You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Gr. 11 History T3 W4: The Rise of Afrikaner Nationalism

The Rise of Afrikaner Nationalism - Economic affirmative action in the 1920's and 1930's

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.

Home Contact us Terms of Use Privacy Policy Western Cape Government © 2024. All rights reserved.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Culture and power: the rise of Afrikaner nationalism revisited*1

2010, Nations and Nationalism

Related Papers

Hermann Giliomee

International Journal of the Sociology of Language

Mariana Kriel

André du Toit

Lindie Koorts

The study of international intellectual networks has the potential of making an important contribution to South African historiography, in particular the study of Afrikaner nationalism. Afrikaner nationalism itself is shrouded in mythology and has, rightly or wrongly, been equated with white racism and apartheid. For a large part of the twentieth century, an influential theory held that Afrikaner nationalism and racism was the result of an isolationist frontier mentality. According to this theory, Dutch frontier farmers moved deep into the South African interior where they led an isolated existence, maintaining a “primitive” 17th century Dutch Calvinism, far removed from intellectual developments in Europe. This theory was challenged by Marxist scholars in the 1970’s, but the basic isolationist myth was never addressed – and therefore never questioned. However, when the number of prominent Afrikaners, who studied in Europe, and especially in the Netherlands, is taken into account, the perception that Afrikaner nationalism was an isolated phenomenon becomes problematic. Three successive 20th century South African prime ministers studied in Europe – and two of them in the Netherlands. Of these, Dr. D.F. Malan is of particular interest. He studied theology at the Stellenbosch Seminary, which was established by Utrecht alumni, and followed the example of his professors by pursuing further studies at the University of Utrecht, where he obtained a Doctorate in Divinity in 1905. His arrival in Utrecht in October 1900 coincided with the Dutch public’s passionate displays of sympathy for their stamverwanten in South Africa who were fighting in the Anglo-Boer War. Being in the Netherlands enabled Malan to observe and grasp the realities of European power politics, which prevented the Dutch government from providing any substantial support to the Boers. He travelled the European continent at a time when nationalism was as yet untested by the horrors of the First World War and his contacts with international students at a students’ conference in Denmark confirmed his belief in the virtues of cultural diversity, much in the spirit of the German philosopher, Herder. The influence exerted by Malan’s Dutch mentor, Prof. J.J.P. Valeton Jr. was also significant: at a time when Abraham Kuyper was prime minister, Valeton taught Malan that politics and religion were irreconcilable. Malan made Valeton’s views his own, and refrained from politics for ten years after completing his studies, but after great internal struggle, his career eventually followed the same pattern as Kuyper’s. The aim of this paper is to investigate the influence of D.F. Malan’s studies at the University of Utrecht on his formulation of Afrikaner nationalism, and through this, to place Afrikaner nationalism within a broader, international context. This will challenge the myth that Afrikaner nationalism was formulated by people who were isolated from intellectual movements in Europe.

Michael Pesek

In this article I investigate the relationship between Afrikaner nationalism, apartheid and philosophy in the context of the intellectual history of the University of the Free State. I show how two philosophers that were respectively associated with the Department of Political Science and the Department of Philosophy, H J Strauss (1912-1995) and E A Venter (1914-1968), drew on the philosophy of Herman Dooyeweerd to justify separate development. I argue that their interpretation does not simply amount to a wilful misunderstanding of Dooyeweerd, but rather that the foundational moment of Dooyeweerd’s philosophy involves an interpretive violence that accommodates this intepretation.

Masilo Lepuru

The role of the missionaries in the conquest of Afrika has led to the emergence of "Afrikan liberalism" and its idea of Afrika. Christianity and European miseducation as instruments of epistemicide created a group of "new Afrikans" who, as the leading ideologues of the conquered Afrikans, were infected with European liberalism and humanism. The latter are the conditions necessary for the propagation of an inclusive Afrikan nationalism which seeks to integrate non-Afrikans, such as Europeans and Asians, into Afrika. Anton Lembede, who was a member of the new Afrikans, propagated the political philosophy of Afrikanism, which was premised on an exclusive idea of Afrika for the Afrikans. Robert Sobukwe and Steve Biko, through A. P. Mda's idea of "broad nationalism", pursued an inclusive idea of Afrika. This article seeks to foreground Lembede's exclusive idea of Afrika in contrast to the Azanian tradition's non-racial and inclusive idea of Afrika, as encapsulated in Sobukwe's metaphor of the Afrikan tree and Biko's metaphor of the Afrikan table. This article engages in a brief comparative analysis of two forms of Afrikan nationalism in South Africa to underscore the two ideas of Afrika.

Nations and Nationalism

Laurence Piper

In Neville Alexander and Arnulf von Scheliha (eds.). 2014. Language policy and the promotion of peace. African and European case studies. Pretoria: UNISA Press.

The International Journal of African Historical Studies

William Worger

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Wessel P Visser

Anthony Löwstedt

Marijke Du Toit

Nations & Nationalism

Gary Baines

De Gruyter eBooks

Hugo van der Merwe

New Contree

Chris Saunders SAUNDERS

Journal of Southern African Studies

Robbie Aitken

Louise Vincent

Danelle van Zyl-Hermann

African Studies

Paul B Rich

Stephan Bezuidenhout

mottie tamarkin

Leidschrift 4 (June 1988), 93-103.

Teun Baartman

Wilhelm Snyman

Hans Erik Stolten

en.scientificcommons.org

Sabelo J Ndlovu-Gatsheni

Academia Letters

Dr Nasiphi Moya

Religion and Neo-Nationalism in Europe

Robert Vosloo

Apartheid still exits South Africa

Farai Mushangwe

South African Historical Journal

Africa Spectrum

Pieter Duvenage

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Home — Essay Samples — Government & Politics — Nationalism — The Spread of Afrikaner Nationalism in South Africa

The Spread of Afrikaner Nationalism in South Africa

- Categories: Nationalism South Africa

About this sample

Words: 2180 |

11 min read

Published: Feb 12, 2019

Words: 2180 | Pages: 5 | 11 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, the great trek: a battle for survival, the ‘poor white problem’, afrikaner nationalism essay conclusion.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Government & Politics Geography & Travel

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1380 words

6 pages / 2528 words

3 pages / 1549 words

3 pages / 1500 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Nationalism

The rise of white nationalism and extremism poses a significant threat to societies around the globe. While education has long been hailed as a tool to combat ignorance and intolerance, the advent of social media has introduced [...]

White nationalism and extremism have unfortunately become increasingly prevalent in educational institutions in recent years, sparking concerns and debates about the roots of this troubling trend and how to address it [...]

White nationalism has become a prominent and contentious issue in American politics and society, shaping the discourse surrounding race relations, immigration policies, and national identity. Stemming from a long history of [...]

Nationalism and sectionalism are two concepts that have played a significant role in shaping the history and politics of the United States. While both ideologies have had an impact on the development of the nation, they are [...]

June 26, 1963, post WWII, a time were the United States and the Soviet Union were the world’s superpowers. The two powers fought a war of different government and economic ideologies known as the Cold War. During the time of the [...]

Imagine a time when the world was on the brink of change, when societies were transforming, and nations were awakening to their own unique identities. This was the era of nationalism in the 1800s - a profound movement that swept [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

History Grade 11 - Topic 4 Contextual Overview

Introduction:

In the previous section, we have covered issues of race and science and how these dominated the 19th and 20th centuries. In this section, we approach this context in a slightly different manner. We examine the infrastructural and ideological frameworks which influenced the processes and politics of exclusion in the early 20th century South Africa, and elsewhere in the African context and also in the Middle East. One concept that will best conceptualize and frame our discussion is nationalism. Nationalism has different ethos, but, however, we are concerned with understanding how this ideology as a phenomenon that changed its form during the second world war. We trace this phenomenon from a longer historical perspective in order to trace and most importantly appreciate its continuities and discontinuities in society. Standard histories argue that the basis of nationalism emerged in Europe, and this included the conglomeration of Italy and Germany and the revolutions of 1830 and 1848. [1]

Much of our discussion will focus on the origins of nationalism, and we will make an assessment of whether this feature (nationalism) is peculiar to European societies or there are traces we can find in other parts of the world in which to construct and enhance our understanding of the genesis of nationalism. The former holds true, and this point will be further belaboured elsewhere in this essay. European empires provoked the emergence of various of nationalism across the colonial world through the process of colonization and genocidal destruction of indigenous peoples and their local customs, histories, and traditions. On the part of colonized societies, nationalism served as an ideological toolkit to unify all oppressed peoples in society. Integral to this view is that these forms of political mobilization were largely by the Cold War. This will become clearer in the section on Arab and Jewish nationalism in the Middle East, in order to understand nationalism from both perspectives of the groups concerned here.

What is nationalism:

In this section, we will define key concepts such as nationalism, and also provide the historical bases of this concept and how it become a global feature in modern societies. There is no clear-cut definition of what nationalism is. However, most textbook definitions define nationalism as a feeling of belonging to a nation which then leads to loyalty or in some ways, patriotism. Belonging somewhere is a key feature of nationalism in many definitions. [2]

How did nationalism originate?

It is argued that before nationalism societies were mainly feudal. This meant that ordinary people or commoners were subject to the King who ruled by divine plan. [3] In this view, Churches were powerful institutions in reinforcing authority of lineages, i.e., princes, kings, chiefs. This idea was sustained all over the world for 1000s of years. However, the Modern idea of nations/nationalism first emerged in Western Europe during 1700s and 1800s. Here, new social classes (inspired by enlightenment thinking) challenged the old feudal kingdoms/empires. [4] For example, philosophers such as Jean Jacques Rousseau alerted French people to ‘will of the majority’. The key objective here was to achieve ‘national sovereignty’ of the people rather than accept absolutist rule of French kings. This was central objective of the French Revolution in 1789.

How did nationalism spread?

In 19th century Europe, a set of civil wars signalled awakening of European nations. Major revolutions in the 1830s and onwards occurred across Europe. In France, King Charles X was overthrown, and a constitutional monarchy was established. The United Kingdom of the Netherlands led to the Belgian Revolution and ultimately the Belgian independence from the Netherlands in 1832. In Greece, the establishment of independent Greece after decade-long struggle against Ottoman Empire. In Poland, around November, the Uprising against Russian Empire – though crushed by Russia, helped to forge Polish nationalism. [5]

Essentially, the 1848 revolutions marked a series of political upheavals throughout Europe. These began in Europe and had impacts in various parts of the world. In this view, the 1830 and 1848 Revolutions were very significant on the development of nationalism in many societies. [6] In some countries the conservative rulers relied on force to stay in control and many civil wars broke out as the people wanted nationalist movements to be recognised. In France, in 1830, King Charles X was overthrown, and a constitutional monarchy was established (as briefly mentioned before).

In Poland in 1830, the Poles rose against the Russian Empire, although the revolution was crushed, Polish nationalism grew. In 1848, nationalist revolutions broke out in France, the German states, the Italian states, and Austria, but the hold by the aristocracy and military in these countries was still too strong to bring about true reform. Germany and Italy, Zollverein (toll union) in the north German states stimulated unity under Prussian leadership. Bismarck, the Prussian nationalist, took the lead, and after three wars, united the Germans into a ‘new’ nationalist German state. This created a strong power in central Europe for first time in European history and by the end of the century, became greatest power in Europe: industrious people plus great resources in coal and iron. Nationalism really took root in Europe. Revolts in the 8 Italian states stimulated Italian nationalism against mainly foreign rule. [7] Under the nationalists, Cavour and Garibaldi, Italy was liberated and united under an Italian king. Upshot, the establishment of modern nation states, helped shape Europe along nationalist lines. Political revolutions and industrial growth led to changes in society. Industrialisation in Europe strengthened and entrenched nationalism in Europe by 1900 and in Africa during the first half of the 20th century.

New Imperialism?

Because of Industrial Revolution, new products were developed and exported to new buyers in new markets. Therefore, the rivalry and competition added to conflict and tension in Africa among the European colonisers. In 1885 Bismarck from Germany called together the Congress of Berlin to solve disputes and Africa’s political, colonial boundaries were entrenched and nation states were introduced in Africa without consultation with the Africans. Colonisation that had its roots in the economic prosperity of the Industrial Revolution laid the foundations for nationalism in Africa. The colonised countries began to unite their people in an effort to regain their independence. Economic prosperity from Industrial Revolution set a new middle class that supported nationalism and the ideas of unity, development, and wealth. These emergent middle classes began to have more of a say in governments and the policies they made. They promoted the ideas of a national identity, unity, and cohesion in society. In colonised countries, the middle-class leaders stimulated the rise of popular nationalist movements against conservative rule. In essence, World War II (WWII) stimulated the rise of African and Asian nationalism against colonial rule. The colonies began to pressurise the colonisers for freedom and decolonization began.

The theory of nationalism as an imagined community:

This idea is based on the book Imagined Communities by Benedict Anderson, published in 1983. He promotes the idea that a nation is a socially constructed community that relies mostly on perceptions and feelings. [8] Members that make up a nation are bound by a mental image or affinity rather than an actual one, e.g., they claim to be a united force based on a proud shared heritage and history, language, culture, customs, literature, etc. These feelings of belonging and other nationalist ideas were spread through Europe by the invention of printing. Powerful symbols were adopted to express national identity. [9] Patriotism, militarism, and nationalism made for a very powerful and dangerous combination of forces, often destructively deployed to expand territory and power. But, most importantly, also to defend the imagined community.

African Nationalism:

Background and historical overview:

There was no South Africa (as we know it today) before 1910. Britain had defeated Boer Republics in the South African War which date from (1899–1903). There were four separate colonies: Cape, Natal, Orange River, Transvaal colonies and each were ruled by Britain. They needed support of white settlers in colonies to retain power. [10] In 1908, about 33 white delegates met behind closed doors to negotiate independence for Union of South Africa. The views and opinions of 85% of country’s future citizens (black people) not even considered in these discussions. British wanted investments protected, labour supplies assured, and agreed on the fundamental question to give political/economic power to white settlers. [11] This contextual article back in time to examine how this volatile context of dispossession and conquest in South African history served as an ideological backdrop for the rise of different stands of African nationalist thought in the country and elsewhere in the world.

The Union Constitution of 1910 placed political power in hands of white citizens. However, a small number of educated black, coloured citizens allowed to elect few representatives to Union parliament. [12] More generally, it was only whites who were granted the right to vote. They imagined a ‘settler nation’ where was no room for blacks with rights. In this regard, white citizens called selves ‘Europeans’. Furthermore, all symbols of new nation, European language (mainly English and Dutch), religion, school history. In this view, African languages, histories, culture were portrayed as inferior. [13]

Therefore, racism was an integral feature in colonial societies, and this essentially meant that Africans were seen as members of inferior ‘tribes’ and thus should practise traditions in ‘native’ reserves. Whilst, on the other hand, in the settler (white) nation, black people were recognized only as workers in farms, mines, factories owned by whites. Thus, black people were denied of their political rights, cultural recognition, economic opportunities, because of these entrenched processes and politics of exclusion. In 1910 large numbers of black South African men were forced to become migrant workers on mines, factories, expanding commercial farms. In 1913, the infamous Natives Land Act, worsened the situation for black people as land allocated to black people by the Act was largely infertile and unsuitable for agriculture. [14]

Rise of African Nationalism:

In the 19th century, the Western-educated African, coloured, Indian middle class who grew up mainly in the Cape and Natal, mostly professional men (doctors, lawyers, teachers, newspaper editors) and were proud of their African, Muslim, Indian heritage embraced idea of progressive ‘colour-blind’ western civilisation that could benefit all people. This was a more worldly outlook or form of nationalism which recognized all non-white groupings across the colonial world as victims of colonial racism and violence. [15] However, another form of nationalism recognized the differences within the colonized groups and argued for a stricter and more specific definition of what it means to be African in a colonial world. These were some differences within the umbrella body of African nationalism and were firmly anchored during the course of the 20th century.

African Peoples’ Organization:

One of the African organisations that led to the rise of African nationalism was the African People’s Organisation (APO). At first the APO did not concern itself with rights of black South Africans. They committed themselves to the vision that all oppressed racial groups must work together to achieve anything. Therefore, a delegation was sent to London in 1909 to fight for rights for coloured (‘coloured’. In this context, ‘everyone who was a British subject in South Africa and who was not a European’). [16]

Natal Indian Congress (NIC):

Natal Indian Congress Natal Indian Congress (NIC) was an important influence in the development of non-racial African nationalism in South Africa. Arguably, it was one of the first organisations in South Africa to use word ‘congress’. It was formed in 1894 to mobilise the Indian opposition to racial discrimination in Colony. [17] The founder of this movement was MK Gandhi who later spearheaded a massive peaceful resistance (Satyagraha) to colonial rule. This protest forced Britain to grant independence to India, 1947. The NIC organised many protests and more generally campaigned for Indian rights. In 1908, hundreds of Indians gathered outside Johannesburg Mosque in protest against law that forced Indians to carry passes, passive resistance campaigns of Gandhi and NIC succeeded in Indians not having to carry passes. But, however, they failed to win full citizenship rights as the NIC did not join united national movement for rights of all citizens until 1930s, 1940s

South African Native National Congress (now known as African National Congress):

In response to Union in 1910, young African leaders (Pixley ka Isaka Seme, Richard Msimang, George Montsioa, Alfred Mangena) worked with established leaders of South African Native Convention to promote formation of a national organization. The larger aim was to form a national organisation that would unify various African groups. [18] On 8 January 1912, first African nationalist movement formed at a meeting in Bloemfontein. South African National Natives Congress (SANNC) were mainly attended by traditional chiefs, teachers, writers, intellectuals, businessmen. Most delegates had received missionary education. They strongly believed in 19th century values of ‘improvement’ and ‘progress’ of Africans into a global European ‘civilisation’ and culture. In 1924, the SANNC changed name to African National Congress (ANC), in order to assert an African identity within the movement. [19]

Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU):

The Industrial and Commercial Workers Union African protest movements that helped foster growing African nationalism in early 1920s . Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU) was formed in 1919 was led by Clements Kadalie, Malawian worker. This figure had led successful strike of dockworkers in Cape Town. Mostly active among farmers and migrant workers. But, only temporarily away from their farms and was very difficult to organise. The central question to pose is to examine the ways in which the World War II influence the rise of African nationalism? Essentially, there were various ways that WW II influenced the rise of African nationalism. [20] Firstly, through the Atlantic Charter, AB Xuma’s, African claims in relation to this Charter. In addition, the influence of politicized soldiers returning from War had a significant impact.

The Atlantic Charter and AB Xuma’s African claims Churchill and Roosevelt issued the Atlantic Charter in 1941, describing the world they would like to see after WWII. To the ANC and African nationalists generally, the Atlantic Charter amounted to promise for freedom in Africa once war was over. Britain recruited thousands of African soldiers to fight in its armies (nearly two million Africans recruited as soldiers, porters, scouts for Allies during war). This persuaded Africans to sign up and Britain called it ‘a war for freedom’. [21] The soldiers returning home expected Britain to honour their sacrifice, however, the recognition they expected did not arrive and thus became bitter, discontented, and only had fought to protect interests of colonial powers only to return to exploitation and indignities of colonial rule.

Different strands of African Nationalism:

It must be borne in mind that African nationalism was not monolithic there were competing versions within the ideologically. The ideology stands for unification of all oppressed people, and more especially the African people. The first strand is more moderate and unitary across the colonialized groups. This was advocated by organizations like APO, NIC, ICU and SANNC and many others. However, with the spread of Ethiopianism and Garveyist philosophies in the 1940s and these were especially accentuated by newspapers such Abantu-Batho, a more radical interpretation of African unity emerged in South Africa and elsewhere in the continent. This was mostly favoured by the black youth within the ANC and across the political divide. In short, the older activists like a Nelson Mandela and son within the ANC and other mainstream liberation movements in the country supported non-racialism and promoted the idea of nation-building. [22] A term synonymous to the nation-state (emphasized above), which merely treats people as universal subjects devoid of local histories, cultures, and politics. On the other hand, the Africanist section supported the idea of ‘Africa for Africans’ espoused by Marcus Garvey. The idea of Nation building was firmly anchored in the late 1950s when the document called the Freedom Charter was adopted by the ANC, as a policy position. This document stipulated that “the land belongs to all those who live in, black and white”. This angered the ANC Youth League and more generally, the Africanist section within the ANC who believed in republicanism (an alternative version of black modernity), it was assumed. This led to a split within the ANC, and a movement called the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) was born. The struggle for what South Africa should be like is an ongoing tension that continues to dominate public discussion today. [23]

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this essay has attempted to examine the historical circumstances in which black people were denied of their political, economic, and social rights in the early 1990s. There are various that must be acknowledged in order to have a granular understanding of the larger and longer history of African nationalism, and this examination may exceed the scope of this essay. However, the central argument made here is that the rise of African nationalism in all its different ethos and manifestations was premised on humanizing black people in various parts of the colonial world. To stress this point, African nationalism emerged as a vehicle of resistance and humanization. Finally, African nationalism cannot be read outside the international context (as shown throughout the paper), as we have to take into account various factor which effectively influenced the spurge of this ideological outlook in society.

Rise of Afrikaner Nationalism:

Within Volskatpitalisme, there were two groups, namely the Broederbond and the Reddingdaadbond. [24] The broederbond were not against capitalism but were firmly against foreign capital. The Reddingdaadbond on the other hand was formed by Afrikaner businessmen who strongly encouraged Afrikaner people to shop only in Afrikaner shops, invest in Afrikaner banks as well as use Afrikaner insurance companies. [25] In 1939, the Afrikaner Volkskongres which was a new Afrikaner economic movement took a strong stance against foreign investment and were strongly against foreign capitalist system as they saw it as a destruction of the Afrikaner nation. [26]

The media was another strong tool which the Afrikaner nation utilised to spread Afrikaner nationalism. There were new emerging Afrikaner print media such as Die Burger and Die Transvaler which were Afrikaans language newspapers. In addition, these newspapers portrayed the Afrikaner nation through stories as this homogenous nation with a strong moral purpose, heroic past which had a place amongst other nations. [27] These ideas quickly spread to other print media such as the Christian-nationalistic journal Koers, Inspan and were published in books by Burger Boekhandel publishing house. [28]

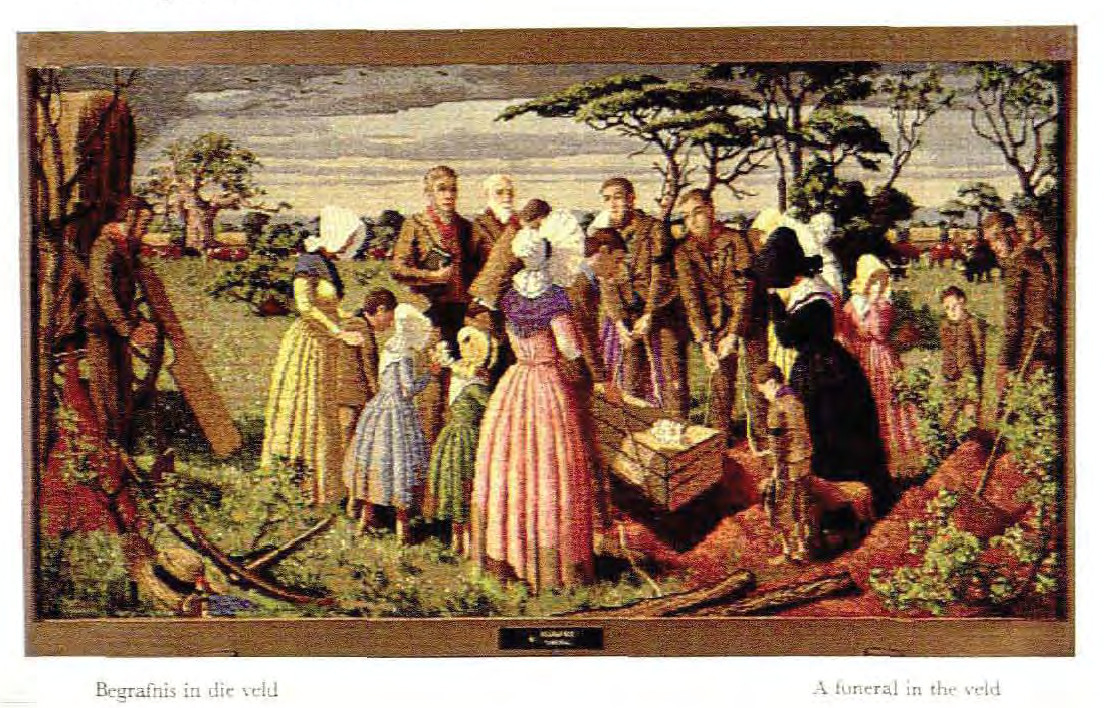

Much of the Volk notion in South Africa was based on the ideas of Abraham Kuyeper who was a Dutch statesman, politician and theologian. [29] He believed in God’s authority over spheres of creation. Spheres according to him had to be preserved and protected from ideas such as equality, solidarity or freedom of the French Revolution because to him, all these ideas challenged God’s authority. [30] Paul Kruger was the president of the Transvaal Republic and formed the Nederduitsch Hervormde Kerk which was the Dutch Reformed Church. He referred to Afrikaner history in South Africa as ‘sacred’ and that the Volk were the chosen people. [31] He made the Great Trek seem as Exodus from British rule in Cape to the Promised Land of Boer Republics. He used Kuyper’s ideas as Afrikaner theologians also used Kuypers ideas to justify the Afrikaners refusal of ‘British-designed’ South Africa. In addition, the Afrikaners did not was to co-exist with other ethnic groups as minority. Another part of Volk definition is that only white South African Afrikaners had the right to land in South Africa. Black people were defined as other nations who needed to live their own tribal areas. Afrikaners considered themselves as having a God-ordained right to establish exclusive Volk which saw white Afrikaans-speakers as regarded as the legitimate citizens. [32]

Afrikaner nationalism used education both to define and create different classes in South Africa. [33] To do this, they defined the Volk as superior and different from other races which meant that Afrikaners became the middle and upper classes, while black people were relegated to lower classes. This exclusive definition of Volk resulted from various factors such as missionary education of blacks which was inadequate as it only equipped black people to compete with poor white Afrikaners for jobs. [34] In addition, the Economic depression caused white Afrikaner unemployment to grow which increased competition for jobs. [35] Affirmative action policies also excluded black people whether they were educated or not from participating in the Afrikaner labour market. The other factors which played a role in Afrikaners occupying those classes was that promotion at work were reserved for white people (especially Afrikaners) and affirmative action legislations which established a ‘Colour Bar’ in employment which gave white people preference to black people. [36]

Relegation of blacks to lower working class through labour policies was reinforced through educational policies. When the Nationalist Party (NP) won the election in 1948, it gave Afrikaner nationalists the opportunity to fully implement an educational programme called Christian National Education (CNE). [37] The CNE was a segregated education system which created separate schools for South African population groups which were whites, Indians, Coloureds and Africans. This segregated education system favoured whites and disadvantaged blacks. Black people received Bantu education which was the name given for black people’s education. The Bantu education made it clear that it was designed to teach blacks to be ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water’ for white-run economy and society. [38]

The Volk changing views in relation to religion as time progressed. During the 19th the Dutch Reformed Church help practical rather than ideological views of racial segregation. [39] For example, they regarded racial segregation as a peaceful way of governing a country which had such a diverse racial population. However, after the 20th century economic depression, this attitude changed both in terms of education and labour. Suddenly, a new group of poor (mostly Afrikaner) whites emerged. In 1939, there was Church involvement which advocated for an Afrikaner state which would create a Christian civilisation. Thus, the notion of ‘divine right’ of the Volk to stay separate and rule the surrounding black nations. The DRC was then considered an important institution in creating an Afrikaner nationalist identity as it had provided moral, social security to remote Afrikaner farmers throughout the 19th century and later recreated communities for thousands of displaced poor Afrikaners entering the city. [40] In addition, the Church was seen as reinforcing family idea, which instilled the idea of women as ‘mothers of the nation’ who’s duty was to create as many Afrikaner children as they could in order to bring them up as nationalists. All these factors combined drove Afrikaners towards an exclusive nationalism which provided Afrikaner nationalist leaders with enough white support to win the 1948 election.

Nationalism in power- towards Apartheid:

In 1948 the National Party (NP) of DF Malan had won over support of majority of poor and middle class Afrikaners as well as small-scale and commercial farmers. This was because these groups felt threatened by developments in the 1940s which saw growth of large, increasingly organised black working class. The NP use emotional racist rhetoric such as ‘swart gevaar’ + ‘oroorstroming’ which mean black danger + flooding into cities. [41] This racist rhetoric worked as it appealed to all white groups such as white workers who feared that black people would take their jobs and to white farmers who significant labour as their workers moved to cities. Upon gaining power, the NP promised to defend the interests of these groups by suppressing black resistance and by increasing control and exploitation of black labour. [42] As the oppressive policies of apartheid were viewed to be succeed in crushing black resistance by creating more opportunities for white people and creating a lot of profit margins for all white businesses and a general higher standard of living for all white workers, other whites eventually supported and stood behind the apartheid government. 40 years of nationalist rule ensured that Afrikaner capitalists and professionals achieved their goal of being equal with foreign capital. In addition, they established their culture and language. Today however, the ideology of Afrikaner nationalism offers little to Afrikaners in a democratic, non-racial South Africa except to a few extreme and exclusive Afrikaner nationalist communities such as Orania town. [43]

The Middle East:

Nationalisms: Origins of Arab nationalism and Jewish

The Jewish nation, in the modern sense of a nation, only came into existence in the 19th century. [44] Farming communities in Palestine practised Judaism as a religion. When the Romans occupied Palestine, the Jews rose in defiance, however the Romans suppressed the rebellion and persecuted the Jews. [45] Many Jews escaped and ran all over the world during the diaspora and settled far afield. However, as capitalism spread, some Jews in Western Europe accumulated wealth by becoming merchants or manufacturers. Others in Eastern Europe remained poor. Jews leaned towards living together in communities where their culture, beliefs and their traditions helped them maintain their own identity. Despite this, Anti-Semitism was still rife in Europe and many Jews were persecuted. [46]

Most Arab people in the Middle East and North Africa were converted to Islam from the seventh century onwards. As the Arabs continued to conquer territory, the religion spread from being an Arab one to a religion that was practised by people from all parts of the world. Arabic became the dominant language and Arabic customs and traditions spread like wild fire. By the 1500s, the Ottoman Empire was set up by the Turks. [47] Due to discrimination and persecution, the Arabs rose in local rebellions against the Turks. However, these were futile as they did not bring about change.

The Balfour Declaration:

In the first of the 20th century, a number of critical events took place which led to the establishment of Israel as a state in 1948. In 1917, the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Arthur James Balfour wrote to Lord Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, with a promise to assist Jews establish a Jewish state in Palestine after WWI. This letter became known as the Balfour Declaration of 1917. [48] The Zionists- People who believe in the development and protection of a Jewish nation in what is now Israel- used this Declaration to pressurise later British governments to support a Jewish state in Palestine. Britain was in a complicated situation because they were trying to mobilise support of Jews in the USA while simultaneously trying to win Arab support for its war against Turkey. As a result, this Declaration clashed with Britain’s promise to Arabs that Britain would support Arab independence in the Middle East. [49] The Zionists were in no way conflicted and clearly saw the Declaration as a clear recognition of Jewish claims.

Origins and establishment of the state of Israel after the Second World War and the 1948 War:

After WWI, Britain and Frances were mandated by the League of Nations to rule over most of the Middle East, except for Saudi Arabia which became an independent Arab kingdom. In 1922, Britain grated independence to three countries in the Middle East, namely Egypt, Trans-Jordan and Iraq. Britain’s mandate over Palestine stated that Britain should honour and implement the Balfour declaration. Zionists met and interpreted the mandate of the League of Nations with enthusiasm as they viewed the international community as supporting the creation of a national home for Jews in Palestine.

The UN Partition Plan was based on British proposals and was supported by the US, Soviet Union and other Western powers. More than half of Palestine was allocated to the Jewish state. [50] Palestinians and their Arab allies rejected the UN partition plan and soon a Civil war erupted. Palestinians units attacked British and Jewish installations in protest. The Haganah attacked and destroyed over 300 Palestinian villages in retaliation. [51] In May 1948, Britain had lost control of the situation and started pulling out its 100000 troops from Palestine. On 14 May 1948, David Ben-Gurion declared the state of Israel on the basis of the UN plan.

Britain encouraged Jewish immigration and Jews bought land from Palestinians. Palestinian Arabs demanded an end to Jewish immigration. Between 1921 to 1929, Palestinian Arabs organised anti-British protests which caused violent clashes between Arab and armed Jewish groups and the police. Britain suppressed the Arab protests by executing three Palestinian leaders. Today, these leaders are remembered as martyrs in the Palestinian struggle for their self-determination. In the 1930s, Jewish immigration increased as Hitler began persecuting Jews in Germany. In 1936, Palestinian uprising began with general strikes occurring. These strikes were organized by a Palestinian movement called the Arab Higher Committee (AHC). [52] Jewish and Britain targets were attacked. Jewish groups responded by attacking Arab communities.

Britain intervened in 1937 in the conflict by proposing that Palestine should be divided into both a Jewish and Arab state. Palestinian Arabs vehemently rejected this proposition while Jews supported it in principle but not with the borders which Britain proposed. Despite these opposing views, Britain tried to put pressure on both the Jews and Arabs to accept their proposition. In addition, Britain tried to limit Jewish immigration but were met with strong protests from Jews. When WWII broke out, matters were placed on hold in Palestine. At the end of WWII, the world was a very different place because of the Holocaust which occurred in Germany which saw the Nazis murder of approximately 6 million Jews. After the Holocaust, there was an increased determination by Zionists to force Britain to give them independent land in the Middle East. This significantly increased the support of the West to the Zionist cause.

In 1946, Irgun- Which was a Jewish armed group led by Menachem Begin- blew up the British military headquarters in Jerusalem which saw over a 100 people killed. [53] After this incident, Britain handed the problem to the UN. In April 1947, the UN deliberated on the Palestinian question and concluded in early 1948 that Palestine should be divided in half between Palestinian Arabs and Jews. More than of Palestine was given to the Jewish state. Palestinians and their Arab allies again rejected the UN proposition and a Civil war erupted as a result. On the 14th of May 1948, David Ben-Gurion declared the state of Israel based on the UN plan. The Israeli state was recognised by the Soviet Union and Western countries. [54] In retaliation, a military coalition of seven Arab states declared war on Israel which caused the 1948 war.

Different interpretations of the war: The Palestinian and Israeli perspectives on the 1948 War:

The Israeli see the war as Palestinian attacks which forced them to defend themselves like establishing the Haganah. The Israeli see the war as beginning in November 1947 when Palestinians attacked British installations and Jewish settlers. As a result, they interpret the international support for the state of Israeli after the UN division proposition failed as a justification for the war. Thus Israeli argues that they fought for Israeli independence after defeating the Arab coalition. They further argue that they had no choice but to fight to win. Israeli argues that there were some atrocities committed by their side but that these were extremists and were an exception. [55]

The Arab Palestinians argue that Britain was largely to blame for the Arab marginalisation in Palestine. They argue that Britain supported Jewish immigration and the Haganah and were actively training Jewish militants. Palestinians argue that the UN resolutions were unjust because majority of the land was allocated to the Jews. In addition, they argue that Jewish tactics during the war amounted to ethnic cleansing. Furthermore, Palestinians argue that their villages were destroyed leaving Palestinians displaced without any compensation. Palestinians further view the war as them being treated as second class citizens which caused them to become refugees. [56] The Arabs therefore call this war the An-Nakba- catastrophe- as it saw more than 700000 of their population either killed or chased away from their home.

The question of Palestine- conflict of nationalist aspirations between Palestine and Israel:

Jewish nationalism became more cohesive and determined to survive any and all Palestinian attacks or attempts to take over Israel. Thus, security became the main focus and a militarists retaliated swiftly to contain any Palestinian attack. Arab nationalism did not develop as Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Jordan all became independent states. In addition, most Arab states experienced conflict, corruption and factionalism. As a result, governance within these states was mostly based on authoritarianism. [57]

The Arab-Israeli conflict: the issue of refugees, military occupation of the West Bank; responses of Israelis and Palestinians: Intifadas and peace processes between 1979 and 2000; as well as the roles of USA, Palestinian and Israeli leaders.

Since Israel gained its statehood in 1948, there has been on-going conflict Arab-Israeli conflict which has caused a lot of damage and suffering to many. This conflict has the capacity and potential to incite major war in the area which would have severe repercussions internationally. The 1948 war created a refugee crises which saw more than one million Palestinian people disbursed in refugee camps in the countries around the world with inhumane conditions. [58] Majority of the people who fled to the refugee camps thought they would only temporarily stay there and eventually be allowed to go back home but as Israeli established itself, this became clear that it would not happen. There were other families who moved on to other countries, however thousands remain there. Host countries didn’t have enough resources to cope with the refugee needs, thus poverty grew which created military groups to develop out of this refugee crisis who began to mount guerrilla attacks on Israeli targets. The main military group was founded by Yasser Arafat in 1958 and its goal was to establish a Palestinian state. [59]

In 1967, in just a space of 6 days, the Israeli army had destroyed Arab armed forces and occupied Arab land on the Golan Heights, the West Bank of the Jordan River, the Gaza Strip and the entire Sinai Peninsula. This significantly increased the territory that the Israeli occupied. Israeli leaders were confident of US support but refused to return the occupied land which increased Arab anger. [60] When Israel refused to return the occupied lands, Arab countries won the support of many newly independent countries. The UN passed Resolution 242 which mandated that Israeli return all occupied territories and in return, the Arab states should recognise Israel as a state. Israel supported this but only if the Arabs did the same, but the Arab countries and many UN member states insisted that there should be an unconditional withdrawal from the occupied territories.

The years 1967-1987 were full of tension as Israel had occupied the last remaining parts of Palestine. Militant Palestinian armed groups set up to infiltrate Israel and launch internal guerrilla attacks and external missile attacks. Israeli retaliated more violently including bombing refugee camps and assassinating Palestinian leaders. Israeli government started forcibly taking Palestinian land and building Jewish settlement in order to ensure that they would never need to return the land. It diverted water supplies to the new Israeli settlements while Palestinian Arabs were herded into their own communities with little movement as they were surrounded by fences and military checkpoints. Because there was little development in Palestinian areas, unemployment and suffering in their towns and villages grew.

In December 1987, the frustration of the Palestinians reached to a boiling point which led to an uprising which was known as the first intifada. [61] Within weeks, protests broke out in all occupied areas, children, women and youth all fought with stones and bottles against Israeli guns. These images embarrassed the Israelis internationally, and as a result, their soldiers were issued with batons. Despite this, brutal beatings took place which left thousands with broken bones and even death. Soon, the Intifada took a more planned and revolutionary character where committees were set up in the occupied areas which boycotted Israeli taxes and shops, stopped working in Israeli businesses. Some made contact with other nationalist-aligned revolutionary groups for military training and arms and as a result new armed groups such as Hamas emerged in Palestine. [62] Armed attacks took place against Israel soldiers and settlers. Israeli responded with iron-fisted suppression.

In 1979 Israel and Egypt signed a peace treaty known as Camp David Accords. This treaty stated that Egypt would recognise Israel as a state in exchange for the return of the Sinai Peninsula. Secondly it stated that there would be a political settlement of the Palestinian issue which was based on an autonomous Palestinian State alongside Israel in Palestine. However, the PLO and its allies rejected this agreement immediately. Within Israel and the PLO, divisions began to emerge which was split between those who wanted the violence to continue and those who were prepared to make sacrifices in order for peace to reign. The Intifada disrupted the peace process, but after it subsided, leaders on both sides were willing to negotiate. In 2988 the PLO recognised the right of Israel to exist. And in 1993, after years of negotiation, the PLO and Israeli leaders met in Oslo, Sweden to sign the Oslo Accords. [63] Within these accords there was a framework for how the future of relations between the two parties would look like. It was agreed that there would be a creation of a Palestinian National Authority (PNA) over parts of the West Bank and Gaza strops. In these areas the Israeli army with withdraw and the PNA would take over administration over the area. However after the Oslo Accords, all these negotiations have fails. In Israel, frightened people have elected hardened conservative government to power. As a result, Israelis have insisted on terms which the Palestinians could not possibly accept. Palestinian nationalism has also hardened after the Oslo Accords and as a result, since the year 2000, there has been a second Intifada, followed by intensified conflict including deadly Israeli air strikes and as it stands, there is no peaceful resolution in sight. [64]

This content was originally produced for the SAHO classroom by Ayabulela Ntwakumba & Thandile Xesi.

[1] Breuilly, John. Nationalism and the State. Manchester University Press, 1993.

[2] Smith, Anthony Douglas, John Hutchinson, and Anthony D. Smith, eds. Nationalism. Oxford Readers, 1994.

[3] Batiza, Rodolfo. "The French Revolution and Codification-Comment on the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and the Napoleonic Codes." Val. UL Rev. 18 (1983): 675.

[4] Gascoigne, John. Cambridge in the Age of the Enlightenment: Science, Religion and Politics from the Restoration to the French Revolution. Cambridge University Press, 2002.

[5] Wimmer, Andreas. "Why Nationalism Works: And Why It Isn't Going Away." Foreign Aff. 98 (2019): 27.

[6] Kaufmann, Eric. "Complexity and nationalism." Nations and Nationalism 23, no. 1 (2017): 6-25.

[7] Bergholz, Max. "Thinking the nation: imagined communities: reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism, by Benedict Anderson." The American Historical Review 123, no. 2 (2018): 518-528.

[8] Anderson, Benedict. Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso books, 2006.

[10] Williams, Donovan. "African nationalism in South Africa: origins and problems." The Journal of African History 11, no. 3 (1970): 371-383.

[11] Feit, Edward. "Generational Conflict and African Nationalism in South Africa: The African National Congress, 1949-1959." The International Journal of African Historical Studies 5, no. 2 (1972): 181-202.

[12] Chipkin, Ivor. "The decline of African nationalism and the state of South Africa." Journal of Southern African Studies 42, no. 2 (2016): 215-227.

[13] Prinsloo, Mastin. "‘Behind the back of a declarative history’: Acts of erasure in Leon de Kock's Civilizing Barbarians: Missionary narrative and African response in nineteenth century South Africa." The English Academy Review 15, no. 1 (1998): 32-41.

[14] Gilmour, Rachael. "Missionaries, colonialism and language in nineteenth‐century South Africa." History Compass 5, no. 6 (2007): 1761-1777.

[15] Lester, Alan. Imperial networks: Creating identities in nineteenth-century South Africa and Britain. Routledge, 2005.

[16] Van der Ross, Richard E. "The founding of the African Peoples Organization in Cape Town in 1903 and the role of Dr. Abdurahman." (1975).

[17] Vahed, Goolam, and Ashwin Desai. "A case of ‘strategic ethnicity’? The Natal Indian Congress in the 1970s." African Historical Review 46, no. 1 (2014): 22-47.

[18] Suttner, Raymond. "The African National Congress centenary: a long and difficult journey." International Affairs 88, no. 4 (2012): 719-738.

[19] Houston, G. "Pixley ka Isaka Seme: African unity against racism." (2020).

[20] Xuma, A. B. "African National Congress invitation to emergency conference of all Africans."

[21] Kumalo, Simangaliso. "AB Xuma and the politics of racial accommodation versus equal citizenship and its implication for nation-building and power-sharing in South Africa."

[22] Ranuga, Thomas Kono. "MARXISM AND BLACK NATIONALISM IN SOUTH AFRICA (AZANIA): A COMPARATIVE AND CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE IDEOLOGICAL CONFLICT AND CONSENSUS BETWEEN MARXISM AND NATIONALISM IN THE ANC, THE PAC AND THE BCM. 1920-1980." PhD diss., Brandeis University, 1983.

[23] Shepperson, George. "Notes on Negro American influences on the emergence of African nationalism." The Journal of African History 1, no. 2 (1960): 299-312.

[24] O'meara, Dan. "The Afrikaner Broederbond 1927–1948: class vanguard of Afrikaner nationalism." Journal of Southern African Studies 3, no. 2 (1977): 156-186.

[25] Tomaselli, Keyan G. "Arts, apartheid struggles, and cultural movements." Safundi 20, no. 3 (2019): 338-358.

[26] Giliomee, Hermann. "Ethnic business and economic empowerment: the Afrikaner case, 1915‐1970." South African Journal of Economics 76, no. 4 (2008): 765-788.

[27] Hachten, William A., C. Anthony Giffard, and Harva Hachten. "The Afrikaans press: freedom within commitment." In The Press and Apartheid, pp. 178-199. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 1984.

[28] Ibid.,

[29] Baskwell, Patrick. "Kuyper and Apartheid: A revisiting." HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 62, no. 4 (2006): 1269-1290.

[30] Pahman, Dylan. "Toward a Kuyperian Ethic of Public Life: On the Spheres of Ethics and the State." Journal of Reformed Theology 12, no. 4 (2018): 413-431.

[31] De Klerk, Pieter. "The political views of Paul Kruger--interpretations over a period of 125 years." Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe 46, no. 2 (2006).

[32] Ibid.,

[33] Thompson, Leonard Monteath. "Afrikaner Nationalist Historiography and the Policy of Apartheid1." The Journal of African History 3, no. 1 (1962): 125-141.

[34] Dubow, Saul. "Afrikaner nationalism, apartheid and the conceptualization of ‘race’." The Journal of African History 33, no. 2 (1992): 209-237.

[35] Mariotti, Martine. "Labour markets during apartheid in South Africa 1." The Economic History Review 65, no. 3 (2012): 1100-1122.

[36] Ibid.,

[37] Hexham, I. R. "Christian national education as an ideological commitment." In Collected Seminar Papers. Institute of Commonwealth Studies, vol. 20, pp. 111-120. Institute of Commonwealth Studies, 1975.

[38] Ibid.,

[39] Vosloo, Robert. "The Dutch Reformed Church and the poor white problem in the wake of the first Carnegie Report (1932): Some church-historical and theological observations." (2011).

[40] Ibid.,

[41] Davidson, Yusha. "The doctrine of Swart Gevaar to the doctrine of common purpose: a constitutional and principled challenge to participation in a crime." Master's thesis, University of Cape Town, 2017.

[42] Terreblanche, S.J. “From White Supremacy and Racial Capitalism Towards a Sustainable System of Democratic Capitalism – A Structural Analysis.” (1994). University of Stellenbosch, 1994.

[43] Ibid.,

[44] Avineri, Shlomo. The making of modern Zionism: The intellectual origins of the Jewish state. Hachette UK, 2017.

[45] Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "First Jewish Revolt." Encyclopedia Britannica, February 4, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/event/First-Jewish-Revolt

[46] Gerstenfeld, Manfred. "The deep roots of anti-Semitism in European society." Jewish Political Studies Review (2005): 3-46.

[47] Mccarthy, Justin. "Chapter One: Palestine in The Ottoman Empire." In The Population of Palestine, pp. 1-24. Columbia University Press, 1990.

[48] Balfour, Arthur James. "The Balfour Declaration." Speeches on Zionism by the Rt. Hon. The Earl of Balfour (1917): 19-21.

[49] http://www.bu.edu/mzank/Jerusalem/p/period7-1-1.htm

[50] Salem, Walid. "Legitimization or Implementation? The Paradox of the 1947 UN Partition Plan." Palestine-Israel Journal of Politics, Economics, and Culture 9, no. 4 (2002): 7.

[51] Morris, Benny. "Response to Finkelstein and Masalha." Journal of Palestine Studies 21, no. 1 (1991): 98-114.

[52] Brown, Gabriel Healey. "Contested Land, Contested Representations: Re-visiting the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939 in Palestine." PhD diss., Oberlin College, 2016.

[53] Hoffman, Bruce. "The bombing of The King David Hotel, July 1946." Small Wars & Insurgencies 31, no. 3 (2020): 594-611.

[54] Friling, Tuvia. "David Ben-Gurion’s ‘road map’to independence, May 1948." In The British Mandate in Palestine, pp. 252-266. Routledge, 2020.

[55] Sela, Avraham, and Alon Kadish. "Israeli and Palestinian memories and historical Narratives of the 1948 war—An overview." israel studies 21, no. 1 (2016): 1-26.

[56] Ibid.,

[57] Cocks, Joan. "Jewish nationalism and the question of Palestine." Interventions 8, no. 1 (2006): 24-39.

[58] Pressman, Jeremy. "A brief history of the Arab-Israeli conflict." University of Connecticut (2005).

[59] Ibid.,

[60] Efrat, Elisha. The West Bank and Gaza Strip: A geography of occupation and disengagement. Routledge, 2006.

[61] Peretz, Don. Intifada: the palestinian uprising. Routledge, 2019.

[62] Singh, Rashmi. "The discourse and practice of ‘heroic resistance’in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict: The case of Hamas." Politics, Religion & Ideology 13, no. 4 (2012): 529-545.

[63] Barak, Oren. "The failure of the Israeli–Palestinian peace process, 1993–2000." Journal of Peace Research 42, no. 6 (2005): 719-736.

[64] Ibid.,

- Avineri, Shlomo. The making of modern Zionism: The intellectual origins of the Jewish state. Hachette UK, 2017.

- Balfour, Arthur James. "The Balfour Declaration." Speeches on Zionism by the Rt. Hon. The Earl of Balfour (1917): 19-21.

- Bennett-Smyth, T., 2003, September. Transcontinental Connections: Alfred B Xuma and the African National Congress on the World Stage. In workshop on South Africa in the 1940s, Southern African Research Centre, Kingston, Canada.

- Barak, Oren. "The failure of the Israeli–Palestinian peace process, 1993–2000." Journal of Peace Research 42, no. 6 (2005): 719-736.

- Baskwell, Patrick. "Kuyper and Apartheid: A revisiting." HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 62, no. 4 (2006): 1269-1290.

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "First Jewish Revolt." Encyclopedia Britannica, February 4, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/event/First-Jewish-Revolt

- Brown, Gabriel Healey. "Contested Land, Contested Representations: Re-visiting the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939 in Palestine." PhD diss., Oberlin College, 2016.

- Cocks, Joan. "Jewish nationalism and the question of Palestine." Interventions 8, no. 1 (2006): 24-39.

- Chipkin, I., 2016. The decline of African nationalism and the state of South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 42(2), pp.215-227.

- Davidson, Yusha. "The doctrine of Swart Gevaar to the doctrine of common purpose: a constitutional and principled challenge to participation in a crime." Master's thesis, University of Cape Town, 2017.

- De Klerk, Pieter. "The political views of Paul Kruger--interpretations over a period of 125 years." Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe 46, no. 2 (2006).

- Dubow, Saul. "Afrikaner nationalism, apartheid and the conceptualization of ‘race’." The Journal of African History 33, no. 2 (1992): 209-237.

- Efrat, Elisha. The West Bank and Gaza Strip: A geography of occupation and disengagement. Routledge, 2006.

- Friling, Tuvia. "David Ben-Gurion’s ‘road map’to independence, May 1948." In The British Mandate in Palestine, pp. 252-266. Routledge, 2020.

- Feit, E., 1972. Generational Conflict and African Nationalism in South Africa: The African National Congress, 1949-1959. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 5(2), pp.181-202.

- Gerstenfeld, Manfred. "The deep roots of anti-Semitism in European society." Jewish Political Studies Review (2005): 3-46.

- Giliomee, Hermann. "Ethnic business and economic empowerment: the Afrikaner case, 1915‐1970." South African Journal of Economics 76, no. 4 (2008): 765-788.

- Hachten, William A., C. Anthony Giffard, and Harva Hachten. "The Afrikaans press: freedom within commitment." In The Press and Apartheid, pp. 178-199. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 1984.

- Hexham, I. R. "Christian national education as an ideological commitment." In Collected Seminar Papers. Institute of Commonwealth Studies, vol. 20, pp. 111-120. Institute of Commonwealth Studies, 1975.

- Hoffman, Bruce. "The bombing of The King David Hotel, July 1946." Small Wars & Insurgencies 31, no. 3 (2020): 594-611.

- Mariotti, Martine. "Labour markets during apartheid in South Africa 1." The Economic History Review 65, no. 3 (2012): 1100-1122.

- Mccarthy, Justin. "Chapter One: Palestine in The Ottoman Empire." In The Population of Palestine, pp. 1-24. Columbia University Press, 1990.

- Morris, Benny. "Response to Finkelstein and Masalha." Journal of Palestine Studies 21, no. 1 (1991): 98-114.

- O'meara, Dan. "The Afrikaner Broederbond 1927–1948: class vanguard of Afrikaner nationalism." Journal of Southern African Studies 3, no. 2 (1977): 156-186.

- Pahman, Dylan. "Toward a Kuyperian Ethic of Public Life: On the Spheres of Ethics and the State." Journal of Reformed Theology 12, no. 4 (2018): 413-431.

- Peretz, Don. Intifada: the palestinian uprising. Routledge, 2019.

- Pressman, Jeremy. "A brief history of the Arab-Israeli conflict." University of Connecticut (2005).

- Salem, Walid. "Legitimization or Implementation? The Paradox of the 1947 UN Partition Plan." Palestine-Israel Journal of Politics, Economics, and Culture 9, no. 4 (2002): 7.

- Sela, Avraham, and Alon Kadish. "Israeli and Palestinian memories and historical Narratives of the 1948 war—An overview." israel studies 21, no. 1 (2016): 1-26.

- Singh, Rashmi. "The discourse and practice of ‘heroic resistance’in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict: The case of Hamas." Politics, Religion & Ideology 13, no. 4 (2012): 529-545.

- Terreblanche, S.J. “From White Supremacy and Racial Capitalism Towards a Sustainable System of Democratic Capitalism – A Structural Analysis.” (1994). University of Stellenbosch, 1994.

- Thompson, Leonard Monteath. "Afrikaner Nationalist Historiography and the Policy of Apartheid1." The Journal of African History 3, no. 1 (1962): 125-141.

- Tomaselli, Keyan G. "Arts, apartheid struggles, and cultural movements." Safundi 20, no. 3 (2019): 338-358.

- Vosloo, Robert. "The Dutch Reformed Church and the poor white problem in the wake of the first Carnegie Report (1932): Some church-historical and theological observations." (2011).

- Van der Ross, R.E., 1975. “The founding of the African Peoples Organization in Cape Town in 1903 and the role of Dr. Abdurahman”.

- van Niekerk, R., 2014. SOCIAL DEMOCRACY AND THE ANC: BACK TO THE FUTURE?. A Lula Moment for South Africa: Lessons from Brazil, pp.47-61.

- Williams, D., 1970. “African nationalism in South Africa: origins and problems”. The Journal of African History, 11(3), pp.371-383.

Return to topic: Nationalism - South Africa, the Middle East, and Africa

Return to SAHO Home

Return to History Classroom

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

Afrikaner Nationalism Essay For Students in English

Table of Contents

Introduction

Assuring and preserving Afrikaner interests was the primary objective of the National Party (NP) when it was elected to power in South Africa in 1948. After the 1961 Constitution, which stripped black South Africans of their voting rights, the National Party maintained its control over South Africa through outright Apartheid.

Hostility and violence were common during the Apartheid period. Anti-Apartheid movements in South Africa lobbied for international sanctions against the Afrikaner government following the Sharpeville Massacre of 1960, which resulted in the deaths of 69 black protestors (South African History Online).

Apartheid was not adequately representing the interests of Afrikaners, according to many Afrikaners who questioned the NP’s commitment to maintaining it. South Africans refer to themselves as Afrikaners both ethnically and politically. Boers, which means ‘farmers,’ were also referred to as Afrikaners until the late 1950s.

Afrikaner Nationalism Essay Full Essay

Although they have different connotations, these terms are somewhat interchangeable. The National Party represented all South African interests prior to Apartheid as a party opposing British imperialism. Therefore, nationalists sought complete independence from Britain not just politically (White), but also economically (Autarky) and culturally (Davenport).

Afro-African, black, colored, and Indian were the four main ethnic groups in South Africa during this time period. At the time, the ruling class was made up of white people who spoke Afrikaans: they claimed blacks and coloreds were brought over for work involuntarily during settler-colonialism, so they did not have a history or culture. Therefore, Afrikaner nationalism served as a preservationist ideology (Davenport) for the white heritage.

South African History

Increasing participation of Indian people in government and politics indicates that Afrikaner nationalism is becoming more inclusive as Indians are recognized as South Africans.

During Apartheid, white South Africans spoke Afrikaans, a language derived from Dutch. As an official language of South Africa, Afrikaner has become an increasingly common term to describe both an ethnic group and its language.

The Afrikaans language was developed by the poor white population as an alternative to the standard Dutch language. Afrikaans was not taught to black speakers during Apartheid, which resulted in it being renamed Afrikaner instead of Afrikaans.

The Het Volk party (Norden) was founded by D.F. Malan as a coalition among Afrikaner parties, such as the Afrikaner bond and Het Volk. The United Party (UP) was formed by J.B.M. Hertzog in 1939 after he broke away from his more liberal wing to form three consecutive NP governments from 1924 to 1939.

Black South Africans were lobbied successfully for more rights during this period by the opposition United Party, which eliminated racial segregation into separate spheres of influence known as Grand Apartheid, which meant whites could control what blacks did in their segregated neighborhoods (Norden).

National Party

South Africans were classified into racial groups based on their appearance and socio-economic status under the Population Registration Act enacted by the NP after defeating the United Party in 1994. In order to build a strong base of support for its political party, the NP joined forces with the Afrikanerbond and Het Volk.

It was founded in 1918 to address inferiority complexes created by British imperialism (Norden) among Afrikaners by “ruling and protecting” them. It was exclusively white people who joined the Afrikaner bond since they were only interested in shared interests: language, culture, and political independence from the British.

Afrikaans was officially recognized as one of the official languages of South Africa in 1925 by the Afrikaner bond, which established the Afrikaanse Taal-en Kultuurvereniging. Also, the NP began supporting cultural activities such as concerts and youth groups in order to bring Afrikaners under one banner (Hankins) and mobilize them into a cultural community.

There were factions within the National Party that were based on socioeconomic class differences, rather than being a monolithic body: some members recognized that they needed more grassroots support to win the 1948 elections.

You may also read below mentioned other essays from our website for free,

Essay on Bantu Education Act In English For Free

- Essay on Education Goals In English

Afrikaner Nation

By promoting Christian nationalism to South Africans, the National Party encouraged citizens to respect rather than fear their differences, thus gaining votes from Afrikaners (Norden). The ideology could be considered racist since no equality was recognized between races; rather, it advocated controlling the region assigned to blacks without integrating them into other groups.

As a result of Apartheid, black and white residents were segregated politically and economically. Because whites could afford better housing, schools, and travel opportunities, segregation became an institutionalized socioeconomic system that favored rich whites (Norden).

By gaining the Afrikaner population vote in 1948, the National Party slowly came to power despite early opposition to Apartheid. They officially established Apartheid one year after winning the election, as a federal law allowing white South Africans to participate in political representation without the right to vote (Hankins).

In the 1950s, under Prime Minister Dr. NP, this harsh form of social control was implemented. By replacing English with Afrikaans in schools and government offices, Hendrik Verwoerd paved the way for the development of an Afrikaner culture where white people celebrated their differences rather than hid them (Norden).

A mandatory identification card was also issued by the NP to blacks at all times. Due to the lack of a valid permit, they were prohibited from leaving their designated region.

A system of social control was designed to control the black movement by white police officers, causing natives to be afraid of traveling into areas that were assigned to other races (Norden). As a result of Nelson Mandela’s refusal to submit to minority rule by whites, his ANC became involved in resistance movements against Apartheid.

Through the creation of bantustans, the nationalist movement maintained Africa’s poverty and prevented its emancipation. Despite living in a poor region of the country, southern Africa people had to pay taxes to the white government (Norden) because bantustans were lands specifically reserved for black citizens.

As part of the NP’s policies, blacks were also required to carry identity cards. In this way, police were able to monitor their movement and arrest them if they entered another race’s designated area. “Security forces” took control of townships where blacks protested unfair government treatment and were arrested or killed.

Besides being denied representation in Parliament, black citizens received significantly fewer educational and medical services than whites (Hankins). Nelson Mandela became the first president of a fully democratic South Africa in 1994 after the NP ruled apartheid-era South Africa from 1948 to 1994.

A majority of NP members were Afrikaners who believed that British imperialism had “ruined” their country after World War II due to British imperialism (Walsh). Also, the National Party used ‘Christian Nationalism’ to win Afrikaner people votes by claiming that God created the world’s races and must therefore be respected rather than feared (Norden).

Nevertheless, this ideology could be viewed as racist since it did not recognize equality between races; it merely argued that blacks should remain independent within their assigned regions rather than integrate with others. Due to the NP’s complete control over Parliament, black Citizens were not oblivious to apartheid’s unfairness but were powerless to address it.

As a result of British imperialism after the first world war, Afrikaners overwhelmingly supported the National Party. This party sought to create a separate culture where whites would have sole responsibility for government. Architect of apartheid Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd promoted intense segregation between blacks and whites during his Prime Ministership between 1948 and 1952.

The Nordics believed that differences should be embraced rather than feared because there are irreconcilable differences in which one group will always dominate. Although Hankins suggested black citizens remain in their bantustans rather than integrating with other cultures (Hankins), he failed to recognize these ‘irreconcilable’ groups as equals.

In addition to requiring blacks to carry identity cards, the NP passed laws to make them do so. The police were able to monitor their movements more easily as a result. If caught crossing into an area designated for another race, they were arrested.

Nelson Mandela was elected as South Africa’s first black president (Norden) on April 27th, 1994, marking the end of apartheid. In his speech after becoming president, Mandela explicitly stated that he had no intention of disparaging Afrikaners. He instead sought to enhance the positive aspects while reforming “the less desirable aspects of Afrikaner history” (Hendricks).

When it came to apartheid’s sins, he advocated Truth and Reconciliation rather than retribution, allowing all sides to discuss what happened without fear of punishment or retaliation.

Mandela, who helped create the new ANC government after losing the election, did not dissolve the NP but rather promoted reconciliation between Afrikaners and non-Afrikaners by bringing Afrikaner culture and traditions to the forefront of racial reconciliation.

Despite their ethnicities, South Africans were able to watch rugby games together because the sport became a unifying factor for the nation. The black Citizens who played sports watched television, and read newspapers without fear of persecution were Nelson Mandela’s hope for them (Norden).

Apartheid was abolished in 1948, but Afrikaners were not fully eliminated. While the interracial sport does not necessarily mean the NP is no longer ruling the country, it does bring hope for future South African generations to be able to reconcile with their past rather than live in fear.

South African blacks are less likely to perceive whites as oppressors because they are more involved in Afrikaner culture. Once Mandela is out of office, it will be easier to achieve peace between blacks and whites. Aiming to build better relationships between races is more important now than ever before, as Nelson Mandela will retire on June 16th, 1999.

Under Nelson Mandela’s administration, Afrikaners once again felt comfortable with their status in society because the white government was brought into the 21st century. President Jacob Zuma is almost certain to be reelected to South Africa’s top job in 2009 as the leader of the ANC (Norden).

Conclusion,

Since the NP had a plurality of power based on support from Afrikaner voters, they were able to retain control over Parliament until they lost their election; thus, whites were worried that voting for another party would lead to more power for blacks, which would lead to a loss of white privilege due to affirmative action programs if they voted for another party.

Long & Short Essay on Rainy Season in English

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Trending Topics

- Hersh Goldberg-Polin

Get JTA in your inbox

By submitting the above I agree to the privacy policy and terms of use of JTA.org

At the Jerusalem synagogue where Hersh Goldberg-Polin danced in life, grief and anger reign after his death

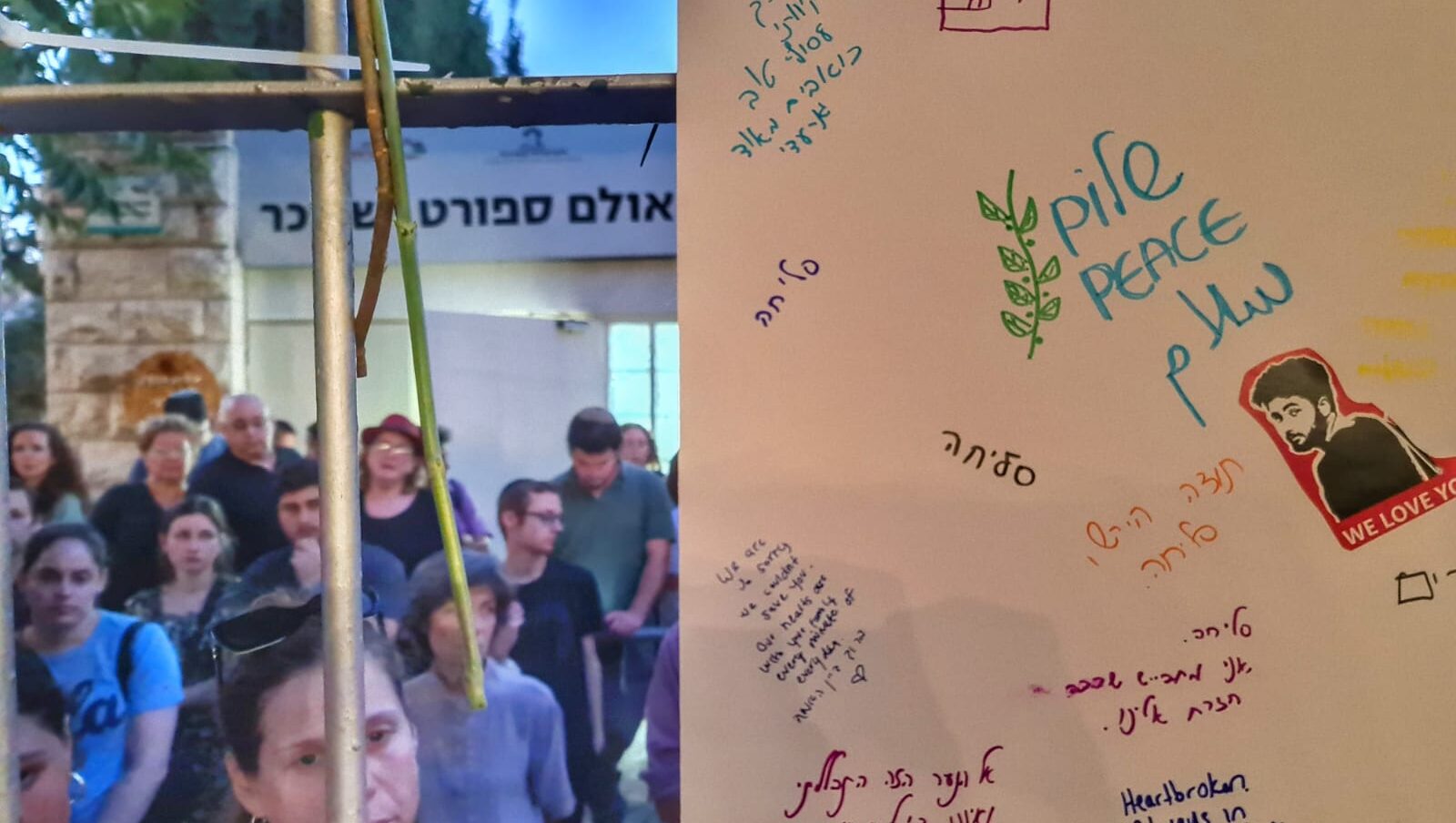

JERUSALEM — Three hundred and thirty-two days after Hersh Goldberg-Polin danced in the courtyard next to his Jerusalem synagogue on the holiday of Simchat Torah, more than a thousand people gathered there in grief and prayer to mourn his murder by Hamas terrorists in Gaza.

During the Sunday night vigil, the courtyard railings were lined with oversized yellow ribbons to symbolize advocacy for the hostages, Hapoel Jerusalem soccer flags — the 23-year-old’s favorite team — and posters that read, “We love you, stay strong, survive,” a mantra coined by his mother, Rachel Goldberg-Polin.