Encyclopedia

Writing with artificial intelligence, coherence – how to achieve coherence in writing.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - Professor of English - USF

Coherence refers to a style of writing where ideas, themes, and language connect logically, consistently, and clearly to guide the reader's understanding. By mastering coherence , alongside flow , inclusiveness , simplicity, and unity , you'll be well-equipped to craft professional or academic pieces that engage and inform effectively. Acquire the skills to instill coherence in your work and discern it in the writings of others.

Table of Contents

What is Coherence?

Coherence in writing refers to the logical connections and consistency that hold a text together, making it understandable and meaningful to the reader. Writers create coherence in three ways:

- logical consistency

- conceptual consistency

- linguistic consistency.

What is Logical Consistency?

- For instance, if they argue, “If it rains, the ground gets wet,” and later state, “It’s raining but the ground isn’t wet,” without additional explanation, this represents a logical inconsistency.

What is Conceptual Consistency?

- For example, if you are writing an essay arguing that regular exercise has multiple benefits for mental health, each paragraph should introduce and discuss a different benefit of exercise, all contributing to your main argument. Including a paragraph discussing the nutritional value of various foods, while interesting, would break the conceptual consistency, as it doesn’t directly relate to the benefits of exercise for mental health.

What is Linguistic Consistency?

- For example, if a writer jumps erratically between different tenses or switches point of view without clear demarcation, the reader might find it hard to follow the narrative, leading to a lack of linguistic coherence.

Related Concepts: Flow ; Given to New Contract ; Grammar ; Organization ; Organizational Structures ; Organizational Patterns ; Sentence Errors

Why Does Coherence Matter?

Coherence is crucial in writing as it ensures that the text is understandable and that the ideas flow logically from one to the next. When writing is coherent, readers can easily follow the progression of ideas, making the content more engaging and easier to comprehend. Coherence connects the dots for the reader, linking concepts, arguments, and details in a clear, logical manner.

Without coherence, even the most interesting or groundbreaking ideas can become muddled and lose their impact. A coherent piece of writing keeps the reader’s attention, demonstrates the writer’s control over their subject matter, and can effectively persuade, inform, or entertain. Thus, coherence contributes significantly to the effectiveness of writing in achieving its intended purpose.

How Do Writers Create Coherence in Writing?

- Your thesis statement serves as the guiding star of your paper. It sets the direction and focus, ensuring all subsequent points relate back to this central idea.

- Acknowledge and address potential counterarguments to strengthen your position and add depth to your writing.

- Use the genres and organizational patterns appropriate for your rhetorical situation . A deductive structure (general to specific) is often effective, guiding the reader logically through your argument. Yet different disciplines may privilege more inductive approaches , such as law and philosophy.

- When following a given-to-new order, writers move from what the reader already knows to new information. In formal or persuasive contexts, writers are careful to vet new information for the reader following information literacy laws and conventions .

- Strategic repetition of crucial terms and your thesis helps your readers follow your main ideas and evidence for claims

- While repetition is useful, varying language with synonyms can prevent redundancy and keep the reader engaged.

- Parallelism in sentences can provide rhythm and clarity, making complex ideas easier to follow.

- Consistent use of pronouns avoids confusion and helps in maintaining a clear line of thought.

- Arrange your ideas in a sequence that naturally builds from one point to the next, ensuring each paragraph flows smoothly into the next .

- Signposting , or using phrases that indicate what’s coming next or what just happened, can help orient the reader within your argument.

- Don’t bother repeating your argument in your conclusion. Prioritize conciseness. Yet end with a call to action or appeal to kairos and ethos .

Recommended Resources

- Organization

- Organizational Patterns

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Recommended

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Structured Revision – How to Revise Your Work

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority & Credibility – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Research, Speech & Writing

Citation Guide – Learn How to Cite Sources in Academic and Professional Writing

Page Design – How to Design Messages for Maximum Impact

Suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

| Essay writing Essay writing |

Achieving coherence

“A piece of writing is coherent when it elicits the response: ‘I follow you. I see what you mean.’ It is incoherent when it elicits the response: ‘I see what you're saying here, but what has it got to do with the topic at hand or with what you just told me above?’ ” - Johns, A.M

Transitions

Parallelism, challenge task, what is coherence.

Coherence in a piece of writing means that the reader can easily understand it. Coherence is about making everything flow smoothly. The reader can see that everything is logically arranged and connected, and relevance to the central focus of the essay is maintained throughout.

Pronouns are useful cohesive devices because they make it unnecessary to repeat words too often. Consider the following:

Repetitious referencing:

When Gillette first invented disposable razor blades, he found it very hard to sell the disposable razor blades . He found it very hard to sell the disposable razor blades because nobody had marketed a throw-away product before.

When Gillette first invented disposable razor blades, he found it very hard to sell them . This was because nobody had marketed a throw-away product before.

Pronouns as cohesive devices

This following presentation shows how pronouns can be used effectively to achieve coherence within a text and some common problems of use.

Repetition in a piece of writing does not always demonstrate cohesion. Study these sentences:

|

So, how does repetition as a cohesive device work?

When a pronoun is used, sometimes what the pronoun refers to (ie, the referent) is not always clear. Clarity is achieved by repeating a key noun or synonym . Repetition is a cohesive device used deliberately to improve coherence in a text.

In the following text, decide ifthe referent for the pronoun it is clear. Otherwise, replace it with the key noun English where clarity is needed.

English has almost become an international language. Except for Chinese, more people speak it ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select3" ).html( document.getElementById( "select3" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); than any other language. Spanish is the official language of more countries in the world, but more countries have English ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select4" ).html( document.getElementById( "select4" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); as their official or unofficial second language. More than 70% of the world's mail is written in English ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select5" ).html( document.getElementById( "select5" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); It ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select6" ).html( document.getElementById( "select6" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); is the primary language on the Internet. (p.23). Text source: Oshima, A. and Hogue. A. (2006). (4th ed.). NY: Pearson Education |

Click here to view the revised text.

Suggested improvement

English has almost become an international language. Except for Chinese, more people speak it (clear reference; retain) than any other language. Spanish is the official language of more countries in the world, but more countries have English ( it is replaced with a key noun) as their official or unofficial second language. More than 70% of the world's mail is written in English ( it is replaced with a key noun). It (clear reference; retain) is the primary language on the Internet.

Sometimes, repetition of a key noun is preferred even when the reference is clear. In the following text, it is clear that it refers to the key noun gold , but when used throughout the text, the style becomes monotonous.

Gold, a precious metal, is prized for two important characteristics. First of all, has a lustrous beauty that is resistant to corrosion. Therefore, is suitable for jewellery, coins and ornamental purposes. never needs to be polished and will remain beautiful forever. For example, a Macedonian coin remains as untarnished today as the day it was minted 23 centuries ago. Another characteristic of is its usefulness to industry and science. For many years, has been used in hundreds of industrial applications, such as photography and dentistry. Its most recent use is in astronauts’ suits. Astronauts wear heat shields made from for protection when they go outside spaceships in space. In conclusion, is treasured not only for its beauty but also its utility. (p.22). Text source: Oshima, A. and Hogue, A. (2006). (4th ed.). NY: Pearson Education |

Improved text: Note where the key noun gold is repeated. The deliberate repetition creates interest and adds maturity to the writing style.

Gold , a precious metal, is prized for two important characteristics. First of all, gold has a lustrous beauty that is resistant to corrosion. Therefore, it is suitable for jewellery, coins and ornamental purposes. Gold never needs to be polished and will remain beautiful forever. For example, a Macedonian coin remains as untarnished today as the day it was made 23 centuries ago. Another important characteristic of gold is its usefulness to industry and science. For many years, it has been used in hundreds of industrial applications. The most recent use of gold is in astronauts’ suits. Astronauts wear gold -plated shields when they go outside spaceships in space. In conclusion, gold is treasured not only for its beauty but also its utility.

Pronoun + Repetition of key noun

Sometimes, greater cohesion can be achieved by using a pronoun followed by an appropriate key noun or synonym (a word with a similar meaning).

In the two main studies, no dramatic change was found in the rate of corrosion. could be due to several reasons. Generally speaking, crime rates in Europe have fallen over the past two years. has been the result of new approaches to punishment. When a group of school children was interviewed, the majority said they preferred their teachers to be humorous yet kind. However, were not as highly rated by teachers. |

Transitions are like traffic signals. They guide the reader from one idea to the next. They signal a range of relationships between sentences, such as comparison, contrast, example and result. Click here for a more comprehensive list of Transitions (Logical Organisers) .

Test yourself: How well do you understand transitions?

Which of the three alternatives should follow the transition or logical organiser in capital letters to complete the second sentence?

Using transitions/logical organisers

Improve the coherence of the following paragraph by adding transitions in the blank spaces. Use the italicised hint in brackets to help you choose an apporpriate transition for each blank. If you need to, review the list of Transitions (Logical Organisers) before you start.

First, CDs brought digital sound into people's homes. Then DVD technology brought digital sound and video and completely revolutionised the movie industry. Soon there will be 1. ( ) revolution: Blu-ray *BDs. A Blu-ray disc will have several advantages. 2. ( ), it has an enormous data storage capacity. A single-sided DVD can hold 4.7 gigabytes of information, about the size of an average 2-hour movie. A single-sided BD, 3. ( ) can hold up to 27 gigabytes, enough for 13 hours of standard video. A 4. ( ) advantage is that a BD can record, store, and play back high-definition video because of its larger capacity. A double-layer BD can store about 50 gigabytes, enough for 4.5 hours of high-definition video. The cost will be the same. 5. ( ), a BD has a higher data transfer rate - 36 megabits per second - than today's DVDs, which transfer at 10 megabits per second. 6. ( ), a BD can record 25 gigabytes of data in just over an hour and a half. 7. ( , because of their storage capacity and comparable cost, BDs will probably take over the market when they become widely available. (p.31). Text source: Oshima, A. and Hogue, A. (2008). 4th ed.). NY: Pearson Longman Ltd. |

Using transitions

Choose the most appropriate transition from the options given to complete the article:

There are three separate sources of hazards related to the use of nuclear reactions to supply us with energy. Firstly ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select14" ).html( document.getElementById( "select14" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); , the radioactive material must travel from its place of manufacture to the power station. Although ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select15" ).html( document.getElementById( "select15" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); the power stations themselves are solidly built, the containers used for the transport of the material are not. Unfortunately, there are normally only two methods of transport available, namely ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select16" ).html( document.getElementById( "select16" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); road or rail, and both of these involve close contact with the general public, since ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select17" ).html( document.getElementById( "select17" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); the routes are bound to pass near or through heavily-populated areas. Secondly ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select18" ).html( document.getElementById( "select18" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); , there is the problem of waste. All nuclear power stations produce wastes which in most cases will remain radioactive for thousands of years. It is impossible to de-activiate these wastes; consequently ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select19" ).html( document.getElementById( "select19" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); , they must be disposed of carefully. For example ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select20" ).html( document.getElementById( "select20" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); , they may be buried under the ground, dropped into disused mineshafts, or sunk in the sea. However ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select21" ).html( document.getElementById( "select21" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); , these methods do not solve the problem; they merely store it, since ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select22" ).html( document.getElementById( "select22" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); an earthquake could crack open the containers. Thirdly ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select23" ).html( document.getElementById( "select23" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); , there is the problem of accidental exposure due to a leak or an explosion at the power station. As with the other two hazards, this is extremely unlikely. Nevertheless ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select24" ).html( document.getElementById( "select24" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); it can happen. Separately, and during short periods, these three types of risk are no great cause for concern. Taken together, though ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select25" ).html( document.getElementById( "select25" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); , and especially over much longer periods, the probability of a disaster is extremely high. (p. 62). Text source: Coe, N., Rycroft, R., & Ernest, P. (1983). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

Overusing transitions

While the use of appropriate transitions can improve coherence (as the previous practice activity shows), it can also be counterproductive if transitions are overused. Use transitions carefully to enhance and clarify the logical connection between ideas in extended texts. Write a range of sentences and vary sentence openings.

Study the following examples:

: If people stopped drinking, they might be able to prevent the onset of liver disease. , governments permit the production and sale of alcohol. , they should help in preventing this disease. , government resources are limited. : If people stopped drinking, they might be able to prevent the onset of liver disease. Governments permit the production and sale of alcohol. They should help in preventing this disease. Government resources are limited.

If people stopped drinking, they might be able to prevent the onset of liver disease. The government should help in preventing this disease they permit the production and sale of alcohol. Government resources, , are limited. |

Identifying cohesive devices

1. Repetition of key noun

2. Repetition of key noun

3. Pronoun + Repetition

4. Repetition with synonym

5. Pronoun

6. Pronoun

7. Transition

8. Transition

9. Repetition of key noun

10. Pronoun

11. Pronoun + Repetition

Write the name of the cohesive device - pronoun , repetition or transition - in the space after each underlined word or phrase before the blank.

The Sinking of the Titanic

In 1912, the Titanic, the largest and best equipped transatlantic liner of pronoun ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select26" ).html( document.getElementById( "select26" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); time, hit an iceberg on pronoun ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select27" ).html( document.getElementById( "select27" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); first crossing from England to America and sank. Of the 2,235 parrengers and crew, only 718 survivived. Research has shown that a number of factors played an important part in the repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select28" ).html( document.getElementById( "select28" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); . transition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select29" ).html( document.getElementById( "select29" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); , the repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select30" ).html( document.getElementById( "select30" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); carried only sixteen lifeboats, with room for about 1,100 people. pronoun ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select31" ).html( document.getElementById( "select31" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); was clearly not enough for a ship of the repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select32" ).html( document.getElementById( "select32" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); size. transition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select33" ).html( document.getElementById( "select33" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); , the designer of the repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select34" ).html( document.getElementById( "select34" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); originally planned to equip the repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select35" ).html( document.getElementById( "select35" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); with forty-eight repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select36" ).html( document.getElementById( "select36" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); ; transition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select37" ).html( document.getElementById( "select37" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); , in order to reduce pronoun ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select38" ).html( document.getElementById( "select38" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); costs for building the repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select39" ).html( document.getElementById( "select39" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); , the owners of the repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select40" ).html( document.getElementById( "select40" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); decided to give pronoun ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select41" ).html( document.getElementById( "select41" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); only sixteen repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select42" ).html( document.getElementById( "select42" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); . A transition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select43" ).html( document.getElementById( "select43" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select44" ).html( document.getElementById( "select44" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); was that the repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select45" ).html( document.getElementById( "select45" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); crew were not given enough time to become familiar with the repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select46" ).html( document.getElementById( "select46" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); , especially with pronoun ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select47" ).html( document.getElementById( "select47" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); emergency equipment. transition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select48" ).html( document.getElementById( "select48" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); , many repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select49" ).html( document.getElementById( "select49" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); left the repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select50" ).html( document.getElementById( "select50" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); only half-full and many more people died than needed to. The transition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select51" ).html( document.getElementById( "select51" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select52" ).html( document.getElementById( "select52" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); in the repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select53" ).html( document.getElementById( "select53" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); was the behaviour of the repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select54" ).html( document.getElementById( "select54" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); officers on the night of the repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select55" ).html( document.getElementById( "select55" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); . In the twenty-four hours before the repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select56" ).html( document.getElementById( "select56" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); , pronoun ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select57" ).html( document.getElementById( "select57" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); received a number of warnings about repetition ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select58" ).html( document.getElementById( "select58" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); in the area, but pronoun ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select59" ).html( document.getElementById( "select59" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); took no precautions. pronoun ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); tmpAr.push( ' ' ); jQuery( "#select60" ).html( document.getElementById( "select60" ).innerHTML + tmpAr.join( '' )); did not change direction or even reduce speed. (p. 22). Source: Pakenham, K.J. (1998). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

Using cohesive devices - pronouns and repetition

Read through the text below and consider how you might use pronouns and repetition (either with a key noun or synonym) to replace the bolded expressions. Write your revised text in the submission box.

| Facebook did not invent social networking, but the company has fine-tuned into a science. When a newcomer logs in, the experience is designed to generate something Facebook calls the aha! moment. is an observable emotional connection, gleaned by videotaping the expressions of test users navigating for the first time. Facebook has developed a formula for the precise number of aha! moments users must have before are hooked. Company officials will not say exactly what that magic number is, but everything about Facebook is geared to reach as quickly as possible. So far, at least, Facebook has avoided the digital exoduses that beset predecessors, MySpace and Friendster. is partly because Facebook is so good at making indispensable. Losing Facebook hurts. Source: Fletcher, D. (2010, May 31). Friends without borders. , 21, 16-22. |

| Write the revised text here: |

Click here to view a suggested answer.

Suggested answer :

The Aha! Moment

Facebook did not invent social networking, but the company has fine-tuned it ( pronoun-first person ) into a science. When a newcomer logs in, the experience is designed to generate something Facebook calls the aha! moment. This ( pronoun-determiner ) is an observable emotional connection, gleaned by videotaping the expressions of test users navigating the site ( repetition with synonym ) for the first time. Facebook has developed a formula for the precise number of aha! moments users must have before they ( pronoun-third person ) are hooked. Company officials will not say exactly what that magic number is, but everything about the site ( repetition with synonym ) is geared to reach it as quickly as possible.

So far, at least, Facebook has avoided the digital exoduses that beset its ( pronoun-possessive ) predecessors, MySpace and Friendster. This is partly because Facebook is so good at making itself ( pronoun-reflexive ) indispensable. Losing Facebook hurts.

Cohesion between paragraphs

So far, we have looked at cohesion within paragraphs. In longer texts of several paragraphs, a combination of pronouns, transition and reptition can be used to maintain logical flow and connection between paragraphs.

The extract presented here consists of four paragraphs of an expository essay entitled Sustainable Development from a Historical Perspective: The Mayan Civilisation . Note how the bolded expressions at the start of the second, third and fourth paragraphs provide cohesive links to the paragraph preceding them.

Click to view Cohesion between paragraphs.

Sometimes known as parallel structures or balanced constructions, parallelism is the use of similar grammatical forms or sentence structures when listing or when comparing two or more items.

When used correctly, parallelism can improve the clarity of your writing.

): : The elderly residents enjoy many recreational activities: swimming, *read and *to garden. : The elderly residents enjoy many recreational activities: , , and .

: The academic conversation group consists of students from China, Japan, Korea and *some Germans. : The academic conversation group consists of students from , , , and

: This paper discusses the main features of the AST system, the functionalities, and *the system also has a number of limitations. : This paper discusses the , , and |

Parallelism in extended texts

The following excerpt from Bertrand Russell's famous prologue to his autobiography has some classic examples of parallelism:

: The computer is both fast and *it has reliability

: The computer is both and .

: The problem with electronic banking is neither the lack of security nor *the fact that you pay high interest rates.

: The problem with electronic banking is neither nor .

: The aim of the new law is not only to reduce the incidence of boy racing but also *setting up new standards for noise tolerance in the whole neighbourhood.

: The aim of the new law is not only ... but also new standards for noise tolerance in the whole neighbourhood.

Correcting faulty parallel constructions

Correct the faulty parallel constructions ( bold ) in the following sentences.

1. The researcher wanted to find out where the new immigrants came from and to talk about their future plans.

2. The earthquake victims were both concerned about water contamination and the slow response from the government also made them angry.

3. An ideal environment for studying includes good lighting, a spacious room, and the furniture must be comfortable.

4. Computers have changed the way people live, for their work, and how they use their leisure time.

5. Houses play an important role not only to provide a place to live, but also for giving a sense of security.

| Write your corrections here: |

Click here to view the suggested answers.

Suggested answers :

1 The researcher wanted to find out where the new immigrants came from and what their future plans were.

2. The earthquake victims were both concerned about water contamination and angry at the the slow response from the government.

3. An ideal environment for studying includes good lighting, a spacious room, and comfortable furniture.

4. Computers have changed the way people live, work, and use their leisure time.

5. Houses play an important role not only to provide a place to live, but also to give a sense of security.

Recognising parallel structures

Read through the text and underline the examples of parallel structures (there are five of them). If you can, write the type of grammatical form used in each case. The first one has been done for you as an example.

Write out the entire paragraph in the submission box if it is easier.

Now you try :

Not only have geneticists found beneficial uses of genetically engineered organisms in agriculture, but they have also found ( 1. paired conjunctions ) useful ways to use these organisms advantageously in the larger environment. According to the Monsanto company, a leader in genetic engineering research, recombinant DNA techniques may provide scientists with new ways to clean up the environment and with more efficient methods of producing chemicals. By using genetically engineered organisms, scientists have been able to produce natural gas. This process will decrease society's dependence on the environment and will reduce the rate at which natural resources are depleted. In other processes, genetically engineered bacteria are being used both to extract metals from their geological setting and to speed the breakup of complex petroleum mixtures which will help to clean up oil spills. (p. 523).

Source: Rosen, L.J. (1995). Discovery and commitment: A guide for college writers. Mass.: Allyn and Bacon.

| Write your answer here. |

Click here to view the answer to the question above

| « | » |

- Select text to style.

- Paste youtube/vimeo url to add embeded video.

- Click + sign or type / at the beginning of line to show plugins selection.

- Use image plugin to upload or copy/paste image searched from internet or paste in snip/sketched image from snap tool

Pasco-Hernando State College

- Unity and Coherence in Essays

- The Writing Process

- Paragraphs and Essays

- Proving the Thesis/Critical Thinking

- Appropriate Language

Test Yourself

- Essay Organization Quiz

- Sample Essay - Fairies

- Sample Essay - Modern Technology

Related Pages

- Proving the Thesis

Unity is the idea that all parts of the writing work to achieve the same goal: proving the thesis. Just as the content of a paragraph should focus on a topic sentence, the content of an essay must focus on the thesis. The introduction paragraph introduces the thesis, the body paragraphs each have a proof point (topic sentence) with content that proves the thesis, and the concluding paragraph sums up the proof and restates the thesis. Extraneous information in any part of the essay that is not related to the thesis is distracting and takes away from the strength of proving the thesis.

An essay must have coherence. The sentences must flow smoothly and logically from one to the next as they support the purpose of each paragraph in proving the thesis.

Just as the last sentence in a paragraph must connect back to the topic sentence of the paragraph, the last paragraph of the essay should connect back to the thesis by reviewing the proof and restating the thesis.

Example of Essay with Problems of Unity and Coherence

Here is an example of a brief essay that includes a paragraph that does not support the thesis “Many people are changing their diets to be healthier.”

People are concerned about pesticides, steroids, and antibiotics in the food they eat. Many now shop for organic foods since they don’t have the pesticides used in conventionally grown food. Meat from chicken and cows that are not given steroids or antibiotics are gaining popularity even though they are much more expensive. More and more, people are eliminating pesticides, steroids, and antibiotics from their diets. Eating healthier also is beneficial to the environment since there are less pesticides poisoning the earth. Pesticides getting into the waterways is creating a problem with drinking water. Historically, safe drinking water has been a problem. It is believed the Ancient Egyptians drank beer since the water was not safe to drink. Brewing beer killed the harmful organisms and bacteria in the water from the Nile. There is a growing concern about eating genetically modified foods, and people are opting for non-GMO diets. Some people say there are more allergic reactions and other health problems resulting from these foods. Others are concerned because there are no long-term studies that clearly show no adverse health effects such as cancers or other illnesses. Avoiding GMO food is another way people are eating healthier food.

See how just one paragraph can take away from the effectiveness of the essay in showing how people are changing to healthier food since unity and coherence are affected. There is no longer unity among all the paragraphs. The thought pattern is disjointed and the essay loses its coherence.

Transitions and Logical Flow of Ideas

Transitions are words, groups of words, or sentences that connect one sentence to another or one paragraph to another.

They promote a logical flow from one idea to the next and overall unity and coherence.

While transitions are not needed in every sentence or at the end of every paragraph, they are missed when they are omitted since the flow of thoughts becomes disjointed or even confusing.

There are different types of transitions:

- Time – before, after, during, in the meantime, nowadays

- Space – over, around, under

- Examples – for instance, one example is

- Comparison – on the other hand, the opposing view

- Consequence – as a result, subsequently

These are just a few examples. The idea is to paint a clear, logical connection between sentences and between paragraphs.

- Printer-friendly version

Definition of Coherence

Types of coherence, examples of coherence in literature, example #1: one man’s meat (by e.b. white).

“Scientific agriculture, however sound in principle, often seems strangely unrelated to, and unaware of, the vital, grueling job of making a living by farming. Farmers sense this quality in it as they study their bulletins, just as a poor man senses in a rich man an incomprehension of his own problems. The farmer of today knows, for example, that manure loses some of its value when exposed to the weather … But he knows also that to make hay he needs settled weather – better weather than you usually get in June.”

This is a global level coherent text passage in which White has wonderfully unified the sentences to make it a whole. He has started the passage with a general topic, scientific agriculture, but moved it to a specific text about farmers and their roles.

Example #2: A Tale of Two Cities (by Charles Dickens)

“The wine was red wine, and had stained the ground of the narrow street in the suburb of Saint Antoine, in Paris, where it was spilled. It had stained many hands, too, and many faces, and many naked feet, and many wooden shoes. The hands of the man who sawed the wood, left red marks on the billets; and the forehead of the woman who nursed her baby, was stained with the stain of the old rag she wound about her head again. Those who had been greedy with the staves of the cask … scrawled upon a wall with his finger dipped in muddy wine-lees—BLOOD.”

Example #3: Animal Farm (by George Orwell)

“ Now , comrades, what is the nature of this life of ours? Let us face it: our lives are miserable, laborious, and short. We are born, we are given just so much food as will keep the breath in our bodies, and those of us who are capable of it are forced to work to the last atom of our strength … “No animal in England knows the meaning of happiness or leisure after he is a year old. The life of an animal is misery and slavery: that is the plain truth.”

Through the speech of the Old Major, Orwell starts the passage about the miserable nature of the life of animals on the animal farm , and then he inspires them to think about how to safeguard their interests on the farm. The entire paragraph is an example of coherent speech.

Example #4: Unpopular Essays (by Bertrand Russell)

“The word “philosophy” is one of which the meaning is by no means fixed. Like the word “religion,” it has one sense when used to describe certain features of historical cultures, and another when used to denote a study or an attitude of mind which is considered desirable in the present day. Philosophy, as pursued in the universities of the Western democratic world, is, at least in intention, part of the pursuit of knowledge, aiming at the same kind of detachment as is sought in science …”

Coherence links the sentences of a work with one another. This may be done with paragraphs, making sure that each statement logically connects with the one preceding it, making the text easier for the readers to understand and follow. Also, ordering thoughts in a sequence helps the reader to move from one point to the next smoothly. As all of the sentences relate back to the topic, the thoughts and ideas flow smoothly.

Post navigation

- I nfographics

- Show AWL words

- Subscribe to newsletter

- What is academic writing?

- Academic Style

- What is the writing process?

- Understanding the title

- Brainstorming

- Researching

- First draft

- Proofreading

- Report writing

- Compare & contrast

- Cause & effect

- Problem-solution

- Classification

- Essay structure

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Book review

- Research proposal

- Thesis/dissertation

What is cohesion?

- Cohesion vs coherence

Transition signals

- What are references?

- In-text citations

- Reference sections

- Reporting verbs

- Band descriptors

Show AWL words on this page.

Levels 1-5: grey Levels 6-10: orange

Show sorted lists of these words.

| --> |

Any words you don't know? Look them up in the website's built-in dictionary .

|

|

Choose a dictionary . Wordnet OPTED both

Cohesion How to make texts stick together

Cohesion and coherence are important features of academic writing. They are one of the features tested in exams of academic English, including the IELTS test and the TOEFL test . This page gives information on what cohesion is and how to achieve good cohesion. It also explains the difference between cohesion and coherence , and how to achieve good coherence. There is also an example essay to highlight the main features of cohesion mentioned in this section, as well as some exercises to help you practise.

For another look at the same content, check out YouTube or Youku , or the infographic .

It is important for the parts of a written text to be connected together. Another word for this is cohesion . This word comes from the verb cohere , which means 'to stick together'. Cohesion is therefore related to ensuring that the words and sentences you use stick together.

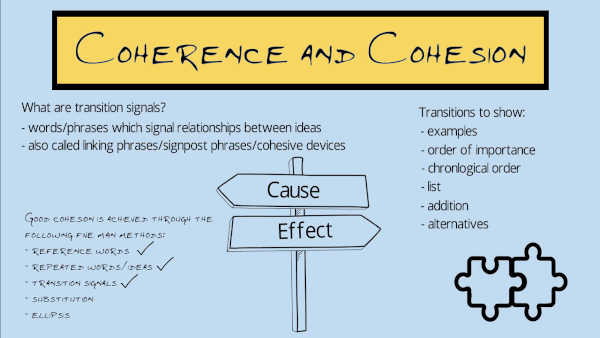

Good cohesion is achieved through the following five main methods, each of which is described in more detail below:

- repeated words/ideas

- reference words

- transition signals

- substitution

Two other ways in which cohesion is achieved in a text, which are covered less frequently in academic English courses, are shell nouns and thematic development . These are also considered below.

Repeated words/ideas

Check out the cohesion infographic »

One way to achieve cohesion is to repeat words, or to repeat ideas using different words (synonyms). Study the following example. Repeated words (or synonyms) are shown in bold.

Cohesion is an important feature of academic writing . It can help ensure that your writing coheres or 'sticks together', which will make it easier for the reader to follow the main ideas in your essay or report . You can achieve good cohesion by paying attention to five important features . The first of these is repeated words. The second key feature is reference words. The third one is transition signals. The fourth is substitution. The final important aspect is ellipsis.

In this example, the word cohesion is used several times, including as a verb ( coheres ). It is important, in academic writing, to avoid too much repetition, so using different word forms or synonyms is common. The word writing is also used several times, including the phrase essay or report , which is a synonym for writing . The words important features are also repeated, again using synonyms: key feature , important aspect .

Reference words

Reference words are words which are used to refer to something which is mentioned elsewhere in the text, usually in a preceding sentence. The most common type is pronouns, such as 'it' or 'this' or 'these'. Study the previous example again. This time, the reference words are shown in bold.

Cohesion is an important feature of academic writing. It can help ensure that your writing coheres or 'sticks together', which will make it easier for the reader to follow the main ideas in your essay or report. You can achieve good cohesion by paying attention to five important features. The first of these is repeated words. The second key feature is reference words. The third one is transition signals. The fourth is substitution. The final important aspect is ellipsis.

The words it , which and these are reference words. The first two of these, it and which , both refer to 'cohesion' used in the preceding sentence. The final example, these , refers to 'important features', again used in the sentence that precedes it.

Transition signals, also called cohesive devices or linking words, are words or phrases which show the relationship between ideas. There are many different types, the most common of which are explained in the next section on transition signals . Some examples of transition signals are:

- for example - used to give examples

- in contrast - used to show a contrasting or opposite idea

- first - used to show the first item in a list

- as a result - used to show a result or effect

Study the previous example again. This time, the transition signals are shown in bold. Here the transition signals simply give a list, relating to the five important features: first , second , third , fourth , and final .

Substitution

Substitution means using one or more words to replace (substitute) for one or more words used earlier in the text. Grammatically, it is similar to reference words, the main difference being that substitution is usually limited to the clause which follows the word(s) being substituted, whereas reference words can refer to something far back in the text. The most common words used for substitution are one , so , and auxiliary verbs such as do, have and be . The following is an example.

- Drinking alcohol before driving is illegal in many countries, since doing so can seriously impair one's ability to drive safely.

In this sentence, the phrase 'doing so' substitutes for the phrase 'drinking alcohol before driving' which appears at the beginning of the sentence.

Below is the example used throughout this section. There is just one example of substitution: the word one , which substitutes for the phrase 'important features'.

Ellipsis means leaving out one or more words, because the meaning is clear from the context. Ellipsis is sometimes called substitution by zero , since essentially one or more words are substituted with no word taking their place.

Below is the example passage again. There is one example of ellipsis: the phrase 'The fourth is', which means 'The fourth [important feature] is', so the words 'important feature' have been omitted.

Shell nouns

Shell nouns are abstract nouns which summarise the meaning of preceding or succeeding information. This summarising helps to generate cohesion. Shell nouns may also be called carrier nouns , signalling nouns , or anaphoric nouns . Examples are: approach, aspect, category, challenge, change, characteristics, class, difficulty, effect, event, fact, factor, feature, form, issue, manner, method, problem, process, purpose, reason, result, stage, subject, system, task, tendency, trend, and type . They are often used with pronouns 'this', 'these', 'that' or 'those', or with the definite article 'the'. For example:

- Virus transmission can be reduced via frequent washing of hands, use of face masks, and isolation of infected individuals. These methods , however, are not completely effective and transmission may still occur, especially among health workers who have close contact with infected individuals.

- An increasing number of overseas students are attending university in the UK. This trend has led to increased support networks for overseas students.

In the example passage used throughout this section, the word features serves as a shell noun, summarising the information later in the passage.

Cohesion is an important feature of academic writing. It can help ensure that your writing coheres or 'sticks together', which will make it easier for the reader to follow the main ideas in your essay or report. You can achieve good cohesion by paying attention to five important features . The first of these is repeated words. The second key feature is reference words. The third one is transition signals. The fourth is substitution. The final important aspect is ellipsis.

Thematic development

Cohesion can also be achieved by thematic development. The term theme refers to the first element of a sentence or clause. The development of the theme in the rest of the sentence is called the rheme . It is common for the rheme of one sentence to form the theme of the next sentence; this type of organisation is often referred to as given-to-new structure, and helps to make writing cohere.

Consider the following short passage, which is an extension of the first example above.

- Virus transmission can be reduced via frequent washing of hands, use of face masks, and isolation of infected individuals. These methods, however, are not completely effective and transmission may still occur, especially among health workers who have close contact with infected individuals. It is important for such health workers to pay particular attention to transmission methods and undergo regular screening.

Here we have the following pattern:

- Virus transmission [ theme ]

- can be reduced via frequent washing of hands, use of face masks, and isolation of infected individuals [ rheme ]

- These methods [ theme = rheme of preceding sentence ]

- are not completely effective and transmission may still occur, especially among health workers who have close contact with infected individuals [ rheme ]

- health workers [ theme, contained in rheme of preceding sentence ]

- [need to] to pay particular attention to transmission methods and undergo regular screening [ rheme ]

Cohesion vs. coherence

The words 'cohesion' and 'coherence' are often used together with a similar meaning, which relates to how a text joins together to make a unified whole. Although they are similar, they are not the same. Cohesion relates to the micro level of the text, i.e. the words and sentences and how they join together. Coherence , in contrast, relates to the organisation and connection of ideas and whether they can be understood by the reader, and as such is concerned with the macro level features of a text, such as topic sentences , thesis statement , the summary in the concluding paragraph (dealt with in the essay structure section), and other 'bigger' features including headings such as those used in reports .

Coherence can be improved by using an outline before writing (or a reverse outline , which is an outline written after the writing is finished), to check that the ideas are logical and well organised. Asking a peer to check the writing to see if it makes sense, i.e. peer feedback , is another way to help improve coherence in your writing.

Example essay

Below is an example essay. It is the one used in the persuasion essay section. Click on the different areas (in the shaded boxes to the right) to highlight the different cohesive aspects in this essay, i.e. repeated words/ideas, reference words, transition signals, substitution and ellipsis.

Title: Consider whether human activity has made the world a better place.

History shows that human beings have come a long way from where they started. They have developed new technologies which means that everybody can enjoy luxuries they never previously imagined. However , the technologies that are temporarily making this world a better place to live could well prove to be an ultimate disaster due to , among other things, the creation of nuclear weapons , increasing pollution , and loss of animal species . The biggest threat to the earth caused by modern human activity comes from the creation of nuclear weapons . Although it cannot be denied that countries have to defend themselves, the kind of weapons that some of them currently possess are far in excess of what is needed for defence . If these [nuclear] weapons were used, they could lead to the destruction of the entire planet . Another harm caused by human activity to this earth is pollution . People have become reliant on modern technology, which can have adverse effects on the environment . For example , reliance on cars causes air and noise pollution . Even seemingly innocent devices, such as computers and mobile phones, use electricity, most of which is produced from coal-burning power stations, which further adds to environmental pollution . If we do not curb our direct and indirect use of fossil fuels, the harm to the environment may be catastrophic. Animals are an important feature of this earth and the past decades have witnessed the extinction of a considerable number of animal species . This is the consequence of human encroachment on wildlife habitats, for example deforestation to expand cities. Some may argue that such loss of [animal] species is natural and has occurred throughout earth's history. However , the current rate of [animal] species loss far exceeds normal levels [of animal species loss] , and is threatening to become a mass extinction event. In summary , there is no doubt that current human activities such as the creation of nuclear weapons , pollution , and destruction of wildlife , are harmful to the earth . It is important for us to see not only the short-term effects of our actions, but their long-term ones as well. Otherwise , human activities will be just another step towards destruction .

Aktas, R.N. and Cortes, V. (2008), 'Shell nouns as cohesive devices in published and ESL student writing', Journal of English for Academic Purposes , 7 (2008) 3-14.

Alexander, O., Argent, S. and Spencer, J. (2008) EAP Essentials: A teacher's guide to principles and practice . Reading: Garnet Publishing Ltd.

Gray, B. (2010) 'On the use of demonstrative pronouns and determiners as cohesive devices: A focus on sentence-initial this/these in academic prose', Journal of English for Academic Purposes , 9 (2010) 167-183.

Halliday, M. A. K., and Hasan, R. (1976). Cohesion in English . London: Longman.

Hinkel, E. (2004). Teaching Academic ESL Writing: Practical Techniques in Vocabulary and Grammar . Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc Publishers.

Hyland, K. (2006) English for Academic Purposes: An advanced resource book . Abingdon: Routledge.

Thornbury, S. (2005) Beyond the Sentence: Introducing discourse analysis . Oxford: Macmillan Education.

GET FREE EBOOK

Like the website? Try the books. Enter your email to receive a free sample from Academic Writing Genres .

Below is a checklist for essay cohesion and coherence. Use it to check your own writing, or get a peer (another student) to help you.

| There is good use of (including synonyms). | ||

| There is good use of (e.g. 'it', 'this', 'these'). | ||

| There is good use of (e.g. 'for example', 'in contrast'). | ||

| is used, where appropriate. | ||

| is used, if necessary. | ||

| Other aspects of cohesion are used appropriately, i.e. (e.g. 'effect', 'trend') and | ||

| There is good via the thesis statement, topic sentences and summary. |

Next section

Find out more about transition signals in the next section.

- Transitions

Previous section

Go back to the previous section about paraphrasing .

- Paraphrasing

Exercises & Activities Some ways to practise this area of EAP

You need to login to view the exercises. If you do not already have an account, you can register for free.

- Register

- Forgot password

- Resend activiation email

Author: Sheldon Smith ‖ Last modified: 03 February 2022.

Sheldon Smith is the founder and editor of EAPFoundation.com. He has been teaching English for Academic Purposes since 2004. Find out more about him in the about section and connect with him on Twitter , Facebook and LinkedIn .

Compare & contrast essays examine the similarities of two or more objects, and the differences.

Cause & effect essays consider the reasons (or causes) for something, then discuss the results (or effects).

Discussion essays require you to examine both sides of a situation and to conclude by saying which side you favour.

Problem-solution essays are a sub-type of SPSE essays (Situation, Problem, Solution, Evaluation).

Transition signals are useful in achieving good cohesion and coherence in your writing.

Reporting verbs are used to link your in-text citations to the information cited.

- WRITING SKILLS

Coherence in Writing

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Writing Skills:

- A - Z List of Writing Skills

The Essentials of Writing

- Common Mistakes in Writing

- Introduction to Grammar

- Improving Your Grammar

- Active and Passive Voice

- Punctuation

- Clarity in Writing

- Writing Concisely

- Gender Neutral Language

- Figurative Language

- When to Use Capital Letters

- Using Plain English

- Writing in UK and US English

- Understanding (and Avoiding) Clichés

- The Importance of Structure

- Know Your Audience

- Know Your Medium

- Formal and Informal Writing Styles

- Note-Taking from Reading

- Note-Taking for Verbal Exchanges

- Creative Writing

- Top Tips for Writing Fiction

- Writer's Voice

- Writing for Children

- Writing for Pleasure

- Writing for the Internet

- Journalistic Writing

- Technical Writing

- Academic Writing

- Editing and Proofreading

Writing Specific Documents

- Writing a CV or Résumé

- Writing a Covering Letter

- Writing a Personal Statement

- Writing Reviews

- Using LinkedIn Effectively

- Business Writing

- Study Skills

- Writing Your Dissertation or Thesis

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Have you ever read a piece of writing and wondered what point the writer was trying to make? If so, that piece of writing probably lacked coherence. Coherence is an important aspect of good writing—as important as good grammar or spelling. However, it is also rather harder to learn how to do it, because it is not a matter of simple rules.

Coherent writing moves smoothly between ideas. It guides the reader through an argument or series of points using signposts and connectors. It generally has a clear structure and consistent tone, with little or no repetition. Coherent writing feels planned —usually because it is. This page provides some tips to help you to develop your ability to write coherently.

Defining Coherence

Dictionary definition of coherence

cohere , v. to stick together, to be consistent, to fit together in a consistent, orderly whole.

coherence , a sticking together, consistency.

Source: Chambers English Dictionary, 1989 edition.

The dictionary definition of coherence is clear enough—but what does that mean in practical terms for writers?

Once you have achieved coherence in your writing, you will find that:

Your sentences and ideas are connected and flow together;

Readers can move easily through the text from one sentence, paragraph or idea to the next; and

Readers will be able to follow the ideas and main points of the text.

On the other hand, a text that is NOT coherent jumps between ideas without making clear connections between them. It is often hard to follow the argument. Readers may find themselves unclear about the point of particular paragraphs or even whole sections. There may be odd sentences that do not fit well with the previous or following sentence, or paragraphs that repeat earlier ideas.

All these issues provide pointers for how to develop coherence.

Elements of Coherence

There are several different elements that contribute to coherence, or are closely linked to the concept.

They include:

Cohesion , or whether ideas are linked within and between sentences.

Unity , or the extent to which a sentence, paragraph or section focuses on a single idea or group or ideas. In any given paragraph, every sentence should be relevant to a single focus.

A joint effort

Together, cohesion and unity mean that sentences and paragraphs are connected around a central theme.

- Flow , or how the reader is led through the text. Some of this is about the ordering of ideas, but it also takes into account issues like phrasing, rhythm and style. Some people define flow as the quality that makes writing engaging and easy to read.

Levels of Coherence

We can consider coherence at several different levels. These include:

Within sentences. A sentence is coherent when it flows naturally, and uses correct grammar , spelling and punctuation . Coherence also includes the use of the most appropriate words, and avoidance of redundancy.

Between sentences . Coherence between sentences means that each sentence flows logically and naturally from the previous one. Connections are made between them so that readers can see the flow of ideas, and how each sentence is linked to the previous one.

Within paragraphs . This is a logical extension of coherence between sentences. Coherence within a paragraph means that the sentences within the paragraph work together as a whole to present a complete thesis or idea.

Why single-sentence paragraphs don’t work

This definition of ‘within paragraph’ coherence explains why you should (almost) never use single-sentence paragraphs. A single sentence is (almost) never going to be able to provide a complete summary of your thesis or idea.

Between paragraphs . For most pieces of writing, you will also need to consider how the paragraphs fit together. Each paragraph covers an idea or thesis—and must then be connected logically to the next paragraph, so that your overall thesis is built step-by-step.

Between subsections or sections . This final level of coherence is only really important for longer documents. You must create a logical flow between different sections, to guide your reader from one to the next so that they can follow the development of your ideas.

Techniques to Improve Coherence

The first step to improving coherence is to plan your writing in advance.

Decide on the main point that you want to make, and the ideas that will lead your reader towards your point. It is also helpful to consider your planned audience, and what they want from your text.

There is more about this in our page on Know Your Audience . You may also find it helpful to read our page on Know Your Medium , to check whether there is anything about your publishing medium that you need to consider ahead of starting to write.

There are some techniques that you can use to help improve coherence within your writing. These include:

Using transitional expressions and phrases to signal connections

Words and phrases like ‘however’, ‘because’, ‘therefore’, ‘additionally’, and ‘on the one hand... on the other’ can be used to signal connections between sentences and paragraphs.

WARNING! Real connections needed!

Transitional phrases and words should only be used where the ideas really are connected.

Just inserting transitional expressions will not connect your ideas. Instead, you need to create a reasonable progression of ideas through a paragraph or section.

You also need to use transitional expressions sparingly. Not all ideas need an obvious link—and sometimes putting one in can seem awkward and contrived.

Using repeating forms or parallel structures to emphasise links between ideas

Generally speaking, repetition of words and phrases is unadvisable.

However, used sparingly, you may be able to harness repetition as a way to signal connections between sentences or ideas.

For example, many research papers have a section setting out the limitations of the study. These limitations can often be quite diverse, which makes for a rather disjointed section. To overcome this issue, writers often use the form ‘First... Second... Finally...’ to demonstrate the links between the disparate ideas.

Using pronouns and synonyms to eliminate unnecessary repetition

Repetition is often the enemy of coherence because it interrupts your movement through the writing. You tend to get distracted by the repeated words, and lose the thread of the argument or idea.

Pronouns and synonyms are a good way to avoid repeating words and phrases. However, care is needed when using them, to avoid ambiguity. It is advisable NOT to use pronouns following a sentence with two elements that might take the same pronoun.

For example:

John was sure that Tom was wrong. He had made the same argument last week.

Who made the same argument last week? John or Tom?

It is better to use at least one name again than create ambiguity.

TOP TIP! Come back later

It is often hard to detect ambiguity in your own writing because you know what you wanted to say.

It is therefore a good idea to leave any piece of writing overnight, and read it again in the morning. This will often identify problems such as ambiguous pronouns, and give you a chance to revise them.

Revisit, Revise and Review

Alongside planning, the single most important thing that you can do to improve the coherence of a piece of writing is to review and revise it with the reader’s needs in mind.

When you have finished a piece of writing, put it aside for a while. Overnight is ideal, but longer is fine. Once you have had a chance to forget precisely what you meant, read it over again as if you were coming to it for the first time.

As you start to read, consider the focus of your text: the main point that you want to make.

With that in mind, consciously examine whether the ideas flow clearly through your sentences, paragraphs and sections. Can the reader grasp your argument and follow it through the text? Is there an obvious conclusion?

While you are reading, you should also consider whether there are any very long sentences. If so, shorten them, using transitional words or phrases to link them together effectively. This will make your writing easier to read, and it will naturally flow better.

A Final Thought

It is not always easy to know how to create more coherent writing.

The best way to do so is to plan your writing, and then review it carefully. You should particularly consider your focus, and your readers’ needs. In doing so, you may find it helpful to use some of the techniques described on this page—but they will not, in themselves, be sufficient without the planning and review.

Continue to: Writing Concisely Using Plain English

See also: The Importance of Structure in Writing Editing and Proofreading Copywriting

Cohesion And Coherence In Essay Writing

Table of contents, introduction, definitions cohesion and coherence, what is coherence, what is cohesion.

If the elements of a text are cohesive, they are united and work together or fit well together.

How to Achieve Cohesion And Coherence In Essay Writing

Lexical cohesion, grammatical cohesion, substitutions, conjunctions transition words, cohesive but not coherent texts.

The player threw the ball toward the goalkeeper. Balls are used in many sports. Most balls are spheres, but American football is an ellipsoid. Fortunately, the goalkeeper jumped to catch the ball. The crossbar in the soccer game is made of iron. The goalkeeper was standing there.

How to write a coherent essay?

1. start with an outline, 2. structure your essay.

| Parts of the essay | Content |

|---|---|

| Introduction | Introduces the topic. Provides background information Presents the thesis statement of the essay |

| Body | The body of the essay is made up of several paragraphs depending on the complexity of your argument and the points you want to discuss. Each paragraph discusses one main point. Each paragraph includes a topic sentence, supporting details, and a concluding sentence. All paragraphs must relate to the thesis. |

| Conclusion | The conclusion summarizes the main points of the essay. It must not include new ideas. It draws a final decision or judgment about the issues you have been discussing. May connect the essay to larger topics or areas of further study. |

3. Structure your paragraphs

4. relevance to the main topic, 5. stick to the purpose of the type of essay you’re-writing, 6. use cohesive devices and signposting phrases.

| Cohesive device | Examples |

|---|---|

| Lexical | Repetition. Synonymy. Antonymy. Hyponymy. Meronymy. |

| Grammatical | Anaphora. Cataphora. Ellipsis. Substitutions. Conjunctions and transition words. |

What is signposting in writing?

Essay signposting phrases.

| Signposting | Functions | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Transition words | Expressing addition | in addition – as well as – moreover – what is more… |

| Expressing contrast | however – yet – nevertheless – nonetheless – on the contrary – whereas… | |

| Expressing cause and effect | consequently – as a consequence – as a result – therefore… | |

| Expressing purpose | in order to – in order not to – so as to… | |

| Summarizing | in conclusion – to conclude – to sum up | |

| Other signposting expressions | To introduce the essay | – This essay aims at… – This essay will be concerned with… – It shall be argued in this essay… – This essay will focus on… |

| To introduce a new idea | – Having established…, it is possible now to consider… – … is one key issue; another of equal importance is… – Also of significant importance is the issue of… – With regard to… – With respect to… – Firstly, … – Secondly, … – Finally, … | |

| To illustrate something | – One aspect that illustrates … is … – An example of… – …can be identified as… – The current debate about… illustrates – This highlights… | |

| To be more specific and emphasize a point | – Importantly, – Indeed, – In fact, – More importantly, – It is also important to highlight – In particular, In relation to, More specifically, With respect to, In terms of | |

| Changing direction | – To get back to the topic of this paper, … – Speaking of…, … – That reminds me of… – That brings to mind… – On a happier/sad note, … – Another point to consider is … | |

| Comparing | – In comparison, … – Compared to… – Similarly, … – Likewise,… – Conversely – In contrast, … – On the one hand, … – On the other hand, … | |

| Going into more detail on a point | – In particular… – Specifically… – Concentrating on … – By focusing on …. in more detail, it is possible… to… – To be more precise … | |

| Rephrasing | – In other words, … – To put it simply, … – That is to say… – To put it differently, … – To rephrase it, … – In plain English, … | |

| Reintroducing a topic | – As discussed/explained earlier, … – The earlier discussion on… can be developed further here, … – As stated previously, … – As noted above,… | |

| Introducing an opposing/alternative view | – An alternative perspective is given by… who suggests/argues that… – This conflicts with the view held by… – Alternatively, … | |

| Concluding | – It could be concluded that… – From this, it can be concluded that… – The evidence shows that… – In conclusion,… -In summary, … |

7. Draft, revise, and edit

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write Coherently

I. What is Coherence?

Coherence describes the way anything, such as an argument (or part of an argument) “hangs together.” If something has coherence, its parts are well-connected and all heading in the same direction. Without coherence, a discussion may not make sense or may be difficult for the audience to follow. It’s an extremely important quality of formal writing.

Coherence is relevant to every level of organization, from the sentence level up to the complete argument. However, we’ll be focused on the paragraph level in this article. That’s because:

- Sentence-level coherence is a matter of grammar, and it would take too long to explain all the features of coherent grammar.

- Most people can already write a fairly coherent sentence, even if their grammar is not perfect.

- When you write coherent paragraphs, the argument as a whole will usually seem coherent to your readers.

Although coherence is primarily a feature of arguments, you may also hear people talk about the “coherence” of a story, poem, etc. However, in this context the term is extremely vague, so we’ll focus on formal essays for the sake of simplicity.

Coherence is, in the end, a matter of perception. This means it’s a completely subjective judgement. A piece of writing is coherent if and only if the reader thinks it is.

II. Examples of Coherence

There are many distinct features that help create a sense of coherence. Let’s look at an extended example and go through some of the features that make it seem coherent. Most people would agree that this is a fairly coherent paragraph:

Credit cards are convenient , but dangerous . People often get them in order to make large purchases easily without saving up lots of money in advance. This is especially helpful for purchases like cars, kitchen appliances, etc., that you may need to get without delay . However, this convenience comes at a high price : interest rates. The more money you put on your credit card, the more the bank or credit union will charge you for that convenience . If you’re not careful, credit card debt can quickly break the bank and leave you in very dire economic circumstances!

- Topic Sentence . The paragraph starts with a very clear, declarative topic sentence, and the rest of the paragraph follows that sentence. Everything in the paragraph is tied back to the statement in the beginning.

- Key terms . The term “credit card” appears repeatedly in this short paragraph. This signals the reader that the whole paragraph is about the subject of credit cards. Similarly, the word convenience (and related words) are also peppered throughout. In addition, the key term “ danger ” appears in the topic sentence and is then explained fully as the paragraph goes on.

- Defined terms . For most readers, the terms in this paragraph will be quite clear and will not need to be defined. Some readers, however, might not understand the term “interest rates,” and they would need an explanation. To these readers, the paragraph will seem less coherent !

Clear transitions . Each sentence flows into the next quite easily, and readers can follow the line of logic without too much effort.

III. The Importance of Coherence

Say you’re reading a piece of academic writing – maybe a textbook. As you read, you find yourself drifting off, having to read the same sentence over and over before you understand it. Maybe, after a while, you get frustrated and give up on the chapter. What happened?

Nine times out of ten, this is a symptom of incoherence. Your brain is unable to find a unified argument or narrative in the book. This may become frustrating and often happens when a book is above your current level of understanding. To someone else, the writing might seem perfectly coherent, because they understand the concepts involved. But from your perspective, the chapter seems incoherent. And as a result, you don’t get as much out of it as you otherwise would.

How can you avoid this in your own writing? How can you make sure that readers don’t misunderstand you (or just give up altogether)? The answer is to work on coherent writing. Coherence is perhaps the most important feature of argumentative writing. Without it, everything falls apart. If an argument is not coherent, it doesn’t matter how good the evidence is, or how beautiful the writing is: an incoherent argument will never persuade anyone or even hold their attention.

V. Examples in Literature and Scholarship