The Future of Man

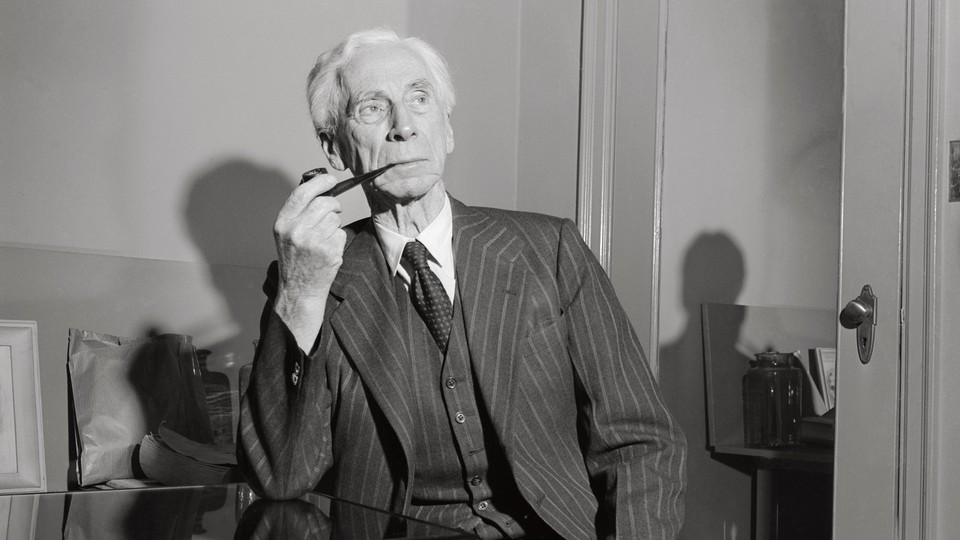

Bertrand Russell calmly examines three foreseeable possibilities for the human race.

B efore the end of the present century, unless something quite unforeseeable occurs, one of three possibilities will have been realized. These three are: —

1. The end of human life, perhaps of all life on our planet.

2. A reversion to barbarism after a catastrophic diminution of the population of the globe.

3. A unification of the world under a single government, possessing a monopoly of all the major weapons of war.

I do not pretend to know which of these will happen, or even which is the most likely. What I do contend is that the kind of system to which we have been accustomed cannot possibly continue.

The first possibility, the extinction of the human race, is not to be expected in the next world war, unless that war is postponed for a longer time than now seems probable. But if the next world war is indecisive, or if the victors are unwise, and if organized states survive it, a period of feverish technical development may be expected to follow its conclusion. With vastly more powerful means of utilizing atomic energy than those now available, it is thought by many sober men of science that radioactive clouds, drifting round the world, may disintegrate living tissue everywhere. Although the last survivor may proclaim himself universal Emperor, his reign will be brief and his subjects will all be corpses. With his death the uneasy episode of life will end, and the peaceful rocks will revolve unchanged until the sun explodes.

Perhaps a disinterested spectator would consider this the most desirable consummation, in view of man’s long record of folly and cruelty. But we who are actors in the drama, who are entangled in the net of private affections and public hopes, can hardly take this attitude with any sincerity. True, I have heard men say that they would prefer the end of man to submission to the Soviet government, and doubtless in Russia there are those who would say the same about submission to Western capitalism. But this is rhetoric with a bogus air of heroism. Although it must be regarded as unimaginative humbug, it is dangerous, because it makes men less energetic in seeking ways of avoiding the catastrophe that they pretend not to dread.

The second possibility, that of a reversion to barbarism, would leave open the likelihood of a gradual return to civilization, as after the fall of Rome. The sudden transition will, if it occurs, be infinitely painful to those who experience it, and for some centuries afterwards life will be hard and drab. But at any rate there will still be a future for mankind, and the possibility of rational hope.

I think such an outcome of a really scientific world war is by no means improbable. Imagine each side in a position to destroy the chief cities and centers of industry of the enemy; imagine an almost complete obliteration of laboratories and libraries, accompanied by a heavy casualty rate among men of science; imagine famine due to radioactive spray, and pestilence caused by bacteriological warfare: Would social cohesion survive such strains? Would not prophets tell the maddened populations that their ills were wholly due to science, and that the extermination of all educated men would bring the millennium? Extreme hopes are born of extreme misery, and in such a world hopes could only be irrational. I think the great states to which we are accustomed would break up, and the sparse survivors would revert to a primitive village economy.

The third possibility, that of the establishment of a single government for the whole world, might be realized in various ways: by the victory of the United States in the next world war, or by the victory of the U.S.S.R., or, theoretically, by agreement. Or—and I think this is the most hopeful of the issues that are in any degree probable—by an alliance of the nations that desire an international government, becoming, in the end, so strong that Russia would no longer dare to stand out. This might conceivably be achieved without another world war, but it would require courageous and imaginative statesmanship in a number of countries.

There are various arguments that are used against the project of a single government of the whole world. The commonest is that the project is utopian and impossible. Those who use this argument, like most of those who advocate a world government, are thinking of a world government brought about by agreement. I think it is plain that the mutual suspicions between Russia and the West make it futile to hope, in any near future, for any genuine agreement. Any pretended universal authority to which both sides can agree, as things stand, is bound to be a sham, like UN. Consider the difficulties that have been encountered in the much more modest project of an international control over atomic energy, to which Russia will consent only if inspection is subject to the veto, and therefore a farce. I think we should admit that a world government will have to be imposed by force.

But—many people will say—why all this talk about a world government? Wars have occurred ever since men were organized into units larger than the family, but the human race has survived. Why should it not continue to survive even if wars go on occurring from time to time? Moreover, people like war, and will feel frustrated without it. And without war there will be no adequate opportunity for heroism or self-sacrifice.

This point of view—which is that of innumerable elderly gentlemen, including the rulers of Soviet Russia—fails to take account of modern technical possibilities. I think civilization could probably survive one more world war, provided it occurs fairly soon and does not last long. But if there is no slowing up in the rate of discovery and invention, and if great wars continue to recur, the destruction to be expected, even if it fails to exterminate the human race, is pretty certain to produce the kind of reversion to a primitive social system that I spoke of a moment ago. And this will entail such an enormous diminution of population, not only by war, but by subsequent starvation and disease, that the survivors are bound to be fierce and, at least for a considerable time, destitute of the qualities required for rebuilding civilization.

Nor is it reasonable to hope that, if nothing drastic is done, wars will nevertheless not occur. They always have occurred from time to time, and obviously will break out again sooner or later unless mankind adopts some system that makes them impossible. But the only such system is a single government with a monopoly of armed force.

If things are allowed to drift, it is obvious that the bickering between Russia and the Western democracies will continue until Russia has a considerable store of atomic bombs, and that when that time comes there will be an atomic war. In such a war, even if the worst consequences are avoided, Western Europe, including Great Britain, will be virtually exterminated. If America and the U.S.S.R. survive as organized states, they will presently fight again. If one side is victorious, it will rule the world, and a unitary government of mankind will have come into existence; if not, either mankind or, at least, civilization will perish. This is what must happen if nations and their rulers are lacking in constructive vision.

When I speak of “constructive vision,” I do not mean merely the theoretical realization that a world government is desirable. More than half the American nation, according to the Gallup poll, holds this opinion. But most of its advocates think of it as something to be established by friendly negotiation, and shrink from any suggestion of the use of force. In this I think they are mistaken. I am sure that force, or the threat of force, will be necessary. I hope the threat of force may suffice, but, if not, actual force should be employed.

Assuming a monopoly of armed force established by the victory of one side in a war between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., what sort of world will result?

In either case, it will be a world in which successful rebellion will be impossible. Although, of course, sporadic assassination will still be liable to occur, the concentration of all important weapons in the hands of the victors will make them irresistible, and there will therefore be secure peace. Even if the dominant nation is completely devoid of altruism, its leading inhabitants, at least, will achieve a very high level of material comfort, and will be freed from the tyranny of fear. They are likely, therefore, to become gradually more good-natured and less inclined to persecute. Like the Romans, they will, in the course of time, extend citizenship to the vanquished. There will then be a true world state, and it will be possible to forget that it will have owed its origin to conquest. Which of us, during the reign of Lloyd George, felt humiliated by the contrast with the days of Edward I?

A world empire of either the U.S. or the U.S.S.R. is therefore preferable to the results of a continuation of the present international anarchy.

T here are, however, important reasons for preferring a victory of America. I am not contending that capitalism is better than communism; I think it not impossible that, if America were communist and Russia were capitalist, I should still be on the side of America. My reason for siding with America is that there is in that country more respect than in Russia for the things that I value in a civilized way of life. The things I have in mind are such as: freedom of thought, freedom of inquiry, freedom of discussion, and humane feeling. What a victory of Russia would mean is easily to be seen in Poland. There were flourishing universities in Poland, containing men of great intellectual eminence. Some of these men, fortunately, escaped; the rest disappeared. Education is now reduced to learning the formulae of Stalinist orthodoxy; it is only open (beyond the elementary stage) to young people whose parents are politically irreproachable, and it does not aim at producing any mental faculty except that of glib repetition of correct shibboleths and quick apprehension of the side that is winning official favor. From such an educational system nothing of intellectual value can result.

Meanwhile the middle class was annihilated by mass deportations, first in 1940, and again after the expulsion of the Germans. Politicians of majority parties were liquidated, imprisoned, or compelled to fly. Betraying friends to the police, or perjury when they are brought to trial, is often the only means of survival for those who have incurred governmental suspicions.

I do not doubt that, if this regime continues for a generation, it will succeed in its objects. Polish hostility to Russia will die out and be replaced by communist orthodoxy. Science and philosophy, art and literature, will become sycophantic adjuncts of government, jejune, narrow, and stupid. No individual will think, or even feel, for himself, but each will be contentedly a mere unit in the mass. A victory of Russia would, in time, make such a mentality world-wide. No doubt the complacency induced by success would ultimately lead to a relaxation of control, but the process would be slow and the revival of respect for the individual would be doubtful. For such reasons I should view a Russian victory as an appalling disaster.

A victory by the United States would have far less drastic consequences. In the first place, it would not be a victory of the United States in isolation, but of an alliance in which the other members would be able to insist upon retaining a large part of their traditional independence. One can hardly imagine the American army seizing the dons at Oxford and Cambridge and sending them to hard labor in Alaska. Nor do I think that they would accuse Mr. Attlee of plotting and compel him to fly to Moscow. Yet these are strict analogues of the things the Russians have done in Poland. After a victory of an alliance led by the United States there would still be British culture, French culture, Italian culture, and (I hope) German culture; there would not, therefore, be the same dead uniformity as would result from Soviet domination.

There is another important difference, and that is that Moscow’s orthodoxy is much more pervasive than that of Washington. In America, if you are a geneticist, you may hold whatever view of Mendelism the evidence makes you regard as the most probable; in Russia, if you are a geneticist who disagrees with Lysenko, you are liable to disappear mysteriously. In America, you may write a book debunking Lincoln if you feel so disposed; in Russia, if you should write a book debunking Lenin, it would not be published and you would be liquidated. If you are an American economist, you may hold, or not hold, that America is heading for a slump; in Russia, no economist dare question that an American slump is imminent. In America, if you are a professor of philosophy, you may be an idealist, a materialist, a pragmatist, a logical positivist, or whatever else may take your fancy; at congresses you can argue with men whose opinions differ from yours, and listeners can form a judgment as to who has the best of it. In Russia, you must be a dialectical materialist, but at one time the element of materialism outweighs the element of dialectic, and at other times it is the other way round. If you fail to follow the developments of official metaphysics with sufficient nimbleness, it will be the worse for you. Stalin at all times knows the truth about metaphysics, but you must not suppose that the truth this year is the same as it was last year. In such a world, intellect must stagnate, and even technological progress must soon come to an end.

Liberty, of the sort that communists despise, is important not only to intellectuals or to the more fortunate sections of society. Owing to its absence in Russia, the Soviet government has been able to establish a greater degree of economic inequality than exists in Great Britain or even in America. An oligarchy which controls all the means of publicity can perpetrate injustices and cruelties which would be scarcely possible if they were widely known. Only democracy and free publicity can prevent the holders of power from establishing a servile state, with luxury for the few and overworked poverty for the many. This is what is being done by the Soviet government wherever it is in secure control. There are, of course, economic inequalities everywhere, but in a democratic regime they tend to diminish, whereas under an oligarchy they tend to increase. And wherever an oligarchy has power, economic inequalities threaten to become permanent owing to the modern impossibility of successful rebellion.

I come now to the question, What should be our policy, in view of the various dangers to which mankind is exposed? To summarize the above arguments: we have to guard against three dangers—the extinction of the human race, a reversion to barbarism, and the establishment of a universal slave state involving misery for the vast majority and the disappearance of all progress in knowledge and thought. Either the first or second of these disasters is almost certain unless great wars can soon be brought to an end. Great wars can be brought to an end only by the concentration of armed force under a single authority. Such a concentration cannot be brought about by agreement, because of the opposition of Soviet Russia, but it must be brought about somehow.

The first step—and it is one which is now not very difficult—is to persuade the United States and the British Commonwealth of the absolute necessity for a military unification of the world. The governments of the English-speaking nations should then offer to all other nations the option of entering into a firm alliance, involving a pooling of military resources and mutual defense against aggression. In the case of hesitant nations, such as Italy, great inducements, economic and military, should be held out to produce their cooperation.

At a certain stage, when the alliance had acquired sufficient strength, any great power still refusing to join should be threatened with outlawry and, if recalcitrant, should be regarded as a public enemy. The resulting war, if it occurred fairly soon, would probably leave the economic and political structure of the United States intact, and would enable the victorious alliance to establish a monopoly of armed force, and therefore to make peace secure. But perhaps, if the alliance were sufficiently powerful, war would not be necessary, and the reluctant powers would prefer to enter it as equals rather than, after a terrible war, submit to it as vanquished enemies. If this were to happen, the world might emerge from its present dangers without another great war. I do not see any hope of such a happy issue by any other method. But whether Russia would yield when threatened with war is a question as to which I do not venture an opinion.

I have been dealing mainly with the gloomy aspects of the present situation of mankind. It is necessary to do so, in order to persuade the world to adopt measures running counter to traditional habits of thought and ingrained prejudices. But beyond the difficulties and probable tragedies of the near future there is the possibility of immeasurable good, and of greater well-being than has ever before fallen to the lot of man. This is not merely a possibility, but, if the Western democracies are firm and prompt, a probability. From the breakup of the Roman Empire to the present day, states have almost continuously increased in size. There are now only two fully independent states, America and Russia. The next step in this long historical process should reduce the two to one, and thus put an end to the period of organized wars, which began in Egypt some six thousand years ago. If war can be prevented without the establishment of a grinding tyranny, a weight will be lifted from the human spirit, deep collective fears will be exorcised, and as fear diminishes we may hope that cruelty also will grow less.

The uses to which men have put their increased control over natural forces are curious. In the nineteenth century they devoted themselves chiefly to increasing the numbers of Homo sapiens, particularly of the white variety. In the twentieth century they have, so far, pursued the exactly opposite aim. Owing to the increased productivity of labor, it has become possible to devote a larger percentage of the population to war. If atomic energy were to make production easier, the only effect, as things are, would be to make wars worse, since fewer people would be needed for producing necessaries. Unless we can cope with the problem of abolishing war, there is no reason whatever to rejoice in laborsaving technique, but quite the reverse. On the other hand, if the danger of war were removed, scientific technique could at last be used to promote human happiness. There is no longer any technical reason for the persistence of poverty, even in such densely populated countries as India and China. If war no longer occupied men’s thoughts and energies, we could, within a generation, put an end to all serious poverty throughout the world.

I have spoken of liberty as a good, but it is not an absolute good. We all recognize the need to restrain murderers, and it is even more important to restrain murderous states. Liberty must be limited by law, and its most valuable forms can only exist within a framework of law. What the world most needs is effective laws to control international relations. The first and most difficult step in the creation of such law is the establishment of adequate sanctions, and this is possible only through the creation of a single armed force in control of the whole world. But such an armed force, like a municipal police force, is not an end in itself; it is a means to the growth of a social system governed by law, where force is not the prerogative of private individuals or nations, but is exercised only by a neutral authority in accordance with rules laid down in advance. There is hope that law, rather than private force, may come to govern the relations of nations within the present century. If this hope is not realized we face utter disaster; if it is realized, the world will be far better than at any previous period in the history of man.

- The Big Story

- Newsletters

- Steven Levy's Plaintext Column

- WIRED Classics from the Archive

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Yuval Noah Harari on what the year 2050 has in store for humankind

Forget programming - the best skill to teach children is reinvention. In this exclusive extract from his new book, the author of Sapiens reveals what 2050 has in store for humankind.

Part one: Change is the only constant

Humankind is facing unprecedented revolutions, all our old stories are crumbling and no new story has so far emerged to replace them. How can we prepare ourselves and our children for a world of such unprecedented transformations and radical uncertainties? A baby born today will be thirty-something in 2050. If all goes well, that baby will still be around in 2100, and might even be an active citizen of the 22nd century. What should we teach that baby that will help him or her survive and flourish in the world of 2050 or of the 22nd century? What kind of skills will he or she need in order to get a job, understand what is happening around them and navigate the maze of life?

Unfortunately, since nobody knows how the world will look in 2050 – not to mention 2100 – we don’t know the answer to these questions. Of course, humans have never been able to predict the future with accuracy. But today it is more difficult than ever before, because once technology enables us to engineer bodies, brains and minds, we can no longer be certain about anything – including things that previously seemed fixed and eternal.

A thousand years ago, in 1018, there were many things people didn’t know about the future, but they were nevertheless convinced that the basic features of human society were not going to change. If you lived in China in 1018, you knew that by 1050 the Song Empire might collapse, the Khitans might invade from the north, and plagues might kill millions. However, it was clear to you that even in 1050 most people would still work as farmers and weavers, rulers would still rely on humans to staff their armies and bureaucracies, men would still dominate women, life expectancy would still be about 40, and the human body would be exactly the same. Hence in 1018, poor Chinese parents taught their children how to plant rice or weave silk, and wealthier parents taught their boys how to read the Confucian classics, write calligraphy or fight on horseback – and taught their girls to be modest and obedient housewives. It was obvious these skills would still be needed in 1050.

In contrast, today we have no idea how China or the rest of the world will look in 2050. We don’t know what people will do for a living, we don’t know how armies or bureaucracies will function, and we don’t know what gender relations will be like. Some people will probably live much longer than today, and the human body itself might undergo an unprecedented revolution thanks to bioengineering and direct brain-computer interfaces. Much of what kids learn today will likely be irrelevant by 2050.

At present, too many schools focus on cramming information. In the past this made sense, because information was scarce, and even the slow trickle of existing information was repeatedly blocked by censorship. If you lived, say, in a small provincial town in Mexico in 1800, it was difficult for you to know much about the wider world. There was no radio, television, daily newspapers or public libraries. Even if you were literate and had access to a private library, there was not much to read other than novels and religious tracts. The Spanish Empire heavily censored all texts printed locally, and allowed only a dribble of vetted publications to be imported from outside. Much the same was true if you lived in some provincial town in Russia, India, Turkey or China. When modern schools came along, teaching every child to read and write and imparting the basic facts of geography, history and biology, they represented an immense improvement.

In contrast, in the 21st century we are flooded by enormous amounts of information, and even the censors don’t try to block it. Instead, they are busy spreading misinformation or distracting us with irrelevancies. If you live in some provincial Mexican town and you have a smartphone, you can spend many lifetimes just reading Wikipedia, watching TED talks, and taking free online courses. No government can hope to conceal all the information it doesn’t like. On the other hand, it is alarmingly easy to inundate the public with conflicting reports and red herrings. People all over the world are but a click away from the latest accounts of the bombardment of Aleppo or of melting ice caps in the Arctic, but there are so many contradictory accounts that it is hard to know what to believe. Besides, countless other things are just a click away, making it difficult to focus, and when politics or science look too complicated it is tempting to switch to funny cat videos, celebrity gossip or porn.

In such a world, the last thing a teacher needs to give her pupils is more information. They already have far too much of it. Instead, people need the ability to make sense of information, to tell the difference between what is important and what is unimportant, and above all to combine many bits of information into a broad picture of the world.

In truth, this has been the ideal of western liberal education for centuries, but up till now even many western schools have been rather slack in fulfilling it. Teachers allowed themselves to focus on shoving data while encouraging pupils “to think for themselves”. Due to their fear of authoritarianism, liberal schools had a particular horror of grand narratives. They assumed that as long as we give students lots of data and a modicum of freedom, the students will create their own picture of the world, and even if this generation fails to synthesise all the data into a coherent and meaningful story of the world, there will be plenty of time to construct a good synthesis in the future. We have now run out of time. The decisions we will take in the next few decades will shape the future of life itself, and we can take these decisions based only on our present world view. If this generation lacks a comprehensive view of the cosmos, the future of life will be decided at random.

Part two: The heat is on

Besides information, most schools also focus too much on providing pupils with a set of predetermined skills such as solving differential equations, writing computer code in C++, identifying chemicals in a test tube or conversing in Chinese. Yet since we have no idea how the world and the job market will look in 2050, we don’t really know what particular skills people will need. We might invest a lot of effort teaching kids how to write in C++ or how to speak Chinese, only to discover that by 2050 AI can code software far better than humans, and a new Google Translate app enables you to conduct a conversation in almost flawless Mandarin, Cantonese or Hakka, even though you only know how to say “Ni hao”.

So what should we be teaching? Many pedagogical experts argue that schools should switch to teaching “the four Cs” – critical thinking, communication, collaboration and creativity. More broadly, schools should downplay technical skills and emphasise general-purpose life skills. Most important of all will be the ability to deal with change, to learn new things and to preserve your mental balance in unfamiliar situations. In order to keep up with the world of 2050, you will need not merely to invent new ideas and products – you will above all need to reinvent yourself again and again.

For as the pace of change increases, not just the economy, but the very meaning of “being human” is likely to mutate. In 1848, the Communist Manifesto declared that “all that is solid melts into air”. Marx and Engels, however, were thinking mainly about social and economic structures. By 2048, physical and cognitive structures will also melt into air, or into a cloud of data bits.

In 1848, millions of people were losing their jobs on village farms, and were going to the big cities to work in factories. But upon reaching the big city, they were unlikely to change their gender or to add a sixth sense. And if they found a job in some textile factory, they could expect to remain in that profession for the rest of their working lives.

By 2048, people might have to cope with migrations to cyberspace, with fluid gender identities, and with new sensory experiences generated by computer implants. If they find both work and meaning in designing up-to-the-minute fashions for a 3D virtual-reality game, within a decade not just this particular profession, but all jobs demanding this level of artistic creation might be taken over by AI. So at 25, you introduce yourself on a dating site as “a twenty-five-year-old heterosexual woman who lives in London and works in a fashion shop.” At 35, you say you are “a gender-non-specific person undergoing age- adjustment, whose neocortical activity takes place mainly in the NewCosmos virtual world, and whose life mission is to go where no fashion designer has gone before”. At 45, both dating and self-definitions are so passé. You just wait for an algorithm to find (or create) the perfect match for you. As for drawing meaning from the art of fashion design, you are so irrevocably outclassed by the algorithms, that looking at your crowning achievements from the previous decade fills you with embarrassment rather than pride. And at 45, you still have many decades of radical change ahead of you.

Please don’t take this scenario literally. Nobody can really predict the specific changes we will witness. Any particular scenario is likely to be far from the truth. If somebody describes to you the world of the mid-21st century and it sounds like science fiction, it is probably false. But then if somebody describes to you the world of the mid 21st-century and it doesn’t sound like science fiction – it is certainly false. We cannot be sure of the specifics, but change itself is the only certainty.

Such profound change may well transform the basic structure of life, making discontinuity its most salient feature. From time immemorial, life was divided into two complementary parts: a period of learning followed by a period of working. In the first part of life you accumulated information, developed skills, constructed a world view, and built a stable identity. Even if at 15 you spent most of your day working in the family’s rice field (rather than in a formal school), the most important thing you were doing was learning: how to cultivate rice, how to conduct negotiations with the greedy rice merchants from the big city and how to resolve conflicts over land and water with the other villagers. In the second part of life you relied on your accumulated skills to navigate the world, earn a living, and contribute to society. Of course, even at 50 you continued to learn new things about rice, about merchants and about conflicts, but these were just small tweaks to well-honed abilities.

By the middle of the 21st century, accelerating change plus longer lifespans will make this traditional model obsolete. Life will come apart at the seams, and there will be less and less continuity between different periods of life. “Who am I?” will be a more urgent and complicated question than ever before.

This is likely to involve immense levels of stress. For change is almost always stressful, and after a certain age most people just don’t like to change. When you are 15, your entire life is change. Your body is growing, your mind is developing, your relationships are deepening. Everything is in flux, and everything is new. You are busy inventing yourself. Most teenagers find it frightening, but at the same time, also exciting. New vistas are opening before you, and you have an entire world to conquer. By the time you are 50, you don’t want change, and most people have given up on conquering the world. Been there, done that, got the T-shirt. You much prefer stability. You have invested so much in your skills, your career, your identity and your world view that you don’t want to start all over again. The harder you’ve worked on building something, the more difficult it is to let go of it and make room for something new. You might still cherish new experiences and minor adjustments, but most people in their fifties aren’t ready to overhaul the deep structures of their identity and personality.

There are neurological reasons for this. Though the adult brain is more flexible and volatile than was once thought, it is still less malleable than the teenage brain. Reconnecting neurons and rewiring synapses is damned hard work. But in the 21st century, you can hardly afford stability. If you try to hold on to some stable identity, job or world view, you risk being left behind as the world flies by you with a whooooosh. Given that life expectancy is likely to increase, you might subsequently have to spend many decades as a clueless fossil. To stay relevant – not just economically, but above all socially – you will need the ability to constantly learn and to reinvent yourself, certainly at a young age like 50.

As strangeness becomes the new normal, your past experiences, as well as the past experiences of the whole of humanity, will become less reliable guides. Humans as individuals and humankind as a whole will increasingly have to deal with things nobody ever encountered before, such as super-intelligent machines, engineered bodies, algorithms that can manipulate your emotions with uncanny precision, rapid man-made climate cataclysms, and the need to change your profession every decade. What is the right thing to do when confronting a completely unprecedented situation? How should you act when you are flooded by enormous amounts of information and there is absolutely no way you can absorb and analyse it all? How to live in a world where profound uncertainty is not a bug, but a feature?

To survive and flourish in such a world, you will need a lot of mental flexibility and great reserves of emotional balance. You will have to repeatedly let go of some of what you know best, and feel at home with the unknown. Unfortunately, teaching kids to embrace the unknown and to keep their mental balance is far more difficult than teaching them an equation in physics or the causes of the first world war. You cannot learn resilience by reading a book or listening to a lecture. The teachers themselves usually lack the mental flexibility that the 21st century demands, for they themselves are the product of the old educational system.

The Industrial Revolution has bequeathed us the production-line theory of education. In the middle of town there is a large concrete building divided into many identical rooms, each room equipped with rows of desks and chairs. At the sound of a bell, you go to one of these rooms together with 30 other kids who were all born the same year as you. Every hour some grown-up walks in and starts talking. They are all paid to do so by the government. One of them tells you about the shape of the Earth, another tells you about the human past, and a third tells you about the human body. It is easy to laugh at this model, and almost everybody agrees that no matter its past achievements, it is now bankrupt. But so far we haven’t created a viable alter- native. Certainly not a scaleable alternative that can be implemented in rural Mexico rather than just in upmarket California suburbs.

Part three: Hacking humans

So the best advice I could give a 15-year-old stuck in an outdated school somewhere in Mexico, India or Alabama is: don’t rely on the adults too much. Most of them mean well, but they just don’t understand the world. In the past, it was a relatively safe bet to follow the adults, because they knew the world quite well, and the world changed slowly. But the 21st century is going to be different. Due to the growing pace of change, you can never be certain whether what the adults are telling you is timeless wisdom or outdated bias.

So on what can you rely instead? Technology? That’s an even riskier gamble. Technology can help you a lot, but if technology gains too much power over your life, you might become a hostage to its agenda. Thousands of years ago, humans invented agriculture, but this technology enriched just a tiny elite, while enslaving the majority of humans. Most people found themselves working from sunrise till sunset plucking weeds, carrying water buckets and harvesting corn under a blazing sun. It can happen to you too.

Technology isn’t bad. If you know what you want in life, technology can help you get it. But if you don’t know what you want in life, it will be all too easy for technology to shape your aims for you and take control of your life. Especially as technology gets better at understanding humans, you might increasingly find yourself serving it, instead of it serving you. Have you seen those zombies who roam the streets with their faces glued to their smartphones? Do you think they control the technology, or does the technology control them?

Should you rely on yourself, then? That sounds great on Sesame Street or in an old-fashioned Disney film, but in real life it doesn’t work so well. Even Disney is coming to realise it. Just like Inside Ou t’s Riley Andersen , most people hardly know themselves, and when they try to “listen to themselves” they easily become prey to external manipulations. The voice we hear inside our heads was never trustworthy, because it always reflected state propaganda, ideological brainwashing and commercial advertisement, not to mention biochemical bugs.

As biotechnology and machine learning improve, it will become easier to manipulate people’s deepest emotions and desires, and it will become more dangerous than ever to just follow your heart. When Coca-Cola, Amazon, Baidu or the government knows how to pull the strings of your heart and press the buttons of your brain, could you still tell the difference between your self and their marketing experts?

To succeed in such a daunting task, you will need to work very hard on getting to know your operating system better. To know what you are, and what you want from life. This is, of course, the oldest advice in the book: know thyself. For thousands of years, philosophers and prophets have urged people to know themselves. But this advice was never more urgent than in the 21st century, because unlike in the days of Laozi or Socrates, now you have serious competition. Coca-Cola, Amazon, Baidu and the government are all racing to hack you. Not your smartphone, not your computer, and not your bank account – they are in a race to hack you , and your organic operating system. You might have heard that we are living in the era of hacking computers, but that’s hardly half the truth. In fact, we are living in the era of hacking humans.

The algorithms are watching you right now. They are watching where you go, what you buy, who you meet. Soon they will monitor all your steps, all your breaths, all your heartbeats. They are relying on Big Data and machine learning to get to know you better and better. And once these algorithms know you better than you know yourself, they could control and manipulate you, and you won’t be able to do much about it. You will live in the matrix, or in The Truman Show . In the end, it’s a simple empirical matter: if the algorithms indeed understand what’s happening within you better than you understand it, authority will shift to them.

Of course, you might be perfectly happy ceding all authority to the algorithms and trusting them to decide things for you and for the rest of the world. If so, just relax and enjoy the ride. You don’t need to do anything about it. The algorithms will take care of everything. If, however, you want to retain some control of your personal existence and of the future of life, you have to run faster than the algorithms, faster than Amazon and the government, and get to know yourself before they do. To run fast, don’t take much luggage with you. Leave all your illusions behind. They are very heavy.

Yuval Noah Harari's 21 Lessons for the 21st Century (Vintage Digital) is published on August 30

This article was originally published by WIRED UK

What will humans look like in a million years?

By Lucy Jones

To understand our future evolution we need to look to our past.

Will our descendants be cyborgs with hi-tech machine implants, regrowable limbs and cameras for eyes like something out of a science fiction novel?

Might humans morph into a hybrid species of biological and artificial beings? Or could we become smaller or taller, thinner or fatter, or even with different facial features and skin colour?

Of course, we don’t know, but to consider the question, let’s scoot back a million years to see what humans looked like then. For a start, Homo sapiens didn’t exist. A million years ago, there were probably a few different species of humans around, including Homo heidelbergensi s, which shared similarities with both Homo erectus and modern humans, but more primitive anatomy than the later Neanderthal.

Over more recent history, during the last 10,000 years, there have been significant changes for humans to adapt to. Agricultural living and plentiful food have led to health problems that we’ve used science to solve, such as treating diabetes with insulin. In terms of looks, humans have become fatter and, in some areas, taller.

More on Science

Perhaps, then, we could evolve to be smaller so our bodies would need less energy, suggests Thomas Mailund, Senior Lecturer in Bioinformatics and Big Data at Anglia Ruskin University, London, which would be handy on a highly-populated planet.

Living alongside lots of people is a new condition humans have to adapt to. Back when we were hunter gatherers, there would’ve been a handful of interactions on a daily basis. Mailund suggests we may evolve in ways that help us to deal with this. Remembering people’s names, for example, could become a much more important skill.

Here’s where the technology comes in. “An implant in the brain would allow us to remember people’s names,” says Thomas. “We know what genes are involved in building a brain that’s good at remembering people’s names. We might just change that. It sounds more like science fiction. But we can do that right now. We can implant it but we don’t know how to wire it up to make it useful. We’re getting there but it’s very experimental.”

We know what genes are involved in building a brain that’s good at remembering people’s names. We might just change that." Thomas Mailund Associate Professor in Bioinformatics

“It’s not really a biological question anymore, it’s technological,” he said.

Currently, people have implants to fix an element of the body that’s broken, such as a pacemaker or a hip implant. Perhaps in the future, implants will be used simply to improve a person. As well as brain implants, we might have more visible parts of technology as an element of our appearance, such an artificial eye with a camera that can read different frequencies of colour and visuals.

We’ve all heard of designer babies. Scientists already have the technology to change the genes of an embryo, though it’s controversial and no one’s sure what happens next. But in the future, Mailund suggests, it may be seen as unethical not to change certain genes. With that may come choice about a baby’s features, so perhaps humans will look like what their parents want them to look like.

“It’s still going to be selection, it’s just artificial selection now. What we do with breeds of dogs, we’ll do with humans,” said Mailun.

This is all rather hypothetical, but can demographic trends give us any sense of what we may look like in the future?

Predicting out a million years is pure speculation, but predicting into the more immediate future is certainly possible using bioinformatics..." Dr. Jason A. Hodgson Lecturer in Grand Challenges in Ecosystems and the Environment

“Predicting out a million years is pure speculation, but predicting into the more immediate future is certainly possible using bioinformatics by combining what is known about genetic variation now with models of demographic change going forward,” says Dr. Jason A. Hodgson, Lecturer, Grand Challenges in Ecosystems and the Environment.

Now we have genetic samples of complete genomes from humans around the world, geneticists are getting a better understanding of genetic variation and how it’s structured in a human population. We can’t exactly predict how genetic variation will change, but scientists in the field of bioinformatics are looking to demographic trends to give us some idea.

Hodgson predicts urban and rural areas will become increasingly genetically diverse. “All the migration comes from rural areas into cities so you get an increase in genetic diversity in cities and a decrease in rural areas,” he said. “What you might see is differentiation along lines where people live.”

It will vary across the world but in the UK, for example, rural areas are less diverse and have more ancestry that’s been in Britain for a longer period of time compared with urban areas which have a higher population of migrants.

Some groups are reproducing at higher or lower rates. Populations in Africa, for example, are rapidly expanding so those genes increase at a higher frequency on a global population level. Areas of light skin colour are reproducing at lower rates. Therefore, Hodgson predicts, skin colour from a global perspective will get darker.

“It’s almost certainly the case that dark skin colour is increasing in frequency on a global scale relative to light skin colour,” he said. “I’d expect that the average person several generations out from now will have darker skin colour than they do now.”

And what about space? If humans do end up colonising Mars, what would we evolve to look like? With lower gravity, the muscles of our bodies could change structure. Perhaps we will have longer arms and legs. In a colder, Ice-Age type climate, could we even become even chubbier, with insulating body hair, like our Neanderthal relatives?

We don’t know, but, certainly, human genetic variation is increasing. Worldwide there are roughly two new mutations for every one of the 3.5 billion base pairs in the human genome every year, says Hodgson. Which is pretty amazing - and makes it unlikely we will look the same in a million years.

Featured image © Getty | Donald Iain Smith

Inspiration

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Humans

Experts say the rise of artificial intelligence will make most people better off over the next decade, but many have concerns about how advances in AI will affect what it means to be human, to be productive and to exercise free will

Table of contents.

- 1. Concerns about human agency, evolution and survival

- 2. Solutions to address AI’s anticipated negative impacts

- 3. Improvements ahead: How humans and AI might evolve together in the next decade

- About this canvassing of experts

- Acknowledgments

Digital life is augmenting human capacities and disrupting eons-old human activities. Code-driven systems have spread to more than half of the world’s inhabitants in ambient information and connectivity, offering previously unimagined opportunities and unprecedented threats. As emerging algorithm-driven artificial intelligence (AI) continues to spread, will people be better off than they are today?

Some 979 technology pioneers, innovators, developers, business and policy leaders, researchers and activists answered this question in a canvassing of experts conducted in the summer of 2018.

The experts predicted networked artificial intelligence will amplify human effectiveness but also threaten human autonomy, agency and capabilities. They spoke of the wide-ranging possibilities; that computers might match or even exceed human intelligence and capabilities on tasks such as complex decision-making, reasoning and learning, sophisticated analytics and pattern recognition, visual acuity, speech recognition and language translation. They said “smart” systems in communities, in vehicles, in buildings and utilities, on farms and in business processes will save time, money and lives and offer opportunities for individuals to enjoy a more-customized future.

Many focused their optimistic remarks on health care and the many possible applications of AI in diagnosing and treating patients or helping senior citizens live fuller and healthier lives. They were also enthusiastic about AI’s role in contributing to broad public-health programs built around massive amounts of data that may be captured in the coming years about everything from personal genomes to nutrition. Additionally, a number of these experts predicted that AI would abet long-anticipated changes in formal and informal education systems.

Yet, most experts, regardless of whether they are optimistic or not, expressed concerns about the long-term impact of these new tools on the essential elements of being human. All respondents in this non-scientific canvassing were asked to elaborate on why they felt AI would leave people better off or not. Many shared deep worries, and many also suggested pathways toward solutions. The main themes they sounded about threats and remedies are outlined in the accompanying table.

[chart id=”21972″]

Specifically, participants were asked to consider the following:

“Please think forward to the year 2030. Analysts expect that people will become even more dependent on networked artificial intelligence (AI) in complex digital systems. Some say we will continue on the historic arc of augmenting our lives with mostly positive results as we widely implement these networked tools. Some say our increasing dependence on these AI and related systems is likely to lead to widespread difficulties.

Our question: By 2030, do you think it is most likely that advancing AI and related technology systems will enhance human capacities and empower them? That is, most of the time, will most people be better off than they are today? Or is it most likely that advancing AI and related technology systems will lessen human autonomy and agency to such an extent that most people will not be better off than the way things are today?”

Overall, and despite the downsides they fear, 63% of respondents in this canvassing said they are hopeful that most individuals will be mostly better off in 2030, and 37% said people will not be better off.

A number of the thought leaders who participated in this canvassing said humans’ expanding reliance on technological systems will only go well if close attention is paid to how these tools, platforms and networks are engineered, distributed and updated. Some of the powerful, overarching answers included those from:

Sonia Katyal , co-director of the Berkeley Center for Law and Technology and a member of the inaugural U.S. Commerce Department Digital Economy Board of Advisors, predicted, “In 2030, the greatest set of questions will involve how perceptions of AI and their application will influence the trajectory of civil rights in the future. Questions about privacy, speech, the right of assembly and technological construction of personhood will all re-emerge in this new AI context, throwing into question our deepest-held beliefs about equality and opportunity for all. Who will benefit and who will be disadvantaged in this new world depends on how broadly we analyze these questions today, for the future.”

We need to work aggressively to make sure technology matches our values. Erik Brynjolfsson Erik Brynjolfsson

Erik Brynjolfsson , director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy and author of “Machine, Platform, Crowd: Harnessing Our Digital Future,” said, “AI and related technologies have already achieved superhuman performance in many areas, and there is little doubt that their capabilities will improve, probably very significantly, by 2030. … I think it is more likely than not that we will use this power to make the world a better place. For instance, we can virtually eliminate global poverty, massively reduce disease and provide better education to almost everyone on the planet. That said, AI and ML [machine learning] can also be used to increasingly concentrate wealth and power, leaving many people behind, and to create even more horrifying weapons. Neither outcome is inevitable, so the right question is not ‘What will happen?’ but ‘What will we choose to do?’ We need to work aggressively to make sure technology matches our values. This can and must be done at all levels, from government, to business, to academia, and to individual choices.”

Bryan Johnson , founder and CEO of Kernel, a leading developer of advanced neural interfaces, and OS Fund, a venture capital firm, said, “I strongly believe the answer depends on whether we can shift our economic systems toward prioritizing radical human improvement and staunching the trend toward human irrelevance in the face of AI. I don’t mean just jobs; I mean true, existential irrelevance, which is the end result of not prioritizing human well-being and cognition.”

Marina Gorbis , executive director of the Institute for the Future, said, “Without significant changes in our political economy and data governance regimes [AI] is likely to create greater economic inequalities, more surveillance and more programmed and non-human-centric interactions. Every time we program our environments, we end up programming ourselves and our interactions. Humans have to become more standardized, removing serendipity and ambiguity from our interactions. And this ambiguity and complexity is what is the essence of being human.”

Judith Donath , author of “The Social Machine, Designs for Living Online” and faculty fellow at Harvard University’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, commented, “By 2030, most social situations will be facilitated by bots – intelligent-seeming programs that interact with us in human-like ways. At home, parents will engage skilled bots to help kids with homework and catalyze dinner conversations. At work, bots will run meetings. A bot confidant will be considered essential for psychological well-being, and we’ll increasingly turn to such companions for advice ranging from what to wear to whom to marry. We humans care deeply about how others see us – and the others whose approval we seek will increasingly be artificial. By then, the difference between humans and bots will have blurred considerably. Via screen and projection, the voice, appearance and behaviors of bots will be indistinguishable from those of humans, and even physical robots, though obviously non-human, will be so convincingly sincere that our impression of them as thinking, feeling beings, on par with or superior to ourselves, will be unshaken. Adding to the ambiguity, our own communication will be heavily augmented: Programs will compose many of our messages and our online/AR appearance will [be] computationally crafted. (Raw, unaided human speech and demeanor will seem embarrassingly clunky, slow and unsophisticated.) Aided by their access to vast troves of data about each of us, bots will far surpass humans in their ability to attract and persuade us. Able to mimic emotion expertly, they’ll never be overcome by feelings: If they blurt something out in anger, it will be because that behavior was calculated to be the most efficacious way of advancing whatever goals they had ‘in mind.’ But what are those goals? Artificially intelligent companions will cultivate the impression that social goals similar to our own motivate them – to be held in good regard, whether as a beloved friend, an admired boss, etc. But their real collaboration will be with the humans and institutions that control them. Like their forebears today, these will be sellers of goods who employ them to stimulate consumption and politicians who commission them to sway opinions.”

Andrew McLaughlin , executive director of the Center for Innovative Thinking at Yale University, previously deputy chief technology officer of the United States for President Barack Obama and global public policy lead for Google, wrote, “2030 is not far in the future. My sense is that innovations like the internet and networked AI have massive short-term benefits, along with long-term negatives that can take decades to be recognizable. AI will drive a vast range of efficiency optimizations but also enable hidden discrimination and arbitrary penalization of individuals in areas like insurance, job seeking and performance assessment.”

Michael M. Roberts , first president and CEO of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) and Internet Hall of Fame member, wrote, “The range of opportunities for intelligent agents to augment human intelligence is still virtually unlimited. The major issue is that the more convenient an agent is, the more it needs to know about you – preferences, timing, capacities, etc. – which creates a tradeoff of more help requires more intrusion. This is not a black-and-white issue – the shades of gray and associated remedies will be argued endlessly. The record to date is that convenience overwhelms privacy. I suspect that will continue.”

danah boyd , a principal researcher for Microsoft and founder and president of the Data & Society Research Institute, said, “AI is a tool that will be used by humans for all sorts of purposes, including in the pursuit of power. There will be abuses of power that involve AI, just as there will be advances in science and humanitarian efforts that also involve AI. Unfortunately, there are certain trend lines that are likely to create massive instability. Take, for example, climate change and climate migration. This will further destabilize Europe and the U.S., and I expect that, in panic, we will see AI be used in harmful ways in light of other geopolitical crises.”

Amy Webb , founder of the Future Today Institute and professor of strategic foresight at New York University, commented, “The social safety net structures currently in place in the U.S. and in many other countries around the world weren’t designed for our transition to AI. The transition through AI will last the next 50 years or more. As we move farther into this third era of computing, and as every single industry becomes more deeply entrenched with AI systems, we will need new hybrid-skilled knowledge workers who can operate in jobs that have never needed to exist before. We’ll need farmers who know how to work with big data sets. Oncologists trained as robotocists. Biologists trained as electrical engineers. We won’t need to prepare our workforce just once, with a few changes to the curriculum. As AI matures, we will need a responsive workforce, capable of adapting to new processes, systems and tools every few years. The need for these fields will arise faster than our labor departments, schools and universities are acknowledging. It’s easy to look back on history through the lens of present – and to overlook the social unrest caused by widespread technological unemployment. We need to address a difficult truth that few are willing to utter aloud: AI will eventually cause a large number of people to be permanently out of work. Just as generations before witnessed sweeping changes during and in the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution, the rapid pace of technology will likely mean that Baby Boomers and the oldest members of Gen X – especially those whose jobs can be replicated by robots – won’t be able to retrain for other kinds of work without a significant investment of time and effort.”

Barry Chudakov , founder and principal of Sertain Research, commented, “By 2030 the human-machine/AI collaboration will be a necessary tool to manage and counter the effects of multiple simultaneous accelerations: broad technology advancement, globalization, climate change and attendant global migrations. In the past, human societies managed change through gut and intuition, but as Eric Teller, CEO of Google X, has said, ‘Our societal structures are failing to keep pace with the rate of change.’ To keep pace with that change and to manage a growing list of ‘wicked problems’ by 2030, AI – or using Joi Ito’s phrase, extended intelligence – will value and revalue virtually every area of human behavior and interaction. AI and advancing technologies will change our response framework and time frames (which in turn, changes our sense of time). Where once social interaction happened in places – work, school, church, family environments – social interactions will increasingly happen in continuous, simultaneous time. If we are fortunate, we will follow the 23 Asilomar AI Principles outlined by the Future of Life Institute and will work toward ‘not undirected intelligence but beneficial intelligence.’ Akin to nuclear deterrence stemming from mutually assured destruction, AI and related technology systems constitute a force for a moral renaissance. We must embrace that moral renaissance, or we will face moral conundrums that could bring about human demise. … My greatest hope for human-machine/AI collaboration constitutes a moral and ethical renaissance – we adopt a moonshot mentality and lock arms to prepare for the accelerations coming at us. My greatest fear is that we adopt the logic of our emerging technologies – instant response, isolation behind screens, endless comparison of self-worth, fake self-presentation – without thinking or responding smartly.”

John C. Havens , executive director of the IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems and the Council on Extended Intelligence, wrote, “Now, in 2018, a majority of people around the world can’t access their data, so any ‘human-AI augmentation’ discussions ignore the critical context of who actually controls people’s information and identity. Soon it will be extremely difficult to identify any autonomous or intelligent systems whose algorithms don’t interact with human data in one form or another.”

At stake is nothing less than what sort of society we want to live in and how we experience our humanity. Batya Friedman Batya Friedman

Batya Friedman , a human-computer interaction professor at the University of Washington’s Information School, wrote, “Our scientific and technological capacities have and will continue to far surpass our moral ones – that is our ability to use wisely and humanely the knowledge and tools that we develop. … Automated warfare – when autonomous weapons kill human beings without human engagement – can lead to a lack of responsibility for taking the enemy’s life or even knowledge that an enemy’s life has been taken. At stake is nothing less than what sort of society we want to live in and how we experience our humanity.”

Greg Shannon , chief scientist for the CERT Division at Carnegie Mellon University, said, “Better/worse will appear 4:1 with the long-term ratio 2:1. AI will do well for repetitive work where ‘close’ will be good enough and humans dislike the work. … Life will definitely be better as AI extends lifetimes, from health apps that intelligently ‘nudge’ us to health, to warnings about impending heart/stroke events, to automated health care for the underserved (remote) and those who need extended care (elder care). As to liberty, there are clear risks. AI affects agency by creating entities with meaningful intellectual capabilities for monitoring, enforcing and even punishing individuals. Those who know how to use it will have immense potential power over those who don’t/can’t. Future happiness is really unclear. Some will cede their agency to AI in games, work and community, much like the opioid crisis steals agency today. On the other hand, many will be freed from mundane, unengaging tasks/jobs. If elements of community happiness are part of AI objective functions, then AI could catalyze an explosion of happiness.”

Kostas Alexandridis , author of “Exploring Complex Dynamics in Multi-agent-based Intelligent Systems,” predicted, “Many of our day-to-day decisions will be automated with minimal intervention by the end-user. Autonomy and/or independence will be sacrificed and replaced by convenience. Newer generations of citizens will become more and more dependent on networked AI structures and processes. There are challenges that need to be addressed in terms of critical thinking and heterogeneity. Networked interdependence will, more likely than not, increase our vulnerability to cyberattacks. There is also a real likelihood that there will exist sharper divisions between digital ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots,’ as well as among technologically dependent digital infrastructures. Finally, there is the question of the new ‘commanding heights’ of the digital network infrastructure’s ownership and control.”

Oscar Gandy , emeritus professor of communication at the University of Pennsylvania, responded, “We already face an ungranted assumption when we are asked to imagine human-machine ‘collaboration.’ Interaction is a bit different, but still tainted by the grant of a form of identity – maybe even personhood – to machines that we will use to make our way through all sorts of opportunities and challenges. The problems we will face in the future are quite similar to the problems we currently face when we rely upon ‘others’ (including technological systems, devices and networks) to acquire things we value and avoid those other things (that we might, or might not be aware of).”

James Scofield O’Rourke , a professor of management at the University of Notre Dame, said, “Technology has, throughout recorded history, been a largely neutral concept. The question of its value has always been dependent on its application. For what purpose will AI and other technological advances be used? Everything from gunpowder to internal combustion engines to nuclear fission has been applied in both helpful and destructive ways. Assuming we can contain or control AI (and not the other way around), the answer to whether we’ll be better off depends entirely on us (or our progeny). ‘The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves, that we are underlings.’”

Simon Biggs , a professor of interdisciplinary arts at the University of Edinburgh, said, “AI will function to augment human capabilities. The problem is not with AI but with humans. As a species we are aggressive, competitive and lazy. We are also empathic, community minded and (sometimes) self-sacrificing. We have many other attributes. These will all be amplified. Given historical precedent, one would have to assume it will be our worst qualities that are augmented. My expectation is that in 2030 AI will be in routine use to fight wars and kill people, far more effectively than we can currently kill. As societies we will be less affected by this as we currently are, as we will not be doing the fighting and killing ourselves. Our capacity to modify our behaviour, subject to empathy and an associated ethical framework, will be reduced by the disassociation between our agency and the act of killing. We cannot expect our AI systems to be ethical on our behalf – they won’t be, as they will be designed to kill efficiently, not thoughtfully. My other primary concern is to do with surveillance and control. The advent of China’s Social Credit System (SCS) is an indicator of what it likely to come. We will exist within an SCS as AI constructs hybrid instances of ourselves that may or may not resemble who we are. But our rights and affordances as individuals will be determined by the SCS. This is the Orwellian nightmare realised.”

Mark Surman , executive director of the Mozilla Foundation, responded, “AI will continue to concentrate power and wealth in the hands of a few big monopolies based on the U.S. and China. Most people – and parts of the world – will be worse off.”

William Uricchio , media scholar and professor of comparative media studies at MIT, commented, “AI and its related applications face three problems: development at the speed of Moore’s Law, development in the hands of a technological and economic elite, and development without benefit of an informed or engaged public. The public is reduced to a collective of consumers awaiting the next technology. Whose notion of ‘progress’ will prevail? We have ample evidence of AI being used to drive profits, regardless of implications for long-held values; to enhance governmental control and even score citizens’ ‘social credit’ without input from citizens themselves. Like technologies before it, AI is agnostic. Its deployment rests in the hands of society. But absent an AI-literate public, the decision of how best to deploy AI will fall to special interests. Will this mean equitable deployment, the amelioration of social injustice and AI in the public service? Because the answer to this question is social rather than technological, I’m pessimistic. The fix? We need to develop an AI-literate public, which means focused attention in the educational sector and in public-facing media. We need to assure diversity in the development of AI technologies. And until the public, its elected representatives and their legal and regulatory regimes can get up to speed with these fast-moving developments we need to exercise caution and oversight in AI’s development.”

The remainder of this report is divided into three sections that draw from hundreds of additional respondents’ hopeful and critical observations: 1) concerns about human-AI evolution, 2) suggested solutions to address AI’s impact, and 3) expectations of what life will be like in 2030, including respondents’ positive outlooks on the quality of life and the future of work, health care and education. Some responses are lightly edited for style.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Artificial Intelligence

- Emerging Technology

- Future of the Internet (Project)

- Technology Adoption

Majority of Americans aren’t confident in the safety and reliability of cryptocurrency

Americans in both parties are concerned over the impact of ai on the 2024 presidential campaign, a quarter of u.s. teachers say ai tools do more harm than good in k-12 education, many americans think generative ai programs should credit the sources they rely on, americans’ use of chatgpt is ticking up, but few trust its election information, most popular, report materials.

- Shareable quotes from experts about artificial intelligence and the future of humans

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

May 12, 2021

How Much Time Does Humanity Have Left?

Statistics tell us that individuals are most likely to be somewhere around the middle part of their life. The same could be true of the human race

By Avi Loeb

Getty Images

My advice to young scientists who seek a sense of purpose in their research is to engage in a topic that matters to society, such as moderating climate change, streamlining the development of vaccines, satisfying our energy or food needs, establishing a sustainable base in space or finding technological relics of alien civilizations . Broadly speaking, society funds science, and scientists should reciprocate by attending to the public’s interests.

The most vital societal challenge is to extend the longevity of humanity. At a recent lecture to Harvard alumni I was asked how long I expect our technological civilization to survive. My response was based on the fact that we usually find ourselves around the middle part of our lives, as originally argued by Richard Gott. The chance of being an infant on the first day after birth is tens of thousand times smaller than of being an adult. It is equally unlikely to live merely a century after the beginning of our technological era if this phase is going to last millions of years into the future. In the more likely case that we are currently witnessing the adulthood of our technological lifespan, we are likely to survive a few centuries but not much longer. After stating this statistical verdict publicly, I realized what a horrifying forecast it entails. But is our statistical fate inevitable?

There is a silver lining lurking in the background. It involves the possibility that we possess free will and can respond to deteriorating conditions by promoting a longer future than a few centuries. Wise public policy could mitigate the risk from technological catastrophes associated with climate change, self-inflicted pandemics or wars.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

It is unclear whether our policy makers will actually respond to the challenges that lie ahead and save us from the above statistical verdict. Humans are not good at coping with risks they have never encountered before, as exemplified by the politics of climate change.

This brings us back to the fatalistic view. The Standard Model of physics presumes that we are all made of elementary particles with no additional constituents. As such composite systems, we do not possess freedom at a fundamental level, because all particles and their interactions follow the laws of physics. Given that perspective, what we interpret as “free will” merely encapsulates uncertainties associated with the complex set of circumstances that affect human actions. These uncertainties are substantial on the scale of an individual but average out when dealing with a large sample. Humans and their complex interactions evade a sense of predictability at the personal level, but perhaps the destiny of our civilization as a whole is shaped by our past in an inevitable statistical sense.

The forecast of how much time we have left in our technological future could then follow from statistical information about the fate of civilizations like ours that predated us and lived under similar physical constraints. Most stars formed billions of years before the sun and may have fostered technological civilizations on their habitable planets that perished by now. If we had historical data on the life span of a large number of them, we could have calculated the likelihood of our civilization to survive for different periods of time. The approach would be similar to calibrating the likelihood of a radioactive atom to decay based on the documented behavior of numerous other atoms of the same type. In principle, we could gather related data by engaging in space archaeology and searching the sky for relics of dead technological civilizations. This would presume that the fate of our civilization is dictated by the physical constraints.

But once confronted with the probability distribution for survival, the human spirit may choose to defy all odds and behave as a statistical outlier. For example, our chance for survival could improve if some people choose to move away from Earth. Currently, all our eggs are in one basket. Venturing into space offers the advantage of preserving our civilization from a single-planet disaster. Although Earth serves as a comfortable home at the moment, we will ultimately be forced to relocate because the sun will boil off all liquid water on our planet’s surface within a billion years. Establishing multiple communities of humans on other worlds would resemble the duplication of the Bible by the Gutenberg printing press around 1455, which prevented loss of precious content through a single-point catastrophe.

Of course, even a short-distance travel from Earth to Mars raises major health hazards from cosmic rays, energetic solar particles, UV radiation, lack of a breathable atmosphere and low gravity. Overcoming the challenges of settling on Mars will also improve our ability to recognize terraformed planets around other stars based on our own experience. Despite this vision, being conscious of challenges on Earth might deter humanity from embracing a bold perspective on space travel. One can argue that we have enough problems at home and ask : “Why waste valuable time and money on space ventures that are not devoted to our most urgent needs right here on planet Earth?”

Before surrendering to this premise, we should recognize that attending strictly to mundane goals will not provide us with the broader skill set necessary to adapt to changing circumstances in the long run. A narrow focus on temporary irritants would resemble historical obsessions that ended up being irrelevant, such as “ How can we remove the increasing volumes of horse manure from city streets? ” before the automobile was invented or “ How do you construct a huge physical grid of telephone landlines? ” before the cell phone was invented.