- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Critical thinking in...

Critical thinking in healthcare and education

- Related content

- Peer review

- Jonathan M Sharples , professor 1 ,

- Andrew D Oxman , research director 2 ,

- Kamal R Mahtani , clinical lecturer 3 ,

- Iain Chalmers , coordinator 4 ,

- Sandy Oliver , professor 1 ,

- Kevan Collins , chief executive 5 ,

- Astrid Austvoll-Dahlgren , senior researcher 2 ,

- Tammy Hoffmann , professor 6

- 1 EPPI-Centre, UCL Department of Social Science, London, UK

- 2 Global Health Unit, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway

- 3 Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, Oxford University, Oxford, UK

- 4 James Lind Initiative, Oxford, UK

- 5 Education Endowment Foundation, London, UK

- 6 Centre for Research in Evidence-Based Practice, Bond University, Gold Coast, Australia

- Correspondence to: J M Sharples Jonathan.Sharples{at}eefoundation.org.uk

Critical thinking is just one skill crucial to evidence based practice in healthcare and education, write Jonathan Sharples and colleagues , who see exciting opportunities for cross sector collaboration

Imagine you are a primary care doctor. A patient comes into your office with acute, atypical chest pain. Immediately you consider the patient’s sex and age, and you begin to think about what questions to ask and what diagnoses and diagnostic tests to consider. You will also need to think about what treatments to consider and how to communicate with the patient and potentially with the patient’s family and other healthcare providers. Some of what you do will be done reflexively, with little explicit thought, but caring for most patients also requires you to think critically about what you are going to do.

Critical thinking, the ability to think clearly and rationally about what to do or what to believe, is essential for the practice of medicine. Few doctors are likely to argue with this. Yet, until recently, the UK regulator the General Medical Council and similar bodies in North America did not mention “critical thinking” anywhere in their standards for licensing and accreditation, 1 and critical thinking is not explicitly taught or assessed in most education programmes for health professionals. 2

Moreover, although more than 2800 articles indexed by PubMed have “critical thinking” in the title or abstract, most are about nursing. We argue that it is important for clinicians and patients to learn to think critically and that the teaching and learning of these skills should be considered explicitly. Given the shared interest in critical thinking with broader education, we also highlight why healthcare and education professionals and researchers need to work together to enable people to think critically about the health choices they make throughout life.

Essential skills for doctors and patients

Critical thinking …

Log in using your username and password

BMA Member Log In

If you have a subscription to The BMJ, log in:

- Need to activate

- Log in via institution

- Log in via OpenAthens

Log in through your institution

Subscribe from £184 *.

Subscribe and get access to all BMJ articles, and much more.

* For online subscription

Access this article for 1 day for: £33 / $40 / €36 ( excludes VAT )

You can download a PDF version for your personal record.

Buy this article

Why Critical Thinking Is Important (& How to Improve It)

Last updated May 1, 2023. Edited and medically reviewed by Patrick Alban, DC . Written by Deane Alban .

By improving the quality of your thoughts and your decisions, better critical thinking skills can bring about a big positive change in your life. Learn how.

The quality of your life largely depends on the quality of the decisions you make.

Amazingly, the average person makes roughly 35,000 conscious decisions every day!

Imagine how much better your life would be if there were a way to make better decisions, day in and day out?

Well, there is and you do it by boosting a skill called critical thinking .

Learning to master critical thinking can have a profoundly positive impact on nearly every aspect of your life.

What Exactly Is Critical Thinking?

The first documented account of critical thinking is the teachings of Socrates as recorded by Plato.

Over time, the definition of critical thinking has evolved.

Most definitions of critical thinking are fairly complex and best understood by philosophy majors or psychologists.

For example, the Foundation for Critical Thinking , a nonprofit think tank, offers this definition:

“Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action.”

If that makes your head spin, here are some definitions that you may relate to more easily.

Critical thinking is “reasonable, reflective thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or do.”

WHAT'S THE BEST BRAIN SUPPLEMENT?

I hear this question often. Here's my answer:

#1 Live a brain-healthy lifestyle first (Be Brain Fit tells you how).

#2 Give Mind Lab Pro a try.

This brain supplement meets all 12 of my requirements for a high-quality brain supplement, including effectiveness, safety, purity, and value. So it's easier for you to be mentally sharper, positive, and more productive.

Choosing the right brain supplement is all about quality. See why I recommend Mind Lab Pro.

Or, a catchy way of defining critical thinking is “deciding what’s true and what you should do.”

But my favorite uber-simple definition is that critical thinking is simply “thinking about thinking.”

6 Major Benefits of Good Critical Thinking Skills

Whether or not you think critically can make the difference between success and failure in just about every area of your life.

Our human brains are imperfect and prone to irrationality, distortions, prejudices, and cognitive biases .

Cognitive biases are systematic patterns of irrational thinking.

While the number of cognitive biases varies depending on the source, Wikipedia, for example, lists nearly 200 of them !

Some of the most well-known cognitive biases include:

- catastrophic thinking

- confirmation bias

- fear of missing out (FOMO)

Critical thinking will help you move past the limitations of irrational thinking.

Here are some of the most important ways critical thinking can impact your life.

1. Critical Thinking Is a Key to Career Success

There are many professions where critical thinking is an absolute must.

Lawyers, analysts, accountants, doctors, engineers, reporters, and scientists of all kinds must apply critical thinking frequently.

But critical thinking is a skill set that is becoming increasingly valuable in a growing number of professions.

Critical thinking can help you in any profession where you must:

- analyze information

- systematically solve problems

- generate innovative solutions

- plan strategically

- think creatively

- present your work or ideas to others in a way that can be readily understood

And, as we enter the fourth industrial revolution , critical thinking has become one of the most sought-after skills.

According to the World Economic Forum , critical thinking and complex problem-solving are the two top in-demand skills that employers look for.

Critical thinking is considered a soft or enterprise skill — a core attribute required to succeed in the workplace .

NUTRITION FOR THE MIND/BODY CONNECTION

It’s almost impossible to live a lifestyle that provides all the nutrients needed for good brain health and performance. The reason? All of us confront multiple nutrient thieves — stress, poor diet, insomnia, pharmaceuticals, pollution, and more — that steal nutrients that the brain needs to thrive.

- Provides the building blocks to create new brain cells and brain chemicals

- Helps increase resilience to stress to avoid mental burnout

- Supplies the brain with the fuel it needs for mental energy

A foundational principle of mental health and cognitive performance is to supply the body with the best nutrition possible. See why I recommend Performance Lab.

According to The University of Arizona, other soft skills include :

- interpersonal skills

- communication skills

- digital literacy

Critical thinking can help you develop the rest of these soft skills.

Developing your critical thinking can help you land a job since many employers will ask you interview questions or even give you a test to determine how well you can think critically.

It can also help you continually succeed in your career, since being a critical thinker is a powerful predictor of long-term success.

2. Critical Thinkers Make Better Decisions

Every day you make thousands of decisions.

Most of them are made by your subconscious , are not very important, and don’t require much thought, such as what to wear or what to have for lunch.

But the most important decisions you make can be hard and require a lot of thought, such as when or if you should change jobs, relocate to a new city, buy a house, get married, or have kids.

At work, you may have to make decisions that can alter the course of your career or the lives of others.

Critical thinking helps you cope with everyday problems as they arise.

It promotes independent thinking and strengthens your inner “BS detector.”

It helps you make sense of the glut of data and information available, making you a smarter consumer who is less likely to fall for advertising hype, peer pressure, or scams.

3. Critical Thinking Can Make You Happier

Knowing and understanding yourself is an underappreciated path to happiness.

We’ve already shown how your quality of life largely depends on the quality of your decisions, but equally as important is the quality of your thoughts.

Critical thinking is an excellent tool to help you better understand yourself and to learn to master your thoughts.

You can use critical thinking to free yourself from cognitive biases, negative thinking , and limiting beliefs that are holding you back in any area of your life.

Critical thinking can help you assess your strengths and weaknesses so that you know what you have to offer others and where you could use improvement.

Critical thinking will enable you to better express your thoughts, ideas, and beliefs.

Better communication helps others to understand you better, resulting in less frustration for both of you.

Critical thinking fosters creativity and out-of-the-box thinking that can be applied to any area of your life.

It gives you a process you can rely on, making decisions less stressful.

4. Critical Thinking Ensures That Your Opinions Are Well-Informed

We have access to more information than ever before .

Astoundingly, more data has been created in the past two years than in the entire previous history of mankind.

Critical thinking can help you sort through the noise.

American politician, sociologist, and diplomat Daniel Patrick Moynihan once remarked , “You are entitled to your opinion. But you are not entitled to your own facts.”

Critical thinking ensures your opinions are well-informed and based on the best available facts.

You’ll get a boost in confidence when you see that those around you trust your well-considered opinions.

5. Critical Thinking Improves Relationships

You might be concerned that critical thinking will turn you into a Spock-like character who is not very good at relationships.

But, in fact, the opposite is true.

Employing critical thinking makes you more open-minded and better able to understand others’ points of view.

Critical thinkers are more empathetic and in a better position to get along with different kinds of people.

Critical thinking keeps you from jumping to conclusions.

You can be counted on to be the voice of reason when arguments get heated.

You’ll be better able to detect when others:

- are being disingenuous

- don’t have your best interests at heart

- try to take advantage of or manipulate you

6. Critical Thinking Makes You a Better, More Informed Citizen

“An educated citizenry is a vital requisite for our survival as a free people.”

This quote has been incorrectly attributed to Thomas Jefferson , but regardless of the source, these words of wisdom are more relevant than ever.

Critical thinkers are able to see both sides of any issue and are more likely to generate bipartisan solutions.

They are less likely to be swayed by propaganda or get swept up in mass hysteria.

They are in a better position to spot fake news when they see it.

5 Steps to Improve Your Critical Thinking Skills

Some people already have well-developed critical thinking skills.

These people are analytical, inquisitive, and open to new ideas.

And, even though they are confident in their own opinions, they seek the truth, even if it proves their existing ideas to be wrong.

They are able to connect the dots between ideas and detect inconsistencies in others’ thinking.

But regardless of the state of your critical thinking skills today, it’s a skill set you can develop.

While there are many techniques for thinking rationally, here’s a classic 5-step critical thinking process .

How to Improve Your Critical Thinking Skills

Clearly define your question or problem.

This step is so important that Albert Einstein famously quipped:

“If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.”

Gather Information to Help You Weigh the Options

Consider only the most useful and reliable information from the most reputable sources.

Disregard the rest.

Apply the Information and Ask Critical Questions

Scrutinize all information carefully with a skeptic’s eye.

Not sure what questions to ask?

You can’t go wrong starting with the “5 Ws” that any good investigator asks: Who? What? Where? When? Why?

Then finish by asking “How?”

You’ll find more thought-provoking questions on this Critical Thinking Skills Cheatsheet .

Consider the Implications

Look for potential unintended consequences.

Do a thought experiment about how your solution could play out in both the short term and the long run.

Explore the Full Spectrum of Viewpoints

Examine why others are drawn to differing points of view.

This will help you objectively evaluate your own viewpoint.

You may find critical thinkers who take an opposing view and this can help you find gaps in your own logic.

Watch the Video

This TED-Ed video on YouTube elaborates on the five steps to improve your critical thinking.

Recommended: Upgrading brain health is key to making your brain work better.

- Improve your mental clarity and focus.

- Boost your memory and your ability to learn.

- Increase your capacity to think critically, solve problems, and make decisions.

P.S. Like what you've read on this page? Get more like this -- Sign up for our emails .

ANA Nursing Resources Hub

Search Resources Hub

Critical Thinking in Nursing: Tips to Develop the Skill

4 min read • February, 09 2024

Critical thinking in nursing helps caregivers make decisions that lead to optimal patient care. In school, educators and clinical instructors introduced you to critical-thinking examples in nursing. These educators encouraged using learning tools for assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Nurturing these invaluable skills continues once you begin practicing. Critical thinking is essential to providing quality patient care and should continue to grow throughout your nursing career until it becomes second nature.

What Is Critical Thinking in Nursing?

Critical thinking in nursing involves identifying a problem, determining the best solution, and implementing an effective method to resolve the issue using clinical decision-making skills.

Reflection comes next. Carefully consider whether your actions led to the right solution or if there may have been a better course of action.

Remember, there's no one-size-fits-all treatment method — you must determine what's best for each patient.

How Is Critical Thinking Important for Nurses?

As a patient's primary contact, a nurse is typically the first to notice changes in their status. One example of critical thinking in nursing is interpreting these changes with an open mind. Make impartial decisions based on evidence rather than opinions. By applying critical-thinking skills to anticipate and understand your patients' needs, you can positively impact their quality of care and outcomes.

Elements of Critical Thinking in Nursing

To assess situations and make informed decisions, nurses must integrate these specific elements into their practice:

- Clinical judgment. Prioritize a patient's care needs and make adjustments as changes occur. Gather the necessary information and determine what nursing intervention is needed. Keep in mind that there may be multiple options. Use your critical-thinking skills to interpret and understand the importance of test results and the patient’s clinical presentation, including their vital signs. Then prioritize interventions and anticipate potential complications.

- Patient safety. Recognize deviations from the norm and take action to prevent harm to the patient. Suppose you don't think a change in a patient's medication is appropriate for their treatment. Before giving the medication, question the physician's rationale for the modification to avoid a potential error.

- Communication and collaboration. Ask relevant questions and actively listen to others while avoiding judgment. Promoting a collaborative environment may lead to improved patient outcomes and interdisciplinary communication.

- Problem-solving skills. Practicing your problem-solving skills can improve your critical-thinking skills. Analyze the problem, consider alternate solutions, and implement the most appropriate one. Besides assessing patient conditions, you can apply these skills to other challenges, such as staffing issues .

How to Develop and Apply Critical-Thinking Skills in Nursing

Critical-thinking skills develop as you gain experience and advance in your career. The ability to predict and respond to nursing challenges increases as you expand your knowledge and encounter real-life patient care scenarios outside of what you learned from a textbook.

Here are five ways to nurture your critical-thinking skills:

- Be a lifelong learner. Continuous learning through educational courses and professional development lets you stay current with evidence-based practice . That knowledge helps you make informed decisions in stressful moments.

- Practice reflection. Allow time each day to reflect on successes and areas for improvement. This self-awareness can help identify your strengths, weaknesses, and personal biases to guide your decision-making.

- Open your mind. Don't assume you're right. Ask for opinions and consider the viewpoints of other nurses, mentors , and interdisciplinary team members.

- Use critical-thinking tools. Structure your thinking by incorporating nursing process steps or a SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) to organize information, evaluate options, and identify underlying issues.

- Be curious. Challenge assumptions by asking questions to ensure current care methods are valid, relevant, and supported by evidence-based practice .

Critical thinking in nursing is invaluable for safe, effective, patient-centered care. You can successfully navigate challenges in the ever-changing health care environment by continually developing and applying these skills.

Images sourced from Getty Images

Related Resources

Item(s) added to cart

You are using an outdated browser

Unfortunately Ausmed.com does not support your browser. Please upgrade your browser to continue.

Cultivating Critical Thinking in Healthcare

Published: 06 January 2019

Critical thinking skills have been linked to improved patient outcomes, better quality patient care and improved safety outcomes in healthcare (Jacob et al. 2017).

Given this, it's necessary for educators in healthcare to stimulate and lead further dialogue about how these skills are taught , assessed and integrated into the design and development of staff and nurse education and training programs (Papp et al. 2014).

So, what exactly is critical thinking and how can healthcare educators cultivate it amongst their staff?

What is Critical Thinking?

In general terms, ‘ critical thinking ’ is often used, and perhaps confused, with problem-solving and clinical decision-making skills .

In practice, however, problem-solving tends to focus on the identification and resolution of a problem, whilst critical thinking goes beyond this to incorporate asking skilled questions and critiquing solutions .

Several formal definitions of critical thinking can be found in literature, but in the view of Kahlke and Eva (2018), most of these definitions have limitations. That said, Papp et al. (2014) offer a useful starting point, suggesting that critical thinking is:

‘The ability to apply higher order cognitive skills and the disposition to be deliberate about thinking that leads to action that is logical and appropriate.’

The Foundation for Critical Thinking (2017) expands on this and suggests that:

‘Critical thinking is that mode of thinking, about any subject, content, or problem, in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully analysing, assessing, and reconstructing it.’

They go on to suggest that critical thinking is:

- Self-directed

- Self-disciplined

- Self-monitored

- Self-corrective.

Key Qualities and Characteristics of a Critical Thinker

Given that critical thinking is a process that encompasses conceptualisation , application , analysis , synthesis , evaluation and reflection , what qualities should be expected from a critical thinker?

In answering this question, Fortepiani (2018) suggests that critical thinkers should be able to:

- Formulate clear and precise questions

- Gather, assess and interpret relevant information

- Reach relevant well-reasoned conclusions and solutions

- Think open-mindedly, recognising their own assumptions

- Communicate effectively with others on solutions to complex problems.

All of these qualities are important, however, good communication skills are generally considered to be the bedrock of critical thinking. Why? Because they help to create a dialogue that invites questions, reflections and an open-minded approach, as well as generating a positive learning environment needed to support all forms of communication.

Lippincott Solutions (2018) outlines a broad spectrum of characteristics attributed to strong critical thinkers. They include:

- Inquisitiveness with regard to a wide range of issues

- A concern to become and remain well-informed

- Alertness to opportunities to use critical thinking

- Self-confidence in one’s own abilities to reason

- Open mindedness regarding divergent world views

- Flexibility in considering alternatives and opinions

- Understanding the opinions of other people

- Fair-mindedness in appraising reasoning

- Honesty in facing one’s own biases, prejudices, stereotypes or egocentric tendencies

- A willingness to reconsider and revise views where honest reflection suggests that change is warranted.

Papp et al. (2014) also helpfully suggest that the following five milestones can be used as a guide to help develop competency in critical thinking:

Stage 1: Unreflective Thinker

At this stage, the unreflective thinker can’t examine their own actions and cognitive processes and is unaware of different approaches to thinking.

Stage 2: Beginning Critical Thinker

Here, the learner begins to think critically and starts to recognise cognitive differences in other people. However, external motivation is needed to sustain reflection on the learners’ own thought processes.

Stage 3: Practicing Critical Thinker

By now, the learner is familiar with their own thinking processes and makes a conscious effort to practice critical thinking.

Stage 4: Advanced Critical Thinker

As an advanced critical thinker, the learner is able to identify different cognitive processes and consciously uses critical thinking skills.

Stage 5: Accomplished Critical Thinker

At this stage, the skilled critical thinker can take charge of their thinking and habitually monitors, revises and rethinks approaches for continual improvement of their cognitive strategies.

Facilitating Critical Thinking in Healthcare

A common challenge for many educators and facilitators in healthcare is encouraging students to move away from passive learning towards active learning situations that require critical thinking skills.

Just as there are similarities among the definitions of critical thinking across subject areas and levels, there are also several generally recognised hallmarks of teaching for critical thinking . These include:

- Promoting interaction among students as they learn

- Asking open ended questions that do not assume one right answer

- Allowing sufficient time to reflect on the questions asked or problems posed

- Teaching for transfer - helping learners to see how a newly acquired skill can apply to other situations and experiences.

(Lippincott Solutions 2018)

Snyder and Snyder (2008) also make the point that it’s helpful for educators and facilitators to be aware of any initial resistance that learners may have and try to guide them through the process. They should aim to create a learning environment where learners can feel comfortable thinking through an answer rather than simply having an answer given to them.

Examples include using peer coaching techniques , mentoring or preceptorship to engage students in active learning and critical thinking skills, or integrating project-based learning activities that require students to apply their knowledge in a realistic healthcare environment.

Carvalhoa et al. (2017) also advocate problem-based learning as a widely used and successful way of stimulating critical thinking skills in the learner. This view is echoed by Tsui-Mei (2015), who notes that critical thinking, systematic analysis and curiosity significantly improve after practice-based learning .

Integrating Critical Thinking Skills Into Curriculum Design

Most educators agree that critical thinking can’t easily be developed if the program curriculum is not designed to support it. This means that a deep understanding of the nature and value of critical thinking skills needs to be present from the outset of the curriculum design process , and not just bolted on as an afterthought.

In the view of Fortepiani (2018), critical thinking skills can be summarised by the statement that 'thinking is driven by questions', which means that teaching materials need to be designed in such a way as to encourage students to expand their learning by asking questions that generate further questions and stimulate the thinking process. Ideal questions are those that:

- Embrace complexity

- Challenge assumptions and points of view

- Question the source of information

- Explore variable interpretations and potential implications of information.

To put it another way, asking questions with limiting, thought-stopping answers inhibits the development of critical thinking. This means that educators must ideally be critical thinkers themselves .

Drawing these threads together, The Foundation for Critical Thinking (2017) offers us a simple reminder that even though it’s human nature to be ‘thinking’ most of the time, most thoughts, if not guided and structured, tend to be biased, distorted, partial, uninformed or even prejudiced.

They also note that the quality of work depends precisely on the quality of the practitioners’ thought processes. Given that practitioners are being asked to meet the challenge of ever more complex care, the importance of cultivating critical thinking skills, alongside advanced problem-solving skills , seems to be taking on new importance.

Additional Resources

- The Emotionally Intelligent Nurse | Ausmed Article

- Refining Competency-Based Assessment | Ausmed Article

- Socratic Questioning in Healthcare | Ausmed Article

- Carvalhoa, D P S R P et al. 2017, 'Strategies Used for the Promotion of Critical Thinking in Nursing Undergraduate Education: A Systematic Review', Nurse Education Today , vol. 57, pp. 103-10, viewed 7 December 2018, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0260691717301715

- Fortepiani, L A 2017, 'Critical Thinking or Traditional Teaching For Health Professionals', PECOP Blog , 16 January, viewed 7 December 2018, https://blog.lifescitrc.org/pecop/2017/01/16/critical-thinking-or-traditional-teaching-for-health-professions/

- Jacob, E, Duffield, C & Jacob, D 2017, 'A Protocol For the Development of a Critical Thinking Assessment Tool for Nurses Using a Delphi Technique', Journal of Advanced Nursing, vol. 73, no. 8, pp. 1982-1988, viewed 7 December 2018, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jan.13306

- Kahlke, R & Eva, K 2018, 'Constructing Critical Thinking in Health Professional Education', Perspectives on Medical Education , vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 156-165, viewed 7 December 2018, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40037-018-0415-z

- Lippincott Solutions 2018, 'Turning New Nurses Into Critical Thinkers', Lippincott Solutions , viewed 10 December 2018, https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/turning-new-nurses-into-critical-thinkers

- Papp, K K 2014, 'Milestones of Critical Thinking: A Developmental Model for Medicine and Nursing', Academic Medicine , vol. 89, no. 5, pp. 715-720, https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2014/05000/Milestones_of_Critical_Thinking___A_Developmental.14.aspx

- Snyder, L G & Snyder, M J 2008, 'Teaching Critical Thinking and Problem Solving Skills', The Delta Pi Epsilon Journal , vol. L, no. 2, pp. 90-99, viewed 7 December 2018, https://dme.childrenshospital.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Optional-_Teaching-Critical-Thinking-and-Problem-Solving-Skills.pdf

- The Foundation for Critical Thinking 2017, Defining Critical Thinking , The Foundation for Critical Thinking, viewed 7 December 2018, https://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/our-conception-of-critical-thinking/411

- Tsui-Mei, H, Lee-Chun, H & Chen-Ju MSN, K 2015, 'How Mental Health Nurses Improve Their Critical Thinking Through Problem-Based Learning', Journal for Nurses in Professional Development , vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 170-175, viewed 7 December 2018, https://journals.lww.com/jnsdonline/Abstract/2015/05000/How_Mental_Health_Nurses_Improve_Their_Critical.8.aspx

Anne Watkins View profile

Help and feedback, publications.

Ausmed Education is a Trusted Information Partner of Healthdirect Australia. Verify here .

Critical Thinking in Medicine and Health

- First Online: 01 March 2020

Cite this chapter

- Louise Cummings 2

749 Accesses

1 Citations

This chapter addresses why there is a need for experts and lay people to think critically about medicine and health. It will be argued that illogical, misleading, and contradictory information in medicine and health can have pernicious consequences, including patient harm and poor compliance with health recommendations. Our cognitive resources are our only bulwark to the misinformation and faulty logic that exists in medicine and health. One resource in particular—reasoning—can counter the flawed thinking that pervades many medical and health issues. This chapter examines how concepts such as reasoning, logic and argument must be conceptualised somewhat differently (namely, in non-deductive terms) to accommodate the rationality of the informal fallacies. It also addresses the relevance of the informal fallacies to medicine and health and considers how these apparently defective arguments are a source of new analytical possibilities in both domains.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Albano, J. D., Ward, E., Jemal, A., Anderson, R., Cokkinides, V. E., Murray, T., et al. (2007). Cancer mortality in the United States by education level and race. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 99 (18), 1384–1394.

Article Google Scholar

Coxon, J., & Rees, J. (2015). Avoiding medical errors in general practice. Trends in Urology & Men’s Health, 6 (4), 13–17.

Google Scholar

Croskerry, P. (2003). The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Academic Medicine, 78 (8), 775–780.

Cummings, L. (2002). Reasoning under uncertainty: The role of two informal fallacies in an emerging scientific inquiry. Informal Logic, 22 (2), 113–136.

Cummings, L. (2004). Analogical reasoning as a tool of epidemiological investigation. Argumentation, 18 (4), 427–444.

Cummings, L. (2009). Emerging infectious diseases: Coping with uncertainty. Argumentation, 23 (2), 171–188.

Cummings, L. (2010). Rethinking the BSE crisis: A study of scientific reasoning under uncertainty . Dordrecht: Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Cummings, L. (2011). Considering risk assessment up close: The case of bovine spongiform encephalopathy. Health, Risk & Society, 13 (3), 255–275.

Cummings, L. (2012a). Scaring the public: Fear appeal arguments in public health reasoning. Informal Logic, 32 (1), 25–50.

Cummings, L. (2012b). The public health scientist as informal logician. International Journal of Public Health, 57 (3), 649–650.

Cummings, L. (2013a). Public health reasoning: Much more than deduction. Archives of Public Health, 71 (1), 25.

Cummings, L. (2013b). Circular reasoning in public health. Cogency, 5 (2), 35–76.

Cummings, L. (2014a). Informal fallacies as cognitive heuristics in public health reasoning. Informal Logic, 34 (1), 1–37.

Cummings, L. (2014b). The ‘trust’ heuristic: Arguments from authority in public health. Health Communication, 29 (10), 1043–1056.

Cummings, L. (2014c). Coping with uncertainty in public health: The use of heuristics. Public Health, 128 (4), 391–394.

Cummings, L. (2014d). Circles and analogies in public health reasoning. Inquiry, 29 (2), 35–59.

Cummings, L. (2014e). Analogical reasoning in public health. Journal of Argumentation in Context, 3 (2), 169–197.

Cummings, L. (2015). Reasoning and public health: New ways of coping with uncertainty . Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Fowler, F. J., Jr., Levin, C. A., & Sepucha, K. R. (2011). Informing and involving patients to improve the quality of medical decisions. Health Affairs, 30 (4), 699–706.

Graber, M. L., Franklin, N., & Gordon, R. (2005). Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165 (13), 1493–1499.

Hamblin, C. L. (1970). Fallacies . London: Methuen.

Johnson, R. H. (2011). Informal logic and deductivism. Studies in Logic, 4 (1), 17–37.

Kahane, H. (1971). Logic and contemporary rhetoric: The use of reason in everyday life . Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Loucks, E. B., Buka, S. L., Rogers, M. L., Liu, T., Kawachi, I., Kubzansky, L. D., et al. (2012). Education and coronary heart disease risk associations may be affected by early life common prior causes: A propensity matching analysis. Annals of Epidemiology, 22 (4), 221–232.

Saposnik, G., Redelmeier, D., Ruff, C. C., & Tobler, P. N. (2016). Cognitive biases associated with medical decisions: A systematic review. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 16, 138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0377-1 .

Trowbridge, R. L. (2008). Twelve tips for teaching avoidance of diagnostic errors. Medical Teacher, 30, 496–500.

Walton, D. N. (1985a). Are circular arguments necessarily vicious? American Philosophical Quarterly, 22 (4), 263–274.

Walton, D. N. (1985b). Arguer’s Position . Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Walton, D. N. (1987). The ad hominem argument as an informal fallacy. Argumentation, 1 (3), 317–331.

Walton, D. N. (1991). Begging the question: Circular reasoning as a tactic of argumentation . New York: Greenwood Press.

Walton, D. N. (1992). Plausible argument in everyday conversation . Albany: SUNY Press.

Walton, D. N. (1996). Argumentation schemes for presumptive reasoning . Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Walton, D. N. (2010). Why fallacies appear to be better arguments than they are. Informal Logic, 30 (2), 159–184.

Weingart, S. N., Wilson, R. M., Gibberd, R. W., & Harrison, B. (2000). Epidemiology of medical error. Western Journal of Medicine, 172 (6), 390–393.

Woods, J. (1995). Appeal to force. In H. V. Hansen & R. C. Pinto (Eds.), Fallacies: Classical and contemporary readings (pp. 240–250). University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Woods, J. (2004). The death of argument: Fallacies in agent-based reasoning . Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Woods, J. (2007). Lightening up on the ad hominem. Informal Logic, 27 (1), 109–134.

Woods, J. (2008). Begging the question is not a fallacy. In C. Dégremont, L. Keiff, & H. Rükert (Eds.), Dialogues, logics and other strange things: Essays in honour of Shahid Rahman (pp. 523–544). London: College Publications.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of English, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong

Louise Cummings

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Louise Cummings .

Chapter Summary

Medicine and health have tended to be overlooked in the critical thinking literature . And yet robust critical thinking skills are needed to evaluate the large number and range of health messages that we are exposed to on a daily basis.

An ability to think critically helps us to make better personal health choices and to uncover biases and errors in health messages and other information. An ability to think critically allows us to make informed decisions about medical treatments and is vital to efforts to reduce medical diagnostic errors.

A key element in critical thinking is the ability to distinguish strong or valid reasoning from weak or invalid reasoning. When an argument is weak or invalid, it is called a ‘fallacy’ or a ‘fallacious argument’.

The informal fallacies are so-called on account of the presence of epistemic and dialectical flaws that cannot be captured by formal logic . They have been discussed by many generations of philosophers and logicians , beginning with Aristotle .

Historically, philosophers and logicians have taken a pejorative view of the informal fallacies. Much of the criticism of these arguments is related to a latent deductivism in logic , the notion that arguments should be evaluated according to deductive standards of validity and soundness . Against deductive standards and norms, many reasonable arguments are judged to be fallacies.

Developments in logic , particularly the teaching of logic, forced a reconsideration of the prominence afforded to deductive logic in the evaluation of arguments. New criteria based on presumptive reasoning and plausible argument started to emerge. Against this backdrop, non-fallacious variants of most of the informal fallacies began to be described for the first time.

Today, some argument analysts characterize non-fallacious variants of the informal fallacies in terms of cognitive heuristics . During reasoning , these heuristics function as mental shortcuts, allowing us to bypass knowledge and come to judgement about complex health problems.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Sharples, J. M., Oxman, A. D., Mahtani, K. R., Chalmers, I., Oliver, S., Collins, K., Austvoll-Dahlgren, A., & Hoffmann, T. (2017). Critical thinking in healthcare and education. British Medical Journal, 357 : j2234. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j2234 .

The authors examine the role of critical thinking in medicine and healthcare, arguing that critical thinking skills are essential for doctors and patients. They describe an international project that involves collaboration between education and health. Its aim is to develop a curriculum and learning resources for critical thinking about any action that is claimed to improve health.

Hitchcock, D. (2017). On reasoning and argument: Essays in informal logic and on critical thinking . Cham: Switzerland: Springer.

This collection of essays provides more advanced reading on several of the topics addressed in this chapter, including the fallacies, informal logic , and the teaching of critical thinking . Chapter 25 considers if fallacies have a place in the teaching of critical thinking and reasoning skills.

Hansen, H. V., & Pinto, R. C. (Eds.). (1995). Fallacies: Classical and contemporary readings . University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

This edited collection of 24 chapters contains historical selections on the fallacies, contemporary theory and criticism, and analyses of specific fallacies. It also examines fallacies and teaching. There are chapters on four of the fallacies that will be examined in this book: appeal to force; appeal to ignorance ; appeal to authority; and post hoc ergo propter hoc .

Diagnostic errors are a significant cause of death and serious injury in patients. Many of these errors are related to cognitive factors. Trowbridge ( 2008 ) has devised twelve tips to familiarize medical students and physician trainees with the cognitive underpinnings of diagnostic errors. One of these tips is to explicitly describe heuristics and how they affect clinical reasoning . These heuristics include the following:

Representativeness —a patient’s presentation is compared to a ‘typical’ case of specific diagnoses.

Availability —physicians arrive at a diagnosis based on what is easily accessible in their minds, rather than what is actually most probable.

Anchoring —physicians may settle on a diagnosis early in the diagnostic process and subsequently become ‘anchored’ in that diagnosis.

Confirmation bias —as a result of anchoring, physicians may discount information discordant with the original diagnosis and accept only that which supports the diagnosis.

Using the above information, identify any heuristics and biases that occur in the following scenarios:

Scenario 1: A 60-year-old man has epigastric pain and nausea. He is sitting forward clutching his abdomen. He has a history of several bouts of alcoholic pancreatitis. He states that he felt similar during these bouts to what he is currently feeling. The patient states that he has had no alcohol in many years. He has normal blood levels of pancreatic enzymes. He is given a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. It is eventually discovered that he has had acute myocardial infarction.

Scenario 2: A 20-year-old, healthy man presents with sudden onset of severe, sharp chest pain and back pain. Based on these symptoms, he is suspected of having a dissecting thoracic aortic aneurysm. (In an aortic dissection, there is a separation of the layers within the wall of the aorta, the large blood vessel branching off the heart.) He is eventually diagnosed with pleuritis (inflammation of the pleura, the thin, transparent, two-layered membrane that covers the lungs).

Many of the logical terms that were introduced in this chapter also have non-logical uses in everyday language. Below are several examples of the use of these terms. For each example, indicate if the word in italics has a logical or a non - logical meaning or use:

University ‘safe spaces’ are a dangerous fallacy —they do not exist in the real world ( The Telegraph , 13 February 2017).

The MRI findings beg the question as to whether a careful ultrasound examination might have yielded some of the same information on haemorrhages ( British Medical Journal: Fetal & Neonatal , 2011).

The youth justice system is a slippery slope of failure ( The Sydney Morning Herald , 26 July 2016).

The EU countered with its own gastronomic analogy , saying that “cherry picking” the best bits of the EU would not be tolerated ( BBC News , 28 July 2017).

As Ebola spreads, so have several fallacies ( The New York Times , 23 October 2014).

Removing the statue of Confederacy Army General Robert E. Lee no more puts us on a slippery slope towards ousting far more nuanced figures from the public square than building the statue in the first place put us on a slippery slope toward, say, putting up statues of Hitler outside of Holocaust museums or of Ho Chi Minh at Vietnam War memorials ( Chicago Tribune , 16 August 2017).

We can expand the analogy a bit and think of a culture as something akin to a society’s immune system—it works best when it is exposed to as many foreign bodies as possible ( New Zealand Herald , 4 May 2010).

The Josh Norman Bowl begs the question : What’s an elite cornerback worth? ( The Washington Post , 17 December 2016).

The intuition behind these analogies is simple: As a homeowner, I generally have the right to exclude whoever I want from my property. I don’t even have to have a good justification for the exclusion. I can choose to bar you from my home for virtually any reason I want, or even just no reason at all. Similarly, a nation has the right to bar foreigners from its land for almost any reason it wants, or perhaps even no reason at all ( The Washington Post , 6 August 2017).

Legalising assisted suicide is a slippery slope toward widespread killing of the sick, Members of Parliament and peers were told yesterday ( Mail Online , 9 July 2014).

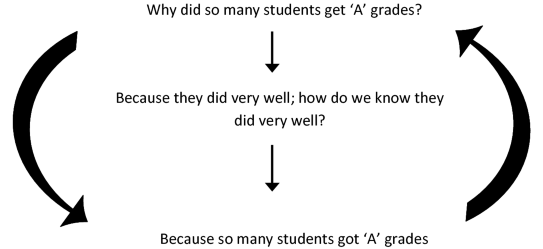

In the Special Topic ‘What’s in a name?’, an example of a question-begging argument from the author’s recent personal experience was used. How would you reconstruct the argument in this case to illustrate the presence of a fallacy?

On 9 July 2017, the effect of coconut oil on health was also discussed in an article in The Guardian entitled ‘Coconut oil: Are the health benefits a big fat lie?’ The following extract is taken from that article. (a) What type of reasoning is the author using in this extract? In your response, you should reconstruct the argument by presenting its premises and conclusion . Also, is this argument valid or fallacious in this particular context?

When it comes to superfoods, coconut oil presses all the buttons: it’s natural, it’s enticingly exotic, it’s surrounded by health claims and at up to £8 for a 500 ml pot at Tesco, it’s suitably pricey. But where this latest superfood differs from benign rivals such as blueberries, goji berries, kale and avocado is that a diet rich in coconut oil may actually be bad for us.

The article in The Guardian also makes extensive use of expert opinion. Two such opinions are shown below. (b) What three linguistic devices does the author use to confer expertise or authority on the individuals who advance these opinions?

Christine Williams, professor of human nutrition at the University of Reading, states: “There is very limited evidence of beneficial health effects of this oil”.

Tom Sanders, emeritus professor of nutrition and dietetics at King’s College London, says: “It is a poor source of vitamin E compared with other vegetable oils”.

The author of the article in The Guardian went on to summarize the findings of a study by two researchers that was published in the British Nutrition Foundation’s Nutrition Bulletin. The author’s summary included the following statement: There is no good evidence that coconut oil helps boost mental performance or prevent Alzheimer’s disease . (c) In what type of informal fallacy might this statement be a premise ?

Scenario 1: An anchoring error has occurred in which the patient is given a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis early in the diagnostic process. The clinician becomes anchored in this diagnosis, with the result that he overlooks two pieces of information that would have allowed this diagnosis to be disconfirmed—the fact that the patient has reported no alcohol use in many years and the presence of normal blood levels of pancreatic enzymes. By dismissing this information, the clinician is also showing a confirmation bias —he attends only to information that confirms his original diagnosis.

Scenario 2: A representativeness error has occurred. The patient’s presentation is typical of aortic dissection. However, this condition can be dismissed in favour of conditions like pleuritis or pneumothorax on account of the fact that aortic dissection is exceptionally rare in 20-year-olds.

(2) (a) non-logical; (b) non-logical; (c) non-logical; (d) non-logical; (e) non-logical; (f) logical; (g) logical; (h) non-logical; (i) logical; (j) logical

(3) The fallacy can be illustrated as follows. The head of department asks the question ‘Why did so many of these students get ‘A’ grades’? He receives the reply ‘Because they did very well’. But someone might reasonably ask ‘How do we know that they did very well?’ To which the reply is ‘Because so many students got ‘A’ grades’. The reasoning can be reconstructed in diagram form as follows:

The author is using an analogical argument , which has the following form:

P1: Blueberries, goji berries, kale, avocado and coconut oil are natural, exotic, pricey and surrounded by health claims.

P2: Blueberries, goji berries, kale and avocado have health benefits.

C: Coconut oil has health benefits.

This is a false analogy , or a fallacious analogical argument , because coconut oil does not share with these other superfoods the property or attribute < has health benefits >.

The author uses academic rank, field of specialization, and university affiliation to confer authority or expertise on individuals who advance expert opinions.

This statement could be a premise in an argument from ignorance .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cummings, L. (2020). Critical Thinking in Medicine and Health. In: Fallacies in Medicine and Health. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28513-5_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28513-5_1

Published : 01 March 2020

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-28512-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-28513-5

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

How do critical thinking ability and critical thinking disposition relate to the mental health of university students.

- School of Education, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China

Theories of psychotherapy suggest that human mental problems associate with deficiencies in critical thinking. However, it currently remains unclear whether both critical thinking skill and critical thinking disposition relate to individual differences in mental health. This study explored whether and how the critical thinking ability and critical thinking disposition of university students associate with individual differences in mental health in considering impulsivity that has been revealed to be closely related to both critical thinking and mental health. Regression and structural equation modeling analyses based on a Chinese university student sample ( N = 314, 198 females, M age = 18.65) revealed that critical thinking skill and disposition explained a unique variance of mental health after controlling for impulsivity. Furthermore, the relationship between critical thinking and mental health was mediated by motor impulsivity (acting on the spur of the moment) and non-planning impulsivity (making decisions without careful forethought). These findings provide a preliminary account of how human critical thinking associate with mental health. Practically, developing mental health promotion programs for university students is suggested to pay special attention to cultivating their critical thinking dispositions and enhancing their control over impulsive behavior.

Introduction

Although there is no consistent definition of critical thinking (CT), it is usually described as “purposeful, self-regulatory judgment that results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanations of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations that judgment is based upon” ( Facione, 1990 , p. 2). This suggests that CT is a combination of skills and dispositions. The skill aspect mainly refers to higher-order cognitive skills such as inference, analysis, and evaluation, while the disposition aspect represents one's consistent motivation and willingness to use CT skills ( Dwyer, 2017 ). An increasing number of studies have indicated that CT plays crucial roles in the activities of university students such as their academic performance (e.g., Ghanizadeh, 2017 ; Ren et al., 2020 ), professional work (e.g., Barry et al., 2020 ), and even the ability to cope with life events (e.g., Butler et al., 2017 ). An area that has received less attention is how critical thinking relates to impulsivity and mental health. This study aimed to clarify the relationship between CT (which included both CT skill and CT disposition), impulsivity, and mental health among university students.

Relationship Between Critical Thinking and Mental Health

Associating critical thinking with mental health is not without reason, since theories of psychotherapy have long stressed a linkage between mental problems and dysfunctional thinking ( Gilbert, 2003 ; Gambrill, 2005 ; Cuijpers, 2019 ). Proponents of cognitive behavioral therapy suggest that the interpretation by people of a situation affects their emotional, behavioral, and physiological reactions. Those with mental problems are inclined to bias or heuristic thinking and are more likely to misinterpret neutral or even positive situations ( Hollon and Beck, 2013 ). Therefore, a main goal of cognitive behavioral therapy is to overcome biased thinking and change maladaptive beliefs via cognitive modification skills such as objective understanding of one's cognitive distortions, analyzing evidence for and against one's automatic thinking, or testing the effect of an alternative way of thinking. Achieving these therapeutic goals requires the involvement of critical thinking, such as the willingness and ability to critically analyze one's thoughts and evaluate evidence and arguments independently of one's prior beliefs. In addition to theoretical underpinnings, characteristics of university students also suggest a relationship between CT and mental health. University students are a risky population in terms of mental health. They face many normative transitions (e.g., social and romantic relationships, important exams, financial pressures), which are stressful ( Duffy et al., 2019 ). In particular, the risk increases when students experience academic failure ( Lee et al., 2008 ; Mamun et al., 2021 ). Hong et al. (2010) found that the stress in Chinese college students was primarily related to academic, personal, and negative life events. However, university students are also a population with many resources to work on. Critical thinking can be considered one of the important resources that students are able to use ( Stupple et al., 2017 ). Both CT skills and CT disposition are valuable qualities for college students to possess ( Facione, 1990 ). There is evidence showing that students with a higher level of CT are more successful in terms of academic performance ( Ghanizadeh, 2017 ; Ren et al., 2020 ), and that they are better at coping with stressful events ( Butler et al., 2017 ). This suggests that that students with higher CT are less likely to suffer from mental problems.

Empirical research has reported an association between CT and mental health among college students ( Suliman and Halabi, 2007 ; Kargar et al., 2013 ; Yoshinori and Marcus, 2013 ; Chen and Hwang, 2020 ; Ugwuozor et al., 2021 ). Most of these studies focused on the relationship between CT disposition and mental health. For example, Suliman and Halabi (2007) reported that the CT disposition of nursing students was positively correlated with their self-esteem, but was negatively correlated with their state anxiety. There is also a research study demonstrating that CT disposition influenced the intensity of worry in college students either by increasing their responsibility to continue thinking or by enhancing the detached awareness of negative thoughts ( Yoshinori and Marcus, 2013 ). Regarding the relationship between CT ability and mental health, although there has been no direct evidence, there were educational programs examining the effect of teaching CT skills on the mental health of adolescents ( Kargar et al., 2013 ). The results showed that teaching CT skills decreased somatic symptoms, anxiety, depression, and insomnia in adolescents. Another recent CT skill intervention also found a significant reduction in mental stress among university students, suggesting an association between CT skills and mental health ( Ugwuozor et al., 2021 ).

The above research provides preliminary evidence in favor of the relationship between CT and mental health, in line with theories of CT and psychotherapy. However, previous studies have focused solely on the disposition aspect of CT, and its link with mental health. The ability aspect of CT has been largely overlooked in examining its relationship with mental health. Moreover, although the link between CT and mental health has been reported, it remains unknown how CT (including skill and disposition) is associated with mental health.

Impulsivity as a Potential Mediator Between Critical Thinking and Mental Health

One important factor suggested by previous research in accounting for the relationship between CT and mental health is impulsivity. Impulsivity is recognized as a pattern of action without regard to consequences. Patton et al. (1995) proposed that impulsivity is a multi-faceted construct that consists of three behavioral factors, namely, non-planning impulsiveness, referring to making a decision without careful forethought; motor impulsiveness, referring to acting on the spur of the moment; and attentional impulsiveness, referring to one's inability to focus on the task at hand. Impulsivity is prominent in clinical problems associated with psychiatric disorders ( Fortgang et al., 2016 ). A number of mental problems are associated with increased impulsivity that is likely to aggravate clinical illnesses ( Leclair et al., 2020 ). Moreover, a lack of CT is correlated with poor impulse control ( Franco et al., 2017 ). Applications of CT may reduce impulsive behaviors caused by heuristic and biased thinking when one makes a decision ( West et al., 2008 ). For example, Gregory (1991) suggested that CT skills enhance the ability of children to anticipate the health or safety consequences of a decision. Given this, those with high levels of CT are expected to take a rigorous attitude about the consequences of actions and are less likely to engage in impulsive behaviors, which may place them at a low risk of suffering mental problems. To the knowledge of the authors, no study has empirically tested whether impulsivity accounts for the relationship between CT and mental health.

This study examined whether CT skill and disposition are related to the mental health of university students; and if yes, how the relationship works. First, we examined the simultaneous effects of CT ability and CT disposition on mental health. Second, we further tested whether impulsivity mediated the effects of CT on mental health. To achieve the goals, we collected data on CT ability, CT disposition, mental health, and impulsivity from a sample of university students. The results are expected to shed light on the mechanism of the association between CT and mental health.

Participants and Procedure

A total of 314 university students (116 men) with an average age of 18.65 years ( SD = 0.67) participated in this study. They were recruited by advertisements from a local university in central China and majoring in statistics and mathematical finance. The study protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee of the Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Each participant signed a written informed consent describing the study purpose, procedure, and right of free. All the measures were administered in a computer room. The participants were tested in groups of 20–30 by two research assistants. The researchers and research assistants had no formal connections with the participants. The testing included two sections with an interval of 10 min, so that the participants had an opportunity to take a break. In the first section, the participants completed the syllogistic reasoning problems with belief bias (SRPBB), the Chinese version of the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCSTS-CV), and the Chinese Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (CCTDI), respectively. In the second session, they completed the Barrett Impulsivity Scale (BIS-11), Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21), and University Personality Inventory (UPI) in the given order.

Measures of Critical Thinking Ability

The Chinese version of the California Critical Thinking Skills Test was employed to measure CT skills ( Lin, 2018 ). The CCTST is currently the most cited tool for measuring CT skills and includes analysis, assessment, deduction, inductive reasoning, and inference reasoning. The Chinese version included 34 multiple choice items. The dependent variable was the number of correctly answered items. The internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the CCTST is 0.56 ( Jacobs, 1995 ). The test–retest reliability of CCTST-CV is 0.63 ( p < 0.01) ( Luo and Yang, 2002 ), and correlations between scores of the subscales and the total score are larger than 0.5 ( Lin, 2018 ), supporting the construct validity of the scale. In this study among the university students, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the CCTST-CV was 0.5.

The second critical thinking test employed in this study was adapted from the belief bias paradigm ( Li et al., 2021 ). This task paradigm measures the ability to evaluate evidence and arguments independently of one's prior beliefs ( West et al., 2008 ), which is a strongly emphasized skill in CT literature. The current test included 20 syllogistic reasoning problems in which the logical conclusion was inconsistent with one's prior knowledge (e.g., “Premise 1: All fruits are sweet. Premise 2: Bananas are not sweet. Conclusion: Bananas are not fruits.” valid conclusion). In addition, four non-conflict items were included as the neutral condition in order to avoid a habitual response from the participants. They were instructed to suppose that all the premises are true and to decide whether the conclusion logically follows from the given premises. The measure showed good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.83) in a Chinese sample ( Li et al., 2021 ). In this study, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the SRPBB was 0.94.

Measures of Critical Thinking Disposition

The Chinese Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory was employed to measure CT disposition ( Peng et al., 2004 ). This scale has been developed in line with the conceptual framework of the California critical thinking disposition inventory. We measured five CT dispositions: truth-seeking (one's objectivity with findings even if this requires changing one's preconceived opinions, e.g., a person inclined toward being truth-seeking might disagree with “I believe what I want to believe.”), inquisitiveness (one's intellectual curiosity. e.g., “No matter what the topic, I am eager to know more about it”), analyticity (the tendency to use reasoning and evidence to solve problems, e.g., “It bothers me when people rely on weak arguments to defend good ideas”), systematically (the disposition of being organized and orderly in inquiry, e.g., “I always focus on the question before I attempt to answer it”), and CT self-confidence (the trust one places in one's own reasoning processes, e.g., “I appreciate my ability to think precisely”). Each disposition aspect contained 10 items, which the participants rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale. This measure has shown high internal consistency (overall Cronbach's α = 0.9) ( Peng et al., 2004 ). In this study, the CCTDI scale was assessed at Cronbach's α = 0.89, indicating good reliability.

Measure of Impulsivity

The well-known Barrett Impulsivity Scale ( Patton et al., 1995 ) was employed to assess three facets of impulsivity: non-planning impulsivity (e.g., “I plan tasks carefully”); motor impulsivity (e.g., “I act on the spur of the moment”); attentional impulsivity (e.g., “I concentrate easily”). The scale includes 30 statements, and each statement is rated on a 5-point scale. The subscales of non-planning impulsivity and attentional impulsivity were reversely scored. The BIS-11 has good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.81, Velotti et al., 2016 ). This study showed that the Cronbach's α of the BIS-11 was 0.83.

Measures of Mental Health

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 was used to assess mental health problems such as depression (e.g., “I feel that life is meaningless”), anxiety (e.g., “I find myself getting agitated”), and stress (e.g., “I find it difficult to relax”). Each dimension included seven items, which the participants were asked to rate on a 4-point scale. The Chinese version of the DASS-21 has displayed a satisfactory factor structure and internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.92, Wang et al., 2016 ). In this study, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the DASS-21 was 0.94.

The University Personality Inventory that has been commonly used to screen for mental problems of college students ( Yoshida et al., 1998 ) was also used for measuring mental health. The 56 symptom-items assessed whether an individual has experienced the described symptom during the past year (e.g., “a lack of interest in anything”). The UPI showed good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.92) in a Chinese sample ( Zhang et al., 2015 ). This study showed that the Cronbach's α of the UPI was 0.85.

Statistical Analyses

We first performed analyses to detect outliers. Any observation exceeding three standard deviations from the means was replaced with a value that was three standard deviations. This procedure affected no more than 5‰ of observations. Hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to determine the extent to which facets of critical thinking were related to mental health. In addition, structural equation modeling with Amos 22.0 was performed to assess the latent relationship between CT, impulsivity, and mental health.

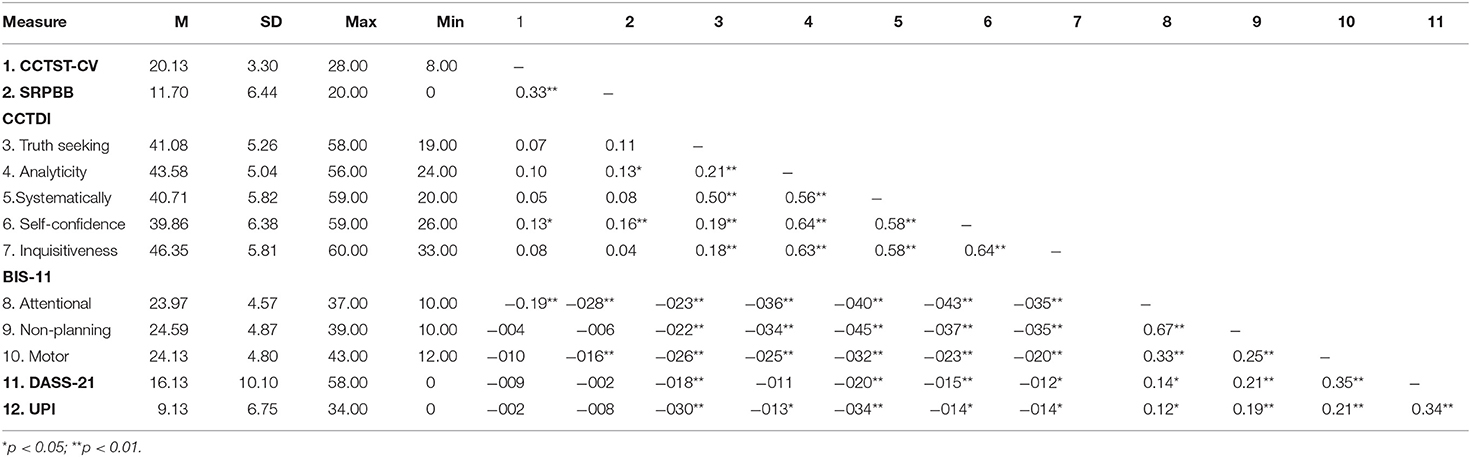

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of all the variables. CT disposition such as truth-seeking, systematicity, self-confidence, and inquisitiveness was significantly correlated with DASS-21 and UPI, but neither CCTST-CV nor SRPBB was related to DASS-21 and UPI. Subscales of BIS-11 were positively correlated with DASS-21 and UPI, but were negatively associated with CT dispositions.

Table 1 . Descriptive results and correlations between all measured variables ( N = 314).

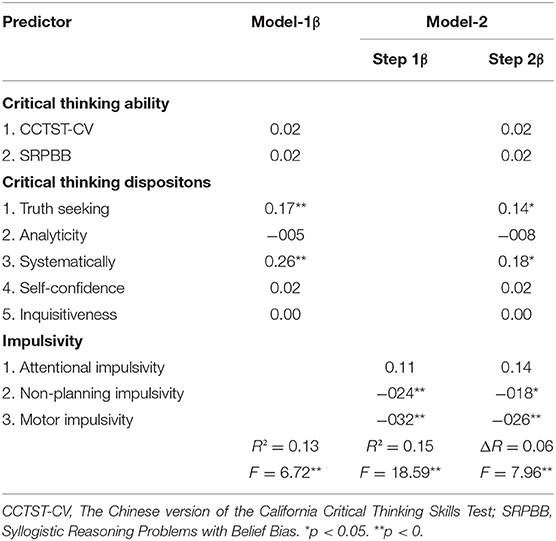

Regression Analyses

Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine the effects of CT skill and disposition on mental health. Before conducting the analyses, scores in DASS-21 and UPI were reversed so that high scores reflected high levels of mental health. Table 2 presents the results of hierarchical regression. In model 1, the sum of the Z-score of DASS-21 and UPI served as the dependent variable. Scores in the CT ability tests and scores in the five dimensions of CCTDI served as predictors. CT skill and disposition explained 13% of the variance in mental health. CT skills did not significantly predict mental health. Two dimensions of dispositions (truth seeking and systematicity) exerted significantly positive effects on mental health. Model 2 examined whether CT predicted mental health after controlling for impulsivity. The model containing only impulsivity scores (see model-2 step 1 in Table 2 ) explained 15% of the variance in mental health. Non-planning impulsivity and motor impulsivity showed significantly negative effects on mental health. The CT variables on the second step explained a significantly unique variance (6%) of CT (see model-2 step 2). This suggests that CT skill and disposition together explained the unique variance in mental health after controlling for impulsivity. 1

Table 2 . Hierarchical regression models predicting mental health from critical thinking skills, critical thinking dispositions, and impulsivity ( N = 314).

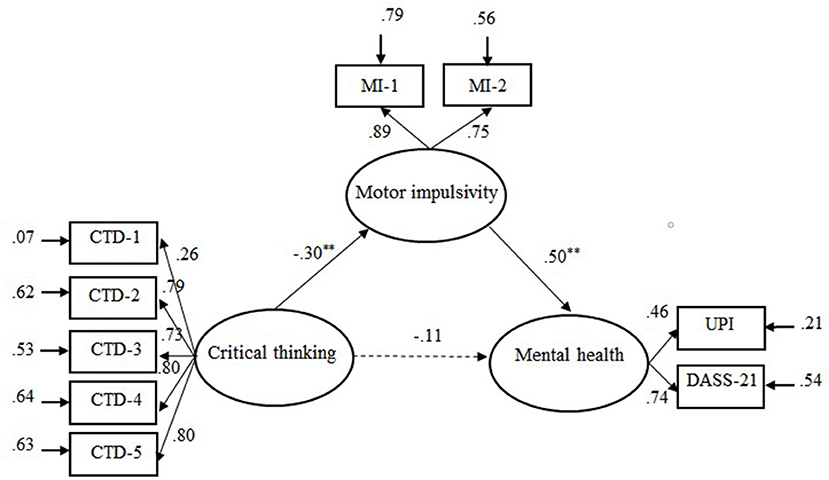

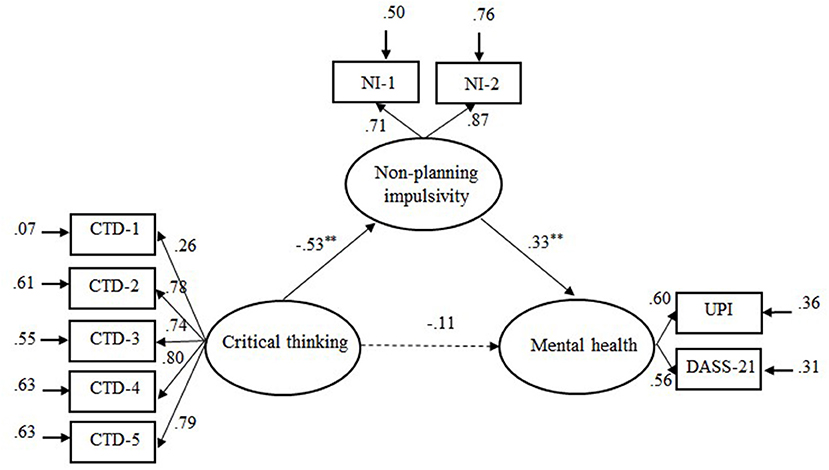

Structural equation modeling was performed to examine whether impulsivity mediated the relationship between CT disposition (CT ability was not included since it did not significantly predict mental health) and mental health. Since the regression results showed that only motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity significantly predicted mental health, we examined two mediation models with either motor impulsivity or non-planning impulsivity as the hypothesized mediator. The item scores in the motor impulsivity subscale were randomly divided into two indicators of motor impulsivity, as were the scores in the non-planning subscale. Scores of DASS-21 and UPI served as indicators of mental health and dimensions of CCTDI as indicators of CT disposition. In addition, a bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 resamples was established to test for direct and indirect effects. Amos 22.0 was used for the above analyses.

The mediation model that included motor impulsivity (see Figure 1 ) showed an acceptable fit, χ ( 23 ) 2 = 64.71, RMSEA = 0.076, CFI = 0.96, GFI = 0.96, NNFI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.073. Mediation analyses indicated that the 95% boot confidence intervals of the indirect effect and the direct effect were (0.07, 0.26) and (−0.08, 0.32), respectively. As Hayes (2009) indicates, an effect is significant if zero is not between the lower and upper bounds in the 95% confidence interval. Accordingly, the indirect effect between CT disposition and mental health was significant, while the direct effect was not significant. Thus, motor impulsivity completely mediated the relationship between CT disposition and mental health.

Figure 1 . Illustration of the mediation model: Motor impulsivity as mediator variable between critical thinking dispositions and mental health. CTD-l = Truth seeking; CTD-2 = Analyticity; CTD-3 = Systematically; CTD-4 = Self-confidence; CTD-5 = Inquisitiveness. MI-I and MI-2 were sub-scores of motor impulsivity. Solid line represents significant links and dotted line non-significant links. ** p < 0.01.

The mediation model, which included non-planning impulsivity (see Figure 2 ), also showed an acceptable fit to the data, χ ( 23 ) 2 = 52.75, RMSEA = 0.064, CFI = 0.97, GFI = 0.97, NNFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.06. The 95% boot confidence intervals of the indirect effect and the direct effect were (0.05, 0.33) and (−0.04, 0.38), respectively, indicating that non-planning impulsivity completely mediated the relationship between CT disposition and mental health.

Figure 2 . Illustration of the mediation model: Non-planning impulsivity asmediator variable between critical thinking dispositions and mental health. CTD-l = Truth seeking; CTD-2 = Analyticity; CTD-3 = Systematically; CTD-4 = Self-confidence; CTD-5 = Inquisitiveness. NI-I and NI-2 were sub-scores of Non-planning impulsivity. Solid line represents significant links and dotted line non-significant links. ** p < 0.01.

This study examined how critical thinking skill and disposition are related to mental health. Theories of psychotherapy suggest that human mental problems are in part due to a lack of CT. However, empirical evidence for the hypothesized relationship between CT and mental health is relatively scarce. This study explored whether and how CT ability and disposition are associated with mental health. The results, based on a university student sample, indicated that CT skill and disposition explained a unique variance in mental health. Furthermore, the effect of CT disposition on mental health was mediated by motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity. The finding that CT exerted a significant effect on mental health was in accordance with previous studies reporting negative correlations between CT disposition and mental disorders such as anxiety ( Suliman and Halabi, 2007 ). One reason lies in the assumption that CT disposition is usually referred to as personality traits or habits of mind that are a remarkable predictor of mental health (e.g., Benzi et al., 2019 ). This study further found that of the five CT dispositions, only truth-seeking and systematicity were associated with individual differences in mental health. This was not surprising, since the truth-seeking items mainly assess one's inclination to crave for the best knowledge in a given context and to reflect more about additional facts, reasons, or opinions, even if this requires changing one's mind about certain issues. The systematicity items target one's disposition to approach problems in an orderly and focused way. Individuals with high levels of truth-seeking and systematicity are more likely to adopt a comprehensive, reflective, and controlled way of thinking, which is what cognitive therapy aims to achieve by shifting from an automatic mode of processing to a more reflective and controlled mode.

Another important finding was that motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity mediated the effect of CT disposition on mental health. The reason may be that people lacking CT have less willingness to enter into a systematically analyzing process or deliberative decision-making process, resulting in more frequently rash behaviors or unplanned actions without regard for consequences ( Billieux et al., 2010 ; Franco et al., 2017 ). Such responses can potentially have tangible negative consequences (e.g., conflict, aggression, addiction) that may lead to social maladjustment that is regarded as a symptom of mental illness. On the contrary, critical thinkers have a sense of deliberativeness and consider alternate consequences before acting, and this thinking-before-acting mode would logically lead to a decrease in impulsivity, which then decreases the likelihood of problematic behaviors and negative moods.

It should be noted that although the raw correlation between attentional impulsivity and mental health was significant, regression analyses with the three dimensions of impulsivity as predictors showed that attentional impulsivity no longer exerted a significant effect on mental effect after controlling for the other impulsivity dimensions. The insignificance of this effect suggests that the significant raw correlation between attentional impulsivity and mental health was due to the variance it shared with the other impulsivity dimensions (especially with the non-planning dimension, which showed a moderately high correlation with attentional impulsivity, r = 0.67).

Some limitations of this study need to be mentioned. First, the sample involved in this study is considered as a limited sample pool, since all the participants are university students enrolled in statistics and mathematical finance, limiting the generalization of the findings. Future studies are recommended to recruit a more representative sample of university students. A study on generalization to a clinical sample is also recommended. Second, as this study was cross-sectional in nature, caution must be taken in interpreting the findings as causal. Further studies using longitudinal, controlled designs are needed to assess the effectiveness of CT intervention on mental health.