- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 25 September 2011

Awareness and knowledge of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) among school-going adolescents in Europe: a systematic review of published literature

- Florence N Samkange-Zeeb 1 ,

- Lena Spallek 1 &

- Hajo Zeeb 1

BMC Public Health volume 11 , Article number: 727 ( 2011 ) Cite this article

140k Accesses

92 Citations

19 Altmetric

Metrics details

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) are a major health problem affecting mostly young people, not only in developing, but also in developed countries.

We conducted this systematic review to determine awareness and knowledge of school-going male and female adolescents in Europe of STDs and if possible, how they perceive their own risk of contracting an STD. Results of this review can help point out areas where STD risk communication for adolescents needs to be improved.

Using various combinations of the terms "STD", "HIV", "HPV", "Chlamydia", "Syphilis", "Gonorrhoea", "herpes", "hepatitis B", "knowledge", "awareness", and "adolescents", we searched for literature published in the PubMed database from 01.01.1990 up to 31.12.2010. Studies were selected if they reported on the awareness and/or knowledge of one or more STD among school-attending adolescents in a European country and were published in English or German. Reference lists of selected publications were screened for further publications of interest. Information from included studies was systematically extracted and evaluated.

A total of 15 studies were included in the review. All were cross-sectional surveys conducted among school-attending adolescents aged 13 to 20 years. Generally, awareness and knowledge varied among the adolescents depending on gender.

Six STDs were focussed on in the studies included in the review, with awareness and knowledge being assessed in depth mainly for HIV/AIDS and HPV, and to some extent for chlamydia. For syphilis, gonorrhoea and herpes only awareness was assessed. Awareness was generally high for HIV/AIDS (above 90%) and low for HPV (range 5.4%-66%). Despite knowing that use of condoms helps protect against contracting an STD, some adolescents still regard condoms primarily as an interim method of contraception before using the pill.

In general, the studies reported low levels of awareness and knowledge of sexually transmitted diseases, with the exception of HIV/AIDS. Although, as shown by some of the findings on condom use, knowledge does not always translate into behaviour change, adolescents' sex education is important for STD prevention, and the school setting plays an important role. Beyond HIV/AIDS, attention should be paid to infections such as chlamydia, gonorrhoea and syphilis.

Peer Review reports

Over the period 1985-1996, a general decrease of gonorrhoea, syphilis and chlamydia infections was noted in developed countries, both in the general population and among adolescents [ 1 ]. From the mid-1990s however, increases in the diagnoses of sexually transmitted diseases, in particular syphilis, gonorrhoea and chlamydia have been reported in several European countries, especially among teenagers 16-19 years old [ 2 – 7 ].

The problem with most STDs is that they can occur symptom-free and can thus be passed on unaware during unprotected sexual intercourse. On an individual level, complications can include pelvic inflammatory diseases and possibly lead to ectopic pregnancies and infertility [ 8 – 11 ]. Female adolescents are likely to have a higher risk of contracting an STD than their male counterparts as their partners are generally older and hence more likely to be infected [ 2 , 12 ].

The declining age of first sexual intercourse has been proffered as one possible explanation for the increase in numbers of STDs [ 7 ]. According to data from different European countries, the average age of first sexual intercourse has decreased over the last three decades, with increasing proportions of adolescents reporting sexual activity before the age of 16 years [ 13 – 18 ]. An early onset of sexual activity not only increases the probability of having various sexual partners, it also increases the chances of contracting a sexually transmitted infection [ 19 ]. The risk is higher for female adolescents as their cervical anatomic development is incomplete and especially vulnerable to infection by certain sexually transmitted pathogens [ 20 – 23 ].

The reluctance of adolescents to use condoms is another possible explanation for the increase in STDs. Some surveys of adolescents have reported that condoms were found to be difficult to use for sexually inexperienced, detract from sensual pleasure and also embarrassing to suggest [ 24 – 26 ]. Condoms have also been reported to be used primarily as a protection against pregnancy, not STD, with their use becoming irregular when other contraceptives are used [ 15 , 27 ]. Furthermore, many adolescents do not perceive themselves to be at risk of contracting an STD [ 27 ].

We conducted this systematic review in order to determine awareness and knowledge of school-going adolescents in Europe of sexually transmitted diseases, not only concerning HIV/AIDS, but also other STDs such as chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis and human papillomavirus (HPV). Where possible we will identify differences in awareness and knowledge by key demographic variables such as age and gender, and how awareness has changed over time.

Although knowledge and awareness have been reported to have a limited effect on changing attitudes and behaviour, [ 16 , 28 – 30 ] they are important components of sex education which help promote informed, healthy choices [ 31 – 33 ]. As schooling in Europe is generally compulsory at least up to the age of 15 years [ 34 ] and sex education is part of the school curriculum in almost all European countries, school-going adolescents should be well informed on the health risks associated with sexual activity and on how to protect themselves and others. In view of the decreasing age of sexual debut and the reported increasing numbers of diagnosed STDs among young people, results of our review can help point out areas where STD risk communication for school-attending adolescents needs to be improved.

Search strategy

We performed literature searches in PubMed using various combinations of the search terms "STD", "HIV", "HPV", "chlamydia", "syphilis", "gonorrhoea", "herpes", "hepatitis B", "knowledge", "awareness", and "adolescents". The reference lists of selected publications were perused for further publications of interest. The search was done to include articles published from 01.01.1990 up to 31.12.2010. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were specified in advance and documented in a protocol (Additional File 1 ).

Inclusion criteria

Studies were selected if they reported on awareness and/or knowledge of one or more sexually transmitted disease(s) among school-attending adolescents in a European country, or in Europe as a whole, and were published in English or German.

Exclusion criteria

Case reports, reviews, editorials, letters to the editor, expert opinions, studies on sexual activity/behaviour only, studies evaluating intervention programmes and studies not specifically on school-attending adolescents were excluded.

Methodological assessment of reviewed studies

We used a modified version of the Critical Appraisal Form from the Stanford School of Medicine to assess the methodology of the studies included in the review [ 35 ]. The studies were classified according to whether or not they fulfilled given criteria such as 'Were the study outcomes to be measured clearly defined?', 'Was the study sample clearly defined?', or 'Is it clear how data were collected?' (Table 1 ). No points were allocated. Instead, the following categorisations could be selected for each assessment statement: 'Yes', 'Substandard', 'No', 'Not Clear', 'Not Reported', 'Partially Reported', 'Not Applicable', 'Not Possible to Assess', 'Partly'. The assessment was done independently by two of the authors (FSZ, LS) who then discussed their findings.

Definition of awareness and knowledge

For the purpose of this review studies were said to have assessed awareness if participants were merely required to identify an STD from a given list or name an STD in response to an open question. Knowledge assessment was when further questions such as on modes of transmission and protection were posed.

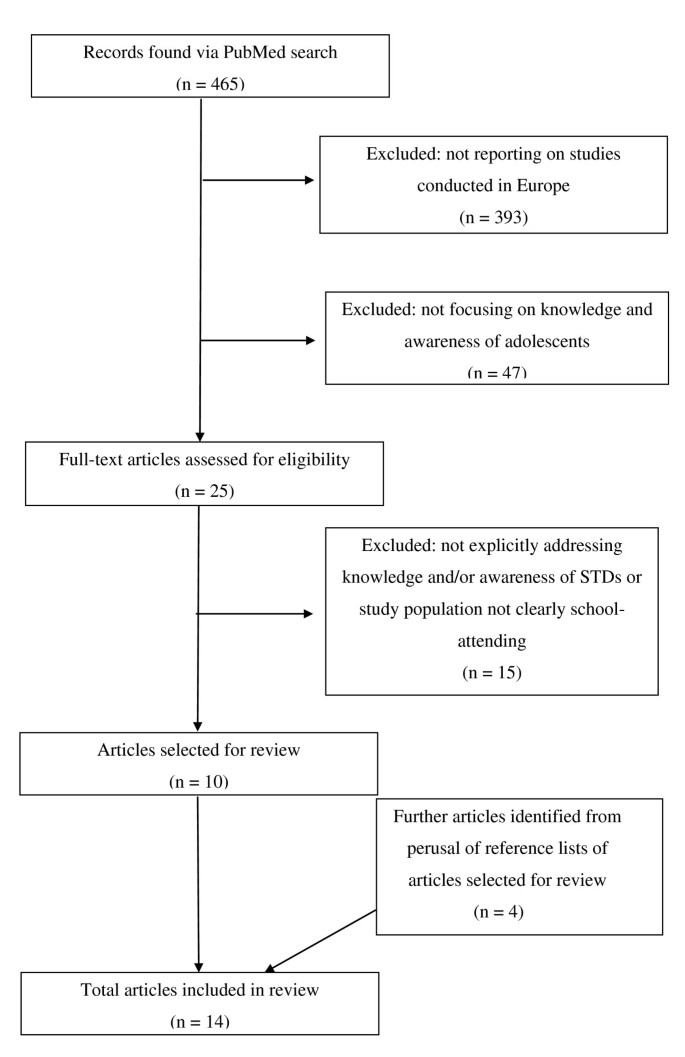

Overall, 465 titles and abstracts were obtained from the searches conducted. Three hundred and ninety-three articles were excluded as they did not report on studies conducted in Europe (Figure 1 ). A further 47 were excluded as they did not focus on knowledge and awareness of adolescents. Of the 25 identified articles dealing with knowledge on STDs among adolescents in Europe, 8 were excluded as they either did not specifically address the question of knowledge and/or awareness, or focused more on sexual behaviour/beliefs. A further seven articles were excluded because the study population was not clearly stated to be school-attending.

Flow diagram showing selection process of articles included in the review .

A review of the references listed in the 10 articles meeting inclusion criteria yielded four additional relevant articles. One article reported on two studies, hence a total of 15 studies published from 1990-2000 were included in the systematic review.

Six of the articles were published before the year 2000 [ 36 – 41 ], and nine after 2000 [ 42 – 49 ]. The studies report on surveys conducted from as early as 1986 to 2005 (Table 2 ).

The majority of the 15 studies specifically focused on HIV/AIDS only (7 studies) [ 36 , 39 , 41 , 43 , 44 , 49 ], four on STDs in general [ 37 , 38 , 40 , 42 ], one on STDs in general with focus on HPV [ 47 ], and three on HPV only [ 45 , 46 , 48 ]. All the HPV studies were published after the approval and market introduction of the HPV vaccine in 2006.

Generally the studies were conducted in particular regions/towns in different countries, with only one being conducted across three towns in three different countries (Russia, Georgia and the Ukraine) [ 43 ]. Six of the studies were conducted in Sweden [ 37 , 38 , 40 , 41 , 46 , 47 ] two in Russia [ 39 , 43 ] and one each in Ireland, [ 36 ] England, [ 42 ] Croatia, [ 44 ] Finland, [ 45 ] Italy [ 48 ] and Germany [ 49 ] (Table 2 ).

In the studies, generally both male and female adolescents varying in age from 13-20 years were surveyed. One study surveyed females only [ 40 ] and adolescents 11-12 years old were included in only one study [ 49 ] (Table 2 ). Whereas most of the studies included assessed awareness and knowledge among boys and girls separately, only one study [ 48 ] specifically assessed the association between age and awareness/knowledge.

Methodological summary of studies included in the review

All studies included in the review were cross-sectional in design. Apart from one study which recruited pupils by mailing the questionnaire to all households with adolescents in the 9 th grade, [ 45 ] pupils were recruited via schools. For 8 of the 15 studies it could not be deduced from the methods section how the participating schools were selected and in 4 studies it was not clear how the participating pupils were selected. The pupils completed questionnaires in school in 10 studies, and in two the questionnaires were completed at home [ 45 , 48 ]. Face-to-face interviews were used only in the surveys by Andersson-Ellström et al. [ 40 ] and by Goodwin et al. [ 43 ] (Table 2 ).

The study outcomes were clearly defined in all studies and the topics on which questions were posed were clearly described in all but one study. The majority of the studies also reported the individual questions posed to assess the given outcomes. In six studies the authors did not mention whether the instruments used for data collection had been pre-tested, validated, or whether the questions posed had been used in previous surveys (Table 1 ). Of the 9 studies which clearly reported participation rates, 7 had participation rates ranging from 79% to 100%. The remaining two studies had participation rates of 21.5% and 58% (Table 2 ).

Six STDs were focussed on in the studies included in the review, with awareness and knowledge being assessed in depth mainly for HIV/AIDS and HPV,[ 36 , 41 – 43 , 46 – 49 ] and to some extent for chlamydia [ 37 , 38 , 42 , 47 ]. For syphilis, gonorrhoea and herpes, only awareness was assessed in four studies [ 37 , 38 , 42 , 47 ].

Awareness and knowledge of HPV

The reported awareness of HPV among the surveyed adolescents was generally low (identification from given list), ranging from 5.4% in the study by Höglund et al. [ 47 ] to 66% in the study by Pelucchi et al. [ 48 ]. In the two studies which also reported results for females and males separately, awareness was observed to be statistically significantly higher among females than among males: 16.4% vs. 9.6% in the Swedish study by Gottvall et al. [ 46 ] and 71.6% vs. 51.2% in the Italian study by Pelucchi et al. [ 48 ]. In the study by Höglund et al., only one of the participating 459 adolescents mentioned HPV (in response to an open question on known STDs) [ 47 ].

Awareness of the HPV vaccine was also very low, with 5.8% and 1.1% of adolescents surveyed in the studies by Gottvall et al. and Höglund et al. respectively, reporting being aware of the vaccine [ 46 , 47 ]. Whereas only 2.9% and 9.2% of adolescents in these two Swedish studies were aware that HPV is sexually transmitted, the proportion was 60.6% in the Italian study [ 48 ]. A minority of adolescents knew that HPV is a risk factor for cervical cancer: 1.2% in the study by Höglund et al. [ 47 ] and 8.1% in the study by Gottvall et al. [ 46 ]. Among the adolescents who participated in the survey by Pelucchi et al., 48.6% were aware that the aim of the HPV vaccine is to prevent cervical cancer [ 48 ]. Among female adolescents who participated in the study by Gottvall et al., 11.8% did not believe they would be infected with HPV [ 46 ]. The proportion was 55% among female participants in the study by Pelucchi et al. [ 48 ]. The latter study surveyed pupils aged 14-20 years but did not report on age differences in awareness.

Three studies reported on awareness of condylomata, genital warts which are caused by the human papilloma virus. Two of the studies reported awareness of 35% [ 38 ] and 43% [ 37 ]. The third study mentioned that awareness of condylomata was lower than that for chlamydia without stating the corresponding figures [ 40 ].

Awareness and knowledge of HIV/AIDS

Knowledge and awareness was quite high in all studies reporting on HIV/AIDS, with more than 90% of adolescents being able to identify the disease as an STD from a given list or in response to the direct question "Have you ever heard of HIV/AIDS?" [ 36 , 38 , 42 ]. In one study where the open question "Which STDs do you know or have you heard of?" was used, 88% of respondents mentioned HIV/AIDS [ 47 ] (Table 3 ).

In the studies where this was asked, a large majority of the adolescents knew that HIV is caused by a virus, [ 36 , 41 ] is sexually transmitted,[ 36 , 41 , 43 , 47 , 49 ] and that sharing a needle with an infected person may lead to infection with the virus [ 36 , 41 , 43 , 49 ]. Statistically significant age specific differences in knowledge on mode of HIV-transmission were reported in the study conducted in Germany [ 49 ]. Compared to 13 and 15 year old pupils, a higher proportion of 14 year old pupils correctly identified the level of risk of HIV-transmission associated with bleeding wounds, intravenous drug use and sexual contact. For the latter mode of transmission, the lowest proportion of correct answers was observed among 16 year old pupils. Generally the proportion of respondents correctly reporting that use of condoms helps protect against contraction of HIV was above 90%. The only exception was in the Russian study conducted by Lunin et al. in 1993, in which only 42% of females and 60% of males were aware of this fact [ 39 ]. In the same study, only 15% of the adolescents perceived themselves 'not at risk' of contracting HIV (Table 3 ).

Only one study reported asking the adolescents if one can tell by looking at someone if they have HIV, to which 47% responded affirmatively [ 43 ].

Awareness and knowledge of chlamydia

The proportion of adolescents able to identify chlamydia as an STD from a list of diseases ranged from 34% in the study conducted in England by Garside et al. [ 42 ] to 96% in the Swedish study by Andersson-Ellström et al. [ 22 ]. In the Garside study, the proportion was higher among year 9 than among year 11 pupils (p < 0.05). In another Swedish study by Höglund et al. 86% of the surveyed adolescents mentioned chlamydia as one of the STDs known to them in response to an open question [ 47 ]. In the two studies which reported on awareness among boys and girls separately, girls were observed to have higher awareness proportions than boys [ 38 , 42 ]. While the observation was not statistically significant in one of the studies, [ 27 ] this was not reported on in the other study [ 38 ].

Not many adolescents knew that chlamydia can be symptom-free: 40% and 56% in the 1986 and 1988 surveys by Andersson-Ellström et al. [ 37 ] and 46% in the study by Höglund et al. [ 47 ]. In one Swedish study where the level of knowledge in the same study population was assessed at age 16 and 18, a statistically significant increase in knowledge was observed over time [ 40 ]. Only the Finish study reported on the subjective rating of risk of contracting chlamydia. 55% of the adolescents surveyed reported 'low perceived susceptibility' [ 45 ] (Table 3 ).

Awareness and knowledge of gonorrhoea

Gonorrhoea was identified as an STD from a given list by 84% of adolescents in the survey by Tyden et al.,[ 38 ] by 98% in the survey by Andersson-Ellström et al.,[ 37 ] and by 53% in the survey by Garside et al. [ 42 ]. In the latter, the difference between year 9 and year 11 pupils was more pronounced among boys: 53% among year 9 and 60% among year 11 (p > 0.05). A statistically significant increase in knowledge over time was observed in a group of girls surveyed at age 16 and 18 [ 40 ]. Only 50% of the adolescents surveyed in the study by Höglund et al. mentioned gonorrhoea in response to an open question on known STDs [ 47 ] (Table 3 ).

Awareness of syphilis and herpes

Awareness of syphilis was surveyed only in the study conducted in England where 45% of the participating adolescents correctly identified the disease from a given list as an STD. The proportion was slightly higher among year 11 compared to year 9 pupils and awareness was slightly higher among girls than among boys (p > 0.05) [ 42 ] (Table 3 ).

In the Tyden et al. study, [ 38 ] 56% of the surveyed adolescents identified herpes as an STD from a given list. The proportion was 90% in the survey by Andersson-Ellström et al. [ 37 ] and 59% in the Garside et al. study [ 42 ]. In the latter, considerable differences were observed between year 9 and year 11 pupils (p < 0.05), but not between girls and boys in the same school year. Herpes was mentioned as an STD by 64% of the adolescents surveyed in the study by Höglund et al. [ 47 ] (Table 3 ).

Awareness of STDs in general

Five of the studies reviewed assessed the knowledge of participating adolescents on STDs in general. In the England study, all in all 59.7% of the participants knew that STDs in general can be symptom-free [ 42 ]. Among girls, knowledge was higher among year 11 than year 9 pupils, while the opposite was true for boys. The proportion of boys in year 9 who knew this fact (64.2%) was considerably higher than that of year 9 girls (53.8%) (Table 3 ). In two Swedish studies by Tyden et al. and by Andersson-Ellström et al., all surveyed adolescents knew that the use of condoms can protect against the contraction of STDs in general [ 38 , 40 ]. In an earlier study by Andersson-Ellström et al., 20% of sexually active pupils surveyed in 1986 were aware that condoms protect against infection. The figure significantly went up to 43% in 1988, with boys having significantly higher awareness than girls in both years [ 22 ] (Table 3 ). In the same study, the proportion of girls who felt themselves to be at risk of contracting an STD in general went down from 32% in the 1986 survey to 24% in the 1988 survey. Among boys, the proportion increased from 16% in 1986 to 24% in 1988. These changes were not statistically significant [ 37 ]. In the Finish study, 55% of the surveyed adolescents perceived themselves to be at low risk of contracting an STD [ 45 ].

Reported use of condoms

Use of condoms by sexually active participants was assessed in three studies, all conducted in Sweden [ 38 , 46 , 47 ]. Reported use at sexual debut was lowest in the study published in 1991 (31%), [ 38 ] and higher in the other studies both published in 2009: 61% [ 47 ] and 65% [ 46 ] respectively (Table 3 ). In the earlier study, the proportion of girls reporting condom use was, at 50%, considerably higher than that of boys (40%) [ 38 ]. In the study by Gottvall et al., no difference in condom use was observed between girls and boys [ 46 ]. Condom use at recent coitus was reported on only in the earlier study [ 38 ]. It was observed that the decrease in the proportion of girls reporting using condoms was more pronounced than that of boys (26% vs. 40%) (Table 3 ).

The highest awareness and knowledge were reported for HIV/AIDS. This is certainly linked to the fact that since the mid 1980s, extensive awareness campaigns on this topic have been conducted globally. The lowest proportions were reported for HPV, with awareness as low as 5.4% in one study [ 47 ]. With only about 1 in 8 respondents knowing that HPV is an STD, awareness was still very low in one of the two studies conducted after the introduction of the HPV vaccine [ 46 ]. A higher awareness (66.6% of respondents aware), measured in a different population, was observed in the second recent study on HPV [ 48 ].

Two factors appeared to have influenced awareness. The first was of a methodological nature and related to the fact whether an open or closed question was posed. Of the studies included in the review which assessed awareness, all but one used closed-form questions only. The adolescents either had to identify sexually transmitted diseases from a given list of diseases, or the question was in a yes/no format. Initially, Höglund et al. asked participating adolescents to list all STDs known to them and then later on, if they had ever heard of HPV. Only one participant (0.2%) mentioned HPV as one of the STDs known to them, but later, 24 (5.4%) reported to have heard of HPV [ 47 ]. In comparison to open-form questions, closed questions are not only more practical and easier to respond to, but also easier to code and analyse. One of the arguments raised against closed questions, especially where a list of possible answers is given, is the risk of guesswork. It can not be ruled out that some participants, unable to answer the question, will select answers at random [ 50 , 51 ]. In the study by Garside et al. for example, among year 9 pupils, 14.5% incorrectly identified plasmodium, and 20.6% filariasis from a given list as STDs [ 42 ]. Open questions have been recommended for surveying participants with unknown or varying knowledge/awareness [ 50 ] as these questions provide a more valid picture of the state of knowledge [ 51 ].

To a lesser extent, gender also appears to have influenced knowledge and awareness, especially for HPV [ 46 , 48 ]. Significant gender differences were observed, with females having better awareness and knowledge than males. Although the data are limited as not all studies reported results separately for males and females, these findings, could be reflective of the way awareness campaigns, for example on HPV, have been targeted more at females than at males.

The studies on HIV included in our review generally reported high awareness of the protective effect of condoms among adolescents [ 36 , 41 , 43 , 47 , 49 ]. One study included in the review however observed that adolescents seem to regard condoms primarily as a method of contraception and not as a means of protection against sexually transmitted diseases (40). In this study, 19 out of 20 female adolescents who reported more than 4 sexual partners at the age of 18 reported intercourse without a condom in relationships of less than 6 months' duration. The majority of them were, however, convinced that they had neither acquired (96%) nor transmitted (93%) an STD at last unprotected intercourse [ 40 ]. Other studies also indicate that consistent condom use is generally low among adolescents [ 27 , 52 – 55 ].

Where reported, participation rates were generally high, probably due to the fact that the adolescents were recruited in schools. In some instances however, the number of participants was low even though the participation rate was reported as high. In the study by Tyden et al. for example, the study sample consisted of 213 pupils, 12% of the 1830 students in the first form of upper secondary school in Uppsala [ 38 ]. The authors base the participation rate of their study (98%) on the 12%, without explaining how it came about that only 213 pupils were considered for participation. The one study which recruited participants per post had a very low participation rate of 21.5% [ 45 ]. Nevertheless, the study had more participants than others with comparatively higher participation rates. Bias related to selective participation is an issue that needs to be considered on a study by study basis, and reporting on response proportions should be considered essential for all studies.

Study strengths and limitations

To our knowledge no systematic reviews of published literature on knowledge and awareness of sexually transmitted diseases among school-attending adolescents in Europe have been conducted to date. The current review confirms that there are considerable gaps in knowledge and awareness on major STDs in European adolescents. Our results underline the importance of the objectives set for adolescents' sexual and reproductive health in Europe, the first of which foresees that adolescents be informed and educated on all aspects of sexuality and reproduction [ 31 ].

We could not identify many studies on knowledge and awareness of sexually transmitted diseases among school-attending adolescents in Europe. This could be due to the fact that knowledge has been shown to have little impact on behaviour change, and prevention interventions have generally moved away from a focus on knowledge and awareness as key mediators. Another possible reason is that schools are not always willing to participate in such studies due to competing demands of other school activities or because of the subject content [ 16 , 28 – 30 ].

One limitation of our review is that the 15 studies included did not all focus on the same sexually transmitted diseases. The four studies conducted in Eastern Europe were all on HIV/AIDS knowledge and awareness only, whereas Western European studies were on STDs in general or on HPV. Furthermore, the formulation of the questions used to assess awareness and knowledge varied between studies, making it difficult to directly compare the findings of individual studies. Another potential limiting factor is the age variation of participants in the studies included in the review, especially as all but one study did not clearly investigate the association between age and awareness or knowledge. Due to the afore-mentioned factors and the small number of studies available, it was not possible to perform a meta-analysis of the study findings.

The representativeness of study participants in some studies could not be assessed as it was not mentioned how the schools were selected [ 37 , 40 – 44 , 49 ]. Different socioeconomic environments of individual schools are likely to affect results, but there is currently not sufficient information to assess this.

The school setting offers an effective way to access adolescent populations universally, comprehensively and uniformly [ 56 ]. It plays an important role for sex education, especially for those adolescents with no other information sources. Furthermore, some parents are not comfortable discussing sexual issues with their children. It therefore comes as no surprise that many young people cite the school as an important source of information about sexually transmitted diseases [ 26 , 27 ]. Although sex education is part of the school curriculum in many European countries, there are differences in the issues focused on. In some countries sex education is integrated in life skills approach, whilst biological issues are predominant in others and at times the focus is on HIV/AIDS prevention [ 57 ]. Generally it seems that education schedules offer a range of opportunities to raise knowledge and awareness of STD among adolescents.

In general, the studies reported similar low levels of knowledge and awareness of sexually transmitted diseases, with the exception of HIV/AIDS. Although, as shown by some of the findings on condom use, knowledge does not always translate into behaviour change, adolescents' sex education is important for STD prevention, and the school setting plays an important role. Beyond HIV/AIDS, attention should be paid to infections such as chlamydia, gonorrhoea and syphilis.

World Health Organisation: Global prevalence and incidence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections. 2001, WHO, Geneva

Google Scholar

Panchaud C, Singh S, Feivelson D, Darroch JE: Sexually transmitted diseases among adolescents in developed countries. Fam Plan Persp. 2000, 32: 24-32 &45. 10.2307/2648145.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Berglund T, Fredlund H, Giesecke J: Epidemiology of the re-emergence of gonorrhoea in Sweden. Sex Transm Dis. 2001, 111-114.

Health protection Surveillance Centre.: Surveillance of STI. A report by the Sexually Transmitted Infections subcommittee for the Scientific Advisory committee of the health Protection Surveillance Centre. December 2005,

Nicoll A, Hamers FF: Are trends in HIV, gonorrhoea and syphilis worsening in Western Europe?. BMJ. 2002, 324: 1324-1327. 10.1136/bmj.324.7349.1324.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Twisselmann B: Rising trends of HIV, gonorrhoea, and syphilis in Europe make case for introducing European surveillance systems. Euro Surveill. 2002, 6 (23): pii = 1952-Last accessed 30.11.2010, [ http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=1952 ]

Adler MW: Sexually transmitted infections in Europe. Eurohealth. 2006, 12: 3-6.

PHLS, DHSS & PS and the Scottish ISD(D)5 Collaborative Group: Trends in Sexually Transmitted Infections in the United Kingdom 1990-1999. 2000, Public Health Laboratory Service London

Stamm W, Guinan M, Johnson C: Effect of treatment regiments for Neisserie gonorrhoea on simultaneous infections with Chlamydia trachomatis. New Eng J Med. 1984, 310: 545-559. 10.1056/NEJM198403013100901.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

MacDonald NE, Brunham R: The Effects of Undetected and Untreated Sexually Transmitted Diseases: Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Ectopic Pregnancy in Canada. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 1997, 6 (2): Special Issue: STDs and Sexual/Reproductive Health-

Simms I, Stephenson JM: Pelvic inflammatory disease epidemiology; What do we know and what do we need to know?. Sex Trans Inf. 2000, 76: 80-87. 10.1136/sti.76.2.80.

Bozon M, Kontula O: Sexual initiation and gender in Europe. Sexual behavior and HIV/AIDS in Europe. Edited by: M Hubert, N Bajos, and T Sandfort. 1998, London: UCL Press, 37-67.

Kangas I, Andersen B, McGarrigle CA, Ostergaad L: A comparison of sexual behaviour and attitudes of healthy adolescents in a Danish high school in 1982, 1996 and 2001. Pop Health Metr. 2004, online publication: last accessed 03.12.2010, [ http://www.pophealthmetrics.com/content/2/1/5 ]

Ross J, Godeau E, Dias S: Sexual health. Young people's health in context. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HSBC) study: International report from the 2001/2002 survey. Edited by: Currie C, Roberts C, Morgan A, et al. 2004, Copenhagen: WHO

Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung: Jugendsexualität. Repräsentative Wiederholungsbefragung von 14- bis 17-Jährigen Jugendlichen und ihren Eltern. 2006, BZgA

Tucker JS, Fitzmaurice AE, Imamura M, Penfold S, Penney GC, van Teijlingen E, Schucksmith J, Philip KL: The effect of the national demonstration project Healthy Respect on teenage sexual health behaviour. Eur J Public Health. 2006, 17 (1): 33-41. 10.1093/eurpub/ckl044.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Godeau E, Gabhainn SN, Vignes C, Ross J, Boyce W, Todd J: Contraceptive use by 15-year-old students at their last sexual intercourse: Results from 24 countries. Arch Paediatr Adolesc Med. 2008, 162: 66-73. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.8.

Article Google Scholar

Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung: Sexualität und Migration: Milieuspezifische Zugangswege für die Sexualaufklärung Jugendlicher. Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Untersuchung der Lebenswelten von 14- bis 17-Jährigen Jugendlichen mit Migrationshintergrund. 2010, BZgA,

Heinz M: Sexuell übertragbare Krankheiten bei Jugendlichen: Epidemiologische Veränderungen und neue diagnostische Methoden. 2001, Arbeitsgemeinschaft Kinder-und Jugendgynäkologie e.V, last accessed 03.12.2010, [ http://www.kindergynaekologie.de/html/kora22.html ]

Berrington de González A, Sweetland S, Green J: Comparisons of risk factors for squamous cell and adenocarcinomas of the cervix: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2004, 90: 1787-1791.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Reich O: Is early first intercourse a risk factor for cervical cancer?. Gynäkol Geburtshilfliche Rundsch. 2005, 45: 251-256. 10.1159/000087143.

Gille G, Klapp C: Chlamydia trachomatis infections in teenagers. Der Hautarzt. 2007, 58: 31-37. 10.1007/s00105-006-1265-x.

Hwang LY, Ma Y, Miller Benningfield S, Clayton L, Hanson EN, Jay J, Jonte J, Godwin de Medina C, Moscicki AB: Factors that influence the rate of epithelial maturation in the cervix of healthy young women. J Adolesc Health. 2009, 44 (2): 103-110. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.10.006.

Kegeles SM, Adler NE, Irwin CE: Adolescents and condoms. Am J Dis Child. 1989, 143: 911-915.

Ford N: The AIDS awareness and sexual behaviour of young people in the South-west of England. J Adolesc. 1992, 15: 393-413. 10.1016/0140-1971(92)90071-C.

Persson E, Sandströäm B, Jarlbro G: Sources of information, experiences and opinions on sexuality, contraception and STD protection among young Swedish students. Advances in Contraception. 1992, 8: 41-49. 10.1007/BF01849347.

Editorial team: Young people's knowledge of sexually transmitted infections and condom use surveyed in England. Euro Surveill. 2005, 10 (31): pii = 2766- Last accessed 30.11.2010

Lister-Sharpe D, Chapman S, Stewart-Brown S, Sowden A: Health promoting schools amd health promotion in schools: two systematic reviews. Health Technol Assess. 1999, 3 (22): 1-207.

Wight D, Raab G, Henderson M, Abraham C, Buston K, Hart G, Scott S: Limits of teacher delivered sex education: interim behavioural outcomes from randomised trial. BMJ. 2002, 324: 1-6.

Stephenson J, Strange V, Forrest S, Oakley A, Copas A, Allen E, Babiker A, Black S, Ali M, Monteiro H, Johnson AM: Pupil-led sex education in England (RIPPLE study): cluster randomised intervention trial. Lancet. 2004, 364 (9431): 338-346. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16722-6.

WHO Regional Office for Europe: Who Regional Strategy on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2001, pdf last accessed 17.03.2011, [ http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/69529/e74558.pdf ]

Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung: Country papers on youth sexuality in Europe - Synopsis. 2006, BZgA,

Bobrova N, Sergeev O, Grechukhina T, Kapiga S: Social-cognitive predictors of consistent condom use among young people in Moscow. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005, 37 (4): 174-178. 10.1363/3717405.

European Commission: Compulsory education in Europe 2010/2011. pdf last accessed 10.05.2011, [ http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/education/eurydice/documents/compulsory_education/compulsory_education.pdf ]

Assessing scientific admissibility and merit of published articles: Critical appraisal form. last accessed 08.03.2011, [ http://peds.stanford.edu/Tools/documents/Critical_Appraisal_Form_CGP.pdf ]

Fogarty J: Knowledge about AIDS among leaving certificate students. Irish Med Journal. 1990, 83: 19-21.

CAS Google Scholar

Andersson-Ellström A, Forssman L: Sexually transmitted diseases - knowledge and attitudes among young people. J Adolesc Health. 1991, 12: 72-76. 10.1016/0197-0070(91)90446-S.

Tyden T, Norden L, Ruusuvaara L: Swedish students' knowledge of sexually transmitted diseases and their attitudes to the condom. Midwifery. 1991, 7: 25-30. 10.1016/S0266-6138(05)80131-7.

Lunin I, Hall TL, Mandel JS: Adolescent sexuality in Saint Petersburg, Russia. AIDS. 1995, 9 (suppl 1): S53-S60.

PubMed Google Scholar

Andersson-Ellström A, Forssman L, Milsom I: The relationship between knowledge about sexually transmitted diseases and actual sexual behaviour in a group of teenage girls. Genitourin Med. 1996, 72: 32-36.

Eriksson T, Sonesson A, Isacsson A: HIV/AIDS - information and knowledge: a comparative stud of Kenyan and Swedish teenagers. Scand J Soc Med. 1997, 25: 111-118.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Garside R, Ayres R, Owen M, Pearson VAH, Roizen J: 'They never tell you about the consequences': young people's awareness of sexually transmitted infections. Int J STD & AIDS. 2001, 12: 582-588. 10.1258/0956462011923750.

Goodwin R, Kozlova A, Nizharadze G, Polyakove G: HIV/AIDS among adolescents in Eastern Euorpe: knowledge of HIV/AIDS, social representations of risk and sexual activity among school children and homeless adolescents in Russia, Georgia and the Ukraine. J Health Psych. 2004, 9: 381-396.

Macek M, Matkovic V: Attitudes of school environment towards integration of HIV-positive pupils into regular classes and knowledge about HIV/AIDS: cross-sectional study. Croat Med J. 2005, 26: 320-325.

Woodhall Sc, Lehtinen M, Verho T, Huhtala H, Hokkanen M, Kosunen E: Anticipated acceptance of HPV vaccination at the baseline of implementation: a survey of parental and adolescent knowledge and attitudes in Finland. J Adolesc Health. 2007, 40: 466-469. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.01.005.

Gottvall M, Larsson M, Högkund AT, Tydén T: High HPV vaccine acceptance despite low awareness among Swqedish upper secondary school students. Eur J Contr Repr Health Care. 2009, 14: 399-405. 10.3109/13625180903229605.

Höglund AT, Tydén T, Hannerfors AK, Larsson M: Knowledge of human papillomavirus and attitudes to vaccination among Swedish high school students. Int J STD & AIDS. 2009, 20: 102-107. 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008200.

Pelucchi C, Esposito S, Galeone C, Semino M, Sabatini C, Picciolli I, Consolo S, Milani G, Principi N: Knowledge of human papillomavirus infection and its prevention among adolescents and parents in the greater Milan area, Northern Italy. BMC Public Health. 2010, 10: 378-10.1186/1471-2458-10-378.

Sachsenweger M, Kundt G, Hauk G, Lafrenz M, Stoll R: Knowledge of school pupils about the HIV/AIDS topic at selected schools in Mecklenburg-Pomerania: Results of a survey of school pupils. Gesundheitswesen. 2010, online publication 2.3.2010, , [ http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1246199 ]

Vinten G: Open versus closed questions - an open issue?. Manag. 1995, 33: 27-31.

Krosnick JA, Presser S: Question and Questionnaire Design. Handbook of Survey research. Edited by: Wright JD, Marsden PV. 2010, Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd, 263-314. Last accessed 02.05.2011, [ http://comm.stanford.edu/faculty/krosnick/Handbook%20of%20Survey%20Research.pdf ]2

Piccinino LJ, Mosher WD: Trends in contraceptive use in the United States: 1982-1995. Family Planning Perspectives. 1998, 30: 4-10. 10.2307/2991517.

Glei DA: Measuring contraceptive use patterns among teenage and adult women. Family Planning Perspectives. 1999, 31: 73-80. 10.2307/2991642.

Everett SA, Warren CW, Santelli JS, Kann L, Collins JL, Kolbe LJ: Use of birth control pills, condoms and withdrawal among U.S. high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000, 27: 112-118. 10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00125-1.

Kaaya SF, Flisher AJ, Mbwambo JK, Schaalma H, Aaro LE, Klepp KI: A review of studies of sexual behaviour of school students in sub-Saharan Africa. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2002, 30: 148-160.

Abraham C, Wight D: Developing HIV-preventive behavioural interventions for young people in Scotland. Int Journal of STD and AIDS. 1996, 7 (suppl 2): 39-42.

Helfferich C, Heidtke B: Country papers on youth sex education in Europe. 2006, BZgA

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/11/727/prepub

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Bremen Institute for Prevention Research and Social Medicine, University of Bremen, Germany

Florence N Samkange-Zeeb, Lena Spallek & Hajo Zeeb

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Florence N Samkange-Zeeb .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

FSZ developed the concept for the study, conducted the literature search, assessed studies for inclusion in the review and extracted data. She also prepared drafts and undertook edits. LS was involved in the development of the study concept, conducted the literature search, assessed studies for inclusion in the review and extracted data. HZ was involved in the development of the study concept. All authors contributed to the editing of the drafts and have read and approved all versions of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12889_2011_3510_moesm1_esm.doc.

Additional file 1: Review Protocol: The preparation process for the systematic review is documented in the file. Included are the objectives of the review, inclusion and exclusion criteria, the search strategy, definition of outcomes, as well as the data abstraction table. (DOC 112 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Samkange-Zeeb, F.N., Spallek, L. & Zeeb, H. Awareness and knowledge of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) among school-going adolescents in Europe: a systematic review of published literature. BMC Public Health 11 , 727 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-727

Download citation

Received : 12 May 2011

Accepted : 25 September 2011

Published : 25 September 2011

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-727

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cervical Cancer

- Participation Rate

- Human Papilloma Virus

- Transmitted Disease

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Loading metrics

Open Access

A Collection on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of sexually transmitted infections: Call for research papers

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

Affiliation World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Affiliation PLOS Medicine, Public Library of Science, Cambridge, United Kingdom

- Nicola Low,

- Nathalie Broutet,

- Richard Turner

Published: June 27, 2017

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002333

- Reader Comments

Citation: Low N, Broutet N, Turner R (2017) A Collection on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of sexually transmitted infections: Call for research papers. PLoS Med 14(6): e1002333. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002333

Copyright: © 2017 Low et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: RT is paid a salary by the Public Library of Science and contributed to this editorial during his salaried time.

Competing interests: We have read the journal's policy and have the following conflicts: NL receives a stipend as a specialty consulting editor for PLOS Medicine and serves on the journal's editorial board. RT’s individual competing interests are at http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/s/staff-editors . PLOS is funded partly through manuscript publication charges, but the PLOS Medicine Editors are paid a fixed salary (their salaries are not linked to the number of papers published in the journal).

Abbreviations: HPV, human papillomavirus; STI, sexually transmitted infection

Provenance: Commissioned; not externally peer-reviewed.

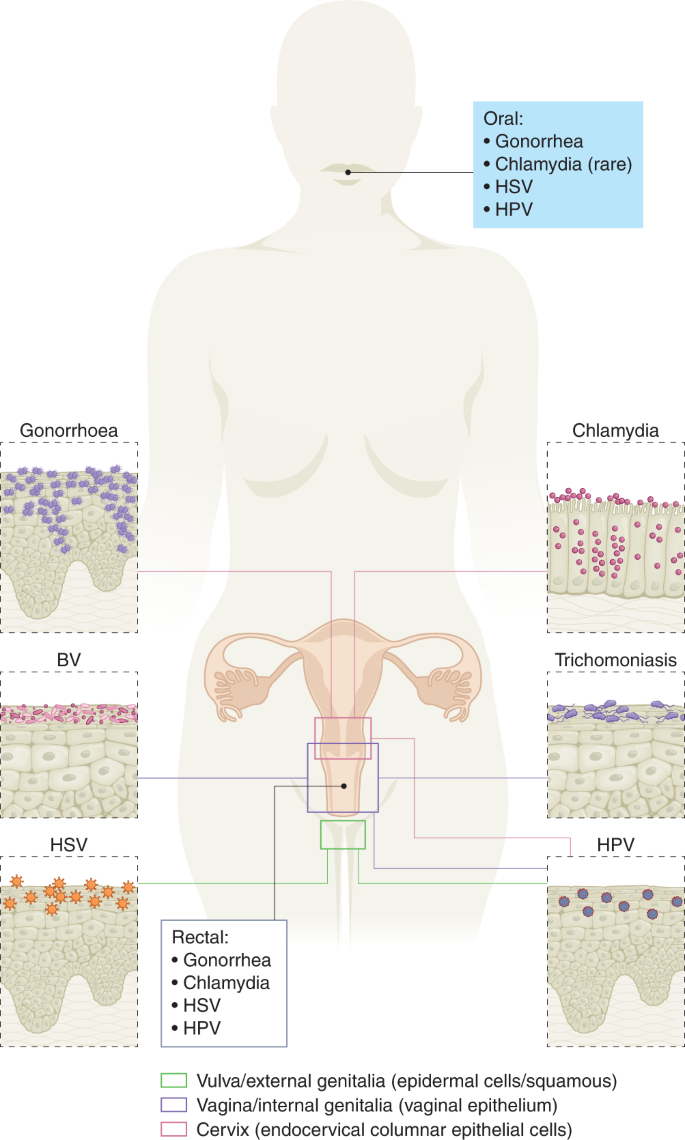

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are common, diverse, and dangerous to health—extending from bacterial diseases that may be readily treatable once diagnosed to viral infections such as HIV that can be life-threatening and, as yet, have no cure. A wide range of sexually transmissible pathogens have adverse effects on sexual and reproductive health, including infertility in women and several different types of cancer, with the global burden of cervical cancer a particular concern. Having an STI can also lead to low self-esteem, stigma, and sexual dysfunction. Moreover, some STIs are transmitted from mother to child and thereby lead to poor pregnancy, neonatal, and child health outcomes, including stillbirth. Emerging pathogens that prove to be sexually transmissible, recently exemplified by Ebola and Zika viruses, can be expected to evoke substantial and widespread concern where the risks and possible consequences of a disease outbreak are sketchily understood.

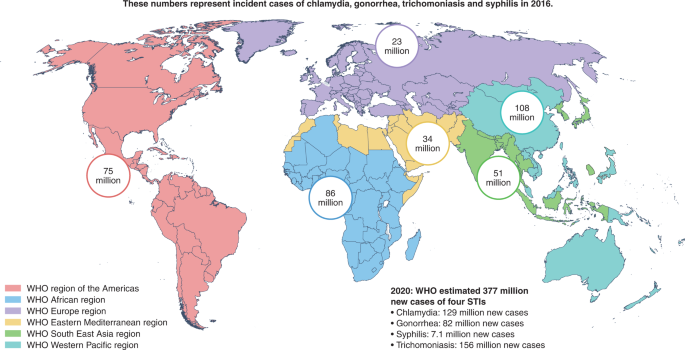

According to WHO [ 1 ], more than 30 different bacteria, viruses, and parasites lead to greater than 1 million sexually transmitted infections each day. Chlamydia (with an estimated 131 million new infections annually), gonorrhea (78 million infections), syphilis (5.6 million infections), and trichomoniasis (143 million infections) are 4 of the most common infections worldwide that can, at present, be treated with existing antibiotic regimens. However, antimicrobial resistance is a growing threat, particularly for gonorrhea and Mycoplasma genitalium . The most prevalent viral STIs are genital herpes simplex virus infection (affecting an estimated 500 million people worldwide) and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection (affecting 290 million women and leading to some 500,000 cases of cervical cancer annually). While antiviral treatment may control recurring herpes in some people, disease prevention and, where possible, vaccine development and deployment are priorities in the absence of curative interventions. Enmeshed as they are in human biology, behavior, and culture, STIs provide great challenges to those responsible for disease surveillance, planning services, and provision of treatment in all countries.

Because of the enormous burden of STIs and their wide-ranging adverse health effects, decisive action will be an essential part of efforts to meet the health component of the Sustainable Development Goals, and the targets of the global health sector strategy on sexually transmitted infections 2016–2021 [ 2 ], which were adopted by the 69th World Health Assembly in May 2016. Accompanying this Editorial are several articles forming part of a WHO-sponsored Collection addressing global policy and practice aimed at achieving control of STIs. Andrew Seale and colleagues discuss the development process for the global strategy to counter STIs [ 3 ]. Global targets for STI control specify, by 2030, achievement of a 90% reduction in syphilis incidence; a 90% reduction in gonorrhea incidence; and occurrence of 50 or fewer cases of congenital syphilis per 100,000 live births in 80% of countries, and Melanie Taylor and colleagues discuss systems for STI surveillance and monitoring of treatment resistance towards these targets [ 4 ]. Taylor and colleagues also discuss programs and criteria aimed at elimination of mother-to-child transmission of syphilis and HIV [ 5 ]. Finally, Paul Bloem and colleagues discuss HPV vaccination for control of cervical cancer and other HPV-related diseases [ 6 ] in different settings, illustrating the prospects of new interventions for STI control. Further discussion articles will appear in future issues of PLOS Medicine , and, as part of the cross-journal Collection, research papers are being published in PLOS Medicine and in other PLOS journals [ 7 ].

To accompany this Collection, we are inviting submission of reports of high-quality research studies with the potential to inform clinical practice or thinking relevant to STIs, focused on the following:

- Epidemiological studies on the incidence, prevalence, and disease burden of STIs, including emerging and re-emerging infections, mother-to-child transmission of STIs, and STIs in the context of new HIV prevention approaches;

- Molecular and genomic studies relevant to clinical advances in STI research, including antimicrobial resistance and microbiome analysis;

- Studies investigating treatment, partner notification, vaccination, behavioral, and combination interventions for STIs, with reports of randomized controlled trials particularly welcome;

- Implementation research, especially focused on interventions for STI prevention and point-of-care approaches to disease diagnosis in low- and middle-income countries, including qualitative research on issues such as stigma;

- Modelling and cost-effectiveness studies relevant to STIs, addressing prevention and treatment interventions.

Please submit your manuscript at http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/s/submit-now . We (NL and NB) will be the guest editors for the Collection, and successful submissions will be published, following peer review, from December 2017 onwards. Papers to be published in December should be submitted by August 11, 2017 but submissions will still be considered, and can be included in the Collection, after that date. Presubmission inquiries are not required, but we ask that you indicate your interest in this call for papers in your cover letter.

Author Contributions

- Conceptualization: NL NB RT.

- Writing – original draft: RT.

- Writing – review & editing: NL NB RT.

- 1. World Health Organization. Sexually transmitted infections factsheet. [Cited 2017 May 18]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs110/en/

- 2. World Health Organization. Global health sector strategy on sexually transmitted infections, 2016–2021. [Cited 2017 May 18]. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/ghss-stis/en/

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

Sexually transmitted infection prevention behaviours: health impact, prevalence, correlates, and interventions

- Psychology and Health 38(1):1-26

- CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

- Utrecht University

- UNSW Sydney

- Maastricht University

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- BMC PUBLIC HEALTH

- Frédérique Tremblay

- Yohann Courtemanche

- Lisa S. Pair

- William E. Somerall

- Namrah Khan

- Fawad Ali Shah

- Paul Norman

- CURR OPIN INFECT DIS

- Zhixian Chen

- Martin Fishbein

- Paige A. Muellerleile

- Jayleen K. L. Gunn

- Darrel H. Higa

- Silke David

- Birgit H B van Benthem

- AM J HEALTH PROMOT

- AIDS Res Ther

- Light Tsegay

- Sarah Wiatrek

- Maria Zlotorzynska

- Travis Sanchez

- Christine M. Khosropour

- Laura Nyblade

- Pia Mingkwan

- Melissa A. Stockton

- Hillard Weinstock

- Ian H. Spicknall

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS

- v.38(1); Jan-Jun 2017

Knowledge and attitude about sexually transmitted infections other than HIV among college students

Nagesh tumkur subbarao.

Department of Dermatology, STD and Leprosy, Sapthagiri Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Center, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Background:

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are the infections which are mainly transmitted through sexual intercourse. Young individuals in the age group of 16 to 24 years are considered to be at more risk for STIs compared to older adults. Young individuals are more likely to practice unprotected sex and have multiple sexual partners. If the STIs are not treated adequately, it can lead to various complications.Most of the people may be aware about HIV/AIDs because of the awareness created by media and the government programs, however knowledge about STIs other than HIV/AIDS is low in the developing countries.

Materials and Methods:

This study was a descriptive cross sectional study to assess the knowledge, awareness and attitude of college students about STIs other than HIV. A total of 350 engineering students from various semesters were included in the study. They were asked to fill up an anonymous questionnaire.

Two hundred and fifty six (73%) males and 94 (27%) females participated in the study. 313 (90%) students had heard about sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and 223 (64%) students had heard about STIs other than HIV. 99% of students knew about HIV where as less than 50% of students knew about other STIs. Teachers, internet and media were the source of information for most of the participants. Almost 75% of the students knew about the modes of transmission of STIs. Less than 50% of the participants knew about the symptoms of STIs and complications. Also attitude of the students towards sexual health and prevention of STIs was variable.

Conclusion:

The findings of our study shows that it is important to orient the students about sexual health and safe sexual practices as it will go a long way in prevention and control of STIs. Also the morbidities and complications associated with STIs can be prevented.

INTRODUCTION

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are the infections which are mainly transmitted through sexual intercourse. The common STIs which we come across in daily practice are gonorrhea, chancroid, syphilis, and chlamydial infections which can be cured and others such as HIV, genital herpes, HPV, and hepatitis B infection which cannot be cured but can be modified with the available treatments.[ 1 ]

Young individuals in the age group of 16–24 years are considered to be at more risk for STIs compared to older adults. The World Health Organization estimates that 20% of persons living with HIV/AIDS are in their 20s and one out of twenty adolescents contract an STI each year.[ 1 ]

Many young individuals stay away from families for a long time when they take up higher education. They either stay in hostels or in paying guest accommodations and come in contact with people from different sociocultural background.

Young individuals are more likely to practice unprotected sex and have multiple sexual partners. In addition, they may not have access to the required information and services to avoid STIs. Furthermore, they may feel hesitant to approach the facilities where information is available.[ 2 ]

If the STIs are not treated adequately, it can lead to various complications such as infertility, urethral stricture, abortions, malignancies, perinatal, and neonatal morbidities.[ 3 , 4 ] Both ulcerative and nonulcerative STIs enhance the transmission of HIV/AIDS.[ 5 ]

Knowledge of STI and their complications and attitude of the young generation toward sexual health are important in planning preventive and treatment strategies.[ 6 ] Most of the people may be aware about HIV/AIDs because of the awareness created by media and government programs; however, knowledge about STIs other than HIV/AIDS is low in the developing countries.[ 7 ]

This study was a descriptive cross-sectional study to assess the knowledge, awareness, and attitude of college students about STIs other than HIV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted among college students in the age group of 18–22 years. A total of 350 engineering students from various semesters were included in the study. A questionnaire was administered to all the students where they had to mention only their age and place. We tried to assess from the questionnaire, knowledge, and attitude of the students regarding the STIs and also their awareness about STIs other than HIV/AIDS. The questions tried to assess their knowledge about symptoms of STI, predisposing/causative factors, preventive measures, complications of STIs, and attitude toward sexual health.

A total of 350 students were administered the questionnaire, 256 (73%) males and 94 (27%) females. One hundred and seventeen students were from Bengaluru and 213 students were from different parts of the country and twenty students were from other countries such as Africa and New Guinea.

One hundred and eighty-six (53%) students were staying with their parents or family and 164 (47%) students were staying with their friends or alone in hostels or paying guest accommodations.

Around 90% (313) of students had heard about STIs and 223 (64%) students had heard about STIs other than HIV. One hundred and eight (30%) students knew that STI can be present in a person even without symptoms, 214 (61%) students did not know if it was possible to have STI without symptoms and 28 (8%) students mentioned that it was not possible to have STI without symptoms.

Tuberculosis, leprosy, and vitiligo were considered as STI by 17 (4.8%), 17 (4.8%), and 20 (5.7%) students, respectively. HIV was known as an STI by 347 (99.2%) students. One hundred and fourteen (32.5%) students knew genital herpes, 95 (27%) syphilis, 108 (30.8%) hepatitis B, 107 (30.5%) genital warts, 92 (26.2%) gonorrhea, 26 (7.4%) lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), and 13 (3.7%) chancroid as STI [ Table 1 ].

Knowledge about various sexually transmitted diseases ( n =350)

Source of information

Teachers were the source of information about STIs in 203 (58%) students followed by internet 181 (51.7%), newspaper/magazines 162 (46.2%), TV/radio 158 (45.1%), friends 142 (40.5%), doctor/clinics 96 (27.4%, parents 28 (8%), and relatives 11 (3.1%) [ Table 2 ].

Source of information about sexually transmitted infections ( n =350)

Predisposing/causative factor

Virus was known to be a causative factor for STI by 169 (48.2%) students followed by bacteria (49, 14%) and fungi (27, 7.7%). Multiple sexual partners and unprotected sex were considered as predisposing factors for STI by 252 (71.7%) and 236 (67.4%), respectively. Other factors considered were sex outside marriage (60, 17.1%), premarital sex (43, 12.2%), alcohol and drug abuse (39, 11.1%), and sex during menstruation (44, 12.5%).

Modes of transmission

The main modes of transmission of STIs known by students include sex with prostitutes/multiple partners (279, 79.7%), infected needles/drugs (256, 73.1%), blood transfusion (252, 72%), not using condoms (242, 69.1%), and mother to child transmission during childbirth (193, 55.1%). Other factors considered by students were poor hygiene 50 (14.2%), kissing 48 (13.7%), using public toilet (31, 8.8%), mosquitoes (35, 10%), shaking hands (13, 13.7%), and sharing towels 14 (4%) [ Table 3 ].

Knowledge about transmission of sexually transmitted infections ( n =350)

Symptoms of sexually transmitted infections

Fever on and off, vaginal/urethral discharge, genital ulcer, abdominal pain, swelling in the groin, and pain while passing urine were the options given to students to assess their knowledge about symptoms of STIs. Vaginal/urethral discharge was considered as a symptom of STI by 136 (38.8%) students followed by genital ulcer 120 (34.2%), fever on and off 118 (33.7%), pain while passing urine 108 (30.8%), swelling in the groin 90 (25.7%), and abdominal pain 104 (29.7%). All the options were considered as symptoms of STI by 41 (11.7%) students. Around 165 students did not know about the symptoms [ Chart 1 ].

Knowledge about symptoms of sexually transmitted infections ( n =350)

Complications of sexually transmitted infections

More than 50% (234) of students did not know about the complications of STI. Cervical cancer was answered by 94 (26.8%) students, infertility by 90 (25.7%), and abortion by 62 (17.7%). Forty (11.4%) students thought all the options to be complication of STIs [ Table 4 ].

Knowledge about complications of sexually transmitted infections ( n =350)

Only 59 (16.8%) students felt masturbation to be harmful to health whereas 138 (39.4%) students disagreed and 151 (43.1%) participants did not know its effect on health [ Table 5 ].

Attitude toward sexually transmitted infections and sexual health ( n =350)

Majority of the students (330, 94.2%) agreed that sex education should be mandatory for young people. However, 13 (3.7%) students were unsure and 7 (2%) students disagreed about the need for sex education.

One hundred and sixty-two (46.2%) participants felt that one should wait until marriage to have sex, whereas 103 (29.4%) students thought it was okay to have premarital sex. Moreover, 85 (24.2%) students did not have any opinion about premarital sex.

One hundred and nine (31.1%) participants did not mind marrying a person who had sex before marriage, whereas 153 (43.7%) students were against such an idea and 88 (25.1%) students could not opine about the issue.

Isolating patients of STI for the safety of others was considered an appropriate measure by 147 (42%) students; however, 120 (34.2%) students did not agree with such measures and 83 (23.7%) students did not know if it was right to do so.

The idea of banning prostitution to control the spread of STIs was agreed upon by 177 (50.5%) students and disagreed by 65 (18.5%) students. One hundred and eight (30.8%) students did not know if this could help control the spread of STI.

Emergency contraceptive pill was considered as a preventive measure for STI by 119 (34%) students, whereas 70 (20%) students disagreed with this measure and 161 (46%) students did not know if emergency contraceptive pills prevented acquiring STI.

Only 107 (30.5%) students agreed that there was no cure for HIV at present whereas 110 (31.4%) students thought HIV/AIDS can be cured and 108 (30.8%) students did not know if HIV can be cured.

The main objective of the study was to assess the knowledge, awareness, and attitude of the engineering college students about STIs, other than HIV and AIDS.

Our study shows that most of the students had heard about STIs, but they knew mostly about HIV/AIDS. STIs other than HIV were known by only around 64% (223) of students. Conditions such as LGV and chancroid were known only to 3%–7% of students. Furthermore, there were students who thought tuberculosis, leprosy, and vitiligo to be sexually transmitted. The findings are similar to a study conducted by Andersson-Ellström and Milsom[ 8 ] and Lal et al .[ 9 ]

Most of the participants in our study had known about these infections through teachers, internet, and newspaper/magazines. Information provided in internet and newspaper/magazines might not be complete and also mislead the student as not all content on internet is scrutinized by qualified health professional. Although many students knew about the STIs, they did not have in-depth knowledge about the diseases and their presentations. A similar finding has been published by Amu and Adegun in their study among secondary school adolescents.[ 10 ]

Most of the respondents had a good knowledge about prevention and transmission of STIs; however, not many were aware of the clinical features and complications of STIs. Only around 40% of students knew about the symptoms of STIs. Our review of literature shows a similar finding in many studies conducted at different geographic locations.[ 5 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]

The attitude of the students about sexual health was variable. Only about 16% students felt masturbation to be harmful to health and another 43% did not know about its effect on health. Whereas 39.4% felt it is not deleterious to health. One-third of students thought it was okay to have premarital sex and 24.2% students did not opine. Almost 46% students answered that they would wait till marriage to have sex. As mentioned in earlier studies, staying away from families and mingling with people from different sociocultural background might change their attitude toward premarital sex and safe sexual practices.[ 9 , 10 ]

When asked about prevention and containment of STI, more than 50% of the participants felt isolation of patient with STI and banning prostitution as an option to prevent spread of STI. Furthermore, almost one-third of the students thought emergency contraceptive pills can prevent STI and one-third did not know if it could prevent STI. Although most of the students knew about the mode of spread of STIs, many of them still had misconceptions about the prevention of spread of STIs. The main problem we felt was almost one-third of students felt emergency contraceptive pills can prevent STI. This point has not been discussed much in earlier studies.[ 8 , 14 ]

Most importantly, only 30% of the students knew that there was no cure for HIV/AIDS, 31.4% thought HIV infection can be cured, and 30% did not know if it can be cured.

Almost 90% of the students agreed about the need for sex education to be included in the curriculum. Probably, they felt they would have had a better knowledge if they had been educated about the issues at a younger age. Similar findings have been reported in other studies.[ 14 ]

On review of literature, not many studies have been done in India, to assess the knowledge and attitude of college students about STIs. Most of the times, sexual health is not discussed by parents/relatives with children as it is still considered a taboo by many people. Even in our study, parents/relatives as a source of information about STIs are very less (11%).[ 9 ] Our study shows that teachers, internet, and media are the main source of information for students.

The studies which have been done earlier are mainly among school students. Although few studies have been done in general population[ 15 , 16 , 17 ] and among university students,[ 4 , 5 ] it is from a different sociocultural background. Hence, our study has aimed at assessing knowledge and attitude of students from professional course (engineering) about STI and AIDS. The findings of our study show that it is important to orient the students about sexual health and safe sexual practices as it will go a long way in prevention and control of STIs. Furthermore, the morbidities and complications associated with STIs can be prevented.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the help and support provided by Dr. Jayanthi V, Dr. Savitha AS, Dr. Priyadarshini M, and Dr. Reshma Abraham in the conduct of the study and preparation of the manuscript.

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Journal Proposal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- PubMed/Medline

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Awareness, knowledge and risky behaviors of sexually transmitted diseases among young people in greece.

1. Introduction

2. materials and methods, 2.1. study design and participants, ethics approval, 2.2. data collection and processing, 2.3. evaluation of knowledge score, 2.4. data management, 2.5. statistical analysis, 3.1. socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, 3.2. sexual-risk associated knowledge, 3.3. evaluation of sexual behavior-associated risk, 3.4. assessment of std knowledge score, 3.5. unifactorial associations of knowledge score with socio-demographic characteristics, 3.6. multifactorial associations of knowledge score with socio-demographic characteristics, 4. discussion, 5. conclusions, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

- Newman, L.; Rowley, J.; Hoorn, S.v.; Wijesooriya, N.S.; Unemo, M.; Low, N.; Stevens, G.; Gottlieb, S.; Kiarie, J.; Temmerman, M. Global Estimates of the Prevalence and Incidence of Four Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections in 2012 Based on Systematic Review and Global Reporting. PLoS ONE 2015 , 10 , e0143304. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Rowley, J.; Hoorn, S.V.; Korenromp, E.; Low, N.; Unemo, M.; AbuRaddad, L.J.; Chico, R.M.; Smolak, A.; Newman, L.; Gottlieb, S.; et al. Chlamydia, Gonorrhoea, Trichomoniasis and Syphilis: Global Prevalence and Incidence Estimates. 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/97/8/18-228486.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis) (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Korenromp, E.L.; Rowley, J.; Alonso, M.; Mello, M.B.; Wijesooriya, N.S.; Mahiané, S.G.; Ishikawa, N.; Le, L.-V.; Newman-Owiredu, M.; Nagelkerke, N.; et al. Global burden of maternal and congenital syphilis and associated adverse birth outcomes—Estimates for 2016 and progress since 2012. PLoS ONE 2019 , 14 , e0211720. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- WHO|Global Health Sector Strategy on Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2016–2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/ghss-stis/en/ (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Juliana, N.C.A.; Omar, A.M.; Pleijster, J.; Aftab, F.; Uijldert, N.B.; Ali, S.M.; Ouburg, S.; Sazawal, S.; Morré, S.A.; Deb, S.; et al. The Natural Course of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Trichomonas vaginalis, and Mycoplasma genitalium in Pregnant and Post-Delivery Women in Pemba Island, Tanzania. Microorganisms 2021 , 9 , 1180. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- World Health Organization. Department of Child and Adolescent Health and Development. World Health Organization, Child and Adolescent Health and Development Progress Report 2009 ; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bekker, L.-G.; Johnson, L.; Wallace, M.; Hosek, S. Building our youth for the future. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2015 , 18 , 20027. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Vanable, P.A.; Carey, M.P.; Brown, J.L.; DiClemente, R.J.; Salazar, L.F.; Brown, L.K.; Romer, D.; Valois, R.F.; Hennessy, M.; Stanton, B.F. Test–Retest Reliability of Self-Reported HIV/STD-Related Measures Among African-American Adolescents in Four U.S. Cities. J. Adolesc. Health 2009 , 44 , 214–221. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Siracusano, S.; Silvestri, T.; Casotto, D. Sexually Transmitted Diseases: Epidemiological and Clinical Aspects in Adults. Urol. J. 2014 , 81 , 200–208. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Sieving, R.E.; O’Brien, J.R.G.; Saftner, M.A.; Argo, T.A. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Among US Adolescents and Young Adults: Patterns, Clinical Considerations, and Prevention. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2019 , 54 , 207–225. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Downing-Matibag, T.M.; Geisinger, B. Hooking Up and Sexual Risk Taking Among College Students: A Health Belief Model Perspective. APA PsycNet 2009 , 19 , 1196–1209. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Visalli, G.; Cosenza, B.; Mazzu, F.; Bertuccio, M.; Spataro, P.; Pellicanò, G.F.; di Pietro, A.; Picerno, I.; Facciolà, A. Knowledge of sexually transmitted infections and risky behaviours: A survey among high school and university students. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2019 , 60 , E84. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Xenaki, D.; Plotas, P.; Michail, G.; Poulas, K.; Jelastopulu, E. Knowledge, behaviours and attitudes for human papillomavirus (HPV) prevention among educators and health professionals in Greece. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020 , 24 , 7745–7752. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Nikolopoulos, G.K.; Chanos, S.; Tsioptsias, E.; Hodges-Mameletzis, I.; Paraskeva, D.; Dedes, N. HIV incidence among men who have sex with men at a community-based facility in Greece. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2019 , 27 , 54–57. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Pavlopoulou, I.D.; Dikalioti, S.K.; Gountas, I.; Sypsa, V.; Malliori, M.; Pantavou, K.; Jarlais, D.D.; Nikolopoulos, G.K.; Hatzakis, A. High-risk behaviors and their association with awareness of HIV status among participants of a large-scale prevention intervention in Athens, Greece. BMC Public Health 2020 , 20 , 105. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Loumpardia, P.; Bourmpos, K.; Loumpardias, G.A.; Kalampoki, V.; Valasoulis, G.; Valari, O.; Vythoulkasl, D.; Deligeoroglou, E.; Koliopoulos, G. Epidemiological, Clinical, and Virological Characteristics of Women with Genital Warts in Greece—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26054116/ (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Folasayo, A.T.; Oluwasegun, A.J.; Samsudin, S.; Saudi, S.N.S.; Osman, M.; Hamat, R.A. Assessing the Knowledge Level, Attitudes, Risky Behaviors and Preventive Practices on Sexually Transmitted Diseases among University Students as Future Healthcare Providers in the Central Zone of Malaysia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017 , 14 , 159. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Gökengin, D.; Yamazhan, T.; Özkaya, D.; Aytuǧ, S.; Ertem, E.; Arda, B.; Serter, D. Sexual Knowledge, Attitudes, and Risk Behaviors of Students in Turkey. J. Sch. Health 2003 , 73 , 258–263. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Ekşi, Z.; Kömürcü, N. Knowledge Level of University Students about Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014 , 122 , 465–472. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]