An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Five Things About Juvenile Delinquency Intervention and Treatment

Juvenile delinquency intervention and treatment programs have the broad goals of preventing crime and reducing recidivism by providing treatment and services to youth who have committed crimes.

The five statements below are based on practices and programs rated by CrimeSolutions. [1]

1. Juvenile awareness programs may be ineffective and potentially harmful.

Juvenile awareness programs — like Scared Straight — involve organized visits to adult prison facilities for adjudicated youth and youth at risk of adjudication. Based on the review and rating by CrimeSolutions of two meta-analyses of existing research , youth participating in these types of programs were more likely to commit offenses in the future than adjudicated youth and youth at risk of adjudication who did not. Consequently, recidivism rates were, on average, higher for participants compared to juveniles who went through regular case processing.

The results suggest that not only are juvenile awareness programs ineffective at deterring youth from committing crimes, but youth exposed to them are more likely to commit offenses in the future.

Read the practice profile Juvenile Awareness Programs (Scared Straight) to learn more.

2. Cognitive behavioral therapy can effectively reduce aggression in children and adolescents.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a problem-focused, therapeutic approach that attempts to help people identify and change the dysfunctional beliefs, thoughts, and patterns that contribute to their problem behaviors. CBT programs are delivered in various settings, including juvenile detention facilities. Based on the review and rating by CrimeSolutions of two meta-analyses of existing research , a variant of CBT focused specifically on children and adolescents who have anger-related problems is effective for reducing aggression and anger expression, and for improving self-control, problem-solving, and social competencies.

Read the practice profile Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anger-Related Problems in Children and Adolescents to learn more.

3. Multisystemic therapy for juveniles reduces recidivism, rearrests, and the total number of days incarcerated.

Multisystemic therapy is a family- and community-based treatment program for adolescents with criminal offense histories and serious antisocial, delinquent, and other problem behaviors. Based on the review and rating by CrimeSolutions of three randomized controlled trials (each evaluating a program in a different state), the program effectively reduced rearrests and number of days incarcerated.

Read the program profile Multisystemic Therapy to learn more.

4. Intensive supervision of juveniles — the conditions of which may vary — has not been found to reduce recidivism.

This practice consists of increased supervision and control of youth on probation in the community, compared with those on traditional community supervision. Intensive supervision programs have three primary features: 1) smaller caseloads for juvenile probation officers, 2) more frequent face-to-face contacts, and 3) strict conditions of compliance with stiffer penalties for violations. Other conditions may vary, but they can include electronic monitoring, drug/urinalysis testing, and participation in programming (such as tutoring, counseling, or job training). Based on the review and rating by CrimeSolutions of three meta-analyses of existing research , the practice does not reduce recidivism.

Read the practice profile Juvenile Intensive Supervision Programs to learn more.

5. Incarceration-based therapeutic communities for juveniles with substance use disorders have not been found to reduce recidivism after release.

Incarceration-based therapeutic communities employ a comprehensive, residential drug-treatment program model for youth in a detention facility who have substance use disorders. Therapeutic communities are designed to foster changes in attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors related to substance use and to reduce subsequent criminal offending. Based on the review and rating by CrimeSolutions of two meta-analyses of existing research , incarceration-based therapeutic communities have not been found to reduce recidivism after release for those who participate.

Read the practice profile Incarceration-Based Therapeutic Communities for Juveniles to learn more.

[note 1] As defined by CrimeSolutions, a practice is a general category of programs, strategies, or procedures that share similar characteristics with regard to the issues they address and how they address them. Practice profiles tell us about the average results from multiple evaluations of similar programs, strategies, or procedures. A program is a specific set of activities carried out according to guidelines to achieve a defined purpose. Program profiles on CrimeSolutions tell us whether a specific program was found to achieve its goals when it was carefully evaluated.

Practice ratings do not take into account variations in implementation or other program-specific factors which may impact the effectiveness of a specific program. Practices may be rated differently on outcomes not included here.

CrimeSolutions helps practitioners and policymakers understand what works in justice-related programs and practices. CrimeSolutions is funded by the National Institute of Justice and the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP). Programs and practices profiles related to juveniles also appear on OJJDP’s Model Programs Guide .

Cite this Article

Read more about:, nij's "five things" series.

Find more titles in NIJ's "Five Things" series .

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Risk and protective factors and interventions for reducing juvenile delinquency: a systematic review.

1. Introduction

2. materials and methods, 2.1. inclusion criteria, 2.2. exclusion criteria, 2.3. data sources and search strategy, 2.4. risk of bias assessment, 4. discussion, 5. limitations, 6. conclusions, author contributions, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- Aksnes, Dag W., and Gunnar Sivertsen. 2019. A Criteria-based Assessment of the Coverage of Scopus and Web of Science. Journal of Data and Information Science 4: 1–21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Amani, Bita, Norweeta G. Milburn, Susana Lopez, Angela Young-Brinn, Lourdes Castro, Alex Lee, and Eraka Bath. 2018. Families and the juvenile justice system: Considerations for family-based interventions. Family & Community Health 41: 55–63. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Anderson, Valerie R., and Brinn M. Walerych. 2019. Contextualizing the nature of trauma in the juvenile justice trajectories of girls. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community 47: 138–53. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson, Valerie R., Laura L. Rubino, and Nicole C. McKenna. 2021. Family-based Intervention for Legal System-involved Girls: A Mixed Methods Evaluation. American Journal of Community Psychology 67: 35–49. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Arias-Pujol, Eulàlia, and M. Teresa Anguera. 2017. Observation of interactions in adolescent group therapy: A mixed methods study. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1188. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Barnert, Elizabeth S., Rebecca Dudovitz, Bergen B. Nelson, Tumaini R. Coker, Christopher Biely, Ning Li, and Paul J. Chung. 2017. How does incarcerating young people affect their adult health outcomes? Pediatrics 139: e20162624. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Barrett, James G., and Elizabeth Janopaul-Naylor. 2016. Description of a collaborative community approach to impacting juvenile arrests. Psychological Services 13: 133–39. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Borduin, Charles M., Lauren B. Quetsch, Benjamin D. Johnides, and Alex R. Dopp. 2021. Long-term effects of multisystemic therapy for problem sexual behaviors: A 24.9-year follow-up to a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 89: 393–405. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bright, Charlotte Lyn, Sarah Hurley, and Richard P. Barth. 2014. Gender differences in outcomes of juvenile court-involved youth following intensive in-home services. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 5: 23–44. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Buchanan, Molly, Erin D. Castro, Mackenzie Kushner, and Marvin D. Krohn. 2020. It’s F** ing Chaos: COVID-19’s impact on juvenile delinquency and juvenile justice. American Journal of Criminal Justice 45: 578–600. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Campbell, Mhairi, Joanne E. McKenzie, Amanda Sowden, Srinivasa Vittal Katikireddi, Sue E. Brennan, Simon Ellis, Jamie Hartmann-Boyce, Rebecca Ryan, Sasha Shepperd, and James Thomas. 2020. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. BMJ 368: l6890. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Cavanagh, Caitlin, and Elizabeth Cauffman. 2017. The longitudinal association of relationship quality and reoffending among first-time juvenile offenders and their mothers. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 46: 1533–46. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Costello, Barbara J., and John H. Laub. 2020. Social Control Theory: The Legacy of Travis Hirschi’s Causes of Delinquency . Annual Review of Criminology 3: 21–41. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- D.C. Department of Human Services. n.d. Functional Family Therapy (FFT). Available online: https://dhs.dc.gov/page/functional-family-therapy-fft#:~:text=Functional%20Family%20Therapy%20(FFT)%20is,relational%2C%20family-based%20perspective (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- D’Agostino, Emily, Stacy L. Frazier, Eric Hansen, Maria I. Nardi, and Sarah E. Messiah. 2020. Association of a park-based violence prevention and mental health promotion after-school program with youth arrest rates. JAMA Network Open 3: e1919996. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dakof, Gayle A., Craig E. Henderson, Cynthia L. Rowe, Maya Boustani, Paul E. Greenbaum, Wei Wang, Samuel Hawes, Clarisa Linares, and Howard A. Liddle. 2015. A randomized clinical trial of family therapy in juvenile drug court. Journal of Family Psychology 29: 232–41. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dodson, Lisa. 2013. Stereotyping low-wage mothers who have work and family conflicts. Journal of Social Issues 69: 257–78. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ezell, Jerel M., Margaret Richardson, Samira Salari, and James A. Henry. 2018. Implementing trauma-informed practice in juvenile justice systems: What can courts learn from child welfare interventions? Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 11: 507–19. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gan, Daniel Z. Q., Yiwei Zhou, Eric Hoo, Dominic Chong, and Chi Meng Chu. 2019. The Implementation of Functional Family Therapy (FFT) as an Intervention for Youth Probationers in Singapore. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 45: 684–98. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Garduno, L. Sergio. 2022. How Influential are Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) on Youths?: Analyzing the Immediate and Lagged Effect of ACEs on Deviant Behaviors. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 15: 683–700. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gearhart, Michael C., and Riley Tucker. 2020. Criminogenic risk, criminogenic need, collective efficacy, and juvenile delinquency. Criminal Justice and Behavior 47: 1116–35. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Halgunseth, Linda C., Daniel F. Perkins, Melissa A. Lippold, and Robert L. Nix. 2013. Delinquent-oriented attitudes mediate the relation between parental inconsistent discipline and early adolescent behavior. Journal of Family Psychology 27: 293–302. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Henggeler, Scott W., Michael R. McCart, Phillippe B. Cunningham, and Jason E. Chapman. 2012. Enhancing the effectiveness of juvenile drug courts by integrating evidence-based practices. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 80: 264–75. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Higgins, Julian, James Thomas, Jacqueline Chandler, Miranda Cumpston, Tianjing Li, Matthew Page, and Vivian Welch, eds. 2022. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions . Version 6.4. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoeve, Machteld, Geert Jan J. M. Stams, Claudia E. Van der Put, Judith Semon Dubas, Peter H. Van der Laan, and Jan R. M. Gerris. 2012. A meta-analysis of attachment to parents and delinquency. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 40: 771–85. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hogue, Aaron, Sarah Dauber, Jessica Samuolis, and Howard A. Liddle. 2006. Treatment techniques and outcomes in multidimensional family therapy for adolescent behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology 20: 535. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Karam, Eli A., Emma M. Sterrett, and Lynn Kiaer. 2017. The integration of family and group therapy as an alternative to juvenile incarceration: A quasi-experimental evaluation using Parenting with Love and Limits. Family Process 56: 331–47. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lantos, Hannah, Andra Wilkinson, Hannah Winslow, and Tyler McDaniel. 2019. Describing associations between child maltreatment frequency and the frequency and timing of subsequent delinquent or criminal behaviors across development: Variation by sex, sexual orientation, and race. BMC Public Health 19: 1306. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Leve, Leslie D., Patricia Chamberlain, and Hyoun K. Kim. 2015. Risks, outcomes, and evidence-based interventions for girls in the US juvenile justice system. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 18: 252–79. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lippold, Melissa A., Andrea Hussong, Gregory M. Fosco, and Nilam Ram. 2018. Lability in the parent’s hostility and warmth toward their adolescent: Linkages to youth delinquency and substance use. Developmental Psychology 54: 348–61. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Logan-Greene, Patricia, and Annette Semanchin Jones. 2015. Chronic neglect and aggression/delinquency: A longitudinal examination. Child Abuse & Neglect 45: 9–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Logan-Greene, Patricia, B. K. Elizabeth Kim, and Paula S. Nurius. 2020. Adversity profiles among court-involved youth: Translating system data into trauma-responsive programming. Child Abuse & Neglect 104: 104465. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- May, Jessica, Kristina Osmond, and Stephen Billick. 2014. Juvenile delinquency treatment and prevention: A literature review. Psychiatric Quarterly 85: 295–301. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Douglas G. Altman, and PRISMA Group. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 151: 264–69. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Mowen, Thomas J., and John H. Boman. 2018. A developmental perspective on reentry: Understanding the causes and consequences of family conflict and peer delinquency during adolescence and emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 47: 275–89. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP). 2020. OJJDP Statistical Briefing Book. Updated 8 July. Available online: https://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/crime/qa05101.asp (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, and Sue E. Brennan. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery 88: 105906. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Perron, Susannah. 2013. Family Attachment, Family Conflict, and Delinquency in a Sample of Rural Youth. Doctoral dissertation, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, USA. [ Google Scholar ]

- Petry, Nancy M., Sheila M. Alessi, Todd A. Olmstead, Carla J. Rash, and Kristyn Zajac. 2017. Contingency management treatment for substance use disorders: How far has it come, and where does it need to go? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 31: 897. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Puzzanchera, Charles. 2022. Trends in Youth Arrests for Violent Crimes. In Juvenile Justice Statistics: National Report Series Fact Sheet . Available online: https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/publications/trends-in-youth-arrests.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Robst, John, Mary Armstrong, and Norin Dollard. 2017. The association between type of out-of-home mental health treatment and juvenile justice recidivism for youth with trauma exposure. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health 27: 501–13. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ruch, Donna A., and Jamie R. Yoder. 2018. The effects of family contact on community reentry plans among incarcerated youths. Victims & Offenders 13: 609–27. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ryan, Joseph P. 2012. Substitute care in child welfare and the risk of arrest: Does the reason for placement matter? Child Maltreatment 17: 164–71. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ryan, Joseph P., Abigail B. Williams, and Mark E. Courtney. 2013. Adolescent neglect, juvenile delinquency and the risk of recidivism. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 42: 454–65. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sanders, Courtney. 2021. State Juvenile Justice Reforms Can Boost Opportunity, Particularly for Communities of Color. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Available online: https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-juvenile-justice-reforms-can-boost-opportunity-particularly-for (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Sitnick, Stephanie L., Daniel S. Shaw, Chelsea M. Weaver, Elizabeth C. Shelleby, Daniel E. Choe, Julia D. Reuben, Mary Gilliam, Emily B. Winslow, and Lindsay Taraban. 2017. Early childhood predictors of severe youth violence in low-income male adolescents. Child Development 88: 27–40. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Strathearn, Lane, Michele Giannotti, Ryan Mills, Steve Kisely, Jake Najman, and Amanuel Abajobir. 2020. Long-term cognitive, psychological, and health outcomes associated with child abuse and neglect. Pediatrics 146: e20200438. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- The PEW Charitable Trusts. 2014. Public Opinion on Juvenile Justice in America. Available online: https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2015/08/pspp_juvenile_poll_web.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Trinkner, Rick, Ellen S. Cohn, Cesar J. Rebellon, and Karen Van Gundy. 2012. Don’t trust anyone over 30: Parental legitimacy as a mediator between parenting style and changes in delinquent behavior over time. Journal of Adolescence 35: 119–32. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Triplett, Ruth. 2007. Social learning theory of crime. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology . Malden: Blackwell. [ Google Scholar ]

- U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs. 2012. Program Profile: Multidimensional Family Therapy (MDFT). Updated 6 May. Available online: https://crimesolutions.ojp.gov/ratedprograms/267#:~:text=Multidimensional%20Family%20Therapy%20(MDFT)%20is,%2C%20and%20other%20mental%20comorbidities (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Underwood, Lee A., and Aryssa Washington. 2016. Mental illness and juvenile offenders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 13: 228–42. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Vidal, Sarah, Christine M. Steeger, Colleen Caron, Leanne Lasher, and Christian M. Connell. 2017. Placement and delinquency outcomes among system-involved youth referred to multisystemic therapy: A propensity score matching analysis. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 44: 853–66. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Walker, Sarah C., Mylien Duong, Christopher Hayes, Lucy Berliner, Leslie D. Leve, David C. Atkins, Jerald R. Herting, Asia S. Bishop, and Esteban Valencia. 2019. A tailored cognitive behavioral program for juvenile justice-referred females at risk of substance use and delinquency: A pilot quasi-experimental trial. PLoS ONE 14: e0224363. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- White, Stuart F., Paul J. Frick, Kathryn Lawing, and Daliah Bauer. 2013. Callous–unemotional traits and response to Functional Family Therapy in adolescent offenders. Behavioral Sciences & the Law 31: 271–85. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wiatrowski, Michael D., and Mary K. Swatko. 1979. Social Control Theory and Delinquency—A Multivariate Test. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/social-control-theory-and-delinquency-multivariate-test#:~:text=Hirschi’s%20social%20control%20theory%20suggests,in%20social%20rules%20and%20convention (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Wilkinson, Andra, Hannah Lantos, Tyler McDaniel, and Hannah Winslow. 2019. Disrupting the link between maltreatment and delinquency: How school, family, and community factors can be protective. BMC Public Health 19: 588. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Young, Joanna Cahall, and Cathy Spatz Widom. 2014. Long-term effects of child abuse and neglect on emotion processing in adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect 38: 1369–81. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zajac, Kristyn, Jeff Randall, and Cynthia Cupit Swenson. 2015. Multisystemic therapy for externalizing youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics 24: 601–16. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| Criteria | Notes |

|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria | |

| Participants | - Any studies that sampled families, parents, guardians, or siblings or examined factors at the household level (familial dynamics). - Any studies that examined factors or attributes that reduce the risk of recidivism or delinquency or factors that could be targeted for interventions (mitigating factors). - Any studies that examined household-level strategies, programs, or interventions aimed at preventing or reducing recidivism and delinquency, including those that extend into the broader community, and their impacts on juvenile delinquency and recidivism (family-based interventions). |

| Intervention | The focus of the study was family-based interventions. - Any studies that examined household-level strategies, programs, or interventions aimed at preventing or reducing recidivism and delinquency |

| Comparators | Any studies with any comparator included. |

| Outcomes | We included any studies of interventions meeting the above criteria to determine the proportion that reported engagement outcomes |

| Study design | Observational, experimental, qualitative, and quantitative studies that met these criteria and did not meet any exclusion criteria were included in the review. |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| Participants | - Studies included conduct disorder, internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and substance abuse. - Studies that focused on the siblings or parents of juvenile offenders and on justice system, welfare system, or court policies—as opposed to the use of family interventions within these systems or risk and mitigating factors of individuals involved with these systems—were determined to be outside of the scope of this review. |

| Intervention | Interventions with a primary focus other than family-based interventions. |

| Study design | Systematic reviews, literature reviews, and meta-analyses |

| Electronic Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| Scopus | (“juvenile delinquency” OR “juvenile crime”) AND ((“family intervention”)) AND (psychological) OR (mental AND health) OR (psychology) OR (police) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) |

| PubMed | (((Juvenile delinquency) AND (family intervention OR family OR “family-based”)) AND (psychological OR mental OR psychology OR “mental health”)) AND (crime OR police) |

| Study | Study Population | Outcome(s) Measured | Principal Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| ( ) | Middle and high school students in New Hampshire participating in the New Hampshire Youth Study from 2007–2009 (n = 596) | Delinquency and parental legitimacy | Authoritative parenting is positively and authoritarian parenting is negatively associated with parental legitimacy. Parental legitimacy reduces the likelihood of future delinquency. |

| ( ) | Low-income males living in an urban community followed from ages 18 months through adolescence (15–18 years) (n = 310) | Juvenile petitions from juvenile court records | Early-childhood individual and family factors (such as harsh parenting and poor emotional regulation) can discriminate between adolescent violent offenders and nonoffenders or nonviolent offenders. |

| ( ) | Early adolescents in two-parent homes and their parents (n = 618) in Iowa and Pennsylvania. PROSPER study | Youth substance use and delinquency in 9th grade | Changes in the parent–youth relationship, such as decreased parental warmth and increased hostility during adolescence, were associated with increased delinquency, especially for girls. |

| ( ) | Male youth (under age 18) and “youthful offenders” (under age 25 and incarcerated under “Youthful Offender” laws) across Colorado, Florida, Kansas, and South Carolina (n = 337) Serious and Violent Offender Reentry Initiative youth sample collected 2005–2007 | Crime and substance use | Family conflict is a major driver of recidivism through its direct impact on increasing crime and substance use and more reentry programs focused on reducing family conflict should be explored, such as multisystemic therapy. |

| ( ) | Qualitative study; Juvenile court officers working with girls in the juvenile justice system (n = 24) | Extent and type of trauma experienced by girls in the juvenile justice system | In qualitative interviews, the officers discussed how exposure to trauma (violence at home, a dysfunctional home, etc.) influenced girls’ trajectory and contributed to many of their involvement with the juvenile justice system. |

| ( ) | Adolescents attending public middle or high school in Maryland receiving services from Identity, Inc. (n = 555) | Three deviant behaviors: stealing, fighting, and smoking marijuana | Experience of multiple adverse childhood experiences increased the likelihood of adolescents engaging in deviant behaviors. School connection, anger management skills, and parental supervision acted as protective factors. |

| ( ) | Youth ages 8–16 who had their first episode in a substitute child care welfare setting between 2000–2003 in the state of Washington (n = 5528) | Risk of justice involvement | Youth with behavioral problems were more likely to be placed in congregate care facilities and had little access to family-based services. High arrest rates among youth with behavioral problems indicated an ineffectiveness of the congregate care approach. |

| ( ) | Moderate and high-risk juvenile offenders who were screened for probation from 2004–2007 in Washington (n = 19,833) | Risk of subsequent offending (based on event history models) | Returning to an environment where one faced continued or ongoing neglect increased an individual’s risk of re-offending. |

| ( ) | Youth who were assessed at age 14 at one of the five study sites across the U.S. in the LONGSCAN consortium (n = 815) | Aggression and delinquency | Experiencing chronic neglect or chronic failure to provide from ages 0–12 was associated with increased aggression and delinquency at age 14. This relationship was mediated by social problems, especially for girls. |

| ( ) | Court staff across four rural juvenile courts in Michigan (n = 15) | Qualitative interviews on trauma-informed practice | Court staff widely supported trauma-informed practices like mental health referrals instead of—or in addition to—sentencing or punishment but faced challenges due to limited mental health resources and inadequate support from schools, government, and police. |

| ( ) | U.S. adolescents enrolled in grades 7–12 from 1994–95 (n = 10,613) National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health | Violent and nonviolent offending behavior | Experiences of maltreatment were associated with more rapid increases in both non-violent and violent offending behaviors. |

| ( ) | U.S. adolescents enrolled in grades 7–12 from 1994–95 (n = 10,613) National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health | Violent and non-violent offending frequency | High-quality relationships with mother or father figures, school connection, and neighborhood collective efficacy were protective against violent offending (both for those experiencing and not experiencing maltreatment). |

| ( ) | Medium- to high-risk youth on probation (n = 5378) Washington State Juvenile Assessment | Self-regulation, mental health, substance use, academic functioning, family/social resources, and behavioral problems | Groups of individuals exposed to different adverse childhood experiences varied in terms of all six outcomes, suggesting a need for more differentiated treatment approaches applied early on to address these unique needs. |

| ( ) | Adolescents attending public middle or high school in Maryland receiving services from Identity, Inc. (n = 555) | Three deviant behaviors: stealing, fighting, and smoking marijuana | Experience of multiple adverse childhood experiences increased the likelihood of adolescents engaging in deviant behaviors. School connection, anger management skills, and parental supervision acted as protective factors. |

| ( ) | Youth ages 8–16 who had their first episode in a substitute child care welfare setting between 2000–2003 in the state of Washington (n = 5528) | Risk of justice involvement | Youth with behavioral problems were more likely to be placed in congregate care facilities and had little access to family-based services. High arrest rates among youth with behavioral problems indicated an ineffectiveness of the congregate care approach. |

| ( ) | Rural adolescents and their parents (n = 342 adolescents) in Iowa and Pennsylvania. 6-year PROSPER (PROmoting School-community-university Partnership to Enhance Resilience) study. | Delinquent-oriented attitudes, deviant behaviors (stealing, carrying a hidden weapon, etc.) | Inconsistent discipline at home may lead adolescents to develop accepting attitudes toward delinquency, which may contribute to future antisocial and deviant behaviors. |

| ( ) | Low- to moderate-level male offenders ages 13–17 who participated in the Crossroads study of first-time juvenile offenders and their mothers conducted in California, Louisiana, and Pennsylvania (n = 634, or 317 mother–son pairs) | Re-offending | Strong mother–son relationships can serve as a protective factor against youth’s re-offending, especially for older youth. |

| ( ) | Youth involved with the Florida juvenile justice system from July 2002–June 2008 with records of ‘severe emotional disturbance’ and an out-of-home placement following arrest (n = 1511) | Re-arrest during a 12-month period | Severe trauma history increased the likelihood of re-arrest relative to less severe or no trauma history. Among those with severe trauma history, those placed in foster homes had the lowest rates of recidivism compared to other out-of-home placements. |

| ( ) | 10–20-year-old youth in custody in the U.S. (n = 7073) Survey of Youth in Residential Placement | Likelihood of having a plan for education and employment after reentry | Family contact during incarceration increased the likelihood that youth had educational and employment reentry plans. |

| ( ) | U.S. adolescents enrolled in grades 7–12 from 1994–95 (n = 10,613) National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health | Violent and non-violent offending frequency | High quality mother or father relationships, school connections, and neighborhood collective efficacy were protective against violent offending (both for those experiencing and not experiencing maltreatment). |

| ( ) | Mothers with children of at least 13 years of age and born in 20 select U.S. cities (n = 3444 families) Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study | Self-reported juvenile delinquency | Individual-level factors are stronger predictors of self-reported juvenile delinquency than collective efficacy. Mitigating factors include satisfaction with school, academic performance, and parental closeness. Risk factors include substance use, delinquent peers, impulsivity, and prior delinquency. |

| ( ) | Juvenile offenders ages 12–17 engaged in one of six juvenile drug courts participating in the study (n = 104) | Marijuana use and crime | The use of contingency management in combination with family engagement strategies was more effective than the usual treatment at reducing marijuana use, crimes against persons, and crimes against property among juvenile offenders. |

| ( ) | Middle and high school students in New Hampshire participating in the New Hampshire Youth Study from 2007–2009 (n = 596) | Delinquency and parental legitimacy | Authoritative parenting is positively associated with and authoritarian parenting is negatively associated with parental legitimacy. Parental legitimacy reduces the likelihood of future delinquency. |

| ( ) | Previously arrested youth ages 11–17 who participated in a functional family therapy program (n = 134) | Post-treatment levels of adjustment and likelihood of offending | Individuals with callous-unemotional traits face more challenges and symptoms when beginning treatment and are more likely to violently offend during treatment, but functional family therapy can help to reduce their likelihood of violent offending post-treatment. |

| ( ) | Youth ages 11–19 with a history of juvenile justice involvement receiving intensive in-home services from 2000–2009 in the Southeastern United States (n = 5000) | Classification of youth as recidivists, at-risk, or non-recidivists | The model of in-home services was associated with reduced re-offending, particularly among girls, and with increased likelihood of living at home and attending or completing school for both boys and girls. |

| ( ) | Youth ages 13–18 participating in a juvenile drug court in Florida (n = 112) | Offending and substance use | The results support the use of family therapy in juvenile drug court treatment programs to reduce criminal offending and recidivism. |

| ( ) | Active cases of youth ages 10–17 involved with the Safety Net Collaborative in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 2013 (n = 30) | Arrest rates and mental health referrals | Following the implementation of the safety net collaborative, an integrated model that provides mental health services for at-risk youth, community arrest rates declined by over 50%. |

| ( ) | Moderate- to high-risk juvenile offenders involved in the Parenting with Love and Limits group and family therapy program between April 2009 to December 2011 in Champaign County, Illinois (n = 155 in treatment; n = 155 in control group) | Recidivism rates and parent-reported behavior | The Parenting with Love and Limits group and family therapy program was associated with significantly reduced recidivism rates and behavioral improvements, indicating potential effectiveness of family and group therapy to reduce recidivism among those at the highest risk. |

| ( ) | Rhode Island youth participating in a multisystemic therapy program (n = 577) and in a control group (n = 163) | Out-of-home placement, adjudication, placement in a juvenile training school, and offending | Receipt of multisystemic therapy was associated with lower rates of offending, out-of-home placement, adjudication, and placement in a juvenile training school, demonstrating the potential efficacy of multisystemic therapy in reducing delinquency among high-risk youth. |

| ( ) | ZIP codes with the Fit2Lead park-based violence prevention program and matched control communities without the program in Miami-Dade County, Florida from 2013–2018 (n = 36 ZIP codes) | Change in arrest rates per year among youth ages 12–17 | Park-based violence prevention programs such as Fit2Lead may be more effective at reducing youth arrest rates than other after-school programs. Results support the use of community-based settings for violence interventions. |

| ( ) | Court-involved girls on probation from 2004–2014 in one Midwest juvenile family court who received the family-based intervention (n = 181) or did not (n = 803) | Recidivism rates | One-year recidivism rates were lower among girls who participated in the family-based intervention program compared to those just on parole. Qualitative interviews highlighted the importance of family-focused interventions for justice-involved girls. |

| ( ) | Individuals involved in the Missouri Delinquency Project from 1990–1993 and randomized to multisystemic therapy for potential sexual behaviors or the usual treatment of cognitive behavioral therapy (n = 48) | Arrest, incarceration, and civil suit rates in middle adulthood | Participants assigned to the multisystemic therapy treatment were less likely to have been re-arrested by middle adulthood and had lower rates of sexual and nonsexual offenses, demonstrating the potential benefits of targeted therapies. |

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Aazami, A.; Valek, R.; Ponce, A.N.; Zare, H. Risk and Protective Factors and Interventions for Reducing Juvenile Delinquency: A Systematic Review. Soc. Sci. 2023 , 12 , 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090474

Aazami A, Valek R, Ponce AN, Zare H. Risk and Protective Factors and Interventions for Reducing Juvenile Delinquency: A Systematic Review. Social Sciences . 2023; 12(9):474. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090474

Aazami, Aida, Rebecca Valek, Andrea N. Ponce, and Hossein Zare. 2023. "Risk and Protective Factors and Interventions for Reducing Juvenile Delinquency: A Systematic Review" Social Sciences 12, no. 9: 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090474

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

Juvenile Delinquency

Theory, Research, and the Juvenile Justice Process

- © 2020

- Latest edition

- Peter C. Kratcoski 0 ,

- Lucille Dunn Kratcoski 1 ,

- Peter Christopher Kratcoski 2

Sociology/Justice Studies, Kent State University, Tallmadge, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Tallmadge, USA

Williams, Welser & Kratcoski LLC, Kent, USA

- Provides an overview of major topics related to Juvenile Delinquency for advanced undergraduate and graduate-level students

- Includes quantitative and qualitative research findings, with new interviews and discussions of the experiences of child care professionals and juvenile justice practitioners

- Provides an interpretation of theory to practice in the criminal justice system

- Explores recent discussion of children as victims, such as non-fault children who are victims of abuse, neglect, and at-risk situations such as violence and bullying

- Incorporates international perspectives on juvenile justice and delinquency, in addition to addressing changes in the characteristics of delinquents, changes in laws, and the influence of social media and electronic communications devices on juvenile delinquency

51k Accesses

18 Citations

3 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

About this book

Similar content being viewed by others.

How Young Offenders’ Perceive Their Life Courses and the Juvenile Justice System: A Systematic Review of Recent Qualitative Research

Examining the Presenting Characteristics, Short-Term Effects, and Long-Term Outcomes Associated with System-Involved Youths

It’s F**ing Chaos: COVID-19’s Impact on Juvenile Delinquency and Juvenile Justice

- juvenile delinquency

- juvenile justice

- at-risk children

- at-risk youth

- status offenders

- juvenile court

- family court

- juvenile corrections

- developmental and life-course criminology

- age-crime curve

Table of contents (16 chapters)

Front matter, the transition of child to adult.

- Peter C. Kratcoski, Lucille Dunn Kratcoski, Peter Christopher Kratcoski

Past and Current Bio-Social Perspectives on Delinquency Causation

Social-psychological theories of delinquency, social organization perspectives on delinquency causation, perspectives on interpersonal relationships in the family, perspectives on gangs and peer group influences pertaining to delinquency causation, perspectives on delinquency and violence in the schools, laws and court cases pertaining to children: offenders and victims, perspectives on children as victims of abuse and neglect, the police role in delinquency prevention and control, processing the juvenile offender: diversion, informal handling, and special dockets, the juvenile court process, probation and community-based programs, perspectives on juveniles incarcerated in secure facilities, parole and community supervision, counseling and treatment of juvenile offenders, back matter, authors and affiliations.

Peter C. Kratcoski

Lucille Dunn Kratcoski

Williams, Welser & Kratcoski LLC, Kent, USA

Peter Christopher Kratcoski

About the authors

Peter Charles Kratcoski earned a PhD in sociology from the Pennsylvania State university, a MA in sociology from the University of Notre Dame and a BA in sociology from King’s College. He taught at St. Thomas College and Pennsylvania State University before assuming the position of assistant professor of sociology at Kent State University. He retired as professor of sociology/criminal justice studies and Chairman of the Department of Criminal Justice Studies at Kent State University. He is currently a professor emeritus and adjunct professor at Kent State. He has published many books, book chapters and journal articles in juvenile delinquency, juvenile justice, juvenile victimization and crime prevention as well as completing numerous research projects relating to policing, crime prevention, juvenile delinquency prevention and victimization. His most recent publications include author of Correctional Counseling and Treatment (6 th edition) 2017, co-editor of Corruption, Fraud, Organized Crime, and the Shadow Economy, 2016 and co-editor of Perspectives on Elderly Crime and Victimization, 2018.

Lucille Dunn Kratcoski was awarded a Bachelor of Arts degree from Marywood College and a Master degree in music from Pennsylvania State University. She has numerous years teaching experience at the elementary, high school and university levels as well as providing private instruction. She co-authored Juvenile Delinquency and a number of book chapters and journal articles on the subject of juvenile delinquency and juvenile justice. In addition to her private practice, she serves as a Kratcoski Research Associate.

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : Juvenile Delinquency

Book Subtitle : Theory, Research, and the Juvenile Justice Process

Authors : Peter C. Kratcoski, Lucille Dunn Kratcoski, Peter Christopher Kratcoski

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31452-1

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Law and Criminology , Law and Criminology (R0)

Copyright Information : Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-030-31451-4 Published: 16 December 2019

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-030-31454-5 Published: 06 January 2021

eBook ISBN : 978-3-030-31452-1 Published: 03 December 2019

Edition Number : 6

Number of Pages : XXVI, 442

Number of Illustrations : 6 b/w illustrations

Additional Information : Originally published by Pearson Education, Inc., Old Tappan, New Jersey, 2003

Topics : Youth Offending and Juvenile Justice , Criminological Theory

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Community Med

- v.47(4); Oct-Dec 2022

Juvenile’s Delinquent Behavior, Risk Factors, and Quantitative Assessment Approach: A Systematic Review

Madhu kumari gupta.

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Birla Institute of Technology, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India

Subrajeet Mohapatra

Prakash kumar mahanta.

1 Department of Clinical Psychology, Ranchi Institute of Neuro-Psychiatry and Allied Science, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India

Background:

Not only in India but also worldwide, criminal activity has dramatically increasing day by day among youth, and it must be addressed properly to maintain a healthy society. This review is focused on risk factors and quantitative approach to determine delinquent behaviors of juveniles.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 15 research articles were identified through Google search as per inclusion and exclusion criteria, which were based on machine learning (ML) and statistical models to assess the delinquent behavior and risk factors of juveniles.

The result found ML is a new route for detecting delinquent behavioral patterns. However, statistical methods have used commonly as the quantitative approach for assessing delinquent behaviors and risk factors among juveniles.

Conclusions:

In the current scenario, ML is a new approach of computer-assisted techniques have potentiality to predict values of behavioral, psychological/mental, and associated risk factors for early diagnosis in teenagers in short of times, to prevent unwanted, maladaptive behaviors, and to provide appropriate intervention and build a safe peaceful society.

I NTRODUCTION

Juvenile delinquency is a habit of committing criminal offenses by an adolescent or young person who has not attained 18 years of age and can be held liable for his/her criminal acts. Clinically, it is described as persistent manners of antisocial behavior or conduct by a child/adolescent repeatedly denies following social rules and commits violent aggressive acts against the law and socially unacceptable. The word delinquency is derived from the Latin word “delinquere” which described as “de” means “away” and “linquere” as “to leaveor to abandon.” Minors who are involved in any kind of offense such as violence, gambling, sexual offenses, rape, bullying, stealing, burglary, murder, and other kinds of anti-social behaviors are known as juvenile delinquents. Santrock (2002) defined “an adolescent who breaks the law or engages in any criminal behavior which is considered as illegal is called juvenile delinquent.”[ 1 ] In India, Juvenile Justice (J. J.-Care and protection of Children) Act of 2000 stated that “an individual whether a boy/girl, who is under 18 years of age and has committed an offense, referred or convicted by the juvenile court have considered a juvenile delinquent.”

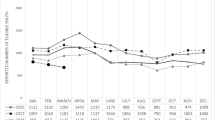

P REVALENCE R ATE : J UVENILE D ELINQUENCY IN I NDIA

According to the National Crime Records Bureau (India, 2019), statistical data of crimes in India show that overall, 38,685 juveniles were placed under arrest in 32,235 cases, among 35,214 juveniles were taken into custody under cases of IPC and 3471 juveniles were arrested under cases of special and local laws (SLL) during 2019. About 75.2% of the total convicted juveniles (29,084 out of 38,685) were apprehended under both IPC and SLL belonging to the age group 16–18 years. In 2019, 32,235 juvenile cases involving and recorded, indicating a slight increment of 2.0% over 2018 (31,591 cases). The rate of crime also indicates a slight increase from 7.1 (2018) to 7.2 (2019).[ 2 ] The total registered cases against juvenile delinquents are calculated as crime incidence rate per one Lakh population as shown in Figure 1 .

The graphical view of registered cases against Juveniles in conflict with law under Indian penal code and special and local laws crimes during 2014–2019 of all the State (s) and union territories of India Sources: Crime in India National (2014-2019), National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), Ministry of Home Affairs, 2019

R ISK -F ACTORS A FFECTING D ELINQUENT B EHAVIOR

Studies identify that multiple risk factors are responsible for delinquent behavior categorized as individual, parental, family, community, society, schools/educational, financial, mental as well as psychological factors of the individual and the family shown in Table 1 . Adolescents involve themselves in various anti-social activities to fulfill their basic needs. Basically, “delinquency” is just a recreational activity for earning money. These risk factors differ from person to person during the early childhood period and very crucial because children, who are involved in any kind of deviant activity at an early stage, have a higher chance to adopt delinquent tendencies chronically.[ 33 ]

Developmental phases, risk-factors and developing delinquent behaviours of the child

| Developmental phase | Risk-factors | Delinquent behavior |

|---|---|---|

| During pregnancy to infancy period (initial phase) | The child | Complications during pregnancy and delivery of the child; exposure to neurotoxins or any early childhood serious diseases after birth; difficult temperament; impulsivity/hyperactivity; poor attention/concentration; below intellectual ability; male gender |

| Family | Alcohol/any substance/drug/smoking by mother during pregnancy; teenage mother; parents poor education; maternal clinical depression; parent’s involvement in drugs/substance abuse and antisocial/criminal activities; poor parent-child communication; poor socioeconomical conditions; serious marital conflicts; large family size | |

| Toddler phase | Child | Aggressive/impulsive/disruptive behavior; persistent lying; attention seeking/risk-taking behavior; lack of guilt/empathy |

| Family | Harsh/abusive/erratic discipline in the family or member’s behaviors; lack of supervision/neglect/maltreatment; parental separation with child | |

| Community | Violence television shows; violent/abusive neighbors | |

| Middle childhood period | Child | Disruptive behaviors; involving in criminal activities like stealing, pocketing, etc.,; early-onset of substance abusing and or sexual activities or as victims of early sexual and physical abuses; mood swings as high or low (manic/depressive); withdrawal behavior; positive attitude towards disruptive behaviors; exposure and victimization to any violence or abusive acts; hyperactivity, poor attention and concentration, restlessness, and/or risk-taking behaviors; violent behavior; involvement of antisocial activities; favorable beliefs and attitude of the individual to deviant/antisocial behavior |

| Family | Lack of parental supervision; parental conflict; deprivation of basic need in the family | |

| School | Poor academic performance; negative attitude towards schools; lack of supervision by teachers and school staffs; truancy; poor organizational and management functioning of the school | |

| Peer groups | Rejection by peers; association with gang members or deviant peers and siblings; sibling’s involvement in criminal activities; Peer’s involvement in criminal activities; beliefs and attitude of peers to deviant/antisocial behavior | |

| Community | Residence in a disorganized/disadvantaged neighborhood; availability of arms/weapons; availability of drugs/substances; poverty/poor neighborhood; neighbor’s involvements in criminal acts | |

| Adolescent period | Adolescents | Psychological conditions - emotional, cognitive and intellectual ability, personality; physical disabilities; involvement in any drug or substance dealing activities; carrying arms or weapons; belief and attitude of the individual to deviant/antisocial behavior |

| Family | Poor family management; low levels of parental supervision; family conflict or poor bonding of family members; parental involvement in any antisocial or criminal activities; child misbehave or maltreatment; parental separation with a child; socioeconomical condition of family and members | |

| School | School dropout; frequent school transitions; low attachment with teachers, school staffs, and mates | |

| Peer groups | Involving in a gang; peer groups engaged in criminal acts; peer’s beliefs and attitude to antisocial behavior | |

| Community | Community and neighborhood disorganization; poverty; drugs, alcohol, etc., substances availability; neighborhood involvement in criminal acts; exposure to racial and violent prejudice and stigmas |

Juvenile delinquency is caused by a wide range of factors, such as conflicts in the family, lack of proper family control, residential environmental effects, and movie influence, along with other factors are responsible for delinquent behavior.[ 3 ] Family and environmental factors, namely restrictive behaviors, improper supervision, negligence, criminal activities of parents, improper motivation by peers, fear of peer rejection, poverty, illiteracy, poor educational performance at school, lack of moral education may turn the individual personality into delinquents. Moreover, in the environment, deteriorated neighborhood, direct exposure to violence/fighting (or exposure to violence through media), violence-based movies are considered major risk factors.[ 4 ] In India, a higher level of permissive parenting in low-income families had so many family members and due to economic conditions, the adolescents had pressure to search various income sources to sustain the family, and it has affected parental behavior toward adolescents.[ 5 ] The children who belong to the lower middle-socio-economical class and are rejected by society showed more aggressive behavior.[ 6 ]

Juvenile gang members exhibit significantly higher rates of mental health issues such as conduct disorders, attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorders, antisocial personality disorder, posttraumatic-stress-disorders, and anxiety disorders.[ 7 ] As well as the intellectual level of young offenders is significantly different from nonoffenders. Emotional problems on adolescents are related to delinquent behavior and impulsivity directly associated with antisocial behavior among adolescents.[ 8 ] Poor self-control of adolescents involved them in substance use, affected harmfully, and increased involvements in anti-social activities.[ 9 ] Nonviolent people, who not involved in any gang, are less likely to utilize mental-health services, having lower levels of psychiatric morbidity, namely antisocial personality disorders, psychosis, and anxiety disorders, when compared with the group of violent offenders.[ 10 ]

M ACHINE L EARNING : A N EW Q UANTITATIVE E VALUATION A PPROACH

Machine learning (ML) is belonging to the multidisciplinary field that includes programming, math, and statistics, and as a new and dynamic field that necessitates more study. It is a branch of computer science that emerged through pattern recognition and computational learning theory of artificial intelligence. ML is exploring researches and development of algorithms that can learn and genera tea prediction besides a given set of data through the computer. It is a scope for the study that gives computers the capability to learn without being principally programmed.[ 11 ] Tom M. Mitchell explained ML as “a computer-based program to learn from action of “E” concerning any task of ‘T’s, and some performance evaluates “P,” if its performance on “T,” as assessed by “P,” improves with action of E.”[ 12 ] The goal of ML is to mimic human learning in computers.[ 13 ] Humans learn from their experiences and ML methods learn from data. The user provides a portion of a dataset designated to train by the algorithm. The algorithm creates a model based on the relationships among variables in the dataset, and the remaining dataset is used to validate the ML model. In simple words, ML approach is for risk indicator is meant to magnify the potential of current knowledge.[ 15 ] ML sits at the common frontier of many academic fields, including statistics, mathematics, computer science, and engineering.[ 14 , 17 ] ML models principally categorized into three categories, namely supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement based on their task which they are attempting to accomplish. Supervised learning is relying on a training set where some characteristics of data are known, typically labels or classes, and target to find out the universal rule that maps inputs to outputs. Unsupervised learning has no design to give to the learning algorithm, balance itself to find out the patterns through inputs. In reinforcement, interaction with a dynamic environment happens during which a particular target such as driving a vehicle is performed without a driver principally involved in any activities, namely comparison. In numerous studies, pattern classification approaches based on ML algorithms are used to forecast human beings into various categories by maximizing the distance among data groups. ML generally refers to all actions that train a computer algorithm to determine a complicated pattern of data that is conceivable used for forecast category of membership into a new theme (e.g., individual vs. controls).[ 32 ]

R ATIONAL OF THE S TUDY

In the last decade, various researchers have been attracted to the use of quantitative computer-based techniques for analyzing various psychological and clinical aspects, which have greatly contributed to the area of modern psychology. In this analysis, most of the works are devoted to the use of various quantitative analysis techniques, namely ML and statistical methods which has utilized by the researchers for evaluating various risk and protective factors of juveniles. Henceforth, studies on the application of the ML model for risk-assessment of delinquent behavior on juveniles are limited as compared to other techniques, namely logistic regression. Hence, this review paper may explore the utilization of ML to get an easy and quick assessment on juveniles and helpful for future studies. It may help to determine the most significant risk factors and establishment of a successful treatment program that prevents juveniles from delinquent activities and stops them from recidivism.

In this review, all these studies carried out which has used various quantitative techniques to detected juvenile delinquency with specially emphasis on ML and statistical approaches. The review is organized into four sections follows as: Section-I gives an overview of juvenile delinquency, prevalence rates in India, and various behavioral risk factors during the developmental period. It also provides general information about ML as a new approach and their application. Section-II included information about the methodology of the present review. Section-III explores the results and discusses which explore the ML and statistical methods for detecting juvenile behaviors and Section-IV concludes the extant research of the present review and the implications for future work.

M ETHODOLOGY

This review paper aim is to find the various quantitative techniques (computer-assisted techniques) ML and statistical approaches which have been used for assessing/predicting delinquent behaviors, traits, and risk factors among juveniles.

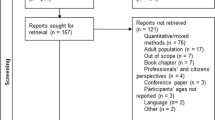

Sources of information

For this review article, a total of 15 research articles were identified and selected through Google-scholar, Web of Science, Academia, PubMed, and Research-Gate, using the keywords, namely juvenile-delinquency, ML, Risk-factors, and delinquent-behavior. All relevant studies were selected for review of the quantitative approaches for identifying delinquent behavior and risk factors of adolescents and the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for articles search process as shown in Figure 2 .[ 34 ]

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow diagram for search outcomes of quantitative assessment of juvenile delinquent behaviors

Inclusion criteria

Research studies published since 2011–2019, case studies, empirical, quantitative, qualitative, and cross-sectional studies published in English were included, which used ML and statistical models to analyze behaviors, risk and associated factors among juveniles.

Exclusion criteria

Protocol, dissertations, prototype studies, and studies which published in other languages were excluded.

Studies on machine learning and statistical methods among juvenile delinquency

In this review, we performed a rigorous search of the literature to provide a narrative description of the various quantitative computer-based approaches which are applicable to assess and identify the delinquent behaviors and risk factors on juveniles. Initially, the search identified 150 articles through various databases, search outcomes show in the PRISMA flow diagram [ Figure 2 ]. One hundred and thirty-five articles were removed by screening through the title, text, removal of duplicate articles and based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, we identified 15 research articles in full text and these selected articles comprising through expert opinions. The findings of these articles tabulated the diverse approaches on the current state of knowledge about assessment of early diagnosis of delinquent behaviors and risk factors and tried to provide a summary which based on computer-based quantitative analysis [ Table 2 ].

Summary table of relevant studies which used quantitative approach to detect delinquent behaviors and risk factors among juvenile behaviors

| Author’s name and year | Samples and sources | Aims/objectives | Model/methods for analyzing result | Findings of the study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castro and Hernandez, 2019[ ] | City Social Welfare Development Office, Butuan, Philippines, A total sample 360 children (177 chidren at risk, or have experience maltreatment and 183 children in conflict with law) | To develop a predictive model to analyze the children in conflict with law, and at-risk as well as compel the preventive options | Decision tree, Naive Bayes model, GLMs and logistic regression | Large numbers of children from 12–17 years are victims of maltreatment, and adolescents from 15–17 years are committed to severe criminal activities |

| Kim . (2019)[ ] | Across various jurisdictions from Florida, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. A total of 8000 sexually offending juveniles, from 2009 to 2013 | The study examined the present practice and policy for the assessment, treatment, and intervention of sexually offender delinquents | Traditional regression and ML algorithms | Criminal history, sexual offending experiences, delinquent peers are the most important risk factors. Some influential factors viz., school performance, peer connection; regretful feelings, impulsiveness, mental health, and substance abuse are theimportant predictive factors of sexual offenders for recidivism |

| Sumalatha and Santhi, 2018[ ] | Juvenile delinquents | To establish a model for enhancing the efficiency of the Bayes algorithm classification for detecting juvenile affliction depends on paternity behavior and usage of digital gadgets. A model consisting of three phases’ viz., ranking prototype, PEH model, and CAPM | Naive Bayes probabilistic model | Juvenile affliction is highly dependent upon parental behavior and influence by digital gadgets |

| Rokven . 2018[ ] | 12–17 years, Dutch juveniles | For comparison among four groups - Online delinquents, offline delinquents, nondelinquents, and both online and offline delinquents | Multinominal logistic regression | Juveniles who had a history of offline and online offenses belong to the high-risk profiles |

| Meldrum . 2015[ ] | Multi-city cohort research study among adolescents, from birth to 15 years of age. A total number of 825 adolescents; 50% females; 82% white non-Hispanic, 59% two-parent or nuclear family | To measure the connection between sleep and delinquency | Regression model | Delinquency is indirectly related to sleep loss where poor self-control plays the role of catalyst |

| Castellana . 2014[ ] | 39 young offenders who did not have any previous mental problems, and 32 nonoffenders’ young people with similar SES | To assess differences in psychopathic behavior between youths of offending and nonoffending people with the same SES | ANCOVA | The requirement of a wide variety of interventions including SES factors to control juvenile delinquency |

| DeLisi . 2013[ ] | 227 Juvenile delinquents (male and female), from nonprofitable juvenile residential facilities, western Pennsylvania | To find the correlation between violent video games and violence among youth | Negative binominal regression | Violent video games directly associated with anti-sociality, and multiple correlates viz., psychopathology |

| Fernández-Suárez . 2016[ ] | A total of 218 juvenile male offenders and 46 females who arrested under a judicial penal code in Asturias (Spain) in the year 2012 | Find the connection between school dropout with multiple causes’ viz., individual and family factors | Multivariate logistic regression | School dropout has higher irresponsibility, illegal alcohol, and drugabuse, inadequate parental supervision, as compared to nondropout individuals |

| Margari . 2015[ ] | 135 juvenile offenders (male-female both), age range 14–18 years, adjudicated by the juvenile court of Puglia | To find out the impact of multiple predictor variables as academic performance and peer factors on conduct problem | Multiple regression | Educational achievements problems in 52% juvenile; 34% had a history of psychiatric problems in the family. 60% of juvenile delinquents involved in property-related crime, 54% were involved in drug and substance abuse-related activities; these factors affecting severely students academic achievements |

| Wu, 2015[ ] | A total of 2690 secondary school students | To find out the school life based on academic performance, delinquency, | Multidimensional Scaling model | Dynamic cognitive mechanisms were utilized in which individual’s measure and weigh their self as |

| social, and financial factors to assess the behavioral similarity among adolescents | well as other person’s position | |||

| Brunelle . 2014[ ] | 726 youth, enrolled in the addiction service left atQuebec City, from March 1999 to 2003. | To examine the time of youth’s request for addiction services in the addiction rehabilitation center | MANCOVA | History of sexual abuse is one of the strongest factors connected with psychotropic substance-using severity |

| Gordon . 2014[ ] | 600 gang and nongang members, Pittsburgh Youth Study data | Involvement in serious delinquent behavior viz., drug business, serious violent and burglary acts, around 1990 | Multiple logit model | Gang members having a high level of delinquent behavior were mainly involved in the drug business, serious theft, and violence as compared to nongang-members |

| Parks, 2013[ ] | =4389, data used from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health | To find out the variations among adolescent delinquency between cohabitating family, other family types, and the effect of parental social control on the variation of delinquency in different family compositions | Binary logistic regression along with multivariate models | No major differences in violent behaviors in both groups (cohabitating families and other family types). However, adolescents of cohabitating families have a higher risk of involving in a nonviolent form of delinquency compare with natural-parental families with marginal significance |

| Low . 2012[ ] | 244 families (122 younger brothers and 122 younger sisters) | To assess the economic strain of delinquency among adolescents | SEM | Sibling aggression has a very strong and harmful effect on adolescents who belongs to economically strained families. Economic conditions of the family are highly associated with the effect of parents, siblings, and peer as risk and juvenile delinquency |

| Gold . 2011[ ] | 112 adolescents (22 females and 90 males) from the age range of 12–19 years, staying in a Juvenile detention facility pending criminal charges | Assess the relationship between abusive and nonabusive parenting, adolescent shame (expressed and converted), and violent delinquency | Hierarchical regression model, ANOVA | Abusive parenting is connected to violent delinquency directly as well as indirectly through converted shame. Conversion of shame is the major cause of more violent delinquency when compared to expressed shame |

GLM: Generalized linear model, ML: Machine learning, PEH: Probabilistic estimation hypothesis, CAPM: Categorization of anxiety predictor model, SES: Socioeconomic status, SEM: Structural equation model

D ISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we performed a rigorous search of the literature to provide a narrative picture of various methods used to identify juveniles’ behaviors. We identified 15 articles, with the objective to analyze the application of ML and other quantitative approaches to assess various delinquent behaviors and risk factors of juveniles. The studies revealed ML is a new quantitative method to identify the risk factors and delinquent behavior henceforth; there very few studies are conducted. In this study, we tried to provide a summary of selected articles on the current state of knowledge about quantitative analysis for assessment of delinquent behaviors of juveniles and there only few articles have used ML as quantitative analysis. The City Social Welfare Development Office of Butuan, Philippines, used a dataset to create predictive models for analyzing the minors at risk and children in conflict with poor financial status. And found children with age range 12–17 years are victims of maltreatment, and adolescents between the ages of 15–17 years commit severe crimes.[ 16 ] Kim et al .[ 18 ] used traditional regression, ML method and certified the predictive validity of the models in numerous ways, along with traditional hold-out validation k-fold cross-validation, and bootstrapping to examine the present practice and policy for assessment, treatment, and management of delinquents who have a history of sexual conviction in multiple jurisdictions from New York, Florida, Oregon, Virginia, and Pennsylvania. Results revealed that important risk factors among juveniles had some criminal history, sexual offending experiences, and delinquent peers. Some dynamic factors viz. performance in school, peer connection, sorrowful feelings, impulsiveness, mental health, and substance abuse are important anticipating factors among sexual offenders for recidivism.

Rokven et al .[ 19 ] used multinomial logistic regression technique to compare four types of delinquent groups: online delinquents, offline delinquents, nondelinquents, and delinquents who belong to both online and offline categories and found juveniles who having both online and offline criminal records are more likely to commit crimes. Delinquency is indirectly linked with sleep deprivation, with poor self-control acting as a catalyst proved by regression models with latent factors.[ 20 ] Violent video games directly associated with anti-social behavior, even though several correlates, such as psychopathologies has present in youth analyzed by negative binomial regression (extended version of Poisson regression).[ 22 ]

Fernández et al . analyzed through multivariate logistic regression and found, school dropouts’ teenagers had a higher level of irresponsibility, substance, and illicit drug abuse compare then nondropouts.[ 23 ] In addition, lack of parental supervision plays a significant role in the prediction of deviant behaviors on school dropouts. School dropout teenagers have multi-dimensional problem that requires proper parental supervision and proactive school policies to reducing drug and alcohol abuse.[ 23 ] Fifty-two percent of juvenile offenders had issues with academic performance, 34% had family history of psychiatric disorders, 60% of juveniles involved in property crime and 54% of offenders involved in drugs and alcohol use-related offenses had some deficiency in academic achievement evaluated by multiple regression techniques.[ 24 ] Wu (2015) created a multidimensional scaling model and found students used a complex cognitive-mechanism measured and compared their position to friends and others.[ 25 ]

Sexually assaulted history has strongly associated and one of the most powerful variables associated with the intensity of psychoactive substances using by juveniles.[ 26 ] Parks[ 28 ] has used binary logistic regression and multivariate models revealed that no major variations in violent juveniles belong to cohabiting families and other families. However, teenagers of cohabiting families have marginally higher risk to involving in nonviolent forms of crime.[ 28 ] Economic conditions of the family has strongly linked to the influences of parents, siblings, and peers at risk and delinquency. Economic stress, having an active sibling aggression, harmful, and more destructive events affected seriously on adolescent delinquent behaviors who belongs to economically poor families.[ 29 ] Coercive parents are directly associated with violent delinquency of adolescents on both ways as explicitly and indirectly and transformed shame on adolescents. As opposed to articulated guilt, shame conversion is the major cause for more violence.[ 30 ]

It is very difficult to evaluate all possible outcomes and explain a single quantitative approach as ML to early identification of delinquent behaviors and risk-factors of juveniles for intervene in the affected factors. Our study has several limitations. First, other studies rather than the English language were we not included in the study. Second, counties like India have very less evidence-based studies in the field of early detection of juveniles and computer-based assessment approaches as ML for quantitative analysis. Third, only 15 articles were considered which fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

I MPLICATION