- Request new password

- Create a new account

Doing Research in Counselling and Psychotherapy

Student resources, carrying out a systematic case study.

The key messages of this chapter are:

- case study analysis makes a distinctive contribution to the evidence base for counselling and psychotherapy

- case studies are ethically sensitive, so need to be carried out with care and sensitivity

- it is important to be aware of how different types of research question require different case study approaches.

The following sources are intended to help you to explore issues covered in the chapter in more depth.

Methodological issues and challenges associated with case study research

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research . Qualitative Inquiry, 12 , 219 – 245.

Essential reading – a highly influential paper that clarifies the value of case study methods

Fishman, D. B. (2005). Editor's Introduction to PCSP--From single case to database: a new method for enhancing psychotherapy practice. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy, 1(1), 1 – 50.

The rationale for the pragmatic case study approach

Foster, L.H. (2010). A best kept secret: single-subject research design in counseling. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 1, 30 – 39

An accessible and informative introduction to n=1 single subject case study methodology

McLeod, J. (2013). Increasing the rigor of case study evidence in therapy research. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy, 9 , 382 – 402

Explores further possibilities around the development of case study methodology

Different types of therapy case study

Bloch-Elkouby, S., Eubanks, C. F., Knopf, L., Gorman, B. S., & Muran, J. C. (2019). The difficult task of assessing and interpreting treatment deterioration: an evidence-based case study. Frontiers in Psychology , 10, 1180.

Systematic case study that combines qualitative and quantitative information to explore a theoretically-significant case of apparent client deterioration. Case was drawn from dataset of a larger study

Brezinka, V., Mailänder, V., & Walitza, S. (2020). Obsessive compulsive disorder in very young children–a case series from a specialized outpatient clinic. BMC Psychiatry , 20(1), 1 – 8.

Example of how a series of n=1 case studies can be used

Faber, J., & Lee, E. (2020). Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for a refugee mother with depression and anxiety. Clinical Case Studies , 19(4), 239 – 257.

A hybrid theory-building/pragmatic case study that seeks to develop new understanding of therapy in situations of client-therapist cultural difference. Clinical Case Studies is a major source of case study evidence – this study is a typical example of the kind of work that it publishes

Gray, M.A. & Stiles, W.B. (2011). Employing a case study in building an Assimilation Theory account of Generalized Anxiety Disorder and its treatment with Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy , 7(4), 529 – 557

An example of a theory-building case study focused on the development of the assimilation model of change

Kramer, U. (2009). Between manualized treatments and principle-guided psychotherapy: illustration in the case of Caroline. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy , 5(2), 45 – 51

A pragmatic case study that also seeks to address important theoretical issues associated with the use of exposure techniques in CBT

McLeod, J. (2013). Transactional Analysis psychotherapy with a woman suffering from Multiple Sclerosis: a systematic case study. Transactional Analysis Journal, 43 , 212 – 223.

A hybrid case study – mainly aims to develop a theory of therapy in long-term health conditions, but also includes elements of pragmatic, narrative and HSCED approaches. Good example of the use of the Client Change Interview in case study research

Powell, M.L. and Newgent, R.A. (2010) Improving the empirical credibility of cinematherapy: a single-subject interrupted time-series design. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation , 1, 40 – 49.

Example of a series of n=1 case studies

Stige, S. H., & Halvorsen, M. S. (2018). From cumulative strain to available resources: a narrative case study of the potential effects of new trauma exposure on recovery. Illness, Crisis & Loss , 26(4), 270 – 292.

A narrative case study based on client interviews

Kellett, S., & Stockton, D. (2021). Treatment of obsessive morbid jealousy with cognitive analytic therapy: a mixed-methods quasi-experimental case study. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling , 1 – 19.

Example of an n=1 case study of a single case. Useful demonstration of how this approach can be used to study non-behavioural therapy

Wendt, D. C., & Gone, J. P. (2016). Integrating professional and indigenous therapies: An urban American Indian narrative clinical case study. The Counseling Psychologist , 44(5), 695 – 729.

A narrative case study based on client interviews

Werbart, A., Annevall, A., & Hillblom, J. (2019). Successful and less successful psychotherapies compared: three therapists and their six contrasting cases. Frontiers in Psychology . DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00816.

Combined narrative, theory-building and cross-case analysis, based on interviews with client and therapist dyads

Widdowson, M. (2012). TA treatment of depression: A hermeneutic single-case efficacy design study-case three: 'Tom'. International Journal of Transactional Analysis Research , 3(2), 15 – 27.

Example of an HSCED study that also includes elements of theory-building. Supplementary information on journal website includes full details of the Change Interview and judges’ case analyses. This open access journal has also published many other richly-described HSCED studies

Issues and possibilities associated with quasi-judicial methodology

Bohart, A.C., Tallman, K.L., Byock, G.and Mackrill, T. (2011). The “Research Jury” Method: The application of the jury trial model to evaluating the validity of descriptive and causal statements about psychotherapy process and outcome. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy, 7 (1) ,101 – 144.

Miller, R.B. (2011). Real Clinical Trials (RCT) – Panels of Psychological Inquiry for Transforming anecdotal data into clinical facts and validated judgments: introduction to a pilot test with the Case of “Anna”. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy, 7(1), 6 – 36.

Stephen, S. and Elliott, R. (2011). Developing the Adjudicated Case Study Method. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy, 7(1), 230 – 224.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

How to Write a Case Study

Note 1 : For illustrative purposes the below is written for a therapy comprised of a single individual in the therapist role and a single individual in the client role. If you are writing a case study about a couple, family, or group, perhaps with a co-therapist, the structure as described below is the same, there is just an expansion of the individuals in the client role and/or the therapist role.

Note 2 : Most of the case studies already published in PCSP have been written by the therapist in the case. However, an alternative is for others to join the therapist or for others alone to function as authors, using direct observations of the sessions, videotapes, transcripts, detailed clinical notes, and/or interviews with the therapist as the data for the case study. Two examples in PCSP of others joining the author to write the case study can be found at : https://pcsp.nationalregister.org/index.php/pcsp/article/view/936/2334 https://pcsp.nationalregister.org/index.php/pcsp/article/view/1915/3340

Note 3 : Almost all of the case studies already published in PCSP have been written about actual, although disguised, cases, and this is highly desirable. However, there have been instances in which for various reasons, such as special confidentiality concerns, a composite, hybrid case has been employed. Such an example can be found at: https://pcsp.nationalregister.org/index.php/pcsp/article/view/2112/3511

Note 4 : The below are guidelines -- not rigid rules -- for how to write a case study for PCSP.

CONCEPTUAL BACKGROUND OF A PRAGMATIC CASE STUDY IN PSYCHOTHERAPY

The Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy ( PCSP ) journal was founded in 2005 on a vision of publishing psychotherapy case studies that is centered in Donald Peterson’s (1991) disciplined inquiry model of best practice across applied psychology, including psychotherapy (also see Fishman, 2013).

In the Peterson model, the therapist begins with a focus on the Client and his or her presenting problems (component A). In this context, the therapist selects a general Guiding Conception (component B) with accompanying Clinical Experience and Research Support (component C). The therapist then conducts a comprehensive Assessment (component D), including history, personality, living situation, symptoms and other problems, diagnosis, and strengths. Applying the Guiding Conception to the Assessment data next yields an individualized Formulation and Treatment Plan (component E). The Case Formulation and Treatment Plan are thus a mini-version of the Guiding Conception as personalized for the individual client.

The Treatment Plan is implemented during the Course of Therapy (component F). This clinical process is consistently subjected to Therapy Monitoring (component G), generating feedback loops. If the therapy is not proceeding well possible changes in earlier steps (via component H) might be needed—e.g., reviewing the client’s characteristics and the “chemistry” between the Client and the therapist (component A); collecting more and/or reinterpreting the Assessment data (component D); and/or revising the Case Formulation and/or the Treatment Plan (component E).

If the Therapy Monitoring (component H) results in showing that the client has been successful and/or that the therapist and client agree that further therapy will not be productive, therapy is terminated and a Concluding Evaluation (component L) is conducted. This can yield feedback for either confirming—via assimilation—the original Guiding Conception (component J), or revising that theory through accommodation (component K).

The Narrative Nature of the Psychotherapy Case Study

Note that therapy involves the development of a highly emotionally and meaningful relationship and interactions over time between two persons, one in a therapist role providing help and one who in a client role receiving help. The resulting case study capturing these events should thus read in part like a richly detailed story about what happens when these two people meet.

Three Parts

As a summary, the therapy documented in Figure 1 proceeds in three parts:

(a) preparing for intervention (components A-E, headings 1-5);

(b) intervention (components F-I, headings 6 and 7); and

(c) outcome evaluation (components J-L, heading 8).

SPECIFIC GUIDELINES

In line with the above, PCSP is interested in manuscripts that describe the process and outcome of one or more clinical cases. Detailed description of the patient, presenting problem(s), conceptualization of the clinical challenges, and the course of treatment are necessary. PCSP expects a comprehensive presentation of all aspects of the case(s) reported, as reflected in headings 1-11 in Figure 1.

Note that deviations from the headings are allowed if they are conceptually based. An example is Shapiro’s (2023) case of “Keo,” in which sections 4, 5, and 6 are combined as they emerged from the initial contact with Keo because, in Shapiro’s words, “In the existential therapy model, the therapist approaches the client with a very open mind, not wanting to allow preconceptions to interfere with the process of relationship-building and the client telling their story in their own way.” ( https://pcsp.nationalregister.org/index.php/pcsp/article/view/2127/3524 , p. 5).

Each of the eight main sections in a PCSP case study is addressed below, followed by three guidelines that apply to all eight sections. 1. Case Context and Method

This section is a short introduction to the reader about you, your background and clinical experience, and how you approach your clinical work. This should be brief and factual. Typical items include:

(a) Who you are;

(b) How long have you practiced;

(c) In what settings with what populations have you worked;

(d) What training experiences and supervision have you had; and

(e) The way(s) in which you ensured confidentiality in your case study ( required ). This is typically done by disguising the client’s identity, in accordance with section 4.07 of the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct of the American Psychological Association:

4.07 Use of Confidential Information for Didactic or Other Purposes Psychologists do not disclose in their writings, lectures, or other public media, confidential, personally identifiable information concerning their clients/patients, students, research participants, organizational clients, or other recipients of their services that they obtained during the course of their work, unless (1) they take reasonable steps to disguise the person or organization, (2) the person or organization has consented in writing, or (3) there is legal authorization for doing so. ( https://www.apa.org/ethics/code ).

2. The Client

This section should consist of a concise description of the client with selected details. The goal is to introduce the reader to the client as a person so they can keep this image of the person in mind as the reader continues through the case study. Some details about the client can include:

(a) cultural status,

(c) gender,

(d) education/work background and status,

(e) marital status,

(f) parental status

(f) life circumstances, and

(g) presenting problems and, if relevant, diagnosis(es).

Note that this Client section is not a clinical assessment (this is below in section 4, Assessment). Rather, The Client section is a short description that places the patient in the context of their life, physical surrounds, and individuals with whom they must often interact.

3. Guiding Conception with Research and Clinical Experience Support

This section should inform the reader about:

(a) the type of clinical problem area(s) the client is presenting with and the relevant theoretical and clinical literature describing these problems. (The specific details and context of the client’s problems are presented in section 4, Assessment, described below.)

(b) your theoretical approach to understanding others in general and, more specifically, to the problem area(s) being addressed;

(c) how your theoretical approach is translated into therapy; and

(d) your roadmap to the clinical work that needs to be done.

This Guiding Conception section provides the reader a context for understanding you as a therapist and how you work with the problem area(s) involved. This section should include references to important books and journal articles—including past case study articles—that you have found important over the years and have influenced how you approach and do psychotherapy. This section alerts the readers to general aspects of the client and their entire life that you will utilize in making your Assessment (section 4 below) of the client’s problems; your Case Formulation and Treatment Plan (section 5 below); and your conduct of Therapy (section 6 below).

4. A ssessment of the Client’s Problems, Goals, Strengths, and History

This section should provide the reader with a systematic understanding of the client, including:

(a) their presenting problem(s);

(b) other problems and challenges;

(c) relevant diagnoses, keeping in mind both the strengths and limitations of diagnostic categories;

(d) personality and character issues;

(e) their initial stated goals for treatment;

(f) previous therapy;

(g) relevant aspects of their life history (personal development, family issues and events, and educational and work history);

(h) multicultural issues capturing the larger socio-cultural context of the case, including information about the client’s gender, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic class, etc.; and

(i) their strengths as well as limitations.

This section should present the methods and results of any quantitative assessment or other measurement tools you collected at intake, during therapy, at termination, and/or at follow-up.

5. F ormulation and Treatment Plan

(a) This section should provide the reader with your conceptualization of what—in clinical theory terms—the client’s problems and issues are and how you planned to address them. Understanding of an individual, the conceptualization of their problems, and the goals of treatment can change over time.

(b) Provide the initial Case Formulation and Treatment Plan of the case in this section.

(c) In section 6 below, Course of Therapy, describe any changes that occurred in the Assessment, in the Case Formulation, and in the Treatment Plan as the treatment progressed.

6. C ourse of Therapy

This is the main section of the case study and should provide a detailed description of the process of the psychotherapy that occurred.

(a) Note that a very important way to capture the richness, subtlety, power, emotional and experiential nature, and relational dynamics of the therapy is through the use of selected transcript excerpts. Specifically, sample transcripts of the verbal exchange between patient and therapist should be utilized liberally to provide the concrete details of the clinical process, including at important points—such as points of client insight, of client obstacles, of client corrective emotional experiences, of ruptures and repairs in the therapeutic relationship, of therapist insight, crucial therapist choice points, and so forth.

(b) Descriptions of the therapy can be organized by: (i) by Session; (ii) by Blocks of Sessions; and/or (iii) by Phases (Sessions grouped into substantive Phases).

The goal is to provide the reader with a rich experiential sense of the client and the process of doing psychotherapy with this client. Some questions to think and write about:

(a) How did the client present themselves?

(b) What sort of therapeutic relationship was established?

(c) How did the client react to different comments or interventions you made? (d) How did the therapeutic relationship change over time? (e) How did you adjust your style or word choice in light of the client’s behavior or reactions? (f) How did you bring up or introduce important issues that the client might have been avoiding?

Keep in mind the role and importance of other voices and influences in the therapy, such as a spouse, other family members, a boss, employees, colleagues, and friends.

7. T herapy Monitoring and Use of Feedback Information

This section should describe how the patient’s problems and behaviors were assessed over the course of therapy and how the process of therapy was monitored.

(a) Were quantitative treatment monitoring tools (such as the OQ-45 inventory ( https://www.oqmeasures.com/oq-45-2/ ) employed in each session, in selected sessions, and/or at the beginning and end of treatment and at follow-up?

(b) Were the psychotherapy sessions recorded or videotaped?

(c) What type of clinical notes were made?

(d) How was the supervision of the therapy handled?

8. Concluding Evaluation of the Therapy's Process and Outcome

This section should be a summary of the process and outcome of the treatment, using both qualitative and, ideally, quantitative data.

(a) What changes, if any, occurred?

(b) Were the goals set in the treatment plan met?

(c) How satisfied was the patient with the journey and its outcome?

(d) How, in general terms, did the process go?

(e) What comments and interventions seemed the most helpful? Least helpful?

Overall Guidelines Across the Eight Areas

(a) Be systematic, properly covering each of sections 1-8 and their interrelationships, ensuring a common structure with other pragmatic case studies.

(b) Clearly differentiate description from theory.

(c) Remember that the goal of a pragmatic case study is primarily to describe and interpret what happened in this particular case as a basic unit of knowledge in the field—not primarily to illustrate or confirm a theory, strategy, or procedure per se.

GENERAL GUIDELINES

Page Length

Manuscripts are to be typed double-spaced, following the APA Publication Manual. The format for pragmatic case studies allows a good deal of flexibility in page length. In terms of total pages independent of references, tables, figures, and appendices, PCSP manuscripts typically range between 35 and 90 pages. In terms of a 35-page manuscript, the first 8 sections might be distributed something like as follows (this is just an example, not a rigid requirement):

- Case Context and Method, 1 ½ pages.

- The client, ½ page.

- Guiding Conception with Research and Clinical Experience Support, 4 pages.

- Assessment of the Client’s Problems, Goals, Strengths, and History, 5 pages.

- Formulation and Treatment Plan, 4 pages.

- Course of the Therapy, 15 pages.

- Therapy Monitoring and Use of Feedback Information, 1 page.

- Concluding Evaluation of the Therapy’s Process and Outcome, 4 pages.

Note: Additional pages would be devoted to relevant references, tables, and figures.

Quantitative Data

The use of relevant quantitative data for assessment of problems, for monitoring therapy, and for outcome at termination and, if relevant, at follow-up is highly desirable. Almost all the case studies published in PCSP provide examples of the use of relevant quantitative data.

Note that if prospective quantitative measures are not collected, an option is to employ retrospective quantitative assessment. In this method, the client is asked at the end of therapy or at follow-up to complete quantitative measures a number of times with different mind sets, e.g., how they were feeling, thinking, and/or behaving at the beginning of therapy, at the end of therapy, and at follow-up. While not directly comparable to a prospective quantitative, such retrospective quantitative assessment can provide a useful additional perspective on the outcome of the therapy as subjctively viewed by client.

Description Versus Theory

Pay careful attention to the distinction between the description of clinical phenomena in ordinary language versus the interpretation of those phenomena in theoretical language, indicated by the use of technical theoretical jargon. Particularly, the Assessment and Course of therapy sections should contain a good deal of clinical description, such that the clinical phenomena of the client and the therapy could reasonably be interpreted from a different theoretical point of view. The use of technical, theoretical “jargon” terms when needed should be explained, knowing that not every reader is deeply knowledgeable about the theoretical orientation being employed by the author. Overall, the goal of a pragmatic case study is primarily to describe and interpret what happened in a particular case as a basic unit of knowledge in the field—not primarily to confirm a theory, strategy, and/or procedure per se. Rather the goal is to show how a theory, strategy, and/or procedure functioned in a particular case setting.

Scholarship

Present your material so as to include references to relevant books, journal articles, and web sites—including past case study articles—so that your work is connected to the relevant scholarly and research literature.

A Checklist of Questions to be Answered About Your PCSP Manuscript

- Do you have separate sections with all the 8 headings in Figure 1?

- Do each of the headings follow the Specific Guidelines associated with them?

- Is the manuscript length between 35 and 90 pages (double-spaced; before references, tables, figures, and appendices)?

- If there is quantitative data (which is desirable), is it fully presented?

- Do you carefully distinguish between clinical description and clinical interpretation?

- Are there references to the relevant scholarly and research literature?

- Have you looked at sample cases from the journal as models?

Sample Cases

The published case studies in PCSP offer many examples of the variety of types of properly written case studies that, while varying in a number of ways, all follow the common structure outlined in Figure 1 and the specific and general guidelines outlined above. Sample cases can be found on the Home Page of this PCSP journal .

An instructive example of a case study published in PCSP is the case of “Caroline” by Ueli Kramer (2009; https://pcsp.nationalregister.org/index.php/pcsp/article/view/966/2366 ). An outline of the case illustrating the above headings is presented in Table 4 of Fishman (2013; https://pcsp.nationalregister.org/index.php/pcsp/article/view/1833/3256 ).

Fishman, D.B. (2013). The pragmatic case study method for creating rigorous and systematic, practitioner-friendly research. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy , 9 (4), Article 2, 403-425. Available: https://pcsp.nationalregister.org/index.php/pcsp/article/view/1833

Kramer, U. (2009). Individualizing exposure therapy for PTSD: The case of Caroline. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy , 5(2), Article 1, 1-24. Available: https://pcsp.nationalregister.org/index.php/pcsp/article/view/966/2366

Peterson, D.R. (1991). Connection and disconnection of research and practice in the education of professional psychologists. American Psychologist, 46 , 422-429.

Shapiro, J.L. (2023). Existential psychotherapy in a deep cultural context: The case of “Keo.” Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy , 19 (1), Article 1, 1-32. Available: https://pcsp.nationalregister.org/index.php/pcsp/article/view/2127/3524

Psychology: Research and Review

- Open access

- Published: 19 March 2021

Appraising psychotherapy case studies in practice-based evidence: introducing Case Study Evaluation-tool (CaSE)

- Greta Kaluzeviciute ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1197-177X 1

Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica volume 34 , Article number: 9 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

7294 Accesses

5 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Systematic case studies are often placed at the low end of evidence-based practice (EBP) due to lack of critical appraisal. This paper seeks to attend to this research gap by introducing a novel Case Study Evaluation-tool (CaSE). First, issues around knowledge generation and validity are assessed in both EBP and practice-based evidence (PBE) paradigms. Although systematic case studies are more aligned with PBE paradigm, the paper argues for a complimentary, third way approach between the two paradigms and their ‘exemplary’ methodologies: case studies and randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Second, the paper argues that all forms of research can produce ‘valid evidence’ but the validity itself needs to be assessed against each specific research method and purpose. Existing appraisal tools for qualitative research (JBI, CASP, ETQS) are shown to have limited relevance for the appraisal of systematic case studies through a comparative tool assessment. Third, the paper develops purpose-oriented evaluation criteria for systematic case studies through CaSE Checklist for Essential Components in Systematic Case Studies and CaSE Purpose-based Evaluative Framework for Systematic Case Studies. The checklist approach aids reviewers in assessing the presence or absence of essential case study components (internal validity). The framework approach aims to assess the effectiveness of each case against its set out research objectives and aims (external validity), based on different systematic case study purposes in psychotherapy. Finally, the paper demonstrates the application of the tool with a case example and notes further research trajectories for the development of CaSE tool.

Introduction

Due to growing demands of evidence-based practice, standardised research assessment and appraisal tools have become common in healthcare and clinical treatment (Hannes, Lockwood, & Pearson, 2010 ; Hartling, Chisholm, Thomson, & Dryden, 2012 ; Katrak, Bialocerkowski, Massy-Westropp, Kumar, & Grimmer, 2004 ). This allows researchers to critically appraise research findings on the basis of their validity, results, and usefulness (Hill & Spittlehouse, 2003 ). Despite the upsurge of critical appraisal in qualitative research (Williams, Boylan, & Nunan, 2019 ), there are no assessment or appraisal tools designed for psychotherapy case studies.

Although not without controversies (Michels, 2000 ), case studies remain central to the investigation of psychotherapy processes (Midgley, 2006 ; Willemsen, Della Rosa, & Kegerreis, 2017 ). This is particularly true of systematic case studies, the most common form of case study in contemporary psychotherapy research (Davison & Lazarus, 2007 ; McLeod & Elliott, 2011 ).

Unlike the classic clinical case study, systematic cases usually involve a team of researchers, who gather data from multiple different sources (e.g., questionnaires, observations by the therapist, interviews, statistical findings, clinical assessment, etc.), and involve a rigorous data triangulation process to assess whether the data from different sources converge (McLeod, 2010 ). Since systematic case studies are methodologically pluralistic, they have a greater interest in situating patients within the study of a broader population than clinical case studies (Iwakabe & Gazzola, 2009 ). Systematic case studies are considered to be an accessible method for developing research evidence-base in psychotherapy (Widdowson, 2011 ), especially since they correct some of the methodological limitations (e.g. lack of ‘third party’ perspectives and bias in data analysis) inherent to classic clinical case studies (Iwakabe & Gazzola, 2009 ). They have been used for the purposes of clinical training (Tuckett, 2008 ), outcome assessment (Hilliard, 1993 ), development of clinical techniques (Almond, 2004 ) and meta-analysis of qualitative findings (Timulak, 2009 ). All these developments signal a revived interest in the case study method, but also point to the obvious lack of a research assessment tool suitable for case studies in psychotherapy (Table 1 ).

To attend to this research gap, this paper first reviews issues around the conceptualisation of validity within the paradigms of evidence-based practice (EBP) and practice-based evidence (PBE). Although case studies are often positioned at the low end of EBP (Aveline, 2005 ), the paper suggests that systematic cases are a valuable form of evidence, capable of complimenting large-scale studies such as randomised controlled trials (RCTs). However, there remains a difficulty in assessing the quality and relevance of case study findings to broader psychotherapy research.

As a way forward, the paper introduces a novel Case Study Evaluation-tool (CaSE) in the form of CaSE Purpose - based Evaluative Framework for Systematic Case Studies and CaSE Checklist for Essential Components in Systematic Case Studies . The long-term development of CaSE would contribute to psychotherapy research and practice in three ways.

Given the significance of methodological pluralism and diverse research aims in systematic case studies, CaSE will not seek to prescribe explicit case study writing guidelines, which has already been done by numerous authors (McLeod, 2010 ; Meganck, Inslegers, Krivzov, & Notaerts, 2017 ; Willemsen et al., 2017 ). Instead, CaSE will enable the retrospective assessment of systematic case study findings and their relevance (or lack thereof) to broader psychotherapy research and practice. However, there is no reason to assume that CaSE cannot be used prospectively (i.e. producing systematic case studies in accordance to CaSE evaluative framework, as per point 3 in Table 2 ).

The development of a research assessment or appraisal tool is a lengthy, ongoing process (Long & Godfrey, 2004 ). It is particularly challenging to develop a comprehensive purpose - oriented evaluative framework, suitable for the assessment of diverse methodologies, aims and outcomes. As such, this paper should be treated as an introduction to the broader development of CaSE tool. It will introduce the rationale behind CaSE and lay out its main approach to evidence and evaluation, with further development in mind. A case example from the Single Case Archive (SCA) ( https://singlecasearchive.com ) will be used to demonstrate the application of the tool ‘in action’. The paper notes further research trajectories and discusses some of the limitations around the use of the tool.

Separating the wheat from the chaff: what is and is not evidence in psychotherapy (and who gets to decide?)

The common approach: evidence-based practice.

In the last two decades, psychotherapy has become increasingly centred around the idea of an evidence-based practice (EBP). Initially introduced in medicine, EBP has been defined as ‘conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients’ (Sackett, Rosenberg, Gray, Haynes, & Richardson, 1996 ). EBP revolves around efficacy research: it seeks to examine whether a specific intervention has a causal (in this case, measurable) effect on clinical populations (Barkham & Mellor-Clark, 2003 ). From a conceptual standpoint, Sackett and colleagues defined EBP as a paradigm that is inclusive of many methodologies, so long as they contribute towards clinical decision-making process and accumulation of best currently available evidence in any given set of circumstances (Gabbay & le May, 2011 ). Similarly, the American Psychological Association (APA, 2010 ) has recently issued calls for evidence-based systematic case studies in order to produce standardised measures for evaluating process and outcome data across different therapeutic modalities.

However, given EBP’s focus on establishing cause-and-effect relationships (Rosqvist, Thomas, & Truax, 2011 ), it is unsurprising that qualitative research is generally not considered to be ‘gold standard’ or ‘efficacious’ within this paradigm (Aveline, 2005 ; Cartwright & Hardie, 2012 ; Edwards, 2013 ; Edwards, Dattilio, & Bromley, 2004 ; Longhofer, Floersch, & Hartmann, 2017 ). Qualitative methods like systematic case studies maintain an appreciation for context, complexity and meaning making. Therefore, instead of measuring regularly occurring causal relations (as in quantitative studies), the focus is on studying complex social phenomena (e.g. relationships, events, experiences, feelings, etc.) (Erickson, 2012 ; Maxwell, 2004 ). Edwards ( 2013 ) points out that, although context-based research in systematic case studies is the bedrock of psychotherapy theory and practice, it has also become shrouded by an unfortunate ideological description: ‘anecdotal’ case studies (i.e. unscientific narratives lacking evidence, as opposed to ‘gold standard’ evidence, a term often used to describe the RCT method and the therapeutic modalities supported by it), leading to a further need for advocacy in and defence of the unique epistemic process involved in case study research (Fishman, Messer, Edwards, & Dattilio, 2017 ).

The EBP paradigm prioritises the quantitative approach to causality, most notably through its focus on high generalisability and the ability to deal with bias through randomisation process. These conditions are associated with randomised controlled trials (RCTs) but are limited (or, as some argue, impossible) in qualitative research methods such as the case study (Margison et al., 2000 ) (Table 3 ).

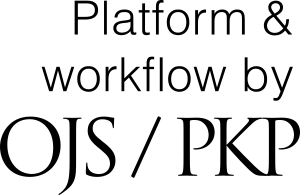

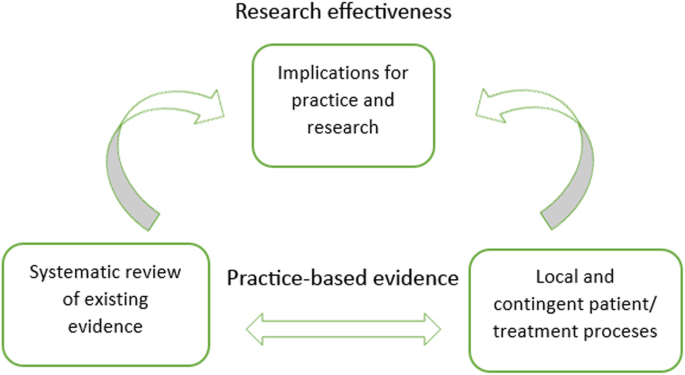

‘Evidence’ from an EBP standpoint hovers over the epistemological assumption of procedural objectivity : knowledge can be generated in a standardised, non-erroneous way, thus producing objective (i.e. with minimised bias) data. This can be achieved by anyone, as long as they are able to perform the methodological procedure (e.g. RCT) appropriately, in a ‘clearly defined and accepted process that assists with knowledge production’ (Douglas, 2004 , p. 131). If there is a well-outlined quantitative form for knowledge production, the same outcome should be achieved regardless of who processes or interprets the information. For example, researchers using Cochrane Review assess the strength of evidence using meticulously controlled and scrupulous techniques; in turn, this minimises individual judgment and creates unanimity of outcomes across different groups of people (Gabbay & le May, 2011 ). The typical process of knowledge generation (through employing RCTs and procedural objectivity) in EBP is demonstrated in Fig. 1 .

Typical knowledge generation process in evidence–based practice (EBP)

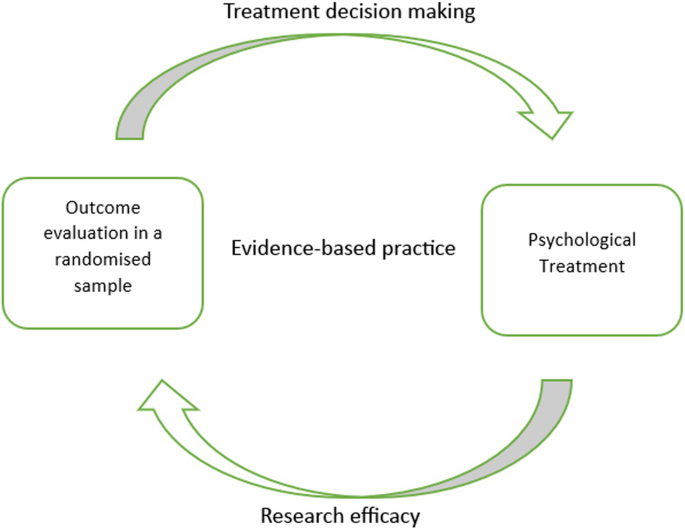

In EBP, the concept of validity remains somewhat controversial, with many critics stating that it limits rather than strengthens knowledge generation (Berg, 2019 ; Berg & Slaattelid, 2017 ; Lilienfeld, Ritschel, Lynn, Cautin, & Latzman, 2013 ). This is because efficacy research relies on internal validity . At a general level, this concept refers to the congruence between the research study and the research findings (i.e. the research findings were not influenced by anything external to the study, such as confounding variables, methodological errors and bias); at a more specific level, internal validity determines the extent to which a study establishes a reliable causal relationship between an independent variable (e.g. treatment) and independent variable (outcome or effect) (Margison et al., 2000 ). This approach to validity is demonstrated in Fig. 2 .

Internal validity

Social scientists have argued that there is a trade-off between research rigour and generalisability: the more specific the sample and the more rigorously defined the intervention, the outcome is likely to be less applicable to everyday, routine practice. As such, there remains a tension between employing procedural objectivity which increases the rigour of research outcomes and applying such outcomes to routine psychotherapy practice where scientific standards of evidence are not uniform.

According to McLeod ( 2002 ), inability to address questions that are most relevant for practitioners contributed to a deepening research–practice divide in psychotherapy. Studies investigating how practitioners make clinical decisions and the kinds of evidence they refer to show that there is a strong preference for knowledge that is not generated procedurally, i.e. knowledge that encompasses concrete clinical situations, experiences and techniques. A study by Stewart and Chambless ( 2007 ) sought to assess how a larger population of clinicians (under APA, from varying clinical schools of thought and independent practices, sample size 591) make treatment decisions in private practice. The study found that large-scale statistical data was not the primary source of information sought by clinicians. The most important influences were identified as past clinical experiences and clinical expertise ( M = 5.62). Treatment materials based on clinical case observations and theory ( M = 4.72) were used almost as frequently as psychotherapy outcome research findings ( M = 4.80) (i.e. evidence-based research). These numbers are likely to fluctuate across different forms of psychotherapy; however, they are indicative of the need for research about routine clinical settings that does not isolate or generalise the effect of an intervention but examines the variations in psychotherapy processes.

The alternative approach: practice-based evidence

In an attempt to dissolve or lessen the research–practice divide, an alternative paradigm of practice-based evidence (PBE) has been suggested (Barkham & Mellor-Clark, 2003 ; Fox, 2003 ; Green & Latchford, 2012 ; Iwakabe & Gazzola, 2009 ; Laska, Motulsky, Wertz, Morrow, & Ponterotto, 2014 ; Margison et al., 2000 ). PBE represents a shift in how we think about evidence and knowledge generation in psychotherapy. PBE treats research as a local and contingent process (at least initially), which means it focuses on variations (e.g. in patient symptoms) and complexities (e.g. of clinical setting) in the studied phenomena (Fox, 2003 ). Moreover, research and theory-building are seen as complementary rather than detached activities from clinical practice. That is to say, PBE seeks to examine how and which treatments can be improved in everyday clinical practice by flagging up clinically salient issues and developing clinical techniques (Barkham & Mellor-Clark, 2003 ). For this reason, PBE is concerned with the effectiveness of research findings: it evaluates how well interventions work in real-world settings (Rosqvist et al., 2011 ). Therefore, although it is not unlikely for RCTs to be used in order to generate practice-informed evidence (Horn & Gassaway, 2007 ), qualitative methods like the systematic case study are seen as ideal for demonstrating the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions with individual patients (van Hennik, 2020 ) (Table 4 ).

PBE’s epistemological approach to ‘evidence’ may be understood through the process of concordant objectivity (Douglas, 2004 ): ‘Instead of seeking to eliminate individual judgment, … [concordant objectivity] checks to see whether the individual judgments of people in fact do agree’ (p. 462). This does not mean that anyone can contribute to the evaluation process like in procedural objectivity, where the main criterion is following a set quantitative protocol or knowing how to operate a specific research design. Concordant objectivity requires that there is a set of competent observers who are closely familiar with the studied phenomenon (e.g. researchers and practitioners who are familiar with depression from a variety of therapeutic approaches).

Systematic case studies are a good example of PBE ‘in action’: they allow for the examination of detailed unfolding of events in psychotherapy practice, making it the most pragmatic and practice-oriented form of psychotherapy research (Fishman, 1999 , 2005 ). Furthermore, systematic case studies approach evidence and results through concordant objectivity (Douglas, 2004 ) by involving a team of researchers and rigorous data triangulation processes (McLeod, 2010 ). This means that, although systematic case studies remain focused on particular clinical situations and detailed subjective experiences (similar to classic clinical case studies; see Iwakabe & Gazzola, 2009 ), they still involve a series of validity checks and considerations on how findings from a single systematic case pertain to broader psychotherapy research (Fishman, 2005 ). The typical process of knowledge generation (through employing systematic case studies and concordant objectivity) in PBE is demonstrated in Fig. 3 . The figure exemplifies a bidirectional approach to research and practice, which includes the development of research-supported psychological treatments (through systematic reviews of existing evidence) as well as the perspectives of clinical practitioners in the research process (through the study of local and contingent patient and/or treatment processes) (Teachman et al., 2012 ; Westen, Novotny, & Thompson-Brenner, 2004 ).

Typical knowledge generation process in practice-based evidence (PBE)

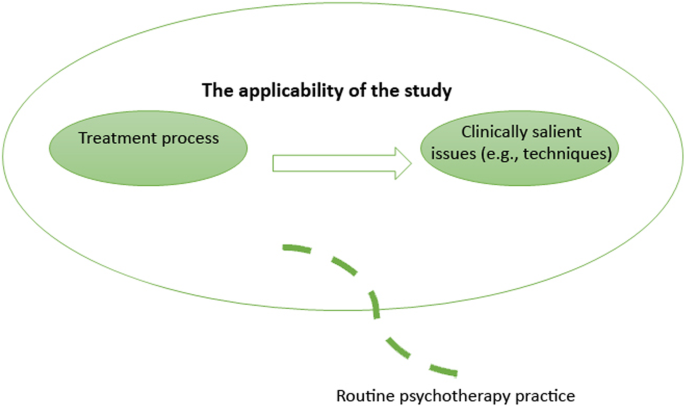

From a PBE standpoint, external validity is a desirable research condition: it measures extent to which the impact of interventions apply to real patients and therapists in everyday clinical settings. As such, external validity is not based on the strength of causal relationships between treatment interventions and outcomes (as in internal validity); instead, the use of specific therapeutic techniques and problem-solving decisions are considered to be important for generalising findings onto routine clinical practice (even if the findings are explicated from a single case study; see Aveline, 2005 ). This approach to validity is demonstrated in Fig. 4 .

External validity

Since effectiveness research is less focused on limiting the context of the studied phenomenon (indeed, explicating the context is often one of the research aims), there is more potential for confounding factors (e.g. bias and uncontrolled variables) which in turn can reduce the study’s internal validity (Barkham & Mellor-Clark, 2003 ). This is also an important challenge for research appraisal. Douglas ( 2004 ) argues that appraising research in terms of its effectiveness may produce significant disagreements or group illusions, since what might work for some practitioners may not work for others: ‘It cannot guarantee that values are not influencing or supplanting reasoning; the observers may have shared values that cause them to all disregard important aspects of an event’ (Douglas, 2004 , p. 462). Douglas further proposes that an interactive approach to objectivity may be employed as a more complex process in debating the evidential quality of a research study: it requires a discussion among observers and evaluators in the form of peer-review, scientific discourse, as well as research appraisal tools and instruments. While these processes of rigour are also applied in EBP, there appears to be much more space for debate, disagreement and interpretation in PBE’s approach to research evaluation, partly because the evaluation criteria themselves are subject of methodological debate and are often employed in different ways by researchers (Williams et al., 2019 ). This issue will be addressed more explicitly again in relation to CaSE development (‘Developing purpose-oriented evaluation criteria for systematic case studies’ section).

A third way approach to validity and evidence

The research–practice divide shows us that there may be something significant in establishing complementarity between EBP and PBE rather than treating them as mutually exclusive forms of research (Fishman et al., 2017 ). For one, EBP is not a sufficient condition for delivering research relevant to practice settings (Bower, 2003 ). While RCTs can demonstrate that an intervention works on average in a group, clinicians who are facing individual patients need to answer a different question: how can I make therapy work with this particular case ? (Cartwright & Hardie, 2012 ). Systematic case studies are ideal for filling this gap: they contain descriptions of microprocesses (e.g. patient symptoms, therapeutic relationships, therapist attitudes) in psychotherapy practice that are often overlooked in large-scale RCTs (Iwakabe & Gazzola, 2009 ). In particular, systematic case studies describing the use of specific interventions with less researched psychological conditions (e.g. childhood depression or complex post-traumatic stress disorder) can deepen practitioners’ understanding of effective clinical techniques before the results of large-scale outcome studies are disseminated.

Secondly, establishing a working relationship between systematic case studies and RCTs will contribute towards a more pragmatic understanding of validity in psychotherapy research. Indeed, the very tension and so-called trade-off between internal and external validity is based on the assumption that research methods are designed on an either/or basis; either they provide a sufficiently rigorous study design or they produce findings that can be applied to real-life practice. Jimenez-Buedo and Miller ( 2010 ) call this assumption into question: in their view, if a study is not internally valid, then ‘little, or rather nothing, can be said of the outside world’ (p. 302). In this sense, internal validity may be seen as a pre-requisite for any form of applied research and its external validity, but it need not be constrained to the quantitative approach of causality. For example, Levitt, Motulsky, Wertz, Morrow, and Ponterotto ( 2017 ) argue that, what is typically conceptualised as internal validity, is, in fact, a much broader construct, involving the assessment of how the research method (whether qualitative or quantitative) is best suited for the research goal, and whether it obtains the relevant conclusions. Similarly, Truijens, Cornelis, Desmet, and De Smet ( 2019 ) suggest that we should think about validity in a broader epistemic sense—not just in terms of psychometric measures, but also in terms of the research design, procedure, goals (research questions), approaches to inquiry (paradigms, epistemological assumptions), etc.

The overarching argument from research cited above is that all forms of research—qualitative and quantitative—can produce ‘valid evidence’ but the validity itself needs to be assessed against each specific research method and purpose. For example, RCTs are accompanied with a variety of clearly outlined appraisal tools and instruments such as CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) that are well suited for the assessment of RCT validity and their implications for EBP. Systematic case studies (or case studies more generally) currently have no appraisal tools in any discipline. The next section evaluates whether existing qualitative research appraisal tools are relevant for systematic case studies in psychotherapy and specifies the missing evaluative criteria.

The relevance of existing appraisal tools for qualitative research to systematic case studies in psychotherapy

What is a research tool.

Currently, there are several research appraisal tools, checklists and frameworks for qualitative studies. It is important to note that tools, checklists and frameworks are not equivalent to one another but actually refer to different approaches to appraising the validity of a research study. As such, it is erroneous to assume that all forms of qualitative appraisal feature the same aims and methods (Hannes et al., 2010 ; Williams et al., 2019 ).

Generally, research assessment falls into two categories: checklists and frameworks . Checklist approaches are often contrasted with quantitative research, since the focus is on assessing the internal validity of research (i.e. researcher’s independence from the study). This involves the assessment of bias in sampling, participant recruitment, data collection and analysis. Framework approaches to research appraisal, on the other hand, revolve around traditional qualitative concepts such as transparency, reflexivity, dependability and transferability (Williams et al., 2019 ). Framework approaches to appraisal are often challenging to use because they depend on the reviewer’s familiarisation and interpretation of the qualitative concepts.

Because of these different approaches, there is some ambiguity in terminology, particularly between research appraisal instruments and research appraisal tools . These terms are often used interchangeably in appraisal literature (Williams et al., 2019 ). In this paper, research appraisal tool is defined as a method-specific (i.e. it identifies a specific research method or component) form of appraisal that draws from both checklist and framework approaches. Furthermore, a research appraisal tool seeks to inform decision making in EBP or PBE paradigms and provides explicit definitions of the tool’s evaluative framework (thus minimising—but by no means eliminating—the reviewers’ interpretation of the tool). This definition will be applied to CaSE (Table 5 ).

In contrast, research appraisal instruments are generally seen as a broader form of appraisal in the sense that they may evaluate a variety of methods (i.e. they are non-method specific or they do not target a particular research component), and are aimed at checking whether the research findings and/or the study design contain specific elements (e.g. the aims of research, the rationale behind design methodology, participant recruitment strategies, etc.).

There is often an implicit difference in audience between appraisal tools and instruments. Research appraisal instruments are often aimed at researchers who want to assess the strength of their study; however, the process of appraisal may not be made explicit in the study itself (besides mentioning that the tool was used to appraise the study). Research appraisal tools are aimed at researchers who wish to explicitly demonstrate the evidential quality of the study to the readers (which is particularly common in RCTs). All forms of appraisal used in the comparative exercise below are defined as ‘tools’, even though they have different appraisal approaches and aims.

Comparing different qualitative tools

Hannes et al. ( 2010 ) identified CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme-tool), JBI (Joanna Briggs Institute-tool) and ETQS (Evaluation Tool for Qualitative Studies) as the most frequently used critical appraisal tools by qualitative researchers. All three instruments are available online and are free of charge, which means that any researcher or reviewer can readily utilise CASP, JBI or ETQS evaluative frameworks to their research. Furthermore, all three instruments were developed within the context of organisational, institutional or consortium support (Tables 6 , 7 and 8 ).

It is important to note that neither of the three tools is specific to systematic case studies or psychotherapy case studies (which would include not only systematic but also experimental and clinical cases). This means that using CASP, JBI or ETQS for case study appraisal may come at a cost of overlooking elements and components specific to the systematic case study method.

Based on Hannes et al. ( 2010 ) comparative study of qualitative appraisal tools as well as the different evaluation criteria explicated in CASP, JBI and ETQS evaluative frameworks, I assessed how well each of the three tools is attuned to the methodological , clinical and theoretical aspects of systematic case studies in psychotherapy. The latter components were based on case study guidelines featured in the journal of Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy as well as components commonly used by published systematic case studies across a variety of other psychotherapy journals (e.g. Psychotherapy Research , Research In Psychotherapy : Psychopathology Process And Outcome , etc.) (see Table 9 for detailed descriptions of each component).

The evaluation criteria for each tool in Table 9 follows Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) ( 2017a , 2017b ); Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) ( 2018 ); and ETQS Questionnaire (first published in 2004 but revised continuously since). Table 10 demonstrates how each tool should be used (i.e. recommended reviewer responses to checklists and questionnaires).

Using CASP, JBI and ETQS for systematic case study appraisal

Although JBI, CASP and ETQS were all developed to appraise qualitative research, it is evident from the above comparison that there are significant differences between the three tools. For example, JBI and ETQS are well suited to assess researcher’s interpretations (Hannes et al. ( 2010 ) defined this as interpretive validity , a subcategory of internal validity ): the researcher’s ability to portray, understand and reflect on the research participants’ experiences, thoughts, viewpoints and intentions. JBI has an explicit requirement for participant voices to be clearly represented, whereas ETQS involves a set of questions about key characteristics of events, persons, times and settings that are relevant to the study. Furthermore, both JBI and ETQS seek to assess the researcher’s influence on the research, with ETQS particularly focusing on the evaluation of reflexivity (the researcher’s personal influence on the interpretation and collection of data). These elements are absent or addressed to a lesser extent in the CASP tool.

The appraisal of transferability of findings (what this paper previously referred to as external validity ) is addressed only by ETQS and CASP. Both tools have detailed questions about the value of research to practice and policy as well as its transferability to other populations and settings. Methodological research aspects are also extensively addressed by CASP and ETQS, but less so by JBI (which relies predominantly on congruity between research methodology and objectives without any particular assessment criteria for other data sources and/or data collection methods). Finally, the evaluation of theoretical aspects (referred to by Hannes et al. ( 2010 ) as theoretical validity ) is addressed only by JBI and ETQS; there are no assessment criteria for theoretical framework in CASP.

Given these differences, it is unsurprising that CASP, JBI and ETQS have limited relevance for systematic case studies in psychotherapy. First, it is evident that neither of the three tools has specific evaluative criteria for the clinical component of systematic case studies. Although JBI and ETQS feature some relevant questions about participants and their context, the conceptualisation of patients (and/or clients) in psychotherapy involves other kinds of data elements (e.g. diagnostic tools and questionnaires as well as therapist observations) that go beyond the usual participant data. Furthermore, much of the clinical data is intertwined with the therapist’s clinical decision-making and thinking style (Kaluzeviciute & Willemsen, 2020 ). As such, there is a need to appraise patient data and therapist interpretations not only on a separate basis, but also as two forms of knowledge that are deeply intertwined in the case narrative.

Secondly, since systematic case studies involve various forms of data, there is a need to appraise how these data converge (or how different methods complement one another in the case context) and how they can be transferred or applied in broader psychotherapy research and practice. These systematic case study components are attended to a degree by CASP (which is particularly attentive of methodological components) and ETQS (particularly specific criteria for research transferability onto policy and practice). These components are not addressed or less explicitly addressed by JBI. Overall, neither of the tools is attuned to all methodological, theoretical and clinical components of the systematic case study. Specifically, there are no clear evaluation criteria for the description of research teams (i.e. different data analysts and/or clinicians); the suitability of the systematic case study method; the description of patient’s clinical assessment; the use of other methods or data sources; the general data about therapeutic progress.

Finally, there is something to be said about the recommended reviewer responses (Table 10 ). Systematic case studies can vary significantly in their formulation and purpose. The methodological, theoretical and clinical components outlined in Table 9 follow guidelines made by case study journals; however, these are recommendations, not ‘set in stone’ case templates. For this reason, the straightforward checklist approaches adopted by JBI and CASP may be difficult to use for case study researchers and those reviewing case study research. The ETQS open-ended questionnaire approach suggested by Long and Godfrey ( 2004 ) enables a comprehensive, detailed and purpose-oriented assessment, suitable for the evaluation of systematic case studies. That said, there remains a challenge of ensuring that there is less space for the interpretation of evaluative criteria (Williams et al., 2019 ). The combination of checklist and framework approaches would, therefore, provide a more stable appraisal process across different reviewers.

Developing purpose-oriented evaluation criteria for systematic case studies

The starting point in developing evaluation criteria for Case Study Evaluation-tool (CaSE) is addressing the significance of pluralism in systematic case studies. Unlike RCTs, systematic case studies are pluralistic in the sense that they employ divergent practices in methodological procedures ( research process ), and they may include significantly different research aims and purpose ( the end - goal ) (Kaluzeviciute & Willemsen, 2020 ). While some systematic case studies will have an explicit intention to conceptualise and situate a single patient’s experiences and symptoms within a broader clinical population, others will focus on the exploration of phenomena as they emerge from the data. It is therefore important that CaSE is positioned within a purpose - oriented evaluative framework , suitable for the assessment of what each systematic case is good for (rather than determining an absolute measure of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ systematic case studies). This approach to evidence and appraisal is in line with the PBE paradigm. PBE emphasises the study of clinical complexities and variations through local and contingent settings (e.g. single case studies) and promotes methodological pluralism (Barkham & Mellor-Clark, 2003 ).

CaSE checklist for essential components in systematic case studies

In order to conceptualise purpose-oriented appraisal questions, we must first look at what unites and differentiates systematic case studies in psychotherapy. The commonly used theoretical, clinical and methodological systematic case study components were identified earlier in Table 9 . These components will be seen as essential and common to most systematic case studies in CaSE evaluative criteria. If these essential components are missing in a systematic case study, then it may be implied there is a lack of information, which in turn diminishes the evidential quality of the case. As such, the checklist serves as a tool for checking whether a case study is, indeed, systematic (as opposed to experimental or clinical; see Iwakabe & Gazzola, 2009 for further differentiation between methodologically distinct case study types) and should be used before CaSE Purpose - based Evaluative Framework for Systematic Case Studie s (which is designed for the appraisal of different purposes common to systematic case studies).

As noted earlier in the paper, checklist approaches to appraisal are useful when evaluating the presence or absence of specific information in a research study. This approach can be used to appraise essential components in systematic case studies, as shown below. From a pragmatic point view (Levitt et al., 2017 ; Truijens et al., 2019 ), CaSE Checklist for Essential Components in Systematic Case Studies can be seen as a way to ensure the internal validity of systematic case study: the reviewer is assessing whether sufficient information is provided about the case design, procedure, approaches to inquiry, etc., and whether they are relevant to the researcher’s objectives and conclusions (Table 11 ).

CaSE purpose-based evaluative framework for systematic case studies

Identifying differences between systematic case studies means identifying the different purposes systematic case studies have in psychotherapy. Based on the earlier work by social scientist Yin ( 1984 , 1993 ), we can differentiate between exploratory (hypothesis generating, indicating a beginning phase of research), descriptive (particularising case data as it emerges) and representative (a case that is typical of a broader clinical population, referred to as the ‘explanatory case’ by Yin) cases.

Another increasingly significant strand of systematic case studies is transferable (aggregating and transferring case study findings) cases. These cases are based on the process of meta-synthesis (Iwakabe & Gazzola, 2009 ): by examining processes and outcomes in many different case studies dealing with similar clinical issues, researchers can identify common themes and inferences. In this way, single case studies that have relatively little impact on clinical practice, research or health care policy (in the sense that they capture psychotherapy processes rather than produce generalisable claims as in Yin’s representative case studies) can contribute to the generation of a wider knowledge base in psychotherapy (Iwakabe, 2003 , 2005 ). However, there is an ongoing issue of assessing the evidential quality of such transferable cases. According to Duncan and Sparks ( 2020 ), although meta-synthesis and meta-analysis are considered to be ‘gold standard’ for assessing interventions across disparate studies in psychotherapy, they often contain case studies with significant research limitations, inappropriate interpretations and insufficient information. It is therefore important to have a research appraisal process in place for selecting transferable case studies.