- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

The four major ethnic divisions among Black South Africans are the Nguni, Sotho, Shangaan-Tsonga and Venda. The Nguni represent nearly two thirds of South Africa's Black population and can be divided into four distinct groups; the Northern and Central Nguni (the Zulu-speaking peoples), the Southern Nguni (the Xhosa-speaking peoples), the Swazi people from Swaziland and adjacent areas and the Ndebele people of the Northern Province and Mpumalanga. Archaeological evidence shows that the Bantu-speaking groups that were the ancestors of the Nguni migrated down from East Africa as early as the eleventh century.

Language, culture and beliefs:

The Xhosa are the second largest cultural group in South Africa, after the Zulu-speaking nation. The Xhosa language (Isixhosa), of which there are variations, is part of the Nguni language group. Xhosa is one of the 11 official languages recognized by the South African Constitution, and in 2006 it was determined that just over 7 million South Africans speak Xhosa as a home language. It is a tonal language, governed by the noun - which dominates the sentence.

Missionaries introduced the Xhosa to Western choral singing. Among the most successful of the Xhosa hymns is the South African national anthem, Nkosi Sikele' iAfrika (God Bless Africa). It was written by a school teacher named Enoch Sontonga in 1897. Xhosa written literature was established in the nineteenth century with the publication of the first Xhosa newspapers, novels, and plays. Early writers included Tiyo Soga, I. Bud-Mbelle, and John Tengo Jabavu .

Stories and legends provide accounts of Xhosa ancestral heroes. According to one oral tradition, the first person on Earth was a great leader called Xhosa. Another tradition stresses the essential unity of the Xhosa-speaking people by proclaiming that all the Xhosa subgroups are descendants of one ancestor, Tshawe. Historians have suggested that Xhosa and Tshawe were probably the first Xhosa kings or paramount (supreme) chiefs.

The Supreme Being among the Xhosa is called uThixo or uQamata . As in the religions of many other Bantu peoples, God is only rarely involved in everyday life. God may be approached through ancestral intermediaries who are honoured through ritual sacrifices. Ancestors commonly make their wishes known to the living in dreams. Xhosa religious practice is distinguished by elaborate and lengthy rituals, initiations, and feasts. Modern rituals typically pertain to matters of illness and psychological well-being.

The Xhosa people have various rites of passage traditions. The first of these occurs after giving birth; a mother is expected to remain secluded in her house for at least ten days. In Xhosa tradition, the afterbirth and umbilical cord were buried or burned to protect the baby from sorcery. At the end of the period of seclusion, a goat was sacrificed. Those who no longer practice the traditional rituals may still invite friends and relatives to a special dinner to mark the end of the mother's seclusion.

Male and female initiation in the form of circumcision is practiced among most Xhosa groups. The Male abakweta (initiates-in-training) live in special huts isolated from villages or towns for several weeks. Like soldiers inducted into the army, they have their heads shaved. They wear a loincloth and a blanket for warmth, and white clay is smeared on their bodies from head to toe. They are expected to observe numerous taboos (prohibitions) and to act deferentially to their adult male leaders. Different stages in the initiation process were marked by the sacrifice of a goat.

The ritual of female circumcision is considerably shorter. The intonjane (girl to be initiated) is secluded for about a week. During this period, there are dances, and ritual sacrifices of animals. The initiate must hide herself from view and observe food restrictions. There is no actual surgical operation.

Although they speak a common language, Xhosa people belong to many loosely organized, but distinct chiefdoms that have their origins in their Nguni ancestors. It is important to question how and why the Nguni speakers were separated into the sub-group known today. The majority of central northern Nguni people became part of the Zulu kingdom, whose language and traditions are very similar to the Xhosa nations - the main difference is that the latter abolished circumcision.

In order to understand the origins of the Xhosa people we must examine the developments of the southern Nguni, who intermarried with Khoikhoi and retained circumcision. For unknown reasons, certain southern Nguni groups began to expand their power some time before 1600. Tshawe founded the Xhosa kingdom by defeating the Cirha and Jwarha groups. His descendants expanded the kingdom by settling in new territory and bringing people living there under the control of the amaTshawe. Generally, the group would take on the name of the chief under whom they had united. There are therefore distinct varieties of the Xhosa language, the most distinct being isiMpondo (isiNdrondroza) . Other dialects include: Thembu, Bomvana, Mpondimise, Rharhabe, Gcaleka, Xesibe, Bhaca, Cele, Hlubi, Ntlangwini, Ngqika, Mfengu (also names of different groups or clans).

Unlike the Zulu and the Ndebele in the north, the position of the king as head of a lineage did not make him an absolute king. The junior chiefs of the various chiefdoms acknowledged and deferred to the paramount chief in matters of ceremony, law, and tribute, but he was not allowed to interfere in their domestic affairs. There was great rivalry among them, and few of these leaders could answer for the actions of even their own councillors. As they could not centralise their power, chiefs were constantly preoccupied with strategies to maintain the loyalties of their followers.

The Cape Nguni of long ago were cattle farmers. They took great care of their cattle because they were a symbol of wealth, status, and respect. Cattle were used to determine the price of a bride, or lobola, and they were the most acceptable offerings to the ancestral spirits. They also kept dogs, goats and later, horses, sheep, pigs and poultry. Their chief crops were millet, maize, kidney beans, pumpkins, and watermelons. By the eighteenth century they were also growing tobacco and hemp.

At this stage isiXhosa was not a written language but there was a rich store of music and oral poetry. Xhosa tradition is rich in creative verbal expression. Intsomi (folktales), proverbs, and isibongo (praise poems) are told in dramatic and creative ways. Folktales relate the adventures of both animal protagonists and human characters. Praise poems traditionally relate the heroic adventures of ancestors or political leaders.

As the Xhosa slowly moved westwards in groups, they destroyed or incorporated the Khoikhoi chiefdoms and San groups, and their language became influenced by Khoi and San words, which contain distinctive 'clicks'.

Europeans who came to stay in South Africa first settled in and around Cape Town. As the years passed, they sought to expand their territory. This expansion was first at the expense of the Khoi and San, but later Xhosa land was taken as well. The Xhosa encountered eastward-moving White pioneers or 'Trek Boers' in the region of the Fish River. The ensuing struggle was not so much a contest between Black and White races as a struggle for water, grazing and living space between two groups of farmers.

Nine Frontier Wars followed between the Xhosa and European settlers, and these wars dominated 19th century South African History. The first frontier war broke out in 1780 and marked the beginning of the Xhosa struggle to preserve their traditional customs and way of life. It was a struggle that was to increase in intensity when the British arrived on the scene.

The Xhosa fought for one hundred years to preserve their independence, heritage and land, and today this area is still referred to by many as Frontier Country.

During the Frontier Wars, hostile chiefs forced the earliest missionaries to abandon their attempts to 'evangelise' them. This situation changed after 1820, when John Brownlee founded a mission on the Tyhume River near Alice, and William Shaw established a chain of Methodist stations throughout the Transkei.

Other denominations followed suit. Education and medical work were to become major contributions of the missions, and today Xhosa cultural traditionalists are likely to belong to independent denominations that combine Christianity with traditional beliefs and practices. In addition to land lost to white annexation, legislation reduced Xhosa political autonomy. Over time, Xhosa people became increasingly impoverished, and had no option but to become migrant labourers. In the late 1990s, Xhosa labourers made up a large percentage of the workers in South Africa's gold mines.

The dawn of apartheid in the 1940s marked more changes for all Black South Africans. In 1953 the South African Government introduced homelands or Bantustans, and two regions 'Transkei and Ciskei' were set aside for Xhosa people. These regions were proclaimed independent countries by the apartheid government. Therefore many Xhosa were denied South African citizenship, and thousands were forcibly relocated to remote areas in Transkei and Ciskei.

The homelands were abolished with the change to democracy in 1994 and South Africa's first democratically elected president was African National Congress (ANC) leader, Nelson Mandela , who is a Xhosa-speaking member of the Thembu people.

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

Africa Is a Country

- Facebook Icon

- Twitter Icon

The Xhosa literary revival

- Use + Republish + Donate

The writer Mphuthumi Ntabeni's new novel explores the deep history of colonialism and resistance in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa.

Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape Photo by Joshua Dixon on Unsplash

When cooped-up critics and writers connect on social media, their conversations often demand more room. Such was the case in my correspondence with Mphuthumi “Mpush” Ntabeni, which migrated to various messenger platforms before finding its stride on email. We read each other’s books; we related them to other books; we grew an unlikely discussion of Catholic conversion narratives from a deep love of South African intellectual history. Talking to Ntabeni, it is anyone’s guess how one body of texts will lead to another. He is a literary wanderer par excellence, and yet he is far from unmoored. Born and raised in Queenstown, in South Africa’s Eastern Cape, he now resides in Cape Town, where he has continued to nurture a far-ranging knowledge of Xhosa history and culture. His first novel, The Broken River Tent , reconstitutes the perspective of a real-life 19th-century chief named Maqoma, of the amaRharhabe branch of amaXhosa who lived west of the Kei River, and were thus among the first African people to encounter white settlers when they arrived on the Cape’s Eastern shores. Ntabeni’s book uses retrospective narration framed by present-day dialogue to offer a Xhosa point of view on that violent encounter, which gave rise to the century-long period of the Xhosa or Cape Frontier Wars (1779-1879) against the British and the Boers.

Published by South Africa’s Blackbird Books imprint in 2018, The Broken River Tent won the debut category of the University of Johannesburg Prize for South African Writing in English the following year. It is not an easy book to slip into: more of a series of conversational and historical collisions than a self-propelling plot, it pairs Maqoma with a contemporary figure named Phila to parse topics ranging from the relevance of psychoanalysis for Africans to the structure and material composition of frontier wagons. One could be forgiven here for recalling fellow South African J.M. Coetzee’s early novels ( In the Heart of the Country , especially), owing not least to Phila’s “hyperanalytical” disposition. Ntabeni’s style, however, is marked not by the stymying force of endless self-reflection, but by the exuberance of a mind eager to unfurl its abundant stores. A single paragraph of the book moves rapidly from Steve Biko to Soren Kierkegaard to the biblical Job, with its dialogue lubricated by cheap whiskey. This is Ntabeni’s approach to fiction in a nutshell: high-octane and expansively informed.

This interview took place on Google Docs between Baltimore and Johannesburg, where Ntabeni has just settled into a four-month writer’s fellowship at the Johannesburg Institute for Advanced Study, housed at the University of Johannesburg. With lockdowns still in place internationally and his work on a third novel beginning in earnest, it seemed like the perfect time to present his ideas to the AIAC readership. What follows has been edited for clarity and flow.

I’m glad we are finally getting around to this, Mpush—your novel was one of the first I read when the pandemic lockdowns started. I know that it’s intended to be part of a trilogy, so I’ll jump right in by asking you what it is that appeals to you about that format for this project. Are you intentionally in dialogue with other famous African trilogies? (Achebe, Mahfouz, and Dangarembga all come to mind, though Okri is perhaps the closest to The Broken River Tent in its merging of spiritual and historical concerns.) Or is there some intrinsic quality of the trilogy that you see your story as making use of?

Well, I’m happy to be here and finally do this with you. Thanks for inviting me. The trilogy was not my original idea. Come to think of it, even writing a book was never my original intention. I was just eager to know about my own history and so I started researching it on my own. I knew very little about it because we had not really been taught it at school or at home. When I thought I had done enough and was even beginning to form my own opinions about it, I started asking myself how I could make other people aware of it, especially the ones directly affected by it, like myself. That is when the idea of the book came to mind. I didn’t want to just translate the material I found in the archives. I wanted to find a way of making that history live, resurrect it if you like, so that non-professional historians like myself would also be interested in it. There was also the issue of gaps in historical facts I found and wished to fill by what I call an “informed imagination,” that is, by inserting psychological and emotional energy into known or unknown historical facts without betraying their true spirit. In that way the genre of historical fiction chose me.

As for why this became a plan for a trilogy in particular, I realized at some point that I had accumulated too much historical data in my research. The task of tackling it through a narrative form became formidable. Then, one cold December day, while we were walking on the High Street of Edinburgh, my wife wanted to feed our daughter who was only a month old then. So, we left the snowy streets and quickly dashed into a restaurant for a meal, to give my wife also a chance to breastfeed the baby. As we sat there, looking through the window, I realized that we were sitting across from one of the places Tiyo Zisani Soga used to stay in while studying at the University of Edinburgh. ( Note to readers: Tiyo Soga was a 19th-century South African intellectual best remembered for translating the bible and John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress into isiXhosa ). Then the format of how to handle my research material came as a bolt of lightning to me. I would need to divide it into three thematic units: war, religion, and politics. The protagonist for the war section became obvious to me when I recalled that out of nine wars the amaXhosa fought with the British colonial government over 100 years, at least four of them were led by Maqoma , and he was physically present in five. This is why I used his biographical facts as the skeleton of my first book. Soga, the first Xhosa person to be educated in what we call Western education as a reverend, was also the obvious candidate for the religious section, which I’m currently busy with. And S.E.K Mqhayi (1875-1945), the poet, essayist, biographer, and newspaper editor during the foundations of political resistance that led to the foundation of the ANC, also became an obvious choice for me. I wish to call the trilogy “The River People,” and The Broken River Tent is its first installment.

My writing influences are myriad. In fact, I still consider myself an avid reader who acquired an opinion about the events of our history more than I consider myself to be a writer. I like that it is mostly my readers who make me aware of the literary influences on my writing, more than I do myself. I recall being surprised when a brilliant interviewer asked me if I considered The Broken River Tent to be magic realism. I honestly had never thought of it that way, but as I began doing so I saw her point, especially in the section when Maqoma gets a visit from Nxele in Robben Island. I suspect it is also the reason why you see Ben Okri’s influences on my writing, perhaps more with The Famished Road than any other of his works. The Chinua Achebe reference is understandable since we both write about the impact of colonialism on native culture and history. I also learnt a wonderful trick from him of titling books with lines from popular poets.

I want to get back to Soga, so hold that thought. First, though, it also strikes me that you try, in The Broken River Tent , to approximate the cadences and “feel” of Xhosa speech as well as including passages of isiXhosa. This deliberate Africanization of English is often cited as one of Achebe’s key postcolonial innovations. Can you say a bit more about what this technique entailed, for you?

I guess no one can bring forth an African voice in literature without adopting the African traditional style of speaking in proverbs and all. I don’t know how Achebe wrote his characters in his head, but I was deliberate in hearing Maqoma’s voice in Xhosa in mine, before translating it into English. This is why his English is different to that of other people in the novel, like Phila who has been educated in Western ways. I wanted Maqoma’s voice to have raw Xhosa intonations. I felt lucky in the sense that Xhosa is a singing language, so I wanted to translate that for non-Xhosa speakers so that they might be able to understand how the language, like most ancient and classical languages, sings. My sister says I Xhosalized English, and I find this phrase endearing. I was also happy that someone at least noticed the effort I tried to make with Maqoma’s voice. Much of it is acquired from a Xhosa imbongi style of praise singing. Mqhayi has been very helpful in my learning to acquire that voice. I also learn a lot from the Gaelic ancient languages, like Irish shamans and Scottish Picts, my other learning obsessions. I find a lot of commonality in how they infuse English with traits of their traditional languages, which is what gives them distinct and unique ways of speaking English mixed with their mother tongues. I’m afraid I’ll never stop bragging about the richness of the Xhosa language if you don’t stop me…

Brag away! You fill me with regret that I didn’t stick with Xhosa beyond an intro course. And I think that you are onto something important, here, about the significance of your role as a specifically Xhosa novelist to the fractious tradition of South African literature broadly. Black South African writing is most often associated with the urban, the cosmopolitan, and the “modern,” from the trope of “Jim Comes to Joburg” in the mid-20th-century; through the “Drum generation” as it flourished in the 1960s; to the Soweto novels of the 1970s and 1980s; and right up to post-apartheid figures like Phaswane Mpe and K. Sello Duiker . And yet, as you suggest with your reference to Tiyo Soga, there is a much longer and less widely read history of culturally differentiated South African writing; it isn’t simply “English,” “Afrikaans,” and “Black,” as one often hears. I am thinking even of A.C. Jordan here, whose 1940 novel Wrath of the Ancestors , as you well know, deals not so much with overt questions of racial or national identity but with intra-cultural dynamics. The historical tensions within “Xhosaness” are also something you explore in The Broken River Tent . My question, then, is this: has South African literature reached a point where there is room for more prominent literary experimentation in a wider range of constituent traditions? What, in other words, is the relationship between Mpush Ntabeni the Xhosa novelist and Mpush Ntabeni the South African one?

This is an interesting question that I doubt I’ll be able to answer, but I’m going to give it a go. I think all writing cultures that write in English, not as a mother tongue, or perhaps it is better to say those whose background is not necessarily Anglo-Saxon, have a love/hate relationship with the language. Though they understand its usefulness as a lingua franca, they tug on the leash of its dominance and hegemony. They also sometimes find it to be an insufficient means to express their own philological roots. I am not even talking about the language politics here, which Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o argues convincingly even though proper solutions still elude him also. I am talking about the sheer frustration of someone who has been raised and nurtured in say, German or Xhosa, with a much more comprehensive variety of words and phrases to transmit the spirit of their thoughts precisely and succinctly in their own language, and which often are not translatable to English. ( Note to readers: The character of Phila in TBRT was educated in South Africa and Germany .) When writing The Broken River Tent , whenever I encountered that challenge, I chose to use the Xhosa or German phrase alongside what I regarded as a weak explanation of its meaning in English. I don’t see why I should rob words/phrases of the richness of their meaning just to serve the monolinguist.

To answer your question properly, though, the genius of the English language, why it became so popular, I think, is because it is adaptable. It gleans words from various languages to enrich its vocabulary. There’s no reason why that adaptability should only be limited to Germanic, Frank, and Latin languages when English is also spoken in Africa and Asia. South African literature therefore has no choice but to adapt also, it must grow its African roots, and those cannot only be limited to Afrikaans when this country has 11 official languages. Of course, the attitude of some gatekeepers within the publishing industry is not completely convinced about this. They still come with tendencies of recognizing only occidental trends as seeds of progress. But they’ll be compelled by the ruthless hand of necessity.

My going back to the roots of our literature, I mean beyond the so-called Drum Renaissance, was necessitated by my handling of our older historical material. I guess you can say it was serendipitous in that sense. But it was deliberate also. I feel the writings of the Drum generation are too American, black US American to be precise. I hold nothing against them doing what they needed to do with the tools at their disposal then. In fact, I dream of writing a literary biography of Bloke Modisane one day as my excuse to interrogate the zeitgeist of that era, but that’s a topic for another time. Then our cultural issues developed into political ones for the necessary expediency of our freedom. I think it incumbent on us now to revisit our unresolved cultural issues for the sake of mending our identity, especially the crucial parts that were vandalized by colonialism. Your Jordans and your Jolobes interest and influence me more because they were dramatizing Xhosa oral history. To date it is very difficult to distinguish between their writings and that of J.H. Soga, who wrote non-fiction books like The South-Eastern Bantu . J.J.R Jolobe and your Mqhayi dramatize that history in their books. Not only that, they also close the gaps by what I have called their informed imagination. Hence their narrative tonality is closer to the oral history and recitations by imbongi of the amaXhosa because they wrote closer to the transitional period when all that was changing. This is why at this moment of my writing they interest me more than the Drum generation. I find in them a certain Xhosa literary tradition that got truncated into the Americanized cosmopolitanism of the Drum era when our writers moved to the big cities. I wish to trace and follow that tradition. By the way, I was named by my paternal grandpa, who taught himself how to read through Jordan’s book. Hence, I am called Mphuthumi, after the wise counselor of the king in Ingqumbo Yeminyanya .

This is a fascinating response, especially seeing as there are such tricky questions circulating right now about the uses and limitations of a US-originating racial vocabulary in articulating social justice claims within African contexts. I’m quite drawn to your idea of returning through reading and writing to a truncated but robust intranational tradition, veering off course from the more typical emphasis on South Africa’s international visibility during the apartheid years. It suggests a way of getting some intellectual distance from what can feel like overwhelmingly urgent political and cultural entanglements, at the same time as it speaks directly to some of their most prominent concerns: the decolonization of knowledge, black cultural reclamation, and language justice. In this way, The Broken River Tent is quintessential of the historical novel genre, reconstituting the past to advance crucial claims on the present. It also partakes in an ongoing “boom” of African historical fiction, appearing within the same few years as Fred Khumalo’s Dancing the Death Drill (2017), Ayesha Harrunah Atta’s The Hundred Wells of Salaga (2018), and Petina Gappah’s Out of Darkness, Shining Light (2019), to name just a few examples. The Broken River Tent , however, does something bold and unusual: it introduces Maqoma as a character in the present, while leaving what we might call his “historicity” intact (his speech, frames of reference, etc.). What motivated this choice, and how would you describe your particular (and wonderfully peculiar) re-engineering of the historical novel?

In the first draft of my manuscript Maqoma was the one telling the story alone. It felt too monologic and like an excuse to retell historical events that affected his life. It was missing the element of clear impact on current events and the status quo of our history. I needed a way to visibly link our present status quo as consequences of those historical events. That is how Phila was born, a character that would not only ask questions to suss out what we need to know from history, but that would also provide a historical tour of the present-day situation to Maqoma and his past era. I am sure you’re aware of this trick from Dante, how he used the ancient poet, Virgil, as his tour guide to his imagined life after death. Because I wanted to talk about this life, I re-tooled that trick a little and made it so that it is Maqoma who comes back as an ancestor to help Phila in this life.

The idea of ancestors as guides for the living is prominent in Xhosa spirituality. Our culture is impatient with numinous things that only speculate about life after death with no bearing on the present situation. I’ve since been pleased to discover that Diana Gabaldon has done a similar thing on her Scottish Outlander historical novels that have been turned into a popular TV series in the UK. I am also aware of the African historical novels you mention though I wanted to introduce the element of what others are now calling magic realism, most popular in Latin American literature of the likes of Gabriel García Márquez. Somehow, he definitely influenced me because I had a period in my life when I was obsessed with his writings, which I had forgotten.

My aim was to also expose the truth of rootlessness even on those who are educated if they’ve no solid sense of their own identity. You know the proverbial saying about a tree without roots. The presence of Maqoma in our times was to give Phila a cultural background and deeper sense of his own identity as a means to assuage his weltschmerz , world-weariness. So, in a way, the book is some sort of bildungsroman for Phila whose character starts out slightly emotionally stunted, something I hope is clear in how he relates to his girlfriend Nandi.

I so admire the easy breadth of your references and reading, which also comes through in the novel itself. This feels like an important reminder that there is no need to choose between centering African traditions and richly engaging with others, Western or not. I want to return, though, to this matter of “roots” and “rootlessness,” which you’ve referenced a few times here. There is a certain skepticism, in your work, of secular and cosmopolitan ways of viewing the world, and particularly of secular modernity’s propensity to find meaning primarily in the self. (It’s no coincidence that Nandi is a psychologist.) While there is, of course, a long record of “troubling” modernity in African writing, you have also been open about your debt to the Catholic intellectual tradition. We might, then, go further afield and think about The Broken River Tent alongside some classic Catholic texts and writers for whom rootlessness was also a paramount concern—G.K. Chesterton, Evelyn Waugh, even Graham Greene in his attempts to work through the mechanics of redemption in a British colonial setting. How has this part of your life informed your fictional practice, in ways that might be surprising to some readers?

Thanks for the complements. I get worried when people, more influenced by so-called “cancel culture,” think the process of, say, decolonizing ourselves means that we need to disregard all Western thinking in order to allow African thought to emerge. As if African thought and vision is too weak to stand its own ground against other world streams of thought. In fact, as a staunch humanist, I strongly believe that global thought, Goethe’s world literature if you like, awaits African thought traditions to be properly assimilated to it.

The human condition is my preoccupation. I have also invested a lot of learning in classical literature. And yes, there was a time classical literature was used as a weapon to propagate imperialism, patriarchy and all that rubbish whose aim was to put a white male on the pedestal to be worshipped and admired. But there’s so much more in it there that speaks to the human condition, including the African condition, that it seems to me a disservice to just throw its baby out with the dirty water of occidental historic faults. So much of it also can be used, and is being used, to counteract all of its wrongs. Hence you see this exciting bloom of the retelling of Homeric stories in particular from the feminine point of view by the likes of Madeline Miller, Pat Barker, and Natalie Heyns, among others. You earlier mentioned Petina Gappah’s Out of Darkness, Shining Light , and I am sure you noticed that she has also begun to turn toward ancient classical themes and language to depict the African human condition. Chigozie Obioma, in The Orchestra of Minorities does the same. You shall notice in my next novel, The Wanderers [to be published in April/May] , that I delve into this a little deeper also, to depict the notion of the absurdity of the human condition, which though popularized by Albert Camus, and elaborated through thinkers like Søren Kierkegaard (another strong influence in my thinking), goes back to the classical era of literature and is a Socratic imperative. Camus was greatly influenced by the church fathers, St Augustine in particular. My thinking is also greatly influenced by Augustine. In fact, my conversion to Catholicism has something to do with my immersion into history. Perhaps the major difference between Camus and me is that the absurdity of the human condition has never managed to extinguish the flame of hope within me, not yet anyway. In fact, I define hope as that mysterious and incomprehensible energy that remains in a person when human reason has been defeated by the absurdity of their human condition. Chesterton, of course, is necessary in religious thinking in particular, so that one doesn’t take oneself too seriously to their detriment.

You formulate this belief in decolonization as cultural capaciousness so passionately, and it calls to mind the famous quote by the Roman playwright Terence, himself an African and freed slave: “I am human, and I think nothing human is alien to me.” It is, of course, easy enough to cite this in a pat and cliche way, as a conversation-ending shortcut to universalism rather than as a reminder of how much work it takes for a writer to approach something like what you call “the human condition.” I take you to be suggesting that African writers, far from being peripheral to humanism, may in fact have a particular claim to its fulfillment. The title of your forthcoming novel, The Wanderers, is resonant here as well, because it is also the title of a sprawling and ambitious 1971 novel by Es’kia Mphahlele. In this light, what goals for African writing and critical thought broadly do you see your work as advancing? And, more specifically, where do you feel most “at home” within the current South African and continental publishing landscape?

I am extremely happy you picked up my association with the quote of Terence, because I had it exactly in mind when I mentioned my preoccupation with the human condition. And yes, I strongly believe the humanistic thread of world thought will only be fulfilled by something whose seed is the African life attitude of ubuntu . And yes, there are deliberate parallels on my forthcoming work with that of the late professor Es’kia Mphahlele in that they’re both exile novels, with mine in Tanzania whereas his was in Nigeria. But far be it to me to dictate where my work will eventually end up within African writing. That will depend on my readers and the generation that follows us if we’re lucky enough to be of any interest to them. For now, I feel my writing experience is drawing me towards the fractured narratives that are part of our heritage we dropped during the early parts of the 20th century and before. I feel part of our true literary roots are left stranded there and calling to be assimilated to our contemporary thoughts.

Within the current trend of continental publishing it would seem as if Nigeria is the continental trend setter for African literature. There might be many things informing this, like the fact that it is the most populated country on the continent, and so has more people in the diaspora also. And the migrant story is the flavour of the day in the global literary market. But I like what Ghana writers, who by the way you introduced me to, like Nana Oforiatta Ayim, are doing in books such as her debut The God Child , infusing philosophical and psychological substance in their writing that gives its literature more gravitas, rather than merely writing about big social issues without treating them with the deeper thinking they deserve. The charge I am making here is that made by James Baldwin against American writers, “… that they do not describe society, and have no interest in it. They only describe individuals in opposition to it, or isolated from it.” Most of our African migrant writers, especially those writing from the US, seem to have caught this disease. Like Baldwin I am beginning to find fault with it.

As for South Africa, the only way for us to move beyond the schizophrenic bipolar nature of our literary identity is by respecting what came before. It is imperative that we honestly deal with our past in order to gain our roots, a true sense of identity we can successfully depict as our assimilated literature tradition. This separate literary development of the Afrikaans of Afrikaners doing its own things, and that of colored writers doing another, or the black Africans doing theirs, though good for diversity, has not provided us with an assimilated national literary voice also, hence I call it schizophrenic. The problem is we’ve not yet distilled our identities deeply enough to go beyond politics into the understanding of not only our commonalities but our indispensability to each other also. And going to our historical foundations helps us rediscover this.

While I am tempted to go off on a tangent about Ghanaian writing, here, this seems like an ideal and provocative place to stop and let readers process the many points you’ve raised about how literary traditions can and should enrich each other, about the primacy of African histories for seeing that such exchange happens justly, and about historical legacies both recent and long past. I am sure that many readers will also want to read these issues’ fuller exposition in The Broken River Tent ! I, for one, am grateful to you for lending me your mind across these hours on other sides of the earth, and eagerly await publication of The Wanderers . Enkosi, Mpush.

Wonderful, Jeanne. Thanks for taking time to read The Broken River Tent and talk to me about it. Now that I am busy with my third manuscript, I feel The Broken River Tent is still the book that gave me the most trouble with research and writing process. It tested not only my intellectual but psychological strength also. I was not ready to encounter the rawness of the archives. It took some getting used to working with the material objectively, disregarding the anger it provoked in me as a Xhosa person, because hardly any of these historical sources ever try to see things from the perspective of the amaXhosa. That is what inspired me to write the book, that wanting to tell things, for once, from our perspective.

Further Reading

Letters of resistance

- Athambile Masola

An anthology series, Women Writing Africa , restores women’s writing to the public archive.

A Revolution in Many Tongues

- Mukoma wa Ngugi

There is not a single journal devoted to literary criticism in an African language or any writer residencies that encourage writing in African languages.

African poets for Africa

Badilisha is rare: an African project funded by a mix of government and private art donors, facilitating media access to African poets.

The most interesting bits

- Orlando Reade

Kaleidoscope magazine has done an “Africa” issue; it wants to walk a fine line between identity politics and universalism.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- B-BBEE Level 1

- OUP WORLDWIDE

- RESOURCE HUB

- HOW TO ORDER

- PRICE LISTS

- LOGIN/REGISTER

- SHOPPING CART

- COMPETITIONS

- Description

U-Unambitheko yincwadi equlethe izincoko ezichaphazela imiba ngemiba kubomi esibuphilayo kuwo lo mhlaba umagad ahlabayo. Ingakumbi kula maxesha sikuwo, zininzi izinto ezifika ziphithikeze ingqondo yomntu oNtsunda atsho angazazi nokuba ubheka kweliphi na icala. Zingena kweso sithuba ke izincoko kuba zona ziyayixhokonxa ingqondo, zimenze obelele abuke ebuthongweni, zimenze ohleliyo abe ngathi uyazikisa ukucinga. Le ncwadi ilikhwelo kumZi oNtsundu. Vukani! A collection of contemporary essays that explore the pros and cons of common issues (eg. the role of TV, corporal punishment) and further encourage debate and reflection on these topics.

The specification in this catalogue, including without limitation price, format, extent, number of illustrations, and month of publication, was as accurate as possible at the time the catalogue was compiled. Due to contractual restrictions, we reserve the right not to supply certain territories.

Global site navigation

- Celebrity biographies

- TV-shows and movies

- Quotes - messages - wishes

- Business tips

- Bizarre facts

- Celebrities

- Family and Relationships

- Women Empowerment

- South Africa

- Cars and Tech

All about Xhosa culture: cuisine, traditions, history, and attire

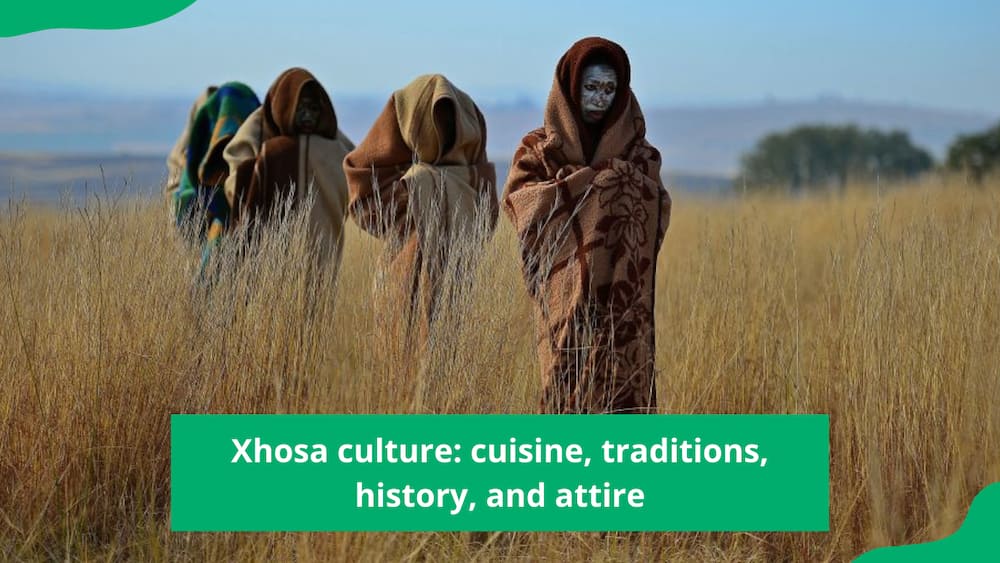

The Xhosa are often called the "Red Blanket People" because red and orange are the primary colors for their traditional attire. This tribe is part of the four Nguni (nations) tribes in South Africa. Like numerous other African communities, the Xhosa culture has rich and well-laid-out traditions, beliefs, rites, rituals, and ways of life. This article shares the most important aspects of the Xhosa culture, from religious beliefs to wedding, birth, circumcision, and death rites. It also touches on aspects about their homesteads, food, folklore, songs, and art.

The Xhosa are a Bantu-speaking tribe and the second-largest tribe in South Africa. These people are predominantly found in the Eastern and Western Cape provinces. The Xhosas call their language isiXhosa, but the world calls it Xhosa in English. Discover the most interesting facts about the Xhosa culture below.

The Xhosa culture and traditions

The Xhosa tribe is further divided into various subtribes, mainly the Mpondomise, Mfengu, and Thembu. They also have smaller subtribes like the Bhaca, Bomvana, Fingo, Nhlangwini, and Xesibe. Read the most intriguing truths about Xhosa origins and their culture below:

White man embraces Xhosa tradition with stylish attire in viral TikTok video, wins praise online

Xhosa culture: clothing and food

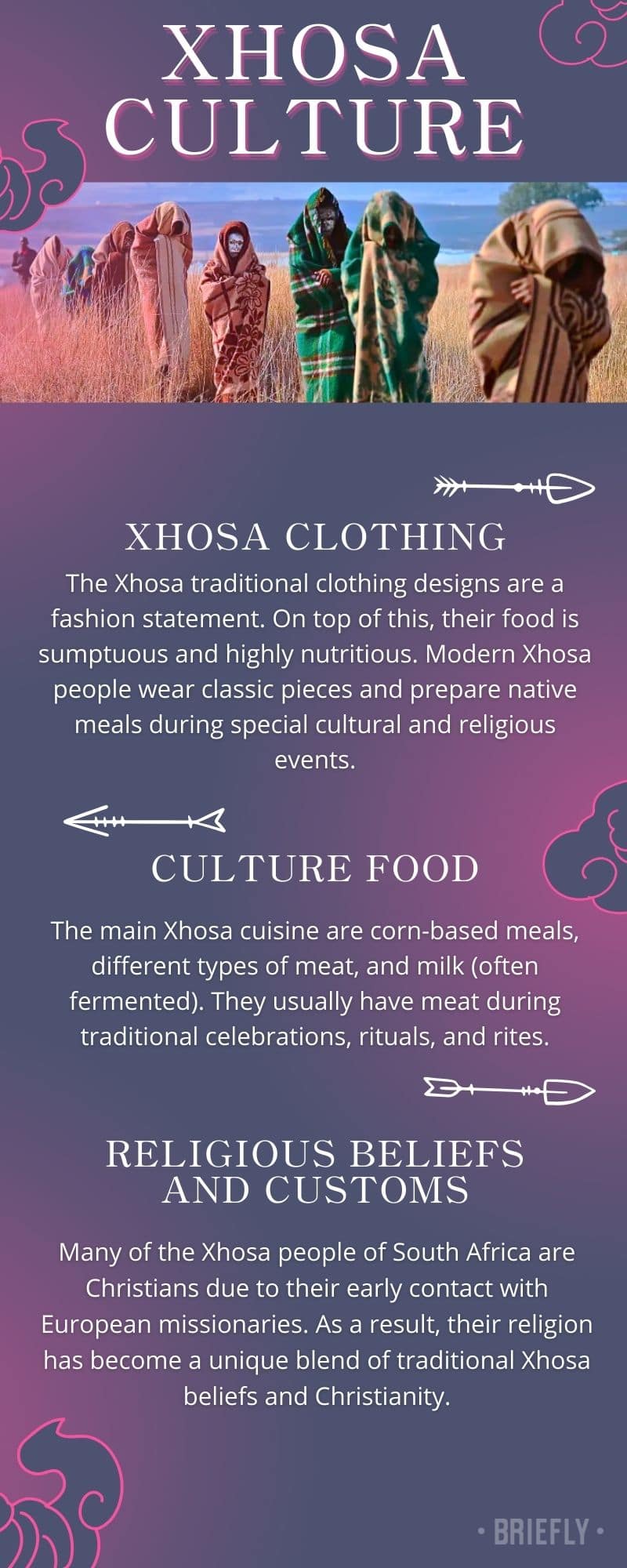

The Xhosa traditional clothing designs are a fashion statement. On top of this, their food is sumptuous and highly nutritious. Modern Xhosa people wear classic pieces and prepare native meals during special cultural and religious events.

What are some foods of the Xhosa culture?

The main Xhosa cuisine are corn-based meals, different types of meat, and milk (often fermented). They usually have meat during traditional celebrations, rituals, and rites. Some popular Xhosa meat-based dishes are inyama yebhokwe , umleqwa , inyama yegusha , and inyama yenkomo .

Other popular Xhosa dishes are umngqusho (a savory combination of corn, beans, and spices), umqa (stiff maize meal porridge served with curried cabbage or spinach), and umxhaxha (a combination of pumpkin and corn), and umkhuphu (maize meal and beans).

Xhosa has numerous rules about food . For example, the liver is for young men, while the inguba (the meat between the intestines and the stomach wall) is reserved for older men. Men do not drink milk from a village where they might get wives, women do not eat eggs, and newly married women are not allowed to eat some types of meat.

Mzansi Magic's Kokota cast with images, plot summary, full story, trailer

What is the Xhosa traditional wear?

Traditional Xhosa attire are usually in brilliant colors like red, white, orange, or yellow. Married women wear long aprons over their dresses. The isikhakha (dress) is decorated with black bias binding at the hem and neck. The women complete the look with a cloak made from the same material, head scarves, breaded jewelry, and a sling bag called inxili .

A Xhosa head scarf for a woman is made of two or three materials of colors representing the different areas she comes from. Meanwhile, their beaded jewelry are primarily red, blue, dark blue, white, and yellow.

Most Xhosa traditional attire are cotton-woven and come in numerous unique styles and patterns. The men wear wrap-around skirts running from the waist to the feet. These are accompanied by a long scarf thrown over one shoulder, which can serve as a cloak when it gets cold.

Video of Venda wedding takes TikTok by storm with cultural spectacle and traditional outfits

Additionally, the men carry sticks given to them during their circumcision ceremonies. They can use these sticks to defend themselves and their families. Xhosa men learn how to fight with sticks growing up. Boys practice this fight while herding cattle in the veld (pastures).

Xhosa religious beliefs and customs

Today, many of the Xhosa people of South Africa are Christians due to their early contact with European missionaries. As a result, their religion has become a unique blend of traditional Xhosa beliefs and Christianity.

Who is the God of Xhosa?

The supreme being in Xhosa is called Mdali , Thixo , or Qamata , and they communicate with him through ancestral intermediaries. The primary role of the Xhosa ancestral intermediaries is to perform rituals and sacrifices, which are believed to help the people communicate with the spirits of their ancestors.

Census 2022 shows increase of Shona speakers in Limpopo linked to Zimbabwean migrants

The ancestral spirits, in turn, act as mediators between the people and the deity. Xhosa people believe that Qamatha , the creator of all things, controls all things, and without the rules he laid down for humans, there would be confusion, madness, and uncertainty on Earth.

Although most Xhosa-speaking people generally accept Christianity, some of the tribes' descendants practice both Christianity and traditions.

The Xhosa marriage ceremony

Umtshato (marriage ceremony) is among Xhosa culture's most significant traditional events. The ceremony begins with the ukuzena process, which can be done in three ways.

The marriage proposal

The couple can do the ukuzibonela , whereby the man proposes to a woman before informing his family to accompany him to meet her people.

Alternatively, the girl's parents can practice ukholela , whereby they identify a man (a potential spouse for their daughter). Afterward, they send a family member (uncle or elder brother) to plant a spear in his parent's home early in the morning.

SABC2's Married Our Way wedding show: What can you expect?

A family that wakes up to a spear planted in their home asks around to know where it came from. If they accept the proposal, they will return the spear by planting it in the home of the girl's parents. If they reject the proposal, they will keep the spear.

The third alternative is the ukuthwala , whereby the couple marry without consent from their parents. This usually happens when they fear opposition from the lady's family. After a secret courtship, they agree on the day and time of eloping.

The man sneaks into the woman's home in the evening and takes her to his home, where his parents will be waiting for introductions. The following morning, the man's family will visit the girl's parents to express their intentions to have her as a daughter-in-law. The girl's parents accept the proposal and request the man to pay a fine for eloping with their daughter.

What happened to Big Nuz members? Here is everything we know

The fourth option is the ukufilisha , whereby the man speaks to the girl's parents. It is up to the parents to reject or accept his proposal, and the bride-to-be's opinion does not matter.

The marriage proposal acceptance letter

After both families are aware of a potential marriage between their children, the man's family writes a proposal letter to the woman's family. The latter also responds with a letter. Two men from the woman's home deliver it to the man's parents. This traditional letter acceptance process is called ukuvuma .

The lobola ceremony

The woman's family informs the man's family of the date for the lobola ceremony through the acceptance letter. The groom's family pays ikhazi (dowry or bride price), which is usually money or cattle (ten to twelve cows). The dowry must be paid a few days or months before the wedding, and the man can add gifts like alcohol.

Xhosa woman celebrates traditional wedding in stunning video, over 400 000 peeps in love

The amount of cash and the number of cattle a man pays depends on the agreement between his family and the bride's family. Additionally, if the marriage proposal was initiated by ukufilisha or ukholela , the girl's father or uncle can help the groom by paying part of the dowry.

The lobola ceremony has several stages. The first payment, an imvulamlomo , is a small token or fee the groom pays the bride's family before his family can negotiate ikhazi (dowry or bride price) with them.

The second token, isazimzi, demonstrates the seriousness of the groom's family. It assures the woman's family that the groom's people specifically selected that girl's home among all the other homes in the village.

After the negotiations and agreeing on the dowry size, the bride's family performs isivumo . They slaughter a cow to feed the groom's family. It signifies the two families accept to have a relationship through their children's marriage.

e.tv's Smoke & Mirrors: cast, plot summary, trailer (with images)

The ikhazi is the main dowry, and two special cows should be set apart from all the cows the man pays. One is an ubuso bentombi (a cow for the bride's face), and the other is an inkomo yomthuko (a cow for the bride's mother).

The man pays intlawulo (a sacred cow or goat) if he has a child or children with the bride. It must be killed, cooked, and feasted on by both families on the same day it is brought to the woman's home. This cow is a fine the bride's family imposes on the man. Since having children out of wedlock is frowned upon, the ritual cleanses the name of the girl's family and also restores their dignity.

The Xhosa wedding ceremony

The Xhosa wedding ceremony takes at least three days. After the lobola ceremony, people escort the bride to the groom's home for uduli (bridal party). The party happens on the eve of the wedding day. The man's family gives the bride and her guests a special hut and gifts them a goat called umathulanthabeni .

e.tv's Nikiwe: cast, plot summary, full story, trailer, episodes

The bride's people pay a fine called isiphembamlilo for the groom's family to give them a lighter to make a fire for cooking or roasting the goat meat.

The following day, they will pay the man's family a cow called inkomo yobulunga as blessings to the bride as she moves into her new home. A rope is made from the skin of the inkomo yobulunga and tied around the bride and her children (if she has any) to protect them from evil.

Later in the evening, the man's family will sacrifice a cow and offer the bride's family a leg, inxaxheba , as a token of appreciation for the new family ties. After that, the young maidens from the bride's family will help her light her first fire, which she will use when they are gone.

The following day will be for umdundo or umtshatso (the actual wedding). The man wears traditional outfits, while the bride wears her isishweshwe skirt and apron, ikhetshemiya (headcloth), imibhaco (beaded necklace and bracelets), and covers herself in ingcawa (a blanket).

Exclusive: Somizi, Skhumba, and JSomething to be investigators on 'The Masked Singer SA'

The bride's people sing and dance while taking her to enkundleni (an assembly of the groom's family). Usually, the men are the lead singers, while the women respond to the songs.

When they get to the forum, two men from the bride's side uncover her to reveal her face. In response, male elders from the groom's side welcome and counsel her on how to conduct herself as a married woman. After that, female elders are given the chance to offer her more marital advice. This guiding and counseling process is called ukuyala .

After the ukuyala , people feast and drink umqombothi (traditional liquor) while singing and dancing ukuxhentsa (traditional dance). The families then gather again and give the bride a spear to throw as a sign she has been accepted into the new family. If the spear falls on the ground, it signifies her marriage will fail, but if it does not, the marriage will last.

Zulu, Xhosa, Tswana and 2 more traditional wedding dresses Mzansi loved, South African expert explains cost, fabrics and designs

The morning after the umdundo , the groom's family gives the bride's family blankets and other gifts. Meanwhile, the woman's family returns home, leaving behind an inkubabulongwe (a young girl) to help the makoti (newlywed woman) with chores like cooking, fetching firewood and water, and cleaning the hut.

In the evening, the groom's family will dress the new wife in umbhaco or umajelumane (a blue makoti attire), tie a small blanket around the waist, and cover her head with iqhiya (a black headscarf). She will sit on a grass-woven mat and eat goat meat and sour milk. The woman will use the mat wherever she goes instead of sitting in a chair.

For about three or four months after the wedding, she will undergo ukuhlonipha to learn how to do house chores, dress decently, address elders, and so on.

Top trees in South Africa: A-Z exhaustive list with images

Xhosa birth rituals

Xhosa people do not pick children's names before birth. They wait till the child is born to know its gender, what it looks like, and how people feel so that they can give it an appropriate name.

The mother and child's seclusion period

A birthing mother is called umdlezana and is aided by her grandmother or midwives (women in the community who have experience helping fellow women deliver babies).

She gives birth in her rondavel , which is a circular dark room made with mud walls and a conical grass-thatched roof. The mother and baby spend ten days indoors, inside the rondavel , to allow the baby's umbilical cord to fall off.

During that time, the grandmother or community midwives mix ash, sugar, and a plant called umtuma , then rub the paste on the baby's umbilical cord. The mixture aids the drying process, which, in turn, makes the placenta fall off faster.

Who is Konka Soweto owner? Everything to know about the restaurant and club

Once the placenta has fallen off, close female family members and a few women from the community gather in the rondavel to perform the sifudu ritual . They burn aromatic leaves from the sifudu tree and float the baby (upside-down) over its pungent smoke three times. The smoke makes the baby cough, and sometimes, scream severely.

The women return the baby to the mother, who then passes it under her left and right knees. The Xhosa people believe the sifudu ceremony strengthens the baby's spirit and protects it from future evil.

Afterward, they women will wash and smear the baby with ingceke , a white chalk made of grounded mtomboti wood. Its sweet smell stays on the baby for weeks.

The mother breastfeeds the baby before the women bury or burn the inkaba (placenta). The ritual protects the baby from sorcery and bonds it with its clan, ancestral land, and the spiritual ancestral world . In the future, when the baby is an adult, he/she can visit where their inkaba was buried to communicate with their ancestors.

Dudu Busani-Dube's books list in order: A must-read for booklovers

What happens after the mother and child's seclusion period?

The family sacrifices a goat and invites friends and relatives to the imbeleko feast. The ceremony marks the end of the mother's ten-day period of solitude. Those who do not practice traditional Xhosa birth rituals can still be invited.

The family treats the goat's skin as a sacred item. They dry and preserve it for the new clan member, the baby, to sleep on in the future in times of trouble and connect with the ancestors.

The Xhosa naming ceremony

The child is named during the imbeleko ceremony. The Xhosa clan's “Praise-Singer” summons the ancestors vocally with praises. The singer chants qualities the family would love the ancestors to below upon the baby so that it grows into a responsible clan member.

After that, the baby is named after its father (surname) and one of its ancestors (first name). Also, it can be given names that signify seasons (rainy season, planting time, harvesting time, or the famine season) or the family's wishes for the baby, such as Sibabalwe (the blessed one). All traditional Xhosa names have beautiful meanings.

BET Redemption cast (with images), trailer, plot summary, full story, episodes

Xhosa circumcision rituals

The isiXhosa culture circumcises men and women. The abakweta (male initiates-in-training) live in bhoma (secluded huts) away from the village. The boys wear loincloths, cover themselves in blankets for warmth, and smear white clay on their bodies from head to toe.

The seclusion lasts about a month and is in two phases. During the first seven days after an ingcibi (traditional surgeon surgically has removed their foreskins, the initiates are confined to the huts and fed on certain foods. Some foods and water may be restricted. The initiates are not allowed to cry or show signs of pain as this would be considered shameful and an indication of weakness.

The second phase lasts two to three weeks, and an ikhankatha (traditional attendant) looks after them. The seclusion period ends with a goat sacrifice and the boys washing themselves. Also, they burn down the huts and the initiates' possessions, including their clothing, to symbolize a new beginning.

Ndebele clan names, best baby names and surnames: Exhaustive list

Each initiate receives an ikrwala (a new blanket), representing he is a new man or amakrwala . What's more, the initiates dress formally for some time after the rite.

The female circumcision ritual is shorter than that of their male counterparts. The intonjane (female initiates-in-training) stay away for a week, and no surgical operation is performed on their bodies.

Xhosa death and burial rituals

The Xhosa have well-defined burial rituals and practices . The nuclear family announces the death of their loved one to the extended family. The process is called umbiko . After that, relatives gathers to prepare for the burial.

The family conducts the indlu enkulu (or emptying the bedroom ritual) to honor the deceased and create space for mourners to view the body. One of the family elders guards the body throughout the days the burial preparations are going on. These days, people take the bodies to the mortuary.

Top 20 interesting facts about South Africa you ought to know | Details for travellers

The widow is not expected to talk too much. Some of the aunts sit with her in the house on grass mats and cover themselves with blankets while the other family members continue with the ukuvela (burial preparations).

Visitors and people trooping into the home to offer their condolences are allowed to hold imithandazo (prayers) for the family. Meanwhile, the community gravediggers dig and prepare grave. It takes about four days for them to complete the work and the family cooks for them daily as a sign of appreciation.

When the family brings the corpse home from the mortuary, they practice ukuvulwa kwebhokisi . This means a designated person speaks to the deceased before they leave the morgue and when they arrive home. Neighbors, relatives, and anyone can view the body in the coffin when it gets home. Xhosa people call this ukubona umfi .

How to get ready for Christmas in South Africa: lunch ideas, trees, crackers, table decor

Xhosa funerals ( umngcwabo ) do not come with an invitation. So, anyone can attend. The family provided a bull and umngqusho (corn and beans) to feed the mourners on the burial day.

A day after, women wash the deceased’s belongings to wash away death and family members also shave their hair, indicating that life continues after death; just like how the hair grows again.

A year after the person's death, the family sacrifices a bull to beseech the spirit return home. They believe the spirit must live with its family to guide and protect them.

If someone loses a spouse, they observe a one-year mourning period, during which the widow or widower wears black traditional Xhosa attire.

Where are the Xhosa originally from?

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Xhosa-speaking people have lived in South Africa's Eastern Cape area since the 7th century. Xhosa ancestors, the Nguni, are believed to have occupied central and northern Africa. They migrated and settled in the southern part of the continent before the arrival of the Dutch settlers.

Muvhango Teasers for July 2021: Will Mpho's baby be found?

The Nguni comprised several clans, such as the Gcaleka, Ngika, Ndlambe, Dushane, Qayi, and Gqunkhwebe of Khoisan origin. Their unity and ability to fight off colonial encroachment into their land were weakened by the famines and political divisions in the 19th century.

What language do the Xhosa speak?

The Xhosa language is called isiXhosa (or Xhosa in English). It is spoken by about 16% of South Africa's population. Unique click sounds distinguish this Bantu language and makes it sound slightly different from from Ndebele and Swazi languages. For example, the X, Q, KR, and CG form the clicks. The click Xhosa consonants were borrowed from Khoi or San words.

What are the Xhosa family rules?

The Xhosa family is primarily patriarchal. So, women and children submit to the men's authority and leadership as heads of households and the entire community. The tribe allows polygamous marriages so long as a man pays the lobola (bride price) for each wife.

Vele Manenje biography, age, on Muvhango, accident, awards

What do Xhosa homesteads look like?

Xhosa homesteads, imizi , are scattered over the rural landscape of the Eastern and Western Cape provinces of South Africa. The homesteads round huts with grass-thatched roofs and mud walls. The roof comprises circular wooded poles and saplings, bent and bound to form a conical shape.

A Xhosa homestead has several huts because they are polygamous. So, each wife needs a separate house. Additionally, sons who have been circumcised or married also need their own huts. The chiefs or wealthy men with large cattle herds sometimes allowed families not blood-related to reside at their homesteads.

What is the culture of Xhosa?

The Xhosa culture is extensive. First, they believe in a supreme being in Xhosa is called Mdali , Thixo , or Qamata . Xhosas communicate to him through ancestral intermediaries who invoke the spirits of the ancestors through rituals and sacrifices. Additionally, the Xhosas have unique wedding, birth, circumcision, and death rituals. They have traditional foods, folklore songs and stories, and native art.

Mzansi Magic Ehostela cast (with images), seasons, the full story

Did the Xhosa have any artwork?

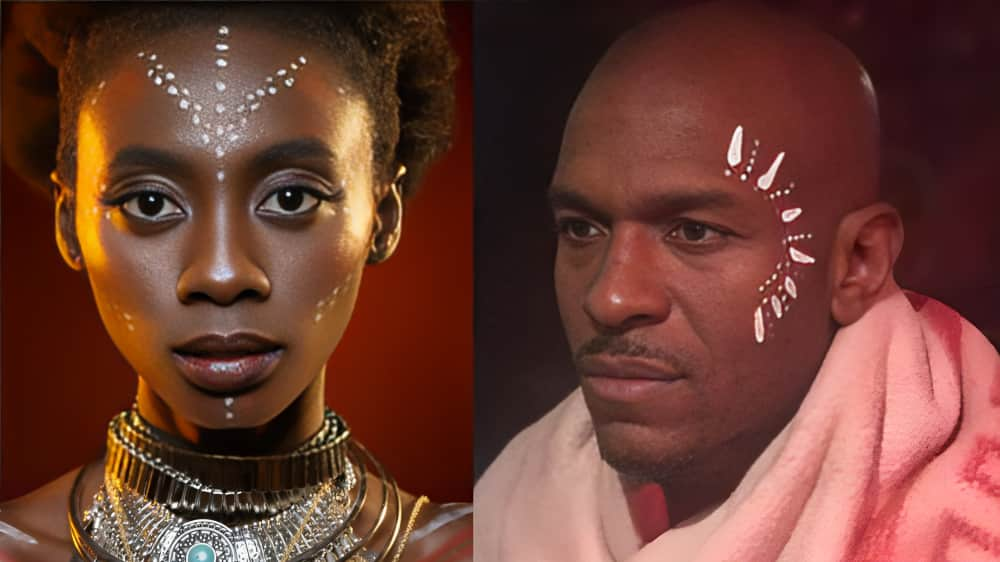

Umchokozo , face painting, plays a significant role in Xhosa culture. The white or yellow ochre decorations are sometimes painted over their eyebrows, the bridge of their noses, and cheeks.

For men, face painting indicates status and conveys a strong cultural meaning. Meanwhile, women decorate their faces as a ritual to prepare themselves to be custodians of their culture.

Xhosa people make beads from nutshells, wood, glass, and metal. Anyone can wear the Xhosa beadwork as a fashion statement, even if they are not descendants of this tribe.

Xhosa folklore songs and stories

Like other Bantu languages, the Xhosa culture is rich in folklore songs , dances, stories ( intsomi ), verbal expressions, idioms, poems ( izibongo ), and proverbs. Most Xhosa stories and folktales are about the tribe's history, religious beliefs, and heroes.

Qongqothwane , by Miriam Makeba, is a timeless Xhosa wedding song. Meanwhile, most popular Xhosa folklore stories are about the first person on Earth and the origin of death.

What is the most spoken language in South Africa? Top 11 languages

The Xhosa tribe believes death originated when Qamatha (god) sent the chameleon to earth to tell people they would never die. However, the chameleon got tired on its way to Earth and decided to rest.

The lizard found the chameleon resting and asked it where it was going. After the chameleon explained its mission, the lizard ran and told the people they would die. An outcry erupted on the Earth, with people crying because they were going to die.

When the chameleon heard this outcry, it proceeded to the earth to tell the people the true message from Qamatha , but they did not believe it. That is why people die.

What are the five habits of the Xhosa culture?

The Xhosa people emphasize traditional practices and customs inherited from their forefathers. Their culture is extensive because it has been practiced for centuries and passed down from generation to generation. Here are some five things they do:

Top 10 great ancient African leaders you should know about

- Xhosa people live in traditional homesteads called imizi.

- They speak in unique click sounds.

- A groom pays lobola (dowry) to the bride's family.

- They name children after their fathers and ancestors.

- Xhosa men undergo circumcision while the women pass through an initiation rite.

What is imbeleko in the Xhosa culture?

The imbeleko is a Xhosa child naming ceremony, and it marks the end of the ten-day mother and child seclusion period. The family introduces the baby to friends and relatives during this ceremony. Anyone can attend the event, including people who are not Xhosa.

What are some traditional customs of the Xhosa people?

The Xhosa people have many traditions and customs. Here are some five things they do:

- Xhosa boys learn to stick fighting early when herding cattle in the veld (pastures).

- Married Xhosa women wear long aprons over their dresses, cloaks over the dresses, head scarves, breaded jewelry, and carry sling bags called inxili .

- Xhosa men wear wraparound skirts running from the waist to the feet. These are accompanied by a long scarf thrown over one shoulder and serve as a cloak when it gets cold.

- Umchokozo , face painting, plays a significant role in Xhosa culture. They paint themselves over their eyebrows, the bridge of their noses, and cheeks.

- Xhosa homesteads have round mud huts with conical-shaped grass-thatched roofs.

Deception Zee World cast, full story, plot summary, teasers, final episode

Xhosa culture is broad and exciting to learn. Their beliefs, traditions, rituals, rites, and structures make them unique people. The Xhosa people are careful about preserving their culture and are dedicated to passing it on to the younger generations.

Briefly.co.za published an article about the top Sotho names for boys and girls. The Sotho language is part of the Bantu ethnic group, and there are three different dialectical groups within the Sotho tribe: Sepedi (northern Sotho), Sesotho, and Setswana.

The Sotho people are in Botswana, Lesotho, and South Africa. Like other African communities, they have a unique way of naming their newborns. Additionally, all Sotho names have deep cultural meanings.

Source: Briefly News

Faculty of Humanities

- Engineering and the Built Enviroment

- Health Sciences

- myUCT Email

- Writing Center

- Dean's welcome

- Applications Overview

- Undergraduate Programmes

- Admission requirements

- Orientation

- Transferring students

- Postgraduate programmes

- Admission Requirements Overview

- Semester Study Abroad applicants

- Funding your Studies

- International applicants

- Recognition of Prior Learning

- Humanities Students' Council

- Matric Exemption

- Registration

- Student advisors

- Student mentorship

- Third Term Courses

- Getting started

- You & your supervisor

- Ethics & plagiarism

- Preparing to submit

- Postgraduate Student Council

- Academic excellence

- Academic exclusion

- Change of Curriculum

- Concessions

- Leave of Absence

- Academic Departments

- Umthombo Centre for Student Success

- UCT English Language Centre

- Research Overview

- Research Ethics

- Awards & Achievements

- Alumni Overview

- Fund the Performing and Creative Arts

- News archive

- Faculty Office Staff

- Emergency Contacts

Language students experience Xhosa culture, first hand

Each year, Dr Tessa Dowling takes a group of her Xhosa Communication students to Cata, a small rural village located near Qoboqobo in the Eastern Cape. The field trip is designed to immerse students in the culture and traditions of African family life, whilst enabling them to hone their language skills. It is also an emotional and eye-opening experience from which no one returns the same.

Cata, which in isiXhosa means ‘to add a small amount’, is a picturesque village located in the former Ciskei. From the 1930’s onwards, it was a site of traumatic forced removals and dispossesion under the apartheid government. “During apartheid, villagers were subjected to forced removals under the guise of a ‘betterment programme”. The aim being to reduce their wealth and confidence as powerful, successful farmers and to create division amongst an otherwise united community” says Dr. Dowling who is a senor lecturer in African Languages at UCT. In 2008, she was commissioned by the Border Rural Committee to establish language workshops for families who were hosting ‘homestays’ for foreign researchers but finding it difficult to teach their home language to their visitors. In this next extract, she describes the sights and sounds of Cata as well as her observations on the student summer field trip:

You wake up to the sound of people greeting each other with loud friendliness, reminding one of that Telkom advertisement “Molo, mhlobo wam!” where the two pensioners phone each other but still shout their greetings across the hills. Children, slightly dusty from playing with the piglets outside the house, crawl into bed with you and teach you, with an air of sophisticated tolerance: Yingubo (It is a blanket), Yifestile (It is a window) and laugh at the way you say their names “Olwethu” (ours), “Asekhona” (they are still around), “Siyabulela” (we give thanks). And go absolutely hysterical when you attempt a click “Yingxaki!” (It is a problem!) They follow you to the loo, which is just the other side of the spinach field, and hold the wobbly door shut while you pee, looking out across a view that is almost cheeky with undiscovered charm. This is the Xhosa Communication field trip, which in previous years has been generously financed by the Vice-Chancellor’s special fund. Once a year, from 2010 to 2012, I bundled up eager Xhosa Communication students, and took them to Cata, a tiny village just outside Qoboqobo (Keiskammahoek) near Qonce (King William’s Town).

I never knew exactly what they were expecting, my students, but after a 17-hour bus trip followed by a hilarious taxi ride into the village, the taxi driver inseparable from his cellphone and smilingly reassuring us – “Akhongxaki, akhongxaki” (no problem, no problem) – as he one-handedly lurched us across yet another pothole or weaved through a herd of sheep, the conversations about boyfriends and food and learning Xhosa turned into an oneiric hush as we swerved into the main street of Cata. My students suddenly realize it is two weeks here, and there isn’t a Woolworths in sight. Or a place to plug in a hairdryer. Or a loo that flushes. They are here for the reason they are here: to listen to Xhosa, to speak Xhosa, to dream in Xhosa, to make friends. And it works! These field trips have created softer, gentler, humbler students (the best kind for learning a language), more willing to admit their language skills will only improve if they integrate, try to communicate with people in a society where English is not that important, but water is.

The 2014 class have been hard at work all year fundraising for the next trip which is scheduled to take place in Januaury 2015. The group includes Xhosa first-language speakers who have not had the opportunity to learn their mother-tongue formally as a first language at school. There is also an ongoing research component to the Cata field trip. Dr Dowling will be in village next month as part of her research into language change in Xhosa. The first part of her study, which investigates the migration of Xhosa nouns and concords, has already been accepted for publication in the South African Journal of African Languages. The second part focuses on the use of Xhosa vocabulary and on the ways in which children assimilate English words into the urban Xhosa vocabulary. After studying language use in Cape Town, Dr Dowling observed that for instance instead of using the Xhosa word uphahla for roof, children use i-roof, instead of isiselo for drink they use i-drink. “I hope that what I discover will go some small way towards helping inform educational programmes and texts. Children need to learn the correct grammar and vocabulary of the language but educationalists also need to take into account that vocabularies shift and change all the time in all languages” says Dowling.

About Cata Cultural Village ‘Homestays’ in Cata afford the visitor an opportunity to stay with a family, sharing their food and experiencing their hospitality in exchange for a small fee. This type of accommodation arrangement is becoming increasingly popular with visitors to the Eastern Cape and simultaneously serves to boost the local economy. Cata Cultural Village coordinate eco-tours for vistors and there is a museum and

- Environment

- Information Science

- Social Issues

- Argumentative

- Cause and Effect

- Classification

- Compare and Contrast

- Descriptive

- Exemplification

- Informative

- Controversial

- Exploratory

- What Is an Essay

- Length of an Essay

- Generate Ideas

- Types of Essays

- Structuring an Essay

- Outline For Essay

- Essay Introduction

- Thesis Statement

- Body of an Essay

- Writing a Conclusion

- Essay Writing Tips

- Drafting an Essay

- Revision Process

- Fix a Broken Essay

- Format of an Essay

- Essay Examples

- Essay Checklist

- Essay Writing Service

- Pay for Research Paper

- Write My Research Paper

- Write My Essay

- Custom Essay Writing Service

- Admission Essay Writing Service

- Pay for Essay

- Academic Ghostwriting

- Write My Book Report

- Case Study Writing Service

- Dissertation Writing Service

- Coursework Writing Service

- Lab Report Writing Service

- Do My Assignment

- Buy College Papers

- Capstone Project Writing Service

- Buy Research Paper

- Custom Essays for Sale

Can’t find a perfect paper?

- Free Essay Samples

Xhosa people

Updated 24 April 2021

Subject Identity , Myself

Downloads 106

Category Life , Sociology

Topic Generation , Minority , Values

From generation to generation, the moral, religious and political values of a culture are handed on.

Economic activity, works cited.

Deadline is approaching?

Wait no more. Let us write you an essay from scratch

Related Essays

Related topics.

Find Out the Cost of Your Paper

Type your email

By clicking “Submit”, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy policy. Sometimes you will receive account related emails.

- Constructed scripts

- Multilingual Pages

Xhosa ( isiXhosa )

Xhosa is a Bantu language spoken in South Africa, mainly in the Eastern Cape, Western Cape, Free State and Northern Cape. It is also in parts of Lesotho and Zimbabwe. According to the 2011 census there are about 8.2 million native speakers of Xhosa, and another 11 million second language speakers.

Xhosa at a glance

- Native name : isiXhosa [isikǁʰɔ́ːsa]

- Language family : Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Benue-Congo, Southern Bantoid, Bantu, Southern Bantu, Nguni, Zunda

- Number of speakers : c. 19 million

- Spoken in : South Africa, Zimbabwe, Lesotho

- First written : 1823

- Writing system : Latin script

- Status : official language in South Africa and Zimbabwe

Xhosa is an official language in South Africa and Zimbabe, and is used as a language of instruction in primary schools, and in some secondary schools. It is also taught in universities. There are books, magazines and newspapers in Xhosa, as well as TV and radio programmes, films, plays and songs.

Xhosa is closely related to Zulu , Swati and Ndebele , and mutually intelligible with them to some extent.

Xhosa's click consonants were most likely borrowed from the Khoisan languages as a result of long and extensive interaction between the Xhosa and Khoisan peoples.

A system for writing Xhosa using the Latin alphabet was devised by Christian missionaries during the early 19th century. The first printed work in Xhosa was published in 1823.

Xhosa alphabet

Hear the Xhosa alphabet:

Xhosa pronunciation

Hear how to pronounce Xhosa:

Download an alphabet chart for Xhosa (Excel)

Sample text in Xhosa

Bonke abantu bazalwa bekhululekile belingana ngesidima nangokweemfanelo. Bonke abantu banesiphiwo sesazela nesizathu sokwenza isenzo ongathanda ukuba senziwe kumzalwane wakho.

Translation

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. (Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights)

Some corrections to this page by Michael Peter Füstumum

Sample video in Xhosa

Information about Xhosa | Phrases | Numbers | Colours | Family words | Tower of Babel | Books about Xhosa on: Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk [affilate links]

Information about the Xhosa language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xhosa_language https://www.ethnologue.com/language/xho

Online Xhosa lessons https://www.memrise.com/course/1572/xhosa-an-intro/ http://learn101.org/xhosa.php http://ilanguages.org/xhosa.php http://xhosaculture.co.za/about-us/learn-xhosa/ http://www.youtube.com/user/XhosaKhaya https://www.twinkl.co.za/resources/south-africa-resources/isixhosa-foundation-phase-english-south-africa-suid-afrika/2

Online Xhosa dictionaries http://www.freelang.net/dictionary/xhosa.php http://glosbe.com/en/xh/ http://www.gononda.com/xhosa/

Xhosa phrases http://www.salanguages.com/isixhosa/xhowrd.htm http://www.southafricalogue.com/travel-tips/south-african-phrases-xhosa.html

Bantu languages