1,500 endangered languages could disappear by the end of the century

With 1,500 languages at risk of being lost, how can we help preserve them? Image: Unsplash/Towfiqu barbhuiya

.chakra .wef-spn4bz{transition-property:var(--chakra-transition-property-common);transition-duration:var(--chakra-transition-duration-fast);transition-timing-function:var(--chakra-transition-easing-ease-out);cursor:pointer;text-decoration:none;outline:2px solid transparent;outline-offset:2px;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-spn4bz:hover,.chakra .wef-spn4bz[data-hover]{text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-spn4bz:focus-visible,.chakra .wef-spn4bz[data-focus-visible]{box-shadow:var(--chakra-shadows-outline);} Johnny Wood

Listen to the article

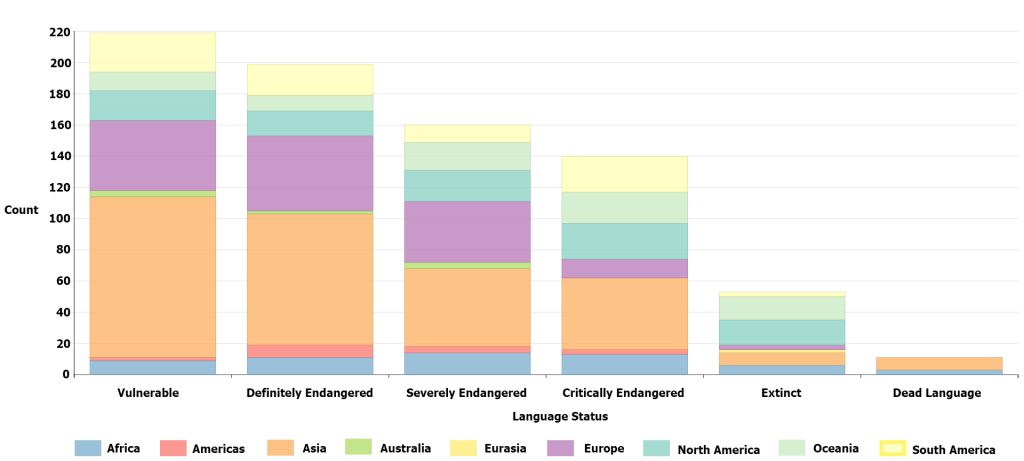

- Around 1,500 known languages may no longer be spoken by the end of this century.

- Current levels of language loss could triple in the next 40 years.

- Greater education and mobility marginalize some minor languages.

- One language per month could disappear, without intervention.

There are 7,000 documented languages currently spoken across the world, but half of them could be endangered , according to a new study. It is predicted that 1,500 known languages may no longer be spoken by the end of this century. Researchers from The Australian National University (ANU) analyzed thousands of languages to identify factors that put endangered ones at risk. The findings highlight a link between higher levels of schooling and language loss, as regionally dominant languages taught in class often overshadow indigenous tongues.

Have you read?

Ranked: the countries with the most linguistic diversity, besides english and spanish, which language do you think is the most commonly spoken in the u.s., why do bilingual speakers find switching languages so easy neuroscience has the answer.

A second factor exacerbating the threat to endangered languages is the density of roads in an area. While contact with other languages can help preserve indigenous ones, exposure to the wider world may not.

“We found that the more roads there are, connecting country to city, and villages to towns, the higher the risk of languages being endangered. It’s as if roads are helping dominant languages ‘steam roll’ over other smaller languages,” said Professor Lindell Bronham, co-author of the study.

Lost language diversity

The factors identified by the study could help explain why just a handful of languages dominate global communication.

Mandarin Chinese has the most native speakers, which is unsurprising given China’s huge population, but English is the world’s most widely used language with around 1.35 billion speakers. The study, published in Nature, Ecology and Evolution , shows the extent to which the world’s language diversity is under threat. It estimates the equivalent of one language is currently lost within every three-month period. But levels of language loss could actually triple in the next 40 years, with at least one language per month disappearing unless measures are taken. “When a language is lost or is ‘sleeping’ as we say for languages that are no longer spoken, we lose so much of our human cultural diversity,” said Professor Bromham.

“Many of the languages predicted to be lost this century still have fluent speakers, so there is still the chance to invest in supporting communities to revitalize indigenous languages and keep them strong for future generations.”

Can technology help save indigenous languages?

While past studies have blamed the digital realm for causing the demise of some indigenous dialects - by focusing attention on a few major languages at the expense of smaller ones - today’s tech-entwined world could hold a solution. There are Internet sites and apps aplenty to help new speakers learn languages like Spanish, English and Mandarin, but these now extend to specialist apps designed to teach endangered languages or help preserve them. Ma! Iwaidja, for example, is an app that enables those working with speakers of the Iwaidja indigenous Australian language to record words, phrases and translations. It also contains a dictionary and a word maker to help users tackle grammar and syntax.

Another initiative is the Rosetta Project , a global collaboration of language specialists and native speakers working to build an open-access digital library of human languages. The collection contains around 100,000 pages of documents and recordings for more than 2,500 languages microscopically etched on nickel disks for long-term storage. The project draws attention to the “drastic and accelerated loss of the world’s languages” and could help preserve many endangered and “sleeping” languages for future generations.

The UNESCO International Decade of Indigenous Languages (IDIL2022-2032) , which begins this year, also aims to engage the global community with the critical issue of language loss.

The 10-year initiative continues the work of the UN’s 2019 International Year of Indigenous Languages. As part of its Global Action Plan, IDIL2022-2032, it is creating a network of international stakeholders focused on protecting the rights of indigenous people to revitalize and preserve their languages.

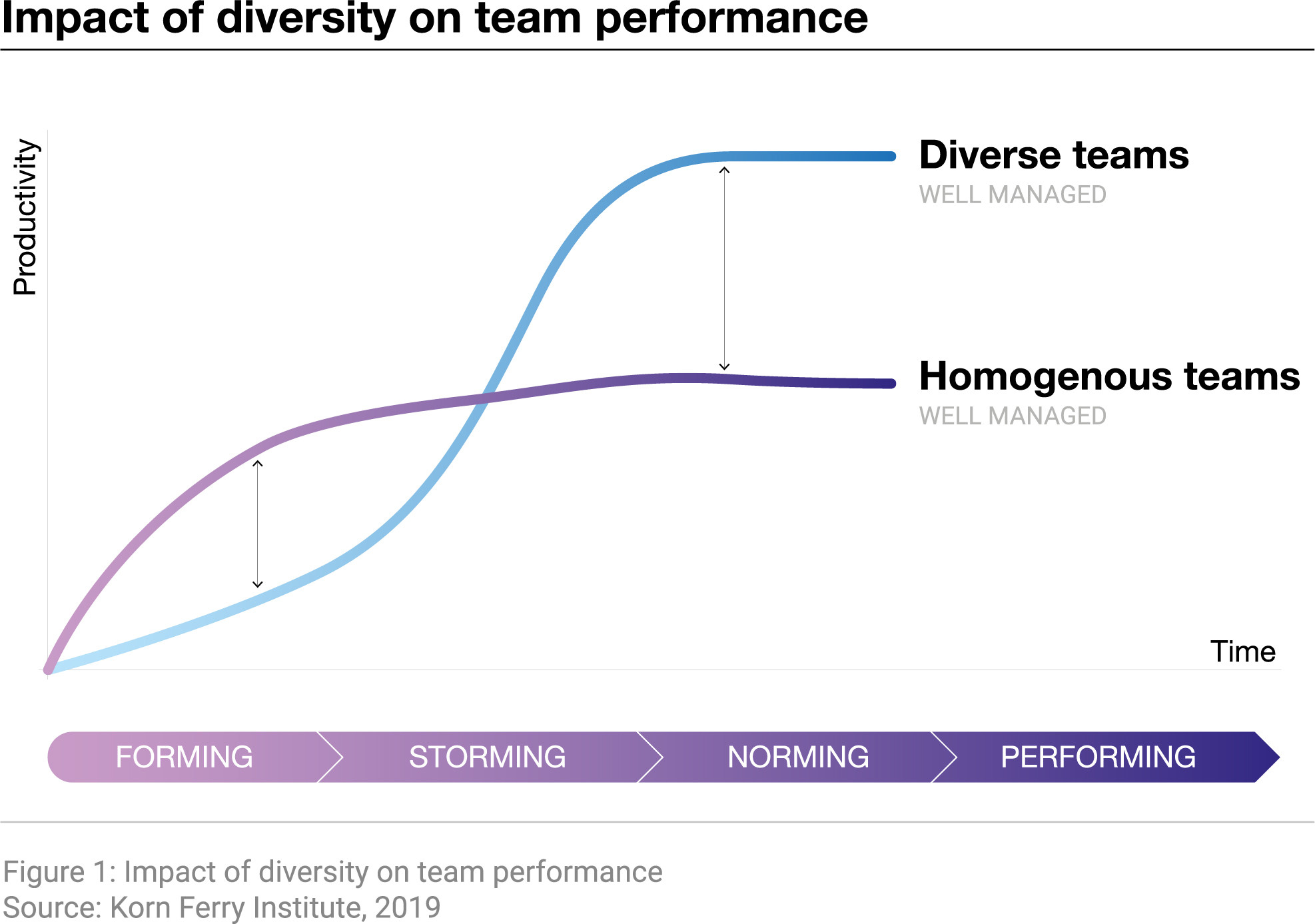

The COVID-19 pandemic and recent social and political unrest have created a profound sense of urgency for companies to actively work to tackle inequity.

The Forum's work on Diversity, Equality, Inclusion and Social Justice is driven by the New Economy and Society Platform, which is focused on building prosperous, inclusive and just economies and societies. In addition to its work on economic growth, revival and transformation, work, wages and job creation, and education, skills and learning, the Platform takes an integrated and holistic approach to diversity, equity, inclusion and social justice, and aims to tackle exclusion, bias and discrimination related to race, gender, ability, sexual orientation and all other forms of human diversity.

The Platform produces data, standards and insights, such as the Global Gender Gap Report and the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion 4.0 Toolkit , and drives or supports action initiatives, such as Partnering for Racial Justice in Business , The Valuable 500 – Closing the Disability Inclusion Gap , Hardwiring Gender Parity in the Future of Work , Closing the Gender Gap Country Accelerators , the Partnership for Global LGBTI Equality , the Community of Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officers and the Global Future Council on Equity and Social Justice .

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Related topics:.

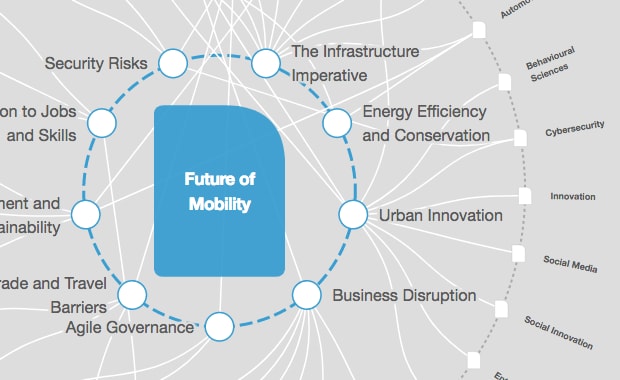

.chakra .wef-1v7zi92{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1v7zi92{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-ugz4zj{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);color:var(--chakra-colors-yellow);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-ugz4zj{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Mobility is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-19044xk{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);color:var(--chakra-colors-uplinkBlue);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-19044xk{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

The agenda .chakra .wef-dog8kz{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineheights-base);font-weight:var(--chakra-fontweights-normal);} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:flex;align-items:center;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Jobs and the Future of Work .chakra .wef-2sx2oi{display:inline-flex;vertical-align:middle;padding-inline-start:var(--chakra-space-1);padding-inline-end:var(--chakra-space-1);text-transform:uppercase;font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-smallest);border-radius:var(--chakra-radii-base);font-weight:var(--chakra-fontWeights-bold);background:none;box-shadow:var(--badge-shadow);align-items:center;line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-short);letter-spacing:1.25px;padding:var(--chakra-space-0);white-space:normal;color:var(--chakra-colors-greyLight);box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width: 37.5rem){.chakra .wef-2sx2oi{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-smaller);}}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-2sx2oi{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-base);}} See all

Convening with purpose: The roadmap to a sustainable workforce in advanced manufacturing

Stephanie Wright and Kerry Ebersole

October 29, 2024

4 ways workplaces can help bridge the gender care gap

How Japan is healing from its overwork crisis through innovation

Skills for the future: 4 ways to help workers transition to the digital economy

8 reasons why investing in employee health is good for people and business

How the sustainable growth of emerging markets hinges on the informal economy

Become a Supporting Member

For 15 years, Longreads has published and curated the best longform writing on the web—and we wouldn’t exist without supporters like you. Give today and ensure that quality journalism continues to flourish.

Thank you for your contribution!

The Best of the Web—in Your Inbox

Every day we scour the internet for the best longform writing, and every day we send you our editors' picks. Join 100,000 newsletter subscribers—and don't miss that story everyone is talking about.

- Daily Updates

- Weekly Top 5

Join Longreads today!

Register with Longreads for free and get access to our editors' picks collecting the best stories on the web, as well as our award-winning original writing.

Newsletters

Our privacy policy can be found here.

Thank you for registering!

An account was already registered with this email. Please check your inbox for an authentication link.

Longreads : The best longform stories on the web

Disappearing Language: A Reading List on Losing Your Native Tongue

Share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Mastodon (Opens in new window)

This story was funded by our members. Join Longreads and help us to support more writers.

By Pardeep Toor

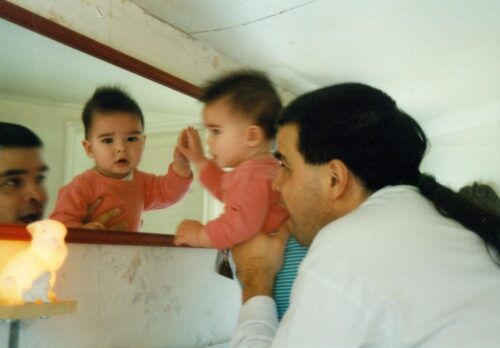

English was the first language my newborn heard after his birth in October 2021, probably something medical the midwife said, or congratulations from a nearby nurse. My wife and I were speechless, focusing only on our son’s blue skin, piercing screams, and block of black hair that overwhelmingly confirmed he was indeed ours.

As first-time parents, our son instantly became the exclusive lens through which we viewed our world. I should’ve gotten new windshield wipers to make sure we reached home safely. Next time, I will take my elevated bilirubin levels seriously. My wife swore to get the spot on her retina checked again. She couldn’t remember the last time we’d dusted underneath our bed. We’d prepared nine months for this shift, but it still shook us. Our lives were only necessary to sustain his life.

We couldn’t stay speechless for long. The nurses eventually checked on us less frequently. Poking and prodding clinicians dissipated, leaving us with the humming overhead tube lights and beeping in the hallway. It was our turn to talk to our son, but what would we say?

English wasn’t the first language for either of us. My wife is a native Spanish speaker and I exclusively spoke Punjabi for the first six years of my life. We both acquired English through our respective educations in Colombia and Canada. We promised to give our son both our languages, despite failing to acquire them from each other.

English is our essential language, a primary means of communication that allows us to thrive as a couple, while simultaneously pulling us away from our native languages and cultures. Each spoken syllable of English is a leap away from our rolling “Rs” in Punjabi and Spanish. I’m not demonizing English, rather recognizing the challenge of its dominance in our lives.

In the past four months, we’ve obsessed over speaking our respective languages to our son. It’s turned into a game: My wife will say something to him in Spanish, I’ll ask what she said, she tells me in English, and then I translate it into Punjabi and say it louder and faster back to our son as if his comprehension is a race we’re each trying to win. It’s partly in fun — but also stems from a sincere apprehension. We’re trying to pass down our languages while preserving them in our own lives.

Regardless of our efforts, English will inevitably become the common language that my wife and I share with our son. It’s the only way we can talk to him without isolating each other. In doing so I’m afraid I’ll continue to lose my native Punjabi and our son will forever lose something he could have had.

This struggle isn’t exclusive to our family. The loss of language has been extensively explored in the following essays.

The Pain of Losing Your First Language (Kristin Wong, Catapult , December 2021)

This essay outlines the suffering Wong endured since foregoing her native language as a child for the sake of assimilating into America. Wong does a phenomenal job of incorporating linguistic research in her analysis, giving academic weight to her regrets. The balance of personal narrative and analysis of English language adoption and native attrition flows through the essay as studies confirm Wong’s feelings, yet don’t free her from longing for her first language. “I wonder what Cantonese words my brain pushed out when I started speaking mostly English at age six. And is attrition limited to words? What else did I lose to assimilate?”

During her pregnancy, Wong commits to re-learning her native Cantonese so she can pass it on to her child. However, despite her efforts, she feels the impossibility of her task.

Like learning how to spell only, the more I look at Jyutping, the more the words start to make sense. But part of me knows better. I’ll never speak Cantonese the same way I would have if I’d never stopped speaking it to begin with. Like a phantom limb, the memory of my first language stays with me even with it gone, but that’s all it is: a memory. It occurs to me that trying to relearn this language is the embodiment of my bicultural identity. The American in me is determined to reclaim the Chinese part of myself.

Why Do I Write in My Colonizers’ Language? (Anandi Mishra, Electric Literature, March 2021)

Part of the struggle with English has always been its foreignness. The language either forcefully invaded foreign lands or immigrants willingly chose to move west. Mishra addresses the colonial legacy of English and how that makes her feel “queasy,” while also recognizing the language’s modern dominance in India.

For my family, friends, relatives, and teachers, English was seen as a language of access. It could land you better jobs, remove limitations, and open up avenues. English speakers were high achievers, often conflated with the colonizers who ruled over us for about 200 years. It was ironic that the language of our colonizers was seen as aspirational, something that could lift us out of the discomfort that our parents’ mid-level jobs put us through. In reading all the subjects at school in English, we were made to understand that English was the language of possibilities.

Mishra reluctantly accepts the realities of the English language in India and her own life. But acceptance can also be an acknowledgment of adaptation — it’s not one or the other, English or Hindi, but hybridity that can hopefully be respectful to native languages and English’s injection into them.

Translation as an Arithmetic of Loss (Ingrid Rojas Contreras, The Paris Review , June 2019)

Rojas Contreras opens this essay by acknowledging, “When you live between languages, the conversion of meaning is an arithmetic in loss.” Thoughts generated in one language come out awkwardly in English, or sometimes not at all. This ultimately leads to a feeling of “being understood sufficiently, rather than fully.”

This loss between languages catalyzed Rojas Contreras to write her debut novel, Fruit of the Drunken Tree , in English, even though she thought of it in Spanish. She constructed the sentences in Spanish in her mind but then immediately translated them into English on the page.

Why didn’t you write the novel in Spanish? This is a question I get all the time. Language is one of the things you sacrifice when you migrate. I wanted to be true to the toll of that sacrifice by making visible what exactly was being lost.

My wife loves Rojas Contreras’s writing. She sees both her own Spanish and English in the syntax. It’s how she sees the world, in a constant state of translation from one language to another. By seeing Rojas Contreras’s translated language on the page, my wife sees her worldview being expressed as a reality and feels understood as an immigrant in the United States.

Teaching Yourself Italian (Jhumpa Lahiri, The New Yorker, November 2015)

Lahiri, an internationally renowned fiction writer, started writing from scratch in Italian to escape the personal weight of the English language.

Why am I fleeing? What is pursuing me? Who wants to restrain me? The most obvious answer is the English language. But I think it’s not so much English in itself as everything the language has symbolized for me. For practically my whole life, English has represented a consuming struggle, a wrenching conflict, a continuous sense of failure that is the source of almost all my anxiety. It has represented a culture that had to be mastered, interpreted. I was afraid that it meant a break between me and my parents. English denotes a heavy, burdensome aspect of my past. I’m tired of it.

Lahiri opted not to re-engage with her native Bengali, which she spoke with an accent and admitted to not knowing how to read or write. She started anew with Italian, placing herself in a linguistic exile, far removed from her familial past in Bengali and professional life in English. Native languages, and the projected cultural expectations that come with them, can be as burdensome as chasing a distorted and romanticized memory or history. Lahiri’s fresh start in Italian vanquishes the obligation of chasing ghosts from her past and allows her to forge a novel identity in a new language.

Ghosts (Vauhini Vara, The Believer , August 2021)

What happens when all languages fail? When you’re unable to express yourself no matter how many languages you can speak? That’s where the future comes in. Vara, unable to express grief after losing her sister, turned to an algorithm to complete her thoughts.

I felt acutely that there was something illicit about what I was doing. When I carried my computer to bed, my husband muttered noises of disapproval. We both make our livings as writers, and technological capitalism has been exerting a slow suffocation on our craft. A machine capable of doing what we do, at a fraction of the cost, feels like a threat. Yet I found myself irresistibly attracted to GPT-3—to the way it offered, without judgment, to deliver words to a writer who has found herself at a loss for them.

What followed was an experiment in human-computer interactions. Vara feeds words into Generative Pre-Trained Transformer 3 (GPT-3) and the remaining text is predicted, with the details Vara provides about her sister determining how the narrative ends — technology offering a borderless universal language with infinite memory.

The nine stories completed by artificial intelligence in this piece are something new, void of human attachment. Culture in an algorithm. Is this how people will one day express themselves and understand their upbringing? Then what remains of the cultural nuances embedded in our native languages? Are one or two or three languages enough for our son? Are they the right languages? What if they all fail him? The fear of losing our language and culture to algorithms and English inspires us to transmit what we have left amidst our loss.

Pardeep Toor ‘s writing has appeared in the Best Debut Short Stories 2021: The PEN America Dau Prize, Catapult, Electric Literature, Southern Humanities Review, Midwest Review, and Great River Review.

Editor: Carolyn Wells

Support Longreads

By clicking submit, you agree to share your email address with the site owner and Mailchimp to receive marketing, updates, and other emails from the site owner. Use the unsubscribe link in those emails to opt out at any time.

We've recently sent you an authentication link. Please, check your inbox!

Sign in with a password below, or sign in using your email .

Get a code sent to your email to sign in, or sign in using a password .

Enter the code you received via email to sign in, or sign in using a password .

Subscribe to our newsletters:

Sign in with your email

Lost your password?

Try a different email

Send another code

Sign in with a password

Are People Projecting Racist Stereotypes Onto Squirrels?

Tackling the Impossibility—and Necessity—of Counting the World’s Languages

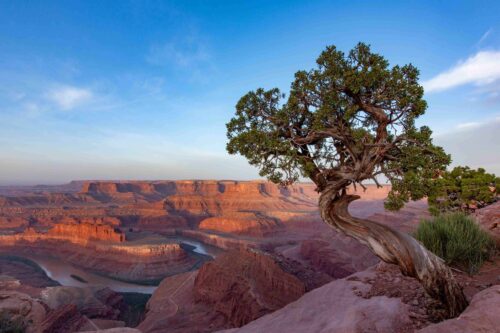

Gathering Firewood—and Redefining Land Stewardship—at Bears Ears

Harvest Song

How Water Insecurity Impacts Women’s Health

Unraveling a “Ghost” Neanderthal Lineage

Playing Rock, Paper, Scissors Across the Red-Blue Divide

Revisiting the Spiritual Violence of BS Jobs

The Distant Origins of a Stonehenge Stone

Do You Want to Write for SAPIENS?

People Are Not Peas—Why Genetics Education Needs an Overhaul

Archived Haints

Gaza’s Deaf Community in the Face of Genocide

Protecting Ancestral Waters Through Collaborative Stewardship

Digging Into an Ancient Apocalypse Controversy From a Hopi Perspective

The Land of Dreams

Finding Our Way Forward—by Remembering

Speaking Truth to Israel Requires More Than Academic Freedom

Payangko, or Echidna ( Zaglossus attenboroughi )

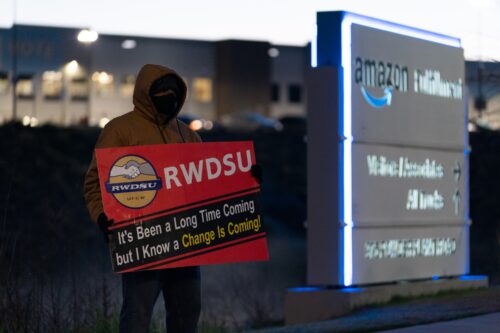

Inside Amazon’s Union-Busting Tactics

Fighting for Reproductive Rights in Retirement

Can Ancient DNA Support Indigenous Histories?

Can Embracing Copies Help With Museum Restitution Cases?

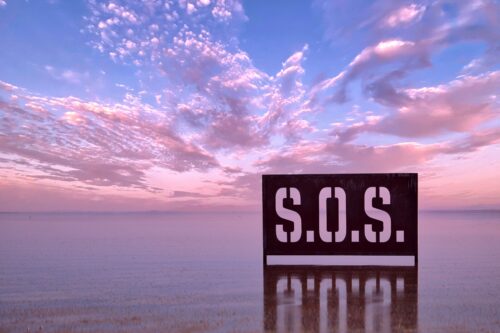

Can Art Save the “Post-Apocalyptic” Salton Sea?

How Allocating Work Aided Our Evolutionary Success

Bringing Back the World’s Most Endangered Cat

The Shortcomings of Height in Politics

Griko’s Poetic Whisper

When a Message App Became Evidence of Terrorism

Cuando una aplicación de mensajería se convirtió en prueba de terrorismo

The Rise of Aunties in Pakistani Politics

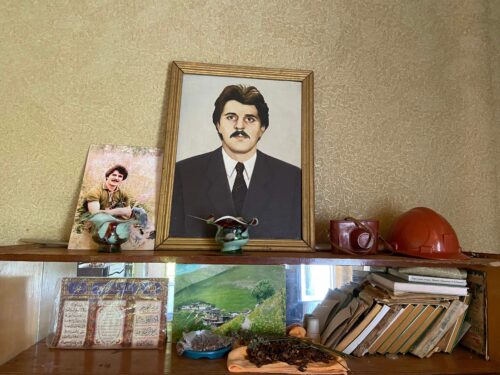

For Families of Missing Loved Ones, Forensic Investigations Don’t Always Bring Closure

Why Are Languages Worth Preserving?

I met the last speaker of Naati on an empty stretch of beach on Malekula, an island in the South Pacific nation of Vanuatu. I had been hiking for hours along narrow paths through the hot, dense forest, wading across the occasional waist-high stream with my pack of recording equipment hoisted overhead. As I dropped my pack on the sand, a figure descended from the nearby cliffs and crossed the beach toward me.

We exchanged greetings in the local creole, and the conversation quickly turned to the topic of my unlikely appearance on these shores. I told the man, Ariep, that I was in the country to study one of its many Indigenous languages. When he learned I was a linguist, he excitedly shared that he speaks Naati.

Plunging several sticks into the sand and using them as reference points, Ariep explained the relationship between Naati and the other languages of the area. With a mix of pride and sorrow, he revealed that he is the last fluent speaker of Naati. Although a few of his family members have some knowledge of the language and make an effort to use it together, he fears that with his death, Naati will soon disappear.

Naati’s predicament is not unique. Of the roughly 7,000 languages spoken on the planet today, 50 to 90 percent are considered vulnerable to extinction by the end of the century.

Language is the cultural glue that binds communities together.

The crisis has received increasing public attention over the past decade, punctuated by lines such as “one language dies every two weeks” and illustrated by poignant tales of the death of a last speaker. In this UNESCO International Year of Indigenous Languages , as alarm bells sound and preservation efforts are celebrated, we should pause to ask: Why does it matter?

Should Naati’s fate concern the world? Ariep does not need Naati to communicate. Like many speakers of endangered languages, he is fluent in an impressive number of languages, including several native to his island, as well as the national language.

If we are heading toward a future in which we all speak one of a few large languages, isn’t that a good thing? Couldn’t it be a way to facilitate communication and level the playing field across nations? Is the desire to “save” these small languages purely sentimental—a romantic notion fostered by scholars in ivory towers of isolated peoples untouched by the exhausting rush toward globalization?

I argue “no.” As a linguist who has worked with endangered language communities in Canada and the Asia-Pacific, I know that language loss is a critical and urgent problem—not only for the speakers who lose their languages, but for everyone. Languages are a vital source of culture and identity for individual communities, and for the global community, languages are an invaluable source of information about human cognition. A linguistically diverse world benefits us all.

Consider what has happened to people whose language has been forcibly taken from them, supplanted by one of the larger, ostensibly more useful languages. This scenario has played out countless times across centuries at the hands of colonial powers or as a tool of national governments to suppress minority groups. It occurs around the world today in classrooms where children are punished or humiliated for using languages and dialects that deviate from an accepted standard.

The response of these communities has not been to celebrate the subsequent generations who speak English, Spanish, Swahili, or whatever the language of power might be. Rather, they decry this cultural genocide and, where possible, fight back against the theft of their linguistic heritage.

In Canada during the 19th and 20th centuries, the national government oppressed Indigenous people in part by removing children from their families and placing them in residential schools . In these spaces, children suffered a range of physical and mental abuses, including punishment for speaking their languages . These injustices severely disrupted the transmission of dozens of Indigenous languages, the majority of which are now endangered.

Today, despite a scarcity of resources to address numerous challenges after decades of persecution, Indigenous Canadian communities are making huge investments in reclaiming their languages. From the “language nest” in Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory in Ontario, where children are exposed only to Mohawk throughout the day, to the Nehiyawak language and culture camps in Saskatchewan, where families learn and share their Cree heritage, Indigenous language education across Canada is flourishing.

It would seem easier, cheaper, and infinitely more practical just to accept English (a language that is no less highly desirable internationally) and shift the resources elsewhere. The fact that people struggle to reclaim their languages despite the obstacles says something crucial about the value of language and the tragedy of loss.

Language is the cultural glue that binds communities together. Language loss is a loss of community heritage—from histories and ancestral lineages known only through oral storytelling, to knowledge of plants and practices codified through words unwritten and untranslated.

Lulamogi speakers in Uganda, for example, worry that as people forget the dozens of terms that describe methods of trapping and eating white ants—such as okukunia , okutegerera , and okubuutira —they will forget this important cultural practice. Also at risk are the phrases and associated customs for welcoming the agricultural seasons and washing the bodies of the dead.

In the words of Lulamogi language advocate Nabeeta Erusaniah: “It is like when a wall of a hut collapses, the ceiling does not remain standing. What keeps the social practices and a ritual standing is the language. Kill the language, and the shelter collapses too.”

Language loss is also a loss of community identity, collective purpose, and self-determination. While harder to quantify, such losses have real, detrimental effects on health and quality of life. Conversely, the ability of community members to speak their Indigenous language together enhances well-being.

In British Columbia, youth suicide rates are more than six times lower in Indigenous communities where at least 50 percent of the population speaks the native language. In Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities of Australia, young people who speak an Indigenous language have lower rates of binge drinking and illegal drug use compared to nonspeakers, as well as a decreased chance of becoming victims of violence.

The disappearance of a language may seem like an unfortunate loss only to the people involved. However, the impact for all of us is real and substantial.

This impact goes beyond the losses of particular bits of information, like Indigenous names for medicinal plants yet to be classified by scientists outside a community, or concepts and worldviews reflected in the words and structures of one language that do not have parallels in another. Understanding language is vital to understanding human cognition. Each language is a piece of the puzzle that we need in order to determine how language works in the mind. With each missing piece, we are further from seeing the full picture.

Analyzing language patterns has real implications for our lives.

Languages may appear to differ wildly from one another, but they are all variations on a theme. Like a field of flowers, the individual plants may vary in height and color, but they all have stems and petals.

Your language may have “tall trees” or “trees tall.” It may ask, “Where is the dog?” or “The dog is where?” It may thank you in one syllable or in many. Regardless, whether your language is spoken or signed, it draws on a limited set of forms and structures, and it uses them in consistent and predictable ways.

The remarkable similarities across languages suggest that there is some cognitive capacity that underlies all human language, directing how language develops and setting the boundaries for what is possible. The goal of contemporary linguistics is to describe and model this system—in essence, to figure out how language works.

For example, languages contrast greatly in their number of consonants, from the six in the Papuan language Rotokas to the 122 in the Southern African language ǃXóõ. There are enough commonalities among sound systems, however, that if linguists know your language has 20 consonants, we can make a fairly good guess as to what many are likely to be, and we can be almost certain of others that would not occur. In terms of sentence structure, all languages use the three basic elements subject, object, and verb. Although these can be ordered in different ways, about 80 percent of known languages put the subject first, while only about 1 percent put the object first.

Analyzing these patterns is far from an esoteric academic exercise; it has real implications for our lives. The more we understand about how language functions, the better equipped we are to improve our therapies for communication disorders and our methods for language teaching.

This knowledge contributes to technological innovation as well. Research on sound patterns is used in creating speech synthesis software, while models of grammatical structure aid in developing linguistic components for artificial intelligence.

Understanding language in turn gives us a window into cognition. Observations about the strikingly similar ways that children acquire language, across languages and cultures, provide insight into how the brain develops. Psycholinguistic experiments involving language production, comprehension, and recall tasks reveal clues to how the mind organizes information.

Early models of grammar were based primarily on a few large, mostly European, languages that Western scholars knew or could easily access. Imagine the deficiencies if the research stopped there. It would be like basing an understanding of plants on a neighborhood vegetable garden or of animals on a trip to a petting zoo.

Recent reports on gender bias in medical testing have revealed that therapies tested on men do not necessarily work for women. Studies of racial bias in the tech industry have shown that applications such as facial recognition, which were trained on images of white people, do not necessarily work for people of color. When it comes to language, what if our models are proven incorrect by a previously undocumented cluster of languages in the Amazon? A theory of human language must account for the language of all humans.

However, taking into account all languages, or even a representative sample, is a huge challenge. Thousands of languages are undocumented or only very poorly described, and no one—neither linguists nor speakers—understand how they work.

Documenting a language thoroughly is a major undertaking involving years of collaboration between the members of a speech community and linguists (who may or may not be speakers themselves). Given the rapid rate of language loss in the world today, many languages are in danger of disappearing before they have been documented, taking with them irreplaceable information about human cognition.

The very limited documentation we have of Naati reveals that the language has a sound called a “bilabial trill.” These trills were once considered impossible speech sounds, but now linguists know that they are common in the languages of Malekula.

As I watched Ariep turn back toward the cliffs that day on the beach, taking with him a wealth of linguistic and cultural knowledge, I wondered, Does Naati contain other features that could challenge our understanding of language?

What can the many undocumented languages teach us about language structure and cognition, about the richness of our cultures and traditions, about our very humanity? For the sake of the speakers of endangered languages, for the sake of us all, we must preserve the world’s languages as we search for answers and work to ensure linguistic diversity for generations to come.

Anastasia Riehl is a linguist with a Ph.D. from Cornell University. She is currently the director of the Strathy Language Unit at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Her work with endangered languages has taken her to Indonesia and Vanuatu, as well as to the city of Toronto, where she directs a project to document the endangered heritage languages of immigrant communities.

Stay connected

Facebook , Instagram , LinkedIn , Threads , Twitter , Mastodon , Flipboard

Y ou may republish this article, either online and/or in print, under the Creative Commons CC BY-ND 4.0 license. We ask that you follow these simple guidelines to comply with the requirements of the license.

I n short, you may not make edits beyond minor stylistic changes, and you must credit the author and note that the article was originally published on SAPIENS.

A ccompanying photos are not included in any republishing agreement; requests to republish photos must be made directly to the copyright holder.

We’re glad you enjoyed the article! Want to republish it?

This article is currently copyrighted to SAPIENS and the author. But, we love to spread anthropology around the internet and beyond. Please send your republication request via email to editor•sapiens.org.

Accompanying photos are not included in any republishing agreement; requests to republish photos must be made directly to the copyright holder.

- Share full article

Can You Lose Your Native Tongue?

After moving abroad, I found my English slowly eroding. It turns out our first languages aren’t as embedded as we think.

Credit... Artwork by PABLO DELCÁN

Supported by

By Madeleine Schwartz

Madeleine Schwartz is a writer and editor who grew up speaking English and French. She has been living in Paris since 2020.

- May 14, 2024

It happened the first time over dinner. I was saying something to my husband, who grew up in Paris where we live, and suddenly couldn’t get the word out. The culprit was the “r.” For the previous few months, I had been trying to perfect the French “r.” My failure to do so was the last marker of my Americanness, and I could only do it if I concentrated, moving the sound backward in my mouth and exhaling at the same time. Now I was saying something in English — “reheat” or “rehash” — and the “r” was refusing to come forward. The word felt like a piece of dough stuck in my throat.

Listen to this article, read by Soneela Nankani

Other changes began to push into my speech. I realized that when my husband spoke to me in English, I would answer him in French. My mother called, and I heard myself speaking with a French accent. Drafts of my articles were returned with an unusual number of comments from editors. Then I told a friend about a spill at the grocery store, which — the words “conveyor belt” vanishing midsentence — took place on a “supermarket treadmill.” Even back home in New York, I found my mouth puckered into the fish lips that allow for the particularly French sounds of “u,” rather than broadened into the long “ay” sounds that punctuate English.

My mother is American, and my father is French; they split up when I was about 3 months old. I grew up speaking one language exclusively with one half of my family in New York and the other language with the other in France. It’s a standard of academic literature on bilingual people that different languages bring out different aspects of the self. But these were not two different personalities but two separate lives. In one version, I was living with my mom on the Upper West Side and walking up Columbus Avenue to get to school. In the other, I was foraging for mushrooms in Alsatian forests or writing plays with my cousins and later three half-siblings, who at the time didn’t understand a word of English. The experience of either language was entirely distinct, as if I had been given two scripts with mirroring supportive casts. In each a parent, grandparents, aunts and uncles; in each, a language, a home, a Madeleine.

I moved to Paris in October 2020, on the heels of my 30th birthday. This was both a rational decision and something of a Covid-spurred dare. I had been working as a journalist and editor for several years, specializing in European politics, and had reported across Germany and Spain in those languages. I had never professionally used French, in which I was technically fluent. It seemed like a good idea to try.

When I arrived in France, however, I realized my fluency had its limitations: I hadn’t spoken French with adults who didn’t share my DNA. The cultural historian Thomas Laqueur, who grew up speaking German at home in West Virginia, had a similar experience, as the linguist Julie Sedivy notes in “Memory Speaks,” her book about language loss and relearning her childhood Czech. Sedivy cites an essay of Laqueur’s in which he describes the first time he learned that German was not, in fact, a secret family language. He and his brother had been arguing over a Popsicle in front of the grocery store near his house:

A lady came up to us and said, in German, that she would give us a nickel so that we could each have a treat of our own. I don’t remember buying a second Popsicle, but I do remember being very excited at finding someone else of our linguistic species. I rushed home with the big news.

My own introduction to speaking French as an adult was less joyous. After reaching out to sources for a different article for this magazine with little success, I showed the unanswered emails to a friend. She gently informed me that I had been yelling at everyone I hoped to interview.

Compared with English, French is slower, more formal, less direct. The language requires a kind of politeness that, translated literally, sounds subservient, even passive-aggressive. I started collecting the stock phrases that I needed to indicate polite interaction. “I would entreat you, dear Madam ...” “Please accept, dear sir, the assurances of my highest esteem.” It had always seemed that French made my face more drawn and serious, as if all my energy were concentrated into the precision of certain vowels. English forced my lips to widen into a smile.

But going back to English wasn’t so easy, either. I worried about the French I learned somehow infecting my English. I edit a magazine, The Dial, which I founded in part to bring more local journalists and writers to an English-speaking audience. But as I worked on texts by Ukrainians or Argentines or Turks, smoothing over syntax and unusual idioms into more fluid English prose, I began to doubt that I even knew what the right English was.

Back in New York on a trip, I thanked the cashier at Duane Reade by calling him “dear sir.” My thoughts themselves seemed twisted in a series of interlocking clauses, as though I was afraid that being direct might make me seem rude. It wasn’t just that my French was getting better: My English was getting worse.

For a long time, a central question in linguistics was how people learn language. But in the past few decades, a new field of study called “language attrition” has emerged. It concerns not learning but forgetting: What causes language to be lost?

People who move to new countries often find themselves forgetting words in their first language, using odd turns of phrase or speaking with a newly foreign accent. This impermanence has led linguists to reconsider much of what was once assumed about language learning. Rather than seeing the process of becoming multilingual as cumulative, with each language complementing the next, some linguists see languages as siblings vying for attention. Add a new one to the mix, and competition emerges. “There is no age at which a language, even a native tongue, is so firmly cemented into the brain that it can’t be dislodged or altered by a new one,” Sedivy writes. “Like a household that welcomes a new child, a single mind can’t admit a new language without some impact on other languages already residing there.”

As my time in France hit the year mark and then the two-year mark, I began to worry about how much French was changing my English — that I might even be losing some basic ability to use the language I considered closest to my core. It wasn’t an idle concern. A few years earlier, when living in Berlin, I found the English of decades-long expats mannered and strange; they spoke more slowly and peppered in bits of German that sounded forced and odd. As an editor, I could see it in translators too: The more time people spent in their new language, the more their English prose took on a kind of Germanic overtone. Would the same thing happen to me?

Even languages that seem firmly rooted in the mind can be subject to attrition. “When you have two languages that live in your brain,” says Monika S. Schmid, a leader in the field of language attrition at the University of York, “every time you say something, every time you take a word, every time you put together a sentence, you have to make a choice. Sometimes one language wins out. And sometimes the other wins.” People who are bilingual, she says, “tend to get very, very good at managing these kinds of things and using the language that they want and not having too much interference between the two.” But even so, there’s often a toll: the accent, the grammar or a word that doesn’t sound quite right.

What determines whether a language sticks or not? Age, Schmid says, is an important factor. “If you look at a child that is 8, 9 or 10 years old, and see what that child could do with the language and how much they know — they’re basically fully fledged native speakers.” But just as they are good language learners, children are good language forgetters. Linguists generally agree that a language acquired in early childhood tends to have greater emotional resonance for its speaker. But a child who stops speaking a language before age 12 can completely lose it. For those who stop speaking a language in childhood, that language can erode — so much so that when they try to relearn it, they seem to have few, if any, advantages, Schmid says, compared with people learning that language from scratch. Even a language with very primal, deep connections can fade into the recesses of memory.

In her book, Sedivy cites a study conducted in France that tested a group of adults who were adopted from Korea between the ages of 3 and 8 . Taken into French homes, they quickly learned French and forgot their first language. The researchers compared these adults with a group of monolingual French speakers. The participants born in Korea could not identify Korean sentences significantly better than the French control group. Intimate moments of childhood can be lost, along with the language in which they took place.

Researchers have stressed that a first language used through later years can be remarkably resilient and often comes back when speakers return home. But even adults who move to a new country can find themselves losing fluency in their first language. Merel Keijzer, a linguist at the University of Groningen who studies bilingualism, surveyed a group of Dutch speakers who emigrated as adults to Australia. A classic theory of linguistic development, she told me, argues that new language skills are superimposed on older ones like layers of an onion. She thus expected that she would find a simple language reversion: The layers that were acquired later would be most likely to go first.

The reality was more complicated. In a paper Keijzer wrote with Schmid, she found that the Dutch speakers in Australia did not regress in the way that she predicted. “You saw more Dutch coming into their English, but you also saw more English coming into their Dutch,” she says. The pattern wasn’t simple reversion so much as commingling. They “tended to just be less able to separate their languages.” As they aged, the immigrants didn’t go back to their original language; they just had difficulty keeping the two vocabularies apart.

In “Alfabet/Alphabet: A Memoir of a First Language,” the poet Sadiqa de Meijer, who was born in Amsterdam, discusses her own experiences speaking Dutch in Canada. She worries that her language has become “amusingly formal” now that she doesn’t speak it regularly. A friend tells her that she now sounds “like a book.” Unless she is in the Netherlands, she writes: “Dutch is primarily a reading language to me now. The skill of casual exchanges is in gradual atrophy.” Her young daughter does not want to speak Dutch. “Stop Dutching me!” she says. For De Meijer, “people who speak a language they learned after early childhood live in chronic abstraction.”

This state of abstraction was one that I feared. On some level, the worry felt trivial: In a world where languages are constantly being lost to English, who would complain about a lack of contact with the language responsible for devouring so many others? The Europeans that I interviewed for work deplored the imperial nature of English; the only way to have their ideas heard was to express them in a language imposed by globalization. But what I missed was not the universal English of academics nor the language of peppy LinkedIn posts but the particular sounds that I grew up with: the near-rudeness of the English spoken in New York and its rushed cadence, the way that the bottoms of words sometimes were swallowed and cut off, as if everyone already knew what was being suggested and didn’t need to actually finish the thought. I missed the variegated vocabulary of New York, where English felt like an international, rather than a globalized language, enriched with the particular words of decades of immigrants. I began to listen to “The Brian Lehrer Show” on WNYC, a public-radio station in New York, with strange fervor, finding myself excited whenever someone called in from Staten Island.

The idea that my facility with English might be weakening brought up complicated feelings, some more flattering than others. When a journalism student wrote to ask if I would be a subject in his dissertation about “the experiences of nonnative English-speaking journalists” in media, I took the email as a personal slight. Were others noticing how much I struggled to find the right word?

A change in language use, whether deliberate or unconscious, often affects our sense of self. Language is inextricably tied up with our emotions; it’s how we express ourselves — our pain, our love, our fear. And that means, as Schmid, the language-attrition expert at the University of York, has pointed out, that the loss of a language can be tied up with emotion too. In her dissertation, Schmid looked at German-speaking Jews who emigrated to England and the United States shortly before World War II and their relationship with their first language. She sent questionnaires asking them how difficult it was for them to speak German now and how they used the language — “in writing in a diary, for example, or while dreaming.”

One woman wrote: “I was physically unable to speak German. ... When I visited Germany for 3 or 4 days in 1949 — I found myself unable to utter one word of German although the frontier guard was a dear old man. I had to speak French in order to answer his questions.”

Her husband concurred: “My wife in her reply to you will have told you that she could and did not want to speak German because they killed her parents. So we never spoke German to each other, not even intimately.”

Another wrote: “I feel that my family did a lot for Germany and for Düsseldorf, and therefore I feel that Germany betrayed me. America is my country, and English is my language.”

Schmid divided the émigrés into three groups, tying each of them to a point in Germany’s history. The first group left before September 1935, that is, before the Nuremberg race laws. The second group left between the enactment of those laws and Kristallnacht, in November 1938. The last group comprised those who left between Kristallnacht and August 1939, just before Germany invaded Poland.

What Schmid found was that of all the possible factors that might affect language attrition, the one that had a clear impact was how much of the Nazi regime they experienced. Emigration date, she wrote, outweighed every other factor; those who left last were the ones who were the least likely to be perceived as “native” speakers by other Germans, and they often had a weaker relationship to that language:

It appears that what is at the heart of language attrition is not so much the opportunity to use the language, nor the age at the time of emigration. What matters is the speaker’s identity and self-perception. ... Someone who wants to belong to a speech community and wants to be recognized as a member is capable of behaving accordingly over an extremely long stretch of time. On the other hand, someone who rejects that language community — or has been rejected and persecuted by it — may adapt his or her linguistic behavior so as not to appear to be a member any longer.

In other words, the closeness we have with a language is not just a product of our ability to use it but of other emotional valences as well. If language is a form of identity, it is one that may be changed by circumstance or even by force of will.

Stories of language loss often mask other, larger losses. Lily Wong Fillmore, a linguist who formerly taught at the University of California, Berkeley, once wrote about a family who emigrated to California several years after leaving China’s Canton province in 1989. One child, Kai-fong, was 5 when he arrived in the United States. At this point in his life, he could speak and understand only Cantonese. While his younger sister learned English almost immediately and made friends easily, Kai-fong, who was shy, did not have the same experience in school. His classmates called him “Chi, chi, chia pet” because his hair stuck out. Boys mocked the polyester pants his grandmother sewed for him. Pretty soon, he and his classmates were throwing rocks at one another.

Once Kai-fong started learning English, he stopped speaking Cantonese, even to members of his own family. As Wong Fillmore writes: “When Grandmother spoke to him, he either ignored her or would mutter a response in English that she did not understand. ... The more the adults scolded, the more sullen and angry Kai-fong became.” By 10, he was known as Ken and no longer understood Cantonese well. The family began to split along linguistic lines. Two children born in the United States never learned Cantonese at all. It is a story, Wong Fillmore writes, “that many immigrant families have experienced firsthand.”

The recognition in linguistics of the ease with which mastery of a language can erode comes as certain fundamentals of the field are being re-examined — in particular, the idea that a single, so-called native language shapes your innermost self. That notion is inextricable from 19th-century nationalism, as Jean-Marc Dewaele, a professor at the University of London, has argued. In a paper written with the linguists Thomas H. Bak and Lourdes Ortega, Dewaele notes that many cultures link the first words you speak to motherhood: In French, your native language is a langue maternelle, in Spanish, lengua materna, in German, Muttersprache. Turkish, which calls your first language ana dili, follows the same practice, as do most of the languages of India. Polish is unusual in linking language to a paternal line. The term for native language is język ojczysty, which is related to ojciec, the Polish word for father.

Regarding a first language as having special value is itself the product of a worldview that places national belonging at the heart of individual life. The phrase “native speaker” was first used by the politician and philologist George Perkins Marsh, who spoke of the importance of “home-born English.” It came with more than a light prejudicial overtone. Among Marsh’s recommendations was the need for “special precautions” to protect English from “becoming debased and vulgarized ... by association with depraved beings and unworthy themes.”

The idea of a single, native language took hold in linguistics in the mid-20th century, a uniquely monolingual time in human history. American culture, with its emphasis on assimilation, was especially hostile to the notion that a single person might inhabit multiple languages. Parents were discouraged from teaching their children languages other than English, even if they expressed themselves best in that other language. The simultaneous acquisition of multiple tongues was thought to cause delays in language development and learning. As Aneta Pavlenko, a linguist at Drexel University and the University of York, has noted, families who spoke more than one language were looked down on by politicians and ignored by linguists through the 1970s. “Early bilinguals,” those who learned two languages in childhood, “were excluded from research as ‘unusual’ or ‘messy’ subjects,” she writes. By contrast, late bilinguals, those who learned a second language in school or adulthood, were treated as “representative speakers of their first language.” The fact that they spoke a second language was disregarded. This focus on the importance of a single language may have obscured the historical record, giving the impression that humans are more monolingual and more rigid in their speech than they are.

Pavlenko has sought to show that far from being the historical standard, speaking just one language may be the exception. Her most recent book, a collection of essays by different scholars, takes on the historical “amnesia” that researchers have about the prevalence of multilingualism across the globe. The book looks at examples where multiple languages were the norm: medieval Sicily, where the administrative state processed paperwork in Latin, Greek and Arabic, or the early Pennsylvania court system, where in the 18th and 19th centuries, it was not unusual to hold hearings in German. Even today, Pavlenko sees a split: American academics working in English, often their only language, regard it as the standard for research. Europeans, obliged to work in English as a second language, are more likely to consider that fluency in only one language may be far rarer than conflict among multiple tongues.

According to Dewaele and his colleagues, “the notion of a single native language, determined entirely by the earliest experiences, is also not supported by neurology and neuroscience.” While there are many stories about patients who find themselves speaking their first language after a stroke or dementia, it’s also common for the recovered patients to use the language they spoke right before the accident occurred.

All of this has led some linguists to push against the idea of the “native” speaker, which, as Dewaele says, “has a dark side.” It can be restrictive, stigmatizing accents seen as impure, or making people feel unwelcome in a new home. Speakers who have studied a language, Dewaele says, often know its grammar better than those who picked it up with their family. He himself prefers the term “first-language user” — a slightly clunky solution that definitively decouples the language you speak from the person you are.

Around the time I realized that I had most likely become the No. 1 WNYC listener outside the tristate area, I started to seek out writers who purposefully looked away from their “native” language. Despite the once commonly held belief that a writer could produce original works only in a “mother tongue,” wonderful books have been written in acquired, rather than maternal, languages. Vladimir Nabokov began to write in English shortly before he moved to the United States. French was a vehicle for Samuel Beckett to push his most innovative ideas. “It’s only in Italian that I feel I’m at the center of myself,” Jhumpa Lahiri, who started writing in Italian in her 40s, said in a recent Paris Review interview. “It’s only when I’m writing in Italian that I manage to turn off all those other, judgmental voices, except perhaps my own.”

Could I begin to think about different languages not as two personas I had to choose between but as different moods that might shift depending on circumstance? Aspects of French that I used to find cold began to reveal advantages. The stiff way of addressing strangers offered its own benefits, new ways in which I could conserve personal privacy in a world that constantly demanded oversharing. My conversations in French changed, too: I was finally talking to others not as a child but as an adult.

The author Yoko Tawada, who moved to Germany from Japan in her early 20s, works on books in both Japanese and German; she writes fluidly in both languages. Tawada’s most recent novel to be translated into English, “Scattered All Over the Earth,” explores a future in which Japan is sunken underwater, lost to climate change. A Japanese speaker, possibly the last on earth, looks for a man who she hopes shares her language, only to find that he has been pretending to be Japanese while working at a sushi restaurant.

Using new languages, or even staying within the state of multilingualism, can provide distinct creative advantages. Tawada plays with homonyms and the awkwardness that comes from literal translation. What emerges in her work is not a single language but a betweenness, a tool for the author to invent as she is using it, the scholar Yasemin Yildiz has noted. Yildiz quotes an essay by Tawada called “From the Mother Language to the Language Mother,” in which a narrator describes the ways that learning German taught her to see language differently: Writing in the second language was not a constraint, but a new form of invention. Tawada calls her typewriter a Sprachmutter, or “language mother” — an inversion of the German word for mother tongue. In a first language, we can rarely experience “playful joy,” she writes. “Thoughts cling so closely to words that neither the former nor the latter can fly freely.” But a new language is like a staple remover, which gets rid of everything that sticks and clings.

If the scholarly linguistic consensus once pushed people toward monolingualism, current research suggesting that language acquisition may shift with our circumstances may allow speakers of multiple languages to reclaim self-understanding. In Mirene Arsanios’s chapbook “Notes on Mother Tongues: Colonialism, Class and Giving What You Don’t Have,” Arsanios describes being unsure which language to speak with her son. Her mother, from Venezuela, spoke Spanish, her father, from Lebanon, spoke French; neither feels appropriate to pass on. “Like other languages originating in histories of colonization, my language always had a language problem, something akin to the evacuation of a ‘first’ or ‘native’ tongue — a syntax endemic to the brain and to the heart.”

Is the answer a multitude of languages or a renunciation of one? “Having many languages is my language’s dominant language,” she writes. She must become comfortable with the idea that what she is transmitting to her son is not a single language but questions and identities that are never quite resolved. At the end of the text, she describes speaking with her son “in a tongue reciprocal, abundant and motherless.”

The scholars I talked to stressed that each bilingual speaker is unique: Behind the general categories is a human life, with all its complications. Language acquisition and use may be messier than was envisioned by rigid distinctions of native and nonnative and, at the same time, more individual.

My own grandmother, my mother’s mother, grew up speaking German in Vienna in what was itself a multilingual household. Her mother was Austrian and her father, born in what is now Serbia, spoke German with a thick Hungarian accent. She and her family moved throughout Europe during World War II; to Budapest, Trieste, Lille and eventually escaped through Portugal on a boat carrying cork to New York.

When they arrived in the United States, her mother did not want her to speak German in public. “She felt the animosity to it,” my grandmother recently told me. But my grandmother still wished to. German was also the language of Schiller, she would say. She didn’t go out of her way to speak German, but she didn’t forget it either. She loved German poetry, much of which she still recites, often unprompted, at 95.

When I mentioned Schmid’s research to her, she was slightly dismissive of the idea that her own language use might be shaped by trauma. She said that she found the notion of not speaking German after World War II somewhat absurd, mostly because, to her ear, Hitler spoke very bad German. She berated me instead for not asking about her emotional relationship to French, which she spoke as a schoolgirl in Lille, or Italian, which she spoke in Trieste. Each was the source of memories that might wax and wane as she recalled the foreign words.

Recently, she reconnected with an old classmate from her childhood in Vienna, who also fled Europe during the war, after she recognized her friend’s picture in The New York Post. They speak together in English. Her friend Ruth, she notes, speaks English with a German accent, but does not speak German anymore.

Madeleine Schwartz lives in Paris, where she is founder and editor in chief of The Dial, a magazine of international reporting and writing. She was a finalist for the Orwell Prize for Journalism in 2023 and teaches journalism at Sciences Po Paris.

Read by Soneela Nankani

Narration produced by Tanya Pérez

Engineered by Brian St. Pierre

Explore The New York Times Magazine

Growing Up in Climate Chaos : Today’s teens were born into the global-warming crisis, but already it’s upending their adolescence — and will define their future.

How Instagram Posts Destroyed Her Life : On Oct. 7, an Israeli college student opened her phone. What she did next landed her in prison .

The Game Theory of Democracy : Countries where democracy is in trouble share a common pattern , and it’s a worrying one for the United States.

Peter Singer on ‘The Interview’ : The controversial philosopher discussed societal taboos, Thanksgiving turkeys and whether anyone is doing enough to make the world a better place .

Is A.I. Good for Hollywood?: The technology is powering visual innovations, like in the new movie “Here.” But boosters think that’s just the beginning .

Advertisement

Four Things That Happen When a Language Dies

This World Mother Language Day, read about why many say we should be fighting to preserve linguistic diversity

Kat Eschner

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/da/9c/da9c9279-1aff-46ba-8f6e-3ed33ef11543/mtff-image1.jpg)

Languages around the world are dying, and dying fast. Today is International Mother Language Day , started by UNESCO to promote the world's linguistic diversity.

The grimmest predictions have 90 percent of the world's languages dying out by the end of this century. Although this might not seem important in the day-to-day life of an English speaker with no personal ties to the culture in which they’re spoken, language loss matters. Here’s what we all lose:

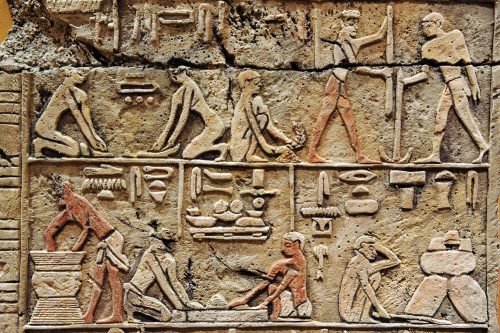

1. We lose “The expression of a unique vision of what it means to be human”

That’s what academic David Crystal told Paroma Basu for National Geographic in 2009. Basu was writing about India, a country with hundreds of languages , at least seven major language families and rapid language loss.

The effects of that language loss could be “culturally devastating,” Basu wrote. “Each language is a key that can unlock local knowledge about medicinal secrets, ecological wisdom, weather and climate patterns, spiritual attitudes and artistic and mythological histories.”

Languages have naturally risen and fallen in prominence throughout history, she wrote. What makes this different in India as well as throughout the world is the rate at which it’s happening and the number of languages disappearing.

2. We lose memory of the planet’s many histories and cultures.

The official language of Greenland, wrote Kate Yoder for Grist , is fascinating and unique. It’s “made up of extremely long words that can be customized to any occasion,” she writes. And there are as many of those words as there are sentences in English, one linguist who specializes in Greenlandic told her. Some of those, like words for different kinds of wind, are disappearing before linguists get the chance to explore them. And that disappearance has broader implications for the understanding of how humans process language, linguist Lenore Grenoble told Yoder. “There’s a lot we don’t know about how it works, or how the mind works when it does this,” she said.

Yoder’s article dealt with the effect of climate change on language loss. In sum: it hastens language loss as people migrate to more central, “safe” ground when their own land is threatened by intense storms, sea level rise, drought and other things caused by climate change. “When people settle in a new place, they begin a new life, complete with new surroundings, new traditions, and, yes, a new language,” she wrote.

3. We lose some of the best local resources for combatting environmental threats

As Nancy Rivenburgh wrote for the International Association of Conference Interpreters, what’s happening with today’s language loss is actually quite different from anything that happened before. Languages in the past disappeared and were born anew, she writes, but “they did so in a state of what linguists call ‘linguistic equilibrium.’ In the last 500 years, however, the equilibrium that characterized much of human history is now gone. And the world’s dominant languages—or what are often called ‘metropolitan’ languages—are all now rapidly expanding at the expense of ‘peripheral’ indigenous languages. Those peripheral languages are not being replaced.”

That means that out of the around 7000 languages that most reputable sources estimate are spoken globally, only the top 100 are widely spoken. And it isn’t just our understanding of the human mind that’s impaired, she writes. In many places, indigenous languages and their speakers are rich sources of information about the world around them and the plants and animals in the area where they live. In a time of mass extinction, that knowledge is especially precious.

“Medical science loses potential cures,” she writes. “Resource planners and national governments lose accumulated wisdom regarding the management of marine and land resources in fragile ecosystems.”

4. Some people lose their mother tongue.

The real tragedy of all this might just be all of the people who find themselves unable to speak their first language, the language they learned how to describe the world in. Some find themselves in the unenviable position of being one of the few (or the only ) speakers of their mother tongue. And some, like many of Canada’s indigenous peoples, find their language in grave danger as the result of a campaign by government to stamp out their cultures.

This loss is something beyond all the other losses, linguist John Lipski told Lisa Duchene for Penn State News: “Imagine being told you can’t use your language and you’ll see what that undefinable ‘more’ is,” he said.

What can you do about all this? Educate yourself, to start with. The Smithsonian's annual Mother Tongue Film Festival takes place every February in Washington, D.C. And projects like National Geographic 's " Enduring Voices " are a great place to learn about endangered languages and their many speakers, and UNESCO's own website is another resource. There's still hope for some of these languages if we pay attention.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Kat Eschner | | READ MORE

Kat Eschner is a freelance science and culture journalist based in Toronto.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Not addressing indigenous language loss represents a failure to protect indigenous people and their culture. Revitalising and rejuvenating indigenous languages and cultures is fundamental to improving mental health and wellbeing in these communities.

Languages: Why we must save dying tongues. Hundreds of our languages are teetering on the brink of extinction, and as Rachel Nuwer discovers, we may lose more than just words if we allow them to...

Greater education and mobility marginalize some minor languages. One language per month could disappear, without intervention. There are 7,000 documented languages currently spoken across the world, but half of them could be endangered, according to a new study.

More than 40 percent of the world’s estimated 7,100+ languages are in danger of disappearing by the end of this century. As with the decline of biodiversity, language loss has been attributed to environmental degradation, development, and the destruction of Indigenous communities.

The loss of language has been extensively explored in the following essays. The Pain of Losing Your First Language (Kristin Wong, Catapult, December 2021) This essay outlines the suffering Wong endured since foregoing her native language as a child for the sake of assimilating into America.

Language is the cultural glue that binds communities together. Language loss is a loss of community heritage—from histories and ancestral lineages known only through oral storytelling, to knowledge of plants and practices codified through words unwritten and untranslated.

This essay will look into the factors and causes of language shift and death, as well as the strategies that can assist in keeping our cultural diversity alive.

An issue of major importance to heritage language communities is language loss. Language loss can occur on two levels. It may be on a personal or familial level, which is often the case with immigrant communities in the United States, or the entire language may be lost when it ceases to be spoken at all. The latter scenario

In a paper written with the linguists Thomas H. Bak and Lourdes Ortega, Dewaele notes that many cultures link the first words you speak to motherhood: In French, your native language is a...

1. We lose “The expression of a unique vision of what it means to be human” That’s what academic David Crystal told Paroma Basu for National Geographic in 2009. Basu was writing about India, a...