Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6.3 Types of Consumer Decisions

As you read through the stages of the decision making process, did you think “Wait a minute. I do this sometimes but not all the time”? That is indicative of the different levels of involvement within the decision making process. In this section, we will examine this difference in more detail and how it may impact the marketing strategy.

Levels of Involvement in Decision Making

As you have seen, many factors influence a consumer’s behavior. Depending on a consumer’s experience and knowledge, some consumers may be able to make quick purchase decisions and other consumers may need to get information and be more involved in the decision process before making a purchase. The level of involvement reflects how personally important or interested you are in consuming a product and how much information you need to make a decision. The level of involvement in buying decisions may be considered a continuum from decisions that are fairly routine (consumers are not very involved) to decisions that require extensive thought and a high level of involvement. Whether a decision is low, high, or limited, involvement varies by consumer, not by product, although some products such as purchasing a house typically require a high-involvement for all consumers. Consumers with no experience purchasing a product may have more involvement than someone who is replacing a product.

You have probably thought about many products you want or need but never did much more than that. At other times, you’ve probably looked at dozens of products, compared them, and then decided not to purchase any one of them. When you run out of products such as milk or bread that you buy on a regular basis, you may buy the product as soon as you recognize the need because you do not need to search for information or evaluate alternatives. As Nike would put it, you “just do it.” Low-involvement decisions are, however, typically products that are relatively inexpensive and pose a low risk to the buyer if they makes a mistake by purchasing them.

Consumers often engage in routine, or habitual, behavior when they make low-involvement decisions—that is, they make automatic purchase decisions based on limited information or information they have gathered in the past. For example, if you always order a Diet Coke at lunch, you’re engaging in routine response behavior. You may not even think about other drink options at lunch because your routine is to order a Diet Coke, and you simply do it. Similarly, if you run out of Diet Coke at home, you may buy more without any information search.

Some low-involvement purchases are made with no planning or previous thought. These buying decisions are called impulse buying. While you’re waiting to check out at the grocery store, perhaps you see a magazine with the latest celebrity or influencer on the cover and buy it on the spot simply because you want it. You might see a roll of tape at a check-out stand and remember you need one or you might see a bag of chips and realize you’re hungry or just want them.

By contrast, high-involvement decisions carry a higher risk to buyers if they fail, are complex, and/or have high price tags. A car, a house, and an insurance policy are examples. These items are not purchased often but are relevant and important to the buyer. Buyers don’t engage in routine response behavior when purchasing high-involvement products. Instead, consumers engage in what’s called extended problem solving where they spend a lot of time comparing different aspects such as the features of the products, prices, and warranties.

High-involvement decisions can cause buyers a great deal of cognitive (postpurchase) dissonance (anxiety) if they are unsure about their purchases or if they had a difficult time deciding between two alternatives. Companies that sell high-involvement products are aware that dissonance can be a problem. Frequently, they try to offer consumers a lot of information about their products, including why they are superior to competing brands and how they won’t let the consumer down. Salespeople may be utilized to answer questions and do a lot of customer “hand-holding.”

Allstate’s “You’re in Good Hands” advertisements are designed to convince consumers that the insurance company won’t let them down.

Mike Mozart – Allstate, – CC BY 2.0.

Limited problem solving falls somewhere between low-involvement (routine) and high-involvement (extended problem solving) decisions. Consumers engage in limited problem solving when they already have some information about a good or service but continue to search for a little more information. Assume you need a new backpack for a hiking trip. While you are familiar with backpacks, you know that new features and materials are available since you purchased your last backpack. You’re going to spend some time looking for one that’s decent because you don’t want it to fall apart while you’re traveling and dump everything you’ve packed on a hiking trail. You might do a little research online and come to a decision relatively quickly. You might consider the choices available at your favorite retail outlet but not look at every backpack at every outlet before making a decision. Or you might rely on the advice of a person you know who’s knowledgeable about backpacks. In some way you shorten or limit your involvement and the decision-making process.

Products, such as chewing gum, which may be low-involvement for many consumers, often use advertising such as commercials and sales promotions such as coupons to reach many consumers at once. Companies also try to sell products such as gum in as many locations as possible. Many products that are typically high-involvement such as automobiles may use more personal selling to answer consumers’ questions. Brand names can also be very important regardless of the consumer’s level of purchasing involvement. Consider a low- versus high-involvement decision—say, purchasing a tube of toothpaste versus a new car. You might routinely buy your favorite brand of toothpaste, not thinking much about the purchase (engage in routine response behavior), but not be willing to switch to another brand either. Having a brand you like saves you “search time” and eliminates the evaluation period because you know what you’re getting.

When it comes to the car, you might engage in extensive problem solving but, again, only be willing to consider a certain brand or brands. For example, in the 1970s, American-made cars had such a poor reputation for quality that buyers joked that a car that’s “not Jap [Japanese made] is crap.” The quality of American cars is very good today, but you get the picture. If it’s a high-involvement product you’re purchasing, a good brand name is probably going to be very important to you. That’s why the manufacturers of products that are typically high-involvement decisions can’t become complacent about the value of their brands.

You Try It!

Marketing Copyright © by Kim Donahue is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3.2 Low-Involvement Versus High-Involvement Buying Decisions and the Consumer’s Decision-Making Process

Learning objectives.

- Distinguish between low-involvement and high-involvement buying decisions.

- Understand what the stages of the buying process are and what happens in each stage.

As you have seen, many factors influence a consumer’s behavior. Depending on a consumer’s experience and knowledge, some consumers may be able to make quick purchase decisions and other consumers may need to get information and be more involved in the decision process before making a purchase. The level of involvement reflects how personally important or interested you are in consuming a product and how much information you need to make a decision. The level of involvement in buying decisions may be considered a continuum from decisions that are fairly routine (consumers are not very involved) to decisions that require extensive thought and a high level of involvement. Whether a decision is low, high, or limited, involvement varies by consumer, not by product, although some products such as purchasing a house typically require a high-involvement for all consumers. Consumers with no experience purchasing a product may have more involvement than someone who is replacing a product.

You have probably thought about many products you want or need but never did much more than that. At other times, you’ve probably looked at dozens of products, compared them, and then decided not to purchase any one of them. When you run out of products such as milk or bread that you buy on a regular basis, you may buy the product as soon as you recognize the need because you do not need to search for information or evaluate alternatives. As Nike would put it, you “just do it.” Low-involvement decisions are, however, typically products that are relatively inexpensive and pose a low risk to the buyer if she makes a mistake by purchasing them.

Consumers often engage in routine response behavior when they make low-involvement decisions—that is, they make automatic purchase decisions based on limited information or information they have gathered in the past. For example, if you always order a Diet Coke at lunch, you’re engaging in routine response behavior. You may not even think about other drink options at lunch because your routine is to order a Diet Coke, and you simply do it. Similarly, if you run out of Diet Coke at home, you may buy more without any information search.

Some low-involvement purchases are made with no planning or previous thought. These buying decisions are called impulse buying . While you’re waiting to check out at the grocery store, perhaps you see a magazine with Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt on the cover and buy it on the spot simply because you want it. You might see a roll of tape at a check-out stand and remember you need one or you might see a bag of chips and realize you’re hungry or just want them. These are items that are typically low-involvement decisions. Low-involvement decisions aren’t necessarily products purchased on impulse, although they can be.

By contrast, high-involvement decisions carry a higher risk to buyers if they fail, are complex, and/or have high price tags. A car, a house, and an insurance policy are examples. These items are not purchased often but are relevant and important to the buyer. Buyers don’t engage in routine response behavior when purchasing high-involvement products. Instead, consumers engage in what’s called extended problem solving , where they spend a lot of time comparing different aspects such as the features of the products, prices, and warranties.

High-involvement decisions can cause buyers a great deal of postpurchase dissonance (anxiety) if they are unsure about their purchases or if they had a difficult time deciding between two alternatives. Companies that sell high-involvement products are aware that postpurchase dissonance can be a problem. Frequently, they try to offer consumers a lot of information about their products, including why they are superior to competing brands and how they won’t let the consumer down. Salespeople may be utilized to answer questions and do a lot of customer “hand-holding.”

Allstate’s “You’re in Good Hands” advertisements are designed to convince consumers that the insurance company won’t let them down.

Mike Mozart – Allstate, – CC BY 2.0.

Limited problem solving falls somewhere between low-involvement (routine) and high-involvement (extended problem solving) decisions. Consumers engage in limited problem solving when they already have some information about a good or service but continue to search for a little more information. Assume you need a new backpack for a hiking trip. While you are familiar with backpacks, you know that new features and materials are available since you purchased your last backpack. You’re going to spend some time looking for one that’s decent because you don’t want it to fall apart while you’re traveling and dump everything you’ve packed on a hiking trail. You might do a little research online and come to a decision relatively quickly. You might consider the choices available at your favorite retail outlet but not look at every backpack at every outlet before making a decision. Or you might rely on the advice of a person you know who’s knowledgeable about backpacks. In some way you shorten or limit your involvement and the decision-making process.

Products, such as chewing gum, which may be low-involvement for many consumers often use advertising such as commercials and sales promotions such as coupons to reach many consumers at once. Companies also try to sell products such as gum in as many locations as possible. Many products that are typically high-involvement such as automobiles may use more personal selling to answer consumers’ questions. Brand names can also be very important regardless of the consumer’s level of purchasing involvement. Consider a low- versus high-involvement decision—say, purchasing a tube of toothpaste versus a new car. You might routinely buy your favorite brand of toothpaste, not thinking much about the purchase (engage in routine response behavior), but not be willing to switch to another brand either. Having a brand you like saves you “search time” and eliminates the evaluation period because you know what you’re getting.

When it comes to the car, you might engage in extensive problem solving but, again, only be willing to consider a certain brand or brands. For example, in the 1970s, American-made cars had such a poor reputation for quality that buyers joked that a car that’s “not Jap [Japanese made] is crap.” The quality of American cars is very good today, but you get the picture. If it’s a high-involvement product you’re purchasing, a good brand name is probably going to be very important to you. That’s why the manufacturers of products that are typically high-involvement decisions can’t become complacent about the value of their brands.

1970s American Cars

(click to see video)

Today, Lexus is the automotive brand that experiences the most customer loyalty. For a humorous, tongue-in-cheek look at why the brand reputation of American carmakers suffered in the 1970s, check out this clip.

Stages in the Buying Process

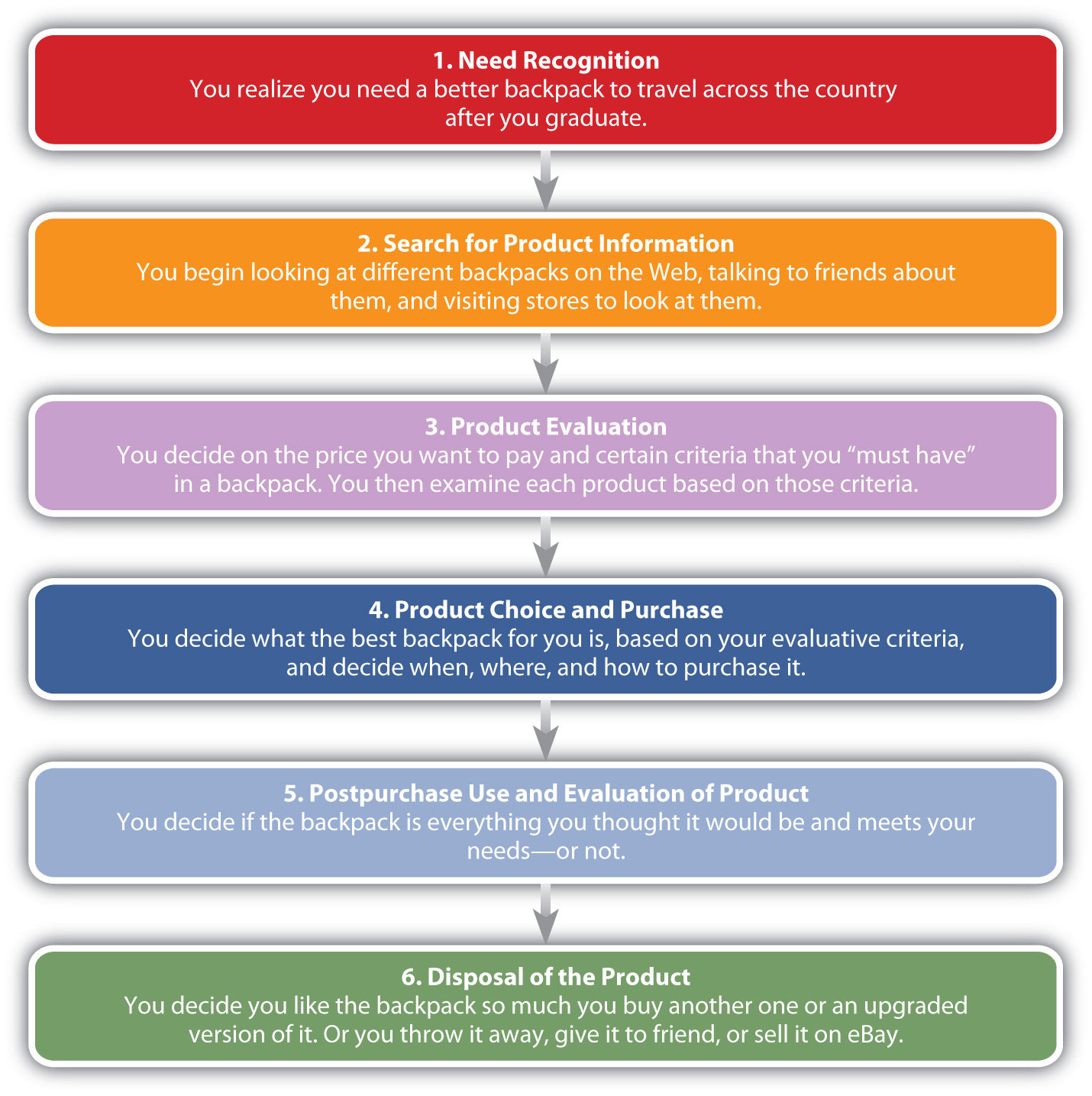

Figure 3.9 “Stages in the Consumer’s Purchasing Process” outlines the buying stages consumers go through. At any given time, you’re probably in a buying stage for a product or service. You’re thinking about the different types of things you want or need to eventually buy, how you are going to find the best ones at the best price, and where and how will you buy them. Meanwhile, there are other products you have already purchased that you’re evaluating. Some might be better than others. Will you discard them, and if so, how? Then what will you buy? Where does that process start?

Figure 3.9 Stages in the Consumer’s Purchasing Process

Stage 1. Need Recognition

You plan to backpack around the country after you graduate and don’t have a particularly good backpack. You realize that you must get a new backpack. You may also be thinking about the job you’ve accepted after graduation and know that you must get a vehicle to commute. Recognizing a need may involve something as simple as running out of bread or milk or realizing that you must get a new backpack or a car after you graduate. Marketers try to show consumers how their products and services add value and help satisfy needs and wants. Do you think it’s a coincidence that Gatorade, Powerade, and other beverage makers locate their machines in gymnasiums so you see them after a long, tiring workout? Previews at movie theaters are another example. How many times have you have heard about a movie and had no interest in it—until you saw the preview? Afterward, you felt like you had to see it.

Stage 2. Search for Information

For products such as milk and bread, you may simply recognize the need, go to the store, and buy more. However, if you are purchasing a car for the first time or need a particular type of backpack, you may need to get information on different alternatives. Maybe you have owned several backpacks and know what you like and don’t like about them. Or there might be a particular brand that you’ve purchased in the past that you liked and want to purchase in the future. This is a great position for the company that owns the brand to be in—something firms strive for. Why? Because it often means you will limit your search and simply buy their brand again.

If what you already know about backpacks doesn’t provide you with enough information, you’ll probably continue to gather information from various sources. Frequently people ask friends, family, and neighbors about their experiences with products. Magazines such as Consumer Reports (considered an objective source of information on many consumer products) or Backpacker Magazine might also help you. Similar information sources are available for learning about different makes and models of cars.

Internet shopping sites such as Amazon.com have become a common source of information about products. Epinions.com is an example of consumer-generated review site. The site offers product ratings, buying tips, and price information. Amazon.com also offers product reviews written by consumers. People prefer “independent” sources such as this when they are looking for product information. However, they also often consult non-neutral sources of information, such advertisements, brochures, company Web sites, and salespeople.

Stage 3. Product Evaluation

Obviously, there are hundreds of different backpacks and cars available. It’s not possible for you to examine all of them. In fact, good salespeople and marketing professionals know that providing you with too many choices can be so overwhelming that you might not buy anything at all. Consequently, you may use choice heuristics or rules of thumb that provide mental shortcuts in the decision-making process. You may also develop evaluative criteria to help you narrow down your choices. Backpacks or cars that meet your initial criteria before the consideration will determine the set of brands you’ll consider for purchase.

Evaluative criteria are certain characteristics that are important to you such as the price of the backpack, the size, the number of compartments, and color. Some of these characteristics are more important than others. For example, the size of the backpack and the price might be more important to you than the color—unless, say, the color is hot pink and you hate pink. You must decide what criteria are most important and how well different alternatives meet the criteria.

Figure 3.10

Osprey backpacks are known for their durability. The company has a special design and quality control center, and Osprey’s salespeople annually take a “canyon testing” trip to see how well the company’s products perform.

melanie innis – break – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Companies want to convince you that the evaluative criteria you are considering reflect the strengths of their products. For example, you might not have thought about the weight or durability of the backpack you want to buy. However, a backpack manufacturer such as Osprey might remind you through magazine ads, packaging information, and its Web site that you should pay attention to these features—features that happen to be key selling points of its backpacks. Automobile manufacturers may have similar models, so don’t be afraid to add criteria to help you evaluate cars in your consideration set.

Stage 4. Product Choice and Purchase

With low-involvement purchases, consumers may go from recognizing a need to purchasing the product. However, for backpacks and cars, you decide which one to purchase after you have evaluated different alternatives. In addition to which backpack or which car, you are probably also making other decisions at this stage, including where and how to purchase the backpack (or car) and on what terms. Maybe the backpack was cheaper at one store than another, but the salesperson there was rude. Or maybe you decide to order online because you’re too busy to go to the mall. Other decisions related to the purchase, particularly those related to big-ticket items, are made at this point. For example, if you’re buying a high-definition television, you might look for a store that will offer you credit or a warranty.

Stage 5. Postpurchase Use and Evaluation

At this point in the process you decide whether the backpack you purchased is everything it was cracked up to be. Hopefully it is. If it’s not, you’re likely to suffer what’s called postpurchase dissonance . You might call it buyer’s remorse . Typically, dissonance occurs when a product or service does not meet your expectations. Consumers are more likely to experience dissonance with products that are relatively expensive and that are purchased infrequently.

You want to feel good about your purchase, but you don’t. You begin to wonder whether you should have waited to get a better price, purchased something else, or gathered more information first. Consumers commonly feel this way, which is a problem for sellers. If you don’t feel good about what you’ve purchased from them, you might return the item and never purchase anything from them again. Or, worse yet, you might tell everyone you know how bad the product was.

Companies do various things to try to prevent buyer’s remorse. For smaller items, they might offer a money back guarantee or they might encourage their salespeople to tell you what a great purchase you made. How many times have you heard a salesperson say, “That outfit looks so great on you!” For larger items, companies might offer a warranty, along with instruction booklets, and a toll-free troubleshooting line to call or they might have a salesperson call you to see if you need help with product. Automobile companies may offer loaner cars when you bring your car in for service.

Companies may also try to set expectations in order to satisfy customers. Service companies such as restaurants do this frequently. Think about when the hostess tells you that your table will be ready in 30 minutes. If they seat you in 15 minutes, you are much happier than if they told you that your table would be ready in 15 minutes, but it took 30 minutes to seat you. Similarly, if a store tells you that your pants will be altered in a week and they are ready in three days, you’ll be much more satisfied than if they said your pants would be ready in three days, yet it took a week before they were ready.

Stage 6. Disposal of the Product

There was a time when neither manufacturers nor consumers thought much about how products got disposed of, so long as people bought them. But that’s changed. How products are being disposed of is becoming extremely important to consumers and society in general. Computers and batteries, which leech chemicals into landfills, are a huge problem. Consumers don’t want to degrade the environment if they don’t have to, and companies are becoming more aware of this fact.

Take for example Crystal Light, a water-based beverage that’s sold in grocery stores. You can buy it in a bottle. However, many people buy a concentrated form of it, put it in reusable pitchers or bottles, and add water. That way, they don’t have to buy and dispose of plastic bottle after plastic bottle, damaging the environment in the process. Windex has done something similar with its window cleaner. Instead of buying new bottles of it all the time, you can purchase a concentrate and add water. You have probably noticed that most grocery stores now sell cloth bags consumers can reuse instead of continually using and discarding of new plastic or paper bags.

Figure 3.11

The hike up to Mount Everest used to be pristine. Now it looks more like this. Who’s responsible? Are consumers or companies responsible, or both?

jqpubliq – Recycling Center Pile – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Other companies are less concerned about conservation than they are about planned obsolescence . Planned obsolescence is a deliberate effort by companies to make their products obsolete, or unusable, after a period of time. The goal is to improve a company’s sales by reducing the amount of time between the repeat purchases consumers make of products. When a software developer introduces a new version of product, it is usually designed to be incompatible with older versions of it. For example, not all the formatting features are the same in Microsoft Word 2007 and 2010. Sometimes documents do not translate properly when opened in the newer version. Consequently, you will be more inclined to upgrade to the new version so you can open all Word documents you receive.

Products that are disposable are another way in which firms have managed to reduce the amount of time between purchases. Disposable lighters are an example. Do you know anyone today that owns a nondisposable lighter? Believe it or not, prior to the 1960s, scarcely anyone could have imagined using a cheap disposable lighter. There are many more disposable products today than there were in years past—including everything from bottled water and individually wrapped snacks to single-use eye drops and cell phones.

Figure 3.12

Disposable lighters came into vogue in the United States in the 1960s. You probably don’t own a cool, nondisposable lighter like one of these, but you don’t have to bother refilling it with lighter fluid either.

Europeana staff photographer – A trench art lighter – public domain.

Key Takeaways

Consumer behavior looks at the many reasons why people buy things and later dispose of them. Consumers go through distinct buying phases when they purchase products: (1) realizing the need or wanting something, (2) searching for information about the item, (3) evaluating different products, (4) choosing a product and purchasing it, (5) using and evaluating the product after the purchase, and (6) disposing of the product. A consumer’s level of involvement is how interested he or she is in buying and consuming a product. Low-involvement products are usually inexpensive and pose a low risk to the buyer if he or she makes a mistake by purchasing them. High-involvement products carry a high risk to the buyer if they fail, are complex, or have high price tags. Limited-involvement products fall somewhere in between.

Review Questions

- How do low-involvement decisions differ from high-involvement decisions in terms of relevance, price, frequency, and the risks their buyers face? Name some products in each category that you’ve recently purchased.

- What stages do people go through in the buying process for high-involvement decisions? How do the stages vary for low-involvement decisions?

- What is postpurchase dissonance and what can companies do to reduce it?

Principles of Marketing Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Individual Consumer Decision Making

29 Consumer Decision Making Process

An organization that wants to be successful must consider buyer behavior when developing the marketing mix. Buyer behavior is the actions people take with regard to buying and using products. Marketers must understand buyer behavior, such as how raising or lowering a price will affect the buyer’s perception of the product and therefore create a fluctuation in sales, or how a specific review on social media can create an entirely new direction for the marketing mix based on the comments (buyer behavior/input) of the target market.

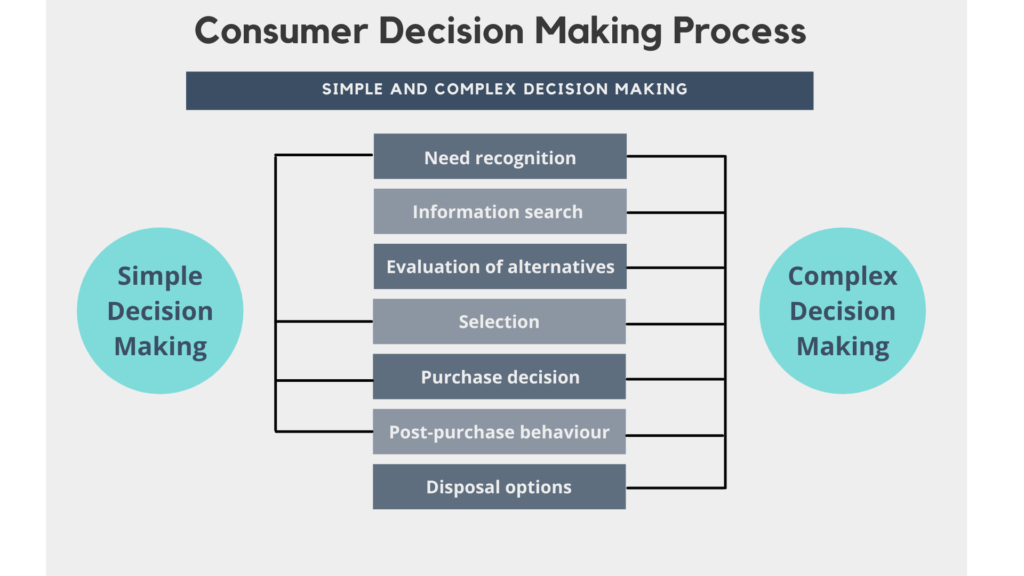

The Consumer Decision Making Process

Once the process is started, a potential buyer can withdraw at any stage of making the actual purchase. The tendency for a person to go through all six stages is likely only in certain buying situations—a first time purchase of a product, for instance, or when buying high priced, long-lasting, infrequently purchased articles. This is referred to as complex decision making .

For many products, the purchasing behavior is a routine affair in which the aroused need is satisfied in a habitual manner by repurchasing the same brand. That is, past reinforcement in learning experiences leads directly to buying, and thus the second and third stages are bypassed. This is called simple decision making .

However, if something changes appreciably (price, product, availability, services), the buyer may re-enter the full decision process and consider alternative brands. Whether complex or simple, the first step is need identification (Assael, 1987).

When Inertia Takes Over

Need Recognition

Whether we act to resolve a particular problem depends upon two factors: (1) the magnitude of the discrepancy between what we have and what we need, and (2) the importance of the problem. A consumer may desire a new Cadillac and own a five-year-old Chevrolet. The discrepancy may be fairly large but relatively unimportant compared to the other problems they face. Conversely, an individual may own a car that is two years old and running very well. Yet, for various reasons, they may consider it extremely important to purchase a car this year. People must resolve these types of conflicts before they can proceed. Otherwise, the buying process for a given product stops at this point, probably in frustration.

Once the problem is recognized it must be defined in such a way that the consumer can actually initiate the action that will bring about a relevant problem solution. Note that, in many cases, problem recognition and problem definition occur simultaneously, such as a consumer running out of toothpaste. Consider the more complicated problem involved with status and image–how we want others to see us. For example, you may know that you are not satisfied with your appearance, but you may not be able to define it any more precisely than that. Consumers will not know where to begin solving their problem until the problem is adequately defined.

Marketers can become involved in the need recognition stage in three ways. First they need to know what problems consumers are facing in order to develop a marketing mix to help solve these problems. This requires that they measure problem recognition. Second, on occasion, marketers want to activate problem recognition. Public service announcements espousing the dangers of cigarette smoking is an example. Weekend and night shop hours are a response of retailers to the consumer problem of limited weekday shopping opportunities. This problem has become particularly important to families with two working adults. Finally, marketers can also shape the definition of the need or problem. If a consumer needs a new coat, do they define the problem as a need for inexpensive covering, a way to stay warm on the coldest days, a garment that will last several years, warm cover that will not attract odd looks from their peers, or an article of clothing that will express their personal sense of style? A salesperson or an ad may shape their answers

Information Search

After a need is recognized, the prospective consumer may seek information to help identify and evaluate alternative products, services, and outlets that will meet that need. Such information can come from family, friends, personal observation, or other sources, such as Consumer Reports, salespeople, or mass media. The promotional component of the marketers offering is aimed at providing information to assist the consumer in their problem solving process. In some cases, the consumer already has the needed information based on past purchasing and consumption experience. Bad experiences and lack of satisfaction can destroy repeat purchases. The consumer with a need for tires may look for information in the local newspaper or ask friends for recommendation. If they have bought tires before and was satisfied, they may go to the same dealer and buy the same brand.

Information search can also identify new needs. As a tire shopper looks for information, they may decide that the tires are not the real problem, that the need is for a new car. At this point, the perceived need may change triggering a new informational search. Information search involves mental as well as the physical activities that consumers must perform in order to make decisions and accomplish desired goals in the marketplace. It takes time, energy, money, and can often involve foregoing more desirable activities. The benefits of information search, however, can outweigh the costs. For example, engaging in a thorough information search may save money, improve quality of selection, or reduce risks. The Internet is a valuable information source.

Evaluation of Alternatives

After information is secured and processed, alternative products, services, and outlets are identified as viable options. The consumer evaluates these alternatives , and, if financially and psychologically able, makes a choice. The criteria used in evaluation varies from consumer to consumer just as the needs and information sources vary. One consumer may consider price most important while another puts more weight (importance) upon quality or convenience.

Using the ‘Rule of Thumb’

Consumers don’t have the time or desire to ponder endlessly about every purchase! Fortunately for us, heuristics , also described as shortcuts or mental “rules of thumb”, help us make decisions quickly and painlessly. Heuristics are especially important to draw on when we are faced with choosing among products in a category where we don’t see huge differences or if the outcome isn’t ‘do or die’.

Heuristics are helpful sets of rules that simplify the decision-making process by making it quick and easy for consumers.

Common Heuristics in Consumer Decision Making

- Save the most money: Many people follow a rule like, “I’ll buy the lowest-priced choice so that I spend the least money right now.” Using this heuristic means you don’t need to look beyond the price tag to make a decision. Wal-Mart built a retailing empire by pleasing consumers who follow this rule.

- You get what you pay for: Some consumers might use the opposite heuristic of saving the most money and instead follow a rule such as: “I’ll buy the more expensive product because higher price means better quality.” These consumers are influenced by advertisements alluding to exclusivity, quality, and uncompromising performance.

- Stich to the tried and true: Brand loyalty also simplifies the decision-making process because we buy the brand that we’ve always bought before. therefore, we don’t need to spend more time and effort on the decision. Advertising plays a critical role in creating brand loyalty. In a study of the market leaders in thirty product categories, 27 of the brands that were #1 in 1930 were still at the top over 50 years later (Stevesnson, 1988)! A well known brand name is a powerful heuristic .

- National pride: Consumers who select brands because they represent their own culture and country of origin are making decision based on ethnocentrism . Ethnocentric consumers are said to perceive their own culture or country’s goods as being superior to others’. Ethnocentrism can behave as both a stereotype and a type of heuristic for consumers who are quick to generalize and judge brands based on their country of origin.

- Visual cues: Consumers may also rely on visual cues represented in product and packaging design. Visual cues may include the colour of the brand or product or deeper beliefs that they have developed about the brand. For example, if brands claim to support sustainability and climate activism, consumers want to believe these to be true. Visual cues such as green design and neutral-coloured packaging that appears to be made of recycled materials play into consumers’ heuristics .

The search for alternatives and the methods used in the search are influenced by such factors as: (a) time and money costs; (b) how much information the consumer already has; (c) the amount of the perceived risk if a wrong selection is made; and (d) the consumer’s predisposition toward particular choices as influenced by the attitude of the individual toward choice behaviour. That is, there are individuals who find the selection process to be difficult and disturbing. For these people there is a tendency to keep the number of alternatives to a minimum, even if they have not gone through an extensive information search to find that their alternatives appear to be the very best. On the other hand, there are individuals who feel it necessary to collect a long list of alternatives. This tendency can appreciably slow down the decision-making function.

Consumer Evaluations Made Easier

The evaluation of alternatives often involves consumers drawing on their evoke, inept, and insert sets to help them in the decision making process.

The brands and products that consumers compare—their evoked set – represent the alternatives being considered by consumers during the problem-solving process. Sometimes known as a “consideration” set, the evoked set tends to be small relative to the total number of options available. When a consumer commits significant time to the comparative process and reviews price, warranties, terms and condition of sale and other features it is said that they are involved in extended problem solving. Unlike routine problem solving, extended or extensive problem solving comprises external research and the evaluation of alternatives. Whereas, routine problem solving is low-involvement, inexpensive, and has limited risk if purchased, extended problem solving justifies the additional effort with a high-priced or scarce product, service, or benefit (e.g., the purchase of a car). Likewise, consumers use extensive problem solving for infrequently purchased, expensive, high-risk, or new goods or services.

As opposed to the evoked set, a consumer’s inept set represent those brands that they would not given any consideration too. For a consumer who is shopping around for an electric vehicle, for example, they would not even remotely consider gas-guzzling vehicles like large SUVs.

The inert set represents those brands or products a consumer is aware of, but is indifferent to and doesn’t consider them either desirable or relevant enough to be among the evoke set. Marketers have an opportunity here to position their brands appropriately so consumers move these items from their insert to evoke set when evaluation alternatives.

The selection of an alternative, in many cases, will require additional evaluation. For example, a consumer may select a favorite brand and go to a convenient outlet to make a purchase. Upon arrival at the dealer, the consumer finds that the desired brand is out-of-stock. At this point, additional evaluation is needed to decide whether to wait until the product comes in, accept a substitute, or go to another outlet. The selection and evaluation phases of consumer problem solving are closely related and often run sequentially, with outlet selection influencing product evaluation, or product selection influencing outlet evaluation.

While many consumers would agree that choice is a good thing, there is such a thing as “too much choice” that inhibits the consumer decision making process. Consumer hyperchoice is a term used to describe purchasing situations that involve an excess of choice thus making selection for difficult for consumers. Dr. Sheena Iyengar studies consumer choice and collects data that supports the concept of consumer hyperchoice. In one of her studies, she put out jars of jam in a grocery store for shoppers to sample, with the intention to influence purchases. Dr. Iyengar discovered that when a fewer number of jam samples were provided to shoppers, more purchases were made. But when a large number of jam samples were set out, fewer purchases were made (Green, 2010). As it turns out, “more is less” when it comes to the selection process.

The Purchase Decision

After much searching and evaluating, or perhaps very little, consumers at some point have to decide whether they are going to buy.

Anything marketers can do to simplify purchasing will be attractive to buyers. This may include minimal clicks to online checkout; short wait times in line; and simplified payment options. When it comes to advertising marketers could also suggest the best size for a particular use, or the right wine to drink with a particular food. Sometimes several decision situations can be combined and marketed as one package. For example, travel agents often package travel tours with flight and hotel reservations.

To do a better marketing job at this stage of the buying process, a seller needs to know answers to many questions about consumers’ shopping behaviour. For instance, how much effort is the consumer willing to spend in shopping for the product? What factors influence when the consumer will actually purchase? Are there any conditions that would prohibit or delay purchase? Providing basic product, price, and location information through labels, advertising, personal selling, and public relations is an obvious starting point. Product sampling, coupons, and rebates may also provide an extra incentive to buy.

Actually determining how a consumer goes through the decision-making process is a difficult research task.

Post-Purchase Behaviour

All the behaviour determinants and the steps of the buying process up to this point are operative before or during the time a purchase is made. However, a consumer’s feelings and evaluations after the sale are also significant to a marketer, because they can influence repeat sales and also influence what the customer tells others about the product or brand.

Keeping the customer happy is what marketing is all about. Nevertheless, consumers typically experience some post-purchase anxiety after all but the most routine and inexpensive purchases. This anxiety reflects a phenomenon called cognitive dissonance . According to this theory, people strive for consistency among their cognitions (knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, values). When there are inconsistencies, dissonance exists, which people will try to eliminate. In some cases, the consumer makes the decision to buy a particular brand already aware of dissonant elements. In other instances, dissonance is aroused by disturbing information that is received after the purchase. The marketer may take specific steps to reduce post-purchase dissonance. Advertising that stresses the many positive attributes or confirms the popularity of the product can be helpful. Providing personal reinforcement has proven effective with big-ticket items such as automobiles and major appliances. Salespeople in these areas may send cards or may even make personal calls in order to reassure customers about their purchase.

Media Attributions

- The graphic of the “Consumer Decision Making Process” by Niosi, A. (2021) is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA and is adapted from Introduction to Business by Rice University.

Text Attributions

- The sections under the “Consumer Decision Making Process,” “Need Recognition” (edited), “Information Search,” “Evaluation of Alternatives”; the first paragraph under the section “Selection”; the section under “Purchase Decision”; and, the section under “Post-Purchase Behaviour” are adapted from Introducing Marketing [PDF] by John Burnett which is licensed under CC BY 3.0 .

- The opening paragraph and the image of the Consumer Decision Making Process is adapted from Introduction to Business by Rice University which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

- The section under “Using the ‘Rule of Thumb'” is adapted (and edited) from Launch! Advertising and Promotion in Real Time [PDF] by Saylor Academy which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 .

Assael, H. (1987). Consumer Behavior and Marketing Action (3rd ed.), 84. Boston: Kent Publishing.

Green, P. (2010, March 17). An Expert on Choice Chooses. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/18/garden/18choice.html.

Consumer purchases made when a (new) need is identified and a consumer engages in a more rigorous evaluation, research, and alternative assessment process before satisfying the unmet need.

Consumer purchases made when a need is identified and a habitual ("routine") purchase is made to satisfy that need.

Purchasing decisions made out of habit.

The first stage of the Consumer Decision Making Process, need recognition takes place when a consumer identifies an unmet need.

The second stage of the Consumer Decision Making Process, information search takes place when a consumer seeks relative information that will help them identify and evaluate alternatives before deciding on the final purchase decision.

The third stage of the Consumer Decision Making Process, the evaluation of alternatives takes place when a consumer establishes criteria to evaluate the most viable purchasing option.

Also known as "mental shortcuts" or "rules of thumb", heuristics help consumers by simplifying the decision-making process.

A small set of "go-to" brands that consumers will consider as they evaluate the alternatives available to them before making a purchasing decision.

The brands a consumer would not pay any attention to during the evaluation of alternatives process.

The brands a consumer is aware of but indifferent to, when evaluating alternatives in the consumer decision making process. The consumer may deem these brands irrelevant and will therefore exclude them from any extensive evaluation or consideration.

A term that describes a purchasing situation in which a consumer is faced with an excess of choice that makes decision making difficult or nearly impossible.

A type of cognitive inconsistency, this term describes the discomfort consumers may feel when their beliefs, values, attitudes, or perceptions are inconsistent or contradictory to their original belief or understanding. Consumers with cognitive dissonance related to a purchasing decision will often seek to resolve this internal turmoil they are experiencing by returning the product or finding a way to justify it and minimizing their sense of buyer's remorse.

Introduction to Consumer Behaviour Copyright © 2021 by Andrea Niosi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Consumer Motivation and Involvement

15 Involvement Levels

Depending on a consumer’s experience and knowledge, some consumers may be able to make quick purchase decisions and other consumers may need to get information and be more involved in the decision process before making a purchase. The level of involvement reflects how personally important or interested you are in consuming a product and how much information you need to make a decision. The level of involvement in buying decisions may be considered a continuum from decisions that are fairly routine (consumers are not very involved) to decisions that require extensive thought and a high level of involvement. Whether a decision is low, high, or limited, involvement varies by consumer, not by product.

Low Involvement Consumer Decision Making

At some point in your life you may have considered products you want to own (e.g. luxury or novelty items), but like many of us, you probably didn’t do much more than ponder their relevance or suitability to your life. At other times, you’ve probably looked at dozens of products, compared them, and then decided not to purchase any one of them. When you run out of products such as milk or bread that you buy on a regular basis, you may buy the product as soon as you recognize the need because you do not need to search for information or evaluate alternatives . As Nike would put it, you “just do it.” Low-involvement decisions are, however, typically products that are relatively inexpensive and pose a low risk to the buyer if a mistake is made in purchasing them.

Consumers often engage in routine response behaviour when they make low-involvement decisions — that is, they make automatic purchase decisions based on limited information or information they have gathered in the past. For example, if you always order a Diet Coke at lunch, you’re engaging in routine response behaviour. You may not even think about other drink options at lunch because your routine is to order a Diet Coke, and you simply do it. Similarly, if you run out of Diet Coke at home, you may buy more without any information search.

Some low-involvement purchases are made with no planning or previous thought. These buying decisions are called impulse buying . While you’re waiting to check out at the grocery store, perhaps you see a magazine with a notable celebrity on the cover and buy it on the spot simply because you want it. You might see a roll of tape at a check-out stand and remember you need one or you might see a bag of chips and realize you’re hungry or just want them. These are items that are typically low-involvement decisions. Low involvement decisions aren’t necessarily products purchased on impulse, although they can be.

High Involvement Consumer Decision Making

By contrast, high-involvement decisions carry a higher risk to buyers if they fail. These are often more complex purchases that may carry a high price tag, such as a house, a car, or an insurance policy. These items are not purchased often but are relevant and important to the buyer. Buyers don’t engage in routine response behaviour when purchasing high-involvement products. Instead, consumers engage in what’s called extended problem solving where they spend a lot of time comparing different aspects such as the features of the products, prices, and warranties.

High-involvement decisions can cause buyers a great deal of post-purchase dissonance, also known as cognitive dissonance which is a form of anxiety consumers experience if they are unsure about their purchases or if they had a difficult time deciding between two alternatives. Companies that sell high-involvement products are aware that post purchase dissonance can be a problem. Frequently, marketers try to offer consumers a lot of supporting information about their products, including why they are superior to competing brands and why the consumer won’t be disappointed with their purchase afterwards. Salespeople play a critical role in answering consumer questions and providing extensive support during and after the purchasing stage.

Limited Problem Solving

Limited problem solving falls somewhere between low-involvement (routine) and high-involvement (extended problem solving) decisions. Consumers engage in limited problem solving when they already have some information about a good or service but continue to search for a little more information. Assume you need a new backpack for a hiking trip. While you are familiar with backpacks, you know that new features and materials are available since you purchased your last backpack. You’re going to spend some time looking for one that’s decent because you don’t want it to fall apart while you’re traveling and dump everything you’ve packed on a hiking trail. You might do a little research online and come to a decision relatively quickly. You might consider the choices available at your favourite retail outlet but not look at every backpack at every outlet before making a decision. Or you might rely on the advice of a person you know who’s knowledgeable about backpacks. In some way you shorten or limit your involvement and the decision-making process.

Distinguishing Between Low Involvement and High Involvement

| Low Involvement | High Involvement | |

|---|---|---|

| Product | Toilet paper Hand soap Light Bulbs Chewing gum Photo copy paper | Wedding dress Luxury vehicle Cruise/Vacation Designer sneakers Vacation property |

| Place | Wide distribution | Exclusive/Limited distribution |

| Price | Competitive/Low | Luxury/High |

| Promotion | Push marketing; mass advertising; TV; radio; billboards; coupons; sales promotions | Pull marketing; personal selling; email marketing; WOM; personalized communications |

| Information Search | None/Minimal | Extensive |

| Evaluation of Alternatives | None/Minimal | Considerable/Extensive |

| Purchasing Behaviour | Routine-response; automatic; impulsive | Extended problem-solving |

| Purchasing Frequency | High/Regular basis | Low-seldom/Special occasion |

Products, such as chewing gum, which may be low-involvement for many consumers often use advertising such as commercials and sales promotions such as coupons to reach many consumers at once. Companies also try to sell products such as gum in as many locations as possible. Many products that are typically high-involvement such as automobiles may use more personal selling to answer consumers’ questions. Brand names can also be very important regardless of the consumer’s level of purchasing involvement. Consider a low-versus high-involvement decision — say, purchasing a tube of toothpaste versus a new car. You might routinely buy your favorite brand of toothpaste, not thinking much about the purchase (engage in routine response behaviour), but not be willing to switch to another brand either. Having a brand you like saves you “search time” and eliminates the evaluation period because you know what you’re getting.

When it comes to the car, you might engage in extensive problem solving but, again, only be willing to consider a certain brand or brands (e.g. your evoke set for automobiles). For example, in the 1970s, American-made cars had such a poor reputation for quality that buyers joked that a car that’s not foreign is “crap.” The quality of American cars is very good today, but you get the picture. If it’s a high-involvement product you’re purchasing, a good brand name is probably going to be very important to you. That’s why the manufacturers of products that are typically high-involvement decisions can’t become complacent about the value of their brands.

Ways to Increase Involvement Levels

Involvement levels – whether they are low, high, or limited – vary by consumer and less so by product. A consumer’s involvement with a particular product will depend on their experience and knowledge, as well as their general approach to gathering information before making purchasing decisions. In a highly competitive marketplace, however, brands are always vying for consumer preference, loyalty, and affirmation. For this reason, many brands will engage in marketing strategies to increase exposure, attention, and relevance; in other words, brands are constantly seeking ways to motivate consumers with the intention to increase consumer involvement with their products and services.

Some of the different ways marketers increase consumer involvement are: customization; engagement; incentives; appealing to hedonic needs; creating purpose; and, representation.

1. Customization

With Share a Coke, Coca-Cola made a global mass customization implementation that worked for them. The company was able to put the labels on millions of bottles in order to get consumers to notice the changes to the coke bottle in the aisle. People also felt a kinship and moment of recognition once they spotted their names or a friend’s name. Simultaneously this personalization also worked because of the printing equipment that could make it happen and there are not that many first names to begin with. These factors lead the brand to be able to roll this out globally ( Mass Customization #12 , 2017).

2. Engagement

Have you ever heard the expression, “content is king”? Without a doubt, engaging, memorable, and unique marketing content has a lasting impact on consumers. The marketing landscape is a noisy one, polluted with an infinite number of brands advertising extensively to consumers, vying for a fraction of our attention. Savvy marketers recognize the importance of sparking just enough consumer interest so they become motivated to take notice and process their marketing messages. Marketers who create content (that isn’t just about sales and promotion) that inspires, delights, and even serves an audience’s needs are unlocking the secret to engagement. And engagement leads to loyalty.

There is no trick to content marketing, but the brands who do it well know that stepping away – far away – from the usual sales and promotion lines is critical. While content marketing is an effective way to increase sales, grow a brand, and create loyalty, authenticity is at its core.

Bodyform and Old Spice are two brands who very cleverly applied just the right amount of self-deprecating humour to their content marketing that not only engaged consumers, but had them begging for more!

Content as a Key Driver to Consumer Engagement

Engaging customers through content might involve a two-way conversation online, or an entire campaign designed around a single customer comment.

In 2012, Richard Neill posted a message to Bodyform’s Facebook page calling out the brand for lying to and deceiving its customers and audiences for years. Richard went on to say that Bodyform’s advertisements failed to truly depict any sense of reality and that in fact he felt set up by the brand to experience a huge fall. Bodyform, or as Richard addressed the company, “you crafty bugger,” is a UK company that produces and sells feminine protection products to menstruating girls and women (Bodyform, n.d.). Little did Richard know that when he posted his humorous rant to Bodyform that the company would respond by creating a video speaking directly at Richard and coming “clean” on all their deceitful attempts to make having period look like fun. When Bodyform’s video went viral, a brand that would have otherwise continued to blend into the background, captured the attention of a global audience.

Xavier Izaguirre says that, “[a]udience involvement is the process and act of actively involving your target audience in your communication mix, in order to increase their engagement with your message as well as advocacy to your brand.” Bodyform gained global recognition by turning one person’s rant into a viral publicity sensation (even though Richard was not the customer in this case).

Despite being a household name, in the years leading up to Old Spice’s infamous “The Man Your Man Should Smell Like” campaign, sales were flat and the brand had failed to strike a chord in a new generation of consumers. Ad experts at Wieden + Kennedy produced a single 30-second ad (featuring a shirtless and self-deprecating Isaiah Mustafa) that played around the time of the 2010 Super Bowl game. While the ad quickly gained notoriety on YouTube, it was the now infamous, “ Response Campaign ” that made the campaign a leader of its time in audience engagement.

3. Incentives

Customer loyalty and reward programs successfully motivate consumers in the decision making process and reinforce purchasing behaviours ( a feature of instrumental conditioning ). The rationale for loyalty and rewards programs is clear: the cost of acquiring a new customer runs five to 25 times more than selling to an existing one and existing customers spend 67 per cent more than new customers (Bernazzani, n.d.). From the customer perspective, simple and practical reward programs such as Beauty Insider – a point-accumulation model used by Sephora – provides strong incentive for customer loyalty (Bernazzani, n.d.).

4. Appealing to Hedonic Needs

A particularly strong way to motivate consumers to increase involvement levels with a product or service is to appeal to their hedonic needs. Consumers seek to satisfy their need for fun, pleasure, and enjoyment through luxurious and rare purchases. In these cases, consumers are less likely to be price sensitive (“it’s a treat”) and more likely to spend greater processing time on the marketing messages they are presented with when a brand appeals to their greatest desires instead of their basic necessities.

5. Creating Purpose

Millennial and Digital Native consumers are profoundly different than those who came before them. Brands, particularly in the consumer goods category, who demonstrate (and uphold) a commitment to sustainability grow at a faster rate (4 per cent) than those who do not (1 per cent) (“Consumer-Goods…”, 2015). In a 2015 poll, 30,000 consumers were asked how much the environment, packaging, price, marketing, and organic or health and wellness claims had on their consumer-goods’ purchase decisions, and to no surprise, 66 per cent said they would be willing to pay more for sustainable brands. (Nielsen, 2015). A rising trend and important factor to consider in evaluating consumer involvement levels and ways to increase them. So while cruelty-free, fair trade, and locally-sourced may all seem like buzz words to some, they are non-negotiable decision-making factors to a large and growing consumer market.

6. Representation

Celebrity endorsement can have a profound impact on consumers’ overall attitude towards a brand. Consumers who might otherwise have a “neutral” attitude towards a brand (neither positive nor negative) may be more noticed to take notice of a brand’s messages and stimuli if a celebrity they admire is the face of the brand.

When sportswear and sneaker brand Puma signed Rihanna on to not just endorse the brand but design an entire collection, sales soared in all the regions and the brand enjoyed a new “revival” in the U.S. where Under Armour and Nike had been making significant gains (“Rihanna Designs…”, 2017). “Rihanna’s relationship with us makes the brand actual and hot again with young consumers,” said chief executive Bjorn Gulden (“Rihanna Designs…”, 2017).

Media Attributions

- The image of two different coloured sneakers is by Raka Rachgo on Unsplash .

- The image of a coffee card in a wallet is by Rebecca Aldama on Unsplash .

- The image of an island resort in tropical destination is by Ishan @seefromthesky on Unsplash .

- The image of a stack of glossy magazine covers is by Charisse Kenion on Unsplash .

Text Attributions

- The introductory paragraph; sections on “Low Involvement Consumer Decision Making”, “High Involvement Consumer Decision Making”, and “Limited Problem Solving” are adapted from Principles of Marketing which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

About Us . (n.d.). Body Form. Retrieved February 2, 2019, from https://www.bodyform.co.uk/about-us/.

Kalamut, A. (2010, August 18). Old Spice Video “Case Study” . YouTube [Video]. https://youtu.be/Kg0booW1uOQ.

Bernazzani, S. (n.d.). Customer Loyalty: The Ultimate Guide [Blog post]. https://blog.hubspot.com/service/customer-loyalty.

Bodyform Channel. (2012, October 16). Bodyform Responds: The Truth . YouTube [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bpy75q2DDow&feature=youtu.be.

Consumer-Goods’ Brands That Demonstrate Commitment to Sustainability Outperform Those That Don’t. (2015, October 12). Nielsen [Press Release]. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/press-room/2015/consumer-goods-brands-that-demonstrate-commitment-to-sustainability-outperform.html.

Curtin, M. (2018, March 30). 73 Per Cent of Millennials are Willing to Spend More Money on This 1 Type of Product . Inc. https://www.inc.com/melanie-curtin/73-percent-of-millennials-are-willing-to-spend-more-money-on-this-1-type-of-product.html.

Izaguirre, X. (2012, October 17). How are brands using audience involvement to increase reach and engagement? EConsultancy. https://econsultancy.com/how-are-brands-using-audience-involvement-to-increase-reach-and-engagement/.

Rihanna Designs Help Lift Puma Sportswear Sales . (2017, October 24). Reuters. https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/news-analysis/rihanna-designs-help-lift-puma-sportswear-sales.

Tarver, E. (2018, October 20). Why the ‘Share a Coke’ Campaign Is So Successful . Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/articles/markets/100715/what-makes-share-coke-campaign-so-successful.asp.

Low involvement decision making typically reflects when a consumer who has a low level of interest and attachment to an item. These items may be relatively inexpensive, pose low risk (can be exchanged, returned, or replaced easily), and not require research or comparison shopping.

This concept describes when consumers make low-involvement decisions that are "automatic" in nature and reflect a limited amount of information the consumer has gathered in the past.

A type of purchase that is made with no previous planning or thought.

High involvement decision making typically reflects when a consumer who has a high degree of interest and attachment to an item. These items may be relatively expensive, pose a high risk to the consumer (can't be exchanged or refunded easily or at all), and require some degree of research or comparison shopping.

Also known as "consumer remorse" or "consumer guilt", this is an unsettling feeling consumers may experience post-purchase if they feel their actions are not aligned with their needs.

Consumers engage in limited problem solving when they have some information about an item, but continue to gather more information to inform their purchasing decision. This falls between "low" and "high" involvement on the involvement continuum.

Introduction to Consumer Behaviour Copyright © by Andrea Niosi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Join the AMA

- Find learning by topic

- Free learning resources for members

- Credentialed Learning

- Training for teams

- Why learn with the AMA?

- Marketing News

- Academic Journals

- Guides & eBooks

- Marketing Job Board

- Academic Job Board

- AMA Foundation

- Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

- Collegiate Resources

- Awards and Scholarships

- Sponsorship Opportunities

- Strategic Partnerships

We noticed that you are using Internet Explorer 11 or older that is not support any longer. Please consider using an alternative such as Microsoft Edge, Chrome, or Firefox.

A Definitive Guide to Problem-Solving

There’s no one way to solve a problem—in fact, you should avoid using canned approaches. But there are ideas, steps, plans and questions that problem-solving professionals have found useful for decades.

Finding and defining problems.

Three days after graduating high school, Fred Nickols joined the U.S. Navy and began solving problems. He learned a technique called fault isolation that let him find and fix problems with radars, computers and weaponry. During one gunfire support mission, he found that a gun was shooting bullets 3,000 yards beyond where the military thought capable—Nickols wrote up the problem and the weapons system was modified to show its more accurate, longer range. “That was a nice beneficial side effect,” he says with a chuckle.

After leaving the Navy, Nickols worked for 40 years as an executive and business consultant and found that business problems could be grouped into the same three categories as they were in the Navy. There are find-and-fix problems, like the gun that shot too far. These problems are easily definable and have definite solutions. There are problems where businesses simply want to improve. “Nothing’s broke, but you want much better than what you have,” Nickols says. Then there are the problems where businesses have a void to fill and must create something new. “You’re starting from scratch,” he says. “You don’t have anything in place, but you’ve got to put something in place to create the results you want.

“You’ve got to decide up front: Are you trying to find something and fix it, are you trying to improve what you have or are you building something from scratch?” Nickols says.

A caveat to finding and defining problems is the distinct difference between problems that have a single solution and those that don’t, according to M. Neil Browne , a professor at Bowling Green State University’s College of Business and co-author of Asking the Right Questions . Single-solution problems—“efficiency questions,” Browne calls them—will have one answer that is clearly better than the rest. If shipping products has become too expensive, for example, there’s likely one answer that works best to reduce costs. But in more complex problems—“critical thinking problems,” Browne says—the best answer depends on perspective.

“If a firm is having difficulty and the marketing director says, ‘You should spend more money providing incentives to our sales staff,’ but one of the production engineers says, ‘You could save more money by spending more on automated equipment,’ that’s not going to be something that every reasonable person in the room is going to agree with,” Browne says, “because their assumptions are different.”

Consider critical-thinking problems this way: Your back hurts, so you make appointments with an exercise physiologist, an orthopedic surgeon and a holistic health guru. Each will use knowledge of their specialty to give you a different solution for your back pain. They could debate for hours without reaching a single conclusion. As psychologist Abraham Maslow quipped in 1966: “I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.”

This initial stage of problem-solving—defining the problem—is where most businesses stumble, says Andrea Bassi , founder and CEO of KnowlEdge Srl, associate professor of system dynamics modelling at Stellenbosch University and co-author of Tackling Complexity . There are many ways companies can misidentify problems, but Bassi says that their biggest mistake often occurs when they define a problem by its symptoms instead of its causes, main effects and true drivers. Addressing the symptoms can help eliminate short-term issues, Bassi says, but it likely won’t solve the long-standing problems and could create more.

associate professor of system dynamics modelling at Stellenbosch University and co-author of Tackling Complexity . There are many ways companies can misidentify problems, but Bassi says that their biggest mistake often occurs when they define a problem by its symptoms instead of its causes, main effects and true drivers. Addressing the symptoms can help eliminate short-term issues, Bassi says, but it likely won’t solve the long-standing problems and could create more.

Most problems emerge from within organizations rather than originating from the outside, Bassi says. “We tend to think that things are imposed onto us, and we need to find solutions, but in fact, we’re normally creating problems with our behavior,” he says. “If you use a systemic approach, you can figure out more lasting and more effective solutions.”

But before moving into a systemic approach, it’s important to go beyond the surface of what the problem could be and find out exactly what it is. In this stage, Nickols says that companies must avoid locking in on one solution by asking many questions: What functions do you want to be able to perform, and who must be able to perform them? What kind of data structure do you want in the system?

“Over time, the picture of the system that you’re building will begin to emerge and finally crystallize,” Nickols says.

But the questions should never stop, even if the problem crystalizes. Questions, according to Browne, are likely the most important part of the next step: Creating the team that will solve the problem.

Building the Problem-Solving Team

In 2009, nonprofit Prize4Life posted a problem to InnoCentive, an open-innovation and crowdsourcing platform. Prize4Life wanted to find the biomarker for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), a degenerative disease that seemingly comes out of nowhere. Prize4Life offered problem-solvers $1 million to find the ALS biomarker; within two years , Dr. Seward Rutkove of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston found it. Six years later, Prize4Life used the pool of more than 1,000 problem-solvers on InnoCentive to find ways to predict disease progression in ALS patients, awarding problem-solvers smaller cash prizes.

InnoCentive’s crowdsourcing system brings in problem-solvers from outside the organization, granting access to the eyes, brains and problem-solving abilities of people who may have never worked in medical research. Jon Fredrickson, chief innovation officer at InnoCentive, says that using outsiders allows companies to look at a problem differently than they would by assembling a team from inside.

But what if a company has access only to its own employees?

Companies should form a problem-solving team where each member brings a different perspective, writes Antonio E. Weiss in his book Key Business Solutions: Essential Problem-Solving Tools and Techniques That Every Manager Needs to Know . Each team member must feel comfortable giving feedback to one another: “Feedback is just as much about giving constructive praise as constructive criticism,” he writes. “And feedback can be given by any team member, no matter how junior or inexperienced.” Weiss writes that all team stakeholders need to understand what the problem is, what a good solution looks like, when the solution needs to be delivered and the context surrounding the problem.

Glenn Llopis , a business management consultant and author of The Innovation Mentality: Six Strategies to Disrupt the Status Quo and Reinvent the Way We Work , says that cultivating an environment where feedback is acceptable takes something organizations often lack: vulnerability.

“Very few people have all the answers, so you have to be able to create an environment of vulnerability and inclusivity within your organization for people to provide constant feedback and recommendations, regardless of hierarchy or rank,” Llopis says. “There are so many opportunities that are ignored because the individual doesn’t feel comfortable revealing them.”

Beyond stifling feedback, companies often involve too many high-level employees and not enough employees who deal with the problem’s issues every day, Bassi says. “They may not have enough knowledge of what’s going on,” he says of high-level personnel. “They miss what could be the root causes of a problem in the production chain. They may miss some of the considerations that actually drive them to find a lasting solution.”

To avoid missing insights, Bassi says that organizations should find a mix of knowledge from technical and managerial points of view. “You need someone with the vision of the higher level in a management position and those that work more on the technical level and see how the work is performed on the ground,” he says.

Nickols, the Navy serviceman who went on to solve problems his entire career, says that he has a few basic principles for forming a problem-solving team. First, there must be someone in a position of authority. In addition, he agrees with Bassi: There must be people who know the system well. “I don’t want newbies and trainees,” he says. “I want people who have the respect of their peers.” Nickols says that the team also needs a sponsor, someone who will give the project authority and support behind the scenes and get all departments to buy into the team’s work. Finally, he suggests adding a “straw boss,” someone who ensures the team has everything it needs.

In the book The Moment of Clarity: Using the Human Sciences to Solve Your Toughest Business Problems , authors Christian Madsbjerg and Mikkel B. Rasmussen suggest that businesses frame problems in a way that allows employees to be curious. “Reframe the problem as a phenomenon,” the authors write. “If your team can create a shared understanding of the problem and agree on what you and the rest of the team don’t know, it is much easier to accept new ways of solving the problem.”

In Brian Tracy’s book Creativity & Problem Solving , he suggests that teams hold both “mindstorming” and brainstorming sessions. In mindstorming sessions, each team member takes a sheet of paper with the problem or goal at the top, then writes 20 answers using the first-person voice and action verbs. The question, “What can we do to double our sales and profitability in the next 24 months?” could be answered with ideas like, “We hire and train 22 new sales people.” In brainstorming sessions, Tracy widens the scope by including four to seven team members and having them generate ideas together for 30 minutes, staying positive and saving the criticism of ideas for after the meeting.

Throughout the problem-solving process, Browne says, teams—especially those working on critical-thinking problems—should focus on a series of evidence-focused questions, such as “Do you have any financial interest in the answer to this question?” and “How much experience do you have in using this evidence?” Although many people may find this kind of critical thinking aggressive, Browne says that questions foster a better understanding of what team members know and why they believe their solution would work best. Team members should ask questions respectfully, with curiosity and with willingness to understand new information.

After all the ideas, questions and evidence are on the table, Browne says that teams must quickly decide on a solution. “We can’t analyze this thing the rest of our lives,” he says. “We have to make decisions in a business environment more quickly than people typically do.”

At this point, digging into the problem through a map and problem statement will be useful.

Making a Map

After the problem-solving team pours out its ideas and questions, the organization may realize that there is more than one right answer and many potential side effects. This is why everything—ideas, questions, potential side effects—should be recorded and arranged when digging into the problem. The end goal is to have a problem statement, a map of the company’s problems.