Sport Psychology and Performance Psychology: Contributions to the Mental Health of Athletes

- First Online: 31 May 2020

Cite this chapter

- David B. Coppel 3

2024 Accesses

1 Citations

Sport psychology and performance psychology are related and overlapping terms that encompass a broad range of interventions, applications, and areas of research. These two domains focus on the psychological aspects of performance, within sports or exercise contexts in the former, as well as expansion to non-sport areas of performance such as business, the performing arts, medicine, and the military, in the latter. Some have proposed that sport psychology is a subspecialty of performance psychology, which is seen as an umbrella term. Over a number of decades, high-performance strategies and techniques and skills, developed within sports and exercise psychology field, have been extrapolated and applied to non-sports areas with positive results. Most individuals want to perform well in life, whether it is functioning optimally at work or school or performing well within family roles or performing and/or adapting well to situations and life circumstances; thus, the work of sport and performance psychology practitioners and researchers is to understand the often complex relationships of psychological (and/or biopsychosocial) factors involved in creating positive performance outcomes and experiences. Sport psychologists and performance psychologists play important roles within sports medicine and are often the best-trained providers to deal with mental health issues in athletes. Over the years, sport psychology has expanded to be seen as “sport and exercise psychology,” to include the contributions of exercise and sport scientists to sport performance (beyond applied sport psychologists); the field continues to expand and goes beyond sports to general performance science, which focuses on areas such as the development of expertise or the cognitive neuroscience aspects of high performance. For sports medicine providers, the perceived dichotomy of clinically or counseling-trained sport psychology providers and performance enhancement consultants (with various titles) can be confusing, especially as it relates to the mental health of athletes. Clinically trained sport psychologists can provide assessment and interventions that can address diagnosable mental health disorders and the subclinical disorder symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and sleep difficulties. As a member of the sports medicine team, sport psychologists are typically the most experienced providers to deal with the psychological and emotional aspects of an athlete’s sports injury and injury recovery or rehab experience.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Mental toughness in sport

Effects of psychological and psychosocial interventions on sport performance: a meta-analysis.

Measuring Well-Being in Sport Performers: Where are We Now and How do we Progress?

Weinberg R, Gould D. Foundations of sport and exercise psychology. 4th ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2007.

Google Scholar

Weinberg R, Gould D. Foundations of sport and exercise psychology. 6th ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2015.

Van Raalte J, Brewer B. Exploring sport and exercise psychology. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2014.

Papaioannou AG, Hackfort D, editors. Routledge companion to sport and exercise psychology: global perspectives and fundamental concepts. London and New York: Routledge/Taylor and Frances Group; 2015.

Murphy S. Sport psychology interventions. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1995.

Barker JB, Neil R, Fletcher D. Using sport and performance psychology in the management of change. J Chang Manag. 2016;16(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2016.1137149 .

Article Google Scholar

Kornspan A. History of sports performance. In: Murphy S, editor. The Oxford handbook of sport and performance psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. 3–23.

Portenga S, Aoyagi M, Cohen A. Helping to build a profession: a working definition of sport and performance psychology. J Sport Psychol Action. 2017;8(1):47–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2016.1227413 .

Tod D, Hutter R, Eubank M. Professional development for sport psychology practice. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;16:133–7.

Triplett N. The dynamogenic factors in pacemaking and competition. Am J Psychol. 1898;9:507–33.

Straub W, Williams J, editors. Cognitive sport psychology. Lansing, NY: Sports Sciences Associates; 1984.

May J, Asken M, editors. Sport psychology: the psychological health of the athlete. New York: PMA Publishing; 1987.

Vealey R. Conceptualization of sport-confidence and competitive orientation: preliminary investigation and instrument development. J Sport Psychol. 1986;8:221–46.

Feltz D, Short S, Sullivan. Self-efficacy in sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2008.

Hackfort D, Schwenkmezger P. Anxiety. In: Singer R, Murphey M, Tennant L, editors. Handbook of research in sport psychology. New York: Macmillan; 1993.

Hays K, editor. Performance psychology in action. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009.

Razon S, Tenenbaum G. Measurement in sport and exercise psychology. In: Van Raalte J, Brewer B, editors. Exploring sport and exercise psychology. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2014. p. 279–310.

Gardner F, Moore Z. Clinical sport psychology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2006.

Book Google Scholar

Moran A. The psychology of concentration in sport performers: a cognitive analysis. East Sussex: Psychology Press; 1996.

Beliock S. Beyond the playing field: sport psychology meets embodied cognition. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2008;I(1):19–30.

Zaichowsky L. Psychophysiology and neuroscience in sport: introduction to the special issue. J Clin Sport Psychol. 2012;6(1):1–5.

Furley P, Wood G. Working memory, attentional control, and expertise in sports: a review of current literature and directions for future research. J Appl Res Mem Cogn. 2016;5(4):415–25.

Cotterill S. Preparing for performance: strategies adopted across performance domains. Sports Psychol. 2015;29:158–70.

DeWiggins S, Hite B, Alston V. Personal performance plan: application of mental skills training to real-world military tasks. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2010;22(4):458–73.

Causer J, Vickers J, Snelgrove R, Arsenault G, Harvey A. Quiet eye training improves surgical knot-tying performance. Surgery. 2014;156(5):1089–96.

Cocks M, Moulton C, Luu S, Cil T. What surgeons can learn from athletes: mental practice in sports and surgery. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(2):262–9.

Rao A, Tait J, Alijani A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the role of mental training in the acquisition of technical skills in surgery. Am J Surg. 2015;210(3):545–53.

Coppel D. Psychological aspects of sports medicine. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep. 2015;3(1):36–42.

Coppel D. The role of sport psychology and psychiatry. In: Madden C, Putukian M, McCarty E, Young C, editors. Netter’s sports medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Publishing; 2018. p. 173–9.

Herring SA, Kibler WB, Putukian M, Coppel D, et al. Psychological issues related to illness and injury in athletes and the team physician: a consensus statement (2016 update). Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2017;49:1043.

Gill D. Psychological dynamics of sport and exercise. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2000.

Aoyagi M, Portenga S. The role of positive ethics and virtues in the context of sport and performance psychology service delivery. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2010;41(3):253–9.

Herzog T, Hays K. Therapist or mental skills coach? How to decide. Sport Psychol. 2012;26:486–99.

Meyers A, Whelan J, Murphy S. Cognitive behavioral strategies in athletic performance enhancement. Prog behav modif. 1995;30:137–64.

McCann S. At the Olympics, everything is a performance issue. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2008;6(3):267–76.

Moore Z, Bonagura K. Current opinion in clinical sport psychology: from athletic performance to psychological well-being. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;16:176–9.

Hays K. The psychology of performance in sport and other domains. In: The Oxford handbook of sport and performance psychology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. 24–45.

Ford J, Ildefanso K, Jones M, Arvinen-Barrow M. Sport-related anxiety: current insights. Open Access J Sports Med. 2017;8:205–12.

Sullivan J, Coppel D, Maniar S, Minniti A. Sport psychologists. In: Sternberg R, editor. Career paths in psychology. 3rd ed; 2017. p. 273–89.

Murphy S. The sport psych handbook. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2005.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

David B. Coppel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to David B. Coppel .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Family Medicine and Department of Orthopaedics, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA

Eugene Hong

Department of Family Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Ashwin L. Rao

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Coppel, D.B. (2020). Sport Psychology and Performance Psychology: Contributions to the Mental Health of Athletes. In: Hong, E., Rao, A. (eds) Mental Health in the Athlete. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44754-0_21

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44754-0_21

Published : 31 May 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-44753-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-44754-0

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Sport psychology and performance meta-analyses: A systematic review of the literature

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Department of Kinesiology and Sport Management, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, United States of America, Education Academy, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania

Roles Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft

Affiliation Department of Psychological Sciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Methodology

Roles Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Kinesiology and Sport Management, Honors College, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Faculty of Education, Health and Well-Being, University of Wolverhampton, Walsall, West Midlands, United Kingdom

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Division of Research & Innovation, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Queensland, Australia

- Marc Lochbaum,

- Elisabeth Stoner,

- Tristen Hefner,

- Sydney Cooper,

- Andrew M. Lane,

- Peter C. Terry

- Published: February 16, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Sport psychology as an academic pursuit is nearly two centuries old. An enduring goal since inception has been to understand how psychological techniques can improve athletic performance. Although much evidence exists in the form of meta-analytic reviews related to sport psychology and performance, a systematic review of these meta-analyses is absent from the literature. We aimed to synthesize the extant literature to gain insights into the overall impact of sport psychology on athletic performance. Guided by the PRISMA statement for systematic reviews, we reviewed relevant articles identified via the EBSCOhost interface. Thirty meta-analyses published between 1983 and 2021 met the inclusion criteria, covering 16 distinct sport psychology constructs. Overall, sport psychology interventions/variables hypothesized to enhance performance (e.g., cohesion, confidence, mindfulness) were shown to have a moderate beneficial effect ( d = 0.51), whereas variables hypothesized to be detrimental to performance (e.g., cognitive anxiety, depression, ego climate) had a small negative effect ( d = -0.21). The quality rating of meta-analyses did not significantly moderate the magnitude of observed effects, nor did the research design (i.e., intervention vs. correlation) of the primary studies included in the meta-analyses. Our review strengthens the evidence base for sport psychology techniques and may be of great practical value to practitioners. We provide recommendations for future research in the area.

Citation: Lochbaum M, Stoner E, Hefner T, Cooper S, Lane AM, Terry PC (2022) Sport psychology and performance meta-analyses: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE 17(2): e0263408. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408

Editor: Claudio Imperatori, European University of Rome, ITALY

Received: September 28, 2021; Accepted: January 18, 2022; Published: February 16, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Lochbaum et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Sport performance matters. Verifying its global importance requires no more than opening a newspaper to the sports section, browsing the internet, looking at social media outlets, or scanning abundant sources of sport information. Sport psychology is an important avenue through which to better understand and improve sport performance. To date, a systematic review of published sport psychology and performance meta-analyses is absent from the literature. Given the undeniable importance of sport, the history of sport psychology in academics since 1830, and the global rise of sport psychology journals and organizations, a comprehensive systematic review of the meta-analytic literature seems overdue. Thus, we aimed to consolidate the existing literature and provide recommendations for future research.

The development of sport psychology

The history of sport psychology dates back nearly 200 years. Terry [ 1 ] cites Carl Friedrich Koch’s (1830) publication titled [in translation] Calisthenics from the Viewpoint of Dietetics and Psychology [ 2 ] as perhaps the earliest publication in the field, and multiple commentators have noted that sport psychology experiments occurred in the world’s first psychology laboratory, established by Wilhelm Wundt at the University of Leipzig in 1879 [ 1 , 3 ]. Konrad Rieger’s research on hypnosis and muscular endurance, published in 1884 [ 4 ] and Angelo Mosso’s investigations of the effects of mental fatigue on physical performance, published in 1891 [ 5 ] were other early landmarks in the development of applied sport psychology research. Following the efforts of Koch, Wundt, Rieger, and Mosso, sport psychology works appeared with increasing regularity, including Philippe Tissié’s publications in 1894 [ 6 , 7 ] on psychology and physical training, and Pierre de Coubertin’s first use of the term sport psychology in his La Psychologie du Sport paper in 1900 [ 8 ]. In short, the history of sport psychology and performance research began as early as 1830 and picked up pace in the latter part of the 19 th century. Early pioneers, who helped shape sport psychology include Wundt, recognized as the “father of experimental psychology”, Tissié, the founder of French physical education and Legion of Honor awardee in 1932, and de Coubertin who became the father of the modern Olympic movement and founder of the International Olympic Committee.

Sport psychology flourished in the early 20 th century [see 1, 3 for extensive historic details]. For instance, independent laboratories emerged in Berlin, Germany, established by Carl Diem in 1920; in St. Petersburg and Moscow, Russia, established respectively by Avksenty Puni and Piotr Roudik in 1925; and in Champaign, Illinois USA, established by Coleman Griffith, also in 1925. The period from 1950–1980 saw rapid strides in sport psychology, with Franklin Henry establishing this field of study as independent of physical education in the landscape of American and eventually global sport science and kinesiology graduate programs [ 1 ]. In addition, of great importance in the 1960s, three international sport psychology organizations were established: namely, the International Society for Sport Psychology (1965), the North American Society for the Psychology of Sport and Physical Activity (1966), and the European Federation of Sport Psychology (1969). Since that time, the Association of Applied Sport Psychology (1986), the South American Society for Sport Psychology (1986), and the Asian-South Pacific Association of Sport Psychology (1989) have also been established.

The global growth in academic sport psychology has seen a large number of specialist publications launched, including the following journals: International Journal of Sport Psychology (1970), Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology (1979), The Sport Psychologist (1987), Journal of Applied Sport Psychology (1989), Psychology of Sport and Exercise (2000), International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology (2003), Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology (2007), International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology (2008), Journal of Sport Psychology in Action (2010), Sport , Exercise , and Performance Psychology (2014), and the Asian Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology (2021).

In turn, the growth in journal outlets has seen sport psychology publications burgeon. Indicative of the scale of the contemporary literature on sport psychology, searches completed in May 2021 within the Web of Science Core Collection, identified 1,415 publications on goal setting and sport since 1985; 5,303 publications on confidence and sport since 1961; and 3,421 publications on anxiety and sport since 1980. In addition to academic journals, several comprehensive edited textbooks have been produced detailing sport psychology developments across the world, such as Hanrahan and Andersen’s (2010) Handbook of Applied Sport Psychology [ 9 ], Schinke, McGannon, and Smith’s (2016) International Handbook of Sport Psychology [ 10 ], and Bertollo, Filho, and Terry’s (2021) Advancements in Mental Skills Training [ 11 ] to name just a few. In short, sport psychology is global in both academic study and professional practice.

Meta-analysis in sport psychology

Several meta-analysis guides, computer programs, and sport psychology domain-specific primers have been popularized in the social sciences [ 12 , 13 ]. Sport psychology academics have conducted quantitative reviews on much studied constructs since the 1980s, with the first two appearing in 1983 in the form of Feltz and Landers’ meta-analysis on mental practice [ 14 ], which included 98 articles dating from 1934, and Bond and Titus’ cross-disciplinary meta-analysis on social facilitation [ 15 ], which summarized 241 studies including Triplett’s (1898) often-cited study of social facilitation in cycling [ 16 ]. Although much meta-analytic evidence exists for various constructs in sport and exercise psychology [ 12 ] including several related to performance [ 17 ], the evidence is inconsistent. For example, two meta-analyses, both ostensibly summarizing evidence of the benefits to performance of task cohesion [ 18 , 19 ], produced very different mean effects ( d = .24 vs d = 1.00) indicating that the true benefit lies somewhere in a wide range from small to large. Thus, the lack of a reliable evidence base for the use of sport psychology techniques represents a significant gap in the knowledge base for practitioners and researchers alike. A comprehensive systematic review of all published meta-analyses in the field of sport psychology has yet to be published.

Purpose and aim

We consider this review to be both necessary and long overdue for the following reasons: (a) the extensive history of sport psychology and performance research; (b) the prior publication of many meta-analyses summarizing various aspects of sport psychology research in a piecemeal fashion [ 12 , 17 ] but not its totality; and (c) the importance of better understanding and hopefully improving sport performance via the use of interventions based on solid evidence of their efficacy. Hence, we aimed to collate and evaluate this literature in a systematic way to gain improved understanding of the impact of sport psychology variables on sport performance by construct, research design, and meta-analysis quality, to enhance practical knowledge of sport psychology techniques and identify future lines of research inquiry. By systematically reviewing all identifiable meta-analytic reviews linking sport psychology techniques with sport performance, we aimed to evaluate the strength of the evidence base underpinning sport psychology interventions.

Materials and methods

This systematic review of meta-analyses followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 20 ]. We did not register our systematic review protocol in a database. However, we specified our search strategy, inclusion criteria, data extraction, and data analyses in advance of writing our manuscript. All details of our work are available from the lead author. Concerning ethics, this systematic review received a waiver from Texas Tech University Human Subject Review Board as it concerned archival data (i.e., published meta-analyses).

Eligibility criteria

Published meta-analyses were retained for extensive examination if they met the following inclusion criteria: (a) included meta-analytic data such as mean group, between or within-group differences or correlates; (b) published prior to January 31, 2021; (c) published in a peer-reviewed journal; (d) investigated a recognized sport psychology construct; and (e) meta-analyzed data concerned with sport performance. There was no language of publication restriction. To align with our systematic review objectives, we gave much consideration to study participants and performance outcomes. Across multiple checks, all authors confirmed study eligibility. Three authors (ML, AL, and PT) completed the final inclusion assessments.

Information sources

Authors searched electronic databases, personal meta-analysis history, and checked with personal research contacts. Electronic database searches occurred in EBSCOhost with the following individual databases selected: APA PsycINFO, ERIC, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, and SPORTDiscus. An initial search concluded October 1, 2020. ML, AL, and PT rechecked the identified studies during the February–March, 2021 period, which resulted in the identification of two additional meta-analyses [ 21 , 22 ].

Search protocol

ML and ES initially conducted independent database searches. For the first search, ML used the following search terms: sport psychology with meta-analysis or quantitative review and sport and performance or sport* performance. For the second search, ES utilized a sport psychology textbook and used the chapter title terms (e.g., goal setting). In EBSCOhost, both searches used the advanced search option that provided three separate boxes for search terms such as box 1 (sport psychology), box 2 (meta-analysis), and box 3 (performance). Specific details of our search strategy were:

Search by ML:

- sport psychology, meta-analysis, sport and performance

- sport psychology, meta-analysis or quantitative review, sport* performance

- sport psychology, quantitative review, sport and performance

- sport psychology, quantitative review, sport* performance

Search by ES:

- mental practice or mental imagery or mental rehearsal and sports performance and meta-analysis

- goal setting and sports performance and meta-analysis

- anxiety and stress and sports performance and meta-analysis

- competition and sports performance and meta-analysis

- diversity and sports performance and meta-analysis

- cohesion and sports performance and meta-analysis

- imagery and sports performance and meta-analysis

- self-confidence and sports performance and meta-analysis

- concentration and sports performance and meta-analysis

- athletic injuries and sports performance and meta-analysis

- overtraining and sports performance and meta-analysis

- children and sports performance and meta-analysis

The following specific search of the EBSCOhost with SPORTDiscus, APA PsycINFO, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, and ERIC databases, returned six results from 2002–2020, of which three were included [ 18 , 19 , 23 ] and three were excluded because they were not meta-analyses.

- Box 1 cohesion

- Box 2 sports performance

- Box 3 meta-analysis

Study selection

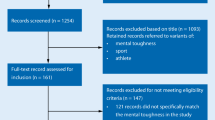

As detailed in the PRISMA flow chart ( Fig 1 ) and the specified inclusion criteria, a thorough study selection process was used. As mentioned in the search protocol, two authors (ML and ES) engaged independently with two separate searches and then worked together to verify the selected studies. Next, AL and PT examined the selected study list for accuracy. ML, AL, and PT, whilst rating the quality of included meta-analyses, also re-examined all selected studies to verify that each met the predetermined study inclusion criteria. Throughout the study selection process, disagreements were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408.g001

Data extraction process

Initially, ML, TH, and ES extracted data items 1, 2, 3 and 8 (see Data items). Subsequently, ML, AL, and PT extracted the remaining data (items 4–7, 9, 10). Checks occurred during the extraction process for potential discrepancies (e.g., checking the number of primary studies in a meta-analysis). It was unnecessary to contact any meta-analysis authors for missing information or clarification during the data extraction process because all studies reported the required information. Across the search for meta-analyses, all identified studies were reported in English. Thus, no translation software or searching out a native speaker occurred. All data extraction forms (e.g., data items and individual meta-analysis quality) are available from the first author.

To help address our main aim, we extracted the following information from each meta-analysis: (1) author(s); (2) publication year; (3) construct(s); (4) intervention based meta-analysis (yes, no, mix); (5) performance outcome(s) description; (6) number of studies for the performance outcomes; (7) participant description; (8) main findings; (9) bias correction method/results; and (10) author(s) stated conclusions. For all information sought, we coded missing information as not reported.

Individual meta-analysis quality

ML, AL, and PT independently rated the quality of individual meta-analysis on the following 25 points found in the PRISMA checklist [ 20 ]: title; abstract structured summary; introduction rationale, objectives, and protocol and registration; methods eligibility criteria, information sources, search, study selection, data collection process, data items, risk of bias of individual studies, summary measures, synthesis of results, and risk of bias across studies; results study selection, study characteristics, risk of bias within studies, results of individual studies, synthesis of results, and risk of bias across studies; discussion summary of evidence, limitations, and conclusions; and funding. All meta-analyses were rated for quality by two coders to facilitate inter-coder reliability checks, and the mean quality ratings were used in subsequent analyses. One author (PT), having completed his own ratings, received the incoming ratings from ML and AL and ran the inter-coder analysis. Two rounds of ratings occurred due to discrepancies for seven meta-analyses, mainly between ML and AL. As no objective quality categorizations (i.e., a point system for grouping meta-analyses as poor, medium, good) currently exist, each meta-analysis was allocated a quality score of up to a maximum of 25 points. All coding records are available upon request.

Planned methods of analysis

Several preplanned methods of analysis occurred. We first assessed the mean quality rating of each meta-analysis based on our 25-point PRISMA-based rating system. Next, we used a median split of quality ratings to determine whether standardized mean effects (SMDs) differed by the two formed categories, higher and lower quality meta-analyses. Meta-analysis authors reported either of two different effect size metrics (i.e., r and SMD); hence we converted all correlational effects to SMD (i.e., Cohen’s d ) values using an online effect size calculator ( www.polyu.edu.hk/mm/effectsizefaqs/calculator/calculator.html ). We interpreted the meaningfulness of effects based on Cohen’s interpretation [ 24 ] with 0.20 as small, 0.50 as medium, 0.80 as large, and 1.30 as very large. As some psychological variables associate negatively with performance (e.g., confusion [ 25 ], cognitive anxiety [ 26 ]) whereas others associate positively (e.g., cohesion [ 23 ], mental practice [ 14 ]), we grouped meta-analyses according to whether the hypothesized effect with performance was positive or negative, and summarized the overall effects separately. By doing so, we avoided a scenario whereby the demonstrated positive and negative effects canceled one another out when combined. The effect of somatic anxiety on performance, which is hypothesized to follow an inverted-U relationship, was categorized as neutral [ 35 ]. Last, we grouped the included meta-analyses according to whether the primary studies were correlational in nature or involved an intervention and summarized these two groups of meta-analyses separately.

Study characteristics

Table 1 contains extracted data from 30 meta-analyses meeting the inclusion criteria, dating from 1983 [ 14 ] to 2021 [ 21 ]. The number of primary studies within the meta-analyses ranged from three [ 27 ] to 109 [ 28 ]. In terms of the description of participants included in the meta-analyses, 13 included participants described simply as athletes, whereas other meta-analyses identified a mix of elite athletes (e.g., professional, Olympic), recreational athletes, college-aged volunteers (many from sport science departments), younger children to adolescents, and adult exercisers. Of the 30 included meta-analyses, the majority ( n = 18) were published since 2010. The decadal breakdown of meta-analyses was 1980–1989 ( n = 1 [ 14 ]), 1990–1999 ( n = 6 [ 29 – 34 ]), 2000–2009 ( n = 5 [ 23 , 25 , 26 , 35 , 36 ]), 2010–2019 ( n = 12 [ 18 , 19 , 22 , 27 , 37 – 43 , 48 ]), and 2020–2021 ( n = 6 [ 21 , 28 , 44 – 47 ]).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408.t001

As for the constructs covered, we categorized the 30 meta-analyses into the following areas: mental practice/imagery [ 14 , 29 , 30 , 42 , 46 , 47 ], anxiety [ 26 , 31 , 32 , 35 ], confidence [ 26 , 35 , 36 ], cohesion [ 18 , 19 , 23 ], goal orientation [ 22 , 44 , 48 ], mood [ 21 , 25 , 34 ], emotional intelligence [ 40 ], goal setting [ 33 ], interventions [ 37 ], mindfulness [ 27 ], music [ 28 ], neurofeedback training [ 43 ], perfectionism [ 39 ], pressure training [ 45 ], quiet eye training [ 41 ], and self-talk [ 38 ]. Multiple effects were generated from meta-analyses that included more than one construct (e.g., tension, depression, etc. [ 21 ]; anxiety and confidence [ 26 ]). In relation to whether the meta-analyses included in our review assessed the effects of a sport psychology intervention on performance or relationships between psychological constructs and performance, 13 were intervention-based, 14 were correlational, two included a mix of study types, and one included a large majority of cross-sectional studies ( Table 1 ).

A wide variety of performance outcomes across many sports was evident, such as golf putting, dart throwing, maximal strength, and juggling; or categorical outcomes such as win/loss and Olympic team selection. Given the extensive list of performance outcomes and the incomplete descriptions provided in some meta-analyses, a clear categorization or count of performance types was not possible. Sufficient to conclude, researchers utilized many performance outcomes across a wide range of team and individual sports, motor skills, and strength and aerobic tasks.

Effect size data and bias correction

To best summarize the effects, we transformed all correlations to SMD values (i.e., Cohen’s d ). Across all included meta-analyses shown in Table 2 and depicted in Fig 2 , we identified 61 effects. Having corrected for bias, effect size values were assessed for meaningfulness [ 24 ], which resulted in 15 categorized as negligible (< ±0.20), 29 as small (±0.20 to < 0.50), 13 as moderate (±0.50 to < 0.80), 2 as large (±0.80 to < 1.30), and 1 as very large (≥ 1.30).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408.g002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408.t002

Study quality rating results and summary analyses

Following our PRISMA quality ratings, intercoder reliability coefficients were initially .83 (ML, AL), .95 (ML, PT), and .90 (AL, PT), with a mean intercoder reliability coefficient of .89. To achieve improved reliability (i.e., r mean > .90), ML and AL re-examined their ratings. As a result, intercoder reliability increased to .98 (ML, AL), .96 (ML, PT), and .92 (AL, PT); a mean intercoder reliability coefficient of .95. Final quality ratings (i.e., the mean of two coders) ranged from 13 to 25 ( M = 19.03 ± 4.15). Our median split into higher ( M = 22.83 ± 1.08, range 21.5–25, n = 15) and lower ( M = 15.47 ± 2.42, range 13–20.5, n = 15) quality groups produced significant between-group differences in quality ( F 1,28 = 115.62, p < .001); hence, the median split met our intended purpose. The higher quality group of meta-analyses were published from 2015–2021 (median 2018) and the lower quality group from 1983–2014 (median 2000). It appears that meta-analysis standards have risen over the years since the PRISMA criteria were first introduced in 2009. All data for our analyses are shown in Table 2 .

Table 3 contains summary statistics with bias-corrected values used in the analyses. The overall mean effect for sport psychology constructs hypothesized to have a positive impact on performance was of moderate magnitude ( d = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.42, 0.58, n = 36). The overall mean effect for sport psychology constructs hypothesized to have a negative impact on performance was small in magnitude ( d = -0.21, 95% CI -0.31, -0.11, n = 24). In both instances, effects were larger, although not significantly so, among meta-analyses of higher quality compared to those of lower quality. Similarly, mean effects were larger but not significantly so, where reported effects in the original studies were based on interventional rather than correlational designs. This trend only applied to hypothesized positive effects because none of the original studies in the meta-analyses related to hypothesized negative effects used interventional designs.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408.t003

In this systematic review of meta-analyses, we synthesized the available evidence regarding effects of sport psychology interventions/constructs on sport performance. We aimed to consolidate the literature, evaluate the potential for meta-analysis quality to influence the results, and suggest recommendations for future research at both the single study and quantitative review stages. During the systematic review process, several meta-analysis characteristics came to light, such as the number of meta-analyses of sport psychology interventions (experimental designs) compared to those summarizing the effects of psychological constructs (correlation designs) on performance, the number of meta-analyses with exclusively athletes as participants, and constructs featuring in multiple meta-analyses, some of which (e.g., cohesion) produced very different effect size values. Thus, although our overall aim was to evaluate the strength of the evidence base for use of psychological interventions in sport, we also discuss the impact of these meta-analysis characteristics on the reliability of the evidence.

When seen collectively, results of our review are supportive of using sport psychology techniques to help improve performance and confirm that variations in psychological constructs relate to variations in performance. For constructs hypothesized to have a positive effect on performance, the mean effect strength was moderate ( d = 0.51) although there was substantial variation between constructs. For example, the beneficial effects on performance of task cohesion ( d = 1.00) and self-efficacy ( d = 0.82) are large, and the available evidence base for use of mindfulness interventions suggests a very large beneficial effect on performance ( d = 1.35). Conversely, some hypothetically beneficial effects (2 of 36; 5.6%) were in the negligible-to-small range (0.15–0.20) and most beneficial effects (19 of 36; 52.8%) were in the small-to-moderate range (0.22–0.49). It should be noted that in the world of sport, especially at the elite level, even a small beneficial effect on performance derived from a psychological intervention may prove the difference between success and failure and hence small effects may be of great practical value. To put the scale of the benefits into perspective, an authoritative and extensively cited review of healthy eating and physical activity interventions [ 49 ] produced an overall pooled effect size of 0.31 (compared to 0.51 for our study), suggesting sport psychology interventions designed to improve performance are generally more effective than interventions designed to promote healthy living.

Among hypothetically negative effects (e.g., ego climate, cognitive anxiety, depression), the mean detrimental effect was small ( d = -0.21) although again substantial variation among constructs was evident. Some hypothetically negative constructs (5 of 24; 20.8%) were found to actually provide benefits to performance, albeit in the negligible range (0.02–0.12) and only two constructs (8.3%), both from Lochbaum and colleagues’ POMS meta-analysis [ 21 ], were shown to negatively affect performance above a moderate level (depression: d = -0.64; total mood disturbance, which incorporates the depression subscale: d = -0.84). Readers should note that the POMS and its derivatives assess six specific mood dimensions rather than the mood construct more broadly, and therefore results should not be extrapolated to other dimensions of mood [ 50 ].

Mean effects were larger among higher quality than lower quality meta-analyses for both hypothetically positive ( d = 0.54 vs d = 0.45) and negative effects ( d = -0.25 vs d = 0.17), but in neither case were the differences significant. It is reasonable to assume that the true effects were derived from the higher quality meta-analyses, although our conclusions remain the same regardless of study quality. Overall, our findings provide a more rigorous evidence base for the use of sport psychology techniques by practitioners than was previously available, representing a significant contribution to knowledge. Moreover, our systematic scrutiny of 30 meta-analyses published between 1983 and 2021 has facilitated a series of recommendations to improve the quality of future investigations in the sport psychology area.

Recommendations

The development of sport psychology as an academic discipline and area of professional practice relies on using evidence and theory to guide practice. Hence, a strong evidence base for the applied work of sport psychologists is of paramount importance. Although the beneficial effects of some sport psychology techniques are small, it is important to note the larger performance benefits for other techniques, which may be extremely meaningful for applied practice. Overall, however, especially given the heterogeneity of the observed effects, it would be wise for applied practitioners to avoid overpromising the benefits of sport psychology services to clients and perhaps underdelivering as a result [ 1 ].

The results of our systematic review can be used to generate recommendations for how the profession might conduct improved research to better inform applied practice. Much of the early research in sport psychology was exploratory and potential moderating variables were not always sufficiently controlled. Terry [ 51 ] outlined this in relation to the study of mood-performance relationships, identifying that physical and skills factors will very likely exert a greater influence on performance than psychological factors. Further, type of sport (e.g., individual vs. team), duration of activity (e.g., short vs. long duration), level of competition (e.g., elite vs. recreational), and performance measure (e.g., norm-referenced vs. self-referenced) have all been implicated as potential moderators of the relationship between psychological variables and sport performance [ 51 ]. To detect the relatively subtle effects of psychological effects on performance, research designs need to be sufficiently sensitive to such potential confounds. Several specific methodological issues are worth discussing.

The first issue relates to measurement. Investigating the strength of a relationship requires the measured variables to be valid, accurate and reliable. Psychological variables in the meta-analyses we reviewed relied primarily on self-report outcome measures. The accuracy of self-report data requires detailed inner knowledge of thoughts, emotions, and behavior. Research shows that the accuracy of self-report information is subject to substantial individual differences [ 52 , 53 ]. Therefore, self-report data, at best, are an estimate of the measure. Measurement issues are especially relevant to the assessment of performance, and considerable measurement variation was evident between meta-analyses. Some performance measures were more sensitive, especially those assessing physical performance relative to what is normal for the individual performer (i.e., self-referenced performance). Hence, having multiple baseline indicators of performance increases the probability of identifying genuine performance enhancement derived from a psychological intervention [ 54 ].

A second issue relates to clarifying the rationale for how and why specific psychological variables might influence performance. A comprehensive review of prerequisites and precursors of athletic talent [ 55 ] concluded that the superiority of Olympic champions over other elite athletes is determined in part by a range of psychological variables, including high intrinsic motivation, determination, dedication, persistence, and creativity, thereby identifying performance-related variables that might benefit from a psychological intervention. Identifying variables that influence the effectiveness of interventions is a challenging but essential issue for researchers seeking to control and assess factors that might influence results [ 49 ]. A key part of this process is to use theory to propose the mechanism(s) by which an intervention might affect performance and to hypothesize how large the effect might be.

A third issue relates to the characteristics of the research participants involved. Out of convenience, it is not uncommon for researchers to use undergraduate student participants for research projects, which may bias results and restrict the generalization of findings to the population of primary interest, often elite athletes. The level of training and physical conditioning of participants will clearly influence their performance. Highly trained athletes will typically make smaller gains in performance over time than novice athletes, due to a ceiling effect (i.e., they have less room for improvement). For example, consider runner A, who takes 20 minutes to run 5km one week but 19 minutes the next week, and Runner B who takes 30 minutes one week and 25 minutes the next. If we compare the two, Runner A runs faster than Runner B on both occasions, but Runner B improved more, so whose performance was better? If we also consider Runner C, a highly trained athlete with a personal best of 14 minutes, to run 1 minute quicker the following week would almost require a world record time, which is clearly unlikely. For this runner, an improvement of a few seconds would represent an excellent performance. Evidence shows that trained, highly motivated athletes may reach performance plateaus and as such are good candidates for psychological skills training. They are less likely to make performance gains due to increased training volume and therefore the impact of psychological skills interventions may emerge more clearly. Therefore, both test-retest and cross-sectional research designs should account for individual difference variables. Further, the range of individual difference factors will be context specific; for example, individual differences in strength will be more important in a study that uses weightlifting as the performance measure than one that uses darts as the performance measure, where individual differences in skill would be more important.

A fourth factor that has not been investigated extensively relates to the variables involved in learning sport psychology techniques. Techniques such as imagery, self-talk and goal setting all require cognitive processing and as such some people will learn them faster than others [ 56 ]. Further, some people are intuitive self-taught users of, for example, mood regulation strategies such as abdominal breathing or listening to music who, if recruited to participate in a study investigating the effects of learning such techniques on performance, would respond differently to novice users. Hence, a major challenge when testing the effects of a psychological intervention is to establish suitable controls. A traditional non-treatment group offers one option, but such an approach does not consider the influence of belief effects (i.e., placebo/nocebo), which can either add or detract from the effectiveness of performance interventions [ 57 ]. If an individual believes that, an intervention will be effective, this provides a motivating effect for engagement and so performance may improve via increased effort rather than the effect of the intervention per se.

When there are positive beliefs that an intervention will work, it becomes important to distinguish belief effects from the proposed mechanism through which the intervention should be successful. Research has shown that field studies often report larger effects than laboratory studies, a finding attributed to higher motivation among participants in field studies [ 58 ]. If participants are motivated to improve, being part of an active training condition should be associated with improved performance regardless of any intervention. In a large online study of over 44,000 participants, active training in sport psychology interventions was associated with improved performance, but only marginally more than for an active control condition [ 59 ]. The study involved 4-time Olympic champion Michael Johnson narrating both the intervention and active control using motivational encouragement in both conditions. Researchers should establish not only the expected size of an effect but also to specify and assess why the intervention worked. Where researchers report performance improvement, it is fundamental to explain the proposed mechanism by which performance was enhanced and to test the extent to which the improvement can be explained by the proposed mechanism(s).

Limitations

Systematic reviews are inherently limited by the quality of the primary studies included. Our review was also limited by the quality of the meta-analyses that had summarized the primary studies. We identified the following specific limitations; (1) only 12 meta-analyses summarized primary studies that were exclusively intervention-based, (2) the lack of detail regarding control groups in the intervention meta-analyses, (3) cross-sectional and correlation-based meta-analyses by definition do not test causation, and therefore provide limited direct evidence of the efficacy of interventions, (4) the extensive array of performance measures even within a single meta-analysis, (5) the absence of mechanistic explanations for the observed effects, and (6) an absence of detail across intervention-based meta-analyses regarding number of sessions, participants’ motivation to participate, level of expertise, and how the intervention was delivered. To ameliorate these concerns, we included a quality rating for all included meta-analyses. Having created higher and lower quality groups using a median split of quality ratings, we showed that effects were larger, although not significantly so, in the higher quality group of meta-analyses, all of which were published since 2015.

Conclusions

Journals are full of studies that investigate relationships between psychological variables and sport performance. Since 1983, researchers have utilized meta-analytic methods to summarize these single studies, and the pace is accelerating, with six relevant meta-analyses published since 2020. Unquestionably, sport psychology and performance research is fraught with limitations related to unsophisticated experimental designs. In our aggregation of the effect size values, most were small-to-moderate in meaningfulness with a handful of large values. Whether these moderate and large values could be replicated using more sophisticated research designs is unknown. We encourage use of improved research designs, at the minimum the use of control conditions. Likewise, we encourage researchers to adhere to meta-analytic guidelines such as PRISMA and for journals to insist on such adherence as a prerequisite for the acceptance of reviews. Although such guidelines can appear as a ‘painting by numbers’ approach, while reviewing the meta-analyses, we encountered difficulty in assessing and finding pertinent information for our study characteristics and quality ratings. In conclusion, much research exists in the form of quantitative reviews of studies published since 1934, almost 100 years after the very first publication about sport psychology and performance [ 2 ]. Sport psychology is now truly global in terms of academic pursuits and professional practice and the need for best practice information plus a strong evidence base for the efficacy of interventions is paramount. We should strive as a profession to research and provide best practices to athletes and the general community of those seeking performance improvements.

Supporting information

S1 checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408.s001

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the work of all academics since Koch in 1830 [ 2 ] for their efforts to research and promote the practice of applied sport psychology.

- 1. Terry PC. Applied Sport Psychology. IAAP Handbook of Applied Psychol. Wiley-Blackwell; 2011 Apr 20;386–410.

- 2. Koch CF. Die Gymnastik aus dem Gesichtspunkte der Diätetik und Psychologie [Callisthenics from the Viewpoint of Dietetics and Psychology]. Magdeburg, Germany: Creutz; 1830.

- 3. Chroni S, Abrahamsen F. History of Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology in Europe. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017 Dec 19. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.135

- 4. Rieger K. Der Hypnotismus: Psychiatrische Beiträge zur Kenntniss der Sogenannten Hypnotischen Zustände [Hypnotism: Psychiatric Contributions to the Knowledge of the So-called Hypnotic States]. Würzburg, Germany: University of Würzburg; 1884.

- 5. Mosso, A. La fatica [Fatigue]. Milan, Italy: Treves; 1891 [trans. 1904].

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 9. Hanrahan SJ, Andersen MB, editors. Routledge Handbook of Applied Sport Psychology. London: Routledge; 2010.

- 10. Schinke RJ, McGannon KR, Smith B, editors. Routledge International Handbook of Sport Psychology. London: Routledge; 2016.

- 11. Bertollo M, Filho E, Terry PC. Advancements in Mental Skills Training: International Perspectives on Key Issues in Sport and Exercise Psychology. London: Routledge; 2021.

- PubMed/NCBI

- 17. Lochbaum M. Understanding the meaningfulness and potential impact of sports psychology on performance. In: Milanović D, Sporiš G, Šalaj S, Škegro D, editors, Proceedings book of 8th International Scientific Conference on Kinesiology, Opatija. Zagreb, Croatia: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Kinesiology; 2017. pp. 486–489.

- 24. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York: Routledge Academic; 1988.

- 50. Ekkekakis P. The Measurement of Affect, Mood, and Emotion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

Essentials of Exercise and Sport Psychology: An Open Access Textbook

(4 reviews)

Zachary Zenko, Bakersfield, CA

Leighton Jones, Sheffield, UK

Copyright Year: 2021

ISBN 13: 9780578932361

Publisher: Society for Transparency, Openness, and Replication in Kinesiology

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by April Parrott, Insctructor, Lane Community College on 9/15/23

This book is definitely very comprehensive. It covers more material than the textbook I was using for this subject. I do wish it had a glossary. I also wish that it covered exercise and disease psychology, but I haven't found a textbook that does... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

This book is definitely very comprehensive. It covers more material than the textbook I was using for this subject. I do wish it had a glossary. I also wish that it covered exercise and disease psychology, but I haven't found a textbook that does this. I was super impressed with the chapters on exercise and music, mindfulness, and COVID.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

The information in the textbook is accurate to the best of my knowledge. There is a lot of supported evidence from past and recent research.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

I was really impressed to have read a chapter on the impact of COVID and body image and physical activity. These are topics that are very relevant and applicable to today's exerciser and athlete.

Clarity rating: 5

The language used was clear and easily understandable. When technical terminology was used it was usually defined well. I didn't find that there was undetailed language or filler words, in addition the writing was quick to make its point which is greatly appreciated!

Consistency rating: 5

Based on the fact that there were so many different authors, I was a little concerned about the consistency and cohesiveness, but there seemed to be little variance from chapter to chapter in delivery of ideas and theories.

Modularity rating: 5

This was probably the best part of this book. I really appreciate when concepts are grouped together well or kept separate for ease of reference and teaching. The topics that were together definitely needed to be together to convey the overall concept. For example, it feels logical to me to keep self-determination theory with social cognitive theory together.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

Somes the organization of a specific chapter seemed odd to me, but it didn't seem to affect my comprehension. For example, chapter 15 did an overview and introduction, then gave the purpose for the chapter which felt odd. Chapters were sometimes grouped well, for example, mindfulness, depression, and anxiety, but other times it felt off. For example, separating COVID, chronic fatigue, and depression. Again, none of this affected comprehension or learning though.

Interface rating: 5

The only option for this is a PDF, which is simple and easy.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

I did not find any gramatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

The photos they chose did cover various nationalities, but I would have loved a chapter on this concept and feel that it is relevant to the topic.

Overall, this was a great text. It was very comprehensive and increased my knowledge base of exercise and sport psychology. I appreciated the chapters that had a section on practical application, and I wish every chapter had this.

Reviewed by Sara Woodward, Exercise and Sport Science Faculty, Dakota County Technical College on 4/25/23

The book has an abundance of content and references. It includes topics that I would not have considered previously. The inclusion of new theories or approaches to motivation and adherence are intriguing. The amount of content related to exercise... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

The book has an abundance of content and references. It includes topics that I would not have considered previously. The inclusion of new theories or approaches to motivation and adherence are intriguing. The amount of content related to exercise psychology is impressive. In previous textbooks I've seen, sport psychology is the focus and exercise psychology is an afterthought. This provides relatively equal focus on each.

The material that I've looked at appears to be free from errors. I would suspect that with the number of authors contributing to this resource, there will be some mistakes. I have not noticed anything that seems biased in any way.

The text includes information about the effects of Covid-19 on sport and exercise psychology. This is an area that will continue to be explored in future research as the consequences of lost athletic seasons and gym closures becomes more apparent. The material may eventually become irrelevant but for now and the foreseeable future, it plays an important role in what it means to be an athlete.

The text contains numerous in-text citations, footnotes, and references. The language is appropriate for undergraduate college coursework. The terminology that is used is clearly defined and/or explained and is essential for discussing the topics presented in the text.

The consistency between authors and chapters reveals an intentional effort to create a common framework for students using the resource. Each chapter has an overview, learning activities, and a reference list. Faculty would be able to incorporate the framework into an 8-week, 16-week, or self-paced course.

Each chapter is broken down into sub-sections which enhances reader focus and eliminates content fatigue. There are just enough illustrations to break up the verbiage. The sub-section format will also be useful for instructors who only want to cover portions of each chapter. It provides a great framework to build the curriculum to meet the needs of the students in a particular course or program.

There does appear to be some overlap between chapters but the fact that the chapters are written by different authors with different perspectives may add rather than detract from the flow of ideas. 33 chapters and nearly 800 pages will likely result in some redundancy, but the choice to layout the concepts for exercise and then return to the topics in a sport setting later adds nuance. The breadth of information will require instructors to streamline the required content so as not to overwhelm students, but students can always dive deeper into the content than what is assigned by the instructor.

Interface rating: 4

Navigation to the specific chapters is easy with links provided through the table of contents. I did not notice any issues with images being distorted. I am viewing this on a PC so I'm not sure how things will look for students reading the material on their phones. The layout of the print is similar to a research paper rather than a textbook. It will be interesting to see how students respond to this format.

There were no obvious grammatical errors in the text. It would not be surprising to find some errors during a deeper dive into the text.

If there is anything missing from this text, it is a chapter on diversity, equity, and inclusivity in sport and exercise settings. With the current debate regarding trans-athletes as well as common race, ethnicity, and gender issues, a chapter that addresses this area would be beneficial. There are illustrations with people from a variety of backgrounds.

There are chapters submitted from authors throughout the world which adds to the richness of the content. This text could easily and adequately replace a traditional published textbook. Thank you to all of the authors that contributed.

Reviewed by Katja Sonkeng, Assistant Professor, James Madison University on 4/16/23

It's a very useful textbook for applied psychology courses, as it provides very practical information for coaches, clinical psychologists and professionals, in addition to a comprehensive overview of theory and research in this area. However, it... read more

It's a very useful textbook for applied psychology courses, as it provides very practical information for coaches, clinical psychologists and professionals, in addition to a comprehensive overview of theory and research in this area. However, it is limited in terms of guidelines for anyone who wants to adopt a new exercise regimen or sport.

The content appears to be accurate, unbiased, and current, further supplement by expert reviews of the literature. Overall, the tone and content varies across the chapters, and empirical reviews are bit limited.

The content seems to be up-to-date, but could be supplemented by recent research findings to make it more valuable to students.

The text is written in fairly easy and straightforward language, with specific theories being consistently spelled out to ensure that everyone can follow and access it equitably.

The text is very consistent in terms of its writing style and use of terminology. For instance, some theories (e.g., social cognitive theory, self-determination theory) are spelled out consistently, which makes the chapters self-contained, so that one could easily choose to read only selected chapters based on their particular interests.

As mentioned above, the chapters are somewhat standalone and not building upon one another, which makes it more flexible to adopt in the classroom.

The order of the chapters is a bit awkward and random, as for instance the first chapters should establish the different levels of analysis and types of exercise, physical activity, and sports.

The design is straightforward with helpful visual aids here and there.

I did not catch any grammatical or spelling errors in my reading.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

The text could include a bit more context on sociocultural differences and how it impacts participation in sport and physical exercise.

Overall, I think it's a solid textbook for an undergraduate course, if the focus is on applied sport and exercise psychology. However, at times, the intended audience was not clear and it seemed more aimed at scholars and researchers than students.

Reviewed by David Haaga, Professor, American University on 11/3/22

There is limited information from the vantage point of a person attempting to take up an exercise regimen or new sport, but there is comprehensive coverage relating to theory and research in this vein, as well as practical information for coaches,... read more

There is limited information from the vantage point of a person attempting to take up an exercise regimen or new sport, but there is comprehensive coverage relating to theory and research in this vein, as well as practical information for coaches, rehab professionals, and investigators.

Many of the chapters contain up-to-date, expert reviews of the literature. The tone and content vary a good deal across chapters, and some are more overview of different perspectives rather than empirical reviews, but either way the content seemed accurate and unbiased.

The basic principles are unlikely to change, but as more research is completed on, say, the validity of a new model of the relevance of affective associations to uptake of physical activity (ch. 4), it should be feasible to update the material.

The writing is straightforward and fairly engaging, and little background is assumed.

Almost to a fault there is consistency. Some basic points (social cognitive theory, self-determination theory) are spelled out repeatedly. This has the advantage of making the chapters self-contained, so that one could easily read the text selectively according to interests, but if someone does read it start to finish skimming will be needed.

As noted in prior comment, the chapters are independent and really could be read in any order.

The first chapter on levels of analysis, and distinctions among exercise, physical activity, and sport should indeed be first. After that, it seemed almost random.

design is fairly simple, mainly the occasional figure or photo. I don't imagine there would be problems.

I did not notice problems in this vein, which is a good sign

Many of the chapters do not include much on this issue, though I suspect that is more a function of the available literature than any fault of the textbook editors.

The intended audience was not always clear. For the most part, I think advanced undergraduate courses could make good use of it. But some seemed aimed more at fellow researchers in the sub-area in question.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1. Introduction to Exercise Psychology

- Chapter 2. Theories of Physical Activity

- Chapter 3. Promoting Self-Determined Motivation for Physical Activity: From Theory to Intervention Work

- Chapter 4. Exercise Behavior Change Revisited: Affective-Reflective Theory

- Chapter 5. Predictors and Correlates of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior

- Chapter 6. Personality and Physical Activity

- Chapter 7. Body Image and Physical Activity

- Chapter 8. Youth Physical Activity and Considerations for Interventions

- Chapter 9. Emotion Regulation of Others and Self (EROS) During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Chapter 10. Social Support, Relationships, and Physical Activity

- Chapter 11. Strategies to Facilitate More Pleasant Exercise Experiences

- Chapter 12. Affective Responses to Exercise: Measurement Considerations for Practicing Professionals

- Chapter 13. Perceived Effort and Exertion

- Chapter 14. Mindfulness in Physical Activity

- Chapter 15. Exercise and Physical Activity for Depression

- Chapter 16. Physical Activity and Exercise for the Prevention and Management of Anxiety

- Chapter 17. Physical Activity and Severe Mental Illness

- Chapter 18. Exercise and Chronic Fatigue

- Chapter 19. Taking the Field: An Introduction to the Field of Sport Psychology

- Chapter 20. Get Your Head in the Game: Examining the Use of Psychological Skills in Sport

- Chapter 21. Motivation in Coaching: Promoting Adaptive Psychological Outcomes

- Chapter 22. Self-Control in Sports

- Chapter 23. Music in Sport: From Conceptual Underpinnings to Applications

- Chapter 24. Values-Based Coaching: The Role Coaches in Moral Development

- Chapter 25. Leadership Development in Sports Teams

- Chapter 26. Group Dynamics in Sport

- Chapter 27. Self, Relational, and Collective Efficacy in Athletes

- Chapter 28. Diagnosing Problems, Prescribing Solutions, and Advancing Athlete Burnout Research

- Chapter 29. Psychological Stress and Performance

- Chapter 30. Organizational Stress in Competitive Sport

- Chapter 31. Rehabilitation from Sport Injury: A Social Support Perspective

- Chapter 32. Promoting Adherence to Rehabilitation through Supporting Patient Well-Being: A Self-Determination Perspective

- Chapter 33. Working in Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology

Ancillary Material

About the book.

This text represents the collaboration of more than 70 authors from multiple countries. Essentials of Exercise and Sport Psychology: An Open Access Textbook brings this diverse set of experts together to provide a free, open, accessible textbook for students studying exercise and sport psychology. Primarily directed at undergraduate students, this well-referenced book is also appropriate for graduate students. The topics covered are broad, ranging from an Introduction to Exercise Psychology (Chapter 1), to an Introduction to Sport Psychology (Chapter 19), to Working in Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology (Chapter 33). Importantly, students should recognize that each author brings their individual perspectives, experiences, and expertise to this book. Therefore, some chapters may share overlapping content, but the content is discussed in unique ways. For example, Chapters 2, 3, 4, and 5 focus on physical activity and exercise behavior. While content in these chapters is related, it is not redundant. To fully understand the complex world of exercise and sport psychology, students are encouraged to engage with diverse perspectives from many authors. Chapters also contain learning exercises to prompt students and instructors to engage with the material on a deeper level. For effective review, students and instructors are encouraged to complete these learning exercises and discuss responses together. The majority of this textbook was written during the global COVID-19 pandemic. We are tremendously grateful for all of the efforts and expertise of the many contributors to this project. Despite the challenges of teaching, researching, and surviving in the pandemic, the authors persisted. As a result, Essentials of Exercise and Sport Psychology: An Open Access Textbook is completed; we think you will enjoy using it as you pursue this challenging and fascinating area of study!

About the Contributors

Zachary Zenko, California State University

Leighton Jones, Sheffield Hallam University

Contribute to this Page

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Sport and exercise psychology

Related Papers

PsycEXTRA Dataset

International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology

Gershon Tenenbaum

Schilling, G. & Apitzsch (eds.)(2003). Sport Psychology …

Reinhard Stelter

There is certainly a need for the further development of sport and exercise psychology. As society changes, psychology must change with it, because psychology in general, and sport psychology in particular, should deal with individual and group behaviour in specific social contexts. ...

Pedagogy and Psychology of Sport

Paweł Piepiora

Background and aim. The important role of sports psychology is often emphasized. But not everyone is aware that it applies to the entire area of physical culture. The aim of this article is to present the role of sports psychology and the positioning of this discipline in physical culture sciences. Matherial and method. The collected material consisted only of the works of sports psychologists available in Poland. The method of source materials analysis was used. Analysis with deductive reasoning and synthesis with inductive reasoning were used. Results. The importance of sport psychology for the sciences of physical culture and its theoretical and practical tasks are presented. Conclusions. Sport psychology is a discipline in the field of physical culture sciences. It deals with theoretical (research, education, diagnosis, analyzes, interventions, counseling) and practical (mental training) mechanisms and laws governing the psyche and human behavior in sport, physical education, to...

Enrique Cantón

exercise, a sufficiently particular field of human activity to be able to establish a professional action pattern that is different from other areas of Psychology? We will attempt to answer this question. In order to successfully approach this consideration and the current analysis of sport psychology and physical exercise, it is first necessary to define it precisely. We begin with the premise that sport psychology does not constitute an area of knowledge within psychological science but that it is a field of professional activity. What characterizes this discipline is its orientation applied to a facet of human activity such as sports in the wider meaning of the term. Therefore, it refers to the intervention area of an applied activity for which it is convenient to develop a specific technology including assessment instruments, intervention programs and specific direct and indirect techniques. Thus, the first step to answering the question concerning professional identity is to es...

Taru Lintunen

International journal of sport and exercise psychology

Kristoffer Henriksen

Attila Szabo

Sports and exercise psychology as a scholastic field was officially inaugurated in 1965 in Rome on the occasion of the first World Congress on Sports Psychology. As it nears its 50th anniversary in 2015, we have conducted a content analysis of the existing six subject specific English-speaking international journals in the field to obtain an overview of research and publication trends. Articles (n = 2276) published between 1 January 2003 and 1 January 2013 were examined. The type of publications, subject of the articles, institutional and national origin, and authors' gender were examined. Results revealed that the subject matter of the articles could be grouped into 45 areas. The majority (79.6%) of the work was empirical. Articles originated from 725 institutions located in 43 nations. Most publications (75%) over the decade reviewed stemmed from only five, mainly Anglophone, nations. First and second authorships were largely by male scholars (64.7% vs. 68.2%). Compared to 200...

The field of sport, games, physical activity and body culture is changing as society is changing. Here, like in other cultural and social fields of our daily life, we can observe and experience a rapid and often confusing development , where researchers and practitioners are called on to find answers to the new questions of our time. Sport and exercise psychologists should face the challenges for their discipline by including new theoretical approaches in their thinking, by contextualising their research, and by applying new strategies for sport psychological interventions. The authors of this book would like to support the further development of their discipline by • challenging the theoretical foundations of sport and exercise psychology • introducing a cultural, social, and environmental perspective • presenting new theoretical approaches and new applied intervention strategies

Psychology of Sport and Exercise

Stuart Biddle

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Asheek Shimul

International Journal of Yoga, Physiotherapy and Physical Education

Rohit Adling

Apostolos S Theodorou

Professional Psychology: Research and Practice

Mark Aoyagi , Traci Statler , Alexander Cohen

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION AND SPORTS (IJPES)

Urban Johnson

Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science

Leonard Zaichkowsky

Robert Schinke

Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology

Jeffrey Martin

Tatiana V Ryba

Marta Pérez Villalba

Journal of Education

Richard Keegan

International Journal for Research in Applied Science & Engineering Technology (IJRASET)

IJRASET Publication

candice van Rensburg

Markus Raab

Raquel Dunkman

Stephen Mellalieu

Routledge eBooks

Dieter Hackfort

Caroline Heaney

Jesse van der Zande

The Sport Psychologist

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

COMMENTS

Sports Psychology: Exploring the Origins, Development, and Increasing Demands in Sports and Exercise Sciences June 2023 International Journal of Indian Psychology 11(2):1322-1334