tend on the whole not to be effective in reducing cyberbullying. In fact, as Shariff & Strong-Wilson Reference Shariff, Strong-Wilson and Kincheloe 36 found, zero-tolerance approaches are more likely to criminalise young people and add a burden to the criminal justice system. Interventions that work with peer-group relationships and with young people’s value systems have a greater likelihood of success. Professionals also need to focus on the values that are held within their organisations, in particular with regard to tolerance, acceptance and compassion for those in distress. The ethos of the schools where children and young people spend so much of their time is critical. Engagement with school is strongly linked to the development of positive relationships with adults and peers in an environment where care, respect and support are valued and where there is an emphasis on community. As Batson et al Reference Batson, Ahmad, Lishner, Tsang, Snyder and Lopez 37 argue, empathy-based socialisation practices encourage perspective-taking and enhance prosocial behaviour, leading to more satisfying relationships and greater tolerance of stigmatised outsider groups. This is particularly relevant to the discussion since researchers have consistently found that high-quality friendship is a protective factor against mental health difficulties among bullied children. Reference Skrzypiec, Slee, Askell-Williams and Lawson 38

Finally, research indicates the importance of tackling bullying early before it escalates into something much more serious. This affirms the need for schools to establish a whole-school approach with a range of systems and interventions in place for dealing with all forms of bullying and social exclusion. External controls have their place, but we also need to remember the interpersonal nature of cyberbullying. This suggests that action against cyberbullying should be part of a much wider concern within schools about the creation of an environment where relationships are valued and where conflicts are seen to be resolved in the spirit of justice and fairness.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to the COST ACTION IS0801 for its support in preparing this article ( https://sites.google.com/site/costis0801 ).

Declaration of interest

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 37, Issue 5

- Helen Cowie (a1)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.112.040840

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

Psychological Challenges of Cyberspace: A Systematical Review of Meta-analysis

- October 2022

- Kunduz University

- The Open University of Tanzania (OUT)

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Mohammad Nabi Adalatyar

- Matiullah Salih

- Kamayani Mathur

- Mendon Suhan

- Raveendranath Nayak

- Sangam Mahesh Gull

- NEUROPSYCHOLOGIA

- Mouna Cerra Cheraka

- Max Jeanneret

- Andrea Serino

- N.A. Stepanova

- Svetlana A. Filippova

- Ryota Nishihara

- J PEDIATR PSYCHOL

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Cyberbullying: Everything You Need to Know

- Cyberbullying

- How to Respond

Cyberbullying is the act of intentionally and consistently mistreating or harassing someone through the use of electronic devices or other forms of electronic communication (like social media platforms).

Because cyberbullying mainly affects children and adolescents, many brush it off as a part of growing up. However, cyberbullying can have dire mental and emotional consequences if left unaddressed.

This article discusses cyberbullying, its adverse effects, and what can be done about it.

FangXiaNuo / Getty Images

Cyberbullying Statistics and State Laws

The rise of digital communication methods has paved the way for a new type of bullying to form, one that takes place outside of the schoolyard. Cyberbullying follows kids home, making it much more difficult to ignore or cope.

Statistics

As many as 15% of young people between 12 and 18 have been cyberbullied at some point. However, over 25% of children between 13 and 15 were cyberbullied in one year alone.

About 6.2% of people admitted that they’ve engaged in cyberbullying at some point in the last year. The age at which a person is most likely to cyberbully one of their peers is 13.

Those subject to online bullying are twice as likely to self-harm or attempt suicide . The percentage is much higher in young people who identify as LGBTQ, at 56%.

Cyberbullying by Sex and Sexual Orientation

Cyberbullying statistics differ among various groups, including:

- Girls and boys reported similar numbers when asked if they have been cyberbullied, at 23.7% and 21.9%, respectively.

- LGBTQ adolescents report cyberbullying at higher rates, at 31.7%. Up to 56% of young people who identify as LGBTQ have experienced cyberbullying.

- Transgender teens were the most likely to be cyberbullied, at a significantly high rate of 35.4%.

State Laws

The laws surrounding cyberbullying vary from state to state. However, all 50 states have developed and implemented specific policies or laws to protect children from being cyberbullied in and out of the classroom.

The laws were put into place so that students who are being cyberbullied at school can have access to support systems, and those who are being cyberbullied at home have a way to report the incidents.

Legal policies or programs developed to help stop cyberbullying include:

- Bullying prevention programs

- Cyberbullying education courses for teachers

- Procedures designed to investigate instances of cyberbullying

- Support systems for children who have been subject to cyberbullying

Are There Federal Laws Against Cyberbullying?

There are no federal laws or policies that protect people from cyberbullying. However, federal involvement may occur if the bullying overlaps with harassment. Federal law will get involved if the bullying concerns a person’s race, ethnicity, national origin, sex, disability, or religion.

Examples of Cyberbullying

There are several types of bullying that can occur online, and they all look different.

Harassment can include comments, text messages, or threatening emails designed to make the cyberbullied person feel scared, embarrassed, or ashamed of themselves.

Other forms of harassment include:

- Using group chats as a way to gang up on one person

- Making derogatory comments about a person based on their race, gender, sexual orientation, economic status, or other characteristics

- Posting mean or untrue things on social media sites, such as Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, as a way to publicly hurt the person experiencing the cyberbullying

Impersonation

A person may try to pretend to be the person they are cyberbullying to attempt to embarrass, shame, or hurt them publicly. Some examples of this include:

- Hacking into someone’s online profile and changing any part of it, whether it be a photo or their "About Me" portion, to something that is either harmful or inappropriate

- Catfishing, which is when a person creates a fake persona to trick someone into a relationship with them as a joke or for their own personal gain

- Making a fake profile using the screen name of their target to post inappropriate or rude remarks on other people’s pages

Other Examples

Not all forms of cyberbullying are the same, and cyberbullies use other tactics to ensure that their target feels as bad as possible. Some tactics include:

- Taking nude or otherwise degrading photos of a person without their consent

- Sharing or posting nude pictures with a wide audience to embarrass the person they are cyberbullying

- Sharing personal information about a person on a public website that could cause them to feel unsafe

- Physically bullying someone in school and getting someone else to record it so that it can be watched and passed around later

- Circulating rumors about a person

How to Know When a Joke Turns Into Cyberbullying

People may often try to downplay cyberbullying by saying it was just a joke. However, any incident that continues to make a person feel shame, hurt, or blatantly disrespected is not a joke and should be addressed. People who engage in cyberbullying tactics know that they’ve crossed these boundaries, from being playful to being harmful.

Effects and Consequences of Cyberbullying

Research shows many negative effects of cyberbullying, some of which can lead to severe mental health issues. Cyberbullied people are twice as likely to experience suicidal thoughts, actions, or behaviors and engage in self-harm as those who are not.

Other negative health consequences of cyberbullying are:

- Stomach pain and digestive issues

- Sleep disturbances

- Difficulties with academics

- Violent behaviors

- High levels of stress

- Inability to feel safe

- Feelings of loneliness and isolation

- Feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness

If You’ve Been Cyberbullied

Being on the receiving end of cyberbullying is hard to cope with. It can feel like you have nowhere to turn and no escape. However, some things can be done to help overcome cyberbullying experiences.

Advice for Preteens and Teenagers

The best thing you can do if you’re being cyberbullied is tell an adult you trust. It may be challenging to start the conversation because you may feel ashamed or embarrassed. However, if it is not addressed, it can get worse.

Other ways you can cope with cyberbullying include:

- Walk away : Walking away online involves ignoring the bullies, stepping back from your computer or phone, and finding something you enjoy doing to distract yourself from the bullying.

- Don’t retaliate : You may want to defend yourself at the time. But engaging with the bullies can make matters worse.

- Keep evidence : Save all copies of the cyberbullying, whether it be posts, texts, or emails, and keep them if the bullying escalates and you need to report them.

- Report : Social media sites take harassment seriously, and reporting them to site administrators may block the bully from using the site.

- Block : You can block your bully from contacting you on social media platforms and through text messages.

In some cases, therapy may be a good option to help cope with the aftermath of cyberbullying.

Advice for Parents

As a parent, watching your child experience cyberbullying can be difficult. To help in the right ways, you can:

- Offer support and comfort : Listening to your child explain what's happening can be helpful. If you've experienced bullying as a child, sharing that experience may provide some perspective on how it can be overcome and that the feelings don't last forever.

- Make sure they know they are not at fault : Whatever the bully uses to target your child can make them feel like something is wrong with them. Offer praise to your child for speaking up and reassure them that it's not their fault.

- Contact the school : Schools have policies to protect children from bullying, but to help, you have to inform school officials.

- Keep records : Ask your child for all the records of the bullying and keep a copy for yourself. This evidence will be helpful to have if the bullying escalates and further action needs to be taken.

- Try to get them help : In many cases, cyberbullying can lead to mental stress and sometimes mental health disorders. Getting your child a therapist gives them a safe place to work through their experience.

In the Workplace

Although cyberbullying more often affects children and adolescents, it can also happen to adults in the workplace. If you are dealing with cyberbullying at your workplace, you can:

- Let your bully know how what they said affected you and that you expect it to stop.

- Keep copies of any harassment that goes on in the workplace.

- Report your cyberbully to your human resources (HR) department.

- Report your cyberbully to law enforcement if you are being threatened.

- Close off all personal communication pathways with your cyberbully.

- Maintain a professional attitude at work regardless of what is being said or done.

- Seek out support through friends, family, or professional help.

Effective Action Against Cyberbullying

If cyberbullying continues, actions will have to be taken to get it to stop, such as:

- Talking to a school official : Talking to someone at school may be difficult, but once you do, you may be grateful that you have some support. Schools have policies to address cyberbullying.

- Confide in parents or trusted friends : Discuss your experience with your parents or others you trust. Having support on your side will make you feel less alone.

- Report it on social media : Social media sites have strict rules on the types of interactions and content sharing allowed. Report your aggressor to the site to get them banned and eliminate their ability to contact you.

- Block the bully : Phones, computers, and social media platforms contain options to block correspondence from others. Use these blocking tools to help free yourself from cyberbullying.

Help Is Available

If you or someone you know are having suicidal thoughts, dial 988 to contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline and connect with a trained counselor. To find mental health resources in your area, contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 800-662-4357 for information.

Cyberbullying occurs over electronic communication methods like cell phones, computers, social media, and other online platforms. While anyone can be subject to cyberbullying, it is most likely to occur between the ages of 12 and 18.

Cyberbullying can be severe and lead to serious health issues, such as new or worsened mental health disorders, sleep issues, or thoughts of suicide or self-harm. There are laws to prevent cyberbullying, so it's essential to report it when it happens. Coping strategies include stepping away from electronics, blocking bullies, and getting.

Alhajji M, Bass S, Dai T. Cyberbullying, mental health, and violence in adolescents and associations with sex and race: data from the 2015 youth risk behavior survey . Glob Pediatr Health. 2019;6:2333794X19868887. doi:10.1177/2333794X19868887

Cyberbullying Research Center. Cyberbullying in 2021 by age, gender, sexual orientation, and race .

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: StopBullying.gov. Facts about bullying .

John A, Glendenning AC, Marchant A, et al. Self-harm, suicidal behaviours, and cyberbullying in children and young people: systematic review . J Med Internet Res . 2018;20(4):e129. doi:10.2196/jmir.9044

Cyberbullying Research Center. Bullying, cyberbullying, and LGBTQ students .

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: StopBullying.gov. Laws, policies, and regulations .

Wolke D, Lee K, Guy A. Cyberbullying: a storm in a teacup? . Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(8):899-908. doi:10.1007/s00787-017-0954-6

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: StopBullying.gov. Cyberbullying tactics .

Garett R, Lord LR, Young SD. Associations between social media and cyberbullying: a review of the literature . mHealth . 2016;2:46-46. doi:10.21037/mhealth.2016.12.01

Nemours Teens Health. Cyberbullying .

Nixon CL. Current perspectives: the impact of cyberbullying on adolescent health . Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2014;5:143-58. doi:10.2147/AHMT.S36456

Nemours Kids Health. Cyberbullying (for parents) .

By Angelica Bottaro Bottaro has a Bachelor of Science in Psychology and an Advanced Diploma in Journalism. She is based in Canada.

Cyberbullying: What is it and how can you stop it?

Explore the latest psychological science about the impact of cyberbullying and what to do if you or your child is a victim

- Mental Health

- Social Media and Internet

Cyberbullying can happen anywhere with an internet connection. While traditional, in-person bullying is still more common , data from the Cyberbullying Research Center suggest about 1 in every 4 teens has experienced cyberbullying, and about 1 in 6 has been a perpetrator. About 1 in 5 tweens, or kids ages 9 to 12, has been involved in cyberbullying (PDF, 5.57MB) .

As technology advances, so do opportunities to connect with people—but unfettered access to others isn’t always a good thing, especially for youth. Research has long linked more screen time with lower psychological well-being , including higher rates of anxiety and depression. The risk of harm is higher when kids and teens are victimized by cyberbullying.

Here’s what you need to know about cyberbullying, and psychology’s role in stopping it.

What is cyberbullying?

Cyberbullying occurs when someone uses technology to demean, inflict harm, or cause pain to another person. It is “willful and repeated harm inflicted through the use of computers, cell phones, and other electronic devices.” Perpetrators bully victims in any online setting, including social media, video or computer games, discussion boards, or text messaging on mobile devices.

Virtual bullying can affect anyone, regardless of age. However, the term “cyberbullying” usually refers to online bullying among children and teenagers. It may involve name calling, threats, sharing private or embarrassing photos, or excluding others.

One bully can harass another person online or several bullies can gang up on an individual. While a stranger can incite cyberbullying, it more frequently occurs among kids or teens who know each other from school or other social settings. Research suggests bullying often happens both at school and online .

Online harassment between adults can involve different terms, depending on the relationship and context. For example, dating violence, sexual harassment, workplace harassment, and scamming—more common among adults—can all happen on the internet.

How can cyberbullying impact the mental health of myself or my child?

Any form of bullying can negatively affect the victim’s well-being, both at the time the bullying occurs and in the future. Psychological research suggests being victimized by a cyberbully increases stress and may result in anxiety and depression symptoms . Some studies find anxiety and depression increase the likelihood adolescents will become victims to cyberbullying .

Cyberbullying can also cause educational harm , affecting a student’s attendance or academic performance, especially when bullying occurs both online and in school or when a student has to face their online bully in the classroom. Kids and teens may rely on negative coping mechanisms, such as substance use, to deal with the stress of cyberbullying. In extreme cases, kids and teens may struggle with self-harm or suicidal ideation .

How can parents talk to their children about cyberbullying?

Parents play a crucial role in preventing cyberbullying and associated harms. Be aware of what your kids are doing online, whether you check your child’s device, talk to them about their online behaviors, or install a monitoring program. Set rules about who your child can friend or interact with on social media platforms. For example, tell your child if they wouldn’t invite someone to your house, then they shouldn’t give them access to their social media accounts. Parents should also familiarize themselves with signs of cyberbullying , such as increased device use, anger or anxiety after using a device, or hiding devices when others are nearby.

Communicating regularly about cyberbullying is an important component in preventing it from affecting your child’s well-being. Psychologists recommend talking to kids about how to be safe online before they have personal access to the internet. Familiarize your child with the concept of cyberbullying as soon as they can understand it. Develop a game plan to problem solve if it occurs. Cultivating open dialogue about cyberbullying can ensure kids can identify the experience and tell an adult, before it escalates into a more harmful situation.

It’s also important to teach kids what to do if someone else is being victimized. For example, encourage your child to tell a teacher or parent if someone they know is experiencing cyberbullying.

Keep in mind kids may be hesitant to open up about cyberbullying because they’re afraid they’ll lose access to their devices. Encourage your child to be open with you by reminding them they won’t get in trouble for talking to you about cyberbullying. Clearly explain your goal is to allow them to communicate with their friends safely online.

How can I report cyberbullying?

How you handle cyberbullying depends on a few factors, such as the type of bullying and your child’s age. You may choose to intervene by helping a younger child problem solve whereas teens may prefer to handle the bullying on their own with a caregiver’s support.

In general, it’s a good practice to take screenshots of the cyberbullying incidents as a record, but not to respond to bullies’ messages. Consider blocking cyberbullies to prevent future harassment.

Parents should contact the app or website directly about removing bullying-related posts, especially if they reveal private or embarrassing information. Some social media sites suspend perpetrators’ accounts.

If the bullying also occurs at school or on a school-owned device, or if the bullying is affecting a child’s school performance, it may be appropriate to speak with your child’s teacher or school personnel.

What are the legal ramifications of cyberbullying?

In some cases, parents should report cyberbullying to law enforcement. If cyberbullying includes threats to someone’s physical safety, consider contacting your local police department.

What’s illegal can vary from state to state. Any illegal behaviors, such as blackmailing someone to send money, hate crimes, stalking, or posting sexual photos of a minor, can have legal repercussions. If you’re not sure about what’s legal and what’s not, check your state’s laws and law enforcement .

Are big tech companies responsible for promoting positive digital spaces?

In an ideal world, tech companies would prioritize creating safer online environments for young people. Some companies are working toward it already, including partnering with psychologists to better understand how their products affect kids, and how to keep them safe. But going the extra mile isn’t always profitable for technology companies. For now, it’s up to individuals, families, and communities to protect kids’ and teens’ best interest online.

What does the research show about psychology’s role in reducing this issue?

Many studies show preventative measures can drastically reduce cyberbullying perpetration and victimization . Parents and caregivers, schools, and technology companies play a role in educating kids about media literacy and mental health. Psychologists—thanks to their expertise in child and teen development, communication, relationships, and mental health—can also make important contributions in preventing cyberbullying.

Because cybervictimization coincides with anxiety and depression, research suggests mental health clinicians and educators should consider interventions that both address adolescents’ online experiences and support their mental, social, and emotional well-being. Psychologists can also help parents speak to their kids about cyberbullying, along with supporting families affected by it.

You can learn more about cyberbullying at these websites:

- Cyberbullying Research Center

- StopBullying.gov

- Nemours Kids Health

Acknowledgments

APA gratefully acknowledges the following contributors to this publication:

- Sarah Domoff, PhD, associate professor of psychology at Central Michigan University

- Dorothy Espelage, PhD, William C. Friday Distinguished Professor of Education at the University of North Carolina

- Stephanie Fredrick, PhD, NCSP, assistant professor and associate director of the Dr. Jean M. Alberti Center for the Prevention of Bullying Abuse and School Violence at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York

- Brian TaeHyuk Keum, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Social Welfare at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs

- Mitchell J. Prinstein, PhD, chief science officer at APA

- Susan Swearer, PhD, Willa Cather Professor of School Psychology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln; licensed psychologist

Recommended Reading

You may also like

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Cybervictimization and cyberbullying among college students: The chain mediating effects of stress and rumination

1 Department of Psychology, School of Public Policy and Administration, Nanchang University, Nanchang, China

2 Department of Psychology, College of Education and Science, Hubei Normal University, Huangshi, China

3 School of Marxism, Wuhan Business University, Wuhan, China

Associated Data

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The popularity of the Internet has led to an increase in cybervictimization and cyberbullying. Many studies have focused on the factors influencing cybervictimization or cyberbullying, but few have researched the mechanism that mediates these phenomena. Therefore, in this study, we use a chain mediation model to explore the mechanisms of cybervictimization and cyberbullying. This research is based on the general aggression model and examines whether stress and rumination play a mediating role in the relationship between cybervictimization and cyberbullying among Chinese college students. This study included 1,299 Chinese college students (597 men and 702 women, M = 21.24 years, SD = 3.16) who completed questionnaires on cybervictimization, stress, rumination, and cyberbullying. Harman’s one-factor test was used to analyze common method bias; mean and standard deviations were used to analyze the descriptive statistics, Pearson’s moment correlation was used to determine the relationship between variables, and Model 6 of the SPSS macro examined the mediating effect of stress and rumination. The results indicate that rumination mediated the relationship between cybervictimization and cyberbullying. In addition, stress and rumination acted as a chain mediator in this association. These results have the potential to reduce the likelihood of college students engaging in cyberbullying as a result of cybervictimization, minimize the rate of cyberbullying among youths, and lead to the development of interventions for cybervictimization and cyberbullying.

1. Introduction

The Internet plays an important role in people’s lives; however, there are risks associated with using the Internet, such as cybervictimization and cyberbullying ( Ferrara et al., 2018 ). It is obvious that the proliferation of the internet has resulted to an increased cases of cybervictimization and cyberbullying, which have become prevalent in society ( Ding et al., 2020 ). Studies from the United States, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Turkey have demonstrated a strong correlation between increased Internet use and increased cybervictimization and cyberbullying ( Hinduja and Patchin, 2008 ; Smith et al., 2008 ; Sticca et al., 2013 ). Cybervictimization and cyberbullying have become a major concern for college students ( Khine et al., 2020 ; Martínez-Monteagudo et al., 2020 ; Qudah et al., 2020 ), and several recent studies have investigated cyberbullying behavior among college students ( Alrajeh et al., 2021 ; Lam et al., 2022 ).

Cyber-victims are those affected by cyberbullying ( Betts, 2015 ), and cybervictimization usually occurs through electronic media ( Tokunaga, 2010 ). Cybervictimization is widespread, with a large and serious scope of abuse ( Dempsey et al., 2009 ). Ansary (2020) analyzed numerous studies and found that the average annual cybervictimization rate was 14–21%. Globally, 10 to 72% of youths have reported being victims of cyberbullying ( Tokunaga, 2010 ; Mishna et al., 2011 ). Most adolescents who are bullied online experience mental health problems, including stress and maladaptive regulation strategies ( Tokunaga, 2010 ; Albdour et al., 2017 ; Palermiti et al., 2017 ; Musharraf et al., 2019 ), some have even committed suicide ( Quintana-Orts et al., 2022 ). Cyber-victims experience bullying multiple times and are more likely to be involved in cyberbullying ( Zhu et al., 2019 ; Dong, 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020 ). Faucher et al. (2014) found that of the 24.1% of Canadian university students who experienced cyberbullying, 5.1% engaged in cyberbullying.

Cybervictimization is more likely to lead to cyberbullying, thus creating a vicious cycle ( Sun et al., 2020 ). Many studies have found a strong correlation between cybervictimization and cyberbullying ( Leung et al., 2018 ; Lozano-Blasco et al., 2020 ). A meta-analysis based on cyberbullying found a significantly positive correlation between cybervictimization and cyberbullying ( Kowalski et al., 2014 ). Moreover, cybervictimization has been identified as a strong predictor of cyberbullying ( Kwan and Skoric, 2013 ; Kowalski et al., 2014 ). Cyber-victims are at high risk of becoming cyberbullies ( Walrave and Heirman, 2011 ; Hemphill et al., 2012 ). Some cyber-victims might respond to cyberbullying with cyberbullying behavior ( Yilmaz, 2011 ). Cybervictimization is the strongest predictor of cyberbullying ( Akbulut and Eristi, 2011 ). Dehue et al. (2008) found that 5.7% of cyberbullied adolescents chose a retaliatory coping strategy, such as cyberbullying. Cyber-victims often commit cyberbullying in the same online environment where they experience bullying ( Gradinger et al., 2010 ). A longitudinal study of teenagers from four Midwestern U.S. middle schools found that teens who had been bullied online demonstrated aggressive behavior (e.g., cyber relational or verbal aggression) 6 months later ( Wright and Yan, 2013 ). Chu et al. (2018) found that previous cybervictimization experiences positively predicted subsequent cyberbullying behavior, and Espelage et al. (2012) argued that cyber-victims would perpetrate cyberbullying.

Cyberbullying is an intentional act repeatedly committed against an individual or a group by an individual or group using electronic information communication tools ( Smith et al., 2008 ; Menesini et al., 2012 ; Jadambaa et al., 2019 ). The incidence of cyberbullying is increasing with the continuous development of Internet technology ( Yıldız Durak, 2019 ). Cyberbullying is a serious global social problem that affects individuals who access the Internet or mobile networks regardless of age, education, and socioeconomic problems ( Akbulut and Eristi, 2011 ; Garaigordobil and Martínez-Valderrey, 2015 ; Festl, 2016 ). Cyberbullying is common among college students with an incidence rate of 10–50% ( Kowalski et al., 2012 ; Kokkinos et al., 2014 ). Compared to individuals at other ages, college students are more likely to engage in cyberbullying because they can use the Internet for long periods of time and unsupervised, as well as frequently showcase their lives on social media, seek experiences, and form social cliques ( Jones and Scott, 2012 ). A study of Turkish university students demonstrated that 59.8% of undergraduates engaged in cyberbullying ( Turan et al., 2011 ). A meta-analysis study on bullying prevalence across contexts revealed that the average incidence of cyberbullying was about 15%; however, the study included traditional bullying, and the study only focused on peer cyberbullying ( Modecki et al., 2014 ). According to UNICEF study, 19.7% college students reported participating in cyberbullying at least once in their lifetime, and 54.4% reported experiencing cyberbullying at least once in their lifetime ( Ozden and Icellioglu, 2014 ).

The general aggression model is considered a valuable theoretical framework for explaining cyberbullying among college students ( Wong et al., 2018 ). The model ( Bushman and Anderson, 2002 ) provides a comprehensive theoretical framework that includes both individual-specific and situation-specific factors that can be effectively used to explain cybervictimization and cyberbullying. The general aggression model suggests that the occurrence of aggression includes three processes: an individual and situational input variable process, a path process, and an output variable process. According to the generalized aggression model, the cyberbullying experience is an individual and situational input variable process that changes the individual’s state and drives aggressive behavior. Cybervictimization acts as a trigger for individuals to instigate cyberbullying behaviors ( Wong et al., 2018 ). Lang (1968) proposed that aversive events awaken an individual’s hostile attitude and eventually provoke the impulse to engage in aggressive behavior. The impulses triggered by aversive events are also the strongest situational triggers ( Finkel and Eckhardt, 2013 ).

Most extant studies have focused on the relationship between traditional bullying and cyberbullying ( Tomazin and Smith, 2007 ; Bhat, 2008 ; Doneman, 2008 ) and the influencing factors of cybervictimization and cyberbullying such as gender, emotional problems, depression, anxiety, and other physical and psychosomatic problems ( Desmet et al., 2014 ; Gimenez Gualdo et al., 2015 ; Yildirim et al., 2019 ). However, the mechanisms underlying the mediating or moderating factors between cybervictimization and cyberbullying remain unclear. The general aggression model explains the occurrence of cyberbullying from both person-specific and situation-specific factors. Therefore, this study applies this theory to analyze the mechanism of the association between cybervictimization and cyberbullying.

1.1. The role of stress as a mediator between cybervictimization and cyberbullying

According to the general aggression model, stress is a pathway process that affects an individual’s current cognitive and affective states, which in turn stimulate the individual’s physiological state. Stress is a cacoethic state that has harmful effects on the mind and body ( Weiten et al., 2014 ). Stress is also an important correlate of aggressive tendencies in college students ( Velezmoro et al., 2010 ). Within the social information processing framework, research has primarily investigated the mechanisms that link this stressor to simultaneous and future aggressive behaviors ( Dodge, 1993 ). The experience of being cyberbullied can lead to stress ( Monks et al., 2012 ). Cyber-victims have reported symptoms of stress ( Williams et al., 2017 ). Snyman and Loh (2015) demonstrated that cyber-victims might experience stress, while Martínez-Monteagudo et al. (2020) showed that cyber-victims could exhibit high levels of stress. González-Cabrera et al. (2017) measured stress perceptions based on cortisol and found that cybervictimization events induce stress. Many studies have found a positive correlation between cybervictimization and stress ( Martins et al., 2016 ), including an association with high levels of social stress ( Fredstrom et al., 2011 ), and a meta-analysis study indicated that stress is very highly correlated with cybervictimization ( Kowalski et al., 2014 ). Peer victimization is a significant stressor for adolescents, and victimized adolescents are more likely to develop aggressive behaviors than adolescents who are not victimized ( Prinstein et al., 2005 ). Patchin and Hinduja (2011) argued that as a response to stressful life events, some young people may engage in bullying behaviors (both traditional and online). In addition, Lianos and Mcgrath (2018) revealed that cybervictimization, as a negative stimulus, was an important stressor that led to cyberbullying and that adolescents were more likely to exhibit cyberbullying behaviors after experiencing stressful events. Garaigordobil and Machimbarrena (2019) confirmed positive correlations among cybervictimization, cyberbullying, and stress. The experience of cybervictimization will affect cyber victims’ responses to stress, and they might become involved in cyberbullying ( Kowalski et al., 2014 ).

1.2. The mediating role of rumination between cybervictimization and cyberbullying

According to the general aggression model, rumination is another pathway process, and rumination affects an individual’s current cognitive and affective states, which in turn stimulate the individual’s physiological state. Rumination is considered an emotion regulation strategy in which individuals repetitively focus on the reasons, consequences, and meanings of negative emotions ( Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991 ). A victimization environment may influence an individual’s sense of self so that they attribute the bullying to their own personality or behavior, thus engaging in self-blame, a form of rumination ( Graham and Juvonen, 2001 ). Victimization is related to self-blaming attributions ( Taylor et al., 2013 ); after being bullied, individuals will attribute the cause to themselves, which leads to rumination. Cybervictimization has been found to be positively correlated with rumination ( Feinstein et al., 2014 ; Rey et al., 2020 ). Zhong et al. (2015) demonstrated that cybervictimization was perceived as a negative life event, leading many junior high school students to wonder why they were always bullied; moreover, they showed that it positively predicted rumination.

Negative thinking can cause negative behaviors, and high levels of rumination can induce aggressive behavior ( Zhu, 2014 ; Zhong et al., 2015 ). According to Feinstein et al. (2014) , the tendency to ruminate was elevated after exposure to online violence. Rumination can significantly and accurately predict a variety of aggressive behaviors ( Peters et al., 2015 ), and cyberbullying is a sub-category of aggressive behavior ( Smith et al., 2008 ).