The Roman Empire and Its Fall in 476 A.D. Essay

Introduction.

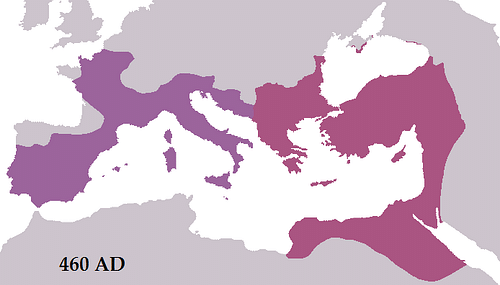

The fall of Rome is widely considered a major turning point in the history of Europe. The Roman Empire, which had been a major political and military force since the 1st century B.C., collapsed in the late 5th century A.D. The causes of the fall of Rome were complex and varied, but the consequences were seismic. Rome was eventually divided in 395 A.D by the death of Theodosius I, with the East becoming the Byzantine Empire and the West becoming the Western Roman Empire. This continued to exist in some form until 476 A.D, when it was officially dissolved by the Germanic King Odoacer. Therefore, although Rome fell in 476 A.D due to deposition of Emperor Romulus Augustulus, some of its practices such as religion and political system were continued while others were discontinued.

The fall of the Roman Empire is traditionally dated to be 476 A.D, when the emperor of the Western Empire, Romulus Augustulus. This marked the end of the Roman imperial system and the transition to the Middle Ages. Despite this, many of the continuities between Rome and its successor kingdoms can be seen throughout the 5th century and beyond. The Byzantine Empire, which emerged in the East, claimed to be the legitimate successor of the Roman Empire, and its rulers continued to use the title of ‘Emperor.’ The Byzantine Empire maintained much of the Roman political, legal, and religious traditions, including the Greek language and Christian faith.

One of the main continuities that can be seen after the fall of Rome was the continued presence of a strong and unified Christian faith. Despite the rise of the Ostrogothic, Visigothic and Frankish kingdoms, Rome and its legacy of Catholic Christianity remained a major unifying force throughout Europe. This was further reinforced by the growth of the Holy Roman Empire from Charlemagne, which further spread the influence of Catholicism. Additionally, the claims of the Papacy to be the legitimate heirs of Roman imperial rule in the West helped to maintain a sense of continuity after the fall of Rome. Thus, the successor states maintained much of the Roman political, legal, and religious traditions, including the Greek language and Christian faith.

However, there were some discontinuities such as adoption of a new form of government adopted by Roman Empire’s successor kingdoms. The most significant of these was the decentralization of power, as the Ostrogothic, Visigothic and Frankish kingdoms replaced the unified Roman Empire. This led to the emergence of a number of new political entities, which competed for power and influence in Europe. Additionally, the decline of the Roman Empire led to a decline in the level of technological sophistication and economic prosperity that the Romans had enjoyed. Therefore, this decline in the standard of living was further exacerbated by the emergence of new diseases and the decline of trade networks

The fall of the Roman Empire in 476 A.D. marked the end of the classical period and the beginning of the Middle Ages. The continuities and discontinuities between Rome and its successor kingdoms depend largely on the region in question, but all of them adopted some of the Roman traditions and institutions while developing their unique characteristics. The Byzantine Empire is among the successors that sustained Roman traditions the longest. However, the claims made by the Papacy to be the legitimate heirs of Roman imperial rule in the West were declared with the Donation of Constantine in the 8th century.

- The Ancient Roman Aqueducts and Their Structure

- Comparison of Sumerian and Egyptian Civilization

- Business & Empire – The British Ideal of an Orderly World

- Webvan Online Company Challenges

- Rome' and Avignon Fighting over the Papacy

- Civilized Nations vs. Barbarians in History

- Ancient Civilizations: Thriving and Downfall

- The Democracies of Ancient Greece and the Roman Republic

- The Parthenon: An Artifact Analysis

- Kingship in the Ancient Near East

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, January 9). The Roman Empire and Its Fall in 476 A.D. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-roman-empire-and-its-fall-in-476-ad/

"The Roman Empire and Its Fall in 476 A.D." IvyPanda , 9 Jan. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/the-roman-empire-and-its-fall-in-476-ad/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'The Roman Empire and Its Fall in 476 A.D'. 9 January.

IvyPanda . 2024. "The Roman Empire and Its Fall in 476 A.D." January 9, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-roman-empire-and-its-fall-in-476-ad/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Roman Empire and Its Fall in 476 A.D." January 9, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-roman-empire-and-its-fall-in-476-ad/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Roman Empire and Its Fall in 476 A.D." January 9, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-roman-empire-and-its-fall-in-476-ad/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

Fall of the Western Roman Empire

To many historians, the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE has always been viewed as the end of the ancient world and the onset of the Middle Ages, often improperly called the Dark Ages, despite Petrarch 's assertion. Since much of the west had already fallen by the middle of the 5th century CE, when a writer speaks of the fall of the empire , he or she generally refers to the fall of the city of Rome . Although historians generally agree on the year of the fall, 476 CE, and its consequences for western civilization , they often disagree on its causes. English historian Edward Gibbon , who wrote in the late 18th century CE, points to the rise of Christianity and its effect on the Roman psyche while others believe the decline and fall were due, in part, to the influx of 'barbarians' from the north and west.

Whatever the cause, whether it was religion , external attack, or the internal decay of the city itself, the debate continues to the present day; however, one significant point must be established before a discussion of the roots of the fall can continue: the decline and fall were only in the west. The eastern half - that which would eventually be called the Byzantine Empire - would continue for several centuries, and, in many ways, it retained a unique Roman identity.

External Causes

One of the most widely accepted causes - the influx of a barbarian tribes - is discounted by some who feel that mighty Rome, the eternal city, could not have so easily fallen victim to a culture that possessed little or nothing in the way of a political, social or economic foundation. They believe the fall of Rome simply came because the barbarians took advantage of difficulties already existing in Rome - problems that included a decaying city (both physically and morally), little to no tax revenue, overpopulation, poor leadership, and, most importantly, inadequate defense. To some the fall was inevitable.

Unlike the fall of earlier empires such as the Assyrian and Persian, Rome did not succumb to either war or revolution. On the last day of the empire, a barbarian member of the Germanic tribe Siri and former commander in the Roman army entered the city unopposed. The one-time military and financial power of the Mediterranean was unable to resist. Odovacar easily dethroned the sixteen-year-old emperor Romulus Augustalus, a person he viewed as posing no threat. Romulus had recently been named emperor by his father, the Roman commander Orestes, who had overthrown the western emperor Julius Nepos. With his entrance into the city, Odovacar became the head of the only part that remained of the once great west: the peninsula of Italy . By the time he entered the city, the Roman control of Britain , Spain, Gaul , and North Africa had already been lost, in the latter three cases to the Goths and Vandals . Odovacar immediately contacted the eastern emperor Zeno and informed him that he would not accept that title of emperor. Zeno could do little but accept this decision. In fact, to ensure there would be no confusion, Odovacar returned to Constantinople the imperial vestments, diadem, and purple cloak of the emperor.

Internal Causes

There are some who believe, like Gibbon, that the fall was due to the fabric of the Roman citizen. If one accepts the idea that the cause of the fall was due, in part, to the possible moral decay of the city, its fall is reminiscent of the “decline” of the Republic centuries earlier. Historian Polybius , a 2nd century BCE writer, pointed to a dying republic (years before it actually fell) - a victim of its declining moral virtue and the rise of vice within. Edward Gibbon reiterated this sentiment (he diminished the importance of the barbaric threat) when he claimed the rise of Christianity as a factor in the “tale of woe” for the empire. He held the religion sowed internal division and encouraged a “turn-the-other-cheek mentality” which ultimately condemned the war machine, leaving it in the hands of the invading barbarians. Those who discount Gibbon's claim point to the existence of the same religious zealots in the east and the fact that many of the barbarians were Christian themselves.

To Gibbon the Christian religion valued idle and unproductive people. Gibbon wrote in his book The History of Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire ,

A candid but rational inquiry into the progress and establishment of Christianity, may be considered as a very essential part of the history of the Roman empire. While this great body was invaded by open violence, or undermined by slow decay, a pure and humble religion greatly insinuated itself into the minds of men, grew up in silence and obscurity, derived new vigour from opposition, and finally erected the triumphant banner of the cross on the ruins of the Capitol.”

He added that the Roman government appeared to be “odious and oppressive to its subjects” and therefore no serious threat to the barbarians.

Gibbon, however, does not single out Christianity as the only culprit. It was only one in a series that brought the empire to its knees. In the end, the fall was inevitable:

…the decline of Rome was the natural and inevitable effect of immoderate greatness. Prosperity ripened the principle of decay; the causes of destruction multiplied with the extent of conquest , and as soon as time or accident has removed artificial supports, the stupendous fabric yielded to the pressure of its own weight.

A Divided Empire

Although Gibbon points to the rise of Christianity as a fundamental cause, the actual fall or decline could be seen decades earlier. By the 3rd century CE, the city of Rome was no longer the center of the empire - an empire that extended from the British Isles to the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers and into Africa. This massive size presented a problem and called for a quick solution, and it came with the reign of Emperor Diocletian . The empire was divided into two with one capital remaining at Rome and another in the Eastern Empire at Nicomedia; the eastern capital would later be moved to Constantinople, old Byzantium , by Emperor Constantine . The Senate, long-serving in an advisory capacity to the emperor, would be mostly ignored; instead, the power centered on a strong military. Some emperors would never step foot in Rome. In time Constantinople, Nova Roma or New Rome, would become the economic and cultural center that had once been Rome.

Despite the renewed strength that the division provided (the empire would be divided and united several times), the empire remained vulnerable to attack, especially on the Danube-Rhine border to the north. The presence of barbarians along the northern border of the empire was nothing new and had existed for years - the army had met with them on and off since the time of Julius Caesar . Some emperors had tried to buy them off, while others invited them to settle on Roman land and even join the army. However, many of these new settlers never truly became Roman even after citizenship was granted, retaining much of their old culture.

This vulnerability became more obvious as a significant number of Germanic tribes, the Goths, gathered along the northern border. They did not want to invade; they wanted to be part of the empire, not its conqueror. The empire's great wealth was a draw to this diverse population. They sought a better life, and despite their numbers, they appeared to be no immediate threat, at first. However, as Rome failed to act to their requests, tensions grew. This anxiety on the part of the Goths was due to a new menace further to the east, the Huns .

The Goth Invasion

During the reign of the 4th century eastern emperor Valens (364 -378 CE), the Thervingi Goths had congregated along the Danube-Rhine border - again, not as a threat, but with a desire only to receive permission to settle. This request was made in urgency, for the “savage” Huns threatened their homeland. Emperor Valens panicked and delayed an answer - a delay that brought increased concern among the Goths as winter was approaching. In anger, the Goths crossed the river with or without permission, and when a Roman commander planned an ambush, war soon followed. It was a war that would last for five years.

Although the Goths were mostly Christian many who joined them were not. Their presence had caused a substantial crisis for the emperor; he couldn't provide sufficient food and housing. This impatience, combined with the corruption and extortion by several Roman commanders, complicated matters. Valens prayed for help from the west. Unfortunately, in battle , the Romans were completely outmatched and ill-prepared, and the Battle of Adrianople proved this when two-thirds of the Roman army was killed. This death toll included the emperor himself. It would take Emperor Theodosius to bring peace.

An Enemy from Within: Alaric

The Goths remained on Roman land and would ally themselves with the Roman army. Later, however, one man, a Goth and former Roman commander, rose up against Rome - a man who only asked for what had been promised him - a man who would do what no other had done for eight centuries: sack Rome. His name was Alaric, and while he was a Goth, he had also been trained in the Roman army. He was intelligent, Christian, and very determined. He sought land in the Balkans for his people, land that they had been promised. Later, as the western emperor delayed his response, Alaric increased his demands, not only grain for his people but also recognition as citizens of the empire; however, the emperor, Honorius, continually refused. With no other course, Alaric gathered together an army of Goths, Huns and freed slaves and crossed the Alps into Italy. His army was well-organized, not a mob. Honorius was incompetent and completely out of touch, another in a long line of so-called “shadow emperors” - emperors who ruled in the shadow of the military. Oddly enough, he didn't even live in Rome but had a villa in nearby Ravenna.

Alaric sat outside the city, and over time, as the food and water in the city became increasingly scarce, Rome began to weaken. The time was now. While he had never wanted war but only land and recognition for his people Alaric, with the supposed help of a Gothic slave who opened the gates from within, entered Rome in August of 410 CE. He would stay for three days and completely sack the city; although he would leave St. Paul and St Peters alone. Honorius remained totally blind to the seriousness of the situation. While temporarily agreeing to Alaric's demands - something he never intended to honor - 6,000 Roman soldiers were sent to defend the city, but they were quickly defeated. Even though the city's coffers were nearly empty, the Senate finally relinquished; Alaric left with, among other items, two tons of gold and thirteen tons of silver .

Some people at the time viewed the sacking of the city as a sign from their pagan gods. St. Augustine , who died in 430 CE, said in his City of God that the fall of Rome was not a result of the people's abandonment of their pagan gods (gods they believed protected the city) but as a reminder to the city's Christians why they needed to suffer. There was good, for the world was created by good, but it was flawed by human sin; however, he still believed the empire was a force for peace and unity. To St. Augustine there existed two cities : one of this world and one of God.

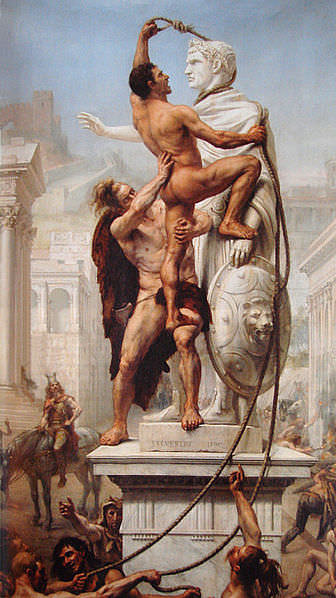

Barbarian Invasions

Although Alaric would soon die afterwards, other barbarians - whether Christian or not - did not stop after the sack of the city. The old empire was ravaged, among others, by Burgundians, Angles, Saxons , Lombards , and Magyars. By 475 CE Spain, Britain, and parts of Gaul had been lost to various Germanic people and only Italy remained as the “empire” in the west. The Vandals would soon move from Spain and into northern Africa, eventually capturing the city of Carthage . The Roman army abandoned all hope of recovering the area and moved out. The loss of Africa meant a loss of revenue, and the loss of revenue meant there was less money to support an army to defend the city. Despite these considerable losses, there was some success for the Romans. The threat from Attila the Hun was finally stopped at the Battle of Chalons by Roman commander Aelius who had created an army of Goths, Franks , Celts and Burgundians. Even Gibbon recognized Attila as one “who urged the rapid downfall of the Roman empire.” While Attila would recover and sack several Italian cities, he and the Hun threat ended with his death due to a nosebleed on his wedding night.

Conclusion: Multiple Factors

One could make a sound case for a multitude of reasons for the fall of Rome. However, its fall was not due to one cause, although many search for one. Most of the causes, initially, point to one place: the city of Rome itself. The loss of revenue for the western half of the empire could not support an army - an army that was necessary for defending the already vulnerable borders. Continual warfare meant trade was disrupted; invading armies caused crops to be laid to waste, poor technology made for low food production, the city was overcrowded, unemployment was high, and lastly, there were always the epidemics. Added to these was an inept and untrustworthy government.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

The presence of the barbarians in and around the empire added to a crisis not only externally but internally. These factors helped bring an empire from “a state of health into non-existence.” The Roman army lacked both proper training and equipment. The government itself was unstable. Peter Heather in his The Fall of the Roman Empire states that it “fell not because of its 'stupendous fabric' but because its German neighbors responded to its power in ways that the Romans could not ever have foreseen… By virtue of its unbounded aggression, Roman imperialism was responsible for its own destruction.”

Rome's fall ended the ancient world and the Middle Ages were borne. These “Dark Ages” brought the end to much that was Roman. The West fell into turmoil. However, while much was lost, western civilization still owes a debt to the Romans. Although only a few today can speak Latin, it is part of our language and the foundation of the Romance languages of French, Italian, and Spanish. Our legal system is based on Roman law . Many present day European cities were founded by Rome. Our knowledge of Greece comes though Rome and many other lasting effects besides. Rome had fallen but it had been for so so long one of the history's truly world cities.

Subscribe to topic Bibliography Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Baker, S. Ancient Rome. BBC Books, 2007.

- Clark, G. Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Gibbon, E. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Penguin Classics, 2005.

- Heather, P. The Fall of the Roman Empire. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- James, E. Europe's Barbarians AD 200-600. Routledge, 2009.

- Rodgers, N. Roman Empire. Metro Books, 2008

- Sommer, M. The Complete Roman Emperor. Thames & Hudson, 2010.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language!

Related Content

Emperor Zeno

Free for the World, Supported by You

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

In this age of AI and fake news, access to accurate information is crucial. Every month our fact-checked encyclopedia enables millions of people all around the globe to learn about history, for free. Please support free history education for only $5 per month!

Cite This Work

Wasson, D. L. (2018, April 12). Fall of the Western Roman Empire . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/835/fall-of-the-western-roman-empire/

Chicago Style

Wasson, Donald L.. " Fall of the Western Roman Empire ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified April 12, 2018. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/835/fall-of-the-western-roman-empire/.

Wasson, Donald L.. " Fall of the Western Roman Empire ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 12 Apr 2018. Web. 13 Oct 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Donald L. Wasson , published on 12 April 2018. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

- Humanities ›

- History & Culture ›

- Ancient History and Culture ›

The Fall of Rome: How, When, and Why Did It Happen?

Illustration by Emily Roberts. ThoughtCo.

- Figures & Events

- Ancient Languages

- Mythology & Religion

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- M.A., Linguistics, University of Minnesota

- B.A., Latin, University of Minnesota

The phrase "the Fall of Rome" suggests that some cataclysmic event ended the Roman Empire, which stretched from the British Isles to Egypt and Iraq. But in the end, there was no straining at the gates, no barbarian horde that dispatched the Roman Empire in one fell swoop.

Instead, the Roman Empire fell slowly as a result of challenges from within and without, changing throughout hundreds of years until its form was unrecognizable. Because of the long process, different historians have placed an end date at many different points on a continuum. Perhaps the Fall of Rome is best understood as a compilation of various maladies that altered a large swath of human habitation over many hundreds of years.

When Did Rome Fall?

In his masterwork, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire , historian Edward Gibbon selected 476 CE, a date most often mentioned by historians. That date was when Odoacer, the Germanic king of the Torcilingi, deposed Romulus Augustulus, the last Roman emperor to rule the western part of the Roman Empire. The eastern half became the Byzantine Empire, with its capital Constantinople (modern Istanbul).

But the city of Rome continued to exist. Some see the rise of Christianity as putting an end to the Romans; those who disagree with that find the rise of Islam a more fitting bookend to the end of the empire—but that would put the Fall of Rome at Constantinople in 1453! In the end, the arrival of Odoacer was but one of many barbarian incursions into the empire. Certainly, the people who lived through the takeover would probably be surprised by the importance we place on determining an exact event and time.

How Did Rome Fall?

Just as the Fall of Rome was not caused by a single event, the way Rome fell was also complex. In fact, during the period of imperial decline, the empire actually expanded. That influx of conquered peoples and lands changed the structure of the Roman government. Emperors moved the capital away from the city of Rome, too. The schism of east and west created not just an eastern capital first in Nicomedia (in what is now Turkey) and then Constantinople, but also a move in the west from Rome to Milan.

Rome started out as a small, hilly settlement by the Tiber River in the middle of the Italian boot, surrounded by more powerful neighbors. By the time Rome became an empire, the territory covered by the term "Rome" looked completely different. It reached its greatest extent in the second century CE. Some of the arguments about the Fall of Rome focus on the geographic diversity and the territorial expanse that Roman emperors and their legions had to control.

Why Did Rome Fall?

This is easily the most argued question about the fall of Rome. The Roman Empire lasted over a thousand years and represented a sophisticated and adaptive civilization. Some historians maintain that it was the split into eastern and western empires governed by separate emperors that caused Rome to fall.

Most classicists believe that a combination of factors including Christianity, decadence, the metal lead in the water supply, monetary trouble, and military problems caused the Fall of Rome. Imperial incompetence and chance could be added to that list. And still, others question the assumption behind the question and maintain that the Roman Empire didn't fall so much as adapt to changing circumstances.

Christianity

R Rumora (2012) Institute for the Study of the Ancient World

When the Roman Empire started, there was no such religion as Christianity. In the 1st century CE, Pontius Pilate, the governor of the province of Judaea, executed their founder, Jesus, for treason. It took his followers a few centuries to gain enough clout to be able to win over imperial support. This began in the early 4th century with Emperor Constantine , who was actively involved in Christian policy-making.

When Constantine established state-level religious tolerance in the Roman Empire, he took on the title of Pontiff. Although he was not necessarily a Christian himself (he wasn't baptized until he was on his deathbed), he gave Christians privileges and oversaw major Christian religious disputes. He may not have understood how the pagan cults, including those of the emperors, were at odds with the new monotheistic religion, but they were, and in time the old Roman religions lost out.

Over time, Christian church leaders became increasingly influential, eroding the emperors' powers. For example, when Bishop Ambrose (340–397 CE) threatened to withhold the sacraments, Emperor Theodosius did the penance the Bishop assigned him. Emperor Theodosius made Christianity the official religion in 390 CE. Since Roman civic and religious life were deeply connected—priestesses controlled the fortune of Rome, prophetic books told leaders what they needed to do to win wars, and emperors were deified—Christian religious beliefs and allegiances conflicted with the working of empire.

Barbarians and Vandals

The barbarians, which is a term that covers a varied and changing group of outsiders, were embraced by Rome, who used them as suppliers of tax revenue and bodies for the military, even promoting them to positions of power. But Rome also lost territory and revenue to them, especially in northern Africa, which Rome lost to the Vandals at the time of St. Augustine in the early 5th century CE.

At the same time the Vandals took over the Roman territory in Africa, Rome lost Spain to the Sueves, Alans, and Visigoths . The loss of Spain meant Rome lost revenue along with the territory and administrative control, a perfect example of the interconnected causes leading to Rome's fall. That revenue was needed to support Rome's army and Rome needed its army to keep what territory it still maintained.

Decadence and Decay of Rome's Control

There is no doubt that decay—the loss of Roman control over the military and populace—affected the ability of the Roman Empire to keep its borders intact. Early issues included the crises of the Republic in the first century BCE under the emperors Sulla and Marius as well as that of the Gracchi brothers in the second century CE. But by the fourth century, the Roman Empire had simply become too big to control easily.

The decay of the army, according to the 5th-century Roman historian Vegetius , came from within the army itself. The army grew weak from a lack of wars and stopped wearing their protective armor. This made them vulnerable to enemy weapons and provided the temptation to flee from battle. Security may have led to the cessation of the rigorous drills. Vegetius said the leaders became incompetent and rewards were unfairly distributed.

In addition, as time went on, Roman citizens, including soldiers and their families living outside of Italy, identified with Rome less and less compared to their Italian counterparts. They preferred to live as natives, even if this meant poverty which, in turn, meant they turned to those who could help—Germans, brigands, Christians, and Vandals.

Lead Poisoning

Some scholars have suggested that the Romans suffered from lead poisoning. Studies have shown that there was lead in Roman drinking water, leached in from water pipes used in the vast Roman water control system; lead glazes on containers that came in contact with food and beverages; and food preparation techniques that could have contributed to heavy metal poisoning. Lead was also used in cosmetics, even though it was already known in Roman times as a deadly poison and used in contraception.

Economic factors are also often cited as a major cause of the fall of Rome. Some of the major factors described are inflation, over-taxation, and feudalism. Other lesser economic issues included the wholesale hoarding of bullion by Roman citizens, the widespread looting of the Roman treasury by barbarians, and a massive trade deficit with the eastern regions of the empire. Together these issues combined to escalate financial stress during the empire's last days.

Additional References

- Baynes, Norman H. “The Decline of the Roman Power in Western Europe. Some Modern Explanations.” The Journal of Roman Studies , vol. 33, no. 1-2, Nov. 1943, pp. 29–35.

- Dorjahn, Alfred P., and Lester K. Born. “Vegetius on the Decay of the Roman Army.” The Classical Journal , vol. 30, no. 3, Dec. 1934, pp. 148–158.

- Phillips, Charles Robert. “Old Wine in Old Lead Bottles: Nriagu on the Fall of Rome.” The Classical World , vol. 78, no. 1, Sept. 1984, pp. 29–33.

Gibbon, Edward. History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. London: Strahan & Cadell, 1776.

Ott, Justin. "The Decline and Fall of the Western Roman Empire." Iowa State University Capstones, Theses, and Dissertations . Iowa State University, 2009.

Damen, Mark. "The Fall of Rome: Facts and Fictions." A Guide to Writing in History and Classics. Utah State University.

Delile, Hugo, et al. “ Lead in Ancient Rome's City Waters. ” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , vol. 111, no. 18, 6 May 2014, pp. 6594–6599., doi:10.1073/pnas.1400097111

- A Short Timeline of the Fall of the Roman Empire

- Reasons for the Fall of Rome

- The End of the Roman Empire

- Early Rome and the Issue of the 'King'

- Roman Republic

- What Was Life Like During the Pax Romana?

- Alaric, King of the Visigoths and the Sack of Rome in A.D. 410

- The End of the Republic of Rome

- Periods of History in Ancient Rome

- How Were Julius Caesar and His Successor Augustus Related?

- Selected Books on Roman History

- Economic Reasons for the Fall of Rome

- Roman Baths and Hygiene in Ancient Rome

- The Ides of March

- Homosexuality in Ancient Rome

- The 7 Famous Hills of Rome

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- The Guardian - The 100 best nonfiction books: No 83 – The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon (1776-1788)

- Academia - Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

- World History Encyclopedia - Gibbon's Decline & Fall of the Roman Empire

- Christian Classics Ethereal Library - The History of The Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire

- Internet Archive - "The decline and fall of the Roman Empire"

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire , historical work by Edward Gibbon , published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788. A continuous narrative from the 2nd century ce to the fall of Constantinople in 1453, it is distinguished by its rigorous scholarship, its historical perspective, and its incomparable literary style.

The Decline and Fall is divided into two parts, equal in bulk but different in treatment. The first half covers about 300 years to the end of the empire in the West, about 480 ce ; in the second half nearly 1,000 years are compressed. Gibbon viewed the Roman Empire as a single entity in undeviating decline from the ideals of political and intellectual freedom that characterized the classical literature he had read. For him, the material decay of Rome was the effect and symbol of moral decadence.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

8 Reasons Why Rome Fell

By: Evan Andrews

Updated: September 5, 2023 | Original: January 14, 2014

1. Invasions by Barbarian tribes

The most straightforward theory for Western Rome’s collapse pins the fall on a string of military losses sustained against outside forces. Rome had tangled with Germanic tribes for centuries, but by the 300s “barbarian” groups like the Goths had encroached beyond the Empire’s borders. The Romans weathered a Germanic uprising in the late fourth century, but in 410 the Visigoth King Alaric successfully sacked the city of Rome.

The Empire spent the next several decades under constant threat before “the Eternal City” was raided again in 455, this time by the Vandals. Finally, in 476, the Germanic leader Odoacer staged a revolt and deposed Emperor Romulus Augustulus. From then on, no Roman emperor would ever again rule from a post in Italy, leading many to cite 476 as the year the Western Empire suffered its death blow.

2. Economic troubles and overreliance on slave labor

Even as Rome was under attack from outside forces, it was also crumbling from within thanks to a severe financial crisis. Constant wars and overspending had significantly lightened imperial coffers, and oppressive taxation and inflation had widened the gap between rich and poor. In the hope of avoiding the taxman, many members of the wealthy classes had even fled to the countryside and set up independent fiefdoms.

At the same time, the empire was rocked by a labor deficit. Rome’s economy depended on slaves to till its fields and work as craftsmen, and its military might had traditionally provided a fresh influx of conquered peoples to put to work. But when expansion ground to a halt in the second century, Rome’s supply of slaves and other war treasures began to dry up. A further blow came in the fifth century, when the Vandals claimed North Africa and began disrupting the empire’s trade by prowling the Mediterranean as pirates. With its economy faltering and its commercial and agricultural production in decline, the Empire began to lose its grip on Europe.

3. The rise of the Eastern Empire

The fate of Western Rome was partially sealed in the late third century, when Emperor Diocletian divided the Empire into two halves—the Western Empire seated in the city of Milan, and the Eastern Empire in Byzantium, later known as Constantinople. The division made the empire more easily governable in the short term, but over time the two halves drifted apart. East and West failed to adequately work together to combat outside threats, and the two often squabbled over resources and military aid.

As the gulf widened, the largely Greek-speaking Eastern Empire grew in wealth while the Latin-speaking West descended into an economic crisis. Most importantly, the strength of the Eastern Empire served to divert Barbarian invasions to the West. Emperors like Constantine ensured that the city of Constantinople was fortified and well guarded, but Italy and the city of Rome—which only had symbolic value for many in the East—were left vulnerable. The Western political structure would finally disintegrate in the fifth century, but the Eastern Empire endured in some form for another thousand years before being overwhelmed by the Ottoman Empire in the 1400s.

How Far Did Ancient Rome Spread?

At its peak, Rome stretched over much of Europe and the Middle East.

5 Ways Christianity Spread Through Ancient Rome

Sure, the Roman Empire had that extensive road system. But it helped that early Christians didn't paint themselves as an exclusive club.

6 Civil Wars that Transformed Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome waged many campaigns of conquest during its history, but its most influential wars may have been the ones it fought against itself.

4. Overexpansion and military overspending

At its height, the Roman Empire stretched from the Atlantic Ocean all the way to the Euphrates River in the Middle East, but its grandeur may have also been its downfall. With such a vast territory to govern, the empire faced an administrative and logistical nightmare. Even with their excellent road systems, the Romans were unable to communicate quickly or effectively enough to manage their holdings.

Rome struggled to marshal enough troops and resources to defend its frontiers from local rebellions and outside attacks, and by the second century, the Emperor Hadrian was forced to build his famous wall in Britain just to keep the enemy at bay. As more and more funds were funneled into the military upkeep of the empire, technological advancement slowed and Rome’s civil infrastructure fell into disrepair.

5. Government corruption and political instability

If Rome’s sheer size made it difficult to govern, ineffective and inconsistent leadership only served to magnify the problem. Being the Roman emperor had always been a particularly dangerous job, but during the tumultuous second and third centuries it nearly became a death sentence. Civil war thrust the empire into chaos, and more than 20 men took the throne in the span of only 75 years, usually after the murder of their predecessor.

The Praetorian Guard—the emperor’s personal bodyguards—assassinated and installed new sovereigns at will, and once even auctioned the spot off to the highest bidder. The political rot also extended to the Roman Senate, which failed to temper the excesses of the emperors due to its own widespread corruption and incompetence. As the situation worsened, civic pride waned and many Roman citizens lost trust in their leadership.

6. The arrival of the Huns and the migration of the Barbarian tribes

The Barbarian attacks on Rome partially stemmed from a mass migration caused by the Huns’ invasion of Europe in the late fourth century. When these Eurasian warriors rampaged through northern Europe, they drove many Germanic tribes to the borders of the Roman Empire. The Romans grudgingly allowed members of the Visigoth tribe to cross south of the Danube and into the safety of Roman territory, but they treated them with extreme cruelty.

According to the historian Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman officials even forced the starving Goths to trade their children into slavery in exchange for dog meat. In brutalizing the Goths, the Romans created a dangerous enemy within their own borders. When the oppression became too much to bear, the Goths rose up in revolt and eventually routed a Roman army and killed the Eastern Emperor Valens during the Battle of Adrianople in A.D. 378. The shocked Romans negotiated a flimsy peace with the barbarians, but the truce unraveled in 410, when the Goth King Alaric moved west and sacked Rome. With the Western Empire weakened, Germanic tribes like the Vandals and the Saxons were able to surge across its borders and occupy Britain, Spain and North Africa.

7. Christianity and the loss of traditional values

The decline of Rome dovetailed with the spread of Christianity, and some have argued that the rise of a new faith helped contribute to the empire’s fall. The Edict of Milan legalized Christianity in 313, and it later became the state religion in 380. These decrees ended centuries of persecution, but they may have also eroded the traditional Roman values system. Christianity displaced the polytheistic Roman religion, which viewed the emperor as having a divine status, and also shifted focus away from the glory of the state and onto a sole deity.

Meanwhile, popes and other church leaders took an increased role in political affairs, further complicating governance. The 18th-century historian Edward Gibbon was the most famous proponent of this theory, but his take has since been widely criticized. While the spread of Christianity may have played a small role in curbing Roman civic virtue, most scholars now argue that its influence paled in comparison to military, economic and administrative factors.

8. Weakening of the Roman legions

For most of its history, Rome’s military was the envy of the ancient world. But during the decline, the makeup of the once mighty legions began to change. Unable to recruit enough soldiers from the Roman citizenry, emperors like Diocletian and Constantine began hiring foreign mercenaries to prop up their armies. The ranks of the legions eventually swelled with Germanic Goths and other barbarians, so much so that Romans began using the Latin word “barbarus” in place of “soldier.”

While these Germanic soldiers of fortune proved to be fierce warriors, they also had little or no loyalty to the empire, and their power-hungry officers often turned against their Roman employers. In fact, many of the barbarians who sacked the city of Rome and brought down the Western Empire had earned their military stripes while serving in the Roman legions.

Steps Leading to the Fall of Rome

- A.D. 285 First split

- A.D. 378 Battle of Adrianople

- A.D. 395 Final split

- A.D. 410 Visigoths sack Rome

- A.D. 439 Vandals capture Carthage

- A.D. 455 Vandals sack Rome

- A.D. 476 Western Roman Emperor deposed

Between 235 and 284, more than 20 Roman emperors take the throne in a chaotic period known as the Crisis of the Third Century . This period ends when Diocletian becomes emperor and divides the Roman Empire into eastern and western regions, each ruled by its own emperor. This divided rule lasts until 324 when Constantine the Great reunifies Rome. More

The Roman military suffers one of its worst defeats at the Battle of Adrianople . Led by Eastern Emperor Valens, Rome loses an estimated 10,000 troops while fighting against the Visigoths and other Germanic peoples. Valens dies in battle, and the defeat in the east paves the way for attacks in the west. More

After Valens’ death in the Battle of Adrianople, Theodosius I becomes the new eastern emperor. In 394, he defeats Eugenius, the proclaimed western emperor. Theodosius executes Eugenius and briefly reunifies the empire under his rule. However, his death in 395 divides the empire between his two sons, Arcadius and Honorius.

In 410, Visigoths successfully enter and sack the city of Rome . According to legend, this attack marks the first time an outside force has sacked Rome since 387 B.C., nearly 800 years before. More

Three decades after the Visigoths sack Rome, a different group of Germanic people called the Vandals capture Carthage, one of the largest cities in the Western Roman Empire. After capturing the ancient city, the Vandals declare it their new capital. This marks another significant victory for Germanic peoples against the Western Roman Empire. More

During the early 450s, the Western Roman Empire successfully fights off attempts by Attila the Hun and his forces to invade Roman territory. However, in 455 the Vandals invade and sack the city of Rome. This attack eventually helps turn the Vandals’ name into another word for people who destroy property. More

In 476, a Germanic soldier named Odoacer deposes the last western Roman emperor, Romulus Augustulus , and proclaims himself king of Italy. This marks the traditional end of the Western Roman Empire; but not the end of the Eastern Roman Empire, or Byzantine Empire , which flourishes for another millennium.

HISTORY Vault: Rome: Engineering an Empire

The thirst for power shared by all Roman emperors fueled an unprecedented mastery of engineering and labor. Explore the engineering feats that set the Roman Empire apart from the rest of the ancient world.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

History Cooperative

The Fall of Rome: When, Why, and How Did Rome Fall?

The fall of Rome and of the Western Roman Empire was a complex process driven by a combination of economic, political, military, and social factors, along with external barbarian invasions. It took place over several centuries and culminated in the deposition of the last Roman emperor in 476 CE.

Table of Contents

When Did Rome Fall?

The generally agreed-upon date for the fall of Rome is September 4, 476 AD. On this date, the Germanic king Odaecer stormed the city of Rome and deposed its emperor, leading to its collapse.

But the story of the fall of Rome is not this simple. By this point in the Roman Empire timeline , there were two empires, the Eastern and Western Roman empires.

READ MORE: The Foundation of Rome: The Birth of an Ancient Power

Whilst the western empire fell in 476 AD, the eastern half of the empire lived on, transformed into the Byzantine Empire, and flourished until 1453. Nevertheless, it is the fall of the Western Empire that has most captured the hearts and minds of later thinkers and has been immortalized in debate as “the fall of Rome.”

The Effects of the Fall of Rome

Although debate continues around the exact nature of what followed, the demise of the Western Roman Empire has traditionally been depicted as the demise of civilization in Western Europe. Matters in the East carried on, much as they always had (with “Roman” power now centered on Byzantium (modern Istanbul), but the West experienced a collapse of centralized, imperial Roman infrastructure.

Again, according to traditional perspectives, this collapse led to the “Dark Ages” of instability and crises that beset much of Europe. No longer could cities and communities look to Rome, Roman emperors , or formidable Roman army ; moving forward there would be a splintering of the Roman world into a number of different polities, many of which were controlled by Germanic “barbarians” (a term used by the Romans to describe anyone who wasn’t Roman), from the northeast of Europe.

Such a transition has fascinated thinkers, from the time it was actually happening, up until the modern day. For modern political and social analysts, it is a complex but captivating case study, that many experts still explore to find answers about how superpower states can collapse.

How Did Rome Fall?

Rome did not fall overnight. Instead, the fall of the Western Roman Empire was the result of a process that took place over the course of several centuries. It came about due to political and financial instability and invasions from Germanic tribes moving into Roman territories.

The Story of the Fall of Rome

To give some background and context to the fall of the Roman Empire (in the West), it is necessary to go as far back as the second century AD. During much of this century, Rome was ruled by the famous “ Five Good Emperors ” who made up most of the Nerva-Antonine Dynasty. Whilst this period was heralded as a “kingdom of gold” by the historian Cassius Dio , largely due to its political stability and territorial expansion, the empire has been seen to undergo a steady decline after it.

There were periods of relative stability and peace that came after the Nerva-Antonine’s, fostered by the Severans (a dynasty started by Septimius Severus ), the Tetrarchy , and Constantine the Great . Yet, none of these periods of peace really strengthened the frontiers or the political infrastructure of Rome; none set the empire on a long-term trajectory of improvement.

Moreover, even during the Nerva-Antonines, the precarious status quo between the emperors and the senate was beginning to unravel. Under the “Five Good Emperors,” power was increasingly centered on the emperor – a recipe for success in those times under “Good” Emperors, but it was inevitable that less praiseworthy emperors would follow, leading to corruption and political instability.

Then came Commodus , who designated his duties to greedy confidants and made the city of Rome his plaything. After he was murdered by his wrestling partner, the “High Empire” of the Nerva-Antonines came to an abrupt close. What followed, after a vicious civil war, was the military absolutism of the Severans, where the ideal of a military monarch took prominence and the murder of these monarchs became the norm.

The Crisis of the Third Century

Soon came the Crisis of the Third Century after the last Severan, Severus Alexander , was assassinated in 235 AD. During this infamous fifty-year period the Roman Empire was beset by repeated defeats in the east – to the Persians, and in the north, to Germanic invaders.

READ MORE: Ancient Persia: From the Achaemenid Empire to the History of Iran

It also witnessed the chaotic secession of several provinces, which revolted as a result of poor management and a lack of regard from the center. Additionally, the empire was beset by a serious financial crisis that reduced the silver content of the coinage so far that it practically became useless. Moreover, there were recurrent civil wars that saw the empire ruled by a long succession of short-lived emperors.

READ MORE: Roman Wars

Such a lack of stability was compounded by the humiliation and tragic end of the emperor Valerian , who spent the final years of his life as a captive under the Persian king Shapur I. In this miserable existence, he was forced to stoop and serve as a mounting block to help the Persian king mount and dismount his horse.

When he finally succumbed to death in 260 AD, his body was flayed and his skin was kept as a permanent humiliation. Whilst this was no doubt an ignominious symptom of Rome’s decline, Emperor Aurelian soon took power in 270 AD and won an unprecedented number of military victories against the innumerable enemies who had wreaked havoc on the empire.

In the process, he reunited the sections of territory that had broken off to become the short-lived Gallic and Palmyrene Empires. Rome for the time being recovered. Yet figures like Aurelian were rare occurrences and the relative stability the empire had experienced under the first three or four dynasties did not return.

READ MORE: Gallic Empire

Diocletian and the Tetrarchy

In 293 AD the emperor Diocletian sought to find a solution to the empire’s recurrent problems by establishing the Tetrarchy, also known as the rule of four. As the name suggests, this involved splitting the empire into four divisions, each ruled by a different emperor – two senior ones titled “Augusti,” and two junior ones called “Caesares,” each ruling their portion of territory.

Such an agreement lasted until 324 AD, when Constantine the Great retook control of the whole empire, having defeated his last opponent Licinius (who had ruled in the east, whereas Constantine had begun his power grab in the northwest of Europe). Constantine certainly stands out in the history of the Roman Empire, not only for reuniting it under one person’s rule and reigning over the empire for 31 years but also for being the emperor who brought Christianity to the center of the state infrastructure.

READ MORE: How Did Christianity Spread: Origins, Expansion, and Impact

Many scholars and analysts have pointed to the spread and cementing of Christianity as the state religion as an important, if not fundamental cause for Rome’s fall.

READ MORE: Roman Religion

Whilst Christians had been persecuted sporadically under different emperors, Constantine was the first to become baptized (on his deathbed). Additionally, he patronized the buildings of many churches and basilicas, elevated clergy to high-ranking positions, and gave a substantial amount of land to the church.

On top of all this, Constantine is famous for renaming the city of Byzantium as Constantinople and for endowing it with considerable funding and patronage. This set the precedent for later rulers to embellish the city, which eventually became the seat of power for the Eastern Roman Empire.

The Rule of Constantine

Constantine’s reign however, as well as his enfranchisement of Christianity, did not provide a wholly reliable solution to the problems that still beset the empire. Chief amongst these included an increasingly expensive army, threatened by an increasingly dwindling population (especially in the west). Straight after Constantine, his sons degenerated into civil war, splitting the empire in two again in a story that really seems very representative of the empire since its heyday under the Nerva-Antonines.

There were intermittent periods of stability for the remainder of the 4 th century AD, with rare rulers of authority and ability, such as Valentinian I and Theodosius . Yet by the beginning of the 5 th century, most analysts argue, things began to fall apart.

The Fall of Rome Itself: Invasions from the North

Similar to the chaotic invasions seen in the Third Century, the beginning of the 5 th century AD witnessed an immense number of “barbarians” crossing over into Roman territory, caused amongst other reasons by the spread of warmongering Huns from northeastern Europe.

This started with the Goths (constituted by the Visigoths and Ostrogoths ), which first breached the frontiers of the Eastern Empire in the late 4 th century AD.

Although they routed an Eastern army at Hadrianopolis in 378 AD and then turned to blunder much of the Balkans, they soon turned their attentions to the Western Roman Empire, along with other Germanic peoples.

These included the Vandals , Suebes , and Alans, who crossed the Rhine in 406/7 AD and recurrently laid waste to Gaul, Spain, and Italy. Moreover, the Western Empire they faced was not the same force that enabled the campaigns of the warlike emperors Trajan , Septimius Severus , or Aurelian.

Instead, it was greatly weakened and as many contemporaries noted, had lost effective control of many of its frontier provinces. Rather than looking to Rome, many cities and provinces had begun to rely on themselves for relief and refuge.

This, combined with the historic loss at Hadrianopolis, on top of recurrent bouts of civil discord and rebellion, meant that the door was practically open for marauding armies of Germans to take what they liked. This included not only large swathes of Gaul (much of modern-day France), Spain, Britain, and Italy, but Rome itself.

Indeed, after they had plundered their way through Italy from 401 AD onwards, the Goths sacked Rome in 410 AD – something that had not happened since 390 BC! After this travesty and the devastation that was wrought upon the Italian countryside, the government granted tax exemption to large swathes of the population, even though it was sorely needed for defense.

A Weakened Rome Faces Increased Pressure from Invaders

Much the same story was mirrored in Gaul and Spain, wherein the former was a chaotic and contested war zone between a litany of different peoples, and in the latter, the Goths and Vandals had free reign to their riches and people. At the time, many Christian writers wrote as though the apocalypse had reached the western half of the empire, from Spain to Britain.

The barbarian hordes are depicted as ruthless and avaricious plunderers of everything they can set their eyes upon, in terms of both wealth and women. Confused by what had caused this now-Christian empire to succumb to such catastrophe, many Christian writers blamed the invasions on the sins of the Roman Empire, past and present.

Yet neither penance nor politics could help salvage the situation for Rome, as the successive emperors of the 5 th century AD were largely unable or unwilling to meet the invaders in much decisive, open battles. Instead, they tried to pay them off or failed to raise sufficiently large armies to defeat them.

The Roman Empire on the Verge of Bankruptcy

Moreover, whilst the emperors in the west still had the rich citizens of North Africa paying tax, they could just about afford to field new armies (many of the soldiers in fact taken from various barbarian tribes), but that source of income was soon to be devastated as well. In 429 AD, in a significant development, the Vandals crossed over the strait of Gibraltar and within 10 years, had effectively taken control of Roman North Africa.

This was perhaps the final blow from which Rome was unable to recover. It was by this point the case that much of the empire in the west had fallen into barbarian hands and the Roman emperor and his government did not have the resources to take these territories back. In some instances, lands were granted to different tribes in return for peaceful coexistence or military allegiance, although such terms were not always kept.

By now the Huns had begun to arrive along the fringes of the old Roman frontiers in the west, united behind the terrifying figure of Attila. He had previously led campaigns with his brother Bleda against the Eastern Roman Empire in the 430s and 440s, only to turn his eyes west when a senator’s betrothed astonishingly appealed to him for help.

He claimed her as his bride in waiting and half of the Western Roman Empire as his dowry! Unsurprisingly this was not met with much acceptance by the emperor Valentinian III , and so Attila headed westwards from the Balkans laying waste to large swathes of Gaul and Northern Italy.

In a famous episode in 452 AD, he was stopped from actually besieging the city of Rome, by a delegation of negotiators, including Pope Leo I. The next year Attila died from a hemorrhage, after which the Hunnic peoples soon broke up and disintegrated, to the joy of both Roman and German alike.

Whilst there had been some successful battles against the Huns throughout the first half of the 450s, much of this was won by the help of the Goths and other Germanic tribes. Rome had effectively ceased to be the securer of peace and stability it had once been, and its existence as a separate political entity, no doubt appeared increasingly dubious.

This was compounded by the fact that this period was also punctuated by constant rebellions and revolts in the lands still nominally under Roman rule, as other tribes such as the Lombards, Burgundians, and Franks had established footholds in Gaul.

Rome’s Final Breath

One of these rebellions in 476 AD finally gave the fatal blow, led by a Germanic general named Odoacer, who deposed the last emperor of the Western Roman Empire, Romulus Augustulus . He styled himself as both “dux” (king) and client to the Eastern Roman Empire. But was soon deposed by the Ostrogoth king Theodoric the Great .

Henceforth, from 493 AD the Ostrogoths ruled Italy, the Vandals North Africa, the Visigoths Spain and parts of Gaul, the rest of which was controlled by Franks, Burgundians, and the Suebes (who also ruled parts of Spain and Portugal). Across the channel, the Anglo-Saxons had for some time ruled much of Britain.

There was a time, under the reign of Justinian the Great when the Eastern Roman Empire retook Italy, North Africa, and parts of Southern Spain, yet these conquests were only temporary and constituted the expansion of the new Byzantine Empire, rather than the Roman Empire of Antiquity. Rome and its empire had fallen, never again to reach its former glory.

Why Did Rome Fall?

Since the fall of Rome in 476 and indeed before that fateful year itself, arguments for the empire’s decline and collapse have come and gone over time. Whilst the English historian Edward Gibbon articulated the most famous and well-established arguments in his seminal work, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire , his inquiry, and his explanation, are only one of many.

For example, in 1984 a German historian listed a total of 210 reasons that had been given for the fall of the Roman Empire, ranging from excessive bathing (which apparently caused impotency and demographic decline) to excessive deforestation.

Many of these arguments have often aligned with the sentiments and fashions of the time. For instance, in the 19 th and 20 th centuries, the fall of Roman civilization was explained through the reductionist theories of racial or class degeneration that were prominent in certain intellectual circles.

Around the time of the fall as well – as has already been alluded to – contemporary Christians blamed the disintegration of the empire on the last remaining vestiges of Paganism, or the unrecognized sins of professed Christians. The parallel view, at the time and subsequently popular with an array of different thinkers (including Edward Gibbon) was that Christianity had caused the fall.

The Barbarian Invasions and the Fall of Rome

The immediate cause of the empire’s fall was the unprecedented number of barbarians, aka those living outside Roman territory, invading the lands of Rome.

Of course, the Romans had had their fair share of barbarians on their doorstep, considering they were constantly involved in different conflicts along their long frontiers. In that sense, their security had always been somewhat precarious, especially as they needed a professionally manned army to protect their empire.

These armies needed constant replenishment, due to the retirement or death of soldiers in their ranks. Mercenaries could be used from different regions inside or outside the empire, but these were almost always sent home after their term of service, whether it was for a single campaign or several months.

As such, the Roman army needed a constant and colossal supply of soldiers, which it began to increasingly struggle to procure as the population of the empire continued to decrease (from the 2 nd century onwards). This meant more reliance on barbarian mercenaries, which could not always be as readily relied upon to fight for a civilization they felt little fealty towards.

Pressure on the Roman Borders

At the end of the 4 th century AD, hundreds of thousands, if not millions of Germanic peoples, migrated westwards towards the Roman frontiers. The traditional (and still most commonly asserted) reason given for this is that the nomadic Huns spread out from their homeland in Central Asia, attacking Germanic tribes as they went.

This forced a mass migration of Germanic peoples to escape the wrath of the dreaded Huns by entering Roman territory. Therefore, unlike in previous campaigns along their northeastern frontier, the Romans were facing a prodigious mass of peoples united in common purpose, whereas they had, up until now, been infamous for their internecine squabbles and resentments. This unity was simply too much for Rome to handle.

Yet, this tells only half of the story and is an argument that has not satisfied most later thinkers who wanted to explain the fall in terms of the internal issues entrenched in the empire itself. It seems that these migrations were for the most part, out of Roman control, but why did they fail so miserably to either repel the barbarians or accommodate them within the empire, as they had previously done with other problematic tribes across the frontier?

Edward Gibbon and His Arguments for the Fall

Edward Gibbon was perhaps the most famous figure to address these questions and has, for the most part, been heavily influential for all subsequent thinkers. Besides the aforementioned barbarian invasions, Gibbon blamed the fall on the inevitable decline all empires faced, the degeneration of civic virtues in the empire, the waste of precious resources, and the emergence and subsequent domination of Christianity.

Each cause is given significant stress by Gibbon, who essentially believed that the empire had experienced a gradual decline in its morals, virtues, and ethics, yet his critical reading of Christianity was the accusation that caused the most controversy at the time.

The Role of Christianity According to Gibbon

As with the other explanations given, Gibbon saw in Christianity an enervating characteristic that sapped the empire not only of its wealth (going to churches and monasteries) but also its warlike persona that had molded its image for much of its early and middle history.

Whilst the writers of the Roman Republic and early empire encouraged manliness and service to one’s state, Christian writers impelled allegiance to God and discouraged conflict between his people. The world had not yet experienced the religiously endorsed Crusades that would see Christians wage war against non-Christians. Moreover, many of the Germanic peoples who entered the empire were themselves Christian!

Outside of these religious contexts, Gibbon saw the Roman Empire rotting from within, more focused on the decadence of its aristocracy and the vainglory of its militaristic emperors, than the long-term health of its empire. Since the heyday of the Nerva-Antonines, the Roman Empire had experienced crisis after crisis exacerbated in large part by poor decisions and megalomaniacal, disinterested, or avaricious rulers. Inevitably, Gibbon argued, this had to catch up with them.

Economic Mismanagement of the Empire

Whilst Gibbon did point out how wasteful Rome was with its resources, he did not really delve too heavily into the economics of the empire. However, this is where many recent historians have pointed the finger, and is with the other arguments already mentioned, one of the main stances taken up by later thinkers.

It has been well noted that Rome did not really have a cohesive or coherent economy in the more modern developed sense. It raised taxes to pay for its defense but did not have a centrally planned economy in any meaningful sense, outside of the considerations it made for the army.

There was no department of education or health; things were run on more of a case-by-case, or emperor-by-emperor basis. Programmes were carried out on sporadic initiatives and the vast majority of the empire was agrarian, with some specialized hubs of industry dotted about.

It did however have to raise taxes for its defense and this came at a colossal cost to the imperial coffers. For example, it is estimated that the pay needed for the whole army in 150 AD would constitute 60-80% of the imperial budget, leaving little room for periods of disaster or invasion.

Whilst soldier pay was initially contained, it was recurrently increased as time went by (partly because of increasing inflation). Emperors would also tend to pay donatives to the army when becoming emperor – a very costly affair if an emperor only lasted a short amount of time (as was the case from the Third Century Crisis onwards).

This was therefore a ticking time bomb, which ensured that any massive shock to the Roman system – like endless hordes of barbarian invaders – would be increasingly difficult to deal with, until, they couldn’t be dealt with at all. Indeed, the Roman state likely ran out of money on a number of occasions throughout the 5 th century AD.

Continuity Beyond the Fall: Did Rome Really Collapse?

On top of arguing about the causes of the Roman Empire’s fall in the West, scholars are also racked in debate about whether there was an actual fall or collapse at all. Similarly, they question whether we should so readily call to mind the apparent “dark ages” that followed the dissolution of the Roman state as it had existed in the West.

Traditionally, the end of the Western Roman empire is supposed to have heralded the end of civilization itself. This image was molded by contemporaries who depicted the cataclysmic and apocalyptic series of events that surrounded the deposition of the last emperor. It was then compounded by later writers, especially during the Renaissance and Enlightenment, when the collapse of Rome was seen as a massive step backward in art and culture.

Indeed, Gibbon was instrumental in cementing this presentation for subsequent historians. Yet from as early as Henri Pirenne (1862-1935) scholars have argued for a strong element of continuity during and after the apparent decline. According to this picture, many of the provinces of the Western Roman Empire were already in some way detached from the Italian center and did not experience a seismic shift in their everyday life, as is usually depicted.

Revisionism in the Idea of “Late Antiquity”

This has developed in more recent scholarship into the idea of “Late Antiquity” to replace the cataclysmic idea of the “Dark Ages. One of its most prominent and celebrated proponents is Peter Brown, who has written extensively on the subject, pointing to the continuity of much Roman culture, politics, and administrative infrastructure, as well as the flourishing of Christian Art and literature.

According to Brown, as well as other proponents of this model, it is therefore misleading and reductionist to talk of a decline or fall of the Roman Empire, but instead to explore its “transformation.”

In this vein, the idea of barbarian invasions causing the collapse of a civilization has become deeply problematic. It has instead been argued that there was an (albeit complex) “accommodation” of the migrating Germanic populations that reached the empire’s borders around the turn of the 5 th century AD.

Such arguments point to the fact that various settlements and treaties were signed with the Germanic peoples, who were for the most part escaping the marauding Huns (and are therefore posed often as refugees or asylum seekers). One such settlement was the 419 Settlement of Aquitaine, where the Visigoths were granted land in the valley of the Garonne by the Roman state.

As has already been alluded to above, the Romans also had various Germanic tribes fighting alongside them in this period, most notably against the Huns. It is also undoubtedly clear that the Romans throughout their time as a Republic and a Principate, were very prejudiced against “the other” and would collectively assume that anybody beyond their borders was in many ways uncivilized.

This aligns with the fact that the (originally Greek) derogatory term “barbarian” itself, derived from the perception that such people spoke a coarse and simple language, repeating “bar bar bar” repeatedly.

The Continuation of Roman Administration

Regardless of this prejudice, it is also clear, as the historians discussed above have studied, that many aspects of Roman administration and culture did continue in the Germanic kingdoms and territories that replaced the Roman Empire in the West.

This included much of the law that was carried out by Roman magistrates (with Germanic additions), much of the administrative apparatus, and indeed everyday life, for most individuals, will have carried on quite similarly, differing in extent from place to place. Whilst we know that a lot of land was taken by the new German masters, and henceforth Goths would be privileged legally in Italy, or Franks in Gaul, many individual families would not have been affected too much.

This is because it was obviously easier for their new Visigoth, Ostrogoth, or Frankish overlords to keep much of the infrastructure in place that had worked so well up until then. In many instances and passages from contemporary historians, or edicts from Germanic rulers, it was also clear that they respected much about Roman culture and in a number of ways, wanted to preserve it; in Italy for instance the Ostrogoths claimed “The glory of the Goths is to protect the civil life of the Romans.”

Moreover, since many of them converted to Christianity, the continuity of the Church was taken for granted. There was therefore a lot of assimilations, with both Latin and Gothic being spoken in Italy for example and Gothic mustaches being sported by aristocrats, whilst clad in Roman clothing.

Issues with Revisionism

However, this change of opinion has inevitably been reversed as well in more recent academic work – particularly in Ward-Perkin’s The Fall of Rome – wherein he strongly states that violence and aggressive seizure of land was the norm, rather than the peaceful accommodation that many revisionists have suggested .

He argues that these scant treaties are given far too much attention and stress when practically all of them were clearly signed and agreed to by the Roman state under pressure – as an expedient solution to contemporary problems. Moreover, in quite typical fashion, the 419 Settlement of Aquitaine was mostly ignored by the Visigoths as they subsequently spread out and aggressively expanded far beyond their designated limits.

Aside from these issues with the narrative of “accommodation,” the archaeological evidence also demonstrates a sharp decline in standards of living between the 5 th and 7 th centuries AD, across all of the western Roman Empire’s former territories (albeit under varying degrees), strongly suggested a significant and profound “decline” or “fall” of a civilization.

READ MORE: Ancient Civilizations Timeline: The Complete List from Aboriginals to Incans

This is shown, in part, by the significant decrease of post-roman finds of pottery and other cookware across the West and the fact that what is found is considerably less durable and sophisticated. This rings true for buildings as well, which began to be made more often in perishable materials like wood (rather than stone) and were notably smaller in size and grandeur.

Coinage also completely disappeared in large parts of the old empire or regressed in quality. Alongside this, literacy and education seem to have been greatly reduced across communities and even the size of livestock shrunk considerably – to bronze-age levels! Nowhere was this regression more pronounced than in Britain, where the islands fell into pre-Iron Age levels of economic complexity.

READ MORE: Prehistory: Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic Periods, and More