Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Media Bias — Media Bias In News Report

Media Bias in News Report

- Categories: Media Bias

About this sample

Words: 667 |

Published: Mar 19, 2024

Words: 667 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, origins of media bias, manifestations of media bias, implications of media bias, addressing media bias.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 507 words

1 pages / 496 words

4 pages / 1882 words

2 pages / 1084 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Media Bias

In today's digital age, the media plays a significant role in shaping public opinion and influencing societal narratives. However, the phenomenon of media bias has increasingly come under scrutiny, with accusations of liberal [...]

Dolliver, M. Kenney J. Reid L, & Prohaska A, (2018). Examining the Relationship Between Media Consumption, Fear of Crime, and Support for Controversial Criminal Justice Policies Using a Nationally Representative Sample. Journal [...]

The United States has the most developed, thriving and advanced mass media in the world. Throughout the year, we learned about the different amendments in our Constitution. And as we all know, it is the most important document [...]

Although media freedom is regarded as the foundation of modern democracy, it is shown that media control is crucial to the autocratic system for the significant social influence of propaganda and regime support. China, as the [...]

Professional journalists are authoritative sources the public upholds to receive current and accurate information about a variety of topics. Unfortunately, that is not the case for some publications. “Faking It Sex Lies and [...]

Are friendships with real meaning needed? Should social media be distracting me from doing my homework? Do I really need to interact with my family all the time? These are all questions no one would choose to ask. Social media [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Elizabeth Morrissette, Grace McKeon, Alison Louie, Amy Luther, and Alexis Fagen

Media bias could be defined as the unjust favoritism and reporting of a certain ideas or standpoint. In the news, social media, and entertainment, such as movies or television, we see media bias through the information these forms of media choose to pay attention to or report (“How to Detect Bias in News Media”, 2012). We could use the example of the difference between FOX news and CNN because these two news broadcasters have very different audiences, they tend to be biased to what the report and how they report it due to democratic or republican viewpoints.

Bias, in general, is the prejudice or preconceived notion against a person, group or thing. Bias leads to stereotyping which we can see on the way certain things are reported in the news. As an example, during Hurricane Katrina, there were two sets of photos taken of two people wading through water with bags of food. The people, one white and one black, were reported about but the way they were reported about was different. For the black man, he was reported “looting” a grocery store, while the white person was reported “finding food for survival”. The report showed media bias because they made the black man seem like he was doing something wrong, while the white person was just “finding things in order to survive” (Guarino, 2015).

Commercial media is affected by bias because a corporation can influence what kind of entertainment is being produced. When there is an investment involved or money at stake, companies tend to want to protect their investment by not touching on topics that could start a controversy (Pavlik, 2018). In order to be able to understand what biased news is, we must be media literate. To be media literate, we need to adopt the idea that news isn’t completely transparent in the stories they choose to report. Having the knowledge that we can’t believe everything we read or see on the news will allow us as a society to become a more educated audience (Campbell, 2005).

Bias in the News

The news, whether we like it or not, is bias. Some news is bias towards Republicans while other news outlets are biased towards Democrats. It’s important to understand this when watching or reading the news to be media literate. This can be tricky because journalists may believe that their reporting is written with “fairness and balance” but most times there is an underlying bias based around what news provider the story is being written for (Pavlik and McIntosh, 61). With events happening so rapidly, journalist write quickly and sometimes point fingers without trying to. This is called Agenda-Setting which is defined by Shirley Biagi as, how reporters neglect to tell people what to think, but do tell them what and who to talk about (Biagi, 268).

The pressure to put out articles quickly, often times, can affect the story as well. How an event is portrayed, without all the facts and viewpoints, can allow the scene to be laid out in a way that frames it differently than it may have happened (Biagi, 269). However, by simply watching or reading only one portrayal of an event people will often blindly believe it is true, without see or reading other stories that may shine a different light on the subject (Vivian, 4). Media Impact defines this as Magic Bullet Theory or the assertion that media messages directly and measurably affect people’s behavior (Biagi, 269). The stress of tight time deadlines also affects the number of variations of a story. Journalist push to get stories out creates a lack of deeper consideration to news stories. This is called Consensus Journalism or the tendency among journalists covering the same topic to report similar articles instead of differing interpretations of the event (Biagi, 268).

To see past media bias in the news it’s important to be media literate. Looking past any possible framing, or bias viewpoints and getting all the facts to create your own interpretation of a news story. It doesn’t hurt to read both sides of the story before blindly following what someone is saying, taking into consideration who they might be biased towards.

Stereotypes in the Media

Bias is not only in the news, but other entertainment media outlets such as TV and movies. Beginning during childhood, our perception of the world starts to form. Our own opinions and views are created as we learn to think for ourselves. The process of this “thinking for ourselves” is called socialization. One key agent of socialization is the mass media. Mass media portrays ideas and images that at such a young age, are very influential. However, the influence that the media has on us is not always positive. Specifically, the entertainment media, plays a big role in spreading stereotypes so much that they become normal to us (Pavlik and McIntosh, 55).

The stereotypes in entertainment media may be either gender stereotypes or cultural stereotypes. Gender stereotypes reinforce the way people see each gender supposed to be like. For example, a female stereotype could be a teenage girl who likes to go shopping, or a stay at home mom who cleans the house and goes grocery shopping. Men and women are shown in different ways in commercials, TV and movies. Women are shown as domestic housewives, and men are shown as having high status jobs, and participating in more outdoor activities (Davis, 411). A very common gender stereotype for women is that they like to shop, and are not smart enough to have a high-status profession such as a lawyer or doctor. An example of this stereotype can be shown in the musical/movie, Legally Blonde. The main character is woman who is doubted by her male counterparts. She must prove herself to be intelligent enough to become a lawyer. Another example of a gender stereotype is that men like to use tools and drive cars. For example, in most tool and car commercials /advertisements, a man is shown using the product. On the other hand, women are most always seen in commercials for cleaning supplies or products like soaps. This stems the common stereotype that women are stay at home moms and take on duties such as cleaning the house, doing the dishes, doing the laundry, etc.

Racial stereotyping is also quite common in the entertainment media. The mass media helps to reproduce racial stereotypes, and spread those ideologies (Abraham, 184). For example, in movies and TV, the minority characters are shown as their respective stereotypes. In one specific example, the media “manifests bias and prejudice in representations of African Americans” (Abraham, 184). African Americans in the media are portrayed in negative ways. In the news, African Americans are often portrayed to be linked to negative issues such as crime, drug use, and poverty (Abraham 184). Another example of racial stereotyping is Kevin Gnapoor in the popular movie, Mean Girls . His character is Indian, and happens to be a math enthusiast and member of the Mathletes. This example strongly proves how entertainment media uses stereotypes.

Types of Media Bias

Throughout media, we see many different types of bias being used. These is bias by omission, bias by selection of source, bias by story selection, bias by placement, and bias by labeling. All of these different types are used in different ways to prevent the consumer from getting all of the information.

- Bias by omission: Bias by omission is when the reporter leaves out one side of the argument, restricting the information that the consumer receives. This is most prevalent when dealing with political stories (Dugger) and happens by either leaving out claims from either the liberal or conservative sides. This can be seen in either one story or a continuation of stories over time (Media Bias). There are ways to avoid this type of bias, these would include reading or viewing different sources to ensure that you are getting all of the information.

- Bias by selection of sources: Bias by selection of sources occurs when the author includes multiple sources that only have to do with one side (Baker). Also, this can occur when the author intentionally leaves out sources that are pertinent to the other side of the story (Dugger). This type of bias also utilizes language such as “experts believe” and “observers say” to make people believe that what they are reading is credible. Also, the use of expert opinions is seen but only from one side, creating a barrier between one side of the story and the consumers (Baker).

- Bias by story selection: The second type of bias by selection is bias by story selection. This is seen more throughout an entire corporation, rather than through few stories. This occurs when news broadcasters only choose to include stories that support the overall belief of the corporation in their broadcasts. This means ignoring all stories that would sway people to the other side (Baker). Normally the stories that are selected will fully support either the left-wing or right-wing way of thinking.

- Bias by placement: Bias by placement is a big problem in today’s society. We are seeing this type of bias more and more because it is easy with all of the different ways media is presented now, either through social media or just online. This type of bias shows how important a particular story is to the reporter. Editors will choose to poorly place stories that they don’t think are as important, or that they don’t want to be as easily accessible. This placement is used to downplay their importance and make consumers think they aren’t as important (Baker).

- Bias by labeling: Bias by labeling is a more complicated type of bias mostly used to falsely describe politicians. Many reporters will tag politicians with extreme labels on one side of an argument while saying nothing about the other side (Media Bias). These labels that are given can either be a good thing or a bad thing, depending on the side they are biased towards. Some reporters will falsely label people as “experts”, giving them authority that they have not earned and in turn do not deserve (Media Bias). This type of bias can also come when a reporter fails to properly label a politician, such as not labeling a conservative as a conservative (Dugger). This can be difficult to pick out because not all labeling is biased, but when stronger labels are used it is important to check different sources to see if the information is correct.

Bias in Entertainment

Bias is an opinion in favor or against a person, group, and or thing compared to another, and are presented, in such ways to favor false results that are in line with their prejudgments and political or practical commitments (Hammersley & Gomm, 1). Media bias in the entertainment is the bias from journalists and the news within the mass media about stories and events reported and the coverage of them.

There are biases in most entertainment today, such as, the news, movies, and television. The three most common biases formed in entertainment are political, racial, and gender biases. Political bias is when part of the entertainment throws in a political comment into a movie or TV show in hopes to change or detriment the viewers political views (Murillo, 462). Racial bias is, for example, is when African Americans are portrayed in a negative way and are shown in situations that have to do with things such as crime, drug use, and poverty (Mitchell, 621). Gender biases typically have to do with females. Gender biases have to do with roles that some people play and how others view them (Martin, 665). For example, young girls are supposed to be into the color pink and like princess and dolls. Women are usually the ones seen on cleaning commercials. Women are seen as “dainty” and “fragile.” And for men, they are usually seen on the more “masculine types of media, such as things that have to do with cars, and tools.

Bias is always present, and it can be found in all outlets of media. There are so many different types of bias that are present, whether it is found in is found in the news, entertainment industry, or in the portrayal of stereotypes bias, is all around us. To be media literate it’s important to always be aware of this, and to read more than one article, allowing yourself to come up with conclusion; thinking for yourself.

Works Cited

Abraham, Linus, and Osei Appiah. “Framing News Stories: The Role of Visual Imagery in Priming Racial Stereotypes.” Howard Journal of Communications , vol. 17, no. 3, 2006, pp. 183–203.

Baker, Brent H. “Media Bias.” Student News Daily , 2017.

Biagi, Shirley. “Changing Messages.” Media/Impact; An Introduction to Mass Media , 10th ed., Cengage Learning, 2013, pp. 268-270.

Campbell, Richard, et al. Media & Culture: an Introduction to Mass Communication . Bedford/St Martins, 2005.

Davis, Shannon N. “Sex Stereotypes In Commercials Targeted Toward Children: A Content Analysis.” Sociological Spectrum , vol. 23, no. 4, 2003, pp. 407–424.

Dugger, Ashley. “Media Bias and Criticism .” http://study.com/academy/lesson/media-bias-criticism-definition-types-examples.html .

Guarino, Mark. “Misleading reports of lawlessness after Katrina worsened crisis, officials say.” The Guardian , 16 Aug. 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/aug/16/hurricane-katrina-new-orleans-looting-violence-misleading-reports .

Hammersley, Martyn, and Roger Gomm. Bias in Social Research . Vol. 2, ser. 1, Sociological Research Online, 1997.

“How to Detect Bias in News Media.” FAIR , 19 Nov. 2012, http://fair.org/take-action-now/media-activism-kit/how-to-detect-bias-in-news-media/ .

Levasseur, David G. “Media Bias.” Encyclopedia of Political Communication , Lynda Lee Kaid, editor, Sage Publications, 1st edition, 2008. Credo Reference, https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/sagepolcom/media_bias/0 .

Martin, Patricia Yancey, John R. Reynolds, and Shelley Keith, “Gender Bias and Feminist Consciousness among Judges and Attorneys: A Standpoint Theory Analysis,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 27, no. 3 (Spring 2002): 665-701,

Mitchell, T. L., Haw, R. M., Pfeifer, J. E., & Meissner, C. A. (2005). “Racial Bias in Mock Juror Decision-Making: A Meta-Analytic Review of Defendant Treatment.” Law and Human Behavior , 29(6), 621-637.

Murillo, M. (2002). “Political Bias in Policy Convergence: Privatization Choices in Latin America.” World Politics , 54(4), 462-493.

Pavlik, John V., and Shawn McIntosh. “Media Literacy in the Digital Age .” Converging Media: a New Introduction to Mass Communication , Oxford University Press, 2017.

Vivian, John. “Media Literacy .” The Media of Mass Communication , 8th ed., Pearson, 2017, pp. 4–5.

Introduction to Media Studies Copyright © by Elizabeth Morrissette, Grace McKeon, Alison Louie, Amy Luther, and Alexis Fagen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Ethics & Leadership

- Fact-Checking

- Media Literacy

- The Craig Newmark Center

- Reporting & Editing

- Ethics & Trust

- Tech & Tools

- Business & Work

- Educators & Students

- Training Catalog

- Custom Teaching

- For ACES Members

- All Categories

- Broadcast & Visual Journalism

- Fact-Checking & Media Literacy

- In-newsroom

- Memphis, Tenn.

- Minneapolis, Minn.

- St. Petersburg, Fla.

- Washington, D.C.

- Poynter ACES Introductory Certificate in Editing

- Poynter ACES Intermediate Certificate in Editing

- Ethics & Trust Articles

- Get Ethics Advice

- Fact-Checking Articles

- IFCN Grants

- International Fact-Checking Day

- Teen Fact-Checking Network

- International

- Media Literacy Training

- MediaWise Resources

- Ambassadors

- MediaWise in the News

Support responsible news and fact-based information today!

Should you trust media bias charts?

These controversial charts claim to show the political lean and credibility of news organizations. here’s what you need to know about them..

Impartial journalism is an impossible ideal. That is, at least, according to Julie Mastrine.

“Unbiased news doesn’t exist. Everyone has a bias: everyday people and journalists. And that’s OK,” Mastrine said. But it’s not OK for news organizations to hide those biases, she said.

“We can be manipulated into (a biased outlet’s) point of view and not able to evaluate it critically and objectively and understand where it’s coming from,” said Mastrine, marketing director for AllSides , a media literacy company focused on “freeing people from filter bubbles.”

That’s why she created a media bias chart.

As readers hurl claims of hidden bias towards outlets on all parts of the political spectrum, bias charts have emerged as a tool to reveal pernicious partiality.

Charts that use transparent methodologies to score political bias — particularly the AllSides chart and another from news literacy company Ad Fontes Media — are increasing in popularity and spreading across the internet. According to CrowdTangle, a social media monitoring platform, the homepages for these two sites and the pages for their charts have been shared tens of thousands of times.

But just because something is widely shared doesn’t mean it’s accurate. Are media bias charts reliable?

Why do media bias charts exist?

Traditional journalism values a focus on news reporting that is fair and impartial, guided by principles like truth, verification and accuracy. But those standards are not observed across the board in the “news” content that people consume.

Tim Groeling, a communications professor at the University of California Los Angeles, said some consumers take too much of the “news” they encounter as impartial.

When people are influenced by undisclosed political bias in the news they consume, “that’s pretty bad for democratic politics, pretty bad for our country to have people be consistently misinformed and think they’re informed,” Groeling said.

If undisclosed bias threatens to mislead some news consumers, it also pushes others away, he said.

“When you have bias that’s not acknowledged, but is present, that’s really damaging to trust,” he said.

Kelly McBride, an expert on journalism ethics and standards, NPR’s public editor and the chair of the Craig Newmark Center for Ethics and Leadership at Poynter, agrees.

“If a news consumer doesn’t see their particular bias in a story accounted for — not necessarily validated, but at least accounted for in a story — they are going to assume that the reporter or the publication is biased,” McBride said.

The growing public confusion about whether or not news outlets harbor a political bias, disclosed or not, is fueling demand for resources to sort fact from otherwise — resources like these media bias charts.

Bias and social media

Mastrine said the threat of undisclosed biases grows as social media algorithms create filter bubbles to feed users ideologically consistent content.

Could rating bias help? Mastrine and Vanessa Otero, founder of the Ad Fontes media bias chart, think so.

“It’ll actually make it easier for people to identify different perspectives and make sure they’re reading across the spectrum so that they get a balanced understanding of current events,” Mastrine said.

Otero said bias ratings could also be helpful to advertisers.

“There’s this whole ecosystem of online junk news, of polarizing misinformation, these clickbaity sites that are sucking up a lot of ad revenue. And that’s not to the benefit of anybody,” Otero said. “It’s not to the benefit of the advertisers. It’s not to the benefit of society. It’s just to the benefit of some folks who want to take advantage of people’s worst inclinations online.”

Reliable media bias ratings could allow advertisers to disinvest in fringe sites.

Groeling, the UCLA professor, said he could see major social media and search platforms using bias ratings to alter the algorithms that determine what content users see. Changes could elevate neutral content or foster broader news consumption.

But he fears the platforms’ sweeping power, especially after Facebook and Twitter censored a New York Post article purporting to show data from a laptop belonging to Hunter Biden, the son of President-elect Joe Biden. Groeling said social media platforms failed to clearly communicate how and why they stopped and slowed the spread of the article.

“(Social media platforms are) searching for some sort of arbiter of truth and news … but it’s actually really difficult to do that and not be a frightening totalitarian,” he said.

Is less more?

The Ad Fontes chart and the AllSides chart are each easy to understand: progressive publishers on one side, conservative ones on the other.

“It’s just more visible, more shareable. We think more people can see the ratings this way and kind of begin to understand them and really start to think, ‘Oh, you know, journalism is supposed to be objective and balanced,’” Mastrine said. AllSides has rated media bias since 2012. Mastrine first put them into chart form in early 2019.

Otero recognizes that accessibility comes at a price.

“Some nuance has to go away when it’s a graphic,” she said. “If you always keep it to, ‘people can only understand if they have a very deep conversation,’ then some people are just never going to get there. So it is a tool to help people have a shortcut.”

But perceiving the chart as distilled truth could give consumers an undue trust in outlets, McBride said.

“Overreliance on a chart like this is going to probably give some consumers a false level of faith,” she said. “I can think of a massive journalistic failure for just about every organization on this chart. And they didn’t all come clean about it.”

The necessity of getting people to look at the chart poses another challenge. Groeling thinks disinterest among consumers could hurt the charts’ usefulness.

“Asking people to go to this chart, asking them to take effort to understand and do that comparison, I worry would not actually be something people would do. Because most people don’t care enough about news,” he said. He would rather see a plugin that detects bias in users’ overall news consumption and offers them differing viewpoints.

McBride questioned whether bias should be the focus of the charts at all. Other factors — accountability, reliability and resources — would offer better insight into what sources of news are best, she said.

“Bias is only one thing that you need to pay attention to when you consume news. What you also want to pay attention to is the quality of the actual reporting and writing and the editing,” she said. It wouldn’t make sense to rate local news sources for bias, she added, because they are responsive to individual communities with different political ideologies.

The charts are only as good as their methodologies. Both McBride and Groeling shared praise for the stated methods for rating bias of AllSides and Ad Fontes , which can be found on their websites. Neither Ad Fontes nor AllSides explicitly rates editorial standards.

The AllSides Chart

(Courtesy: AllSides)

The AllSides chart focuses solely on political bias. It places sources in one of five boxes — “Left,” “Lean Left,” “Center,” “Lean Right” and “Right.” Mastrine said that while the boxes allow the chart to be easily understood, they also don’t allow sources to be rated on a gradient.

“Our five-point scale is inherently limited in the sense that we have to put somebody in a category when, in reality, it’s kind of a spectrum. They might fall in between two of the ratings,” Mastrine said.

That also makes the chart particularly easy to understand, she said.

AllSides has rated more than 800 sources in eight years, focusing on online content only. Ratings are derived from a mix of review methods.

In the blind bias survey, which Mastrine called “one of (AllSides’) most robust bias rating methodologies,” readers from the public rate articles for political bias. Two AllSides staffers with different political biases pull articles from the news sites that are being reviewed. AllSides locates these unpaid readers through its newsletter, website, social media account and other marketing tools. The readers, who self-report their political bias after they use a bias rating test provided by the company, only see the article’s text and are not told which outlet published the piece. The data is then normalized to more closely reflect the composure of America across political groupings.

AllSides also uses “editorial reviews,” where staff members look directly at a source to contribute to ratings.

“That allows us to actually look at the homepage with the branding, with the photos and all that and kind of get a feel for what the bias is, taking all that into account,” Mastrine said.

She added that an equal number of staffers who lean left, right and center conduct each review together. The personal biases of AllSides’ staffers appear on their bio pages . Mastrine leans right.

She clarified that among the 20-person staff, many are part time, 14% are people of color, 38% are lean left or left, 29% are center, and 18% are lean right or right. Half of the staffers are male, half are female.

When a news outlet receives a blind bias survey and an editorial review, both are taken into account. Mastrine said the two methods aren’t weighted together “in any mathematical way,” but said they typically hold roughly equal weight. Sometimes, she added, the editorial review carries more weight.

AllSides also uses “independent research,” which Mastrine described as the “lowest level of bias verification.” She said it consists of staffers reviewing and reporting on a source to make a preliminary bias assessment. Sometimes third-party analyses — including academic research and surveys — are incorporated into ratings, too.

AllSides highlights the specific methodologies used to judge each source on its website and states its confidence in the ratings based on the methods used. In a separate white paper , the company details the process used for its August 2020 blind bias survey.

AllSides sometimes gives separate ratings to different sections of the same source. For example, it rates The New York Times’ opinion section “Left” and its news section “Lean Left.” AllSides also incorporates reader feedback into its system. People can mark that they agree or disagree with AllSides’ rating of a source. When a significant number of people disagree, AllSides often revisits a source to vet it once again, Mastrine said.

The AllSides chart generally gets good reviews, she said, and most people mark that they agree with the ratings. Still, she sees one misconception among the people that encounter it: They think center means better. Mastrine disagrees.

“The center outlets might be omitting certain stories that are important to people. They might not even be accurate,” she said. “We tell people to read across the spectrum.”

To make that easier, AllSides offers a curated “ balanced news feed ,” featuring articles from across the political spectrum, on its website.

AllSides makes money through paid memberships, one-time donations, media literacy training and online advertisements. It plans to become a public benefit corporation by the end of the year, she added, meaning it will operate both for profit and for a stated public mission.

The Ad Fontes chart

(Courtesy: Ad Fontes)

The Ad Fontes chart rates both reliability and political bias. It scores news sources — around 270 now, and an expected 300 in December — using bias and reliability as coordinates on its chart.

The outlets appear on a spectrum, with seven markers showing a range from “Most Extreme Left” to “Most Extreme Right” along the bias axis, and eight markers showing a range from “Original Fact Reporting” to “Contains Inaccurate/Fabricated Info” along the reliability axis.

The chart is a departure from its first version, back when founder Vanessa Otero , a patent attorney, said she put together a chart by herself as a hobby after seeing Facebook friends fight over the legitimacy of sources during the 2016 election. Otero said that when she saw how popular her chart was, she decided to make bias ratings her full-time job and founded Ad Fontes — Latin for “to the source” — in 2018.

“There were so many thousands of people reaching out to me on the internet about this,” she said. “Teachers were using it in their classrooms as a tool for teaching media literacy. Publishers wanted to publish it in textbooks.”

About 30 paid analysts rate articles for Ad Fontes. Listed on the company’s website , they represent a range of experience — current and former journalists, educators, librarians and similar professionals. The company recruits analysts through its email list and references and vets them through a traditional application process. Hired analysts are then trained by Otero and other Ad Fontes staff.

To start review sessions, a group of coordinators composed of senior analysts and the company’s nine staffers pulls articles from the sites being reviewed. They look for articles listed as most popular or displayed most prominently.

Part of the Ad Fontes analyst political bias test. The test asks analysts to rank their political bias on 18 different policy issues.

Ad Fontes administers an internal political bias test to analysts, asking them to rank their left-to-right position on about 20 policy positions. That information allows the company to attempt to create ideological balance by including one centrist, one left-leaning and one right-leaning analyst on each review panel. The panels review at least three articles for each source, but they may review as many as 30 for particularly prominent outlets, like The Washington Post, Otero said. More on their methodology, including how they choose which articles to review to create a bias rating, can be found here on the Ad Fontes website.

When they review the articles, the analysts see them as they appear online, “because that’s how people encounter all content. No one encounters content blind,” Otero said. The review process recently changed so that paired analysts discuss their ratings over video chat, where they are pushed to be more specific as they form ratings, Otero said.

Individual scores for an article’s accuracy, the use of fact or opinion, and the appropriateness of its headline and image combine to create a reliability score. The bias score is determined by the article’s degree of advocacy for a left-to-right political position, topic selection and omission, and use of language.

To create an overall bias and reliability score for an outlet, the individual scores for each reviewed article are averaged, with added importance given to more popular articles. That average determines where sources show up on the chart.

Ad Fontes details its ratings process in a white paper from August 2019.

While the company mostly reviews prominent legacy news sources and other popular news sites, Otero hopes to add more podcasts and video content to the chart in coming iterations. The chart already rates video news channel “ The Young Turks ” (which claims to be the most popular online news show with 250 million views per month and 5 million subscribers on YouTube ), and Otero mentioned she next wants to examine videos from Prager University (which claims 4 billion lifetime views for its content, has 2.84 million subscribers on YouTube and 1.4 million followers on Instagram ). Ad Fontes is working with ad agency Oxford Road and dental care company Quip to create ratings for the top 50 news and politics podcasts on Apple Podcasts, Otero said.

“It’s not strictly traditional news sources, because so much of the information that people use to make decisions in their lives is not exactly news,” Otero said.

She was shocked when academic textbook publishers first wanted to use her chart. Now she wants it to become a household tool.

“As we add more news sources on to it, as we add more data, I envision this becoming a standard framework for evaluating news on at least these two dimensions of reliability and bias,” she said.

She sees complaints about it from both ends of the political spectrum as proof that it works.

“A lot of people love it and a lot of people hate it,” Otero said. “A lot of people on the left will call us neoliberal shills, and then a bunch of people that are on the right are like, ‘Oh, you guys are a bunch of leftists yourselves.’”

The project has grown to include tools for teaching media literacy to school kids and an interactive version of the chart that displays each rated article. Otero’s company operates as a public benefit corporation with a stated public benefit mission: “to make news consumers smarter and news media better.” She didn’t want Ad Fontes to rely on donations.

“If we want to grow with a problem, we have to be a sustainable business. Otherwise, we’re just going to make a small difference in a corner of the problem,” she said.

Ad Fontes makes money by responding to specific research requests from advertisers, academics and other parties that want certain outlets to be reviewed. The company also receives non-deductible donations and operates on WeFunder , a grassroots crowdfunding investment site, to bring in investors. So far, Ad Fontes has raised $163,940 with 276 investors through the site.

Should you use the charts?

Media bias charts with transparent, rigorous methodologies can offer insight into sources’ biases. That insight can help you understand what perspectives sources bring as they share the news. That insight also might help you understand what perspectives you might be missing as a news consumer.

But use them with caution. Political bias isn’t the only thing news consumers should look out for. Reliability is critical, too, and the accuracy and editorial standards of organizations play an important role in sharing informative, useful news.

Media bias charts are a media literacy tool. They offer well-researched appraisals on the bias of certain sources. But to best inform yourself, you need a full toolbox. Check out Poynter’s MediaWise project for more media literacy tools.

This article was originally published on Dec. 14, 2020.

More about media bias charts

- A media bias chart update puts The New York Times in a peculiar position

- Letter to the editor: What Poynter’s critique misses about the Media Bias Chart

What I learned from writing a book about mental health for journalists

It publishes at a time when the levels of stress and pressure faced by many of our colleagues need to be taken far more seriously than they have been

Why it’s unlikely that Trump will lose his voting rights if convicted of a felony in New York

Former President Donald Trump is expected to soon face a jury verdict on felony falsifying business record charges

Advice for old(er) journalists

Early-career folks have some thoughts.

The Washington Post lays out an optimistic new strategy after grim financial numbers

The Post lost $77 million over the last year, and had a 50% drop off in audience since 2020. Leaders unveiled plans to solve those issues.

Was the upside down flag at Samuel Alito’s house illegal?

Hanging the flag upside down is technically against US law. But legal experts say Alito likely did not act illegally.

Comments are closed.

We are too obsessed with alleged bias and objectivity, which so often is in the biased eye of the beholder. The main standard of good journalism should be verifiable factual accuracy.

Hoping to see a follow-up article about whether we can trust fact checker report card charts created by collecting a fact checker’s subjective ratings.

As a writer for Wonkette, I won’t claim to be objective, but we do like to point out that our rating at Ad Fontes – both farthest to the left and the least reliable, is absurd. Apparently we can’t be trusted at all because we do satirical commentary instead of straight news.

When we’ve attempted to point out to Ms. Otero that we adhere to high standards when it comes to factuality, but we also make jokes, she has replied that satire is inherently untrustworthy and biased, particularly since we sometimes use dirty words.

That seems to us a remarkably biased definition of bias.

Start your day informed and inspired.

Get the Poynter newsletter that's right for you.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 22 May 2024

Uncovering the essence of diverse media biases from the semantic embedding space

- Hong Huang 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Hua Zhu 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Wenshi Liu 4 , 5 ,

- Hua Gao 5 ,

- Hai Jin 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 &

- Bang Liu 6

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 656 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Cultural and media studies

Media bias widely exists in the articles published by news media, influencing their readers’ perceptions, and bringing prejudice or injustice to society. However, current analysis methods usually rely on human efforts or only focus on a specific type of bias, which cannot capture the varying magnitudes, connections, and dynamics of multiple biases, thus remaining insufficient to provide a deep insight into media bias. Inspired by the Cognitive Miser and Semantic Differential theories in psychology, and leveraging embedding techniques in the field of natural language processing, this study proposes a general media bias analysis framework that can uncover biased information in the semantic embedding space on a large scale and objectively quantify it on diverse topics. More than 8 million event records and 1.2 million news articles are collected to conduct this study. The findings indicate that media bias is highly regional and sensitive to popular events at the time, such as the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Furthermore, the results reveal some notable phenomena of media bias among multiple U.S. news outlets. While they exhibit diverse biases on different topics, some stereotypes are common, such as gender bias. This framework will be instrumental in helping people have a clearer insight into media bias and then fight against it to create a more fair and objective news environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Testing theory of mind in large language models and humans

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Toolbox of individual-level interventions against online misinformation

Introduction.

In the era of information explosion, news media play a crucial role in delivering information to people and shaping their minds. Unfortunately, media bias, also called slanted news coverage, can heavily influence readers’ perceptions of news and result in a skewing of public opinion (Gentzkow et al. 2015 ; Puglisi and Snyder Jr, 2015b ; Sunstein, 2002 ). This influence can potentially lead to severe societal problems. For example, a report from FAIR has shown that Verizon management is more than twice as vocal as worker representatives in news reports about the Verizon workers’ strike in 2016 Footnote 1 , putting workers at a disadvantage in the news and contradicting the principles of fair and objective journalism. Unfortunately, this is just the tip of the media bias iceberg.

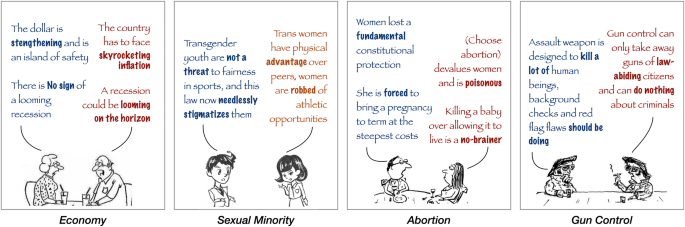

Media bias can be defined as the bias of journalists and news producers within the mass media in selecting and covering numerous events and stories (Gentzkow et al. 2015 ). This bias can manifest in various forms, such as event selection, tone, framing, and word choice (Hamborg et al. 2019 ; Puglisi and Snyder Jr, 2015b ). Given the vast number of events happening in the world at any given moment, even the most powerful media must be selective in what they choose to report instead of covering all available facts in detail (Downs, 1957 ). This selectivity can result in the perception of bias in the news coverage, whether intentional or unintentional. Academics in journalism studies attempt to explain the news selection process by developing taxonomies of news values (Galtung and Ruge, 1965 ; Harcup and O’neill, 2001 , 2017 ), which refer to certain criteria and principles that news editors and journalists consider when selecting, editing, and reporting the news. These values help determine which stories should be considered news and the significance of these stories in news reporting. However, different news organizations and journalists may emphasize different news values based on their specific objectives and audience. Consequently, a media outlet may be very keen on reporting events about specific topics while turning a blind eye to others. For example, news coverage often ignores women-related events and issues with the implicit assumption that they are less critical than men-related contents (Haraldsson and Wängnerud, 2019 ; Lühiste and Banducci, 2016 ; Ross and Carter, 2011 ). Once events are selected, the media must consider how to organize and write their news articles. At that time, the choice of tone, framing, and word is highly subjective and can introduce bias. Specifically, the words used by the authors to refer to different entities may not be neutral but instead imply various associations and value judgments (Puglisi and Snyder Jr, 2015b ). As shown in Fig. 1 , the same topic can be expressed in entirely different ways, depending on a media outlet’s standpoint Footnote 2 . For example, certain “right-wing” media outlets tend to support legal abortion, while some “left-wing” ones oppose it.

The blue and red fonts represent the views of some “left-wing” and “right-wing” media outlets, respectively.

In fact, media bias is influenced by many factors: explicit factors such as geographic location, media position, editorial guideline, topic setting, and so on; obscure factors such as political ideology (Groseclose and Milyo, 2005 ; MacGregor, 1997 ; Merloe, 2015 ), business reason (Groseclose and Milyo, 2005 ; Paul and Elder, 2004 ), and personal career (Baron, 2006 ), etc. Besides, some studies also summarize these factors related to bias as supply-side and demand-side ones (Gentzkow et al. 2015 ; Puglisi and Snyder Jr, 2015b ). The influence of these complex factors makes the emergence of media bias inevitable. However, media bias may hinder readers from forming objective judgments about the real world, lead to skewed public opinion, and even exacerbate social prejudices and unfairness. For example, the New York Times supports Iranian women’s saying no to hijabs in defense of women’s rights Footnote 3 while criticizing the Chinese government’s initiative to encourage Uyghur women to remove hijabs and veils Footnote 4 . Besides, the influence of news coverage on voter behavior is a subject of ongoing debate. While some studies indicate that slanted news coverage can influence voters and election outcomes (Bovet and Makse, 2019 ; DellaVigna and Kaplan, 2008 ; Grossmann and Hopkins, 2016 ), others suggest that this influence is limited in certain circumstances (Stroud, 2010 ). Fortunately, research on media bias has drawn attention from multiple disciplines.

In social science, the study of media bias has a long tradition dating back to the 1950s (White, 1950 ). So far, most of the analyses in social science have been qualitative, aiming to analyze media opinions expressed in the editorial section (e.g., endorsements (Ansolabehere et al. 2006 ), editorials (Ho et al. 2008 ), ballot propositions (Puglisi and Snyder Jr, 2015a )) or find out biased instances in news articles by human annotations (Niven, 2002 ; Papacharissi and de Fatima Oliveira, 2008 ; Vaismoradi et al. 2013 ). Some researchers also conduct quantitative analysis, which primarily involves counting the frequency of specific keywords or articles related to certain issues (D’Alessio and Allen, 2000 ; Harwood and Garry, 2003 ; Larcinese et al. 2011 ). In particular, there are some attempts to estimate media bias using automatic tools (Groseclose and Milyo, 2005 ), and they commonly rely on text similarity and sentiment computation (Gentzkow and Shapiro, 2010 ; Gentzkow et al. 2006 ; Lott Jr and Hassett, 2014 ). In summary, social science research on media bias has yielded extensive and effective methodologies. These methodologies interpret media bias from diverse perspectives, marking significant progress in the realm of media studies. However, these methods usually rely on manual annotation and analysis of the texts, which requires significant manual effort and expertise (Park et al. 2009 ), thus might be inefficient and subjective. For example, in a quantitative analysis, researchers might devise a codebook with detailed definitions and rules for annotating texts, and then ask coders to read and annotate the corresponding texts (Hamborg et al. 2019 ). Developing a codebook demands substantial expertise. Moreover, the standardization process for text annotation is subjective, as different coders may interpret the same text differently, thus leading to varied annotations.

In computer science, research on social media is extensive (Lazaridou et al. 2020 ; Liu et al. 2021b ; Tahmasbi et al. 2021 ), but few methods are specifically designed to study media bias (Hamborg et al. 2019 ). Some techniques that specialize in the study of media bias focus exclusively on one type of bias (Huang et al. 2021 ; Liu et al. 2021b ; Zhang et al. 2017 ), thus not general enough. In natural language processing (NLP), research on the bias of pre-trained models or language models has attracted much attention (Qiang et al. 2023 ), aiming to identify and reduce the potential impact of bias in pre-trained models on downstream tasks (Huang et al. 2020 ; Liu et al. 2021a ; Wang et al. 2020 ). In particular, some studies on pre-trained word embedding models show that they have captured rich human knowledge and biases (Caliskan et al. 2017 ; Grand et al. 2022 ; Zeng et al. 2023 ). However, such works mainly focus on pre-trained models rather than media bias directly, which limits their applicability to media bias analysis.

A major challenge in studying media bias is that the evaluation of media bias is highly subjective because individuals have varying evaluation criteria for bias. Take political bias as an example, a story that one person views as neutral may appear to be left-leaning or right-leaning by someone else. To address this challenge, we develop an objective and comprehensive media bias analysis framework. We study media bias from two distinct but highly relevant perspectives: the macro level and the micro level. From the macro perspective, we focus on the event selection bias of each media, i.e., the types of events each media tends to report on. From the micro perspective, we focus on the bias introduced by media in the choice of words and sentence construction when composing news articles about the selected events.

In news articles, media outlets convey their attitudes towards a subject through the contexts surrounding it. However, the language used by the media to describe and refer to entities may not be purely neutral descriptors but rather imply various associations and value judgments. According to the cognitive miser theory in psychology, the human mind is considered a cognitive miser who tends to think and solve problems in simpler and less effortful ways to avoid cognitive effort (Fiske and Taylor, 1991 ; Stanovich, 2009 ). Therefore, faced with endless news information, ordinary readers will tend to summarize and remember the news content simply, i.e., labeling the things involved in news reports. Frequent association of certain words with a particular entity or subject in news reports can influence a media outlet’s loyal readers to adopt these words as labels for the corresponding item in their cognition due to the cognitive miser effect. Unfortunately, such a cognitive approach is inadequate and susceptible to various biases. For instance, if a media outlet predominantly focuses on male scientists while neglecting their female counterparts, some naive readers may perceive scientists to be mostly male, leading to a recognition bias in their perception of the scientist and even forming stereotypes unconsciously over time. According to the “distributional hypothesis” in modern linguistics (Firth, 1957 ; Harris, 1954 ; Sahlgren, 2008 ), a word’s meaning is characterized by the words occurring in the same context as it. Here, we simplify the complex associations between different words (or entities/subjects) and their respective context words into co-occurrence relationships. An effective technique to capture word semantics based on co-occurrence information is neural network-based word embedding models (Kenton and Toutanova, 2019 ; Le and Mikolov, 2014 ; Mikolov et al. 2013 ).

Word embedding models represent each word in the vocabulary as a vector (i.e., word embedding) within the word embedding space. In this space, words that frequently co-occur in similar contexts are positioned close to each other. For instance, if a media outlet predominantly features male scientists, the word “scientist” and related male-centric terms, such as “man” and “he” will frequently co-occur. Consequently, these words will cluster near the word “scientist” in the embedding space, while female-related words occupy more distant positions. This enables us to evaluate the media outlet’s gender bias concerning the term “scientist” by comparing the embedding distances between “scientist” and words associated with both males and females. This approach aligns closely with the Semantic Differential theory in psychology (Osgood et al. 1957 ), which gauges an individual’s attitudes toward various concepts, objects, and events using bipolar scales constructed from adjectives with opposing semantics. In this study, to identify media bias from news articles, we first define two sets of words with opposite semantics for each topic to develop media bias evaluation scales. Then, we quantify media bias on each topic by calculating the embedding distance difference between a target word (e.g., scientist) and these two sets of words (e.g., female-related words and male-related words) in the word embedding space.

Compared with the bias in news articles, event selection bias is more obscure, as only events of interest to the media are reported in the final articles, while events deliberately ignored by the media remain invisible to the public. Similar to the co-occurrence relationship between words mentioned earlier, two media outlets that frequently select and report on the same events should exhibit similar biases in event selection, as two words that occur frequently in the same contexts have similar semantics. Therefore, we refer to Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA (Deerwester et al. 1990 )) and generate vector representation (i.e., media embedding) for each media via truncated singular value decomposition (Truncated SVD (Halko et al. 2011 )). Essentially, a media embedding encodes the distribution of the events that a media outlet tends to report on. Therefore, in the media embedding space, media outlets that often select and report on the same events will be close to each other due to similar distributions of the selected events. If a media outlet shows significant differences in such a distribution compared to other media outlets, we can conclude that it is biased in event selection. Inspired by this, we conduct clustering on the media embeddings to study how different media outlets differ in the distribution of selected events, i.e., the so-called event selection bias.

These two methodologies, designed for micro-level and macro-level analysis, share a fundamental similarity: both leverage data-driven embedding models to represent each word or media outlet as a distinctive vector within the embedding space and conduct further analysis based on these vectors. Therefore, in this study, we integrate both methodologies into a unified framework for media bias analysis. We aim to uncover media bias on a large scale and quantify it objectively on diverse topics. Our experiment results show that: (1) Different media outlets have different preferences for various news events, and those from the same country or organization tend to share more similar tastes. Besides, the occurrence of international hot events will lead to the convergence of different media outlets’ event selection. (2) Despite differences in media bias, some stereotypes, such as gender bias, are common among various media outlets. These findings align well with our empirical understanding, thus validating the effectiveness of our proposed framework.

Data and methods

The first dataset is the GDELT Mention Table, a product of the Google Jigsaw-backed GDELT project Footnote 5 . This project aims to monitor news reports from all over the world, including print, broadcast, and online sources, in over 100 languages. Each time an event is mentioned in a news report, a new row is added to the Mention Table (See Supplementary Information Tab. S1 for details). Given that different media outlets may report on the same event at varying times, the same event can appear in multiple rows of the table. While the fields GlobalEventID and EventTimeDate are globally unique attributes for each event, MentionSourceName and MentionTimeDate may differ. Based on the GlobalEventID and MentionSourceName fields in the Mention Table, we can count the number of times each media outlet has reported on each event, ultimately constructing a “media-event” matrix. In this matrix, the element at ( i , j ) denotes the number of times that media outlet j has reported on the event i in past reports.

As a global event database, GDELT collects a vast amount of global events and topics, encompassing news coverage worldwide. However, despite its widespread usage in many studies, there are still some noteworthy issues. Here, we highlight some of the issues to remind readers to use it more cautiously. Above all, while GDELT provides a vast amount of data from various sources, it cannot capture every event accurately. It relies on automated data collection methods, and this could result in certain events being missed. Furthermore, its algorithms for event extraction and categorization cannot always perfectly capture the nuanced context and meaning of each event, which might lead to potential misinterpretations.

The second dataset is built on MediaCloud Footnote 6 , an open-source platform for research on media ecosystems. MediaCloud’s API enables the querying of news article URLs for a given media outlet, which can then be retrieved using a web crawler. In this study, we have collected more than 1.2 million news articles from 12 mainstream US media outlets in 2016-2021 via MediaCloud’s API (See Supplementary Information Tab. S2 for details).

Media bias estimation by media embedding

Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA (Deerwester et al. 1990 )) is a well-established technique for uncovering the topic-based semantic relationships between text documents and words. By performing truncated singular value decomposition (Truncated SVD (Halko et al. 2011 )) on a “document-word” matrix, LSA can effectively capture the topics discussed in a corpus of text documents. This is accomplished by representing documents and words as vectors in a high-dimensional embedding space, where the similarity between vectors reflects the similarity of the topics they represent. In this study, we apply this idea to media bias analysis by likening media and events to documents and words, respectively. By constructing a “media-event” matrix and performing Truncated SVD, we can uncover the underlying topics driving the media coverage of specific events. Our hypothesis posits that media outlets mentioning certain events more frequently are more likely to exhibit a biased focus on the topics related to those events. Therefore, media outlets sharing similar topic tastes during event selection will be close to each other in the embedding space, which provides a good opportunity to shed light on the media’s selection bias.

The generation procedures for media embeddings are shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S1 . First, a “media-event” matrix denoted as A m × n is constructed based on the GDELT Mention Table, where m and n represent the total number of media outlets and events, respectively. Each entry A i , j represents the number of times that media i has reported on event j . Subsequently, Truncated SVD is performed on the matrix A m × n , which results in three matrices: U m × k , Σ k × k and \({V}_{n\times k}^{T}\) . The product of Σ k × k and \({V}_{n\times k}^{T}\) is represented by E k × n . Each column of E k × n corresponds to a k -dimensional vector representation for a specific media outlet, i.e., a media embedding. Specifically, the decomposition of matrix A m × n can be formulated as follows:

Equation( 1 ) defines the complete singular value decomposition of A m × n . Both \({U}_{m\times m}^{0}\) and \({({V}_{n\times n}^{0})}^{T}\) are orthogonal matrices. \({{{\Sigma }}}_{m\times n}^{0}\) is a m × n diagonal matrix whose diagonal elements are non-negative singular values of the matrix A m × n in descending order. Equation( 2 ) defines the truncated singular value decomposition (i.e., Truncated SVD) of A m × n . Based on the result of complete singular value decomposition, the part corresponding to the largest k singular values is equivalent to the result of Truncated SVD. Specifically, U m × k comprises the first k columns of the matrix \({U}_{m\times m}^{0}\) , while \({V}_{n\times k}^{T}\) comprises the first k rows of the matrix \({({V}_{n\times n}^{0})}^{T}\) . Additionally, the diagonal matrix Σ k × k is composed of the first k diagonal elements of \({{{\Sigma }}}_{m\times n}^{0}\) , representing the largest k singular values of A m × n . In particular, the media embedding model is defined as the product of the matrices Σ k × k and \({V}_{n\times k}^{T}\) , which has n k -dimensional media embeddings as follows:

To measure the similarity between two media embedding sets, we refer to Word Mover Distance (WMD (Kusner et al. 2015 )). WMD is designed to measure the dissimilarity between two text documents based on word embedding. Here, we subtract the optimal value of the original WMD objective function from 1 to convert the dissimilarity value into a normalized similarity score that ranges from 0 to 1. Specifically, the similarity between two media embedding sets is formulated as follows:

Let n denote the total number of media outlets, and s be an n -dimensional vector corresponding to the first media embedding set. For each i , the weight of media i in the embedding set is given by \({s}_{i}=\frac{1}{\sum_{k = 1}^{n}{t}_{i}}\) , where t i = 1 if media i is in the embedding set, and t i = 0 otherwise. Similarly, \({s}^{{\prime} }\) is another n -dimensional vector corresponding to the second media embedding set. The distance between media i and j is calculated using c ( i , j ) = ∥ e i − e j ∥ 2 , where e i and e j are the embedding representations of media i and j , respectively. The flow matrix T ∈ R n × n is used to determine how much media i in s travels to media j in \({s}^{{\prime} }\) . Specifically, T i , j ≥ 0 denotes the amount of flow from media i to media j .

Media bias estimation by word embedding

Word embedding models (Kenton and Toutanova, 2019 ; Le and Mikolov, 2014 ; Mikolov et al. 2013 ) are widely used in text-related tasks due to their ability to capture rich semantics of natural language. In this study, we regard media bias in news articles as a special type of semantic and capture it using Word2Vec (Le and Mikolov, 2014 ; Mikolov et al. 2013 ).

Supplementary Information Fig. S2 presents the process of building media corpora and training word embedding models to capture media bias. First, we reorganize the corpus for each media outlet by up-sampling to ensure that each media corpus contains the same number of news articles. The advantage of up-sampling is that it makes full use of the existing media corpus data, as opposed to discarding part of the data like down-sampling does. Second, we superimpose all 12 media corpora to construct a large base corpus and pre-train a Word2Vec model denoted as W b a s e based on it. Third, we fine-tune the same pre-trained model W b a s e using the specific corpus of each media outlet separately and get 12 fine-tuned models denoted as \({W}^{{m}_{i}}\) ( i = 1, 2, . . . 12).

In particular, the main objective of reorganizing the original corpora is to ensure that each corpus equivalently contributes to the pre-training process, in case a large corpus from certain media dominates the pre-trained model. As shown in Supplementary Information Tab. S2 , the largest corpus in 2016-2021 is from USA Today, which contains 295,518 news articles. Therefore, we can reorganize the other 11 media corpora by up-sampling to ensure that each of the 12 corpora has 295,518 articles. For example, as for NPR’s initial corpus, which has 14,654 news articles, we first repeatedly superimpose 295, 518//14, 654 = 20 times to get 293,080 articles and then randomly sample 295, 518%14, 654 = 2, 438 from the initial 14,654 articles as a supplement. Finally, we can get a reorganized NPR corpus with 295,518 articles.

Semantic Differential is a psychological technique proposed by (Osgood et al. 1957 ) to measure people’s psychological attitudes toward a given conceptual object. In the Semantic Differential theory, a given object’s semantic attributes can be evaluated in multiple dimensions. Each dimension consists of two poles corresponding to a pair of adjectives with opposite semantics (i.e., antonym pairs). The position interval between the poles of each dimension is divided into seven equally-sized parts. Then, given the object, respondents are asked to choose one of the seven parts in each dimension. The closer the position is to a pole, the closer the respondent believes the object is semantically related to the corresponding adjective. Supplementary Information Fig. S3 provides an example of Semantic Differential.

Constructing evaluation dimensions using antonym pairs in Semantic Differential is a reliable idea that aligns with how people generally evaluate things. For example, when imagining the gender-related characteristics of an occupation (e.g., nurse), individuals usually weigh between “man” and “woman”, both of which are antonyms regarding gender. Likewise, when it comes to giving an impression of the income level of the Asian race, people tend to weigh between “rich” (high income) and “poor” (low income), which are antonyms related to income. Based on such consistency, we can naturally apply Semantic Differential to measure a media outlet’s attitudes towards different entities and concepts, i.e., media bias.

Specifically, given a media m , a topic T (e.g., gender) and two semantically opposite topic word sets \(P={\{{p}_{i}\}}_{i = 1}^{{K}_{1}}\) and \(\neg P={\{\neg {p}_{i}\}}_{i = 1}^{{K}_{2}}\) about topic T , media m ’s bias towards the target x can be defined as:

Here, K 1 and K 2 denote the number of words in topic word sets P and ¬ P , respectively. W m represents the word embedding model obtained by fine-tuning W b a s e using the specific corpus of media m . \(\overrightarrow{{W}_{x}^{m}}\) is the embedding representation of the word x in W m . S i m is a similarity function used to measure the similarity between two vectors (i.e., word embeddings). In practice, we employ the cosine similarity function, which is commonly used in the field of natural language processing. In particular, equation( 5 ) calculates the difference of average similarities between the target word x and two semantically opposite topic word sets, namely P and ¬ P . Similar to the antonym pairs in Semantic Differential, such two topic word sets are used to construct the evaluation scale of media bias. In practice, to ensure the stability of the results, we have repeated this experiment five times, each time with a different random seed for up-sampling. Therefore, the final results shown in Fig. 4 are the average bias values for each topic.

The idea of recovering media bias by embedding methods

We first analyzed media bias from the aspect of event selection to study which topics a media outlet tends to focus on or ignore. Based on the GDELT database, we constructed a large “media-event" matrix that records the times each media outlet mentioned each event in news reports from February to April 2022. To extract media bias information, we referred to the idea of Latent Semantic Analysis (Deerwester et al. 1990 ) and performed Truncated SVD (Halko et al. 2011 ) on this matrix to generate vector representation (i.e., media embedding) for each media outlet (See Methods for details). Specifically, outlets with similar event selection bias (i.e., outlets that often report on events of similar topics) will have similar media embeddings. Such a bias encoded in the vector representation of each outlet is exactly the first type of media bias we aim to study.

Then, we analyzed media bias in news articles to investigate the value judgments and attitudes conveyed by media through their news articles. We collected more than 1.2 million news articles from 12 mainstream US news outlets, spanning from January 2016 to December 2021, via MediaCloud’s API. To identify media bias from each outlet’s corpus, we performed three sequential steps: (1) Pre-train a Word2Vec word embedding model based on all outlets’ corpora. (2) Fine-tune the pre-trained model by using the specific corpus of each outlet separately and obtain 12 fine-tuned models corresponding to the 12 outlets. (3) Quantify each outlet’s bias based on the corresponding fine-tuned model, combined with the idea of Semantic Differential, i.e., measuring the embedding similarities between the target words and two sets of topic words with opposite semantics (See Methods for details). An example of using Semantic Differential (Osgood et al. 1957 ) to quantify media bias is shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S4 .

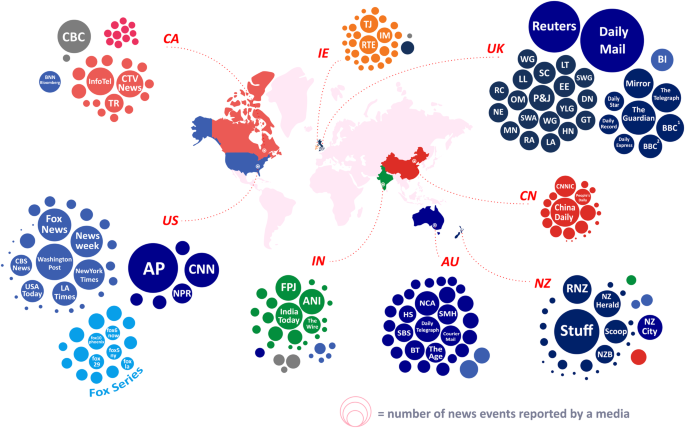

Media show significant clustering due to their regions and organizations

In this experiment, we aimed to capture and analyze the event selection bias of different media outlets based on the proposed media embedding methodology. To achieve a comprehensive analysis, we selected 247 media outlets from 8 countries ( Supplementary Information Tab. S6) , including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Ireland, and New Zealand-six English-speaking nations with India and China, two populous countries. For each country, we chose media outlets that were the most active during February-April 2022, with media activity measured by the quantity of news reports. We then generated embedding representations for each media outlet via Truncated SVD and performed K-means clustering (Lloyd, 1982 ; MacQueen, 1967 ) on the obtained media embedding representations (with K = 10) for further analysis. Details of the experiment are presented in the first section of the supplementary Information. Figure 2 visualizes the clustering results.

There are 247 media outlets from 8 countries: Canada (CA), Ireland (IE), United Kingdom (UK), China (CN), United States (US), India (IN), Australia (AU), and New Zealand (NZ). Each circle in the visualization represents a media outlet, with its color indicating the cluster it belongs to, and its diameter proportional to the number of events reported by the outlet between February and April 2022. The text in each circle represents the name or abbreviation of a media outlet (See Supplementary Information Tab. S6 for details). The results indicate that media outlets from the same country tend to be grouped together in clusters. Moreover, the majority of media outlets in the Fox series form a distinct cluster, indicating a high degree of similarity in their event selection bias.

First, we find that media outlets from different countries tend to form distinct clusters, signifying the regional nature of media bias. Specifically, we can interpret Fig. 2 from two different perspectives, and both come to this conclusion. On the one hand, most media outlets from the same country tend to appear in a limited number of clusters, which suggests that they share similar event selection bias. On the other hand, as we can see, media outlets in the same cluster mostly come from the same country, indicating that media exhibiting similar event selection bias tends to be from the same country. In our view, differences in geographical location lead to diverse initial event information accessibility for media outlets from different regions, thus shaping the content they choose to report.

Besides, we observe an intriguing pattern where the Associated Press (AP) and Reuters, despite their geographical separation, share similar event selection biases as they are clustered together. This abnormal phenomenon could be attributed to their status as international media outlets, which enables them to cover various global events, thus leading to extensive overlapping news coverage. In addition, 16 out of the 21 Fox series media outlets form a distinct cluster on their own, suggesting that a media outlet’s bias is strongly associated with the organization it belongs to. After all, media outlets within the same organization often tend to prioritize or overlook specific events due to shared positions, interests, and other influencing factors.

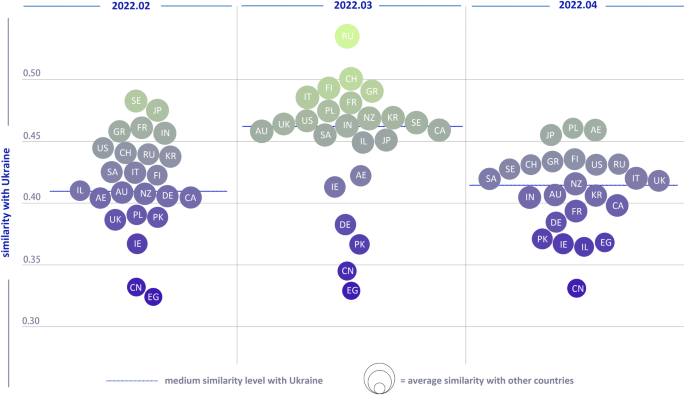

International hot topics drive media bias to converge

Previous results have revealed a significant correlation between media bias and the location of a media outlet. Therefore, we conducted an experiment to further investigate the event selection biases of media outlets from 25 different countries. To achieve this, we gathered GDELT data spanning from February to April 2022 and created three “media-event” matrices on a monthly basis. We then subjected each month’s “media-event” matrix to the same processing steps: (1) generating an embedding representation for each media outlet through matrix decomposition, (2) obtaining the embedding representation of each media outlet that belongs to each country to construct a media embedding set, and (3) calculating the similarity between every two countries (i.e., each two media embedding sets) using Word Mover Distance (WMD (Kusner et al. 2015 )) as the similarity metric (See Methods for details). Figure 3 presents the changes in event selection bias similarity amongst media outlets from different countries between February and April 2022.

The horizontal axis in this figure represents the time axis, measured in months. Meanwhile, the vertical axis indicates the event selection similarity between Ukrainian media and media from other countries. Each circle represents a country, with the font inside it representing the corresponding country’s abbreviation (see details in Supplementary Information Tab. S3) . The size of a circle corresponds to the average event selection similarity between the media of a specific country and the media of all other countries. The color of the circle corresponds to the vertical axis scale. The blue dotted line’s ordinate represents the median similarity to Ukrainian media.

We find that the similarities between Ukraine and other countries peaked significantly in March 2022. This result aligns with the timeline of the Russia-Ukraine conflict: the conflict broke out around February 22, attracting media attention worldwide. In March, the conflict escalated, and the regional situation became increasingly tense, leading to even more media coverage worldwide. By April, the prolonged conflict had made the international media accustomed to it, resulting in a decline in media interest. Furthermore, we observed that the event selection biases of media outlets in both EG (Egypt) and CN (China) differed significantly from those of other countries. Given that both countries are not predominantly English-speaking, their English-language media outlets may have specific objectives such as promoting their national image and culture, which could influence and constrain the topics that a media outlet tends to cover.

Additionally, we observe that in March 2022, the country with the highest similarity to Ukraine was Russia, and in April, it was Poland. This change can be attributed to the evolving regional situation. In March, when the conflict broke out, media reports primarily focused on the warring parties, namely Russia and Ukraine. As the war continued, the impact of the war on Ukraine gradually became the focus of media coverage. For instance, the war led to the migration of a large number of Ukrainian citizens to nearby countries, among which Poland received the most citizens of Ukraine at that time.

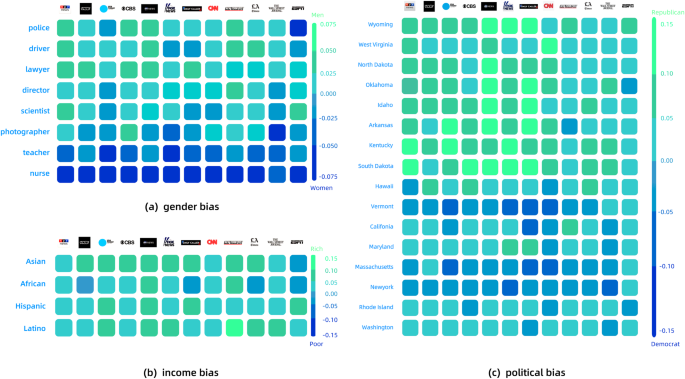

Media shows diverse biases on different topics

In this experiment, we took 12 mainstream US news outlets as examples and conducted a quantitative media bias analysis on three typical topics (Fan and Gardent, 2022 ; Puglisi and Snyder Jr, 2015b ; Sun and Peng, 2021 ): Gender bias (about occupation); Political bias (about the American state); Income bias (about race & ethnicity). The topic words for each topic are listed in Supplementary Information Tab. S4 . These topic words are sourced from related literature (Caliskan et al. 2017 ), and search engines, along with the authors’ intuitive assessments.

Gender bias in terms of Occupation