Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Our Best Education Articles of 2020

In February of 2020, we launched the new website Greater Good in Education , a collection of free, research-based and -informed strategies and practices for the social, emotional, and ethical development of students, for the well-being of the adults who work with them, and for cultivating positive school cultures. Little did we know how much more crucial these resources would become over the course of the year during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Now, as we head back to school in 2021, things are looking a lot different than in past years. Our most popular education articles of 2020 can help you manage difficult emotions and other challenges at school in the pandemic, all while supporting the social-emotional well-being of your students.

In addition to these articles, you can also find tips, tools, and recommended readings in two resource guides we created in 2020: Supporting Learning and Well-Being During the Coronavirus Crisis and Resources to Support Anti-Racist Learning , which helps educators take action to undo the racism within themselves, encourage their colleagues to do the same, and teach and support their students in forming anti-racist identities.

Here are the 10 best education articles of 2020, based on a composite ranking of pageviews and editors’ picks.

Can the Lockdown Push Schools in a Positive Direction? , by Patrick Cook-Deegan: Here are five ways that COVID-19 could change education for the better.

How Teachers Can Navigate Difficult Emotions During School Closures , by Amy L. Eva: Here are some tools for staying calm and centered amid the coronavirus crisis.

Six Online Activities to Help Students Cope With COVID-19 , by Lea Waters: These well-being practices can help students feel connected and resilient during the pandemic.

Help Students Process COVID-19 Emotions With This Lesson Plan , by Maurice Elias: Music and the arts can help students transition back to school this year.

How to Teach Online So All Students Feel Like They Belong , by Becki Cohn-Vargas and Kathe Gogolewski: Educators can foster belonging and inclusion for all students, even online.

How Teachers Can Help Students With Special Needs Navigate Distance Learning , by Rebecca Branstetter: Kids with disabilities are often shortchanged by pandemic classroom conditions. Here are three tips for educators to boost their engagement and connection.

How to Reduce the Stress of Homeschooling on Everyone , by Rebecca Branstetter: A school psychologist offers advice to parents on how to support their child during school closures.

Three Ways to Help Your Kids Succeed at Distance Learning , by Christine Carter: How can parents support their children at the start of an uncertain school year?

How Schools Are Meeting Social-Emotional Needs During the Pandemic , by Frances Messano, Jason Atwood, and Stacey Childress: A new report looks at how schools have been grappling with the challenges imposed by COVID-19.

Six Ways to Help Your Students Make Sense of a Divisive Election , by Julie Halterman: The election is over, but many young people will need help understanding what just happened.

Train Your Brain to Be Kinder (video), by Jane Park: Boost your kindness by sending kind thoughts to someone you love—and to someone you don’t get along with—with a little guidance from these students.

From Othering to Belonging (podcast): We speak with john a. powell, director of the Othering & Belonging Institute, about racial justice, well-being, and widening our circles of human connection and concern.

About the Author

Greater good editors.

The pandemic has had devastating impacts on learning. What will it take to help students catch up?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, megan kuhfeld , megan kuhfeld senior research scientist - nwea @megankuhfeld jim soland , jim soland assistant professor, school of education and human development - university of virginia, affiliated research fellow - nwea @jsoland karyn lewis , and karyn lewis director, center for school and student progress - nwea @karynlew emily morton emily morton research scientist - nwea @emily_r_morton.

March 3, 2022

As we reach the two-year mark of the initial wave of pandemic-induced school shutdowns, academic normalcy remains out of reach for many students, educators, and parents. In addition to surging COVID-19 cases at the end of 2021, schools have faced severe staff shortages , high rates of absenteeism and quarantines , and rolling school closures . Furthermore, students and educators continue to struggle with mental health challenges , higher rates of violence and misbehavior , and concerns about lost instructional time .

As we outline in our new research study released in January, the cumulative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic achievement has been large. We tracked changes in math and reading test scores across the first two years of the pandemic using data from 5.4 million U.S. students in grades 3-8. We focused on test scores from immediately before the pandemic (fall 2019), following the initial onset (fall 2020), and more than one year into pandemic disruptions (fall 2021).

Average fall 2021 math test scores in grades 3-8 were 0.20-0.27 standard deviations (SDs) lower relative to same-grade peers in fall 2019, while reading test scores were 0.09-0.18 SDs lower. This is a sizable drop. For context, the math drops are significantly larger than estimated impacts from other large-scale school disruptions, such as after Hurricane Katrina—math scores dropped 0.17 SDs in one year for New Orleans evacuees .

Even more concerning, test-score gaps between students in low-poverty and high-poverty elementary schools grew by approximately 20% in math (corresponding to 0.20 SDs) and 15% in reading (0.13 SDs), primarily during the 2020-21 school year. Further, achievement tended to drop more between fall 2020 and 2021 than between fall 2019 and 2020 (both overall and differentially by school poverty), indicating that disruptions to learning have continued to negatively impact students well past the initial hits following the spring 2020 school closures.

These numbers are alarming and potentially demoralizing, especially given the heroic efforts of students to learn and educators to teach in incredibly trying times. From our perspective, these test-score drops in no way indicate that these students represent a “ lost generation ” or that we should give up hope. Most of us have never lived through a pandemic, and there is so much we don’t know about students’ capacity for resiliency in these circumstances and what a timeline for recovery will look like. Nor are we suggesting that teachers are somehow at fault given the achievement drops that occurred between 2020 and 2021; rather, educators had difficult jobs before the pandemic, and now are contending with huge new challenges, many outside their control.

Clearly, however, there’s work to do. School districts and states are currently making important decisions about which interventions and strategies to implement to mitigate the learning declines during the last two years. Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) investments from the American Rescue Plan provided nearly $200 billion to public schools to spend on COVID-19-related needs. Of that sum, $22 billion is dedicated specifically to addressing learning loss using “evidence-based interventions” focused on the “ disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on underrepresented student subgroups. ” Reviews of district and state spending plans (see Future Ed , EduRecoveryHub , and RAND’s American School District Panel for more details) indicate that districts are spending their ESSER dollars designated for academic recovery on a wide variety of strategies, with summer learning, tutoring, after-school programs, and extended school-day and school-year initiatives rising to the top.

Comparing the negative impacts from learning disruptions to the positive impacts from interventions

To help contextualize the magnitude of the impacts of COVID-19, we situate test-score drops during the pandemic relative to the test-score gains associated with common interventions being employed by districts as part of pandemic recovery efforts. If we assume that such interventions will continue to be as successful in a COVID-19 school environment, can we expect that these strategies will be effective enough to help students catch up? To answer this question, we draw from recent reviews of research on high-dosage tutoring , summer learning programs , reductions in class size , and extending the school day (specifically for literacy instruction) . We report effect sizes for each intervention specific to a grade span and subject wherever possible (e.g., tutoring has been found to have larger effects in elementary math than in reading).

Figure 1 shows the standardized drops in math test scores between students testing in fall 2019 and fall 2021 (separately by elementary and middle school grades) relative to the average effect size of various educational interventions. The average effect size for math tutoring matches or exceeds the average COVID-19 score drop in math. Research on tutoring indicates that it often works best in younger grades, and when provided by a teacher rather than, say, a parent. Further, some of the tutoring programs that produce the biggest effects can be quite intensive (and likely expensive), including having full-time tutors supporting all students (not just those needing remediation) in one-on-one settings during the school day. Meanwhile, the average effect of reducing class size is negative but not significant, with high variability in the impact across different studies. Summer programs in math have been found to be effective (average effect size of .10 SDs), though these programs in isolation likely would not eliminate the COVID-19 test-score drops.

Figure 1: Math COVID-19 test-score drops compared to the effect sizes of various educational interventions

Source: COVID-19 score drops are pulled from Kuhfeld et al. (2022) Table 5; reduction-in-class-size results are from pg. 10 of Figles et al. (2018) Table 2; summer program results are pulled from Lynch et al (2021) Table 2; and tutoring estimates are pulled from Nictow et al (2020) Table 3B. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are shown with vertical lines on each bar.

Notes: Kuhfeld et al. and Nictow et al. reported effect sizes separately by grade span; Figles et al. and Lynch et al. report an overall effect size across elementary and middle grades. We were unable to find a rigorous study that reported effect sizes for extending the school day/year on math performance. Nictow et al. and Kraft & Falken (2021) also note large variations in tutoring effects depending on the type of tutor, with larger effects for teacher and paraprofessional tutoring programs than for nonprofessional and parent tutoring. Class-size reductions included in the Figles meta-analysis ranged from a minimum of one to minimum of eight students per class.

Figure 2 displays a similar comparison using effect sizes from reading interventions. The average effect of tutoring programs on reading achievement is larger than the effects found for the other interventions, though summer reading programs and class size reduction both produced average effect sizes in the ballpark of the COVID-19 reading score drops.

Figure 2: Reading COVID-19 test-score drops compared to the effect sizes of various educational interventions

Source: COVID-19 score drops are pulled from Kuhfeld et al. (2022) Table 5; extended-school-day results are from Figlio et al. (2018) Table 2; reduction-in-class-size results are from pg. 10 of Figles et al. (2018) ; summer program results are pulled from Kim & Quinn (2013) Table 3; and tutoring estimates are pulled from Nictow et al (2020) Table 3B. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are shown with vertical lines on each bar.

Notes: While Kuhfeld et al. and Nictow et al. reported effect sizes separately by grade span, Figlio et al. and Kim & Quinn report an overall effect size across elementary and middle grades. Class-size reductions included in the Figles meta-analysis ranged from a minimum of one to minimum of eight students per class.

There are some limitations of drawing on research conducted prior to the pandemic to understand our ability to address the COVID-19 test-score drops. First, these studies were conducted under conditions that are very different from what schools currently face, and it is an open question whether the effectiveness of these interventions during the pandemic will be as consistent as they were before the pandemic. Second, we have little evidence and guidance about the efficacy of these interventions at the unprecedented scale that they are now being considered. For example, many school districts are expanding summer learning programs, but school districts have struggled to find staff interested in teaching summer school to meet the increased demand. Finally, given the widening test-score gaps between low- and high-poverty schools, it’s uncertain whether these interventions can actually combat the range of new challenges educators are facing in order to narrow these gaps. That is, students could catch up overall, yet the pandemic might still have lasting, negative effects on educational equality in this country.

Given that the current initiatives are unlikely to be implemented consistently across (and sometimes within) districts, timely feedback on the effects of initiatives and any needed adjustments will be crucial to districts’ success. The Road to COVID Recovery project and the National Student Support Accelerator are two such large-scale evaluation studies that aim to produce this type of evidence while providing resources for districts to track and evaluate their own programming. Additionally, a growing number of resources have been produced with recommendations on how to best implement recovery programs, including scaling up tutoring , summer learning programs , and expanded learning time .

Ultimately, there is much work to be done, and the challenges for students, educators, and parents are considerable. But this may be a moment when decades of educational reform, intervention, and research pay off. Relying on what we have learned could show the way forward.

Related Content

Megan Kuhfeld, Jim Soland, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek, Karyn Lewis

December 3, 2020

Lindsay Dworkin, Karyn Lewis

October 13, 2021

Education Policy K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Monica Bhatt, Jonathan Guryan, Jens Ludwig

June 3, 2024

Emily Markovich Morris, Laura Nóra, Richaa Hoysala, Max Lieblich, Sophie Partington, Rebecca Winthrop

May 31, 2024

Online only

9:30 am - 11:00 am EDT

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2023

Elementary school teachers’ perspectives about learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Aymee Alvarez-Rivero ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0489-5708 1 ,

- Candice Odgers 2 , 3 &

- Daniel Ansari ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7625-618X 1

npj Science of Learning volume 8 , Article number: 40 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

4142 Accesses

16 Altmetric

Metrics details

How did school closures affect student access to education and learning rates during the COVID-19 pandemic? How did teachers adapt to the new instructional contexts? To answer these questions, we distributed an online survey to Elementary School teachers ( N = 911) in the United States and Canada at the end of the 2020–2021 school year. Around 85.8% of participants engaged in remote instruction, and nearly half had no previous experience teaching online. Overall, this transition was challenging for most teachers and more than 50% considered they were not as effective in the classroom during remote instruction and reported not being able to deliver all the curriculum expected for their grade. Despite the widespread access to digital technologies in our sample, nearly 65% of teachers observed a drop in class attendance. More than 50% of participants observed a decline in students’ academic performance, a growth in the gaps between low and high-performing students, and predicted long-term adverse effects. We also observed consistent effects of SES in teachers’ reports. The proportion of teachers reporting a drop in performance increases from 40% in classrooms with high-income students, to more than 70% in classrooms with low-income students. Students in lower-income households were almost twice less likely to have teachers with previous experience teaching online and almost twice less likely to receive support from adults with homeschooling. Overall, our data suggest the effects of the pandemic were not equally distributed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Why lockdown and distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to increase the social class achievement gap

Large socio-economic, geographic and demographic disparities exist in exposure to school closures

Remote learning slightly decreased student performance in an introductory undergraduate course on climate change

Introduction.

The sudden onset of the COVID-19 pandemic had a profound effect on education worldwide 1 , 2 , with the aftermath of more than 180 countries experiencing school closures and more than 1.5 billion students left out of school 3 . Despite the efforts of governments and education institutions to provide alternative learning opportunities, the long periods that students had to spend away from the classroom have raised concerns about the potential long-term consequences on academic achievement, and the unequal effect that it will have on students from vulnerable and marginalized groups 4 , who had to navigate the challenges of at-home schooling while their families struggled with financial burdens 5 .

Empirical data about changes in students’ performance has been slow to emerge. One of the earliest pieces of evidence comes from a study in The Netherlands by Engzell, Frey, and Verhagen 6 . The authors analyzed changes in performance associated with school closures, using a uniquely rich dataset with more than 350,000 students in primary school. The data included biannual test scores collected at the middle and the end of each school year from 2017 and 2020. Critically, in 2020, the mid-year tests took place right before the first school closures in The Netherlands, providing a benchmark that authors could use to estimate learning losses. The authors identified an overall decrease in academic performance equivalent to 0.08 standard deviation units. Moreover, the effects on learning outcomes were not uniform, as students from less-educated households experienced losses 60% more pronounced than the general population.

These findings are critical since they provide evidence of the potential effects of the pandemic in a “best-case” scenario. More than 90% of students in The Netherlands had access to a computer at home, and more than 95% had access to the internet and a quiet place to study 7 . But even in this context of high levels of access to digital resources, equitable funding for elementary schools, and average-to-high performance prior to the pandemic, school closures have had tangible effects on learning outcomes, especially for children with disadvantaged backgrounds.

Similar studies comparing students’ performance before and after COVID have been conducted in other countries 8 , 9 . Most of them have found evidence of learning losses and slower rates of growth in academic abilities during the 2020–2021 school year 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , while others did not find any negative effects 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 .

Moreover, there is strong evidence suggesting that pre-existing inequalities in education have become more pronounced. Even before the pandemic, achievement gaps across socio-economic status (SES) were evident since kindergarten and persisted across education years 27 , 28 . During the pandemic, students from disadvantaged backgrounds suffered longer school closures 29 and had less access to computers and internet for schoolwork 7 , 30 , 31 , 32 . In addition, families facing financial struggles were in less favorable positions to dedicate resources and time to school activities at home 33 . As a result of these and other limitations, learning losses have been more severe for students from racial minorities 15 , 19 , 34 , with less educated parents 6 , 17 or those coming from low-income households 13 , 14 , 16 , 19 , 34 , 35 .

Recent attempts to synthesize the literature about learning losses 8 estimate that students have lost the equivalent of 35% of an academic year’s worth of learning. However, further data is necessary to assess the real extent to which the pandemic has impacted learning. On one hand, the data about changes in students’ performance is still very scarce, due to the limitations that remote learning imposed on school abilities to continue standardized assessments. Moreover, students from disadvantaged groups are more likely to be underrepresented 11 , 34 , 36 , both within countries and on a global scale 8 . Therefore, further evidence is needed to assess the real extent of the effects of the pandemic across different socio-economic conditions.

Teachers are a critical source of information that has not been considered enough. Teachers were at the front line of the education efforts during the pandemic and observed the impact on student learning and academic performance firsthand. While not free of biases, they are possibly the best-informed source of information about students’ abilities to benefit from these efforts, using their own previous experience as a comparison point. Critically, teachers’ observations are available across all school contexts and socio-economic strata. Therefore, they can provide insights into the effects of the pandemic that are representative of a wider variety of contexts than the ones included in a recent analysis of individual differences. Elementary school teachers more specifically, establish a unique relationship with their students, as they instruct them in multiple subjects, compared to higher education where students’ curriculum and interests are more heterogeneous, and students are often taught different subjects by different teachers. As a result, in the current context of data scarcity, elementary school teachers may be better prepared to aggregate individual student information into group-level estimates than can be accessed through survey methods.

Moreover, understanding teacher’s experiences throughout the pandemic is of critical importance for the future of education. Multiple studies have indicated that teachers have experienced higher levels of dissatisfaction and a lower sense of success during the pandemic 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , resulting in increased levels of attrition rates worldwide 42 .

The present study presents the results of a survey distributed to teachers in Canada and the US, right at the end of the 2020–2021 school year. Our survey obtained participants’ assessments about three overarching issues: (1) How did teachers experience the transition to emergency remote learning? (2) How were equitable opportunities to access education impacted by school closures? and (3) Have students experienced learning losses or gains during the pandemic? We also collected additional data about variables regarding the socio-economic context of students to explore the generalizability of our data to different school and classroom contexts.

Teachers’ experience transitioning from in-person to remote classes

Table 1 summarizes some of the variables that assessed teachers’ experience transitioning to remote learning. We expected that teachers’ previous experiences with online teaching and technology may have influenced how well they adapted to these changes. Overall, the observed distributions show that we recruited participants with different levels of previous preparation and training in both countries.

Notably, the proportion of teachers with no previous experience teaching online goes from 40% for high-SES students, to more than 75% for low SES students. This association was statistically significant \(({\tau }_{c}=0.22{;p}\, < \,0.001)\) . Although weak, we also found significant interactions between student’s income level and the amount of training teachers received ( X 2 = 23.44; p = 0.024, df = 12, Cramer ′ sV = 0.09). We also observed higher levels of proficiency using digital technologies for educational purposes \(({\tau }_{c}=0.08{;p}=0.007)\) for teacher of higher-income students. As we expected, switching to remote education was increasingly challenging for teachers with less experience teaching online \(({\tau }_{c}=-0.18{;p}\, < \,0.001)\) , and those with poor digital skills \(({\tau }_{c}=-0.11{;p}\, < \,0.001)\) .

Equitable opportunities to access education

Multiple items throughout the survey assessed to what extent learning opportunities were offered to students and their ability to benefit from them (Table 2 ). More than 96% of participants agreed that most to all students in their classroom had access to the resources needed for online classes. The distribution of responses was slightly different between countries ( X 2 = 17.82, p < 0.001, df = 3, Cramer ′ sV = 0.15). But overall, even for teachers that had low-income students, reporting that few or none of their students had access to technology was rare.

Despite having the means to access online education, more than 65% of participants indicated that attendance to class decreased during the 2020–2021 school year. Overall, there was no significant difference in teachers’ reports of attendance across countries ( X 2 = 2.97, p < 0.227, df = 2, Cramer ′ sV = 0.07). However, there was a difference in the association between attendance levels and students’ income across countries. For teachers in the US, lower levels of attendance were reported more frequently when students came from low-income households \(({\tau }_{c}=-0.19{;p}\, < \,0.001)\) . For Canadian teachers, this association was not present \(({\tau }_{c}=-0.03{;p}\, < \,0.517)\) .

Knowing the limitations of this survey in terms of providing individual data about attendance, we included one additional question to explore approximately what proportion of students were missing from the classroom. We asked respondents to break down their students into three different groups: students who attended regularly, students who attended irregularly and students who were completely absent from class throughout the whole year. According to teachers’ estimations, an average of 69.98% of students were present regularly in class, 21.24% came to class only irregularly and another 8.78% were completely absent during the whole school year. The proportion of students completely absent was consistently low for all SES levels \((F(4,611)=0.46,{p}=0.764,{\eta }^{2}=0.01)\) . In contrast, the number of students attending regularly increased linearly with SES levels \((F(4,611)=2.41,{p}=0.048,{\eta }^{2}=0.02{;linear\; trend}:t=2.12,{SE}=3.16,{p}=0.034)\) . Since these proportions are complementary, the proportion of students attending irregularly also decreased across SES levels \((F(4,611)=3.34,{p}=0.010,{\eta }^{2}=0.02{;linear\; trend}:t=-2.52,{SE}=2.28,{p}=0.012)\) .

During class, most participants indicated that they covered less content during online lessons than they do in a regular school year. Moreover, around 28% of participants considered that adult assistance was needed for students to complete schoolwork. Whether the support from a parent or caregiver was imperative or not, we also asked participants to estimate, approximately, what proportion of their students received help at home. More than 70% of participants perceived that most to all students in their class had the support of an adult to some degree. But more importantly, perceived levels of support were higher for teachers of students coming from higher-income households \(({\tau }_{c}=-0.25{;p}\, < \,0.001)\) .

Changes in academic performance during the pandemic

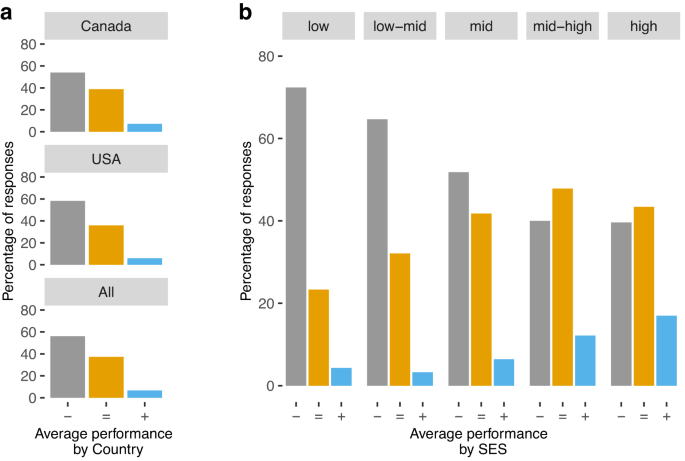

Another important goal of our survey was to get teachers’ input on how different aspects of academic achievement may have been affected because of the interruption of in-person classes (Table 3 ). More than 50% of teachers indicated that children in their class performed worse than in previous years (Fig. 1a ). Moreover, teachers who reported having students from lower socio-economic status were more likely to report that performance was below the expectations for the grade (Fig. 1b ; \({\tau }_{c}=-0.25{;p}\, < \,0.001\) ). There were no differences across countries in these estimations of students’ average performance ( X 2 = 2.97, p < 0.227, df = 2, Cramer ′ sV = 0.07).

Teachers’ perceptions of the overall performance of students, compared to a regular school year ( a ) by country and ( b ) by classroom SES. Legend: - On average, students have performed below the expectations for their grade = On average, students have performed according to the expectations for their grade + On average, students have performed above the expectations for their grade.

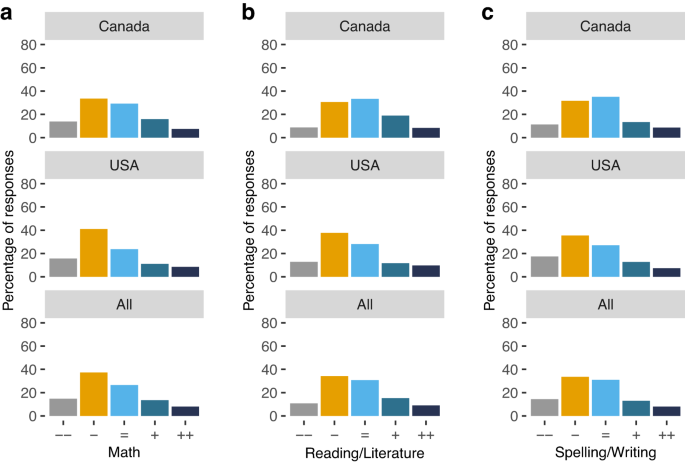

Previous reports have suggested that learning losses during the pandemic have not been equally severe across different learning domains 11 . Motivated by those results, we asked participants to rate students’ performance in Math, Reading/Literature, and Spelling/Writing, separately. The distribution of responses for the three domains was slightly skewed, as most teachers reported learning losses to some degree for the three areas. We wanted to know if teachers’ perceptions of academic loss for specific domains varied depending on the subject they teach. Unfortunately, around 60% of our participants did not report that information. Moreover, out of the 40% who reported the subjects they were teaching, more than half of them taught multiple subjects that covered the three topics of interest. Nonetheless, we ran an exploratory analysis including just that 40% and we did not observe significant effects. (i.e. participants who teach math-related areas do not report better or worse learning losses in math when compared to other participants).

To complement these overall ratings, we requested more detailed information about the distribution of students in their classrooms, according to their performance level. Participants were asked to classify their students into three categories: students who performed below the expectations for their grade, students who performed according to the expectations for their grade, and students who performed above the expectations for their grade. Even though our data cannot inform about individual differences in performance, with this question we expected to obtain an estimate of the proportion of students who experienced the learning losses reported in the previous questions.

Comparing the data across the three domains did not yield significant differences in the severity of learning losses that teachers report for Math, Reading, or Spelling (Fig. 2 ). However, we did find differences across countries in the proportions of low, average, or high-performance students that teachers reported across all domains. Canadian teachers reported lower percentages than their US counterparts of students performing below standards during the 2020–21 school year \((F(1,904)=7.23,{p}=0.007,{\eta }^{2}=0.01)\) . They also reported higher proportions of students performing above standards for their grades despite the pandemic \((F(1,905)=37.54,{p}\, < \,0.001,{\eta }^{2}=0.03)\) . In summary, even though teachers of both countries reported an overall decrease in students’ performance, teachers from the US report having a higher percentage of students experiencing these losses.

Average performance of students compared to a regular school year in ( a ) Math, ( b ) Reading/Literature, and ( c ) Spelling/Writing. Legend: -- Much worse- Somewhat worse = About the same + Somewhat better + + Much better.

Participants were also asked to estimate whether the gap between the students performing at the higher level, and those performing at the lowest level had increased, decreased, or stayed the same, compared to a typical school year. This question was designed to elicit teachers’ views of individual differences between students in their classrooms. About 58% of teachers indicated that differences between students had widened during the 2020–2021 school year, in contrast to around 32% who didn’t perceive any changes and another 10% who indicated that this gap decreased. Finally, we included one general question in the survey to ask teachers if they believed that the pandemic would have long lasting effects on students and, if so, whether these effects would have a positive or negative outcome. A large proportion of the participants expressed that the changes occurring during the pandemic would most likely have a negative impact on students’ learning in the long run.

We distributed a survey to primary school teachers in the US and Canada at the end of the 2020–2021 school year. Our survey was able to reach teachers from different levels of SES, who were affected by school closure at varying degrees. Their responses provided relevant insights into how education took place during the COVID-19 health crisis, especially during the 2020–2021 school year, the first to fully occur within the pandemic.

Results from our survey suggest that a large proportion of students in both countries had access to the digital resources required to access these online alternatives (such as computers, internet, etc.). This was especially true for students from advantaged homes, but even in the lower SES levels, more than 90% of students had access to digital resources. This is not surprising, considering recent statistics showing that around 93% and 88% of students in Canada and the US, respectively, have access to a computer at home and more than 95% have access to the internet in both countries 7 , 32 .

However, the availability of digital resources is necessary but not sufficient to guarantee that students have access to educational opportunities. For example, our data indicates that the amount of instruction time decreased substantially, compared to a regular school year. Instruction time requirements for primary school in both Canada 43 and the US 44 vary across states, but the average is close to 30 h per week. The average number of hours of remote instruction reported by our participants fell below the 20 h, which represents less than two thirds of these typical requirements. Consistently, most participants reported not being able to deliver all the content they typically taught during a regular school year. In addition, most participants indicated that attendance to class was lower than in a traditional year. Was this trend due to just a few, or to many students consistently missing class? On average, our respondents report that approximately 3 in every 10 students in their class were attending inconsistently or completely absent. Although small, the reported proportions of students who were completely absent from class are of critical importance, since they represent students who were not able to benefit from education opportunities at all during the last school year.

Overall, nearly 56% of our participants agreed that students performed below the expectations for their grades during the 2020–2021 school year. These reports are converging with previous studies using standardized tests to compare students’ academic achievement before and during the pandemic (Engzell et al., 2020; Kuhfeld et al., 2020). Unlike previous studies, teachers’ rates of academic performance obtained during our survey do not suggest that the drop in math performance was more pronounced than in other domains (i.e., reading). It is possible that differences between learning losses experienced across domains exist in our student population, as suggested by studies analyzing individual data on standardized tests. However, those differences may not be large enough to be captured by the limited response options presented in our survey. It is also possible that presenting this question in a grid format may have increased the probability of straight-lining, or the tendency in which participants select the same answer choice to all items on the question.

More importantly, teachers’ rates of academic performance varied drastically according to the income-level of their students, and more than half of our participants agreed that differences between low and high performing students became more pronounced during the 2020–2021 school year. This learning gap between low and high performing students is fundamentally different from the overall performance trend. Assuming that teachers’ ratings are an accurate depiction of how actual performance was impacted by the school closures, the questions about overall performance should reflect perceived changes on the mean of the distribution, whereas the questions about the learning gap should reflect perceived changes on the difference between the lower and the upper tail of the distribution within their classrooms.

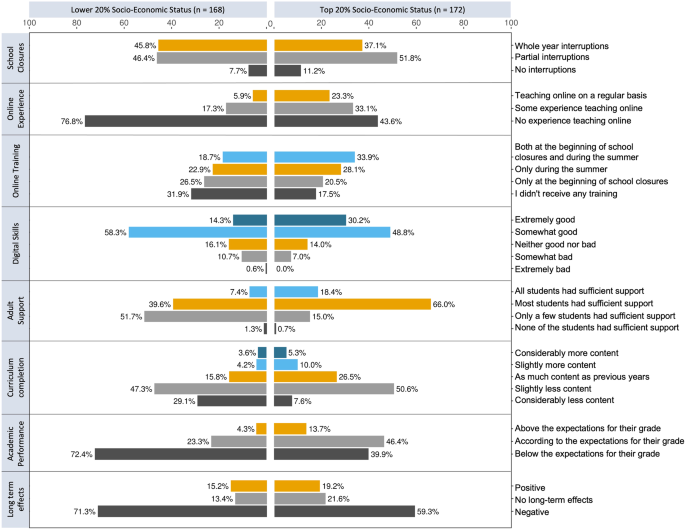

Like previous studies in the literature, our findings suggest that the pandemic has emphasized individual differences between students of different income levels, that are otherwise attenuated during in-person instruction. Figure 3 highlights the most noticeable differences between the lower and the top 20% of the SES distribution. The consistent pattern of interaction between teachers’ reports of the effects of the pandemic and their students’ socio-economic background suggests that students from low- and high-income households may have experienced school closures in very different ways.

We created two groups to represent the extremes of the SES distribution. To make the groups comparable in terms of size, the lower SES group included participants who reported that their students come from predominantly Low-Income households ( n = 168), whereas the higher SES group included participants whose students predominantly come from High-Income households ( n = 53), or a mix of Middle and High-Income ( n = 119). Since our perceived SES measure is on a discrete scale, selecting exactly the top and bottom 20% is not possible. Instead, the lower and higher income groups represent 18.44% and 18.88% of the distribution.

First, our data suggest that teachers from classrooms with higher income levels may have been more prepared for the transition to remote alternatives, as they had more relevant experience with online instruction before the pandemic and they had better self-ratings of digital skills than teachers from lower SES classrooms. For example, 7 out of every 10 teachers of students in the lower 20% of the SES were teaching online for the first time during the pandemic, versus only 4 out of every 10 in the top 20% SES.

During the school closures, teachers from higher SES classrooms were also less likely to report a drop in overall attendance levels to online lessons, compared to a regular school year, and had higher proportions of students who consistently attended class. Moreover, they observed students receiving support from adults at home more frequently. This was one of the most striking contrasts observed in our data, which became more evident when comparing the two extremes of the distribution. Taken together, these results suggest that students in higher income levels may have been in a better position to benefit from the remote alternatives offered during the pandemic. Consistent with this prediction, teachers from higher income classrooms were also less likely to report learning losses during the pandemic.

These results have critical implications for our understanding of the long-term effect of the pandemic. Household income was already an important predictor of future academic achievement before the pandemic. With the closure of schools as a measure to contain the spread of the COVID-19 virus, children from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds who were already in a vulnerable position may find themselves falling further behind their peers. As a result, they may be more likely to experience dropout in the future and less likely to pursue higher levels of education, which may reinforce the already existing income inequalities into future generations.

There are limitations to our results due to the observational nature of the data. It is possible that some of the associations observed are the results of biases in teachers’ perceptions. In addition, it is important to bear in mind that teacher reports offer information that occurs at the classroom level and therefore cannot account for effects at the individual level.

Despite these limitations, teachers can provide insights into the effects that the pandemic has had on students that is unique and highly valuable. Teachers have been active observers of students’ performance before, during, and after the pandemic. They receive a constant stream of data from students and therefore may perceive trends that standardized tests taken at a single time point may not capture.

In addition, teachers can provide information that is representative of a wide range of socio-economic and classroom contexts, something that has been a limitation of previous analyses of individual data. Our survey has its own limitations when describing the effects of SES on learning during the pandemic. For instance, we cannot guarantee that the SES levels reported by teachers in the US will correspond perfectly with the same levels in Canada. In other words, what teachers consider low SES in one country may be considered middle SES in the other. But even if the levels do not overlap perfectly, what seems to be consistent across our data is that students in lower levels struggled more during the pandemic and that trend remains when analyses are conducted on each country separately.

Critically, the relevance of teacher surveys is not only limited to their role as informants of students’ achievement. Teachers have a critical role in carrying forward education efforts and understanding how they experienced the recent crisis is by itself a critical question that current research should address. The stress associated with abrupt changes in the work environment, combined with the high demands and responsibility levels puts teachers at risk of experiencing work-related burnout. In fact, previous studies have found that, during 2020, teachers were more likely to consider leaving the classroom before retirement age 39 , 45 , 46 , 47 , and at least 23% considered retiring specifically due to the pandemic 48 , which has aggravated the already existing global crisis of teacher shortages 42 . In our survey, as expected, the frequency of teachers considering leaving their profession was higher for those with more years of experience. However, even in the group of less experienced teachers, around 1 in every 4 considered retiring during the pandemic. Teachers are expected to continue to have a critical role as the pandemic continues to unfold and in future efforts to mitigate the learning losses experienced by students during this period. It is evident from these results that understanding teachers’ experiences and providing them with the necessary resources and support will be critical for the success of these efforts.

In summary, our results provide an insight into how teachers from these countries experienced remote education, and their observations about consequences for students’ academic achievement, measured right at the end of the first school year to fully occur amidst the pandemic. Our sample was diverse in terms of the geographical distribution of responses and the socio-economic background of the students. Nevertheless, our results may be specific to the higher-level socio-economic characteristics of these countries and may not be generalizable to different contexts. Our results suggest that even in the presence of widespread access to digital learning tools, consistent attendance to class and complete delivery of the curriculum could not be guaranteed. Most teachers reported observing a decline in students’ academic performance, and a growth in the gaps between low and high performing students. More importantly, our data suggest that the effects of the pandemic were not equally distributed. Students from lower SES levels had teachers who were less prepared for the transition to online activities and received less support from adults during homeschooling. Consistently, teachers from lower SES classrooms also reported drops in performance more frequently than those from the higher SES levels.

Even though the group estimations that teachers provide at the classroom level are not enough to suggest causal relationships between the variables we studied and individual differences in academic achievement, teachers contribute valuable information, based on their constant interaction with students. Their observations provide a unique perspective on the effects of the pandemic that is relevant to inform policy decisions and future research.

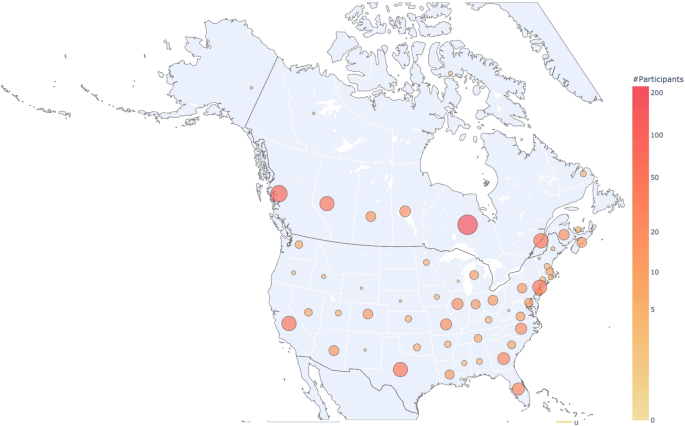

Participants

Teachers from public elementary schools were recruited through the Qualtrics Online Sample panel. We aimed at a sample size of 900 participants, 450 from Canada and 450 from the US. Our sample size was constrained by the availability of participants from the Qualtrics panel that fit into our inclusion criteria. We required participants to be elementary school teachers (grades 1 to 6), fluent in English, living in Canada or the US, who were actively teaching during the 2020–2021 school year. We surveyed 918 participants between June 16th and June 28th, 2021. Seven participants were removed for having a large number of missing responses. The final sample included 911 participants, 453 from Canada and 458 from the US (Fig. 4 ). The complete dataset can be accessed here: https://osf.io/3dsef .

Distribution of responses collected across Canada and the US 49 The circle size represents the amount of participants recruited, transformed to log scale.

Our sample was diverse in terms of the professional background of participants and the socioeconomic characteristics of their students (see Table 4 ). We did not consider participants’ socioeconomic status (SES) when determining inclusion. In fact, we were not able to select participants across specific SES levels since the Qualtrics Online Sample of teachers was already limited. Rather, we recruited all potential participants and subsequently described the income level of the students they teach, as reported by the participants themselves.

There were small differences between participants of both countries. For example, teachers from the US were on average more experienced than their Canadian counterparts ( X Can = 10.05 years, X USA = 11.82 years; t (822.63) = −2.14, p = 0.033, d = 0.14) and reported having students from lower-income households to a greater extent ( X 2 = 71.44, p = 0.000, df = 4, Cramer ′ sV = 0.20).

More than 90% of teachers in our sample experienced school closures during the pandemic, ranging from a few days to the whole year (Table 5 ). Partial closures were, on average, larger in Canada compared to the US ( t (409.40) = 3.32, p = 0.001, d = 0.33). During remote instruction, participants reported spending around 18.87 h of class time per week. Furthermore, most participants received classwork from students on a weekly or daily basis and provided feedback with similar frequency. These survey items offered an estimate of the amount of information that participants received from students, which will serve as a basis for their judgments about academic performance.

Since most of the observed discrepancies between countries corresponded to small effect sizes, we considered both groups of participants to be comparable. Therefore, we report here the results corresponding to the whole sample.

The study was approved by the Non-medical Research Ethics Board of the University of Western Ontario. We administered the survey through the Qualtrics online platform. All the participants on the Qualtrics panel who potentially met our inclusion criteria received an email with a link to the survey and the estimated time commitment. Participants who accessed the link were presented with the letter of information (LOI) before starting the survey. Since the survey was administered online, participants could not provide written consent. Instead, they indicated agreement to participate by ticking a checkbox at the end of the LOI. The survey was presented only to those participants who provided this type of consent.

We asked participants to complete the survey in a single session, which should have taken approximately 10 min. To minimize the risk of missing data, we required responses for most survey items. However, all the questions with response requirements included an ‘I prefer not to answer’ option that participants could use if they didn’t feel comfortable disclosing the required information. The complete survey is available here: https://osf.io/bx63k/ .

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/3dsef .

UNESCO. Education: From disruption to recovery. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse#schoolclosures (2020).

UNICEF. COVID-19 and School Closures: One Year of Education Disruption . (2021).

United Nations. Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond. Policy Brief (2020).

World Bank Group. The COVID-19 pandemic: shocks to education and policy responses. Education vol. 29 (2020).

Bansak, C. & Starr, M. Covid-19 shocks to education supply: how 200,000 U.S. households dealt with the sudden shift to distance learning. Rev. Econ. House. 19 , 63–90 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

Engzell, P., Frey, A. & Verhagen, M. D. Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118 , e2022376118 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

OECD. Learning remotely when schools close: How well are students and schools prepared? Insights from PISA . (2020).

Betthäuser, B. A., Bach-Mortensen, A. M. & Engzell, P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on learning . (2022).

Moscoviz, L. & Evans, D. K. Learning loss and student dropouts during the COVID-19 Pandemic: a review of the evidence two years after schools shut down abstract. Center for Global Development www.cgdev.org (2022).

Tomasik, M. J., Helbling, L. A. & Moser, U. Educational gains of in-person vs. distance learning in primary and secondary schools: a natural experiment during the COVID-19 pandemic school closures in Switzerland. Int. J. Psychol. 56 , 566–576 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Kuhfeld, M., Tarasawa, B., Johnson, A., Ruzek, E. & Lewis, K. Learning during COVID-19: initial findings on students’ reading and math achievement and growth. Collaborative for student growth (2020).

Domingue, B. W., Hough, H. J., Lang, D., Yeatman, J. & Christian, M. S. Changing patterns of growth in oral reading fluency during the COVID-19 pandemic . (2021).

Maldonado, J. E. & de Witte, K. The effect of school closures on standardised student test outcomes. Br. Educ. Res. J. (2021) https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3754 .

Domingue, B. W. et al. The effect of COVID on oral reading fluency during the 2020–2021 academic year. AERA Open 8 , 233285842211202 (2022).

Pier, L., Hough, H. J., Christian, M. & Bookman, N. COVID-19 and the Educational Equity Crisis | Policy Analysis for California Education . https://edpolicyinca.org/newsroom/covid-19-and-educational-equity-crisis (2021).

Dorn, E., Hancock, B., Sarakatsannis, J. & Viruleg, E. COVID-19 and learning loss-disparities grow and students need help . (2020).

Contini, D., di Tommaso, M. L., Muratori, C., Piazzalunga, D. & Schiavon, L. The COVID-19 pandemic and school closure: learning loss in mathematics in primary education . (2021).

Schult, J., Mahler, N., Fauth, B. & Lindner, M. A. School Effectiveness and School Improvement Did students learn less during the COVID-19 pandemic? Reading and mathematics competencies before and after the first pandemic wave. (2022) https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2022.2061014 .

Renaissance Learning. How kids are performing tracking the impact of COVID-19 on reading and mathematics achievement . www.renaissance.com (2020).

Ardington, C., Wills, G. & Kotze, J. COVID-19 learning losses: early grade reading in South Africa. Int J. Educ. Dev. 86 , 102480 (2021).

Hevia, F. J., Vergara-Lope, S., Velásquez-Durán, A. & Calderón, D. Estimation of the fundamental learning loss and learning poverty related to COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. Int J. Educ. Dev. 88 , 102515 (2022).

Gambi, L. & De Witte, K. The resiliency of school outcomes after the COVID-19 pandemic. Standardised test scores and inequality one year after long term school closures. FEB Research Report Department of Economics (2021).

Spitzer, M. W. H. & Musslick, S. Academic performance of K-12 students in an online-learning environment for mathematics increased during the shutdown of schools in wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One 16 , e0255629 (2021).

Gore, J., Fray, L., Miller, A., Harris, J. & Taggart, W. The impact of COVID-19 on student learning in New South Wales primary schools: an empirical study. Aust. Educ. Res 48 , 605–637 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hallin, A. E., Danielsson, H., Nordström, T. & Fälth, L. No learning loss in Sweden during the pandemic: evidence from primary school reading assessments. Int J. Educ. Res 114 , 102011 (2022).

UNESCO Institute of Statistics. COVID-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa: monitoring impacts on learning outcomes . http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en (2022).

Kuhfeld, M., Condron, D. J. & Downey, D. B. When does inequality grow? A seasonal analysis of racial/ethnic disparities in learning from kindergarten through eighth grade. Educ. Res. 50 , 225–238 (2021).

García, E. & Weiss, E. Education inequalities at the school starting gate. Gaps, trends, and strategies to address them . (2017).

Parolin, Z. & Lee, E. K. Large socio-economic, geographic and demographic disparities exist in exposure to school closures. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021 5:4 5 , 522–528 (2021).

OECD. Students access to a computer at home. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/data-insights/student-access-to-a-computer-at-home (2020).

Frenette, M., Frank, K. & Deng, Z. School Closures and the Online Preparedness of Children during the COVID-19 Pandemic . www.statcan.gc.ca (2020).

Irwin, V. et al. Report on the Condition of Education. 2021 . (2021).

Pensiero, N., Kelly, T. & Bokhove, C. Learning inequalities during the Covid-19 pandemic: how families cope with home-schooling. University of Southampton research report . (2020) https://doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/P0025 .

Lewis, K. & Kuhfeld, M. Learning during COVID-19 : An update on student achievement and growth at the start of the 2021–22 school year . (2021).

Haelermans, C. et al. A full year COVID-19 crisis with interrupted learning and two school closures: the effects on learning growth and inequality in primary education. ROA Research Memorandum (2021) https://doi.org/10.26481/UMAROR.2021009 .

Lewis, K., Kuhfeld, M., Ruzek, E. & McEachin, A. Learning during COVID-19: Reading and Math achievement in the 2020–21 school year . https://content.acsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Learning-During-COVID-19-Reading-and-Math-NWEA-Brief.pdf (2021).

Silva, R. R. V. et al. COVID-19 pandemic: dissatisfaction with work among teachers in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Cien Saude Colet. 26 , 6117–6128 (2021).

Alves, R., Lopes, T. & Precioso, J. Teachers’ well-being in times of Covid-19 pandemic: factors that explain professional well-being. IJERI: Int. J. Educ. Res. Innov. 203–217 (2020) https://doi.org/10.46661/ijeri.5120 .

Gillani, A. et al. Teachers’ dissatisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic: factors contributing to a desire to leave the profession. (2022) https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.940718 .

Aperribai, L., Cortabarria, L., Aguirre, T., Verche, E. & Borges, Á. Teacher’s physical activity and mental health during lockdown due to the COVID-2019 pandemic. Front Psychol. 11 , 2673 (2020).

Kraft, M. A., Simon, N. S. & Lyon, M. A. Sustaining a sense of success: the protective role of teacher working conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Res Educ. Eff. 14 , 727–769 (2021).

Google Scholar

UNESCO. Transforming education from within. (2022).

Statistics Canada. Education Indicators in Canada: An International Perspective 2017 . https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/81-604-x/2017001/ch/chd-eng.htm (2017).

National Center for Education Statistics. State Education Practices (SEP) . (2020).

Bacher-Hicks, A., Chi, O. L. & Orellana, A. Two years later: how COVID-19 has shaped the teacher workforce. Educational Researcher (2023) https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X231153659 .

Hoang, A.-D. Pandemic and teacher retention: empirical evidence from expat teachers in Southeast Asia during COVID-19. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 40 , 1141–1166 (2020).

Gunn, T. M., McRae, P. A. & Edge-Partington, M. Factors that influence beginning teacher retention during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from one Canadian province. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 4 , 100233 (2023).

Zamarro, G. & Camp, A. Understanding how COVID-19 has Changed Teachers ’ Chances of Remaining in the Classroom Research Brief Understanding how COVID- 19 has Changed Teachers ’ Chances of Remaining in the Classroom . (2021).

Plotly Technologies Inc. Collaborative data science. Montréal, QC . https://plot.ly . (2015)

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the educators who offered their valuable time to respond to our survey. We would also like to thank Bea Goffin for assistance with research ethics and project management. This project was supported by a Catalyst Grant from the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR, Grant Reference CF-0213) to CLO and DA. Danial Ansari is supported by the Jacobs Foundation through the CERES Network.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada

Aymee Alvarez-Rivero & Daniel Ansari

Department of Psychological Science, University of California -Irvine, Irvine, CA, USA

Candice Odgers

Social Science Research Institute, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Study conception and design by all authors. Initial survey draft by A.A.R, but all authors reviewed and provided feedback that was incorporated to the final version. Data analysis and initial draft of the manuscript by A.A.R but all authors contributed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Aymee Alvarez-Rivero .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Reporting summary, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Alvarez-Rivero, A., Odgers, C. & Ansari, D. Elementary school teachers’ perspectives about learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. npj Sci. Learn. 8 , 40 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-023-00191-w

Download citation

Received : 01 December 2022

Accepted : 04 September 2023

Published : 18 September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-023-00191-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Our Mission

The 10 Most Significant Education Studies of 2021

From reframing our notion of “good” schools to mining the magic of expert teachers, here’s a curated list of must-read research from 2021.

It was a year of unprecedented hardship for teachers and school leaders. We pored through hundreds of studies to see if we could follow the trail of exactly what happened: The research revealed a complex portrait of a grueling year during which persistent issues of burnout and mental and physical health impacted millions of educators. Meanwhile, many of the old debates continued: Does paper beat digital? Is project-based learning as effective as direct instruction? How do you define what a “good” school is?

Other studies grabbed our attention, and in a few cases, made headlines. Researchers from the University of Chicago and Columbia University turned artificial intelligence loose on some 1,130 award-winning children’s books in search of invisible patterns of bias. (Spoiler alert: They found some.) Another study revealed why many parents are reluctant to support social and emotional learning in schools—and provided hints about how educators can flip the script.

1. What Parents Fear About SEL (and How to Change Their Minds)

When researchers at the Fordham Institute asked parents to rank phrases associated with social and emotional learning , nothing seemed to add up. The term “social-emotional learning” was very unpopular; parents wanted to steer their kids clear of it. But when the researchers added a simple clause, forming a new phrase—”social-emotional & academic learning”—the program shot all the way up to No. 2 in the rankings.

What gives?

Parents were picking up subtle cues in the list of SEL-related terms that irked or worried them, the researchers suggest. Phrases like “soft skills” and “growth mindset” felt “nebulous” and devoid of academic content. For some, the language felt suspiciously like “code for liberal indoctrination.”

But the study suggests that parents might need the simplest of reassurances to break through the political noise. Removing the jargon, focusing on productive phrases like “life skills,” and relentlessly connecting SEL to academic progress puts parents at ease—and seems to save social and emotional learning in the process.

2. The Secret Management Techniques of Expert Teachers

In the hands of experienced teachers, classroom management can seem almost invisible: Subtle techniques are quietly at work behind the scenes, with students falling into orderly routines and engaging in rigorous academic tasks almost as if by magic.

That’s no accident, according to new research . While outbursts are inevitable in school settings, expert teachers seed their classrooms with proactive, relationship-building strategies that often prevent misbehavior before it erupts. They also approach discipline more holistically than their less-experienced counterparts, consistently reframing misbehavior in the broader context of how lessons can be more engaging, or how clearly they communicate expectations.

Focusing on the underlying dynamics of classroom behavior—and not on surface-level disruptions—means that expert teachers often look the other way at all the right times, too. Rather than rise to the bait of a minor breach in etiquette, a common mistake of new teachers, they tend to play the long game, asking questions about the origins of misbehavior, deftly navigating the terrain between discipline and student autonomy, and opting to confront misconduct privately when possible.

3. The Surprising Power of Pretesting

Asking students to take a practice test before they’ve even encountered the material may seem like a waste of time—after all, they’d just be guessing.

But new research concludes that the approach, called pretesting, is actually more effective than other typical study strategies. Surprisingly, pretesting even beat out taking practice tests after learning the material, a proven strategy endorsed by cognitive scientists and educators alike. In the study, students who took a practice test before learning the material outperformed their peers who studied more traditionally by 49 percent on a follow-up test, while outperforming students who took practice tests after studying the material by 27 percent.

The researchers hypothesize that the “generation of errors” was a key to the strategy’s success, spurring student curiosity and priming them to “search for the correct answers” when they finally explored the new material—and adding grist to a 2018 study that found that making educated guesses helped students connect background knowledge to new material.

Learning is more durable when students do the hard work of correcting misconceptions, the research suggests, reminding us yet again that being wrong is an important milestone on the road to being right.

4. Confronting an Old Myth About Immigrant Students

Immigrant students are sometimes portrayed as a costly expense to the education system, but new research is systematically dismantling that myth.

In a 2021 study , researchers analyzed over 1.3 million academic and birth records for students in Florida communities, and concluded that the presence of immigrant students actually has “a positive effect on the academic achievement of U.S.-born students,” raising test scores as the size of the immigrant school population increases. The benefits were especially powerful for low-income students.

While immigrants initially “face challenges in assimilation that may require additional school resources,” the researchers concluded, hard work and resilience may allow them to excel and thus “positively affect exposed U.S.-born students’ attitudes and behavior.” But according to teacher Larry Ferlazzo, the improvements might stem from the fact that having English language learners in classes improves pedagogy , pushing teachers to consider “issues like prior knowledge, scaffolding, and maximizing accessibility.”

5. A Fuller Picture of What a ‘Good’ School Is

It’s time to rethink our definition of what a “good school” is, researchers assert in a study published in late 2020. That’s because typical measures of school quality like test scores often provide an incomplete and misleading picture, the researchers found.

The study looked at over 150,000 ninth-grade students who attended Chicago public schools and concluded that emphasizing the social and emotional dimensions of learning—relationship-building, a sense of belonging, and resilience, for example—improves high school graduation and college matriculation rates for both high- and low-income students, beating out schools that focus primarily on improving test scores.

“Schools that promote socio-emotional development actually have a really big positive impact on kids,” said lead researcher C. Kirabo Jackson in an interview with Edutopia . “And these impacts are particularly large for vulnerable student populations who don’t tend to do very well in the education system.”

The findings reinforce the importance of a holistic approach to measuring student progress, and are a reminder that schools—and teachers—can influence students in ways that are difficult to measure, and may only materialize well into the future.

6. Teaching Is Learning

One of the best ways to learn a concept is to teach it to someone else. But do you actually have to step into the shoes of a teacher, or does the mere expectation of teaching do the trick?

In a 2021 study , researchers split students into two groups and gave them each a science passage about the Doppler effect—a phenomenon associated with sound and light waves that explains the gradual change in tone and pitch as a car races off into the distance, for example. One group studied the text as preparation for a test; the other was told that they’d be teaching the material to another student.

The researchers never carried out the second half of the activity—students read the passages but never taught the lesson. All of the participants were then tested on their factual recall of the Doppler effect, and their ability to draw deeper conclusions from the reading.

The upshot? Students who prepared to teach outperformed their counterparts in both duration and depth of learning, scoring 9 percent higher on factual recall a week after the lessons concluded, and 24 percent higher on their ability to make inferences. The research suggests that asking students to prepare to teach something—or encouraging them to think “could I teach this to someone else?”—can significantly alter their learning trajectories.

7. A Disturbing Strain of Bias in Kids’ Books

Some of the most popular and well-regarded children’s books—Caldecott and Newbery honorees among them—persistently depict Black, Asian, and Hispanic characters with lighter skin, according to new research .

Using artificial intelligence, researchers combed through 1,130 children’s books written in the last century, comparing two sets of diverse children’s books—one a collection of popular books that garnered major literary awards, the other favored by identity-based awards. The software analyzed data on skin tone, race, age, and gender.

Among the findings: While more characters with darker skin color begin to appear over time, the most popular books—those most frequently checked out of libraries and lining classroom bookshelves—continue to depict people of color in lighter skin tones. More insidiously, when adult characters are “moral or upstanding,” their skin color tends to appear lighter, the study’s lead author, Anjali Aduki, told The 74 , with some books converting “Martin Luther King Jr.’s chocolate complexion to a light brown or beige.” Female characters, meanwhile, are often seen but not heard.

Cultural representations are a reflection of our values, the researchers conclude: “Inequality in representation, therefore, constitutes an explicit statement of inequality of value.”

8. The Never-Ending ‘Paper Versus Digital’ War

The argument goes like this: Digital screens turn reading into a cold and impersonal task; they’re good for information foraging, and not much more. “Real” books, meanwhile, have a heft and “tactility” that make them intimate, enchanting—and irreplaceable.

But researchers have often found weak or equivocal evidence for the superiority of reading on paper. While a recent study concluded that paper books yielded better comprehension than e-books when many of the digital tools had been removed, the effect sizes were small. A 2021 meta-analysis further muddies the water: When digital and paper books are “mostly similar,” kids comprehend the print version more readily—but when enhancements like motion and sound “target the story content,” e-books generally have the edge.

Nostalgia is a force that every new technology must eventually confront. There’s plenty of evidence that writing with pen and paper encodes learning more deeply than typing. But new digital book formats come preloaded with powerful tools that allow readers to annotate, look up words, answer embedded questions, and share their thinking with other readers.

We may not be ready to admit it, but these are precisely the kinds of activities that drive deeper engagement, enhance comprehension, and leave us with a lasting memory of what we’ve read. The future of e-reading, despite the naysayers, remains promising.

9. New Research Makes a Powerful Case for PBL

Many classrooms today still look like they did 100 years ago, when students were preparing for factory jobs. But the world’s moved on: Modern careers demand a more sophisticated set of skills—collaboration, advanced problem-solving, and creativity, for example—and those can be difficult to teach in classrooms that rarely give students the time and space to develop those competencies.

Project-based learning (PBL) would seem like an ideal solution. But critics say PBL places too much responsibility on novice learners, ignoring the evidence about the effectiveness of direct instruction and ultimately undermining subject fluency. Advocates counter that student-centered learning and direct instruction can and should coexist in classrooms.

Now two new large-scale studies —encompassing over 6,000 students in 114 diverse schools across the nation—provide evidence that a well-structured, project-based approach boosts learning for a wide range of students.

In the studies, which were funded by Lucas Education Research, a sister division of Edutopia , elementary and high school students engaged in challenging projects that had them designing water systems for local farms, or creating toys using simple household objects to learn about gravity, friction, and force. Subsequent testing revealed notable learning gains—well above those experienced by students in traditional classrooms—and those gains seemed to raise all boats, persisting across socioeconomic class, race, and reading levels.

10. Tracking a Tumultuous Year for Teachers

The Covid-19 pandemic cast a long shadow over the lives of educators in 2021, according to a year’s worth of research.

The average teacher’s workload suddenly “spiked last spring,” wrote the Center for Reinventing Public Education in its January 2021 report, and then—in defiance of the laws of motion—simply never let up. By the fall, a RAND study recorded an astonishing shift in work habits: 24 percent of teachers reported that they were working 56 hours or more per week, compared to 5 percent pre-pandemic.

The vaccine was the promised land, but when it arrived nothing seemed to change. In an April 2021 survey conducted four months after the first vaccine was administered in New York City, 92 percent of teachers said their jobs were more stressful than prior to the pandemic, up from 81 percent in an earlier survey.

It wasn’t just the length of the work days; a close look at the research reveals that the school system’s failure to adjust expectations was ruinous. It seemed to start with the obligations of hybrid teaching, which surfaced in Edutopia ’s coverage of overseas school reopenings. In June 2020, well before many U.S. schools reopened, we reported that hybrid teaching was an emerging problem internationally, and warned that if the “model is to work well for any period of time,” schools must “recognize and seek to reduce the workload for teachers.” Almost eight months later, a 2021 RAND study identified hybrid teaching as a primary source of teacher stress in the U.S., easily outpacing factors like the health of a high-risk loved one.

New and ever-increasing demands for tech solutions put teachers on a knife’s edge. In several important 2021 studies, researchers concluded that teachers were being pushed to adopt new technology without the “resources and equipment necessary for its correct didactic use.” Consequently, they were spending more than 20 hours a week adapting lessons for online use, and experiencing an unprecedented erosion of the boundaries between their work and home lives, leading to an unsustainable “always on” mentality. When it seemed like nothing more could be piled on—when all of the lights were blinking red—the federal government restarted standardized testing .

Change will be hard; many of the pathologies that exist in the system now predate the pandemic. But creating strict school policies that separate work from rest, eliminating the adoption of new tech tools without proper supports, distributing surveys regularly to gauge teacher well-being, and above all listening to educators to identify and confront emerging problems might be a good place to start, if the research can be believed.

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

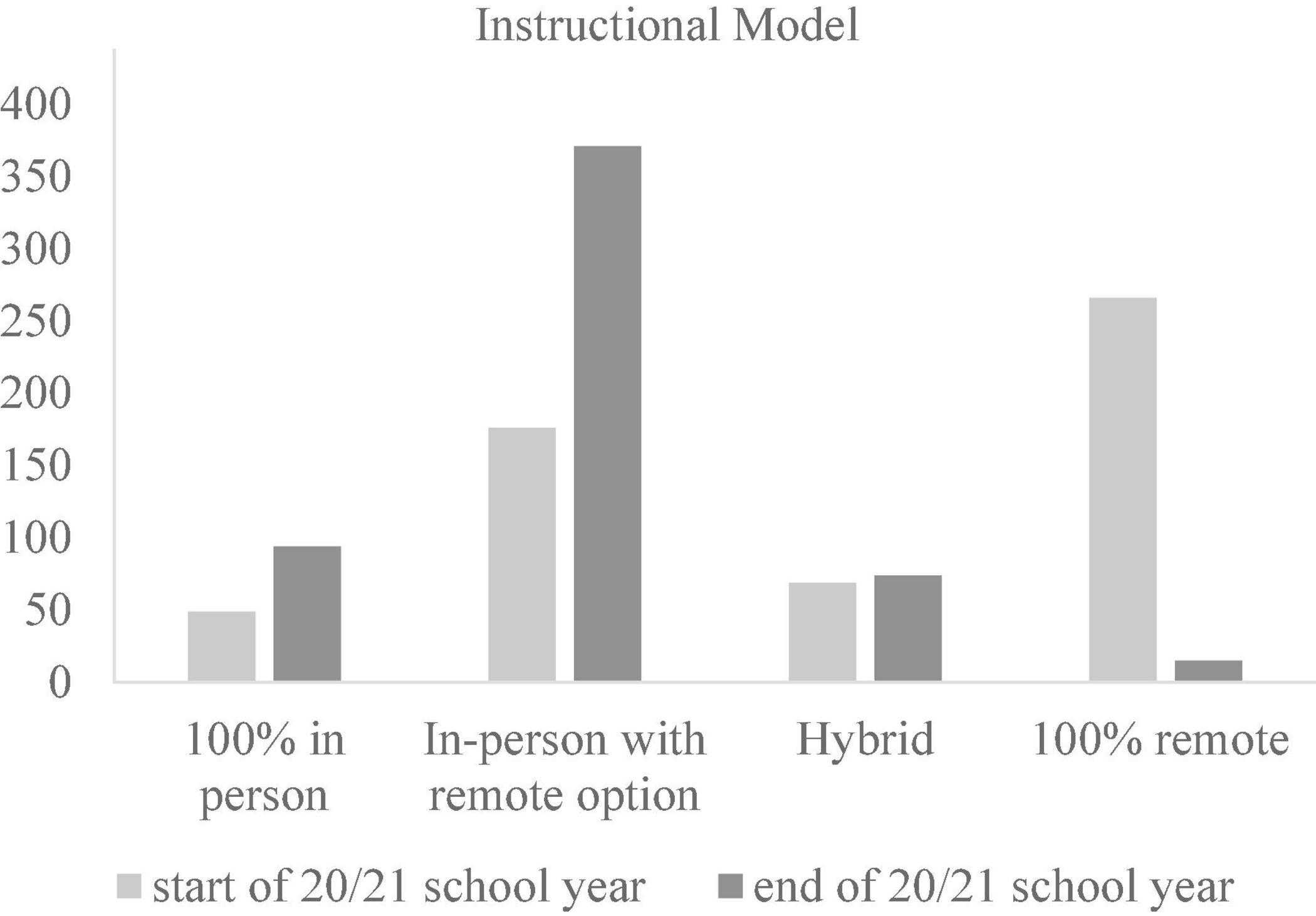

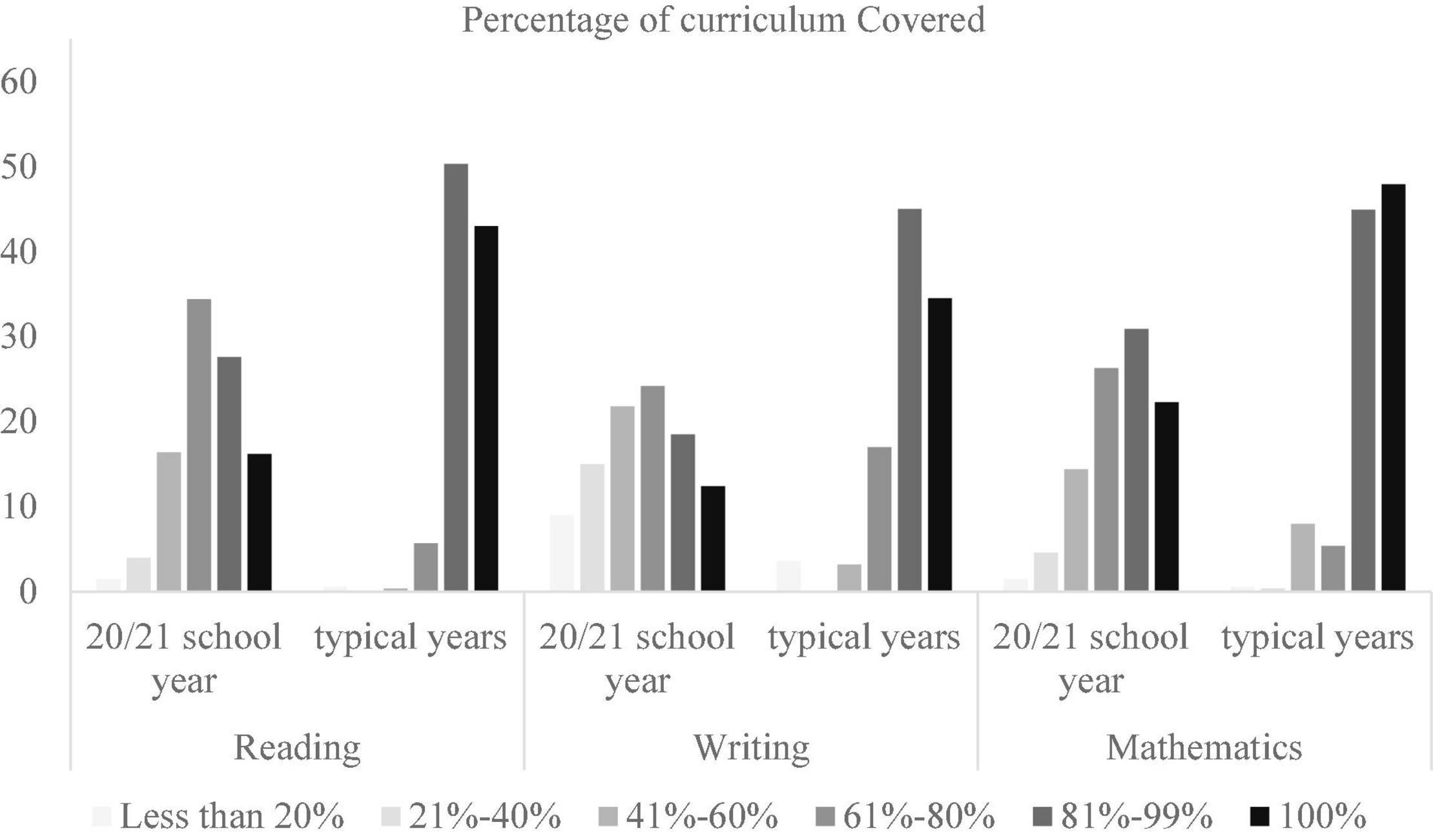

Original research article, impacts of the covid-19 pandemic on student learning and opportunity gaps across the 2020–2021 school year: a national survey of teachers.

- 1 School of Education, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States

- 2 Department of Teaching, Learning, and Culture, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

- 3 School of Education, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA, United States

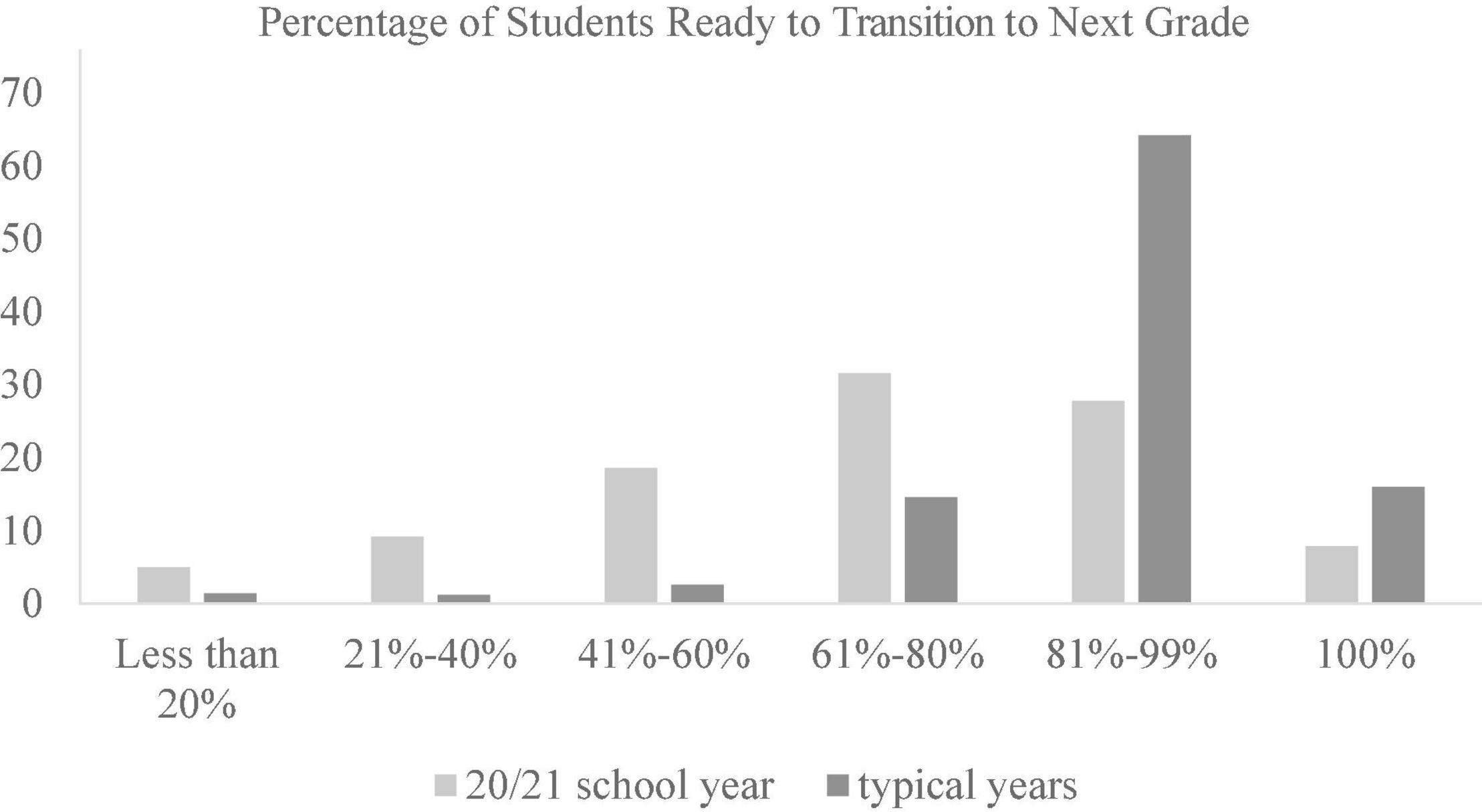

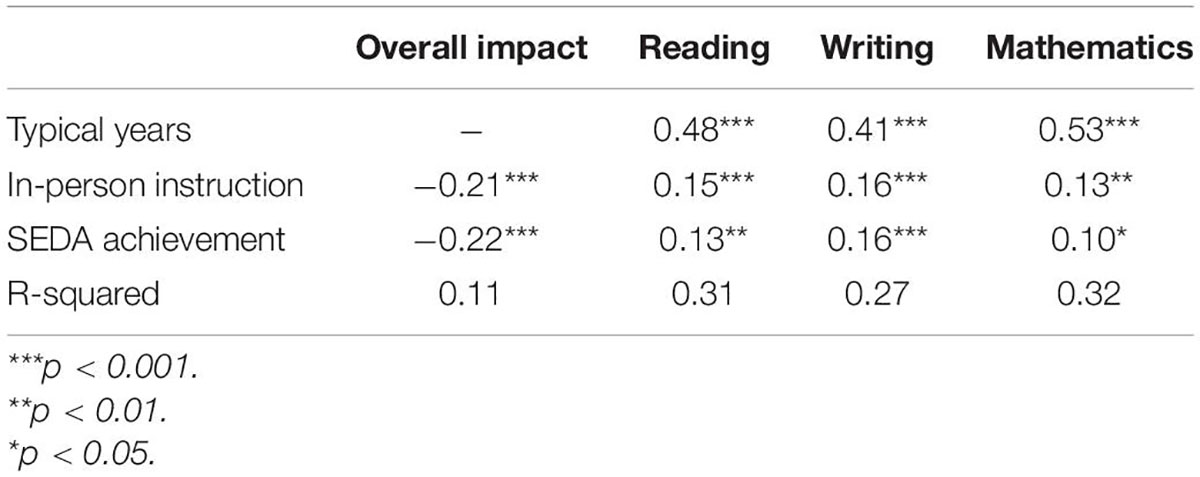

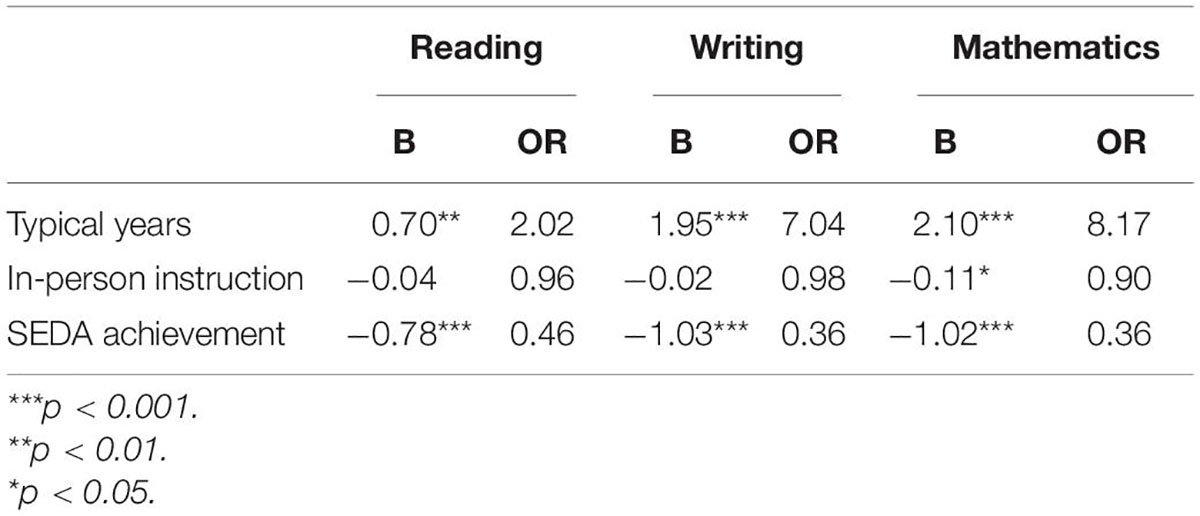

- 4 Department of Special Education and Communication Disorders, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, United States