Special Issue: Propaganda

This essay was published as part of the Special Issue “Propaganda Analysis Revisited”, guest-edited by Dr. A. J. Bauer (Assistant Professor, Department of Journalism and Creative Media, University of Alabama) and Dr. Anthony Nadler (Associate Professor, Department of Communication and Media Studies, Ursinus College).

Propaganda Analysis Revisited

This special issue is designed to place our contemporary post-truth impasse in historical perspective. Drawing comparisons to the Propaganda Analysis research paradigm of the Interwar years, this essay and issue call attention to historical similarities between patterns in mass communication research then and now. The hope is that contemporary misinformation studies scholars can learn from and avoid the pitfalls that have historically faced propaganda researchers. Placing research on propaganda in historical context offers one way of counterbalancing the depoliticizing tendencies that can be found in contemporary misinformation studies. It provides a wider field of vision, and calls attention to the contingency of the very concepts that social scientists use to frame their surveys and interviews, code their content, and ground their analysis.

Department of Journalism and Creative Media, University of Alabama, USA

Department of Communication and Media Studies, Ursinus College, USA

The long post-truth impasse

In 2016, the U.S. presidential and U.K. Brexit elections shook global confidence in a universally shared sense of objective reality and its capacity to serve as a basic standard of political judgment. Trump’s surprise victory, in particular, sparked panic among journalists, some of whom openly worried whether the press had been “mortally wounded” (Pilkington, 2016). That year, Oxford Dictionaries declared ‘post-truth’ — an adjective defined as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief” — as its word of the year (Oxford Languages, 2016).

While Oxford traces the term’s etymology back only to 1992, the conditions that ‘post-truth’ denotes have been a source of scholarly inquiry, media activism, and political struggle throughout the Twentieth Century and now well into the Twenty-First. Concerns over propaganda, and the public’s susceptibility to it, have been omnipresent in the U.S. and Europe since at least the Interwar Period and have played a crucial role in structuring the United States’ central ideological and partisan binary ever since (Gary, 1999; Bauer, 2017). They also played a foundational role in establishing the academic discipline of mass communication studies.

As historian J. Michael Sproule has shown, the propaganda anxieties that emerged in the aftermath of the First World War produced a fledgling scholarly paradigm known as Propaganda Analysis (Sproule, 1997). Between 1919 and 1937, an interdisciplinary array of humanists, educators, and social scientists produced countless studies focused on how to identify, understand, and defuse propaganda messages. This scholarly trend was bolstered by countless funders, and even supported by the then newly formed Social Science Research Council. It was also, Sproule contends, a fundamentally progressive endeavor — non-partisan, but driven by a “reform-minded probing into social institutions and persuasive campaigns to find whose interests were being advanced, how, and with what effect for society” (Sproule, 1987).

Propaganda Analysis faltered during the run-up to the Second World War. By the dawn of the Cold War, it had been eclipsed by a new communication research paradigm, typified by Paul Lazarsfeld’s more “limited” theory of media effects (Lazarsfeld et al., 1944). This new paradigm was focused less on the imperatives of social progress than on methodological sophistication and practical utility to government agencies and commercial interests. Propaganda Analysis lingered in the right anti-communist fringe, and among a tight-knit cadre of anti-capitalist activist scholars, but it became a marginal concern within the social sciences.

Like the Interwar years, our “post-truth era” has been a boon for scholars of propaganda, misinformation, and right-wing media around the globe, as funders and publishers rushed to fill perceived gaps in the scholarly literature. This has yielded a bumper crop of astute studies of our present political communication conjuncture. Research institutes such as Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, Columbia’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism, and the Data & Society Research Institute, have led the way in producing cutting-edge, solutions-driven scholarship with an eye toward practical applicability and public engagement.

Yet, some of the depoliticizing tendencies of the “communication research” paradigm linger. As Yochai Benkler and his colleagues noted in their pathbreaking study Network Propaganda , explanations for our current post-truth era have tended to foreground foreign subversion or technological determinist narratives — blaming Russian operatives, or Macedonian teenagers, or algorithms, or filter bubbles, or echo chambers (Benkler et al., 2018). When these phenomena are used to provide “nonpartisan explanations” for a surge in the spread of misinformation and the causes of the legitimacy crisis facing established news institutions, it obscures the political stakes of our present political communication impasse. Too much focus on technical fixes or on thwarting a narrowly defined set of “bad actors” blunts the imperative for civic engagement in crafting media policies and building media institutions to serve democratic needs (Pickard 2019; Crain & Nadler, 2019).

Historicizing propaganda research

Placing research on propaganda in historical context offers one way of counterbalancing the depoliticizing tendencies that can be found in contemporary misinformation studies. It provides a wider field of vision, and calls attention to the contingency of the very concepts that social scientists use to frame their interviews, code their content, and ground their analysis. Raymond Williams once lamented the tendency in social science to reduce systems to “fixed forms.” He astutely noted that social structures and processes only appear fixed artificially or in hindsight — social experiences are in fact lived “in solution” (Williams, 1977, p. 133).

Historical analysis can provide context that demonstrates how apparently coherent social processes — which are sometimes fixed in concepts like “propaganda,” “misinformation,” “echo chambers,” “the news ecosystem,” or even “journalism” — are dynamic, shaped in dialogue with broader political common sense and its path determined by established understandings of prior historical phenomena (Bauer, 2018; Nadler, 2019). Historical analysis, as applied to misinformation studies, need not be reduced to any one method — it may rely upon archival research, but it need not be confined to it. Comparative historical analysis invites a reflexive dialogue between how a phenomenon has been characterized in past iterations (based upon comparable prior examples) and how it is experienced in a given historical conjuncture.

This raises the question: How do misinformation studies of today relate to the propaganda studies of the Interwar era and of the latter Twentieth Century? The authors in this issue make a case for the history of propaganda research as something more than an antiquarian curiosity. History cannot provide easy answers to present questions or solve our contemporary dilemmas. But it can illuminate some of the particularity of present assumptions and might help to recover ideas and frameworks that could prove productive today. For instance, in the years following the Second World War, researchers including Löwenthal and Guterman (1949) and Adorno (1951) articulated a framework for propaganda research that connected the potential power of propaganda within a historical moment to the emotional longings cultivated by prevailing social conditions. Reexamining this approach might push current misinformation scholars to consider a broader array of models for explaining the “pull” factors in the popular uptake of misinformation. Instead of only looking at supposedly universal cognitive tendencies like confirmation bias, which have been at the forefront of contemporary research, revisiting thinkers like Löwenthal, Gutman, and Adorno could inspire more investigation of socially conditioned dispositions that might shape the demand-side of propaganda.

Just as important as rediscovering productive concepts that have been forgotten, rigorous historical examination forces us to scrutinize familiar tales about the past that are folded into contemporary self-understandings. Some fields burnish a flattering image of past contributions to cast a positive light on present-day inheritors. This is not the dominant trend in the field of misinformation studies, which has largely distanced itself from the history of propaganda research rather than claiming it as a legacy. Certainly, there are some compelling reasons for the field’s name change, including a sense that “misinformation” covers a wider object of analysis than does “propaganda.” But misinformation studies scholars will do themselves no favors if they remember only a caricature of propaganda research so as to inflate the new field’s confidence in overcoming the narrow-minded blunders of its predecessors. For example, that earlier propaganda researchers tended to rely on their own sensibilities to intuitively identify their objects of analysis (Bauer, 2017, 2018; Anderson, this issue) might be recognized as not only a cautionary tale, but as an ongoing tension in contemporary research.

One distorted memory of propaganda research that has been especially influential in the field of communication — and remains prevalent today, despite repeated debunking — is that such research figured ordinary people as gullible dupes and presented media influence as a “magic bullet.” This rendering served as a straw figure, designed to promote a more positivistic approach to studying media influence and which raised fewer ethical questions that could nettle the institutions that helped fund the ascendant communication research paradigm (Sproule 1989; Lubken 2008). Writing off earlier propaganda research as misguided by a fundamental error — one betraying elitist prejudice — diminished scholarly engagement with the complicated questions this earlier discourse raised.

As several of the contributors in this issue argue (see especially works by Jeffrey Pooley and Victor Pickard), communication research turned away from squarely facing the normative questions this research started to raise, especially regarding the structural — and political — underpinnings of media systems that created conditions ripe for propaganda. Reconsidering the history of this research in light of our contemporary post-truth impasse can bring new life to the normative questions and debates that had been kept shuttered away from institutionally funded media research.

Our point of departure, Interwar Propaganda Analysis in the United States and Europe, offers but one vantage into the long and variegated history of propaganda research — a limiting one, at that. It foregrounds the experiences and concerns of the Global North. While these contexts played an outsized role in the development of mass communication studies around the world, they have often failed to address or adequately explain propaganda in the Global South, as issue contributor Aman Abhishek deftly illustrates. U.S.-based Propaganda Analysis also tends to de-emphasize state-oriented solutions to dis- and misinformation (like those explored in this issue by Sonia Robles) — a relic not only of general U.S. anti-statism, but of the field’s roots in opposition to the abuses of the Woodrow Wilson administration’s Committee on Public Information during the First World War.

The history of propaganda research, like that of propaganda itself, is vexed, non-linear, and over-determined. For this issue, we’ve selected case studies designed to illuminate research trajectories and counter-propaganda methods that resonate with challenges faced in our contemporary situation of post-truth impasse/global pandemic. Most of these studies offer visions of paths untaken or foreclosed, of approaches marginalized or diminished. Our hope is that scholars of contemporary dis- and misinformation will consider their work in relation to this long tradition of propaganda scholarship, to recognize it as a site of struggle with lessons for the present.

- / Propaganda

Cite this Essay

Bauer, A. J., & Nadler, A. M. (2021). Propaganda Analysis Revisited. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review .

Bibliography

Adorno, T. W. (1951). Freudian theory and the pattern of Fascist propaganda. In J. M. Bernstein (Ed.). The culture industry: Selected essays on mass culture (2nd ed., 2001). Routledge.

Bauer, A. J. (2017). Before ‘fair and balanced’: Conservative media activism and the rise of the New Right [Unpublished dissertation]. New York University.

Bauer, A. J. (2018). Journalism History and Conservative Erasure. American Journalism 35 (1), 2-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/08821127.2017.1419750

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics . Oxford University Press.

Crain, M., & Nadler, A. (2019). Political manipulation and internet advertising infrastructure. Journal of Information Policy, 9, 370–410. https://doi.org/10.5325/jinfopoli.9.2019.0370

Gary, B. (1999). The nervous liberals: Propaganda anxieties from World War I to the Cold War . Columbia University Press.

Lazarsfeld, P. F., Berelson, B., & Gaudet, H. (1944). The people’s choice: How the voter makes up his mind in a Presidential campaign . Columbia University Press.

Löwenthal, L., & Guterman, N. (1949). Prophets of deceit: A study of the techniques of the American agitator . Harper & Brothers.

Lubken, D. (2008). Remembering the straw man: The travels and adventures of hypodermic. In D. W. Park & J. Pooley (Eds.), The history of media and communication research: Contested memories . Peter Lang.

Nadler, A. M. (2019). Nature’s economy and news ecology. Journalism Studies, 20 (6), 823–839. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1427000

Oxford Languages. (2016). Word of the year 2016 . Oxford University Press. https://languages.oup.com/word-of-the-year/2016/

Pickard, V. W. (2019). Democracy without journalism? Confronting the misinformation society . Oxford University Press.

Pilkington, E. (2016). Did Trump’s scorched-earth tactics mortally wound the media? Columbia Journalism Review . https://www.cjr.org/special_report/trumps_tactics_wound_the_media.php

Sproule, J. M. (1987) Propaganda studies in American social science: The rise and fall of the critical paradigm. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 73 , 60–78, 67. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335638709383794

Sproule, J. M. (1989). Progressive propaganda critics and the magic bullet myth. Critical Studies in Media Communication , 6 (3), 225–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295038909366750

Sproule, J. M. (1997). Propaganda and democracy: The American experience of media and mass persuasion . Cambridge University Press.

Williams, R. (1977). Structures of feeling. In Marxism and literature (pp. 128–135). Oxford University Press.

Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda? Analyzing World War II Posters

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

In this lesson plan, students analyze World War II posters, chosen from online collections, to explore how argument, persuasion and propaganda differ. The lesson begins with a full-class exploration of the famous "I WANT YOU FOR U.S. ARMY" poster, wherein students explore the similarities and differences between argument, persuasion, and propaganda and apply one of the genres to the poster. Students then work independently to complete an online analysis of another poster and submit either an analysis worksheet or use their worksheet responses to write a more formal essay.

Featured Resources

- Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda? : This handout clarifies the goals, techniques, and methods used in the genres of argument, persuasion, and propaganda.

- Analyzing a World War II Poster : This interactive assists students in careful analysis of a World War II poster of their own selection for its use of argument, persuasion, or propaganda.

From Theory to Practice

Visual texts are the focus of this lesson, which combines more traditional document analysis questions with an exploration of World War II posters. The 1975 "Resolution on Promoting Media Literacy" states that explorations of such multimodal messages "enable students to deal constructively with complex new modes of delivering information, new multisensory tactics for persuasion, and new technology-based art forms." The 2003 "Resolution on Composing with Nonprint Media" reminds us that "Today our students are living in a world that is increasingly non-printcentric. New media such as the Internet, MP3 files, and video are transforming the communication experiences of young people outside of school. Young people are composing in nonprint media that can include any combination of visual art, motion (video and film), graphics, text, and sound-all of which are frequently written and read in nonlinear fashion." To support the literacy skills that students must sharpen to navigate these many media, activities such as the poster analysis in this lesson plan provide bridging opportunities between traditional understandings of genre and visual representations. Further Reading

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 3. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- 4. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.

- 5. Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes.

- 11. Students participate as knowledgeable, reflective, creative, and critical members of a variety of literacy communities.

- 12. Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

- Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda?

- Document Analysis for Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda

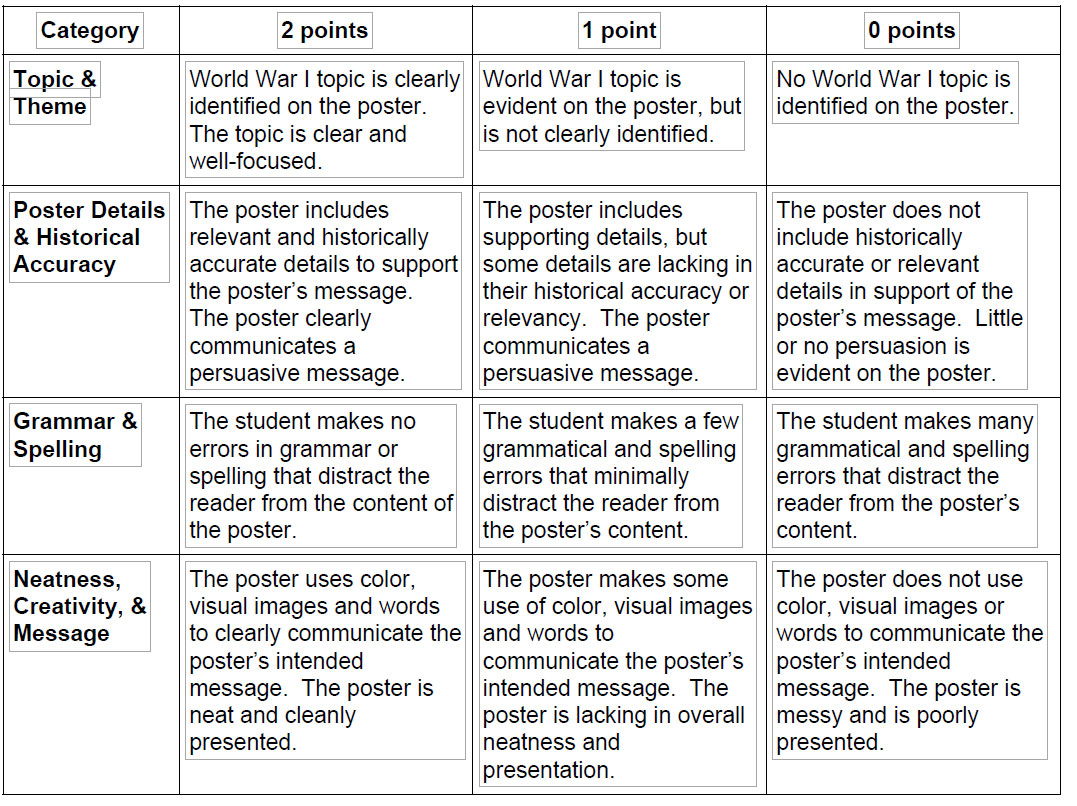

- Poster Analysis Rubric

Preparation

- Make appropriate copies of Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda? , Document Analysis for Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda , and Poster Analysis Rubric .

- Explore the background information on the Uncle Sam recruiting poster , so that you are prepared to share relevant historical details about the poster with students.

- If desired, explore the online poster collections and choose a specific poster or posters for students to analyze. If you choose to limit the options, post the choices on the board or on white paper for students to refer to in Session Two .

- Decide what final product students will submit for this lesson. Students can submit their analysis printout from the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive, or they can write essays that explain their analysis. If students write essays, the printouts from the interactive serve as prewriting and preparation for the longer, more formal piece.

- Test the Analyzing a Visual Message interactive and the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive on your computers to familiarize yourself with the tools and ensure that you have the Flash plug-in installed. You can download the plug-in from the technical support page.

Student Objectives

Students will

- discuss the differences between argument, persuasion, and propaganda.

- analyze visual texts individually, in small groups, and as a whole class.

- (optionally) write an analytical essay.

Session One

- Display the Uncle Sam recruiting poster using an overhead projector.

- Ask students to share what they know about the poster, noting their responses on the board or on chart paper.

- If students have not volunteered the information, provide some basic background information .

- Working in small groups, have students use the Analyzing a Visual Message interactive to analyze the Uncle Sam poster.

- Emphasize that students should use complete, clear sentences in their responses. The printout that the interactive creates will not include the questions, so students responses must provide the context. Be sure to connect the requirement for complete sentences to the reason for the requirement (so that students will understand the information on the printout without having to return to the Analyzing a Visual Message interactive.

- As students work, encourage them to look for concrete details in the poster that support their statements.

- Circulate among students as they work, providing support and feedback.

- Once students have completed the questions included in the Analyzing a Visual Message interactive, display the poster again and ask students to share their observations and analyses.

- Emphasize and support responses that will tie to the next session, where students will complete an independent analysis.

- Pass out and go over copies of the Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda Chart .

- Ask students to apply genre descriptions to the Uncle Sam poster, using the basic details they gathered in their analysis to identify the poster's genre.

Session Two

- Review the Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda? chart.

- Elicit examples of argument, persuasion, and propaganda from the students, asking them to provide supporting details that confirm the genres of the examples. Provide time for students to explore some of the Websites in the Resources section to explore the three concepts.

- When you feel that the students are comfortable with the similarities and differences of the three genres, explain to the class that they are going to be choosing and analyzing World War II posters for a more detailed analysis.

- Pass out the Document Analysis for Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda , and go over the questions in the analysis sheet. Draw connections between the questions and what the related answers will reveal about a document's genre.

- Demonstrate the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive.

- Point out the connections between the questions in the interactive and the questions listed on the Document Analysis for Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda .

- If students need additional practice with analysis, choose a poster and use the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive to work through all the analysis questions as a whole class.

- Explain the final format that students will use for their analysis—you can have students submit their analysis printout from the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive, or they can submit polished essays that explain their analysis.

- Pass out copies of the Poster Analysis Rubric , and explain the expectations for the project.

- Posters on the American Home Front (1941-45), from the Smithsonian Institute

- Powers of Persuasion, from the National Archives

- World War II Poster Collection, from Northwestern University

- World War II Posters, from University of North Texas Libraries

Session Three

- Review the poster analysis project and the handouts from previous session.

- Answer any questions about the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive then give students the entire class session to work through their analysis.

- Remind students to refer to the Poster Analysis Rubric to check their work before saving or printing their work.

- If you are having students submit their printouts for the final project, collect their work at the end of the session. Otherwise, if you have asked students to write the essay, ask them to use their printout to write the essay for homework. Collect the essays and printouts at the beginning of the next session (or when desired).

- If desired, students might share the posters they have chosen and their conclusions with the whole class or in small groups.

The Propaganda Techniques in Literature and Online Political Ads lesson plan offers additional information about propaganda as well as some good Websites on propaganda.

Student Assessment / Reflections

Use the Poster Analysis Rubric to evaluate and give feedback on students’ work. If students have written a more formal paper, you might provide additional guidelines for standard written essays, as typically used in your class.

- Calendar Activities

- Professional Library

- Strategy Guides

- Lesson Plans

This resolution discusses that understanding the new media and using them constructively and creatively actually requires developing a new form of literacy and new critical abilities "in reading, listening, viewing, and thinking."

This strategy guide clarifies the difference between persuasion and argumentation, stressing the connection between close reading of text to gather evidence and formation of a strong argumentative claim about text.

Add new comment

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

Self-Paced Courses : Explore American history with top historians at your own time and pace!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

World War II Posters and Propaganda

By tim bailey.

Click here to download this four-lesson unit.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

- Digital Images

- Current Exhibits

- Past Exhibits

- Nabb Center Website

The ABCs of Propaganda Analysis

Founded in 1937, the New York-based Institute for Propaganda Analysis (IPA) created materials and teaching methods to help educators and the public detect, recognize, and analyze propaganda. As part of their curriculum, they created the ABCs of Propaganda Analysis, which remains a relevant guide to examining current forms of propaganda.

ASCERTAIN the conflict element in the propaganda you are analyzing.

BEHOLD your own reaction to this conflict element.

CONCERN yourself with today’s propaganda associated with today’s conflicts.

DOUBT that your opinions are “your very own.”

EVALUATE, therefore, with the greatest care, your own propagandas.

FIND THE FACTS before you come to any conclusion.

GUARD always, finally, against omnibus words.

Don’t Be a Sucker, 1943, clip from the film created by the US Department of War

- UNC Libraries

- Course Guides

- English 105 Online Curriculum Module: Rhetoric of American World War I Posters

English 105 Online Curriculum Module: Rhetoric of American World War I Posters: Home

Unit project, lesson context.

The Rhetoric of American World War I Propaganda Posters unit sequence uses primary sources to introduce students to the basics of rhetorical and visual analysis, multimodal composition, and scholarly research and writing. The unit begins with students exploring “ North Carolinians and the Great War ,” the library’s digital collection of World War I posters. In the first feeder assignment, students complete a visual analysis worksheet and analyze the rhetoric and imagery of two posters from the collection. Students can also watch "Analyzing World War I Posters," a short video introduction to visual analysis and the history of World War I posters. In the second feeder assignment, students expand their rhetorical analysis by conducting additional secondary source research about one of the posters. Finally, in the unit project, students write an analysis of their poster and share their findings with the class in a five-minute conference presentation.

- Unit Summary - Printable PDF

Unit Summary

| Genre | Purpose | Audience | Author | Rhetorical Situation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conference presentation (oral-visual). | To analyze WWI posters in order to explain how war propaganda works. | Other academics who are attending the WWI conference. | Rhetorician who studies visual propaganda. | You’ve been selected to present your work on WWI propaganda posters at the Cultural Legacies of World War I conference. |

Assignments

You have been selected to present at a World War I conference. Your research begins with the library’s online collection of the many American propaganda posters created during World War I to recruit soldiers and build national pride. This digital collection, “North Carolinians and the Great War,” focuses specifically on posters that would have been widely distributed in North Carolina to help bolster war efforts in the state. In this unit, you will select one poster to study, analyze, research, and write about. You deliverables include a brief visual presentation about your poster and an essay. As a rhetorician, your goal is to analyze the rhetorical strategies the artist used to create an effective propaganda poster. You should consider include how the artist used images, color, text, and design elements to convey messages related to World War I. Additionally, you should explore the historical context of your poster and how it might have influenced North Carolinians who participated in the war efforts.

Learning Objectives

By working on the feeder assignments and unit project, you will develop the following skills:

identify how rhetorical strategies are deployed in both visual and textual formats;

conduct secondary source research;

place propaganda rhetoric in its historical context; and

synthesize complex research findings in a compelling oral presentation and written assignment.

North Carolinians and the Great War

World War I propaganda posters are available from Documenting the American South (DocSouth). The goal of the poster collection is to “[examine] how World War I shaped the lives of different North Carolinians on the battlefield and on the home front as well how the state and federal government responded to war-time demands."

- Video: Analyzing World War I Posters This video provides a guide to visual analysis an examples of how to apply analytical questions to WWI posters within their historical context.

- World War I Posters Worksheet This worksheet accompanies the video "Analyzing World War I Posters."

- An introduction to the collection This introduction to the poster collection places the posters in historical context and describes the collection.

- Propaganda posters organized by theme All of the posters are accessible here and organized by topic.

In Feeder One, students will begin by exploring the online collection of American World War I propaganda posters to get a sense of the range and types of posters that were made. Either as an in-class activity or as a homework assignment, students should select a poster they find interesting and analyze it more closely by completing the Visual Analysis Worksheet .

Once students have practiced their visual analysis skills, they can move on to the second part of the feeder assignment. First, they should select and download two posters they are interested in writing about for their final projects. Next, they should write a short paragraph about each poster that includes the following information:

- their reasons for selecting the poster, such as its color, shape, subject matter, artistic appeal, etc.;

- the message (or messages) they believe the poster was expressing; and

- the historical audience (or audiences) they believe the poster and message were trying to reach.

Instructional Materials

- Visual Analysis Worksheet - Printable PDF

For Feeder Two, Background Research and Preliminary Analysis , students will choose one poster and examine it from multiple critical vantage points. First, in the research phase of the assignment, students will search for secondary and primary sources that answer key questions about their posters. Their driving goal as researchers in this assignment will be to learn more about the historical and cultural context in which their posters were created and disseminated.

Next, in the rhetorical analysis phase of the assignment, students will use the information they have gained and their own visual and textual analysis skills to draw conclusions about their posters. They will consider questions about the intended audience and purpose of their posters, as well as considering how persuasive techniques are deployed to connect with that audience and achieve that particular purpose.

- Background Research and Preliminary Analysis - Printable PDF

Possible Expansion: Visit the Undergraduate Library

Request an information literacy instruction session taught by librarians at the Robert B. House Undergraduate Library (UL). In this session, librarians can help connect students with library resources and search strategies to support their background research on their posters. Potential topics may include formulating keywords, searching in databases, evaluating print and online sources, citation, and other information literacy concepts.

For the Unit Project, an Essay and Conference Presentation , students will build on their prior research and thinking from Feeders One and Two by connecting their historical research with their rhetorical analysis. They will consider how the historical events and cultural norms of the time contributed to the visual and textual rhetorical strategies being used in the poster.

Playing the role of participants in a special session at the World War I conference, students will deliver a brief in-class presentation about the propaganda strategies used in their posters. They will also contribute an accompanying essay about their poster to the special issue of a journal published in conjunction with the conference.

- Essay and Conference Presentation - Printable PDF

Additional Resources

These resources may supplement the instructional materials provided above:

Presentations

- Design Guide: Presentation Slides (UL)

- Presentation Planning Worksheet (UL Design Guide)

- Powerpoint and Google Slides Templates (Slides Carnival)

Public Speaking

- Tips and Tools Handout: Speeches (UNC Writing Center)

- Public Speaking Foundations (Lynda.com Tutorial)

Michael Keenan Gutierrez

Teaching Assistant Professor, Department of English and Comparative Literature

Emily Kader

Rare Book Research Librarian, Wilson Special Collections Library

Cait Kennedy

Carolina Academic Library Associate

Ashley Werlinich

Graduate Research Assistant, Wilson Special Collections Library; Ph.D. Student and Teaching Fellow, Department of English and Comparative Literature

Discipline Areas

This online curriculum module is designed for use in the humanities unit of English 105; however, it could also be adapted for English 105i: Writing in the Humanities or Writing in the Digital Humanities.

English 105 Requirements

This unit sequence meets the following English 105 requirements:

- Digital Literacy;

- Information Literacy;

- Multimodal Composition;

- Oral Presentation;

- Primary Source Literacy; and

- Visual Literacy.

Possible Adaptations

This unit sequence could be adapted to use a variety of other special collections materials, depending on your research interests, desired learning outcomes, and other instructional goals. Contact the Special Collections to discuss other possible adaptations.

Instruction

Schedule an instruction session.

If you would like your class to visit Wilson Special Collections Library, request a special collections instruction session .

Teach with the Rare Book Collection

If you have questions about teaching with primary sources, contact Emily Kader .

Visit the Special Collections Research Room or contact the special collections .

Share Your Feedback

Instructor check-in.

Let us know when and how you're using materials from the Rhetoric of American World War I Posters online curriculum module by filling out this brief survey !

Instructor Survey

Do you have ideas for how this content could be expanded or improved? Share your feedback and ideas by filling out this survey .

Student Survey

Ask your students to share their experiences with the Rhetoric of American World War I Posters online curriculum module by completing this survey .

Start a Conversation

To start a conversation about how future online curriculum modules can support your English 105 instruction, contact Jason Tomberlin , Head of Research and Instructional Services.

- Last Updated: May 6, 2022 1:53 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/world-war-one-posters

Log In | Register

- Plan A Visit

- The Arsenal of Democracy

- Live Shows at BB's Stage Door Canteen

- Dining — The American Sector and Soda Shop

- Museum Campus

- Beyond All Boundaries

- Give to the Museum

- Capital Expansion

- Become A Member

- Name A Theater Seat

- Planned Giving

- Donate A Vehicle

- Donate An Artifact

- Corporate Sponsorships

- Donor Privacy Policy

- Honor Roll of Charter Members

- Brick Program

- Personal Tribute Pages

- Tribute Gifts

- $10 for Them

- Research A Veteran

- WWII Veteran Statistics

- Teachers & Students

- Public Programming

- Educational Travel

- Knit Your Bit

- Educational WWII Wargaming

- International Conference on WWII

- Speakers Bureau

- Family Activities

- Museum Blog

- Digital Collections

- WWII Yearbooks

- The Science & Technology of WWII

- The Classroom Victory Garden Project

- Kids Corner

- Past Speakers Archive

- Campaigns of Courage

- Liberation Pavilion

- Capital Campaign Donors

LESSON PLAN:

Winning over hearts and minds: analyzing wwii propaganda posters.

Propaganda played a key part in the United States’ war effort. Although much more subtle, propaganda was as much a weapon of the war as manpower and ammunition. In addition to the radio broadcasts, movies, and comic books, over 200,000 poster designs were produced during WWII by the Office of War Information (OWI), The Treasury Department, branches of the armed force, and recruitment bureaus. These groups used many propaganda types (fear, bandwagon, etc.) and many themes (conservation, recruitment, etc.) to win over the hearts and minds of Americans.

Objective: By examining propaganda posters from WWII students will increase their knowledge of propaganda tools and develop an understanding of the specific goals and strategies used by the U.S. government and OWI during WWII.

Grade Level: 7-12

Standards: History Thinking Standard 2—the student comprehends a variety of historical sources and appreciates historical perspectives as revealed through the arts.

Content Era 8 (1929-1945) Standard 3C—the student understands the effects of the war at home.

Time Requirement: One class period.

Download a printable pdf version of this lesson plan

Directions:

1. Distribute the following to students:

- Types of Propaganda Sheet

- Poster Analysis Sheet

- Student Worksheets

2. Using the "Types of Propaganda” sheet and the Propaganda Fact Sheet, have a brief discussion of the different types of propaganda. Make sure students are clear in their understanding of the types of propaganda before they begin their individual work.

3. Have students first complete the worksheets and then the poster analysis.

4. As a class, go over the gallery of posters and the analysis questions. Discuss any additional questions students may have about propaganda, the posters, or WWII.

Assessment:

Assessment will include class discussion, completed worksheet, and poster analysis questions.

Enrichment:

Have students create a WWII era Propaganda Poster or a poster for a current social/political issue. Students may also write a research paper on WWII Propaganda or research WWII posters further and give a presentation to the class.

Poster Gallery for Discussion:

Directions: After choosing a poster, examine it carefully and answer the following questions.

1. For whom is this poster intended?

2. What is the poster trying to get the audience to do?

3. What is the theme of the poster?

4. What symbols, key words or well known images are used?

5. Is the use of the symbol/image/word successful?

6. What is the emotion conveyed by the poster?

7. How would you change the image to make it more powerful?

8. What type of propaganda does the poster use?

9. How successful do you think this poster was during WWII?

10. Would a similar image have the same impact in today’s society? Why or why not?

About the Posters

Poster One—(Bandwagon): The poster encourages everyone join the war effort-to build arms for victory.

Poster Two—(Fear): The poster shows children in the shadow of the Nazis. If you do not buy war bonds-the Nazis will come for your children (fear).

Poster Three—Euphemism and Fear: The poster shows a sailor dead on the beach-but his death is called a “loss.” The poster also uses fear as a motivator for not speaking out of turn.

Poster Four—Glittering Generalities: The poster shows a women canning food and supporting rationing. It is “patriotic” to do these things (it is a glittering generality because patriotic means different things to different people).

Poster Five—Transfer: The poster shows men fighting in the American Revolution and WWII. If you believe that the Revolutionary War was necessary (for liberty) then of course you should fight in this war (for liberty). The poster transfers the importance of and reason for the American Revolution to WWII.

Poster Six—Testimonial: The poster shows Santa telling everyone to buy war bonds. There are few more recognizable images then Santa. Children and adults would have recognized the image.

Back to Main

TAKE ACTION:

Education projects:.

- ABOUT THE MUSEUM

- SPECIAL EVENTS

- PRIVACY POLICY

The National WWII Museum tells the story of the American Experience in the war that changed the world - why it was fought, how it was won, and what it means today - so that all generations will understand the price of freedom and be inspired by what they learn.

Sign up for updates about exhibits, public programming and other news from The National WWII Museum here.

945 Magazine Street New Orleans, LA 70130, Entrance on Andrew Higgins Drive PHONE: (504) 528-1944 - FAX: (504) 527-6088 - EMAIL: [email protected] | Directions

Lessons of Liberty: Patriotism - Analyze WWI Propaganda Posters

This lesson plan asks students to examine their understanding of "patriotism" by analyzing over 60 primary source propaganda posters that called America to action during World War I.

Resource Links

Propaganda: What's the Message?

Lesson plan.

Examine the seven forms of propaganda found in advertising and politics. Discover the persuasive methods behind the messaging we see every day and gain skills to effectively identify and counter them. A classroom gallery walk challenges students to detect the propaganda techniques at work and evaluate their effectiveness.

Got a 1:1 classroom? Download fillable PDF versions of this lesson's materials below!

Pedagogy Tags

Teacher Resources

Get access to lesson plans, teacher guides, student handouts, and other teaching materials.

- Propaganda_Lesson Plan.pdf

- Propaganda_StudentDocs.pdf

- Propaganda_Fillable.zip

- Gallery Walk.pdf

I find the materials so engaging, relevant, and easy to understand – I now use iCivics as a central resource, and use the textbook as a supplemental tool. The games are invaluable for applying the concepts we learn in class. My seniors LOVE iCivics.

Lynna Landry , AP US History & Government / Economics Teacher and Department Chair, California

Related Resources

Ethel payne: first lady of the black press.

Interest Groups

NewsFeed Defenders

NewsFeed Defenders Extension Pack

Rachel Carson’s Fight for the Environment

The public sphere, the role of media.

See how it all fits together!

- An Ordinary Man, His Extraordinary Journey

- Hours/Admission

- Nearby Dining and Lodging

- Information

- Library Collections

- Online Collections

- Photographs

- Harry S. Truman Papers

- Federal Records

- Personal Papers

- Appointment Calendar

- Audiovisual Materials Collection

- President Harry S. Truman's Cabinet

- President Harry S. Truman's White House Staff

- Researching Our Holdings

- Collection Policy and Donating Materials

- Truman Family Genealogy

- To Secure These Rights

- Freedom to Serve

- Events and Programs

- Featured programs

- Civics for All of US

- Civil Rights Teacher Workshop

- High School Trivia Contest

- Teacher Lesson Plans

- Truman Library Teacher Conference 2024

- National History Day

- Student Resources

- Truman Library Teachers Conference

- Truman Presidential Inquiries

- Student Research File

- The Truman Footlocker Project

- Truman Trivia

- The White House Decision Center

- Three Branches of Government

- Electing Our Presidents Teacher Workshop

- National History Day Workshops from the National Archives

- Research grants

- Truman Library History

- Contact Staff

- Volunteer Program

- Internships

- Educational Resources

You're the Author: WWI Propaganda Creation Project

In this lesson, students will view a variety of examples of WWI propaganda posters and discuss their message and why they were important for the war effort. After the discussion, students will create their own examples of WWI propaganda posters.

To inform students why WWI propaganda posters were so effective and important for the war effort.

- Define the concept of propaganda.

- Explain why the use of propaganda was of particular significance during this time period.

- Evaluate the different strategies and tools used in the creation of propaganda.

- Demonstrate their knowledge of propaganda characteristics, strategies, and tools by creating their own piece of propaganda.

- 9-12.AH.3.CC.B - Evaluate the motivations for United States’ entry into WWI.

- 9-12.AH.3.PC.D - Assess the impact of WWI related events, on the formation of “patriotic” groups, pacifist organizations, and the struggles for and against racial equality, and diverging women’s roles in the United States.

WWI Propaganda posters - examples can be found at http://www.ww1propaganda.com/ , http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/wwipos/background.html , http://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object-groups/women-in-wwi/war-posters , and other various internet and print sources

DAY 1 Students will walk into the classroom that has various examples of WWI propaganda posters (see primary sources above) on the walls. Students will walk around the classroom examining the posters and write quick notes about the posters. Students will pay close attention to:

- Message/theme

- Effectiveness

- Author/organization

After students have had time to examine the posters, the class will discuss propaganda What does propaganda mean? Propaganda is information that is spread for the purpose of promoting a cause or belief. During WWI, posters were used to

- Recruit men to join the army

- Recruit women to work in the factories and in the Women’s Land Army

- Encourage people to save food and not to waste it

- Keep morale high and encourage people to buy government bonds

Why were propaganda posters needed during WWI? Countries only had small standing, professional armies at the start of the war They desperately needed men to join up and fight Most people did not own radios and TVs had not yet been invented The easiest way for the government to communicate with the people was through posters stuck on walls in all the towns and cities How were men encouraged to join the army? Men were made to feel unmanly and cowardly for staying at home How were women used to encourage men to join the army? Women were encouraged to pressurise their husbands, boyfriends, sons, and brothers to join up How was fear used? Some posters tried to motivate men to join up through fear Posters showed the atrocities that the Germans were said to be committing in France and Belgium People were encouraged to fear that unless they were stopped, the Germans would invade Britain and commit atrocities against their families How were women encouraged to work in the factories or to join the army or the land girls? When the men joined the war, the women were needed to do their jobs There was a massive need for women in the factories, to produce the weapons, ammunition and uniforms needed for the soldiers There was a major food shortage and women were desperately needed to grow food for the people of Britain and the soldiers in France Posters encouraged everyone to do their bit Through joining up Through working for the war effort By not wasting food Through investing in government bonds Why are WWI propaganda posters important? For historians today, propaganda posters of WWI reveal the values and attitudes of the people at the time They tell us something about the feelings in Britain during WWI Class will discuss the assignment (poster creation) Students will begin brainstorming ideas for their own propaganda posters in small groups Students will begin creating their propaganda posters

DAY 2 Students will continue working to create their propaganda posters

DAY 3 Students will be given 15 minutes to finish their posters and hang them up around the classroom Students will walk around the room and look at the posters created by their classmates Students will play close attention to:

Directions: You will create an effective propaganda poster on one of the topics below that could have been used in World War I. • Possible topics: • Enlistment and recruitment • The role of women • Financing the war • Food conservation • Aiding our allies • Entering the war • Guidelines • The poster will be drawn or printed (using photoshop or etc) on 8 ½” by 11” paper and graded on your use of message/theme, creativity, neatness, historical accuracy, explanation, and use of characteristics/techniques

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Connotations of the term propaganda

Related terms.

- Signs, symbols, and media used in contemporary propaganda

- Early commentators and theories

- Modern research and the evolution of current theories

- Present and expected conditions in the world social system

- Present and expected conditions in subsystems

- Propagandists and their agents

- Selection and presentation of symbols

- Media of propaganda

- The reactors (audiences)

- Measurement of the effects of propaganda

- Countermeasures by opponents

- Measures against countermeasures

- Democratic control of propaganda

- Authoritarian control of propaganda

- World-level control of propaganda

- How did Joseph Goebbels rise to power in the Nazi Party?

- How did Joseph Goebbels affect the Nazi movement?

- Why was Adolf Hitler significant?

- How did Adolf Hitler rise to power?

- Why did Adolf Hitler start World War II?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Literary Devices - Propaganda

- American Historical Association - What is Propaganda?

- University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign - What is Propaganda?

- propaganda - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

What is propaganda?

Propaganda is the dissemination of information—facts, arguments, rumours, half-truths, or lies—to influence public opinion . Deliberateness and a relatively heavy emphasis on manipulation distinguish propaganda from casual conversation or the free and easy exchange of ideas.

When was propaganda first used?

People have employed the principles of propaganda—manipulating the dissemination of information and using symbols in an attempt to influence public opinion —for thousands of years, although the term propaganda , used in this sense, didn’t come about until the 17th century.

Where is propaganda used?

Propaganda can be used in several areas, such as commercial advertising , public relations , political campaigns, diplomatic negotiations , legal arguments, and collective bargaining . It can be targeted toward groups of varying size and at the local, national, or global level.

Who was the minister of propaganda for Hitler?

Joseph Goebbels was the minister of propaganda for the German Third Reich under Adolf Hitler .

Recent News

propaganda , dissemination of information—facts, arguments, rumours, half-truths, or lies—to influence public opinion . It is often conveyed through mass media .

Propaganda is the more or less systematic effort to manipulate other people’s beliefs, attitudes, or actions by means of symbols (words, gestures, banners, monuments, music, clothing, insignia, hairstyles, designs on coins and postage stamps, and so forth). Deliberateness and a relatively heavy emphasis on manipulation distinguish propaganda from casual conversation or the free and easy exchange of ideas. Propagandists have a specified goal or set of goals. To achieve these, they deliberately select facts, arguments, and displays of symbols and present them in ways they think will have the most effect. To maximize effect, they may omit or distort pertinent facts or simply lie, and they may try to divert the attention of the reactors (the people they are trying to sway) from everything but their own propaganda.

Comparatively deliberate selectivity and manipulation also distinguish propaganda from education . Educators try to present various sides of an issue—the grounds for doubting as well as the grounds for believing the statements they make, and the disadvantages as well as the advantages of every conceivable course of action. Education aims to induce reactors to collect and evaluate evidence for themselves and assists them in learning the techniques for doing so. It must be noted, however, that some propagandists may look upon themselves as educators and may believe that they are uttering the purest truth, that they are emphasizing or distorting certain aspects of the truth only to make a valid message more persuasive , or that the courses of action that they recommend are in fact the best actions that the reactor could take. By the same token, the reactor who regards the propagandist’s message as self-evident truth may think of it as educational; this often seems to be the case with “true believers”— dogmatic reactors to dogmatic religious, social, or political propaganda. “Education” for one person may be “propaganda” for another.

Propaganda and related concepts

The word propaganda itself, as used in recent centuries, apparently derives from the title and work of the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (Congregation for Propagation of the Faith), an organization of Roman Catholic cardinals founded in 1622 to carry on missionary work. To many Roman Catholics the word may therefore have, at least in missionary or ecclesiastical terms, a highly respectable connotation . But even to these persons, and certainly to many others, the term is often a pejorative one tending to connote such things as the discredited atrocity stories and deceptively stated war aims of World Wars I and II, the operations of the Nazi s’ Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, and the broken campaign promises of a thousand politicians. Also, it is reminiscent of countless instances of false and misleading advertising (especially in countries using Latin languages, in which propagande commerciale or some equivalent is a common term for commercial advertising ).

To informed students of the history of communism , the term propaganda has yet another connotation, associated with the term agitation . The two terms were first used by the Russian theorist of Marxism Georgy Plekhanov and later elaborated upon by Vladimir Ilich Lenin in a pamphlet What Is to Be Done? (1902), in which he defined “propaganda” as the reasoned use of historical and scientific arguments to indoctrinate the educated and enlightened (the attentive and informed publics, in the language of today’s social sciences ); he defined “agitation” as the use of slogans, parables, and half-truths to exploit the grievances of the uneducated and the unreasonable. Since he regarded both strategies as absolutely essential to political victory, he combined them in the term agitprop . Every unit of historical communist parties had an agitprop section, and to the communist the use of propaganda in Lenin’s sense was commendable and honest. Thus, a standard Soviet manual for teachers of social sciences was entitled Propagandistu politekonomii ( For the Propagandist of Political Economy ), and a pocket-sized booklet issued weekly to suggest timely slogans and brief arguments to be used in speeches and conversations among the masses was called Bloknot agitatora ( The Agitator’s Notebook ).

Related to the general sense of propaganda is the concept of “ propaganda of the deed.” This denotes taking nonsymbolic action (such as economic or coercive action), not for its direct effects but for its possible propagandistic effects. Examples of propaganda of the deed would include staging an atomic “test” or the public torture of a criminal for its presumable deterrent effect on others, or giving foreign “economic aid” primarily to influence the recipient’s opinions or actions and without much intention of building up the recipient’s economy.

Distinctions are sometimes made between overt propaganda, in which the propagandists and perhaps their backers are made known to the reactors, and covert propaganda, in which the sources are secret or disguised. Covert propaganda might include such things as political advertisements that are unsigned or signed with false names, clandestine radio stations using false names, and statements by editors, politicians, or others who have been secretly bribed by governments, political backers, or business firms. Sophisticated diplomatic negotiation, legal argument , collective bargaining , commercial advertising, and political campaigns are of course quite likely to include considerable amounts of both overt and covert propaganda, accompanied by propaganda of the deed.

Another term related to propaganda is psychological warfare (sometimes abbreviated to psychwar ), which is the prewar or wartime use of propaganda directed primarily at confusing or demoralizing enemy populations or troops, putting them off guard in the face of coming attacks, or inducing them to surrender. The related concept of political warfare encompasses the use of propaganda, among many other techniques, during peacetime to intensify social and political divisions and to sow confusion within the societies of adversary states.

Still another related concept is that of brainwashing . The term usually means intensive political indoctrination. It may involve long political lectures or discussions, long compulsory reading assignments, and so forth, sometimes in conjunction with efforts to reduce the reactor’s resistance by exhausting him either physically through torture , overwork, or denial of sleep or psychologically through solitary confinement , threats, emotionally disturbing confrontations with interrogators or defected comrades, humiliation in front of fellow citizens, and the like. The term brainwashing was widely used in sensational journalism to refer to such activities (and to many other activities) as they were allegedly conducted by Maoists in China and elsewhere.

Another related word, advertising , has mainly commercial connotations , though it need not be restricted to this; political candidates, party programs, and positions on political issues may be “packaged” and “marketed” by advertising firms. The words promotion and public relations have wider, vaguer connotations and are often used to avoid the implications of “advertising” or “propaganda.” “Publicity” and “publicism” often imply merely making a subject known to a public, without educational, propagandistic, or commercial intent.

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Takeaways from AP analysis of Gaza Health Ministry’s death toll data

FILE - Palestinians search for bodies and survivors in the rubble of a residential building destroyed in an Israeli airstrike in Rafah, Gaza Strip, on March 4, 2024. An AP analysis of Gaza Health Ministry data finds the proportion of Palestinian women and children being killed in the Israel-Hamas war appears to have declined sharply. Israel faces heavy international criticism over unprecedented levels of civilian casualties in Gaza. (AP Photo/Fatima Shbair, File)

FILE - Palestinians pray over bodies of people killed in the Israeli bombardment of the Gaza Strip, on Nov. 22, 2023. An AP analysis of Gaza Health Ministry data finds the proportion of Palestinian women and children being killed in the Israel-Hamas war appears to have declined sharply. Israel faces heavy international criticism over unprecedented levels of civilian casualties in Gaza. (AP Photo/Mohammed Dahman, File)

- Copy Link copied

JERUSALEM (AP) — The Israel-Hamas war appears to have become much less deadly for Palestinian women and children, according to an AP analysis of Gaza Health Ministry data.

The shift is significant because the death rate for women and children is the best available proxy for civilian casualties in one of the 21st century’s most destructive conflicts .

Women and children made up fewer than 40% of those killed in the Gaza Strip during April, down from more than 60% in October. The decline both coincides with Israel’s changing battlefield tactics and contradicts the ministry’s own public statements.

Here are takeaways from The Associated Press’ reporting.

FATALITY TRENDS AND THE TACTICS OF WAR

After Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack, Israel launched an intense aerial bombardment on densely populated Gaza, and then invaded with thousands of ground troops backed by tanks and artillery.

By the end of October women and people 17 and younger accounted for 64% of the 6,745 killed who were fully identified by the Health Ministry.

After saying it had achieved many key objectives, the Israeli army began withdrawing ground troops earlier this year. It has focused lately on drone strikes and limited ground operations .

As the intensity of fighting has scaled back, the death toll has continued to rise, but at a slower rate – and with seemingly fewer civilians caught in the crossfire. During the month of April, women and children made up 38% of the fully identified deaths, the Health Ministry’s most recent data shows.

A TALE OF TWO DEATH TOLLS

The ministry announces a new death toll for the war nearly every day. It also has periodically released the underlying data behind this figure, including detailed lists of the dead.

The AP’s analysis looked at these lists, which were shared on social media in late October, early January, late March, and the end of April.

As recently as March, the ministry claimed over several days that 72% of the dead were women and children, even as underlying data showed the percentage was well below that.

Israeli leaders have pointed to such inconsistencies as evidence that the ministry is inflating the figures for political gain.

Experts say the reality is more complicated and that the ministry has been overwhelmed by war, making it difficult to track casualties.

CIVILIAN DEATHS FUEL CRITICISM OF ISRAEL

The true toll in Gaza could have serious repercussions.

Israel faces heavy international criticism over unprecedented levels of civilian casualties in Gaza and questions about whether it has done enough to prevent them in an eight-month-old war that shows no sign of ending. An airstrike in Rafah last month killed dozens of Palestinians, and one on a school-turned-shelter in central Gaza on Thursday killed at least 33 people, including 12 women and children , health officials said.

Two international courts in the Hague are examining accusations that Israel has committed war crimes and genocide against Palestinians – allegations it adamantly denies.

Israel says it has tried to avoid civilian casualties, issuing mass evacuation orders ahead of intense military operations that have displaced some 80% of Gaza’s population. It also accuses Hamas of intentionally putting civilians in harm’s way as human shields.

The fate of women and children is an important indicator of civilian casualties because the Health Ministry does not break out combatant deaths. But it’s not a perfect indicator: Many civilian men have died, and some older teenagers may be involved in the fighting.

MANY DEATHS COUNTED IN GAZA REMAIN ‘UNIDENTIFIED’

The ministry said publicly on April 30 that 34,622 had died in the war. The AP analysis was based on the 22,961 individuals fully identified at the time by the Health Ministry with names, genders, ages, and Israeli-issued identification numbers.

The ministry says 9,940 of the dead – 29% of its April 30 total – were not listed in the data because they remain “unidentified.” These include bodies not claimed by families, decomposed beyond recognition or whose records were lost in Israeli raids on hospitals.

An additional 1,699 records in the ministry’s April data were incomplete and 22 were duplicates; they were excluded from AP’s analysis.

Among those fully identified, the records show a steady decline in the overall proportion of women and children who have been killed: from 64% in late October, to 62% as of early January, to 57% at the end of March, to 54% at the end of April.

Some critics say the ministry’s imprecise methodologies – relying on families and “media reports” to confirm deaths – have added additional uncertainty to the figures.

The Health Ministry says it has gone to great lengths to accurately compile information but that its ability to count and identify the dead has been hampered by the war.

HEALTH MINISTRY STANDS BY ITS COUNT

Dr. Moatasem Salah, director of the ministry’s emergency center, rejected Israeli assertions that his ministry has intentionally inflated or manipulated the death toll.

“This shows disrespect to the humanity for any person who exists here,” he said. “We are not numbers … These are all human souls.”

He insisted that 70% of those killed have been women and children and said the overall death toll is much higher than what has been reported because thousands of people remain missing or are believed to be buried in rubble.

Israel last month angrily criticized the U.N.’s use of data from Hamas’ media office – a propaganda arm of the militant group – that reported a larger number of women and children killed. The U.N. later lowered its number in line with Health Ministry figures.

The number of Hamas militants killed in the fighting is also unclear. Hamas has closely guarded this information, though Khalil al-Hayya, a top Hamas official, told the AP in late April that the group had lost no more than 20% of its fighters. That would amount to roughly 6,000 fighters based on Israeli pre-war estimates.

The Israeli military has not challenged the overall death toll released by the Palestinian ministry. But it says the number of dead militants is much higher at roughly 15,000 – or over 40% of all the dead. It has provided no evidence to support the claim, and declined to comment for this story.

Michael Spagat, a London-based economics professor who chairs the board of Every Casualty Counts, a nonprofit that tracks armed conflicts, said he continues to trust the Health Ministry and believes it is doing its best in difficult circumstances.

“I think (the data) becomes increasingly flawed,” he said. But, he added, “the flaws don’t necessarily change the overall picture.”

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Microsoft Word - 4-a-4-all_e.doc. Description: In this lesson, students learn to analyze some basic propaganda techniques. Students will look at the way images and words are combined to create effective propaganda messages. Students will demonstrate their understanding of this by creating their own First World War propaganda poster.

Propaganda Analysis Revisited. This special issue is designed to place our contemporary post-truth impasse in historical perspective. Drawing comparisons to the Propaganda Analysis research paradigm of the Interwar years, this essay and issue call attention to historical similarities between patterns in mass communication research then and now.

In this activity, you will examine a variety of posters from World War I as a way of trying to develop an understanding of propaganda, nationalism, total war, and gender and social class during World War I. Take out the World War I Poster Analysis worksheet and pick two posters from each category and compare them. The categories are: • Total war

This worksheet helps students analyze government propaganda posters. Download and Save : poster analysis worksheet.pdf Source | American Social History Project/Center for Media and Learning, 2011.

paigns, but a true understanding of propaganda requires analysis of the long-term effects. Propaganda includes the reinforcement of cultural myths and stereotypes that are so deeply embedded in a culture that recognizing a mes-sage as propaganda is often difficult. As we said in Chapter 1, propaganda is a deliberate and systematic

examination of propaganda messages and media, sensitivity to audience responses, and critical scrutiny of the entire propaganda process. One may be tempted to exam-ine the short-term aspects of propaganda campaigns, but a true understanding of propaganda requires analysis of the long-term effects. Propaganda includes the rein-

Point out the connections between the questions in the interactive and the questions listed on the Document Analysis for Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda. If students need additional practice with analysis, choose a poster and use the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive to work through all the analysis questions as a whole class.

World War II: Posters and Propaganda "United We Win," US Office of War Information, 1942. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC09542) ... CCSS.ELA-Literccy.RH.6-8.1: Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-8.2: Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or ...

In addition to a collection of wartime propaganda posters, the site includes a brief essay providing historical context, as well as a well-designed " propaganda poster analysis worksheet " that students can use to explore the meaning of each document. After work in small groups that includes each student analyzing a poster, students ...

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research. World War II Posters and Propaganda | Click here to download this four-lesson unit. | Click here to download this four-lesson unit.

The teacher may choose one assignment from the list below or allow students to choose from among the options; the teacher may also differentiate the lesson by varying which assignment is given to each student: ... academics and journalists established the Institute for Propaganda Analysis. The Institute identified seven basic propaganda devices ...

Founded in 1937, the New York-based Institute for Propaganda Analysis (IPA) created materials and teaching methods to help educators and the public detect, recognize, and analyze propaganda. As part of their curriculum, they created the ABCs of Propaganda Analysis, which remains a relevant guide to examining current forms of propaganda.

Nazi Propaganda Analysis Standards: History: Knowledge, Evaluate Points of View Assignment: Select one example of Nazi propaganda that we looked at in class. Analyze the example to create a written analysis of the propaganda.

The Rhetoric of American World War I Propaganda Posters unit sequence uses primary sources to introduce students to the basics of rhetorical and visual analysis, multimodal composition, and scholarly research and writing. ... Next, in the rhetorical analysis phase of the assignment, students will use the information they have gained and their ...

2. Using the "Types of Propaganda" sheet and the Propaganda Fact Sheet, have a brief discussion of the different types of propaganda. Make sure students are clear in their understanding of the types of propaganda before they begin their individual work. 3. Have students first complete the worksheets and then the poster analysis. 4.