- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Meta-Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Research Methodology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Politics and Religion

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

41 Furthering the Science of Gratitude

Philip C. Watkins, Eastern Washington University, Cheney, Washington

Michael Van Gelder, Department of Psychology, Eastern Washington University.

Araceli Frias, Department of Psychology, Eastern Washington University.

- Published: 18 September 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In this chapter, we sought to strengthen the science of gratitude. We suggest effective approaches for studying gratitude, present a theoretical framework for researching gratitude, review recent gratitude research, and suggest directions and questions for future research, all in an attempt to encourage research on this important virtue. After presenting a brief historical background of gratitude, we define state and trait gratitude and describe several useful measurement tools. We review research that has examined traits that are associated with gratitude and show that grateful individuals have many salutary traits. We then overview research strategies that have been used to investigate gratitude and pay particular attention to successful experimental manipulations of gratitude. A number of studies have investigated the advantages of gratitude. Not only is gratitude strongly associated with happiness, but experimental studies have shown that gratitude actually enhances happiness. We propose several mechanisms whereby gratitude might enhance happiness. Gratitude may support happiness through enhancing enjoyment of benefits, relationships, self-esteem, and coping ability. Grateful processing of pleasant events may also enhance the accessibility of pleasant memories. Conversely, gratitude may support happiness by inhibiting envy and preventing depression. We conclude by presenting some concerns and prospects for the future of gratitude research. Continued understanding of this important emotion and virtue will do much to advance our understanding of the critical components of the good life.

Furthering the Science of Gratitude

Although gratitude is yet understudied, we will not bemoan its neglect here (see Solomon, 2004 ). Currently, there are only a few researchers who have devoted their research programs to gratitude, but recent texts and reviews have begun to give gratitude its just due (Emmons, 2007 ; Emmons & McCullough, 2004 ; McCullough, Kilpatrick, Emmons, & Larson, 2001 ; Watts, Dutton, & Guilford, 2006 ). The primary aim of this chapter is to further the science of gratitude. We will “stand on the shoulders” of previous excellent reviews (Emmons & Shelton, 2002 ; McCullough et al., 2001 ) to give the reader a current perspective of research in the field. To accomplish our goal, we will define gratitude and describe what we believe to be effective gratitude measurement techniques. We will then describe research methodologies that have been successful in furthering our knowledge of gratitude. Finally we will review research showing how gratitude is an important component of the good life.

What Is Gratitude?

Historical background.

Virtually every language has an equivalent for gratitude, and all major religions have encouraged expressions of gratitude (Emmons & Crumpler, 2000 ). Although expressing gratitude had its occasional detractors (e.g., Aristotle), these only serve as stark contrasts to how much humankind has valued giving thanks throughout history. In the United States, for example, gratitude has been institutionalized through its national Thanksgiving holiday. Moving Thanksgiving proclamations by Presidents Washington and Lincoln remind us of the importance that gratitude has held in the past. Expressions of gratitude may vary across the world, but gratitude appears to serve as a virtue in all cultures, and it is difficult to think of any societies that think of gratitude as a vice. Illustrating this point, some work has shown that people in the South Indian culture rarely express verbal thanks for a benefit but almost always express their gratitude with some kind of return favor (Appadurai, 1985 ). Some scholars have submitted that major moments in history have been essentially focused on gratitude. For example, Gerrish ( 1992 ) argued that the reformation theologies of Luther and Calvin were primarily Eucharistic—theologies that focused on grace and gratitude.

The history of the English words “grateful” and “thankful” is not only interesting but also informative. The “grate” that a person is full of when feeling grateful is derived from the Latin gratus which means thankful and pleasing (Ayto, 1990 ). All associations with gratus are positive, and research has confirmed that grateful emotion should be placed firmly within the positive affects (McCullough, Emmons, & Tsang, 2002 ; Watkins, Woodward, Stone, & Kolts, 2003 ) and the moral emotions (McCullough et al., 2001 ). “Grace” is also derived from gratus , and thus gratitude has close associations with unmerited favor. Although some research has indirectly investigated the association between grace and gratitude, in our view, more research should investigate this relationship. We propose that some of the most intense experiences of gratitude result from an experience of grace.

“Thank” has an even longer history in English than does grateful, originating before the twelfth century (Ayto, 1990 ). The word is derived from “thoughtfulness,” which then evolved into “favorable thought.” Clearly, feeling grateful involves “favorable thought” toward one's benefactor, and because gratitude involves thoughtfulness about the benefits one receives from others, some have argued that gratitude is essentially an empathic emotion (Lazarus & Lazarus, 1994 ). How accurately must a beneficiary understand the state of mind of his or her benefactor in order to feel grateful? This would be an interesting question for future research.

Defining State Gratitude

In order for a science of gratitude to proceed we must have a clear definition and means of measuring the construct. We offer the following definition: An individual experiences the emotion of gratitude (i.e., state gratitude) when they affirm that something good has happened to them when and they recognize that someone else is largely responsible for this benefit (derived from Emmons, 2004 ). In our definition, “someone else” could be a supernatural force as well as human benefactors. The perceived benefit may be the awareness of the absence of some negative event (e.g., when your plane lands safely in the midst of a severe lightning storm). Although people may feel grateful toward impersonal forces and objects (e.g., “I feel so grateful that fate was with me on that plane trip”), we submit that in these cases people are implicitly appraising intentional benevolence on the part of the impersonal benefactor. An interesting avenue of research would be to investigate experiences of gratitude when no obvious human benefactor is evident (Watkins, Gibler, Mathews, & Kolts, 2005 ).

Following Adam Smith ( 1790/1976 ), McCullough and colleagues ( 2001 ) have argued convincingly that gratitude may be seen as a moral affect. They proposed that gratitude serves as a “moral barometer” (it tells the beneficiary that the moral climate has changed in her favor—someone has benefited her), a “moral motivator” (it encourages prosocial behavior), and a “moral reinforcer” (when someone expresses gratitude, it encourages their benefactors to act favorably toward them in the future). This approach has provided researchers with a useful organization of previous gratitude research findings, as well as providing direction for future work.

How can one assess the emotion of gratitude? It appears that a simple but effective way of measuring the state of gratitude is having individuals respond to three adjectives (grateful, thankful, and appreciative; McCullough et al., 2002 ). Here individuals simply indicate their extent of feeling for these descriptors on a Likert-type scale ranging from not at all “to extremely.” In measuring grateful affect, one question that arises is whether one should direct the queries toward the benefit and/or benefactor. In this regard, we recommend investigators consider carefully whether their research demands a more general assessment of grateful affect (i.e., “how grateful do you feel?”), or whether the queries should be directed toward gratitude for the benefit and/or benefactor (“how grateful do you feel about …?”, “how grateful do you feel toward …?”).

Grateful emotion clearly covaries with other positive emotions (Watkins, Scheer, Ovnicek, & Kolts, 2006 ). Although feeling thankful is sometimes negatively associated with negative affect, several studies have shown that state gratitude correlates more strongly with positive affect (McCullough et al., 2002 ; Watkins, Woodward et al., 2003 ). Some have proposed that gratitude should be related to aesthetic emotions such as awe (e.g., Keltner & Haidt, 2003 ), and we have found some support for this idea (Watkins, Gibler et al., 2005 ). In this study, participants either viewed photographs of beautiful nature scenes or pictures of neutral objects. Participants viewing the nature scenes were randomly assigned to judge the beauty of the scene or the geographic location. We found that gratitude was most enhanced in the beauty appreciation condition.

When considering the construct of gratitude, it is important to discriminate gratitude from other emotional states. For example, many in the social sciences have assumed that gratitude was synonymous with indebtedness (feeling obligated to repay). However, several studies have now provided evidence that these should be viewed as distinct (but sometimes related) states. For example, in two studies, we were able to dissociate gratitude from indebtedness (Watkins, Scheer et al., 2006 ). We found that as the benefactor's expectations of reciprocity increased, gratitude in the beneficiary decreased, but indebtedness increased. In addition, the thought/action tendencies of gratitude were distinct from that of indebtedness.

Trait Gratitude

As with other emotions, when investigating gratitude, it is important to determine whether one is studying gratitude at the level of emotional state or affective trait (Rosenberg, 1998 ). Up to this point, we have described the emotional state of gratitude. However, it is also important to consider gratitude as an affective trait. Trait gratitude refers to one's disposition for gratitude. If an individual is high in trait gratitude, then they should experience gratitude more easily and more frequently than one who is not a grateful person. The disposition of gratitude more closely approximates what we mean when we discuss the virtue of gratitude.

To our knowledge, there are three well-developed measures of dispositional gratitude. McCullough et al. ( 2002 ) developed the GQ-6, a short (six items) but reliable measure of trait gratitude. It is quite clear to participants that the GQ-6 is tapping gratitude, so researchers who are concerned with issues of self-presentation may wish to use a more subtle measure, such as the GRAT appears to be (Watkins, Woodward et al., 2003 ). The GRAT is a longer measure that attempts to assess three lower-order characteristics of the grateful person. We have proposed (with some support) that grateful individuals should have a sense of abundance (or negatively, a lack of a sense of deprivation), a sense of simple appreciation (they appreciate the day-to-day pleasures available to most individuals), and an appreciation of others. Thus the GRAT focuses on these facets of trait gratitude. A third reliable gratitude measure that probably assesses gratitude at the trait level would be the gratitude subscale of the Values in Action scale (Peterson & Seligman, 2004 ). If one were interested in assessing gratitude in the context of other virtues, this scale would appear to be ideal. Both the GRAT and the GQ-6 appear to have excellent psychometrics, and more recently, we have developed a revised version of the GRAT (GRAT-R) and a shorter 16-item version, that offer several improvements over the original (Thomas & Watkins, 2003 ). One may also assess appreciation more generally (Adler & Fagley, 2005 ), but this factor does not appear to be distinct from dispositional gratitude (Wood, Maltby, Stewart, & Joseph, 2008 ).

Although these instruments appear to be effective measures of gratitude, they suffer from the same problems as all self-report measures, and with socially desirable traits such as gratitude, this could pose a significant problem for some research protocols. Thus, in some studies, informant reports (cf. McCullough et al., 2002 ) or behavioral markers of gratitude, such as verbal expressions of thanks or reciprocity behavior, may be preferred. The development of an implicit gratitude measure also would be a useful advance. In every case the researcher needs to determine her measurements carefully in the context of the purpose of the research.

Characteristics of Grateful People

What personality traits are most likely to describe a grateful (or an ungrateful) person? In a nutshell, gratitude appears to be a positive trait. Grateful individuals tend to be agreeable, emotionally stable, self-confident but less narcissistic, and non-materialistic (McComb, Watkins, & Kolts, 2004 ; McCullough et al., 2002 ; McLeod, Maleki, Elster, & Watkins, 2005 ; Watkins, Woodward et al., 2003 ). Given that major religions have discouraged narcissism and materialism, this raises the issue of the spirituality of grateful people, and indeed, gratitude does appear to be positively associated with spirituality. For example, grateful people have been found to show more intrinsic religious motivation, but less extrinsic religiosity (Watkins, Woodward et al., 2003 ). Grateful people say that religion is more important to them and also report that they attend more religious services, read the Scriptures more frequently, pray more, and report a closer relationship with God than less grateful individuals (McCullough et al., 2002 ). Because experiences of grace are often significant to religious individuals, it may be important to investigate the relationship of grace and gratitude in this context. Although there is considerable research on the salubrious effects of forgiving another (for a review, see Exline & Baumeister, 2000 ), very little research to date has investigated the impact of being forgiven by another. We submit that gratitude is likely to result from experiences of grace and forgiveness.

Although several studies have investigated the characteristics of grateful people, we have little, if any, data informing us as to how people come to be grateful. Many questions remain about relationships between gratitude and other personality traits. For example, are people grateful because they are agreeable, or does being a grateful person contribute to one's agreeableness? Perhaps even more profound questions arise out of the gratitude and religiosity associations. One would think that because most religions promote gratitude, the direction of causation would be from religiosity to gratitude. However, because positive affect enhances one's ability to see meaningful relationships and thus meaning in life (King, Hicks, Krull, & Del Gaiso, 2006 ), it is quite possible that gratitude enhances religiosity. In fact, it appears that intense experiences of gratitude were instrumental in the religious conversion of G. K. Chesterton ( 1908/1986 ):

Here I am only trying to describe the enormous emotions which cannot be described. And the strongest emotion was that life was as precious as it was puzzling.… The test of all happiness is gratitude; and I felt grateful, though I hardly knew to whom. Children are grateful when Santa Claus puts in their stockings gifts of toys or sweets. Could I not be grateful to Santa Claus when he put in my stockings the gift of two miraculous legs? We thank people for birthday presents of cigars and slippers. Can I thank no one for the birthday present of birth? (p. 258)

Future research investigating grateful experiences when no human benefactor is evident should produce intriguing results (cf. Watkins, Gibler et al., 2005 ).

Gratitude Research Methodologies

Virtually all of the studies discussed thus far are plagued by the problem associated with much positive psychology research: the use of correlational designs. More definitive knowledge would be gained about the causes and consequences of gratitude with experimental research. If we are to conduct experimental studies of gratitude, we must have techniques that reliably manipulate gratitude in the lab. Several researchers have used a “count your blessings” approach, where participants in the gratitude condition were encouraged to list several things they were thankful for. For example, in the first week or so of fall quarter we asked students in our gratitude condition to recall things they did over the summer that they were grateful for (study 3, Watkins, Woodward et al., 2003 ). These students reported more gratitude for their summer than students who listed things they wanted to do over the summer but couldn't. Emmons and McCullough ( 2003 ) asked their participants to list up to five blessings they were thankful for, and this also impacted their gratitude. Although the concern of Emmons and McCullough was more long-term impact of counting one's blessings, Dunn and Schweitzer ( 2005 ) successfully used a similar procedure to manipulate gratitude in the lab. They first asked their participants to list three to five things that made them most grateful. Participants were then asked to describe in detail the one situation that made them most grateful. This appears to be a low-cost manipulation that produces reliable changes in gratitude.

We have also asked participants to think about someone they were grateful for, and this produced reliable effects on positive affect (study 4, Watkins, Woodward et al., 2003 ). Somewhat surprisingly, people who “thought” about their benefactor showed more enhanced positive affect than those who “wrote” about their benefactor. This raises the important issue of how one might best cognitively process their blessings or benefactor to enhance gratitude. For example, simply listing as many blessings as possible may not create the kind of cognitive processing that maximizes gratitude. Similarly, recent data from Lyubomirsky's lab (Lyubomirsky, Sousa, & Dickerhoof, 2006 ) suggest that thinking about a positive event in a reliving—repetitive—manner enhanced emotional well-being more than writing or thinking analytically about positive events. Can one overanalyze a grateful event? Lyubomirsky's studies (see chap. 63 ) suggest that analytic thinking might be detrimental to gratitude, and this has important implications for gratitude interventions.

Finally, several researchers have attempted to manipulate gratitude by having a confederate provide the participant with some benefit (e.g., Tsang, 2006 ). For example, Bartlett and DeSteno ( 2006 ) had participants complete a tedious task, only to find out that the computer had malfunctioned and the participant would have to start over. However, a confederate discovers the problem (they simply plug in the computer monitor), and the participant is allowed to continue without wasting their previous work. Not surprisingly, this manipulation produced significant gratitude toward the confederate. Other approaches such as vignettes (e.g., Watkins, Scheer et al., 2006 ) and qualitative studies of gratitude exemplars should also provide advances in our understanding of gratitude.

The Good of Gratitude

In this recent wave of gratitude research, investigators have operated from the premise that gratitude was important to the good life. Most of this research was focused on the potential of gratitude to enhance happiness. Hence, early research asked the question, “Are grateful people happy people?” Correlations of trait gratitude with emotional well-being confirmed that grateful people do tend to be happy people. Both the GQ-6 and the GRAT show moderate to strong relationships with happiness measures (McCullough et al., 2002 ; Watkins, Woodward et al., 2003 ). Furthermore, Park, Peterson, and Seligman ( 2004 ) found that of the 24 Values in Action strengths, gratitude fell behind only hope and zest in predicting subjective well-being. More recently, we have found that trait gratitude predicts increased happiness 1 month later (Spangler, Webber, Xiong, & Watkins, 2008 ).

It has been known that personality traits are much stronger predictors of happiness than demographic variables (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999 ). Thus, several studies have compared trait gratitude with other well-known personality predictors of happiness (McComb et al., 2004 ; McCullough et al., 2002 ; Wood, Joseph, & Maltby, 2008 ). In each case, gratitude predicted happiness above and beyond Big Five traits, and gratitude was shown to be the strongest trait predictor of happiness. This pattern of results appears to hold not only with self-report measures, but with informant reports as well (McCullough et al., 2002 ). Although the relationship between gratitude and subjective well-being seems clear, one remaining question revolves around the source of one's gratitude. Watts et al. ( 2006 ) ask whether to whom one is grateful should make a difference in one's happiness. To our knowledge, this question has yet to be resolved.

Although these results provide support for the theory that gratitude enhances happiness, the correlational nature of these studies leaves the question of causation open. It is quite possible that gratitude is simply the happy consequence of being happy or that both happiness and gratitude result from a third variable such as reward sensitivity. Fortunately, several experimental studies have added credence to the idea that gratitude actually causes happiness. In two studies, we found that gratitude manipulations enhanced mood state (studies 3 and 4, Watkins, Woodward et al., 2003 ). In three studies, Emmons and McCullough ( 2003 ) found that a simple practice of counting one's blessings enhanced several subjective well-being measures compared to control conditions. Froh and colleagues found that this intervention was also effective with adolescents (Froh, Sefick, & Emmons, 2008 ). Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, and Schkade ( 2005 ) replicated these results with one important caveat. They found that more is not necessarily better when it comes to counting your blessings. Individuals who counted their blessings once a week showed more improvement in life satisfaction than did those who engaged in this practice three times per week. Many questions remain as to the most productive ways to utilize gratitude exercises, and the effectiveness of gratitude interventions is likely to be moderated by individual differences as well.

Perhaps one of the most powerful gratitude interventions to date is the treatment investigated by Seligman, Steen, Park, and Peterson ( 2005 ). In this exercise, individuals wrote a letter of gratitude to a person they felt had benefited them but whom they had “not properly thanked” (p. 416). They then delivered the letter to their benefactor. This intervention resulted in strong increases in happiness and decreases in depression compared to the placebo condition. In fact, the immediate impact of this intervention appeared to be superior to other positive psychology interventions. Although significant treatment gains were maintained 1 month post-intervention, by 6 months, happiness and depression scores had returned to baseline. While the temporality of this gratitude intervention might seem discouraging, we believe this result should be expected, and we will comment further on this issue later in this chapter.

In sum, both correlational and experimental results support the proposition that gratitude enhances the good life. Thus, it does not appear that gratitude is simply an epiphenomenon of happiness. However, positive affect research would lead us to believe that feeling good should increase the likelihood of feeling grateful. When individuals are happy, they are better able to notice and remember good things in their environment (e.g., Isen, Shalker, Clark, & Karp, 1978 ) and are more likely to attribute good intentions to their benefactors (Isen, Niedenthal, & Cantor, 1992 ). Gratitude research suggests that both of these factors should enhance the experience of gratitude (McCullough et al., 2001 ). However, the experimental research reviewed previously suggests that gratitude also enhances happiness. Perhaps then, happiness enhances gratitude, but gratitude in turn enhances happiness, resulting in a “cycle of virtue” (Watkins, 2004 ). Future investigations of this upward spiral would benefit our understanding of gratitude and the good life.

We would now like to suggest several mechanisms that help explain how gratitude contributes to happiness. First, we propose that gratitude directly enhances positive affect. We submit that gratitude enhances one's enjoyment of benefits. Chesterton observed, “gratitude produced … the most purely joyful moments that have been known to man” (1924/1989, p. 78). His reasoning was, “All goods look better when they look like gifts.” Is a benefit experienced more positively when it is accepted as a gift? To our knowledge, this question has not been directly investigated, but various studies show that one is more likely to feel grateful when one thinks that a benefit was intentionally given for one's well-being (McCullough et al., 2001 ). C. S. Lewis ( 1958 ) also argued that the expression of gratitude (or praise) enhanced one's enjoyment of a benefit:

I think we delight to praise what we enjoy because the praise not merely expresses but completes the enjoyment; it is its appointed consummation. It is not out of compliment that lovers keep on telling one another how beautiful they are; the delight is incomplete until it is expressed. (p. 95)

Experimental work reviewed previously tends to indirectly support Lewis's proposition, but we believe that research could more specifically target Lewis's theory here. It is also likely that individual differences play a role. Although it may be true that most people would enjoy a benefit if it is a gift rather than a simple good, those who tend to easily feel indebted actually may enjoy a gift less than a mere benefit.

Gratitude may also directly benefit mood by directing one's focus to good things that one has and away from things they lack, thus preventing unpleasant emotional states involved with upward social comparison and envy. Trait envy and materialism are negatively associated with trait gratitude (McCullough et al., 2002 ). However, more research needs to directly address the issue of whether gratitude actually tends to direct one's attention to benefits they have and away from benefits they lack.

Gratitude could also promote happiness by enhancing one's social relationships. It appears that one of the most reliable predictors of happiness is stable social relationships (Diener et al., 1999 ). Thus, if gratitude supports quality relationships, it should support happiness as well. Informants see grateful people as more likable (Watkins, Martin, & Faulkner, 2003 ); grateful expressions engender more social reward (McCullough et al., 2001 ). Some have proposed that gratitude should enhance social bonding (Fredrickson, 2004 ), and recent evidence has emerged to support this theory (Algoe, Haidt, & Gable, 2008 ). Furthermore, several experiments have shown that gratitude promotes prosocial behavior. We found that gratitude is associated with prosocial action tendencies, while inhibiting antisocial urges (Watkins, Scheer et al., 2006 ). In two studies Bartlett and DeSteno ( 2006 ) found that gratitude inductions enhanced an individual's likelihood to engage in prosocial behavior toward a benefactor or a stranger. What is notable about these studies is that gratitude increased helping efforts even when the task was unpleasant. Furthermore, they showed that gratitude was more likely to increase helping than another positive affect: amusement (see also Tsang, 2006 ). In a series of studies, Dunn and Schweitzer ( 2005 ) showed that experimental inductions of gratitude enhanced trust. Because trust is an important quality in healthy relationships, we believe this finding has implications for how gratitude might enhance happiness through supportive relationships. Thus, gratitude may enhance happiness because it is a prosocial trait.

It is also possible that gratitude may support happiness by enhancing adaptive coping. By focusing on positive consequences resulting from a difficult experience that one may be grateful for, one may be able to make sense of stressful events. Several studies have shown that grateful people report more adaptive coping techniques (e.g., Neal, Watkins, & Kolts, 2005 ), and other studies have found that grateful individuals report less posttraumatic symptoms following a trauma than less grateful people (e.g., Kashdan, Uswatte, & Julian, 2006 ). Gratitude for God also appears to be a buffer for the impact of stress on illness in elders (Krause, 2006 ). Moreover, the unpleasantness of negative memories tends to fade faster for grateful than for less grateful individuals (Watkins, Grimm, & Kolts, 2004 ). This evidence is largely descriptive, but recently we found in an experimental design that grateful processing of troubling memories helps bring closure, decrease the unpleasant impact, and decrease the intrusiveness of these recollections (Watkins, Cruz, Holben, & Kolts, 2008 ).

Finally, we propose that gratitude has a beneficial effect on subjective well-being by increasing the accessibility of positive memories. C. S. Lewis ( 1996 , p. 73) wrote, “A pleasure is only full grown when it is remembered.” A multitude of positive events from one's past would not be likely to benefit one's subjective well-being unless one were able to easily recollect these events. In fact, several studies have found that happy people are more able to recall pleasant events from their past (e.g., Seidlitz & Diener, 1993 ). Memory processes should be important to gratitude as well. We propose that encoding and reflecting on pleasant events with gratitude should enhance a positive memory bias, which in turn should support one's happiness. Watkins ( 2004 ) has provided an information processing rationale for this hypothesis, and some evidence supports this idea. In several studies, we have found that gratitude is associated with a positive memory bias (Watkins, Gilber et al., 2005 ). Not only are grateful individuals able to recollect more pleasant events than their less grateful counterparts, recollecting both positive and negative memories has a more positive emotional impact on grateful than less grateful people. Recently, we have found that trait gratitude predicts positive memory bias 1 month later, and this relationship was found to be independent of depression, positive affect, and happiness (Watkins, Van Gelder, & Maleki, 2006 ). Although these results are promising, experimental work would more directly address our notion that grateful processing enhances the accessibility of positive memories. In sum, grateful people appear to reflect more favorably on their past, and easily retrievable positive memories should enhance one's emotional well-being. If gratitude actually enhances a positive memory bias, gratitude may also support happiness by mitigating depression (Wood, Maltby, Gillett, Linley, & Joseph, 2008 ). Depression is associated with a negativistic memory bias, and having a ready collection of positive memories may help reverse the mood and memory vicious cycle in depression (Watkins, Grimm, Whitney, & Brown, 2005 ). Although these initial results are promising, many questions remain as to whether gratitude actually enhances the accessibility of positive memories, and if so, how gratitude might produce this bias.

Conclusions

Although much work remains to be done, it seems clear that gratitude is an important component of the good life. “I would maintain that thanks are the highest form of thought”; wrote Chesterton ( 1917 , The Age of the Crusades , para. 2), “and that gratitude is happiness doubled by wonder.” Not only is gratitude strongly associated with happiness, experimental manipulations of gratitude have enhanced emotional well-being. However, as pointed out previously, the impact of gratitude interventions appears to be somewhat transitory. We would not expect one gratitude visit to permanently increase one's happiness, and it is impressive to us that this gratitude intervention still shows significant effects on happiness 1 month later. One exercise of counting one's blessings or one gratitude visit is not likely to impact long-term happiness. Rather, we submit that it should be a more regular practice of gratitude that will result in long-range increases in happiness. How “regular” these exercises need to be probably depends on the person and the type of gratitude practice one engages in, and this should be the focus of future research. However, Lyubomirsky et al.'s work ( 2005 ) reminds us that more is not necessarily better when it comes to practices of gratitude. This raises the question of whether one can actually practice their way into being a more grateful person. We believe that the trait of gratitude can be enhanced, but this hope must be tested by future research. In this regard, we are also concerned that gratitude may be pursued in an extrinsic or instrumental fashion. For example, if an individual expresses gratitude only to feel better, might this approach backfire? Although gratitude clearly has social benefits, there is some research suggesting that those benefits will not be achieved if it is suspected that the person expressing gratitude is only doing so to receive more benefits (Carey, Clicque, Leighton, & Milton, 1976 ). Analogously, although gratitude has emotional benefits, we submit that if one focuses on those benefits, these emotional benefits will be mitigated. Authentic gratitude is an other-focused emotion and as such entails focus on the giver, not on one's own emotional condition.

Through this chapter, we hope to encourage more gratitude research. To accomplish this aim, we have described the construct of gratitude, the measurement of gratitude, and fruitful research methods for investigating gratitude. We have presented research supporting the importance of this construct, namely because gratitude appears to be important to the good life. We have also attempted to provide a theoretical framework for investigating the gratitude/happiness relationship. Hopefully this will encourage more to embark on gratitude research and further advancement will be seen. Henry Ward Beecher (n.d., para. 1) concluded, “Gratitude is the fairest blossom which springs from the soul.” We hope that through this chapter we have planted seeds that will yield a harvest of research furthering our understanding of gratitude.

Three Questions for Future Gratitude Research

Can interventions be developed that enhance the trait of gratitude?

Why does gratitude enhance happiness?

How does the trait of gratitude develop in a person? How does a person become grateful?

Adler, M. G., & Fagley, N. S. ( 2005 ). Appreciation: Individual differences in finding value and meaning as a unique predictor of subjective well-being. Journal of Personality , 73 , 79–113.

Algoe, S. B., Haidt, J., & Gable, S. L. ( 2008 ). Beyond reciprocity: Gratitude and relationships in everyday life. Emotion , 8 , 425–429.

Appadurai, A. ( 1985 ). Gratitude as a social mode in south India. Ethos , 13 , 236–245.

Ayto, J. ( 1990 ). Dictionary of word origins . New York: Arcade.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Bartlett, M. Y., & DeSteno, D. ( 2006 ). Gratitude and prosocial behavior. Psychological Science , 17 , 319–325.

Beecher, H. W. (n.d.). Henry Ward Beecher . Retrieved July 28, 2006, from Wisdom Quotes, hppt://www.wisdomquotes.com/002943.html

Carey, J. R., Clicque, S. H., Leighton, B. A., & Milton, F. ( 1976 ). A test of positive reinforcement of customers. Journal of Marketing , 40 , 98–100.

Chesterton, G. K. ( 1908 /1986). Orthodoxy. In D. Dooley (Ed.), G. K. Chesterton: Collected works (pp. 209–366). San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

Chesterton, G. K. ( 1917 ). A short history of England . Retrieved July 28, 2006, from http://www.dur.ac.uk/martin.ward/gkc/books/history.txt

Chesterton, G. K. ( 1924 /1989). Saint Francis of Assisi . NewYork: Image Books/Doubleday.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. ( 1999 ). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin , 125 , 276–302.

Dunn, J. R., & Schweitzer, M. E. ( 2005 ). Feeling and believing: The influence of emotion on trust. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 88 , 736–748.

Emmons, R. A. ( 2004 , July). Gratitude is the best approach to life. In L. Sundarajan (Chair), Quest for the good life: Problems/promises of positive psychology . Symposium presented at the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Honolulu, HI.

Emmons, R. A. ( 2007 ). Thanks!: How the new science of gratitude can make you happier . New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Emmons, R. A., & Crumpler, C. A. ( 2000 ). Gratitude as human strength: Appraising the evidence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology , 19 , 56–69.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. ( 2003 ). Counting blessings versus burdens: An empirical investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 84 , 377–389.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. ( 2004 ). The psychology of gratitude . New York: Oxford University Press.

Emmons, R. A., & Shelton, C. ( 2002 ). Gratitude and the science of positive psychology. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 459–471). New York: Oxford University Press.

Exline, J. J., & Baumeister, R. F. ( 2000 ). Expressing forgiveness and repentance: Benefits and barriers. In M. E. McCollough, K. E. Pargament, & C. E. Thorsen (Eds.), Forgiveness: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 133–155). New York: Guilford.

Fredrickson, B. L. ( 2004 ). Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 145–166). New York: Oxford University Press.

Froh, J. J., Sefick, W. J., & Emmons, R. A. ( 2008 ). Counting blessings in early adolescents: An experimental study of gratitude and subjective well-being. Journal of School Psychology , 46 , 213–233.

Gerrish, B. A. ( 1992 ). Grace and gratitude: The Eucharistic theology of John Calvin . Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers.

Isen, A. M., Niedenthal, P. M., & Cantor, N. ( 1992 ). An influence of positive affect on social categorization. Motivation and Emotion , 16 , 65–78.

Isen, A. M., Shalker, T. E., Clark, M., & Karp, L. ( 1978 ). Affect, accessibility of material in memory, and behavior: A cognitive loop? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 36 , 1–12.

Kashdan, T. B., Uswatte, U., & Julian, T. ( 2006 ). Gratitude and eudaimonic well-being in Vietnam War veterans. Behaviour Research and Therapy , 44 , 177–199.

Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. ( 2003 ). Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition and Emotion , 17 , 297–314.

King, L. A., Hicks, J. A., Krull, J. L., & Del Gaiso, A. K. ( 2006 ). Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 90 , 179–196.

Krause, N. ( 2006 ). Gratitude toward God, stress, and health in late life. Research on Aging , 28 , 163–183.

Lazarus, R., & Lazarus, B. ( 1994 ). Passion and reason . NewYork: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, C. S. ( 1958 ). Reflections on the Psalms . New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.

Lewis, C. S. ( 1996 ). Out of the silent planet . New York: Scribner Paperback Fiction.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. ( 2005 ). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology , 9 , 111–131.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sousa, L., & Dickerhoof, R ( 2006 ). The costs and benefits of writing, talking, and thinking about life's triumphs and defeats. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 90 , 692–708.

McComb, D., Watkins, P., & Kolts, R. (2004, May). Personality predictors of happiness: The importance of gratitude . Presentation to the 84th Annual Convention of the Western Psychological Association, Phoenix, AZ.

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. ( 2002 ). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 82 , 112–127.

McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. ( 2001 ). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin , 127 , 249–266.

McLeod, L., Maleki, L., Elster, B., & Watkins, P. (2005, April). Does narcissism inhibit gratitude? Presentation to the 85th Annual Convention of the Western Psychological Association, Portland, OR.

Neal, M., Watkins, P. C., & Kolts, R. (2005, August). Does gratitude inhibit intrusive memories? Presentation to the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. ( 2004 ). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology , 23 , 603–619.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. ( 2004 ). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification . New York: American Psychological Association and Oxford University Press.

Rosenberg, E. ( 1998 ). Levels of analysis and the organization of affect. Review of General Psychology , 2 , 247–270.

Seidlitz, L., & Diener, E. ( 1993 ). Memory for positive versus negative life events: Theories for the differences between happy and unhappy persons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 64 , 654–664.

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. ( 2005 ). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist , 60 , 410–421.

Smith, A. (1790/ 1976 ). The theory of moral sentiments (6th ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Solomon, R. C. ( 2004 ). Foreword. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. v–xi). New York: Oxford University Press.

Spangler, K., Webber, A., Xiong, I., & Watkins, P. C. (2008, April). Gratitude predicts enhanced happiness . Presentation to the National Conference on Undergraduate Research, April, 2008, Salisbury, MD.

Thomas, M., & Watkins, P. (2003, May). Measuring the grateful trait: Development of the revised GRAT . Presentation to the 83rd Annual Convention of the Western Psychological Association, Vancouver, BC.

Tsang, J. ( 2006 ). Gratitude and prosocial behaviour: An experimental test of gratitude. Cognition and Emotion , 20 , 138–148.

Watkins, P. C. ( 2004 ). Gratitude and subjective well-being. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 167–192). New York: Oxford University Press.

Watkins, P. C., Cruz, L., Holben, H., & Kolts, R. L. ( 2008 ). Taking care of business? Grateful processing of unpleasant memories. Journal of Positive Psychology , 3 , 87–99.

Watkins, P. C., Gibler, A., Mathews, M., & Kolts, R. (2005, August). Aesthetic experience enhances gratitude . Paper presented to the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

Watkins, P. C., Grimm, D. L., & Kolts, R. ( 2004 ). Counting your blessings: Positive memories among grateful persons. Current Psychology , 23 , 52–67.

Watkins, P. C., Grimm, D. L., Whitney, A. , & Brown, A. ( 2005 ). Unintentional memory bias in depression. In A. V. Clark (Ed.), Mood state and health (pp. 59–86). Hauppage, NY: Nova Science.

Watkins, P. C., Martin, B. D., & Faulkner, G. (2003, May). Are grateful people happy people? Informant judgments of grateful acquaintances . Presentation to the 83rd Annual Convention of the Western Psychological Association, Vancouver, BC.

Watkins, P. C., Scheer, J., Ovnicek., M., & Kolts, R. D. ( 2006 ). The debt of gratitude: Dissociating gratitude and indebtedness. Cognition and Emotion , 20 , 217–241.

Watkins, P. C., Van Gelder, M., & Maleki, L. (2006, August). Counting (and recalling) blessings: Trait gratitude predicts positive memory bias . Presentation to the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, New Orleans, LA.

Watkins, P. C., Woodward, K., Stone, T., & Kolts, R. D. ( 2003 ). Gratitude and happiness: The development of a measure of gratitude and its relationship with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality , 31 , 431–452.

Watts, F., Dutton, K., & Guilford, L. ( 2006 ). Human spiritual qualities: Integrating psychology and religion. Mental Health, Religion and Culture , 9 , 277–289.

Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., & Maltby, J. ( 2008 ). Gratitude uniquely predicts satisfaction with life: Incremental validity above the domains and facets of the five factor model. Personality and Individual Differences , 45 , 49–54.

Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Gillett, R., Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. ( 2008 ). The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. Journal of Research in Personality , 42 , 854–871.

Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Stewart, N., & Joseph, S. ( 2008 ). Conceptualizing gratitude and appreciation as a unitary personality trait. Personality and Individual Differences , 44 , 621–632.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Reciprocal Relationship Between Gratitude and Life Satisfaction: Evidence From Two Longitudinal Field Studies

Wenceslao unanue, marcos esteban gomez mella, diego alejandro cortez, diego bravo, claudio araya-véliz, jesús unanue, anja van den broeck.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Edited by: Monika Fleischhauer, Medical School Berlin, Germany

Reviewed by: Jesus Alfonso Daep Datu, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; Philip Charles Watkins, Eastern Washington University, United States

*Correspondence: Wenceslao Unanue, [email protected]

This article was submitted to Personality and Social Psychology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Psychology

Received 2019 Jul 20; Accepted 2019 Oct 21; Collection date 2019.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

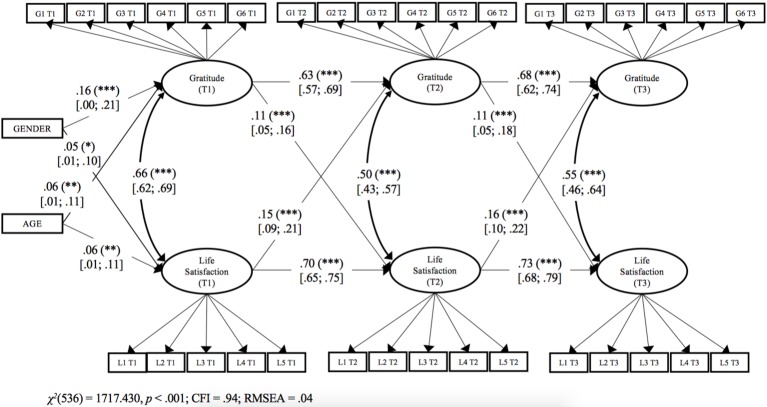

Gratitude and life satisfaction are associated with several indicators of a good life (e.g., health, pro-social behavior, and relationships). However, how gratitude and life satisfaction relate to each other over time has remained unknown until now. Although a substantial body of research has tested the link from gratitude to life satisfaction, the reverse association remains unexplored. In addition, recent cross-cultural research has questioned the link between gratitude and subjective well-being in non-Western countries, suggesting that the benefits of gratitude may only prevail in Western societies. However, previous cross-cultural studies have only compared western (e.g., American) and eastern (e.g., Asian) cultures, but this simple contrast does not adequately capture the diversity in the world. To guide further theory and practice, we therefore extended previous cross-sectional and experimental studies, by testing the bi-directional longitudinal link between gratitude and life satisfaction in a Latin American context, aiming to establish temporal precedence. We assessed two adult samples from Chile, using three-wave cross-lagged panel designs with 1 month (Study 1, N = 725) and 3 months (Study 2, N = 1,841) between waves. Both studies show, for the first time, that gratitude and life satisfaction mutually predict each other over time. The reciprocal relationships suggest the existence of a virtuous circle of human well-being: higher levels of gratitude increase life satisfaction, which in turn increases gratitude, leading to a positive spiral. Key theoretical and practical implications for the dynamics of human flourishing and field of positive psychology are discussed.

Keywords: gratitude, life satisfaction, subjective well-being, positive psychology, longitudinal analysis, prospective design, adults, Chile

Thanks to life, which has given me so much It gave me two stars, which when I open them, Perfectly distinguish black from white And in the tall sky its starry backdrop, And within the multitudes the one that I love. Thanks to life Violeta Parra, Chilean poet

Life satisfaction and gratitude are important for living a good life. The benefits of both constructs have been extensively documented. They include, for instance, better mental and physical health, more pro-social behavior, high-quality relationships, and more meaningful lives ( Wood et al., 2010 ; Diener and Tay, 2017 ). Life satisfaction ( Diener, 1984 ) is a key predictor of well-being ( Helliwell et al., 2013 ) and a fundamental construct for advising on public policies ( Diener et al., 2009 ): the OECD, e.g., has used life satisfaction to assess the progress of the nations through the Better Life Index ( OECD, n.d. ). Gratitude, a tendency to appreciate the good and positive, is an equally essential nutrient for people flourishing ( Wood et al., 2010 ).

Research has extensively shown a positive link between gratitude and life satisfaction ( Froh et al., 2009 ; Wood et al., 2010 ; Alkozei et al., 2018 ). However, how both constructs relate to each other over time has remained unknown until now. Previous studies have only explored the link from gratitude to life satisfaction, whereas the reverse association has not been tested yet. Drawing on Watkins (2004) seminal article, we theorized a reciprocal relationship between both constructs and thus a “circle of virtue”.

As gratitude and life satisfaction likely unfold over time, we need to do more to disentangle the ongoing, naturally occurring, reciprocal relations between pre-existing (rather than momentarily primed) gratitude and life satisfaction. Appropriate and well-suited longitudinal designs—still scarce in the field—are needed in order to complement the existing evidence and test whether both constructs are reciprocally related ( Wood et al., 2008 ). This paper presents two such studies, among Chilean adults, that could contribute in this area.

Studying the directionality between gratitude and life satisfaction is important, both from a theoretical and practical point of view. From a theoretical perspective, our studies make four main contributions. First, longitudinal field research is necessary for clarifying the direction of the link between gratitude and life satisfaction, in order to identify whether there is a temporal precedence between the constructs or whether the link is only due to a shared variance with other variables. Second, clarifying the prospective direction of the link between gratitude and life satisfaction allows their conceptualizations and implications to be enriched. If our reciprocal hypothesis is supported, gratitude would be not only an antecedent of life satisfaction but also a consequence of it and vice versa. These findings would show the complexity, multi-directionality, and interdependence between both constructs. Third, the potential influence of gratitude on subjective well-being (SWB; Diener, 1984 ) has not yet been fully confirmed in the non-Western world. Indeed, recent cross-cultural research has suggested that benefits of gratitude may only reach Western societies ( Boehm et al., 2011 ; Layous et al., 2013 ; Shin et al., in press ). However, previous studies have only compared Asian and American cultures. Therefore, we think it is important to extend gratitude research by including additional non-Western countries like Chile, which allows us to go beyond the traditional Western-Eastern dichotomy ( Vignoles et al., 2016 ). Fourth, while the great majority of previous studies have explored students and young populations ( Davis et al., 2016 ), we assessed working adults.

From a practical point of view, if the reciprocal relationship is supported, it would open the possibility for a virtuous or a vicious circle in health and well-being interventions. On the one hand, higher gratitude would lead to higher life satisfaction, which in turn would increase gratitude, leading to a positive spiral in human flourishing. On the other hand, the lack of either gratitude or life satisfaction may lead to a negative process in human wellness. Policy makers and health practitioners could benefit from these findings. By teaching people the importance of gratitude and life satisfaction—and how to foster each of them, practitioners from different settings (clinical, educational, organizational, etc.) may not only help people to protect their mental health but also show them how to move toward a virtuous circle of flourishing and well-being.