- En español – ExME

- Em português – EME

Systematic reviews vs meta-analysis: what’s the difference?

Posted on 24th July 2023 by Verónica Tanco Tellechea

You may hear the terms ‘systematic review’ and ‘meta-analysis being used interchangeably’. Although they are related, they are distinctly different. Learn more in this blog for beginners.

What is a systematic review?

According to Cochrane (1), a systematic review attempts to identify, appraise and synthesize all the empirical evidence to answer a specific research question. Thus, a systematic review is where you might find the most relevant, adequate, and current information regarding a specific topic. In the levels of evidence pyramid , systematic reviews are only surpassed by meta-analyses.

To conduct a systematic review, you will need, among other things:

- A specific research question, usually in the form of a PICO question.

- Pre-specified eligibility criteria, to decide which articles will be included or discarded from the review.

- To follow a systematic method that will minimize bias.

You can find protocols that will guide you from both Cochrane and the Equator Network , among other places, and if you are a beginner to the topic then have a read of an overview about systematic reviews.

What is a meta-analysis?

A meta-analysis is a quantitative, epidemiological study design used to systematically assess the results of previous research (2) . Usually, they are based on randomized controlled trials, though not always. This means that a meta-analysis is a mathematical tool that allows researchers to mathematically combine outcomes from multiple studies.

When can a meta-analysis be implemented?

There is always the possibility of conducting a meta-analysis, yet, for it to throw the best possible results it should be performed when the studies included in the systematic review are of good quality, similar designs, and have similar outcome measures.

Why are meta-analyses important?

Outcomes from a meta-analysis may provide more precise information regarding the estimate of the effect of what is being studied because it merges outcomes from multiple studies. In a meta-analysis, data from various trials are combined and generate an average result (1), which is portrayed in a forest plot diagram. Moreover, meta-analysis also include a funnel plot diagram to visually detect publication bias.

Conclusions

A systematic review is an article that synthesizes available evidence on a certain topic utilizing a specific research question, pre-specified eligibility criteria for including articles, and a systematic method for its production. Whereas a meta-analysis is a quantitative, epidemiological study design used to assess the results of articles included in a systematic-review.

| DEFINITION | Synthesis of empirical evidence regarding a specific research question | Statistical tool used with quantitative outcomes of various studies regarding a specific topic |

| RESULTS | Synthesizes relevant and current information regarding a specific research question (qualitative). | Merges multiple outcomes from different researches and provides an average result (quantitative). |

Remember: All meta-analyses involve a systematic review, but not all systematic reviews involve a meta-analysis.

If you would like some further reading on this topic, we suggest the following:

The systematic review – a S4BE blog article

Meta-analysis: what, why, and how – a S4BE blog article

The difference between a systematic review and a meta-analysis – a blog article via Covidence

Systematic review vs meta-analysis: what’s the difference? A 5-minute video from Research Masterminds:

- About Cochrane reviews [Internet]. Cochranelibrary.com. [cited 2023 Apr 30]. Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/about/about-cochrane-reviews

- Haidich AB. Meta-analysis in medical research. Hippokratia. 2010;14(Suppl 1):29–37.

Verónica Tanco Tellechea

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Subscribe to our newsletter

You will receive our monthly newsletter and free access to Trip Premium.

Related Articles

How to read a funnel plot

This blog introduces you to funnel plots, guiding you through how to read them and what may cause them to look asymmetrical.

Heterogeneity in meta-analysis

When you bring studies together in a meta-analysis, one of the things you need to consider is the variability in your studies – this is called heterogeneity. This blog presents the three types of heterogeneity, considers the different types of outcome data, and delves a little more into dealing with the variations.

Natural killer cells in glioblastoma therapy

As seen in a previous blog from Davide, modern neuroscience often interfaces with other medical specialities. In this blog, he provides a summary of new evidence about the potential of a therapeutic strategy born at the crossroad between neurology, immunology and oncology.

- Open access

- Published: 01 August 2019

A step by step guide for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis with simulation data

- Gehad Mohamed Tawfik 1 , 2 ,

- Kadek Agus Surya Dila 2 , 3 ,

- Muawia Yousif Fadlelmola Mohamed 2 , 4 ,

- Dao Ngoc Hien Tam 2 , 5 ,

- Nguyen Dang Kien 2 , 6 ,

- Ali Mahmoud Ahmed 2 , 7 &

- Nguyen Tien Huy 8 , 9 , 10

Tropical Medicine and Health volume 47 , Article number: 46 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

827k Accesses

317 Citations

94 Altmetric

Metrics details

The massive abundance of studies relating to tropical medicine and health has increased strikingly over the last few decades. In the field of tropical medicine and health, a well-conducted systematic review and meta-analysis (SR/MA) is considered a feasible solution for keeping clinicians abreast of current evidence-based medicine. Understanding of SR/MA steps is of paramount importance for its conduction. It is not easy to be done as there are obstacles that could face the researcher. To solve those hindrances, this methodology study aimed to provide a step-by-step approach mainly for beginners and junior researchers, in the field of tropical medicine and other health care fields, on how to properly conduct a SR/MA, in which all the steps here depicts our experience and expertise combined with the already well-known and accepted international guidance.

We suggest that all steps of SR/MA should be done independently by 2–3 reviewers’ discussion, to ensure data quality and accuracy.

SR/MA steps include the development of research question, forming criteria, search strategy, searching databases, protocol registration, title, abstract, full-text screening, manual searching, extracting data, quality assessment, data checking, statistical analysis, double data checking, and manuscript writing.

Introduction

The amount of studies published in the biomedical literature, especially tropical medicine and health, has increased strikingly over the last few decades. This massive abundance of literature makes clinical medicine increasingly complex, and knowledge from various researches is often needed to inform a particular clinical decision. However, available studies are often heterogeneous with regard to their design, operational quality, and subjects under study and may handle the research question in a different way, which adds to the complexity of evidence and conclusion synthesis [ 1 ].

Systematic review and meta-analyses (SR/MAs) have a high level of evidence as represented by the evidence-based pyramid. Therefore, a well-conducted SR/MA is considered a feasible solution in keeping health clinicians ahead regarding contemporary evidence-based medicine.

Differing from a systematic review, unsystematic narrative review tends to be descriptive, in which the authors select frequently articles based on their point of view which leads to its poor quality. A systematic review, on the other hand, is defined as a review using a systematic method to summarize evidence on questions with a detailed and comprehensive plan of study. Furthermore, despite the increasing guidelines for effectively conducting a systematic review, we found that basic steps often start from framing question, then identifying relevant work which consists of criteria development and search for articles, appraise the quality of included studies, summarize the evidence, and interpret the results [ 2 , 3 ]. However, those simple steps are not easy to be reached in reality. There are many troubles that a researcher could be struggled with which has no detailed indication.

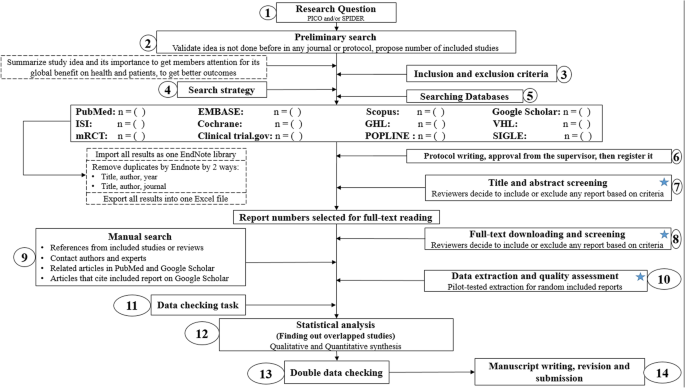

Conducting a SR/MA in tropical medicine and health may be difficult especially for young researchers; therefore, understanding of its essential steps is crucial. It is not easy to be done as there are obstacles that could face the researcher. To solve those hindrances, we recommend a flow diagram (Fig. 1 ) which illustrates a detailed and step-by-step the stages for SR/MA studies. This methodology study aimed to provide a step-by-step approach mainly for beginners and junior researchers, in the field of tropical medicine and other health care fields, on how to properly and succinctly conduct a SR/MA; all the steps here depicts our experience and expertise combined with the already well known and accepted international guidance.

Detailed flow diagram guideline for systematic review and meta-analysis steps. Note : Star icon refers to “2–3 reviewers screen independently”

Methods and results

Detailed steps for conducting any systematic review and meta-analysis.

We searched the methods reported in published SR/MA in tropical medicine and other healthcare fields besides the published guidelines like Cochrane guidelines {Higgins, 2011 #7} [ 4 ] to collect the best low-bias method for each step of SR/MA conduction steps. Furthermore, we used guidelines that we apply in studies for all SR/MA steps. We combined these methods in order to conclude and conduct a detailed flow diagram that shows the SR/MA steps how being conducted.

Any SR/MA must follow the widely accepted Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis statement (PRISMA checklist 2009) (Additional file 5 : Table S1) [ 5 ].

We proposed our methods according to a valid explanatory simulation example choosing the topic of “evaluating safety of Ebola vaccine,” as it is known that Ebola is a very rare tropical disease but fatal. All the explained methods feature the standards followed internationally, with our compiled experience in the conduct of SR beside it, which we think proved some validity. This is a SR under conduct by a couple of researchers teaming in a research group, moreover, as the outbreak of Ebola which took place (2013–2016) in Africa resulted in a significant mortality and morbidity. Furthermore, since there are many published and ongoing trials assessing the safety of Ebola vaccines, we thought this would provide a great opportunity to tackle this hotly debated issue. Moreover, Ebola started to fire again and new fatal outbreak appeared in the Democratic Republic of Congo since August 2018, which caused infection to more than 1000 people according to the World Health Organization, and 629 people have been killed till now. Hence, it is considered the second worst Ebola outbreak, after the first one in West Africa in 2014 , which infected more than 26,000 and killed about 11,300 people along outbreak course.

Research question and objectives

Like other study designs, the research question of SR/MA should be feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant. Therefore, a clear, logical, and well-defined research question should be formulated. Usually, two common tools are used: PICO or SPIDER. PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) is used mostly in quantitative evidence synthesis. Authors demonstrated that PICO holds more sensitivity than the more specific SPIDER approach [ 6 ]. SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type) was proposed as a method for qualitative and mixed methods search.

We here recommend a combined approach of using either one or both the SPIDER and PICO tools to retrieve a comprehensive search depending on time and resources limitations. When we apply this to our assumed research topic, being of qualitative nature, the use of SPIDER approach is more valid.

PICO is usually used for systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trial study. For the observational study (without intervention or comparator), in many tropical and epidemiological questions, it is usually enough to use P (Patient) and O (outcome) only to formulate a research question. We must indicate clearly the population (P), then intervention (I) or exposure. Next, it is necessary to compare (C) the indicated intervention with other interventions, i.e., placebo. Finally, we need to clarify which are our relevant outcomes.

To facilitate comprehension, we choose the Ebola virus disease (EVD) as an example. Currently, the vaccine for EVD is being developed and under phase I, II, and III clinical trials; we want to know whether this vaccine is safe and can induce sufficient immunogenicity to the subjects.

An example of a research question for SR/MA based on PICO for this issue is as follows: How is the safety and immunogenicity of Ebola vaccine in human? (P: healthy subjects (human), I: vaccination, C: placebo, O: safety or adverse effects)

Preliminary research and idea validation

We recommend a preliminary search to identify relevant articles, ensure the validity of the proposed idea, avoid duplication of previously addressed questions, and assure that we have enough articles for conducting its analysis. Moreover, themes should focus on relevant and important health-care issues, consider global needs and values, reflect the current science, and be consistent with the adopted review methods. Gaining familiarity with a deep understanding of the study field through relevant videos and discussions is of paramount importance for better retrieval of results. If we ignore this step, our study could be canceled whenever we find out a similar study published before. This means we are wasting our time to deal with a problem that has been tackled for a long time.

To do this, we can start by doing a simple search in PubMed or Google Scholar with search terms Ebola AND vaccine. While doing this step, we identify a systematic review and meta-analysis of determinant factors influencing antibody response from vaccination of Ebola vaccine in non-human primate and human [ 7 ], which is a relevant paper to read to get a deeper insight and identify gaps for better formulation of our research question or purpose. We can still conduct systematic review and meta-analysis of Ebola vaccine because we evaluate safety as a different outcome and different population (only human).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligibility criteria are based on the PICO approach, study design, and date. Exclusion criteria mostly are unrelated, duplicated, unavailable full texts, or abstract-only papers. These exclusions should be stated in advance to refrain the researcher from bias. The inclusion criteria would be articles with the target patients, investigated interventions, or the comparison between two studied interventions. Briefly, it would be articles which contain information answering our research question. But the most important is that it should be clear and sufficient information, including positive or negative, to answer the question.

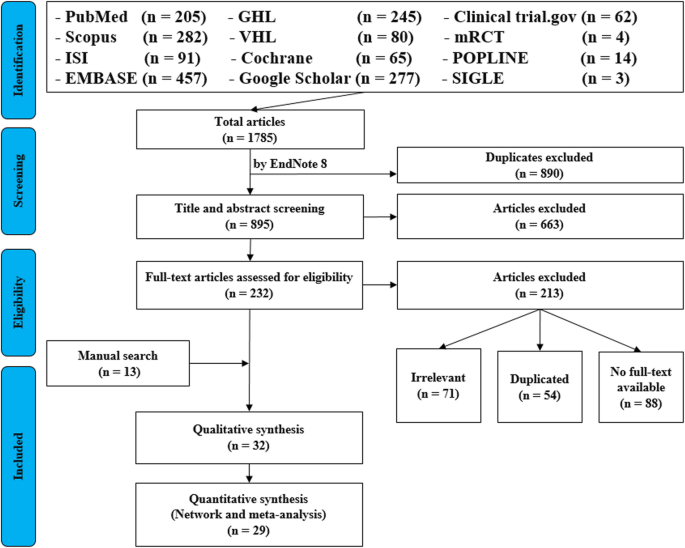

For the topic we have chosen, we can make inclusion criteria: (1) any clinical trial evaluating the safety of Ebola vaccine and (2) no restriction regarding country, patient age, race, gender, publication language, and date. Exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) study of Ebola vaccine in non-human subjects or in vitro studies; (2) study with data not reliably extracted, duplicate, or overlapping data; (3) abstract-only papers as preceding papers, conference, editorial, and author response theses and books; (4) articles without available full text available; and (5) case reports, case series, and systematic review studies. The PRISMA flow diagram template that is used in SR/MA studies can be found in Fig. 2 .

PRISMA flow diagram of studies’ screening and selection

Search strategy

A standard search strategy is used in PubMed, then later it is modified according to each specific database to get the best relevant results. The basic search strategy is built based on the research question formulation (i.e., PICO or PICOS). Search strategies are constructed to include free-text terms (e.g., in the title and abstract) and any appropriate subject indexing (e.g., MeSH) expected to retrieve eligible studies, with the help of an expert in the review topic field or an information specialist. Additionally, we advise not to use terms for the Outcomes as their inclusion might hinder the database being searched to retrieve eligible studies because the used outcome is not mentioned obviously in the articles.

The improvement of the search term is made while doing a trial search and looking for another relevant term within each concept from retrieved papers. To search for a clinical trial, we can use these descriptors in PubMed: “clinical trial”[Publication Type] OR “clinical trials as topic”[MeSH terms] OR “clinical trial”[All Fields]. After some rounds of trial and refinement of search term, we formulate the final search term for PubMed as follows: (ebola OR ebola virus OR ebola virus disease OR EVD) AND (vaccine OR vaccination OR vaccinated OR immunization) AND (“clinical trial”[Publication Type] OR “clinical trials as topic”[MeSH Terms] OR “clinical trial”[All Fields]). Because the study for this topic is limited, we do not include outcome term (safety and immunogenicity) in the search term to capture more studies.

Search databases, import all results to a library, and exporting to an excel sheet

According to the AMSTAR guidelines, at least two databases have to be searched in the SR/MA [ 8 ], but as you increase the number of searched databases, you get much yield and more accurate and comprehensive results. The ordering of the databases depends mostly on the review questions; being in a study of clinical trials, you will rely mostly on Cochrane, mRCTs, or International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). Here, we propose 12 databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE, GHL, VHL, Cochrane, Google Scholar, Clinical trials.gov , mRCTs, POPLINE, and SIGLE), which help to cover almost all published articles in tropical medicine and other health-related fields. Among those databases, POPLINE focuses on reproductive health. Researchers should consider to choose relevant database according to the research topic. Some databases do not support the use of Boolean or quotation; otherwise, there are some databases that have special searching way. Therefore, we need to modify the initial search terms for each database to get appreciated results; therefore, manipulation guides for each online database searches are presented in Additional file 5 : Table S2. The detailed search strategy for each database is found in Additional file 5 : Table S3. The search term that we created in PubMed needs customization based on a specific characteristic of the database. An example for Google Scholar advanced search for our topic is as follows:

With all of the words: ebola virus

With at least one of the words: vaccine vaccination vaccinated immunization

Where my words occur: in the title of the article

With all of the words: EVD

Finally, all records are collected into one Endnote library in order to delete duplicates and then to it export into an excel sheet. Using remove duplicating function with two options is mandatory. All references which have (1) the same title and author, and published in the same year, and (2) the same title and author, and published in the same journal, would be deleted. References remaining after this step should be exported to an excel file with essential information for screening. These could be the authors’ names, publication year, journal, DOI, URL link, and abstract.

Protocol writing and registration

Protocol registration at an early stage guarantees transparency in the research process and protects from duplication problems. Besides, it is considered a documented proof of team plan of action, research question, eligibility criteria, intervention/exposure, quality assessment, and pre-analysis plan. It is recommended that researchers send it to the principal investigator (PI) to revise it, then upload it to registry sites. There are many registry sites available for SR/MA like those proposed by Cochrane and Campbell collaborations; however, we recommend registering the protocol into PROSPERO as it is easier. The layout of a protocol template, according to PROSPERO, can be found in Additional file 5 : File S1.

Title and abstract screening

Decisions to select retrieved articles for further assessment are based on eligibility criteria, to minimize the chance of including non-relevant articles. According to the Cochrane guidance, two reviewers are a must to do this step, but as for beginners and junior researchers, this might be tiresome; thus, we propose based on our experience that at least three reviewers should work independently to reduce the chance of error, particularly in teams with a large number of authors to add more scrutiny and ensure proper conduct. Mostly, the quality with three reviewers would be better than two, as two only would have different opinions from each other, so they cannot decide, while the third opinion is crucial. And here are some examples of systematic reviews which we conducted following the same strategy (by a different group of researchers in our research group) and published successfully, and they feature relevant ideas to tropical medicine and disease [ 9 , 10 , 11 ].

In this step, duplications will be removed manually whenever the reviewers find them out. When there is a doubt about an article decision, the team should be inclusive rather than exclusive, until the main leader or PI makes a decision after discussion and consensus. All excluded records should be given exclusion reasons.

Full text downloading and screening

Many search engines provide links for free to access full-text articles. In case not found, we can search in some research websites as ResearchGate, which offer an option of direct full-text request from authors. Additionally, exploring archives of wanted journals, or contacting PI to purchase it if available. Similarly, 2–3 reviewers work independently to decide about included full texts according to eligibility criteria, with reporting exclusion reasons of articles. In case any disagreement has occurred, the final decision has to be made by discussion.

Manual search

One has to exhaust all possibilities to reduce bias by performing an explicit hand-searching for retrieval of reports that may have been dropped from first search [ 12 ]. We apply five methods to make manual searching: searching references from included studies/reviews, contacting authors and experts, and looking at related articles/cited articles in PubMed and Google Scholar.

We describe here three consecutive methods to increase and refine the yield of manual searching: firstly, searching reference lists of included articles; secondly, performing what is known as citation tracking in which the reviewers track all the articles that cite each one of the included articles, and this might involve electronic searching of databases; and thirdly, similar to the citation tracking, we follow all “related to” or “similar” articles. Each of the abovementioned methods can be performed by 2–3 independent reviewers, and all the possible relevant article must undergo further scrutiny against the inclusion criteria, after following the same records yielded from electronic databases, i.e., title/abstract and full-text screening.

We propose an independent reviewing by assigning each member of the teams a “tag” and a distinct method, to compile all the results at the end for comparison of differences and discussion and to maximize the retrieval and minimize the bias. Similarly, the number of included articles has to be stated before addition to the overall included records.

Data extraction and quality assessment

This step entitles data collection from included full-texts in a structured extraction excel sheet, which is previously pilot-tested for extraction using some random studies. We recommend extracting both adjusted and non-adjusted data because it gives the most allowed confounding factor to be used in the analysis by pooling them later [ 13 ]. The process of extraction should be executed by 2–3 independent reviewers. Mostly, the sheet is classified into the study and patient characteristics, outcomes, and quality assessment (QA) tool.

Data presented in graphs should be extracted by software tools such as Web plot digitizer [ 14 ]. Most of the equations that can be used in extraction prior to analysis and estimation of standard deviation (SD) from other variables is found inside Additional file 5 : File S2 with their references as Hozo et al. [ 15 ], Xiang et al. [ 16 ], and Rijkom et al. [ 17 ]. A variety of tools are available for the QA, depending on the design: ROB-2 Cochrane tool for randomized controlled trials [ 18 ] which is presented as Additional file 1 : Figure S1 and Additional file 2 : Figure S2—from a previous published article data—[ 19 ], NIH tool for observational and cross-sectional studies [ 20 ], ROBINS-I tool for non-randomize trials [ 21 ], QUADAS-2 tool for diagnostic studies, QUIPS tool for prognostic studies, CARE tool for case reports, and ToxRtool for in vivo and in vitro studies. We recommend that 2–3 reviewers independently assess the quality of the studies and add to the data extraction form before the inclusion into the analysis to reduce the risk of bias. In the NIH tool for observational studies—cohort and cross-sectional—as in this EBOLA case, to evaluate the risk of bias, reviewers should rate each of the 14 items into dichotomous variables: yes, no, or not applicable. An overall score is calculated by adding all the items scores as yes equals one, while no and NA equals zero. A score will be given for every paper to classify them as poor, fair, or good conducted studies, where a score from 0–5 was considered poor, 6–9 as fair, and 10–14 as good.

In the EBOLA case example above, authors can extract the following information: name of authors, country of patients, year of publication, study design (case report, cohort study, or clinical trial or RCT), sample size, the infected point of time after EBOLA infection, follow-up interval after vaccination time, efficacy, safety, adverse effects after vaccinations, and QA sheet (Additional file 6 : Data S1).

Data checking

Due to the expected human error and bias, we recommend a data checking step, in which every included article is compared with its counterpart in an extraction sheet by evidence photos, to detect mistakes in data. We advise assigning articles to 2–3 independent reviewers, ideally not the ones who performed the extraction of those articles. When resources are limited, each reviewer is assigned a different article than the one he extracted in the previous stage.

Statistical analysis

Investigators use different methods for combining and summarizing findings of included studies. Before analysis, there is an important step called cleaning of data in the extraction sheet, where the analyst organizes extraction sheet data in a form that can be read by analytical software. The analysis consists of 2 types namely qualitative and quantitative analysis. Qualitative analysis mostly describes data in SR studies, while quantitative analysis consists of two main types: MA and network meta-analysis (NMA). Subgroup, sensitivity, cumulative analyses, and meta-regression are appropriate for testing whether the results are consistent or not and investigating the effect of certain confounders on the outcome and finding the best predictors. Publication bias should be assessed to investigate the presence of missing studies which can affect the summary.

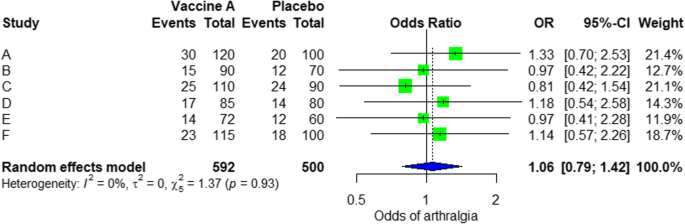

To illustrate basic meta-analysis, we provide an imaginary data for the research question about Ebola vaccine safety (in terms of adverse events, 14 days after injection) and immunogenicity (Ebola virus antibodies rise in geometric mean titer, 6 months after injection). Assuming that from searching and data extraction, we decided to do an analysis to evaluate Ebola vaccine “A” safety and immunogenicity. Other Ebola vaccines were not meta-analyzed because of the limited number of studies (instead, it will be included for narrative review). The imaginary data for vaccine safety meta-analysis can be accessed in Additional file 7 : Data S2. To do the meta-analysis, we can use free software, such as RevMan [ 22 ] or R package meta [ 23 ]. In this example, we will use the R package meta. The tutorial of meta package can be accessed through “General Package for Meta-Analysis” tutorial pdf [ 23 ]. The R codes and its guidance for meta-analysis done can be found in Additional file 5 : File S3.

For the analysis, we assume that the study is heterogenous in nature; therefore, we choose a random effect model. We did an analysis on the safety of Ebola vaccine A. From the data table, we can see some adverse events occurring after intramuscular injection of vaccine A to the subject of the study. Suppose that we include six studies that fulfill our inclusion criteria. We can do a meta-analysis for each of the adverse events extracted from the studies, for example, arthralgia, from the results of random effect meta-analysis using the R meta package.

From the results shown in Additional file 3 : Figure S3, we can see that the odds ratio (OR) of arthralgia is 1.06 (0.79; 1.42), p value = 0.71, which means that there is no association between the intramuscular injection of Ebola vaccine A and arthralgia, as the OR is almost one, and besides, the P value is insignificant as it is > 0.05.

In the meta-analysis, we can also visualize the results in a forest plot. It is shown in Fig. 3 an example of a forest plot from the simulated analysis.

Random effect model forest plot for comparison of vaccine A versus placebo

From the forest plot, we can see six studies (A to F) and their respective OR (95% CI). The green box represents the effect size (in this case, OR) of each study. The bigger the box means the study weighted more (i.e., bigger sample size). The blue diamond shape represents the pooled OR of the six studies. We can see the blue diamond cross the vertical line OR = 1, which indicates no significance for the association as the diamond almost equalized in both sides. We can confirm this also from the 95% confidence interval that includes one and the p value > 0.05.

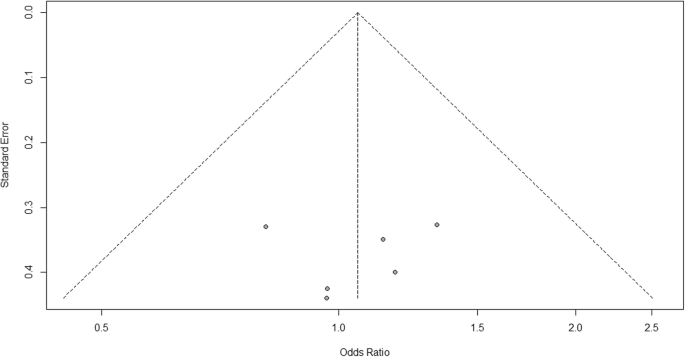

For heterogeneity, we see that I 2 = 0%, which means no heterogeneity is detected; the study is relatively homogenous (it is rare in the real study). To evaluate publication bias related to the meta-analysis of adverse events of arthralgia, we can use the metabias function from the R meta package (Additional file 4 : Figure S4) and visualization using a funnel plot. The results of publication bias are demonstrated in Fig. 4 . We see that the p value associated with this test is 0.74, indicating symmetry of the funnel plot. We can confirm it by looking at the funnel plot.

Publication bias funnel plot for comparison of vaccine A versus placebo

Looking at the funnel plot, the number of studies at the left and right side of the funnel plot is the same; therefore, the plot is symmetry, indicating no publication bias detected.

Sensitivity analysis is a procedure used to discover how different values of an independent variable will influence the significance of a particular dependent variable by removing one study from MA. If all included study p values are < 0.05, hence, removing any study will not change the significant association. It is only performed when there is a significant association, so if the p value of MA done is 0.7—more than one—the sensitivity analysis is not needed for this case study example. If there are 2 studies with p value > 0.05, removing any of the two studies will result in a loss of the significance.

Double data checking

For more assurance on the quality of results, the analyzed data should be rechecked from full-text data by evidence photos, to allow an obvious check for the PI of the study.

Manuscript writing, revision, and submission to a journal

Writing based on four scientific sections: introduction, methods, results, and discussion, mostly with a conclusion. Performing a characteristic table for study and patient characteristics is a mandatory step which can be found as a template in Additional file 5 : Table S3.

After finishing the manuscript writing, characteristics table, and PRISMA flow diagram, the team should send it to the PI to revise it well and reply to his comments and, finally, choose a suitable journal for the manuscript which fits with considerable impact factor and fitting field. We need to pay attention by reading the author guidelines of journals before submitting the manuscript.

The role of evidence-based medicine in biomedical research is rapidly growing. SR/MAs are also increasing in the medical literature. This paper has sought to provide a comprehensive approach to enable reviewers to produce high-quality SR/MAs. We hope that readers could gain general knowledge about how to conduct a SR/MA and have the confidence to perform one, although this kind of study requires complex steps compared to narrative reviews.

Having the basic steps for conduction of MA, there are many advanced steps that are applied for certain specific purposes. One of these steps is meta-regression which is performed to investigate the association of any confounder and the results of the MA. Furthermore, there are other types rather than the standard MA like NMA and MA. In NMA, we investigate the difference between several comparisons when there were not enough data to enable standard meta-analysis. It uses both direct and indirect comparisons to conclude what is the best between the competitors. On the other hand, mega MA or MA of patients tend to summarize the results of independent studies by using its individual subject data. As a more detailed analysis can be done, it is useful in conducting repeated measure analysis and time-to-event analysis. Moreover, it can perform analysis of variance and multiple regression analysis; however, it requires homogenous dataset and it is time-consuming in conduct [ 24 ].

Conclusions

Systematic review/meta-analysis steps include development of research question and its validation, forming criteria, search strategy, searching databases, importing all results to a library and exporting to an excel sheet, protocol writing and registration, title and abstract screening, full-text screening, manual searching, extracting data and assessing its quality, data checking, conducting statistical analysis, double data checking, manuscript writing, revising, and submitting to a journal.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Network meta-analysis

Principal investigator

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis statement

Quality assessment

Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type

Systematic review and meta-analyses

Bello A, Wiebe N, Garg A, Tonelli M. Evidence-based decision-making 2: systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Methods Mol Biol (Clifton, NJ). 2015;1281:397–416.

Article Google Scholar

Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(3):118–21.

Rys P, Wladysiuk M, Skrzekowska-Baran I, Malecki MT. Review articles, systematic reviews and meta-analyses: which can be trusted? Polskie Archiwum Medycyny Wewnetrznej. 2009;119(3):148–56.

PubMed Google Scholar

Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. 2011.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:579.

Gross L, Lhomme E, Pasin C, Richert L, Thiebaut R. Ebola vaccine development: systematic review of pre-clinical and clinical studies, and meta-analysis of determinants of antibody response variability after vaccination. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;74:83–96.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, ... Henry DA. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Giang HTN, Banno K, Minh LHN, Trinh LT, Loc LT, Eltobgy A, et al. Dengue hemophagocytic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis on epidemiology, clinical signs, outcomes, and risk factors. Rev Med Virol. 2018;28(6):e2005.

Morra ME, Altibi AMA, Iqtadar S, Minh LHN, Elawady SS, Hallab A, et al. Definitions for warning signs and signs of severe dengue according to the WHO 2009 classification: systematic review of literature. Rev Med Virol. 2018;28(4):e1979.

Morra ME, Van Thanh L, Kamel MG, Ghazy AA, Altibi AMA, Dat LM, et al. Clinical outcomes of current medical approaches for Middle East respiratory syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2018;28(3):e1977.

Vassar M, Atakpo P, Kash MJ. Manual search approaches used by systematic reviewers in dermatology. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA. 2016;104(4):302.

Naunheim MR, Remenschneider AK, Scangas GA, Bunting GW, Deschler DG. The effect of initial tracheoesophageal voice prosthesis size on postoperative complications and voice outcomes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125(6):478–84.

Rohatgi AJaiWa. Web Plot Digitizer. ht tp. 2014;2.

Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5(1):13.

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):135.

Van Rijkom HM, Truin GJ, Van’t Hof MA. A meta-analysis of clinical studies on the caries-inhibiting effect of fluoride gel treatment. Carries Res. 1998;32(2):83–92.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Tawfik GM, Tieu TM, Ghozy S, Makram OM, Samuel P, Abdelaal A, et al. Speech efficacy, safety and factors affecting lifetime of voice prostheses in patients with laryngeal cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15_suppl):e18031-e.

Wannemuehler TJ, Lobo BC, Johnson JD, Deig CR, Ting JY, Gregory RL. Vibratory stimulus reduces in vitro biofilm formation on tracheoesophageal voice prostheses. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(12):2752–7.

Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355.

RevMan The Cochrane Collaboration %J Copenhagen TNCCTCC. Review Manager (RevMan). 5.0. 2008.

Schwarzer GJRn. meta: An R package for meta-analysis. 2007;7(3):40-45.

Google Scholar

Simms LLH. Meta-analysis versus mega-analysis: is there a difference? Oral budesonide for the maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease: Faculty of Graduate Studies, University of Western Ontario; 1998.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted (in part) at the Joint Usage/Research Center on Tropical Disease, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nagasaki University, Japan.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt

Gehad Mohamed Tawfik

Online research Club http://www.onlineresearchclub.org/

Gehad Mohamed Tawfik, Kadek Agus Surya Dila, Muawia Yousif Fadlelmola Mohamed, Dao Ngoc Hien Tam, Nguyen Dang Kien & Ali Mahmoud Ahmed

Pratama Giri Emas Hospital, Singaraja-Amlapura street, Giri Emas village, Sawan subdistrict, Singaraja City, Buleleng, Bali, 81171, Indonesia

Kadek Agus Surya Dila

Faculty of Medicine, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Sudan

Muawia Yousif Fadlelmola Mohamed

Nanogen Pharmaceutical Biotechnology Joint Stock Company, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Dao Ngoc Hien Tam

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Thai Binh University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Thai Binh, Vietnam

Nguyen Dang Kien

Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

Ali Mahmoud Ahmed

Evidence Based Medicine Research Group & Faculty of Applied Sciences, Ton Duc Thang University, Ho Chi Minh City, 70000, Vietnam

Nguyen Tien Huy

Faculty of Applied Sciences, Ton Duc Thang University, Ho Chi Minh City, 70000, Vietnam

Department of Clinical Product Development, Institute of Tropical Medicine (NEKKEN), Leading Graduate School Program, and Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Nagasaki University, 1-12-4 Sakamoto, Nagasaki, 852-8523, Japan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

NTH and GMT were responsible for the idea and its design. The figure was done by GMT. All authors contributed to the manuscript writing and approval of the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nguyen Tien Huy .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:.

Figure S1. Risk of bias assessment graph of included randomized controlled trials. (TIF 20 kb)

Additional file 2:

Figure S2. Risk of bias assessment summary. (TIF 69 kb)

Additional file 3:

Figure S3. Arthralgia results of random effect meta-analysis using R meta package. (TIF 20 kb)

Additional file 4:

Figure S4. Arthralgia linear regression test of funnel plot asymmetry using R meta package. (TIF 13 kb)

Additional file 5:

Table S1. PRISMA 2009 Checklist. Table S2. Manipulation guides for online database searches. Table S3. Detailed search strategy for twelve database searches. Table S4. Baseline characteristics of the patients in the included studies. File S1. PROSPERO protocol template file. File S2. Extraction equations that can be used prior to analysis to get missed variables. File S3. R codes and its guidance for meta-analysis done for comparison between EBOLA vaccine A and placebo. (DOCX 49 kb)

Additional file 6:

Data S1. Extraction and quality assessment data sheets for EBOLA case example. (XLSX 1368 kb)

Additional file 7:

Data S2. Imaginary data for EBOLA case example. (XLSX 10 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Tawfik, G.M., Dila, K.A.S., Mohamed, M.Y.F. et al. A step by step guide for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis with simulation data. Trop Med Health 47 , 46 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-019-0165-6

Download citation

Received : 30 January 2019

Accepted : 24 May 2019

Published : 01 August 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-019-0165-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Tropical Medicine and Health

ISSN: 1349-4147

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Systematic Reviews and Meta Analysis

- Getting Started

- Guides and Standards

- Review Protocols

- Databases and Sources

- Randomized Controlled Trials

- Controlled Clinical Trials

- Observational Designs

- Tests of Diagnostic Accuracy

- Software and Tools

- Where do I get all those articles?

- Collaborations

- EPI 233/528

- Countway Mediated Search

- Risk of Bias (RoB)

Cochrane Handbook

The Cochrane Handbook isn't set down to be a standard, but it has become the de facto standard for planning and carrying out a systematic review. Chapter 6, Searching for Studies, is most helpful in planning your review.

Scoping Reviews, JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis

The Joanna Briggs Institute provides extensive guidance for their authors in producing both systematic and scoping reviews. Their chapter on scoping reviews provides a succinct overview of the scoping review process. JBI maintains a page with other materials for scoping reviewers.

Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews

Very good chapters on conducting a review, most of which were published as articles in the Journal of Clincal Epidemiology.

Institutes of Medicine Standards for Systematic Reviews

The IOM standards promote objective, transparent, and scientifically valid systematic reviews. They address the entire systematic review process, from locating, screening, and selecting studies for the review, to synthesizing the findings (including meta-analysis) and assessing the overall quality of the body of evidence, to producing the final review report.

Systematic Reviews: CRD's Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care

Provides a succinct outline for carrying out systematic reviews and well as details about constructing a protocol, testing for bias, and other aspects of the review process. Includes examples.

Systematic reviews to support evidence-based medicine how to review and apply findings of healthcare research

Khan, K., & Royal Society of Medicine. 2nd ed, 2013. London [England]: Hodder Annold. [Harvard ID required]

Systematic reviews to answer health care questions

Nelson, H. (2014). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Harvard ID required]

Systematic Review Toolbox

Not a guide or standard but a clearinghouse for all things systematic review. Check here for templates, reporting standards, screening tools, risk of bias assessment, etc.

Reporting Standards: PRISMA and MOOSE

You will improve the quality of your review by adhering to the standards below. Using the approriate standard can reassure editors and reviewers that you have conscienciously carried out your review.

http://www.prisma-statement.org/ The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. A 27-item checklist, PRISMA focuses on randomized trials but can also be used as a basis for reporting systematic reviews of other types of research, particularly evaluations of interventions. PRISMA may also be useful for critical appraisal of published systematic reviews, although it is not a quality assessment instrument to gauge the quality of a systematic review.

Consider using PRISMA-P when completing your protocol. PRISMA-P is a 17-item checklist for elements considered essential in protocol for a systematic review or meta-analysis. The documentation contains an excellent rationale for completing a protocol, too.

Use PRISMA-ScR, a 20-item checklist, for reporting scoping reviews. The documentation provides a clear overview of scoping reviews.

Further Reading:

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009 Jul 21;6(7):e1000097. Epub 2009 Jul 21. PubMed PMID: 19621072 .

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009 Jul 21;6(7):e1000100. Epub 2009 Jul 21. PubMed PMID: 19621070 .

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review andmeta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015 Jan 2;349:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. PubMed PMID: 25555855 .

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review andmeta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 1;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. PubMed PMID: 25554246 .

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tunçalp Ö, Straus SE. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Oct 2;169(7):467-473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. Epub 2018 Sep 4. PMID: 30178033 .

Also published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, BMJ, and the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology.

MOOSE Guidelines

http://www.consort-statement.org/Media/Default/Downloads/Other%20Instruments/MOOSE%20Statement%202000.pdf Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist contains specifications for reporting of meta-analyses of observational studies in epidemiology. Editors will expect you to follow and cite this checklist. It refers to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies, a method of rating each observational study in your meta-analysis.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000 Apr 19;283(15):2008-12. PubMed PMID: 10789670 .

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Review Protocols >>

- Last Updated: Feb 26, 2024 3:17 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/meta-analysis

| | |

Literature Review, Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Literature reviews can be a good way to narrow down theoretical interests; refine a research question; understand contemporary debates; and orientate a particular research project. It is very common for PhD theses to contain some element of reviewing the literature around a particular topic. It’s typical to have an entire chapter devoted to reporting the result of this task, identifying gaps in the literature and framing the collection of additional data.

Systematic review is a type of literature review that uses systematic methods to collect secondary data, critically appraise research studies, and synthesise findings. Systematic reviews are designed to provide a comprehensive, exhaustive summary of current theories and/or evidence and published research (Siddaway, Wood & Hedges, 2019) and may be qualitative or qualitative. Relevant studies and literature are identified through a research question, summarised and synthesized into a discrete set of findings or a description of the state-of-the-art. This might result in a ‘literature review’ chapter in a doctoral thesis, but can also be the basis of an entire research project.

Meta-analysis is a specialised type of systematic review which is quantitative and rigorous, often comparing data and results across multiple similar studies. This is a common approach in medical research where several papers might report the results of trials of a particular treatment, for instance. The meta-analysis then statistical techniques to synthesize these into one summary. This can have a high statistical power but care must be taken not to introduce bias in the selection and filtering of evidence.

Whichever type of review is employed, the process is similarly linear. The first step is to frame a question which can guide the review. This is used to identify relevant literature, often through searching subject-specific scientific databases. From these results the most relevant will be identified. Filtering is important here as there will be time constraints that prevent the researcher considering every possible piece of evidence or theoretical viewpoint. Once a concrete evidence base has been identified, the researcher extracts relevant data before reporting the synthesized results in an extended piece of writing.

Literature Review: GO-GN Insights

Sarah Lambert used a systematic review of literature with both qualitative and quantitative phases to investigate the question “How can open education programs be reconceptualised as acts of social justice to improve the access, participation and success of those who are traditionally excluded from higher education knowledge and skills?”

“My PhD research used systematic review, qualitative synthesis, case study and discourse analysis techniques, each was underpinned and made coherent by a consistent critical inquiry methodology and an overarching research question. “Systematic reviews are becoming increasingly popular as a way to collect evidence of what works across multiple contexts and can be said to address some of the weaknesses of case study designs which provide detail about a particular context – but which is often not replicable in other socio-cultural contexts (such as other countries or states.) Publication of systematic reviews that are done according to well defined methods are quite likely to be published in high-ranking journals – my PhD supervisors were keen on this from the outset and I was encouraged along this path. “Previously I had explored social realist authors and a social realist approach to systematic reviews (Pawson on realist reviews) but they did not sufficiently embrace social relations, issues of power, inclusion/exclusion. My supervisors had pushed me to explain what kind of realist review I intended to undertake, and I found out there was a branch of critical realism which was briefly of interest. By getting deeply into theory and trying out ways of combining theory I also feel that I have developed a deeper understanding of conceptual working and the different ways theories can be used at all stagesof research and even how to come up with novel conceptual frameworks.”

Useful references for Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis: Finfgeld-Connett (2014); Lambert (2020); Siddaway, Wood & Hedges (2019)

Research Methods Handbook Copyright © 2020 by Rob Farrow; Francisco Iniesto; Martin Weller; and Rebecca Pitt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

University of Houston Libraries

- Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- Review Comparison Chart

- Decision Tools

- Systematic Review

- Meta-Analysis

- Scoping Review

- Mapping Review

- Integrative Review

- Rapid Review

- Realist Review

- Umbrella Review

- Review of Complex Interventions

- Diagnostic Test Accuracy Review

- Narrative Literature Reviews

- Standards and Guidelines

Navigate the links below to jump to a specific section of the page:

When is conducting a Meta-Analysis appropriate?

Methods and guidance, examples of meta-analyses, supplementary resources.

A meta-analysis is defined by Haidlich (2010) as "quantitative, formal, epidemiological study design used to systematically assess previous research studies to derive conclusions about that body of research. Outcomes from a meta-analysis may include a more precise estimate of the effect of treatment or risk factor for disease, or other outcomes , than any individual study contributing to the pooled analysis" (p.29).

According to Grant & Booth (2009) , a meta-analysis is defined as a "technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the results" (p.94).

Characteristics

- A meta-analysis can only be conducted after the completion of a systematic review , as the meta-analysis statistically summarizes the findings from the studies synthesized in a particular systematic review. A meta-analysis cannot exist with a pre-existing systematic review . Grant & Booth (2009) state that "although many systematic reviews present their results without statistically combining data [in a meta-analysis], a good systematic review is essential to a meta-analysis of the literature" (p.98).

- Conducting a meta-analysis requires all studies that will be statistically summarized to be similar - i.e. that population, intervention, and comparison. Grant & Booth (2009) state that "more importantly, it requires that the same measure or outcome be measured in the same way at the same time intervals" (p.98).

When to Use It: According to the Cochrane Handbook , "an important step in a systematic review is the thoughtful consideration of whether it is appropriate to combine the numerical results of all, or perhaps some, of the studies. Such a meta-analysis yields an overall statistic (together with its confidence interval) that summarizes the effectiveness of an experimental intervention compared with a comparator intervention" (section 10.2).

Conducting meta-analyses can have the following benefits, according to Deeks et al. (2021, section 10.2) :

- To improve precision. Many studies are too small to provide convincing evidence about intervention effects in isolation. Estimation is usually improved when it is based on more information.

- To answer questions not posed by the individual studies. Primary studies often involve a specific type of participant and explicitly defined interventions. A selection of studies in which these characteristics differ can allow investigation of the consistency of effect across a wider range of populations and interventions. It may also, if relevant, allow reasons for differences in effect estimates to be investigated.

- To settle controversies arising from apparently conflicting studies or to generate new hypotheses. Statistical synthesis of findings allows the degree of conflict to be formally assessed, and reasons for different results to be explored and quantified.

The following resource provides further support on conducting a meta-analysis.

Methods & Guidance

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses

A comprehensive overview on meta-analyses within the Cochrane Handbook.

Reporting Guideline

- PRISMA 2020 checklist

PRISMA (2020) is a 27-item checklist that replaces the PRISMA (2009) statement , which ensures proper and transparent reporting for each element in a systematic review and meta-analysis. "It is an expanded checklist that details reporting recommendations for each item, the PRISMA 2020 abstract checklist, and the revised flow diagrams for original and updated reviews."

- Marioni, R. E., Suderman, M., Chen, B. H., Horvath, S., Bandinelli, S., Morris, T., Beck, S., Ferrucci, L., Pedersen, N. L., Relton, C. L., Deary, I. J., & Hägg, S. (2019). Tracking the epigenetic clock across the human life course: a meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort data . The journals of gerontology: Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences , 74 (1), 57–61. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly060

Deeks, J.J., Higgins, J.P.T., & Altman, D.G. (Eds.). (2021). Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses . In Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., & Welch, V.A. (Eds.), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2. Cochrane. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies . Health information and libraries journal , 26 (2), 91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Haidich A. B. (2010). Meta-analysis in medical research . Hippokratia , 14 (Suppl 1), 29–37.

Seidler, A.L., Hunter, K.E., Cheyne, S., Ghersi, D., Berlin, J.A., & Askie, L. (2019). A guide to prospective meta-analysis . BMJ , 367 , l5342. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5342

- << Previous: Systematic Review

- Next: Scoping Review >>

Limitations of a Meta-Analysis

The following challenges of conducting meta-analyses in systematic reviews are derived from Grant & Booth (2009) , Haidlich (2010) , and Deeks et al. (2021) .

- Can be challenging to ensure that studies used in a meta-analysis are similar enough, which is a crucial component

- Meta-analyses can perhaps be misleading due to biases such as those concerning specific study designs, reporting, and biases within studies

Medical Librarian

- Last Updated: Sep 5, 2023 11:14 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uh.edu/reviews

Main Navigation Menu

Systematic reviews.

- Getting Started with Systematic Reviews

What is a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Differences between systematic and literature reviews.

- Finding and Evaluating Existing Systematic Reviews

- Steps in a Systematic Review

- Step 1: Developing a Question

- Step 2: Selecting Databases

- Step 3: Grey Literature

- Step 4: Registering a Systematic Review Protocol

- Step 5: Translate Search Strategies

- Step 6: Citation Management Tools

- Step 7: Article Screening

- Other Resources

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

A systematic review collects and analyzes all evidence that answers a specific research question. In a systematic review, a question needs to be clearly defined and have inclusion and exclusion criteria. In general, specific and systematic methods selected are intended to minimize bias. This is followed by an extensive search of the literature and a critical analysis of the search results. The reason why a systematic review is conducted is to provide a current evidence-based answer to a specific question that in turn helps to inform decision making. Check out the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Cochrane Reviews links to learn more about Systematic Reviews.

A systematic review can be combined with a meta-analysis. A meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of a systematic review. Not every systematic review contains a meta-analysis. A meta-analysis may not be appropriate if the designs of the studies are too different, if there are concerns about the quality of studies, if the outcomes measured are not sufficiently similar for the result across the studies to be meaningful.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Systematic Reviews . Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/library/researchguides/sytemsaticreviews.html

Cochrane Library. (n.d.). About Cochrane Reviews . Retrieved from https://www.cochranelibrary.com/about/about-cochrane-reviews

Source: Kysh, Lynn (2013): Difference between a systematic review and a literature review. [figshare]. Available at: https://figshare.com/articles/Difference_between_a_systematic_review_and_a_literature_review/766364

- << Previous: Getting Started with Systematic Reviews

- Next: Finding and Evaluating Existing Systematic Reviews >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 1:42 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucmo.edu/systematicreviews

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Biomedical Library Guides

Systematic Reviews

- Types of Literature Reviews

What Makes a Systematic Review Different from Other Types of Reviews?

- Planning Your Systematic Review

- Database Searching

- Creating the Search

- Search Filters and Hedges

- Grey Literature

- Managing and Appraising Results

- Further Resources

Reproduced from Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26: 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

| Aims to demonstrate writer has extensively researched literature and critically evaluated its quality. Goes beyond mere description to include degree of analysis and conceptual innovation. Typically results in hypothesis or mode | Seeks to identify most significant items in the field | No formal quality assessment. Attempts to evaluate according to contribution | Typically narrative, perhaps conceptual or chronological | Significant component: seeks to identify conceptual contribution to embody existing or derive new theory | |

| Generic term: published materials that provide examination of recent or current literature. Can cover wide range of subjects at various levels of completeness and comprehensiveness. May include research findings | May or may not include comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Typically narrative | Analysis may be chronological, conceptual, thematic, etc. | |

| Mapping review/ systematic map | Map out and categorize existing literature from which to commission further reviews and/or primary research by identifying gaps in research literature | Completeness of searching determined by time/scope constraints | No formal quality assessment | May be graphical and tabular | Characterizes quantity and quality of literature, perhaps by study design and other key features. May identify need for primary or secondary research |

| Technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the results | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching. May use funnel plot to assess completeness | Quality assessment may determine inclusion/ exclusion and/or sensitivity analyses | Graphical and tabular with narrative commentary | Numerical analysis of measures of effect assuming absence of heterogeneity | |

| Refers to any combination of methods where one significant component is a literature review (usually systematic). Within a review context it refers to a combination of review approaches for example combining quantitative with qualitative research or outcome with process studies | Requires either very sensitive search to retrieve all studies or separately conceived quantitative and qualitative strategies | Requires either a generic appraisal instrument or separate appraisal processes with corresponding checklists | Typically both components will be presented as narrative and in tables. May also employ graphical means of integrating quantitative and qualitative studies | Analysis may characterise both literatures and look for correlations between characteristics or use gap analysis to identify aspects absent in one literature but missing in the other | |

| Generic term: summary of the [medical] literature that attempts to survey the literature and describe its characteristics | May or may not include comprehensive searching (depends whether systematic overview or not) | May or may not include quality assessment (depends whether systematic overview or not) | Synthesis depends on whether systematic or not. Typically narrative but may include tabular features | Analysis may be chronological, conceptual, thematic, etc. | |

| Method for integrating or comparing the findings from qualitative studies. It looks for ‘themes’ or ‘constructs’ that lie in or across individual qualitative studies | May employ selective or purposive sampling | Quality assessment typically used to mediate messages not for inclusion/exclusion | Qualitative, narrative synthesis | Thematic analysis, may include conceptual models | |

| Assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue, by using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research | Completeness of searching determined by time constraints | Time-limited formal quality assessment | Typically narrative and tabular | Quantities of literature and overall quality/direction of effect of literature | |

| Preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature. Aims to identify nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research) | Completeness of searching determined by time/scope constraints. May include research in progress | No formal quality assessment | Typically tabular with some narrative commentary | Characterizes quantity and quality of literature, perhaps by study design and other key features. Attempts to specify a viable review | |

| Tend to address more current matters in contrast to other combined retrospective and current approaches. May offer new perspectives | Aims for comprehensive searching of current literature | No formal quality assessment | Typically narrative, may have tabular accompaniment | Current state of knowledge and priorities for future investigation and research | |

| Seeks to systematically search for, appraise and synthesis research evidence, often adhering to guidelines on the conduct of a review | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching | Quality assessment may determine inclusion/exclusion | Typically narrative with tabular accompaniment | What is known; recommendations for practice. What remains unknown; uncertainty around findings, recommendations for future research | |

| Combines strengths of critical review with a comprehensive search process. Typically addresses broad questions to produce ‘best evidence synthesis’ | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Minimal narrative, tabular summary of studies | What is known; recommendations for practice. Limitations | |

| Attempt to include elements of systematic review process while stopping short of systematic review. Typically conducted as postgraduate student assignment | May or may not include comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Typically narrative with tabular accompaniment | What is known; uncertainty around findings; limitations of methodology | |

| Specifically refers to review compiling evidence from multiple reviews into one accessible and usable document. Focuses on broad condition or problem for which there are competing interventions and highlights reviews that address these interventions and their results | Identification of component reviews, but no search for primary studies | Quality assessment of studies within component reviews and/or of reviews themselves | Graphical and tabular with narrative commentary | What is known; recommendations for practice. What remains unknown; recommendations for future research |

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Planning Your Systematic Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 23, 2024 3:40 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/systematicreviews

The Guide to Literature Reviews

- What is a Literature Review?

- The Purpose of Literature Reviews

- Guidelines for Writing a Literature Review

- How to Organize a Literature Review?

- Software for Literature Reviews

- Using Artificial Intelligence for Literature Reviews

- How to Conduct a Literature Review?

- Common Mistakes and Pitfalls in a Literature Review

- Methods for Literature Reviews

- What is a Systematic Literature Review?

- What is a Narrative Literature Review?

- What is a Descriptive Literature Review?

- What is a Scoping Literature Review?

- What is a Realist Literature Review?

- What is a Critical Literature Review?

- Introduction

What are the differences between a meta-analysis and a literature review?

- How to conduct a meta-analysis?

When to conduct meta-analyses?

- What is an Umbrella Literature Review?

- Differences Between Annotated Bibliographies and Literature Reviews

- Literature Review vs. Theoretical Framework

- How to Write a Literature Review?

- How to Structure a Literature Review?

- How to Make a Cover Page for a Literature Review?

- How to Write an Abstract for a Literature Review?

- How to Write a Literature Review Introduction?

- How to Write the Body of a Literature Review?

- How to Write a Literature Review Conclusion?

- How to Make a Literature Review Bibliography?

- How to Format a Literature Review?

- How Long Should a Literature Review Be?

- Examples of Literature Reviews

- How to Present a Literature Review?

- How to Publish a Literature Review?

Meta-Analysis vs. Literature Review

A meta-analysis is a statistical method used to combine data from multiple independent studies, often conducted as part of comprehensive literature reviews to provide more precise estimates and robust conclusions. Its purpose is to provide a more precise estimate of effect sizes by aggregating results from various studies. Meta-analyses are crucial in evidence-based medicine as they provide robust conclusions based on empirical evidence.

The primary purpose of a meta-analysis is to synthesize quantitative data from multiple studies to arrive at a single conclusion. By combining results, a meta-analysis can increase statistical power, making it possible to detect effects that may be missed in individual studies. It helps to resolve uncertainty when studies disagree and provides a comprehensive understanding of effect size across different contexts and conditions.

Meta-analyses are important because they offer a higher level of evidence than individual studies. They help researchers and practitioners make informed decisions by summarizing the best available evidence. In clinical settings, meta-analyses can guide treatment choices by comparing the effectiveness of different interventions. Meta-analyses help identify gaps in existing research, paving the way for future studies. They are also essential for developing guidelines and policies based on a thorough synthesis of the evidence.

Although meta-analyses are commonly associated with quantitative research , they can also be applied to qualitative research through a process known as meta-synthesis. Meta-synthesis involves systematically reviewing and integrating findings from multiple qualitative studies to draw broader conclusions. This approach allows researchers to combine qualitative data to develop new theories, understand complex phenomena, and gain insights into contextual factors.

Using meta-synthesis, qualitative meta-analyses can help provide a deeper understanding of a research topic by incorporating diverse perspectives and experiences from various studies. This method can reveal patterns and themes that might not be evident in individual qualitative studies, thereby enhancing the richness and depth of the analysis. By combining the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative research, meta-analyses can offer a more comprehensive view of the research landscape, supporting evidence-based practice and informed decision-making.

A meta-analysis literature review combines elements of both meta-analysis and traditional literature review methodologies. It is a comprehensive approach that includes both a qualitative summary and a quantitative synthesis of research findings. It is a hybrid approach that leverages the strengths of both meta-analysis and traditional literature reviews to provide a thorough and nuanced understanding of a research topic. Read this article to find out more about the differences, and when to use it.

A meta-analysis and literature reviews differ in purpose, methodology, and outcomes. The primary purpose of a meta-analysis is to provide a quantitative analysis of data from multiple studies, producing a precise estimate of the effect size through statistical methods. A literature review synthesizes findings to offer an overview of current knowledge, identify gaps, and suggest future research areas. Literature reviews can be systematic, scoping, or narrative reviews among others.

Meta-analyses use systematic methods, including defining inclusion and exclusion criteria, conducting a systematic search, extracting data, and applying statistical methods such as calculating the standardized mean difference or risk ratio. Other reviews, like systematic and scoping reviews, summarize relevant studies without combining results statistically. Narrative reviews provide qualitative summaries and interpretations.

Quality literature reviews start with ATLAS.ti

From searching literature to analyzing it, ATLAS.ti is there for you at every step. See how with a free trial.

The outcome of a meta-analysis is a quantitative synthesis, offering more precise estimates of key variable effect sizes and identifying patterns through subgroup analysis and forest plots. Systematic reviews provide comprehensive literature summaries, highlighting research strengths and weaknesses. Scoping reviews map key concepts and evidence, while narrative reviews offer critical analysis.