Sparks Gallery

- Exhibitions

- Take Our Collector Quiz

- Custom Murals

- News & Events

What is Abstract Art? Definition & Examples

Abstract art is a non-objective art form that breaks traditional, realistic art styles. It intends to inspire emotion and intangible experience, rather than telling a story or portraying realistic subjects.

While it exists today in many forms, both two and three-dimensionally, abstract art disrupted the art world when it abandoned realistic representation of subject matter. We’ll explore the characteristics, styles, and examples of abstract art that still influence artists today.

Characteristics of Abstract Art

The main characteristics of abstract art include the following:

- Strong valuation of colors, shapes, lines, and textures

- No recognizable objects

- Non-representational

- The opposite of figurative, realistic, or Renaissance style

- Freedom of form and interpretation

The Purpose of Abstract Art

Abstract art’s main purpose is to spark the imagination and invoke a personal emotional experience. The best abstract art can create a different experience depending on one’s personality or mood.

Abstract art is about the balance or unbalance of form, line, composition, and color to achieve harmony, or disarray. Some pieces may be focused on the method in which the piece is made and which materials are involved. Others focus on the movement of the paint across the canvas or panel.

Do you enjoy contemporary art that evokes emotion and strong themes? View our current exhibitions of prominent Southern California artists.

Types of Abstract Art

Abstract art can be broken down into smaller categories based on several factors, including medium and technique. However, the most common types of abstract art include the following:

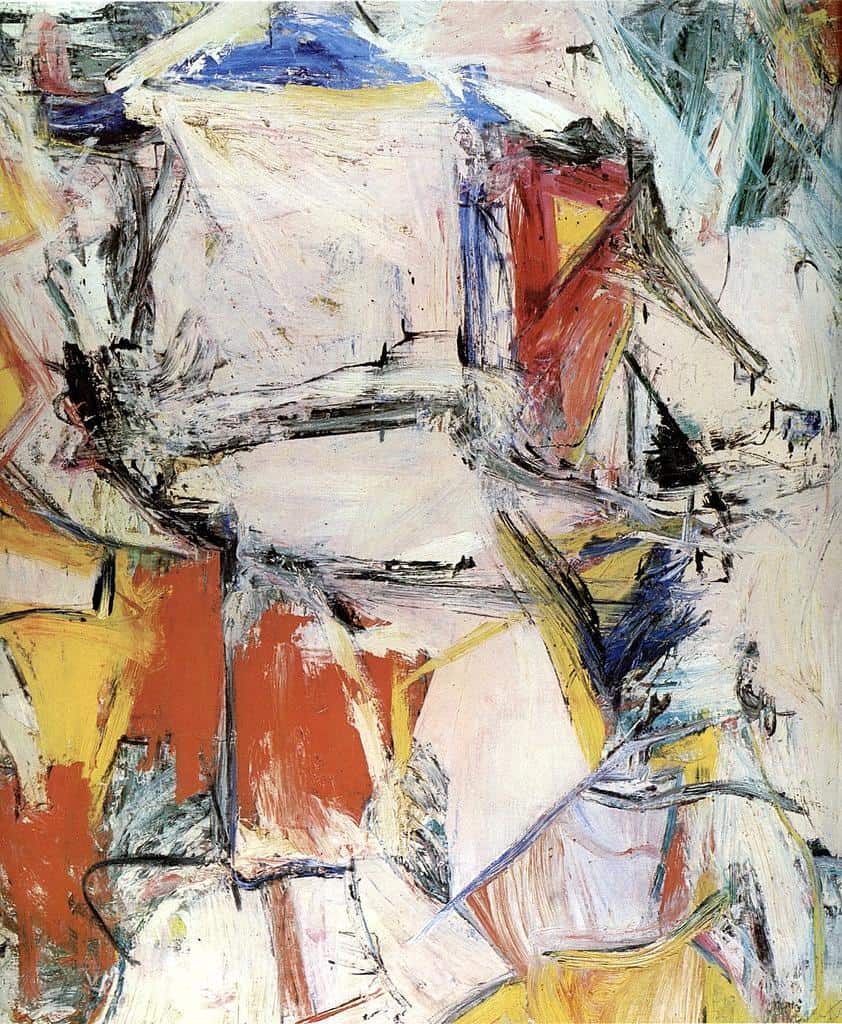

- Expressive abstraction: For this type, the painter uses their intuition and expressive brushstrokes to create abstract paintings. Willem De Kooning’s works are representative of this style. The artist’s physical body movement while creating the work may be seen in their marks on the artwork.

- Action painting/gestural abstraction: Gestural abstraction is a subcategory of expressive abstraction popularized by artists including Jackson Pollock. The artist uses spontaneous movements, making this artwork dynamic and highly expressive. The artist’s physical body movements are the main contributor of the marks on the work.

- Minimalism abstraction: Minimal abstraction takes inspiration from other styles and techniques, including minimalism art, color field and hard edge painting, and abstract expressionism. This leads to artwork characterized by simplicity and pure abstraction, such as the works of Agnes Martin and Donald Judd.

- Conceptual abstraction: This type of art comes from ideas and is therefore not limited by the restraints of representing the physical world.

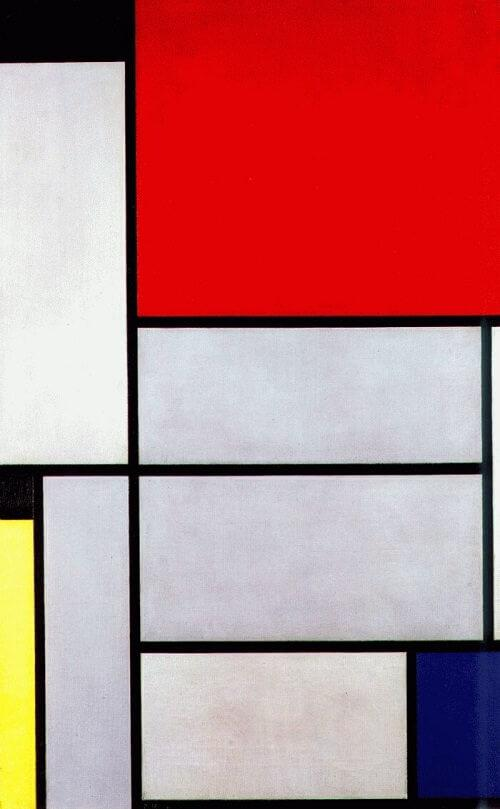

- Hard-edge painting: Hard-edge painting is characterized by clean, often straight, edges separating the colors. Notable artists that utilize this style include Josef Albers, Piet Mondrain, and Carmen Herrera.

- Optical abstraction: Optical abstraction is a sub-type of hard-edge painting that produces optical illusions. These pieces create depth on a two-dimensional surface. Notable artists for this style include Victor Vasarely, Bridget Riley, and Richard Anuszkiewicz.

- Geometric abstraction: This is also a subcategory of hard-edge paintings that uses geometric figures in the composition. Josef Albers and Winfred Gaul are well-known artists.

- Color field painting: Color field painting can be categorized by large areas of color, usually with minimal details, though with lots of depth. Often, these pieces are created on large-scale canvases. Mark Rothko is a well-known pioneer.

History of Abstract Art

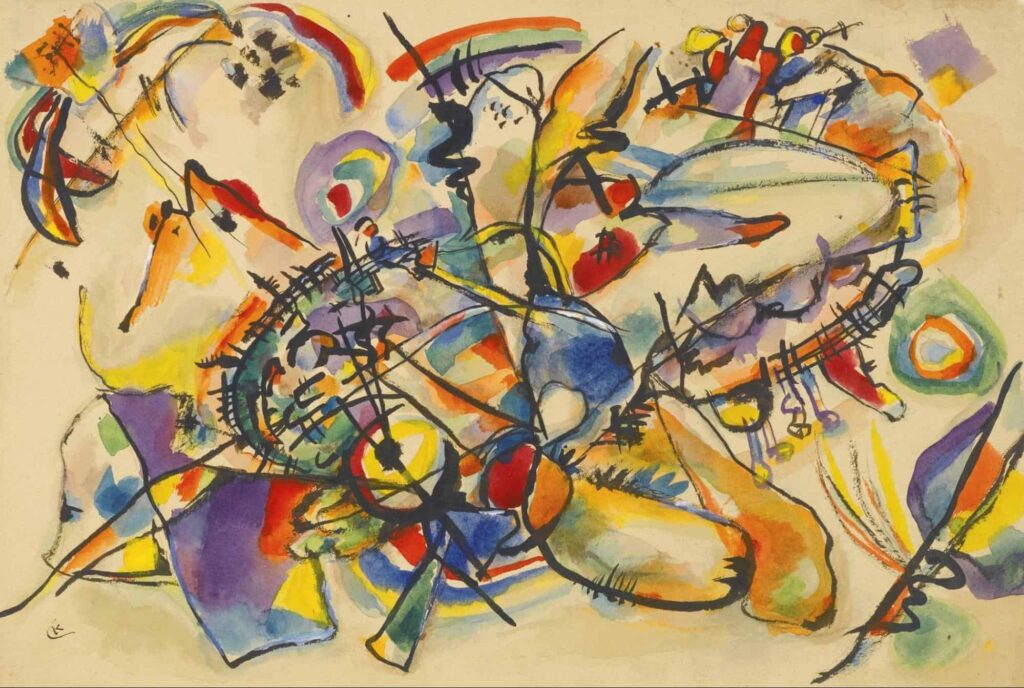

Non-representational and pattern focused art has existed across time and cultures. However, the first modern artist to create artwork with non-representational forms was Wassily Kandinsky who in 1910 broke away from the traditions of figurative art to produce his first untitled abstract watercolor. He was inspired by a Monet painting of haystacks, where he realized that color and form could be powerful on their own and the object of the painting did not need to be clear or even present.

Although some argue that Hilma af Klint may have produced the first abstract piece in 1906, her work wasn’t seen by the public until much later. Regardless, Kandinsky introduced abstract art to the mainstream art world when he published “ Concerning the Spiritual in Art ” in 1912, creating a theoretical basis for abstract art.

In the early 20th century, other artists began experimenting and introducing different types and forms of abstract art. Piet Mondrian introduced geometric elements in the 1920s, and Jackson Pollock pioneered drip or action painting in the 1940s and1950s to provoke strong emotions.

After World War II, abstract art grew in popularity because it gave artists a way to express how they were feeling in a post-war era that conjured the horrors of war and the anxiety of an uncertain future.

What is Abstract Expressionism?

In New York City during the 1940s, the abstract expressionism movement gained international recognition. It was the first American art style to have international influence for its heavy surrealism, energy, lawlessness, and intensity. It is defined by artists like:

- Mark Rothko

- Willem de Kooning

- Jackson Pollock

- Matthew Dibble

As of writing, Willem de Kooning’s Interchange abstract landscape is the second most expensive painting that has ever been sold. A Chicago hedge fund manager bought the abstract piece for $300 million in 2015. Interchange was considered worth this value because of its unique story and list of previous owners comprising fascinating people from modern American history.

How Has Abstract Art Evolved?

Since its early beginnings, abstract art has influenced other movements and art styles like conceptual and minimalist art. And it continues to influence artists as they experiment with form, color, texture, and lines to spark emotion and feeling rather than reality.

Do you enjoy abstract and modern art? View available Abstract artwork at Sparks Gallery.

Notable Examples of Abstract Art

While there are countless popular and famous abstract artworks, we’ll spotlight a few that have influenced the art form and inspired movements. These poignant examples of abstract art continue to inspire:

Wassily Kandinsky’s Untitled

Untitled is the first abstract painting where Kandinsky freed his artwork from subject matter and form. He used color to convey emotion and feeling. It was this piece that launched abstract art onto the world stage.

Related Link: Daniel Ketelhut, “Figmented Reality”

Piet Mondrian’s Tableau

Piet Mondrian’s most famous abstract piece, Tableau , introduced the geometric style as a form of abstraction. He utilized mathematical precision, which was counter to the freeform nature of abstract art.

Jackson Pollock’s Full Fathom Five

One of New York’s abstract expressionists, Jackson Pollock, created Full Fathom Five using energetic colors and a new technique to illustrate the exploration of the subconscious. This piece also introduced texture into abstract art.

Helen Frankenthaler’s Mountains and Sea

Helen Frankenthaler created Mountains and Sea during the 1950s using a new technique of pouring paint thinned with turpentine right onto the canvas. The paint would soak through the canvas adding a new organic texture to her art. Because the paint was poured, the colors weren’t constrained by lines or shapes, creating a new Color Field Painting movement.

Abstract Art Remains Popular Today

Today, abstract art takes many forms, styles, textures, and materials as artists continue to push the boundaries of expression through non-objective forms. Abstract art continues to inspire, connect, and appeal to art lovers. Many appreciate its ability to evoke emotion through color and shapes.

Related Link: Installation: “Inverse” by Sage Serrano

Sparks Gallery celebrates the contemporary artwork of innovative Southern California artists. Our gallery hosts powerful abstract pieces with unique points of view.

Home — Essay Samples — Arts & Culture — Visual Arts — Abstract Art

Essays on Abstract Art

Introduction to world art, representational abstract art, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Analysis of The Impact and Influence of Abstract Art

Intricacies of a ballerina, main metaphors in "endgame", abstract expressionism art as a weapon of cold war, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Reflection on Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera Exhibition

The abstract expressionism movement and contemporary art, abstract expressionism: analysis of wassily kandinsky and arnold schoenberg, christian boltanski’s existential relationship with abstract expressionism, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Girl before a Mirror and Other Works: Balance and Perspective in Art

Art analysis paper examples, relevant topics.

- Interior Design

- Art in Architecture

- Architecture

- Photography

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

- Geometric Abstraction

Mechanical Elements

Fernand Léger

Standing Figure

Jean Hélion

Second Theme

Burgoyne Diller

Relational Painting Number 64

Fritz Glarner

Homage to the Square: With Rays

Josef Albers

Homage to the Square: Soft Spoken

Large Blue Horizontal

Ilya Bolotowsky

Magdalena Dabrowski Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004

The pictorial language of geometric abstraction, based on the use of simple geometric forms placed in nonillusionistic space and combined into nonobjective compositions, evolved as the logical conclusion of the Cubist destruction and reformulation of the established conventions of form and space. Initiated by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in 1907–8, Cubism subverted the traditional depiction relying upon the imitation of forms of the surrounding visual world in the illusionistic—post-Renaissance—perspectival space. The Analytic Cubist phase, which reached its peak in mid-1910, made available to artists the planarity of overlapping frontal surfaces held together by a linear grid. The next phase—Synthetic Cubism, 1912–14—introduced the flatly painted synthesized shapes, abstract space, and “constructional” elements of the composition. These three aspects became the fundamental characteristics of abstract geometric art. The freedom of experimentation with different materials and spatial relationships between various compositional parts, which evolved from the Cubist practice of collage and papiers collés (1912), also emphasized the flatness of the picture surface—as the carrier of applied elements—as well as the physical “reality” of the explored forms and materials. Geometric abstraction, through the Cubist process of purifying art of the vestiges of visual reality, focused on the inherent two-dimensional features of painting.

This process of evolving a purely pictorial reality built of elemental geometric forms assumed different stylistic expressions in various European countries and in Russia. In Holland, the main creator and the most important proponent of geometric abstract language was Piet Mondrian (1872–1944). Along with other members of the De Stijl group—Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931), Bart van der Leck (1876–1958), and Vilmos Huszár (1884–1960)—Mondrian’s work was intended to convey “absolute reality,” construed as the world of pure geometric forms underlying all existence and related according to the vertical-horizontal principle of straight lines and pure spectral colors. Mondrian’s geometric style, which he termed “Neoplasticism,” developed between 1915 and 1920. In that year, he published his manifesto “Le Néoplasticisme” and for the next two-and-a-half decades continued to work in his characteristic geometric style, expunged of all references to the real world, and posited on the geometric division of the canvas through black vertical and horizontal lines of varied thickness, complemented by blocks of primary colors, particularly blue, red, and yellow. Similar compositional principles underlie the work of the De Stijl artists, who applied them with slight formal modifications to achieve their independent, personal expression.

In Russia, the language of geometric abstraction first appeared in 1915 in the work of the avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) ( Museum of Modern Art , New York), in the style he termed Suprematism. Creating nonobjective compositions of elemental forms floating in white unstructured space, Malevich strove to achieve “the absolute,” the higher spiritual reality that he called the “fourth dimension.” Simultaneously, his compatriot Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953) originated a new geometric abstract idiom in an innovative three-dimensional form, which he first dubbed “painterly reliefs” and subsequently “counter-reliefs” (1915–17). These were assemblages of randomly found industrial materials whose geometric form was dictated by their inherent properties, such as wood, metal, or glass. That principle, which Tatlin called “the culture of materials,” spurred the rise of the Russian avant-garde movement Constructivism (1918–21), which explored geometric form in two and three dimensions. The main practitioners of Constructivism included Liubov Popova (1889–1924), Aleksandr Rodchenko (1891–1956) ( Museum of Modern Art , New York), Varvara Stepanova (1894–1958), and El Lissitzky (1890–1941). It was Lissitzky who became the transmitter of Constructivism to Germany, where its principles were later embodied in the teachings of the Bauhaus . Founded by the architect Walter Gropius in Weimar in 1919, it became during the 1920s (and until its dismantling by the Nazis in 1933) the vital proponent of geometric abstraction and experimental modern architecture. As a teaching institution, the Bauhaus encompassed different disciplines: painting, graphic arts, stage design, theater, and architecture. The art faculty was recruited from among the most distinguished painters of the time: Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee , Johannes Itten, Oskar Schlemmer, László Moholy-Nagy, Josef Albers, all of whom were devoted to the ideal of the purity of geometric form as the most appropriate expression of the modernist canon.

In France, during the 1920s, geometric abstraction manifested itself as the underlying principle of the Art Deco style, which propagated broad use of geometric form for ornamental purposes in the decorative and applied arts as well as in architecture. In the 1930s, Paris became the center of a geometric abstraction that arose out of its Synthetic Cubist sources and focused around the group Cercle et Carré (1930), and later Abstraction-Création (1932). With the outbreak of World War II, the focus of geometric abstraction shifted to New York, where the tradition was continued by the American Abstract Artists group (formed in 1937), including Burgoyne Diller and Ilya Bolotowsky. With the arrival of the Europeans Josef Albers (1933) and Piet Mondrian (1940), and such major events as the exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art (1936), organized by the Museum of Modern Art, and the creation of the Museum of Non-Objective Art (1939, now the Guggenheim), the geometric tradition acquired a new resonance, but it was essentially past its creative phase. Its influences, however, reached younger generations of artists, most directly affecting the Minimalist art of the 1960s, which used pure geometric form, stripped to its austere essentials, as the primary language of expression. Artists such as Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, and Dorothea Rockburne studied the geometric tradition and transformed it into their own artistic vocabulary.

Dabrowski, Magdalena. “Geometric Abstraction.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/geab/hd_geab.htm (October 2004)

Additional Essays by Magdalena Dabrowski

- Dabrowski, Magdalena. “ Henri Matisse (1869–1954) .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- Abstract Expressionism

- African Influences in Modern Art

- Fernand Léger (1881–1955)

- Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)

- Paul Klee (1879–1940)

- Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and American Photography

- Anselm Kiefer (born 1945)

- Art and Nationalism in Twentieth-Century Turkey

- The Bauhaus, 1919–1933

- Conceptual Art and Photography

- Design, 1900–1925

- Design, 1925–50

- Egyptian Modern Art

- Georges Seurat (1859–1891) and Neo-Impressionism

- Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986)

- Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

- International Pictorialism

- Jasper Johns (born 1930)

- Letterforms and Writing in Contemporary Art

- The Magic of Signs and Patterns in North African Art

- Modern Materials: Plastics

- Photojournalism and the Picture Press in Germany

- Post-Impressionism

- The Structure of Photographic Metaphors

- West Asia: Postmodernism, the Diaspora, and Women Artists

List of Rulers

- Presidents of the United States of America

- Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, 1900 A.D.–present

- France, 1900 A.D.–present

- Low Countries, 1900 A.D.–present

- The United States and Canada, 1900 A.D.–present

- 20th Century A.D.

- Abstract Art

- American Art

- Central Europe

- Color Field

- Concrete Art

- Eastern Europe

- Modern and Contemporary Art

- Oil on Canvas

- Russian Avant-Garde

- Scandinavia

- United States

Artist or Maker

- Albers, Josef

- Atget, Eugène

- Bolotowsky, Ilya

- Booth, Peter

- Braque, Georges

- Diller, Burgoyne

- Glarner, Fritz

- Gropius, Walter

- Hélion, Jean

- Kandinsky, Vasily

- Léger, Fernand

- Moholy-Nagy, László

- Mondrian, Piet

- Picasso, Pablo

- Rodchenko, Alexander

Look Closer

A Brief History of Abstract Art with Turner, Mondrian and More

Take a quick tour through the history of abstract art and take in some unexpected pioneers along the way

Joseph Mallord William Turner Light and Colour (Goethe’s Theory) - the Morning after the Deluge - Moses Writing the Book of Genesis (exhibited 1843) Tate

If you put the word 'abstract' into a thesaurus some of the similar words suggested are: theoretical; conceptual; intangible. Among its many antonyms (or words with opposite meanings) is ‘simple’. The word abstract suggests something vague, difficult, not easily grasped. But abstract art doesn't have to be any of those things. On the contrary, an artist working in an abstract way might want to make something striking and beautiful, whisking us away from the humdrum realities of the everyday. In other words, they might be interested in art for art’s sake, pure and simple. A raft of exhibitions show that far from being a hard to describe movement set apart from the mainstream, abstraction in its various forms has produced some of the most memorable, influential and best loved art of any era.

Wassily Kandinsky is often regarded as the pioneer of European abstract art. Kandinsky claimed, wrongly as it turns out , that he produced the first abstract painting in 1911: ‘back then not one single painter was painting in an abstract style’. But we could argue that the roots of this movement are much deeper (and in fact it seems the Neanderthals where ahead of the game in their cutting of abstract lines into stone). If we look at some of the later works of J.M.W. Turner for example, some of his landscapes could be seen as abstract. What might be traditionally recognisable forms in the hands of another painter are transformed by sublime elements, and overwhelming suggestions of light and scale by Turner.

Piet Mondrian No. VI / Composition No.II (1920) Tate

Let's come to some of the names more usually associated with abstract art. Piet Mondrian , one of the best known early abstract artists, began in more conventional fashion. He painted recognisable scenes and was commercially successful in his homeland of Holland. But when he encountered avant-garde Paris in 1911, and the cubism of Picasso , his work soon underwent, first an evolution, and eventually a radical transformation. He began to use bold primary colours and squares and rectangles in order to create images that he saw as pure. His angled, gridded work is considered by some to be the logical conclusion of painting, abstract or otherwise. Mondrian called his approach neo-plasticism . With neo-plasticism he aimed to achieve the ‘destruction of natural appearance’, finding instead ‘the plastic expression of true reality’.

Kazimir Malevich Black Square 1913 © State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Mondrian had neo-plasticism, Russian artist Kazimir Malevich preferred the term suprematism for his abstract artworks. The term referred to ‘the supremacy of pure artistic feeling’ that he wanted to achieve in his work. Although separated geographically, Mondrian and Malevich were startlingly similar. In 1915 Malevich produced his secular Russian icon, Black Quadrilateral 1915 (more commonly known as Black Square ). Later, writing in his book The Non-Objective World (published in 1927), Malevich said:

In the year 1913, trying desperately to free art from the dead weight of the real world, I took refuge in the form of the square.

Malevich didn’t paint exclusively in black of course but with Black Quadrilateral , he created one of the most iconic abstract artworks.

Let's move from Malevich’s daring use of black, to the intoxicating use of colour by Henri Matisse . Matisse's collage The Snail 1953, seems to display the key qualities of abstract art as defined by by Malevich and Mondrian, suggesting that Matisse was a late convert to the movement. We see bold colours, geometric shapes and no obvious reference to the real world. But, as with much of Matisse’s work , The Snail is in fact inspired by nature. The geometric pattern suggests a snail's shell, going against the ideas of strict abstraction set out by Malevich and Mondrian. The Snail may not be radically abstract, but the technique that Matisse used to make this and similar works is groundbreaking. The Snail is one of Matisse's cut outs – made from shapes cut out of painted paper. With this method of ‘carving into colour’ , Matisse, in a phase of life when the majority of us would be easing into going with the flow, had invented a new medium.

Following the diversion through Matisse, an artist very definitely in tune with abstraction was Marlow Moss . Writing in the Guardian, critic Charles Darwent points out, she was for a time ‘a devoted follower’ of Mondrian’s. Although she is written off by some as an imitator of the father of neo-plasticism, it could be argued that the influence was reciprocal. Her work from the period following her discovery of Mondrian shows his influence, but it was Moss who first introduced twin lines into her gridded compositions in 1931. A year later, Mondrian followed suit, painting Composition with Double Line and Yellow . Largely forgotten in the history of abstract art, Moss’s work, in recent years, is deservedly having something of a renaissance.

Marlow Moss White and Yellow (1935) Tate

We Recommend

Abstract art.

Abstract art is art that does not attempt to represent an accurate depiction of a visual reality but instead uses shapes, colours, forms and gestural marks to achieve its effect

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Piet mondrian, kazimir malevich, henri matisse, marlow moss, suprematism.

Name given by the artist Kazimir Malevich to the abstract art he developed from 1913 characterised by basic geometric forms, such as circles, squares, lines and rectangles, painted in a limited range of colours

Neo-plasticism

Neo-plasticism is a term adopted by the Dutch pioneer of abstract art, Piet Mondrian, for his own type of abstract painting which used only horizontal and vertical lines and primary colours

Malevich exhibition at Tate Modern, opens 16 July 2014

Late Turner – Painting Set Free

The first major exhibition to survey the last works of J.M.W. Turner. Opens 10 September 2014 at Tate Britain.

Mondrian and his Studios

Mondrian and his Studios, is a new exhibition opening 6 June at Tate Liverpool exploring the artist's relationship with architecture and urbanism

COMMENTS

abstract art, painting, sculpture, or graphic art in which the portrayal of things from the visible world plays little or no part. All art consists largely of elements that can be called abstract—elements of form, colour, line, tone, and texture.

The crisis of war and its aftermath are key to understanding the concerns of the Abstract Expressionists. These young artists, troubled by man’s dark side and anxiously aware of human irrationality and vulnerability, wanted to express their concerns in a new art of meaning and substance.

Abstract art is art that does not attempt to represent an accurate depiction of a visual reality but instead uses shapes, colours, forms and gestural marks to achieve its effect. Strictly speaking, the word abstract means to separate or withdraw something from something else.

Abstract art is a non-objective art form that breaks traditional, realistic art styles. It intends to inspire emotion and intangible experience, rather than telling a story or portraying realistic subjects.

This essay explores the realm of abstract art, delving into its origins, evolution, and influence on the broader cultural landscape. Through an examination of key artists, movements, and the enduring relevance of abstraction, we aim to shed light on the captivating world of abstract expression.

In the world of art, abstraction has long been a subject of fascination and debate. Abstract art, characterized by its non-representational forms, shapes, and colors, has a rich history and a profound impact on the art world and beyond. This essay explores the realm of...

Geometric abstraction, through the Cubist process of purifying art of the vestiges of visual reality, focused on the inherent two-dimensional features of painting.

Abstract art uses visual language of shape, form, color and line to create a composition which may exist with a degree of independence from visual references in the world. [1] Abstract art , non-figurative art , non-objective art , and non-representational art are all closely related terms.

Abstract art is art that does not attempt to represent an accurate depiction of a visual reality but instead uses shapes, colours, forms and gestural marks to achieve its effect

Abstract art—also commonly referred to as nonobjective art—is painting, sculpture, or graphic art that does not attempt to represent an accurate depiction of visual reality. By definition, to “abstract” means to “extract or remove” one thing from another.