An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Anti-bullying interventions in schools: a systematic literature review

Affiliations.

- 1 Departamento de Enfermagem Materno Infantil e Saúde Pública, Escola de Enfermagem de Ribeirão Preto, USP. Av. Bandeirantes 3900, Monte Alegre. 14040-902 Ribeirão Preto SP Brasil. [email protected].

- 2 Departamento de Enfermagem Psiquiátrica e Ciências Humanas, Escola de Enfermagem de Ribeirão Preto, USP. Ribeirão Preto SP Brasil.

- 3 Departamento de Psicologia, Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto, USP. Ribeirão Preto SP Brasil.

- PMID: 28724015

- DOI: 10.1590/1413-81232017227.16242015

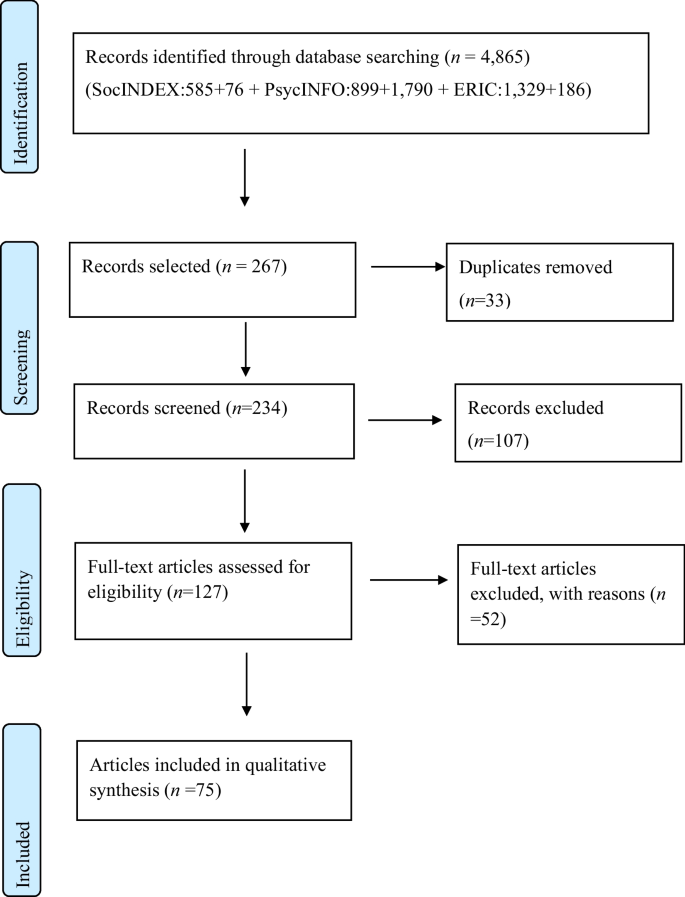

This paper presents a systematic literature review addressing rigorously planned and assessed interventions intended to reduce school bullying. The search for papers was performed in four databases (Lilacs, Psycinfo, Scielo and Web of Science) and guided by the question: What are the interventions used to reduce bullying in schools? Only case-control studies specifically focusing on school bullying without a time frame were included. The methodological quality of investigations was assessed using the SIGN checklist. A total of 18 papers composed the corpus of analysis and all were considered to have high methodological quality. The interventions conducted in the revised studies were divided into four categories: multi-component or whole-school, social skills training, curricular, and computerized. The review synthesizes knowledge that can be used to contemplate practices and intervention programs in the education and health fields with a multidisciplinary nature.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Preventing Transphobic Bullying and Promoting Inclusive Educational Environments: Literature Review and Implementing Recommendations. Domínguez-Martínez T, Robles R. Domínguez-Martínez T, et al. Arch Med Res. 2019 Nov;50(8):543-555. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2019.10.009. Epub 2020 Feb 6. Arch Med Res. 2019. PMID: 32036103 Review.

- An evaluation of police officers in schools as a bullying intervention. Devlin DN, Santos MR, Gottfredson DC. Devlin DN, et al. Eval Program Plann. 2018 Dec;71:12-21. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2018.07.004. Epub 2018 Jul 25. Eval Program Plann. 2018. PMID: 30075466

- School-Based Interventions Going Beyond Health Education to Promote Adolescent Health: Systematic Review of Reviews. Shackleton N, Jamal F, Viner RM, Dickson K, Patton G, Bonell C. Shackleton N, et al. J Adolesc Health. 2016 Apr;58(4):382-396. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.12.017. J Adolesc Health. 2016. PMID: 27013271 Review.

- Translating research to practice in bullying prevention. Bradshaw CP. Bradshaw CP. Am Psychol. 2015 May-Jun;70(4):322-32. doi: 10.1037/a0039114. Am Psychol. 2015. PMID: 25961313 Review.

- A systematic review of school-based interventions to prevent bullying. Vreeman RC, Carroll AE. Vreeman RC, et al. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007 Jan;161(1):78-88. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.1.78. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007. PMID: 17199071 Review.

- Bullying victimization among adolescents: Prevalence, associated factors and correlation with mental health outcomes. Ghardallou M, Mtiraoui A, Ennamouchi D, Amara A, Gara A, Dardouri M, Zedini C, Mtiraoui A. Ghardallou M, et al. PLoS One. 2024 Mar 18;19(3):e0299161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0299161. eCollection 2024. PLoS One. 2024. PMID: 38498423 Free PMC article.

- Associations between bullying and risk for eating disorders in adolescents. Oliveira PDR, Silva MAI, Oliveira WA, Komatsu AV, Brunherotti MAA, Rosário R, Silva JLD. Oliveira PDR, et al. Rev Bras Enferm. 2023 Nov 27;76(5):e20220643. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2022-0643. eCollection 2023. Rev Bras Enferm. 2023. PMID: 38018614 Free PMC article.

- Experiences of Being Bullied and the Quality of Life of Transgender Women in Chiang Mai Province, Thailand. Srikummoon P, Oonarom A, Manojai N, Maneeton B, Maneeton N, Wiriyacosol P, Chiawkhun P, Kawilapat S, Homkham N, Traisathit P. Srikummoon P, et al. Transgend Health. 2023 Mar 31;8(2):175-187. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2021.0068. eCollection 2023 Apr. Transgend Health. 2023. PMID: 37013090 Free PMC article.

- School-Based Nursing Interventions for Preventing Bullying and Reducing Its Incidence on Students: A Scoping Review. Yosep I, Hikmat R, Mardhiyah A. Yosep I, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Jan 15;20(2):1577. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20021577. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023. PMID: 36674330 Free PMC article. Review.

- Method of Nursing Interventions to Reduce the Incidence of Bullying and Its Impact on Students in School: A Scoping Review. Yosep I, Hikmat R, Mardhiyah A, Hazmi H, Hernawaty T. Yosep I, et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2022 Sep 22;10(10):1835. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10101835. Healthcare (Basel). 2022. PMID: 36292282 Free PMC article. Review.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Scientific Electronic Library Online

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 14 December 2021

Bullying at school and mental health problems among adolescents: a repeated cross-sectional study

- Håkan Källmén 1 &

- Mats Hallgren ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0599-2403 2

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health volume 15 , Article number: 74 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

106k Accesses

16 Citations

37 Altmetric

Metrics details

To examine recent trends in bullying and mental health problems among adolescents and the association between them.

A questionnaire measuring mental health problems, bullying at school, socio-economic status, and the school environment was distributed to all secondary school students aged 15 (school-year 9) and 18 (school-year 11) in Stockholm during 2014, 2018, and 2020 (n = 32,722). Associations between bullying and mental health problems were assessed using logistic regression analyses adjusting for relevant demographic, socio-economic, and school-related factors.

The prevalence of bullying remained stable and was highest among girls in year 9; range = 4.9% to 16.9%. Mental health problems increased; range = + 1.2% (year 9 boys) to + 4.6% (year 11 girls) and were consistently higher among girls (17.2% in year 11, 2020). In adjusted models, having been bullied was detrimentally associated with mental health (OR = 2.57 [2.24–2.96]). Reports of mental health problems were four times higher among boys who had been bullied compared to those not bullied. The corresponding figure for girls was 2.4 times higher.

Conclusions

Exposure to bullying at school was associated with higher odds of mental health problems. Boys appear to be more vulnerable to the deleterious effects of bullying than girls.

Introduction

Bullying involves repeated hurtful actions between peers where an imbalance of power exists [ 1 ]. Arseneault et al. [ 2 ] conducted a review of the mental health consequences of bullying for children and adolescents and found that bullying is associated with severe symptoms of mental health problems, including self-harm and suicidality. Bullying was shown to have detrimental effects that persist into late adolescence and contribute independently to mental health problems. Updated reviews have presented evidence indicating that bullying is causative of mental illness in many adolescents [ 3 , 4 ].

There are indications that mental health problems are increasing among adolescents in some Nordic countries. Hagquist et al. [ 5 ] examined trends in mental health among Scandinavian adolescents (n = 116, 531) aged 11–15 years between 1993 and 2014. Mental health problems were operationalized as difficulty concentrating, sleep disorders, headache, stomach pain, feeling tense, sad and/or dizzy. The study revealed increasing rates of adolescent mental health problems in all four counties (Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark), with Sweden experiencing the sharpest increase among older adolescents, particularly girls. Worsening adolescent mental health has also been reported in the United Kingdom. A study of 28,100 school-aged adolescents in England found that two out of five young people scored above thresholds for emotional problems, conduct problems or hyperactivity [ 6 ]. Female gender, deprivation, high needs status (educational/social), ethnic background, and older age were all associated with higher odds of experiencing mental health difficulties.

Bullying is shown to increase the risk of poor mental health and may partly explain these detrimental changes. Le et al. [ 7 ] reported an inverse association between bullying and mental health among 11–16-year-olds in Vietnam. They also found that poor mental health can make some children and adolescents more vulnerable to bullying at school. Bayer et al. [ 8 ] examined links between bullying at school and mental health among 8–9-year-old children in Australia. Those who experienced bullying more than once a week had poorer mental health than children who experienced bullying less frequently. Friendships moderated this association, such that children with more friends experienced fewer mental health problems (protective effect). Hysing et al. [ 9 ] investigated the association between experiences of bullying (as a victim or perpetrator) and mental health, sleep disorders, and school performance among 16–19 year olds from Norway (n = 10,200). Participants were categorized as victims, bullies, or bully-victims (that is, victims who also bullied others). All three categories were associated with worse mental health, school performance, and sleeping difficulties. Those who had been bullied also reported more emotional problems, while those who bullied others reported more conduct disorders [ 9 ].

As most adolescents spend a considerable amount of time at school, the school environment has been a major focus of mental health research [ 10 , 11 ]. In a recent review, Saminathen et al. [ 12 ] concluded that school is a potential protective factor against mental health problems, as it provides a socially supportive context and prepares students for higher education and employment. However, it may also be the primary setting for protracted bullying and stress [ 13 ]. Another factor associated with adolescent mental health is parental socio-economic status (SES) [ 14 ]. A systematic review indicated that lower parental SES is associated with poorer adolescent mental health [ 15 ]. However, no previous studies have examined whether SES modifies or attenuates the association between bullying and mental health. Similarly, it remains unclear whether school related factors, such as school grades and the school environment, influence the relationship between bullying and mental health. This information could help to identify those adolescents most at risk of harm from bullying.

To address these issues, we investigated the prevalence of bullying at school and mental health problems among Swedish adolescents aged 15–18 years between 2014 and 2020 using a population-based school survey. We also examined associations between bullying at school and mental health problems adjusting for relevant demographic, socioeconomic, and school-related factors. We hypothesized that: (1) bullying and adolescent mental health problems have increased over time; (2) There is an association between bullying victimization and mental health, so that mental health problems are more prevalent among those who have been victims of bullying; and (3) that school-related factors would attenuate the association between bullying and mental health.

Participants

The Stockholm school survey is completed every other year by students in lower secondary school (year 9—compulsory) and upper secondary school (year 11). The survey is mandatory for public schools, but voluntary for private schools. The purpose of the survey is to help inform decision making by local authorities that will ultimately improve students’ wellbeing. The questions relate to life circumstances, including SES, schoolwork, bullying, drug use, health, and crime. Non-completers are those who were absent from school when the survey was completed (< 5%). Response rates vary from year to year but are typically around 75%. For the current study data were available for 2014, 2018 and 2020. In 2014; 5235 boys and 5761 girls responded, in 2018; 5017 boys and 5211 girls responded, and in 2020; 5633 boys and 5865 girls responded (total n = 32,722). Data for the exposure variable, bullied at school, were missing for 4159 students, leaving 28,563 participants in the crude model. The fully adjusted model (described below) included 15,985 participants. The mean age in grade 9 was 15.3 years (SD = 0.51) and in grade 11, 17.3 years (SD = 0.61). As the data are completely anonymous, the study was exempt from ethical approval according to an earlier decision from the Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (2010-241 31-5). Details of the survey are available via a website [ 16 ], and are described in a previous paper [ 17 ].

Students completed the questionnaire during a school lesson, placed it in a sealed envelope and handed it to their teacher. Student were permitted the entire lesson (about 40 min) to complete the questionnaire and were informed that participation was voluntary (and that they were free to cancel their participation at any time without consequences). Students were also informed that the Origo Group was responsible for collection of the data on behalf of the City of Stockholm.

Study outcome

Mental health problems were assessed by using a modified version of the Psychosomatic Problem Scale [ 18 ] shown to be appropriate for children and adolescents and invariant across gender and years. The scale was later modified [ 19 ]. In the modified version, items about difficulty concentrating and feeling giddy were deleted and an item about ‘life being great to live’ was added. Seven different symptoms or problems, such as headaches, depression, feeling fear, stomach problems, difficulty sleeping, believing it’s great to live (coded negatively as seldom or rarely) and poor appetite were used. Students who responded (on a 5-point scale) that any of these problems typically occurs ‘at least once a week’ were considered as having indicators of a mental health problem. Cronbach alpha was 0.69 across the whole sample. Adding these problem areas, a total index was created from 0 to 7 mental health symptoms. Those who scored between 0 and 4 points on the total symptoms index were considered to have a low indication of mental health problems (coded as 0); those who scored between 5 and 7 symptoms were considered as likely having mental health problems (coded as 1).

Primary exposure

Experiences of bullying were measured by the following two questions: Have you felt bullied or harassed during the past school year? Have you been involved in bullying or harassing other students during this school year? Alternatives for the first question were: yes or no with several options describing how the bullying had taken place (if yes). Alternatives indicating emotional bullying were feelings of being mocked, ridiculed, socially excluded, or teased. Alternatives indicating physical bullying were being beaten, kicked, forced to do something against their will, robbed, or locked away somewhere. The response alternatives for the second question gave an estimation of how often the respondent had participated in bullying others (from once to several times a week). Combining the answers to these two questions, five different categories of bullying were identified: (1) never been bullied and never bully others; (2) victims of emotional (verbal) bullying who have never bullied others; (3) victims of physical bullying who have never bullied others; (4) victims of bullying who have also bullied others; and (5) perpetrators of bullying, but not victims. As the number of positive cases in the last three categories was low (range = 3–15 cases) bully categories 2–4 were combined into one primary exposure variable: ‘bullied at school’.

Assessment year was operationalized as the year when data was collected: 2014, 2018, and 2020. Age was operationalized as school grade 9 (15–16 years) or 11 (17–18 years). Gender was self-reported (boy or girl). The school situation To assess experiences of the school situation, students responded to 18 statements about well-being in school, participation in important school matters, perceptions of their teachers, and teaching quality. Responses were given on a four-point Likert scale ranging from ‘do not agree at all’ to ‘fully agree’. To reduce the 18-items down to their essential factors, we performed a principal axis factor analysis. Results showed that the 18 statements formed five factors which, according to the Kaiser criterion (eigen values > 1) explained 56% of the covariance in the student’s experience of the school situation. The five factors identified were: (1) Participation in school; (2) Interesting and meaningful work; (3) Feeling well at school; (4) Structured school lessons; and (5) Praise for achievements. For each factor, an index was created that was dichotomised (poor versus good circumstance) using the median-split and dummy coded with ‘good circumstance’ as reference. A description of the items included in each factor is available as Additional file 1 . Socio-economic status (SES) was assessed with three questions about the education level of the student’s mother and father (dichotomized as university degree versus not), and the amount of spending money the student typically received for entertainment each month (> SEK 1000 [approximately $120] versus less). Higher parental education and more spending money were used as reference categories. School grades in Swedish, English, and mathematics were measured separately on a 7-point scale and dichotomized as high (grades A, B, and C) versus low (grades D, E, and F). High school grades were used as the reference category.

Statistical analyses

The prevalence of mental health problems and bullying at school are presented using descriptive statistics, stratified by survey year (2014, 2018, 2020), gender, and school year (9 versus 11). As noted, we reduced the 18-item questionnaire assessing school function down to five essential factors by conducting a principal axis factor analysis (see Additional file 1 ). We then calculated the association between bullying at school (defined above) and mental health problems using multivariable logistic regression. Results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (Cis). To assess the contribution of SES and school-related factors to this association, three models are presented: Crude, Model 1 adjusted for demographic factors: age, gender, and assessment year; Model 2 adjusted for Model 1 plus SES (parental education and student spending money), and Model 3 adjusted for Model 2 plus school-related factors (school grades and the five factors identified in the principal factor analysis). These covariates were entered into the regression models in three blocks, where the final model represents the fully adjusted analyses. In all models, the category ‘not bullied at school’ was used as the reference. Pseudo R-square was calculated to estimate what proportion of the variance in mental health problems was explained by each model. Unlike the R-square statistic derived from linear regression, the Pseudo R-square statistic derived from logistic regression gives an indicator of the explained variance, as opposed to an exact estimate, and is considered informative in identifying the relative contribution of each model to the outcome [ 20 ]. All analyses were performed using SPSS v. 26.0.

Prevalence of bullying at school and mental health problems

Estimates of the prevalence of bullying at school and mental health problems across the 12 strata of data (3 years × 2 school grades × 2 genders) are shown in Table 1 . The prevalence of bullying at school increased minimally (< 1%) between 2014 and 2020, except among girls in grade 11 (2.5% increase). Mental health problems increased between 2014 and 2020 (range = 1.2% [boys in year 11] to 4.6% [girls in year 11]); were three to four times more prevalent among girls (range = 11.6% to 17.2%) compared to boys (range = 2.6% to 4.9%); and were more prevalent among older adolescents compared to younger adolescents (range = 1% to 3.1% higher). Pooling all data, reports of mental health problems were four times more prevalent among boys who had been victims of bullying compared to those who reported no experiences with bullying. The corresponding figure for girls was two and a half times as prevalent.

Associations between bullying at school and mental health problems

Table 2 shows the association between bullying at school and mental health problems after adjustment for relevant covariates. Demographic factors, including female gender (OR = 3.87; CI 3.48–4.29), older age (OR = 1.38, CI 1.26–1.50), and more recent assessment year (OR = 1.18, CI 1.13–1.25) were associated with higher odds of mental health problems. In Model 2, none of the included SES variables (parental education and student spending money) were associated with mental health problems. In Model 3 (fully adjusted), the following school-related factors were associated with higher odds of mental health problems: lower grades in Swedish (OR = 1.42, CI 1.22–1.67); uninteresting or meaningless schoolwork (OR = 2.44, CI 2.13–2.78); feeling unwell at school (OR = 1.64, CI 1.34–1.85); unstructured school lessons (OR = 1.31, CI = 1.16–1.47); and no praise for achievements (OR = 1.19, CI 1.06–1.34). After adjustment for all covariates, being bullied at school remained associated with higher odds of mental health problems (OR = 2.57; CI 2.24–2.96). Demographic and school-related factors explained 12% and 6% of the variance in mental health problems, respectively (Pseudo R-Square). The inclusion of socioeconomic factors did not alter the variance explained.

Our findings indicate that mental health problems increased among Swedish adolescents between 2014 and 2020, while the prevalence of bullying at school remained stable (< 1% increase), except among girls in year 11, where the prevalence increased by 2.5%. As previously reported [ 5 , 6 ], mental health problems were more common among girls and older adolescents. These findings align with previous studies showing that adolescents who are bullied at school are more likely to experience mental health problems compared to those who are not bullied [ 3 , 4 , 9 ]. This detrimental relationship was observed after adjustment for school-related factors shown to be associated with adolescent mental health [ 10 ].

A novel finding was that boys who had been bullied at school reported a four-times higher prevalence of mental health problems compared to non-bullied boys. The corresponding figure for girls was 2.5 times higher for those who were bullied compared to non-bullied girls, which could indicate that boys are more vulnerable to the deleterious effects of bullying than girls. Alternatively, it may indicate that boys are (on average) bullied more frequently or more intensely than girls, leading to worse mental health. Social support could also play a role; adolescent girls often have stronger social networks than boys and could be more inclined to voice concerns about bullying to significant others, who in turn may offer supports which are protective [ 21 ]. Related studies partly confirm this speculative explanation. An Estonian study involving 2048 children and adolescents aged 10–16 years found that, compared to girls, boys who had been bullied were more likely to report severe distress, measured by poor mental health and feelings of hopelessness [ 22 ].

Other studies suggest that heritable traits, such as the tendency to internalize problems and having low self-esteem are associated with being a bully-victim [ 23 ]. Genetics are understood to explain a large proportion of bullying-related behaviors among adolescents. A study from the Netherlands involving 8215 primary school children found that genetics explained approximately 65% of the risk of being a bully-victim [ 24 ]. This proportion was similar for boys and girls. Higher than average body mass index (BMI) is another recognized risk factor [ 25 ]. A recent Australian trial involving 13 schools and 1087 students (mean age = 13 years) targeted adolescents with high-risk personality traits (hopelessness, anxiety sensitivity, impulsivity, sensation seeking) to reduce bullying at school; both as victims and perpetrators [ 26 ]. There was no significant intervention effect for bullying victimization or perpetration in the total sample. In a secondary analysis, compared to the control schools, intervention school students showed greater reductions in victimization, suicidal ideation, and emotional symptoms. These findings potentially support targeting high-risk personality traits in bullying prevention [ 26 ].

The relative stability of bullying at school between 2014 and 2020 suggests that other factors may better explain the increase in mental health problems seen here. Many factors could be contributing to these changes, including the increasingly competitive labour market, higher demands for education, and the rapid expansion of social media [ 19 , 27 , 28 ]. A recent Swedish study involving 29,199 students aged between 11 and 16 years found that the effects of school stress on psychosomatic symptoms have become stronger over time (1993–2017) and have increased more among girls than among boys [ 10 ]. Research is needed examining possible gender differences in perceived school stress and how these differences moderate associations between bullying and mental health.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the current study include the large participant sample from diverse schools; public and private, theoretical and practical orientations. The survey included items measuring diverse aspects of the school environment; factors previously linked to adolescent mental health but rarely included as covariates in studies of bullying and mental health. Some limitations are also acknowledged. These data are cross-sectional which means that the direction of the associations cannot be determined. Moreover, all the variables measured were self-reported. Previous studies indicate that students tend to under-report bullying and mental health problems [ 29 ]; thus, our results may underestimate the prevalence of these behaviors.

In conclusion, consistent with our stated hypotheses, we observed an increase in self-reported mental health problems among Swedish adolescents, and a detrimental association between bullying at school and mental health problems. Although bullying at school does not appear to be the primary explanation for these changes, bullying was detrimentally associated with mental health after adjustment for relevant demographic, socio-economic, and school-related factors, confirming our third hypothesis. The finding that boys are potentially more vulnerable than girls to the deleterious effects of bullying should be replicated in future studies, and the mechanisms investigated. Future studies should examine the longitudinal association between bullying and mental health, including which factors mediate/moderate this relationship. Epigenetic studies are also required to better understand the complex interaction between environmental and biological risk factors for adolescent mental health [ 24 ].

Availability of data and materials

Data requests will be considered on a case-by-case basis; please email the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Olweus D. School bullying: development and some important challenges. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9(9):751–80. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516 .

Article Google Scholar

Arseneault L, Bowes L, Shakoor S. Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: “Much ado about nothing”? Psychol Med. 2010;40(5):717–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709991383 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Arseneault L. The long-term impact of bullying victimization on mental health. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):27–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20399 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Moore SE, Norman RE, Suetani S, Thomas HJ, Sly PD, Scott JG. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7(1):60–76. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60 .

Hagquist C, Due P, Torsheim T, Valimaa R. Cross-country comparisons of trends in adolescent psychosomatic symptoms—a Rasch analysis of HBSC data from four Nordic countries. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1097-x .

Deighton J, Lereya ST, Casey P, Patalay P, Humphrey N, Wolpert M. Prevalence of mental health problems in schools: poverty and other risk factors among 28 000 adolescents in England. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;215(3):565–7. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.19 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Le HTH, Tran N, Campbell MA, Gatton ML, Nguyen HT, Dunne MP. Mental health problems both precede and follow bullying among adolescents and the effects differ by gender: a cross-lagged panel analysis of school-based longitudinal data in Vietnam. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-019-0291-x .

Bayer JK, Mundy L, Stokes I, Hearps S, Allen N, Patton G. Bullying, mental health and friendship in Australian primary school children. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2018;23(4):334–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12261 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Hysing M, Askeland KG, La Greca AM, Solberg ME, Breivik K, Sivertsen B. Bullying involvement in adolescence: implications for sleep, mental health, and academic outcomes. J Interpers Violence. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519853409 .

Hogberg B, Strandh M, Hagquist C. Gender and secular trends in adolescent mental health over 24 years—the role of school-related stress. Soc Sci Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112890 .

Kidger J, Araya R, Donovan J, Gunnell D. The effect of the school environment on the emotional health of adolescents: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):925–49. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2248 .

Saminathen MG, Låftman SB, Modin B. En fungerande skola för alla: skolmiljön som skyddsfaktor för ungas psykiska välbefinnande. [A functioning school for all: the school environment as a protective factor for young people’s mental well-being]. Socialmedicinsk tidskrift [Soc Med]. 2020;97(5–6):804–16.

Google Scholar

Bibou-Nakou I, Tsiantis J, Assimopoulos H, Chatzilambou P, Giannakopoulou D. School factors related to bullying: a qualitative study of early adolescent students. Soc Psychol Educ. 2012;15(2):125–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-012-9179-1 .

Vukojevic M, Zovko A, Talic I, Tanovic M, Resic B, Vrdoljak I, Splavski B. Parental socioeconomic status as a predictor of physical and mental health outcomes in children—literature review. Acta Clin Croat. 2017;56(4):742–8. https://doi.org/10.20471/acc.2017.56.04.23 .

Reiss F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2013;90:24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026 .

Stockholm City. Stockholmsenkät (The Stockholm Student Survey). 2021. https://start.stockholm/aktuellt/nyheter/2020/09/presstraff-stockholmsenkaten-2020/ . Accessed 19 Nov 2021.

Zeebari Z, Lundin A, Dickman PW, Hallgren M. Are changes in alcohol consumption among swedish youth really occurring “in concert”? A new perspective using quantile regression. Alc Alcohol. 2017;52(4):487–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agx020 .

Hagquist C. Psychometric properties of the PsychoSomatic Problems Scale: a Rasch analysis on adolescent data. Social Indicat Res. 2008;86(3):511–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9186-3 .

Hagquist C. Ungas psykiska hälsa i Sverige–komplexa trender och stora kunskapsluckor [Young people’s mental health in Sweden—complex trends and large knowledge gaps]. Socialmedicinsk tidskrift [Soc Med]. 2013;90(5):671–83.

Wu W, West SG. Detecting misspecification in mean structures for growth curve models: performance of pseudo R(2)s and concordance correlation coefficients. Struct Equ Model. 2013;20(3):455–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2013.797829 .

Holt MK, Espelage DL. Perceived social support among bullies, victims, and bully-victims. J Youth Adolscence. 2007;36(8):984–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9153-3 .

Mark L, Varnik A, Sisask M. Who suffers most from being involved in bullying-bully, victim, or bully-victim? J Sch Health. 2019;89(2):136–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12720 .

Tsaousis I. The relationship of self-esteem to bullying perpetration and peer victimization among schoolchildren and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2016;31:186–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2016.09.005 .

Veldkamp SAM, Boomsma DI, de Zeeuw EL, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Bartels M, Dolan CV, van Bergen E. Genetic and environmental influences on different forms of bullying perpetration, bullying victimization, and their co-occurrence. Behav Genet. 2019;49(5):432–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-019-09968-5 .

Janssen I, Craig WM, Boyce WF, Pickett W. Associations between overweight and obesity with bullying behaviors in school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1187–94. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.5.1187 .

Kelly EV, Newton NC, Stapinski LA, Conrod PJ, Barrett EL, Champion KE, Teesson M. A novel approach to tackling bullying in schools: personality-targeted intervention for adolescent victims and bullies in Australia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(4):508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.04.010 .

Gunnell D, Kidger J, Elvidge H. Adolescent mental health in crisis. BMJ. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2608 .

O’Reilly M, Dogra N, Whiteman N, Hughes J, Eruyar S, Reilly P. Is social media bad for mental health and wellbeing? Exploring the perspectives of adolescents. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;23:601–13.

Unnever JD, Cornell DG. Middle school victims of bullying: who reports being bullied? Aggr Behav. 2004;30(5):373–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20030 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to the Department for Social Affairs, Stockholm, for permission to use data from the Stockholm School Survey.

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. None to declare.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Stockholm Prevents Alcohol and Drug Problems (STAD), Center for Addiction Research and Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden

Håkan Källmén

Epidemiology of Psychiatric Conditions, Substance Use and Social Environment (EPiCSS), Department of Global Public Health, Karolinska Institutet, Level 6, Solnavägen 1e, Solna, Sweden

Mats Hallgren

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

HK conceived the study and analyzed the data (with input from MH). HK and MH interpreted the data and jointly wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mats Hallgren .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

As the data are completely anonymous, the study was exempt from ethical approval according to an earlier decision from the Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (2010-241 31-5).

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Principal factor analysis description.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Källmén, H., Hallgren, M. Bullying at school and mental health problems among adolescents: a repeated cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 15 , 74 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-021-00425-y

Download citation

Received : 05 October 2021

Accepted : 23 November 2021

Published : 14 December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-021-00425-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Adolescents

- School-related factors

- Gender differences

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health

ISSN: 1753-2000

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

Anti-bullying interventions in schools: a systematic literature review

- September 2018

- Ciência & Saúde Coletiva

- Universidade de Franca

- Pontifical Catholic University of Campinas

- University of São Paulo

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Lara E. Law

- Thomas Nielsen

- Aline Pestana Santos

- Bobby K. Cheon

- Meegan R Smith

- Julia M P Bittner

- Ahlem Mtiraoui

- Dorra Ennamouchi

- Angelina Forde

- Priscilla dos Reis Oliveira

- Vários autores

- Elisa Poskiparta

- Estud Psicolog

- Isabela Zaine

- M.J.D. Reis

- Ricardo da Costa Padovani

- EUR J PUBLIC HEALTH

- Ioana Galea Beldean

- Rev Bras Epidemiol

- Claudio Crespo

- Patrick M. Vivier

- Annie Gjelsvik

- EDUC PSYCHOL-UK

- Rebecca Alamaa

- AGGRESSIVE BEHAV

- Ralf Wölfer

- AUST J GUID COUNS

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Psychology

Volume 65, 2014, review article, bullying in schools: the power of bullies and the plight of victims.

- Jaana Juvonen 1 , and Sandra Graham 2

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: 1 Department of Psychology, 2 Department of Education, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095; email: [email protected]

- Vol. 65:159-185 (Volume publication date January 2014) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115030

- First published as a Review in Advance on August 05, 2013

- © Annual Reviews

Bullying is a pervasive problem affecting school-age children. Reviewing the latest findings on bullying perpetration and victimization, we highlight the social dominance function of bullying, the inflated self-views of bullies, and the effects of their behaviors on victims. Illuminating the plight of the victim, we review evidence on the cyclical processes between the risk factors and consequences of victimization and the mechanisms that can account for elevated emotional distress and health problems. Placing bullying in context, we consider the unique features of electronic communication that give rise to cyberbullying and the specific characteristics of schools that affect the rates and consequences of victimization. We then offer a critique of the main intervention approaches designed to reduce school bullying and its harmful effects. Finally, we discuss future directions that underscore the need to consider victimization a social stigma, conduct longitudinal research on protective factors, identify school context factors that shape the experience of victimization, and take a more nuanced approach to school-based interventions.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month

Most cited most cited rss feed, job burnout, executive functions, social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective, on happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it, mediation analysis, missing data analysis: making it work in the real world, grounded cognition, personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model, motivational beliefs, values, and goals.

Publication Date: 03 Jan 2014

Online Option

Get immediate access to your online copy - available in PDF and ePub formats

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Effectiveness of Policy Interventions for School Bullying: A Systematic Review

William hall.

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Associated Data

Bullying threatens the mental and educational well-being of students. Although anti-bullying policies are prevalent, little is known about their effectiveness. This systematic review evaluates the methodological characteristics and summarizes substantive findings of studies examining the effectiveness of school bullying policies.

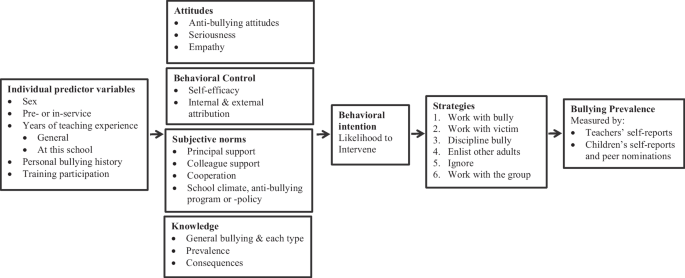

Searches of 11 bibliographic databases yielded 489 studies completed since January 1, 1995. Following duplicate removal and double-independent screening based on a priori inclusion criteria, 21 studies were included for review.

Substantially more educators perceive anti-bullying policies to be effective rather than ineffective. Whereas several studies show that the presence or quality of policies is associated with lower rates of bullying among students, other studies found no such associations between policy presence or quality and reductions in bullying. Consistent across studies, this review found that schools with anti-bullying policies that enumerated protections based on sexual orientation and gender identity were associated with better protection of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) students. Specifically, LGBTQ students in schools with such policies reported less harassment and more frequent and effective intervention by school personnel. Findings are mixed regarding the relationship between having an anti-bullying policy and educators’ responsiveness to general bullying.

Conclusions

Anti-bullying policies might be effective at reducing bullying if their content is based on evidence and sound theory and if they are implemented with a high level of fidelity. More research is needed to improve on limitations among extant studies.

Bullying in schools is a pervasive threat to the well-being and educational success of students. Bullying refers to unwanted aggressive behaviors enacted intentionally over time by an individual or group using some form of power to cause physical and/or psychological harm to another individual or group in a shared social context ( Gladden, Vivolo-Kantor, Hamburger, & Lumpkin, 2014 ; Olweus, 2013 ). Bullying is also a widespread phenomenon. A meta-analysis of 82 studies conducted in 22 countries in North America, South America, Europe, Southern Africa, East Asia, and Australia and Oceania found that 53% of youth were involved in bullying as bullies, victims, or both bullies and victims ( Cook, Williams, Guerra, & Kim, 2010 ).

Involvement in bullying as perpetrators, victims, bully–victims, and bystanders has been linked with deleterious outcomes by both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Youths who are bullied can experience immediate negative effects that include physical injury, humiliation, sadness, rejection, and helplessness ( Kaiser & Rasminsky, 2009 ). Over time, a number of mental and behavioral health problems can emerge, including low self-esteem, anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation and behavior, conduct problems, psychosomatic problems, psychotic symptoms, and physical illness ( Arseneault, Bowes, & Shakoor, 2010 ; Dake, Price, & Telljohann, 2003 ; Gini & Pozzoli, 2009 ; Kim & Leventhal, 2008 ; Klomek, Sourander, & Gould, 2010 ; Reijntjes et al., 2011 ; Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie, & Telch, 2010 ; Ttofi, Farrington, Lösel, & Loeber, 2011a ). In addition, students who have been bullied may not feel safe at school and may disengage from the school community due to fear and sadness, which may, in turn, contribute to higher rates of absenteeism and lower academic performance ( Arseneault et al., 2006 ; Buhs & Ladd, 2001 ; Buhs, Ladd, & Herald, 2006 ; Glew, Fan, Katon, Rivara, & Kernic, 2005 ; Juvonen, Nishina, & Graham, 2000 ; Nakamoto & Schwartz, 2010 ).

Youths who bully also face psychosocial difficulties. These youths often grow up in harsh social environments with few resources ( Hong & Espelage, 2012 ), and bullies often lack impulse control and empathy for others ( O’Brennan, Bradshaw, & Sawyer, 2009 ; van Noorden, Haselager, Cillessen, & Bukowski, 2015 ). Students who bully are more likely to skip school, perform poorly, and drop out ( Jankauskiene, Kardelis, Sukys, & Kardeliene, 2008 ; Ma, Phelps, Lerner, & Lerner, 2009 ). Bullying perpetration also is associated with depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation and behavior, and violent and criminal behavior (e.g., assault, robbery, vandalism, carrying weapons, and rape; Dake et al., 2003 ; Kim& Leventhal, 2008 ; Klomek et al., 2010 ; Ttofi, Farrington, & Lösel, 2012 ; Ttofi, Farrington, Lösel, & Loeber, 2011b ). Compared to nonperpetrators, students who bully have an increased risk of violent and criminal behaviors into adulthood. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies found that school bullies were 2.5 times more likely to engage in criminal offending over an 11-year follow-up period ( Ttofi et al., 2011b ).

Other youths involved in bullying include bully–victims and bystanders. Bully–victims are students who have been bullied but also engage in bullying others. Bully–victims can experience a combination of internalizing and externalizing problems ( Cook, Williams, Guerra, Kim, & Sadek, 2010 ). Student bystanders are present in up to 90% of bullying incidents ( Atlas & Pepler, 1998 ; Craig & Pepler, 1995 ; Glew et al., 2005 ; Hawkins, Pepler, & Craig, 2001 ). Youths who witness bullying often report emotional distress, including increased heart rate and higher levels of fear, sadness, and anger when recalling bullying incidents ( Barhight, Hubbard, & Hyde, 2013 ; Janson & Hazler, 2004 ). Thus, across the literature, bullying is associated with problematic outcomes for perpetrators, victims, bully–victims, and bystanders alike.

Policy as an Intervention for Bullying

Perspectives vary on how to best address bullying in schools. Intervention strategies have included suspending and expelling bullies, training teachers on intervening, teaching empathy and respect to students through classroom lessons, maintaining constant adult supervision throughout school settings, collaborating with parents about student behavior, and enacting school-wide policies about bullying. In the United States, policies addressing bullying emerged in 1999 following the Columbine High School shootings. These policies have spread due to increased awareness and concern about student violence and school safety ( Birkland & Lawrence, 2009 ). A policy is a system of principles created by governing bodies or public officials to achieve specific outcomes by guiding action and decision making. Policy is an umbrella term that refers to various regulatory measures, including laws, statutes, policies, regulations, and rules. These terms vary based on the jurisdiction and legal authority of the individual or group who established the policy. In the United States, K–12 education policy, which includes school bullying policy, can be established at the federal, state, and local levels ( Mead, 2009 ).

One advantage of policy interventions for bullying is that they can influence student, teacher, and administrator behavior as well as school organizational practices. For example, school bullying policies typically prohibit certain behaviors, such as threatening and harassing other students or retaliating against students who witness and then report bullying incidents. Policies may also require behaviors, such as requiring teachers to report bullying incidents to administrators and requiring administrators to investigate reports of bullying. Further, policies may promote certain behaviors by explicitly stating positive behavioral expectations for students or discourage behaviors by explicitly stating punishments associated with aggressive behaviors. At the school level, policies can guide organizational practices, such as establishing bullying incident reporting procedures and creating school-safety teams tasked with developing and executing school-safety plans. Thus, bullying policies can influence individual and organizational behaviors.

Another advantage of bullying policies is that they are upstream interventions that provide a foundation for downstream interventions. In other words, policies are systems-level interventions that typically require more targeted intervention programs, practices, and services at the organizational, group, and individual levels ( McKinlay, 1998 ). For example, a bullying policy may be adopted within a state or district; the policy then applies to all schools within the state or district. This policy may require training all school employees on bullying prevention strategies, integrating bullying awareness and education into classroom lessons and curricula, and providing counseling for students involved in bullying. Thus, policy lays the groundwork for an array of more specific and targeted interventions to be deployed in schools by outlining goals and directives in the policy document.

Policy design is important because the content influences a cascade of actions throughout school systems, which may result in positive or negative outcomes. For example, a bullying policy that requires schools to provide counseling services and positive behavioral reinforcement to students who perpetrate bullying is markedly different than a policy that requires schools to suspend or expel students who have carried out multiple acts of bullying. Research shows that overly harsh and punitive policies (e.g., “three strikes and you’re out” policies or “zero-tolerance” policies) are not effective at reducing aggression or improving school safety ( American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force, 2008 ). Thus, bullying policies should be crafted and revised using evidence-based strategies.

Anti-bullying laws have been enacted in a number of countries, including Canada, the Philippines, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Although the United States does not have a federal law against school bullying currently, all states have enacted anti-bullying laws ( U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015 ). The content of these laws was reviewed in a U.S. Department of Education report, which shows some consistency but also variability in the inclusion of policy components (see Table 1 ; Stuart-Cassel, Bell, & Springer, 2011 ). These state laws apply to approximately 98,000 K–12 public schools and have a goal of protecting more than 50 million students from involvement in bullying ( Snyder & Dillow, 2013 ; Stuart-Cassel et al., 2011 ).

Percentage of State Anti-Bullying Laws That Included Key Policy Components Identified by the U.S. Department of Education

| Policy Component | % |

|---|---|

| Purpose of the policy | 85 |

| Applicability or scope of the policy | 96 |

| Prohibition of bullying behaviors | 94 |

| Enumeration of protected social classes or statuses | 37 |

| Requirement for districts to implement policies | 98 |

| Review of district policies by the state | 43 |

| Definition of bullying behaviors prohibited | 63 |

| Procedure for reporting bullying incidents | 78 |

| Procedure for investigating bullying incidents | 67 |

| Procedure for maintaining records of bullying incidents | 39 |

| Consequences for bullying perpetrators | 91 |

| Mental health services for victims and/or perpetrators | 28 |

| Communication of the policy to students, parents, and employees | 91 |

| Training for school personnel on bullying intervention and prevention | 85 |

| Data collection and monitoring bullying of incidents | 39 |

| Assurance of right to pursue legal remedies for victims | 39 |

Note. The percentages are based on 46 state bullying laws passed between 1999 and 2011.

Source: Stuart-Cassel, Bell, & Springer, 2011 .

Despite the widespread adoption and application of anti-bullying policies within the United States and in other countries, relatively few studies have examined the effectiveness of these interventions. Instead, research has focused on programmatic interventions (e.g., Cool Kids Program, Fear Not!, Friendly Schools, KiVa, and Steps to Respect). Numerous systematic or meta-analytic reviews have been completed on the effectiveness of programmatic interventions for school bullying (e.g., Baldry & Farrington, 2007 ; Evans, Fraser, & Cotter, 2014 ; Ferguson, San Miguel, Kilburn, & Sanchez, 2007 ; Lee, Kim, & Kim, 2013 ; Merrell, Gueldner, Ross, & Isava, 2008 ; Ttofi & Farrington, 2011 ). However, a systematic review of the literature on the effectiveness of policy interventions for school bullying has not been completed.

Given the proportion of students directly or indirectly involved in bullying, the array of educational and psychological problems associated with bullying, the extensive adoption of anti-bullying policies, and the absence of a review of the research on these policy interventions, the need for a systematic review on this topic is imperative. The following questions drove this review: Are school policies effective in reducing or preventing bullying behavior among students? What is the state or quality of the research on school bullying policy effectiveness? What additional research is needed on school bullying policy effectiveness? Given these questions, the objectives of this review were threefold: to systematically identify, examine, and evaluate the methodological characteristics of studies investigating the effectiveness of school bullying policies; to summarize the substantive findings from these studies; and to provide recommendations for future research.

In preparation of this review, the author adhered to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) criteria ( Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009 ). Before undertaking the search for relevant studies, the author developed protocols for bibliographic database searches, study inclusion and exclusion criteria, and a data extraction tool. In addition, this review was registered with PROSPERO, an international database of systematic reviews regarding health and social well-being.

Search Procedure

A behavioral and social sciences librarian was consulted to assist with developing a search string and identifying relevant computerized bibliographic databases in which to search. The following search string was used to search all databases for studies published between January 1, 1995, and November 8, 2014: school AND bullying AND (law OR policy OR policies OR legislation OR statute) AND (effect OR effects OR effectiveness OR efficacy OR impact OR influence). The search of multiple databases increased the likelihood of identifying all possible studies falling within the scope of the review; thus, the author searched 11 databases, some of which included gray literature sources (e.g., conference papers, government reports, and unpublished papers). Searches were performed in the following databases via EBSCO using terms searched within the abstracts: CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Educational Full Text, ERIC (Education Research Information Center), PsycINFO, and Social Work Abstracts. The following databases were searched via ProQuest using terms searched within the titles, abstracts, and subject headings: ASSIA (Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts), Dissertations & Theses Full Text, and Social Services Abstracts. In addition, the Conference Proceedings Citations Index was searched using terms searched within titles, abstracts, and keywords. Finally, PubMed was searched using terms searched within titles and abstracts. These more formal bibliographic database searches were supplemented with internet searches using Google Scholar.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included in the review if they met the following criteria: (a) collected data and reported results on the effectiveness of policy interventions for bullying in school settings; (b) written in English; and (c) completed since January 1, 1995. Policy interventions for bullying were defined as statutes, policies, regulations, or rules established at the national, state, district, or school levels with the goal of reducing bullying in K–12 schools. Effectiveness referred to the extent to which a policy intervention prevented or reduced student bullying behavior. Given that school bullying policy is a nascent area of empirical inquiry with relatively few empirical investigations and evaluations, the author did not use stringent exclusion criteria in terms of study designs and methods. Only studies written in English were included due to the researchers’ language proficiency. Finally, the time period selected allowed for a comprehensive and contemporary review of the empirical literature completed in this area over the past 20 years.

Study Screening

After performing the bibliographic database searches, 481 results were imported into the RefWorks program to assist with organization and duplicate removal. Following duplicate removal, 414 studies remained. An additional 8 studies were added from Google Scholar searches that were not present among the 414 studies. The author and a trained research assistant independently screened each of the 422 studies to determine eligibility. A checklist of the inclusion criteria was created prior to the search and was used for eligibility assessment. Studies had to meet all three inclusion criteria to be screened in. Most studies were included or excluded after reading the title and abstract; however, it was also necessary to examine the full source document of some studies to determine eligibility. To examine interrater agreement, the decisions of the two screeners were compared, and Cohen’s kappa was calculated with SPSS (Version 21), which showed excellent agreement: kappa=0.97, p < .05 ( Landis & Koch, 1977 ). There were only six disagreements between the screeners, which were resolved by the author examining the source documents. After screening, 401 studies were excluded because they did not meet all of the inclusion criteria. The most common reasons for exclusion included papers that were not empirical, lack of evaluation of effectiveness, lack of evaluation of policy, and studies that were not conducted in schools. After completing the search and screening processes, 21 studies were included for extraction and review ( Figure 1 ).

Flow diagram depicting the identification, screening, and inclusion of studies.

Data Extraction

A data extraction sheet was developed to assist with identifying and collecting relevant information from the 21 included studies. Information extracted included the citation, purpose of the study, study design, sampling strategy and location, response rate, sample size and characteristics, measurement of relevant variables, analyses performed, and results and findings. The author extracted this information and a research assistant then compared the completed extraction sheets with the source documents to assess the accuracy of the extractions. There were only six points of disagreement between the extractor and checker, which they then resolved together by examining the source documents and extractions simultaneously.

Data Synthesis

Initial review of the included studies revealed that a quantitative synthesis, such as a meta-analysis, was not advisable due to the methodological heterogeneity of the studies and differences in approaches to evaluating policy effectiveness. Thus, a narrative thematic synthesis approach was used ( Thomas, Harden, & Newman, 2012 ). The substantive findings on policy effectiveness were first categorized based on the outcome evaluated and then synthesized within each category.

A total of 21 studies were included in this review: 9 peer-reviewed journal articles, 6 research reports that were not peer-reviewed, 5 doctoral dissertations, and 1 master’s thesis. A summary of the methodological characteristics of these studies is presented—including a synthesis of the substantive findings regarding the effectiveness of school bullying policies—in Table S1 (available online).

Methodological Characteristics of the Studies

Of the 21 studies, 12 (57%) used mixed methods, 8 (38%) used quantitative methods, and 1 (5%) used qualitative methods. All studies relied on cross-sectional designs. Most studies (65%) used convenience sampling, whereas the remaining studies used some form of probability sampling. More than half (57%) of studies used national samples, whereas 24% used samples from a single city or local region, 15% used statewide samples, and 5% used samples from areas in multiple countries. Over 80% of studies sampled participants in the United States, with other studies drawing participants from Europe, Australia, East Asia, and Southwest Asia. The most common recruitment sites were schools, followed by listservs, websites, community groups or organizations, professional associations, and personal contacts. Most studies reported participant response rates which varied from 21% to 98%, and the average response rate across studies was 57% ( SD = 29%). Eight studies did not report response rates.

Across studies, sample sizes varied from 6 to 8,584 participants. Only the qualitative study had fewer than 50 participants, and two studies had between 50 and 100 participants. Most studies had relatively large samples with more than 500 respondents. The most commonly used participants were students, followed by teachers. Other respondents included administrators, school psychologists, school counselors, education support professionals, and parents. About one third of studies included multiple participant groups (e.g., students and teachers). Most studies (62%) recruited participants from K–12 settings, whereas other studies recruited participants from a single school level: elementary, middle, or high school. Among adult participants, about 75% were female and 90% were White. These percentages are similar to those reported by the U.S. Department of Education, which show that 76% of teachers are female and 82% are White ( Snyder & Dillow, 2013 ).

Samples of students were diverse in terms of race/ethnicity, with most studies consisting of about two-thirds White participants as well as Black, Hispanic/Latino/Latina, Asian, Native American Indian, Middle Eastern, and multiracial students. In addition, student samples were closer to having equal proportions of males and females. Five studies included student participants who were exclusively lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ), whereas 6 studies did not report information about student sexual orientation or gender identity. In addition, studies typically did not measure or report participant national origin, immigrant/citizenship status, religious identity, socioeconomic status, or ability/disability status. Finally, most students were high school students.

Evaluation methods

All studies relied on self-report data to evaluate school bullying policy effectiveness. However, studies varied based on the outcome used in their evaluations: Eight studies examined school members’ perceptions of policy effectiveness, 5 studies examined student bullying perpetration and/or victimization behaviors, 6 studies investigated anti-LGBTQ bullying victimization, and 2 studies considered educator intervention in bullying. The level of policies evaluated also varied: Eleven studies examined school-level policies, 3 studies examined district-level policies, 3 studies examined state laws, 3 studies examined both state laws and school-level policies, and one study examined a national policy.

Studies also varied in terms of the analytic approaches used to evaluate effectiveness: Nine studies used bivariate analyses, 8 studies used descriptive statistics of perceived effectiveness, 3 studies used multivariate analyses, and one study used both bivariate and multivariate analyses. Studies that used a bivariate analytic approach compared measures of teachers’ responsiveness to bullying or measures of student bullying between those in schools with and without anti-bullying policies or between schools with high- versus low-quality anti-bullying policies. In these studies, distinctions between high- and low-quality policies were made by the researchers in each study using content analyses of policy strategies that were theoretically and empirically associated with effectiveness in the bullying literature (e.g., having a definition of bullying, ensuring adult supervision of students, and outlining consequences for bullies; Ordonez, 2006 ; Woods & Wolke, 2003 ). Policy content analysis scores were then used to distinguish between high- and low-quality policies. Descriptive statistical analyses of effectiveness entailed participants responding to a single self-report item about their perceptions of policy effectiveness (e.g., “How effective do you feel that your school’s anti-bullying policy is in reducing bullying?”), with Likert-type response options related to agreement/disagreement or categorical response options (e.g., yes or no). Multivariate analytic approaches primarily used student bullying scores as the dependent variable and either a continuous anti-bullying policy score or a dichotomous variable indicating whether or not the school had an anti-bullying policy as the independent variable. Continuous school bullying policy scores were based on either a set of items about the perceived presence of an anti-bullying policy (e.g., “I think my school clearly set forth anti-bullying policies and rules”) or a content analysis of policy documents to identify the presence of criteria or strategies associated with effectiveness (e.g., having a definition of bullying, establishing procedures and consequences for bullies, having educational events about the school’s bullying guidelines, ensuring adult supervision in school areas prone to bullying, and formulating a school task group to coordinate anti-bullying efforts).

The measures used to assess bullying among students varied; some studies used established scales (e.g., Olweus Bullying Questionnaire), whereas other studies used items developed by the researchers. The number of items used to measure bullying varied from 3 to 23 ( M =18.2, SD =6.1). Of the 11 studies that measured bullying, the majority measured bullying victimization ( n = 8). Only 2 studies measured both bullying victimization and perpetration, and one study measured just perpetration. In terms of the types of bullying measured, 5 studies measured physical, verbal, social, electronic, and sexual bullying; 3 studies measured physical, verbal, and social bullying; one study measured physical, verbal, social, and electronic bullying; one study measured physical, verbal, social, and property bullying; and one study measured verbal bullying. In addition to student bullying, educators’ responsiveness to bullying was another outcome variable that was used in 8 studies. Only one study used a scale to measure educator responsiveness, and the remaining 7 studies used one to four items regarding educators responding to student bullying.

Results on Policy Effectiveness

Given that the 21 studies differed on the outcomes used in their evaluations of school bullying policy effectiveness, substantive results are presented by each outcome category: school members’ perceptions of policy effectiveness, student bullying perpetration and/or victimization, anti-LGBTQ bullying victimization, and educator intervention in bullying.

Perceptions of policy effectiveness

Eight studies reported results on participants’ perceptions of policy effectiveness. Results showed that 5% to 88%( M =49.4%, SD = 33.4%) of educators perceived school bullying policies to be effective to some degree, 4% to 79% ( M =24.5%, SD =23.6%) of educators perceived policies to be ineffective , and 16% to 70% ( M =51.3%, SD =30.6%) of educators were uncertain about policy effectiveness ( Barnes, 2010 ; Bradshaw, Waasdorp, O’Brennan, & Gulemetova, 2013 ; Hedwall, 2006 ; Isom, 2014 ; Sherer & Nickerson, 2010 ; Terry, 2010 ). Only one study measured students’ perceptions of policy effectiveness, and results showed that they perceived policies to be moderately effective ( Ju, 2012 ). In addition, only one of the 21 studies collected multiple waves of data, although different sets of respondents were used at each of the two waves ( Samara & Smith, 2008 ). In this study, researchers examined perceived effectiveness before and after the passage of an anti-bullying policy; however, there were no significant changes in perceived effectiveness.

Student bullying perpetration and victimization

Five studies reported findings on the influence of policy on general student bullying outcomes. Two of these 5 studies examined policy content in relation to effectiveness. One study found that students in schools with high-quality bullying policies reported lower rates of verbal and physical bullying victimization than students in schools with low-quality policies; however, no differences were found for social/relational or property bullying victimization ( Ordonez, 2006 ). In this study, policy quality was evaluated based on the inclusion of the following elements: a definition of bullying; procedures and consequences for bullies; plans for disseminating the policy to students, school personnel, and parents; programs or practices that encourage acceptance of diversity, empathy for others, respect toward others, peer integration, and responsible use of power; supervision of students in school areas prone to bullying (e.g., playground, cafeteria, and hallways); and socio-emotional skills training for victims and bullies ( Ordonez, 2006 ). Similarly, another study found lower rates of verbal, physical, and property bullying victimization among students in schools with high-quality bullying policies, yet higher rates of social/relational bullying perpetration ( Woods & Wolke, 2003 ). In this study, policy quality was evaluated based on the inclusion of the following elements: a definition of bullying; recognition of negative outcomes associated with bullying; discussion of locations where bullying can occur; evaluation of the prevalence of bullying; involvement of stakeholders in policy development; supervision of students in school areas; formulation of a school task group to coordinate anti-bullying efforts; classroom rules about bullying; classroom sessions about bullying; discussion of bullying at PTA/PTO meetings; involvement of parents in bullying prevention efforts; and follow-up with victims and bullies after incidents ( Woods & Wolke, 2003 ).

Other studies examined associations between policy presence and bullying outcomes. Three significant or marginally significant ( p ≤ .095) associations were found: the presence of an anti-bullying policy was inversely related to general bullying victimization, social/relational bullying perpetration, and verbal bullying perpetration ( Farrington & Ttofi, 2009 ; Lee, 2007 ). Conversely, eight nonsignificant associations were found between school bullying policy presence and scores of general, physical, verbal, and social/relational bullying perpetration, as well as physical, verbal, and social/relational bullying victimization ( Farrington & Ttofi, 2009 ; Khoury-Kassabri, 2011 ; Lee, 2007 ). In addition, having a bullying policy was not associated with increases in general bullying perpetration or victimization ( Farrington & Ttofi, 2009 ).

Anti-LGBTQ bullying

Six studies with rather large samples of primarily LGBTQ students consistently found that compared to students in schools without an anti-bullying policy or with an anti-bullying policy that did not explicitly prohibit bullying based on sexual orientation and gender identity, students in schools with comprehensive anti-bullying policies that included protections based on sexual orientation and gender identity reported lower rates of anti-LGBTQ bullying, more school personnel frequently intervening when anti-LGBTQ comments were made in their presence, and more school personnel being effective in their anti-LGBTQ bullying responses ( Kosciw&Diaz, 2006 ; Kosciw, Diaz,&Greytak, 2008 ; Kosciw, Greytak, Diaz, & Bartkiewicz, 2010 ; Kosciw, Greytak, Bartkiewicz, Boesen, & Palmer, 2012 ; Kosciw, Greytak, Palmer, & Boesen, 2014 ; Phoenix et al., 2006 ). These differences were consistent in analyses of both local anti-bullying policies and state anti-bullying laws.

Educator intervention in bullying

Educators play a key role in reducing bullying behavior among students. One study found that compared to those in schools without a bullying policy, educators in schools with bullying policies were more likely to enlist the help of parents and colleagues in responding to a bullying incident and were less likely to ignore bullying ( Bauman, Rigby, & Hoppa, 2008 ). Conversely, a large, national study of educators found no relationship between having an anti-bullying policy and educators’ comfort intervening in both general and discriminatory bullying ( O’Brennan, Waasdorp, & Bradshaw, 2014 ).

The findings are discussed according to the research questions that drove the review.

Are Policies Effective at Reducing Bullying?

Educators were divided in their perceptions of the effectiveness of policies for school bullying; however, on average, about twice as many educators reported that policies were effective to some degree as those who reported that they were not effective. Nonetheless, descriptive summaries of perceptions of effectiveness are typically not viewed as compelling sources of evidence for the effectiveness of an intervention ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2003 ). However, educators are considered key informants who know what goes on in schools.