Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 4: Understanding People at Work: Individual Differences and Perception

Understanding people at work: individual differences and perception.

Individuals bring a number of differences to work, such as unique personalities, values, emotions, and moods. When new employees enter organizations, their stable or transient characteristics affect how they behave and perform. Moreover, companies hire people with the expectation that those individuals have certain skills, abilities, personalities, and values. Therefore, it is important to understand individual characteristics that matter for employee behaviors at work.

Advice for Hiring Successful Employees: The Case of Guy Kawasaki

When people think about entrepreneurship, they often think of Guy Kawasaki , who is a Silicon Valley venture capitalist and the author of nine books as of 2010, including The Art of the Start and The Macintosh Way . Beyond being a best-selling author, he has been successful in a variety of areas, including earning degrees from Stanford University and UCLA; being an integral part of Apple’s first computer; writing columns for Forbes and Entrepreneur Magazine ; and taking on entrepreneurial ventures such as cofounding Alltop, an aggregate news site, and becoming managing director of Garage Technology Ventures. Kawasaki is a believer in the power of individual differences. He believes that successful companies include people from many walks of life, with different backgrounds and with different strengths and different weaknesses. Establishing an effective team requires a certain amount of self-monitoring on the part of the manager. Kawasaki maintains that most individuals have personalities that can easily get in the way of this objective. He explains, “The most important thing is to hire people who complement you and are better than you in specific areas. Good people hire people that are better than them- selves.” He also believes that mediocre employees hire less-talented employees in order to feel better about themselves. Finally, he believes that the role of a leader is to produce more leaders, not to produce followers, and to be able to achieve this, a leader should compensate for their weaknesses by hiring individuals who compensate for their shortcomings.

In today’s competitive business environment, individuals want to think of themselves as indispensable to the success of an organization. Because an individual’s perception that he or she is the most important person on a team can get in the way, Kawasaki maintains that many people would rather see a company fail than thrive without them. He advises that we must begin to move past this and to see the value that different perceptions and values can bring to a company, and the goal of any individual should be to make the organization that one works for stronger and more dynamic. Under this type of thinking, leaving a company in better shape than one found it becomes a source of pride. Kawasaki has had many different roles in his professional career and as a result realized that while different perceptions and attitudes might make the implementation of new protocol difficult, this same diversity is what makes an organization more valuable. Some managers fear diversity and the possible complexities that it brings, and they make the mistake of hiring similar individuals without any sort of differences. When it comes to hiring, Kawasaki believes that the initial round of inter- views for new hires should be held over the phone. Because first impressions are so important, this ensures that external influences, negative or positive, are not part of the decision-making process.

Many people come out of business school believing that if they have a solid financial understanding, then they will be a successful and appropriate leader and manager. Kawasaki has learned that mathematics and finance are the “easy” part of any job. He observes that the true challenge comes in trying to effectively man- age people. With the benefit of hindsight, Kawasaki regrets the choices he made in college, saying, “I should have taken organizational behavior and social psychology” to be better prepared for the individual nuances of people. He also believes that working hard is a key to success and that individuals who learn how to learn are the most effective over time.

If nothing else, Guy Kawasaki provides simple words of wisdom to remember when starting off on a new career path: do not allow mistakes to limit success, but rather take them as a lesson of what not to do. And most important, pursue joy and challenge your personal assumptions.

Based on information from Bryant, A. (2010, March 19). Just give him 5 sentences, not “War and Peace.” New York Times . Retrieved March 26, 2010; Kawasaki, G. (2004). The art of the start: The time-tested, battle-hardened guide for any- one starting anything . New York: Penguin Group; Iwata, E. (2008, November 10). Kawasaki doesn’t accept failure; promotes learning through mistakes. USA Today , p. 3B. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

The Interactionist Perspective: The Role of Fit

Individual differences matter in the workplace. Human beings bring in their personality, physical and mental abilities, and other stable traits to work. Imagine that you are interviewing an employee who is proactive, creative, and willing to take risks. Would this person be a good job candidate? What behaviors would you expect this person to demonstrate?

The question posed above is misleading. While human beings bring their traits to work, every organization is different, and every job within the organization is also different. According to the interactionist perspective, behavior is a function of the person and the situation interacting with each other. Think about it. Would a shy person speak up in class? While a shy person may not feel like speaking, if the individual is very interested in the subject, knows the answers to the questions, and feels comfortable within the classroom environment, and if the instructor encourages participation and participation is 30% of the course grade, regardless of the level of shyness, the person may feel inclined to participate. Similarly, the behavior you may expect from someone who is proactive, creative, and willing to take risks will depend on the situation.

When hiring employees, companies are interested in assessing at least two types of fit. Person–organization fit refers to the degree to which a person’s values, personality, goals, and other characteristics match those of the organization. Person–job fit is the degree to which a person’s skill, knowledge, abilities, and other characteristics match the job demands. Thus, someone who is proactive and creative may be a great fit for a company in the high-tech sector that would benefit from risk-taking individuals, but may be a poor fit for a company that rewards routine and predictable behavior, such as accountants. Similarly, this person may be a great fit for a job such as a scientist, but a poor fit for a routine office job. The opening case illustrates one method of assessing person–organization and person–job fit in job applicants.

The first thing many recruiters look at is the person–job fit. This is not surprising, because person–job fit is related to a number of positive work attitudes such as satisfaction with the work environment, identification with the organization, job satisfaction, and work behaviors such as job performance. Companies are often also interested in hiring candidates who will fit into the company culture (those with high person–organization fit). When people fit into their organization, they tend to be more satisfied with their jobs, more committed to their companies, and more influential in their company, and they actually remain longer in their company (Anderson, Spataro, & Flynn, 2008; Cable & DeRue, 2002; Caldwell & O’Reilly, 1990; Chatman, 1991; Judge & Cable, 1997; Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, & Johnson, 2005; O’Reilly, Chatman, & Caldwell, 1991; Saks & Ashforth, 2002). One area of controversy is whether these people perform better. Some studies have found a positive relationship between person–organization fit and job performance, but this finding was not present in all studies, so it seems that fitting with a company’s culture will only sometimes predict job performance (Arthur et al., 2006). It also seems that fit- ting in with the company culture is more important to some people than to others. For example, people who have worked in multiple companies tend to understand the impact of a company’s culture better, and therefore they pay more attention to whether they will fit in with the company when making their decisions (Kristof-Brown, Jansen, & Colbert, 2002). Also, when they build good relationships with their supervisors and the company, being a misfit does not seem to lead to dissatisfaction on the job (Erdogan, Kraimer, & Liden 2004).

Key Takeaway

While personality traits and other individual differences are important, we need to keep in mind that behavior is jointly determined by the person and the situation. Certain situations bring out the best in people, and someone who is a poor performer in one job may turn into a star employee in a different job.

Individual Differences: Values and Personality

Values refer to stable life goals that people have, reflecting what is most important to them. Values are established throughout one’s life as a result of the accumulating life experiences and tend to be relatively stable (Lusk & Oliver, 1974; Rokeach, 1973). The values that are important to people tend to affect the types of decisions they make, how they perceive their environment, and their actual behaviors. More- over, people are more likely to accept job offers when the company possesses the values people care about (Judge & Bretz, 1992; Ravlin & Meglino, 1987). Value attainment is one reason why people stay in a company, and when an organization does not help them attain their values, they are more likely to decide to leave if they are dissatisfied with the job itself (George & Jones, 1996).

What are the values people care about? There are many typologies of values. One of the most established surveys to assess individual values is the Rokeach Value Survey (Rokeach, 1973). This survey lists 18 terminal and 18 instrumental values in alphabetical order. Terminal values refer to end states people desire in life, such as leading a prosperous life and a world at peace. Instrumental values deal with views on acceptable modes of conduct, such as being honest and ethical, and being ambitious.

According to Rokeach, values are arranged in hierarchical fashion. In other words, an accurate way of assessing someone’s values is to ask them to rank the 36 values in order of importance. By comparing these values, people develop a sense of which value can be sacrificed to achieve the other, and the individual priority of each value emerges.

Sample Items From Rokeach (1973) Value Survey:

Where do values come from? Research indicates that they are shaped early in life and show stability over the course of a lifetime. Early family experiences are important influences over the dominant values. (Kasser, Koestner, & Lekes, 2002).

Values of a generation also change and evolve in response to the historical context that the generation grows up in. Research comparing the values of different generations resulted in interesting findings. For example, Generation Xers (those born between the mid-1960s and 1980s) are more individualistic and are interested in working toward organizational goals so long as they coincide with their personal goals. This group, compared to the baby boomers (born between the 1940s and 1960s), is also less likely to see work as central to their life and more likely to desire a quick promotion (Smola & Sutton, 2002).

The values a person holds will affect his or her employment. For example, someone who has an orientation toward strong stimulation may pursue extreme sports and select an occupation that involves fast action and high risk, such as fire fighter, police officer, or emergency medical doctor. Someone who has a drive for achievement may more readily act as an entrepreneur. Moreover, whether individuals will be satisfied at a given job may depend on whether the job provides a way to satisfy their dominant values. Therefore, understanding employees at work requires understanding the value orientations of employees.

Personality

Personality encompasses the relatively stable feelings, thoughts, and behavioral patterns a person has. Our personality differentiates us from other people, and understanding someone’s personality gives us clues about how that person is likely to act and feel in a variety of situations. In order to effectively man- age organizational behavior, an understanding of different employees’ personalities is helpful. Having this knowledge is also useful for placing people in jobs and organizations.

If personality is stable, does this mean that it does not change? You probably remember how you have changed and evolved as a result of your own life experiences, attention you received in early childhood, the style of parenting you were exposed to, successes and failures you had in high school, and other life events. In fact, our personality changes over long periods of time. For example, we tend to become more socially dominant, more conscientious (organized and dependable), and more emotionally stable between the ages of 20 and 40, whereas openness to new experiences may begin to decline during this same time (Roberts, Walton, & Viechtbauer, 2006). In other words, even though we treat personality as relatively stable, changes occur. Moreover, even in childhood, our personality shapes who we are and has lasting consequences for us. For example, studies show that part of our career success and job satisfaction later in life can be explained by our childhood personality (Judge & Higgins, 1999; Staw, Bell, & Clausen, 1986).

Is our behavior in organizations dependent on our personality? To some extent, yes, and to some extent, no. While we will discuss the effects of personality for employee behavior, you must remember that the relationships we describe are modest correlations. For example, having a sociable and outgoing personality may encourage people to seek friends and prefer social situations. This does not mean that their personality will immediately affect their work behavior. At work, we have a job to do and a role to per- form. Therefore, our behavior may be more strongly affected by what is expected of us, as opposed to how we want to behave. When people have a lot of freedom at work, their personality will become a stronger influence over their behavior (Barrick & Mount, 1993).

Big Five Personality Traits

How many personality traits are there? How do we even know? In every language, there are many words describing a person’s personality. In fact, in the English language, more than 15,000 words describing personality have been identified. When researchers analyzed the terms describing personality characteristics, they realized that there were many words that were pointing to each dimension of personality. When these words were grouped, five dimensions seemed to emerge that explain a lot of the variation in our personalities (Goldberg, 1990). Keep in mind that these five are not necessarily the only traits out there. There are other, specific traits that represent dimensions not captured by the Big Five. Still, under- standing the main five traits gives us a good start for describing personality. A summary of the Big Five traits is presented below.

Openness is the degree to which a person is curious, original, intellectual, creative, and open to new ideas. People high in openness seem to thrive in situations that require being flexible and learning new things. They are highly motivated to learn new skills, and they do well in training settings (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Lievens et al., 2003). They also have an advantage when they enter into a new organization. Their open-mindedness leads them to seek a lot of information and feedback about how they are doing and to build relationships, which leads to quicker adjustment to the new job (Wanberg & Kam- meyer-Mueller, 2000). When supported, they tend to be creative (Baer & Oldham, 2006). Open people are highly adaptable to change, and teams that experience unforeseen changes in their tasks do well if they are populated with people high in openness (LePine, 2003). Compared to people low in openness, they are also more likely to start their own business (Zhao & Seibert, 2006).

Conscientiousness refers to the degree to which a person is organized, systematic, punctual, achievement oriented, and dependable. Conscientiousness is the one personality trait that uniformly predicts how high a person’s performance will be, across a variety of occupations and jobs (Barrick & Mount, 1991). In fact, conscientiousness is the trait most desired by recruiters and results in the most success in interviews (Dunn et al., 1995; Tay, Ang, & Van Dyne, 2006). This is not a surprise, because in addition to their high performance, conscientious people have higher levels of motivation to perform, lower levels of turnover, lower levels of absenteeism, and higher levels of safety performance at work (Judge & Ilies, 2002; Judge, Martocchio, & Thoresen, 1997; Wallace & Chen, 2006; Zimmerman, 2008). One’s conscientiousness is related to career success and being satisfied with one’s career over time (Judge & Higgins, 1999). Finally, it seems that conscientiousness is a good trait to have for entrepreneurs. Highly conscientious people are more likely to start their own business compared to those who are not conscientious, and their firms have longer survival rates (Certo & Certo, 2005; Zhao & Seibert, 2006).

Extraversion is the degree to which a person is outgoing, talkative, and sociable, and enjoys being in social situations. One of the established findings is that they tend to be effective in jobs involving sales (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Vinchur et al., 1998). Moreover, they tend to be effective as managers and they demonstrate inspirational leadership behaviors (Bauer et al., 2006; Bono & Judge, 2004). Extraverts do well in social situations, and as a result they tend to be effective in job interviews. Part of their success comes from how they prepare for the job interview, as they are likely to use their social network (Cald- well & Burger, 1998; Tay, Ang, & Van Dyne, 2006). Extraverts have an easier time than introverts when adjusting to a new job. They actively seek information and feedback, and build effective relationships, which helps with their adjustment (Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). Interestingly, extraverts are also found to be happier at work, which may be because of the relationships they build with the peo- ple around them and their relative ease in adjusting to a new job (Judge et al., 2002). However, they do not necessarily perform well in all jobs, and jobs depriving them of social interaction may be a poor fit. Moreover, they are not necessarily model employees. For example, they tend to have higher levels of absenteeism at work, potentially because they may miss work to hang out with or attend to the needs of their friends (Judge, Martocchio, & Thoresen, 1997).

People who are high in agreeableness are likeable people who get along with others. Not surprisingly, agreeable people help others at work consistently, and this helping behavior is not dependent on being in a good mood (Ilies, Scott, & Judge, 2006). They are also less likely to retaliate when other people treat them unfairly (Skarlicki, Folger, & Tesluk, 1999). This may reflect their ability to show empathy and give people the benefit of the doubt. Agreeable people may be a valuable addition to their teams and may be effective leaders because they create a fair environment when they are in leadership positions (Mayer et al., 2007). At the other end of the spectrum, people low in agreeableness are less likely to show these positive behaviors. Moreover, people who are not agreeable are shown to quit their jobs unexpectedly, perhaps in response to a conflict they engage with a boss or a peer (Zim- merman, 2008). If agreeable people are so nice, does this mean that we should only look for agreeable people when hiring? Some jobs may actually be a better fit for someone with a low level of agreeable- ness. Think about it: When hiring a lawyer, would you prefer a kind and gentle person, or a pit bull? Also, high agreeableness has a downside: Agreeable people are less likely to engage in constructive and change-oriented communication (LePine & Van Dyne, 2001). Disagreeing with the status quo may create conflict and agreeable people will likely avoid creating such conflict, missing an opportunity for constructive change.

Neuroticism refers to the degree to which a person is anxious, irritable, aggressive, temperamental, and moody. These people have a tendency to have emotional adjustment problems and experience stress and depression on a habitual basis. People very high in neuroticism experience a number of problems at work. For example, they are less likely to be someone people go to for advice and friendship (Klein et al., 2004). In other words, they may experience relationship difficulties. They tend to be habitually unhappy in their jobs and report high intentions to leave, but they do not necessarily actually leave their jobs (Judge, Heller, & Mount, 2002; Zimmerman, 2008). Being high in neuroticism seems to be harmful to one’s career, as they have lower levels of career success (measured with income and occupational status achieved in one’s career). Finally, if they achieve managerial jobs, they tend to create an unfair climate at work (Mayer et al., 2007).

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator

Aside from the Big Five personality traits, perhaps the most well-known and most often used personality assessment is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). Unlike the Big Five, which assesses traits, MBTI measures types. Assessments of the Big Five do not classify people as neurotic or extravert: It is all a matter of degrees. MBTI on the other hand, classifies people as one of 16 types (Carlyn, 1977; Myers, 1962). In MBTI, people are grouped using four dimensions. Based on how a person is classified on these four dimensions, it is possible to talk about 16 unique personality types, such as ESTJ and ISTP.

MBTI was developed in 1943 by a mother–daughter team, Isabel Myers and Katherine Cook Briggs. Its objective at the time was to aid World War II veterans in identifying the occupation that would suit their personalities. Since that time, MBTI has become immensely popular, and according to one esti- mate, around 2.5 million people take the test annually. The survey is criticized because it relies on types as opposed to traits, but organizations who use the survey find it very useful for training and team-build- ing purposes. More than 80 of the Fortune 100 companies used Myers-Briggs tests in some form. One distinguishing characteristic of this test is that it is explicitly designed for learning, not for employee selection purposes. In fact, the Myers & Briggs Foundation has strict guidelines against the use of the test for employee selection. Instead, the test is used to provide mutual understanding within the team and to gain a better understanding of the working styles of team members (Leonard & Straus, 1997; Shuit, 2003).

Summary of MBTI Types

Positive and Negative Affectivity

You may have noticed that behavior is also a function of moods. When people are in a good mood, they may be more cooperative, smile more, and act friendly. When these same people are in a bad mood, they may have a tendency to be picky, irritable, and less tolerant of different opinions. Yet, some people seem to be in a good mood most of the time, and others seem to be in a bad mood most of the time regardless of what is actually going on in their lives. This distinction is manifested by positive and negative affectivity traits. Positive affective people experience positive moods more frequently, whereas negative affective people experience negative moods with greater frequency. Negative affective people focus on the “glass half empty” and experience more anxiety and nervousness (Watson & Clark, 1984). Positive affective people tend to be happier at work (Ilies & Judge, 2003), and their happiness spreads to the rest of the work environment. As may be expected, this personality trait sets the tone in the work atmosphere. When a team comprises mostly negative affective people, there tend to be fewer instances of helping and cooperation. Teams dominated by positive affective people experience lower levels of absenteeism (George, 1989). When people with a lot of power are also high in positive affectivity, the work environment is affected in a positive manner and can lead to greater levels of cooperation and finding mutually agreeable solutions to problems (Anderson & Thompson, 2004).

Toolbox: Help, I work with a negative person!

Employees who have high levels of neuroticism or high levels of negative affectivity may act overly negative at work, criticize others, complain about trivial things, or create an overall negative work environment. Here are some tips for how to work with them effectively.

- Understand that you are unlikely to change someone else’s personality . Personality is relatively stable and criticizing someone’s personality will not bring about change. If the behavior is truly disruptive, focus on behavior, not personality.

- Keep an open mind . Just because a person is constantly negative does not mean that they are not sometimes right. Listen to the feedback they are giving you.

- Set a time limit . If you are dealing with someone who constantly complains about things, you may want to limit these conversations to prevent them from consuming your time at work.

- You may also empower them to act on the negatives they mention . The next time an overly negative individual complains about something, ask that person to think of ways to change the situation and get back to you.

- Ask for specifics . If someone has a negative tone in general, you may want to ask for specific examples for what the problem is.

Sources: Adapted from ideas in Ferguson, J. (2006, October 31). Expert’s view…on managing office moaners. Personnel Today , 29; Karcher, C. (2003, September), Working with difficult people. National Public Accountant , 39–40; Mudore, C. F. (2001, February/March). Working with difficult people. Career World , 29 (5), 16–18; How to manage difficult people. (2000, May). Leadership for the Front Lines , 3–4.

Self-Monitoring

Self-monitoring refers to the extent to which a person is capable of monitoring his or her actions and appearance in social situations. In other words, people who are social monitors are social chameleons who understand what the situation demands and act accordingly, while low social monitors tend to act the way they feel (Snyder, 1974; Snyder, 1987). High social monitors are sensitive to the types of behaviors the social environment expects from them. Their greater ability to modify their behavior according to the demands of the situation and to manage their impressions effectively is a great advantage for them (Turnley & Bolino, 2001). In general, they tend to be more successful in their careers. They are more likely to get cross-company promotions, and even when they stay with one company, they are more likely to advance (Day & Schleicher; Kilduff & Day, 1994). Social monitors also become the “go to” person in their company and they enjoy central positions in their social networks (Mehra, Kilduff, & Brass, 2001). They are rated as higher performers, and emerge as leaders (Day et al., 2002). While they are effective in influencing other people and get things done by managing their impressions, this personality trait has some challenges that need to be addressed. First, when evaluating the performance of other employees, they tend to be less accurate. It seems that while trying to manage their impressions, they may avoid giving accurate feedback to their subordinates to avoid confrontations (Jawahar, 2001). This tendency may create problems for them if they are managers. Second, high social monitors tend to experience higher levels of stress, probably caused by behaving in ways that conflict with their true feelings. In situations that demand positive emotions, they may act happy although they are not feeling happy, which puts an emotional burden on them. Finally, high social monitors tend to be less committed to their companies. They may see their jobs as a stepping-stone for greater things, which may prevent them from forming strong attachments and loyalty to their current employer (Day et al., 2002).

Proactive Personality

Proactive personality refers to a person’s inclination to fix what is perceived as wrong, change the status quo, and use initiative to solve problems. Instead of waiting to be told what to do, proactive people take action to initiate meaningful change and remove the obstacles they face along the way. In general, having a proactive personality has a number of advantages for these people. For example, they tend to be more successful in their job searches (Brown et al., 2006). They are also more successful over the course of their careers, because they use initiative and acquire greater understanding of the politics within the organization (Seibert, 1999; Seibert, Kraimer, & Crant, 2001). Proactive people are valuable assets to their companies because they may have higher levels of performance (Crant, 1995). They adjust to their new jobs quickly because they understand the political environment better and often make friends more quickly (Kammeyer-Mueller & Wanberg, 2003; Thompson, 2005). Proactive people are eager to learn and engage in many developmental activities to improve their skills (Major, Turner, & Fletcher, 2006). Despite all their potential, under some circumstances a proactive personality may be a liability for an individual or an organization. Imagine a person who is proactive but is perceived as being too pushy, trying to change things other people are not willing to let go, or using their initiative to make decisions that do not serve a company’s best interests. Research shows that the success of proactive people depends on their understanding of a company’s core values, their ability and skills to perform their jobs, and their ability to assess situational demands correctly (Chan, 2006; Erdogan & Bauer, 2005).

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is the degree to which a person has overall positive feelings about his or herself. People with high self-esteem view themselves in a positive light, are confident, and respect themselves. On the other hand, people with low self-esteem experience high levels of self-doubt and question their self-worth. High self-esteem is related to higher levels of satisfaction with one’s job and higher levels of performance on the job (Judge & Bono, 2001). People with low self-esteem are attracted to situations in which they will be relatively invisible, such as large companies (Turban & Keon, 1993). Managing employees with low self-esteem may be challenging at times, because negative feedback given with the intention to improve performance may be viewed as a judgment on their worth as an employee. Therefore, effectively managing employees with relatively low self-esteem requires tact and providing lots of positive feedback when discussing performance incidents.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is a belief that one can perform a specific task successfully. Research shows that the belief that we can do something is a good predictor of whether we can actually do it. Self-efficacy is different from other personality traits in that it is job specific. You may have high self-efficacy in being successful academically, but low self-efficacy in relation to your ability to fix your car. At the same time, people have a certain level of generalized self-efficacy and they have the belief that whatever task or hobby they tackle, they are likely to be successful in it.

Research shows that self-efficacy at work is related to job performance (Bauer et al., 2007; Judge et al., 2007; Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). This relationship is probably a result of people with high self-efficacy setting higher goals for themselves and being more committed to these goals, whereas people with low self-efficacy tend to procrastinate (Phillips & Gully, 1997; Steel, 2007; Wofford, Goodwin, & Premack, 1992). Academic self-efficacy is a good predictor of your GPA, whether you persist in your studies, or drop out of college (Robbins et al., 2004).

Is there a way of increasing employees’ self-efficacy? Hiring people who are capable of performing their tasks and training people to increase their self-efficacy may be effective. Some people may also respond well to verbal encouragement. By showing that you believe they can be successful and effectively playing the role of a cheerleader, you may be able to increase self-efficacy. Giving people opportunities to test their skills so that they can see what they are capable of doing (or empowering them) is also a good way of increasing self-efficacy (Ahearne, Mathieu, & Rapp, 2005).

OB Toolbox: Ways to Build Your Self-Confidence

Having high self-efficacy and self-esteem are boons to your career. People who have an overall positive view of themselves and those who have positive attitudes toward their abilities project an aura of confidence. How do you achieve higher self-confidence?

- Take a self-inventory . What are the areas in which you lack confidence? Then consciously tackle these areas. Take part in training programs; seek opportunities to practice these skills. Confront your fears head-on.

- Set manageable goals . Success in challenging goals will breed self-confidence, but do not make your goals impossible to reach. If a task seems daunting, break it apart and set mini goals.

- Find a mentor . A mentor can point out areas in need of improvement, provide accurate feedback, and point to ways of improving yourself.

- Don’t judge yourself by your failures . Everyone fails, and the most successful people have more failures in life. Instead of assessing your self-worth by your failures, learn from mistakes and move on.

- Until you can feel confident, be sure to act confident . Acting confident will influence how others treat you, which will boost your confidence level. Pay attention to how you talk and behave, and act like someone who has high confidence.

- Know when to ignore negative advice . If you receive negative feedback from someone who is usually negative, try to ignore it. Surrounding yourself with naysayers is not good for your self- esteem. This does not mean that you should ignore all negative feedback, but be sure to look at a person’s overall attitude before making serious judgments based on that feedback.

Sources: Adapted from information in Beagrie, S. (2006, September 26). How to…build up self confidence. Personnel Today , p. 31; Beste, F. J., III. (2007, November–December). Are you an entrepreneur? In Business , 29 (6), 22; Goldsmith, B. (2006, October). Building self confidence. PA Times, Education Supplement , p. 30; Kennett, M. (2006, October). The scale of confidence. Management Today , p. 40–45; Parachin, V. M. (March 2003, October). Developing dynamic self-confidence. Supervision , 64 (3), 13–15.

Locus of Control

Locus of control deals with the degree to which people feel accountable for their own behaviors. Individuals with high internal locus of control believe that they control their own destiny and what happens to them is their own doing, while those with high external locus of control feel that things happen to them because of other people, luck, or a powerful being. Internals feel greater control over their own lives and therefore they act in ways that will increase their chances of success. For example, they take the initiative to start mentor-protégé relationships. They are more involved with their jobs. They demonstrate higher levels of motivation and have more positive experiences at work (Ng, Soresen, & Eby, 2006; Reitz & Jewell, 1979; Turban & Dougherty, 1994). Interestingly, internal locus is also related to one’s subjective well-being and happiness in life, while being high in external locus is related to a higher rate of depression (Benassi, Sweeney, & Dufour, 1988; DeNeve & Cooper, 1998). The connection between internal locus of control and health is interesting, but perhaps not surprising. In fact, one study showed that having internal locus of control at the age of 10 was related to a number of health outcomes, such as lower obesity and lower blood pressure later in life (Gale, Batty, & Deary, 2008). It is possible that internals take more responsibility for their health and adopt healthier habits, while externals may see less of a connection between how they live and their health. Internals thrive in contexts in which they have the ability to influence their own behavior. Successful entrepreneurs tend to have high levels of internal locus of control (Certo & Certo, 2005).

Personality Testing in Employee Selection

Personality is a potentially important predictor of work behavior. Matching people to jobs matters, because when people do not fit with their jobs or the company, they are more likely to leave, costing companies as much as a person’s annual salary to replace them. In job interviews, companies try to assess a candidate’s personality and the potential for a good match, but interviews are only as good as the people conducting them. In fact, interviewers are not particularly good at detecting the best trait that predicts performance: conscientiousness (Barrick, Patton, & Haugland, 2000). One method some companies use to improve this match and detect the people who are potentially good job candidates is personality testing. Companies such as Kronos and Hogan Assessment Systems conduct preemployment personality tests. Companies using them believe that these tests improve the effectiveness of their selection and reduce turnover. For example, Overnight Transportation in Atlanta found that using such tests reduced their on-the-job delinquency by 50%–100% (Emmet, 2004; Gale, 2002).

Yet, are these methods good ways of selecting employees? Experts have not yet reached an agreement on this subject and the topic is highly controversial. Some experts believe, based on data, that personality tests predict performance and other important criteria such as job satisfaction. However, we must under- stand that how a personality test is used influences its validity. Imagine filling out a personality test in class. You may be more likely to fill it out as honestly as you can. Then, if your instructor correlates your personality scores with your class performance, we could say that the correlation is meaningful. In employee selection, one complicating factor is that people filling out the survey do not have a strong incentive to be honest. In fact, they have a greater incentive to guess what the job requires and answer the questions to match what they think the company is looking for. As a result, the rankings of the candidates who take the test may be affected by their ability to fake. Some experts believe that this is a serious problem (Morgeson et al., 2007; Morgeson et al., 2007). Others point out that even with faking , the tests remain valid—the scores are still related to job performance (Barrick & Mount, 1996; Ones et al., 2007; Ones, Viswesvaran, & Reiss, 1996; Tell & Christiansen, 2007). It is even possible that the ability to fake is related to a personality trait that increases success at work, such as social monitoring. This issue raises potential questions regarding whether personality tests are the most effective way of measuring candidate personality.

Scores are not only distorted because of some candidates faking better than others. Do we even know our own personality? Are we the best person to ask this question? How supervisors, coworkers, and customers see our personality matters more than how we see ourselves. Therefore, using self-report measures of performance may not be the best way of measuring someone’s personality (Mount, Barrick, & Strauss, 1994). We all have areas of limitation. We may also give “aspirational” answers. If you are asked if you are honest, you may think, “Yes, I always have the intention to be honest.” This response says nothing about your actual level of honesty.

There is another problem with using these tests: How good a predictor of performance is personality anyway? Based on research, not a particularly strong one. According to one estimate, personality only explains about 10%–15% of variation in job performance. Our performance at work depends on so many factors, and personality does not seem to be the key factor for performance. In fact, cognitive ability (your overall mental intelligence) is a much more powerful influence on job performance, and instead of personality tests, cognitive ability tests may do a better job of predicting who will be good performers. Personality is a better predictor of job satisfaction and other attitudes, but screening people out on the assumption that they may be unhappy at work is a challenging argument to make in the context of employee selection.

In any case, if you decide to use these tests for selection, you need to be aware of their limitations. Relying only on personality tests for selection of an employee is a bad idea, but if they are used together with other tests such as tests of cognitive abilities, better decisions may be made. The company should ensure that the test fits the job and actually predicts performance. This process is called validating the test. Before giving the test to applicants, the company could give it to existing employees to find out the traits that are most important for success in the particular company and job. Then, in the selection con- text, the company can pay particular attention to those traits. The company should also make sure that the test does not discriminate against people on the basis of sex, race, age, disabilities, and other legally protected characteristics. Rent-A-Center experienced legal difficulties when the test they used was found to be a violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The test they used for selection, the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, was developed to diagnose severe mental illnesses and included items such as “I see things or people around me others do not see.” In effect, the test served the purpose of a clinical evaluation and was discriminating against people with mental illnesses, which is a protected category under ADA (Heller, 2005).

Values and personality traits are two dimensions on which people differ. Values are stable life goals. When seeking jobs, employees are more likely to accept a job that provides opportunities for value attainment, and they are more likely to remain in situations that satisfy their values. Personality comprises the stable feelings, thoughts, and behavioral patterns people have. The Big Five personality traits (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism) are important traits that seem to be stable and can be generalized to other cultures. Other important traits for work behavior include self-efficacy, self-esteem, social monitoring, proactive personality, positive and negative affectivity, and locus of control. It is important to remember that a person’s behavior depends on the match between the person and the situation. While personality is a strong influence on job attitudes, its relation to job performance is weaker. Some companies use personality testing to screen out candidates. This method has certain limitations, and companies using personality tests are advised to validate their tests and use them as a supplement to other techniques that have greater validity.

5.3 Perception

Our behavior is not only a function of our personality, values, and preferences, but also of the situation. We interpret our environment, formulate responses, and act accordingly. Perception may be defined as the process with which individuals detect and interpret environmental stimuli. What makes human perception so interesting is that we do not solely respond to the stimuli in our environment. We go beyond the information that is present in our environment, pay selective attention to some aspects of the environment, and ignore other elements that may be immediately apparent to other people. Our perception of the environment is not entirely rational. For example, have you ever noticed that while glancing at a newspaper or a news Web site, information that is interesting or important to you jumps out of the page and catches your attention? If you are a sports fan, while scrolling down the pages you may immediately see a news item describing the latest success of your team. If you are the parent of a picky eater, an advice column on toddler feeding may be the first thing you see when looking at the page. So what we see in the environment is a function of what we value, our needs, our fears, and our emotions (Higgins & Bargh, 1987; Keltner, Ellsworth, & Edwards, 1993). In fact, what we see in the environment may be objectively, flat-out wrong because of our personality, values, or emotions. For example, one experiment showed that when people who were afraid of spiders were shown spiders, they inaccurately thought that the spider was moving toward them (Riskin, Moore, & Bowley, 1995). In this section, we will describe some common tendencies we engage in when perceiving objects or other people, and the consequences of such perceptions. Our coverage of biases and tendencies in perception is not exhaustive—there are many other biases and tendencies on our social perception.

Visual Perception

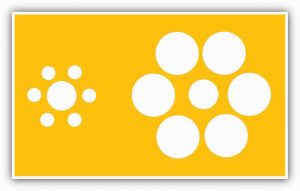

Our visual perception definitely goes beyond the physical information available to us. First of all, we extrapolate from the information available to us. Take a look at the following figure. The white triangle you see in the middle is not really there, but we extrapolate from the information available to us and see it there (Kellman & Shipley, 1991).

Our visual perception goes beyond the information physically available. In this figure, we see the white triangle in the middle even though it is not really there.

Which of the circles in the middle is bigger? At first glance, the one on the left may appear bigger, but they are in fact the same size. We compare the middle circle on the left to its surrounding circles, whereas the middle circle on the right is compared to the bigger circles surrounding it.

Our visual perception is often biased because we do not perceive objects in isolation. The contrast between our focus of attention and the remainder of the environment may make an object appear bigger or smaller. This principle is illustrated in the figure with circles. Which of the middle circles is bigger? To most people, the one on the left appears bigger, but this is because it is surrounded by smaller circles. The contrast between the focal object and the objects surrounding it may make an object bigger or smaller to our eye.

How do these tendencies influence behavior in organizations? You may have realized that the fact that our visual perception is faulty may make witness testimony faulty and biased. How do we know whether the employee you judge to be hardworking, fast, and neat is really like that? Is it really true, or are we comparing this person to other people in the immediate environment? Or let’s say that you do not like one of your peers and you think that this person is constantly surfing the Web during work hours. Are you sure? Have you really seen this person surf unrelated Web sites, or is it possible that the person was surfing the Web for work-related purposes? Our biased visual perception may lead to the wrong inferences about the people around us.

Self-Perception

Human beings are prone to errors and biases when perceiving themselves. Moreover, the type of bias people have depends on their personality. Many people suffer from self-enhancement bias . This is the tendency to overestimate our performance and capabilities and see ourselves in a more positive light than others see us. People who have a narcissistic personality are particularly subject to this bias, but many others are still prone to overestimating their abilities (John & Robins, 1994). At the same time, other people have the opposing extreme, which may be labeled as self-effacement bias . This is the tendency for people to underestimate their performance, undervalue capabilities, and see events in a way that puts them in a more negative light. We may expect that people with low self-esteem may be particularly prone to making this error. These tendencies have real consequences for behavior in organizations. For example, people who suffer from extreme levels of self-enhancement tendencies may not understand why they are not getting promoted or rewarded, while those who have a tendency to self-efface may project low confidence and take more blame for their failures than necessary.

When perceiving themselves, human beings are also subject to the false consensus error . Simply put, we overestimate how similar we are to other people (Fields & Schuman, 1976; Ross, Greene, & House, 1977). We assume that whatever quirks we have are shared by a larger number of people than in reality. People who take office supplies home, tell white lies to their boss or colleagues, or take credit for other people’s work to get ahead may genuinely feel that these behaviors are more common than they really are. The problem for behavior in organizations is that, when people believe that a behavior is common and normal, they may repeat the behavior more freely. Under some circumstances this may lead to a high level of unethical or even illegal behaviors.

Social Perception

How we perceive other people in our environment is also shaped by our values, emotions, feelings, and personality. Moreover, how we perceive others will shape our behavior, which in turn will shape the behavior of the person we are interacting with.

One of the factors biasing our perception is stereotypes . Stereotypes are generalizations based on group characteristics. Stereotypes may be positive, negative, or neutral. Human beings have a natural tendency to categorize the information around them to make sense of their environment. What makes stereotypes potentially discriminatory and a perceptual bias is the tendency to generalize from a group to a particular individual. If the belief that one group has a greater skill leads to choosing a person over an equally (or potentially more) qualified candidate from another area for a position, the decision will be biased, potentially illegal, and unfair.

Stereotypes often create a situation called a self-fulfilling prophecy . This cycle occurs when people automatically behave as if an established stereotype is accurate, which leads to reactive behavior from the other party that confirms the stereotype (Snyder, Tanke, & Berscheid, 1977).

Stereotypes persist because of a process called selective perception. Selective perception simply means that we pay selective attention to parts of the environment while ignoring other parts. When we observe our environment, we see what we want to see and ignore information that may seem out of place. Here is an interesting example of how selective perception leads our perception to be shaped by the context: As part of a social experiment, in 2007 the Washington Post newspaper arranged Joshua Bell, the inter- nationally acclaimed violin virtuoso, to perform in a corner of the Metro station in Washington DC. The violin he was playing was worth $3.5 million, and tickets for Bell’s concerts usually cost around $100. During the rush hour in which he played for 45 minutes, only one person recognized him, only a few realized that they were hearing extraordinary music, and he made only $32 in tips. When you see some- one playing at the metro station, would you expect them to be extraordinary? (Weingarten, 2007)

Our background, expectations, and beliefs will shape which events we notice and which events we ignore. For example, the functional background of executives affects the changes they perceive in their environment (Waller, Huber, & Glick, 1995). Executives with a background in sales and marketing see the changes in the demand for their product, while executives with a background in information technology may more readily perceive the changes in the technology the company is using. Selective perception may perpetuate stereotypes, because we are less likely to notice events that go against our beliefs. A per- son who believes that men drive better than women may be more likely to notice women driving poorly than men driving poorly. As a result, a stereotype is maintained because information to the contrary may not reach our brain.

Let’s say we noticed information that goes against our beliefs. What then? Unfortunately, this is no guarantee that we will modify our beliefs and prejudices. First, when we see examples that go against our stereotypes, we tend to come up with subcategories. For example, when people who believe that women are more cooperative see a female who is assertive, they may classify this person as a “career woman.” Therefore, the example to the contrary does not violate the stereotype, and instead is explained as an exception to the rule (Higgins & Bargh, 1987). Second, we may simply discount the information. In one study, people who were either in favor of or opposed to the death penalty were shown two studies, one showing benefits from the death penalty and the other discounting any benefits. People rejected the study that went against their belief as methodologically inferior and actually reinforced the belief in their original position even more (Lord, Ross, & Lepper, 1979). In other words, trying to debunk people’s beliefs or previously established opinions with data may not necessarily help.

One other perceptual tendency that may affect work behavior is that of first impressions . The first impressions we form about people tend to have a lasting impact. In fact, first impressions, once formed, are surprisingly resilient to contrary information. Even if people are told that the first impressions were caused by inaccurate information, people hold onto them to a certain degree. The reason is that, once we form first impressions, they become independent of the evidence that created them (Ross, Lepper, & Hubbard, 1975). Any information we receive to the contrary does not serve the purpose of altering the original impression. Imagine the first day you met your colleague Anne. She treated you in a rude manner and when you asked for her help, she brushed you off. You may form the belief that she is a rude and unhelpful person. Later, you may hear that her mother is very sick and she is very stressed. In reality she may have been unusually stressed on the day you met her. If you had met her on a different day, you could have thought that she is a really nice person who is unusually stressed these days. But chances are your impression that she is rude and unhelpful will not change even when you hear about her mother. Instead, this new piece of information will be added to the first one: She is rude, unhelpful, and her mother is sick. Being aware of this tendency and consciously opening your mind to new information may protect you against some of the downsides of this bias. Also, it would be to your advantage to pay careful attention to the first impressions you create, particularly during job interviews.

Toolbox: How Can I Make a Great First Impression in the Job Interview?

A job interview is your first step to getting the job of your dreams. It is also a social interaction in which your actions during the first 5 minutes will determine the impression you make. Here are some tips to help you create a positive first impression.

- Your first opportunity to make a great impression starts even before the interview, the moment you send your résumé . Be sure that you send your résumé to the correct people, and spell the name of the contact person correctly! Make sure that your résumé looks professional and is free from typos and grammar problems. Have someone else read it before you hit the send button or mail it.

- Be prepared for the interview . Many interviews have some standard questions such as “tell me about yourself” or “why do you want to work here?” Be ready to answer these questions. Prepare answers highlighting your skills and accomplishments, and practice your message. Better yet, practice an interview with a friend. Practicing your answers will prevent you from regretting your answers or finding a better answer after the interview is over!

- Research the company . If you know a lot about the company and the job in question, you will come out as someone who is really interested in the job. If you ask basic questions such as “what does this company do?” you will not be taken as a serious candidate. Visit the company’s Web site as well as others, and learn as much about the company and the job as you can. Your dress is a big part of the impression you make. Dress properly for the job and company in question. In many jobs, wearing professional clothes, such as a suit, is expected. In some information technology jobs, it may be more proper to wear clean and neat business casual clothes (such as khakis and a pressed shirt) as opposed to dressing formally. Do some investigation about what is suitable. Whatever the norm is, make sure that your clothes fit well and are clean and neat.

- Be on time to the interview . Being late will show that you either don’t care about the interview or you are not very reliable. While waiting for the interview, don’t forget that your interview has already started. As soon as you enter the company’s parking lot, every person you see on the way or talk to may be a potential influence over the decision maker. Act professionally and treat everyone nicely.

- During the interview, be polite . Use correct grammar, show eagerness and enthusiasm, and watch your body language. From your handshake to your posture, your body is communicating whether you are the right person for the job!

Sources: Adapted from ideas in Bruce, C. (2007, October). Business Etiquette 101: Making a good first impression. Black Collegian , 38(1), 78–80; Evenson, R. (2007, May). Making a great first impression. Techniques , 14–17; Mather, J., & Watson, M. (2008, May 23). Perfect candidate. The Times Educational Supplement , 4789 , 24–26; Messmer, M. (2007, July). 10 minutes to impress. Journal of Accountancy , 204 (1), 13; Reece, T. (2006, November–December). How to wow! Career World , 35 , 16–18.

Attributions

Your colleague Peter failed to meet the deadline. What do you do? Do you help him finish up his work? Do you give him the benefit of the doubt and place the blame on the difficulty of the project? Or do you think that he is irresponsible? Our behavior is a function of our perceptions. More specifically, when we observe others behave in a certain way, we ask ourselves a fundamental question: Why? Why did he fail to meet the deadline? Why did Mary get the promotion? Why did Mark help you when you needed help? The answer we give is the key to understanding our subsequent behavior. If you believe that Mark helped you because he is a nice person, your action will be different from your response if you think that Mark helped you because your boss pressured him to.

An attribution is the causal explanation we give for an observed behavior. If you believe that a behavior is due to the internal characteristics of an actor, you are making an internal attribution . For example, let’s say your classmate Erin complained a lot when completing a finance assignment. If you think that she complained because she is a negative person, you are making an internal attribution. An external attribution is explaining someone’s behavior by referring to the situation. If you believe that Erin complained because finance homework was difficult, you are making an external attribution.

When do we make internal or external attributions? Research shows that three factors are the key to understanding what kind of attributions we make.

- Consensus : Do other people behave the same way?

- Distinctiveness : Does this person behave the same way across different situations?

- Consistency : Does this person behave this way in different occasions in the same situation?

Let’s assume that in addition to Erin, other people in the same class also complained (high consensus). Erin does not usually complain in other classes (high distinctiveness). Erin usually does not complain in finance class (low consistency). In this situation, you are likely to make an external attribution, such as thinking that finance homework is difficult. On the other hand, let’s assume that Erin is the only person complaining (low consensus). Erin complains in a variety of situations (low distinctiveness), and every time she is in finance, she complains (high consistency). In this situation, you are likely to make an internal attribution such as thinking that Erin is a negative person (Kelley, 1967; Kelley, 1973).

Interestingly though, our attributions do not always depend on the consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency we observe in a given situation. In other words, when making attributions, we do not always look at the situation objectively. For example, our overall relationship is a factor. When a manager likes a subordinate, the attributions made would be more favorable (successes are attributed to internal causes, while failures are attributed to external causes) (Heneman, Greenberger, & Anonyou, 1989). Moreover, when interpreting our own behavior, we suffer from self-serving bias . This is the tendency to attribute our failures to the situation while attributing our successes to internal causes (Malle, 2006).

Consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency determine the type of attribution we make in a given situation.

How we react to other people’s behavior would depend on the type of attributions we make. When faced with poor performance, such as missing a deadline, we are more likely to punish the person if an internal attribution is made (such as “the person being unreliable”). In the same situation, if we make an external attribution (such as “the timeline was unreasonable”), instead of punishing the person we might extend the deadline or assign more help to the person. If we feel that someone’s failure is due to external causes, we may feel empathy toward the person and even offer help (LePine & Van Dyne, 2001). On the other hand, if someone succeeds and we make an internal attribution (he worked hard), we are more likely to reward the person, whereas an external attribution (the project was easy) is less likely to yield rewards for the person in question. Therefore, understanding attributions is important to predicting subsequent behavior.

Perception is how we make sense of our environment in response to environmental stimuli. While perceiving our surroundings, we go beyond the objective information available to us, and our perception is affected by our values, needs, and emotions. There are many biases that affect human perception of objects, self, and others. When perceiving the physical environment, we fill in gaps and extrapolate from the available information. We also contrast physical objects to their surroundings and may perceive something as bigger, smaller, slower, or faster than it really is. In self-perception, we may commit the self-enhancement or self-effacement bias, depending on our personality. We also overestimate how much we are like other people. When perceiving others, stereotypes infect our behavior. Stereotypes may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. Stereotypes are perpetuated because of our tendency to pay selective attention to aspects of the environment and ignore information inconsistent with our beliefs. When perceiving others, the attributions we make will determine how we respond to the situation. Understanding the perception process gives us clues to understand human behavior.

5.4 The Role of Ethics and National Culture

Individual differences and ethics.

Our values and personality influence how ethical we behave. Situational factors, rewards, and punishments following unethical choices as well as a company’s culture are extremely important, but the role of personality and personal values should not be ignored. Research reveals that people who have an eco- nomic value orientation, that is, those who value acquiring money and wealth, tend to make more unethical choices. In terms of personality, employees with external locus of control were found to make more unethical choices (Hegarty & Sims, 1978; Hegarty & Sims, 1979; Trevino & Youngblood, 1990).

Our perceptual processes are clear influences on whether or not we behave ethically and how we respond to other people’s unethical behaviors. It seems that self-enhancement bias operates for our ethical decisions as well: We tend to overestimate how ethical we are in general. Our self-ratings of ethics tend to be higher than how other people rate us. This belief can create a glaring problem: If we think that we are more ethical than we are, we will have little motivation to improve. Therefore, understanding how other people perceive our actions is important to getting a better understanding of ourselves.

How we respond to unethical behavior of others will, to a large extent, depend on the attributions we make. If we attribute responsibility to the person in question, we are more likely to punish that person. In a study on sexual harassment that occurred after a workplace romance turned sour, results showed that if we attribute responsibility to the victim, we are less likely to punish the harasser (Pierce et al., 2004). Therefore, how we make attributions in a given situation will determine how we respond to others’ actions, including their unethical behaviors.

Individual Differences Around the Globe

Values that people care about vary around the world. In fact, when we refer to a country’s culture, we are referring to values that distinguish one nation from others. In other words, there is systematic variance in individuals’ personality and work values around the world, and this variance explains people’s behavior, attitudes, preferences, and the transferability of management practices to other cultures.

When we refer to a country’s values, this does not mean that everyone in a given country shares the same values. People differ within and across nations. There will always be people who care more about money and others who care more about relationships within each culture. Yet there are also national differences in the percentage of people holding each value. A researcher from Holland, Geert Hofstede, conducted a landmark study covering over 60 countries and found that countries differ in four dimensions: the extent to which they put individuals or groups first (individualism), whether the society subscribes to equality or hierarchy among people (power distance), the degree to which the society fears change (uncertainty avoidance), and the extent to which the culture emphasizes acquiring money and being successful (masculinity) (Hofstede, 2001). Knowing about the values held in a society will tell us what type of a work- place would satisfy and motivate employees.

Are personality traits universal? Researchers found that personality traits identified in Western cultures translate well to other cultures. For example, the five-factor model of personality is universal in that it explains how people differ from each other in over 79 countries. At the same time, there is variation among cultures in the dominant personality traits. In some countries, extraverts seem to be the majority, and in some countries the dominant trait is low emotional stability. There are many factors explaining why some personality traits are dominant in some cultures. For example, the presence of democratic values is related to extraversion. Because democracy usually protects freedom of speech, people may feel more comfortable socializing with strangers as well as with friends, partly explaining the larger number of extraverts in democratic nations. Research also shows that in regions of the world that historically suffered from infectious diseases, extraversion and openness to experience was less dominant. Infectious diseases led people to limit social contact with strangers, explaining higher levels of introversion. Plus, to cope with infectious diseases, people developed strict habits for hygiene and the amount of spice to use in food, and deviating from these standards was bad for survival. This explains the lower levels of openness to experience in regions that experienced infectious diseases (McCrae & Costa, 1997; McCrae et al., 2005; Schaller & Murray, 2008).

Is basic human perception universal? It seems that there is variation around the globe in how we perceive other people as well as ourselves. (Masuda et al., 2008).

There seems to be some variation in the perceptual biases we commit as well. For example, human beings have a tendency to self-enhance. We see ourselves in a more positive light than others do. Yet, the traits in which we self-enhance are culturally dependent (Sedikides, Gaertner, & Toguchi, 2003; Sedikides, Gaertner, & Vevea, 2005). Given the variation in individual differences around the globe, being sensitive to these differences will increase our managerial effectiveness when managing a diverse group of people.

Personality Around the Globe

Which nations have the highest average self-esteem? Researchers asked this question by surveying almost 17,000 individuals across 53 nations, in 28 languages.

Based on this survey, these are the top 10 nations in terms of self-reported self-esteem.

- United States

The 10 nations with the lowest self-reported self-esteem are the following:

- South Korea

- Switzerland

- Czech Republic

Source: Adapted from information in Denissen, J. J. A., Penke, L., & Schmitt, D. P. (2008, July). Self-esteem reactions to social interactions: Evidence for sociometer mechanisms across days, people, and nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 95 , 181–196; Hitti, M. (2005). Who’s no. 1 in self-esteem? Serbia is tops, Japan ranks lowest, U.S. is no. 6 in global survey. WebMD. Retrieved November 14, 2008, from http://www.webmd.com/skin-beauty/news/20050927/whos-number-1-in-self-esteem ; Schmitt, D. P., & Allik, J. (2005). The simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale in 53 nationals: Culture-specific features of global self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 89 , 623–642.

There is a connection between how ethically we behave and our individual values, personality, and perception. Possessing values emphasizing economic well-being predicts unethical behavior. Having an external locus of control is also related to unethical decision making. We are also likely to overestimate how ethical we are, which can be a barrier against behaving ethically. Culture seems to be an influence over our values, personality traits, perceptions, attitudes, and work behaviors. Therefore, understanding individual differences requires paying careful attention to the cultural context.

5.5 Conclusion

In conclusion, in this chapter we have reviewed major individual differences that affect employee attitudes and behaviors. Our values and personality explain our preferences and the situations we feel comfortable with. Personality may influence our behavior, but the importance of the context in which behavior occurs should not be neglected. Many organizations use personality tests in employee selection, but the use of such tests is controversial because of problems such as faking and low predictive value of personality for job performance. Perception is how we interpret our environment. It is a major influence over our behavior, but many systematic biases color our perception and lead to misunderstandings.

Adapted from: Organizational Behavior

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA LIBRARIES PUBLISHING EDITION, 2017. THIS EDITION ADAPTED FROM A WORK ORIGINALLY PRODUCED IN 2010 BY A PUBLISHER WHO HAS REQUESTED THAT IT NOT RECEIVE ATTRIBUTION.

MINNEAPOLIS, MN

Using Teams to Facilitate Organizational Development Copyright © 2021 by Dr. Kim Godwin; Dr. Mike Boyle; and Meredith Anne Higgs is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Employee Success Platform Improve engagement, inspire performance, and build a magnetic culture.

- Engagement Survey

- Lifecycle Surveys

- Pulse Surveys

- Action Planning

- Talent Reviews

- Performance Reviews

- Succession Planning

- Recognition

- Expert-Informed AI

- Seamless Integrations

- Award-Winning Service

- Robust Analytics

- Scale Employee Success with AI

- Drive Employee Retention

- Identify and Develop Top Talent

- Build High Performing Teams

- Increase Strategic Alignment

- Manage Remote Teams

- Improve Employee Engagement

- Customer Success Stories

- Customer Experience

- Customer Advisory Board

- Not Another Employee Engagement Trends Report

- Everyone Owns Employee Success

- Employee Success ROI Calculator

- Employee Retention Quiz

- Ebooks & Templates

- Leadership Team

- Partnerships

- Best Places to Work

- Request a Demo

Managing Individual Differences in the Workplace

Dan Harris, Ph.D.

July 30, 2018 | 3 minute read

And organizational identities like the industry they work in, the size of their organization, and their own tenure, department, or position level.

These barely scratch the surface of how many individual differences a person may have or express at any given time, and that’s not even taking into account things like preferences, biases, and opinions.

With as many factors as the above lists suggest, it boggles my mind when “one size fits all” engagement strategies are discussed or, worse still, considered as legitimate courses of action within organizations. Different employees need different things to be engaged, and painting people with large brush strokes does not create organizational or team environments that maximize engagement. Instead, organizations must prioritize accepting and managing individual differences.

Using data from Quantum Workplace’s annual Employee Engagement Trends Report , I want to present a few examples of individual differences between employee groups. For each demographic, a breakout of 2-5 drivers of engagement will be shown.

The above graph shows that professional growth and career development opportunities becomes a weaker driver of engagement as employees become more tenured. Conversely, believing leaders value people as their most important resource generally becomes a stronger driver of engagement as employees become more tenured.

This suggests that less-tenured employees may feel more engaged when growth opportunities are clearly visible to them, whereas more-tenured employees may feel more engaged when they believe leadership values them .

This isn’t to say that more-tenured employees don’t value professional and career developmental, or that less-tenured employees don’t appreciate a leader's recognition. Rather, these results indicate that individual differences determine what actions will engage employees.

For another analysis of tenure, see research I conducted exploring the tenure curve .

When examining employees by pay type, four out of the five top drivers of engagement are similar. However, the main difference is arguably a large one: being recognized is a stronger driver of engagement for hourly employees than salaried . This indicates that even an individual difference like pay type is important to accept and manage.

The above graph suggests that seeing professional growth and career development opportunities becomes a weaker driver of engagement as employees age.

This, when coupled with the results from tenure, makes intuitive sense; as employees age and become more tenured and experienced, they get closer to their natural career ceiling — a senior leadership position, retirement, being satisfied with what they’ve achieved, etc.

Conversely, believing the organization will be successful in the future only strengthens as a driver of engagement as employees age. Older employees having a higher probability of being more tenured, suggesting that they may also feel more invested in the success of the organization , or that organizational success goes hand-in-hand with how strongly connected they feel to the organization.

Education Level

In this final example, although there isn’t a perfectly clean upward or downward line, we can see that perceived leadership integrity is a stronger driver of engagement for employees with less education (high school diploma or less), and is a weaker driver for employees with mid-level education (Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees).

Likewise, finding one’s job interesting and challenging is a weaker driver of engagement for all education levels except those with Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees.

One takeaway from this graph is that employees without high school diplomas likely feel more engaged when they can trust and respect their leaders , whereas employees with Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees likely feel more engaged when they have jobs that are interesting and challenging .

There may be a certain level of irony in this post; in the beginning I indicated that employees shouldn’t be generalized by large groupings, yet I used relatively large groupings as examples.

My intent was not to offer highly individualized examples, but instead to showcase high-level differences that can guide managers and organizations toward greater individualization .

It’s not that a team member is just a female, or just has 1-2 years tenure, or is just a salaried employee, all in isolation of one another. Rather, she’s a female employee who has 1-2 years tenure and is salaried, among the dozens and dozens more identities, opinions, and preferences that are of varying relevance to her work.