- COVID-19 Tracker

- Biochemistry

- Anatomy & Physiology

- Microbiology

- Neuroscience

- Animal Kingdom

- NGSS High School

- Latest News

- Editors’ Picks

- Weekly Digest

- Quotes about Biology

Experimental Group

Reviewed by: BD Editors

Experimental Group Definition

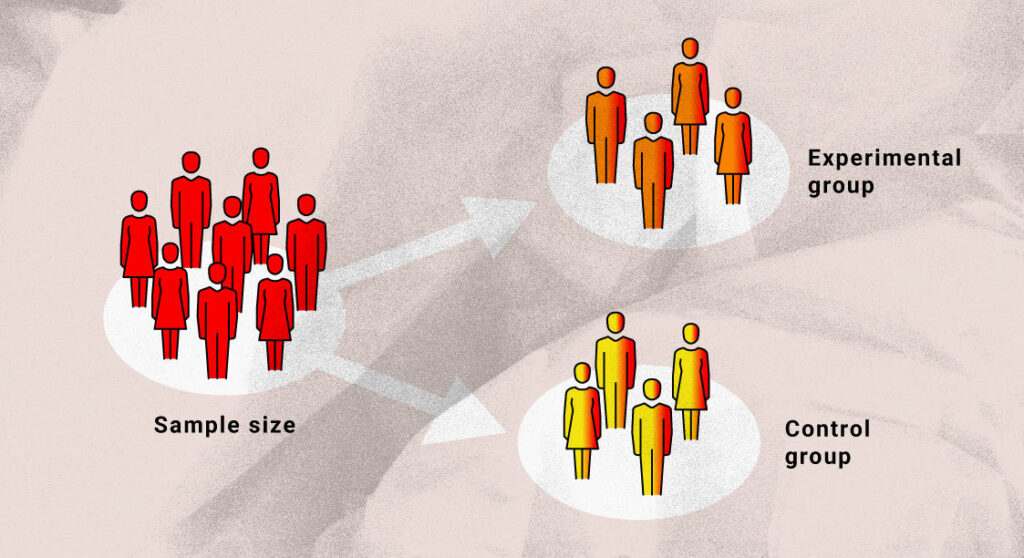

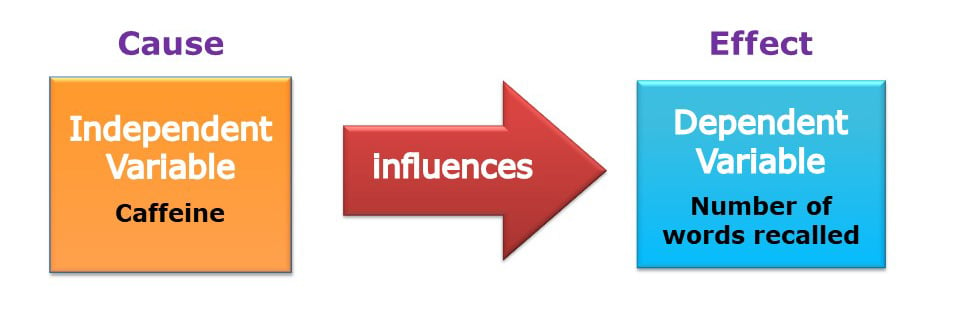

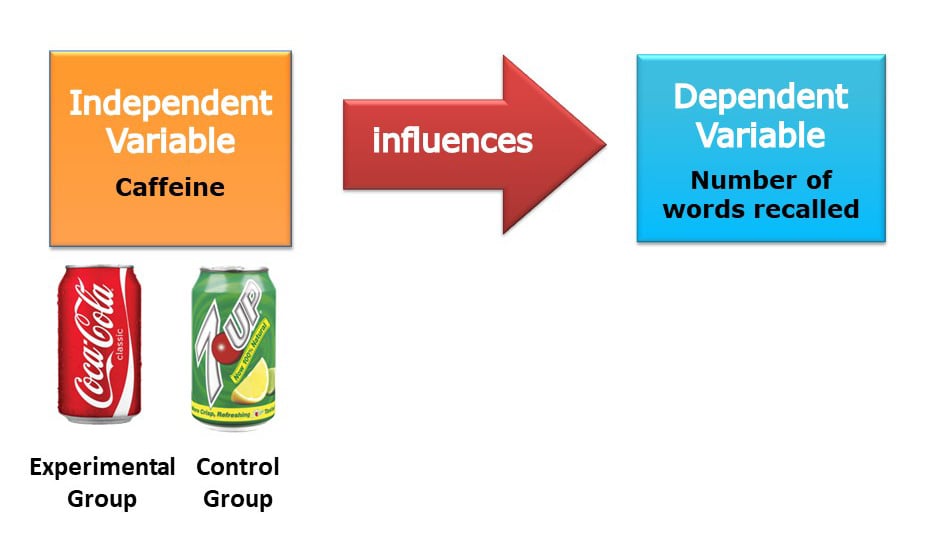

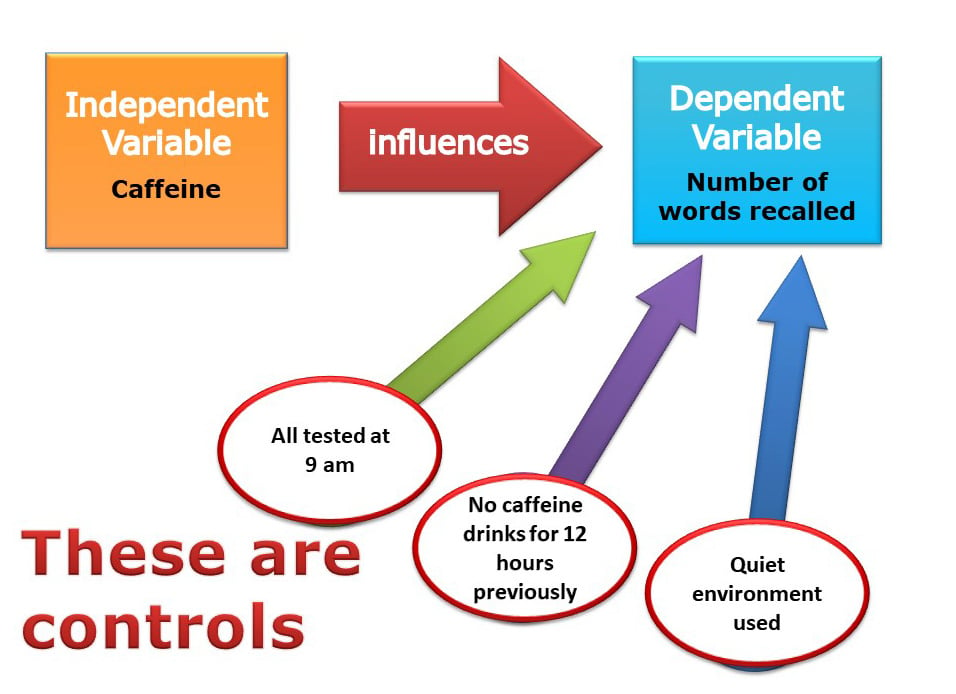

In a comparative experiment, the experimental group (aka the treatment group) is the group being tested for a reaction to a change in the variable. There may be experimental groups in a study, each testing a different level or amount of the variable. The other type of group, the control group , can show the effects of the variable by having a set amount, or none, of the variable. The experimental groups vary in the level of variable they are exposed to, which shows the effects of various levels of a variable on similar organisms.

In biological experiments, the subjects being studied are often living organisms. In such cases, it is desirable that all the subjects be closely related, in order to reduce the amount of genetic variation present in the experiment. The complicated interactions between genetics and the environment can cause very peculiar results when exposed to the same variable. If the organisms being tested are not related, the results could be the effects of the genetics and not the variable. This is why new human drugs must be rigorously tested in a variety of animals before they can be tested on humans. These different experimental groups allow researchers to see the effects of their drug on different genetics. By using animals that are closer and closer in their relation to humans, eventually human trials can take place without severe risks for the first people to try the drug.

Examples of Experimental Group

A simple experiment.

A student is conducting an experiment on the effects music has on growing plants. The student wants to know if music can help plants grow and, if so, which type of music the plants prefer. The students divide a group of plants in to two main groups, the control group and the experimental group. The control group will be kept in a room with no music, while the experimental group will be further divided into smaller experimental groups. Each of the experimental groups is placed in a separate room, with a different type of music.

Ideally, each room would have many plants in it, and all the plants used in the experiment would be clones of the same plant. Even more ideally, the plant would breed true, or would be homozygous for all genes. This would introduce the smallest amount of genetic variation into the experiment. By limiting all other variables, such as the temperature and humidity, the experiment can determine with validity that the effects produced in each room are attributable to the music, and nothing else.

Bugs in the River

To study the effects of variable on many organisms at once, scientist sometimes study ecosystems as a whole. The productivity of these ecosystems is often determined by the amount of oxygen they produce, which is an indication of how much algae is present. Ecologists sometimes study the interactions of organisms on these environments by excluding or adding organisms to an experimental group of ecosystems, and test the effects of their variable against ecosystems with no tampering. This method can sometimes show the drastic effects that various organisms have on an ecosystem.

Many experiments of this kind take place, and a common theme is to separate a single ecosystem into parts, with artificial divisions. Thus, a river could be separated by netting it into areas with and without bugs. The area with no nets allows bugs into the water. The bugs not only eat algae, but die and provide nutrients for the algae to grow. Without the bugs, various effects can be seen on the experimental portion of the river, covered by netting. The levels of oxygen in the water in each system can be measured, as well as other indicators of water quality. By comparing these groups, ecologists can begin to discern the complex relationships between populations of organisms in the environment.

Related Biology Terms

- Control Group – The group that remains unchanged during the experiment, to provide comparison.

- Scientific Method – The process scientists use to obtain valid, repeatable results.

- Comparative Experiment – An experiment in which two groups, the control and experiment groups, are compared.

- Validity – A measure of whether an experiment was caused by the changes in the variable, or simply the forces of chance.

Cite This Article

Subscribe to our newsletter, privacy policy, terms of service, scholarship, latest posts, white blood cell, t cell immunity, satellite cells, embryonic stem cells, popular topics, hydrochloric acid, endocrine system, acetic acid, adenosine triphosphate (atp), amino acids.

The Role of Experimental Groups in Research

Understanding the Role of Experimental Group. Explore the significance and characteristics of experimental groups in scientific research.

The concept of an experimental group is a fundamental component of scientific research, particularly in fields such as psychology, medicine, and social sciences. It serves as a crucial element in studying cause-and-effect relationships and investigating the effectiveness of interventions or treatments. In experimental research, the experimental group is the group that receives the intervention or treatment being studied, allowing researchers to compare and analyze its effects. Understanding the purpose, characteristics, and considerations associated with the experimental group is essential for conducting rigorous and reliable scientific investigations.

Definition of Experimental Group

The experimental group is a vital component in scientific research, particularly in experimental studies. It refers to a specific group of participants or subjects who receive a particular treatment, condition, or intervention that is being studied. The experimental group allows researchers to explore the effects or outcomes resulting from the manipulation of a variable of interest. By comparing the experimental group to a control group, which does not receive the treatment, researchers can assess the impact of the manipulated variable. To learn more about the control group, access this website .

The experimental group plays a crucial role in providing insights into the causal relationships between variables and contributes to advancing knowledge in various fields of study. It helps researchers draw meaningful conclusions and make informed decisions based on the results obtained. Understanding the concept and importance of the experimental group is essential for researchers and students alike, as it enables them to design and conduct rigorous experiments, analyze data accurately, and draw valid conclusions from their research findings.

Purpose of an Experimental Group

The purpose of an experimental group is to investigate the effects or outcomes of a specific treatment, condition, or intervention. By assigning participants or subjects to the experimental group, researchers can manipulate an independent variable and observe how it influences the dependent variable. The experimental group allows researchers to test hypotheses, explore cause-and-effect relationships, and determine whether the treatment or intervention produces any significant changes or effects.

It serves as a comparison group to assess the impact of the manipulated variable, as it receives the specific treatment being studied. The purpose of the experimental group is to provide insights into the causal relationships between variables and to contribute to the accumulation of knowledge in a particular field. Through the use of an experimental group, researchers can draw conclusions about the effectiveness, efficacy, or impact of the treatment or intervention under investigation.

Characteristics of an Experimental Group

The characteristics ensure that the experimental group provides a basis for making valid inferences about the relationship between the treatment and the outcomes being studied. Some characteristics of an experimental group include the following:

Exposure to Treatment

The experimental group is exposed to the specific treatment, intervention, or condition being studied. This could be a new drug, an educational program, a modified environment, or any other variable under investigation.

Manipulated Variable

In experimental research, the independent variable is deliberately manipulated or controlled by the researchers. The experimental group receives the manipulated variable or treatment, which sets it apart from the control group.

Comparison with Control Group

The experimental group is compared to a control group, which does not receive the treatment or intervention. This allows researchers to assess the effects of the treatment by comparing the outcomes or responses between the two groups.

Random Assignment

Participants in the experimental group are randomly assigned to ensure that the groups are similar in terms of relevant variables, such as age, gender, or prior experience. Random assignment minimizes the influence of confounding factors and increases the validity of the results.

Data Collection

Data is collected from the experimental group to measure the outcomes or responses of interest. This could involve surveys, observations, tests, or other measurement methods depending on the research design and objectives.

Analysis of Results

The data collected from the experimental group is analyzed using appropriate statistical techniques to determine the significance and magnitude of the treatment effects. This analysis helps researchers draw conclusions about the impact of the treatment on the measured variables.

Examples of Experimental Groups

These examples illustrate how experimental groups are utilized in various research studies to assess the impact of specific interventions or treatments on outcomes of interest:

Drug Trial: In a drug trial, the experimental group would receive the new medication being tested, while the control group would receive a placebo or a standard treatment.

Educational Intervention: In an educational intervention study, the experimental group may receive a specific teaching method or curriculum, while the control group receives the conventional teaching approach.

Environmental Study: In an environmental study, the experimental group could be exposed to an altered environment, such as different lighting conditions or temperature, while the control group remains in the standard environment.

Exercise Program: In a study examining the effects of an exercise program, the experimental group would participate in a specific exercise regimen, while the control group would not engage in any structured exercise.

Behavioral Intervention: In a behavioral intervention study, the experimental group might receive behavioral therapy or intervention aimed at changing specific behaviors, while the control group does not receive the intervention.

Dietary Study: In a dietary study, the experimental group would follow a particular diet plan, such as a low-carbohydrate diet, while the control group maintains their regular diet.

Advantages and Disadvantages of an Experimental Group

Advantages of an experimental group, controlled conditions.

The experimental group allows for the manipulation and control of variables, providing researchers with a controlled setting to study cause-and-effect relationships.

Comparative Analysis

By comparing the outcomes of the experimental group to a control group, researchers can determine the specific effects of the intervention or treatment being studied.

Experimental groups enable researchers to measure and quantify the effects of the intervention with a higher level of precision, enhancing the reliability of the study results.

Replicability

Experimental groups offer the opportunity for other researchers to replicate the study, further validating the findings and contributing to scientific knowledge.

Disadvantages of an Experimental Group

Ethical considerations.

In some cases, the experimental group may be subjected to potentially harmful interventions or treatments, raising ethical concerns regarding the well-being and informed consent of participants.

Limitations on Generalizability

Findings from the experimental group may not necessarily apply to the broader population, as the specific conditions and characteristics of the group may limit the generalizability of the results.

Time and Resource Intensive

Conducting experimental research requires significant time, effort, and resources, including recruiting participants, implementing interventions, and collecting and analyzing data.

Potential for Bias

Despite efforts to control variables, biases can still influence the outcomes in the experimental group, leading to biased or inaccurate results.

Ready-to-go templates in all popular sizes

Mind the Graph platform provides a comprehensive solution for scientists, offering a range of features that facilitate scientific communication and data visualization. One of the standout features is the availability of ready-to-go templates in all popular sizes. These templates serve as a time-saving resource, allowing scientists to quickly create visually appealing and professional graphics without the need for extensive design skills or starting from scratch.

Whether it’s creating research posters, presentations, infographics, or scientific illustrations, the platform’s diverse library of templates ensures that scientists can effectively communicate their findings and ideas in a visually engaging manner. With Mind the Graph platform, scientists can focus more on their research and let the templates provide the visual impact needed to effectively convey their scientific work.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

Sign Up for Free

Try the best infographic maker and promote your research with scientifically-accurate beautiful figures

no credit card required

Content tags

Get extra -20% OFF THE ALL-IN-ONE COURSE with "EXTRA20"

SAVE UP TO -50%

ON YOUR FIRST PURCHASE

- Clinical Research Explained

Experimental Group

- 8. February 2024

Definition of Experimental Group

Role of the experimental group, formation of the experimental group, importance of the experimental group in clinical research, experimental group and the scientific method, experimental group and statistical analysis, challenges and considerations in forming an experimental group, randomization, examples of experimental groups in clinical research, drug trials, behavioral intervention studies.

The term ‘Experimental Group’ is a fundamental concept in the realm of Clinical Research. It refers to the group of subjects in a research study who are exposed to the variable under investigation. This group is contrasted with a ‘Control Group’, which is not exposed to the experimental variable. The comparison between these two groups allows researchers to draw conclusions about the effect of the variable being studied.

Understanding the role of the Experimental Group is crucial for anyone involved in or studying Clinical Research. It is the cornerstone of experimental design , and its proper use ensures the validity and reliability of the results obtained. This article will delve into the intricacies of the Experimental Group, exploring its definition, purpose, formation, and role in Clinical Research.

The Experimental Group, also known as the treatment group, is the group of subjects in a research study who receive the experimental treatment or intervention. This treatment or intervention is the variable that the researcher is interested in studying. The outcomes or effects observed in the Experimental Group are then compared with those in a Control Group, which does not receive the experimental treatment.

The Experimental Group is thus the group that is exposed to the variable of interest. The changes that occur in this group as a result of exposure to the variable provide the data that the researcher uses to draw conclusions about the effect of the variable.

The Experimental Group plays a critical role in Clinical Research. It is the group that provides the data that the researcher uses to draw conclusions about the effect of the variable being studied. Without an Experimental Group, it would be impossible to determine whether the variable has any effect at all.

The Experimental Group is also crucial for establishing causality. By comparing the outcomes in the Experimental Group with those in the Control Group, the researcher can determine whether the variable causes any changes in the outcome. If the outcomes are different in the two groups, then it can be concluded that the variable has an effect.

The formation of the Experimental Group is a critical step in the design of a research study. The subjects in the Experimental Group must be selected in a way that ensures that they are representative of the population that the researcher is interested in studying. This is typically achieved through random selection and assignment, which helps to ensure that the Experimental Group is similar to the Control Group in all respects except for the variable being studied.

Once the subjects have been selected, they are assigned to the Experimental Group and exposed to the variable. The researcher then observes the effects of the variable on the subjects in the Experimental Group and compares these effects with those observed in the Control Group.

The Experimental Group is of paramount importance in Clinical Research. It is the group that provides the data that the researcher uses to draw conclusions about the effect of the variable being studied. Without an Experimental Group, it would be impossible to determine whether the variable has any effect at all.

Moreover, the Experimental Group is crucial for establishing causality. By comparing the outcomes in the Experimental Group with those in the Control Group, the researcher can determine whether the variable causes any changes in the outcome. If the outcomes are different in the two groups, then it can be concluded that the variable has an effect.

The Experimental Group is a key component of the scientific method, which is the process that scientists use to investigate phenomena, acquire new knowledge, or correct and integrate previous knowledge. The scientific method involves formulating hypotheses, conducting experiments to test these hypotheses, and analyzing the results to draw conclusions.

In the context of the scientific method, the Experimental Group is the group that is exposed to the experimental variable, or the factor that the researcher is testing. The results obtained from the Experimental Group are then compared with those from the Control Group, which is not exposed to the experimental variable. This comparison allows the researcher to determine whether the experimental variable has an effect, and if so, what that effect is.

The data obtained from the Experimental Group is typically subjected to statistical analysis to determine whether the observed effects are statistically significant. Statistical significance is a measure of the likelihood that the observed effects are due to the experimental variable, rather than chance.

Statistical analysis involves comparing the means of the Experimental Group and the Control Group, and calculating a p-value. If the p-value is less than a predetermined threshold (usually 0.05), then the observed effects are considered statistically significant, and it can be concluded that the experimental variable has an effect.

Forming an Experimental Group is not without its challenges. One of the main challenges is ensuring that the Experimental Group is representative of the population that the researcher is interested in studying. This is typically achieved through random selection and assignment, but this can be difficult to achieve in practice.

Another challenge is ensuring that the Experimental Group and the Control Group are similar in all respects except for the experimental variable. This is crucial for ensuring that any observed effects are due to the experimental variable, and not other factors. However, it can be difficult to control for all potential confounding variables, especially in complex research studies.

Randomization is a technique used in research to ensure that the Experimental Group and the Control Group are similar in all respects except for the experimental variable. It involves randomly assigning subjects to the Experimental Group or the Control Group, which helps to ensure that the two groups are similar in terms of age, gender, health status, and other factors that could potentially influence the outcome of the study.

However, randomization is not always possible or practical. For example, in some research studies, it may not be ethical to randomly assign subjects to the Experimental Group or the Control Group. In such cases, other techniques, such as matching or stratification, may be used to ensure that the two groups are similar.

Blinding is another technique used in research to minimize bias and ensure the validity of the study results. It involves keeping the subjects and/or the researchers unaware of which group (Experimental or Control) the subjects have been assigned to. This helps to prevent the subjects’ and researchers’ expectations from influencing the outcome of the study.

Blinding can be single-blind, where the subjects do not know which group they have been assigned to, or double-blind, where both the subjects and the researchers do not know which group the subjects have been assigned to. Double-blind studies are considered the gold standard in research, as they minimize both subject and researcher bias.

Experimental Groups are used in a wide variety of clinical research studies. For example, in a drug trial, the Experimental Group would be the group of subjects who receive the drug being tested. The effects of the drug on these subjects would then be compared with those in a Control Group, who receive a placebo or a different drug.

In a behavioral intervention study, the Experimental Group might be the group of subjects who receive the intervention, such as a new therapy or counseling technique. The effects of the intervention on these subjects would then be compared with those in a Control Group, who receive standard care or a different intervention.

Drug trials are a common type of clinical research study that use Experimental Groups. In a drug trial, the Experimental Group is the group of subjects who receive the drug being tested. The effects of the drug on these subjects are then compared with those in a Control Group, who receive a placebo or a different drug.

The purpose of a drug trial is to determine whether the drug is safe and effective for treating a particular condition. The data obtained from the Experimental Group is crucial for making this determination. If the drug is found to be safe and effective, it may be approved for use in the general population.

Behavioral intervention studies are another type of clinical research study that use Experimental Groups. In a behavioral intervention study, the Experimental Group is the group of subjects who receive the intervention, such as a new therapy or counseling technique. The effects of the intervention on these subjects are then compared with those in a Control Group, who receive standard care or a different intervention.

The purpose of a behavioral intervention study is to determine whether the intervention is effective for changing behavior or improving health outcomes. The data obtained from the Experimental Group is crucial for making this determination. If the intervention is found to be effective, it may be implemented in clinical practice or public health programs.

In conclusion, the Experimental Group is a fundamental concept in Clinical Research. It is the group of subjects who are exposed to the variable under investigation, and it provides the data that the researcher uses to draw conclusions about the effect of the variable. Understanding the role of the Experimental Group is crucial for anyone involved in or studying Clinical Research.

Despite the challenges involved in forming an Experimental Group, it is a critical component of the scientific method and is essential for establishing causality. By comparing the outcomes in the Experimental Group with those in the Control Group, researchers can determine whether the variable under investigation has an effect, and if so, what that effect is.

Never Miss an important topic

Get a free micro certificate Experimental Group

Enroll now for free and take a short quiz

Free! Add to cart

elevate your skill level

Other Blog-Posts

Which clinical research courses use the latest technologies and methods.

Understanding the Importance of Advanced Clinical Research Courses In the ever-evolving field of clinical research, staying abreast of the latest technologies and methods is crucial. As a clinical research professional,

Can I Find a Clinical Research Course That Offers Payment Plans?

In the evolving field of clinical research, one common question prospective students often have is: “Can I find a clinical research course that offers payment plans?” When considering further education

What Are Former Students Saying About Their Clinical Research Training?

Clinical research training is a crucial step for anyone looking to make a career in the field. But what do former students really think about their training experiences? Let’s dive

Clinical Research certification courses & Packages

Clinical research associate, clinical research project manager academy, clinical study coordinator i.

Get new job posts and all the news about our VIARES clinical research courses in your inbox!

- All Courses

- Verify Certificate

- Privacy Policy

- Term Of Service

- VIARES Trainer

- Contract Sales Specialist

Our support and sales team is available 24 /7 to answer your queries.

Clinical Research Training courses all prices incl. VAT

Control Group vs. Experimental Group: Everything You Need To Know About The Difference Between Control Group And Experimental Group

As someone who is deeply interested in the field of research, you may have heard the terms control group and experimental group thrown around a lot. If you’re not very familiar with these terms, it can be daunting to determine the role they play in research and why they are so important. In layman’s terms, a control group is a group that does not receive any experimental treatment and is used as a benchmark for the group that does receive the treatment. Meanwhile, the experimental group is a group that receives the treatment and is compared to the control group that does not receive the treatment. To put it simply, the main difference between a control group and an experimental group is whether or not they receive the experimental treatment.

Table of Contents

What Is Control Group?

A control group is a group in an experiment that does not receive the experimental treatment and is used as a comparison for the group that does receive the treatment. It is a critical aspect of experimental research to determine whether the treatment caused the outcome rather than another factor. The control group ensures that any observed effects can be attributed to the treatment and not a result of other variables. The quality of the control group can affect the validity of the experiment. Therefore, researchers must carefully design and select participants for the control group to ensure that it accurately represents the population and provides meaningful results. Overall, control groups are essential to gain accurate and reliable results in experimental research.

What Is Experimental Group?

Key differences between control group and experimental group, control group vs. experimental group similarities.

The control group and experimental group are two essential components of any research study. The main similarity between these groups is that they are both used to assess the effects of a treatment or intervention. The control group is intended to provide a baseline measurement of the outcomes that are expected in the absence of the intervention. In contrast, the experimental group is exposed to the intervention or treatment and is observed for any changes or improvements in outcomes. In summary, both groups serve as comparisons for one another, and their use increases the credibility and validity of research findings.

Control Group vs. Experimental Group Pros and Cons

Control group pros & cons, control group pros, control group cons, experimental group pros & cons, experimental group pros.

The Experimental Group, in scientific studies and experimentation, is a group that receives the experimental treatment and is compared to a control group that does not receive the treatment. There are several advantages or pros of this group. First, the experimental group allows researchers to determine the effectiveness of a new treatment or procedure. Second, it helps in identifying side effects of the treatment on the subjects. Third, it provides clear evidence regarding the cause and effect relationships between variables. Additionally, the experimental group enables researchers to validate their findings and test the hypothesis. These benefits make the Experimental Group essential in accurately assessing the effectiveness of new treatments or procedures.

Experimental Group Cons

Comparison table: 5 key differences between control group and experimental group.

| Purpose | Used as a comparison to the experimental group | Receives the intervention being tested |

| Treatment | Receives no intervention or a placebo | Receives the treatment being tested |

| Randomization | Randomly selected from the population being studied | Randomly selected from the population being studied |

| Sample Size | Large enough to provide statistical power | Large enough to provide statistical power |

| Analysis | Statistical analysis is performed to compare outcomes | Statistical analysis is performed to compare outcomes |

Comparison Chart

Comparison video, conclusion: what is the difference between control group and experimental group.

In conclusion, understanding the difference between a control group and an experimental group is crucial in designing and conducting reliable experiments. The control group serves as a baseline, allowing researchers to compare the effects of the experimental treatment. Without a control group, it is difficult to determine whether any observed effects are due to the treatment or to other factors. By contrast, the experimental group receives the treatment and is used to evaluate the effects of the intervention. By carefully controlling for different factors, scientists can use these groups to test hypotheses and draw meaningful conclusions about the impact of different treatments on the outcomes of interest.

Federation vs. Confederation: Everything You Need To Know About The Difference Between Federation And Confederation

Farthest vs. Furthest: Everything You Need To Know About The Difference Between Farthest And Furthest

Miralax vs. Colace: Everything You Need To Know About The Difference Between Miralax And Colace

Dulcolax vs. Miralax: Everything You Need To Know About The Difference Between Dulcolax And Miralax

Adh vs. Aldosterone: Everything You Need To Know About The Difference Between Adh And Aldosterone

Chromebook vs. Laptop: Everything You Need To Know About The Difference Between Chromebook And Laptop

Leave a reply cancel reply, add difference 101 to your homescreen.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

30 8.1 Experimental design: What is it and when should it be used?

Learning objectives.

- Define experiment

- Identify the core features of true experimental designs

- Describe the difference between an experimental group and a control group

- Identify and describe the various types of true experimental designs

Experiments are an excellent data collection strategy for social workers wishing to observe the effects of a clinical intervention or social welfare program. Understanding what experiments are and how they are conducted is useful for all social scientists, whether they actually plan to use this methodology or simply aim to understand findings from experimental studies. An experiment is a method of data collection designed to test hypotheses under controlled conditions. In social scientific research, the term experiment has a precise meaning and should not be used to describe all research methodologies.

Experiments have a long and important history in social science. Behaviorists such as John Watson, B. F. Skinner, Ivan Pavlov, and Albert Bandura used experimental design to demonstrate the various types of conditioning. Using strictly controlled environments, behaviorists were able to isolate a single stimulus as the cause of measurable differences in behavior or physiological responses. The foundations of social learning theory and behavior modification are found in experimental research projects. Moreover, behaviorist experiments brought psychology and social science away from the abstract world of Freudian analysis and towards empirical inquiry, grounded in real-world observations and objectively-defined variables. Experiments are used at all levels of social work inquiry, including agency-based experiments that test therapeutic interventions and policy experiments that test new programs.

Several kinds of experimental designs exist. In general, designs considered to be true experiments contain three basic key features:

- random assignment of participants into experimental and control groups

- a “treatment” (or intervention) provided to the experimental group

- measurement of the effects of the treatment in a post-test administered to both groups

Some true experiments are more complex. Their designs can also include a pre-test and can have more than two groups, but these are the minimum requirements for a design to be a true experiment.

Experimental and control groups

In a true experiment, the effect of an intervention is tested by comparing two groups: one that is exposed to the intervention (the experimental group , also known as the treatment group) and another that does not receive the intervention (the control group ). Importantly, participants in a true experiment need to be randomly assigned to either the control or experimental groups. Random assignment uses a random number generator or some other random process to assign people into experimental and control groups. Random assignment is important in experimental research because it helps to ensure that the experimental group and control group are comparable and that any differences between the experimental and control groups are due to random chance. We will address more of the logic behind random assignment in the next section.

Treatment or intervention

In an experiment, the independent variable is receiving the intervention being tested—for example, a therapeutic technique, prevention program, or access to some service or support. It is less common in of social work research, but social science research may also have a stimulus, rather than an intervention as the independent variable. For example, an electric shock or a reading about death might be used as a stimulus to provoke a response.

In some cases, it may be immoral to withhold treatment completely from a control group within an experiment. If you recruited two groups of people with severe addiction and only provided treatment to one group, the other group would likely suffer. For these cases, researchers use a control group that receives “treatment as usual.” Experimenters must clearly define what treatment as usual means. For example, a standard treatment in substance abuse recovery is attending Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous meetings. A substance abuse researcher conducting an experiment may use twelve-step programs in their control group and use their experimental intervention in the experimental group. The results would show whether the experimental intervention worked better than normal treatment, which is useful information.

The dependent variable is usually the intended effect the researcher wants the intervention to have. If the researcher is testing a new therapy for individuals with binge eating disorder, their dependent variable may be the number of binge eating episodes a participant reports. The researcher likely expects her intervention to decrease the number of binge eating episodes reported by participants. Thus, she must, at a minimum, measure the number of episodes that occur after the intervention, which is the post-test . In a classic experimental design, participants are also given a pretest to measure the dependent variable before the experimental treatment begins.

Types of experimental design

Let’s put these concepts in chronological order so we can better understand how an experiment runs from start to finish. Once you’ve collected your sample, you’ll need to randomly assign your participants to the experimental group and control group. In a common type of experimental design, you will then give both groups your pretest, which measures your dependent variable, to see what your participants are like before you start your intervention. Next, you will provide your intervention, or independent variable, to your experimental group, but not to your control group. Many interventions last a few weeks or months to complete, particularly therapeutic treatments. Finally, you will administer your post-test to both groups to observe any changes in your dependent variable. What we’ve just described is known as the classical experimental design and is the simplest type of true experimental design. All of the designs we review in this section are variations on this approach. Figure 8.1 visually represents these steps.

An interesting example of experimental research can be found in Shannon K. McCoy and Brenda Major’s (2003) study of people’s perceptions of prejudice. In one portion of this multifaceted study, all participants were given a pretest to assess their levels of depression. No significant differences in depression were found between the experimental and control groups during the pretest. Participants in the experimental group were then asked to read an article suggesting that prejudice against their own racial group is severe and pervasive, while participants in the control group were asked to read an article suggesting that prejudice against a racial group other than their own is severe and pervasive. Clearly, these were not meant to be interventions or treatments to help depression, but were stimuli designed to elicit changes in people’s depression levels. Upon measuring depression scores during the post-test period, the researchers discovered that those who had received the experimental stimulus (the article citing prejudice against their same racial group) reported greater depression than those in the control group. This is just one of many examples of social scientific experimental research.

In addition to classic experimental design, there are two other ways of designing experiments that are considered to fall within the purview of “true” experiments (Babbie, 2010; Campbell & Stanley, 1963). The posttest-only control group design is almost the same as classic experimental design, except it does not use a pretest. Researchers who use posttest-only designs want to eliminate testing effects , in which participants’ scores on a measure change because they have already been exposed to it. If you took multiple SAT or ACT practice exams before you took the real one you sent to colleges, you’ve taken advantage of testing effects to get a better score. Considering the previous example on racism and depression, participants who are given a pretest about depression before being exposed to the stimulus would likely assume that the intervention is designed to address depression. That knowledge could cause them to answer differently on the post-test than they otherwise would. In theory, as long as the control and experimental groups have been determined randomly and are therefore comparable, no pretest is needed. However, most researchers prefer to use pretests in case randomization did not result in equivalent groups and to help assess change over time within both the experimental and control groups.

Researchers wishing to account for testing effects but also gather pretest data can use a Solomon four-group design. In the Solomon four-group design , the researcher uses four groups. Two groups are treated as they would be in a classic experiment—pretest, experimental group intervention, and post-test. The other two groups do not receive the pretest, though one receives the intervention. All groups are given the post-test. Table 8.1 illustrates the features of each of the four groups in the Solomon four-group design. By having one set of experimental and control groups that complete the pretest (Groups 1 and 2) and another set that does not complete the pretest (Groups 3 and 4), researchers using the Solomon four-group design can account for testing effects in their analysis.

| Group 1 | X | X | X |

| Group 2 | X | X | |

| Group 3 | X | X | |

| Group 4 | X |

Solomon four-group designs are challenging to implement in the real world because they are time- and resource-intensive. Researchers must recruit enough participants to create four groups and implement interventions in two of them.

Overall, true experimental designs are sometimes difficult to implement in a real-world practice environment. It may be impossible to withhold treatment from a control group or randomly assign participants in a study. In these cases, pre-experimental and quasi-experimental designs–which we will discuss in the next section–can be used. However, the differences in rigor from true experimental designs leave their conclusions more open to critique.

Experimental design in macro-level research

You can imagine that social work researchers may be limited in their ability to use random assignment when examining the effects of governmental policy on individuals. For example, it is unlikely that a researcher could randomly assign some states to implement decriminalization of recreational marijuana and some states not to in order to assess the effects of the policy change. There are, however, important examples of policy experiments that use random assignment, including the Oregon Medicaid experiment. In the Oregon Medicaid experiment, the wait list for Oregon was so long, state officials conducted a lottery to see who from the wait list would receive Medicaid (Baicker et al., 2013). Researchers used the lottery as a natural experiment that included random assignment. People selected to be a part of Medicaid were the experimental group and those on the wait list were in the control group. There are some practical complications macro-level experiments, just as with other experiments. For example, the ethical concern with using people on a wait list as a control group exists in macro-level research just as it does in micro-level research.

Key Takeaways

- True experimental designs require random assignment.

- Control groups do not receive an intervention, and experimental groups receive an intervention.

- The basic components of a true experiment include a pretest, posttest, control group, and experimental group.

- Testing effects may cause researchers to use variations on the classic experimental design.

- Classic experimental design- uses random assignment, an experimental and control group, as well as pre- and posttesting

- Control group- the group in an experiment that does not receive the intervention

- Experiment- a method of data collection designed to test hypotheses under controlled conditions

- Experimental group- the group in an experiment that receives the intervention

- Posttest- a measurement taken after the intervention

- Posttest-only control group design- a type of experimental design that uses random assignment, and an experimental and control group, but does not use a pretest

- Pretest- a measurement taken prior to the intervention

- Random assignment-using a random process to assign people into experimental and control groups

- Solomon four-group design- uses random assignment, two experimental and two control groups, pretests for half of the groups, and posttests for all

- Testing effects- when a participant’s scores on a measure change because they have already been exposed to it

- True experiments- a group of experimental designs that contain independent and dependent variables, pretesting and post testing, and experimental and control groups

Image attributions

exam scientific experiment by mohamed_hassan CC-0

Foundations of Social Work Research Copyright © 2020 by Rebecca L. Mauldin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Extract insights from Interviews. At Scale.

Experimental vs. control group explained.

Home » Experimental vs. Control Group Explained

Group Comparison Analysis plays a pivotal role in experimental research. By examining the differences between experimental and control groups, researchers can draw meaningful conclusions about specific interventions. This process helps in determining whether observed effects are indeed attributable to the treatment or merely due to chance.

In any experiment, understanding how participants respond to different conditions is crucial. Group Comparison Analysis allows scientists to tease apart these responses, yielding insights that can inform various fields. Ultimately, this analytical approach not only enhances the validity of research findings but also supports the development of effective strategies based on empirical evidence.

The Basics of Experimental Groups

In research, understanding the distinction between experimental groups is essential for accurate findings. An experimental group consists of participants exposed to a variable being tested, while a control group serves as the baseline for comparison. This design enhances the reliability of results by isolating the effects of the independent variable. To conduct a thorough group comparison analysis, researchers need to ensure that both groups are similar in characteristics, minimizing biases.

The selection of participants plays a crucial role in the integrity of the study. Random assignment helps to ensure that individuals in both groups do not display pre-existing differences. This allows researchers to draw valid conclusions regarding the impact of the experimental treatment. Analyzing data from both groups provides insights into whether the intervention produces the expected changes. Effective comparison between these groups is foundational for advancing scientific knowledge. Understanding these basics will guide you through interpreting research outcomes with confidence.

Definition and Purpose

Understanding the experimental and control groups is essential in any Group Comparison Analysis. The experimental group receives the treatment or intervention, while the control group serves as a baseline for comparison. This structure is pivotal in determining the effectiveness of a given treatment and minimizes bias, ensuring the results are reliable.

The purpose of utilizing these groups lies in establishing a clear cause-and-effect relationship. By comparing outcomes from both groups, researchers can identify any significant differences attributable to the treatment. This comparison not only enhances the validity of findings but also influences data-driven decisions in various fields, including healthcare and marketing. Ultimately, the insight gained from this method fosters informed strategies that can lead to improved outcomes, whether in product development or user experience.

Designing an Experimental Group: Group Comparison Analysis

Designing an experimental group involves carefully planning each aspect to ensure valid results through group comparison analysis. This analysis is crucial for distinguishing the effects of a treatment or intervention from the natural variability found in any population. To effectively design your experimental group, you need to determine the characteristics that will make it comparable to the control group.

A proper comparison requires selection criteria such as age, gender, and baseline characteristics. This helps ensure that differences in outcomes arise solely from the intervention rather than from pre-existing variances. Next, consider randomization; randomly assigning participants reduces bias and enhances the study's reliability. Lastly, maintaining consistency in treatment delivery is essential. This ensures that everyone in the experimental group receives the same intervention, thus allowing for an accurate analysis of effects. By following these principles, your group comparison analysis can yield insightful and actionable outcomes.

The Role of Control Groups in Research

Control groups play a vital role in research by providing a benchmark to which experimental groups can be compared. Through group comparison analysis, researchers can discern the effects of an intervention by measuring outcomes against the control group that does not receive the treatment. This approach ensures that any observed changes in the experimental group can be more confidently attributed to the treatment rather than other external factors.

Moreover, control groups help minimize bias and variability in research outcomes. By allowing researchers to assess how participants behave under standard conditions, it becomes easier to isolate the impact of the experimental variable. Understanding these dynamics improves the reliability of results, making findings more valid and generalizable. Therefore, incorporating control groups in studies is essential for achieving accurate and trustworthy conclusions that can inform future practices or theories.

Definition and Purpose of Control Groups in Group Comparison Analysis

Control groups are essential in group comparison analysis, serving as benchmarks for experimental outcomes. These groups consist of participants who do not receive the treatment or intervention under investigation, allowing researchers to isolate the impact of specific variables. By comparing the results from the experimental group against the control group, researchers can determine the effectiveness of the intervention in a more precise manner.

The purpose of control groups is to minimize biases and ensure valid conclusions. They help in identifying whether observed changes in the experimental group are genuinely caused by the treatment or merely due to external factors. Additionally, control groups enable replication of studies, which is vital for affirming findings and fostering scientific credibility. In summary, control groups are indispensable tools in group comparison analysis, providing clarity and enhancing the reliability of research outcomes.

Examples of Control Group Usage

Control groups are essential in various fields, enabling researchers to validate their findings by providing a baseline for comparison. For instance, in a clinical trial assessing a new medication, one group receives the drug while a control group receives a placebo. This setup allows for a clearer understanding of the drug's effectiveness versus no treatment at all.

In market research, control groups allow analysts to examine consumer behavior under different conditions. A common example is testing two marketing strategies: one group receives traditional ads, while the control group is exposed to digital campaigns. Group comparison analysis reveals which method resonates better with the audience, helping to refine marketing approaches and optimize future campaigns. Through these examples, it's evident that control groups are invaluable in ensuring scientific rigor and making informed decisions across various domains.

Conclusion: The Importance of Group Comparison Analysis in Research

Group Comparison Analysis serves as a critical tool for researchers, allowing them to discern the differences between experimental and control groups. By methodically comparing these groups, researchers can assess the effectiveness of interventions or treatments. This type of analysis provides vital insights, facilitating a deeper understanding of how variables impact outcomes.

Furthermore, the importance of this analysis extends beyond mere statistical significance. It fosters evidence-based decision-making, ensuring that findings are reliable and applicable in real-world settings. Ultimately, understanding the dynamics between different groups equips researchers with the knowledge to make informed conclusions, driving advancements in various fields of study.

Turn interviews into actionable insights

On this Page

Random Sampling Definition in Research

You may also like, guide to designing a website user journey map.

7 Usability Testing Methods to Improve User Experience

Top 5 free ux research tools to use in 2024.

Unlock Insights from Interviews 10x faster

- Request demo

- Get started for free

What Is a Control Group?

- Chemical Laws

- Periodic Table

- Projects & Experiments

- Scientific Method

- Biochemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Medical Chemistry

- Chemistry In Everyday Life

- Famous Chemists

- Activities for Kids

- Abbreviations & Acronyms

- Weather & Climate

- Ph.D., Biomedical Sciences, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

- B.A., Physics and Mathematics, Hastings College

A control group in a scientific experiment is a group separated from the rest of the experiment, where the independent variable being tested cannot influence the results. This isolates the independent variable's effects on the experiment and can help rule out alternative explanations of the experimental results.

A control group definition can also be separated into two other types: positive or negative.

Positive control groups are groups where the conditions of the experiment are set to guarantee a positive result. A positive control group can show the experiment is functioning properly as planned.

Negative control groups are groups where the conditions of the experiment are set to cause a negative outcome.

Control groups are not necessary for all scientific experiments. Controls are extremely useful when the experimental conditions are complex and difficult to isolate.

Example of a Negative Control Group

Negative control groups are particularly common in science fair experiments , to teach students how to identify the independent variable . A simple example of a control group can be seen in an experiment in which the researcher tests whether or not a new fertilizer affects plant growth. The negative control group would be the plants grown without fertilizer but under the same conditions as the experimental group. The only difference between the experimental group would be whether or not the fertilizer was used.

Several experimental groups could differ in the fertilizer concentration, application method, etc. The null hypothesis would be that the fertilizer does not affect plant growth. Then, if a difference is seen in the growth rate or the height of plants over time, a strong correlation between fertilizer and growth would be established. Note the fertilizer could have a negative impact on growth rather than positive. Or, for some reason, the plants might not grow at all. The negative control group helps establish the experimental variable is the cause of atypical growth rather than some other (possibly unforeseen) variable.

Example of a Positive Control Group

A positive control demonstrates an experiment is capable of producing a positive result. For example, let's say you are examining bacterial susceptibility to a drug. You might use a positive control to make sure the growth medium is capable of supporting any bacteria. You could culture bacteria known to carry the drug resistance marker, so they should be capable of surviving on a drug-treated medium. If these bacteria grow, you have a positive control that shows other drug-resistant bacteria should be capable of surviving the test.

The experiment could also include a negative control. You could plate bacteria known not to carry a drug-resistant marker. These bacteria should be unable to grow on the drug-laced medium. If they do grow, you know there is a problem with the experiment .

- Understanding Experimental Groups

- The Difference Between Control Group and Experimental Group

- List of Platinum Group Metals or PGMs

- Scientific Hypothesis, Model, Theory, and Law

- What Is an Experiment? Definition and Design

- What Is a Base Metal? Definition and Examples

- What Is a Molecule?

- What Chemistry Is and What Chemists Do

- Acid Dissociation Constant Definition: Ka

- Fatty Acid Definition

- Dissolving Sugar in Water: Chemical or Physical Change?

- Hydroxyl Group Definition in Chemistry

- Heavy Metals in Science

- Is Glass a Liquid or a Solid?

- Examples of Independent and Dependent Variables

- Noble Metals List and Properties

- Science Notes Posts

- Contact Science Notes

- Todd Helmenstine Biography

- Anne Helmenstine Biography

- Free Printable Periodic Tables (PDF and PNG)

- Periodic Table Wallpapers

- Interactive Periodic Table

- Periodic Table Posters

- Science Experiments for Kids

- How to Grow Crystals

- Chemistry Projects

- Fire and Flames Projects

- Holiday Science

- Chemistry Problems With Answers

- Physics Problems

- Unit Conversion Example Problems

- Chemistry Worksheets

- Biology Worksheets

- Periodic Table Worksheets

- Physical Science Worksheets

- Science Lab Worksheets

- My Amazon Books

Control Group Definition and Examples

The control group is the set of subjects that does not receive the treatment in a study. In other words, it is the group where the independent variable is held constant. This is important because the control group is a baseline for measuring the effects of a treatment in an experiment or study. A controlled experiment is one which includes one or more control groups.

- The experimental group experiences a treatment or change in the independent variable. In contrast, the independent variable is constant in the control group.

- A control group is important because it allows meaningful comparison. The researcher compares the experimental group to it to assess whether or not there is a relationship between the independent and dependent variable and the magnitude of the effect.

- There are different types of control groups. A controlled experiment has one more control group.

Control Group vs Experimental Group

The only difference between the control group and experimental group is that subjects in the experimental group receive the treatment being studied, while participants in the control group do not. Otherwise, all other variables between the two groups are the same.

Control Group vs Control Variable

A control group is not the same thing as a control variable. A control variable or controlled variable is any factor that is held constant during an experiment. Examples of common control variables include temperature, duration, and sample size. The control variables are the same for both the control and experimental groups.

Types of Control Groups

There are different types of control groups:

- Placebo group : A placebo group receives a placebo , which is a fake treatment that resembles the treatment in every respect except for the active ingredient. Both the placebo and treatment may contain inactive ingredients that produce side effects. Without a placebo group, these effects might be attributed to the treatment.

- Positive control group : A positive control group has conditions that guarantee a positive test result. The positive control group demonstrates an experiment is capable of producing a positive result. Positive controls help researchers identify problems with an experiment.

- Negative control group : A negative control group consists of subjects that are not exposed to a treatment. For example, in an experiment looking at the effect of fertilizer on plant growth, the negative control group receives no fertilizer.

- Natural control group : A natural control group usually is a set of subjects who naturally differ from the experimental group. For example, if you compare the effects of a treatment on women who have had children, the natural control group includes women who have not had children. Non-smokers are a natural control group in comparison to smokers.

- Randomized control group : The subjects in a randomized control group are randomly selected from a larger pool of subjects. Often, subjects are randomly assigned to either the control or experimental group. Randomization reduces bias in an experiment. There are different methods of randomly assigning test subjects.

Control Group Examples

Here are some examples of different control groups in action:

Negative Control and Placebo Group

For example, consider a study of a new cancer drug. The experimental group receives the drug. The placebo group receives a placebo, which contains the same ingredients as the drug formulation, minus the active ingredient. The negative control group receives no treatment. The reason for including the negative group is because the placebo group experiences some level of placebo effect, which is a response to experiencing some form of false treatment.

Positive and Negative Controls

For example, consider an experiment looking at whether a new drug kills bacteria. The experimental group exposes bacterial cultures to the drug. If the group survives, the drug is ineffective. If the group dies, the drug is effective.

The positive control group has a culture of bacteria that carry a drug resistance gene. If the bacteria survive drug exposure (as intended), then it shows the growth medium and conditions allow bacterial growth. If the positive control group dies, it indicates a problem with the experimental conditions. A negative control group of bacteria lacking drug resistance should die. If the negative control group survives, something is wrong with the experimental conditions.

- Bailey, R. A. (2008). Design of Comparative Experiments . Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68357-9.

- Chaplin, S. (2006). “The placebo response: an important part of treatment”. Prescriber . 17 (5): 16–22. doi: 10.1002/psb.344

- Hinkelmann, Klaus; Kempthorne, Oscar (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume I: Introduction to Experimental Design (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-72756-9.

- Pithon, M.M. (2013). “Importance of the control group in scientific research.” Dental Press J Orthod . 18 (6):13-14. doi: 10.1590/s2176-94512013000600003

- Stigler, Stephen M. (1992). “A Historical View of Statistical Concepts in Psychology and Educational Research”. American Journal of Education . 101 (1): 60–70. doi: 10.1086/444032

Related Posts

Controlled Experiment

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

This is when a hypothesis is scientifically tested.

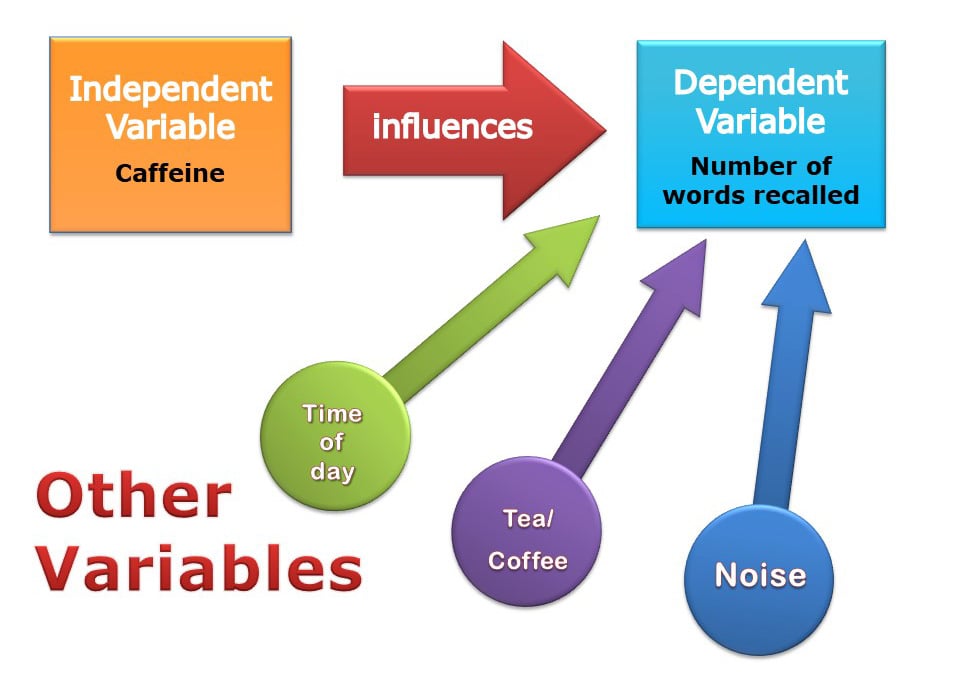

In a controlled experiment, an independent variable (the cause) is systematically manipulated, and the dependent variable (the effect) is measured; any extraneous variables are controlled.

The researcher can operationalize (i.e., define) the studied variables so they can be objectively measured. The quantitative data can be analyzed to see if there is a difference between the experimental and control groups.

What is the control group?

In experiments scientists compare a control group and an experimental group that are identical in all respects, except for one difference – experimental manipulation.

Unlike the experimental group, the control group is not exposed to the independent variable under investigation and so provides a baseline against which any changes in the experimental group can be compared.

Since experimental manipulation is the only difference between the experimental and control groups, we can be sure that any differences between the two are due to experimental manipulation rather than chance.

Randomly allocating participants to independent variable groups means that all participants should have an equal chance of participating in each condition.

The principle of random allocation is to avoid bias in how the experiment is carried out and limit the effects of participant variables.

What are extraneous variables?

The researcher wants to ensure that the manipulation of the independent variable has changed the changes in the dependent variable.

Hence, all the other variables that could affect the dependent variable to change must be controlled. These other variables are called extraneous or confounding variables.

Extraneous variables should be controlled were possible, as they might be important enough to provide alternative explanations for the effects.

In practice, it would be difficult to control all the variables in a child’s educational achievement. For example, it would be difficult to control variables that have happened in the past.

A researcher can only control the current environment of participants, such as time of day and noise levels.

Why conduct controlled experiments?

Scientists use controlled experiments because they allow for precise control of extraneous and independent variables. This allows a cause-and-effect relationship to be established.

Controlled experiments also follow a standardized step-by-step procedure. This makes it easy for another researcher to replicate the study.

Key Terminology

Experimental group.

The group being treated or otherwise manipulated for the sake of the experiment.

Control Group

They receive no treatment and are used as a comparison group.

Ecological validity

The degree to which an investigation represents real-life experiences.

Experimenter effects

These are the ways that the experimenter can accidentally influence the participant through their appearance or behavior.

Demand characteristics

The clues in an experiment lead the participants to think they know what the researcher is looking for (e.g., the experimenter’s body language).

Independent variable (IV)

The variable the experimenter manipulates (i.e., changes) – is assumed to have a direct effect on the dependent variable.

Dependent variable (DV)

Variable the experimenter measures. This is the outcome (i.e., the result) of a study.

Extraneous variables (EV)

All variables that are not independent variables but could affect the results (DV) of the experiment. Extraneous variables should be controlled where possible.

Confounding variables

Variable(s) that have affected the results (DV), apart from the IV. A confounding variable could be an extraneous variable that has not been controlled.

Random Allocation

Randomly allocating participants to independent variable conditions means that all participants should have an equal chance of participating in each condition.

Order effects

Changes in participants’ performance due to their repeating the same or similar test more than once. Examples of order effects include:

(i) practice effect: an improvement in performance on a task due to repetition, for example, because of familiarity with the task;

(ii) fatigue effect: a decrease in performance of a task due to repetition, for example, because of boredom or tiredness.

What is the control in an experiment?

In an experiment , the control is a standard or baseline group not exposed to the experimental treatment or manipulation. It serves as a comparison group to the experimental group, which does receive the treatment or manipulation.

The control group helps to account for other variables that might influence the outcome, allowing researchers to attribute differences in results more confidently to the experimental treatment.

Establishing a cause-and-effect relationship between the manipulated variable (independent variable) and the outcome (dependent variable) is critical in establishing a cause-and-effect relationship between the manipulated variable.

What is the purpose of controlling the environment when testing a hypothesis?

Controlling the environment when testing a hypothesis aims to eliminate or minimize the influence of extraneous variables. These variables other than the independent variable might affect the dependent variable, potentially confounding the results.

By controlling the environment, researchers can ensure that any observed changes in the dependent variable are likely due to the manipulation of the independent variable, not other factors.

This enhances the experiment’s validity, allowing for more accurate conclusions about cause-and-effect relationships.

It also improves the experiment’s replicability, meaning other researchers can repeat the experiment under the same conditions to verify the results.

Why are hypotheses important to controlled experiments?

Hypotheses are crucial to controlled experiments because they provide a clear focus and direction for the research. A hypothesis is a testable prediction about the relationship between variables.

It guides the design of the experiment, including what variables to manipulate (independent variables) and what outcomes to measure (dependent variables).

The experiment is then conducted to test the validity of the hypothesis. If the results align with the hypothesis, they provide evidence supporting it.

The hypothesis may be revised or rejected if the results do not align. Thus, hypotheses are central to the scientific method, driving the iterative inquiry, experimentation, and knowledge advancement process.

What is the experimental method?

The experimental method is a systematic approach in scientific research where an independent variable is manipulated to observe its effect on a dependent variable, under controlled conditions.

Frequently asked questions

What is the difference between a control group and an experimental group.

An experimental group, also known as a treatment group, receives the treatment whose effect researchers wish to study, whereas a control group does not. They should be identical in all other ways.

Frequently asked questions: Methodology

Attrition refers to participants leaving a study. It always happens to some extent—for example, in randomized controlled trials for medical research.

Differential attrition occurs when attrition or dropout rates differ systematically between the intervention and the control group . As a result, the characteristics of the participants who drop out differ from the characteristics of those who stay in the study. Because of this, study results may be biased .

Action research is conducted in order to solve a particular issue immediately, while case studies are often conducted over a longer period of time and focus more on observing and analyzing a particular ongoing phenomenon.

Action research is focused on solving a problem or informing individual and community-based knowledge in a way that impacts teaching, learning, and other related processes. It is less focused on contributing theoretical input, instead producing actionable input.

Action research is particularly popular with educators as a form of systematic inquiry because it prioritizes reflection and bridges the gap between theory and practice. Educators are able to simultaneously investigate an issue as they solve it, and the method is very iterative and flexible.

A cycle of inquiry is another name for action research . It is usually visualized in a spiral shape following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

To make quantitative observations , you need to use instruments that are capable of measuring the quantity you want to observe. For example, you might use a ruler to measure the length of an object or a thermometer to measure its temperature.

Criterion validity and construct validity are both types of measurement validity . In other words, they both show you how accurately a method measures something.

While construct validity is the degree to which a test or other measurement method measures what it claims to measure, criterion validity is the degree to which a test can predictively (in the future) or concurrently (in the present) measure something.

Construct validity is often considered the overarching type of measurement validity . You need to have face validity , content validity , and criterion validity in order to achieve construct validity.

Convergent validity and discriminant validity are both subtypes of construct validity . Together, they help you evaluate whether a test measures the concept it was designed to measure.

- Convergent validity indicates whether a test that is designed to measure a particular construct correlates with other tests that assess the same or similar construct.

- Discriminant validity indicates whether two tests that should not be highly related to each other are indeed not related. This type of validity is also called divergent validity .

You need to assess both in order to demonstrate construct validity. Neither one alone is sufficient for establishing construct validity.

- Discriminant validity indicates whether two tests that should not be highly related to each other are indeed not related

Content validity shows you how accurately a test or other measurement method taps into the various aspects of the specific construct you are researching.

In other words, it helps you answer the question: “does the test measure all aspects of the construct I want to measure?” If it does, then the test has high content validity.

The higher the content validity, the more accurate the measurement of the construct.

If the test fails to include parts of the construct, or irrelevant parts are included, the validity of the instrument is threatened, which brings your results into question.

Face validity and content validity are similar in that they both evaluate how suitable the content of a test is. The difference is that face validity is subjective, and assesses content at surface level.

When a test has strong face validity, anyone would agree that the test’s questions appear to measure what they are intended to measure.

For example, looking at a 4th grade math test consisting of problems in which students have to add and multiply, most people would agree that it has strong face validity (i.e., it looks like a math test).

On the other hand, content validity evaluates how well a test represents all the aspects of a topic. Assessing content validity is more systematic and relies on expert evaluation. of each question, analyzing whether each one covers the aspects that the test was designed to cover.

A 4th grade math test would have high content validity if it covered all the skills taught in that grade. Experts(in this case, math teachers), would have to evaluate the content validity by comparing the test to the learning objectives.

Snowball sampling is a non-probability sampling method . Unlike probability sampling (which involves some form of random selection ), the initial individuals selected to be studied are the ones who recruit new participants.

Because not every member of the target population has an equal chance of being recruited into the sample, selection in snowball sampling is non-random.

Snowball sampling is a non-probability sampling method , where there is not an equal chance for every member of the population to be included in the sample .

This means that you cannot use inferential statistics and make generalizations —often the goal of quantitative research . As such, a snowball sample is not representative of the target population and is usually a better fit for qualitative research .

Snowball sampling relies on the use of referrals. Here, the researcher recruits one or more initial participants, who then recruit the next ones.

Participants share similar characteristics and/or know each other. Because of this, not every member of the population has an equal chance of being included in the sample, giving rise to sampling bias .

Snowball sampling is best used in the following cases:

- If there is no sampling frame available (e.g., people with a rare disease)

- If the population of interest is hard to access or locate (e.g., people experiencing homelessness)

- If the research focuses on a sensitive topic (e.g., extramarital affairs)

The reproducibility and replicability of a study can be ensured by writing a transparent, detailed method section and using clear, unambiguous language.