Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write an argumentative essay | Examples & tips

How to Write an Argumentative Essay | Examples & Tips

Published on July 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

An argumentative essay expresses an extended argument for a particular thesis statement . The author takes a clearly defined stance on their subject and builds up an evidence-based case for it.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

When do you write an argumentative essay, approaches to argumentative essays, introducing your argument, the body: developing your argument, concluding your argument, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about argumentative essays.

You might be assigned an argumentative essay as a writing exercise in high school or in a composition class. The prompt will often ask you to argue for one of two positions, and may include terms like “argue” or “argument.” It will frequently take the form of a question.

The prompt may also be more open-ended in terms of the possible arguments you could make.

Argumentative writing at college level

At university, the vast majority of essays or papers you write will involve some form of argumentation. For example, both rhetorical analysis and literary analysis essays involve making arguments about texts.

In this context, you won’t necessarily be told to write an argumentative essay—but making an evidence-based argument is an essential goal of most academic writing, and this should be your default approach unless you’re told otherwise.

Examples of argumentative essay prompts

At a university level, all the prompts below imply an argumentative essay as the appropriate response.

Your research should lead you to develop a specific position on the topic. The essay then argues for that position and aims to convince the reader by presenting your evidence, evaluation and analysis.

- Don’t just list all the effects you can think of.

- Do develop a focused argument about the overall effect and why it matters, backed up by evidence from sources.

- Don’t just provide a selection of data on the measures’ effectiveness.

- Do build up your own argument about which kinds of measures have been most or least effective, and why.

- Don’t just analyze a random selection of doppelgänger characters.

- Do form an argument about specific texts, comparing and contrasting how they express their thematic concerns through doppelgänger characters.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

An argumentative essay should be objective in its approach; your arguments should rely on logic and evidence, not on exaggeration or appeals to emotion.

There are many possible approaches to argumentative essays, but there are two common models that can help you start outlining your arguments: The Toulmin model and the Rogerian model.

Toulmin arguments

The Toulmin model consists of four steps, which may be repeated as many times as necessary for the argument:

- Make a claim

- Provide the grounds (evidence) for the claim

- Explain the warrant (how the grounds support the claim)

- Discuss possible rebuttals to the claim, identifying the limits of the argument and showing that you have considered alternative perspectives

The Toulmin model is a common approach in academic essays. You don’t have to use these specific terms (grounds, warrants, rebuttals), but establishing a clear connection between your claims and the evidence supporting them is crucial in an argumentative essay.

Say you’re making an argument about the effectiveness of workplace anti-discrimination measures. You might:

- Claim that unconscious bias training does not have the desired results, and resources would be better spent on other approaches

- Cite data to support your claim

- Explain how the data indicates that the method is ineffective

- Anticipate objections to your claim based on other data, indicating whether these objections are valid, and if not, why not.

Rogerian arguments

The Rogerian model also consists of four steps you might repeat throughout your essay:

- Discuss what the opposing position gets right and why people might hold this position

- Highlight the problems with this position

- Present your own position , showing how it addresses these problems

- Suggest a possible compromise —what elements of your position would proponents of the opposing position benefit from adopting?

This model builds up a clear picture of both sides of an argument and seeks a compromise. It is particularly useful when people tend to disagree strongly on the issue discussed, allowing you to approach opposing arguments in good faith.

Say you want to argue that the internet has had a positive impact on education. You might:

- Acknowledge that students rely too much on websites like Wikipedia

- Argue that teachers view Wikipedia as more unreliable than it really is

- Suggest that Wikipedia’s system of citations can actually teach students about referencing

- Suggest critical engagement with Wikipedia as a possible assignment for teachers who are skeptical of its usefulness.

You don’t necessarily have to pick one of these models—you may even use elements of both in different parts of your essay—but it’s worth considering them if you struggle to structure your arguments.

Regardless of which approach you take, your essay should always be structured using an introduction , a body , and a conclusion .

Like other academic essays, an argumentative essay begins with an introduction . The introduction serves to capture the reader’s interest, provide background information, present your thesis statement , and (in longer essays) to summarize the structure of the body.

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how a typical introduction works.

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts is on the rise, and its role in learning is hotly debated. For many teachers who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its critical benefits for students and educators—as a uniquely comprehensive and accessible information source; a means of exposure to and engagement with different perspectives; and a highly flexible learning environment.

The body of an argumentative essay is where you develop your arguments in detail. Here you’ll present evidence, analysis, and reasoning to convince the reader that your thesis statement is true.

In the standard five-paragraph format for short essays, the body takes up three of your five paragraphs. In longer essays, it will be more paragraphs, and might be divided into sections with headings.

Each paragraph covers its own topic, introduced with a topic sentence . Each of these topics must contribute to your overall argument; don’t include irrelevant information.

This example paragraph takes a Rogerian approach: It first acknowledges the merits of the opposing position and then highlights problems with that position.

Hover over different parts of the example to see how a body paragraph is constructed.

A common frustration for teachers is students’ use of Wikipedia as a source in their writing. Its prevalence among students is not exaggerated; a survey found that the vast majority of the students surveyed used Wikipedia (Head & Eisenberg, 2010). An article in The Guardian stresses a common objection to its use: “a reliance on Wikipedia can discourage students from engaging with genuine academic writing” (Coomer, 2013). Teachers are clearly not mistaken in viewing Wikipedia usage as ubiquitous among their students; but the claim that it discourages engagement with academic sources requires further investigation. This point is treated as self-evident by many teachers, but Wikipedia itself explicitly encourages students to look into other sources. Its articles often provide references to academic publications and include warning notes where citations are missing; the site’s own guidelines for research make clear that it should be used as a starting point, emphasizing that users should always “read the references and check whether they really do support what the article says” (“Wikipedia:Researching with Wikipedia,” 2020). Indeed, for many students, Wikipedia is their first encounter with the concepts of citation and referencing. The use of Wikipedia therefore has a positive side that merits deeper consideration than it often receives.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

An argumentative essay ends with a conclusion that summarizes and reflects on the arguments made in the body.

No new arguments or evidence appear here, but in longer essays you may discuss the strengths and weaknesses of your argument and suggest topics for future research. In all conclusions, you should stress the relevance and importance of your argument.

Hover over the following example to see the typical elements of a conclusion.

The internet has had a major positive impact on the world of education; occasional pitfalls aside, its value is evident in numerous applications. The future of teaching lies in the possibilities the internet opens up for communication, research, and interactivity. As the popularity of distance learning shows, students value the flexibility and accessibility offered by digital education, and educators should fully embrace these advantages. The internet’s dangers, real and imaginary, have been documented exhaustively by skeptics, but the internet is here to stay; it is time to focus seriously on its potential for good.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

An argumentative essay tends to be a longer essay involving independent research, and aims to make an original argument about a topic. Its thesis statement makes a contentious claim that must be supported in an objective, evidence-based way.

An expository essay also aims to be objective, but it doesn’t have to make an original argument. Rather, it aims to explain something (e.g., a process or idea) in a clear, concise way. Expository essays are often shorter assignments and rely less on research.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

The majority of the essays written at university are some sort of argumentative essay . Unless otherwise specified, you can assume that the goal of any essay you’re asked to write is argumentative: To convince the reader of your position using evidence and reasoning.

In composition classes you might be given assignments that specifically test your ability to write an argumentative essay. Look out for prompts including instructions like “argue,” “assess,” or “discuss” to see if this is the goal.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write an Argumentative Essay | Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved August 26, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/argumentative-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, how to write an expository essay, what is your plagiarism score.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

II. Getting Started

2.3 Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content

Kathryn Crowther; Lauren Curtright; Nancy Gilbert; Barbara Hall; Tracienne Ravita; Kirk Swenson; and Terri Pantuso

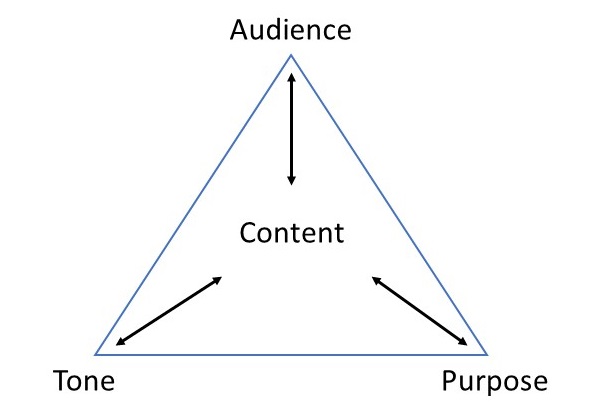

Now that you have determined the assignment parameters , it’s time to begin drafting. While doing so, it is important to remain focused on your topic and thesis in order to guide your reader through the essay. Imagine reading one long block of text with each idea blurring into the next. Even if you are reading a thrilling novel or an interesting news article, you will likely lose interest in what the author has to say very quickly. During the writing process, it is helpful to position yourself as a reader. Ask yourself whether you can focus easily on each point you make. Keep in mind that three main elements shape the content of each essay (see Figure 2.3.1). [1]

- Purpose: The reason the writer composes the essay.

- Audience: The individual or group whom the writer intends to address.

- Tone: The attitude the writer conveys about the essay’s subject.

The assignment’s purpose, audience, and tone dictate what each paragraph of the essay covers and how the paragraph supports the main point or thesis.

Identifying Common Academic Purposes

The purpose for a piece of writing identifies the reason you write it by, basically, answering the question “Why?” For example, why write a play? To entertain a packed theater. Why write instructions to the babysitter? To inform him or her of your schedule and rules. Why write a letter to your congressman? To persuade him to address your community’s needs.

In academic settings, the reasons for writing typically fulfill four main purposes:

- to classify

- to synthesize

- to evaluate

A classification shrinks a large amount of information into only the essentials , using your own words; although shorter than the original piece of writing, a classification should still communicate all the key points and key support of the original document without quoting the original text. Keep in mind that classification moves beyond simple summary to be informative .

An analysis , on the other hand, separates complex materials into their different parts and studies how the parts relate to one another. In the sciences, for example, the analysis of simple table salt would require a deconstruction of its parts—the elements sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl). Then, scientists would study how the two elements interact to create the compound NaCl, or sodium chloride: simple table salt.

In an academic analysis , instead of deconstructing compounds, the essay takes apart a primary source (an essay, a book, an article, etc.) point by point. It communicates the main points of the document by examining individual points and identifying how the points relate to one another.

The third type of writing— synthesis —combines two or more items to create an entirely new item. Take, for example, the electronic musical instrument aptly named the synthesizer. It looks like a simple keyboard but displays a dashboard of switches, buttons, and levers. With the flip of a few switches, a musician may combine the distinct sounds of a piano, a flute, or a guitar—or any other combination of instruments—to create a new sound. The purpose of an academic synthesis is to blend individual documents into a new document by considering the main points from one or more pieces of writing and linking the main points together to create a new point, one not replicated in either document.

Finally, an evaluation judges the value of something and determines its worth. Evaluations in everyday life are often not only dictated by set standards but also influenced by opinion and prior knowledge such as a supervisor’s evaluation of an employee in a particular job. Academic evaluations, likewise, communicate your opinion and its justifications about a particular document or a topic of discussion. They are influenced by your reading of the document as well as your prior knowledge and experience with the topic or issue. Evaluations typically require more critical thinking and a combination of classifying , analysis , and synthesis skills.

You will encounter these four purposes not only as you read for your classes but also as you read for work or pleasure and, because reading and writing work together, your writing skills will improve as you read. Remember that the purpose for writing will guide you through each part of your paper, helping you make decisions about content and style .

When reviewing directions for assignments, look for the verbs that ask you to classify, analyze, synthesize, or evaluate. Instructors often use these words to clearly indicate the assignment’s purpose. These words will cue you on how to complete the assignment because you will know its exact purpose.

Identifying the Audience

Imagine you must give a presentation to a group of executives in an office. Weeks before the big day, you spend time creating and rehearsing the presentation. You must make important, careful decisions not only about the content but also about your delivery. Will the presentation require technology to project figures and charts? Should the presentation define important words, or will the executives already know the terms? Should you wear your suit and dress shirt? The answers to these questions will help you develop an appropriate relationship with your audience, making them more receptive to your message.

Now imagine you must explain the same business concepts from your presentation to a group of high school students. Those important questions you previously answered may now require different answers. The figures and charts may be too sophisticated, and the terms will certainly require definitions. You may even reconsider your outfit and sport a more casual look. Because the audience has shifted, your presentation and delivery will shift as well to create a new relationship with the new audience.

In these two situations, the audience —the individuals who will watch and listen to the presentation—plays a role in the development of presentation. As you prepare the presentation, you visualize the audience to anticipate their expectations and reactions. What you imagine affects the information you choose to present and how you will present it. Then, during the presentation, you meet the audience in person and discover immediately how well you perform.

Although the audience for writing assignments—your readers—may not appear in person, they play an equally vital role. Even in everyday writing activities, you identify your readers’ characteristics, interests, and expectations before making decisions about what you write. In fact, thinking about the audience has become so common that you may not even detect the audience-driven decisions. For example, you update your status on a social networking site with the awareness of who will digitally follow the post. If you want to brag about a good grade, you may write the post to please family members. If you want to describe a funny moment, you may write with your friends’ senses of humor in mind. Even at work, you send emails with an awareness of an unintended receiver who could intercept the message.

In other words, being aware of “invisible” readers is a skill you most likely already possess and one you rely on every day. Consider the following paragraphs. Which one would the author send to her parents? Which one would she send to her best friend?

Last Saturday, I volunteered at a local hospital. The visit was fun and rewarding. I even learned how to do cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR. Unfortunately, I think I caught a cold from one of the patients. This week, I will rest in bed and drink plenty of clear fluids. I hope I am well by next Saturday to volunteer again.

OMG! You won’t believe this! My advisor forced me to do my community service hours at this hospital all weekend! We learned CPR but we did it on dummies, not even real peeps. And some kid sneezed on me and got me sick! I was so bored and sniffling all weekend; I hope I don’t have to go back next week. I def do NOT want to miss the basketball tournament!

Most likely, you matched each paragraph to its intended audience with little hesitation. Because each paragraph reveals the author’s relationship with the intended readers, you can identify the audience fairly quickly. When writing your own essays, you must engage with your audience to build an appropriate relationship given your subject.

Imagining your readers during each stage of the writing process will help you make decisions about your writing. Ultimately, the people you visualize will affect what and how you write.

While giving a speech, you may articulate an inspiring or critical message, but if you left your hair a mess and laced up mismatched shoes, your audience might not take you seriously. They may be too distracted by your appearance to listen to your words.

Similarly, grammar and sentence structure serve as the appearance of a piece of writing. Polishing your work using correct grammar will impress your readers and allow them to focus on what you have to say.

Because focusing on your intended audience will enhance your writing, your process, and your finished product, you must consider the specific traits of your audience members. Use your imagination to anticipate the readers’ demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations.

Demographics

These measure important data about a group of people such as their age range, their ethnicity, their religious beliefs, or their gender. Certain topics and assignments will require these kinds of considerations about your audience. For other topics and assignments, these measurements may not influence your writing in the end. Regardless, it is important to consider demographics when you begin to think about your purpose for writing.

Education considers the audience’s level of schooling. If audience members have earned a doctorate degree, for example, you may need to elevate your style and use more formal language. Or, if audience members are still in college, you could write in a more relaxed style. An audience member’s major or emphasis may also dictate your writing.

Prior Knowledge

This refers to what the audience already knows about your topic. If your readers have studied certain topics, they may already know some terms and concepts related to the topic. You may decide whether to define terms and explain concepts based on your audience’s prior knowledge. Although you cannot peer inside the brains of your readers to discover their knowledge, you can make reasonable assumptions . For instance, a nursing major would presumably know more about health-related topics than a business major would.

Expectations

These indicate what readers will look for while reading your assignment. Readers may expect consistencies in the assignment’s appearance such as correct grammar and traditional formatting like double-spaced lines and legible font. Readers may also have content-based expectations given the assignment’s purpose and organization. In an essay titled “The Economics of Enlightenment: The Effects of Rising Tuition,” for example, audience members may expect to read about the economic repercussions of college tuition costs.

Selecting an Appropriate Tone

Tone identifies a speaker’s attitude toward a subject or another person. You may pick up a person’s tone of voice fairly easily in conversation. A friend who tells you about her weekend may speak excitedly about a fun skiing trip. An instructor who means business may speak in a low, slow voice to emphasize her serious mood. Or, a coworker who needs to let off some steam after a long meeting may crack a sarcastic joke.

Just as speakers transmit emotion through voice, writers can transmit a range of attitudes and emotions through prose –from excited and humorous to somber and critical. These emotions create connections among the audience, the author, and the subject, ultimately building a relationship between the audience and the text. To stimulate these connections, writers convey their attitudes and feelings with useful devices such as sentence structure, word choice, punctuation, and formal or informal language. Keep in mind that the writer’s attitude should always appropriately match the audience and the purpose.

Read the following paragraph and consider the writer’s tone. How would you describe the writer’s attitude toward wildlife conservation?

“Many species of plants and animals are disappearing right before our eyes. If we don’t act fast, it might be too late to save them. Human activities, including pollution, deforestation, hunting, and overpopulation, are devastating the natural environment. Without our help, many species will not survive long enough for our children to see them in the wild. Take the tiger, for example. Today, tigers occupy just seven percent of their historical range, and many local populations are already extinct. Hunted for their beautiful pelts and other body parts, the tiger population has plummeted from one hundred thousand in 1920 to just a few thousand. Contact your local wildlife conservation society today to find out how you can stop this terrible destruction.”

Choosing Appropriate, Interesting Content

Content refers to all the written substance in a document. After selecting an audience and a purpose, you must choose what information will make it to the page. Content may consist of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes , testimonies , and observations, but no matter the type, the information must be appropriate and interesting for the audience and purpose. An essay written for third graders that summarizes the legislative process, for example, would have to contain succinct and simple content.

Content is also shaped by tone . When the tone matches the content, the audience will be more engaged, and you will build a stronger relationship with your readers. When applied to that audience of third graders, you would choose simple content that the audience would easily understand, and you would express that content through an enthusiastic tone.

The same considerations apply to all audiences and purposes.

This section contains material from:

Crowther, Kathryn, Lauren Curtright, Nancy Gilbert, Barbara Hall, Tracienne Ravita, and Kirk Swenson. Successful College Composition . 2nd edition. Book 8. Georgia: English Open Textbooks, 2016. http://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8 . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

- “The Rhetorical Triangle” was derived by Brandi Gomez from an image in: Kathryn Crowther et al., Successful College Composition, 2nd ed. Book 8. (Georgia: English Open Textbooks, 2016), https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8/ . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . ↵

The bounds, limits, or confines of something.

A statement, usually one sentence, that summarizes an argument that will later be explained, expanded upon, and developed in a longer essay or research paper. In undergraduate writing, a thesis statement is often found in the introductory paragraph of an essay. The plural of thesis is theses .

The essence of something; those things that compose the foundational elements of a thing; the basics.

A brief and concise statement or series of statements that outlines the main point(s) of a longer work. To summarize is to create a brief and concise statement or series of statements that outlines the main point(s) of a longer work.

To give or relay information; explanatory.

The fusion, combination, or integration of two or more ideas or objects that create new ideas or objects.

To copy, duplicate, or reproduce.

To organize or arrange.

The process of critically examining, investigating, or interpreting a specific topic or subject matter in order to come to an original conclusion.

The subject matter; the information contained within a text; the configuration of ideas that make up an argument.

The choices that a writer makes in order to make their argument or express their ideas; putting different elements of writing together in order to present an argument. Style refers to the way an argument is framed, written, and presented.

To interrupt, stop, or prevent someone or something from coming to pass or getting from one place to the other.

Clear or lucid speech; the expression of an idea in a coherent or logical manner; the communication of a concept in a way that is easily understandable to an audience.

The person or group of people who view and analyze the work of a writer, researcher, or other content creator.

Qualities, features, or attributes relating to something, particularly personal characteristics.

Taking something for granted; an expected result; to be predisposed towards a certain outcome.

Consequences; the impact, usually negative, of an action or event.

Writing that is produced in sentence form; the opposite of poetry, verse, or song. Some of the most common types of prose include research papers, essays, articles, novels, and short stories.

A short account or telling of an incident or story, either personal or historical; anecdotal evidence is frequently found in the form of a personal experience rather than objective data or widespread occurrence.

Verbal or written proof from an individual; the statement made by a witness that is understood to be truth. Testimony can be a formal process, such as a testimony made in official court proceedings, or an informal process, such as claiming that a company’s product or service works.

To express an idea in as few words as possible; concise, brief, or to the point.

The feeling or attitude of the writer which can be inferred by the reader, usually conveyed through vocabulary, word choice, and phrasing; associated with emotion.

2.3 Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content Copyright © 2022 by Kathryn Crowther; Lauren Curtright; Nancy Gilbert; Barbara Hall; Tracienne Ravita; Kirk Swenson; and Terri Pantuso is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

We define an argumentative essay as a type of essay that presents arguments about both sides of an issue. The purpose is to convince the reader to accept a particular viewpoint or action. In an argumentative essay, the writer takes a stance on a controversial or debatable topic and supports their position with evidence, reasoning, and examples. The essay should also address counterarguments, demonstrating a thorough understanding of the topic.

Table of Contents

What is an argumentative essay .

- Argumentative essay structure

- Argumentative essay outline

- Types of argument claims

How to write an argumentative essay?

- Argumentative essay writing tips

- Good argumentative essay example

How to write a good thesis

- How to Write an Argumentative Essay with Paperpal?

Frequently Asked Questions

An argumentative essay is a type of writing that presents a coherent and logical analysis of a specific topic. 1 The goal is to convince the reader to accept the writer’s point of view or opinion on a particular issue. Here are the key elements of an argumentative essay:

- Thesis Statement : The central claim or argument that the essay aims to prove.

- Introduction : Provides background information and introduces the thesis statement.

- Body Paragraphs : Each paragraph addresses a specific aspect of the argument, presents evidence, and may include counter arguments. Articulate your thesis statement better with Paperpal. Start writing now!

- Evidence : Supports the main argument with relevant facts, examples, statistics, or expert opinions.

- Counterarguments : Anticipates and addresses opposing viewpoints to strengthen the overall argument.

- Conclusion : Summarizes the main points, reinforces the thesis, and may suggest implications or actions.

Argumentative essay structure

Aristotelian, Rogerian, and Toulmin are three distinct approaches to argumentative essay structures, each with its principles and methods. 2 The choice depends on the purpose and nature of the topic. Here’s an overview of each type of argumentative essay format.

| ) | ||

| : Introduce the topic. Provide background information. Present the thesis statement or main argument. | : Introduce the issue. Provide background information. Establish a neutral and respectful tone. | : Introduce the issue. Provide background information. Present the claim or thesis. |

| : Provide context or background information. Set the stage for the argument. | : Describe opposing viewpoints without judgment. Show an understanding of the different perspectives. | : Clearly state the main argument or claim. |

| : Present the main argument with supporting evidence. Use logical reasoning. Address counterarguments and refute them. | : Present your thesis or main argument. Identify areas of common ground between opposing views. | : Provide evidence to support the claim. Include facts, examples, and statistics. |

| : Acknowledge opposing views. Provide counterarguments and evidence against them. | : Present your arguments while acknowledging opposing views. Emphasize shared values or goals. Seek compromise and understanding. | : Explain the reasoning that connects the evidence to the claim. Make the implicit assumptions explicit. |

| : Summarize the main points. Reassert the thesis. End with a strong concluding statement. | : Summarize areas of agreement. Reiterate the importance of finding common ground. End on a positive note. | : Provide additional support for the warrant. Offer further justification for the reasoning. |

| Address potential counterarguments. Provide evidence and reasoning to refute counterclaims. | ||

| Respond to counterarguments and reinforce the original claim. | ||

| Summarize the main points. Reinforce the strength of the argument. |

Have a looming deadline for your argumentative essay? Write 2x faster with Paperpal – Start now!

Argumentative essay outline

An argumentative essay presents a specific claim or argument and supports it with evidence and reasoning. Here’s an outline for an argumentative essay, along with examples for each section: 3

1. Introduction :

- Hook : Start with a compelling statement, question, or anecdote to grab the reader’s attention.

Example: “Did you know that plastic pollution is threatening marine life at an alarming rate?”

- Background information : Provide brief context about the issue.

Example: “Plastic pollution has become a global environmental concern, with millions of tons of plastic waste entering our oceans yearly.”

- Thesis statement : Clearly state your main argument or position.

Example: “We must take immediate action to reduce plastic usage and implement more sustainable alternatives to protect our marine ecosystem.”

2. Body Paragraphs :

- Topic sentence : Introduce the main idea of each paragraph.

Example: “The first step towards addressing the plastic pollution crisis is reducing single-use plastic consumption.”

- Evidence/Support : Provide evidence, facts, statistics, or examples that support your argument.

Example: “Research shows that plastic straws alone contribute to millions of tons of plastic waste annually, and many marine animals suffer from ingestion or entanglement.”

- Counterargument/Refutation : Acknowledge and refute opposing viewpoints.

Example: “Some argue that banning plastic straws is inconvenient for consumers, but the long-term environmental benefits far outweigh the temporary inconvenience.”

- Transition : Connect each paragraph to the next.

Example: “Having addressed the issue of single-use plastics, the focus must now shift to promoting sustainable alternatives.”

3. Counterargument Paragraph :

- Acknowledgement of opposing views : Recognize alternative perspectives on the issue.

Example: “While some may argue that individual actions cannot significantly impact global plastic pollution, the cumulative effect of collective efforts must be considered.”

- Counterargument and rebuttal : Present and refute the main counterargument.

Example: “However, individual actions, when multiplied across millions of people, can substantially reduce plastic waste. Small changes in behavior, such as using reusable bags and containers, can have a significant positive impact.”

4. Conclusion :

- Restatement of thesis : Summarize your main argument.

Example: “In conclusion, adopting sustainable practices and reducing single-use plastic is crucial for preserving our oceans and marine life.”

- Call to action : Encourage the reader to take specific steps or consider the argument’s implications.

Example: “It is our responsibility to make environmentally conscious choices and advocate for policies that prioritize the health of our planet. By collectively embracing sustainable alternatives, we can contribute to a cleaner and healthier future.”

Types of argument claims

A claim is a statement or proposition a writer puts forward with evidence to persuade the reader. 4 Here are some common types of argument claims, along with examples:

- Fact Claims : These claims assert that something is true or false and can often be verified through evidence. Example: “Water boils at 100°C at sea level.”

- Value Claims : Value claims express judgments about the worth or morality of something, often based on personal beliefs or societal values. Example: “Organic farming is more ethical than conventional farming.”

- Policy Claims : Policy claims propose a course of action or argue for a specific policy, law, or regulation change. Example: “Schools should adopt a year-round education system to improve student learning outcomes.”

- Cause and Effect Claims : These claims argue that one event or condition leads to another, establishing a cause-and-effect relationship. Example: “Excessive use of social media is a leading cause of increased feelings of loneliness among young adults.”

- Definition Claims : Definition claims assert the meaning or classification of a concept or term. Example: “Artificial intelligence can be defined as machines exhibiting human-like cognitive functions.”

- Comparative Claims : Comparative claims assert that one thing is better or worse than another in certain respects. Example: “Online education is more cost-effective than traditional classroom learning.”

- Evaluation Claims : Evaluation claims assess the quality, significance, or effectiveness of something based on specific criteria. Example: “The new healthcare policy is more effective in providing affordable healthcare to all citizens.”

Understanding these argument claims can help writers construct more persuasive and well-supported arguments tailored to the specific nature of the claim.

If you’re wondering how to start an argumentative essay, here’s a step-by-step guide to help you with the argumentative essay format and writing process.

- Choose a Topic: Select a topic that you are passionate about or interested in. Ensure that the topic is debatable and has two or more sides.

- Define Your Position: Clearly state your stance on the issue. Consider opposing viewpoints and be ready to counter them.

- Conduct Research: Gather relevant information from credible sources, such as books, articles, and academic journals. Take notes on key points and supporting evidence.

- Create a Thesis Statement: Develop a concise and clear thesis statement that outlines your main argument. Convey your position on the issue and provide a roadmap for the essay.

- Outline Your Argumentative Essay: Organize your ideas logically by creating an outline. Include an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Each body paragraph should focus on a single point that supports your thesis.

- Write the Introduction: Start with a hook to grab the reader’s attention (a quote, a question, a surprising fact). Provide background information on the topic. Present your thesis statement at the end of the introduction.

- Develop Body Paragraphs: Begin each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that relates to the thesis. Support your points with evidence and examples. Address counterarguments and refute them to strengthen your position. Ensure smooth transitions between paragraphs.

- Address Counterarguments: Acknowledge and respond to opposing viewpoints. Anticipate objections and provide evidence to counter them.

- Write the Conclusion: Summarize the main points of your argumentative essay. Reinforce the significance of your argument. End with a call to action, a prediction, or a thought-provoking statement.

- Revise, Edit, and Share: Review your essay for clarity, coherence, and consistency. Check for grammatical and spelling errors. Share your essay with peers, friends, or instructors for constructive feedback.

- Finalize Your Argumentative Essay: Make final edits based on feedback received. Ensure that your essay follows the required formatting and citation style.

Struggling to start your argumentative essay? Paperpal can help – try now!

Argumentative essay writing tips

Here are eight strategies to craft a compelling argumentative essay:

- Choose a Clear and Controversial Topic : Select a topic that sparks debate and has opposing viewpoints. A clear and controversial issue provides a solid foundation for a strong argument.

- Conduct Thorough Research : Gather relevant information from reputable sources to support your argument. Use a variety of sources, such as academic journals, books, reputable websites, and expert opinions, to strengthen your position.

- Create a Strong Thesis Statement : Clearly articulate your main argument in a concise thesis statement. Your thesis should convey your stance on the issue and provide a roadmap for the reader to follow your argument.

- Develop a Logical Structure : Organize your essay with a clear introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. Each paragraph should focus on a specific point of evidence that contributes to your overall argument. Ensure a logical flow from one point to the next.

- Provide Strong Evidence : Support your claims with solid evidence. Use facts, statistics, examples, and expert opinions to support your arguments. Be sure to cite your sources appropriately to maintain credibility.

- Address Counterarguments : Acknowledge opposing viewpoints and counterarguments. Addressing and refuting alternative perspectives strengthens your essay and demonstrates a thorough understanding of the issue. Be mindful of maintaining a respectful tone even when discussing opposing views.

- Use Persuasive Language : Employ persuasive language to make your points effectively. Avoid emotional appeals without supporting evidence and strive for a respectful and professional tone.

- Craft a Compelling Conclusion : Summarize your main points, restate your thesis, and leave a lasting impression in your conclusion. Encourage readers to consider the implications of your argument and potentially take action.

Good argumentative essay example

Let’s consider a sample of argumentative essay on how social media enhances connectivity:

In the digital age, social media has emerged as a powerful tool that transcends geographical boundaries, connecting individuals from diverse backgrounds and providing a platform for an array of voices to be heard. While critics argue that social media fosters division and amplifies negativity, it is essential to recognize the positive aspects of this digital revolution and how it enhances connectivity by providing a platform for diverse voices to flourish. One of the primary benefits of social media is its ability to facilitate instant communication and connection across the globe. Platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram break down geographical barriers, enabling people to establish and maintain relationships regardless of physical location and fostering a sense of global community. Furthermore, social media has transformed how people stay connected with friends and family. Whether separated by miles or time zones, social media ensures that relationships remain dynamic and relevant, contributing to a more interconnected world. Moreover, social media has played a pivotal role in giving voice to social justice movements and marginalized communities. Movements such as #BlackLivesMatter, #MeToo, and #ClimateStrike have gained momentum through social media, allowing individuals to share their stories and advocate for change on a global scale. This digital activism can shape public opinion and hold institutions accountable. Social media platforms provide a dynamic space for open dialogue and discourse. Users can engage in discussions, share information, and challenge each other’s perspectives, fostering a culture of critical thinking. This open exchange of ideas contributes to a more informed and enlightened society where individuals can broaden their horizons and develop a nuanced understanding of complex issues. While criticisms of social media abound, it is crucial to recognize its positive impact on connectivity and the amplification of diverse voices. Social media transcends physical and cultural barriers, connecting people across the globe and providing a platform for marginalized voices to be heard. By fostering open dialogue and facilitating the exchange of ideas, social media contributes to a more interconnected and empowered society. Embracing the positive aspects of social media allows us to harness its potential for positive change and collective growth.

- Clearly Define Your Thesis Statement: Your thesis statement is the core of your argumentative essay. Clearly articulate your main argument or position on the issue. Avoid vague or general statements.

- Provide Strong Supporting Evidence: Back up your thesis with solid evidence from reliable sources and examples. This can include facts, statistics, expert opinions, anecdotes, or real-life examples. Make sure your evidence is relevant to your argument, as it impacts the overall persuasiveness of your thesis.

- Anticipate Counterarguments and Address Them: Acknowledge and address opposing viewpoints to strengthen credibility. This also shows that you engage critically with the topic rather than presenting a one-sided argument.

How to Write an Argumentative Essay with Paperpal?

Writing a winning argumentative essay not only showcases your ability to critically analyze a topic but also demonstrates your skill in persuasively presenting your stance backed by evidence. Achieving this level of writing excellence can be time-consuming. This is where Paperpal, your AI academic writing assistant, steps in to revolutionize the way you approach argumentative essays. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to use Paperpal to write your essay:

- Sign Up or Log In: Begin by creating an account or logging into paperpal.com .

- Navigate to Paperpal Copilot: Once logged in, proceed to the Templates section from the side navigation bar.

- Generate an essay outline: Under Templates, click on the ‘Outline’ tab and choose ‘Essay’ from the options and provide your topic to generate an outline.

- Develop your essay: Use this structured outline as a guide to flesh out your essay. If you encounter any roadblocks, click on Brainstorm and get subject-specific assistance, ensuring you stay on track.

- Refine your writing: To elevate the academic tone of your essay, select a paragraph and use the ‘Make Academic’ feature under the ‘Rewrite’ tab, ensuring your argumentative essay resonates with an academic audience.

- Final Touches: Make your argumentative essay submission ready with Paperpal’s language, grammar, consistency and plagiarism checks, and improve your chances of acceptance.

Paperpal not only simplifies the essay writing process but also ensures your argumentative essay is persuasive, well-structured, and academically rigorous. Sign up today and transform how you write argumentative essays.

The length of an argumentative essay can vary, but it typically falls within the range of 1,000 to 2,500 words. However, the specific requirements may depend on the guidelines provided.

You might write an argumentative essay when: 1. You want to convince others of the validity of your position. 2. There is a controversial or debatable issue that requires discussion. 3. You need to present evidence and logical reasoning to support your claims. 4. You want to explore and critically analyze different perspectives on a topic.

Argumentative Essay: Purpose : An argumentative essay aims to persuade the reader to accept or agree with a specific point of view or argument. Structure : It follows a clear structure with an introduction, thesis statement, body paragraphs presenting arguments and evidence, counterarguments and refutations, and a conclusion. Tone : The tone is formal and relies on logical reasoning, evidence, and critical analysis. Narrative/Descriptive Essay: Purpose : These aim to tell a story or describe an experience, while a descriptive essay focuses on creating a vivid picture of a person, place, or thing. Structure : They may have a more flexible structure. They often include an engaging introduction, a well-developed body that builds the story or description, and a conclusion. Tone : The tone is more personal and expressive to evoke emotions or provide sensory details.

- Gladd, J. (2020). Tips for Writing Academic Persuasive Essays. Write What Matters .

- Nimehchisalem, V. (2018). Pyramid of argumentation: Towards an integrated model for teaching and assessing ESL writing. Language & Communication , 5 (2), 185-200.

- Press, B. (2022). Argumentative Essays: A Step-by-Step Guide . Broadview Press.

- Rieke, R. D., Sillars, M. O., & Peterson, T. R. (2005). Argumentation and critical decision making . Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

- What is a Narrative Essay? How to Write It (with Examples)

Make Your Research Paper Error-Free with Paperpal’s Online Spell Checker

The do’s & don’ts of using generative ai tools ethically in academia, you may also like, dissertation printing and binding | types & comparison , what is a dissertation preface definition and examples , how to write a research proposal: (with examples..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), maintaining academic integrity with paperpal’s generative ai writing..., research funding basics: what should a grant proposal..., how to write an abstract in research papers....

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write an Argumentative Essay

4-minute read

- 30th April 2022

An argumentative essay is a structured, compelling piece of writing where an author clearly defines their stance on a specific topic. This is a very popular style of writing assigned to students at schools, colleges, and universities. Learn the steps to researching, structuring, and writing an effective argumentative essay below.

Requirements of an Argumentative Essay

To effectively achieve its purpose, an argumentative essay must contain:

● A concise thesis statement that introduces readers to the central argument of the essay

● A clear, logical, argument that engages readers

● Ample research and evidence that supports your argument

Approaches to Use in Your Argumentative Essay

1. classical.

● Clearly present the central argument.

● Outline your opinion.

● Provide enough evidence to support your theory.

2. Toulmin

● State your claim.

● Supply the evidence for your stance.

● Explain how these findings support the argument.

● Include and discuss any limitations of your belief.

3. Rogerian

● Explain the opposing stance of your argument.

● Discuss the problems with adopting this viewpoint.

● Offer your position on the matter.

● Provide reasons for why yours is the more beneficial stance.

● Include a potential compromise for the topic at hand.

Tips for Writing a Well-Written Argumentative Essay

● Introduce your topic in a bold, direct, and engaging manner to captivate your readers and encourage them to keep reading.

● Provide sufficient evidence to justify your argument and convince readers to adopt this point of view.

● Consider, include, and fairly present all sides of the topic.

● Structure your argument in a clear, logical manner that helps your readers to understand your thought process.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● Discuss any counterarguments that might be posed.

● Use persuasive writing that’s appropriate for your target audience and motivates them to agree with you.

Steps to Write an Argumentative Essay

Follow these basic steps to write a powerful and meaningful argumentative essay :

Step 1: Choose a topic that you’re passionate about

If you’ve already been given a topic to write about, pick a stance that resonates deeply with you. This will shine through in your writing, make the research process easier, and positively influence the outcome of your argument.

Step 2: Conduct ample research to prove the validity of your argument

To write an emotive argumentative essay , finding enough research to support your theory is a must. You’ll need solid evidence to convince readers to agree with your take on the matter. You’ll also need to logically organize the research so that it naturally convinces readers of your viewpoint and leaves no room for questioning.

Step 3: Follow a simple, easy-to-follow structure and compile your essay

A good structure to ensure a well-written and effective argumentative essay includes:

Introduction

● Introduce your topic.

● Offer background information on the claim.

● Discuss the evidence you’ll present to support your argument.

● State your thesis statement, a one-to-two sentence summary of your claim.

● This is the section where you’ll develop and expand on your argument.

● It should be split into three or four coherent paragraphs, with each one presenting its own idea.

● Start each paragraph with a topic sentence that indicates why readers should adopt your belief or stance.

● Include your research, statistics, citations, and other supporting evidence.

● Discuss opposing viewpoints and why they’re invalid.

● This part typically consists of one paragraph.

● Summarize your research and the findings that were presented.

● Emphasize your initial thesis statement.

● Persuade readers to agree with your stance.

We certainly hope that you feel inspired to use these tips when writing your next argumentative essay . And, if you’re currently elbow-deep in writing one, consider submitting a free sample to us once it’s completed. Our expert team of editors can help ensure that it’s concise, error-free, and effective!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

5-minute read

Free Email Newsletter Template (2024)

Promoting a brand means sharing valuable insights to connect more deeply with your audience, and...

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write An Argumentative Essay

Table of Contents

Crafting a convincing argumentative essay can be challenging. You might feel lost about where to begin. But with a systematic approach and helpful tools that simplify sourcing and structuring, mastering good argumentative essay writing becomes achievable.

In this article, we'll explore what argumentative essays are, the critical steps to crafting a compelling argumentative essay, and best practices for essay organization.

What is an argumentative essay?

An argumentative essay asserts a clear position on a controversial or debatable topic and backs it up with evidence and reasoning. They are written to hone critical thinking, structure clear arguments, influence academic and public discourse, underpin reform proposals, and change popular narratives.

The fundamentals of a good argumentative essay

Let's explore the essential components that make argumentative essays compelling.

1 . The foundation: crafting a compelling claim for your argumentative essay

The claim is the cornerstone of your argumentative essay. It represents your main argument or thesis statement , setting the stage for the discussion.

A robust claim is straightforward, debatable, and focused, challenging readers to consider your viewpoint. It's not merely an observation but a stance you're prepared to defend with logic and evidence.

The strength of your essay hinges on the clarity and assertiveness of your claim, guiding readers through your argumentative journey.

2. The structure: Organizing your argument strategically

An effective argumentative essay should follow a logical structure to present your case persuasively. There are three models for structuring your argument essay:

- Classical: Introduce the topic, present the main argument, address counterarguments, and conclude . It is ideal for complex topics and prioritizes logical reasoning.

- Rogerian: Introduce the issue neutrally, acknowledge opposing views, find common ground, and seek compromise. It works well for audiences who dislike confrontational approaches.

- Toulmin: Introduce the issue, state the claim, provide evidence, explain the reasoning, address counterarguments, and reinforce the original claim. It confidently showcases an evidence-backed argument as superior.

Each model provides a framework for methodically supporting your position using evidence and logic. Your chosen structure depends on your argument's complexity, audience, and purpose.

3. The support: Leveraging evidence for your argumentative essay

The key is to select evidence that directly supports your claim, lending weight to your arguments and bolstering your position.

Effective use of evidence strengthens your argument and enhances your credibility, demonstrating thorough research and a deep understanding of the topic at hand.

4. The balance: Acknowledging counterarguments for the argumentative essay

A well-rounded argumentative essay acknowledges that there are two sides to every story. Introducing counterarguments and opposing viewpoints in an argument essay is a strategic move that showcases your awareness of alternative viewpoints.

This element of your argumentative essay demonstrates intellectual honesty and fairness, indicating that you have considered other perspectives before solidifying your position.

5. The counter: Mastering the art of rebuttal

A compelling rebuttal anticipates the counterclaims and methodically counters them, ensuring your position stands unchallenged. By engaging critically with counterarguments in this manner, your essay becomes more resilient and persuasive.

Ultimately, the strength of an argumentative essay is not in avoiding opposing views but in directly confronting them through reasoned debate and evidence-based.

How to write an argumentative essay

The workflow for crafting an effective argumentative essay involves several key steps:

Step 1 — Choosing a topic

Argumentative essay writing starts with selecting a topic with two or more main points so you can argue your position. Avoid topics that are too broad or have a clear right or wrong answer.

Use a semantic search engine to search for papers. Refine by subject area, publication date, citation count, institution, author, journal, and more to narrow down on promising topics. Explore citation interlinkages to ensure you pick a topic with sufficient academic discourse to allow crafting a compelling, evidence-based argument.

Seek an AI research assistant's help to assess a topic's potential and explore various angles quickly. They can generate both generic and custom questions tailored to each research paper. Additionally, look for tools that offer browser extensions . These allow you to interact with papers from sources like ArXiv, PubMed, and Wiley and evaluate potential topics from a broader range of academic databases and repositories.

Step 2 — Develop a thesis statement

Your thesis statement should clearly and concisely state your position on the topic identified. Ensure to develop a clear thesis statement which is a focused, assertive declaration that guides your discussion. Use strong, active language — avoid vague or passive statements. Keep it narrowly focused enough to be adequately supported in your essay.

The SciSpace literature review tool can help you extract thesis statements from existing papers on your chosen topic. Create a custom column called 'thesis statement' to compare multiple perspectives in one place, allowing you to uncover various viewpoints and position your concise thesis statement appropriately.

Ask AI assistants questions or summarize key sections to clarify the positions taken in existing papers. This helps sharpen your thesis statement stance and identify gaps. Locate related papers in similar stances.

Step 3 — Researching and gathering evidence

The evidence you collect lends credibility and weight to your claims, convincing readers of your viewpoint. Effective evidence includes facts, statistics, expert opinions, and real-world examples reinforcing your thesis statement.

Use the SciSpace literature review tool to locate and evaluate high-quality studies. It quickly extracts vital insights, methodologies, findings, and conclusions from papers and presents them in a table format. Build custom tables with your uploaded PDFs or bookmarked papers. These tables can be saved for future reference or exported as CSV for further analysis or sharing.

AI-powered summarization tools can help you quickly grasp the core arguments and positions from lengthy papers. These can condense long sections or entire author viewpoints into concise summaries. Make PDF annotations to add custom notes and highlights to papers for easy reference. Data extraction tools can automatically pull key statistics from PDFs into spreadsheets for detailed quantitative analysis.

Step 4 — Build an outline

The argumentative model you choose will impact your outline's specific structure and progression. If you select the Classical model, your outline will follow a linear structure. On the other hand, if you opt for the Toulmin model, your outline will focus on meticulously mapping out the logical progression of your entire argument. Lastly, if you select the Rogerian model, your outline should explore the opposing viewpoint and seek a middle ground.

While the specific outline structure may vary, always begin the process by stating your central thesis or claim. Identify and organize your argument claims and main supporting points logically, adding 2-3 pieces of evidence under each point. Consider potential counterarguments to your position. Include 1-2 counterarguments for each main point and plan rebuttals to dismantle the opposition's reasoning. This balanced approach strengthens your overall argument.

As you outline, consider saving your notes, highlights, AI-generated summaries, and extracts in a digital notebook. Aggregating all your sources and ideas in one centralized location allows you to quickly refer to them as you draft your outline and essay.

To further enhance your workflow, you can use AI-powered writing or GPT tools to help generate an initial structure based on your crucial essay components, such as your thesis statement, main arguments, supporting evidence, counterarguments, and rebuttals.

Step 5 — Write your essay

Begin the introductory paragraph with a hook — a question, a startling statistic, or a bold statement to draw in your readers. Always logically structure your arguments with smooth transitions between ideas. Ensure the body paragraphs of argumentative essays focus on one central point backed by robust quantitative evidence from credible studies, properly cited.

Refer to the notes, highlights, and evidence you've gathered as you write. Organize these materials so that you can easily access and incorporate them into your draft while maintaining a logical flow. Literature review tables or spreadsheets can be beneficial for keeping track of crucial evidence from multiple sources.

Quote others in a way that blends seamlessly with the narrative flow. For numerical data, contextualize figures with practical examples. Try to pre-empt counterarguments and systematically dismantle them. Maintain an evidence-based, objective tone that avoids absolutism and emotional appeals. If you encounter overly complex sections during the writing process, use a paraphraser tool to rephrase and clarify the language. Finally, neatly tie together the rationale behind your position and directions for further discourse or research.

Step 6 — Edit, revise, and add references

Set the draft aside so that you review it with fresh eyes. Check for clarity, conciseness, logical flow, and grammar. Ensure the body reflects your thesis well. Fill gaps in reasoning. Check that every claim links back to credible evidence. Replace weak arguments. Finally, format your citations and bibliography using your preferred style.

To simplify editing, save the rough draft or entire essay as a PDF and upload it to an AI-based chat-with-PDF tool. Use it to identify gaps in reasoning, weaker arguments requiring ample evidence, structural issues hampering the clarity of ideas, and suggestions for strengthening your essay.

Use a citation tool to generate citations for sources instantly quoted and quickly compile your bibliography or works cited in RIS/BibTex formats. Export the updated literature review tables as handy CSV files to share with co-authors or reviewers in collaborative projects or attach them as supplementary data for journal submissions. You can also refer to this article that provides you with argumentative essay writing tips .

Final thoughts

Remember, the strength of your argumentative essay lies in the clarity of your strong argument, the robustness of supporting evidence, and the consideration with which you treat opposing viewpoints. Refining these core skills will make you a sharper, more convincing writer and communicator.

You might also like

Smallpdf vs SciSpace: Which ChatPDF is Right for You?

ChatPDF Showdown: SciSpace Chat PDF vs. Adobe PDF Reader

Boosting Citations: A Comparative Analysis of Graphical Abstract vs. Video Abstract

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

3 Strong Argumentative Essay Examples, Analyzed

General Education

Need to defend your opinion on an issue? Argumentative essays are one of the most popular types of essays you’ll write in school. They combine persuasive arguments with fact-based research, and, when done well, can be powerful tools for making someone agree with your point of view. If you’re struggling to write an argumentative essay or just want to learn more about them, seeing examples can be a big help.

After giving an overview of this type of essay, we provide three argumentative essay examples. After each essay, we explain in-depth how the essay was structured, what worked, and where the essay could be improved. We end with tips for making your own argumentative essay as strong as possible.

What Is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is an essay that uses evidence and facts to support the claim it’s making. Its purpose is to persuade the reader to agree with the argument being made.

A good argumentative essay will use facts and evidence to support the argument, rather than just the author’s thoughts and opinions. For example, say you wanted to write an argumentative essay stating that Charleston, SC is a great destination for families. You couldn’t just say that it’s a great place because you took your family there and enjoyed it. For it to be an argumentative essay, you need to have facts and data to support your argument, such as the number of child-friendly attractions in Charleston, special deals you can get with kids, and surveys of people who visited Charleston as a family and enjoyed it. The first argument is based entirely on feelings, whereas the second is based on evidence that can be proven.

The standard five paragraph format is common, but not required, for argumentative essays. These essays typically follow one of two formats: the Toulmin model or the Rogerian model.

- The Toulmin model is the most common. It begins with an introduction, follows with a thesis/claim, and gives data and evidence to support that claim. This style of essay also includes rebuttals of counterarguments.

- The Rogerian model analyzes two sides of an argument and reaches a conclusion after weighing the strengths and weaknesses of each.

3 Good Argumentative Essay Examples + Analysis

Below are three examples of argumentative essays, written by yours truly in my school days, as well as analysis of what each did well and where it could be improved.

Argumentative Essay Example 1

Proponents of this idea state that it will save local cities and towns money because libraries are expensive to maintain. They also believe it will encourage more people to read because they won’t have to travel to a library to get a book; they can simply click on what they want to read and read it from wherever they are. They could also access more materials because libraries won’t have to buy physical copies of books; they can simply rent out as many digital copies as they need.

However, it would be a serious mistake to replace libraries with tablets. First, digital books and resources are associated with less learning and more problems than print resources. A study done on tablet vs book reading found that people read 20-30% slower on tablets, retain 20% less information, and understand 10% less of what they read compared to people who read the same information in print. Additionally, staring too long at a screen has been shown to cause numerous health problems, including blurred vision, dizziness, dry eyes, headaches, and eye strain, at much higher instances than reading print does. People who use tablets and mobile devices excessively also have a higher incidence of more serious health issues such as fibromyalgia, shoulder and back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, and muscle strain. I know that whenever I read from my e-reader for too long, my eyes begin to feel tired and my neck hurts. We should not add to these problems by giving people, especially young people, more reasons to look at screens.

Second, it is incredibly narrow-minded to assume that the only service libraries offer is book lending. Libraries have a multitude of benefits, and many are only available if the library has a physical location. Some of these benefits include acting as a quiet study space, giving people a way to converse with their neighbors, holding classes on a variety of topics, providing jobs, answering patron questions, and keeping the community connected. One neighborhood found that, after a local library instituted community events such as play times for toddlers and parents, job fairs for teenagers, and meeting spaces for senior citizens, over a third of residents reported feeling more connected to their community. Similarly, a Pew survey conducted in 2015 found that nearly two-thirds of American adults feel that closing their local library would have a major impact on their community. People see libraries as a way to connect with others and get their questions answered, benefits tablets can’t offer nearly as well or as easily.

While replacing libraries with tablets may seem like a simple solution, it would encourage people to spend even more time looking at digital screens, despite the myriad issues surrounding them. It would also end access to many of the benefits of libraries that people have come to rely on. In many areas, libraries are such an important part of the community network that they could never be replaced by a simple object.

The author begins by giving an overview of the counter-argument, then the thesis appears as the first sentence in the third paragraph. The essay then spends the rest of the paper dismantling the counter argument and showing why readers should believe the other side.

What this essay does well:

- Although it’s a bit unusual to have the thesis appear fairly far into the essay, it works because, once the thesis is stated, the rest of the essay focuses on supporting it since the counter-argument has already been discussed earlier in the paper.

- This essay includes numerous facts and cites studies to support its case. By having specific data to rely on, the author’s argument is stronger and readers will be more inclined to agree with it.

- For every argument the other side makes, the author makes sure to refute it and follow up with why her opinion is the stronger one. In order to make a strong argument, it’s important to dismantle the other side, which this essay does this by making the author's view appear stronger.

- This is a shorter paper, and if it needed to be expanded to meet length requirements, it could include more examples and go more into depth with them, such as by explaining specific cases where people benefited from local libraries.

- Additionally, while the paper uses lots of data, the author also mentions their own experience with using tablets. This should be removed since argumentative essays focus on facts and data to support an argument, not the author’s own opinion or experiences. Replacing that with more data on health issues associated with screen time would strengthen the essay.

- Some of the points made aren't completely accurate , particularly the one about digital books being cheaper. It actually often costs a library more money to rent out numerous digital copies of a book compared to buying a single physical copy. Make sure in your own essay you thoroughly research each of the points and rebuttals you make, otherwise you'll look like you don't know the issue that well.

Argumentative Essay Example 2