World War II Research Essay Topics

Frank Whitney / Getty Images

- Writing Research Papers

- Writing Essays

- English Grammar

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

Students are often required to write a paper on a topic as broad as World War II , but you should know that the instructor will expect you to narrow your focus to a specific thesis. This is especially true if you are in high school or college. Narrow your focus by making a list of words, much like the list of words and phrases that are presented in bold type below. Then begin to explore related questions and come up with your own cool WWII topics. The answer to questions like these can become a good starting point for a thesis statement .

Culture and People

When the U.S. entered into war, everyday life across the country changed drastically. From civil rights, racism, and resistance movements to basic human needs like food, clothing, and medicine, the aspects of how life was impacted are immense.

- African-Americans and civil rights. What impact did the war years have on the rights of African-Americans? What were they allowed or not allowed to do?

- Animals. How were horses, dogs, birds, or other animals used? Did they play a special role?

- Art. What art movements were inspired by wartime events? Is there one specific work of art that tells a story about the war?

- Clothing. How was fashion impacted? How did clothing save lives or hinder movement? What materials were used or not used?

- Domestic violence. Was there an increase or decrease in cases?

- Families. Did new family customs develop? What was the impact on children of soldiers?

- Fashion. Did fashion change significantly for civilians? What changes had to be made during wartime?

- Food preservation. What new preservation and packaging methods were used during and after the war? How were these helpful?

- Food rationing. How did rationing impact families? Were rations the same for different groups of people? Were soldiers affected by rations?

- Love letters. What do letters tell us about relationships, families, and friendships? What about gender roles?

- New words. What new vocabulary words emerged during and after WWII?

- Nutrition. Were there battles that were lost or won because of the foods available? How did nutrition change at home during the war because of the availability of certain products?

- Penicillin and other medicine. How was penicillin used? What medical developments occurred during and after the war?

- Resistance movements. How did families deal with living in an occupied territory?

- Sacrifices. How did family life change for the worse?

- Women's work at home. How did women's work change at home during the war? What about after the war ended?

Economy and Workforce

For a nation that was still recovering from the Great Depression, World War II had a major impact on the economy and workforce. When the war began, the fate of the workforce changed overnight, American factories were repurposed to produce goods to support the war effort and women took jobs that were traditionally held by men, who were now off to war.

- Advertising. How did food packaging change during the war? How did advertisements change in general? What were advertisements for?

- Occupations. What new jobs were created? Who filled these new roles? Who filled the roles that were previously held by many of the men who went off to war?

- Propaganda. How did society respond to the war? Do you know why?

- Toys. How did the war impact the toys that were manufactured?

- New products. What products were invented and became a part of popular culture? Were these products present only during war times, or did they exist after?

Military, Government, and War

Americans were mostly against entering the war up until the bombing of Pearl Harbor, after which support for the war grew, as did armed forces. Before the war, the US didn't have the large military forces it soon became known for, with the war resulting in over 16 million Americans in service. The role the military played in the war, and the impacts of the war itself, were vast.

- America's entry into the war. How is the timing significant? What factors are not so well known?

- Churchill, Winston. What role did this leader play that interests you most? How did his background prepare him for his role?

- Clandestine operations. Governments went to great lengths to hide the true date, time, and place of their actions.

- Destruction. Many historic cities and sites were destroyed in the U.K.—Liverpool, Manchester, London, and Coventry—and in other nations.

- Hawaii. How did events impact families or society in general?

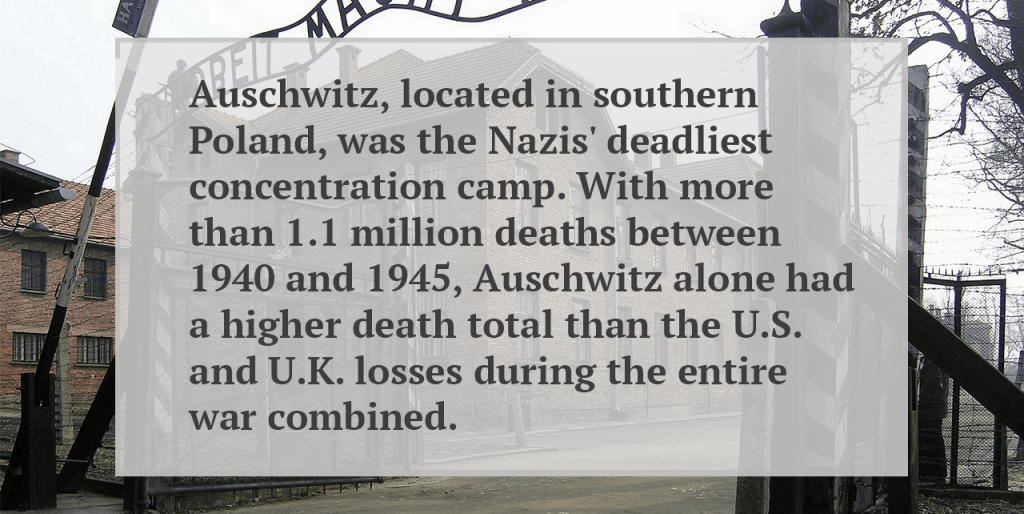

- The Holocaust. Do you have access to any personal stories?

- Italy. What special circumstances were in effect?

- " Kilroy was here ." Why was this phrase important to soldiers?

- Nationalist Socialist movement in America. What impact has this movement had on society and the government since WWII?

- Political impact. How was your local town impacted politically and socially?

- POW camps after the war. Where were they and what happened to them after the war? Here's a starting point: Some were turned into race tracks after the war!

- Prisoners of war. How many POWs were there? How many made it home safely? What were some long-lasting effects?

- Spies. Who were the spies? Were they men or women? What side were they on? What happened to spies that were caught?

- Submarines. Were there enemy submarines on a coast near you? What role did submarines play in the war?

- Surviving an attack. How were military units attacked? How did it feel to jump from a plane that was disabled?

- Troop logistics. How were troop movements kept secret? What were some challenges of troop logistics?

- Views on freedom. How was freedom curtailed or expanded?

- Views on government's role. Where was the government's role expanded? What about governments elsewhere?

- War crime trials. How were trials conducted? What were the political challenges or consequences? Who was or wasn't tried?

- Weather. Were there battles that were lost or won because of the weather conditions? Were there places where people suffered more because of the weather?

- Women in warfare. What roles did women play during the war? What surprises you about women's work in World War II?

Technology and Transportation

With the war came advancements in technology and transportation, impacting communications capabilities, the spread of news, and even entertainment.

- Bridges and roads. What transportation-related developments came from wartime or postwar policies?

- Communication. How did radio or other types of communication impact key events?

- Motorcycles. What needs led to the development of folding motorcycles? Why was there widespread use of military motorcycles by the government?

- Technology. What technology came from the war and how was it used after the war?

- TV technology. When did televisions start to appear in homes and what is significant about the timing? What TV shows were inspired by the war and how realistic were they? How long did World War II affect TV programming?

- Jet engine technology. What advances can be traced to WWII needs?

- Radar. What role did radar play, if any?

- Rockets. How important was rocket technology?

- Shipbuilding achievements. The achievements were quite remarkable during the war. Why and how did they happen?

"America's Wars Fact Sheet." U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, May 2017.

- 5 Key Causes of World War I

- 'Unbroken' by Laura Hillenbrand Book Club Discussion Questions

- Women and World War II

- Understanding the Progressive Era

- Women and World War II: Women at Work

- Women and Work in World War I

- America and World War II

- Who Were the Viet Cong and How Did They Affect the War?

- Women in World War I: Societal Impacts

- The US Economy in World War I

- Guns or Butter: The Nazi Economy

- Mexican Involvement in World War II

- Famous Americans Killed in World War II

- History of Government Involvement in the American Economy

- Canadian World War II Posters Gallery

- Rosie the Riveter and Her Sisters

Skip to Main Content of WWII

Research starters.

Beginning a research paper on World War II can be daunting. With Research Starters, you can get a basic introduction to major WWII topics, see recommended secondary sources, and view primary sources you can use from the Museum’s collection.

Research Starters: Worldwide Deaths in World War II

See estimates for worldwide deaths, broken down by country, in World War II.

Research Starters: US Military by the Numbers

See a breakdown of numbers in the US military, by branch and year, in World War II.

Research Starters: The Draft and World War II

On September 16, 1940, the United States instituted the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, which required all men between the ages of 21 and 45 to register for the draft.

Research Starters: The GI Bill

Research Starters: Higgins Boats

In the late 1930s, the U.S. military began developing small boats that could carry troops from ships to open beaches.

Research Starters: The Battle of Midway

Fought between the U.S. and Japanese navies June 4-7, 1942, this battle turned the tide of the war in the Pacific in favor of the Americans.

Research Starters: Women in World War II

With ever-growing orders for war materials combined with so many men overseas fighting the war, women were called upon to work in ways previously reserved only for men.

Ration Books

Ask anyone who remembers life on the Home Front during World War II about their strongest memories and chances are they will tell you about rationing. You see, the war caused shortages of all sorts of things: rubber, metal, clothing, etc. But it was the shortages of various types of food that affected just about everyone on a daily basis.

Take A Closer Look: America Goes to War

America's isolation from war ended on December 7, 1941, when Japan staged a surprise attack on American military installations in the Pacific.

History At a Glance: Women in World War II

American women played important roles during World War II, both at home and in uniform.

World War 2 Essay: Outline + 100 WW2 Research Topics

This time you have to write a World War II essay, paper, or thesis. It means that you have a perfect chance to refresh those memories about the war that some of us might forget.

So many words can be said about the war in that it seems you will simply get lost in a variety of WW2 research topics and questions.

Still, you do not know what to write about in your World War 2 essay for middle school. Of course, you may look through several free essays in search of ideas. However, you may find our suggestions interesting or get instant writing help right here.

- 🔝 Top 10 Topics

- 🎓 Essay Topics for Student

- 🎖️ WW2 Argumentative Essay Topics

- 💡 More Topic Examples

- 📑 Outline Examples

- 💁 General Info

🔗 References

🔝 top 10 ww2 essay topics.

- Was the battle of Dunkirk a failure?

- WWII technologies that changed our lives

- The outcome of the Nuremberg trials

- Medical experiments during the Holocaust

- Battle of Midway as a turning point in WWII

- Why is penicillin a wonder of World War 2?

- Why is the Bataan Death March a war crime?

- The impact of propaganda during WWII

- Racial segregation in the armed forces during WWII

- What makes the Battle of Stalingrad the deadliest in WWII?

🎓 WW2 Essay Topics for Student

- Contributions of women pilots in World War II

- “Gesture Life” and “Maus”: post-World War II injuries

- The federal government’s actions during World War II

- Rebuilding Europe after World War II

- World War II in Europe: development and costs

- World War II: maskirovka military deception and denials operations

- World War II in the Pacific region

- The second World War’s historical aspects

- The rise and fall of communism after World War II

- South Africa in World War II

- Battle of the Midway during World War II

- World War II: the history of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- What effect did the World War II wartime experience have on African Americans?

- The battle of Britain during World War II

- World War II was a continuation of World War I

- Communism in Europe and America after World War II

- Camps for displaced persons after the end of World War II

- Nazis prosecution for the World War II crimes

- World War II was avoidable

- Nazi Germany’s resources and demise in World War II

- The United States and East Asia since World War II

- Japan after World War II: main events and modifications

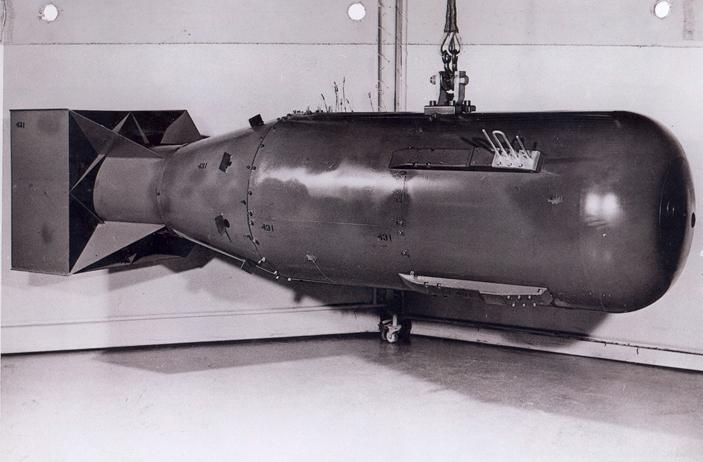

- Atomic bomb technology and World War II outcomes

- Pacific theater of World War II

- Impact of World War II on Balkan nationalism, states and societies

- World War II: internment of the Japanese Americans

- World War II in “The Rape of Europa” Documentary

- The characteristics of successful warfare after the second World War

- Great Depression and World War II impact on the United States economy

- Battle of the Bulge during World War II

- Escape from Sobibor: World War 2 holocaust

- World War II: why Germans lost and allies won

- World War II impact on racial issues in the United States

- Women’s representations before and after World War II

- United States-Japan relations during World War II

- Second World War: cause and technology

- American foreign policy since World War II

- World War II, the Cold War and New Europe

- The Crete battle of World War II

- Home front of the United States during the second World War

🎖️ WW2: Argumentative Essay Topics

As it happens quite often, teachers like to ask students to write an essay on World War II. However, don’t expect it to be easy. It should be something more narrow than the essay about the causes of World War II.

You can use some practical techniques to come up with a suitable topic. For instance, some of the most popular ones are mind mapping and brainstorming. Don’t forget to use questions to create a perfect thesis statement.

But we have made your life so much easier and prepared this comprehensive list of WWII argumentative essay topics. There are also short hints to help you start with your paper.

🔫 World War 2 Essay Topics: Military

- Exploring the effects of WWII on life in Hawaii. Research the impact of those events on the social life of families living there.

- Family memories of the Holocaust. Dig deep and see if you have any (distant) relatives who were the witnesses.

- Something unique about Italy in WWII. Look into some exceptional circumstances that occurred there at the time of the war.

- The origins of the phrase “Kilroy was here.” It is quite a controversial topic, so you might want to study all the sources you can find.

- Nationalist Socialists: examine the importance of the movement in the US. What was its social impact since the war? Describe this in your WW2 essay.

- Write about your town/city. Conduct research to find out about the political changes in your hometown related to war.

- The transformation of the prisoner-of-war camps . Write about what happened to the POW camps after the end of the war.

- The fate of the prisoners of war. Study the documents to get to know what happened to them and whether they continued their healthy lives.

- Describe the spies that participated in WWII . Who were they? What usually happened to those who were caught by different sides?

- The role of women . Discover the contribution of the weaker sex in warfare and write about the most surprising facts.

- How important were the weather conditions for the outcomes of WWII ? Find out which battles were lost or won due to the weather.

- War crimes: consequences. Conduct research to answer the questions about the war crime trials, their outcomes, and the most notorious cases.

- Research the role of the US government in WWII . Compare it to the other governments and analyze the strategies they were using.

- The sense of freedom during the war. For this WW2 essay topic, you would need to look critically at how freedom was suppressed or expanded.

- What was so special about the movements of the troop? Here, you would be expected to provide the answers concerning the secrecy and challenges.

- The experiences of the attack survivors. Find out what was happening during the attack on the military units and the planes.

🤖 World War 2 Essay Topics: Technology

- The role of the submarines in the war. This World War II research topic is all about the importance of the submarines.

- Estimate the destruction in the UK. Find out how many historical places were wiped out as a result of the war.

- Was Winston Churchill prepared for it? Write about the background of that influential leader and how it helped him at the wartime.

- Write about the time the US entered the war. Are there any facts that we still don’t know well enough? What about the timing?

- The miracle of the radar. This WW2 essay topic would be interesting for those who are fascinated by technology. What was the role of that device in WWII?

- Rocket technology and the war. Write about the importance of the rockets and what the moment when they changed the course of the war.

- Building the ultimate warship. What was the driving force of the developments in the field of shipbuilding during WWII?

- Describe the main means of communication during the war. Don’t forget to mention the radio and its impact on the major events in your World War 2 essay.

- The development of bridges and roads. What were the main technological achievements in this field that still impact our everyday life?

- Explain the rise of the popularity of motorcycles during the war. Feel free to mention the folding bikes and their invention.

- The technology we have thanks to the war. Dedicate your WW2 essay to the inventions we can’t live without nowadays that were created during the war.

- What about TVs? You can narrow down this World War II essay question as you wish. For example, write about the shows dedicated to the war.

- The jet engines developed by the needs of war. Look into the reasons why those engines were created during WWII.

💰 WW2 Research Topics: Economy

- What about propaganda? This WWII essay should describe how people in the US were reacting to the war and why.

- The product of war: pop culture elements. Think about products that became popular and maybe even stayed a part of culture after the war ended.

- Toy story: WWII edition. Find out how the war influenced the toy production and whether it was a part of propaganda.

- The major changes in the job market sponsored by WWII. What new roles suddenly appeared on the job market, thanks to the war?

- The power of advertising. To narrow it down, you can even mention how the food packaging was adjusted and why.

🎨 WW2 Research Topics: Culture

- Discover the world of fashion during the wartime . It is one of the cool WWII essay topics. It should be about the new trends for civilians at the time.

- The analysis of artworks created during WWII. Choose a piece of art inspired by war and analyze it. What is its story?

- New times require new family traditions. How were the customs inside the families changed by the war? What about raising children? Highlight these issues in your World War 2 essay.

- The secrets of the love letters during the war. This short essay would require you to dig into the archives and find out what the letters could tell us about the relationships back then.

- What was the unique role of animals in WWII? Dedicate your writing to some type of animal and discuss how they were used.

- The rights of African-Americans during the time of war. Write about how their civil rights were changed and try to find the root causes.

- Food preservation methods: another revolution. This example is all about food and how it was packed and preserved during the war.

- The cases of domestic violence during the cold war. Were the rates higher at the time? Did political tension cause it? This is also a great World War 2 essay topic.

- Expanding the vocabulary. Just like any other part of life, the language also went through some changes. What were the new words that emerged?

- The troubled life of housewife during WWII. Describe the work women used to do at the wartime and how it was changed.

- Still resisting: the movements created by families. Here, you should concentrate on the experience of the families that live in the occupied territories.

- Lifesaving food: the role of nutrition in WWII. Try to research and find the battles that were lost or won due to the availability of food.

- The impact of food rationing on soldiers and families. Write your WW2 essay about the struggles of families and different groups of people.

- What were the common sacrifices of families during the war? In this essay, you would need to look into the negative changes in families’ lifestyles.

- The miracle of penicillin: WWII. This research aims to uncover the importance of penicillin or any other medicine of your choice.

- The clothes that saved lives. Write about different types of clothing and materials that were used to help the soldiers on the battlefield.

💡 World War 2 Essay: More Topic Examples

Below, other suggestions on what you might write about in essays on World War II are presented:

Present in Your World War 2 Essay Alternative Decisions That Could Have Changed the Course of the War Dramatically

Such World War 2 essay will aim to explore some of the greatest decision making mistakes of the world leaders. We do not mean that you should discuss some miraculous history events like “what if Hitler had a heart attack.” In the World War 2 essay devoted to this problem, give realistic alternative decisions that were considered but not realized. Analyze those alternatives that could have changed the end of the war.

“In Your World War Ii Essay, Try to Answer the Question “When Did Hitler Lose the War?”

When did Adolf Hitler lose his chance to win World War II? What was it? These are the World War 2 essay questions you have to answer. Analyze different viewpoints of historians and present your opinion in the essay on World War 2.

Cover the Themes of Atrocity and War-Crimes in the World War 2 Essay

Acts of genocides and atrocity against civil population occurred in such countries as Japan, the Soviet Union, and Germany. Some of them were so horrific and immense that they changed the psyche of many people and different nations. When disclosing this theme in the Second World War essay, tell about Nazi concentration camps, “Death-camps,” the Holocaust , etc.

If you are interested in other history essay topics, read our hints for writing terrorism essays . And don’t forget to tell us in comments below your opinion about the World War 2.

📑 World War 2 Essay: Outline Examples

The next is creating a neat outline, which would become a massive help for you during the process of writing. Find examples of World War II essay outlines below!

Example 1. Analyze how some alternative decisions could have changed the course of World War II

Try to pick something realistic. Merely writing that if Hitler suddenly died and the war had never happened is just dull. Get creative and maybe take as a basis some real facts that were considered but never came into life.

- In your World War II essay introduction , present the chosen decision. Include your thesis statement in this part as well. It should be your hypothesis concerning the topic.

- In the main body , give at least three arguments why and how that decision would have changed things. Here, you prove your hypothesis to be right. You may add one counter-argument if you wish. For instance, include the opinion of a historian saying that it wouldn’t change anything.

- In conclusion , state your opinion once again, which is now supported by arguments.

Example 2. When did it happen that Germany lost the war?

Think about when Adolf Hitler might have missed his chance to win World War II. What was it? Include some details. Once again, do your research and consider the opinions of different historians.

- In the introduction to this World War 2 essay , present your point of view. In the thesis statement, write the answer to World War II essay questions clearly and coherently.

- The main body here is for you to include three to five pieces of evidence that may prove you right. If you decide to write an argumentative essay, you might add some contradicting facts, too.

- In the last part of your writing, focus on paraphrasing your thesis statement.

Example 3. World War II: discuss war crimes and atrocity

This essay title is related to all acts of cruelty against the civil population, including genocides. You may want to narrow it down according to your preferences. For instance, you can talk about how concentration camps created by Nazis have changed the people’s psyche.

- Introduce this WW2 essay topic by stating how people have changed after surviving the Death Camps. It might be a good idea to include a sentence at the beginning that may serve as a hook to make your readers interested.

- In the body , present not less than three examples of what you think might be relevant. Those should be proven historical facts if you want your essay to be persuasive.

- Conclude by providing a summary of the facts presented in the main body. Add the paraphrased thesis statement.

💁 World War 2: General Information

World war ii: timeline.

Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. And on September 3, 1939, France and Britain, fulfilling their obligations to Poland, declared war on Germany and World War II began.

However, the beginning of World War II was preceded by some events, inextricably related:

- September 18, 1931. Japan attacked Manchuria

- October 2, 1935 – May 1936. Fascist Italy invaded Ethiopia, conquered and annexed it

- October 25 – November 1, 1936. On October 25, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy concluded a cooperation agreement. November 1 announced the creation of the “ Rome-Berlin Axis “

- November 25, 1936. Nazi Germany and imperialist Japan concluded the Anti-Comintern Pact, directed against the USSR and the international communist movement

- July 7, 1937. Japan invaded China. The World War II began in the Pacific

- 11-13 March 1938. Germany joins Austria (the so-called Anschluss)

- September 29, 1938. Germany, Italy, Great Britain and France signed the Munich agreement obliging the Czechoslovak Republic to cede Nazi Germany to the Sudetenland (where the critical Czechoslovak fortifications were located)

- 14-15 March 1939. Under pressure from Germany, the Slovaks declared their independence and created the Slovak Republic. The Germans broke the Munich agreement , occupied the Czech lands, and established the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

- March 31, 1939. France and the United Kingdom provided guarantees of the inviolability of the borders of Poland

- 7-15 April 1939. Fascist Italy attacked Albania and annexed it

- August 23, 1939. Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact and a secret annex to it, according to which Europe was divided into spheres of influence

Some scientists think that the World War II was a continuation of the World War I ended in 1918.

September 2, 1945, is the date when the World War II ended. Japan, agreed to unconditional surrender on August 14, 1945, officially capitulates, thereby putting an end to World War II.

World War II: Key Facts

- Perhaps, the World War II was one the most destructive wars in modern history. About 27,000 people were killed each day from September 1, 1939, to September 2, 1945.

- The primary opponents were Nazi Germany, fascist Italy, Imperial Japan on the one hand, and the Soviet Union, Great Britain, France the United States , and China on the other.

- Germany capitulated on May 7, 1945 . At the same time, Japan continued to fight for another four months before their capitulation on September 2. Atomic bombs, dropped by American troops on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, were first used against Japan.

- The end of the war was marked by Britain losing most of its empire . At the same time, World War II accelerated the revival of the US and Soviet economies as global superpowers.

- After the end of the World War II, the “Cold War” between the US and the USSR started.

World War 2: Casualties

The exact World War II casualties remain unknown. However, historians name that the total number of victims was over 60 million people including military and civilians killed. Below you’ll find the list of states suffered the highest losses:

- 42,000,000 people–USSR

- 9,000,000 people–Germany

- 4,000,000 people–China

- 3,000,000 people–Japan

World War II: Causes

Perhaps, there were many prerequisites for World War II:

- Japan’s victory over Russia in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) opened the door for Japanese expansion in the Asia-Pacific region

- The US Navy first developed plans to prepare for a naval war with Japan in 1890

- The Great Depression, and the global recession that followed

- The coming to power of Hitler and his statement about the injustice of the Versailles Treaty, signed in 1918

- The creation in 1935 of the Luftwaffe, as a direct violation of the 1919 treaty

- Remilitarization of the Rhineland in 1936

- Anschluss of Austria and the annexation of part of Czechoslovakia

- Italy’s desire to create a Third Rome and Japan’s goal to create an independent state with the Pan-Asian sphere of influence

World War II: Results

The results of World War II are not limited to losses and destruction. As a result of the war, the face of the world changed: new borders and new states appeared, new tendencies of social development emerged, and significant inventions were made.

The war gave a strong impetus to the development of science and technology. Radar, jet aircraft, ballistic missiles, antibiotics, electronic computers and many other discoveries were made or entered into widespread use during the war. The foundations of the scientific and technological revolution were laid, which transformed and continued to change the postwar world.

The ideology of fascism, Nazism, racism, colonialism thoroughly discredited itself; on the contrary, the ideas of anti-fascism, anti-colonialism, democracy, and socialism gained wide popularity.

The human rights recorded in the UN Charter are internationally recognized. The influence of parties and groups that fought for democracy and social transformations–communists, socialists, social democrats, Christian democrats and other democratic forces, has sharply increased.

In many countries, significant reforms carried out: partial nationalization of industry and banks, the creation of a state system of social insurance, the expansion of workers’ rights. In some countries, including France, Italy, Germany, Japan, have adopted new, democratic constitutions. There was a profound renewal of the society, democratization of state and public institutions.

The colonial system disintegration was another significant result and consequence of the Second World War. Before the war, the vast majority of the world’s population lived in colonies, the area, and population of which many times exceeded the metropolitan countries: Britain, France, Holland, Belgium, Italy, and Japan.

During the World War 2 and after its end, part of the dependent and colonial countries (Syria, Lebanon, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Indonesia, Burma, Philippines, and Korea) declared itself independent. In 1947, India became independent, divided into two dominions: India and Pakistan. The intense process of liberation of the colonial peoples began, which continued until the complete abolition of the colonies in the second half of the twentieth century.

As a result of the war, the balance of forces in the world has changed dramatically. Germany, Italy, Japan were defeated, for a time turned into dependent countries, occupied by foreign troops. The war destroyed their economy, and they for many years could not compete with their former competitors.

Compared with the pre-war time, the positions of France and even Great Britain weakened considerably. The USA came out of the war significantly strengthened. Having surpassed all other countries economically and militarily, the United States became the sole leader of the capitalist world.

The second “superpower” was the Soviet Union. By the end of the war, the Soviet Union had the most massive land army in the world and substantial industrial potential. The USSR Armed Forces were in many countries of Central and Eastern Europe, East Germany and North Korea.

Some countries liberated by the Soviet Union took the road of non-capitalist development. After the liberation from the occupiers in Albania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, people’s democratic governments were established with the participation or under the leadership of the Communists, who began profound social transformations. By the Yalta agreements , these countries were considered to be the sphere of influence of the Soviet Union and were in fact under its control.

If the United States became the leader of the capitalist world, then the Soviet Union led the social forces that opposed capitalism. Two main poles of attraction of the world forces, conventionally called the East and the West, were formed; began to build two ideological and military-political blocs, the confrontation of which largely determined the structure of the post-war bipolar world.

The anti-fascist coalition split. Its participants came into conflict with each other, and the “ Cold War ” that lasted more than 45 years, until the collapse of the USSR.

This might be interesting for you:

- Interesting History Essay Topics and Events to Write About

- A List of History Websites for a Perfect Research

- Essay on India after Independence: How-to Guide and Prompts

- World War II Research Essay Topics: ThoughtCo

- Coming in from the Cold: The Newsmagazine of the American Historical Association

- A guide to historical research (BBC)

- Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time: The New York Times

- Why Hitler’s grand plan during the second world war collapsed: The Guardian

- Historical Research: ECU

- Humanities Research Strategies: Historical Methodologies (USC Libraries)

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

![world war ii thesis statement 413 Science and Technology Essay Topics to Write About [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/scientist-working-in-science-and-chemical-for-health-e1565366539163-284x153.png)

Would you always go for Bill Nye the Science Guy instead of Power Rangers as a child? Were you ready to spend sleepless nights perfecting your science fair project? Or maybe you dream of a career in science? Then this guide by Custom-Writing.org is perfect for you. Here, you’ll find...

![world war ii thesis statement 256 Satirical Essay Topics & Satire Essay Examples [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/classmates-learning-and-joking-at-school-e1565370536154-284x153.jpg)

A satire essay is a creative writing assignment where you use irony and humor to criticize people’s vices or follies. It’s especially prevalent in the context of current political and social events. A satirical essay contains facts on a particular topic but presents it in a comical way. This task...

![world war ii thesis statement 267 Music Essay Topics + Writing Guide [2024 Update]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/lady-is-playing-piano-284x153.jpg)

Your mood leaves a lot to be desired. Everything around you is getting on your nerves. But still, there’s one thing that may save you: music. Just think of all the times you turned on your favorite song, and it lifted your spirits! So, why not write about it in a music essay? In this article, you’ll find all the information necessary for this type of assignment: And...

Not everyone knows it, but globalization is not a brand-new process that started with the advent of the Internet. In fact, it’s been around throughout all of human history. This makes the choice of topics related to globalization practically endless. If you need help choosing a writing idea, this Custom-Writing.org...

In today’s world, fashion has become one of the most significant aspects of our lives. It influences everything from clothing and furniture to language and etiquette. It propels the economy, shapes people’s personal tastes, defines individuals and communities, and satisfies all possible desires and needs. In this article, Custom-Writing.org experts...

Early motherhood is a very complicated social problem. Even though the number of teenage mothers globally has decreased since 1991, about 12 million teen girls in developing countries give birth every year. If you need to write a paper on the issue of adolescent pregnancy and can’t find a good...

Human rights are moral norms and behavior standards towards all people that are protected by national and international law. They represent fundamental principles on which our society is founded. Human rights are a crucial safeguard for every person in the world. That’s why teachers often assign students to research and...

Global warming has been a major issue for almost half a century. Today, it remains a topical problem on which the future of humanity depends. Despite a halt between 1998 and 2013, world temperatures continue to rise, and the situation is expected to get worse in the future. When it...

Have you ever witnessed someone face unwanted aggressive behavior from classmates? According to the National Center for Educational Statistics, 1 in 5 students says they have experienced bullying at least once in their lifetime. These shocking statistics prove that bullying is a burning topic that deserves detailed research. In this...

Recycling involves collecting, processing, and reusing materials to manufacture new products. With its help, we can preserve natural resources, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and save energy. And did you know that recycling also creates jobs and supports the economy? If you want to delve into this exciting topic in your...

Expository writing, as the name suggests, involves presenting factual information. It aims to educate readers rather than entertain or persuade them. Examples of expository writing include scholarly articles, textbook pages, news reports, and instructional guides. Therefore, it may seem challenging to students who are used to writing persuasive and argumentative...

Expository or informative essays are academic papers presenting objective explanations of a specific subject with facts and evidence. These essays prioritize balanced views over personal opinions, aiming to inform readers without imposing the writer’s perspective. Informative essays are widely assigned to students across various academic levels and can cover various...

Thanks for these ideas for essays on World War II. These are what I need for my paper about WWII. Now I can start writing my essay on World War II.

To write World War II essays is very instructive – to know the reasons, the course of war events, the results. These all are necessary to comprehend and debar World War III as humanity won’t go through it!

The World War II: Impact and Consequences Essay

World War II had a great impact on social order and international relations between the nations and continents. A major influence on international policies was the relations between the two opposite camps, the Allies and the Axis, and the views each held of the other. The Allies and the Axis were reluctant to follow any line that risked running into the antagonism of the other for fear of alienating their ally and therefore endangering one of the precepts of their distant policies (Gordon 32). In an epoch of growing international anxiety and doubt, Germany remained one of the few relatively sure supports upon which they could depend on. Certainly, in the formulation and conduct of international war policy the significance attached to the views and position of the other was considerable, indeed the contacts and discussions between them were often decisive. The history of World War II suggests that the greatest impact this war had in African and Asian countries was through the processes of decolonization and modernization coming to these geographical regions.

World War II changed the landscape of North Africa and opened new opportunities for independence. The countries became independent immediately after the end of the war, but the war changed the national consciousness and self-determination of the nations. For either to be successful the cooperation of their partner across North Africa was considered imperative. Neither the Allies nor the Axis was prepared to take any initiative alone: among diplomatic, military and political circles there was a refusal to act either against Italian hostility in North Africa or German treaty violations in Europe without the guaranteed support of their partner (Hargreaves 65). This perceived incapability to operate without the backing of the other extended at several vital junctures to the point where the Allies and the Axis allowed the other, possibly willingly so, to determine their own policies (Gordon 65).

The main African countries involved in World War II were under Italian rule and included the Italian North Africa, the Italian east Africa. Also, such Asian Middle East countries as Iran, Syria and Lebanon were involved. The outcome this emphasis placed on the other’s strategy was to strengthen the case for appeasing Italy and Germany. Each was depressed from taking a firm posture by the belief that the other was not committed to a policy of confrontation. During the first months of World War II, the countries recognized that, whatever their public statements, the British were not committed to a hard line over Italian hostility (Hargreaves 77). Later, following the reoccupation of the Africa, a similar sight was held in London of French attitudes. Equally important, each knew, indeed it was explicitly stated, that their ally would not act without them and without having first received a formal promise of their support. The Allies and the Axis pacification policies were further reinforced by the denial to accept a trade-off by which support for a policy of resistance against one fascist aggressor would be exchanged for the promise of support against the other (McGowen 87). The only result of these political maneuvers was to further damage their relations, with each berating the other for failing to provide the necessary support. In fact, these often hurtful exchanges had more to do with seeking to place the onus for (in)action onto their ally’s shoulders than with any wish to adopt a policy of resistance towards fascist hostility (Gordon 63). “Between Cairo and Cape Town operational activities were at first confined to a few ports and airfields. Freetown, an important staging-post and assembly-point for naval convoys, was quickly affected” (Hargreaves 51). The outcomes drawn from these common considerations, firstly, that it was impossible to act without the backing of their ally and, secondly, that their union was no more than half- hearted in its desire to oppose Italy or Germany (and also that they lacked the means even if they had desired to accept such a policy), accentuated their already unsure policies, impeded any firm answer, and acted as a further impetus to the policies of appeasement.

When considering the African and Asian responses to Italian hostility in East Africa, a contrast has been made between ‘the complicated “game” and the determination of the English Government; of a strong-willed British administration wanting to do all it could to halt Italy and defend the League but being held back by the cynical policies of the French (Hargreaves 66). The obvious contradiction with France’s traditional record of determination in upholding the settlement and the League, and with Great Britain’s previous half-hearted and flexible approach towards both, is explained away by a supposed dual volte-face in which each at the same time assumed the mantle of the other. This actually rapid and total about-turn in policy simply cannot explain the complexity of the Allies and the Axis policies. For both there were numerous issues to be taken into account, some pushing towards opposition to the Axis ambitions and defense, others towards maintaining Italian friendship through acceptance of her expansion at Africa’s expense. Although these were not felt equally, there were strong cases made on either side of the dispute in both countries (McGowen 34). In their respective parliaments, governments and public views the war crisis produced widely divergent, and often contradictory, opinions towards the Axis. The result was that neither was firmly attached either to opposing or conniving at Italian hostility. For the Allies and the Axis leaders the importance of the Africa crisis, coming at a critical time in international affairs, lay in its repercussions beyond Africa – in the Mediterranean, in Europe, and above all in their future relations with Germany (Gordon 49). Not surprisingly, their opinion turned as much towards Berlin as towards Rome, Addis Ababa or Geneva throughout the whole affair. Faced with growing evils in Europe, complicated by an expansionist Japan in the Far East, the significance of Italy greatly increased. With Germany rearming and clearly seeking to expand to the African and Asian continents and east the value of Italian support could not be overlooked. The result was an effort, led by the French but closely followed and supported by London, to tie Italy more closely to the western camp. “Political doctrines apart, all France’s African subjects suffered new hardships in consequence of the interruption of peacetime patterns of production and trade, and of increased demands by their rulers” (Hargreaves 53).

Not only was there a concern not to estrange their union and to keep as close to them as possible but both the Allies and the Axis also considered that their own policy could not be successful without the fuIl and active participation of each other. This refusal to operate outside a joint Allies approach acted throughout the crisis as a restraint on the policy initiatives that emerged from the Allies and the Axis whether they were for greater concessions or stronger coercive measures. Although for Great Britain the issue was less one of dependence there was still a great emphasis placed on Paris (McGowen 65). This was certainly much in evidence when consideration was given to the issue of sanctions. The issue of French military support should Italy attack the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean in some ‘mad dog’ attack was repeatedly raised. Equally, there was a general insistence that France should prepare fuIl-scale armed operations against Italy before sanctions could even be considered, and any policy of opposing Italian ambitions was simply considered impossible without the full military and diplomatic support of the French (Gordon 69). The war in Asia took place between Japanese and communist Chinese armies aimed to protect their national interest and became independent.

Time and again the Allies pointed to failure to provide this as a reason for their own unwillingness to consider sanctions. At the same time they insisted on the necessity of keeping in step with France and made this principle of their policy clear to all involved. British statements that they had no understanding with African countries, their demands that before sanctions were apprised upon France must be prepared to undertake large-scale military operations (in fact, take the brunt of these as well as from any Italian retaliation) and their refusal to offer in exchange for French support over Africa a guarantee of British support for future sanctions against Germany, only added to the general suspicion in Paris (Hargreaves 74). British demands that a sanctions policy be adopted, and moreover that it be led by France, met with little support (McGowen 48). French leaders, aware of British silence on this issue, saw no reason to do anything other than drag their heels – certainly they often argued that London would be only too pleased if sanctions were avoided.

Similar to Africa, Asia was intestinally involved in the war with poor military resources and colonial state power. It has been argued that the crisis posed a straightforward, if awkward, choice for the Allies and the Axis between resistance and appeasement, between threats (backed up if necessary by collective action) and sufficient concessions to Italy to prevent her from resorting to arms combined with pressure on the Asians to concede. In this the choice that confronted Paris and London over Asian nations reflected the wider and longer-term choice over policy towards the fascist powers. The choice was not, though, so simple. The recognized pattern of appeasing Mussolini and the desire to preserve the advantages of Italian friendship pushed them in one way; concern for the League and for the widespread public support it enjoyed pushed them in another (McGowen 65). Neither Government, though, saw the option in such stark terms. For both it was an issue of attempting to balance the many demands placed on them. Nor were conciliation and coercion considered as being equally exclusive but rather as two paths to be followed simultaneously. Both the Allies and the Axis were pushed towards what were often incompatible options by conflicting advice and concerns. The understandable inclination was to seek to avoid these alternatives, to preserve both Italian co-operation in Europe and the prestige and force of the League; neither France nor Great Britain accepted that by attempting to keep both they would fall between two stools (Gordon 77). The World War II led to formation of Asian states including the Republic of China (under Communist regime,) The North and South Korea, the Taiwan, and Vietnam. The decolonization process touched Indochina, Algeria, Indonesia and Madagascar, the dominion of India and Pakistan. Such states as Israel and Palestine were created in the Middle East.

The story of the Allies and the Axis policies towards the African and Asian countries is in large part that of how the Governments sought to come to terms with this dilemma. Neither saw a simple choice between coercion and conciliation and in neither country was the eventual outcome of the debate a clear decision either to resist or to cede to Italian demands. When faced with the threat and then the fact of Italian hostility against a fellow member of the League both France and Great Britain worked fervently to find a diplomatic solution (Hock 101). The central, seemingly insoluble, problem remained how this could satisfy both the League and Italy; how Italian needs could be sufficiently fulfilled to keep her in the anti-German camp while not delivering a fatal blow to the League and to the system of collective security. Such hopes proved to be based on an unfounded optimism or, more probably, on an irresolution characteristic of both countries’ leaderships. At the heart of British and French policies lay what were to prove intractable problems arising from inherent inconsistencies (McGowen 51). Furthermore, however understandable the policies pursued, they were always poorly adapted to the nature of Mussolini’s power. Given this, it is not surprising that their open rejection of effectual sanctions and their public acceptance of Italy’s need to expand did little to convince Mussolini of the need to accept anything less than the complete annihilation of North Africa. This gulf between fascist Italy and the democracies always worked against a successful resolution of the crisis along the lines envisaged in the Allies and the Axis. The weaknesses inherent in such an approach and the basic incompatibility of the two halves of the dual-line were never fully accepted by the Allies and the Axis policy-makers (Gordon 88).

Pushed in often opposite directions by various international and domestic considerations, the Allies and the Axis policies in Asia and Africa were equally ambivalent. The first inclination for both was to temporize, to leave the problem to others, to urge conciliation all round and to attempt to avoid the awkward dilemma posed by Italy’s hostility (Hock 103). Driven by conflicting advice, interests and considerations, weakened in their formulation by the absence of decisive leadership and in their application both by material weaknesses and the lack of Anglo-French solidarity, ended in failure: the League was ruined as an instrument of peace-keeping, the Italian alliance permanently damaged and mutual relations strained almost to breaking point. “The secretary of state entered 1941 certain that he wanted no confrontation with Japan over China or Southeast Asia until the situation in Europe had improved” (Lee 14).

Having unsuccessfully turned to each other for a lead, ministers and their military advisers looked to Great Britain for a way out of their predicament. Safe in the knowledge that British opposition would rule out any military response, the new direction was instructed to open talks under the auspices of the League. The crisis was, however, far from over (Hock 107). The importance of Asian theater was that for the Allies, all hopes of improving relations with Germany were dependent on one thing – the support of France. Everything turned on first neutralizing any French demands for action and then winning her over to the appeasement of Europe. For the Government in London the present dangers, and future possibilities, all revolved around an agreement with Paris. Both approached the events from this same sense of weakness (McGowen 38). Attempts to look to other allies (in the case of France to Poland, the Little Entente, the Soviet Union and Italy; for Great Britain to her Dominions) never got off the ground. Faced with growing threats in Europe, the Mediterranean and North Africa, Great Britain had to abandon her inclination to be the arbiter of Europe (Hock 106).

Their immediate reactions, however, were often to condemn their partner as much as the aggressor. The French attacked what they regarded as Great Britain’s lack of solidarity, their failure to provide adequate commitments to the defense of Western Europe, and for playing too much to a German tune. They also questioned the inconsistency with which the British sought to apply the Covenant against Italy while denying its value in Europe. In London French intransigence was blamed for the long-lasting failure to reach a settlement with Germany (McGowen 23). The inherent issues in relations between Britain and France in Asia were heightened by the fact that before either reached a policy decision the other’s attitude was solicited and, despite a pronounced lack of confidence, their support made an essential precondition for any diplomatic move (Kelly 81). Throughout both crises each constantly referred to the attitudes of other actors. In turn, the League, the United States, France’s Eastern European allies, British Dominions, and numerous other states as far apart as Turkey and Japan, were considered in policy deliberations. What really mattered, however, was the attitude of their partner across the Channel. Beyond the limitations imposed by material resources and the broad outlook and aims of the two leaderships, it was these considerations that each gave to the other’s position that was the major determinant of international policy (McGowen 87).

In Asia and Africa, the Allies relations were marked by requests and refusals for action against international hostility: British attempts to halt Italian ambitions in Ethiopia were blocked by French unwillingness to follow their lead; over the Asia the roles were apparently reversed, with Great Britain’s non-co-operation holding back the French. In both cases there is much in this that is simply myth. The myth, however, both at the time and since, proved to be remarkably useful. Consequently it took deep root (McGowen 47). That the Allies tensions were added to by these diplomatic exchanges is evident. Over the crisis the British disapproval of the French failure to stand by them was strongly voiced. In return, Paris attacked what many there considered to be Great Britain’s willingness to raise the stakes to dangerous levels.

Those successes offered twin rescue to a beleaguered Imperial Army. First, the colossal drain of the China “incident” might at last be ended by an occupation of French Indochina that would nearly sever the remaining flow of Western aid to Chiang Kai-shek. It was a perversion of the “total war” officers’ original attempt to achieve autarky (Lee 16).

In both cases these connections had a direct and lasting collision. In large part these divergences make clear the failure to overcome either crisis successfully (McGowen 54; McGowen 66).

In sum, African countries and Asian nations were the stronger partners is beyond doubt. The greater reliance of the Allies on ally was shown in the frequent use made of the unequal relations. None the less, the Allies retained a clear edge of political maneuver and took its own part in the policy of pacification. The direct insinuation of their recognized interdependence was a refusal to maneuver in the political arena outside the boundaries of what was jointly agreed and applied. World War II proposed great opportunities for Asian and African nations to become independent but it also ruined their cultural and social achievements. Their interdependence also meant that the world’s powers chose to bow to the other’s position. Critics told that the world’s powers would adjust their position to that of dependent nations. This is a mistaken impression and expression. The debate constantly placed Asian nations at the centre of their decisions and any action to resolve the war crisis, either along the path of further concessions or greater pressure on the Axis, was based on winning co-operation.

Works Cited

Gordon, J. W. The Other Desert War: British Special Forces in North Africa , 1940-1943 Greenwood Press, 1987.

Hargreaves, J.D. Decolonization in Africa ; Longman, 1996.

Hock, D. Legacies of World War II in South and East Asia . Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2007.

Kelly, O. Meeting the Fox: The Allied Invasion of Africa, from Operation Torch to Kasserine Pass to Victory in Tunisia . Wiley, 2002.

Lee, L.E. World War II in Asia and the Pacific and the War’s aftermath, with General Themes: A Handbook of Literature and Research . Greenwood Press, 1998.

McGowen, T. World War II. Childrens Press, 2002.

- Wartime Conferences of World War II

- Promoting Production During World War II

- Causes of World War II

- Female Russian Snipers: From Second World War to Present Day

- World War II and Germany’s Invasion Plans

- The Battle of Iwo Jima: Peter Chen and Cyril O’Brien Points of View

- Experience and Perspective Amphibious Operations

- Investigation of War Causes Between the USA and Japan

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, December 7). The World War II: Impact and Consequences. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-world-war-ii-the-impact-and-consequences/

"The World War II: Impact and Consequences." IvyPanda , 7 Dec. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/the-world-war-ii-the-impact-and-consequences/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'The World War II: Impact and Consequences'. 7 December.

IvyPanda . 2021. "The World War II: Impact and Consequences." December 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-world-war-ii-the-impact-and-consequences/.

1. IvyPanda . "The World War II: Impact and Consequences." December 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-world-war-ii-the-impact-and-consequences/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The World War II: Impact and Consequences." December 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-world-war-ii-the-impact-and-consequences/.

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Understanding the Scope of World War 2

World War 2 wasn’t just a series of battles. It was a global phenomenon that reshaped nations, cultures, and the very fabric of human civilization. To fully grasp the magnitude of this war, students must appreciate the broader picture— from the major events to the aftereffects that ripple into today’s geopolitics.

World War 2 wasn’t just a series of battles or mere dates in history textbooks; it was a transformative epoch that shifted the 20th century. It was a global phenomenon that reshaped nations, cultures, and the very fabric of human civilization.

The stories from the frontlines, while pivotal, are just one dimension. From the intense political maneuvers and espionage missions to the socio-cultural transformations that ensued, there’s an ocean of World War 2 topics to explore.

In my experience, many students get so engrossed in the prominent WW2 research topics that they sometimes overlook the profound societal and technological shifts. The war expedited technological advancements, leading to innovations and even the space race.

Choosing the Right Topic for WW2 Research Paper

The first and perhaps most crucial step is selecting your focus. While there are countless World War 2 consequences topics to explore, choosing one that genuinely piques your interest is essential. From the intricacies of military strategies to the socio-cultural impacts, every WW2 topic offers a unique perspective. According to general IB criteria, aligning your genuine interests with academic standards often yields the best results.

Going Thorough Research for WW2 Research Paper

As I know, thorough research forms the backbone of any compelling research paper. Primary sources, firsthand accounts, and authentic records give a factual foundation. On the other hand, secondary sources provide analysis and interpretation. Be sure to frame some pertinent research questions about World War 2 to guide your exploration.

The list of similar articles:

Essay on Military Leadership

Veterans Essay Ideas

Veterans Day Essay Tips & Tricks

Military Topics for Research Paper

How to write an essay on army values, making a strong thesis statement for ww2 research paper.

Every IB student understands the weight of a robust thesis statement. Your thesis should reflect your chosen WW2 research topic and provide a fresh viewpoint. For instance, if your focus is on WW2 project topics related to technological advancements, your thesis might revolve around how these innovations changed the course of battles.

Structuring World War 2 Research Paper

A clear structure is paramount. Start with an engaging introduction where you present your World War 2 research topic. In the body, dissect key events, figures, or consequences in detail. And in conclusion, tie all your findings together, highlighting the broader implications.

Revising and Proofreading World War 2 Research Paper

As any seasoned writer would advise, revisiting your work with fresh eyes can make a difference. It ensures factual accuracy, logical flow, and overall coherence.

Top WW2 Research Paper Topics to Consider

Drawing from my extensive background in the subject, and with a little help from our team of expert History essay writers , here are some intriguing topics to ignite your curiosity:

- Military Strategies & Tactics: The Art of War.

- The Political Landscape: Alliances and Treacheries.

- Women in WW2: Beyond the Home Front.

- Technology’s Role: From Enigma to the Atomic Bomb.

- The War’s Aftermath: The Dawn of the Cold War.

- WW2’s Influence on Modern Pop Culture.

- Propaganda’s Power: How Nations Were Moved.

- World War II’s Unsung Heroes.

- The Evolution of Warfare: Comparing WWI and WWII.

- The Human Cost: Stories Beyond the Battlefield.

- The Home Front: Mobilizing Industries and Morale.

- Resistance Movements: The Underground War. Tales of bravery from resistance fighters across Europe.

- The Holocaust: The Darkest Chapter. The most harrowing part of WW2.

- World War 2 and the Global Economy. Economic shifts and consequences that laid the foundation for today’s economic order.

- Naval Warfare: The Battle of the Seas. Understand the strategic importance of naval dominance.

- Intelligence and Espionage: Secrets of the War. Stories of spies, their tactics, and their role in the war.

- Asian Theatre: Japan’s Expansion and its Impact. Delving into the Pacific battles and Japan’s wartime strategy.

- The African Front: The War Beyond Europe’s Borders. Exploring the lesser-known battlegrounds.

- Children of the War: Youth Amidst Conflict. The tales of the youngest affected by the war.

- Medical Advancements and Challenges. How did medicine evolve in the cauldron of WW2?

- Prisoners of War: Life in Captivity. Personal accounts of soldiers taken captive.

- Aerial Battles: Dominance in the Skies. Chronicling key air battles and their significance.

- The Role of Artists and Writers in WW2. How did creatives contribute to the war effort?

- Allied Powers: Dynamics and Differences. Delving into the unity and tensions between allies.

- Decoding War Communications. Understanding wartime coding and the significance of breaking them.

Each of these topics not only represents an interesting WW2 topic but can lead to a nuanced understanding of the broader historical context. The depth and breadth of World War II offer countless avenues for study, and these topics are just the tip of the iceberg.

World War II remains an inexhaustible reservoir of research topics ripe for exploration. Tapping into this rich tapestry of events, characters, and consequences is more than just an academic exercise. It’s a journey into understanding the human spirit, resilience, and the complexities of global geopolitics. If ever you find yourself lost amidst the vast topics about World War 2, remember: it’s about finding a unique voice in the vast chorus of history.

In all other cases at Writing Metier , there is a team of writers who can help with World War 2 research papers . And always, always keep your passion for learning alive.

Free topic suggestions

Laura Orta is an avid author on Writing Metier's blog. Before embarking on her writing career, she practiced media law in one of the local media. Aside from writing, she works as a private tutor to help students with their academic needs. Laura and her husband share their home near the ocean in northern Portugal with two extraordinary boys and a lifetime collection of books.

Similar posts

Military essay topics.

Discover an Array of Engaging Military Essay Topics that will Ignite Your Curiosity

What is a Military Essay? Types, format and structure