Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Discrimination — Mexican-American Reflections

Mexican-american Reflections

- Categories: Discrimination

About this sample

Words: 1083 |

Published: Mar 25, 2024

Words: 1083 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 774 words

1 pages / 489 words

3 pages / 1171 words

4 pages / 2004 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Discrimination

Colorism, a form of discrimination based on skin color, has a long and complex history that can be traced back to ancient civilizations. Throughout the years, colorism has evolved and taken different forms, impacting [...]

In today's competitive job market, companies often prioritize the appearance and image of their employees as a part of their brand strategy. This practice, commonly known as "going for the look," involves hiring individuals [...]

Media exposure influences attitudes and behaviors towards out-groups. Barlow and Sibley (2018) suggest that the media can promote pro-social behaviors and reduce racist behaviors. Media characters can provide viewers with [...]

In Raymond Carver's short story "Cathedral," the author effectively uses an unlikely scenario - a casual interaction between the narrator and a blind man - to comment on racial discrimination, prejudices, and stereotypes. The [...]

Cultural encounters have long been a significant aspect of human history, shaping societies and identities through the exchange of ideas, beliefs, and practices. From ancient trade routes to modern globalization, these [...]

Discrimination is a disgusting practice that has been around for many years. The culture and bad teaching have kept this unfair act of exclusionary favor of one group over another alive by means of unchanging learned behaviors, [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

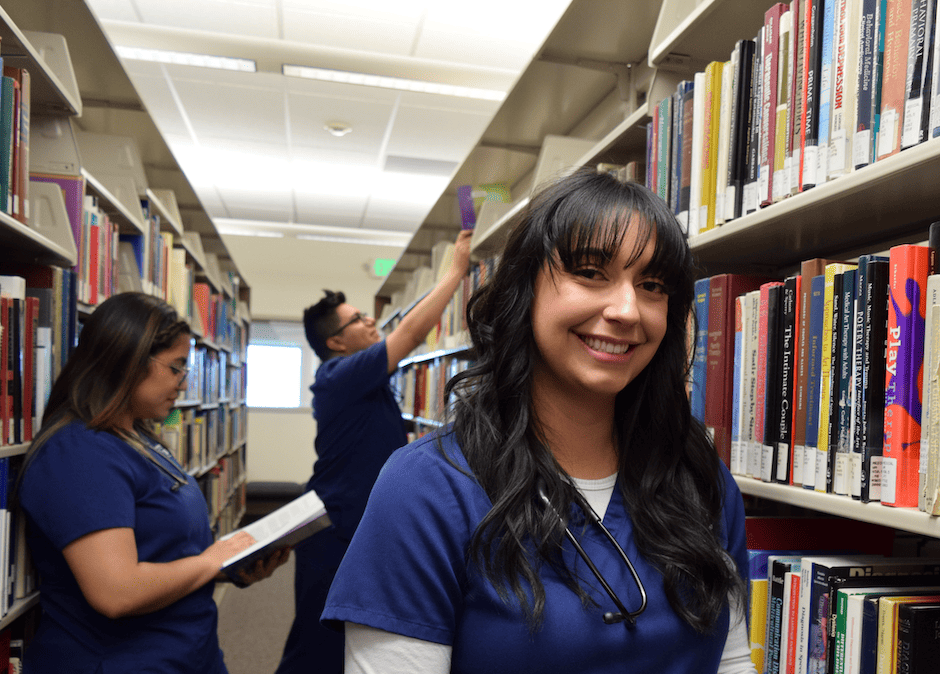

Being Latina and the struggle of the dualities of two worlds

Reflections on why our identities can help create a better world for all of us.

A few days ago, I attended a Zoom presentation organized by ASUN entitled “What does it mean to be Latinx?” Every time I witness the complexity of identities in the Latinx community in the United States, I am amazed. Amazed that we are always perceived as a homogenous group, when in reality, we couldn’t come from more different backgrounds, and we couldn’t have more different and complex identities. Also, the challenges we face are as different as each of our stories. So, in the spirit of Hispanic Heritage Month, please indulge me in letting me tell you my story.

There is a well-known character in Mexican history that invokes both love and condemnation from most Mexicans. Her name was Malintzin but history knows her as La Malinche . Her story is similar to that of U.S.A.’s Pocahontas ; the beautiful indigenous woman who abandons her tribe to help the white man. (The legends omit how she became the property of such White men, but that’s another story).

La Malinche was a Nahúatl woman who was given to Hernán Cortés as a slave. Due to her upperclass education, she spoke two languages, an ability that made her very useful to Hernán Cortés in communicating with the indigenous people as he went about conquering Mexico. On one hand, she was intelligent and, clearly, resilient. But on the other hand, she helped Cortés begin the Spanish colonization of the Nuevo Mundo. This duality is what gives her such a complex identity. And this duality is one that follows me.

When I was in high school, several of my classmates would sometimes call me Malinchista . As you can imagine, that was NOT a compliment. By definition, a Malinchista is “a person who denies her own cultural heritage by preferring foreign cultural expressions” (I’m not making it up; look it up).

In my early teens, I discovered American football. While switching channels on the television, I stumbled across a game being played in several feet of snow. I had never seen this! The game was being played in Minnesota. That year, the Dallas Cowboys won the Super Bowl, and I became a die-hard fan of Roger Staubach and “America’s Team.” This marked the initiation of my love for all things American. I learned about Formula 1, Sports Illustrated and Tiger Beat. Yes, Tiger Beat introduced me to the American darlings of my generation. My bedroom walls were covered with pictures of American teen idols I had never seen before in my life (in the 1970s, Mexican TV programming didn’t broadcast many American TV shows; I only remember Dallas and The Partridge Family , which of course, I loved).

I also loved English-language songs. I used to spend my money buying cancioneros , books similar in format and quality to comic books, for people who were learning to play the guitar. The cancioneros had the lyrics of the songs along with the music notes. I literally used these cancioneros to practice my English. I would translate each word of the songs, and then I would play the records over and over until I memorized the lyrics and could actually follow the singer pronouncing the words. Do you know how hard it is to sing at full speed: “Now they know how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall?”

By the time I was in college, I had already spent time in the city of Dallas (and yes, I made the pilgrimage to Irving, Texas and the Cowboys’ stadium) – and perfected my English. I started studying English when I entered first grade. By middle school, my parents were paying a private tutor. In Mexico, English was accepted as the lingua franca needed to succeed in the world, and my parents were going to make sure I learned it. (My dad had taught himself English, and he shared my enthusiasm for English language magazines, although not for the Dallas Cowboys.) Learning a second language allowed me to learn about, navigate and integrate into a different culture. And, unlike La Malinche , I did this of my own volition.

When I made the decision to come to the United States to study, my father told me, “If you ever decide this is not for you or things don’t work out, come back home.” But I was not turning back. In my mind, America was the best place in the whole world (my small world, at least). I had spent a semester in an exchange program at the University of Oklahoma, and I knew back then I belonged in the United States. One of the things that caught my attention early on was the fact that people could wear their pajamas to class (I know you’ve seen it), and nobody blinked an eye. One could wear her hair in blue spikes or wear slippers to the grocery store, and no one would say a thing. To me, that was amazing! People didn’t bother you, judge you or care what you wore. I felt America was the place where not only public services worked, but where you could be yourself and you could be free to be whomever you wanted to be. There was a sense of freedom that was refreshing.

However, for a long time I felt like I didn’t belong here, and I didn’t belong in Mexico, either. Navigating two worlds was not precisely difficult but sometimes unsettling . You spend your time “live switching” from English to Spanish to Spanglish and back again. You mix Cholula with Five Guys hamburgers. You watch American soccer but listen to the Mexican commentators (otherwise it’s like listening to golf announcers). And you truly think Mexican soccer fans are like the old Oakland Raiders fans, only worse. Women in Mexico are as rabid fans as many men, but, at least back in my day (I feel ancient now), you didn’t see many women go to the stadiums. As a woman, I never felt safe. I only went to a match if my male friends went with me. This is one of the most striking differences between the U.S. and Mexico: American soccer fans are so mild-mannered in comparison!

Another striking difference I noticed when I first came to the U.S. was that I was not getting cat calls out when I was out walking in the streets. In Mexico, everywhere I went (since I was a preteen, for goodness’ sake), I would be subjected to cat calls and whistles – and the harassment only got worse the older I got. My experience as a woman was of always being on high alert. But when I came to the U.S., I felt respected. I could exist without being harassed continually. Women here seemed to have a voice and the same opportunities as men to grow and pursue their dreams. I felt free to pursue a career and to not be expected to only dream of marrying and having children. Although, over the years, I’ve come to realize there still is much room for improvement.

Back in the 1500s La Malinche did what she could to survive (did I say historians think she died before she was 30?). History asked her to do a task she didn’t want, and she did her best. I am sure she considered her options and bought time, respect and the right to live in the best way she could. She used her skills to earn a place in history, and although her role continues to be debated, I cannot blame her. Did I turn my back on my country? Or did I look for a better life? My circle of Latina friends in the U.S. is full of intelligent, professional women who left their countries and built a better life – a different life – here in the United States. They all miss their families, and they all support their biological families in many ways. What they can do from here, however, is more than they could have done had they stayed in their countries of origin.

Being Latina in America is both an honor and a challenge. We struggle with the dualities of our worlds. We struggle with the adjectives that define us. We are a complex mix of races, traditions and experiences. We care for our people, and we work tirelessly to do what must be done to help each other. The complexity of our identities can help us create a better world for all of us, a world where our differences are not viewed as a threat but as an asset. A world where we all thrive. ¡Sí, se puede!

By: Claudia Ortega-Lukas Graphic Designer & Communications Professional

UPD Intern Macie King

‘What I didn't realize at the time was that I was about to join one of the most supportive, caring and energetic work environments I had ever experienced’

2024 Open educational grant awardees announced

The University Libraries are awarding grants hoping to save students money and make education more attainable

Optimism Series Domestic Mining Green Opportunities

Nevada Gold Mines Professor Pengbo Chu in the Department of Mining and Metallurgical Engineering sees domestic mining as a way to change the mining industry into a green industry

Art 100 student stickers

The artwork is displayed throughout campus and was created using equipment from the DeLaMare Science and Engineering Library (DLM) Makerspace and Art Department’s Fablab

Editor's Picks

AsPIre working group provides community, networking for Asian, Pacific Islander faculty and staff

University confers more than 3,000 degrees during spring commencement ceremonies

Father and son set to receive doctoral degrees May 17

Strong advisory board supports new Supply Chain and Transportation Management program in College of Business

Nevada Today

School of Public Health launches donor management and transplantation science certificate program

Program provides critical training for the organ and transplantation process; addresses health disparities in the field

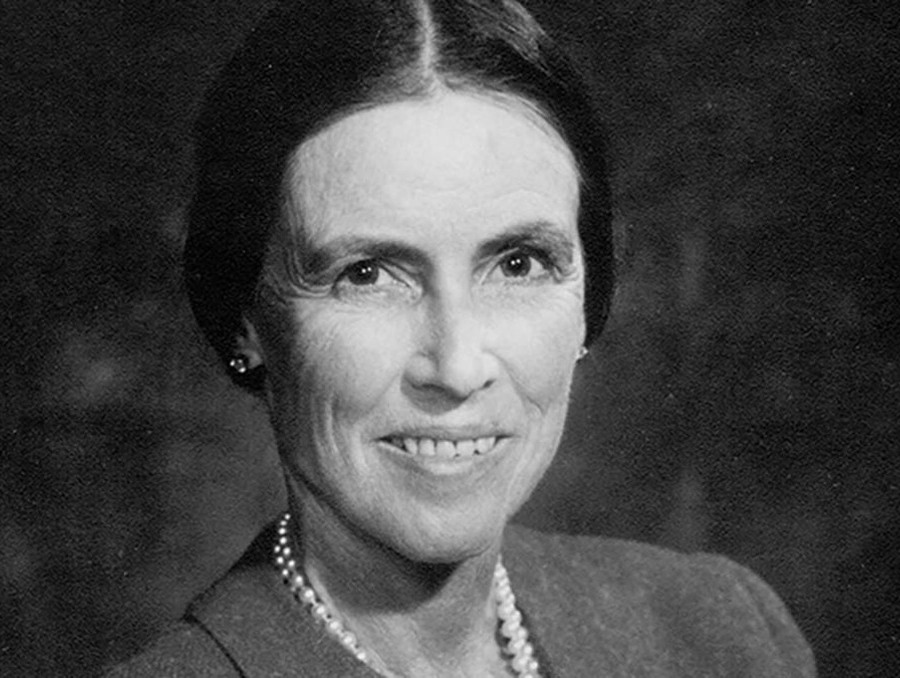

Molly Flagg Knudtsen: No place for a woman

Knudtsen was a cattle rancher, author and educator who served on the NSHE Board of Regents

Eric J. García Mural Unveiling Celebration

Honoring history, community and creativity at the College of Liberal Arts

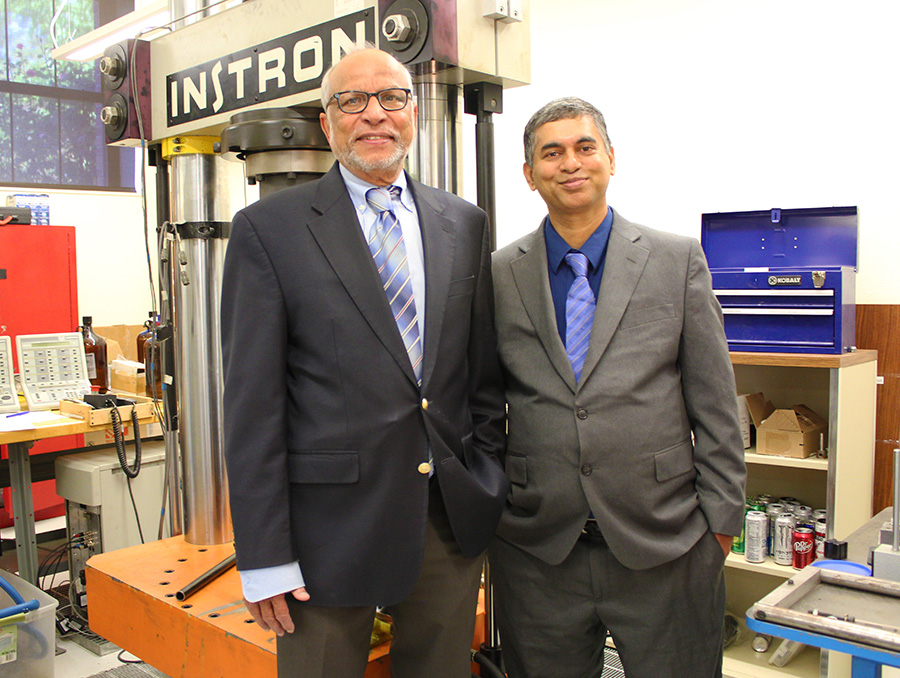

Engineering faculty researching solutions for the safe storage of spent nuclear fuels

Pradeep Menezes and Mano Misra lead $500,000 NRC-funded project

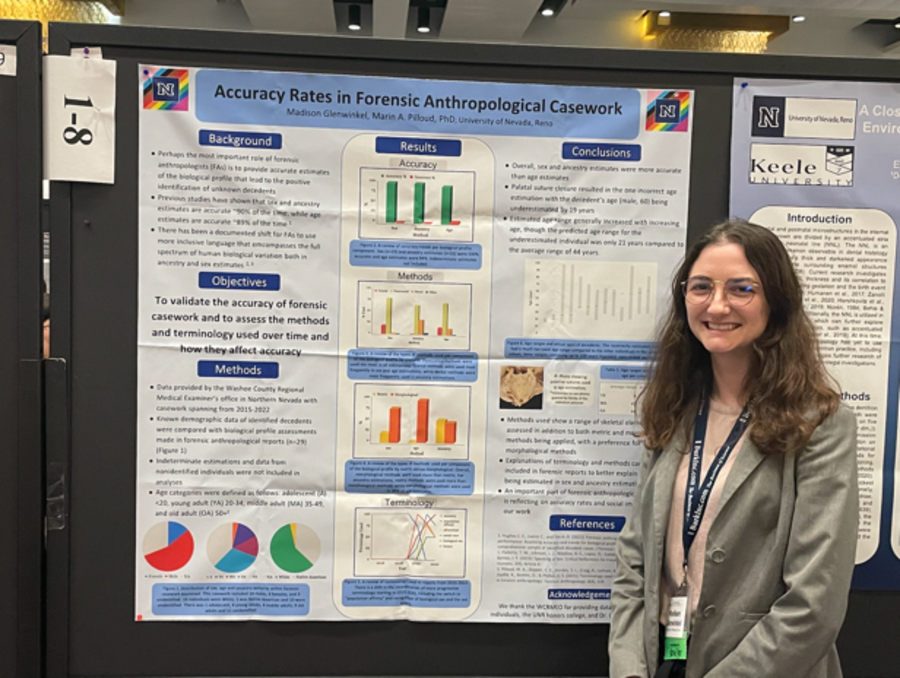

From lizards to humans, a journey in pursuit of science

Madison Glenwinkel, a student in the College of Liberal Arts, received the prestigious National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (NSF-GRFP) award

University of Nevada, Reno team develops new vegetation mapping tools

Improved management of rangeland, better recovery from wildfires, among likely benefits

Department of Speech Pathology and Audiology to host second annual Aphasia Camp in September 2024

The annual Nevada Aphasia Camp brings people from diverse backgrounds together for a weekend of camping filled with activities, good food and great conversation

United States Congressman Ro Khanna joins President Brian Sandoval for 'Discussions in Democracy'

Congressman Khanna joined the President in a conversation at the University of Nevada, Reno about voter education, exercising the vote and working across the aisle

For me, being Latino means living between two worlds

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Being a Latino in the U.S. can sometimes mean an evolving sense of identity. When I was a child, I identified simply as American — without a hyphen, asterisk or modifier.

I thought being American meant reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, learning about the War of 1812 in history class and watching blockbuster hits with friends.

But being at home was living in another world.

Tell us your story >>

Ma would cook enchiladas en salsa verde and, at least once a week, would shove the phone in my face, “Ten, habla con tu abuela que te quiere oír.” Translation: My grandma wanted to hear my voice.

I loved being in two worlds.

But that feeling of being a total American was short lived. When I was 7 or 8 years old, my parents told me I was born in Mexico. My American life was radically redefined. Later, I would come to be defined as a “dreamer,” still feeling no less American but with an asterisk.

In college, I did not feel like I was entirely from Mexico or the U.S. and toyed with identifying as Chicano. I was attracted by the feeling of nepantla — the Nahuatl word for “in the middle.”

But I still felt more Mexican, though the only home I knew was here in the U.S. Most of my classmates were born here and seemed to have a better grasp on the two identities.

Feeling more Mexican than completely American, I wasn’t feeling Chicano. I’m not just one thing — and, ultimately, being Latino isn’t one specific experience either.

That was five years ago. I’m working in Los Angeles on a permit through DACA , a policy that allows people brought here as children like me to work. And after having lived in Washington, D.C., — the mecca of American politics — surrounded by people from different backgrounds, I have a new sense of self.

Now, every time someone asks, “What are you?” or “Where are you from?” my answer is: I’m an Angeleno who was born in Mexico.

Hispanic, Latinx, Chicano. Immigrant, naturalized or U.S. born. Black, white, brown, blended.

Being Latino can mean so many different things, rooted in about two dozen different places of origin. And though Latinos may have a language in common, there isn’t a singular voice or narrative for the Latino experience.

Some speak English at work, hablan español en la casa or speak both languages con nuestros amigos — or no Spanish at all. Some fuse the two languages to say donde nos parkeamos, or “where do we park.”

There’s no denying that Latinos are changing politics , entertainment and the culture of the country.

The U.S. Latino population is at 57 million and counting. In California, Latinos have surpassed whites as the largest ethnic group.

In celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month, The Times wants to hear about your Latino identity. We plan to publish a collection of stories that highlight the variety of voices and experiences within the Latino community.

So tell us your story: What does being Latino in 2016 mean to you? You can fill out the survey below or share your story on Instagram using #MyLatinoIdentity or #MiIdentidadLatina.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

With deadline nearing, Newsom and lawmakers disagree over solutions to California budget crisis

Tired and confused, first migrants reach California border after Biden’s asylum order

Fifth quake to hit SoCal in 5 days: Small temblor strikes Newport Beach

Swift justice: Porsche driver is ticketed for 133 mph on the 101 Freeway

I’m a First-Generation American. Here’s What Helped Me Make It to College

- Share article

My father is an immigrant from Mexico who decided to sacrifice his home to give me a better life. He grew up with the notion that the United States had one of the best education systems in the world and he saw that education as my ticket to participate in the pursuit of happiness.

When he moved to America, he chose Flushing, Queens, in New York City—which this year became an epicenter of the COVID-19 crisis—because the public elementary school was highly regarded for its academics and safety. But navigating the public school system was extremely difficult, marked with constant reminders that the system was not designed for students like me. These difficulties and inequities have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis and will continue to impact students if they remain unaddressed.

My father always lived with the fear that if people found out I was the son of a Mexican immigrant, I would be ostracized in the classroom. From the first day of elementary school, he prayed that no one would bother me for being Mexican American, and that I would learn English quickly so I could defend against attacks on my identity. I have gone through all my academic career fighting the stereotypes that Mexicans are all “lazy” and “undocumented.”

I have experienced an interesting duality as a Mexican American, one that has played a formative role in my education and development. I have two languages, two countries, two identities. I learn in English but live in Spanish. I am Mexican at home but American at school.

I first became aware of this code-switching in middle school. The ways I interacted with my white, wealthy peers were far different from with my Latinx friends. I understood that English held more power than Spanish. Many people associate an accent or different regional variants of English to be unsophisticated, so I worked to be perceived as “articulate” and “well-spoken” at my local elementary and middle schools. In fact, it was my attention to coming across as “articulate” that helped me get into the high school that I attended.

I wanted to attend a high-achieving high school, but I did not perform well on the Specialized High School Admissions Test (SHSAT) and therefore failed to be admitted into one of New York City’s specialized high schools. But the principal of Millennium High School, a selective public high school in Manhattan, offered me a spot—and gave me a shot. Principal Colin McEvoy saw more than the student who failed to get into a SHSAT school. He saw a well-spoken kid who was determined to find a school that would have the resources to achieve his goal of graduating and going to college. My father had sacrificed everything so I could go to college, and I saw Millennium as the means to get there.

Not every student can have the same opportunity I did, but every school community and educator can take certain steps to support students who feel at odds within a system that was not designed for them. Here are three steps that will help students like me:

1. Play an active role in their students’ lives outside of academics. While this is important during “normal” times, it is even more important now during the global pandemic when students are worried about their family, cut off from friends, and unsure what the future holds. Each student should be assigned a teacher who also serves as adviser, an additional adult figure in their life to help guide and assist them—even if this is done virtually. At Millennium, each student in the beginning of the high school experience is assigned an adviser and meets in advisory class three days a week to complete college-preparatory activities and check in with their adviser about academics and their personal life.

2. Acknowledge how political developments may affect students. Schools should provide students who may be affected by a policy decision with the tools to protect their education. I have many friends who have been affected by the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy and had to go through the complex process of ensuring they could study in the country without their parents. This June, the Supreme Court rejected the Trump administration’s efforts to rescind DACA, but immigrants’ fight for protection under the law is far from over. It is important for teachers to understand how politics can impact the well-being of students—and how the fear of those impacts often take a toll on students’ academics.

3. Offer guidance on how to apply to college and options aside from college. My former high school requires every student to meet with the college guidance counselor at least twice, once each in their junior and senior years. As the first in my family to apply to college, these meetings were essential for me to figure out the application process, as well as for navigating financial aid and scholarships. It was only with this guidance that I applied for a Posse Foundation scholarship and earned a full scholarship to Middlebury College—opportunities that I would not have even known about otherwise.

As the COVID-19 vaccine gets rolled out more widely, there remain a lot of unknowns in higher education and in many families’ financial futures. Educators can help students explore alternate opportunities during this difficult time, including community college, internships, apprenticeships, gap years, or service-learning options.

Students of marginalized communities are both fighters and academics. Going through the American education system is difficult, and there are active ways that schools and educators can help their students navigate it. This is not a matter of doing the work for the students but acknowledging that there are several challenges present in students’ lives—challenges that may be exacerbated during a pandemic—and helping them navigate them.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Racial Identity and Racial Treatment of Mexican Americans

Vilma ortiz.

Department of Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles

Edward Telles

Department of Sociology, Princeton University

How racial barriers play in the experiences of Mexican Americans has been hotly debated. Some consider Mexican Americans similar to European Americans of a century ago that arrived in the United States with modest backgrounds but were eventually able to participate fully in society. In contrast, others argue that Mexican Americans have been racialized throughout U.S. history and this limits their participation in society. The evidence of persistent educational disadvantages across generations and frequent reports of discrimination and stereotyping support the racialization argument. In this paper, we explore the ways in which race plays a role in the lives of Mexican Americans by examining how education, racial characteristics, social interactions, relate to racial outcomes. We use the Mexican American Study Project, a unique data set based on a 1965 survey of Mexican Americans in Los Angeles and San Antonio combined with surveys of the same respondents and their adult children in 2000, thereby creating a longitudinal and intergenerational data set. First, we found that darker Mexican Americans, therefore appearing more stereotypically Mexican, report more experiences of discrimination. Second, darker men report much more discrimination than lighter men and than women overall. Third, more educated Mexican Americans experience more stereotyping and discrimination than their less-educated counterparts, which is partly due to their greater contact with Whites. Lastly, having greater contact with Whites leads to experiencing more stereotyping and discrimination. Our results are indicative of the ways in which Mexican Americans are racialized in the United States.

Mexican Americans have lower levels of education than non-Hispanic Whites and Blacks. Some scholars have argued that this is a result of Mexican immigrants having relatively low levels of education especially by standards in the United States, yet this gap is persistent and continues into the fourth generation ( Telles & Ortiz, 2008 ). To explain this, we have argued that the education disadvantage for Mexican Americans largely reflects their treatment as a stigmatized racial group rather than simply being a result of low immigrant human capital or of other causes suggested in the literature ( Telles & Ortiz, 2008 ). This paper investigates the role of race and racialization among Mexican Americans by more directly examining the relationships of education, skin color, and social interactions with racial identity and racial treatment (discrimination and stereotyping).

The role of race in the lives of Mexican Americans has been hotly debated. On the one hand, some argue that Mexican Americans have been racialized throughout their history in the United States ( Acuña, 1972 ; Almaguer, 1994 ; Barrera, 1979 ; Foley, 1997 ; Gomez, 2007 ; Montejano, 1987 ; Ngai, 2004 ; Vasquez, 2010 ). Their long and continuous history as labor migrants destined to jobs at the bottom of the economic hierarchy and their historic placement at the bottom of the racial hierarchy, preceded by the conquest of the original Mexican inhabitants in what is now the U.S. Southwest, have created a distinct racial category of “Mexican” in the popular imagination. While not as heavily excluded from economic and social integration as African Americans, Mexican origin persons have encountered severe racial barriers, which have structured opportunities for them. These scholars argue that Mexican Americans lag educationally and economically even after several generations in the United States, as a result of this treatment. They have been thus limited to mostly working class jobs and from successfully integrating into middle class society.

On the other hand, others consider Mexican Americans to be similar to European Americans with modest backgrounds ago that arrived in the United States more than a century ago ( Alba & Nee, 2003 ; Bean & Gillian, 2003 ; Perlmann, 2005 ). These assimilation theorists argue that while Mexican Americans may be slightly darker, slightly more stigmatized, and slightly more disadvantaged than these prior European groups, these factors will only slightly delay their integration into U.S. society. The key word here is “slightly.” These scholars recognize some of the disadvantages faced by the Mexican origin population but they do not consider these disadvantages sufficiently severe to affect long-term integration. However, the persistent educational disadvantage across generations and frequent reports of discrimination and stereotyping (like those we provided in Generations of Exclusion ) challenge this view.

In this paper, we examine the ways in which race plays a role in the lives of Mexican Americans. While we use the same data previously used in Generations of Exclusion , the analysis are entirely new. Here, we study the relationships between racial appearance (such as skin color), education, and social interactions (such as contact with Whites), on the one hand, with racial identity and racial treatment, on the other. This paper thus extends our findings from Generations of Exclusion .

Mexican Americans and Race in History and Sociology

The issue of race among Mexican Americans is contested in many ways. The racial heritage of Mexicans is mixed, with varying mixtures of European, Indigenous, and African ancestry. As a result, Mexicans are heterogeneous in their racial characteristics, ranging from having light to dark skin and eye color with many in the brown and mestizo middle. Outsiders tend not to see Mexicans as White or Black. Rather they are viewed through the stereotypic lens of being non-white or brown and largely indigenous-looking. Still much about the racial status of Mexicans is debated. Two issues in particular are—one is whether Mexican is a racial category and, two is whether Mexicans are white or non-white.

Mexican Americans themselves often provide ambiguous responses to race questions, perhaps reflecting their own uncertainty about their race as well as ambivalence about being non-white ( Gomez, 1992 ). Historically, Mexican Americans responded to questions about ethnic background with labels such Latin American or Spanish , as we showed with 1965 data in Generations of Exclusion ( Telles & Ortiz, 2008 ). This reinforced European ancestry in responses about group membership and a distancing from indigenous heritage. Up to the 1960s, Mexican American leaders, such as those in the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), emphasized the Spanish/European/White heritage of Mexican Americans, in attempts to secure rights as first class citizens and despite their treatment as non-white in American society ( Gross, 2003 ; Haney-Lopez, 2006 ).

However, a new generation of “Chicano” activists in the 1960s radicalized the Mexican American movement for civil rights, leading to an affirmation their indigenous or non-white roots while advocating equal opportunity for all, regardless of race ( Haney-Lopez, 2003 ; Muñoz, 1989 ). Since then, many Mexican Americans have embraced non-white notions of who they are. Today, many political elites position themselves as Hispanic and White ( Haney-Lopez, 2003 ) while many academics, legal scholars, and activists position themselves as Chicano or Latino and non-white ( Delgado, 2004 ). Among the general population, Mexican is often used as a response to the question “what is your race?” ( Gross, 2003 ), thus reflecting a popular understanding that Mexican is a racial category distinct from Whites, Blacks, or Asians.

Sociologists have also debated how to define Mexicans racially. Using the census parlance of race and ethnicity, many rely on the official definition of Mexican as an ethnic group and that Mexicans can be of any race ( Alba & Nee, 2003 ). This perspective of defining Mexican as an ethnic group aligns with notions that Mexicans are similar to previous European ethnic groups. For these scholars, ethnic groups are treated in more benign ways than racially distinct groups. Since Mexicans are not considered a racial group and thought to differ only slightly from Europeans, they should follow similar patterns of incorporation ( Alba & Nee, 2003 ), easily move into honorary White status ( Bonilla-Silva, 2003 ; Haney-Lopez, 2006 ), and subsequently incorporate fully into mainstream society ( Alba & Nee, 2003 ).

Intermarriage adds another layer of complexity to the question of whether Mexicans are a racial category. Intermarriage of Mexicans with European Americans (or Whites) has been the most common type of intermarriage, leading to the speculation that this will also serve to quickly move Mexicans into being White ( Alba, 2009 ; Alba & Islam, 2009 ). Yet children of Mexican-White marriages, while having lighter skin, may not actually abandon their Mexican identification ( Jiménez, 2010 ). Moreover, intermarriage increasingly involves other racial groups like Blacks and Asians, especially in multi-racial places, like Los Angeles. While the children of these intermarriages may lose some connection to being Mexican as a result of a having a Black or Asian parent, they do not move closer to being White, so they should continue to be racially ambiguous and non-white.

Mexican Americans in the Census

The United States government, in its efforts to count persons and their characteristics, has played a major role in how Mexicans are defined and classified, and these definitions have shifted significantly over the years. There are two key issues about the classification of Mexicans—one is whether individuals are asked directly about being Mexican (or Hispanic) origin, and two is how the census collects and analyzes racial information for Mexicans (and Hispanics).

Asking about Hispanic origin is relatively straightforward. Every census since 1970 has included a question on Hispanic origin. The most recent (2010) wording of this question is: Is this person of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin? The response categories have generally included Mexican (along with Mexican-Am. and Chicano), Puerto Rican, Cuban, and other. Since 1990, individuals were asked to fill in the country of origin when responding other Hispanic. 1 Prior to 1970, Mexicans (and Hispanics) were not asked directly about being Hispanic origin. Rather Information about place of birth, parents' place of birth, and mother tongue was collected in those censuses and these characteristics were used to count and describe the Mexican origin population.

The issue of how race is collected and analyzed for Mexicans (and Hispanics) is much more complicated ( Gibson & Jung, 2005 ). The general trend over time has been a shift from no classification to Mexican as a race, to Mexicans as White , to Mexicans as any race . Mexicans have resided in the U.S. since the mid-nineteenth century, yet up to the 1920 census, the Census Bureau made no mention of Mexicans or how to classify them. However, it appears that enumerators themselves made attempts to distinguish Mexicans from others since an unusually high number of “mulattoes” with Spanish surnames were counted in western states in 1880 ( Hochschild & Powell, 2008 ).

The first time that Mexicans are officially counted is the 1930 census. That year, Mexican was listed as a racial category, the one and only time that this occurred. Also, enumerators were employed to collect census information and individuals did not respond for themselves. The instructions provided to enumerators provide insights into how Mexicans were viewed at the time. They read as follows:

Mexicans .-Practically all Mexican laborers are of a racial mixture difficult to classify, though usually well recognized in the localities where they are found. In order to obtain separate figures for this racial group, it has been decided that all person born in Mexico, or having parents born in Mexico, who are not definitely white, Negro, Indian, Chinese, or Japanese, should be returned as Mexican (“Mex”) 2

These instructions indicate the understanding that Mexicans were mixed race but clearly not White or perceived as White. The use of “laborers” in the first line of this instruction suggest that class may have played a role into the use of Mexican in that laborers might have been classified as Mexican but higher status Mexicans might have been classified as White ( Hochschild & Powell 2008 ).

In response to protests from the Mexican government and LULAC about using Mexican as a racial category, the Census Bureau changed the official designation of Mexicans to White ( Gross, 2003 ; Hochschild & Powell 2008 ). Consequently, the 1940 and 1950 census provided the following instructions to enumerators: “Mexicans are to be regarded as white unless definitely of Indian or other nonwhite race.” 3 This clearly shows the shift from Mexican as a race to Mexicans as White . The population of Spanish mother tongue—defined from place of birth, parents' place of birth, and mother tongue—was counted and described in official publications ( Gibson & Jung, 2005 ). 4

Enumerators did not completed forms in the 1960 census, rather census forms were mailed to households and completed by individuals,. This made it possible for Mexicans (and Hispanics) to respond using any racial category. But the Census Bureau in both 1960 and 1970 continued to define Mexicans (and Hispanics) as racially White . Therefore Mexicans (and Hispanics), who responded other to the race question, had their answers changed (or recoded) to White . This served to ignore what individuals reported about themselves. Starting in 1980, the Census Bureau stopped defining Mexicans (and Hispanics) as White and defined them as being of any race . This meant that they stopped changing responses as other race provided by Mexicans (and Hispanics). Consequently from 1970 to 1980, there is a sharp increase in the overall number of individuals reporting that they are other race, largely attributed to large percentage of Hispanics who choose other race ( Gibson & Jung, 2005 ). More than 40 of Hispanics answered other to the race question in 1990 ( Rodriguez, 2000 ) and more than 45 percent of Mexicans reported that they are other race in 2000 ( Bonilla-Silva, 2003 ). 5

Of course, what is rarely acknowledged or reported is that when Mexicans report their race as other , they subsequently add Mexican in the explanation to this response—de facto, naming Mexican as their race. Census officials raise the concern that Mexicans, and Hispanics more generally, choose racial responses that do not fit officials' definitions of race. They find this so objectionable that they have sometimes argued that Latinos are “confused” or find it “difficult” to understand the race question on the census ( Rodriguez, 2000 ). 6 When we consider how the Census Bureau has changed the racial classification of Mexicans from none, to Mexican , to White , to any race , it could be argued that government bureaucrats are confused.

Mexican Americans as Non-Whites

Race is a social construct but one that has had real consequences in the United States. Although granted de facto White racial status with the United States conquest of much of Mexico in 1848 and having sometimes been deemed as White by the courts and censuses, Mexican Americans were rarely treated as White ( Gomez, 2007 ; Haney-Lopez, 2006 ). Historically and legally, Mexicans have been treated as second-class citizens. Within a few short decades after their conquest in the mid-nineteenth century, Mexican Americans, although officially granted United States citizenship with full rights, lost much of their property and status and were relegated to low-status positions as laborers. Since then, Mexican immigration has continued to be of predominately low status. Throughout the twentieth century, Mexicans with low levels of education and from poor backgrounds immigrated to the United States to fill the lowest paid jobs (agriculture, domestic work, construction) with peaks during the Mexican Revolution in 1910 to 1929, during the agricultural guest worker program for Mexicans (Bracero program) from 1942 to 1964, and post the Immigration Act of 1965 which liberalized immigration from the Americas. Most of Mexican immigration has been to the southwestern United States, although Mexicans have begun to settle in nearly all regions of the United States since about 1990. This continuous immigration throughout the twentieth century has meant that the Mexican origin population in the United States includes many persons born in the United States, varying in generational status from first (immigrant) to fourth and even fifth generation. These later generations have continued to face educational and economic disadvantages as we documented in Generations of Exclusion ( Telles & Ortiz, 2008 ).

Unfair and discriminatory treatment against Mexican Americans has extended beyond the economic realm. School segregation has been extensive, both historically and in contemporary periods. Throughout history, Mexican children were sent to separate and inferior schools ( Alvarez, 1986 ; San Miguel, 1987 ; Sanchez, 1993 ). School segregation was repeatedly challenged in the courts. While they were treated as non-white by Whites, challenges to segregation were won by employing the racial designation of White under the law, meaning that Mexicans as Whites could not be segregated from other Whites ( Martinez, 1997 ). Courts did allow the segregation of Mexicans due to language or migrant status. In the post civil rights era, Mexicans were used as the non-Blacks that integrated schools for Black children ( Gross, 2003 ; Mechaca, 1995 )). Eventually Mexicans moved from being considered White to brown, probably due to both legal and social changes although it is difficult to tell which of these occurred first ( Gross, 2003 ). As Mexicans came to be defined as non-whites, they were better able to make claims of unfair treatment and seek legal remedy. 7

Persuasive anti-immigrant sentiment and treatment has also worked against all Mexicans whether immigrant or born in the United States. Viewed as alien and low status, Mexican immigrants were (and continue to be) scapegoated and targeted for mistreatment. Even though immigrants were a minority of all Mexican Americans up to the 1980s, the perception of all Mexican Americans as low status immigrants has been pervasive ( Massey, 2009 ; Vasquez, 2010 ). The immigration legislation of the 1980s has made legal entry to the United States by Mexicans almost impossible, yet immigration has continued. This forced the overwhelming majority of Mexican immigrants in the late twentieth century to enter the United States without proper documentation. This has served to further fuse anti-Mexican and anti-undocumented immigrant sentiment ( Massey, 2009 ). This suggests that in the eyes of many White Americans, all Mexicans are “illegal” and all “illegals” are Mexican ( Chacón & Davis, 2006 ; Chavez, 2008 )

Research Purposes

If Mexican Americans see themselves as part of a racial category and are treated largely as non-white, what implications does this have for their experiences? Racial experiences are varied and involve many aspects of a person's life. On the one hand, some experiences concern how members of racial/ethnic groups view themselves. They may perceive themselves to be members of an ethnic group, like Italian-American, in a largely symbolic manner ( Waters, 1990 ). Or their identity may be a racial one, which implies a ranking along a racial hierarchy and which carries palpable social consequences. Secondly, they may encounter stereotypes which define how they should behave or who they should be; or they may encounter discrimination where they are treated differently due their group membership.

Racial appearance should factor into racial treatment, since we often define race as based on physical difference. 8 For example, Mexican Americans who are darker and physically differ to a greater extent from Whites are more likely to be perceived as members of the group. Moreover, to the extent that the group is considered non-white and stigmatized, darker Mexican Americans would be subject to greater stereotyping and discrimination than their light skin counterparts. Another indicator of racial appearance could be that of having a non-Hispanic parent. The offspring of mixed marriages, in addition to a skin color advantage, might carry other characteristics of Whiteness such as non-Spanish names and cultural or social resources that make them more acceptable to Whites.

Additionally we expect education to be related to racial outcomes among Mexican Americans. On the one hand, Mexican Americans with less education may have stronger perceptions of themselves as members of the group than those with more education. Conceivably, this relationship could be reversed if those with more education have greater awareness of being part of the group. What of the relationship between education and racial treatment? Less educated Mexican Americans might experience more stereotyping and discrimination because of their disadvantaged educational status. Or the more educated might experience worse treatment because of greater interactions in mainstream institutions and with members outside of their group. Additionally being more educated might increase awareness that Mexican Americans are treated in a racial manner and that might explain part of the education effects; in other words educated Mexican Americans might perceive that discrimination exists to a greater extent and that might partially explain their reports of being discriminated against.

Lastly, social interactions with Whites and with other Mexican Americans might affect perceptions and treatment. Having a greater number and closer relationships with Mexican Americans should reinforce the connection with the group but it is uncertain how these will affect treatment. Conversely interactions with Whites might result in more negative treatment but will that affect perceptions of being Mexican.

Lastly, what kinds of discrimination experiences do Mexican Americans describe? In what settings do they experience discrimination? Responses to open-ended questions in our survey provide glimpses into these experiences.

In sum, this paper examines (1) racial characteristics like skin color, (2) education, and (3) social interaction variables like contact with other Mexicans and Whites as predictors of (1) racial identity as in choosing a racial identity as Mexican and being perceived as Mexicans (2) racial treatment as in experiences of stereotyping and discrimination.

This study draws on a unique data set of 758 Mexican American adults between the ages of 30 to early 50s who were interviewed between 1998 and 2002. These respondents are adult children of the original respondents in the Mexican American Study Project (MASP).

MASP is a unique data set based on two waves of data collection 35 years apart. The original data was based on a random sample of households with adult Mexican Americans in Los Angeles County and San Antonio City who were interviewed in 1965-66 and those findings were published in The Mexican American People ( Grebler, Moore, & Guzman, 1970 ). We conducted a follow up survey with the original respondents from this earlier survey and their adult children in 1998-2002 and our findings were published in Generations of Exclusion ( Telles & Ortiz, 2008 ).

The re-interviews with surviving original respondents produced a longitudinal sample (1965 and 2000) of 687 original respondents who were age 18 to 50 in 1965. Two adult children were interviewed producing an inter-generational sample of 758 child respondents who were age 30 to early 50s when interviewed in 2000. Moreover, both the original 1965 respondents and their children are almost evenly divided by generations-since-immigration with about one-third of the child sample being second generation, one-third of the third generation and another third in the fourth generation or more.

In 2000, original respondents and adult children were interviewed extensively about ethnic identity, behavior, and attitudes; education and socio-economic status; political attitudes and behavior; family attitudes and behaviors. In this paper, we analyze the child sample based on their responses as well as some information from their original respondent parents.

In our analysis, we study two sets of outcomes—(1) racial identity as in choosing a racial identity as Mexican and being perceived as Mexicans (2) racial treatment as in experiences of stereotyping and discrimination. We examine three key sets of predictors—(1) racial characteristics like skin color, (2) education, and (3) social interaction variables like contact with other Mexicans and Whites.

Dependent Variables

We examine four outcomes in this paper and we show the distribution for these variables in Table 1 . Two of the outcomes measure racial identity . The first refers to how the respondents identify racially in response to “when forms or the census ask if you are White, Black, Asian, American Indian, or other, what do you answer?” To replicate the census question, we provided an “other” option for this question but purposefully did not include a Mexican American or Latino/Hispanic response category. Many respondents answered Mexican, Mexican American, or Mexican origin while others responded Hispanic or Latino. Responses to this question were grouped into Mexican, Mexican American, or Latino (coded as 1) compared to all other responses, such as White or Black (coded as 0). Two-thirds reported identifying as Mexican or Mexican American or Latino to the question about race (see Table 1 ). The second perception measure involves responses to “Do you think that when someone meets you for the first time that they think of you as Mexican? We coded their responses as perceived by others as Mexican (coded as 1) or not perceived or probably not perceived to be Mexican (coded as 0). Table 1 shows that 38 percent are definitely perceived as Mexican while 62 percent are not or probably not perceived as Mexican.

Our final two outcomes measure racial treatment . The first of these is whether respondents experience being stereotyped by others. We asked: “Sometimes people have ideas about what certain groups are like or what they are supposed to do. Do you ever find that other people expect you to be like or do things that they expect of Mexicans?” The responses are yes (coded as 1) or no (coded as 0). Table 1 shows that 58 percent perceive that they had experienced stereotyping. The second experience measure is whether respondents reported experiences of discrimination. We asked “Have you been treated unfairly because of your ethnic background?” The responses are yes (coded as 1) or no (coded as 0). Almost half (48 percent) reported experiences with discrimination. In contrast, Alba reports that approximately five percent of White ethnics experience discrimination ( Alba, 1990 ). 9

Predictor Variables

The first set of predictors captures physical markers of racial status, including one about actual skin color and another about parentage (means and ranges are presented on Table 2 ). Respondents' skin color was rated by interviewers rather than by respondents. We use the seven-point scale with seven being the darkest and one being the lightest. 10 The average on the skin color scale was 4.3, which is about halfway on the seven-point scale and indicating a medium brown skin color. A non-Hispanic parentage variable codes respondents that have only one parent as non-Hispanic as one and those with two Hispanic parents are coded as zero. Approximately 8 percent of respondents in the sample have a non-Hispanic parent. 11

Education is the second key predictor in our analysis (see Table 2 ). We compare three categories: those with less than high school (around 16 percent and the reference category), high school graduates and those with some college (71 percent), and college graduates or more (13 percent) 12 .

We include a measure indicating whether respondents perceive a lot of discrimination against Mexicans. We asked “how much discrimination do you think there is today again people of Mexican origin?” A significant percentage, 36 percent, reported that there is a great deal of discrimination against Mexicans. This is a measure of whether discrimination occurs generally and differs from the outcome measure of whether respondents report experiencing discrimination personally

The third set of predictors measure the extent of social interaction with racial/ethnic groups (see Table 2 ). The first involves the amount of contact with Whites, which was measured in our survey with four responses—not at all, a little, some, and a lot. Most respondents, 88 percent, reported having “a lot of contact” with Whites and thus we grouped this variable into two categories—not a lot of contact (coded as 0) and a lot of contact (coded as 1). The second social interaction variable gauges the frequency of friendships with Mexicans measured on a four-point scale ranging from none to few friendships (coded as 1), about half (coded as 2), most (coded as 3), and all friendships (coded as 4). The average is 2.3 or about halfway on the four-point scale.

Control Variables

We control for three sets of variables: individual characteristics, generational status and socio-economic background (means and ranges are presented on Table 3 ). The individual characteristics include gender, urban area, age and type of interview. Female (coded as 1) is compared to male (coded as 0), which divides at approximately 50 percent. The variable, San Antonio, refers to whether the original respondent parent was interviewed in San Antonio (coded as 1) or Los Angeles (coded as 0) with 36 percent of the sample from San Antonio and the remainder from Los Angeles. Age is a continuous variable ranging from 32 to 59 years old and averaging 42. Interviewed by phone (coded as 1) refers to respondents who were interviewed by phone, which is about 27 percent of the sample, rather than in person (coded as 0); we include this variable because some questions were not asked in the phone interviews and because they were somewhat more likely to have moved out of the area.

The second of the control variables is generational status (see Table 3 ). Generation 1.5 refers to respondents born in Mexico and raised in the United States, which is about 7 percent of the sample. Generation 2.0 refers to those born in the United States with two parents born in Mexico, which is 8 percent of respondents. Generation 2.5 are born in the United States with one parent born in Mexico and the other parent in the United States, which is 22 percent of the sample. Generation 3.0, the reference group, are born in the United States with both parents born in the United States and two to four grandparents born in Mexico, which is 40 percent of the sample. Generation 4.0 are born in the United States with both parents born in the United States and three of the four grandparents born in the United States, which comprises 23 percent of respondents.

The third set of control variables refers to socio-economic background (see Table 3 ). Much of this information is from the respondent's parent (the original respondent) and collected in either 1965 or 2000. Father's and mother's education range from 0 to 17 with an average of about 9 years of education. Income is family income in 1965. This was collected as a categorical variable, which we recoded to thousands. The average income is about $6,000 and the lowest category refers to income of less than $500 and the highest category refers to income of more than $20,000. Homeownership refers to whether the original respondent parent owned a home in 1965 (coded as 1); approximately 55 percent owned homes. The variable, number of siblings, ranges from 0 to 15 with an average of 5 siblings. Parent spoke Spanish to their children is coded as 1 for Spanish and 0 for not speaking Spanish (this was reported by the original respondent parent). About 85 percent of respondents had parents who spoke Spanish to them when they were children. The last variable is parents were married in 1965 while the respondent was growing up; 85 percent of parents were married at the time of the original survey.

Table 4 presents logistic regression analysis where racial identity as Mexican is the dependent variable. The numbers presented on this table, and the other tables with multivariate analyses, are odds ratios. An odds ratio equal to: one indicates no relationship, less than one indicates a negative relationship with numbers closer to zero indicating a stronger negative relationship, and greater than one indicates a positive relationship with larger numbers indicating a stronger positive relationship 13 .

Notes: Logistic regression; odds ratios presented; adjusted for 482 sibling clusters;

Racial Identity as Mexican

In the initial model on Table 4 , we observe that skin color is marginally related to racial identity as Mexican, indicating that darker respondents are somewhat more likely to identify racially as Mexican. 14 Having a non-Hispanic parent is unrelated to racially identifying as Mexican. More educated respondents were less likely than the low educated to identify racially as Mexican. Those who completed high school or have some college are significantly less likely to identify racially as Mexican—54 percent are less likely to do so. And the college educated is marginally less likely to identify racially as Mexican. In the second model, perceiving a lot of discrimination does not have a direct effect on identifying as Mexican or change the education effect. In the third model, contact with Whites and friendships with Mexicans are unrelated to identifying as Mexican.

The rest of Table 4 present control variables. Respondents from San Antonio and respondents who were interviewed by phone were significantly less likely to identify racially as Mexican. Gender and age are unrelated to identifying as Mexican. Generational status is unrelated to identifying as Mexican. The indicators of socio-economic status were also unrelated to identifying as Mexican (except for a marginal effect of income in the all three models).

Perceived as Mexican

Table 5 presents the findings for being perceived as Mexican. The first model indicates that having darker skin is significantly related to being perceived as Mexican. An odds ratio of 1.3 reveals that with every unit increase on the skin color scale, being perceived as Mexican increased by 30 percent. Those with a non-Hispanic parent are significantly less likely to be perceived as Mexican—about half as likely (odds ratio equals .44). More educated respondents were less likely than the less educated to be perceived as Mexican. Those who completed high school or have some college are 54 percent, and the college graduates are 31 percent, as likely to be perceived as Mexican. In the second model, perceiving a lot of discrimination does not have a direct effect on being perceived as Mexican or reduce the education effect.

Effect of Racial Appearance, Education, Social Interactions, and Controls on Perceived as Mexican among Mexican Americans

The third model indicates that those who have a lot of contact with Whites are half as likely to be perceived as Mexican (odds ratio equals .51). Persons with more Mexican friends are more likely to be perceived as Mexican—approximately one and a half times as likely (odds ratio equals 1.45). The effect of non-Hispanic parent, which was significant in the initial model (odds ratio equaled .44) and, is slightly reduced and is now marginally significant (odds ratio is .54). This is due to adding the extent of Mexican friends to the model. So persons with a non-Hispanic parent are less likely to be perceived as Mexican but some of this effect is through the friendships that Mexican Americans have with other Mexicans. 15

The rest of Table 5 present control variables. Gender and being from San Antonio are unrelated to being perceived as Mexican. Older respondents are marginally less likely to being perceived as Mexican. Respondents interviewed by phone were less likely to being perceived as Mexican in the first and second model but is not significant in the third model when social interactions are added to the model. The fourth generation is less likely to be perceived as Mexican than the third generation. Generation two differs from generation three in the first and second model but is not significant in the third model when social interactions are added to the model. The indicators of socio-economic status are unrelated to being perceived as Mexican.

Experience Stereotyping

The first model presented on Table 6 indicates that skin color and having a non-Hispanic parent are unrelated to experiences of stereotyping. More educated respondents are more likely to have been stereotyped by others. The relationship between education and experiences of stereotyping is especially strong—those with a high school or college education are more than twice as likely to being stereotyped than those less than high school (odds ratio equal 2.1 and 2.4 respectively).

Effect of Racial Appearance, Education, Social Interactions, and Controls on Experience Stereotyping among Mexican Americans

The second model on Table 6 shows that perceiving a lot of discrimination against Mexicans has a direct and positive effect on personal experiences with stereotyping. The third model shows that contact with Whites also increases experiences with stereotyping—those with more contact with Whites are two and a half times more likely to experience stereotyping. The extent of Mexican friends, on the other hand, is unrelated to experiences of stereotyping.

One reason that education is thought to lead to more experiences with stereotyping is that education may sensitize minorities to experiences of racialization. In other words, through learning about the history of racism and discrimination against the group, Mexican Americans may become more aware of its existence in their own lives. Adding general perceptions of a lot of discrimination (in the second model) does not change the relationship between education and perceptions of having been stereotyped. That more educated Mexican Americans perceive having more experiences of being stereotyped remains strong and significant in the second model.

Another reason that education is thought to relate to experiences with stereotyping is that participation in educational institutions provides more contact with Whites and thus greater awareness of White attitudes. Consistent with this, we observe that the education effects are somewhat reduced when contact with Whites is introduced in the third model. For instance, the college graduate effect is 2.4 when contact with Whites is excluded from the second model and is 1.99 when contact with Whites is added in the third model. So greater contact with Whites probably explains some of the experiences of being stereotyped.

The rest of Table 6 presents the control variables. Gender, being from San Antonio, and age are unrelated to experiences with stereotyping. Respondents interviewed by phone were less likely to experience stereotyping. Generational status was unrelated to experiences with stereotyping (except for that marginal effect of generation 1.5 in the first model). The indicators of socio-economic status are unrelated to experiences of stereotyping (except for that marginal effect of homeownership in the first model).

Experience Discrimination

As Table 7 shows, being darker also leads to reports of experiences with discrimination— an odds ratio of 1.2 indicates that with every unit increase on the skin color scale, reports of discrimination increased by 20 percent. Having a non-Hispanic parent is unrelated to reporting discrimination.

Effect of Racial Appearance, Education, Social Interactions, and Controls on Experience Discrimination among Mexican Americans

College educated respondents are more likely to report experiences of discrimination— twice as likely as those with less than a high school education (odds ratio equals 2.0). On the other hand, those with a high school education do not differ significantly from the least educated. In the second model, we observe that perceiving a lot of discrimination generally has a direct and positive effect on personal experiences with discrimination (odds ratio equals 2.3). In the third model, having more contact with Whites is shown to being more likely to be experience discrimination (odds ratio of 1.96). Having Mexican friends is unrelated to experiences of discrimination.

One of the issues we have tracked in the multivariate analysis is what happens to the education effects as we introduce perceptions of discrimination and contact with other groups. First, we observe that the education effect does not change between the first and second models when general perceptions about discrimination are entered into the model. Second, we observe that the college graduate effect is somewhat reduced between the second and third models when contact with Whites is introduced into the model. The college effect is 2.0 and statistically significant in the second model but when social interactions are introduced in the third model, the effect is reduced to 1.79 and is only marginally significant. Having more contact with Whites may partially explain why college graduates report more experiences of discrimination.

One of the control variables, gender, indicates that women are less likely to report discrimination (in contrast, gender was unrelated to any of the other racial outcomes). Given the strong relationship of gender and discrimination, we did some exploratory analysis separately by gender and we found that skin color has a much stronger effect for men than women. This is shown as the interaction effect between skin color and gender (Darker Color X Female) in the fourth model on Table 7 . This significant interaction effect indicates that darker men are much more likely to experience discrimination while darker and lighter women do not differ in their experiences of discrimination.

The rest of Table 7 presents the control variables. Being from San Antonio and age are unrelated to perceptions of experiences with discrimination. Respondents interviewed by phone were less likely to experience discrimination. Generation 1.5 reports more experiences with discrimination while the other generational groups do not differ from third generation.

The last group of control variables refers to socio-economic status. Parental education has an unusual pattern of relationships to discrimination experiences in that the greater the father's education, the more likely they are to report experiences of discrimination while the greater the mother's education, the less likely they are to report experiences of discrimination. Number of siblings is significantly related to experiences of discrimination in the third model when social interactions are entered in the model. The other controls—income, homeownership, speaking Spanish, married parents—are unrelated to experiences with discrimination.

Summary by Predictor Variables

Overall, skin color, education, and contact with Whites have the strongest relationships with the racial outcomes. Mexican Americans who are darker, more educated, and have more contact with Whites are more likely to be perceived as Mexicans, experience more stereotyping, and experience more discrimination. Additionally, skin color has a different relationship with discrimination experiences for men and women such that darker men report more discrimination.

Describing Incidents of Discrimination

The question in our survey on discrimination, which we used in this paper, was “Have you been treated unfairly because of your ethnic background?” Respondents who indicated that had been treated unfairly were also asked to describe these experiences. Respondents provided examples from various aspects of their lives including work, school, police, public life, and peers and their responses illustrate their real life experiences, beyond the yes/no responses to close-ended questions that we examined through quantitative analysis above.

The largest number of comments—over 90—was about employment incidents. The most prevalent among these were reports about being denied promotions. One respondent reported that “they were hiring for assistant foreman, and I had seniority and better qualifications and I was overpassed for the position.” Other respondents reported that they were not hired for jobs based on their racial appearance. Respondents also reported negative or hostile interactions with supervisors—one respondent reported filing a federal discrimination complaint against a supervisor. Still other respondents reported difficulties with customers or clients where their help was rejected. There were also a small number of reports about being denied an apartment.

Another large number of reports—45 reports—referred to school-based incidents. These included encountering teachers that had low expectations of them as in indicating surprise at the respondents' academic ability, or assuming that respondents did not speak English or had recently arrived from Mexico. Some respondents reported getting into trouble for speaking Spanish. Other reported derogatory names, such as “wetback,” by teachers or other school officials.

Respondents also reported problems with peers. Some of these incidents were physical as in the respondent who reported that other children tried to cut out his brown eyes in first grade. Other respondents reported being beat up by peers in junior high or high school. While these were events that took place in school setting, other similar events happened in neighborhoods and with peers while growing up. Incidents where respondents were called derogatory names or rejected by friends of friends or by parents of friends.

The other very large category of incidents involved being denied service in restaurants. Some of incidents involved direct comments like “we do not serve people like you.” Other incidents involved being ignored or receiving very slow service. Respondents also reported receiving poor service in stores by being ignored or followed.

There were about 20 reports involving police. These involved being stopped and harassed by the police. Some of these events led to arrests or searches. Some respondents reported being called derogatory names like “wetback.” There were other incidents involving government officials, like being scrutinized by the border patrol as they crossed the border

Although all of our respondents came of age in the post civil rights era, they reported fairly extensive experiences of discrimination and being stereotyped. This is evident in their responses to standard survey questions (with close-ended responses) as well as in their accounts of specific instances discrimination (presented in the previous section). These experiences were prevalent in institutional settings like the work place and school as well as in public places like restaurants and retail stores. These experiences, although almost certainly fewer in frequency and lesser in intensity than that documented historically ( Montejano, 1987 ), are indicative of pervasive racism and discrimination continuing in the post civil rights era.

Skin color is important in our findings in that darker Mexicans are more likely to be perceived as Mexican and experience discrimination. These are strong relationships controlling for the many other factors in our analysis. To outsiders, skin color is a key marker of group membership, consequently darker Mexican Americans are treated as stereotypically Mexican. Additionally, darker men report more experiences of discrimination than lighter men and women in general. This is consistent with prior research showing that minority men are especially likely to face obstacles in education, the labor market, and criminal justice system ( Harrison, Reynolds-Dobbs, & Thomas, 2008 ; Hersch, 2008 ; Reimers, 1983 ). Some respondents indicate this in their reports of incidents with police officers. On the other hand, having a non-Hispanic parent has a relatively weak effect. Although being the child of inter-marriage is considered one mechanism by which Mexican Americans can move away from being Mexican to being honorary White ( Alba, 2009 ), we do not find this to be the case. Children of intermarriage do not differ in most ways from those with two Mexican parents. 16

Education is important. Mexican Americans with more education report that they were less likely to racially identify as Mexican and be considered Mexican by outsiders, and more likely to be stereotyped and face discrimination. Among the strongest relationships we identified was that of education with being stereotyped. It appears that educated Mexican Americans go against the notions that outsiders have about the group. This may be partly due to the low levels of education among Mexican immigrants and that Mexican Americans even in later generations have relatively less education. Outsiders expect Mexican Americans to be less educated and treat them accordingly. But to apply that expectation to all Mexican Americans creates a stereotype.

Having more education means living and working in environments with more Whites and participating in institutions of higher education also involving more interactions with Whites. Greater contact with Whites partly explains the relationship between education and experiences of stereotyping and discrimination consistent with prior research by Feagin and his colleagues (e.g., Feagin & Sikes, 1994 ). Moreover, contact with Whites has a significant and independent effect on experiences of stereotyping and discrimination (which is not diminished by controlling for other factors). The specific examples of discrimination that respondents shared illustrate how this operates. In work places with employers and co-workers, Mexican Americans are likely to come in contact with Whites that treat them in discriminatory ways; for instance they report being passed over promotions or not getting hired. In education settings, teachers and other school staff make derogatory remarks or convey the message that Mexican Americans are less worthy. Mexican Americans also reported unfair treatment in public spaces, like restaurants and stores. It is in these interactions beyond the family and ethnic neighborhood, that Mexicans Americans face unequal treatment.

Limitations

The most significant limitation of this study is probably identifying the extent of discrimination and stereotyping. Collecting precise information on discrimination and stereotyping in survey research is challenging. Individuals may not always have information about how or whether they are systematically being treated differently from others or they overestimate whether they are being treated unfairly due to their group membership. While measuring racial treatment in a precise manner is unlikely, several factors make us confident that we are capturing a real phenomenon. One is that experimental studies show strong evidence that discrimination exists 17 ( Pager & Hana, 2008 ) supporting our respondents' reports of discrimination. Two is the legal history showing the ways in which Mexican Americans have been and continue to be treated in discriminatory ways ( Gross, 2003 ; Haney-Lopez, 2006 ). Three is the much greater reports of experiencing stereotyping and discrimination by Mexican Americans than other ethnic groups, such as Italians ( Alba, 1990 ). Lastly, the pervasive patterns of racial inequality as we describe here and in our prior work ( Telles and Ortiz 2008 ) support the view of substantial racialization of Mexican Americans over several generations.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge comments by Gary Koeske.

Appendix A.

1 1Enumeration forms and questionnaires found in the IPUM website: http://usa.ipums.org/usa/voliii/tEnumForm.shtml

2 Enumeration forms and questionnaires found in the IPUM website: http://usa.ipums.org/usa/voliii/tEnumForm.shtml

3 Enumeration forms and questionnaires found in the IPUM website: http://usa.ipums.org/usa/voliii/tEnumForm.shtml

4 Up to 1950, the Mexican origin population comprised the vast majority Hispanics in the United States. Puerto Ricans were only beginning to migrate to New York City and the Cuban immigration had not begun in earnest ( Bean and Tienda 1987 ). Mexican Americans continue to be the majority at about 66 percent.

5 By 1980, while Mexicans continue to be the largest Hispanic group, there are significant numbers of Puerto Ricans and Cubans residing in the United States. By 2000, there are significant of Dominicans and Central Americans ( Guzman 2001 ).

6 Also unacknowledged by census officials is that the race question itself is confusing since it includes seven Asian categories (Asian Indian Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, other Asian), four Pacific Islander categories (Native Hawaiian, Guamanian or Chamorro, Samoan, other Pacific Islander), and only four race categories (White, Black, American Indian, some other race). The census question on race includes many more country of origin or ethnic categories than racial categories.