You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Gr. 10 History T3 W4: Colonial expansion after 1750

Colonial expansion after 1750 - Britain takes control of the Cape.

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.

Home Contact us Terms of Use Privacy Policy Western Cape Government © 2024. All rights reserved.

Genius High

Colonial Expansion After 1750: A History Essay Analysis

Essay Topic

The period following 1750 witnessed a dramatic shift in the landscape of global colonialism. This era, marked by the conclusion of major European wars like the Seven Years' War, saw European powers, fueled by industrialization and new technologies, embark on a more aggressive and expansive phase of colonization. This essay delves into the key factors driving this expansion, examines its impact on the colonized world, and explores its lasting legacy.

Motivations for Colonial Expansion

Several factors converged to fuel this wave of colonialism. Industrialization in Europe created a demand for raw materials like cotton, rubber, and timber, which were readily available in the colonies. This economic imperative was further amplified by the need for new markets for manufactured goods, as Europe's population grew. Moreover, the pursuit of national prestige and geopolitical dominance played a significant role. The scramble for colonies became a way for European powers to assert their influence and demonstrate their strength on the global stage.

New Technologies and Military Dominance

The development of new technologies, such as steamships and railroads, facilitated easier and faster transportation, bolstering colonial expansion. Technological advancements in weaponry, like the breech-loading rifle, gave European powers a distinct military advantage, allowing them to subdue resistance and establish control over vast territories.

Impact on the Colonized World

The impact of colonial expansion was profound and multifaceted. Economic exploitation was a primary consequence, with colonies being forced to produce raw materials for the European market at the expense of their own development. Colonial rule also imposed European political and social structures, often undermining existing systems of governance and social organization. In addition, the introduction of European diseases, coupled with forced labor, led to widespread suffering and demographic decline in many colonized regions.

Resistance and Rebellion

Despite the power imbalances, colonial rule did not go unchallenged. Throughout the 19th century, numerous resistance movements emerged, ranging from local uprisings to large-scale rebellions. These challenges, while often unsuccessful in the short term, served to sow the seeds of anti-colonial sentiment that would later blossom into independence movements.

Legacy of Colonial Expansion

The legacy of colonial expansion is deeply intertwined with the modern world. It continues to shape political boundaries, economic structures, and social dynamics in former colonies. Many nations struggle with the lasting effects of colonial exploitation, including poverty, inequality, and political instability. However, colonial expansion also left a lasting legacy of cultural exchange, introducing new ideas, technologies, and practices to the colonized world.

The period of colonial expansion after 1750 was a transformative era in world history. Driven by economic motives, national ambitions, and technological advancements, it reshaped the global political landscape and left a complex and enduring legacy. Understanding this period is crucial for comprehending the modern world, its challenges, and its opportunities.

This analysis provides a brief overview of the key aspects of colonial expansion after 1750. Further research and exploration are encouraged to delve deeper into the specificities of this era, including the experiences of different colonized societies, the role of various colonial powers, and the diverse forms of resistance that emerged.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

- Early European trade with Asia

- Technological improvements

- Portugal’s seaborne empire

- The conquests

- Spanish colonial policies

- Europe’s shift to the Atlantic

- Changes in Europe

- Eastern pursuits

- Western pursuits

- Early settlements in the New World

- Activities in India

- Colonization of New France

- English ascendancy in India

- England’s American colonies

- The Spanish fleet system

- French mercantilist activities

- The English navigation acts

- Slave trade

- King William’s War (War of the League of Augsburg)

- Queen Anne’s War (War of the Spanish Succession)

- King George’s War (War of the Austrian Succession)

- The French and Indian War (the Seven Years’ War)

- Loss of the American colonies

- Conquest of India

- Global expansion

- Policy changes

- Involvement in Africa

- The growth of informal empire

- Anticolonial sentiment

- Decline of colonial rivalry

- Decline of the Spanish and Portuguese empires

- The emigration of European peoples

- Advance of the U.S. frontier

- New acquisitions

- New colonial powers

- Rise of new industrialized nations

- A world economy

- New militarism

- Economic imperialism

- Noneconomic imperialism

- Quest for a general theory of imperialism

- Russia’s eastward expansion

- The Opium Wars

- Foreign privileges in China

- The Open Door Policy

- Japan’s rise as a colonial power

- The Europeans in North Africa

- The race for colonies in sub-Saharan Africa

- Postwar redistribution of colonies

- Middle East

- Overseas France

- Axis Powers

- The United States and the Soviet Union

- British decolonization, 1945–56

- Wars in overseas France, 1945–56

- The Sinai-Suez campaign (October–November 1956)

- Algeria and French decolonization, from 1956

- British decolonization after 1956

- Dutch, Belgian, and Portuguese decolonization

- What was William Penn’s education?

- What is William Penn best known for?

- When did Charles de Gaulle become famous?

- What were Charles de Gaulle’s policies as president of France?

- When did Charles de Gaulle lose power?

European expansion since 1763

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Academia - Colonialism

- Hoover Institution - The Truth About Western “Colonialism”

- empire - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- empire - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

The global expansion of western Europe between the 1760s and the 1870s differed in several important ways from the expansionism and colonialism of previous centuries. Along with the rise of the Industrial Revolution , which economic historians generally trace to the 1760s, and the continuing spread of industrialization in the empire-building countries came a shift in the strategy of trade with the colonial world. Instead of being primarily buyers of colonial products (and frequently under strain to offer sufficient salable goods to balance the exchange), as in the past, the industrializing nations increasingly became sellers in search of markets for the growing volume of their machine-produced goods. Furthermore, over the years there occurred a decided shift in the composition of demand for goods produced in the colonial areas. Spices, sugar, and slaves became relatively less important with the advance of industrialization, concomitant with a rising demand for raw materials for industry ( e.g., cotton, wool, vegetable oils, jute, dyestuffs) and food for the swelling industrial areas (wheat, tea, coffee, cocoa, meat, butter).

This shift in trading patterns entailed in the long run changes in colonial policy and practice as well as in the nature of colonial acquisitions. The urgency to create markets and the incessant pressure for new materials and food were eventually reflected in colonial practices, which sought to adapt the colonial areas to the new priorities of the industrializing nations. Such adaptation involved major disruptions of existing social systems over wide areas of the globe. Before the impact of the Industrial Revolution, European activities in the rest of the world were largely confined to: (1) occupying areas that supplied precious metals, slaves, and tropical products then in large demand; (2) establishing white-settler colonies along the coast of North America; and (3) setting up trading posts and forts and applying superior military strength to achieve the transfer to European merchants of as much existing world trade as was feasible . However disruptive these changes may have been to the societies of Africa, South America , and the isolated plantation and white-settler colonies, the social systems over most of the Earth outside Europe nevertheless remained much the same as they had been for centuries (in some places for millennia). These societies, with their largely self-sufficient small communities based on subsistence agriculture and home industry, provided poor markets for the mass-produced goods flowing from the factories of the technologically advancing countries; nor were the existing social systems flexible enough to introduce and rapidly expand the commercial agriculture (and, later, mineral extraction) required to supply the food and raw material needs of the empire builders.

The adaptation of the nonindustrialized parts of the world to become more profitable adjuncts of the industrializing nations embraced, among other things: (1) overhaul of existing land and property arrangements, including the introduction of private property in land where it did not previously exist, as well as the expropriation of land for use by white settlers or for plantation agriculture; (2) creation of a labour supply for commercial agriculture and mining by means of direct forced labour and indirect measures aimed at generating a body of wage-seeking labourers; (3) spread of the use of money and exchange of commodities by imposing money payments for taxes and land rent and by inducing a decline of home industry; and (4) where the precolonial society already had a developed industry, curtailment of production and exports by native producers.

The classic illustration of this last policy is found in India . For centuries India had been an exporter of cotton goods, to such an extent that Great Britain for a long period imposed stiff tariff duties to protect its domestic manufacturers from Indian competition. Yet, by the middle of the 19th century, India was receiving one-fourth of all British exports of cotton piece goods and had lost its own export markets.

Clearly, such significant transformations could not get very far in the absence of appropriate political changes, such as the development of a sufficiently cooperative local elite, effective administrative techniques, and peace-keeping instruments that would assure social stability and environments conducive to the radical social changes imposed by a foreign power. Consistent with these purposes was the installation of new, or amendments of old, legal systems that would facilitate the operation of a money, business, and private land economy. Tying it all together was the imposition of the culture and language of the dominant power.

The changing nature of the relations between centres of empire and their colonies, under the impact of the unfolding Industrial Revolution, was also reflected in new trends in colonial acquisitions. While in preceding centuries colonies, trading posts, and settlements were in the main, except for South America, located along the coastline or on smaller islands, the expansions of the late 18th century and especially of the 19th century were distinguished by the spread of the colonizing powers, or of their emigrants, into the interior of continents. Such continental extensions, in general, took one of two forms, or some combination of the two: (1) the removal of the indigenous peoples by killing them off or forcing them into specially reserved areas, thus providing room for settlers from western Europe who then developed the agriculture and industry of these lands under the social system imported from the mother countries, or (2) the conquest of the indigenous peoples and the transformation of their existing societies to suit the changing needs of the more powerful militarily and technically advanced nations.

At the heart of Western expansionism was the growing disparity in technologies between those of the leading European nations and those of the rest of the world. Differences between the level of technology in Europe and some of the regions on other continents were not especially great in the early part of the 18th century. In fact, some of the crucial technical knowledge used in Europe at that time came originally from Asia . During the 18th century, however, and at an accelerating pace in the 19th and 20th centuries, the gap between the technologically advanced countries and technologically backward regions kept on increasing despite the diffusion of modern technology by the colonial powers. The most important aspect of this disparity was the technical superiority of Western armaments, for this superiority enabled the West to impose its will on the much larger colonial populations. Advances in communication and transportation, notably railroads, also became important tools for consolidating foreign rule over extensive territories. And along with the enormous technical superiority and the colonizing experience itself came important psychological instruments of minority rule by foreigners: racism and arrogance on the part of the colonizers and a resulting spirit of inferiority among the colonized.

Naturally, the above description and summary telescope events that transpired over many decades and the incidence of the changes varied from territory to territory and from time to time, influenced by the special conditions in each area, by what took place in the process of conquest, by the circumstances at the time when economic exploitation of the possessions became desirable and feasible, and by the varying political considerations of the several occupying powers. Moreover, it should be emphasized that expansion policies and practices, while far from haphazard, were rarely the result of long-range and integrated planning. The drive for expansion was persistent, as were the pressures to get the greatest advantage possible out of the resulting opportunities. But the expansions arose in the midst of intense rivalry among major powers that were concerned with the distribution of power on the continent of Europe itself as well as with ownership of overseas territories. Thus, the issues of national power, national wealth, and military strength shifted more and more to the world stage as commerce and territorial acquisitions spread over larger segments of the globe. In fact, colonies were themselves often levers of military power—sources of military supplies and of military manpower and bases for navies and merchant marines. What appears, then, in tracing the concrete course of empire is an intertwining of the struggle for hegemony between competing national powers, the manoeuvring for preponderance of military strength, and the search for greatest advantage practically obtainable from the world’s resources.

European colonial activity (1763–c. 1875)

Stages of history rarely, if ever, come in neat packages: the roots of new historical periods begin to form in earlier eras, while many aspects of an older phase linger on and help shape the new. Nonetheless, there was a convergence of developments in the early 1760s, which, despite many qualifications, delineates a new stage in European expansionism and especially in that of the most successful empire builder, Great Britain. It is not only the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain that can be traced to this period but also the consequences of England’s decisive victory over France in the Seven Years’ War and the beginnings of what turned out to be the second British Empire . As a result of the Treaty of Paris, France lost nearly all of its colonial empire, while Britain became, except for Spain , the largest colonial power in the world.

The second British Empire

The removal of threat from the strongest competing foreign power set the stage for Britain’s conquest of India and for operations against the North American Indians to extend British settlement in Canada and westerly areas of the North American continent. In addition, the new commanding position on the seas provided an opportunity for Great Britain to probe for additional markets in Asia and Africa and to try to break the Spanish trade monopoly in South America. During this period, the scope of British world interests broadened dramatically to cover the South Pacific, the Far East, the South Atlantic, and the coast of Africa.

The initial aim of this outburst of maritime activity was not so much the acquisition of extensive fresh territory as the attainment of a far-flung network of trading posts and maritime bases. The latter, it was hoped, would serve the interdependent aims of widening foreign commerce and controlling ocean shipping routes. But in the long run many of these initial bases turned out to be steppingstones to future territorial conquests. Because the indigenous populations did not always take kindly to foreign incursions into their homelands, even when the foreigners limited themselves to small enclaves, penetration of interiors was often necessary to secure base areas against attack.

Colonial Expansion and the Transition of Land

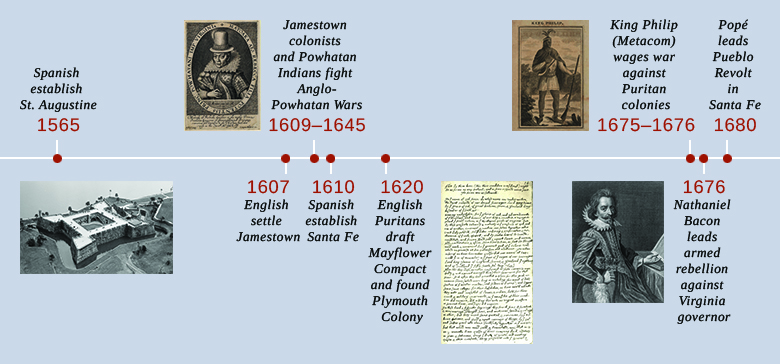

When the British colonists landed in North America at the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts, they lived peacefully with Native Americans for about 60 years before tensions escalated into King Philip’s War. King Philip’s War resulted from the resentment of colonial expansion and almost ended the colonial presence in the area. Ultimately, the Native Americans were forced off their ancestral land and extensive colonial expansion began to be promoted.

Geography, Human Geography, Social Studies, U.S. History, Storytelling

Loading ...

Ideas for Use in the Classroom Introduce the lesson by summarizing the traditional tale of Thanksgiving, or of cooperation and friendship between Native Americans and English colonists. Show students the maps of Wampanoag Territory and the New England colonies in 1677, and have them report out how the area changed after the English colonists arrived. Explain that the Wampanoag are part of the Algonquin people and among the first of the Native Americans to encounter those colonists. Therefore, the interaction between them was the first attempt of both groups to live together peacefully, and for a while, they succeeded. Show the map “ Growth of Colonial Settlement ,” displaying it next to the first two maps, to show historical order. Introduce the idea of using maps as a storytelling device. As a class, outline the story of the European/Native American interaction in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, using information from the maps. Then have students state their predictions of what happened between the Wampanoag and the colonists that led to colonial expansion . Were their predictions correct? Use the articles below to explain the conflicts that took place between the Wampanoag and the colonists and that led to King Philip’s War. Describe the major events of the conflict, pointing out the locations in the conflicts and noting the range of territory involved.

Articles & Profiles

Media credits.

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

August 7, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2 Chapter 2: Creating New Social Orders: Colonial Societies, 1500–1750

Creating New Social Orders: Colonial Societies, 1500–1750

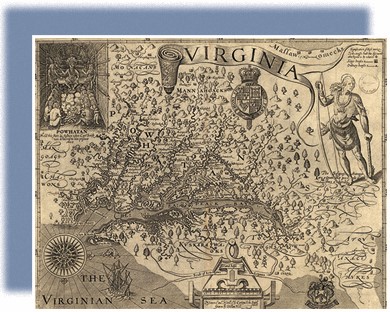

John Smith’s famous map of Virginia (1622) illustrates many geopolitical features of early colonization. In the upper left, Powhatan, who governed a powerful local confederation of Algonquian communities, sits above other local chiefs, denoting his authority. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Chapter Outline

Introduction , Watch and Learn , Questions to Guide your Reading

2.1 Spanish Exploration and Colonial Society

2.2 Colonial Rivalr ies: Dutch and French Colonial Ambition s

2.3 English Settlements in America

2.4 the impact of colonization.

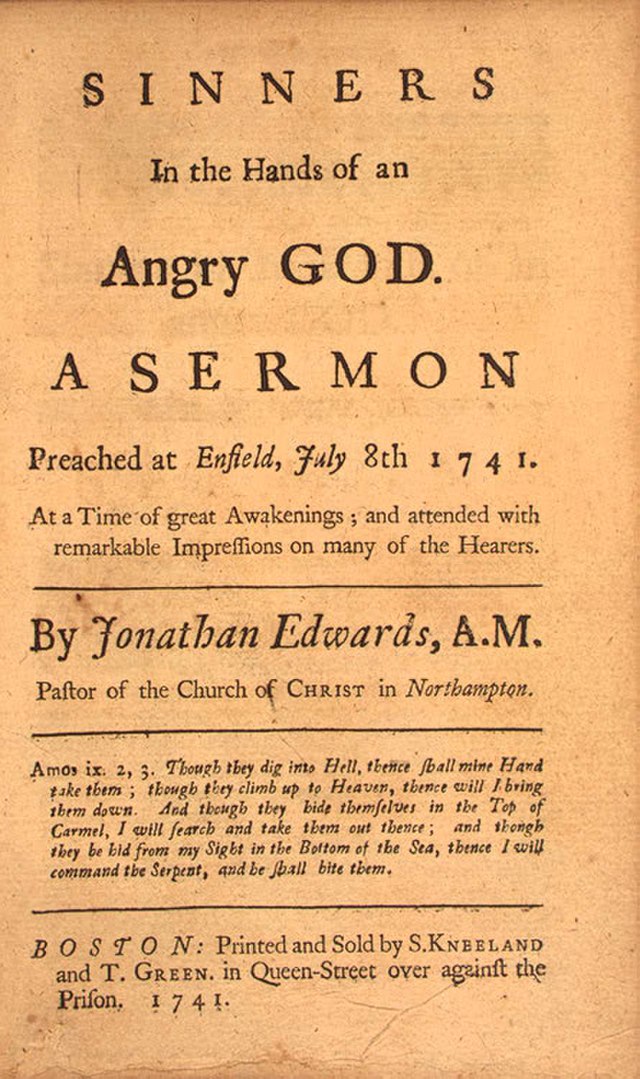

2.5 The Great Awakening and Enlightenment

Summary Timelines , Chapter 2 Self-Test , Chapter 2 Key Terms Crossword Puzzle

Introduction

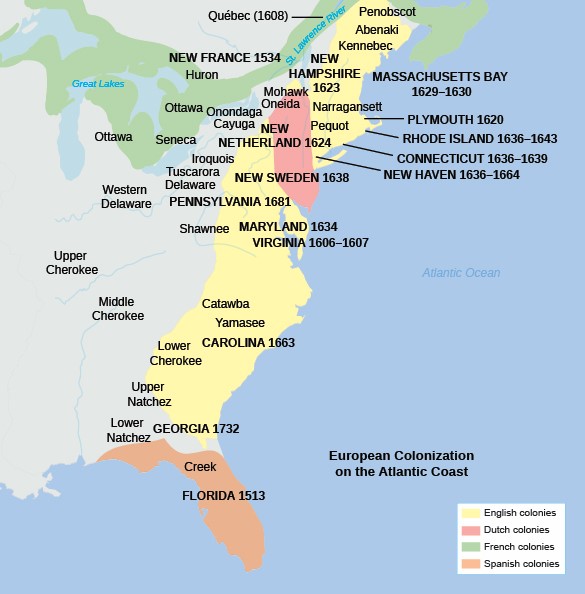

By the mid-seventeenth century, the geopolitical map of North America had become a patchwork of imperial designs and ambitions as the Spanish, Dutch, French, and English reinforced their claims to parts of the land. Uneasiness, punctuated by violent clashes, prevailed in the border zones between the Europeans’ territorial claims. Meanwhile, still-powerful native peoples waged war to drive the invaders from the continent. In the Chesapeake Bay and New England colonies, conflicts erupted as the English pushed against their native neighbors.

The rise of colonial societies in the Americas brought Native Americans, Africans, and Europeans together for the first time, highlighting the radical social, cultural, and religious differences that hampered their ability to understand each other. European settlement affected every aspect of the land and its people, bringing goods, ideas, and diseases that transformed the Americas. Reciprocally, Native American practices, such as the use of tobacco, profoundly altered European habits and tastes.

The eighteenth century witnessed the birth of Great Britain (after the union of England and Scotland in 1707) and the expansion of the British Empire. By the mid-1700s, Great Britain had developed into a commercial and military powerhouse; its economic sway ranged from India, where the British East India Company had gained control over both trade and territory, to the West African coast, where British slave traders predominated, and to the British West Indies, whose lucrative sugar plantations, especially in Barbados and Jamaica, provided windfall profits for British planters. Meanwhile, the population rose dramatically in Britain’s North American colonies. In the early 1700s the population in the colonies had reached 250,000. By 1750, however, over a million British migrants and enslaved people from Africa had established a near-continuous zone of settlement on the Atlantic coast from Maine to Georgia.

Watch and Learn (Crash Course in History videos for chapter 2)

- When is Thanksgiving? Colonizing America

- The Natives and the English

- The Quakers, the Dutch, and the Ladies

- Slavery in the American Colonies

- Slave Codes

- The Stono Rebellion

Questions to Guide Your Reading

- Compare and contrast life in the Spanish, French, Dutch, and English colonies, differentiating between the Chesapeake Bay and New England colonies. Who were the colonizers? What were their purposes in being there? How did they interact with their environments and the native inhabitants of the lands on which they settled?

- Describe the attempts of the various European colonists to convert native peoples to their belief systems. How did these attempts compare to one another? What were the results of each effort?

- How did chattel slavery differ from indentured servitude? How did the former system come to replace the latter? What were the results of this shift?

- How did Pennsylvania’s Quaker beginnings distinguish it from other colonies in British America?

- What impact did Europeans have on the American environments—native peoples and their communities as well as land, plants, and animals? Conversely, what impact did the America’s native inhabitants, land, plants, and animals have on Europeans? How did the interaction of European and Indian societies, together, shape a world that was truly “new”?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the main Spanish American colonial settlements of the 1500s and 1600s

During the 1500s, Spain expanded its colonial empire to areas in the Americas that later became the United States. The Spanish dreamed of mountains of gold and silver and imagined converting thousands of eager Indians to Catholicism. In their vision of colonial society, everyone would know his or her place. Patriarchy (the rule of men over family, society, and government) shaped the Spanish colonial world. Women occupied a lower status. In all matters, the Spanish held themselves to be atop the social pyramid, with native peoples and Africans beneath them. Everywhere the Spanish settled, they brought devastating diseases, such as smallpox, that led to a horrific loss of life among native peoples. European diseases killed far more native inhabitants than did Spanish swords.

The world native peoples had known before the coming of the Spanish was further upset by Spanish colonial practices. The Spanish imposed the encomienda system in the areas they controlled. Under this system, authorities assigned Indian workers to mine and plantation owners with the understanding that the recipients would defend the colony and teach the workers the tenets of Christianity. In reality, the encomienda system exploited native workers. It was eventually replaced by another colonial labor system, the repartimiento , which required Indian towns to supply a pool of labor for Spanish overlords.

ST. AUGUSTINE, FLORIDA

Spain gained a foothold in present-day Florida, viewing that area and the lands to the north as an extension of their Caribbean empire. In 1513, Juan Ponce de León claimed the area around today’s St. Augustine for the Spanish crown. In 1565, the victorious Menéndez founded St. Augustine, now the oldest European settlement in the Americas. In the process, the Spanish displaced the local Timucua Indians from their ancient town of Seloy, which had stood for thousands of years. The Timucua suffered greatly from diseases introduced by the Spanish, shrinking from a population of around 200,000 pre-contact to fifty thousand in 1590. By 1700, only one thousand Timucua remained. As in other areas of Spanish conquest, Catholic priests worked to bring about a spiritual conquest by forcing the surviving Timucua, demoralized and reeling from catastrophic losses of family and community, to convert to Catholicism.

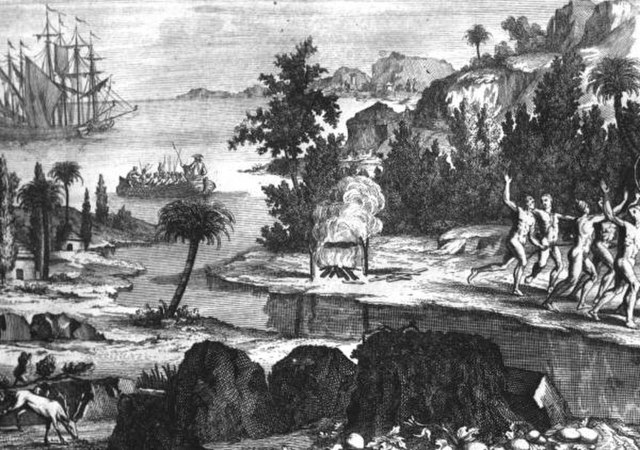

In this drawing by French artist Jacques le Moyne de Morgues, Timucua flee the Spanish settlers, who arrive by ship. Le Moyne lived at Fort Caroline, the French outpost, before the Spanish destroyed the colony in 1562. Source: Wikimedia Commons

SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO

Farther west, the Spanish in Mexico, intent on expanding their empire, looked north to the land of the Pueblo Indians. Juan de Oñate explored the American southwest for Spain in the late 1590s. The Spanish hoped that what we know as New Mexico would yield gold and silver, but the land produced little of value to them. In 1610, Spanish settlers established themselves at Santa Fe where many Pueblo villages were located. Santa Fe became the capital of the Kingdom of New Mexico, an outpost of the larger Spanish Viceroyalty of New Spain, which had its headquarters in Mexico City.

As they had in other Spanish colonies, Franciscan missionaries labored to bring about a spiritual conquest by converting the Pueblo to Catholicism. At first, the Pueblo adopted the parts of Catholicism that dovetailed with their own long-standing view of the world. However, Spanish priests insisted that natives discard their old ways entirely and angered the Pueblo by focusing on the young, drawing them away from their parents. This deep insult, combined with an extended period of drought and increased attacks by local Apache and Navajo in the 1670s—troubles that the Pueblo came to believe were linked to the Spanish presence—moved the Pueblo to push the Spanish and their religion from the area.

In 1680, the Pueblo launched a coordinated rebellion against the Spanish. The Pueblo Revolt killed over four hundred Spaniards and drove the rest of the settlers, perhaps as many as two thousand, south toward Mexico. However, as droughts and attacks by rival tribes continued, the Spanish sensed an opportunity to regain their foothold. In 1692, they returned and reasserted their control of the area. Some of the Spanish explained the Pueblo success in 1680 as the work of the Devil. Satan, they believed, had stirred up the Pueblo to take arms against God’s chosen people—the Spanish—but the Spanish, and their God, had prevailed in the end.

2.1 Section Summary

In their outposts at St. Augustine and Santa Fe, the Spanish never found the fabled mountains of gold they sought. They did find many native people to convert to Catholicism, but their zeal nearly cost them the colony of Santa Fe, which they lost for twelve years after the Pueblo Revolt. In truth, the grand dreams of wealth, conversion, and a social order based on Spanish control never came to pass as Spain envisioned them.

2.2 Colonial Rivalries: Dutch and French Colonial Ambitions

- Compare and contrast the development and character of the French and Dutch colonies in North America

- Discuss the economies of the French and Dutch colonies in North America

Seventeenth-century French and Dutch colonies in North America were modest in comparison to Spain’s colossal global empire. New France and New Netherland remained small commercial operations focused on the fur trade and did not attract an influx of migrants. The Dutch in New Netherland confined their operations to Manhattan Island, Long Island, the Hudson River Valley, and what later became New Jersey. Dutch trade goods circulated widely among the native peoples in these areas and also traveled well into the interior of the continent along preexisting native trade routes. French habitants , or farmer-settlers, eked out an existence along the St. Lawrence River. French fur traders and missionaries, however, ranged far into the interior of North America, exploring the Great Lakes region and the Mississippi River. These pioneers gave France somewhat inflated imperial claims to lands that nonetheless remained firmly under the dominion of native peoples.

FUR TRADING IN NEW NETHERLAND

The Dutch Republic emerged as a major commercial center in the 1600s. Its fleets plied the waters of the Atlantic, while other Dutch ships sailed to the Far East, returning with prized spices like pepper to be sold in the bustling ports at home, especially Amsterdam. In North America, Dutch traders established themselves first on Manhattan Island.

One of the Dutch directors-general of the North American settlement, Peter Stuyvesant, served from 1647 to 1664. He expanded the fledgling outpost of New Netherland east to present-day Long Island, and for many miles north along the Hudson River. The resulting elongated colony served primarily as a fur-trading post, with the powerful Dutch West India Company controlling all commerce. Fort Amsterdam, on the southern tip of Manhattan Island, defended the growing city of New Amsterdam. In 1655, Stuyvesant took over the small outpost of New Sweden along the banks of the Delaware River in present-day New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. He also defended New Amsterdam from Indian attacks by ordering enslaved people from Africa to build a protective wall on the city’s northeastern border, giving present-day Wall Street its name.

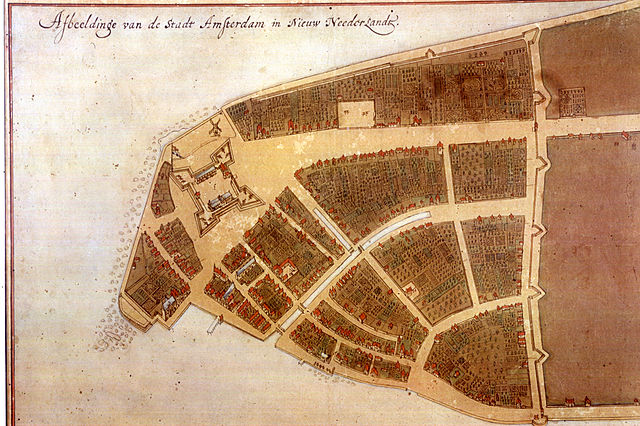

The Castello Plan is the only extant map of 1660 New Amsterdam (present-day New York City). The line with spikes on the right side of the colony is the northeastern wall for which Wall Street was named. Source: Wikimedia Commons

New Netherland failed to attract many Dutch colonists; by 1664, only nine thousand people were living there. Conflict with native peoples, as well as dissatisfaction with the Dutch West India Company’s trading practices, made the Dutch outpost an undesirable place for many migrants. The small size of the population meant a severe labor shortage, and to complete the arduous tasks of early settlement, the Dutch West India Company imported some 450 African slaves between 1626 and 1664. (The company had involved itself heavily in the slave trade and in 1637 captured Elmina, the slave-trading post on the west coast of Africa, from the Portuguese.) The shortage of labor also meant that New Netherland welcomed non-Dutch immigrants, including Protestants from Germany, Sweden, Denmark, and England, and embraced a degree of religious tolerance, allowing Jewish immigrants to become residents beginning in the 1650s. Thus, a wide variety of people lived in New Netherland from the start. Indeed, one observer claimed eighteen different languages could be heard on the streets of New Amsterdam. As new settlers arrived, the colony of New Netherland stretched farther to the north and the west.

The Dutch West India Company found the business of colonization in New Netherland to be expensive. To share some of the costs, it granted Dutch merchants who invested heavily in it patroonships, or large tracts of land and the right to govern the tenants there. In return, the shareholder who gained the patroonship promised to pay for the passage of at least thirty Dutch farmers to populate the colony. One of the largest patroonships was granted to Kiliaen van Rensselaer, one of the directors of the Dutch West India Company; it covered most of present-day Albany and Rensselaer Counties. This pattern of settlement created a yawning gap in wealth and status between the tenants, who paid rent, and the wealthy patroons.

During the summer trading season, Indians gathered at trading posts such as the Dutch site at Beverwijck (present-day Albany), where they exchanged furs for guns, blankets, and alcohol. The furs, especially beaver pelts destined for the lucrative European millinery market, were then sent down the Hudson River to New Amsterdam where enslaved people and/or workers loaded them aboard ships bound for Amsterdam.

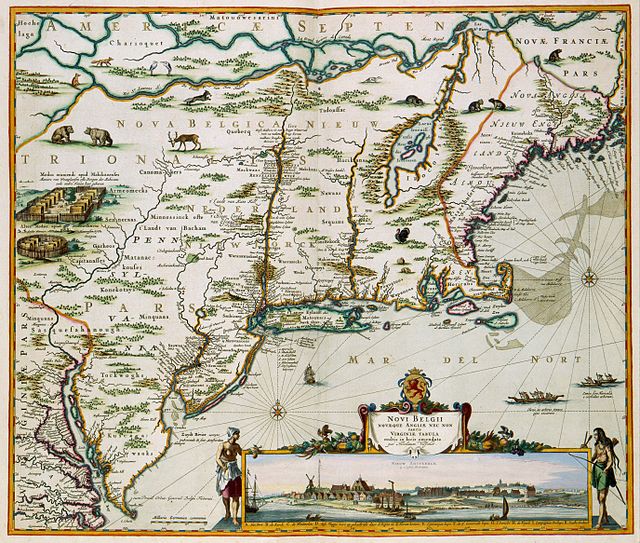

This 1684 map of New Netherland shows the extent of Dutch settlement. Source: Wikimedia Commons

COMMERCE AND CONVERSION IN NEW FRANCE

After Jacques Cartier’s voyages of discovery in the 1530s, France showed little interest in creating permanent colonies in North America until the early 1600s, when Samuel de Champlain established Quebec as a French fur-trading outpost. Although the fur trade was lucrative, the French saw Canada as an inhospitable frozen wasteland, and by 1640, fewer than four hundred settlers had made their home there. The sparse French presence meant that colonists depended on the local native Algonquian people; without them, the French would have perished. French fishermen, explorers, and fur traders made extensive contact with the Algonquian. The Algonquian, in turn, tolerated the French because the colonists supplied them with firearms for their ongoing war with the Iroquois. Thus, the French found themselves escalating native wars and supporting the Algonquian against the Iroquois, who received weapons from their Dutch trading partners. These seventeenth-century conflicts centered on the lucrative trade in beaver pelts, earning them the name of the Beaver Wars. In these wars, fighting between rival native peoples spread throughout the Great Lakes region.

A handful of French Jesuit priests also made their way to Canada, intent on converting the native inhabitants to Catholicism. The Jesuits were members of the Society of Jesus, an elite religious order founded in the 1540s to spread Catholicism and combat the spread of Protestantism. The first Jesuits arrived in Quebec in the 1620s, and for the next century, their numbers did not exceed forty priests. Like the Spanish Franciscan missionaries, the Jesuits in the colony called New France labored to convert the native peoples to Catholicism. They wrote detailed annual reports about their progress in bringing the faith to the Algonquian and, beginning in the 1660s, to the Iroquois. These documents are known as the Jesuit Relations , and they provide a rich source for understanding both the Jesuit view of the Indians and the Indian response to the colonizers.

|

|

|

|

The provide incredible detail about Indian life. For example, the 1636 edition, written by the Catholic priest Jean de Brébeuf, addresses the devastating effects of disease on native peoples and the efforts made to combat it. “Let us return to the feasts. The is a remedy which is only for one particular kind of disease, which they call also , from the name of a little Demon as large as the fist, which they say is in the body of the sick man, especially in the part which pains him. They find out that they are sick of this disease, by means of a dream, or by the intervention of some Sorcerer. . . . Of three kinds of games especially in use among these Peoples,—namely, the games of crosse [lacrosse], dish, and straw,—the first two are, they say, most healing. Is not this worthy of compassion? There is a poor sick man, fevered of body and almost dying, and a miserable Sorcerer will order for him, as a cooling remedy, a game of crosse. Or the sick man himself, sometimes, will have dreamed that he must die unless the whole country shall play crosse for his health; and, no matter how little may be his credit, you will see then in a beautiful field, Village contending against Village, as to who will play crosse the better, and betting against one another Beaver robes and Porcelain collars, so as to excite greater interest.” | |

2.2 Section Summary

The French and Dutch established colonies in the northeastern part of North America: the Dutch in present-day New York, and the French in present-day Canada. Both colonies were primarily trading posts for furs. While they failed to attract many colonists from their respective home countries, these outposts nonetheless intensified imperial rivalries in North America. Both the Dutch and the French relied on native peoples to harvest the pelts that proved profitable in Europe.

- Identify the English settlements in America and their unique characteristics

- Describe the differences between the Chesapeake Bay colonies and the New England colonies

- Describe the impact of English settlement on Native peoples

- Explain the role of Bacon’s Rebellion in the rise of chattel slavery in Virginia

At the start of the seventeenth century, the English had not established a permanent settlement in the Americas. Over the next century, however, they outpaced their rivals. The English encouraged emigration far more than the Spanish, French, or Dutch. They established nearly a dozen colonies, sending swarms of immigrants to populate the land. England had experienced a dramatic rise in population in the sixteenth century, and the colonies appeared a welcoming place for those who faced overcrowding and grinding poverty at home. Thousands of English migrants arrived in the Chesapeake Bay colonies of Virginia and Maryland to work in the tobacco fields. Another stream, this one of pious Puritan families, sought to live as they believed scripture demanded and established the Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, New Haven, Connecticut, and Rhode Island colonies of New England.

THE DIVERGING CULTURES OF THE NEW ENGLAND AND CHESAPEAKE COLONIES

Promoters of English in North America, many of whom never ventured across the Atlantic, wrote about the bounty the English would find there. These boosters of colonization hoped to turn a profit—whether by importing raw resources or providing new markets for English goods—and spread Protestantism. The English migrants who actually made the journey, however, had different goals. In Chesapeake Bay, English migrants established Virginia and Maryland with a decidedly commercial orientation. Though the early Virginians at Jamestown hoped to find gold, they and the settlers in Maryland quickly discovered that growing tobacco was the only sure means of making money. Thousands of unmarried, unemployed, and impatient young Englishmen, along with a few Englishwomen, pinned their hopes for a better life on the tobacco fields of these two colonies.

A very different group of English men and women flocked to the cold climate and rocky soil of New England, spurred by religious motives. Many of the Puritans crossing the Atlantic were people who brought families and children. Often they followed their ministers in a migration “beyond the seas,” envisioning a new English Israel where reformed Protestantism would grow and thrive, providing a model for the rest of the Christian world and a counter to what they saw as the Catholic menace. While the English in Virginia and Maryland worked on expanding their profitable tobacco fields, the English in New England built towns focused on the church, where each congregation decided what was best for itself.

The source of those differences lay in England’s domestic problems. Increasingly in the early 1600s, the English state church—the Church of England, established in the 1530s—demanded conformity, or compliance with its practices, but Puritans pushed for greater reforms. By the 1620s, the Church of England began to see leading Puritan ministers and their followers as outlaws, a national security threat because of their opposition to its power. As the noose of conformity tightened around them, many Puritans decided to remove to New England. By 1640, New England had a population of twenty-five thousand. Meanwhile, many loyal members of the Church of England, who ridiculed and mocked Puritans both at home and in New England, flocked to Virginia for economic opportunity.

The troubles in England escalated in the 1640s when civil war broke out, pitting Royalist supporters of King Charles I and the Church of England against Parliamentarians, the Puritan reformers and their supporters in Parliament. In 1649, the Parliamentarians gained the upper hand and, in an unprecedented move, executed Charles I. In the 1650s, therefore, England became a republic, a state without a king. English colonists in America closely followed these events. Indeed, many Puritans left New England and returned home to take part in the struggle against the king and the national church. Other English men and women in the Chesapeake colonies and elsewhere in the English Atlantic World looked on in horror at the mayhem the Parliamentarians, led by the Puritan insurgents, appeared to unleash in England. The turmoil in England made the administration and imperial oversight of the Chesapeake and New England colonies difficult, and the two regions developed divergent cultures.

THE CHESAPEAKE COLONIES: VIRGINIA AND MARYLAND

The Chesapeake colonies of Virginia and Maryland served a vital purpose in the developing seventeenth century English empire by providing tobacco, a cash crop. However, the early history of Jamestown did not suggest the English outpost would survive. From the outset, its settlers struggled both with each other and with the native inhabitants, the powerful Powhatan, who controlled the area. Jealousies and infighting among the English destabilized the colony. One member, John Smith, took control and exercised near-dictatorial powers, which furthered aggravated the squabbling. The settlers’ inability to grow their own food compounded this unstable situation.

Early Struggles and the Development of the Tobacco Economy

Poor health, lack of food, and fighting with native peoples took the lives of many of the original Jamestown settlers. The winter of 1609–1610, which became known as “the starving time,” came close to annihilating the colony. By June 1610, the few remaining settlers had decided to abandon the area; only the last minute arrival of a supply ship from England prevented another failed colonization effort. The supply ship brought new settlers, but only twelve-hundred of the seventy-five hundred who came to Virginia between 1607 and 1624 survived.

To meet these labor demands, early Virginians relied on indentured servants. An indenture is a labor contract that young, impoverished, and often illiterate Englishmen and occasionally Englishwomen signed in England, pledging to work for a number of years (usually between five and seven) growing tobacco in the Chesapeake colonies. In return, indentured servants received paid passage to America and food, clothing, and lodging. At the end of their indenture servants received “freedom dues,” usually food and other provisions, including, in some cases, land provided by the colony. The promise of a new life in America was a strong attraction for members of England’s underclass, who had few if any options at home. In the 1600s, some 100,000 indentured servants traveled to the Chesapeake Bay. Most were poor young men in their early twenties.

Life in the colonies proved harsh, however. Indentured servants could not marry, and they were subject to the will of the tobacco planters who bought their labor contracts. If they committed a crime or disobeyed their masters, they found their terms of service lengthened, often by several years. Female indentured servants faced special dangers in what was essentially a bachelor colony. Many were exploited by unscrupulous tobacco planters who seduced them with promises of marriage. These planters would then sell their pregnant servants to other tobacco planters to avoid the costs of raising a child.

Nonetheless, those indentured servants who completed their term of service often began new lives as tobacco planters. To entice even more migrants to the Americas, the Virginia Company also implemented the headright system , in which those who paid their own passage to Virginia received fifty acres plus an additional fifty for each servant or family member they brought with them. The headright system and the promise of a new life for servants acted as powerful incentives for English migrants to hazard the journey to the Americas.

|

|

|

|

George Percy, the youngest son of an English nobleman, was in the first group of settlers at the Jamestown Colony. He kept a journal describing their experiences; in the excerpt below, he reports on the privations of the colonists’ third winter. “Now all of us at James Town, beginning to feel that sharp prick of hunger which no man truly describe but he which has tasted the bitterness thereof, a world of miseries ensued as the sequel will express unto you, in so much that some to satisfy their hunger have robbed the store for the which I caused them to be executed. Then having fed upon horses and other beasts as long as they lasted, we were glad to make shift with vermin as dogs, cats, rats, and mice. All was fish that came to net to satisfy cruel hunger as to eat boots, shoes, or any other leather some could come by, and, those being spent and devoured, some were enforced to search the woods and to feed upon serpents and snakes and to dig the earth for wild and unknown roots, where many of our men were cut off of and slain by the savages. And now famine beginning to look ghastly and pale in every face that nothing was spared to maintain life and to do those things which seem incredible as to dig up dead corpses out of graves and to eat them, and some have licked up the blood which has fallen from their weak fellows.” —George Percy, “A True Relation of the Proceedings and Occurances of Moment which have happened in Virginia from the Time Sir Thomas Gates shipwrecked upon the Bermudes anno 1609 until my departure out of the Country which was in anno Domini 1612,” London 1624 | |

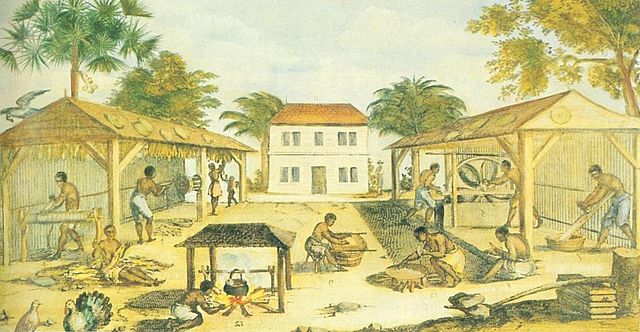

The Rise of Slavery in the Chesapeake Bay Colonies

The transition from indentured servitude to slavery as the main labor source for some English colonies happened first in the West Indies. On the small island of Barbados, colonized in the 1620s, English planters first grew tobacco as their main export crop, but in the 1640s, they converted to sugarcane and began increasingly to rely on enslaved people from Africa. In 1655, England wrestled control of Jamaica from the Spanish and quickly turned it into a lucrative sugar island, run on slave labor, for its expanding empire. While slavery was slower to take hold in the Chesapeake colonies, by the end of the seventeenth century, both Virginia and Maryland had also adopted chattel slavery—which legally defined Africans as property and not people—as the dominant form of labor to grow tobacco. Chesapeake colonists also enslaved native people.

When the first Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619, slavery—which did not exist in England—had not yet become an institution in colonial America. Many Africans worked as servants and, like their white counterparts, could acquire land of their own. Some Africans who converted to Christianity became free landowners with white servants. The change in the status of Africans in the Chesapeake to that of enslaved people occurred in the last decades of the seventeenth century.

In this 1670 painting by an unknown artist, enslaved people work in tobacco-drying sheds. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Bacon’s Rebellion, an uprising of both whites and blacks who believed that the Virginia government was impeding their access to land and wealth and doing little to clear the land of Indians, hastened the transition to African slavery in the Chesapeake colonies. The rebellion takes its name from Nathaniel Bacon, a wealthy young Englishman who arrived in Virginia in 1674. Despite an early friendship with Virginia’s royal governor, William Berkeley, Bacon found himself excluded from the governor’s circle of influential friends and councilors. He wanted land on the Virginia frontier, but the governor, fearing war with neighboring Indian tribes, forbade further expansion. Bacon marshaled others, especially former indentured servants who believed the governor was limiting their economic opportunities and denying them the right to own tobacco farms. Bacon’s followers believed Berkeley’s frontier policy didn’t protect English settlers enough. Worse still in their eyes, Governor Berkeley tried to keep peace in Virginia by signing treaties with various local native peoples. Bacon and his followers, who saw all Indians as an obstacle to their access to land, pursued a policy of extermination.

Tensions between the English and the native peoples in the Chesapeake colonies led to open conflict. In 1675, war broke out when Susquehannock warriors attacked settlements on Virginia’s frontier, killing English planters and destroying English plantations, including one owned by Bacon. In 1676, Bacon and other Virginians attacked the Susquehannock without the governor’s approval. When Berkeley ordered Bacon’s arrest, Bacon led his followers to Jamestown, forced the governor to flee to the safety of Virginia’s eastern shore, and then burned the city. The civil war known as Bacon’s Rebellion, a vicious struggle between supporters of the governor and those who supported Bacon, ensued. Reports of the rebellion traveled back to England, leading Charles II to dispatch both royal troops and English commissioners to restore order in the tobacco colonies. By the end of 1676, Virginians loyal to the governor gained the upper hand, executing several leaders of the rebellion. Bacon escaped the hangman’s noose, instead dying of dysentery. The rebellion fizzled in 1676, but Virginians remained divided as supporters of Bacon continued to harbor grievances over access to Indian land.

Bacon’s Rebellion helped to catalyze the creation of a system of racial slavery in the Chesapeake colonies. At the time of the rebellion, indentured servants made up the majority of laborers in the region. Wealthy whites worried over the presence of this large class of laborers and the relative freedom they enjoyed, as well as the alliance that black and white servants had forged in the course of the rebellion. Replacing indentured servitude with black slavery diminished these risks, alleviating the reliance on white indentured servants, who were often dissatisfied and troublesome, and creating a caste of racially defined laborers whose movements were strictly controlled. It also lessened the possibility of further alliances between black and white workers. Racial slavery even served to heal some of the divisions between wealthy and poor whites, who could now unite as members of a “superior” racial group.

While colonial laws in the tobacco colonies had made slavery a legal institution before Bacon’s Rebellion, new laws passed in the wake of the rebellion severely curtailed black freedom and laid the foundation for racial slavery. Virginia passed a law in 1680 prohibiting free blacks and slaves from bearing arms, banning blacks from congregating in large numbers, and establishing harsh punishments for slaves who assaulted Christians or attempted escape. Two years later, another Virginia law stipulated that all Africans brought to the colony would be enslaved people for life. Thus, the increasing reliance on slaves in the tobacco colonies—and the draconian laws instituted to control them—not only helped planters meet labor demands, but also served to assuage English fears of further uprisings and alleviate class tensions between rich and poor whites.

|

|

|

|

Robert Beverley was a wealthy Jamestown planter and slaveholder. This excerpt from his , published in 1705, clearly illustrates the contrast between white servants and black slaves. “Their Servants, they distinguish by the Names of Slaves for Life, and Servants for a time. Slaves are the Negroes, and their Posterity, following the condition of the Mother, according to the Maxim, partus sequitur ventrem [status follows the womb]. They are call’d Slaves, in respect of the time of their Servitude, because it is for Life. “Servants, are those which serve only for a few years, according to the time of their Indenture, or the Custom of the Country. The Custom of the Country takes place upon such as have no Indentures. The Law in this case is, that if such Servants be under Nineteen years of Age, they must be brought into Court, to have their Age adjudged; and from the Age they are judg’d to be of, they must serve until they reach four and twenty: But if they be adjudged upwards of “Nineteen, they are then only to be Servants for the term of five Years. “The Male-Servants, and Slaves of both Sexes, are employed together in Tilling and Manuring the Ground, in Sowing and Planting Tobacco, Corn, &c. Some Distinction indeed is made between them in their Cloaths, and Food; but the Work of both, is no other than what the Overseers, the Freemen, and the Planters themselves do. “Sufficient Distinction is also made between the Female-Servants, and Slaves; for a White Woman is rarely or never put to work in the Ground, if she be good for any thing else: And to Discourage all Planters from using any Women so, their Law imposes the heaviest Taxes upon Female Servants working in the Ground, while it suffers all other white Women to be absolutely exempted: Whereas on the other hand, it is a common thing to work a Woman Slave out of Doors; nor does the Law make any Distinction in her Taxes, whether her Work be Abroad, or at Home.” | |

PURITAN NEW ENGLAND

The second major area to be colonized by the English in the first half of the seventeenth century, New England, differed markedly in its founding principles from the commercially oriented Chesapeake tobacco colonies. Settled largely by waves of Puritan families in the 1630s, New England had a religious orientation from the start. In England, reform-minded men and women had been calling for greater changes to the English national church since the 1580s. These reformers, who followed the teachings of John Calvin and other Protestant reformers, were called Puritans because of their insistence on “purifying” the Church of England of what they believed to be un-scriptural, especially Catholic elements that lingered in its institutions and practices.

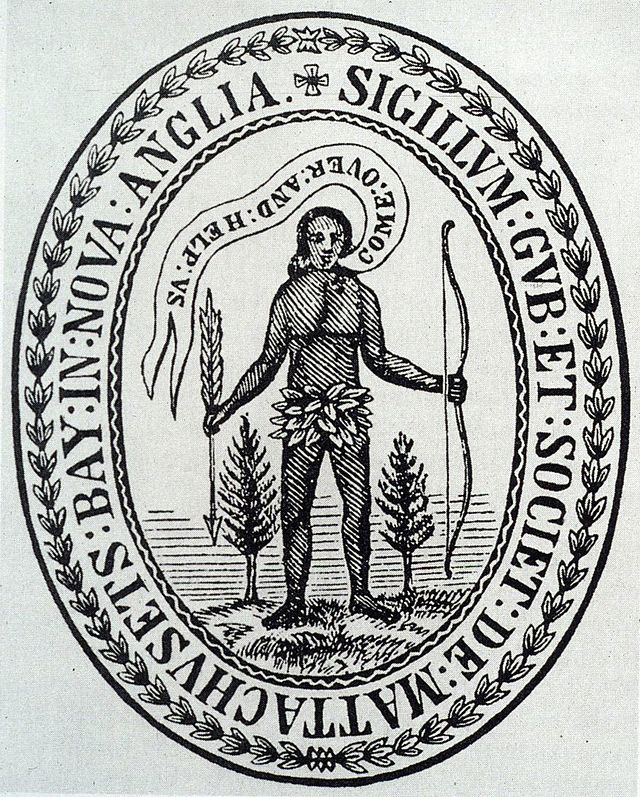

Many who provided leadership in early New England were learned ministers who had studied at Cambridge or Oxford but who, because they had questioned the practices of the Church of England, had been deprived of careers by the king and his officials in an effort to silence all dissenting voices. Other Puritan leaders, such as the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Winthrop, came from the privileged class of English gentry. These well-to-do Puritans and many thousands more left their English homes not to establish a land of religious freedom, but to practice their own religion without persecution. Puritan New England offered them the opportunity to live as they believed the Bible demanded. In their “New” England, they set out to create a model of reformed Protestantism, a new English Israel.

The conflict generated by Puritanism had divided English society, because the Puritans demanded reforms that undermined the traditional festive culture. For example, they denounced popular pastimes like bearbaiting—letting dogs attack a chained bear—which were often conducted on Sundays when people had a few leisure hours. In the culture where William Shakespeare had produced his masterpieces, Puritans called for an end to the theater, censuring playhouses as places of decadence. Indeed, the Bible itself became part of the struggle between Puritans and James I, who headed the Church of England. Soon after ascending the throne, James commissioned a new version of the Bible in an effort to stifle Puritan reliance on the Geneva Bible, which followed the teachings of John Calvin and placed God’s authority above the monarch’s. The King James Version, published in 1611, instead emphasized the majesty of kings.

During the 1620s and 1630s, the conflict escalated to the point where the state church prohibited Puritan ministers from preaching. In the Church’s view, Puritans represented a national security threat, because their demands for cultural, social, and religious reforms undermined the king’s authority. Unwilling to conform to the Church of England, many Puritans found refuge in the Americas.

P lymouth: The First Puritan Colony

The first group of Puritans to make their way across the Atlantic was a small contingent known as the Pilgrims who founded the Plymouth Colony in present-day Massachusetts in 1620. The governor of Plymouth, William Bradford, was a Separatist, a proponent of complete separation from the English state church. On board the Mayflower , which was bound for Virginia but landed on the tip of Cape Cod, Bradford and forty other adult men signed the Mayflower Compact, which presented a religious (rather than an economic) rationale for colonization. The compact expressed a community ideal of working together. When a larger exodus of Puritans established the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 1630s, the Pilgrims at Plymouth welcomed them, and the two colonies cooperated with each other.

Different labor systems also distinguished early Puritan New England from the Chesapeake colonies. Puritans expected young people to work diligently at their calling, and all members of their large families, including children, did the bulk of the work necessary to run homes, farms, and businesses. Very few migrants came to New England as laborers; in fact, New England towns protected their disciplined homegrown workforce by refusing to allow outsiders in, assuring their sons and daughters of steady employment. New England’s labor system produced remarkable results, notably a powerful maritime based economy with scores of oceangoing ships and the crews necessary to sail them. New England mariners sailing New England–made ships transported Virginian tobacco and West Indian sugar throughout the Atlantic World.

I n the 1629 seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, an Indian is shown asking colonists to “Come over and help us.” Source: Wikimedia Commons

“A City upon a Hill”

A much larger group of English Puritans left England in the 1630s, establishing the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the New Haven Colony, the Connecticut Colony, and Rhode Island. Unlike the exodus of young males to the Chesapeake colonies, these migrants were families with young children and their university trained ministers. Their aim, according to John Winthrop, the first governor of Massachusetts Bay, was to create a model of reformed Protestantism—a “city upon a hill,” a new English Israel.

Puritan New England differed in many ways from both England and the rest of Europe. Protestants emphasized literacy so that everyone could read the Bible. This attitude was in stark contrast to that of Catholics, who refused to tolerate private ownership of Bibles in the vernacular. The Puritans, for their part, placed a special emphasis on reading scripture, and their commitment to literacy led to the establishment of the first printing press in English America in 1636. Four years later, in 1640, they published the first book in North America, the Bay Psalm Book. As Calvinists, Puritans adhered to the doctrine of predestination, whereby a few “elect” would be saved and all others damned. No one could be sure whether they were predestined for salvation, but through introspection, guided by scripture, Puritans hoped to find a glimmer of redemptive grace. Church membership was restricted to those Puritans who were willing to provide a conversion narrative telling how they came to understand their spiritual estate by hearing sermons and studying the Bible.

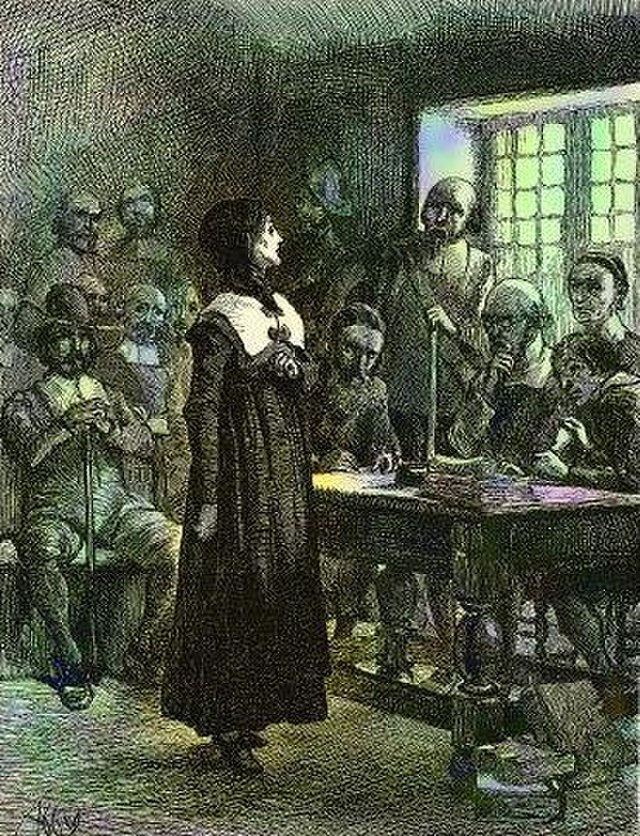

Although many people assume Puritans escaped England to establish religious freedom, they proved to be just as intolerant as the English state church. When dissenters, including Puritan minister Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson, challenged Governor Winthrop in Massachusetts Bay in the 1630s, they were banished. Roger Williams questioned the Puritans’ taking of Indian land. Williams also argued for a complete separation from the Church of England, a position other Puritans in Massachusetts rejected, as well as the idea that the state could not punish individuals for their beliefs. Although he did accept that nonbelievers were destined for eternal damnation, Williams did not think the state could compel true orthodoxy. Puritan authorities found him guilty of spreading dangerous ideas, but he went on to found Rhode Island as a colony that sheltered dissenting Puritans from their brethren in Massachusetts. In Rhode Island, Williams wrote favorably about native peoples, contrasting their virtues with Puritan New England’s intolerance.

Anne Hutchinson also ran afoul of Puritan authorities for her criticism of the evolving religious practices in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In particular, she held that Puritan ministers in New England taught a shallow version of Protestantism emphasizing hierarchy and actions—a “covenant of works” rather than a “covenant of grace.” Literate Puritan women like Hutchinson presented a challenge to the male ministers’ authority. Indeed, her major offense was her claim of direct religious revelation, a type of spiritual experience that negated the role of ministers. Because of Hutchinson’s beliefs and her defiance of authority in the colony, especially that of Governor Winthrop, Puritan authorities tried and convicted her of holding false beliefs. In 1638, she was excommunicated and banished from the colony. She went to Rhode Island and later, in 1642, sought safety among the Dutch in New Netherland. The following year, Algonquian warriors killed Hutchinson and her family. In Massachusetts, Governor Winthrop noted her death as the righteous judgment of God against a heretic.

In this pencil drawing by an unknown artist, Anne Hutchinson defends herself before the tribunal of Puritan judges. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Like many other Europeans, the Puritans believed in the supernatural. Every event appeared to be a sign of God’s mercy or judgment, and people believed that witches allied themselves with the Devil to carry out evil deeds and deliberate harm such as the sickness or death of children, the loss of cattle, and other catastrophes. Hundreds were accused of witchcraft in Puritan New England, including townspeople whose habits or appearance bothered their neighbors or who appeared threatening for any reason. Women, seen as more susceptible to the Devil because of their supposedly weaker constitutions, made up the vast majority of suspects and those who were executed. The most notorious cases occurred in Salem Village in 1692. Many of the accusers who prosecuted the suspected witches had been traumatized by the Indian wars on the frontier and by unprecedented political and cultural changes in New England. Relying on their belief in witchcraft to help make sense of their changing world, Puritan authorities executed nineteen people and caused the deaths of several others.

Puritan Relationships with Native Peoples

Like their Spanish and French Catholic rivals, English Puritans in America took steps to convert native peoples to their version of Christianity. John Eliot, the leading Puritan missionary in New England, urged natives in Massachusetts to live in “praying towns” established by English authorities for converted Indians, and to adopt the Puritan emphasis on the centrality of the Bible. In keeping with the Protestant emphasis on reading scripture, he translated the Bible into the local Algonquian language and published his work in 1663. Eliot hoped that as a result of his efforts, some of New England’s native inhabitants would become preachers.

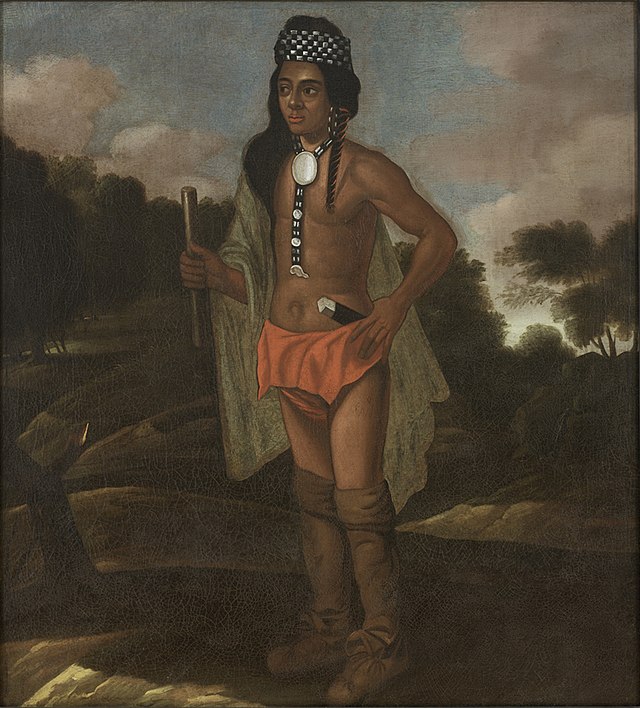

Tensions had existed from the beginning between the Puritans and the native people who controlled southern New England. Relationships deteriorated as the Puritans continued to expand their settlements aggressively and as European ways increasingly disrupted native life. These strains led to King Philip’s War (1675–1676), a massive regional conflict that was nearly successful in pushing the English out of New England.

When the Puritans began to arrive in the 1620s and 1630s, local Algonquian peoples had viewed them as potential allies in the conflicts already simmering between rival native groups. In 1621, the Wampanoag, led by Massasoit, concluded a peace treaty with the Pilgrims at Plymouth. In the 1630s, the Puritans in Massachusetts and Plymouth allied themselves with the Narragansett and Mohegan people against the Pequot, who had recently expanded their claims into southern New England. In May 1637, the Puritans attacked a large group of several hundred Pequot along the Mystic River in Connecticut. To the horror of their native allies, the Puritans massacred all but a handful of the men, women, and children they found.

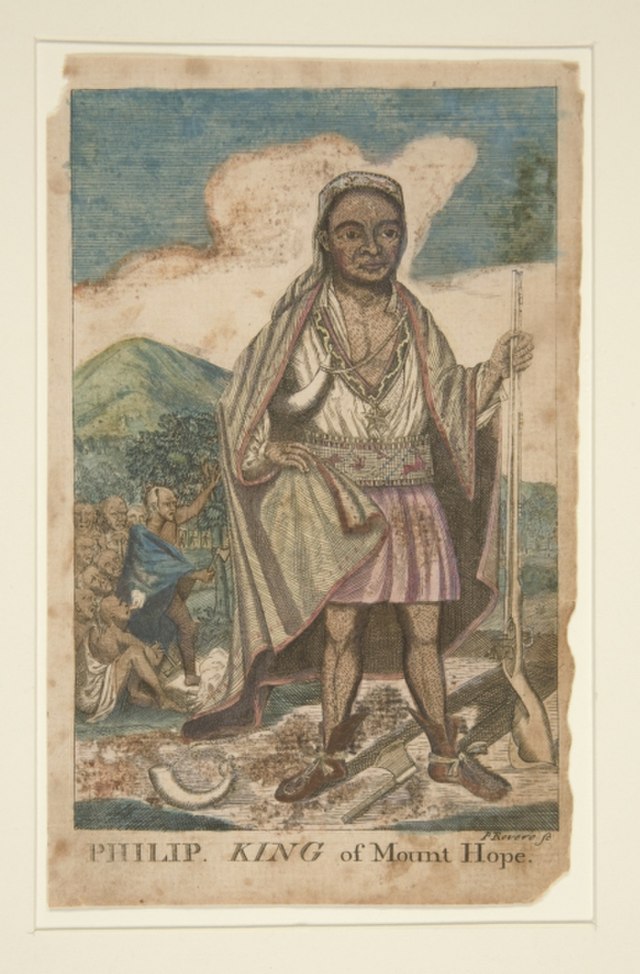

By the mid-seventeenth century, the Puritans had pushed their way further into the interior of New England, establishing outposts along the Connecticut River Valley. There seemed no end to their expansion. Wampanoag leader Metacom or Metacomet, also known as King Philip among the English, was determined to stop the encroachment. The Wampanoag, along with the Nipmuck, Pocumtuck, and Narragansett, took up the hatchet to drive the English from the land. In the ensuing conflict, called King Philip’s War, native forces succeeded in destroying half of the frontier Puritan towns; however, in the end, the English (aided by Mohegans and Christian Indians) prevailed and sold many captives into slavery in the West Indies. (The severed head of King Philip was publicly displayed in Plymouth.) The war also forever changed the English perception of native peoples; from then on, Puritan writers took great pains to vilify the natives as bloodthirsty savages. A new type of racial hatred became a defining feature of Indian-English relationships in the Northeast.

This line engraving by Paul Revere depicts King Philip (Metacom). Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE CAROLINAS

In 1633, English plantation owners from the tiny Caribbean island of Barbados, already a well-established English sugar colony fueled by slave labor, migrated to the southern part of Carolina to settle there. In 1670, they established Charles Town (later Charleston), named in honor of King Charles II, at the junction of the Ashley and Cooper Rivers. As the settlement around Charles Town grew, it began to produce livestock for export to the West Indies. In the northern part of Carolina, settlers turned sap from pine trees into turpentine used to waterproof wooden ships. Political disagreements between settlers in the northern and southern parts of Carolina escalated in the 1710s through the 1720s and led to the creation, in 1729, of two colonies, North and South Carolina. Because these colonies were established after the restoration of King Charles II to the Throne of England, they are called the Restoration colonies . The southern part of Carolina had been producing rice and indigo (a plant that yields a dark blue dye used by English royalty) since the 1700s, and South Carolina continued to depend on these main crops.

North Carolina continued to produce items for ships, especially turpentine and tar, and its population increased as Virginians moved there to expand their tobacco holdings. Tobacco was the primary export of both Virginia and North Carolina, which also traded in deerskins and enslaved people from Africa. Slavery developed quickly in the Carolinas, largely because so many of the early migrants came from Barbados, where slavery was well established. By the end of the 1600s, a very wealthy class of rice planters who relied on enslaved people had attained dominance in the southern part of the Carolinas, especially around Charles Town. By 1715, South Carolina had a black majority because of the number of enslaved people in the colony. The legal basis for slavery was established in the early 1700s as the Carolinas began to pass slave laws based on the Barbados slave codes of the late 1600s. These laws reduced Africans to the status of property to be bought and sold as other commodities.

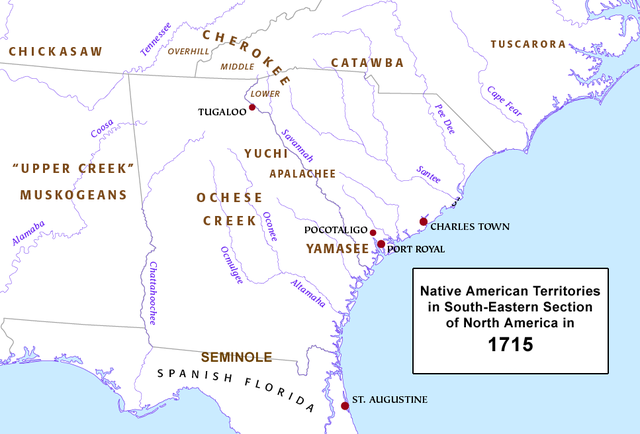

As in other areas of English settlement, native peoples in the Carolinas suffered tremendously from the introduction of European diseases. Despite the effects of disease, Indians in the area endured and, following the pattern elsewhere in the colonies, grew dependent on European goods. Local Yamasee and Creek tribes built up a trade deficit with the English, trading deerskins and captive slaves for European guns. English settlers exacerbated tensions with local Indian tribes, especially the Yamasee, by expanding their rice and tobacco fields into Indian lands. Worse still, English traders took native women captive as payment for debts.

The outrages committed by traders, combined with the seemingly unstoppable expansion of English settlement onto native land, led to the outbreak of the Yamasee War (1715–1718), an effort by a coalition of local tribes to drive away the European invaders. This native effort to force the newcomers back across the Atlantic nearly succeeded in annihilating the Carolina colonies. Only when the Cherokee allied themselves with the English did the coalition’s goal of eliminating the English from the region falter. The Yamasee War demonstrates the key role native peoples played in shaping the outcome of colonial struggles and, perhaps most important, the disunity that existed between different native groups.

NEW YORK AND NEW JERSEY

The English takeover of New Netherland originated in the imperial rivalry between the Dutch and the English. During the Anglo-Dutch wars of the 1650s and 1660s, the two powers attempted to gain commercial advantages in the Atlantic World. During the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1664–1667), English forces gained control of the Dutch fur trading colony of New Netherland, and in 1664, King Charles II gave this colony (including present-day New Jersey) to his brother James, Duke of York (later James II). The colony and city were renamed New York in his honor. The Dutch in New York chafed under English rule. In 1673, during the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–1674), the Dutch recaptured the colony. However, at the end of the conflict, the English had regained control.

“View of New Amsterdam” (ca. 1665), a watercolor by Johannes Vingboons, was painted during the Anglo-Dutch wars of the 1660s and 1670s. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Duke of York had no desire to govern locally or listen to the wishes of local colonists. It wasn’t until 1683, therefore, almost 20 years after the English took control of the colony, that colonists were able to convene a local representative legislature. The assembly’s 1683 Charter of Liberties and Privileges set out the traditional rights of Englishmen, like the right to trial by jury and the right to representative government.

Eighteenth-century New York City contained a variety of people and religions—as well as Dutch and English people, it held French Protestants (Huguenots), Jews, Puritans, Quakers, Anglicans, and a large population of enslaved people. As they did in other zones of colonization, native peoples played a key role in shaping the history of colonial New York. After decades of war in the 1600s, the powerful Five Nations of the Iroquois, composed of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca, successfully pursued a policy of neutrality with both the English and, to the north, the French in Canada during the first half of the 1700s. This native policy meant that the Iroquois continued to live in their own villages under their own government while enjoying the benefits of trade with both the French and the English.

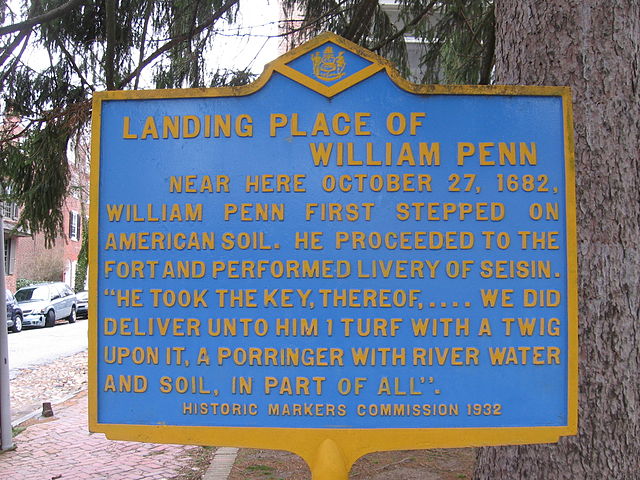

PENNSYLVANIA

Pennsylvania (which means “Penn’s Woods” in Latin) was created in 1681, when King Charles II bestowed the largest proprietary colony in the Americas on William Penn to settle the large debt he owed the Penn family. William Penn’s father, Admiral William Penn, had served the English crown by helping take Jamaica from the Spanish in 1655. The king personally owed the Admiral money as well.

King Charles II granted William Penn the land that eventually became the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in order to settle a debt the English crown owed to Penn’s father. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Like early settlers of the New England colonies, Pennsylvania’s first colonists migrated mostly for religious reasons. William Penn himself was a Quaker, a member of a new Protestant denomination called the Society of Friends. George Fox had founded the Society of Friends in England in the late 1640s, having grown dissatisfied with Puritanism and the idea of predestination. Rather, Fox and his followers stressed that everyone had an “inner light” inside him or her, a spark of divinity. They gained the name Quakers because they were said to quake when the inner light moved them. Quakers rejected the idea of worldly rank, believing instead in a new and radical form of social equality. Their speech reflected this belief in that they addressed all others as equals, using “thee” and “thou” rather than terms like “your lordship” or “my lady” that were customary for privileged individuals of the hereditary elite.

The English crown persecuted Quakers in England, and colonial governments were equally harsh; Massachusetts even executed several early Quakers who had gone to proselytize there. To avoid such persecution, Quakers and their families at first created a community on the sugar island of Barbados. Soon after its founding, however, Pennsylvania became the destination of choice. Quakers flocked to Pennsylvania as well as New Jersey, where they could preach and practice their religion in peace. Unlike New England, whose official religion was Puritanism, Pennsylvania did not establish an official church. Indeed, the colony allowed a degree of religious tolerance found nowhere else in English America. To help encourage immigration to his colony, Penn promised fifty acres of land to people who agreed to come to Pennsylvania and completed their term of service. Not surprisingly, those seeking a better life came in large numbers, so much so that Pennsylvania relied on indentured servants more than any other colony.

|

| |

|

The , published by William Bradford, was Philadelphia’s first newspaper. This advertisement from “John Wilson, ” (jailer) offers a reward for anyone capturing several men who escaped from the jail. : “John Palmer, also Plumly, Paine, American Mercury, Novem. 23, 1721. “Daniel Oughtopay, “Ebenezor Mallary, “Matthew Dulany, “John Flemming, “John Corbet, John Wilson, —Advertisement from the , 1722 | |