- Business Intelligence Reporting

- Data Driven

- Data Analysis Method

- Business Model

- Business Analysis

- Quantitative Research

- Business Analytics

- Marketing Analytics

- Data Integration

- Digital Transformation Strategy

- Online Training

- Local Training Events

5 Strengths and 5 Limitations of Qualitative Research

Lauren Christiansen

Insight into qualitative research.

Anyone who reviews a bunch of numbers knows how impersonal that feels. What do numbers really reveal about a person's beliefs, motives, and thoughts? While it's critical to collect statistical information to identify business trends and inefficiencies, stats don't always tell the full story. Why does the customer like this product more than the other one? What motivates them to post this particular hashtag on social media? How do employees actually feel about the new supply chain process? To answer more personal questions that delve into the human experience, businesses often employ a qualitative research process.

10 Key Strengths and Limitations of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research helps entrepreneurs and established companies understand the many factors that drive consumer behavior. Because most organizations collect and analyze quantitative data, they don't always know exactly how a target market feels and what it wants. It helps researchers when they can observe a small sample size of consumers in a comfortable environment, ask questions, and let them speak. Research methodology varies depending on the industry and type of business needs. Many companies employ mixed methods to extract the insights they require to improve decision-making. While both quantitative research and qualitative methods are effective, there are limitations to both. Quantitative research is expensive, time-consuming, and presents a limited understanding of consumer needs. However, qualitative research methods generate less verifiable information as all qualitative data is based on experience. Businesses should use a combination of both methods to overcome any associated limitations.

Strengths of Qualitative Research

- Captures New Beliefs - Qualitative research methods extrapolate any evolving beliefs within a market. This may include who buys a product/service, or how employees feel about their employers.

- Fewer Limitations - Qualitative studies are less stringent than quantitative ones. Outside the box answers to questions, opinions, and beliefs are included in data collection and data analysis.

- More Versatile - Qualitative research is much easier at times for researchers. They can adjust questions, adapt to circumstances that change or change the environment to optimize results.

- Greater Speculation - Researchers can speculate more on what answers to drill down into and how to approach them. They can use instinct and subjective experience to identify and extract good data.

- More Targeted - This research process can target any area of the business or concern it may have. Researchers can concentrate on specific target markets to collect valuable information. This takes less time and requires fewer resources than quantitative studies.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

- Sample Sizes - Businesses need to find a big enough group of participants to ensure results are accurate. A sample size of 15 people is not enough to show a reliable picture of how consumers view a product. If it is not possible to find a large enough sample size, the data collected may be insufficient.

- Bias - For internal qualitative studies, employees may be biased. For example, workers may give a popular answer that colleagues agree with rather than a true opinion. This can negatively influence the outcome of the study.

- Self-Selection Bias - Businesses that call on volunteers to answer questions worry that the people who respond are not reflective of the greater group. It is better if the company selects individuals at random for research studies, particularly if they are employees. However, this changes the process from qualitative to quantitative methods.

- Artificial - It isn't typical to observe consumers in stores, gather a focus group together, or ask employees about their experiences at work. This artificiality may impact the findings, as it is outside the norm of regular behavior and interactions.

- Quality - Questions It's hard to know whether researcher questions are quality or not because they are all subjective. Researchers need to ask how and why individuals feel the way they do to receive the most accurate answers.

Key Takeaways on Strengths and Limitations of Qualitative Research

- Qualitative research helps entrepreneurs and small businesses understand what drives human behavior. It is also used to see how employees feel about workflows and tasks.

- Companies can extract insights from qualitative research to optimize decision-making and improve products or services.

- Qualitative research captures new beliefs, has fewer limitations, is more versatile, and is more targeted. It also allows researchers to speculate and insert themselves more into the research study.

- Qualitative research has many limitations which include possible small sample sizes, potential bias in answers, self-selection bias, and potentially poor questions from researchers. It also can be artificial because it isn't typical to observe participants in focus groups, ask them questions at work, or invite them to partake in this type of research method.

Must-Read Content

The Top Qualitative Research Methods for Business Success

5 Qualitative Research Examples in Action

7 Types of Qualitative Research to Look Out For

What is Qualitative Research, Really?

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organizations to understand their cultures. | |

| Action research | Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

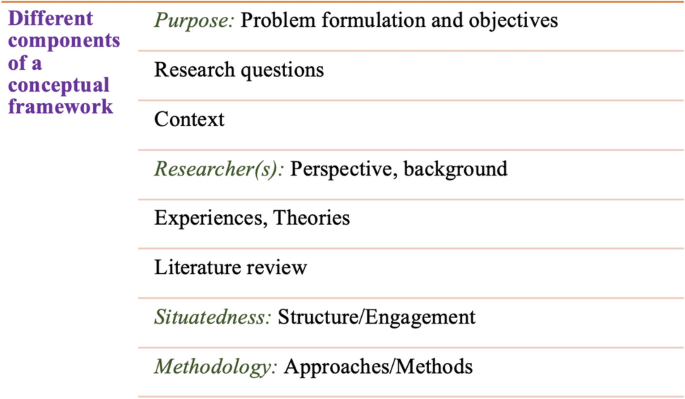

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorize common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 7, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 18, Issue 2

- Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Helen Noble 1 ,

- Joanna Smith 2

- 1 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Queens's University Belfast , Belfast , UK

- 2 School of Human and Health Sciences, University of Huddersfield , Huddersfield , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Helen Noble School of Nursing and Midwifery, Queens's University Belfast, Medical Biology Centre, 97 Lisburn Rd, Belfast BT9 7BL, UK; helen.noble{at}qub.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2015-102054

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Evaluating the quality of research is essential if findings are to be utilised in practice and incorporated into care delivery. In a previous article we explored ‘bias’ across research designs and outlined strategies to minimise bias. 1 The aim of this article is to further outline rigour, or the integrity in which a study is conducted, and ensure the credibility of findings in relation to qualitative research. Concepts such as reliability, validity and generalisability typically associated with quantitative research and alternative terminology will be compared in relation to their application to qualitative research. In addition, some of the strategies adopted by qualitative researchers to enhance the credibility of their research are outlined.

Are the terms reliability and validity relevant to ensuring credibility in qualitative research?

Although the tests and measures used to establish the validity and reliability of quantitative research cannot be applied to qualitative research, there are ongoing debates about whether terms such as validity, reliability and generalisability are appropriate to evaluate qualitative research. 2–4 In the broadest context these terms are applicable, with validity referring to the integrity and application of the methods undertaken and the precision in which the findings accurately reflect the data, while reliability describes consistency within the employed analytical procedures. 4 However, if qualitative methods are inherently different from quantitative methods in terms of philosophical positions and purpose, then alterative frameworks for establishing rigour are appropriate. 3 Lincoln and Guba 5 offer alternative criteria for demonstrating rigour within qualitative research namely truth value, consistency and neutrality and applicability. Table 1 outlines the differences in terminology and criteria used to evaluate qualitative research.

- View inline

Terminology and criteria used to evaluate the credibility of research findings

What strategies can qualitative researchers adopt to ensure the credibility of the study findings?

Unlike quantitative researchers, who apply statistical methods for establishing validity and reliability of research findings, qualitative researchers aim to design and incorporate methodological strategies to ensure the ‘trustworthiness’ of the findings. Such strategies include:

Accounting for personal biases which may have influenced findings; 6

Acknowledging biases in sampling and ongoing critical reflection of methods to ensure sufficient depth and relevance of data collection and analysis; 3

Meticulous record keeping, demonstrating a clear decision trail and ensuring interpretations of data are consistent and transparent; 3 , 4

Establishing a comparison case/seeking out similarities and differences across accounts to ensure different perspectives are represented; 6 , 7

Including rich and thick verbatim descriptions of participants’ accounts to support findings; 7

Demonstrating clarity in terms of thought processes during data analysis and subsequent interpretations 3 ;

Engaging with other researchers to reduce research bias; 3

Respondent validation: includes inviting participants to comment on the interview transcript and whether the final themes and concepts created adequately reflect the phenomena being investigated; 4

Data triangulation, 3 , 4 whereby different methods and perspectives help produce a more comprehensive set of findings. 8 , 9

Table 2 provides some specific examples of how some of these strategies were utilised to ensure rigour in a study that explored the impact of being a family carer to patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease managed without dialysis. 10

Strategies for enhancing the credibility of qualitative research

In summary, it is imperative that all qualitative researchers incorporate strategies to enhance the credibility of a study during research design and implementation. Although there is no universally accepted terminology and criteria used to evaluate qualitative research, we have briefly outlined some of the strategies that can enhance the credibility of study findings.

- Sandelowski M

- Lincoln YS ,

- Barrett M ,

- Mayan M , et al

- Greenhalgh T

- Lingard L ,

Twitter Follow Joanna Smith at @josmith175 and Helen Noble at @helnoble

Competing interests None.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Jump to navigation

Cochrane Training

Chapter 21: qualitative evidence.

Jane Noyes, Andrew Booth, Margaret Cargo, Kate Flemming, Angela Harden, Janet Harris, Ruth Garside, Karin Hannes, Tomás Pantoja, James Thomas

Key Points:

- A qualitative evidence synthesis (commonly referred to as QES) can add value by providing decision makers with additional evidence to improve understanding of intervention complexity, contextual variations, implementation, and stakeholder preferences and experiences.

- A qualitative evidence synthesis can be undertaken and integrated with a corresponding intervention review; or

- Undertaken using a mixed-method design that integrates a qualitative evidence synthesis with an intervention review in a single protocol.

- Methods for qualitative evidence synthesis are complex and continue to develop. Authors should always consult current methods guidance at methods.cochrane.org/qi .

This chapter should be cited as: Noyes J, Booth A, Cargo M, Flemming K, Harden A, Harris J, Garside R, Hannes K, Pantoja T, Thomas J. Chapter 21: Qualitative evidence. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane, 2023. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

21.1 Introduction

The potential contribution of qualitative evidence to decision making is well-established (Glenton et al 2016, Booth 2017, Carroll 2017). A synthesis of qualitative evidence can inform understanding of how interventions work by:

- increasing understanding of a phenomenon of interest (e.g. women’s conceptualization of what good antenatal care looks like);

- identifying associations between the broader environment within which people live and the interventions that are implemented;

- increasing understanding of the values and attitudes toward, and experiences of, health conditions and interventions by those who implement or receive them; and

- providing a detailed understanding of the complexity of interventions and implementation, and their impacts and effects on different subgroups of people and the influence of individual and contextual characteristics within different contexts.

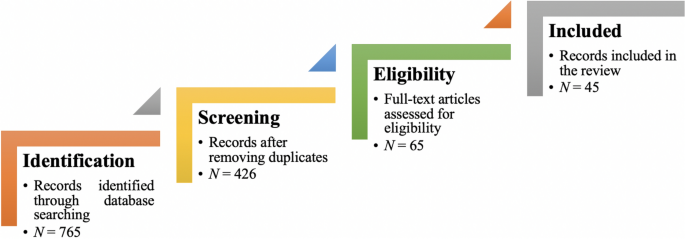

The aim of this chapter is to provide authors (who already have experience of undertaking qualitative research and qualitative evidence synthesis) with additional guidance on undertaking a qualitative evidence synthesis that is subsequently integrated with an intervention review. This chapter draws upon guidance presented in a series of six papers published in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology (Cargo et al 2018, Flemming et al 2018, Harden et al 2018, Harris et al 2018, Noyes et al 2018a, Noyes et al 2018b) and from a further World Health Organization series of papers published in BMJ Global Health, which extend guidance to qualitative evidence syntheses conducted within a complex intervention and health systems and decision making context (Booth et al 2019a, Booth et al 2019b, Flemming et al 2019, Noyes et al 2019, Petticrew et al 2019).The qualitative evidence synthesis and integration methods described in this chapter supplement Chapter 17 on methods for addressing intervention complexity. Authors undertaking qualitative evidence syntheses should consult these papers and chapters for more detailed guidance.

21.2 Designs for synthesizing and integrating qualitative evidence with intervention reviews

There are two main designs for synthesizing qualitative evidence with evidence of the effects of interventions:

- Sequential reviews: where one or more existing intervention review(s) has been published on a similar topic, it is possible to do a sequential qualitative evidence synthesis and then integrate its findings with those of the intervention review to create a mixed-method review. For example, Lewin and colleagues (Lewin et al (2010) and Glenton and colleagues (Glenton et al (2013) undertook sequential reviews of lay health worker programmes using separate protocols and then integrated the findings.

- Convergent mixed-methods review: where no pre-existing intervention review exists, it is possible to do a full convergent ‘mixed-methods’ review where the trials and qualitative evidence are synthesized separately, creating opportunities for them to ‘speak’ to each other during development, and then integrated within a third synthesis. For example, Hurley and colleagues (Hurley et al (2018) undertook an intervention review and a qualitative evidence synthesis following a single protocol.

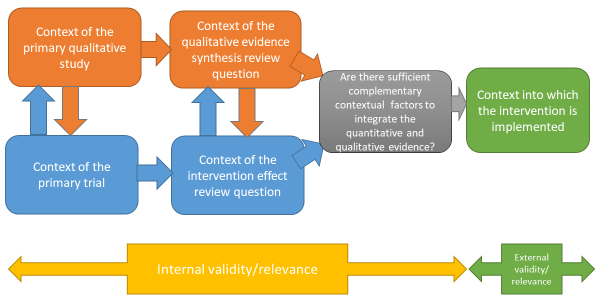

It is increasingly common for sequential and convergent reviews to be conducted by some or all of the same authors; if not, it is critical that authors working on the qualitative evidence synthesis and intervention review work closely together to identify and create sufficient points of integration to enable a third synthesis that integrates the two reviews, or the conduct of a mixed-method review (Noyes et al 2018a) (see Figure 21.2.a ). This consideration also applies where an intervention review has already been published and there is no prior relationship with the qualitative evidence synthesis authors. We recommend that at least one joint author works across both reviews to facilitate development of the qualitative evidence synthesis protocol, conduct of the synthesis, and subsequent integration of the qualitative evidence synthesis with the intervention review within a mixed-methods review.

Figure 21.2.a Considering context and points of contextual integration with the intervention review or within a mixed-method review

21.3 Defining qualitative evidence and studies

We use the term ‘qualitative evidence synthesis’ to acknowledge that other types of qualitative evidence (or data) can potentially enrich a synthesis, such as narrative data derived from qualitative components of mixed-method studies or free text from questionnaire surveys. We would not, however, consider a questionnaire survey to be a qualitative study and qualitative data from questionnaires should not usually be privileged over relevant evidence from qualitative studies. When thinking about qualitative evidence, specific terminology is used to describe the level of conceptual and contextual detail. Qualitative evidence that includes higher or lower levels of conceptual detail is described as ‘rich’ or ‘poor’. Associated terms ‘thick’ or ‘thin’ are best used to refer to higher or lower levels of contextual detail. Review authors can potentially develop a stronger synthesis using rich and thick qualitative evidence but, in reality, they will identify diverse conceptually rich and poor and contextually thick and thin studies. Developing a clear picture of the type and conceptual richness of available qualitative evidence strongly influences the choice of methodology and subsequent methods. We recommend that authors undertake scoping searches to determining the type and richness of available qualitative evidence before selecting their methodology and methods.

A qualitative study is a research study that uses a qualitative method of data collection and analysis. Review authors should include the studies that enable them to answer their review question. When selecting qualitative studies in a review about intervention effects, two types of qualitative study are available: those that collect data from the same participants as the included trials, known as ‘trial siblings’; and those that address relevant issues about the intervention, but as separate items of research – not connected to any included trials. Both can provide useful information, with trial sibling studies obviously closer in terms of their precise contexts to the included trials (Moore et al 2015), and non-sibling studies possibly contributing perspectives not present in the trials (Noyes et al 2016b).

21.4 Planning a qualitative evidence synthesis linked to an intervention review

The Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group (QIMG) website provides links to practical guidance and key steps for authors who are considering a qualitative evidence synthesis ( methods.cochrane.org/qi ). The RETREAT framework outlines seven key considerations that review authors should systematically work through when planning a review (Booth et al 2016, Booth et al 2018) ( Box 21.4.a ). Flemming and colleagues (Flemming et al (2019) further explain how to factor in such considerations when undertaking a qualitative evidence synthesis within a complex intervention and decision making context when complexity is an important consideration.

Box 21.4.a RETREAT considerations when selecting an appropriate method for qualitative synthesis

| first, consider the complexity of the review question. Which elements contribute most to complexity (e.g. the condition, the intervention or the context)? Which elements should be prioritized as the focal point for attention? (Squires et al 2013, Kelly et al 2017). consider the philosophical foundations of the primary studies. Would it be appropriate to favour a method such as thematic synthesis that it is less reliant on epistemological considerations? (Barnett-Page and Thomas 2009). – consider what type of qualitative evidence synthesis will be feasible and manageable within the time frame available (Booth et al 2016). – consider whether the ambition of the review matches the available resources. Will the extent of the scope and the sampling approach of the review need to be limited? (Benoot et al 2016, Booth et al 2016). consider access to expertise, both within the review team and among a wider group of advisors. Does the available expertise match the qualitative evidence synthesis approach chosen? (Booth et al 2016). consider the intended audience and purpose of the review. Does the approach to question formulation, the scope of the review and the intended outputs meet their needs? (Booth et al 2016). consider the type of data present in typical studies for inclusion. To what extent are candidate studies conceptually rich and contextually thick in their detail? |

21.5 Question development

The review question is critical to development of the qualitative evidence synthesis (Harris et al 2018). Question development affords a key point for integration with the intervention review. Complementary guidance supports novel thinking about question development, application of question development frameworks and the types of questions to be addressed by a synthesis of qualitative evidence (Cargo et al 2018, Harris et al 2018, Noyes et al 2018a, Booth et al 2019b, Flemming et al 2019).

Research questions for quantitative reviews are often mapped using structures such as PICO. Some qualitative reviews adopt this structure, or use an adapted variation of such a structure (e.g. SPICE (Setting, Perspective, Intervention or Phenomenon of Interest, Comparison, Evaluation) or SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type); (Cooke et al 2012). Booth and colleagues (Booth et al (2019b) propose an extended question framework (PerSPecTIF) to describe both wider context and immediate setting that is particularly suited to qualitative evidence synthesis and complex intervention reviews (see Table 21.5.a ).

Detailed attention to the question and specification of context at an early stage is critical to many aspects of qualitative synthesis (see Petticrew et al (2019) and Booth et al (2019a) for a more detailed discussion). By specifying the context a review team is able to identify opportunities for integration with the intervention review, or opportunities for maximizing use and interpretation of evidence as a mixed-method review progresses (see Figure 21.2.a ), and informs both the interpretation of the observed effects and assessment of the strength of the evidence available in addressing the review question (Noyes et al 2019). Subsequent application of GRADE CERQual (Lewin et al 2015, Lewin et al 2018), an approach to assess the confidence in synthesized qualitative findings, requires further specification of context in the review question.

Table 21.5.a PerSPecTIF Question formulation framework for qualitative evidence syntheses (Booth et al (2019b). Reproduced with permission of BMJ Publishing Group

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perspective | Setting | Phenomenon of interest/ Problem | Environment | Comparison (optional) | Time/ Timing | Findings |

| From the perspective of a pregnant woman | In the setting of rural communities | How does facility-based care | Within an environment of poor transport infrastructure and distantly located facilities | Compare with traditional birth attendants at home | Up to and including delivery | In relation to the woman’s perceptions and experiences? |

21.6 Questions exploring intervention implementation

Additional guidance is available on formulation of questions to understand and assess intervention implementation (Cargo et al 2018). A strong understanding of how an intervention is thought to work, and how it should be implemented in practice, will enable a critical consideration of whether any observed lack of effect might be due to a poorly conceptualized intervention (i.e. theory failure) or a poor intervention implementation (i.e. implementation failure). Heterogeneity needs to be considered for both the underlying theory and the ways in which the intervention was implemented. An a priori scoping review (Levac et al 2010), concept analysis (Walker and Avant 2005), critical review (Grant and Booth 2009) or textual narrative synthesis (Barnett-Page and Thomas 2009) can be undertaken to classify interventions and/or to identify the programme theory, logic model or implementation measures and processes. The intervention Complexity Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews iCAT_SR (Lewin et al 2017) may be helpful in classifying complexity in interventions and developing associated questions.

An existing intervention model or framework may be used within a new topic or context. The ‘best-fit framework’ approach to synthesis (Carroll et al 2013) can be used to establish the degree to which the source context (from where the framework was derived) resembles the new target context (see Figure 21.2.a ). In the absence of an explicit programme theory and detail of how implementation relates to outcomes, an a priori realist review, meta-ethnography or meta-interpretive review can be undertaken (Booth et al 2016). For example, Downe and colleagues (Downe et al (2016) undertook an initial meta-ethnography review to develop an understanding of the outcomes of importance to women receiving antenatal care.

However, these additional activities are very resource-intensive and are only recommended when the review team has sufficient resources to supplement the planned qualitative evidence syntheses with an additional explanatory review. Where resources are less plentiful a review team could engage with key stakeholders to articulate and develop programme theory (Kelly et al 2017, De Buck et al 2018).

21.6.1 Using logic models and theories to support question development

Review authors can develop a more comprehensive representation of question features through use of logic models, programme theories, theories of change, templates and pathways (Anderson et al 2011, Kneale et al 2015, Noyes et al 2016a) (see also Chapter 17, Section 17.2.1 and Chapter 2, Section 2.5.1 ). These different forms of social theory can be used to visualize and map the research question, its context, components, influential factors and possible outcomes (Noyes et al 2016a, Rehfuess et al 2018).

21.6.2 Stakeholder engagement

Finally, review authors need to engage stakeholders, including consumers affected by the health issue and interventions, or likely users of the review from clinical or policy contexts. From the preparatory stage, this consultation can ensure that the review scope and question is appropriate and resulting products address implementation concerns of decision makers (Kelly et al 2017, Harris et al 2018).

21.7 Searching for qualitative evidence

In comparison with identification of quantitative studies (see also Chapter 4 ), procedures for retrieval of qualitative research remain relatively under-developed. Particular challenges in retrieval are associated with non-informative titles and abstracts, diffuse terminology, poor indexing and the overwhelming prevalence of quantitative studies within data sources (Booth et al 2016).

Principal considerations when planning a search for qualitative studies, and the evidence that underpins them, have been characterized using a 7S framework from Sampling and Sources through Structured questions, Search procedures, Strategies and filters and Supplementary strategies to Standards for Reporting (Booth et al 2016).

A key decision, aligned to the purpose of the qualitative evidence synthesis is whether to use the comprehensive, exhaustive approaches that characterize quantitative searches or whether to use purposive sampling that is more sensitive to the qualitative paradigm (Suri 2011). The latter, which is used when the intent is to generate an interpretative understanding, for example, when generating theory, draws upon a versatile toolkit that includes theoretical sampling, maximum variation sampling and intensity sampling. Sources of qualitative evidence are more likely to include book chapters, theses and grey literature reports than standard quantitative study reports, and so a search strategy should place extra emphasis on these sources. Local databases may be particularly valuable given the criticality of context (Stansfield et al 2012).

Another key decision is whether to use study filters or simply to conduct a topic-based search where qualitative studies are identified at the study selection stage. Search filters for qualitative studies lack the specificity of their quantitative counterparts. Nevertheless, filters may facilitate efficient retrieval by study type (e.g. qualitative (Rogers et al 2018) or mixed methods (El Sherif et al 2016) or by perspective (e.g. patient preferences (Selva et al 2017)) particularly where the quantitative literature is overwhelmingly large and thus increases the number needed to retrieve. Poor indexing of qualitative studies makes citation searching (forward and backward) and the Related Articles features of electronic databases particularly useful (Cooper et al 2017). Further guidance on searching for qualitative evidence is available (Booth et al 2016, Noyes et al 2018a). The CLUSTER method has been proposed as a specific named method for tracking down associated or sibling reports (Booth et al 2013). The BeHEMoTh approach has been developed for identifying explicit use of theory (Booth and Carroll 2015).

21.7.1 Searching for process evaluations and implementation evidence

Four potential approaches are available to identify process evaluations.

- Identify studies at the point of study selection rather than through tailored search strategies. This involves conducting a sensitive topic search without any study design filter (Harden et al 1999), and identifying all study designs of interest during the screening process. This approach can be feasible when a review question involves multiple publication types (e.g. randomized trial, qualitative research and economic evaluations), which then do not require separate searches.

- Restrict included process evaluations to those conducted within randomized trials, which can be identified using standard search filters (see Chapter 4, Section 4.4.7 ). This method relies on reports of process evaluations also describing the surrounding randomized trial in enough detail to be identified by the search filter.

- Use unevaluated filter terms (such as ‘process evaluation’, ‘program(me) evaluation’, ‘feasibility study’, ‘implementation’ or ‘proof of concept’ etc) to retrieve process evaluations or implementation data. Approaches using strings of terms associated with the study type or purpose are considered experimental. There is a need to develop and test such filters. It is likely that such filters may be derived from the study type (process evaluation), the data type (process data) or the application (implementation) (Robbins et al 2011).

- Minimize reliance on topic-based searching and rely on citations-based approaches to identify linked reports, published or unpublished, of a particular study (Booth et al 2013) which may provide implementation or process data (Bonell et al 2013).

More detailed guidance is provided by Cargo and colleagues (Cargo et al (2018).

21.8 Assessing methodological strengths and limitations of qualitative studies

Assessment of the methodological strengths and limitations of qualitative research remains contested within the primary qualitative research community (Garside 2014). However, within systematic reviews and evidence syntheses it is considered essential, even when studies are not to be excluded on the basis of quality (Carroll et al 2013). One review found almost 100 appraisal tools for assessing primary qualitative studies (Munthe-Kaas et al 2019). Limitations included a focus on reporting rather than conduct and the presence of items that are separate from, or tangential to, consideration of study quality (e.g. ethical approval).

Authors should distinguish between assessment of study quality and assessment of risk of bias by focusing on assessment of methodological strengths and limitations as a marker of study rigour (what we term a ‘risk to rigour’ approach (Noyes et al 2019)). In the absence of a definitive risk to rigour tool, we recommend that review authors select from published, commonly used and validated tools that focus on the assessment of the methodological strengths and limitations of qualitative studies (see Box 21.8.a ). Pragmatically, we consider a ‘validated’ tool as one that has been subjected to evaluation. Issues such as inter-rater reliability are afforded less importance given that identification of complementary or conflicting perspectives on risk to rigour is considered more useful than achievement of consensus per se (Noyes et al 2019).

The CASP tool for qualitative research (as one example) maps onto the domains in Box 21.8.a (CASP 2013). Tools not meeting the criterion of focusing on assessment of methodological strengths and limitations include those that integrate assessment of the quality of reporting (such as scoring of the title and abstract, etc) into an overall assessment of methodological strengths and limitations. As with other risk of bias assessment tools, we strongly recommend against the application of scores to domains or calculation of total quality scores. We encourage review authors to discuss the studies and their assessments of ‘risk to rigour’ for each paper and how the study’s methodological limitations may affect review findings (Noyes et al 2019). We further advise that qualitative ‘sensitivity analysis’, exploring the robustness of the synthesis and its vulnerability to methodologically limited studies, be routinely applied regardless of the review authors’ overall confidence in synthesized findings (Carroll et al 2013). Evidence suggests that qualitative sensitivity analysis is equally advisable for mixed methods studies from which the qualitative component is extracted (Verhage and Boels 2017).

Box 21.8.a Example domains that provide an assessment of methodological strengths and limitations to determine study rigour

| Clear aims and research question Congruence between the research aims/question and research design/method(s) Rigour of case and or participant identification, sampling and data collection to address the question Appropriate application of the method Richness/conceptual depth of findings Exploration of deviant cases and alternative explanations Reflexivity of the researchers* *Reflexivity encourages qualitative researchers and reviewers to consider the actual and potential impacts of the researcher on the context, research participants and the interpretation and reporting of data and findings (Newton et al 2012). Being reflexive entails making conflicts of interest transparent, discussing the impact of the reviewers and their decisions on the review process and findings and making transparent any issues discussed and subsequent decisions. |

Adapted from Noyes et al (2019) and Alvesson and Sköldberg (2009)

21.8.1 Additional assessment of methodological strengths and limitations of process evaluation and intervention implementation evidence

Few assessment tools explicitly address rigour in process evaluation or implementation evidence. For qualitative primary studies, the 8-item process evaluation tool developed by the EPPI-Centre (Rees et al 2009, Shepherd et al 2010) can be used to supplement tools selected to assess methodological strengths and limitations and risks to rigour in primary qualitative studies. One of these items, a question on usefulness (framed as ‘how well the intervention processes were described and whether or not the process data could illuminate why or how the interventions worked or did not work’ ) offers a mechanism for exploring process mechanisms (Cargo et al 2018).

21.9 Selecting studies to synthesize

Decisions about inclusion or exclusion of studies can be more complex in qualitative evidence syntheses compared to reviews of trials that aim to include all relevant studies. Decisions on whether to include all studies or to select a sample of studies depend on a range of general and review specific criteria that Noyes and colleagues (Noyes et al (2019) outline in detail. The number of qualitative studies selected needs to be consistent with a manageable synthesis, and the contexts of the included studies should enable integration with the trials in the effectiveness analysis (see Figure 21.2.a ). The guiding principle is transparency in the reporting of all decisions and their rationale.

21.10 Selecting a qualitative evidence synthesis and data extraction method

Authors will typically find that they cannot select an appropriate synthesis method until the pool of available qualitative evidence has been thoroughly scoped. Flexible options concerning choice of method may need to be articulated in the protocol.

The INTEGRATE-HTA guidance on selecting methodology and methods for qualitative evidence synthesis and health technology assessment offers a useful starting point when selecting a method of synthesis (Booth et al 2016, Booth et al 2018). Some methods are designed primarily to develop findings at a descriptive level and thus directly feed into lines of action for policy and practice. Others hold the capacity to develop new theory (e.g. meta-ethnography and theory building approaches to thematic synthesis). Noyes and colleagues (Noyes et al (2019) and Flemming and colleagues (Flemming et al (2019) elaborate on key issues for consideration when selecting a method that is particularly suited to a Cochrane Review and decision making context (see Table 21.10.a ). Three qualitative evidence synthesis methods (thematic synthesis, framework synthesis and meta-ethnography) are recommended to produce syntheses that can subsequently be integrated with an intervention review or analysis.

Table 21.10.a Recommended methods for undertaking a qualitative evidence synthesis for subsequent integration with an intervention review, or as part of a mixed-method review (adapted from an original source developed by convenors (Flemming et al 2019, Noyes et al 2019))

|

|

|

|

| |

| Thematic synthesis (Thomas and Harden 2008) | Most accessible form of synthesis. Clear approach, can be used with ‘thin’ data to produce descriptive themes and with ‘thicker’ data to develop descriptive themes in to more in-depth analytic themes. Themes are then integrated within the quantitative synthesis. May be limited in interpretive ‘power’ and risks over-simplistic use and thus not truly informing decision making such as guidelines. Complex synthesis process that requires an experienced team. Theoretical findings may combine empirical evidence, expert opinion and conjecture to form hypotheses. More work is needed on how GRADE CERQual to assess confidence in synthesized qualitative findings (see Section ) can be applied to theoretical findings. May lack clarity on how higher-level findings translate into actionable points. |

|

| |

| Framework synthesis (Oliver et al 2008, Dixon-Woods 2011) Best-fit framework synthesis (Carroll et al 2011) | Works well within reviews of complex interventions by accommodating complexity within the framework, including representation of theory. The framework allows a clear mechanism for integration of qualitative and quantitative evidence in an aggregative way – see Noyes et al (2018a). Works well where there is broad agreement about the nature of interventions and their desired impacts. Requires identification, selection and justification of framework. A framework may be revealed as inappropriate only once extraction/synthesis is underway. Risk of simplistically forcing data into a framework for expedience. |

|

| |

| Meta-ethnography (Noblit and Hare 1988) | Primarily interpretive synthesis method leading to creation of descriptive as well as new high order constructs. Descriptive and theoretical findings can help inform decision making such as guidelines. Explicit reporting standards have been developed. Complex methodology and synthesis process that requires highly experienced team. Can take more time and resources than other methodologies. Theoretical findings may combine empirical evidence, expert opinion and conjecture to form hypotheses. May not satisfy requirements for an audit trail (although new reporting guidelines will help overcome this (France et al 2019). More work is needed to determine how CERQual can be applied to theoretical findings. May be unclear how higher-level findings translate into actionable points. |

21.11 Data extraction

Qualitative findings may take the form of quotations from participants, subthemes and themes identified by the study’s authors, explanations, hypotheses or new theory, or observational excerpts and author interpretations of these data (Sandelowski and Barroso 2002). Findings may be presented as a narrative, or summarized and displayed as tables, infographics or logic models and potentially located in any part of the paper (Noyes et al 2019).

Methods for qualitative data extraction vary according to the synthesis method selected. Data extraction is not sequential and linear; often, it involves moving backwards and forwards between review stages. Review teams will need regular meetings to discuss and further interrogate the evidence and thereby achieve a shared understanding. It may be helpful to draw on a key stakeholder group to help in interpreting the evidence and in formulating key findings. Additional approaches (such as subgroup analysis) can be used to explore evidence from specific contexts further.

Irrespective of the review type and choice of synthesis method, we consider it best practice to extract detailed contextual and methodological information on each study and to report this information in a table of ‘Characteristics of included studies’ (see Table 21.11.a ). The template for intervention description and replication TIDieR checklist (Hoffmann et al 2014) and ICAT_SR tool may help with specifying key information for extraction (Lewin et al 2017). Review authors must ensure that they preserve the context of the primary study data during the extraction and synthesis process to prevent misinterpretation of primary studies (Noyes et al 2019).

Table 21.11.a Contextual and methodological information for inclusion within a table of ‘Characteristics of included studies’. From Noyes et al (2019). Reproduced with permission of BMJ Publishing Group

|

|

|

| Context and participants | Important elements of study context, relevant to addressing the review question and locating the context of the primary study; for example, the study setting, population characteristics, participants and participant characteristics, the intervention delivered (if appropriate), etc. |

| Study design and methods used | Methodological design and approach taken by the study; methods for identifying the sample recruitment; the specific data collection and analysis methods utilized; and any theoretical models used to interpret or contextualize the findings. |

Noyes and colleagues (Noyes et al (2019) provide additional guidance and examples of the various methods of data extraction. It is usual for review authors to select one method. In summary, extraction methods can be grouped as follows.

- Using a bespoke universal, standardized or adapted data extraction template Review authors can develop their own review-specific data extraction template, or select a generic data extraction template by study type (e.g. templates developed by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (National Institute for Health Care Excellence 2012).

- Using an a priori theory or predetermined framework to extract data Framework synthesis, and its subvariant ‘Best Fit’ Framework approach, involve extracting data from primary studies against an a priori framework in order to better understand a phenomenon of interest (Carroll et al 2011, Carroll et al 2013). For example, Glenton and colleagues (Glenton et al (2013) extracted data against a modified SURE Framework (2011) to synthesize factors affecting the implementation of lay health worker interventions. The SURE framework enumerates possible factors that may influence the implementation of health system interventions (SURE (Supporting the Use of Research Evidence) Collaboration 2011, Glenton et al 2013). Use of the ‘PROGRESS’ (place of residence, race/ethnicity/culture/language, occupation, gender/sex, religion, education, socioeconomic status, and social capital) framework also helps to ensure that data extraction maintains an explicit equity focus (O'Neill et al 2014). A logic model can also be used as a framework for data extraction.

- Using a software program to code original studies inductively A wide range of software products have been developed by systematic review organizations (such as EPPI-Reviewer (Thomas et al 2010)). Most software for the analysis of primary qualitative data – such as NVivo ( www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/home ) and others – can be used to code studies in a systematic review (Houghton et al 2017). For example, one method of data extraction and thematic synthesis involves coding the original studies using a software program to build inductive descriptive themes and a theoretical explanation of phenomena of interest (Thomas and Harden 2008). Thomas and Harden (2008) provide a worked example to demonstrate coding and developing a new understanding of children’s choices and motivations to eating fruit and vegetables from included primary studies.

21.12 Assessing the confidence in qualitative synthesized findings

The GRADE system has long featured in assessing the certainty of quantitative findings and application of its qualitative counterpart, GRADE-CERQual, is recommended for Cochrane qualitative evidence syntheses (Lewin et al 2015). CERQual has four components (relevance, methodological limitations, adequacy and coherence) which are used to formulate an overall assessment of confidence in the synthesized qualitative finding. Guidance on its components and reporting requirements have been published in a series in Implementation Science (Lewin et al 2018).

21.13 Methods for integrating the qualitative evidence synthesis with an intervention review

A range of methods and tools is available for data integration or mixed-method synthesis (Harden et al 2018, Noyes et al 2019). As noted at the beginning of this chapter, review authors can integrate a qualitative evidence synthesis with an existing intervention review published on a similar topic (sequential approach), or conduct a new intervention review and qualitative evidence syntheses in parallel before integration (convergent approach). Irrespective of whether the qualitative synthesis is sequential or convergent to the intervention review, we recommend that qualitative and quantitative evidence be synthesized separately using appropriate methods before integration (Harden et al 2018). The scope for integration can be more limited with a pre-existing intervention review unless review authors have access to the data underlying the intervention review report.

Harden and colleagues and Noyes and colleagues outline the following methods and tools for integration with an intervention review (Harden et al 2018, Noyes et al 2019):

- Juxtaposing findings in a matrix Juxtaposition is driven by the findings from the qualitative evidence synthesis (e.g. intervention components related to the acceptability or feasibility of the interventions) and these findings form one side of the matrix. Findings on intervention effects (e.g. improves outcome, no difference in outcome, uncertain effects) form the other side of the matrix. Quantitative studies are grouped according to findings on intervention effects and the presence or absence of features specified by the hypotheses generated from the qualitative synthesis (Candy et al 2011). Observed patterns in the matrix are used to explain differences in the findings of the quantitative studies and to identify gaps in research (van Grootel et al 2017). (See, for example, (Ames et al 2017, Munabi-Babigumira et al 2017, Hurley et al 2018)

- Analysing programme theory Theories articulating how interventions are expected to work are analysed. Findings from quantitative studies, testing the effects of interventions, and from qualitative and process evaluation evidence are used together to examine how the theories work in practice (Greenhalgh et al 2007). The value of different theories is assessed or new/revised theory developed. Factors that enhance or reduce intervention effectiveness are also identified.

- Using logic models or other types of conceptual framework A logic model (Glenton et al 2013) or other type of conceptual framework, which represents the processes by which an intervention produces change provides a common scaffold for integrating findings across different types of evidence (Booth and Carroll 2015). Frameworks can be specified a priori from the literature or through stakeholder engagement or newly developed during the review. Findings from quantitative studies testing the effects of interventions and those from qualitative evidence are used to develop and/or further refine the model.

- Testing hypotheses derived from syntheses of qualitative evidence Quantitative studies are grouped according to the presence or absence of the proposition specified by the hypotheses to be tested and subgroup analysis is used to explore differential findings on the effects of interventions (Thomas et al 2004).

- Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) Findings from a qualitative synthesis are used to identify the range of features that are important for successful interventions, and the mechanisms through which these features operate. A QCA then tests whether or not the features are associated with effective interventions (Kahwati et al 2016). The analysis unpicks multiple potential pathways to effectiveness accommodating scenarios where the same intervention feature is associated both with effective and less effective interventions, depending on context. QCA offers potential for use in integration; unlike the other methods and tools presented here it does not yet have sufficient methodological guidance available. However, exemplar reviews using QCA are available (Thomas et al 2014, Harris et al 2015, Kahwati et al 2016).

Review authors can use the above methods in combination (e.g. patterns observed through juxtaposing findings within a matrix can be tested using subgroup analysis or QCA). Analysing programme theory, using logic models and QCA would require members of the review team with specific skills in these methods. Using subgroup analysis and QCA are not suitable when limited evidence is available (Harden et al 2018, Noyes et al 2019). (See also Chapter 17 on intervention complexity.)

21.14 Reporting the protocol and qualitative evidence synthesis

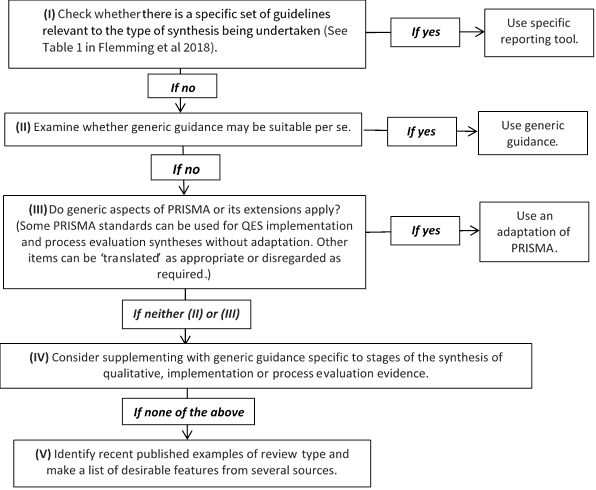

Reporting standards and tools designed for intervention reviews (such as Cochrane’s MECIR standards ( http://methods.cochrane.org/mecir ) or the PRISMA Statement (Liberati et al 2009), may not be appropriate for qualitative evidence syntheses or an integrated mixed-method review. Additional guidance on how to choose, adapt or create a hybrid reporting tool is provided as a 5-point ‘decision flowchart’ ( Figure 21.14.a ) (Flemming et al 2018). Review authors should consider whether: a specific set of reporting guidance is available (e.g. eMERGe for meta-ethnographies (France et al 2015)); whether generic guidance (e.g. ENTREQ (Tong et al 2012)) is suitable; or whether additional checklists or tools are appropriate for reporting a specific aspect of the review.

Figure 21.14.a Decision flowchart for choice of reporting approach for syntheses of qualitative, implementation or process evaluation evidence (Flemming et al 2018). Reproduced with permission of Elsevier

21.15 Chapter information

Authors: Jane Noyes, Andrew Booth, Margaret Cargo, Kate Flemming, Angela Harden, Janet Harris, Ruth Garside, Karin Hannes, Tomás Pantoja, James Thomas

Acknowledgements: This chapter replaces Chapter 20 in the first edition of this Handbook (2008) and subsequent Version 5.2. We would like to thank the previous Chapter 20 authors Jennie Popay and Alan Pearson. Elements of this chapter draw on previous supplemental guidance produced by the Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group Convenors, to which Simon Lewin contributed.

Funding: JT is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care North Thames at Barts Health NHS Trust. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

21.16 References

Ames HM, Glenton C, Lewin S. Parents' and informal caregivers' views and experiences of communication about routine childhood vaccination: a synthesis of qualitative evidence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017; 2 : CD011787.

Anderson LM, Petticrew M, Rehfuess E, Armstrong R, Ueffing E, Baker P, Francis D, Tugwell P. Using logic models to capture complexity in systematic reviews. Research Synthesis Methods 2011; 2 : 33-42.

Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2009; 9 : 59.

Benoot C, Hannes K, Bilsen J. The use of purposeful sampling in a qualitative evidence synthesis: a worked example on sexual adjustment to a cancer trajectory. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2016; 16 : 21.

Bonell C, Jamal F, Harden A, Wells H, Parry W, Fletcher A, Petticrew M, Thomas J, Whitehead M, Campbell R, Murphy S, Moore L. Public Health Research. Systematic review of the effects of schools and school environment interventions on health: evidence mapping and synthesis . Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2013.

Booth A, Harris J, Croot E, Springett J, Campbell F, Wilkins E. Towards a methodology for cluster searching to provide conceptual and contextual "richness" for systematic reviews of complex interventions: case study (CLUSTER). BMC Medical Research Methodology 2013; 13 : 118.

Booth A, Carroll C. How to build up the actionable knowledge base: the role of 'best fit' framework synthesis for studies of improvement in healthcare. BMJ Quality and Safety 2015; 24 : 700-708.

Booth A, Noyes J, Flemming K, Gerhardus A, Wahlster P, van der Wilt GJ, Mozygemba K, Refolo P, Sacchini D, Tummers M, Rehfuess E. Guidance on choosing qualitative evidence synthesis methods for use in health technology assessment for complex interventions 2016. https://www.integrate-hta.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Guidance-on-choosing-qualitative-evidence-synthesis-methods-for-use-in-HTA-of-complex-interventions.pdf

Booth A. Qualitative evidence synthesis. In: Facey K, editor. Patient involvement in Health Technology Assessment . Singapore: Springer; 2017. p. 187-199.

Booth A, Noyes J, Flemming K, Gehardus A, Wahlster P, Jan van der Wilt G, Mozygemba K, Refolo P, Sacchini D, Tummers M, Rehfuess E. Structured methodology review identified seven (RETREAT) criteria for selecting qualitative evidence synthesis approaches. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2018; 99 : 41-52.

Booth A, Moore G, Flemming K, Garside R, Rollins N, Tuncalp Ö, Noyes J. Taking account of context in systematic reviews and guidelines considering a complexity perspective. BMJ Global Health 2019a; 4 : e000840.

Booth A, Noyes J, Flemming K, Moore G, Tuncalp Ö, Shakibazadeh E. Formulating questions to address the acceptability and feasibility of complex interventions in qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Global Health 2019b; 4 : e001107.

Candy B, King M, Jones L, Oliver S. Using qualitative synthesis to explore heterogeneity of complex interventions. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2011; 11 : 124.

Cargo M, Harris J, Pantoja T, Booth A, Harden A, Hannes K, Thomas J, Flemming K, Garside R, Noyes J. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series-paper 4: methods for assessing evidence on intervention implementation. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2018; 97 : 59-69.

Carroll C, Booth A, Cooper K. A worked example of "best fit" framework synthesis: a systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2011; 11 : 29.

Carroll C, Booth A, Leaviss J, Rick J. "Best fit" framework synthesis: refining the method. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2013; 13 : 37.

Carroll C. Qualitative evidence synthesis to improve implementation of clinical guidelines. BMJ 2017; 356 : j80.

CASP. Making sense of evidence: 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research: Public Health Resource Unit, England; 2013. http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf .

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research 2012; 22 : 1435-1443.

Cooper C, Booth A, Britten N, Garside R. A comparison of results of empirical studies of supplementary search techniques and recommendations in review methodology handbooks: a methodological review. Systematic Reviews 2017; 6 : 234.

De Buck E, Hannes K, Cargo M, Van Remoortel H, Vande Veegaete A, Mosler HJ, Govender T, Vandekerckhove P, Young T. Engagement of stakeholders in the development of a Theory of Change for handwashing and sanitation behaviour change. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018; 28 : 8-22.

Dixon-Woods M. Using framework-based synthesis for conducting reviews of qualitative studies. BMC Medicine 2011; 9 : 39.

Downe S, Finlayson K, Tuncalp, Metin Gulmezoglu A. What matters to women: a systematic scoping review to identify the processes and outcomes of antenatal care provision that are important to healthy pregnant women. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2016; 123 : 529-539.

El Sherif R, Pluye P, Gore G, Granikov V, Hong QN. Performance of a mixed filter to identify relevant studies for mixed studies reviews. Journal of the Medical Library Association 2016; 104 : 47-51.

Flemming K, Booth A, Hannes K, Cargo M, Noyes J. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series-paper 6: reporting guidelines for qualitative, implementation, and process evaluation evidence syntheses. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2018; 97 : 79-85.

Flemming K, Booth A, Garside R, Tuncalp O, Noyes J. Qualitative evidence synthesis for complex interventions and guideline development: clarification of the purpose, designs and relevant methods. BMJ Global Health 2019; 4 : e000882.

France EF, Ring N, Noyes J, Maxwell M, Jepson R, Duncan E, Turley R, Jones D, Uny I. Protocol-developing meta-ethnography reporting guidelines (eMERGe). BMC Medical Research Methodology 2015; 15 : 103.

France EF, Cunningham M, Ring N, Uny I, Duncan EAS, Jepson RG, Maxwell M, Roberts RJ, Turley RL, Booth A, Britten N, Flemming K, Gallagher I, Garside R, Hannes K, Lewin S, Noblit G, Pope C, Thomas J, Vanstone M, Higginbottom GMA, Noyes J. Improving reporting of Meta-Ethnography: The eMERGe Reporting Guidance BMC Medical Research Methodology 2019; 19 : 25.

Garside R. Should we appraise the quality of qualitative research reports for systematic reviews, and if so, how? Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 2014; 27 : 67-79.

Glenton C, Colvin CJ, Carlsen B, Swartz A, Lewin S, Noyes J, Rashidian A. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of lay health worker programmes to improve access to maternal and child health: qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013; 10 : CD010414.

Glenton C, Lewin S, Norris S. Chapter 15: Using evidence from qualitative research to develop WHO guidelines. In: Norris S, editor. World Health Organization Handbook for Guideline Development . 2nd. ed. Geneva: WHO; 2016.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal 2009; 26 : 91-108.

Greenhalgh T, Kristjansson E, Robinson V. Realist review to understand the efficacy of school feeding programmes. BMJ 2007; 335 : 858.

Harden A, Oakley A, Weston R. A review of the effectiveness and appropriateness of peer-delivered health promotion for young people. London: Institute of Education, University of London; 1999.

Harden A, Thomas J, Cargo M, Harris J, Pantoja T, Flemming K, Booth A, Garside R, Hannes K, Noyes J. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series-paper 5: methods for integrating qualitative and implementation evidence within intervention effectiveness reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2018; 97 : 70-78.

Harris JL, Booth A, Cargo M, Hannes K, Harden A, Flemming K, Garside R, Pantoja T, Thomas J, Noyes J. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series-paper 2: methods for question formulation, searching, and protocol development for qualitative evidence synthesis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2018; 97 : 39-48.

Harris KM, Kneale D, Lasserson TJ, McDonald VM, Grigg J, Thomas J. School-based self management interventions for asthma in children and adolescents: a mixed methods systematic review (Protocol). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015; 4 : CD011651.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, Altman DG, Barbour V, Macdonald H, Johnston M, Lamb SE, Dixon-Woods M, McCulloch P, Wyatt JC, Chan AW, Michie S. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014; 348 : g1687.

Houghton C, Murphy K, Meehan B, Thomas J, Brooker D, Casey D. From screening to synthesis: using nvivo to enhance transparency in qualitative evidence synthesis. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2017; 26 : 873-881.

Hurley M, Dickson K, Hallett R, Grant R, Hauari H, Walsh N, Stansfield C, Oliver S. Exercise interventions and patient beliefs for people with hip, knee or hip and knee osteoarthritis: a mixed methods review. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018; 4 : CD010842.

Kahwati L, Jacobs S, Kane H, Lewis M, Viswanathan M, Golin CE. Using qualitative comparative analysis in a systematic review of a complex intervention. Systematic Reviews 2016; 5 : 82.

Kelly MP, Noyes J, Kane RL, Chang C, Uhl S, Robinson KA, Springs S, Butler ME, Guise JM. AHRQ series on complex intervention systematic reviews-paper 2: defining complexity, formulating scope, and questions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2017; 90 : 11-18.

Kneale D, Thomas J, Harris K. Developing and Optimising the Use of Logic Models in Systematic Reviews: Exploring Practice and Good Practice in the Use of Programme Theory in Reviews. PloS One 2015; 10 : e0142187.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science 2010; 5 : 69.

Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Daniels K, Bosch-Capblanch X, van Wyk BE, Odgaard-Jensen J, Johansen M, Aja GN, Zwarenstein M, Scheel IB. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010; 3 : CD004015.

Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Carlsen B, Colvin CJ, Gulmezoglu M, Noyes J, Booth A, Garside R, Rashidian A. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: an approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Medicine 2015; 12 : e1001895.

Lewin S, Hendry M, Chandler J, Oxman AD, Michie S, Shepperd S, Reeves BC, Tugwell P, Hannes K, Rehfuess EA, Welch V, McKenzie JE, Burford B, Petkovic J, Anderson LM, Harris J, Noyes J. Assessing the complexity of interventions within systematic reviews: development, content and use of a new tool (iCAT_SR). BMC Medical Research Methodology 2017; 17 : 76.

Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Rashidian A, Wainwright M, Bohren MA, Tuncalp O, Colvin CJ, Garside R, Carlsen B, Langlois EV, Noyes J. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implementation Science 2018; 13 : 2.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009; 339 : b2700.

Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Harderman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015; 350 : h1258.

Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Lewin S, Fretheim A, Nabudere H. Factors that influence the provision of intrapartum and postnatal care by skilled birth attendants in low- and middle-income countries: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017; 11 : CD011558.

Munthe-Kaas H, Glenton C, Booth A, Noyes J, Lewin S. Systematic mapping of existing tools to appraise methodological strengths and limitations of qualitative research: first stage in the development of the CAMELOT tool. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2019; 19 : 113.

National Institute for Health Care Excellence. NICE Process and Methods Guides. Methods for the Development of NICE Public Health Guidance . London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2012.

Newton BJ, Rothlingova Z, Gutteridge R, LeMarchand K, Raphael JH. No room for reflexivity? Critical reflections following a systematic review of qualitative research. Journal of Health Psychology 2012; 17 : 866-885.

Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies . Newbury Park: Sage Publications, Inc; 1988.

Noyes J, Hendry M, Booth A, Chandler J, Lewin S, Glenton C, Garside R. Current use was established and Cochrane guidance on selection of social theories for systematic reviews of complex interventions was developed. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2016a; 75 : 78-92.

Noyes J, Hendry M, Lewin S, Glenton C, Chandler J, Rashidian A. Qualitative "trial-sibling" studies and "unrelated" qualitative studies contributed to complex intervention reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2016b; 74 : 133-143.