- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Psychology Research Paper

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

James Lacy, MLS, is a fact-checker and researcher.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/James-Lacy-1000-73de2239670146618c03f8b77f02f84e.jpg)

Are you working on a psychology research paper this semester? Whether or not this is your first research paper, the entire process can seem a bit overwhelming at first. But, knowing where to start the research process can make things easier and less stressful.

While it can feel very intimidating, a research paper can initially be very intimidating, but it is not quite as scary if you break it down into more manageable steps. The following tips will help you break down the process into steps so it is easier to research and write your paper.

Decide What Kind of Paper You Are Going to Write

Before you begin, you should find out the type of paper your instructor expects you to write. There are a few common types of psychology papers that you might encounter.

Original Research or Lab Report

A report or empirical paper details research you conducted on your own. This is the type of paper you would write if your instructor had you perform your own psychology experiment. This type of paper follows a format similar to an APA format lab report. It includes a title page, abstract , introduction, method section, results section, discussion section, and references.

Literature Review

The second type of paper is a literature review that summarizes research conducted by other people on a particular topic. If you are writing a psychology research paper in this form, your instructor might specify the length it needs to be or the number of studies you need to cite. Student are often required to cite between 5 and 20 studies in their literature reviews and they are usually between 8 and 20 pages in length.

The format and sections of a literature review usually include an introduction, body, and discussion/implications/conclusions.

Literature reviews often begin by introducing the research question before narrowing the focus to the specific studies cited in the paper. Each cited study should be described in considerable detail. You should evaluate and compare the studies you cite and then offer your discussion of the implications of the findings.

Select an Idea for Your Research Paper

Hero Images / Getty Images

Once you have figured out the type of research paper you are going to write, it is time to choose a good topic . In many cases, your instructor may assign you a subject, or at least specify an overall theme on which to focus.

As you are selecting your topic, try to avoid general or overly broad subjects. For example, instead of writing a research paper on the general subject of attachment , you might instead focus your research on how insecure attachment styles in early childhood impact romantic attachments later in life.

Narrowing your topic will make writing your paper easier because it allows you to focus your research, develop your thesis, and fully explore pertinent findings.

Develop an Effective Research Strategy

As you find references for your psychology paper, take careful notes on the information you use and start developing a bibliography. If you stay organized and cite your sources throughout the writing process, you will not be left searching for an important bit of information you cannot seem to track back to the source.

So, as you do your research, make careful notes about each reference including the article title, authors, journal source, and what the article was about.

Write an Outline

You might be tempted to immediately dive into writing, but developing a strong framework can save a lot of time, hassle, and frustration. It can also help you spot potential problems with flow and structure.

If you outline the paper right off the bat, you will have a better idea of how one idea flows into the next and how your research supports your overall hypothesis .

You should start the outline with the three most fundamental sections: the introduction, the body, and the conclusion. Then, start creating subsections based on your literature review. The more detailed your outline, the easier it will be to write your paper.

Draft, Revise, and Edit

Once you are confident in your outline, it is time to begin writing. Remember to follow APA format as you write your paper and include in-text citations for any materials you reference. Make sure to cite any information in the body of your paper in your reference section at the end of your document.

Writing a psychology research paper can be intimidating at first, but breaking the process into a series of smaller steps makes it more manageable. Be sure to start early by deciding on a substantial topic, doing your research, and creating a good outline . Doing these supporting steps ahead of time make it much easier to actually write the paper when the time comes.

- Beins, BC & Beins, A. Effective Writing in Psychology: Papers, Posters, and Presentation. New York: Blackwell Publishing; 2011.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Tips for Writing Your Best Psychology Research Paper

A checklist of do's and don'ts for students to write papers people want to read..

Posted July 17, 2022 | Reviewed by Tyler Woods

- What Is a Career

- Take our Procrastination

- Find a career counselor near me

- Scientific writing is non-intuitive in many ways.

- When it comes to writing psychology research reports, a primary goal should be clear communication.

- Here is a list of tips to help behavioral scientists, at all levels, to best communicate ideas regarding psychological research findings.

When it comes to reading academic research reports in the behavioral sciences, I'm no different than anyone else. I often find myself thinking "what is the point?" Reading academic papers is not always rainbows, balloons, and unicorns.

As a teacher and researcher, I regularly provide commentary on student research papers, with the primary goal of helping students best express complex ideas. Based on this experience, here is something of a checklist of issues to think about when writing a psychology research report.

Write as you speak.

So often, I read student papers that sound much more like someone trying to sound smart than like someone trying to communicate ideas. You made it into college—you're likely plenty smart. Don't worry about using big words.

The point of summarizing your research is to present it to others so that they understand what you are saying.

One way to achieve this outcome is simply to write as you speak. When you speak to others, you are trying to get them to understand something. This same goal is true when you are writing a scientific research report. Sure, avoid informalities, slang, and profanity in scientific writing—but beyond that, I suggest that you simply write how you speak.

Never copy and paste so much as a letter from another source.

In this day and age, it is common for students to copy and paste content from others' papers into their own. From there, students will often edit, modify, etc. Regarding this practice, I say this: Never do that! Not only does this practice have you dancing dangerously on the edge of plagiarism, but it is just a poor way to communicate.

When it comes to summarizing ideas from past researchers, your best bet is to read their work to the point that you really understand it and then to write your ideas out as if you are describing the ideas to a friend or family member. Doing so will ensure that your voice comes through.

Only summarize parts of past research that are relevant to your own research.

Sometimes, students feel that they have to summarize everything that they find in a relevant article connected with their research. Not so.

Imagine that you are writing a paper about how academic self-esteem (belief in oneself in academic contexts) relates to academic success (e.g., grade point average).

Now suppose that in your review of past work on this topic, you find a paper that summarizes five different studies that another researcher conducted on this topic. Imagine that one of the five studies examined the relationship between general self-esteem and academic self-esteem. Now imagine that this particular issue is unrelated to your own study. In this case, it would be a mistake to elaborate on this particular feature of this past work in detail.

Sometimes it feels like a student describing irrelevant details of others' work is intentionally trying to add length to their paper. Honestly, don't ever do that! Only include content that is relevant to your point. If there is a part of a prior paper that is not related to the point of your work, don't include it.

Avoid writing superfluous details about past studies (sample sizes, specific statistical findings, and ancillary findings) that do not relate to your own work.

Here's something that students often do not know. When very in-the-weeds details about a prior study make it into your paper, it comes across as a rookie mistake.

Such details often include the sample size from a prior study (e.g., "In Smith and Johnson's (2019) study, 632 young adult participants from a large, midwestern university were studied..."). Honestly, no one cares! In your own research report, describe your sample in detail—but not such details of past work.

Describing samples of other studies in detail in your own paper automatically puts the reader in zone-out mode.

This same rule applies to statistical findings from past studies. Suppose that Smith and Johnson found that high academic self-esteem corresponded to high GPAs in a sample of students from a community college. That's all you need to say! If you go on and describe the r-value and the p-value and the N of that prior research, you are once again inviting your reader to go into zone-out mode.

Include a brief summary at the end of your Introduction that includes clearly specified hypotheses.

The whole point of your Introduction is to get the reader to see the problem that you are studying and to see the value of studying that problem. A strong way to communicate all of this is to make sure to specify your hypotheses (or predictions) clearly in a section that completes your Introduction. Summarizing your specific predictions in detail in this section helps to provide a bridge between your Introduction and your Methods sections.

Make sure that each variable in your study is described in your Introduction so that the reader knows why it is included.

When a variable shows up in your Methods section that was not introduced in the Introduction, the reader will automatically be confused. The reader may think, "Wait, what? The intro didn't say anything about this variable. I have no idea what the relevance is here!" Each variable included in your Methods section should be described in some detail in your Introduction section—especially as it relates to the main predictions of your study.

Include sub-sections in your Introduction to help guide your reader to your broader points.

Reading scientific papers is not easy. One way to help make your presentation easier on your reader is by including sub-sections in your Introduction. APA style fully allows you to include as many sub-sections as you want in your Introduction.

You can create sections for each variable that you study in your project. You can create sections that describe past work related to the topic, etc. A sub-section will usually have between two and five paragraphs, just as a rule of thumb. Doing this will help in making your ideas clear to your reader.

Refer to hypotheses in words and not by some arbitrary numbers.

Near the end of the Introduction, as noted above, it is best practice to demarcate your specific hypotheses. Sometimes, a researcher will describe these in numbered form (e.g., Hypothesis 1: We predict that high levels of academic self-esteem will be positively related to cumulative grade point average . Hypothesis 2...).

In the hypothesis section of your Introduction, it is fine to number your hypotheses in this way. That said, later in your paper, it is not good practice to refer to your hypotheses by number. For instance, in your results section, you can imagine saying something like, "Hypothesis 1 was supported by a correlation."

By the time I get to the Results section, I usually don't recall which particular prediction comprised "Hypothesis 1." It's best practice to refer to your hypotheses in terms of the actual, relevant content. You could call it "the hypothesis suggesting that academic self-esteem is positively related to GPA." Such an approach will make it so that your reader is not flipping back to a prior section.

In your Methods section, describe each measuring instrument in detail and include academic citations that point to the full scale when appropriate.

In your Methods section, it is best practice to describe each measure in enough detail so that your audience has a solid idea as to how the measuring instrument works.

For instance, if you use a published scale of general self-esteem in your study, you should not only provide the full academic citation to this scale, but you should also give one example item (e.g., "Here is an example item: 'Generally speaking, I like myself.'") and you should describe the measuring system in sufficient detail (e.g., are the items on a 1-5 Likert scale, anchored with Strong Disagree and Strongly Agree? If so, say that.). This basic process should be used for each measuring instrument included in your study.

Never end your paper with a limitation of your work.

Life is hard enough and there are endless critics out there. It is appropriate to describe limitations to your work in your Discussion section, but it is not great practice to end your paper with limitations of your work. That could leave the reader with something we call the recency effect —where they primarily remember the final information that was presented. You don't want your reader to walk away thinking that the main point of your work is that you had a small sample size in your research, for instance. Your ending should bring the paper full circle and focus on the value of your work as well as potential implications.

Bottom Line

In my work as a psychology professor, I both produce psychological research reports and I read and comment on many student papers that summarize research. In my efforts to help students hone their skills in this realm, I recently published a book: Own Your Psychology Major (Geher, 2019) , which helps guide students on various facets of the field of psychology, including the presentation of research findings.

People often find the process of scientific writing a bit non-intuitive. Following the tips above can help behavioral scientists at all levels communicate their ideas clearly, with the goal of having their ideas heard. Ultimately, this is the goal of all writing, including scientific writing.

Geher, G. (2019). Own Your Psychology Major! A Guide to Student Success. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Glenn Geher, Ph.D. , is professor of psychology at the State University of New York at New Paltz. He is founding director of the campus’ Evolutionary Studies (EvoS) program.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Psychological Science

Prospective submitters of manuscripts are encouraged to read Editor-in-Chief Simine Vazire’s editorial , as well as the editorial by Tom Hardwicke, Senior Editor for Statistics, Transparency, & Rigor, and Simine Vazire.

Psychological Science , the flagship journal of the Association for Psychological Science, is the leading peer-reviewed journal publishing empirical research spanning the entire spectrum of the science of psychology. The journal publishes high quality research articles of general interest and on important topics spanning the entire spectrum of the science of psychology. Replication studies are welcome and evaluated on the same criteria as novel studies. Articles are published in OnlineFirst before they are assigned to an issue. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) .

Quick Facts

| Simine Vazire | |

| Print: 0956-7976 Online: 1467-9280 | |

| 12 issues per year |

Read the February 2022 editorial by former Editor-in-Chief Patricia Bauer, “Psychological Science Stepping Up a Level.”

Read the January 2020 editorial by former Editor Patricia Bauer on her vision for the future of Psychological Science .

Read the December 2015 editorial on replication by former Editor Steve Lindsay, as well as his April 2017 editorial on sharing data and materials during the review process.

Watch Geoff Cumming’s video workshop on the new statistics.

Current Issue

Online First Articles

List of Issues

Editorial Board

Submission Guidelines

Editorial Policies

Featured research from psychological science.

Visual Memory Distortions Paint a Picture of the Past That Never Was

Basic research on our imperfect visual memories is bringing to light how and why we may misremember what we have seen.

Teens Who View Their Homes as More Chaotic Than Their Siblings Have Poorer Mental Health in Adulthood

Many parents ponder why one of their children seems more emotionally troubled than the others. A new study in the United Kingdom reveals a possible basis for those differences.

Rewatching Videos of People Shifts How We Judge Them, Study Indicates

Rewatching recorded behavior, whether on a Tik-Tok video or police body-camera footage, makes even the most spontaneous actions seem more rehearsed or deliberate, new research shows.

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELBCORS | 5 minutes | This cookie is used by Elastic Load Balancing from Amazon Web Services to effectively balance load on the servers. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| at-rand | never | AddThis sets this cookie to track page visits, sources of traffic and share counts. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| uvc | 1 year 27 days | Set by addthis.com to determine the usage of addthis.com service. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_3507334_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| loc | 1 year 27 days | AddThis sets this geolocation cookie to help understand the location of users who share the information. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Anxiety, Affect, Self-Esteem, and Stress: Mediation and Moderation Effects on Depression

Affiliations Department of Psychology, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, Network for Empowerment and Well-Being, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

Affiliation Network for Empowerment and Well-Being, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

Affiliations Department of Psychology, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, Network for Empowerment and Well-Being, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, Department of Psychology, Education and Sport Science, Linneaus University, Kalmar, Sweden

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Network for Empowerment and Well-Being, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, Center for Ethics, Law, and Mental Health (CELAM), University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, The Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

- Ali Al Nima,

- Patricia Rosenberg,

- Trevor Archer,

- Danilo Garcia

- Published: September 9, 2013

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265

- Reader Comments

23 Sep 2013: Nima AA, Rosenberg P, Archer T, Garcia D (2013) Correction: Anxiety, Affect, Self-Esteem, and Stress: Mediation and Moderation Effects on Depression. PLOS ONE 8(9): 10.1371/annotation/49e2c5c8-e8a8-4011-80fc-02c6724b2acc. https://doi.org/10.1371/annotation/49e2c5c8-e8a8-4011-80fc-02c6724b2acc View correction

Mediation analysis investigates whether a variable (i.e., mediator) changes in regard to an independent variable, in turn, affecting a dependent variable. Moderation analysis, on the other hand, investigates whether the statistical interaction between independent variables predict a dependent variable. Although this difference between these two types of analysis is explicit in current literature, there is still confusion with regard to the mediating and moderating effects of different variables on depression. The purpose of this study was to assess the mediating and moderating effects of anxiety, stress, positive affect, and negative affect on depression.

Two hundred and two university students (males = 93, females = 113) completed questionnaires assessing anxiety, stress, self-esteem, positive and negative affect, and depression. Mediation and moderation analyses were conducted using techniques based on standard multiple regression and hierarchical regression analyses.

Main Findings

The results indicated that (i) anxiety partially mediated the effects of both stress and self-esteem upon depression, (ii) that stress partially mediated the effects of anxiety and positive affect upon depression, (iii) that stress completely mediated the effects of self-esteem on depression, and (iv) that there was a significant interaction between stress and negative affect, and between positive affect and negative affect upon depression.

The study highlights different research questions that can be investigated depending on whether researchers decide to use the same variables as mediators and/or moderators.

Citation: Nima AA, Rosenberg P, Archer T, Garcia D (2013) Anxiety, Affect, Self-Esteem, and Stress: Mediation and Moderation Effects on Depression. PLoS ONE 8(9): e73265. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265

Editor: Ben J. Harrison, The University of Melbourne, Australia

Received: February 21, 2013; Accepted: July 22, 2013; Published: September 9, 2013

Copyright: © 2013 Nima et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The authors have no support or funding to report.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Mediation refers to the covariance relationships among three variables: an independent variable (1), an assumed mediating variable (2), and a dependent variable (3). Mediation analysis investigates whether the mediating variable accounts for a significant amount of the shared variance between the independent and the dependent variables–the mediator changes in regard to the independent variable, in turn, affecting the dependent one [1] , [2] . On the other hand, moderation refers to the examination of the statistical interaction between independent variables in predicting a dependent variable [1] , [3] . In contrast to the mediator, the moderator is not expected to be correlated with both the independent and the dependent variable–Baron and Kenny [1] actually recommend that it is best if the moderator is not correlated with the independent variable and if the moderator is relatively stable, like a demographic variable (e.g., gender, socio-economic status) or a personality trait (e.g., affectivity).

Although both types of analysis lead to different conclusions [3] and the distinction between statistical procedures is part of the current literature [2] , there is still confusion about the use of moderation and mediation analyses using data pertaining to the prediction of depression. There are, for example, contradictions among studies that investigate mediating and moderating effects of anxiety, stress, self-esteem, and affect on depression. Depression, anxiety and stress are suggested to influence individuals' social relations and activities, work, and studies, as well as compromising decision-making and coping strategies [4] , [5] , [6] . Successfully coping with anxiety, depressiveness, and stressful situations may contribute to high levels of self-esteem and self-confidence, in addition increasing well-being, and psychological and physical health [6] . Thus, it is important to disentangle how these variables are related to each other. However, while some researchers perform mediation analysis with some of the variables mentioned here, other researchers conduct moderation analysis with the same variables. Seldom are both moderation and mediation performed on the same dataset. Before disentangling mediation and moderation effects on depression in the current literature, we briefly present the methodology behind the analysis performed in this study.

Mediation and moderation

Baron and Kenny [1] postulated several criteria for the analysis of a mediating effect: a significant correlation between the independent and the dependent variable, the independent variable must be significantly associated with the mediator, the mediator predicts the dependent variable even when the independent variable is controlled for, and the correlation between the independent and the dependent variable must be eliminated or reduced when the mediator is controlled for. All the criteria is then tested using the Sobel test which shows whether indirect effects are significant or not [1] , [7] . A complete mediating effect occurs when the correlation between the independent and the dependent variable are eliminated when the mediator is controlled for [8] . Analyses of mediation can, for example, help researchers to move beyond answering if high levels of stress lead to high levels of depression. With mediation analysis researchers might instead answer how stress is related to depression.

In contrast to mediation, moderation investigates the unique conditions under which two variables are related [3] . The third variable here, the moderator, is not an intermediate variable in the causal sequence from the independent to the dependent variable. For the analysis of moderation effects, the relation between the independent and dependent variable must be different at different levels of the moderator [3] . Moderators are included in the statistical analysis as an interaction term [1] . When analyzing moderating effects the variables should first be centered (i.e., calculating the mean to become 0 and the standard deviation to become 1) in order to avoid problems with multi-colinearity [8] . Moderating effects can be calculated using multiple hierarchical linear regressions whereby main effects are presented in the first step and interactions in the second step [1] . Analysis of moderation, for example, helps researchers to answer when or under which conditions stress is related to depression.

Mediation and moderation effects on depression

Cognitive vulnerability models suggest that maladaptive self-schema mirroring helplessness and low self-esteem explain the development and maintenance of depression (for a review see [9] ). These cognitive vulnerability factors become activated by negative life events or negative moods [10] and are suggested to interact with environmental stressors to increase risk for depression and other emotional disorders [11] , [10] . In this line of thinking, the experience of stress, low self-esteem, and negative emotions can cause depression, but also be used to explain how (i.e., mediation) and under which conditions (i.e., moderation) specific variables influence depression.

Using mediational analyses to investigate how cognitive therapy intervations reduced depression, researchers have showed that the intervention reduced anxiety, which in turn was responsible for 91% of the reduction in depression [12] . In the same study, reductions in depression, by the intervention, accounted only for 6% of the reduction in anxiety. Thus, anxiety seems to affect depression more than depression affects anxiety and, together with stress, is both a cause of and a powerful mediator influencing depression (See also [13] ). Indeed, there are positive relationships between depression, anxiety and stress in different cultures [14] . Moreover, while some studies show that stress (independent variable) increases anxiety (mediator), which in turn increased depression (dependent variable) [14] , other studies show that stress (moderator) interacts with maladaptive self-schemata (dependent variable) to increase depression (independent variable) [15] , [16] .

The present study

In order to illustrate how mediation and moderation can be used to address different research questions we first focus our attention to anxiety and stress as mediators of different variables that earlier have been shown to be related to depression. Secondly, we use all variables to find which of these variables moderate the effects on depression.

The specific aims of the present study were:

- To investigate if anxiety mediated the effect of stress, self-esteem, and affect on depression.

- To investigate if stress mediated the effects of anxiety, self-esteem, and affect on depression.

- To examine moderation effects between anxiety, stress, self-esteem, and affect on depression.

Ethics statement

This research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Gothenburg and written informed consent was obtained from all the study participants.

Participants

The present study was based upon a sample of 206 participants (males = 93, females = 113). All the participants were first year students in different disciplines at two universities in South Sweden. The mean age for the male students was 25.93 years ( SD = 6.66), and 25.30 years ( SD = 5.83) for the female students.

In total, 206 questionnaires were distributed to the students. Together 202 questionnaires were responded to leaving a total dropout of 1.94%. This dropout concerned three sections that the participants chose not to respond to at all, and one section that was completed incorrectly. None of these four questionnaires was included in the analyses.

Instruments

Hospital anxiety and depression scale [17] ..

The Swedish translation of this instrument [18] was used to measure anxiety and depression. The instrument consists of 14 statements (7 of which measure depression and 7 measure anxiety) to which participants are asked to respond grade of agreement on a Likert scale (0 to 3). The utility, reliability and validity of the instrument has been shown in multiple studies (e.g., [19] ).

Perceived Stress Scale [20] .

The Swedish version [21] of this instrument was used to measures individuals' experience of stress. The instrument consist of 14 statements to which participants rate on a Likert scale (0 = never , 4 = very often ). High values indicate that the individual expresses a high degree of stress.

Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale [22] .

The Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale (Swedish version by Lindwall [23] ) consists of 10 statements focusing on general feelings toward the self. Participants are asked to report grade of agreement in a four-point Likert scale (1 = agree not at all, 4 = agree completely ). This is the most widely used instrument for estimation of self-esteem with high levels of reliability and validity (e.g., [24] , [25] ).

Positive Affect and Negative Affect Schedule [26] .

This is a widely applied instrument for measuring individuals' self-reported mood and feelings. The Swedish version has been used among participants of different ages and occupations (e.g., [27] , [28] , [29] ). The instrument consists of 20 adjectives, 10 positive affect (e.g., proud, strong) and 10 negative affect (e.g., afraid, irritable). The adjectives are rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all , 5 = very much ). The instrument is a reliable, valid, and effective self-report instrument for estimating these two important and independent aspects of mood [26] .

Questionnaires were distributed to the participants on several different locations within the university, including the library and lecture halls. Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire after being informed about the purpose and duration (10–15 minutes) of the study. Participants were also ensured complete anonymity and informed that they could end their participation whenever they liked.

Correlational analysis

Depression showed positive, significant relationships with anxiety, stress and negative affect. Table 1 presents the correlation coefficients, mean values and standard deviations ( sd ), as well as Cronbach ' s α for all the variables in the study.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.t001

Mediation analysis

Regression analyses were performed in order to investigate if anxiety mediated the effect of stress, self-esteem, and affect on depression (aim 1). The first regression showed that stress ( B = .03, 95% CI [.02,.05], β = .36, t = 4.32, p <.001), self-esteem ( B = −.03, 95% CI [−.05, −.01], β = −.24, t = −3.20, p <.001), and positive affect ( B = −.02, 95% CI [−.05, −.01], β = −.19, t = −2.93, p = .004) had each an unique effect on depression. Surprisingly, negative affect did not predict depression ( p = 0.77) and was therefore removed from the mediation model, thus not included in further analysis.

The second regression tested whether stress, self-esteem and positive affect uniquely predicted the mediator (i.e., anxiety). Stress was found to be positively associated ( B = .21, 95% CI [.15,.27], β = .47, t = 7.35, p <.001), whereas self-esteem was negatively associated ( B = −.29, 95% CI [−.38, −.21], β = −.42, t = −6.48, p <.001) to anxiety. Positive affect, however, was not associated to anxiety ( p = .50) and was therefore removed from further analysis.

A hierarchical regression analysis using depression as the outcome variable was performed using stress and self-esteem as predictors in the first step, and anxiety as predictor in the second step. This analysis allows the examination of whether stress and self-esteem predict depression and if this relation is weaken in the presence of anxiety as the mediator. The result indicated that, in the first step, both stress ( B = .04, 95% CI [.03,.05], β = .45, t = 6.43, p <.001) and self-esteem ( B = .04, 95% CI [.03,.05], β = .45, t = 6.43, p <.001) predicted depression. When anxiety (i.e., the mediator) was controlled for predictability was reduced somewhat but was still significant for stress ( B = .03, 95% CI [.02,.04], β = .33, t = 4.29, p <.001) and for self-esteem ( B = −.03, 95% CI [−.05, −.01], β = −.20, t = −2.62, p = .009). Anxiety, as a mediator, predicted depression even when both stress and self-esteem were controlled for ( B = .05, 95% CI [.02,.08], β = .26, t = 3.17, p = .002). Anxiety improved the prediction of depression over-and-above the independent variables (i.e., stress and self-esteem) (Δ R 2 = .03, F (1, 198) = 10.06, p = .002). See Table 2 for the details.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.t002

A Sobel test was conducted to test the mediating criteria and to assess whether indirect effects were significant or not. The result showed that the complete pathway from stress (independent variable) to anxiety (mediator) to depression (dependent variable) was significant ( z = 2.89, p = .003). The complete pathway from self-esteem (independent variable) to anxiety (mediator) to depression (dependent variable) was also significant ( z = 2.82, p = .004). Thus, indicating that anxiety partially mediates the effects of both stress and self-esteem on depression. This result may indicate also that both stress and self-esteem contribute directly to explain the variation in depression and indirectly via experienced level of anxiety (see Figure 1 ).

Changes in Beta weights when the mediator is present are highlighted in red.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.g001

For the second aim, regression analyses were performed in order to test if stress mediated the effect of anxiety, self-esteem, and affect on depression. The first regression showed that anxiety ( B = .07, 95% CI [.04,.10], β = .37, t = 4.57, p <.001), self-esteem ( B = −.02, 95% CI [−.05, −.01], β = −.18, t = −2.23, p = .03), and positive affect ( B = −.03, 95% CI [−.04, −.02], β = −.27, t = −4.35, p <.001) predicted depression independently of each other. Negative affect did not predict depression ( p = 0.74) and was therefore removed from further analysis.

The second regression investigated if anxiety, self-esteem and positive affect uniquely predicted the mediator (i.e., stress). Stress was positively associated to anxiety ( B = 1.01, 95% CI [.75, 1.30], β = .46, t = 7.35, p <.001), negatively associated to self-esteem ( B = −.30, 95% CI [−.50, −.01], β = −.19, t = −2.90, p = .004), and a negatively associated to positive affect ( B = −.33, 95% CI [−.46, −.20], β = −.27, t = −5.02, p <.001).

A hierarchical regression analysis using depression as the outcome and anxiety, self-esteem, and positive affect as the predictors in the first step, and stress as the predictor in the second step, allowed the examination of whether anxiety, self-esteem and positive affect predicted depression and if this association would weaken when stress (i.e., the mediator) was present. In the first step of the regression anxiety ( B = .07, 95% CI [.05,.10], β = .38, t = 5.31, p = .02), self-esteem ( B = −.03, 95% CI [−.05, −.01], β = −.18, t = −2.41, p = .02), and positive affect ( B = −.03, 95% CI [−.04, −.02], β = −.27, t = −4.36, p <.001) significantly explained depression. When stress (i.e., the mediator) was controlled for, predictability was reduced somewhat but was still significant for anxiety ( B = .05, 95% CI [.02,.08], β = .05, t = 4.29, p <.001) and for positive affect ( B = −.02, 95% CI [−.04, −.01], β = −.20, t = −3.16, p = .002), whereas self-esteem did not reach significance ( p < = .08). In the second step, the mediator (i.e., stress) predicted depression even when anxiety, self-esteem, and positive affect were controlled for ( B = .02, 95% CI [.08,.04], β = .25, t = 3.07, p = .002). Stress improved the prediction of depression over-and-above the independent variables (i.e., anxiety, self-esteem and positive affect) (Δ R 2 = .02, F (1, 197) = 9.40, p = .002). See Table 3 for the details.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.t003

Furthermore, the Sobel test indicated that the complete pathways from the independent variables (anxiety: z = 2.81, p = .004; self-esteem: z = 2.05, p = .04; positive affect: z = 2.58, p <.01) to the mediator (i.e., stress), to the outcome (i.e., depression) were significant. These specific results might be explained on the basis that stress partially mediated the effects of both anxiety and positive affect on depression while stress completely mediated the effects of self-esteem on depression. In other words, anxiety and positive affect contributed directly to explain the variation in depression and indirectly via the experienced level of stress. Self-esteem contributed only indirectly via the experienced level of stress to explain the variation in depression. In other words, stress effects on depression originate from “its own power” and explained more of the variation in depression than self-esteem (see Figure 2 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.g002

Moderation analysis

Multiple linear regression analyses were used in order to examine moderation effects between anxiety, stress, self-esteem and affect on depression. The analysis indicated that about 52% of the variation in the dependent variable (i.e., depression) could be explained by the main effects and the interaction effects ( R 2 = .55, adjusted R 2 = .51, F (55, 186) = 14.87, p <.001). When the variables (dependent and independent) were standardized, both the standardized regression coefficients beta (β) and the unstandardized regression coefficients beta (B) became the same value with regard to the main effects. Three of the main effects were significant and contributed uniquely to high levels of depression: anxiety ( B = .26, t = 3.12, p = .002), stress ( B = .25, t = 2.86, p = .005), and self-esteem ( B = −.17, t = −2.17, p = .03). The main effect of positive affect was also significant and contributed to low levels of depression ( B = −.16, t = −2.027, p = .02) (see Figure 3 ). Furthermore, the results indicated that two moderator effects were significant. These were the interaction between stress and negative affect ( B = −.28, β = −.39, t = −2.36, p = .02) (see Figure 4 ) and the interaction between positive affect and negative affect ( B = −.21, β = −.29, t = −2.30, p = .02) ( Figure 5 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.g003

Low stress and low negative affect leads to lower levels of depression compared to high stress and high negative affect.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.g004

High positive affect and low negative affect lead to lower levels of depression compared to low positive affect and high negative affect.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.g005

The results in the present study show that (i) anxiety partially mediated the effects of both stress and self-esteem on depression, (ii) that stress partially mediated the effects of anxiety and positive affect on depression, (iii) that stress completely mediated the effects of self-esteem on depression, and (iv) that there was a significant interaction between stress and negative affect, and positive affect and negative affect on depression.

Mediating effects

The study suggests that anxiety contributes directly to explaining the variance in depression while stress and self-esteem might contribute directly to explaining the variance in depression and indirectly by increasing feelings of anxiety. Indeed, individuals who experience stress over a long period of time are susceptible to increased anxiety and depression [30] , [31] and previous research shows that high self-esteem seems to buffer against anxiety and depression [32] , [33] . The study also showed that stress partially mediated the effects of both anxiety and positive affect on depression and that stress completely mediated the effects of self-esteem on depression. Anxiety and positive affect contributed directly to explain the variation in depression and indirectly to the experienced level of stress. Self-esteem contributed only indirectly via the experienced level of stress to explain the variation in depression, i.e. stress affects depression on the basis of ‘its own power’ and explains much more of the variation in depressive experiences than self-esteem. In general, individuals who experience low anxiety and frequently experience positive affect seem to experience low stress, which might reduce their levels of depression. Academic stress, for instance, may increase the risk for experiencing depression among students [34] . Although self-esteem did not emerged as an important variable here, under circumstances in which difficulties in life become chronic, some researchers suggest that low self-esteem facilitates the experience of stress [35] .

Moderator effects/interaction effects

The present study showed that the interaction between stress and negative affect and between positive and negative affect influenced self-reported depression symptoms. Moderation effects between stress and negative affect imply that the students experiencing low levels of stress and low negative affect reported lower levels of depression than those who experience high levels of stress and high negative affect. This result confirms earlier findings that underline the strong positive association between negative affect and both stress and depression [36] , [37] . Nevertheless, negative affect by itself did not predicted depression. In this regard, it is important to point out that the absence of positive emotions is a better predictor of morbidity than the presence of negative emotions [38] , [39] . A modification to this statement, as illustrated by the results discussed next, could be that the presence of negative emotions in conjunction with the absence of positive emotions increases morbidity.

The moderating effects between positive and negative affect on the experience of depression imply that the students experiencing high levels of positive affect and low levels of negative affect reported lower levels of depression than those who experience low levels of positive affect and high levels of negative affect. This result fits previous observations indicating that different combinations of these affect dimensions are related to different measures of physical and mental health and well-being, such as, blood pressure, depression, quality of sleep, anxiety, life satisfaction, psychological well-being, and self-regulation [40] – [51] .

Limitations

The result indicated a relatively low mean value for depression ( M = 3.69), perhaps because the studied population was university students. These might limit the generalization power of the results and might also explain why negative affect, commonly associated to depression, was not related to depression in the present study. Moreover, there is a potential influence of single source/single method variance on the findings, especially given the high correlation between all the variables under examination.

Conclusions

The present study highlights different results that could be arrived depending on whether researchers decide to use variables as mediators or moderators. For example, when using meditational analyses, anxiety and stress seem to be important factors that explain how the different variables used here influence depression–increases in anxiety and stress by any other factor seem to lead to increases in depression. In contrast, when moderation analyses were used, the interaction of stress and affect predicted depression and the interaction of both affectivity dimensions (i.e., positive and negative affect) also predicted depression–stress might increase depression under the condition that the individual is high in negative affectivity, in turn, negative affectivity might increase depression under the condition that the individual experiences low positive affectivity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their openness and suggestions, which significantly improved the article.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: AAN TA. Performed the experiments: AAN. Analyzed the data: AAN DG. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: AAN TA DG. Wrote the paper: AAN PR TA DG.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 3. MacKinnon DP, Luecken LJ (2008) How and for Whom? Mediation and Moderation in Health Psychology. Health Psychol 27 (2 Suppl.): s99–s102.

- 4. Aaroe R (2006) Vinn över din depression [Defeat depression]. Stockholm: Liber.

- 5. Agerberg M (1998) Ut ur mörkret [Out from the Darkness]. Stockholm: Nordstedt.

- 6. Gilbert P (2005) Hantera din depression [Cope with your Depression]. Stockholm: Bokförlaget Prisma.

- 8. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2007) Using Multivariate Statistics, Fifth Edition. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc.

- 10. Beck AT (1967) Depression: Causes and treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- 21. Eskin M, Parr D (1996) Introducing a Swedish version of an instrument measuring mental stress. Stockholm: Psykologiska institutionen Stockholms Universitet.

- 22. Rosenberg M (1965) Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- 23. Lindwall M (2011) Självkänsla – Bortom populärpsykologi & enkla sanningar [Self-Esteem – Beyond Popular Psychology and Simple Truths]. Lund:Studentlitteratur.

- 25. Blascovich J, Tomaka J (1991) Measures of self-esteem. In: Robinson JP, Shaver PR, Wrightsman LS (Red.) Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes San Diego: Academic Press. 161–194.

- 30. Eysenck M (Ed.) (2000) Psychology: an integrated approach. New York: Oxford University Press.

- 31. Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer.

- 32. Johnson M (2003) Självkänsla och anpassning [Self-esteem and Adaptation]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- 33. Cullberg Weston M (2005) Ditt inre centrum – Om självkänsla, självbild och konturen av ditt själv [Your Inner Centre – About Self-esteem, Self-image and the Contours of Yourself]. Stockholm: Natur och Kultur.

- 34. Lindén M (1997) Studentens livssituation. Frihet, sårbarhet, kris och utveckling [Students' Life Situation. Freedom, Vulnerability, Crisis and Development]. Uppsala: Studenthälsan.

- 35. Williams S (1995) Press utan stress ger maximal prestation [Pressure without Stress gives Maximal Performance]. Malmö: Richters förlag.

- 37. Garcia D, Kerekes N, Andersson-Arntén A–C, Archer T (2012) Temperament, Character, and Adolescents' Depressive Symptoms: Focusing on Affect. Depress Res Treat. DOI:10.1155/2012/925372.

- 40. Garcia D, Ghiabi B, Moradi S, Siddiqui A, Archer T (2013) The Happy Personality: A Tale of Two Philosophies. In Morris EF, Jackson M-A editors. Psychology of Personality. New York: Nova Science Publishers. 41–59.

- 41. Schütz E, Nima AA, Sailer U, Andersson-Arntén A–C, Archer T, Garcia D (2013) The affective profiles in the USA: Happiness, depression, life satisfaction, and happiness-increasing strategies. In press.

- 43. Garcia D, Nima AA, Archer T (2013) Temperament and Character's Relationship to Subjective Well- Being in Salvadorian Adolescents and Young Adults. In press.

- 44. Garcia D (2013) La vie en Rose: High Levels of Well-Being and Events Inside and Outside Autobiographical Memory. J Happiness Stud. DOI: 10.1007/s10902-013-9443-x.

- 48. Adrianson L, Djumaludin A, Neila R, Archer T (2013) Cultural influences upon health, affect, self-esteem and impulsiveness: An Indonesian-Swedish comparison. Int J Res Stud Psychol. DOI: 10.5861/ijrsp.2013.228.

Psychology Research Network

Welcome to PsychRN

The Psychology Research Network

- Conference Proceedings

- Job Openings

- Partners in Publishing

- Professional Announcements

- Research Paper Series

Psychology Preprints

Psychology is the science of mind and behavior. Contemporary psychology research strives to answer questions about human thinking and interaction in a wide variety of settings. The Psychology Research Network on SSRN is an open access preprint server that provides a venue for authors to showcase their research papers in our digital library, speeding up the dissemination and providing the scholarly community access to groundbreaking working papers, early stage research and even peer reviewed or published journal articles. SSRN provides the opportunity to share different outputs of research such as preliminary or exploratory investigations, book chapters, PhD dissertations, course and teaching materials, presentations, and posters among others. SSRN also helps psychology scholars discover the latest research in their own and other fields of interest, while providing a platform for the early sharing of their own work, making it available for subsequent work to be built upon more quickly.

Given the breadth and depth of psychological research, as well as its cross and interdisciplinary nature, SSRN provides important and organized categorical links between psychological research and other research areas including anthropology, arts, cognitive science, economics, education, law, linguistics, medical sciences, philosophy, and technology. Thus, SSRN provides a unique opportunity for researchers to submit early and novel work for review, feedback, and use by researchers within and beyond psychology.

Psychology Papers

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Psychology articles from across Nature Portfolio

Psychology is a scientific discipline that focuses on understanding mental functions and the behaviour of individuals and groups.

Eating habits of Denisovans on the Tibetan Plateau revealed

The discovery of a rib fragment from Baishiya Karst Cave greatly extends the presence of Denisovan hominins on the Tibetan Plateau. In-depth analyses of fossilized animal bones from the same site show that Denisovans made full use of the available animal resources.

The neuroscience of turning heads

Measuring neural activity in moving humans has been a longstanding challenge in neuroscience, which limits what we know about our navigational neural codes. Leveraging mobile EEG and motion capture, Griffiths et al. overcome this challenge to elucidate neural representations of direction and highlight key cross-species similarities.

- Sergio A. Pecirno

- Alexandra T. Keinath

Child brains respond to climate change

Maternal exposure to ambient heat during pregnancy has been shown to increase the risk for several adverse birth outcomes. Now research reveals that variations of ambient temperature during pregnancy and childhood could have a long-term impact on a child’s brain development.

- Johanna Lepeule

Related Subjects

- Human behaviour

Latest Research and Reviews

Age-related differences in subjective and physiological emotion evoked by immersion in natural and social virtual environments

- Katarina Pavic

- Dorine Vergilino-Perez

- Laurence Chaby

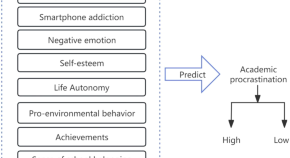

Predictive analysis of college students’ academic procrastination behavior based on a decision tree model

- Xiangwei Liu

- Xiangmei Zhu

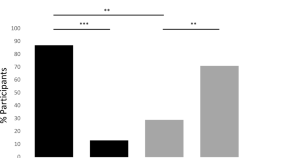

Normative data of the Italian Famous Face Test

- Martina Ventura

- Alessandro Oronzo Caffò

- Davide Rivolta

Advancing research and practice of psychological intergroup interventions

The decline in intergroup relations is evident in myriad conflicts around the world. This Review consolidates research from four domains in social psychology (prejudice reduction, conflict resolution, intergroup reconciliation and affective polarization) to elucidate the critical features necessary for successful intergroup interventions.

- Sabina Čehajić-Clancy

- Eran Halperin

The association between 2D:4D digit ratio and sex-typed play in children with and without siblings

- Luisa Ernsten

- Lisa M. Körner

- Nora K. Schaal

“ How ” web searches change under stress

- Christopher A. Kelly

- Bastien Blain

- Tali Sharot

News and Comment

Elevating well-being science to the population level.

- Elizabeth W. Chan

Neuroscientists must not be afraid to study religion

Scientists interested in the brain have tended to avoid studying religion or spirituality for fear of being seen as unscientific. That needs to change.

- Patrick McNamara

- William Newsome

- Jordan Grafman

How and why psychologists should respond to the harms associated with generative AI

Innovations in generative AI can cause social, psychological, and political harms. This Comment explains how psychologists can mobilize their extensive theoretical and empirical resources to better anticipate, understand, and mitigate those harms.

- Laura G. E. Smith

- Richard Owen

- Olivia Brown

Premature call for implementation of Tetris in clinical practice: a commentary on Deforges et al. (2023)

- Joar Øveraas Halvorsen

- Ineke Wessel

- Ioana A. Cristea

Exploring brain representations through the lens of similarity structures

- Stefania Mattioni

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Psychological Review

- Read this journal

- Read free articles

- Journal snapshot

- Advertising information

Journal scope statement

Psychological Review ® publishes articles that make important theoretical contributions to any area of scientific psychology, including systematic evaluation of alternative theories. Papers mainly focused on surveys of the literature, problems of method and design, or reports of empirical findings are not appropriate.

There is no upper bound on the length of Psychological Review articles. However, authors who submit papers with texts longer than 15,000 words will be asked to justify the need for their length.

Psychological Review also publishes Theoretical Notes—commentaries that contribute to progress in a given subfield of scientific psychology. Such notes include, but are not limited to, discussions of previously published articles, comments that apply to a class of theoretical models in a given domain, critiques and discussions of alternative theoretical approaches, and meta-theoretical discourse on theory testing and related topics.

Disclaimer: APA and the editors of Psychological Review assume no responsibility for statements and opinions advanced by the authors of its articles.

Equity, diversity, and inclusion

Psychological Review supports equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in its practices. More information on these initiatives is available under EDI Efforts .

Open science

The APA Journals Program is committed to publishing transparent, rigorous research; improving reproducibility in science; and aiding research discovery. Open science practices vary per editor discretion. View the initiatives implemented by this journal .

Editor's Choice

Each issue of the Psychological Review will honor one accepted manuscript per issue by selecting it as an “ Editor’s Choice ” paper. Selection is based on the discretion of the editor if the paper offers an unusually large potential impact to the field and/or elevates an important future direction for science.

Author and editor spotlights

Explore journal highlights : free article summaries, editor interviews and editorials, journal awards, mentorship opportunities, and more.

Prior to submission, please carefully read and follow the submission guidelines detailed below. Manuscripts that do not conform to the submission guidelines may be returned without review.

To submit to the editorial office of Elena L. Grigorenko, PhD, please submit manuscripts electronically through the Manuscript Submission Portal in Microsoft Word or Open Office format.

Prepare manuscripts according to the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association using the 7 th edition. Manuscripts may be copyedited for bias-free language (see Chapter 5 of the Publication Manual ). APA Style and Grammar Guidelines for the 7 th edition are available.

Submit Manuscript

Elena L. Grigorenko, PhD Editor, Psychological Review

General correspondence may be directed to the editor's office .

Do not submit manuscripts to the editor’s email address.

All submissions should be clear and readable. An unusual typeface is acceptable only if it is clear and legible.

In addition to addresses and phone numbers, please supply electronic mail addresses and fax numbers, if available, for potential use by the editorial office and later by the production office.

Psychological Review ® is now using a software system to screen submitted content for similarity with other published content. The system compares the initial version of each submitted manuscript against a database of 40+ million scholarly documents, as well as content appearing on the open web. This allows APA to check submissions for potential overlap with material previously published in scholarly journals (e.g., lifted or republished material).

Each issue of REV will honor one manuscript as the Editor’s Choice .

Selection criteria

The Editor’s Choice article will be selected based on an assessment of the following criteria. In addition to the editor’s own assessment of these criteria, information provided in the peer reviews (numerical ratings and comments) and the AEs’ decision letters will be used as data for selection.

- Diversity: Does the study advance our understanding of how legal institutions and policy makers should work with and treat diverse groups of people? Does the study contribute to improving services for underserved populations?

- Innovation: Does the study lead to significantly new knowledge, ask unexamined questions, and/or use highly novel methods to inform policy and legal practice?

- Methodological rigor: Do the methods meet the highest level of methodological rigor for the particular field of study?

- Policy significance/impact: Does the study have significant and direct implications that can change/improve/increase practices in the legal or policy areas?

Selection process

When the editor prepares the table of contents each quarter, the editor will identify the article that they believe best meets the criteria in consultation with the associate editors.

Associate editors will be invited to nominate articles for Editor’s Choice. The editor will consider these nominations in their selection review process.

Masked review policy

Open (i.e., unmasked) review is the default for this journal, though masked review is an option. If you choose masked review, include authors' names and affiliations only in the cover letter for the manuscript.

Authors who choose masked review should make every effort to see that the manuscript itself contains no clues to their identities, including grant numbers, names of institutions providing IRB approval, self-citations, and links to online repositories for data, materials, code, or preregistrations (e.g., Create a View-only Link for a Project ).

There is no upper bound on the length of Psychological Review articles.

However, authors who submit papers with texts longer than 15,000 words will be asked to justify the need for their length.

Psychological Review publishes direct replications if they are relevant to and/or embedded in new or enhanced theories. Submissions should include a mention of the replication in the abstract.

Journal Article Reporting Standards

Authors should review the APA Style Journal Article Reporting Standards (JARS) for quantitative and mixed methods. The standards offer ways to improve transparency in reporting to ensure that readers have the information necessary to evaluate the quality of the research and to facilitate collaboration and replication.

Author contribution statements using CRediT

The APA Publication Manual (7th ed.) stipulates that “authorship encompasses…not only persons who do the writing but also those who have made substantial scientific contributions to a study.” In the spirit of transparency and openness, Psychological Review has adopted the Contributor Roles Taxonomy (CRediT) to describe each author's individual contributions to the work. CRediT offers authors the opportunity to share an accurate and detailed description of their diverse contributions to a manuscript.

Submitting authors will be asked to identify the contributions of all authors at initial submission according to this taxonomy. If the manuscript is accepted for publication, the CRediT designations will be published as an Author Contributions Statement in the author note of the final article. All authors should have reviewed and agreed to their individual contribution(s) before submission.

CRediT includes 14 contributor roles, as described below:

- Conceptualization: Ideas; formulation or evolution of overarching research goals and aims.

- Data curation: Management activities to annotate (produce metadata), scrub data, and maintain research data (including software code, where it is necessary for interpreting the data itself) for initial use and later reuse.

- Formal analysis: Application of statistical, mathematical, computational, or other formal techniques to analyze or synthesize study data.

- Funding acquisition: Acquisition of the financial support for the project leading to this publication.

- Investigation: Conducting a research and investigation process, specifically performing the experiments, or data/evidence collection.

- Methodology: Development or design of methodology; creation of models.

- Project administration: Management and coordination responsibility for the research activity planning and execution.

- Resources: Provision of study materials, reagents, materials, patients, laboratory samples, animals, instrumentation, computing resources, or other analysis tools.

- Software: Programming, software development; designing computer programs; implementation of the computer code and supporting algorithms; testing of existing code components.

- Supervision: Oversight and leadership responsibility for the research activity planning and execution, including mentorship external to the core team.

- Validation: Verification, whether as a part of the activity or separate, of the overall replication/reproducibility of results/experiments and other research outputs.

- Visualization: Preparation, creation, and/or presentation of the published work, specifically visualization/data presentation.

- Writing—original draft: Preparation, creation, and/or presentation of the published work, specifically writing the initial draft (including substantive translation).

- Writing—review and editing: Preparation, creation and/or presentation of the published work by those from the original research group, specifically critical review, commentary, or revision—including pre- or post-publication stages.

Authors can claim credit for more than one contributor role, and the same role can be attributed to more than one author.

Transparency and openness

APA endorses the Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines by a community working group in conjunction with the Center for Open Science ( Nosek et al. 2015 ). Empirical research submitted to Psychological Review must at least meet the “disclosure” level for all eight aspects of research planning and reporting. Authors should include a subsection in the method section titled “Transparency and openness.” This subsection should detail the efforts the authors have made to comply with the TOP guidelines. For example:

- We report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions (if any), all manipulations, and all measures in the study, and the study follows JARS (Appelbaum et al., 2018). All data, analysis code, and research materials are available at [stable link to permanent repository]. Data were analyzed using R, version 4.0.0 (R Core Team, 2020) and the package ggplot , version 3.2.1 (Wickham, 2016). This study’s design and its analysis were not pre-registered.

Data, materials, and code

Reviews that include quantitative analyses (e.g., meta-analyses) must state whether data and study materials (if these were created for the review, e.g., coding schemes) are posted to a trusted repository and, if how, where to access them. Recommended repositories include APA’s repository on the Open Science Framework (OSF), or authors can access a full list of other recommended repositories . Trusted repositories adhere to policies that make data discoverable, accessible, usable, and preserved for the long term. Trusted repositories also assign unique and persistent identifiers.

In a subsection titled “Transparency and Openness” at the end of the Method section, specify whether and where the data and material will be available or include a statement noting that they are not available. For submissions with quantitative or simulation analytic methods, state whether the study analysis code is posted to a trusted repository, and, if so, how to access it.

For example:

- All data have been made publicly available at the [trusted repository name] and can be accessed at [persistent URL or DOI].

- Materials and analysis code for this study are available by emailing the corresponding author.

- Materials and analysis code for this study are not available.

- The code behind this analysis/simulation has been made publicly available at the [trusted repository name] and can be accessed at [persistent URL or DOI].

Preregistration of studies and analysis plans

Preregistration of studies and specific hypotheses can be a useful tool for making strong theoretical claims. Likewise, preregistration of analysis plans can be useful for distinguishing confirmatory and exploratory analyses. Investigators are encouraged to preregister their studies and analysis plans prior to conducting the research via a publicly accessible registry system (e.g., OSF , ClinicalTrials.gov , or other trial registries in the WHO Registry Network). There are many available templates; for example, APA, the British Psychological Society, and the German Psychological Society partnered with the Leibniz Institute for Psychology and Center for Open Science to create Preregistration for Quantitative Research in Psychology (Bosnjak et al., 2022). Preregistration Standards for Quantitative Research in Psychology

Articles must state whether or not any work was preregistered and, if so, where to access the preregistration. If reviews were pre-registered as protocols or if quantitative analyses were pre-registered, include the registry links in the Method section.

- For a systematic review: This review’s protocol was pre-registered prospectively before data were collected at [stable link to protocol]. We followed the PRISMA-P checklist when preparing the protocol, and we followed PRISMA reporting guidelines for the final report.

- For an unregistered review: This review was not pre-registered. We followed PRISMA reporting guidelines for the final report.

Manuscript preparation

Prepare manuscripts according to the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th edition). Manuscripts may be copyedited for bias-free language (see Chapter 3 of the 6th edition or Chapter 5 of the 7th edition).

Review APA's Journal Manuscript Preparation Guidelines before submitting your article.

Double-space all copy. Other formatting instructions, as well as instructions on preparing tables, figures, references, metrics, and abstracts, appear in the Manual . Additional guidance on APA Style is available on the APA Style website .

Below are additional instructions regarding the preparation of display equations, computer code, and tables.

Display equations

We strongly encourage you to use MathType (third-party software) or Equation Editor 3.0 (built into pre-2007 versions of Word) to construct your equations, rather than the equation support that is built into Word 2007 and Word 2010. Equations composed with the built-in Word 2007/Word 2010 equation support are converted to low-resolution graphics when they enter the production process and must be rekeyed by the typesetter, which may introduce errors.

To construct your equations with MathType or Equation Editor 3.0:

- Go to the Text section of the Insert tab and select Object.

- Select MathType or Equation Editor 3.0 in the drop-down menu.

If you have an equation that has already been produced using Microsoft Word 2007 or 2010 and you have access to the full version of MathType 6.5 or later, you can convert this equation to MathType by clicking on MathType Insert Equation. Copy the equation from Microsoft Word and paste it into the MathType box. Verify that your equation is correct, click File, and then click Update. Your equation has now been inserted into your Word file as a MathType Equation.

Use Equation Editor 3.0 or MathType only for equations or for formulas that cannot be produced as Word text using the Times or Symbol font.

Computer code

Authors of accepted articles who report new computer simulations of models, or new data-analysis software, are required to provide the code as online supplemental material ("additional content") at the time of final manuscript submission. It is important to include adequate documentation so that the code can be downloaded and used by other researchers.

Because altering computer code in any way (e.g., indents, line spacing, line breaks, page breaks) during the typesetting process could alter its meaning, we treat computer code differently from the rest of your article in our production process. To that end, we request separate files for computer code.

In online supplemental material

We request that runnable source code be included as supplemental material to the article. For more information, visit Supplementing Your Article With Online Material .

In the text of the article

If you would like to include code in the text of your published manuscript, please submit a separate file with your code exactly as you want it to appear, using Courier New font with a type size of 8 points. We will make an image of each segment of code in your article that exceeds 40 characters in length. (Shorter snippets of code that appear in text will be typeset in Courier New and run in with the rest of the text.) If an appendix contains a mix of code and explanatory text, please submit a file that contains the entire appendix, with the code keyed in 8-point Courier New.

Use Word's insert table function when you create tables. Using spaces or tabs in your table will create problems when the table is typeset and may result in errors.

LaTex files

LaTex files (.tex) should be uploaded with all other files such as BibTeX Generated Bibliography File (.bbl) or Bibliography Document (.bib) together in a compressed ZIP file folder for the manuscript submission process. In addition, a Portable Document Format (.pdf) of the manuscript file must be uploaded for the peer-review process.

Academic writing and English language editing services

Authors who feel that their manuscript may benefit from additional academic writing or language editing support prior to submission are encouraged to seek out such services at their host institutions, engage with colleagues and subject matter experts, and/or consider several vendors that offer discounts to APA authors .

Please note that APA does not endorse or take responsibility for the service providers listed. It is strictly a referral service.