Meet Dr. Giovanni Aldini — The Man Whose Experiments Inspired ‘Frankenstein’

The disturbed dr. victor frankenstein had his real-life roots in dr. giovanni aldini..

Wikimedia Commons Dr. Giovanni Aldini

When Giovanni Aldini was a child, he would watch his uncle, Dr. Luigi Galvani, perform experiments.

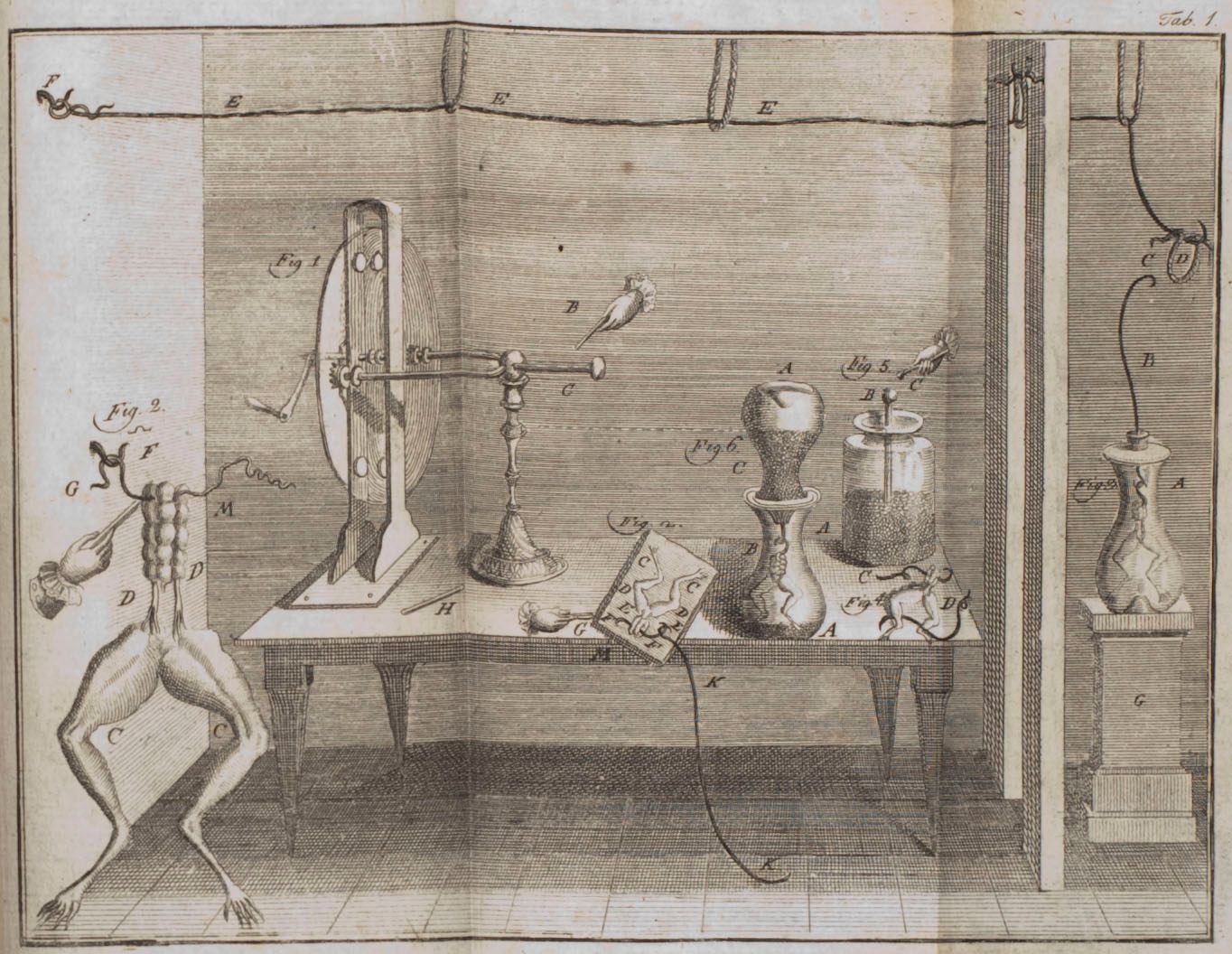

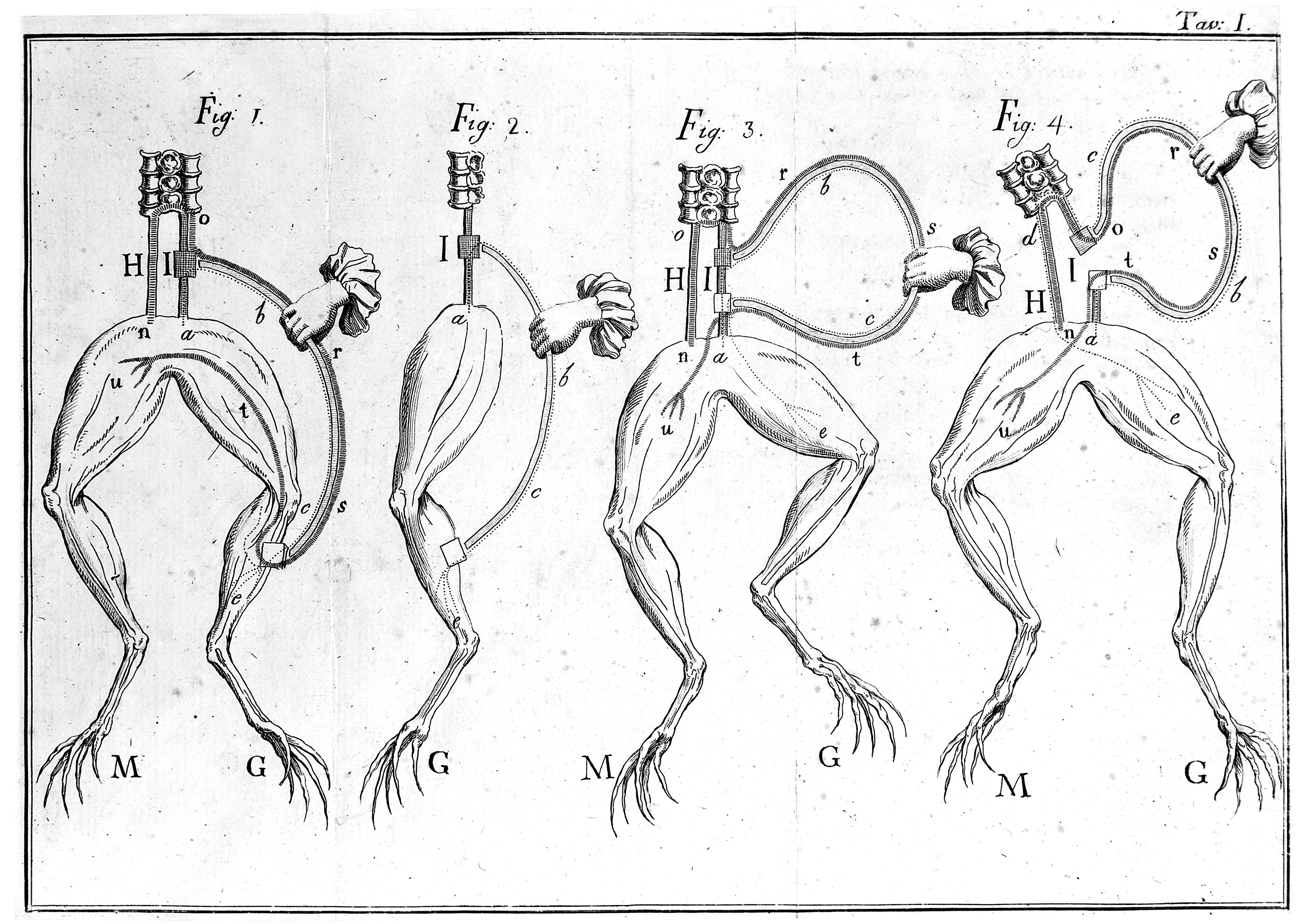

For more than ten years, Dr. Luigi Galvani had devoted his studies to frogs. Specifically, dead frogs. He had studied the way that the legs of the unfortunate amphibians were connected, and realized that if stimulated with an electrical current, they twitched. Furthermore, he believed that if he stimulated the fluid that connected the nerves to the entire body, he could reverse the effects of death.

In short, Luigi Galvani believed he could raise the dead with electricity.

After watching his uncle perform these macabre experiments, it was no surprise that Giovanni Aldini would go into the same field. After studying at the University of Bologna, he followed in his uncle’s footsteps and began experimenting with reanimating dead frogs. However, upon his uncle’s death, Aldini began to crave something different, something more exciting.

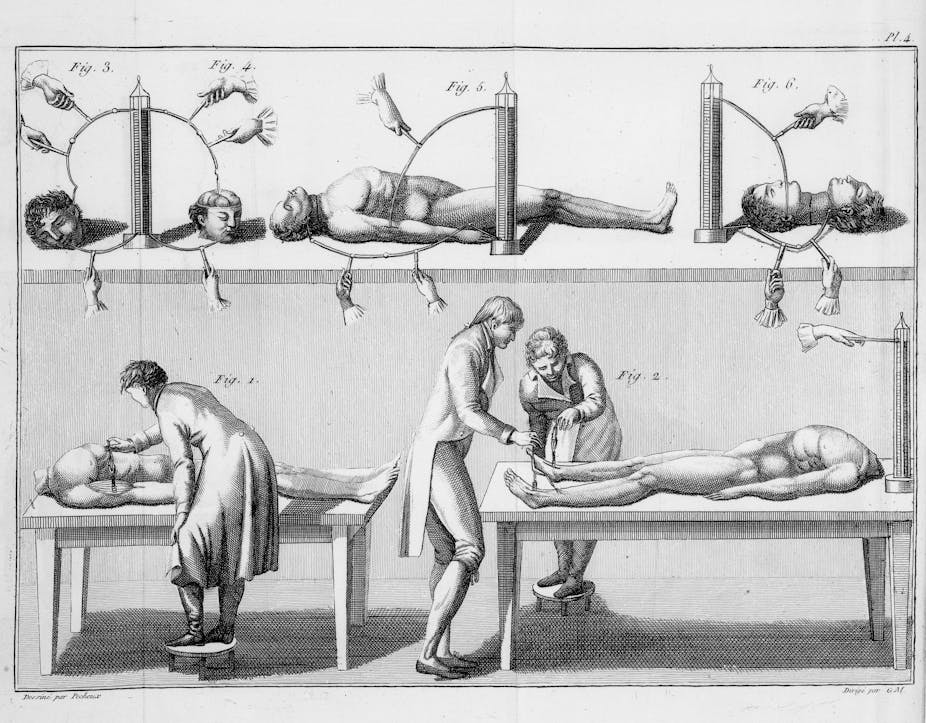

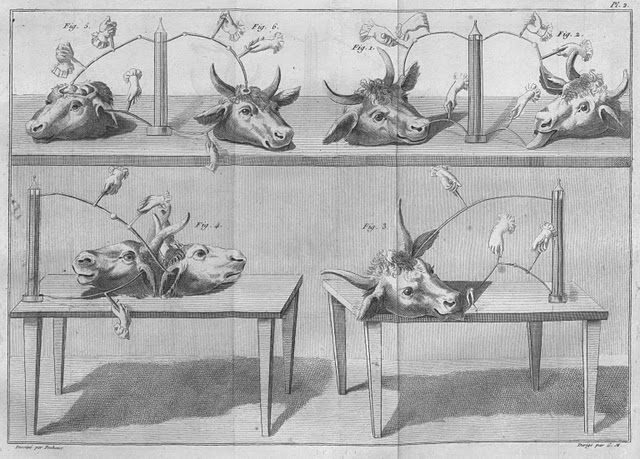

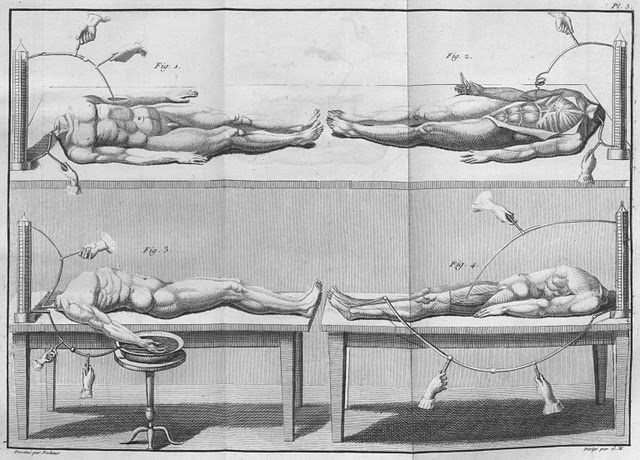

He began performing the same experiments as his uncle had on frogs, on larger animals, with more sophisticated nervous systems. Soon, Aldini was drawing crowds to his laboratory as he attempted to reanimate sheep, pigs, cows, and oxen.

For the most part, Giovanni Aldini was successful. As he applied electrical impulses to the corpses using a battery, the animals’ heads would shake from side to side, their eyeballs would roll, and their tongues would roll out of their mouths. Before long, attending one of these gruesome performances became all the rage.

However, Aldini soon grew bored of his experiments. He felt that he had achieved all he could with the bodies of dead animals and that they were no longer stimulating enough for him.

Wikimedia Commons Aldini performing experiments on an oxen.

So, of course, the natural progression was to move on to humans.

In the early 1800s in Italy, procuring a recently dead body was much easier than it is today. To find subjects for his experiments, Aldini simply headed over to Piazza Maggiore, and wait for the executioner to behead his next victim.

Aldini soon realized, though, that the solution to finding his bodies also presented a problem. The beheaded bodies were often drained of blood, and without blood in the veins, the electrical impulses had nothing to travel through. His battery was useless against a headless corpse.

However, there was a light at the end of the tunnel. While Italy executed their criminals by beheading, England still used the gallows. So, Aldini did what any self-respecting medieval doctor would do, and traveled to London, where he ordered one freshly hanged criminal to be delivered to the Royal College of Surgeons.

The body was that of George Foster, who, though he had enjoyed a life of relative anonymity, would soon become one of London’s most talked about dead men. Almost immediately upon his arrival at the Royal College, Aldini attached the probes to Foster’s body and powered up the battery.

Aldini left the probe connected for hours, and through it, all, the crowd that had gathered watched with bated breath as his jaw quivered, his facial muscles contorted and his left eye opened.

At one point, Foster’s corpse even appeared to inhale.

Wikimedia Commons Mary Shelley

Eventually, Aldini’s battery died, and along with it Foster — this time for good. Though Aldini considered his experiment a failure, as Foster had ultimately failed to return to life, the doctors who had witnessed it considered it a miracle.

News quickly spread of Aldini’s feat, how he had opened an eye, and maybe even breathed. And, as with every story, the tale became exaggerated. By the time it had reached the ears of little Mary Shelley, the daughter of a friend of Dr. Giovanni Aldini’s, the tale had grown to include Foster’s arms lifting and his head spinning.

Though Aldini may not have fully thought through the consequences of his work, or even continued trying to reanimate the dead, little Mary Shelley took it to heart, and later drew inspiration from the tale she’d heard as a child when she sat down to write a book.

Her titular character, Dr. Victor Frankenstein, bears a striking resemblance to Giovanni Aldini, in his mannerisms and his intentions. However, the resemblance, thankfully, ends there, as there’s no telling what George Foster may have done had Aldini’s battery been successful.

Next, meet the man who inspired the tale of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde . Then, read about other legends that were inspired by real-life horror stories .

PO Box 24091 Brooklyn, NY 11202-4091

- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

Giovanni Aldini: This Real-Life Dr. Frankenstein Electrified the Dead

The idea that electricity could be used to jumpstart life doesn't just come from fiction. like dr. frankenstein, aldini's grisly experiments sought to prove that it's possible to revive the dead..

On a frosty day in January 1803, George Forster was executed at Newgate Prison for the supposed drowning of his wife and daughter — and his body was left hanging in temperatures two degrees below freezing for two hours afterwards. Perfectly chilled, he was hastily carted the mile long journey to London’s Royal College of Surgeons’ anatomy theater.

Inside, the room was a see-and-be-seen event, says science historian Iwan Morus. The oval theater was packed with British scientists, dignitaries and doctors, all eyes focused on a wooden slab covered by Forster’s body. At the helm was 40-year-old Giovanni Aldini, a man on a mission, says Morus. “He’d spent most of the last decade working to exonerate his uncle, the great Luigi Galvani,” Morus adds, explaining that Galvani had been dismissed from the faculty at the University of Bologna for refusing to swear allegiance to Napoleon. After losing his position, he died penniless a year later.

According to enlightenment historian Thomas Broman, electrification — the process of charging something with electricity — was already a fad in Europe, particularly in 18th century salons, a prominent gathering place for intellectuals at the time. But it was in that theater that Aldini sought to prove his uncle’s theory of galvanism, or the medical use of electricity to stimulate nerves and muscles. The theory, says Broman, held that “electricity flowed from the brain and supplied the body with vital force.” Galvini himself referred to the phenomenon as " animal electricity ," believing it was a distinct form of energy.

In short, by charging Forster's corpse with direct electrical current, Aldini hoped to proved that electricity in the body did not end with death — and could even be used to revive the deceased.

An Electric Event

Forster, the other star of the main event, was an unwitting (if not potentially innocent) bystander, says Morus. The evidence against him was all circumstantial . No one saw him plunge his wife and daughter into London’s Paddington Canal. Unlike the guillotines of France, Forster would keep his head at execution, but there was no guarantee after death.

While Forster may have been a victim, Aldini certainly didn’t see himself that way. He’d risked at lot be here. With the French Revolution still in the backdrop, it was a dangerous time to be alive. Morus described Aldini as a “nonconformist” in opposition to the church. The theory of animal electricity would have been antithetical to religion because it meant that human potential wasn’t controlled by the soul. And for reasons like these, “Aldini likely would have lived on the edges of polite political society,” he says.

Aldini thought little of the bodies he attempted to revive, often those of executed criminals or people from the fringes of society, says Morus. Historian Helen MacDonald writes that Aldini loved “to make the dead perform tricks.” Further, Aldini commended so-called "enlightened laws" in England that allowed criminals to atone for their crimes after execution by becoming subjects of experimentation, writes MacDonald .

The crowd cooed with enthusiasm as Aldini applied electrical rods to Forster’s body. They watched in awe as “his jaw quivered, his left eye opened, and his face convulsed.” Eight hours of experimentation followed — the climax came when electric arcs were attached to Forster’s ear and rectum and “the resulting muscular contractions [gave] an appearance of reanimation.” Eventually, the battery died. Aldini would later describe the event in his book, An Account of the Late Improvements in Galvanism . Ultimately, he considered the experiment a failure, as Forster hadn't sprung back to life, but doctors who witnessed the event say they considered it a miracle.

Animal Electricity: Fact or Fiction?

Animal electricity proved to be only partially true. While the muscles of humans and animals contract due to electricity, that same vital force does not come from the brain. “While electrical force might twitch muscles, it cannot revive the dead," says Broman.

Aldini’s work would also predate other forms of electrification. Electroshock therapy or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), for example, was invented in the 1930s by an Italian psychiatrist named Laszló Meduna to relieve symptoms of depression. And although ECT has remained deeply controversial, research has also shown that it provides some patients with great relief.

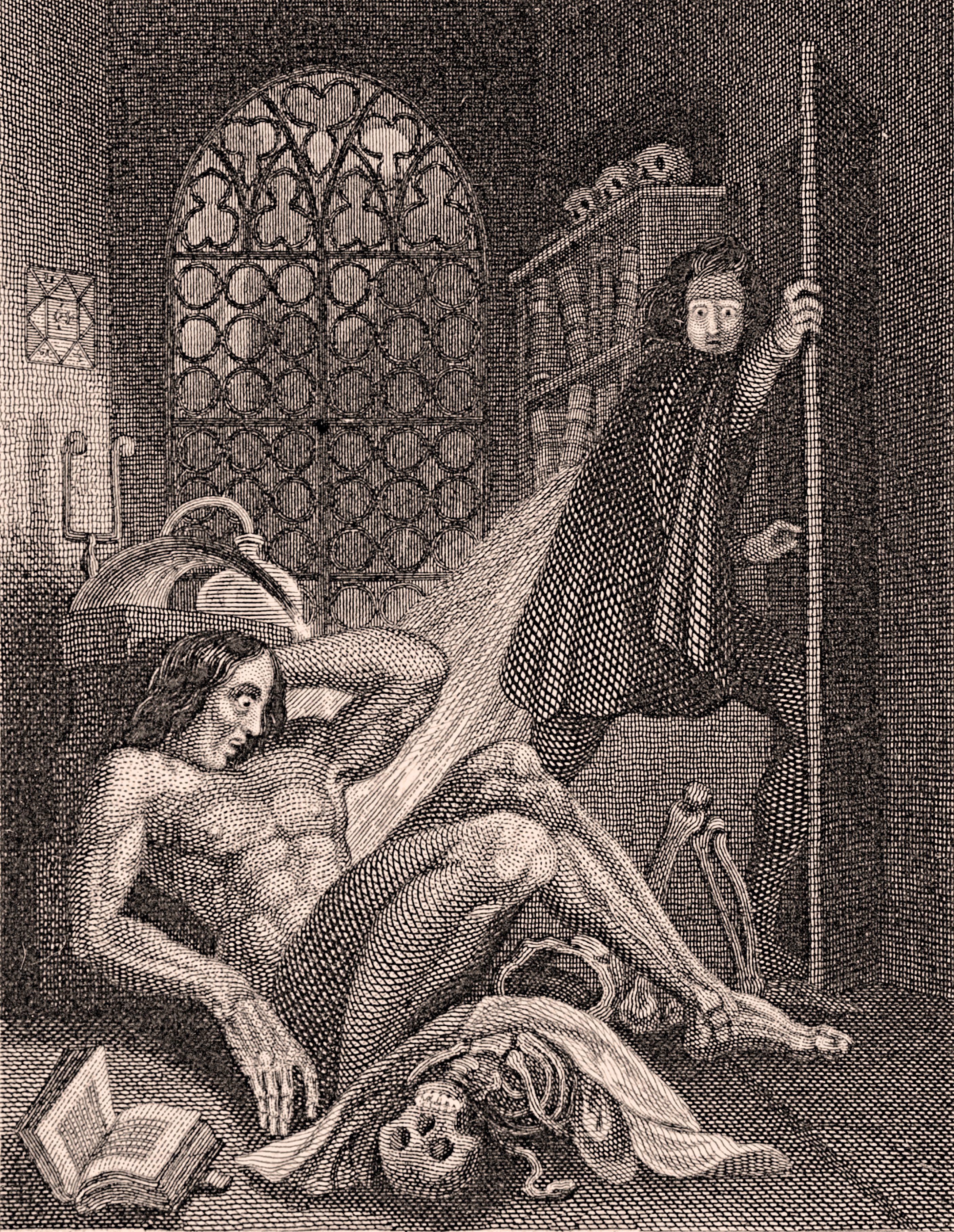

But perhaps most famously, Aldini also inspired the work of author Mary Shelley . In the preface of her novel Frankenstein , she wrote that galvanism had proven that life could be revived. As Shelley began to write Frankenstein in 1816, she might have been picturing that same anatomy theater where Forster was put on display.

Shelley was, after all, no stranger to death. At just 20 years old, as a young wife, she had already lost a child and had her half sister commit suicide. Maybe she dreamed of reviving those lost, but whatever the reason, Shelley would later pen the preface of her groundbreaking novel with a note that highlighted the ultimate promise of Galvani and Aldini’s work: “Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated."

- behavior & society

Already a subscriber?

Register or Log In

Keep reading for as low as $1.99!

Sign up for our weekly science updates.

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Giovanni Aldini: from animal electricity to human brain stimulation

Affiliation.

- 1 Centre de Recherche Université Laval Robert-Giffard, Beauport, Québec, Canada.

- PMID: 15595271

- DOI: 10.1017/s0317167100003851

Two hundred years ago, Giovanni Aldini published a highly influential book that reported experiments in which the principles of Luigi Galvani (animal electricity) and Alessandro Volta (bimetallic electricity) were used together for the first time. Aldini was born in Bologna in 1762 and graduated in physics at the University of his native town in 1782. As nephew and assistant of Galvani, he actively participated in a series of crucial experiments with frog's muscles that led to the idea that electricity was the long-sought vital force coursing from brain to muscles. Aldini became professor of experimental physics at the University of Bologna in 1798. He traveled extensively throughout Europe, spending much time defending the concept of his discreet uncle against the incessant attacks of Volta, who did not believe in animal electricity. Aldini used Volta's bimetallic pile to apply electric current to dismembered bodies of animals and humans; these spectacular galvanic reanimation experiments made a strong and enduring impression on his contemporaries. Aldini also treated patients with personality disorders and reported complete rehabilitation following transcranial administration of electric current. Aldini's work laid the ground for the development of various forms of electrotherapy that were heavily used later in the 19th century. Even today, deep brain stimulation, a procedure currently employed to relieve patients with motor or behavioral disorders, owes much to Aldini and galvanism. In recognition of his merits, Aldini was made a knight of the Iron Crown and a councillor of state at Milan, where he died in 1834.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Electrotherapy for melancholia: the pioneering contributions of Benjamin Franklin and Giovanni Aldini. Bolwig TG, Fink M. Bolwig TG, et al. J ECT. 2009 Mar;25(1):15-8. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e318191b6e3. J ECT. 2009. PMID: 19209070

- Giovanni Aldini and his contributions to non-invasive brain stimulation. ArÊas FZDS, ArÊas GPT, Moll Neto R. ArÊas FZDS, et al. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2020 Nov;78(11):733-735. doi: 10.1590/0004-282X20200080. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2020. PMID: 33263639

- Resuscitation great. Luigi Galvani and the foundations of electrophysiology. Cajavilca C, Varon J, Sternbach GL. Cajavilca C, et al. Resuscitation. 2009 Feb;80(2):159-62. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.09.020. Epub 2008 Dec 6. Resuscitation. 2009. PMID: 19059693

- Animal electricity from Bologna to Boston. Goldensohn ES. Goldensohn ES. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998 Feb;106(2):94-100. doi: 10.1016/s0013-4694(97)00110-7. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998. PMID: 9741768 Review.

- Surgical Techniques for Chronic Implantation of Microwire Arrays in Rodents and Primates. Oliveira LMO, Dimitrov D. Oliveira LMO, et al. In: Nicolelis MAL, editor. Methods for Neural Ensemble Recordings. 2nd edition. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2008. Chapter 2. In: Nicolelis MAL, editor. Methods for Neural Ensemble Recordings. 2nd edition. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2008. Chapter 2. PMID: 21204444 Free Books & Documents. Review.

- Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) in Major Depression. Breda V, Freire R. Breda V, et al. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2024;1456:145-159. doi: 10.1007/978-981-97-4402-2_8. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2024. PMID: 39261428 Review.

- Therapeutic potential of brain stimulation techniques in the treatment of mental, psychiatric, and cognitive disorders. Camacho-Conde JA, Del Rosario Gonzalez-Bermudez M, Carretero-Rey M, Khan ZU. Camacho-Conde JA, et al. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2023 Jan;29(1):8-23. doi: 10.1111/cns.13971. Epub 2022 Oct 13. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2023. PMID: 36229994 Free PMC article. Review.

- Influencing Human Behavior with Noninvasive Brain Stimulation: Direct Human Brain Manipulation Revisited. Fecteau S. Fecteau S. Neuroscientist. 2023 Jun;29(3):317-331. doi: 10.1177/10738584211067744. Epub 2022 Jan 20. Neuroscientist. 2023. PMID: 35057668 Free PMC article. Review.

- A Brief History of Cerebellar Neurostimulation. Ponce GV, Klaus J, Schutter DJLG. Ponce GV, et al. Cerebellum. 2022 Aug;21(4):715-730. doi: 10.1007/s12311-021-01310-2. Epub 2021 Aug 17. Cerebellum. 2022. PMID: 34403075 Free PMC article. Review.

- Deep Brain Stimulation for Alzheimer's Disease: Stimulation Parameters and Potential Mechanisms of Action. Luo Y, Sun Y, Tian X, Zheng X, Wang X, Li W, Wu X, Shu B, Hou W. Luo Y, et al. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021 Mar 11;13:619543. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.619543. eCollection 2021. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021. PMID: 33776742 Free PMC article. Review.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Personal name as subject

Related information.

- Cited in Books

LinkOut - more resources

Other literature sources.

- The Lens - Patent Citations

Research Materials

- NCI CPTC Antibody Characterization Program

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Frankenstein: the real experiments that inspired the fictional science

Professor of History, Aberystwyth University

Disclosure statement

Iwan Morus receives funding from the AHRC as part of the Unsettling Scientific Stories project.

Aberystwyth University provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

On January 17 1803, a young man named George Forster was hanged for murder at Newgate prison in London. After his execution, as often happened, his body was carried ceremoniously across the city to the Royal College of Surgeons, where it would be publicly dissected. What actually happened was rather more shocking than simple dissection though. Forster was going to be electrified.

The experiments were to be carried out by the Italian natural philosopher Giovanni Aldini, the nephew of Luigi Galvani, who discovered “ animal electricity ” in 1780, and for whom the field of galvanism is named. With Forster on the slab before him, Aldini and his assistants started to experiment. The Times newspaper reported:

On the first application of the process to the face, the jaw of the deceased criminal began to quiver, the adjoining muscles were horribly contorted, and one eye was actually opened. In the subsequent part of the process, the right hand was raised and clenched, and the legs and thighs were set in motion.

It looked to some spectators “as if the wretched man was on the eve of being restored to life.”

By the time Aldini was experimenting on Forster the idea that there was some peculiarly intimate relationship between electricity and the processes of life was at least a century old. Isaac Newton speculated along such lines in the early 1700s. In 1730, the English astronomer and dyer Stephen Gray demonstrated the principle of electrical conductivity. Gray suspended an orphan boy on silk cords in mid air , and placed a positively charged tube near the boy’s feet, creating a negative charge in them. Due to his electrical isolation, this created a positive charge in the child’s other extremities, causing a nearby dish of gold leaf to be attracted to his fingers.

In France in 1746 Jean Antoine Nollet entertained the court at Versailles by causing a company of 180 royal guardsmen to jump simultaneously when the charge from a Leyden jar (an electrical storage device) passed through their bodies.

It was to defend his uncle’s theories against the attacks of opponents such as Alessandro Volta that Aldini carried out his experiments on Forster. Volta claimed that “animal” electricity was produced by the contact of metals rather than being a property of living tissue, but there were several other natural philosophers who took up Galvani’s ideas with enthusiasm. Alexander von Humboldt experimented with batteries made entirely from animal tissue. Johannes Ritter even carried out electrical experiments on himself to explore how electricity affected the sensations.

The idea that electricity really was the stuff of life and that it might be used to bring back the dead was certainly a familiar one in the kinds of circles in which the young Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley – the author of Frankenstein – moved. The English poet, and family friend, Samuel Taylor Coleridge was fascinated by the connections between electricity and life. Writing to his friend the chemist Humphry Davy after hearing that he was giving lectures at the Royal Institution in London, he told him how his “motive muscles tingled and contracted at the news, as if you had bared them and were zincifying the life-mocking fibres”. Percy Bysshe Shelley himself – who would become Wollstonecraft’s husband in 1816 – was another enthusiast for galvanic experimentation .

Vital knowledge

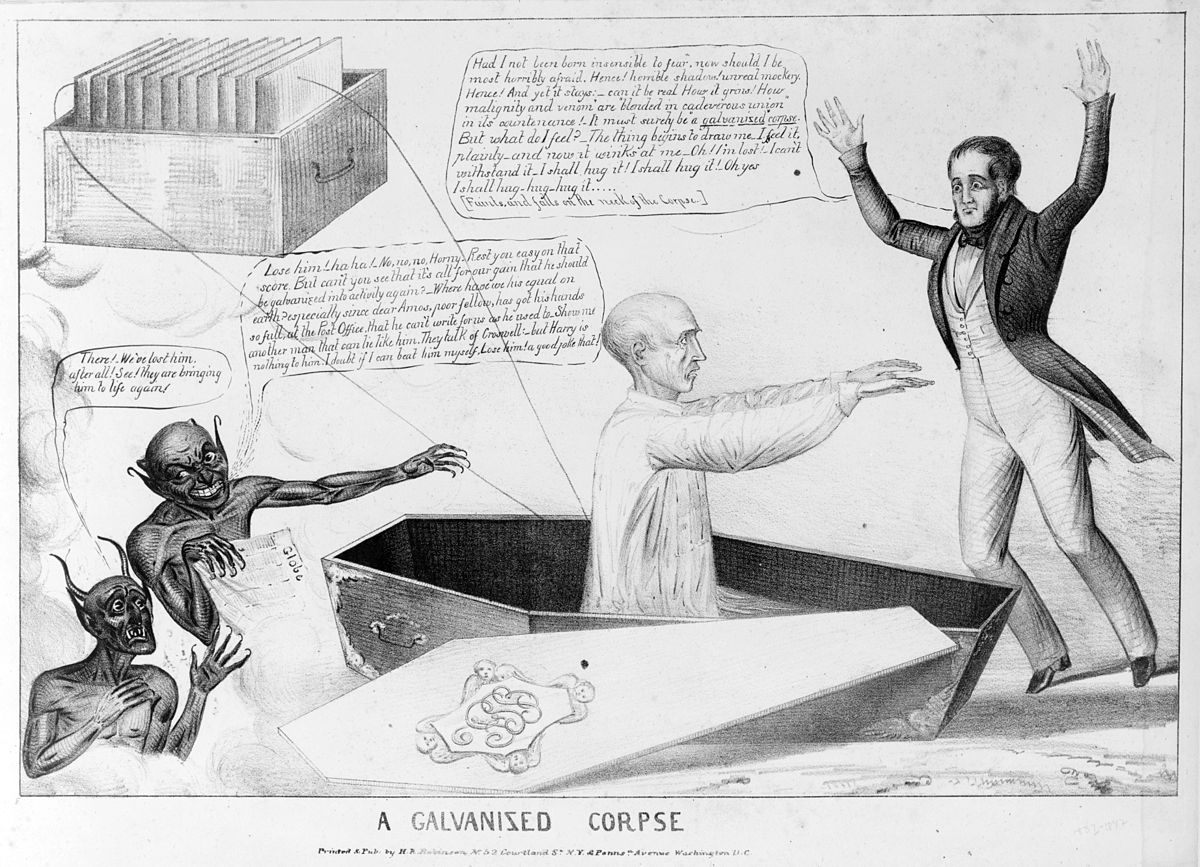

Aldini’s experiments with the dead attracted considerable attention. Some commentators poked fun at the idea that electricity could restore life, laughing at the thought that Aldini could “ make dead people cut droll capers ”. Others took the idea very seriously. Lecturer Charles Wilkinson, who assisted Aldini in his experiments, argued that galvanism was “an energising principle, which forms the line of distinction between matter and spirit, constituting in the great chain of the creation, the intervening link between corporeal substance and the essence of vitality”.

In 1814 the English surgeon John Abernethy made much the same sort of claim in the annual Hunterian lecture at the Royal College of Surgeons. His lecture sparked a violent debate with fellow surgeon William Lawrence. Abernethy claimed that electricity was (or was like) the vital force while Lawrence denied that there was any need to invoke a vital force at all to explain the processes of life. Both Mary and Percy Shelley certainly knew about this debate – Lawrence was their doctor.

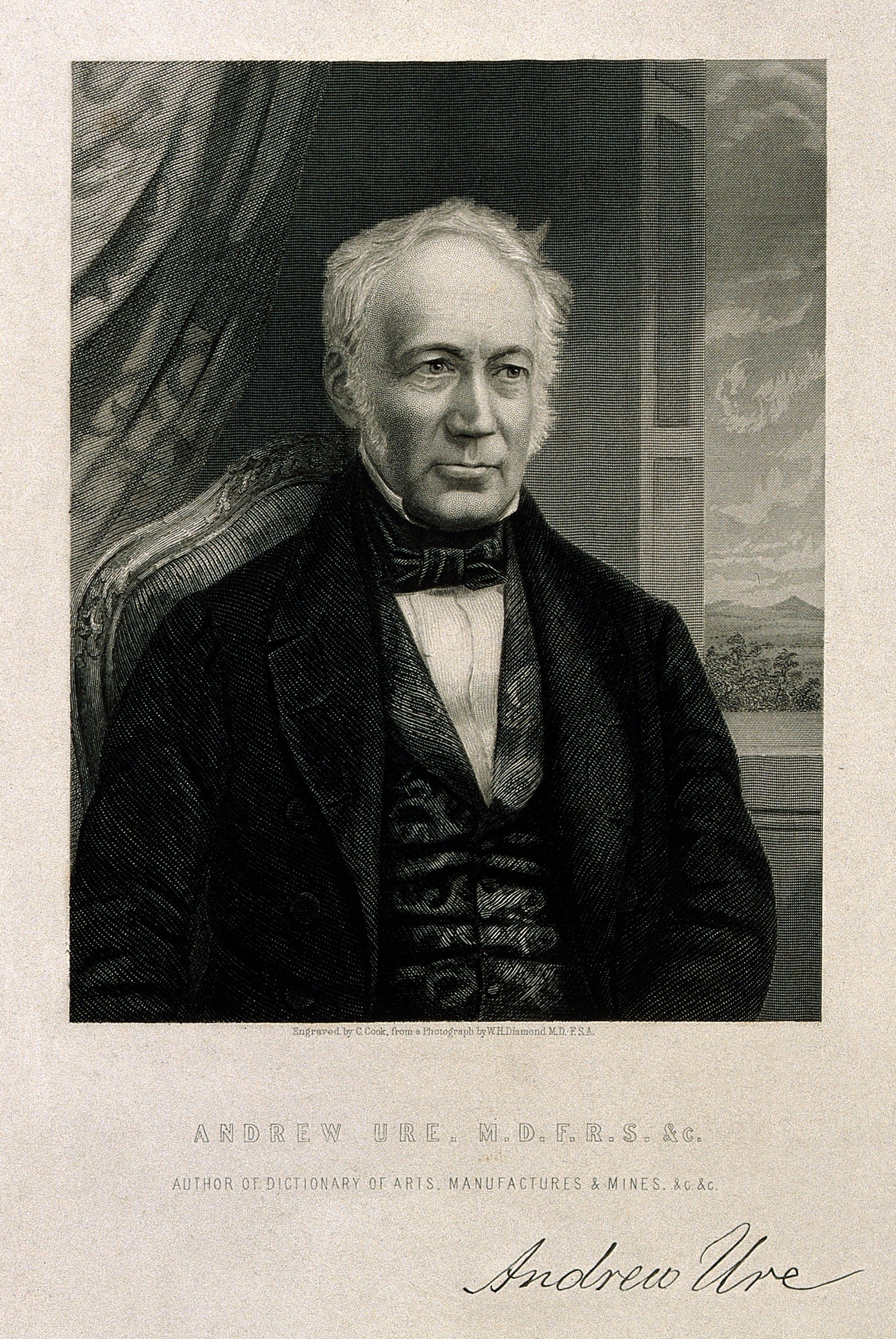

By the time Frankenstein was published in 1818, its readers would have been familiar with the notion that life could be created or restored with electricity. Just a few months after the book appeared, the Scottish chemist Andrew Ure carried out his own electrical experiments on the body of Matthew Clydesdale, who had been executed for murder. When the dead man was electrified , Ure wrote, “every muscle in his countenance was simultaneously thrown into fearful action; rage, horror, despair, anguish, and ghastly smiles, united their hideous expression in the murderer’s face”.

Ure reported that the experiments were so gruesome that “several of the spectators were forced to leave the apartment, and one gentleman fainted”. It is tempting to speculate about the degree to which Ure had Mary Shelley’s recent novel in mind as he carried out his experiments. His own account of them was certainly quite deliberately written to highlight their more lurid elements.

Frankenstein might look like fantasy to modern eyes, but to its author and original readers there was nothing fantastic about it. Just as everyone knows about artificial intelligence now, so Shelley’s readers knew about the possibilities of electrical life. And just as artificial intelligence (AI) invokes a range of responses and arguments now, so did the prospect of electrical life – and Shelley’s novel – then.

The science behind Frankenstein reminds us that current debates have a long history – and that in many ways the terms of our debates now are determined by it. It was during the 19th century that people started thinking about the future as a different country, made out of science and technology. Novels such as Frankenstein, in which authors made their future out of the ingredients of their present, were an important element in that new way of thinking about tomorrow.

Thinking about the science that made Frankenstein seem so real in 1818 might help us consider more carefully the ways we think now about the possibilities – and the dangers – of our present futures.

- Frankenstein

- Mary Shelley

University Relations Manager

2024 Vice-Chancellor's Research Fellowships

Head of Research Computing & Data Solutions

Community member RANZCO Education Committee (Volunteer)

Director of STEM

The Real Electric Frankenstein Experiments of the 1800s

Why scientists during the late 18th and 19th centuries conducted crude experiments with reanimating corpses..

On November 4, 1818, Scottish chemist Andrew Ure stood next to the lifeless corpse of an executed murderer, the man hanging by his neck at the gallows only minutes before. He was performing an anatomical research demonstration for a theater filled with curious students, anatomists, and doctors at the University of Glasgow. But this was no ordinary cadaver dissection. Ure held two metallic rods charged by a 270-plate voltaic battery to various nerves and watched in delight as the body convulsed, writhed, and shuddered in a grotesque dance of death.

“When the one rod was applied to the slight incision in the tip of the forefinger,” Ure later described to the Glasgow Literary Society, “the fist being previously clenched, that finger extended instantly; and from the convulsive agitation of the arm, he seemed to point to the different spectators, some of whom thought he had come to life.”

Ure is one of many scientists during the late 18th and 19th centuries who conducted crude experiments with galvanism—the stimulation of muscles with pulses of electrical current. The bright sparks and loud explosions made for stunning effects that lured in both scientists and artists, with this era of reanimation serving as inspiration for Mary Shelley’s literary masterpiece, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. While most scientists were using galvanism to search for clues about life, Ure wanted to see if it could actually bring someone back from the dead.

“This was a time when people were trying to understand the origin of life, when religion was losing some of its hold,” says Juliet Burba, chief curator of the exhibit “ Mary and Her Monster ” at the Bakken Museum in Minnesota, which will open October 29. “There was a lot of interest in the question: What is the essence that animates life? Could it be electricity?”

In 1780, Italian anatomy professor Luigi Galvani discovered that he could make the muscles of a dead frog twitch and jerk with sparks of electricity. Others quickly began to experiment by applying electricity to other animals that quickly grew morbid. Galvani’s nephew, physicist Giovanni Aldini, obtained the body of an ox, proceeding to cut off the head and use electricity to twist its tongue. He sent such high levels of voltage through the diaphragm of the ox that it resulted in “a very strong action on the rectum, which even produced an expulsion of the feces,” Aldini wrote .

People outside of science were also fascinated by electricity. They would attend shows where bull heads and pigs were electrified, and watch public dissections at research institutions such as the Company of Surgeons in England, which later became the Royal College of Surgeons .

When scientists tired of testing animals, they turned to corpses, particularly corpses of murderers. In 1751, England passed the Murder Act, which allowed the bodies of executed murderers to be used for experimentation. “The reasons the Murder Act came about were twofold: there weren’t enough bodies for anatomists, and it was seen as a further punishment for the murderer,” says Burba. “It was considered additional punishment to have your body dissected.”

Lying on Ure’s table was the muscular, athletic corpse of 35-year-old coal miner, Matthew Clydesdale. On August 1818, Clydesdale drunkenly murdered an 80-year-old miner with a coal pick and was sentenced to be hung at the gallows. His body remained suspended and limp for nearly an hour, while a thief who had been executed next to Clydesdale at the same time convulsed violently for several moments after death. The blood was drained from the body for half an hour before the experiments began.

Andrew Ure, who had little to no known experience with electricity, was a mere assistant to James Jeffray, an anatomy professor at the University of Glasgow. He had studied medicine at Glasgow University and served briefly as an army surgeon, but was otherwise known for teaching chemistry. “Not much is known about Ure, but he was sort of a minor figure in the history of science,” says Alex Boese, author of Elephants on Acid: And Other Bizarre Experiments . One of Ure’s main accomplishments was this single bizarre galvanic experiment, he says.

Others, such as Aldini, conducted similar experiments, but scholars write that Ure was convinced that electricity could restore life back into the dead. “While Aldini contented himself with the role of spasmodic puppeteer, Ure’s ambitions were well nigh Frankesteinian,” wrote Ulf Houe in Studies in Romanticism .

Ure charged the battery with dilute nitric and sulphuric acids five minutes before the police delivered the body to the University of Glasgow’s anatomical theater. Incisions were made at the neck, hip, and heels, exposing different nerves that were jolted with the metallic rods. When Ure sent charges through Clydesdale’s diaphragm and saw his chest heave and fall, he wrote that “the success of it was truly wonderful.”

Ure’s descriptions of the experiment are vivid. He poetically noted how the convulsive movements resembled “a violent shuddering from cold” and how the fingers “moved nimbly, like those of a violin performer.” Other passages, like this one about stimulating muscles in Clydesdale’s forehead and brow, are more macabre:

“Every muscle in his countenance was simultaneously thrown into fearful action; rage, horror, despair, anguish, and ghastly smiles, united their hideous expression in the murderer’s face, surpassing far the wildest representations of a Fuseli or a Kean,” wrote Ure, comparing the result to the visage of tragic actor, Edmund Kean, and the fantastical works of romantic painter Henry Fuseli. He continued: “At this period several of the spectators were forced to leave the apartment from terror or sickness, and one gentleman fainted.”

The whole experiment lasted about an hour. “Both Jeffray and Ure were quite deliberately intent on the restoration of life,” wrote F.L.M. Pattinson in the Scottish Medical Journal . But the reasons for the lack of success were thought to have little to do with the method: Ure concluded that if death was not caused by bodily injury there was a probability that life could have been restored. But, if the experiment succeeded it wouldn’t have been celebrated since he would be reviving a murderer, he wrote.

Mary Shelley was aware of the types of scientific experiments researchers were toying with at the time. “Science was something that the public paid attention to,” says Burba. “There was a lot of crossover, so there were poets who knew a lot about science and scientists who wrote poetry.”

Two years before Ure conducted the experiment, Mary Shelley came up with the story of Frankenstein , and published the novel in 1818, the same year as Ure’s experiment. By sheer coincidence, Victor Frankenstein also brought the monster to life “on a dreary night of November.” However, unlike Ure, the scene of the creature’s resurrection is brief and vague, with no mention of the word “electricity.” Shelley wrote that Frankenstein “collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet.”

Some historians have hypothesized that Shelley was inspired by other medical procedures being studied at the time, including blood transfusion and organ transplants. It isn’t until later in her introduction of the 1831 edition of the book that Shelley mentions galvanism: “Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated; galvanism had given token of such things: perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth.”

It’s unclear whether Frankenstein further encouraged Ure or others to dapple in galvanic experimentation, or if Shelley was particularly struck by any one experiment . Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and these galvanic experiments happened in tandem, Burba explains, pointing out that the language in the novel reflects that of scientists of that era. “Both of these things were happening within a cultural milieu where there was great interest in electricity as well as the effects of electricity on bodies—whether electricity might be the ‘spark of being’ that animates life.”

No actual scientific knowledge or data came from Ure’s experiment, yet he still enthusiastically lectured about his experience. He wrote up the results in a pamphlet, which was seen as “publicity of the crudest kind,” W.V. Farrar wrote in Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. “This rather ‘Gothick’ experiment, reported in such appropriate literary style, no doubt made Ure’s name better known.”

These animated and horrifying displays eventually went out of style as sectors of the public began to view them as evil and “ satanic in nature .” Electricity’s first rudimentary experiments on the body did make way for resuscitation technologies such as defibrillation, but the focus is now on saving lives, not reanimating a long-dead corpse.

“Traditionally, we overlook horrors in the name of science,” says Boese. “We have codes of what’s acceptable behavior in normal everyday life, but people put on a lab coat and there are totally different codes of conduct that seem to apply. These scientists in the early 18th century were gentleman, upstanding members of society, yet they’re doing these things that seem totally sociopathic and bizarre.”

Some of their experiments on non-human animals have stood the test of time, however. Students in biology classes still conduct Galvani’s famous frog muscle experiment today.

How the Hidden Sounds of Horror Movie Soundtracks Freak You Out

Using an ad blocker?

We depend on ad revenue to craft and curate stories about the world’s hidden wonders. Consider supporting our work by becoming a member for as little as $5 a month.

The Shocking Sex Lives of Electric Eels in Brazil

Podcast: The Theater of Electricity

Can America’s Premier Lightning Lab Revive Its Renegade Spirit?

A New Edition of 'Frankenstein' for Scientists, Mad and Otherwise

Atlas Obscura Tries: Magnet Fishing

A 30-Acre Garden Inspired by the Principles of Modern Physics

The Flesh-Eating Beetles of Chicago's Field Museum

Inside Ohio's Experimental Archaeology Lab

A Visit to Buffalo's Lava Lab

Where Scientists Play With Fire

A Colossal Squid Is Hiding in New Zealand

This Volcano Won't Stop Erupting | Untold Earth

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Pre-Order Atlas Obscura: Wild Life Today!

Add some wonder to your inbox, we'd like you to like us.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Though Aldini considered his experiment a failure, as Foster had ultimately failed to return to life, the doctors who had witnessed it considered it a miracle. News quickly spread of Aldini’s feat, how he had opened an eye, and maybe even breathed.

His scientific work was chiefly concerned with galvanism, anatomy and its medical applications, with the construction and illumination of lighthouses, and with experiments for preserving human life and material objects from destruction by fire.

Giovanni Aldini: This Real-Life Dr. Frankenstein Electrified the Dead. The idea that electricity could be used to jumpstart life doesn't just come from fiction. Like Dr. Frankenstein, Aldini's grisly experiments sought to prove that it's possible to revive the dead. By Sara Novak. Oct 20, 2022 7:00 AMOct 29, 2022 10:26 AM.

Aldini used Volta's bimetallic pile to apply electric current to dismembered bodies of animals and humans; these spectacular galvanic reanimation experiments made a strong and enduring impression on his contemporaries.

The experiments were to be carried out by the Italian natural philosopher Giovanni Aldini, the nephew of Luigi Galvani, who discovered “ animal electricity ” in 1780, and for whom the field...

Galvani’s nephew, physicist Giovanni Aldini, obtained the body of an ox, proceeding to cut off the head and use electricity to twist its tongue.

Two hundred years ago, Giovanni Aldini published a highly influential book that reported experiments in which the principles of Luigi Galvani (animal electricity) and Alessandro Volta (bimetallic electricity) were used together for the first time.

A look at Giovanni Aldini’s experiments with galvanic fluid. Everyone has heard of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley: the chilling tale of Victor Frankenstein’s creation of an eight-foot tall humanoid in an ambiguous but nevertheless unconventional scientific experiment.

ABSTRACT : T wo hundred years ago, Giovanni Aldini published a highly influential book that reported experiments in which the principles of Luigi Galvani (animal electricity) and Alessandro Volta (bimetallic electricity) were used together for the first time.

Two hundred years ago, Giovanni Aldini published a highly influential book that reported experiments in which the principles of Luigi Galvani (animal electricity) and Alessandro Volta (bimetallic...