Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.2–Nonfiction Genres

Matt McKinney

As other chapters have pointed out, genres provide writers with structural templates and conventions that they can choose to adhere to or deviate from. Most readers are familiar with genre conventions and structures, and come to expect that writers will decide either to follow them or break them creatively. These decisions are the first indicator that nonfiction writers must make creative choices, just as fiction writers do. Here are some of the more prevalent genres in nonfiction.

Autobiographies & Memoirs

While most people are aware that autobiographies and memoirs are nonfiction texts that focus on the author’s life, these words are not inherently interchangeable; instead, they represent an important creative choice that the writer made regarding what to emphasize in their life and how to structure it.

An autobiography always covers the entirety of the author’s life, from birth until the present day. This focus entails a chronological structure, and also predisposes the writer to frame every phase of their life as thematically significant for one reason or another. An author’s decision to cover the full extent of their life might suggest a desire to appear authentic to their audience (i.e. by not simply providing a highlight reel of their biggest accomplishments). It could also indicate that the author wants to contextualize their greatest or most famous accomplishments, so that the reader can see the struggles they endured or the formative moments they went through to get to their current status. Further still, the full scope of the author’s life might call attention to a part of themselves that’s less well-known but that they want their audience to understand. An autobiography can also be an author’s attempt to take stock of their lives and form a narrative from it. Any and all of these motivations can inform the author’s decision to write an autobiography.

Memoirs, by contrast, differ in that they only focus on a select part of an author’s life. This narrower focus could be because the author wants to focus on a particularly formative or famous (or infamous) experience in their life. Some memoirs, like David Sedaris’s works, are collections of memories, with each chapter covering an experience that ties to a larger theme about the author as a person or their outlook on life. Whether an author chooses to frame their life in an autobiography or a memoir, and regardless of their approach to either genre or their motive in crafting their text, none of these choices alter the fact that the author is focusing on real events (or at least their perception of them). As concrete and limited as nonfiction may appear in comparison to fiction, there is still quite a range of creative possibilities in this one genre.

Biographies

Though the focus of a biography is identical to that of an autobiography in that it is an account of someone’s life, biographies differ in that the author is writing about someone else’s life, and this entails an entirely different array of creative choices. To begin with, a famous person or historical figure often has multiple biographies written about them over long stretches of time, so a biographical author must focus on research in order to avoid libel and potential litigation. They also must establish their work as definitive or unique in comparison to other biographies.

For example, let’s say an author decides to write a biography about Robert E. Lee. Is the biography going to focus largely on his military career during the Civil War (as most Lee biographies do)? Will it focus on earlier times in his life (his childhood, time at West Point, the Mexican-American War), or during Reconstruction? Will it focus on more negative aspects of his legacy, such as his white supremacist beliefs and treatment of the enslaved Black Americans he owned? Will it review and critique prior biographies on Lee, or will it focus on new historical evidence? The author’s answers to these questions will have the largest impact on how they craft this nonfiction text.

Similar to fictional works of literature, many nonfiction essays address themes of social, historical, and cultural identity and character. Unlike fictional works, which often explore these ideas through allegory or characters, essays give authors the ability to address readers more directly, frame contemporary issues in a variety of aspects (from ironic satire to direct calls to action), and also craft a mutual collective identity with the readers whom these writers want to reach. For example, two prominent authors of fiction, Dorothy Parker and Mark Twain, simultaneously published non-fictional satire and social commentary on contemporary events.

In other cases, some essays’ influence has been so pervasive that they led to the creation of new genres. For example, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood , originally composed as a series of essays rather than a novel, is often credited with inspiring the true crime genre that emerged after its publication.

Similar to essays, speeches narrow the gap between a writer, their audiences, and contemporary events. In fact, speeches often narrow this gap even more so than essays. This is not only because they tend to respond to a more specific exigence than other nonfiction forms of literature, but also because they are either composed orally or meant to be read aloud at a specific moment in time.

The second nonfiction text that this chapter will focus on, Frederick Douglass’s “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July,” was prepared to be read at a specific event: an 1852 meeting of the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society in New York. Because of the speech’s import regarding the culture, history, and legacy of the United States, however, we continue to read it today and find it remains relevant in critiquing the white supremacist legacy of the nation.

Letters/Correspondence

Letters and correspondence (often from or between writers) can also be considered forms of nonfiction literature. More intimate than most of the other genres listed here, correspondence is shaped by the relationship between the writer and, usually, an audience of one. Letters exchanged form exigencies for one another (i.e., receiving a letter inspires the writing of another in response, and so on), and writers often employ the same tropes, schemes, and other literary elements that they might use in fiction. This includes point of view, diction, figurative language, symbolism, etc.

Additionally, literary correspondence can provide essential context for studying a fictional work, such as when an author writes to a literary critic or a loved one about a text. Mark Twain, for instance, frequently wrote letters to his publishers–enough for them to be published into their own collection, Mark Twain’s Letters to His Publishers .

Study Questions for Nonfiction Genre Categories

- What genres of nonfiction cater to the broadest audiences, and which seem the most intimate? Why?

- What should a nonfiction writer consider when choosing a genre for their text?

- Take a look at the “Spotlight” section below. In terms of composition, what are some important ways an essay like Thomas Paine’s typically differs from a speech like Frederick Douglass’s?

Attribution:

McKinney, Matt. “Literary Nonfiction: Nonfiction Genres.” In Surface and Subtext: Literature, Research, Writing . 3rd ed. Edited by Claire Carly-Miles, Sarah LeMire, Kathy Christie Anders, Nicole Hagstrom-Schmidt, R. Paul Cooper, and Matt McKinney. College Station: Texas A&M University, 2024. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License .

8.2--Nonfiction Genres Copyright © 2024 by Matt McKinney is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

What Is Nonfiction: Definition and Examples

Sarah Oakley

Table of Contents

What is nonfiction, is nonfiction a genre, what is a nonfiction book example, how prowritingaid can help you write nonfiction.

Nonfiction writing has become one of the most popular genres of books published today. Most nonfiction books are about modern day problems, science, or details of actual events and lives.

If you’re looking for informative writing made up of factual details rather than fiction, nonfiction is a great option. It serves to develop your knowledge about different topics, and it helps you learn about real events.

In this article, we’ll explain what nonfiction is, what to expect from the nonfiction genre, and some examples of nonfiction books.

If you’re considering writing a book, and you can’t decide between fiction or nonfiction , it helps to know exactly what nonfiction is first.

Similarly, if you want to indulge in some self-development, and you decide to read some books, you’ll need to know what to look for in a nonfiction book to ensure you’re reading factual content.

Nonfiction Definition

To define the word nonfiction, we can break it down into two parts. “Non” is a prefix that means the absence of something. “Fiction” means writing that features ideas and elements purely from the author’s imagination.

Therefore, when you put those two definitions together, it suggests nonfiction is the absence of writing that comes from someone’s imagination. To put it in a better way, nonfiction is about facts and evidence rather than imaginary events and characters who don’t exist.

Nonfiction Meaning

As nonfiction writing sounds like the opposite of fiction writing, you might think nonfiction is all true and objective, but that’s not the case. While nonfiction writing contains factual elements, such as real people, concepts, and events, it’s not always objectively true accounts.

A lot of nonfiction writing is opinionated or biased discussions about the subject of the writing.

For example, you might be a football expert, and you want to write a book about the top goal scorers of 2022. Your piece could be objective and discuss exactly who scored the most goals in 2022, or you could add some opinions and discuss who scored the best goals or who performed the best on the pitch.

Opinions make nonfiction books more unique to the author, as it sounds more authentic and human because we all have our own thoughts and feelings about things.

Adding opinions can also make nonfiction books more interesting for readers, as you can be more controversial or use exaggeration to increase reader engagement. Many readers like to pick up books that challenge their thoughts about certain topics.

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Nonfiction is a genre, but it’s more of an umbrella term for several reference and factual genres. When you’re in the nonfiction section of a bookstore or library, you’ll find the books in categories based on the overall theme or topic of the book.

There are several categories of nonfiction:

Biographies, autobiographies, and memoirs

Travel writing and travel guides

Academic journals

Philosophical and modern social science

Journalism and news media

Self-help books

How-to guides

Humorous books

Reference books

Historical, academic, reference, philosophical, and social science books often focus on factual representations of information about specific subjects, events, and key ideas. The tone of these books is often more formal, though there are some informal examples available.

Biography , memoir, travel writing, humor, and self-help books are creative nonfiction. This means they’re based on true events and stories, but the writer uses a lot more creative freedom to tell stories and pass on information about what they have learned from life.

Readers often criticize journalism and news media for not being objectively truthful when telling people about events. However, almost all journalism is biased or opinionated in one way or another. Therefore, it’s good to read from multiple different sources for your news updates.

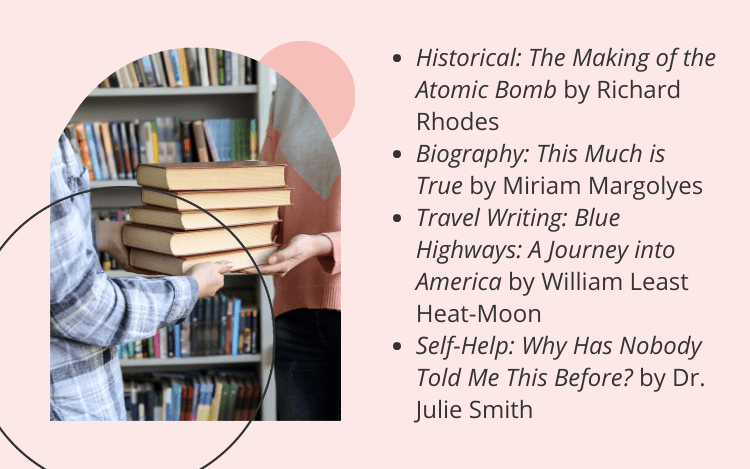

If you want to read nonfiction to get an idea of what it’s like, we’ve got several examples of great nonfiction books for you to check out.

Historical : The Making of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes

Biography : This Much is True by Miriam Margolyes

Travel Writing : Blue Highways: A Journey into America by William Least Heat-Moon

Philosophical : The Alignment Problem: How Can Machines Learn Human Values? By Brian Christian

Self-Help : Why Has Nobody Told Me This Before? By Dr. Julie Smith

Humor : What If?: Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions by Randall Munroe

If you want to write nonfiction, you can use ProWritingAid to ensure you avoid publishing a manuscript full of grammatical errors. Whether you’re looking for a second pair of eyes catching quick fixes as you write, or a full analysis of your manuscript once it’s written, ProWritingAid has you covered.

You can use the Realtime checker to see suggested improvements to your writing as you’re working. If you use the in-tool learning features as well, you’ll see fewer suggestions as you write because it’ll essentially train you to become a better writer.

If you’re more of a full-blown analysis editor, try using the Readability report to see suggestions highlighting where you can improve your writing to ensure more readers can understand what you’re saying. Readability is important if you want to reach more readers who have different levels of reading comprehension.

Another great report you can use for nonfiction writing is the Transitions report. Transitions are the words that show cause and effect within your writing. If you want your reader to follow your points and arguments, you need to include plenty of transitions to improve the flow of your writing.

Now that you know what nonfiction means and how ProWritingAid can help you produce a great nonfiction book, try nonfiction writing , and see how fun it is to share your knowledge and opinions with the world. Just don’t forget to check your work is factual and relevant.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Fiction vs. nonfiction?

Nonfiction writing recounts real experiences, people, and periods. Fiction writing involves imaginary people, places, or periods, but it may incorporate story elements that mimic reality.

Your writing, at its best

Compose bold, clear, mistake-free, writing with Grammarly's AI-powered writing assistant

What is the difference between fiction and nonfiction ?

The terms fiction and nonfiction represent two types of literary genres, and they’re useful for distinguishing factual stories from imaginary ones. Fiction and nonfiction writing stand apart from other literary genres ( i.e., drama and poetry ) because they possess opposite conventions: reality vs. imagination.

What is fiction ?

Fiction is any type of writing that introduces an intricate plot, characters, and narratives that an author invents with their imagination. The word fiction is synonymous with terms like “ fable ,” “ figment ,” or “ fabrication ,” and each of these words has a collective meaning: falsehoods, inventions, and lies.

Not all fiction is entirely made-up, though. Historical fiction, for example, features periods with real events or people, but with an invented storyline. Additionally, science fiction novels function around real scientific theories, but the overall story is untrue.

What is nonfiction ?

Nonfiction is any writing that represents factual accounts on past or current events. Authors of nonfiction may write subjectively or objectively, but the overall content of their story is not invented (Murfin 340).

Works of nonfiction are not limited to traditional books, either. Additional examples of nonfiction include:

- Instruction manuals

- Safety pamphlets

- Journalism

- Recipes

- Medical charts

Comparing fiction and nonfiction texts

Outside of reality vs. imagination, nonfiction and fiction writing possess several typical features.

Fictional text features:

- Imaginary characters, settings, or periods

- A subjective narrative

- Novels, novellas, and short stories

- Literary fiction vs. genre fiction ( e.g., sci-fi, romance, mystery )

Nonfiction text features:

- Real people, events, and periods

- An authoritative narrative

- Autobiographies, letters, journals, essays, etc .

- Venn diagrams, anchor charts, mini-lessons, extension activities

- Index, citations, and bibliographies

- Academic/peer-reviewed publishers

What does fiction and nonfiction have in common?

Oftentimes, an elaborate work of fiction has more in common with nonfiction than a simple fairy tale or children’s book. Examples of shared traits include:

- Major literary publishers ( e.g., Hachette Books and HarperCollins )

- Photographic and illustrated book covers

- Stylistic elements such as an index, glossary, or citations

- Themes involving history, mythology, and science

- Creative prose narratives

Prose narratives of fiction vs. nonfiction

According to The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms , we can narrowly distinguish fiction from nonfiction through the use of “prose narratives,” a term that refers to an author’s storytelling form.

For works of fiction , authors typically use prose narratives such as the novel , novella , or short story . But for nonfiction books, prose narratives take the form of biographies , expository , letters , essays, and more.

Prose narratives of fiction

A novel is a long, fictional story that involves several characters with an established motivation, different locations, and an intricate plot. Examples of novels include:

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Beloved by Tony Morrison

A novel is not the same as a novella , which is a shorter fictional account that ranges between 50-100 pages long. You’ve likely heard of novellas such as:

- Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad

- Animal Farm by George Orwell

Lastly, the short story normally contains 1,000-10,000 words and focuses on one event or length of time, such as:

- The Cask of Amontillado by Edgar Allen Poe

- The Story of an Hour by Kate Chopin

Prose narratives of nonfiction

Since nonfiction represents real people, experiences, or events, the most common prose narratives of nonfiction include:

- Biographies

- Autobiographies

- Journals

- Essays

- Informational texts

Biographies and autobiographies

A biography is written about another person, while an autobiography’s author tells the story of their own life. Popular biographies include:

- Into the Wild by Jon Krakauer

- Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson

The difference between the two modes of nonfiction is further illustrated with autobiographies such as:

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass by Frederick Douglass

- I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood up for Education and Was Shot by Malala Yousafzai

Journals and letters

Journals , diaries , and letters provide a glimpse into someone’s life at a particular moment. Diaries and letters are great resources for historical contexts, and especially for periods involving war or political scandals.

Journal and letters examples:

- The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

- Ever Yours: The Essential Letters by Vincent van Gogh

Essay writing

By definition, an essay is a short piece of writing that explores a specific subject, such as philosophy, science, or current events. We read essays within magazines, websites, scholarly journals, or through a published collection of essays.

Essay examples:

- Consider the Lobster by David Foster Wallace

- The Source of Self-Regard by Toni Morrison

Informational texts

Informational texts present clear, objective facts about a particular subject, and often take the form of periodicals, news articles, textbooks, printables, or instruction manuals. The difference between informational texts and biographical writing is that biographies possess a range of subjectivity toward a topic, while informational writing is purely educational.

Publishers of informational texts also tailor their writing toward an audience’s reading comprehension. For instance, instructions for first-grade reading levels use different vocabularies than a textbook for college students. The key similarity is that informational writing is clear and educational.

Genres of fiction vs. nonfiction

The French term genre means “kind” or “type,” and genres organize different styles, forms, or subjects of literature. Some sources believe fiction is categorized by genre fiction and literary fiction , while others believe that literary fiction is a subgenre of fiction itself. The same arguments exist within nonfiction genres, except nonfiction is organized by subject matter or writing style.

Whichever way you look at it, all nonfiction and fiction have distinct genres and subgenres that overlap, and there’s no single way to categorize literature without spurring controversy. If you’re ever doubtful about a particular book, try checking the publisher’s website.

What is literary fiction ?

If we stick to the dry characteristics of literary fiction , we can define it as any writing that produces an underlying commentary on the human condition. More specifically, literary fiction often involves a metaphorical , poetic narrative or critique around topics such as war, gender, race, sex, economy, or political ideologies.

Literary fiction examples:

- Quicksand by Nella Larsen

- The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera

- The Sellout by Paul Beatty

What is genre fiction ?

Broadly speaking, genre fiction (or popular fiction ) is any writing with a specific theme and the author’s marketability toward a particular audience (aka, the novel is likely a part of a book series). The most common genres of “ genre fiction ” include:

- Science Fiction

- Suspense/Thriller

Crime fiction and mystery

Crime fiction and mystery novels focus on the motivation of police, detectives, or criminals during an investigation. Four major subgenres of crime fiction and mystery include detective novels, cozy mysteries, caper stories, and police procedurals.

Crime fiction and mystery examples:

- The Godfather by Mario Puzo

- The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by Steig Larsson

The fantasy genre traditionally occurs in medieval-esque settings and often includes mythical creatures such as wizards, elves, and dragons.

Fantasy examples:

- The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkein

- A Game of Thrones by George R.R. Martin

The romance genre features stories about romantic relationships with a focus on intimate details. Romance themes often involve betrayal or heroism and elements of sensuality, idealism, morality, and desire.

Romance examples:

- Dead Until Dark by Charlaine Harris

- Fifty Shades of Grey by E.L. James

Science fiction

Science fiction is one of the largest growing genres because it encompasses several subgenres, such as dystopian, apocalyptic, superhero, or space travel themes. All sci-fi novels incorporate real or imagined scientific concepts within the past, future, or a different dimension of time.

Science fiction examples:

- Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler

- The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin

Suspense and horror

Sometimes described as two separate genres, suspense and horror writing focuses on the pursuit and escape of a main character or villain. Suspense writing uses cliffhangers to “grip” readers, but we can distinguish the horror genre through supernatural, demonic, or occult themes.

Suspense and horror examples:

- The Silence of the Lambs by Thomas Harris

- The Shining by Stephen King

Genres of nonfiction

Finally, we meet again in the nonfiction section. When it comes to nonfiction literature, the most common genres include:

- Autobiography/Biography (see “prose narratives” )

Narrative nonfiction

A memoir recounts the memories and experiences for a specific timeline in an author’s life. But unlike an autobiography, a memoir is less chronological and depends on memories and emotions rather than fact-checked research.

Memoir examples:

- Wild by Cheryl Strayed

- When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi

Self-help writing focuses on delivering a lesson plan for self-improvement. Authors of self-help books describe experiences like a memoir, but the overall purpose is to teach readers a skill that the author possesses.

Self-help examples:

- How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie

- The Power of Now by Eckhart Tolle

The expository genre introduces or “ exposes ,” a complex subject to readers in an understandable manner. Expository books often take the form of children’s books to provide a clear, educational summary on topics such as history and science.

Examples of adult vs. children’s expository books include:

- Death by Black Hole by Neil deGrasse Tyson

- A Black Hole is Not a Hole by Carolyn Cinami Decristofano

Narrative nonfiction (or “ creative nonfiction ”) tells a true story in the form of literary fiction. In this case, the author presents an autobiography or biography with an emphasis on storytelling over chronology.

The line between creative nonfiction and literary fiction is thin when the narrative’s presentation is too subjective, and when specific facts are omitted or exaggerated. Literary scholars refer to such works as “ faction ,” a portmanteau word for writing that blurs the line between fiction and nonfiction (Murfin 177).

Narrative nonfiction examples:

- In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

- The Devil in the White City by Erik Larson

Additional resources for nonfiction vs. fiction ?

Understanding the elements of fiction vs. nonfiction writing is a common core standard for language arts (ELA) programs. If you’re looking to learn specific forms of fiction and nonfiction writing, The Word Counter provides additional articles, such as:

- Transition Words: How, When, and Why to Use Them

- What Are the Most Cringe-Worthy English Grammar Mistakes?

- Italics and Underlining: Titles of Books

Test Yourself!

Before you visit your next writing workshop, class discussion, or literacy center, test how well you understand the difference between fiction and nonfiction with the following multiple-choice questions (no peeking into Google!)

- True or false: An author’s imagination does not invent nonfiction writing. a. True b. False

- Which term is synonymous with fiction? a. Fact b. Fable c. Reality d. None of the above

- Which is a type of nonfiction writing? a. Novels b. Memoirs c. Novellas d. Short stories

- Which is not a trait of literary fiction? a. Underlying commentary on the human condition b. Poetic narrative c. Social and political commentary d. None of the above

- Which genre of nonfiction is the closest to literary fiction? a. Memoirs b. Expository c. Narrative nonfiction d. Self-help

Photo credits:

[1] Photo by Suad Kamardeen on Unsplash [2] Photo by Jonathan J. Castellon on Unsplash

- “ Essay .” Lexico , Oxford University Press, 2020.

- “ Fiction .” The Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster Inc., 2020.

- MasterClass. “ What Is the Mystery Genre? Learn About Mystery and Crime Fiction, Plus 6 Tips for Writing a Mystery Novel .” MasterClass , 15 Aug 2019.

- Mazzeo, T.J. “ Writing Creative Nonfiction .” The Great Courses , 2012, pp.4.

- Murfin, R., Supryia M. Ray. “ The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms .” Third Ed, Bedford/St. Martins , 2009, pp. 177-340.

- “ Nonfiction .” Lexico , Oxford University Press, 2020.World Heritage Encyclopedia. “ List of Literary Genres .” World Library Foundation , 2020.

Alanna Madden

Alanna Madden is a freelance writer and editor from Portland, Oregon. Alanna specializes in data and news reporting and enjoys writing about art, culture, and STEM-related topics. I can be found on Linkedin .

Recent Posts

Allude vs. elude, bad vs. badly, labor vs. labour, adaptor vs. adapter.

Automated page speed optimizations for fast site performance

Why We Call It “Creative Nonfiction”

A genre by any other name? The story behind the term "creative nonfiction"

For as long as the term creative nonfiction has existed, people have questioned how well the expression captures what writers actually do in the genre, and more than a few have wondered why in heaven’s name we started using the term in the first place. I’ve probably spent roughly half my waking hours over the past twenty years trying, variously, to justify, replace, or explain the unsatisfying label. That may be a slight exaggeration, but if you’ve ever been to a writers’ conference, you know how often the question comes up.

In response, I’ve decided to track down the culprits who gave us creative nonfiction —and to do it here, in the very magazine that bears the name.

First, though, let’s revisit a few of the complaints:

Essayist Phillip Lopate didn’t hold back in a 2008 Poets & Writers interview, characterizing the term as “slightly bogus,” then adding, “It’s like patting yourself on the back and saying, ‘My nonfiction is creative.’ Let the reader be the judge of that.”

The second word— nonfiction —doesn’t fare much better. “It’s always seemed odd to me that nonfiction is defined, not by what it is, but by what it is not,” Philip Gerard complains in his craft book, Creative Nonfiction: Researching and Crafting Stories of Real Life . “It is not fiction. But then again, it is also not poetry, or technical writing or libretto. It’s like defining classical music as nonjazz . Or sculpture as nonpainting .”

Few seem willing to embrace the term, though by this point, almost everyone uses it. Alternatives have been trotted out, but none has taken hold.

For instance, the phrase literary nonfiction has a nice ring to it but risks sounding a bit pretentious. As Lopate might say, let the reader decide.

Narrative nonfiction works for the more journalistic end of the nonfiction spectrum, but it is a poor fit for meditative or lyric essays.

John McPhee has occasionally used the term literature of fact , but that’s a mouthful and also falls short of describing the breadth of the genre.

So creative nonfiction is here to stay, it seems, but how did we get here, and why does no one want to take credit for giving us this awkward term in the first place?

Another Poets & Writers article, from 2009, exploring the distinctions between creative nonfiction and traditional journalism, calls me out for something stupid I may or may not have said at an AWP Panel (yes, it’s personal), then points a finger directly at Creative Nonfiction magazine founder Lee Gutkind:

“Although he’s attained his own reputation as a creative nonfiction apostle, Moore was originally a disciple of the man credited with coining the term creative nonfiction, Lee Gutkind, who taught a class with those words in its title at the University of Pittsburgh as early as 1973.”

Some of that is true, but most of it is hogwash. Though Lee is often credited with (or blamed for) coining the term, he didn’t.

The misperception stems, perhaps, from a 1997 Vanity Fair article wherein Lee was dubbed “the godfather behind creative nonfiction” by critic James Wolcott, who did not intend that title to be in any way flattering. You be the judge: the caption to an accompanying illustration reads, “NAVEL GAZERS. For writers Lee Gutkind, Phillip Lopate, Laurie Stone, Daphne Merkin, and Anne Roiphe, no personal detail is too mundane to share.”

Wolcott, of course, went on to publish his own memoir eventually. If you ask me, his nonfiction is fairly creative (and his navel extremely well-gazed).

The point is, Lee didn’t invent the name, though he did, of course launch the magazine you are reading right now. When I asked him to clarify his understanding of where the term came from, he confessed to being entirely unsure. “In the ’70s, I tried to find a term suitable to my colleagues so they would allow me to teach courses in the genre,” he wrote in response to my query. “For a while it was called new journalism , but the J word was unacceptable in English departments.”

I can attest to that, since I was Lee’s student back in the mid-1970s (I told you it was personal), and new journalism was indeed the term being bandied about.

Lee remembers strategizing with his mentor Montgomery Culver, searching for a way to define “what was so different about what I was doing and what I could teach writing students that feature writers and journalists couldn’t.

“At the time, both Monty and I agreed that we had somehow, somewhere, heard the term [ creative nonfiction ] before,” Lee explained, “but [we] hadn’t the slightest idea when or where or from whom.”

Michael Steinberg, editor of the anthology The Fourth Genre (and, later, the literary journal of almost the same name), recalls that Creative Nonfiction’s front cover may have been the first place he saw the term. His best guess, he told me, was that Lee may have adopted the label from the National Endowment for the Arts.

But if Lee first heard the term sometime in the 1970s, it wasn’t from the NEA. “‘Creative nonfiction’ was added to the prose guidelines for FY1990 fellowships,” the NEA’s Rebecca Maner wrote me when I started digging. Prior to that year, she added, the nonfiction genre was listed as “belles-lettres.”

( Belles-lettres ? You don’t have to like the term creative nonfiction, but, hey, it could be worse.)

Joe Mackall, cofounder of River Teeth , believes he heard the term in the late 1980s but has “no memory of where or from whom.”

Sue William Silverman, winner—in 1995—of the AWP Book Award for Creative Nonfiction, tells me she hadn’t ever heard the term until she submitted her book a year earlier for the contest.

No one, it seems, could recall where they heard it first, so I launched my own investigation. The earliest use Google turns up is from 1984. The earliest hit from LexisNexis harks back to 1981, when Phyllis Grosskurth’s biography, Havelock Ellis , won the Arts Council of Great Britain’s “creative non-fiction” book prize.

Michael Stephens, writing in Creative Nonfiction #2, takes it back a bit further, recalling his teacher, the late Seymour Krim, saying that J. R. “Dick” Humphreys, founder of the writers’ program at Columbia University, coined the expression in the late 1970s to describe a new course Krim was planning to teach. The idea was to signal that this was a “creative” writing course, not journalism or expository writing.

But it goes back even further. I dove into various online academic databases and discovered the term might have originated on the very campus where I currently direct one of the few PhD programs that include the creative nonfiction genre. (Yes: still personal.)

The earliest use of the term seems to be in a review of Frank Conroy’s Stop-Time, written by David Madden—a scholar, writer, and professor here in Ohio from 1966 to 1968. In the review, which can be found in the 1969 Survey of Contemporary Literature , Madden calls for a “redefinition” of nonfiction writing in the wake of Truman Capote, Jean Stafford, and Norman Mailer, then turns to a brief discussion of Norman Podhoretz. “In Making It, Norman Podhoretz, youthful editor of Commentary, who declares that creative nonfiction is pre-empting the functions of fiction, offers his own life as evidence,” Madden writes.

What Podhoretz actually said in his memoir, or intellectual autobiography, was that he “did not believe . . . that fiction was the only kind of writing which deserved to be called ‘creative.’ . . . But the truth was that the American books of the postwar period which had mattered to me personally, and not to me alone either, . . . were not novels . . . but works the trade quaintly called ‘nonfiction,’ as though they had only a negative existence.”

Podhoretz, it seems, anticipated the term we now use to include memoir, literary journalism, the essay, and more, without actually using it. Madden is responsible for the shorthand “creative nonfiction.”

In an e-mail exchange with me, Madden remembers using that term and the phrase imaginative non-fiction interchangeably while at Ohio University, and says that he “continued to use those two terms when I moved to Louisiana State University and created the undergraduate [creative writing] program.” (LSU is my MFA alma mater, it turns out, so the personal connections, for whatever they are worth, continue to stack up oddly.)

Madden is sure that he invented the term, rather than appropriating it, and the trail ends there.

So now we have our answer—and our champion. Or scapegoat. Let the complaining resume.

- Utility Menu

English CWNM. Nonfiction Writing for Magazines

Instructor: Maggie Doherty TBD | Location: TBD Enrollment: Limited to 12 students

This course will focus on the genres of nonfiction writing commonly published in magazines: the feature, the profile, the personal essay, and longform arts criticism. We will read and discuss examples of such pieces from magazines large (Harper’s, The New Yorker) and small (n+1, The Drift); our examples will be drawn from the last several years. We will discuss both the process of writing such pieces—research, reporting, drafting, editing—and the techniques required to write informative, engaging, elegant nonfiction. In addition to short writing exercises performed in class and outside of class, each student will write one long piece in the genre of their choosing over the course of the semester, workshopping the piece twice, at different stages of completion. Although some attention will be paid to pitching and placing work in magazines, the focus of the course will be on the writing process itself.

English CNYA. Creative Nonfiction Workshop: Young Adult Writing

Instructor: Melissa Cundieff Thursday, 3:00-5:45pm | Location: TBD Enrollment: Limited to 12 students Course Site

In this workshop-based class, students will consider themes that intersect with the Young Adult genre: gender and sexuality, romantic and platonic relationships and love/heartbreak, family, divorce and parental relationships, disability, neurodivergence, drug use, the evolution/fracturing of childhood innocence, environmentalism, among others. Students will write true stories about their lived lives with these themes as well as intended audience (ages 12-18) specifically in mind. For visual artists, illustrating one’s work/essays is something that I invite but of course do not require. We will read work by Sarah Prager, Robin Ha, ND Stevenson, Laurie Hals Anderson, Dashka Slater, and Jason Reynolds. Apply via Submittable (deadline: 11:59pm EDT on Sunday, April 7) Supplemental Application Information: Applications for this class should include a 2-3 page (double-spaced if prose, single-spaced if poetry) creating writing sample of any genre (nonfiction, fiction, poetry), or combination of genres. Additionally, I ask that students submit a 250-word reflection on their particular relationship with creative writing and why this course appeals to them. This class is open to students of all writing levels and experience.

English CMMU. Creative Nonfiction Workshop: Using Music

Instructor: Melissa Cundieff Tuesday, 12:00-2:45pm | Location: TBD Enrollment: Limited to 12 students Course Site

In this workshop-based class, students will think deeply about how music is often at the center of their experiences, may it be as a song, an album, an artist, their own relationship with an instrument, etc. This class will entail writing true stories about one's life in which the personal and music orbit and/or entangle each other. This will include some journalism and criticism, but above all it will ask you to describe how and why music matters to your lived life. We will read work by Hayao Miyazaki, Jia Tolentino, Kaveh Akbar, Oliver Sacks, Susan Sontag, Adrian Matejka, among many others, (as well as invite and talk with guest speaker(s)). This class is open to all levels. Apply via Submittable (deadline: 11:59pm EDT on Sunday, April 7) Supplemental Application Information: Applications for this class should include a 2-3 page (double-spaced if prose, single-spaced if poetry) creating writing sample of any genre (nonfiction, fiction, poetry), or combination of genres. Additionally, I ask that students submit a 250-word reflection on their particular relationship with creative writing and why this course appeals to them. This class is open to students of all writing levels and experience.

English CIHR. Reading and Writing the Personal Essay: Workshop

Instructor: Michael Pollan Monday, 3:00-5:45 pm | Location: TBD Enrollment: Limited to 12 students Course Site

There are few literary forms quite as flexible as the personal essay. The word comes from the French verb essai, “to attempt,” hinting at the provisional or experimental mood of the genre. The conceit of the personal essay is that it captures the individual’s act of thinking on the fly, typically in response to a prompt or occasion. The form offers the rare freedom to combine any number of narrative tools, including memoir, reportage, history, political argument, anecdote, and reflection. In this writing workshop, we will read essays beginning with Montaigne, who more or less invented the form, and then on to a varied selection of his descendants, including George Orwell, E.B. White, James Baldwin, Susan Sontag, Joan Didion, David Foster Wallace and Rebecca Solnit. We will draft and revise essays of our own in a variety of lengths and types including one longer work of ambition. A central aim of the course will be to help you develop a voice on the page and learn how to deploy the first person—not merely for the purpose of self-expression but as a tool for telling a story, conducting an inquiry or pressing an argument.

Apply via Submittable (deadline: 11:59pm EDT on Sunday, April 7)

Supplemental Application Information: To apply, submit a brief sample of your writing in the first person along with a letter detailing your writing experience and reasons for wanting to take this course.

English CNFJ. Narrative Journalism

Instructor: Darcy Frey Fall 2024: Thursday, 3:00-5:45 pm | Location: TBD Enrollment: Limited to 12 students. Course Site Spring 2025: TBD

In this hands-on writing workshop, we will study the art of narrative journalism in many different forms: Profile writing, investigative reportage, magazine features. How can a work of journalism be fashioned to tell a captivating story? How can the writer of nonfiction narratives employ the scene-by-scene construction usually found in fiction? How can facts become the building blocks of literature? Students will work on several short assignments to practice the nuts-and-bolts of reporting, then write a longer magazine feature to be workshopped in class and revised at the end of the term. We will take instruction and inspiration from the published work of literary journalists such as Joan Didion, John McPhee, Adrian Nicole LeBlanc, and John Jeremiah Sullivan. This is a workshop-style class intended for undergraduate and graduate students at all levels of experience. No previous experience in English Department courses is required.

Apply via Submittable (deadline: 11:59pm ET on Sunday, April 7)

Supplemental Application Information: Please write a substantive letter of introduction describing who you are as writer at the moment and where you hope to take your writing; what experience you may have had with journalism or narrative nonfiction; what excites you about narrative journalism in particular; and what you consider to be your strengths and weaknesses as a writer. Additionally, please submit 3-5 pages of journalism or narrative nonfiction or, if you have not yet written much nonfiction, an equal number of pages of narrative fiction.

English CMFG. Past Selves and Future Ghosts

Instructor: Melissa Cundieff Spring 2024: Please login to the course catalog at my.harvard.edu for meetings times & location Enrollment: Limited to 12 students Course Site Spring 2025: TBD As memoirist and author Melissa Febos puts it: “The narrator is never you, and the sooner we can start thinking of ourselves on the page that way, the better for our work. That character on the page is just this shaving off of the person that was within a very particular context, intermingled with bits of perspective from all the time since — it’s a very specific little cocktail of pieces of the self and memory and art … it’s a very weird thing. And then it’s frozen in the pages.” With each essay and work of nonfiction we produce in this workshop-based class, the character we portray, the narrator we locate, is never stagnant, instead we are developing a persona, wrought from the experience of our vast selves and our vast experiences. To that end, in this course, you will use the tools and stylistic elements of creative nonfiction, namely fragmentation, narrative, scene, point of view, speculation, and research to remix and retell all aspects of your experience and selfhood in a multiplicity of ways. I will ask that you focus on a particular time period or connected events, and through the course of the semester, you will reimagine and reify these events using different modes and techniques as modeled in the published and various works we read. We will also read, in their entireties, Melissa Febos's Body Work: The Radical Work of Personal Narrative, as well as Hanif Abdurraqib’s They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us , which will aid our discussions and help us to better understand the difference between persona(s) and the many versions of self that inhabit us. Supplemental Application Information: Applications for this class should include a 2-3 page (double-spaced if prose, single-spaced if poetry) creating writing sample of any genre (nonfiction, fiction, poetry), or combination of genres. Additionally, I ask that students submit a 250-word reflection on their particular relationship with creative writing and why this course appeals to them. This class is open to students of all writing levels and experience.

English CMDR. Creative Nonfiction: Departure and Return: "Home" as Doorway to Difference and Identity

Instructor: Melissa Cundieff Please login to the course catalog at my.harvard.edu for meetings times & location Enrollment: Limited to 12 students Course Site

In this workshop-based class, students will be asked to investigate something that directly or indirectly connects everyone: what it means to leave a place, or one's home, or one's land, and to return to it, willingly or unwillingly. This idea is inherently open-ended because physical spaces are, of course, not our only means of departure and/or return-- but also our politics, our genders, our relationships with power, and our very bodies. Revolution, too, surrounds us, on both larger and private scales, as does looking back on what once was, what caused that initial departure. Students will approach "home" as both a literal place and a figurative mindscape. We will read essays by Barbara Ehrenreich, Ocean Vuong, Natasha Sajé, Elena Passarello, Hanif Abdurraqib, Alice Wong, and Eric L. Muller, among others. Supplemental Application Information: Applications for this class should include a 2-3 page (double-spaced if prose, single-spaced if poetry) creating writing sample of any genre (nonfiction, fiction, poetry), or combination of genres. Additionally, I ask that students submit a 250-word reflection on their particular relationship with creative writing and why this course appeals to them. This class is open to students of all writing levels and experience. Apply via Submittable (deadline: 11:59pm ET on Saturday, November 4)

English CGOT. The Other

Instructor: Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah Thursday, 12:00-2:45 pm | Location: TBD Enrollment: Limited to 12 students Course Site

In this class, we will consider how literary non-fiction articulates or imagines difference, disdain, conflict, and dislike. We will also discuss the more technical and stylistic elements present in strong non-fiction, like reflection, observation, retrospection, scene-setting, description, complexity, and strong characterization. As we read and write, we will put these theoretical concerns into practice and play by writing two or three profiles about people you do not like, a place you don’t care for, an idea you oppose, or an object whose value eludes you. Your writing might be about someone who haunts you without your permission or whatever else gets under your skin, but ideally, your subject makes you uncomfortable, troubles you, and confounds you. We will interrogate how writers earn their opinion. And while it might be strange to think of literature as often having political aims, it would be ignorant to imagine that it does not. Non-fiction forces us to extend our understanding of point of view not just to be how the story unfolds itself technically–immersive reporting, transparent eyeball, third person limited, or third person omniscient--but also to identify who is telling this story and why. Some examples of the writing that we will read are Guy Debord, Lucille Clifton, C.L.R. James, Pascale Casanova, W.G. Sebald, Jayne Cortez, AbouMaliq Simone, Greg Tate, Annie Ernaux, Edward Said, Mark Twain, Jacqueline Rose, Toni Morrison, Julia Kristeva, and Ryszard Kapuscinski. Supplemental Application Information: Please submit a brief letter explaining why you're interested to take this class. Apply via Submittable (deadline: 11:59pm ET on Saturday, November 4)

English CMCC. Covid, Grief, and Afterimage

Instructor: Melissa Cundieff Wednesday, 3:00-5:45 pm | Location: Barker 269 Enrollment: Limited to 12 students Course Site In this workshop-based course we will write about our personal lived experiences with loss and grief born from the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as how grief and grieving became a collective experience that is ongoing and persistent, like an afterimage or haunting. As part of our examination, we will consider intersections with other global, historical experiences and depictions of loss, including the murder of George Floyd and the AIDS epidemic. Readings will include essays by Leslie Jamison, Arundhati Roy, Susan Sontag, Eve Tuck and C. Ree, Matt Levin, and Alice Wong, among others. Apply via Submittable (deadline: 11:59pm EDT on Saturday, August 26) Supplemental Application Information: Applications for this class should include a 3-5 page (double-spaced if prose, single-spaced if poetry) creating writing sample of any genre (nonfiction, fiction, poetry), or combination of genres. Additionally, I ask that students submit a 250 word reflection on their particular relationship with creative writing and why this course appeals to them. This class is open to students of all writing levels and experience.

Instructor: Melissa Cundieff Wednesday, 12:00-2:45 pm | Location: Barker 316 Enrollment: Limited to 12 students Course Site As memoirist and author Melissa Febos puts it: “The narrator is never you, and the sooner we can start thinking of ourselves on the page that way, the better for our work. That character on the page is just this shaving off of the person that was within a very particular context, intermingled with bits of perspective from all the time since — it’s a very specific little cocktail of pieces of the self and memory and art … it’s a very weird thing. And then it’s frozen in the pages.” With each essay and work of nonfiction we produce in this workshop-based class, the character we portray, the narrator we locate, is never stagnant, instead we are developing a persona, wrought from the experience of our vast selves and our vast experiences. To that end, in this course, you will use the tools and stylistic elements of creative nonfiction, namely fragmentation, narrative, scene, point of view, speculation, and research to remix and retell all aspects of your experience and selfhood in a multiplicity of ways. I will ask that you focus on a particular time period or connected events, and through the course of the semester, you will reimagine and reify these events using different modes and techniques as modeled in the published and various works we read. We will also read, in their entireties, Melissa Febos's Body Work: The Radical Work of Personal Narrative, as well as Hanif Abdurraqib’s They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us , which will aid our discussions and help us to better understand the difference between persona(s) and the many versions of self that inhabit us. Apply via Submittable (deadline: 11:59pm EDT on Saturday, August 26) Supplemental Application Information: Applications for this class should include a 3-5 page (double-spaced if prose, single-spaced if poetry) creating writing sample of any genre (nonfiction, fiction, poetry), or combination of genres. Additionally, I ask that students submit a 250 word reflection on their particular relationship with creative writing and why this course appeals to them. This class is open to students of all writing levels and experience.

English CRGS. The Surrounds: Writing Interiority and Outsiderness

Instructor: Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah Thursday, 12:00-2:45 pm | Location: Lamont 401 Enrollment: Limited to 12 students Course Site

The essayist, the writer of non-fiction, has historically been an oracle of opinions that most often go unsaid. They do not traditionally reinforce a sense of insular collectivity, instead they often steer us towards a radical understanding of the moment that they write from. The best essayists unearth and organize messages from those most at the margins: the ignored, the exiled, the criminal, and the destitute. So, by writing about these people, the essayist is fated, most nobly or just as ignobly, to write about the ills and aftermaths of their nation’s worse actions. It is an obligation and also a very heavy burden.

In this class we will examine how the essay and many essayists have functioned as geographers of spaces that have long been forgotten. And we read a series of non-fiction pieces that trouble the question of interiority, belonging, the other, and outsiderness. And we will attempt to do a brief but comprehensive review of the essay as it functions as a barometer of the author’s times. This will be accomplished by reading the work of such writers as: Herodotus, William Hazlitt, Doris Lessing, Audre Lorde, Gay Talese, Binyavanga Wainaina, Jennifer Clement, V.S. Naipaul, Sei Shonagon, George Orwell, Ha Jin, Margo Jefferson, Simone White, and Joan Didion. This reading and discussion will inform our own writing practice as we write essays.

Everyone who is interested in this class should feel free to apply.

Supplemental Application Information: Please submit a brief letter explaining why you're interested to take this class. Apply via Submittable (deadline: 11:59pm EDT on Saturday, August 26)

English CNFD. Creative Nonfiction

Instructor: Maggie Doherty Tuesday, 12:00-2:45 pm | Location: Sever 205 Enrollment: Limited to 12 students Course Site This course is an overview of the creative nonfiction genre and the many different types of writing that are included within it: memoir, criticism, nature writing, travel writing, and more. Our readings will be both historical and contemporary: writers will include Virginia Woolf, James Baldwin, Joan Didion, Audre Lorde, Hilton Als, and Carmen Maria Machado. During the first half of the semester, we will read two pieces closely; we will use our class discussions to analyze how these writers use pacing, character, voice, tone, and structure to tell their stories. Students will complete short, informal writing assignments during this part of the semester, based on the genre of work we’re discussing that week. During the second half of the semester, each student will draft and workshop a longer piece of creative nonfiction in the genre(s) of their choosing, which they will revise by the end of the semester. Students will be expected to provide detailed feedback on the work of their peers. This course is open to writers at all levels; no previous experience in creative writing is required. Apply via Submittable (deadline: 11:59pm EDT on Saturday, August 26) Supplemental Application Information: Please write a letter of introduction (1-2 pages) giving a sense of who you are, your writing experience, and your current goals for your writing. You may also include writers or nonfiction works that you admire, as well as any themes or genres you'd like to experiment with in the course. Please also include a 3-5-page writing sample, ideally of some kind of creative writing (nonfiction is preferred, but fiction would also be acceptable). If you don't have a creative sample, you may submit a sample of your academic writing.

English CACD. The Art of Criticism

Instructor: Maggie Doherty Wednesday, 12:00-2:45pm | Location: TBD Enrollment: Limited to 12 students Course Site

This course will consider critical writing about art–literary, visual, cinematic, musical, etc.—as an art in its own right. We will read and discuss criticism from a wide variety of publications, paying attention to the ways outlets and audience shape critical work. The majority of our readings will be from the last few years and will include pieces by Joan Acocella, Andrea Long Chu, Jason Farago, and Carina del Valle Schorske. Students will write several short writing assignments (500-1000 words), including a straight review, during the first half of the semester and share them with peers. During the second half of the semester, each student will write and workshop a longer piece of criticism about a work of art or an artist of their choosing. Students will be expected to read and provide detailed feedback on the work of their peers. Students will revise their longer pieces based on workshop feedback and submit them for the final assignment of the class. Apply via Submittable (deadline: 11:59pm EDT on Sunday, April 7) Supplemental Application Information: Please write a letter of introduction (1-2 pages) giving a sense of who you are, your writing experience, and your current goals for your writing. Please also describe your relationship to the art forms and/or genres you're interested in engaging in the course. You may also list any writers or publications whose criticism you enjoy reading. Please also include a 3-5-page writing sample of any kind of prose writing. This could be an academic paper or it could be creative fiction or nonfiction.

English CNFR. Creative Nonfiction: Workshop

Instructor: Darcy Frey Fall 2024: Wednesday, 3:00-5:45 pm | Location: TBD Enrollment: Limited to 12 students. Course Site Spring 2025: TBD

Whether it takes the form of literary journalism, essay, memoir, or environmental writing, creative nonfiction is a powerful genre that allows writers to break free from the constraints commonly associated with nonfiction prose and reach for the breadth of thought and feeling usually accomplished only in fiction: the narration of a vivid story, the probing of a complex character, the argument of an idea, or the evocation of a place. Students will work on several short assignments to hone their mastery of the craft, then write a longer piece that will be workshopped in class and revised at the end of the term. We will take instruction and inspiration from published authors such as Joan Didion, James Baldwin, Ariel Levy, Alexander Chee, and Virginia Woolf. This is a workshop-style class intended for undergraduate and graduate students at all levels of experience. No previous experience in English Department courses is required. Apply via Submittable (deadline: 11:59pm ET on Sunday, April 7)

Supplemental Application Information: Please write a substantive letter of introduction describing who you are as writer at the moment and where you hope to take your writing; what experience you may have had with creative/literary nonfiction; what excites you about nonfiction in particular; and what you consider to be your strengths and weaknesses as a writer. Additionally, please submit 3-5 pages of creative/literary nonfiction (essay, memoir, narrative journalism, etc, but NOT academic writing) or, if you have not yet written much nonfiction, an equal number of pages of narrative fiction.

English CLPG. Art of Sportswriting

Instructor: Louisa Thomas Spring 2024: Tuesday, 9:00-11:45am | Location: TBD Enrollment: Limited to 12 students Course Site Spring 2025: TBD

In newsrooms, the sports section is sometimes referred to as the “toy department” -- frivolous and unserious, unlike the stuff of politics, business, and war. In this course, we will take the toys seriously. After all, for millions of people, sports and other so-called trivial pursuits (video games, chess, children’s games, and so on) are a source of endless fascination. For us, they will be a source of stories about human achievements and frustrations. These stories can involve economic, social, and political issues. They can draw upon history, statistics, psychology, and philosophy. They can be reported or ruminative, formally experimental or straightforward, richly descriptive or tense and spare. They can be fun. Over the course of the semester, students will read and discuss exemplary profiles, essays, articles, and blog posts, while also writing and discussing their own. While much (but not all) of the reading will come from the world of sports, no interest in or knowledge about sports is required; our focus will be on writing for a broad audience. Supplemental Application Information: To apply, please write a letter describing why you want to take the course and what you hope to get out of it. Include a few examples of websites or magazines you like to read, and tell me briefly about one pursuit -- football, chess, basketball, ballet, Othello, crosswords, soccer, whatever -- that interests you and why.

- Fiction (21)

- Nonfiction (17)

- Playwriting (4)

- Poetry (27)

- Screenwriting (5)

Quiz 2: Punctuation and the Formal Essay – Flashcards

Unlock all answers in this set

Haven't found what you were looking for, search for samples, answers to your questions and flashcards.

- Enter your topic/question

- Receive an explanation

- Ask one question at a time

- Enter a specific assignment topic

- Aim at least 500 characters

- a topic sentence that states the main or controlling idea

- supporting sentences to explain and develop the point you’re making

- evidence from your reading or an example from the subject area that supports your point

- analysis of the implication/significance/impact of the evidence finished off with a critical conclusion you have drawn from the evidence.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Beyond the True-False Binary: How the Internet Helped Transform the Lyric Essay

Hugh ryan on truth and post-truth in creative nonfiction.

Twenty five years ago, the vast majority of my reading was both bounded and continuous—bounded, because most of my reading material came in discrete packets (a book; a magazine; the salacious graffiti of a seedy bathroom stall), and continuous, because although I might put a book down and come back to it, or have several books going at the same time, I was not generally bouncing back and forth between unrelated reading experiences simultaneously.

Today, I’ve already checked Twitter seven times while writing the sentence above, and now my brain is a whizzing fizz of climate change, K-pop, and “hot” takes in three languages and a hundred voices.

Over the course of the last generation, the Internet has changed our common reading experience; now, as a teacher of creative nonfiction at the Bennington Writing Seminars, I’m seeing first-hand how this new world of reading has transformed the instinctual writing voices of my students. An epochal shift is occurring, and from our great humming mass of distributed machines my students are summoning an unexpected ghost: lyricism.

The lyric essay is having a moment—despite the fact that many of these students could not offer a definition of the lyric essay, describe its techniques, or explain why they used them. But this is to be expected, as this change is not the precious reaching of a precocious undergrad, but an upstream change in the base reagents my students are combining in the alchemical process that is writing. To understand why this is happening, and how to take advantage of it, we need to first step back and define the lyric’s place in the ecosystem of essays. And to really do that , we first have to define what essays themselves are made of.

The Three Components of Essays

All essays have three fundamental components: self, content, and form. The self is the point-of-view of the piece, the storyteller; the selective intelligence of the author, which both chooses the moments that make up the piece and imbues each moment with the unique perspective that best serves the piece’s totality. The content is the thing we are writing about; what Vivian Gornick so masterfully defines as “the situation” (the plot or external object under consideration) and “the story” (the meaning, or internal realizations of the narrator). Finally, form is the shape of the words on the page, how they connect, spiral, or explode.

Think about it this way: all essays are journeys to new knowledge or states of being. The self is the shoulder we the reader are perched on for the journey. The content is the landscape we are traveling through and the path we are on (in Gornick’s terms, the moment-to-moment stuff we see is “the situation,” and our later reflective understanding of the path we took is “the story”). The form is our mode of locomotion, whether we are walking slowly and methodically from start to finish, or leaping wildly from beginning to end and back again.

The Three Kinds of Essays

Building off of this: there are also three main kinds of essay: personal , research , and lyric . All three have self , content , and form , but each kind has a corresponding component that is of dominant importance.

Personal essays are distinguished by their focus on self. The unique point of view of the storyteller is the fundamental reason to read the essay. The content is mostly there to provide a space for the author to think or have experiences, and the reader isn’t meant to learn that content.

Research essays are distinguished by their focus on content. Like journalism, they prize explaining something to the reader; but unlike journalism, the author is directly implicated—they are a part of the group, idea, or experience being explained, and through that explanation, the reader comes to understand the author better, as well as the content.

Finally, lyric essays are distinguished by their focus on form. In these essays, fundamental aspects of meaning are contained in or created by their shape on the page. For example, in lyric essays white space, fragments, repetition, juxtaposition, caesura, braids, changes in tense, and non-linear-organizing structures are frequently used to suggest or change the relationship between the written words and their meaning.

A Rabbit Hole Into the Concept of Truth

The divisions above aren’t arbitrary; they are indicative of a deeper reality about essays. The concept behind creative nonfiction is easy—tell the truth—but the truth, it turns out, is subjective. The three kinds of essay (personal, research, and lyric) are defined as much by their relationship to the truth as they are by how they are written; or perhaps it is more accurate to say that the way they are written is a sotto voce attempt to communicate the author’s understanding of “the truth” as a concept.

How does this work? Well, we can divide all statements into three truth values: true, false, or outside the true-false binary (neither true nor false, both true and false, shifting between true and false, not categorizable as true or false, etc.). In writing, we call these relationships to the truth nonfiction, fiction, and poetry. The different kinds of essays draw both their narrative power and their literary techniques from these pre-existing genres.

Personal essays fall closest to fiction; they are primarily about illustrating the unique point of view of the author. They smooth out the randomness of life to turn it into narrative. The truth exists in the meaning, not the details.

Because the goal of the personal essay is to get the reader to see a certain perspective, they often play fast and loose with the truth (on a small scale). For instance, almost every great personal essayist says that the details are necessary, but they don’t matter. So long as the overall intention is not to deceive the reader, invented detail—in this way of writing—is seen as helping the reader to get at the truth of it all. For example, here’s essayist Jo Ann Beard discussing truth in her book Boys of My Youth :

I remembered the bare bones, and then the rest of it is just constructed from what I know of the people involved. Fuzzy memory doesn’t usually work in an essay; you have to be detailed…the dialogue and various other things were constructed for the pleasure of the reader. And, I must add, the writer… I don’t think anybody could read [BOYS OF MY YOUTH] and think they were reading a factual account of someone’s childhood.

Research essays , on the other hand, double down on nonfiction; they are primarily about explaining some external reality or experience the author has had. The truth in these essays exists in the facts.

Research essays are thus detail oriented. They use a lot of proper names and dates and quotes, and the author can’t make things up without losing my trust as a reader. Atul Gawande, a surgeon turned essayist, is a strong advocate for this kind of truth in nonfiction. In The Guardian in 2014 , an interviewer noted that Gawande felt the “idea of precision” is something writers could learn from doctors. “As a doctor,” he said, “you have to notice the particular shade of blue the patient turns. You need to be very factual.”

Here we have the difference between research and personal essays: Gawande says we have to be very factual, Beard says no one would ever assume her work was factual. (For my money, the best craft essay on this topic is T Kira Madden’s “Against Catharsis: Writing is Not Therapy.”)

Finally, Lyric essays work the techniques of poetry, the area of writing where we rarely ask if something is true or not. Thus, they forefront the idea that truth is in some fundamental way uncertain, unknowable, or uncommunicable, and that life is not at all like a story: it is confusing, conflicting, discontinuous, random, and with multiple or unclear meanings.

Lyric essays tend to be quite subtle, occluded, and difficult, because they often abandon the conventions of normal prose writing. Lyric essays have to teach readers how to understand the rules by which they function, and that can be hard.

In an interview with the journal Sierra Nevada in 2017 , lyric essayist Matthew Komatsu discussed his approach to using lyric juxtapositions to move outside the true-false binary. “[You have] two different ways of viewing it, and I think when you put those two next to each other, if you do it right, there can be a very poetic aspect…where you can essentially represent the different viewpoints, neither being more valid than the other.”

We can see this technique play out in Komatsu’s tender meditation “When We Played.” Originally published in the journal Brevity , it compares his experiences as a kid playing soldier, with his experiences as an adult in the military in Afghanistan. But Komatsu makes this comparison via form, not the written word, and by leaving it thus unspoken, he makes it impossible to analyze in terms of its “truth.”

“When We Played” is composed of short numbered sections. Odd sections are italicized, even ones aren’t. This suggests to the reader some kind of harmony, or braid, that unites all the odd sections and all the even ones. Here is a short excerpt from the beginning:

1. When we played war as boys, we never died. Dead was a reset button, a do-over, a quarrel over who killed who. Maybe we played fair…

2. All those close calls. That time in Afghanistan the SUV drove past the white rocks and into the red ones—white all right, red is dead—a local in the backseat jabbering jib. What did he say? Translator: “He say, WE ARE DRIVING INTO MINEFIELD.”

3. When we played war as men, the wounded on their backs—they called our names, their mothers’ names, the names of all gods past and present…

Komatsu’s form leads us to expect that section three will be a segment about him as a child. When instead we have another adult section, paralleling the sentence structure of section 1, the unexpected juxtaposition suggests an equivalency between the boys and the men—an ineffable comparison built via placement and font. And this brings us back around to the Internet.

The Poetry of Tabs

In many ways, writing on the Internet (not for publication, just regular daily communication) has quietly routinized us to lyric techniques. Lyric essays are often identifiable at a glance, in the same way poetry can be distinguished from prose. Like Komatsu’s essay above, these pieces often move in small segments and employ white space, placement, and font to express ideas. They might repeat a word or phrase to explore multiple meanings from it; or place images, ideas, or phrases next to each other to suggest meaning without putting it into words; or break traditional grammar and sentence structure; or change POV suddenly; or abandon chronological time in favor of some other organizing principle (often alphabetical); or dive back and forth between seemingly unconnected threads; or speak in many voices simultaneously.

Where else do all of these things happen? On Twitter. In the comment section. In discord chats and news aggregators and blogs and the million other online spaces that now make up the vast majority of the quotidian, functional nonfiction we read every day.

But these techniques aren’t just more common because of the Internet, they’re also more useful, because the Internet has pushed us firmly into a post truth world. Deep-fake videos, endless stories of online grifters, and the anonymity of the Internet have tricked or will trick all of us at some point. Moreover: just the constant and routine exposure to other points of view, different stories, and critique from unexpected angles have led us to be suspicious of the Truth (capital T) and our ability to reach it or tell it overall. How does nonfiction function in the hands of writers who aren’t sure the truth exists? Lyrically.

When employed in creative nonfiction (like essay writing), lyric techniques literally complicate the ability of the reader to find truth in the written word: they leave things unsaid and therefore undefinable; they draw multiple, sometimes conflicting, meanings from one word or phrase; they break down sentence structure, embracing verb and tense confusion; they take the story out of linear time, which destroys an easy understanding of causality and motivation, etc.

Thus, the Internet has spent decades teaching my students to read lyric forms, and simultaneously, doubt the truth. It has created (or made visible) a problem—the unknowability of truth—and at the same time, sculpted a language to talk about it. This is not a process that will stop or reverse tomorrow, and I suspect that I will continue to see more lyric techniques in the essays of my students, peers, and friends in years to come. As a writing teacher, I don’t see it as my job to push my students towards one form of truth over another, but it is essential that I understand how the techniques they are using communicate the truth, and why they are reaching for these techniques, right now, instead of more traditional ones.

Previous Article

Next article.

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS