Daniel Defoe (1660-1731)

Jan 06, 2020

160 likes | 376 Views

Daniel Defoe (1660-1731). Daniel Defoe. 1. Defoe’s life. Born into a family of Dissenters in 1660. Studied modern languages , economics , geography , besides the traditional subjects. Started to write in Whig papers; his greatest achievement was The Review. Daniel Defoe. 1. Defoe’s life.

Share Presentation

- robinson crusoe

- moll flanders

- includes documents

- robinson crusoe 1719

- ron embleton 1930 1988

Presentation Transcript

Daniel Defoe 1. Defoe’s life • Born into a family ofDissentersin 1660. • Studiedmodern languages,economics,geography, besides the traditional subjects. • Started to write inWhigpapers; his greatest achievement wasThe Review. Only Connect ... New Directions

Daniel Defoe 1. Defoe’s life • Queen Anne had himarrested, triedandimprisoned. • Denied his Whig ideas and became asecret agent for the new government. • Started to writenovelswhen • was about sixty. • Died in1731. Ron Embleton (1930-1988), Daniel Defoe. Private Collection. Only Connect ... New Directions

Daniel Defoe 2. Defoe’s works • Robinson Crusoe(1719) • The story of a shipwreck on a desert island • Captain Singleton(1720) • The voyage story of a captain who becomes a pirate • Colonel Jack(1722) • The story of a pickpocket who repents Only Connect ... New Directions

Daniel Defoe 2. Defoe’s works • Moll Flanders(1722) • The adventures of a woman who becomes a thief and a prostitute to survive but finally leads a respectable life • Roxana (1724) • The adventures of ahigh-society woman who exploits her beauty to obtain what she wants. Only Connect ... New Directions

Fictional autobiographies. Daniel Defoe 3. Defoe’s novels: structure • A series ofepisodes and adventures. • Unifying presence of asingle hero. Only Connect ... New Directions

Daniel Defoe 3. Defoe’s novels: structure • Lack of acoherent plot. • Retrospective first-person narration. • The author’spoint of viewcoincides with the main character’s. • Characters presentedthrough their actions. Only Connect ... New Directions

Daniel Defoe 4. Robinson Crusoe: the middle-class hero Robinson shares restlessness with classical heroes of travel literature An act of transgression, of disobedience His isolation on the island after the shipwreck Only Connect ... New Directions

Daniel Defoe 5. Robinson Crusoe: a spiritual autobiography Full of religious references to God, sin, providence, salvation The hero reads the Bible to find comfort and guidance Defoe explores the conflict between economic motivation and spiritual salvation Only Connect ... New Directions

Daniel Defoe 6. Robinson Crusoe: the island The ideal place for Robinson to prove his qualities Robinson organizes a primitive empire Not a return to nature, but a chance to exploit and dominate nature Only Connect ... New Directions

Daniel Defoe 7. Robinson Crusoe: the individual and society The society Robinson creates on the island is not an alternative to but an exaltation of 18th-century England, its ideals of mobility, material productiveness, and individualism Though God is the prime cause of everything, the individual can shape his destiny through action Only Connect ... New Directions

Clear and precise details. Daniel Defoe 8. Robinson Crusoe: the style • Description of the primary qualities of objects. solidity, extension and number • Simple, matter-of-fact and concrete language. Only Connect ... New Directions

Daniel Defoe 9. Moll Flanders Insights into some social problems Set in urban society Women were not able to support themselves legally in 18th-century society Moll is Crusoe’s female counterpart The novel includes «documents» Moll rejects emotional experience Only Connect ... New Directions

Daniel Defoe 9. Moll Flanders • It has insights into some social problemslike crime and the provisions for poor orphans. • Moll rejects emotional experience, seen as an impediment to the accumulation of capital. • The novel includes «documents»– Moll’s memorandums, quoted letters, hospital bills – in order to increase the illusion of verifiable fact. Only Connect ... New Directions

- More by User

Daniel Defoe 1660-1731

1. Defoe's life. Born into a family of Dissenters in 1660.. Daniel Defoe. Studied modern languages, economics, geography, besides the traditional subjects.. Started to write in Whig papers; his greatest achievement was The Review.. Only Connect ... New Directions. 1. Defoe's life. Queen Anne had him

1.34k views • 14 slides

DANIEL DEFOE. HIS LIFE AND WORK. “ROBINSON CRUSOE”

DANIEL DEFOE. HIS LIFE AND WORK. “ROBINSON CRUSOE”. . Daniel Defoe (1660 – 1731) was born in the family of nonconformists (Dissenters)-those who refused to accept the rules of an established national Church.

842 views • 14 slides

Daniel Defoe & “Robinson Crusoe”

Daniel Defoe & “Robinson Crusoe”. Triin Eljas XI a. Daniel Defoe. c.1659 – 24 April 1731 born Daniel Foe son of a wealthy London butcher education in a Dissenting College a practical man. the earliest proponents of the novel one of the founders of the English novel

1.79k views • 9 slides

Daniel Defoe (1660 – 1731)

Daniel Defoe (1660 – 1731). Son of a London Butcher His family was c ommitted to Puritanism Was not accepted by Oxford and Cambridge for he was not an Anglicon Educated at Dissenters ’ Academy Member of Middle Class Political Activist Fought against Roman Catholic King

1.93k views • 9 slides

Daniel Defoe & “Robinson Crusoe”. English 12. Daniel Defoe. c.1659 – 24 April 1731 born Daniel Foe son of a wealthy London butcher education in a Dissenting College a practical man. the earliest proponents of the novel one of the founders of the English novel

834 views • 7 slides

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe. Robinson Crusoe & Moll Flanders. -Daniel Defoe’s biography -Robinson Crusoe -Moll Flanders. Daniel Defoe’s biography.

1.59k views • 30 slides

Daniel Defoe. A True Journalist By Mike Sheridan Sept. 28,2007. Daniel Foe. Aristocratical name change at 35 Protestant family out of favor limited his education Pamphleteer Spy Novelist. Name changes:. We now know him as Daniel DeFoe (better than vonFoe) See link for details.

558 views • 15 slides

Daniel Defoe (1661—1731)

Daniel Defoe (1661—1731). Robinson Crusoe (1719). 1. The hero 1). an embodiment of the Spirit of individual enterprise and colonial expansion; 2). an empire-builder, colonizer, a foreign trader;

430 views • 6 slides

DANIEL DEFOE

DANIEL DEFOE. Daniel Defoe was born in 1661 in London. His famous books are:. Items of Daniel Defoe. It is never late to become clever Fear is disease relaxing the soul To tell a lie to devil is not sin

716 views • 5 slides

Daniel Defoe. By Martin Anderson And Logan Hinderliter. Early Life. Born to James and Alice Foe of London in 1660 James Foe was a butcher. The Foes were dissenting Protestants, Protestants that didn’t belong to the Church of England. Defoe studied at Charles Morton's Academy in London.

550 views • 11 slides

Daniel Defoe. Background of the Author. Daniel Defoe has been called the father of journalism. To many of his contemporaries, he was a man who sold his pen to the political party in office and so lacking integrity.

895 views • 13 slides

Born as Daniel Foe founder of English novel Masterpiece: Robinson Crusoe. Daniel Defoe (1660-1731). Daniel Defoe (1660-1731). Biography: Born into a butcher’s family son of James Foe, a tallow chandler ( 动物油脂杂货商 ) education from a dissenting academy

871 views • 20 slides

Daniel Defoe (1661-1731) Father of English Novel

Daniel Defoe (1661-1731) Father of English Novel. Outline of the lecture. Defoe’s life and his literary career Close reading: Selected chapter On characterization of Robinson Crusoe On point of view On theme Term: realism Element of novel.

989 views • 42 slides

Daniel Defoe (1661-1731) Father of English Novel. Key Points and Difficulties ( 重点与难点 ). ◆ Daniel Defoe’s artistic features ( 笛福的艺术特征 ) ◆ Approaches to read novels ( 欣赏小说文本的方法 ) ◆ Characterization in Robinson Crusoe ( 鲁宾逊中的人物刻画 )

741 views • 14 slides

2.23k views • 14 slides

403 views • 30 slides

604 views • 42 slides

Daniel Defoe

(1660-1731)

Who Was Daniel Defoe?

Daniel Defoe became a merchant and participated in several failing businesses, facing bankruptcy and aggressive creditors. He was also a prolific political pamphleteer which landed him in prison for slander. Late in life he turned his pen to fiction and wrote Robinson Crusoe , one of the most widely read and influential novels of all time.

Daniel Foe, born circa 1660, was the son of James Foe, a London butcher. Daniel later changed his name to Daniel Defoe, wanting to sound more gentlemanly.

Defoe graduated from an academy at Newington Green, run by the Reverend Charles Morton. Not long after, in 1683, he went into business, having given up an earlier intent on becoming a dissenting minister. He traveled often, selling such goods as wine and wool, but was rarely out of debt. He went bankrupt in 1692 (paying his debts for nearly a decade thereafter), and by 1703, decided to leave the business industry altogether.

Acclaimed Writer

Having always been interested in politics, Defoe published his first literary piece, a political pamphlet, in 1683. He continued to write political works, working as a journalist, until the early 1700s. Many of Defoe's works during this period targeted support for King William III, also known as "William Henry of Orange." Some of his most popular works include The True-Born Englishman, which shed light on racial prejudice in England following attacks on William for being a foreigner; and the Review , a periodical that was published from 1704 to 1713, during the reign of Queen Anne, King William II's successor. Political opponents of Defoe's repeatedly had him imprisoned for his writing in 1713.

Defoe took a new literary path in 1719, around the age of 59, when he published Robinson Crusoe , a fiction novel based on several short essays that he had composed over the years. A handful of novels followed soon after—often with rogues and criminals as lead characters—including Moll Flanders , Colonel Jack , Captain Singleton , Journal of the Plague Year and his last major fiction piece, Roxana (1724).

In the mid-1720s, Defoe returned to writing editorial pieces, focusing on such subjects as morality, politics and the breakdown of social order in England. Some of his later works include Everybody's Business is Nobody's Business (1725); the nonfiction essay "Conjugal Lewdness: or, Matrimonial Whoredom" (1727); and a follow-up piece to the "Conjugal Lewdness" essay, entitled "A Treatise Concerning the Use and Abuse of the Marriage Bed."

Death and Legacy

Defoe died on April 24, 1731. While little is known about Defoe's personal life—largely due to a lack of documentation—Defoe is remembered today as a prolific journalist and author, and has been lauded for his hundreds of fiction and nonfiction works, from political pamphlets to other journalistic pieces, to fantasy-filled novels. The characters that Defoe created in his fiction books have been brought to life countless times over the years, in editorial works, as well as stage and screen productions.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Daniel Defoe

- Birth Year: 1660

- Birth City: London

- Birth Country: United Kingdom

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: English novelist, pamphleteer and journalist Daniel Defoe is best known for his novels 'Robinson Crusoe' and 'Moll Flanders.'

- Fiction and Poetry

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Academy at Newington Green

- Death Year: 1731

- Death date: April 24, 1731

- Death City: London

- Death Country: United Kingdom

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Daniel Defoe Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/daniel-defoe

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: October 26, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Famous British People

Mick Jagger

Agatha Christie

Alexander McQueen

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Anya Taylor-Joy

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Prince William

Where in the World Is Kate Middleton?

Daniel Defoe

1. daniel defoe.

- Preferences

17. DANIEL DEFOE - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

17. DANIEL DEFOE

Daniel defoe (1660-1731) 1. defoe s life born into a family of dissenters in 1660. daniel defoe studied modern languages, economics, geography, besides the ... – powerpoint ppt presentation.

- Born into a family of Dissenters in 1660.

- Studied modern languages, economics, geography, besides the traditional subjects.

- Started to write in Whig papers his greatest achievement was The Review.

- Queen Anne had him arrested, tried and imprisoned.

- Denied his Whig ideas and became a secret agent for the new government.

- Started to write novels when

- was about sixty.

- Died in 1731.

- Robinson Crusoe (1719)

- The story of a shipwreck on a desert island

- Captain Singleton (1720)

- The voyage story of a captain who becomes a pirate

- Colonel Jack (1722)

- The story of a pickpocket who repents

- Moll Flanders (1722)

- The adventures of a woman who becomes a thief and a prostitute to survive but finally leads a respectable life

- Roxana (1724)

- The adventures of a high-society woman who exploits her beauty to obtain what she wants.

- Fictional autobiographies.

- A series of episodes and adventures.

- Unifying presence of a single hero.

- Lack of a coherent plot.

- Retrospective first-person narration.

- The authors point of view coincides with the main characters.

- Characters presented through their actions.

- Clear and precise details.

- Description of the primary qualities of objects.

- Simple, matter-of-fact and concrete language.

- It has insights into some social problems like crime and the provisions for poor orphans.

- Moll rejects emotional experience, seen as an impediment to the accumulation of capital.

- The novel includes documents Molls memorandums, quoted letters, hospital bills in order to increase the illusion of verifiable fact.

PowerShow.com is a leading presentation sharing website. It has millions of presentations already uploaded and available with 1,000s more being uploaded by its users every day. Whatever your area of interest, here you’ll be able to find and view presentations you’ll love and possibly download. And, best of all, it is completely free and easy to use.

You might even have a presentation you’d like to share with others. If so, just upload it to PowerShow.com. We’ll convert it to an HTML5 slideshow that includes all the media types you’ve already added: audio, video, music, pictures, animations and transition effects. Then you can share it with your target audience as well as PowerShow.com’s millions of monthly visitors. And, again, it’s all free.

About the Developers

PowerShow.com is brought to you by CrystalGraphics , the award-winning developer and market-leading publisher of rich-media enhancement products for presentations. Our product offerings include millions of PowerPoint templates, diagrams, animated 3D characters and more.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

1 Defoe’s Life and Times

Brian Cowan is Associate Professor and Canada Research Chair in Early Modern British History at McGill University. He is the author of The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse (2005), editor of The State Trial of Doctor Henry Sacheverell (2012), and coeditor of The State Trials and the Politics of Justice in Later Stuart England (2021).

- Published: 18 December 2023

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter situates Daniel Defoe’s life and writings in the literary, social, and political history of Britain from the Restoration to the period following the Hanoverian succession. Defoe was born in the wake of the regicidal revolution that produced the Civil War and a brief period of republicanism; he lived his early life in the context of the legal clampdown on religious dissent, and he started out as a businessman. He was an avid supporter of the Revolution of 1688, which established the Protestant succession and religious toleration for nonconformists. After establishing these wider contexts, the chapter surveys Defoe’s writing career: his reputation in his lifetime as a whiggish and seditious ‘scribbler’ of topical wrings for payment, and the growth in his ‘literary’ reputation in the later eighteenth century. As well as his politics and his writings, the chapter discusses portraits of Defoe and his earnings from his writings.

Zealous Revolutioner

Daniel Defoe was born in the wake of one revolution, and he lived to help build the legacy of yet another one which he lived through. Defoe’s life and times were thus shaped by two great revolutions of the Stuart age: the regicidal revolution of 1649 and the ‘glorious’ revolution of 1688–9. Defoe’s birth coincided with the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660—a moment that attempted, unsuccessfully, to efface the memory of two decades of civil wars and regime changes that preceded it. As a young man, Defoe joined the fight against the prospect of a popish successor to the throne by supporting the Duke of Monmouth’s ill-fated rebellion ( Appeal , 28). 1 Although Monmouth’s attempted coup d’état failed in 1685, William of Orange’s Glorious Revolution in 1688 succeeded beyond expectations. Henceforth, Defoe would defend the rectitude and greatness of ‘the Revolution’ as it would thereafter be known to him and his contemporaries. The revolutionary King William III became Defoe’s hero, and throughout his life Defoe would insist that he had been a close confidant and advisor to the revolutionary king. Much of Defoe’s political activities in the succeeding decades would be devoted to defending William’s Glorious Revolution and to securing its enduring legacy. By the time of Defoe’s death in 1731, the Jacobite menace that had threatened to undo the Glorious Revolution had receded, and the Protestant succession to a now united British throne appeared to be secure as a second Hanoverian king, George II, had succeeded to his throne without contest after the death of his father in 1727.

Defoe wrote ceaselessly about the Glorious Revolution and almost always with great praise and reverence for the nation’s deliverance from the double threat of popery and arbitrary government that it heralded, but the regicidal revolution was never far from his mind either. He drew upon the later Stuart debates about the English civil wars when he crafted his fictional Memoirs of a Cavalier (1720), a work which Nicholas Seager has argued was an attempt to moderate between the more partisan views of the war promoted by the posthumous publication of works such as John Toland’s edition of Edmund Ludlow’s Memoirs (1698–9) or the Earl of Clarendon’s History of the Rebellion (1702–4). Pat Rogers notes that Defoe’s Tour thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724–6) ‘never openly takes sides on the issues of the English Civil War, when (as often happens) the narrator comes on remnants of that great and divisive struggle’. 2 The challenge for Defoe, as for many of his contemporaries, was to acknowledge the divisive legacy of the civil wars without obviously aligning himself with either the regicidal or absolutist extremes of either side.

For most of his contemporaries, however, Defoe’s views on the civil war era were far from moderate. Unlike the majority of his contemporaries, Defoe saw the revolution that ended Charles I’s reign as an event akin to the more respectable glorious revolution that ended James VII and II’s rule. In a pamphlet published early in Anne’s reign, Defoe shocked many of his readers by declaring that the only difference between the two revolutions ‘lyes here, the Whigs in 41. to 48. took up Arms against their King; and having conquer’d him, and taken him Prisoner, cut off his Head, because they had him : The Church of England took Arms against their King in 88. and did not cut off his Head, because they had him not . King Charles lost his Life, because he did not run away ; and his Son, King James , sav’d his Life, because he did run away ’ ( PEW , iii. 65). A few years later, in the Review (1704–13), Defoe would return to the topic where he would declare that there was little difference between ‘the dry Martyrdom of King James , by his Passive Obedience , Church Subjects; and the wet Martyrdom of King Charles I, by People that never made any such Pretence’. 3

Resistance was the common denominator between the two revolutions for Defoe; unlike most of his contemporaries, Defoe did not shy away from comparing the regicidal revolution with the Glorious Revolution. He made the analogy explicit in the preface to his longest poem, Jure Divino (1706), where he declared, despite acknowledging that ‘some People will not bear the Comparison … That the Parallel between the Civil War, or Parliament War, or Rebellion , call it which you will; and the Inviting over, Joyning with, and Taking up Arms under the Prince of Orange , against King James , seems to me to be very exact, the drawing such a Parallel very just, and the Foundation proceeding, and Issue just the same’ ( SFS , ii. 42, 43–4). Defoe could not understand ‘How any People can then Defend the inviting over the Prince of Orange , to check the Invasions of King James II. and at the same time condemn the taking Arms against the Invasions of King Charles I’ ( SFS , ii. 44). Defoe even went so far as to claim that King James suffered more than his father Charles, whose execution was ‘ Une coup de Grace ’, whereas for James his rebellious subjects ‘were 11 years a Murthering of him, and he languish’d all that while under their Treachery’ ( SFS , ii. 49). Defoe’s point was not to denigrate the Glorious Revolution, it was quite the opposite: he insisted that it had been achieved through resistance to the king’s sovereign power and that resistance had been legitimate.

This was a highly controversial claim to make at the time. Queen Anne’s reign saw the resurgence of a Tory ideology that abhorred all forms of resistance theory, even when applied to the Glorious Revolution. This Tory revanche put establishment Whigs on the defensive, and all but the most radical of them sought to temper their avowal of resistance theory, or even better to avoid the question altogether. Defoe’s refusal to do either horrified many, and his equation of the revolution of 1649 with that of 1688 was explicitly condemned during the trial of Dr Henry Sacheverell. 4 After this official repudiation of his vigorous defence of resistance theory, very few other writers would dare to take it up again later in the eighteenth century.

Defoe was mainly known in his lifetime as a seditious writer with dangerously unorthodox views about resistance and revolution, but this is not how Defoe saw himself. Defoe consistently presented himself as a political moderate, a pragmatist, and a skilful politician who had access to and the esteem of the good and the great, above all his two heroes, King William III and the wily Robert Harley, whom Defoe did not hesitate to call ‘Prime Minister’ ( Letters , 31). As important as they are for understanding Defoe’s own self-regard and his public self-fashioning, these characteristics were guises adopted by a mercurial figure who delighted in presenting himself as a key player in the frenzied politics of post-revolutionary Britain. Defoe was not entirely wrong about this: through his varied and prolific writings, he managed to find himself embroiled in some of the major debates of his day. He wrote on politics, religion, economics, education, social policy, travel, and geography; he documented current events as well as writing histories.

Defoe’s reputation in his own day was indelibly associated with his politics, and particularly his enthusiasm for the Revolution. When John Oldmixon identified Defoe as ‘a Zealous Revolutioner and Dissenter’ for the readers of his History of England (1735), he was merely repeating a standard opinion of the writer’s significance. 5 Defoe’s emergence in literary public opinion as a writer of genius emerged only posthumously, and even then the process was a slow one [ see chapter 33 ]. Robert Shiells was an early defender when he wrote the first substantive (albeit brief) biography of Defoe in The Lives of the Poets (1753), in which he argued against the derisive views of Pope and other arbiters of literary taste: ‘De Foe can never with any propriety, be ranked amongst the dunces, for whoever reads his works with candour and impartiality, must be convinced that he was a man of the strongest natural powers, a lively imagination, and solid judgment, which … ought not only to screen him from the petulant attacks of satire, but transmit his name with some degree of applause to posterity’. Even so, Shiells noted that Defoe’s ‘considerable name’ was earned by ‘his early attachment to the revolution interest, and the extraordinary zeal and ability with which he defended it’. Defoe was ‘best known for the True-Born Englishman’, Sheills added. 6

It was only in the later eighteenth century, and particularly after the enterprising bookseller Francis Noble began to attribute fictional narratives such as Moll Flanders (1722) and Roxana (1724) to Defoe, that Defoe’s reputation as an author of literary distinction, rather than a political writer who defended the Revolution interest, began to take shape. 7 In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Defoe’s reputation as a ‘master of fictions’, grounded largely on the growing esteem for the novels he wrote between 1719 and 1724, dominated critical interest in him as a canonical author. Defoe is now probably best known as a fiction writer, and thanks largely to the prominence of his fictional writings in Ian Watt’s influential The Rise of the Novel (1957), he is a key figure in debates about the ‘rise of the novel’ in the eighteenth century. Taken as a whole, Defoe’s oeuvre (insofar as it can be known) illustrates the changing fortunes of literary production from the age of revolutions into which he was born to the subsequent century of politeness and sensibility in which his writings proved to become increasingly admired, reprinted, and in due course canonized.

He did not set out to be a writer, let alone a great one. Daniel Defoe was born as Daniel Foe, the son of James Foe (d. 1706), a successful London tallow chandler whose Puritanism would become known in his son’s lifetime as ‘Dissent’ due to the ecclesiastical schism created by the ‘Clarendon Code’ of penal laws enacted in the early years of the Restoration. 8 Young Daniel grew up in the religious culture of late Puritanism and the political culture of what Mark Goldie has identified as ‘Puritan Whiggery’ [ see chapter 17 ]. His family’s minister was the renowned Presbyterian Samuel Annesley, and he was educated at the Reverend Charles Morton’s dissenting academy in Newington Green. It was in this nascent culture of Dissent that the young Defoe was raised. He was encouraged to begin training as a minister; had he done so, he would have been one of the first generation of Dissenting ministers wholly educated and ordained entirely outside the Church of England, but this was not to be. 9 It is possible that Defoe practised as a Dissenting preacher for a while when he was a young man in his twenties, and he would later pen a few lay sermons that were published, but he publicly acknowledged that ‘the Pulpit is none of my Office—It was my disaster first to be set a-part for, and then to be set a-part from the Honour of that Sacred Employ’. 10

Daniel chose instead to follow a secular life of trade and, ultimately, of professional writing. His life and his writings reflect the final phase of Puritanism in the age of revolutions. Certain Puritan themes remained central to Defoe’s worldview: the importance of divine providence; the primacy of Biblical scripture as a guide to the divine plan; the centrality of faith to one’s spiritual life; his orthodox trinitarianism; his plain style of prose expression; his respect for and even practice of lay preaching; and a rigorous sense of personal and social morality that found expression in his support for (and even participation in) the ‘reformation of manners’ movement. 11 Defoe’s hostility to the theatre, which he described in distinctly Puritan terms as ‘Nurseries of Crime, Colleges, or rather Universities of the Devil—Satan’s Workhouse, where all the Manufactures of Hell are propagated’, is exemplary of a worldview in which sin was omnipresent and a source of fear and social concern [ see chapter 4 ]. 12 Indeed, Defoe’s self-proclaimed conception of his position as a writer depended upon his notion that a satirist aims to provoke and chasten the consciences of his readers [ see chapter 11 ]. As he put it in the preface to The True-Born Englishman (1700/1), ‘ The End of Satyr is Reformation ’ ( SFS , i. 83). 13 Defoe’s vocation as a public satirist reflected the evolution of trends within Dissenting culture, particularly as Dissent came to reconcile itself with the emergence of a post-revolutionary public sphere. 14

Over the course of Defoe’s lifetime, the social and cultural worlds of Dissent became more securely urban and mercantile, just like Defoe himself. Without ever abandoning his piety, Defoe turned his talents towards the world around him. He sought to understand and describe that world for his contemporaries, and as it happens his works have become an invaluable guide to his world for later historians of his age. 15

The Scribbler

Defoe’s life as a writer mirrored substantial changes in English literary culture over his lifetime. Defoe claimed that his first publication was a 1683 tract in which he argued against supporting the Ottoman Turks in their war against the Catholic Habsburgs—a point ‘which was taken very unkindly indeed’ by his Whig friends—but no copy of this work survives, and it is unclear whether it ever existed ( Appeal , 51). The first work of Defoe’s which survives and can be definitively attributed to him is A Letter to a Dissenter from a Friend at the Hague (1688), in which he warned his Dissenting friends against the dangers of allying with King James II ( Appeal , 51–2). He published at least ten more tracts in the 1690s. 16 Defoe is most often categorized as a characteristically eighteenth-century author, partly because the bulk of his publications were produced after 1700, but also because the concept of a ‘long eighteenth century’ beginning with the Restoration (and coincidentally the putative year of Defoe’s birth) has long operated as a category of periodization in English literary and historical studies. The fact that Defoe’s literary reputation, and particularly his reputation as a novelist, only grew in esteem over the course of the rest of the eighteenth century has helped to reinforce this notion of him as an eighteenth-century author. 17 Yet it is worth remembering that Defoe lived more than half of his life in the chronological seventeenth century, and his mental world was in many ways ensconced within the concerns of that revolutionary age. Like so many of his contemporaries, Defoe knew that the revolutions of the Stuart era had not been fully settled. They had simply created possibilities for seeing the world anew, and no one of his generation did more to exploit those new mental horizons in print than Defoe.

Print is the key for understanding Defoe’s significance in his own day, but the print culture of his lifetime differed from the late Hanoverian and Victorian world that would canonize him as a great author. Defoe wrote in a time when authorship was considered to be an act rather than a profession, and quite often writing was a suspect act that was liable to get one in trouble. 18 Defoe learned this the hard way when he was prosecuted for seditious libel in 1703 for his authorship of The Shortest-Way with the Dissenters (1702). Defoe’s experience of imprisonment—a large fine and three days of spectacular punishment in the pillory on 29, 30, and 31 July 1703—was a key turning point in his life: it signalled his moment of transition from a controversial scribbler to a writer with privileged contacts at the highest levels of government. 19 Robert Harley, then Speaker of the House of Commons and soon to be made secretary of state for the Northern Department, contacted Defoe while he was imprisoned in Newgate with an offer of patronage and relief from his suffering.

In his personal apologia published after the Hanoverian accession, An Appeal to Honour and Justice (1715), Defoe drew a parallel between this offer from Harley and the Biblical encounter between Christ and the faithful blind man, who when asked ‘ What wilt thou that I should do unto thee? ’ replied ‘My Answer is plain in my Misery, Lord, that I may receive my Sight ’ ( Appeal , 12). 20 To see, for Defoe, was to write. Harley’s reprieve gave Defoe a chance to write again. Not long thereafter, Defoe would publish his Essay on the Regulation of the Press (1704), which argued against the restoration of pre-publication licensing, but also that authorial accountability should be established by a requirement that every published work should include the name of the author. Furthermore, he thought that authors should own ‘an undoubted exclusive Right to the Property’ of their works ( PEW , viii. 158). Defoe was possibly the earliest advocate for an author’s property rights in their writings; he argued for something closer to a common law right of property in an author’s works: ‘A Book is the Author’s Property, ’tis the Child of his Inventions, the Brat of his Brain’. 21 This argument did not prevail in law, however. When a change in copyright came with the coming into effect of the Statute of Anne (8 Ann. c. 19) in 1710, property rights were granted not to authors but to booksellers, and only for a term of fourteen years for ‘new books’, with the possibility of extension for a second fourteen-year term. Copyright for ‘existing books’ was granted to their present owners for twenty-one years. The terms of the act would remain controversial, and Defoe’s arguments for a common right of intellectual property in written works would be taken up most enthusiastically by the booksellers rather than authors until the matter was definitively settled in favour of fixed statutory limits by the Lords’ decision in Donaldson v. Becket (1774). 22

Defoe’s writing career, despite his prodigious efforts and his relative success as a professional scribbler, relied upon a remarkably diverse stream of income from various sources, amongst which payment for copy was one of the least important. To be sure, he prospered more than most of his Grub Street contemporaries. Robert Harley’s patronage was crucial in allowing Defoe to travel extensively whilst also maintaining his prodigious periodical and pamphlet writing in Anne’s reign. Estimates regarding the amount of patronage Defoe received from the government vary considerably. An anonymous pamphlet, The Republican Bullies (1705), claimed that he received ‘a handsome Allowance, (viz.) 100 l . for the first Volume’ of the Review . Novak estimates that he received £200 per annum from government secret service funds whilst writing the Review and other works; Downie’s ‘meanest estimate’ is an annual income of £250 that may have been as high as £400; Backscheider contends that Defoe earned somewhere between £400 and £500 per year from at least 1707 until the death of the queen, thanks to his connections to Harley, Sunderland, and Godolphin. 23 Contemporaries certainly thought Defoe was well paid. Oldmixon claimed that Harley ‘paid Foe better than he did Swift , looking on him as the shrewder Head of the Two for Business’. 24

After Harley’s fall from power and the Hanoverian accession in 1714, Defoe became more reliant upon commercial income from his relationships with the publishing industry; here too he was relatively well paid for his efforts. For pamphleteering, John Baker paid Defoe two guineas for every 500 copies of a sixpence pamphlet during the latter years of Anne’s reign. Richard Janeway was more generous: on at least one occasion, he paid four guineas plus some free copies for every 1,000 pamphlets sold. Defoe had a similar arrangement with William Taylor, the publisher for the first edition of Robinson Crusoe . He was paid £10 for the original print run of 1,000 copies of the first volume, and £10 10 s . more upon the printing of the second volume in 1,000 copies, along with provision for a supplementary payment of £5 if 500 copies of that printing were sold. For the third volume of Crusoe , Defoe was to be paid 15 guineas for every 1,000 copies printed. 25

But it was through his ownership of several periodicals that Defoe may have made serious profits from his writing; Backscheider estimates that he earned perhaps as much as £1,200 per year by the 1720s. 26 As chief proprietor for the Review , Defoe had supplemented his small income from sales of the periodical, which was barely profitable, by selling advertisement space in its pages, and by collecting payments from readers for additional services rendered, such as offering advice on casuistic matters, problem solving, or in gratitude for having written something desirable in its pages. McVeagh estimates that he may have earned as much as £50 per year from advertisement revenues, but he garnered the rather more substantial sum of £1,300 annually from his ‘Scandal Club business’, although he only kept the latter running for less than two years from 1704 to 1705. The Scandal Club offered a section devoted to questions from readers, often of a personal or moral nature, that would be answered in the journal. Or, as Defoe put it, ‘Here are Questions in Divinity, Morality, Love, State, War, Trade, Language, Poetry, Marriage, Drunkenness, Whoring, Gaming, Vowing, and the like’. 27 The business of answering questions and publishing puff pieces for readers was apparently a lucrative one. Defoe’s erstwhile friend and Grub Street competitor John Dunton complained that the Review ’s ‘interloping’ on Dunton’s idea of answering readers’ cases of conscience cost Dunton £200 in lost income; he also accused Defoe of ‘re-printing a Copy’ of one of Defoe’s earliest published poems, The Character of the Late Dr. Samuel Annesley (1697), which had allegedly been given to Dunton for publication but was in fact printed and sold by the bookseller Elizabeth Whitlock instead. 28 After the Review , Defoe would also manage periodicals such as Mercator (26 May 1713–20 July 1714), the Monitor (22 April–7 August 1714), the Manufacturer (30 October 1719–9 March 1721), the Commentator (1 January–6 September 1720), and the Director (5 October 1720–16 January 1721), and it was from these publications that he may have profited handsomely.

These earnings were considerable for a writer of his day, and Defoe may be considered one of the few Grub Street scribblers who managed to earn a respectable living from his pen. Samuel Johnson’s annual income was under £100 for the first twenty years of his London career, which roughly coincided with the two decades succeeding Defoe’s death in 1731. 29 Nevertheless, Defoe did not rely upon income from his writing alone, and he maintained a diversified income stream throughout his life.

Along with his work as a writer, Defoe remained active as a businessman and a high-risk investor in various projects [ see chapter 14 ]. His first major investment was his marriage on 1 January 1684 to a cooper’s daughter, Mary Tuffley (1665–1732), who brought him a dowry of £3,700. This considerable sum allowed Defoe the capital and business networks he required to set up his trade as a wholesale hosier, and it did not take long before he had expanded his ventures to include overseas imports and exports in other wholesale goods such as tobacco, logwood, wine, spirits, and cloth. Some of his more speculative investments turned out to be unfortunate, such as his purchase of seventy civet cats for about £850 in April 1692. Two months later, he made an investment of £200 in a diving bell scheme designed to recover sunken treasure. Both cases resulted in lawsuits and recriminations with his business partners, including with his own mother-in-law, Joan Tuffley. In addition to these cases, Defoe’s liabilities extended well beyond his ability to pay, and he found himself with £17,000 of debt claimed by his creditors. By the end of the year, Defoe was bankrupt and committed to the Fleet Prison on 29 October 1692; he was released upon recognizances but returned again on 12 February 1693. 30

This was a first-hand experience with what he would call ‘the Poverty of Disaster’ which ‘falls chiefly on the middling Sorts of People, who have been Trading-Men, but by Misfortune or Mismanagement, or both, fall from flourishing Fortunes into Debt, Bankruptcy, Jails, Distress and all Sorts of Misery’. 31 In several works, Defoe defended the practice of declaring bankruptcy. He saw it as an honest and honourable recourse for a trader who had run into unforeseen financial difficulties: ‘Certainly honesty obliges every man, when he sees that his stock is gone, that he is below the level, and eating into the estates of other men, to put a stop to it; and to do it in time, while something is left’ ( RDW , vii. 83). Bankruptcy and, even more so, imprisonment for debt were not uncommon experiences for middle-class traders in eighteenth-century England. Thirty-three thousand businesses went bankrupt in the eighteenth century, and over 300,000 people were imprisoned for debt. It has recently been estimated that perhaps 7% of all London men would experience incarceration for debt during their lifetime. 32 In 1709, Defoe estimated that there were 80,000 men imprisoned for debt in England, ‘most of whom have Families, Wives, and Children innumerable, whose Miseries and Disasters are deriv’d from’ such incarceration. Defoe’s passion for this matter derived from his personal experiences with imprisonment. 33

Somewhat miraculously, Defoe managed to settle his terms with his creditors, and he negotiated a relatively quick release from prison in 1693. It is not clear how he accomplished this. Defoe credited ‘the late kings Bounty’ ( Letters , 17) with his financial salvation. Soon thereafter he ‘was invited by some Merchants … to settle at Cadiz in Spain ’, but he demurred and instead was able to secure a new position from the crown ‘without the least application’ ( Appeal , 5–6) as an accountant to the commissioners of the glass duty after his release.

Defoe managed around the same time to open a brick and pantile factory in Tilbury that promised to become very profitable given the growing market for building trades in the London area. He claimed to have employed ‘a hundred Poor Familys at work and … Generally Made Six hundred pound profit per Annum’ ( Letters , 17). He was forced to sell the factory as a result of his prosecution for The Shortest-Way . 34 The timing of the sale was truly unfortunate, as it occurred just before the great storm of 26–7 November 1703, an event that immediately created substantial new demand for the factory’s products. Rather than profiting from brick and pantile sales from the great rebuilding after the storm, Defoe turned to the book trade and rapidly published a series of tracts relating to the natural disaster: The Lay-Man’s Sermon ; a poem, An Essay on the Late Storm ; and a journalistic account titled simply The Storm (1704). 35 Although Defoe’s business interests along with their accompanying debts would persist through his life, his two moments of imprisonment and prosecution for bankruptcy in 1692–3 and later for seditious libel in 1703 proved to be decisive in focusing his attention towards writing as both a source of income and a vocation [ see chapter 12 ].

Defoe’s literary production was shaped by his experience of a series of personal misfortunes and twists of fate that were also key moments in his life. The bankruptcy proceedings prompted Defoe’s emergence as a well-known writer, mainly of poems and satires, in the 1690s. Harley’s reprieve granted after Defoe’s second imprisonment and his pillorying a decade later initiated a new phase of work as propagandist for the government, in which he devoted himself primarily to journalism and pamphleteering [ see chapters 6 , 7 , and 20 ]. After the Hanoverian accession resulted in the fall from power of his primary patron, Robert Harley, Defoe would once again reshape his literary career as he began to concentrate on crafting and marketing narratives (both fictional and non-fictional or an amalgam of both) and guidebooks and didactic manuals such as The Family Instructor (1715, 1718), The Compleat English Tradesman (1725–7), and A Tour thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724–6) [ see chapters 3 , 5 , and 8 ].

Self-Fashioning in Print

Although Defoe is best known today as a novelist and a political commentator or propagandist, for much of his career as a writer he conceived of and presented himself to his publics primarily as a satirist. Throughout his lifetime and well afterwards, Defoe was best known as ‘the author of the True-Born Englishman’, a work that he significantly subtitled ‘a satyr’. The first authorized collection of Defoe’s writings was titled A True Collection of the Writings of the Author of the True Born English-man (1703); this was followed soon thereafter by A Second Volume of the Writings of the Author of the True-Born Englishman (1705). 36 Both volumes were reissued in 1710 as a two-volume collection. In 1721, Defoe published yet another collection of his writings with the title The Genuine Works of Mr. Daniel D’Foe, Author of The True-Born English-Man, a Satyr , which was largely a reprint of the earlier anthologies. These collections of Defoe’s works sold well throughout his lifetime, and they were priced high enough to suggest that the works must have attracted a relatively wealthy readership. 37

These various editions of Defoe’s collected works, curated and edited by their author, offer some significant clues as to how Defoe conceived of his own authorial persona. The prominence of The True-Born Englishman as his most noteworthy work is clear. Perhaps because of the patriotic connotations evoked by the title, Defoe consistently wished to be known as the author of this ‘satiric’ poem. The True-Born Englishman was the first work of his that sold well. Although he claimed that the work brought him no personal profit, Defoe proudly announced (with no doubt a substantial amount of hyperbole) that it had earned the booksellers over £1,000 profit through sales of nine authorized and twelve pirated editions, including 80,000 copies sold for ‘2d. or at a Penny’. 38 The size of these print runs is likely exaggerated: more reliable evidence for the authorized printing of Henry Sacheverell’s best-selling sermon, The Perils of False Brethren (1709), indicates that the work sold just under 54,000 copies, and it is highly unlikely that Defoe’s poem outsold Sacheverell’s sermon. 39

As a defence of King William and the Glorious Revolution, The True-Born Englishman suited Defoe’s public self-fashioning as a vociferous defender of the Revolution cause and an intimate friend of the king. The scandal and spectacular punishment associated with The Shortest-Way may have brought Defoe more notoriety, his continuous writing for the Review for almost a decade may have secured him the nickname ‘Mr. Review’, and his authorship of Robinson Crusoe would seal his posthumous reputation as a novelist of great genius, but it was The True-Born Englishman that Defoe would continually refer back to as his most noteworthy work.

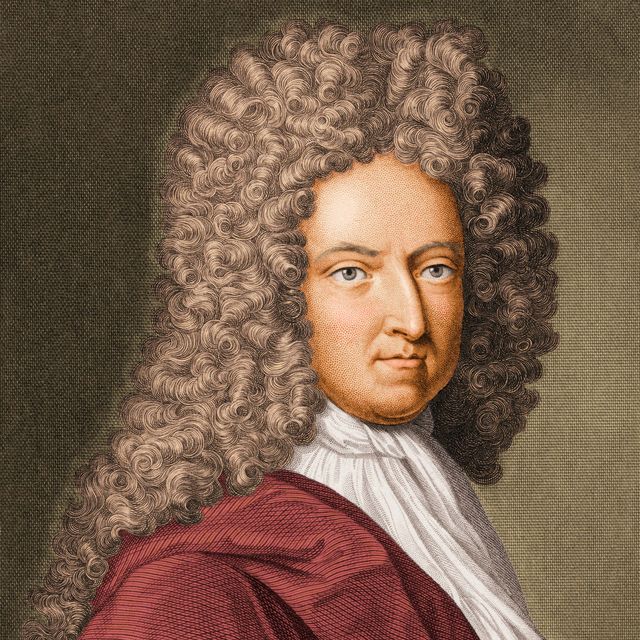

The frontispiece to Defoe’s True Collection is an engraved portrait of the author (Figure 1.1 ). This portrait, drawn by Jeremiah Tavernier and engraved by Michael Van der Gucht, presented Defoe as he wished to be seen by his readers. He appeared handsome, well dressed, and spectacularly bewigged with a large perruque. Below his portrait appeared the words ‘Daniel DeFoe, author of the Trueborn Englishman’, along with a coat of arms. This rather august self-presentation was advertised for sale in the Daily Courant for 22 July 1703, just one week before Defoe’s first day of punishment in the pillory. It was clearly designed to counter the now common image of Defoe as a rogue writer and a convicted criminal, and perhaps to capitalize upon his new-found notoriety. It also made the bourgeois tradesman appear as a gentleman worthy of respect. The portrait may have been printed and sold independently from the work. Although there is no evidence that such individualized sales were advertised, a copy of Defoe’s pamphlet Advice to All Parties (1705) has the portrait inserted as a frontispiece. It also appears as the frontispiece to a copy of Defoe’s Second Volume of the Writings (1705) and was tipped in to serve as the frontispiece for some editions of his Jure Divino as well. There are minor differences in the engravings for these works: some appear with attribution of the artists Tavernier and Van der Gucht, others do not; Defoe’s eyes are reworked in later prints. 40 The image was obviously popular enough to demand a new execution of the original drawing for later printings.

Aside from the frontispiece to the True Collection , the only other work of Defoe’s to include an authorial portrait was his major poem Jure Divino (1706) (Figure 1.2 ). Unlike his other works, most of which were composed and published with astounding speed (often in less than a year), Defoe spent five years working on this poem. He also experimented with a subscription model for marketing and selling the folio edition for the substantial price of fifteen shillings. The experiment did not go as planned, however: the list of subscribers was not as substantial as he had hoped, and Defoe ultimately had to apologize for delays in publication. By the time it appeared, pirate editions were already in the works and would soon appear. 41 Defoe must have hoped that this publication would secure his reputation as a poet of major importance, and therefore he commissioned a more detailed and impressive version of the True Collection portrait from Van der Gucht, claiming that it had been ‘prepar’d at the request of some of my Friends who are pleas’d to value it more than it deserves’ ( Letters , 124). It was printed as the frontispiece for the folio edition of Jure Divino . Here, Defoe’s genteel dress and long wig appear even more elaborately detailed. The coat of arms is reproduced below, along with the Latin epigraph ‘ laudatur et alget ’, identified as from Juvenal’s first satire. The quote from Juvenal ( Satires 1.74) reads ‘ probitas laudatur et alget ’, or ‘honesty is praised and is left to shiver’. Defoe significantly omits probitas from his epigraph, thus suggesting that it was the honest author himself who had once been praised for his work and then cruelly abandoned afterwards, which may be a reference to his prosecution for seditious libel in 1703.

Frontispiece, Daniel Defoe, A True Collection of the Writings of the Author of the True Born English-man (1703). Courtesy of McGill University Library, Rare Books and Special Collections, shelf mark PR3401 1703.

Frontispiece, Daniel Defoe, Jure Divino: A Satyr. In Twelve Books. By the Author of The True-Born Englishman . Courtesy of Lilly Library, University of Indiana, Bloomington, shelf mark PR3404 .J89.

This portrait may also have been sold independently. Defoe noted in a letter to his friend John Fransham that it cost one shilling ( Letters , 124), a price that was close to the market rate for folio sized portraits. A few years later, unframed mezzotint print portraits of Henry Sacheverell would sell for one shilling and six pence. The British Museum and the Wellcome Library both hold a singular copy of the print in which the epigraph from Juvenal is printed around the oval coat of arms and the subject is identified below as ‘Daniel De Foe, author of the True Born Englishman’. 42 These separates may have been sold for a shilling each at print shops or from booksellers, although no contemporary advertisements for them seem to have been placed in the newspaper press. Ads for such portraits tended to be reserved for clergymen or other figures of a higher social status than the struggling writer and bankrupted trader Defoe.

Defoe’s investment in commissioning portraits for his True Collection and Jure Divino offers useful clues as to how he wished to be seen, and how he wished to have his authorized works recognized by his readers. The authorial portraits are testaments to his attempt to establish himself as a genteel author worthy of respect, rather than as a Grub Street scribbler. This was a cause that he took up in the Review at the same time. He admitted that he could not speak Latin with fluency: ‘Latin, Non ita Latinus sum ut Latine Loqui —I easily acknowledge my self Blockhead enough, to have lost the Fluency of Expression in the Latin’. This did not deter him however from challenging the Whig journalist John Tutchin (who had provoked the ire that had inspired The True Born Englishman ) to a translation contest. He dared his adversary to translate one Latin, one French, and one Italian author into English and then to retranslate each, ‘the English into French, the French into Italian, and the Italian into Latin’. Whoever managed to do this best and quickest would owe the other £20, a considerable sum. ‘And by this’, Defoe declared, ‘he shall have an Opportunity to show the World, how much De Foe the Hosier, is Inferior in Learning, to Mr. Tutchin the Gentleman’. 43 Tutchin did not take him up on the challenge. 44 Defoe was aware that his bourgeois and Dissenting origins disadvantaged his authorial status as a polite writer, but he never renounced them. Instead, he struggled to convince his contemporaries that even a Dissenter from the middling sorts could outperform his gentleman rivals.