Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Chapter III METHODOLOGY Research Locale

Related Papers

Amanda Hunn

Petra Boynton

Journal of Chemical Education

Diane M Bunce

André Pereira

Satyajit Behera

Measurement and Data Collection. Primary data, Secondary data, Design of questionnaire ; Sampling fundamentals and sample designs. Measurement and Scaling Techniques, Data Processing

Roberto Jr. P Tacbobo

International Journal of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods

Reuben Bihu

Questionnaire surveys dominate the methodological designs in educational and social studies, particularly in developing countries. It is conceived practically easy to adopt study protocols under the design, and off course most researchers would prefer using questionnaire survey studies designed in most simple ways. Such studies provide the most economical way of gathering information from representations giving data that apply to general populations. As such, the desire for cost management and redeeming time have caused many researchers to adapt, adopt and apply the designs, even where it doesn’t qualify for the study contexts. Consequently, they are confronted by managing consistent errors and mismatching study protocols and methodologies. However, the benefits of using the design are real and popular even to the novice researchers and the problems arising from the design are always easily address by experienced researchers

Annali dell'Istituto superiore di sanità

Chiara de Waure

This article describes methodological issues of the "Sportello Salute Giovani" project ("Youth Health Information Desk"), a multicenter study aimed at assessing the health status and attitudes and behaviours of university students in Italy. The questionnaire used to carry out the study was adapted from the Italian health behaviours in school-aged children (HBSC) project and consisted of 93 items addressing: demographics; nutritional habits and status; physical activity; lifestyles; reproductive and preconception health; health and satisfaction of life; attitudes and behaviours toward academic study and new technologies. The questionnaire was administered to a pool of 12 000 students from 18 to 30 years of age who voluntary decided to participate during classes held at different Italian faculties or at the three "Sportello Salute Giovani" centers which were established in the three sites of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Catholic University of...

Trisha Greenhalgh

RELATED PAPERS

Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology. Organization and Management Series

Giorgio Rossetti

JOHN PAUL MIRANDA

APSP Journal of Case Reports

Fatima Malek

Roczniki Filozoficzne

Wojciech Lewandowski

Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria

Soft Matter

Norbert Willenbacher

Revista Katálysis

Virginia Alves Carrara

Revista Cubana de Higiene y …

Herio de Jesus Toledo Vila

Skeletal Radiology

Pratt 毕业证书 普瑞特艺术学院 学位证

Dicitur. Hearsay in Science, Memory and Poetry, Micrologus XXXII (A.Paravicini Bagliani ed.), Florence, SISMEL, p. 435-565

Jacques Chiffoleau

Ciência Rural

Bernardo Baldisserotto

Praxis medica

Tjasa Ivosevic

Juhana Vartiainen

slotpragmatic resmi

Acadia学位证 阿卡迪亚大学毕业证

Indian Journal of Pharmacy Practice

Steward Mudenda, PhD

Nursing in Critical Care

Joanne Garside

Craig Divine

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Engaging With Research

Writing about Research

Determining a topic and finding relevant resources are only the beginning steps in the research process. Once you locate sources, you actually have to read them and determine how useful and relevant they are for your particular research context.

Understanding and Documenting the Information

Remember, our own ethos relies, in part, on the quality of the secondary research sources we use. That is, the sources we use can either add or detract from our overall credibility. Therefore, reviewing, processing, and documenting information is an integral part of the research process. Below, we discuss a variety of strategies for effectively understanding and documenting sources.

Skimming is the process of reading key parts of a text in order to get an overview of an author’s argument and main ideas. There are many different methods for skimming, so you will have to determine which works best for you and your particular source.

Well-written texts such as essays, articles, and book chapters are generally formatted in similar ways:

Introduction: provides the main idea/thesis as well as overview of the text’s structure Body: provides claims, arguments, evidence, support and so on to support thesis Conclusion: provides connections to larger contexts, suggests implications, ask questions, and revisit the main ideas

Ideally, the main ideas will be presented in the introduction, elaborated on in detail in the body, and reviewed in the conclusion. Further, many sources will contain headings or subheadings to organize points and examples, and well-written paragraphs generally have clear topic sentences, or sentences that provide the main idea(s) discussed in the paragraph. All of these aspects will help you skim while developing a sense of the argument and main ideas.

When you skim a source, consider the following process:

- Read the introduction (this could be a few paragraphs long).

- Scan the document for headings. In a shorter article, there may not be any headings or there may be only a couple.

- Whenever you see a new heading, be sure to read at least the first few sentences under the heading and the final few sentences of the section.

- Read the conclusion.

Example: Skimming a Book

When we encounter a text for a first time, it’s a good idea to skim through to see if we need to take a further look at it in our research. One method for doing this is referred to as the First Sentence Technique, which entails reading the introduction, the first sentence of each paragraph, and the conclusion. This approach can be useful for taking notes and creating summaries of sources.

A slightly more in-depth approach can deepen your understanding of the text and help you identify particular sections or even other resources that might be helpful:

- Scan the preface, acknowledgements, and table of contents. (This identifies the methods and framework for the book.)

- Scan the notes at the end of chapters to better understand the author’s research.

- Scan the index to see if the book covers the information you need.

- Read the introductory paragraphs for each chapter. (This can help you better understand the structure and arguments of the book.)

Taking Notes

Taking notes is a central component of the research process. While you skim the articles, record important information, beginning with publication information. Publication information provides a sense of the rhetorical situation for the source, such as intended audience and context. As you encounter texts in your research, consider its role in your project and take note of the publication information as noted. Recording the publication information as you go will help avoid problems or mistakes when citing and building the reference list.

You may think: what should I record from the sources other than the publication information? The goal of research notes is to help you remember information and quickly access important details. You should write down the following details:

- Thesis statement

- Major points or claims

- Evidence, support and/or examples

- Headings (depending on the source)

You may want to write down the thesis, points, and claims exactly as they appear in the source. However, whenever you copy the language exactly, be sure to use quotation marks to indicate that the information is coming directly from a source/author.

Restating the Information in Your Own Words

After taking the time to skim and take notes, you should also put the author’s thesis and ideas into your own words. This ensures that you truly understand the source and the author’s points. There are two major ways to approach this process: summary and paraphrase.

Summaries are condensed versions of the original source, in your own words. Summaries focus on the main ideas, but do not copy any of the original language. A 500 page book or a 2 hour movie could be summarized in a sentence. Summaries do not contain the same level of detail as the original source.

Example: Summary

The following text demonstrates a summary of an original passage:

Original Text

“Lead can enter drinking water when service pipes that contain lead corrode, especially where the water has high acidity or low mineral content that corrodes pipes and fixtures. The most common problem is with brass or chrome-plated brass faucets and fixtures with lead solder, from which significant amounts of lead can enter into the water, especially hot water.”

Water becomes contaminated by lead when lead pipes, solder, or certain types of fixtures degrade, and hot water can increase the amount lead released.

Environmental Protection Agency. (2016). Basic information about lead in drinking water. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/basic-information-about-lead-drinking-water

Similarly, paraphrases are restatements of source material, in your own words, but the difference is that paraphrases tend to be closer in length to the original source. Paraphrases have the same level of detail as the original. Remember, though, if you copy from the original even two or three words in a row you must provide quotation marks around those words.

Example: Paraphrase

Water becomes contaminated by lead when lead pipes or lead solder degrades. Certain types of fixtures, such as those plated with chrome and brass, as well as hot water, acidic water, and water with lower amounts of minerals can make lead contamination significantly worse.

Regardless of whether you choose to directly quote, summarize, or paraphrase a source, you must document the source material. Failure to do so is plagiarism and can lead to allegations of academic or workplace dishonesty.

Annotated Bibliographies*

Annotated bibliographies are a common step in the research process. Annotated bibliographies are exploratory in nature—they help writers organize their thoughts and sources about a topic and help writers determine a direction for their research. Depending on the academic discipline, purpose, and instructor preference, the style, content, and even the name of annotations can vary. This document is a basic overview, so please confirm details of your annotated bibliography with your instructor.

Purposes of an annotated bibliography

For you: During the research and writing process, the annotated bibliography helps you, the researcher, keep track of the changing relevance of sources as you develop your ideas. It also helps you save time by focusing on each author’s essential ideas (which helps you make connections between sources), and it can help you begin the process of composing your project.

For others: During the research process, annotated bibliographies also help show your instructor that you are consulting idea-generating and relevant sources and, more importantly, that you understand the significance of and relationship between your sources. When you seek assistance from your librarian, annotated bibliographies also help the librarian guide you toward the best available sources. Finally, annotated bibliographies help your writing consultant/tutor work with you more efficiently on integrating an author’s ideas into your writing.

What is an annotation?

Generally, an annotation provides a summary of the major ideas in a source, such as the source’s thesis (argument) and major supporting details; an evaluation of the ideas and points in the source; and a sense of how the source connects with your project and other sources in the annotated bibliography.

Questions to consider as you compose your annotation:

- What is the thesis (main argument of the source), and what is the general purpose of the source?

- Who is the author and what are his/her credentials? Who is the intended audience?\

- What theoretical or ideological assumptions does the author advocate, and where or how does that appear in the source?

- What topics does the source cover? What types of evidence does it use?

- What parts of the argument or analysis are particularly persuasive, what parts are not, and why?

- What types of rhetorical appeals (ethos, pathos, logos) does the author use in the development, deployment, and support of their ideas?

- How is this source useful, or not useful, to your project? How does it help you advance the argument for your project?

- How well does the source relate to or not relate to the other sources in your annotated bibliography?

What are the parts of an annotated bibliography?

- The first part of every entry in an annotated bibliography is a citation of the source. Follow the citation style preferred by your instructor.

- The second part of every entry is an annotation or description of the source. Annotations can vary in length, depending on the purposes of the annotated bibliography. Generally, the annotation will contain some information about the author’s credentials/authority, followed by a brief summary of the source, taking into consideration the audience, author’s viewpoint, and the thesis statement. Assessments of the source can appear anywhere, but it is commonly featured at the end of the annotation. Consider whether you found the argument or analysis persuasive, whether this source is useful to you, and why. You may also include any relevant links to other sources.

Sample, APA style:

Tien, F. and Fu, T. (2008). The correlates of the digital divide and their impact on college

student learning. Computers and Education 50(1): 421-436. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2006.07.005

Although Taiwanese scholars 1 Tien and Fu focus on Taiwanese college students, a significant portion of the article is pertinent to a U.S. context. First, the authors acknowledge that most discussion of the “digital divide” incorrectly simplifies the issue of technological access. 2a As a result, they discuss what they call the three dimensions of the digital divide: access; use and knowledge; and skills (422). 2b This recognizes what several other sources in my bibliography have touched upon: access does not mean use nor does it mean knowledge or skills to effectively use digital technologies. 3a Second, they explain that many countries, the US and Taiwan included, depend upon education at all levels to combat the digital divide(s). The issue is that there are deficiencies within educational systems which sometimes work to reinforce the divides already in place. 3b Tien and Fu claim, however, that educational contexts hold the most possibility for combating the digital divide(s). 3c Tien and Fu claim that demographic and socio-economic background had no significant influence on accurately predicting computer use, 3d which contrasts with claims of other sources such as Kirtley. 4 However, gender and major did appear to have an influence on computer use; Tien and Fu note, for example, that female students tended to devote more focused computer time on academic-related work. 3e Overall, the first half of the article that breaks down the different dimensions of the digital divide is the most useful for my project. 5

1. This establishes the authority of the authors and evaluates the source’s usefulness in an American context.

2a/2b. Establishes the argument of the article.

3a. Specific supporting details; establishes connection with other sources in bibliography.

3b/3c/3d/3e. Specific supporting details.

4. Establishes connection to other sources in bibliography.

5. Establishes usefulness for specific project.

*This content adapted from a handout created by the Center for the Study and Teaching of Writing at OSU. Emphasis (color) added and sample modified to APA format.

Research Conversations

Research is about understanding the prevailing opinions, arguments, facts, and details about a given topic. This requires reading what others have already said and published about a topic. We can understand this as the conversation about the topic. For most topics and issues, there can be multiple conversations, each grounded in a specific context, culture, and field of study. Rhetorician Kenneth Burke (1941) calls this the “parlor conversation.”

You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceded you, and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. … You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. Someone answers, you answer him; another comes to your defense; another aligns himself against you. … The hour grows late, you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress. (Burke, 1941, p. 110)

In other words, before you can effectively and persuasively enter into any conversation, you must understand and consider what others have already said. Otherwise you may simply replicate others’ ideas, ask questions or raise issues that have already been resolved, or otherwise lack the knowledge and information needed to make productive and persuasive contributions to the topic.

Academic writing requires presenting your sources and your ideas effectively to readers. According to Graff and Birkenstein (2006), authors of the book They Say, I Say , the first element in the process involves “entering a conversation about ideas” between you—the writer—and your sources to reflect your critical thinking (p. ix). Graff and Birkenstein provide templates (a quick Google search for “They Say I Say templates” brings up many examples) for organizing your ideas in relation to other research, your thesis, supporting evidence, opposing evidence, and the conclusion of your and others’ arguments.

You are likely already aware of the ‘“they say/I say” format. A common version of this is:

“On the one hand, ______________. On the other hand, ______________.”

When talking about research, you might begin with “on the one hand, Researcher X (2015) claims…..” and then insert, “on the other hand, I argue…..” Or, you may use this construction to put two sources in conversation before inserting your ideas. For example:

On the one hand, Researcher X (2015) claims…..On the other hand, Researcher Y (2016) argues…Building on Researcher X and Researcher Y, I contend…

What is most important to remember about integrating research and your own ideas is that you must provide clear attribution of ideas in the text. Attribution is not only about citations, but also about providing textual clues about source material and its origins. Sometimes this is described as introducing and explaining and sometimes it is described as sandwiching a quotation or idea. For example:

According to Researcher X (2015), “information directly quoted from source” (p. 20). That is, [explanation, justification, or other explication on the quoted material].

A Guide to Technical Communications: Strategies & Applications Copyright © 2016 by Lynn Hall & Leah Wahlin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

While Sandel argues that pursuing perfection through genetic engineering would decrease our sense of humility, he claims that the sense of solidarity we would lose is also important.

This thesis summarizes several points in Sandel’s argument, but it does not make a claim about how we should understand his argument. A reader who read Sandel’s argument would not also need to read an essay based on this descriptive thesis.

Broad thesis (arguable, but difficult to support with evidence)

Michael Sandel’s arguments about genetic engineering do not take into consideration all the relevant issues.

This is an arguable claim because it would be possible to argue against it by saying that Michael Sandel’s arguments do take all of the relevant issues into consideration. But the claim is too broad. Because the thesis does not specify which “issues” it is focused on—or why it matters if they are considered—readers won’t know what the rest of the essay will argue, and the writer won’t know what to focus on. If there is a particular issue that Sandel does not address, then a more specific version of the thesis would include that issue—hand an explanation of why it is important.

Arguable thesis with analytical claim

While Sandel argues persuasively that our instinct to “remake” (54) ourselves into something ever more perfect is a problem, his belief that we can always draw a line between what is medically necessary and what makes us simply “better than well” (51) is less convincing.

This is an arguable analytical claim. To argue for this claim, the essay writer will need to show how evidence from the article itself points to this interpretation. It’s also a reasonable scope for a thesis because it can be supported with evidence available in the text and is neither too broad nor too narrow.

Arguable thesis with normative claim

Given Sandel’s argument against genetic enhancement, we should not allow parents to decide on using Human Growth Hormone for their children.

This thesis tells us what we should do about a particular issue discussed in Sandel’s article, but it does not tell us how we should understand Sandel’s argument.

Questions to ask about your thesis

- Is the thesis truly arguable? Does it speak to a genuine dilemma in the source, or would most readers automatically agree with it?

- Is the thesis too obvious? Again, would most or all readers agree with it without needing to see your argument?

- Is the thesis complex enough to require a whole essay's worth of argument?

- Is the thesis supportable with evidence from the text rather than with generalizations or outside research?

- Would anyone want to read a paper in which this thesis was developed? That is, can you explain what this paper is adding to our understanding of a problem, question, or topic?

- picture_as_pdf Thesis

Thinking About the Context: Setting (Where?) and Participants (Who?)

- First Online: 28 March 2017

Cite this chapter

- Kenan Dikilitaş 3 &

- Carol Griffiths 4

1114 Accesses

In recent years, context has come to be recognized as a key element which influences the outcomes of research studies and impacts on their significance. Two important aspects of context are the setting (where the study is taking place) and the participants (who is included in the study). It is critical that both of these aspects are adequately considered and explained so that meaningful conclusions can be drawn from the data. The role of the action-researcher as an active participant in the context also needs thought and explanation.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Educational Sciences, Bahçeşehir University, Istanbul, Turkey

Kenan Dikilitaş

Freelance, Istanbul, Turkey

Carol Griffiths

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Dikilitaş, K., Griffiths, C. (2017). Thinking About the Context: Setting (Where?) and Participants (Who?). In: Developing Language Teacher Autonomy through Action Research. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50739-2_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50739-2_4

Published : 28 March 2017

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-50738-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-50739-2

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

How to Craft Your Ideal Thesis Research Topic

.webp)

Table of contents

Catherine Miller

Writing your undergraduate thesis is probably one of the most interesting parts of studying, especially because you get to choose your area of study. But as both a student and a teacher who’s helped countless students develop their research topics, I know this freedom can be just as intimidating as it is liberating.

Fortunately, there’a a step-by-step process you can follow that will help make the whole process a lot easier. In this article, I’ll show you how to choose a unique, specific thesis topic that’s true to your passions and interests, while making a contribution to your field.

.webp)

Choose a topic that you’re interested in

First things first: double-check with your teachers or supervisor if there are any constraints on your research topic. Once your parameters are clear, it’s time to identify what lights you up — after all, you’re going to be spending a lot of time thinking about it.

Within your field of study, you probably already have some topics that have grabbed your attention more than others. This can be a great place to start. Additionally, consider using the rest of your academic and extra-curricular interests as a source of ideas. At this stage, you only need a broad topic before you narrow it down to a specific question.

If you’re feeling stuck, here are some things to try:

- Look back through old course notes to remind yourself of topics you previously covered. Do any of these inspire you?

- Talk to potential supervisors about your ideas, as they can point you toward areas you might not have considered.

- Think about the things you enjoy in everyday life — whether that’s cycling, cinema, cooking, or fashion — then consider if there are any overlaps with your field of study.

- Imagine you have been asked to give a presentation or record a podcast in the next three days. What topics would you feel confident discussing?

- Watch a selection of existing lectures or explainer videos, or listen to podcasts by experts in your field. Note which topics you feel curious to explore further.

- Discuss your field of study with teachers friends and family, some with existing knowledge and some without. Which aspects do you enjoy talking about?

By doing all this, you might uncover some unusual and exciting avenues for research. For example, when writing my Master’s dissertation, I decided to combine my field of study (English teaching methodology) with one of my passions outside work (creative writing). In my undergraduate course, a friend drew on her lived experience of disability to look into the literary portrayal of disability in the ancient world.

Do your research

Once you’ve chosen your topic of interest, it’s time to dive into research. This is a really important part of this early process because it allows you to:

- See what other people have written about the topic — you don’t want to cover the same old ground as everyone else.

- Gain perspective on the big questions surrounding the topic.

- Go deeper into the parts that interest you to help you decide where to focus.

- Start building your bibliography and a bank of interesting quotations.

A great way to start is to visit your library for an introductory book. For example, the “A Very Short Introduction” series from the Oxford University Press provides overviews of a range of themes. Similar types of overviews may have the title “ A Companion to [Subject]” or “[Subject] A Student Companion”. Ask your librarian or teacher if you’re not sure where to begin.

Your introductory volume can spark ideas for further research, and the bibliography can give you some pointers about where to go next. You can also use keywords to research online via academic sites like JStor or Google Scholar. Check which subscriptions are available via your institution.

At this stage, you may not wish to read every single paper you come across in full — this could take a very long time and not everything will be relevant. Summarizing software like Wordtune could be very useful here.

Just upload a PDF or link to an online article using Wordtune, and it will produce a summary of the whole paper with a list of key points. This helps you to quickly sift through papers to grasp their central ideas and identify which ones to read in full.

Get Wordtune for free > Get Wordtune for free >

You can also use Wordtune for semantic search. In this case, the tool focuses its summary around your chosen search term, making it even easier to get what you need from the paper.

As you go, make sure you keep organized notes of what you’ve read, including the author and publication information and the page number of any citations you want to use.

Some people are happy to do this process with pen and paper, but if you prefer a digital method, there are several software options, including Zotero , EndNote , and Mendeley . Your institution may have an existing subscription so check before you sign up.

Narrowing down your thesis research topic

Now you’ve read around the topic, it’s time to narrow down your ideas so you can craft your final question. For example, when it came to my undergraduate thesis, I knew I wanted to write about Ancient Greek religion and I was interested in the topic of goddesses. So, I:

- Did some wide reading around the topic of goddesses

- Learned that the goddess Hera was not as well researched as others and that there were some fascinating aspects I wanted to explore

- Decided (with my supervisor’s support) to focus on her temples in the Argive region of Greece

As part of this process, it can be helpful to consider the “5 Ws”: why, what, who, when, and where, as you move from the bigger picture to something more precise.

Why did you choose this research topic?

Come back to the reasons you originally chose your theme. What grabbed you? Why is this topic important to you — or to the wider world? In my example, I knew I wanted to write about goddesses because, as a woman, I was interested in how a society in which female lives were often highly controlled dealt with having powerful female deities. My research highlighted Hera as one of the most powerful goddesses, tying into my key interest.

What are some of the big questions about your topic?

During your research, you’ll probably run into the same themes time and time again. Some of the questions that arise may not have been answered yet or might benefit from a fresh look.

Equally, there may be questions that haven’t yet been asked, especially if you are approaching the topic from a modern perspective or combining research that hasn’t been considered before. This might include taking a post-colonial, feminist, or queer approach to older texts or bringing in research using new scientific methods.

In my example, I knew there were still controversies about why so many temples to the goddess Hera were built in a certain region, and was keen to explore these further.

Who is the research topic relevant to?

Considering the “who” might help you open up new avenues. Is there a particular audience you want to reach? What might they be interested in? Is this a new audience for this field? Are there people out there who might be affected by the outcome of this research — for example, people with a particular medical condition — who might be able to use your conclusions?

Which period will you focus on?

Depending on the nature of your field, you might be able to choose a timeframe, which can help narrow the topic down. For example, you might focus on historical events that took place over a handful of years, look at the impact of a work of literature at a certain point after its publication, or review scientific progress over the last five years.

With my thesis, I decided to focus on the time when the temples were built rather than considering the hundreds of years for which they have existed, which would have taken me far too long.

Where does your topic relate to?

Place can be another means of narrowing down the topic. For example, consider the impact of your topic on a particular neighborhood, city, or country, rather than trying to process a global question.

In my example, I chose to focus my research on one area of Greece, where there were lots of temples to Hera. This meant skipping other important locations, but including these would have made the thesis too wide-ranging.

Create an outline and get feedback

Once you have an idea of what you are going to write about, create an outline or summary and get feedback from your teacher(s). It’s okay if you don’t know exactly how you’re going to answer your thesis question yet, but based on your research you should have a rough plan of the key points you want to cover. So, for me, the outline was as follows:

- Context: who was the goddess Hera?

- Overview of her sanctuaries in the Argive region

- Their initial development

- Political and cultural influences

- The importance of the mythical past

In the final thesis, I took a strong view on why the goddess was so important in this region, but it took more research, writing, and discussion with my supervisor to pin down my argument.

To choose a thesis research topic, find something you’re passionate about, research widely to get the big picture, and then move to a more focused view. Bringing a fresh perspective to a popular theme, finding an underserved audience who could benefit from your research, or answering a controversial question can make your thesis stand out from the crowd.

For tips on how to start writing your thesis, don’t miss our advice on writing a great research abstract and a stellar literature review . And don’t forget that Wordtune can also support you with proofreading, making it even easier to submit a polished thesis.

How do you come up with a research topic for a thesis?

To help you find a thesis topic, speak to your professor, look through your old course notes, think about what you already enjoy in everyday life, talk about your field of study with friends and family, and research podcasts and videos to find a topic that is interesting for you. It’s a good idea to refine your topic so that it’s not too general or broad.

Do you choose your own thesis topic?

Yes, you usually choose your own thesis topic. You can get help from your professor(s), friends, and family to figure out which research topic is interesting to you.

Share This Article:

How to Craft an Engaging Elevator Pitch that Gets Results

.webp)

Eight Steps to Craft an Irresistible LinkedIn Profile

.webp)

7 Common Errors in Writing + How to Fix Them (With Examples)

Looking for fresh content, thank you your submission has been received.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Thesis – Structure, Example and Writing Guide

Thesis – Structure, Example and Writing Guide

Table of contents.

Definition:

Thesis is a scholarly document that presents a student’s original research and findings on a particular topic or question. It is usually written as a requirement for a graduate degree program and is intended to demonstrate the student’s mastery of the subject matter and their ability to conduct independent research.

History of Thesis

The concept of a thesis can be traced back to ancient Greece, where it was used as a way for students to demonstrate their knowledge of a particular subject. However, the modern form of the thesis as a scholarly document used to earn a degree is a relatively recent development.

The origin of the modern thesis can be traced back to medieval universities in Europe. During this time, students were required to present a “disputation” in which they would defend a particular thesis in front of their peers and faculty members. These disputations served as a way to demonstrate the student’s mastery of the subject matter and were often the final requirement for earning a degree.

In the 17th century, the concept of the thesis was formalized further with the creation of the modern research university. Students were now required to complete a research project and present their findings in a written document, which would serve as the basis for their degree.

The modern thesis as we know it today has evolved over time, with different disciplines and institutions adopting their own standards and formats. However, the basic elements of a thesis – original research, a clear research question, a thorough review of the literature, and a well-argued conclusion – remain the same.

Structure of Thesis

The structure of a thesis may vary slightly depending on the specific requirements of the institution, department, or field of study, but generally, it follows a specific format.

Here’s a breakdown of the structure of a thesis:

This is the first page of the thesis that includes the title of the thesis, the name of the author, the name of the institution, the department, the date, and any other relevant information required by the institution.

This is a brief summary of the thesis that provides an overview of the research question, methodology, findings, and conclusions.

This page provides a list of all the chapters and sections in the thesis and their page numbers.

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the research question, the context of the research, and the purpose of the study. The introduction should also outline the methodology and the scope of the research.

Literature Review

This chapter provides a critical analysis of the relevant literature on the research topic. It should demonstrate the gap in the existing knowledge and justify the need for the research.

Methodology

This chapter provides a detailed description of the research methods used to gather and analyze data. It should explain the research design, the sampling method, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures.

This chapter presents the findings of the research. It should include tables, graphs, and charts to illustrate the results.

This chapter interprets the results and relates them to the research question. It should explain the significance of the findings and their implications for the research topic.

This chapter summarizes the key findings and the main conclusions of the research. It should also provide recommendations for future research.

This section provides a list of all the sources cited in the thesis. The citation style may vary depending on the requirements of the institution or the field of study.

This section includes any additional material that supports the research, such as raw data, survey questionnaires, or other relevant documents.

How to write Thesis

Here are some steps to help you write a thesis:

- Choose a Topic: The first step in writing a thesis is to choose a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. You should also consider the scope of the topic and the availability of resources for research.

- Develop a Research Question: Once you have chosen a topic, you need to develop a research question that you will answer in your thesis. The research question should be specific, clear, and feasible.

- Conduct a Literature Review: Before you start your research, you need to conduct a literature review to identify the existing knowledge and gaps in the field. This will help you refine your research question and develop a research methodology.

- Develop a Research Methodology: Once you have refined your research question, you need to develop a research methodology that includes the research design, data collection methods, and data analysis procedures.

- Collect and Analyze Data: After developing your research methodology, you need to collect and analyze data. This may involve conducting surveys, interviews, experiments, or analyzing existing data.

- Write the Thesis: Once you have analyzed the data, you need to write the thesis. The thesis should follow a specific structure that includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, conclusion, and references.

- Edit and Proofread: After completing the thesis, you need to edit and proofread it carefully. You should also have someone else review it to ensure that it is clear, concise, and free of errors.

- Submit the Thesis: Finally, you need to submit the thesis to your academic advisor or committee for review and evaluation.

Example of Thesis

Example of Thesis template for Students:

Title of Thesis

Table of Contents:

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Literature Review

Chapter 3: Research Methodology

Chapter 4: Results

Chapter 5: Discussion

Chapter 6: Conclusion

References:

Appendices:

Note: That’s just a basic template, but it should give you an idea of the structure and content that a typical thesis might include. Be sure to consult with your department or supervisor for any specific formatting requirements they may have. Good luck with your thesis!

Application of Thesis

Thesis is an important academic document that serves several purposes. Here are some of the applications of thesis:

- Academic Requirement: A thesis is a requirement for many academic programs, especially at the graduate level. It is an essential component of the evaluation process and demonstrates the student’s ability to conduct original research and contribute to the knowledge in their field.

- Career Advancement: A thesis can also help in career advancement. Employers often value candidates who have completed a thesis as it demonstrates their research skills, critical thinking abilities, and their dedication to their field of study.

- Publication : A thesis can serve as a basis for future publications in academic journals, books, or conference proceedings. It provides the researcher with an opportunity to present their research to a wider audience and contribute to the body of knowledge in their field.

- Personal Development: Writing a thesis is a challenging task that requires time, dedication, and perseverance. It provides the student with an opportunity to develop critical thinking, research, and writing skills that are essential for their personal and professional development.

- Impact on Society: The findings of a thesis can have an impact on society by addressing important issues, providing insights into complex problems, and contributing to the development of policies and practices.

Purpose of Thesis

The purpose of a thesis is to present original research findings in a clear and organized manner. It is a formal document that demonstrates a student’s ability to conduct independent research and contribute to the knowledge in their field of study. The primary purposes of a thesis are:

- To Contribute to Knowledge: The main purpose of a thesis is to contribute to the knowledge in a particular field of study. By conducting original research and presenting their findings, the student adds new insights and perspectives to the existing body of knowledge.

- To Demonstrate Research Skills: A thesis is an opportunity for the student to demonstrate their research skills. This includes the ability to formulate a research question, design a research methodology, collect and analyze data, and draw conclusions based on their findings.

- To Develop Critical Thinking: Writing a thesis requires critical thinking and analysis. The student must evaluate existing literature and identify gaps in the field, as well as develop and defend their own ideas.

- To Provide Evidence of Competence : A thesis provides evidence of the student’s competence in their field of study. It demonstrates their ability to apply theoretical concepts to real-world problems, and their ability to communicate their ideas effectively.

- To Facilitate Career Advancement : Completing a thesis can help the student advance their career by demonstrating their research skills and dedication to their field of study. It can also provide a basis for future publications, presentations, or research projects.

When to Write Thesis

The timing for writing a thesis depends on the specific requirements of the academic program or institution. In most cases, the opportunity to write a thesis is typically offered at the graduate level, but there may be exceptions.

Generally, students should plan to write their thesis during the final year of their graduate program. This allows sufficient time for conducting research, analyzing data, and writing the thesis. It is important to start planning the thesis early and to identify a research topic and research advisor as soon as possible.

In some cases, students may be able to write a thesis as part of an undergraduate program or as an independent research project outside of an academic program. In such cases, it is important to consult with faculty advisors or mentors to ensure that the research is appropriately designed and executed.

It is important to note that the process of writing a thesis can be time-consuming and requires a significant amount of effort and dedication. It is important to plan accordingly and to allocate sufficient time for conducting research, analyzing data, and writing the thesis.

Characteristics of Thesis

The characteristics of a thesis vary depending on the specific academic program or institution. However, some general characteristics of a thesis include:

- Originality : A thesis should present original research findings or insights. It should demonstrate the student’s ability to conduct independent research and contribute to the knowledge in their field of study.

- Clarity : A thesis should be clear and concise. It should present the research question, methodology, findings, and conclusions in a logical and organized manner. It should also be well-written, with proper grammar, spelling, and punctuation.

- Research-Based: A thesis should be based on rigorous research, which involves collecting and analyzing data from various sources. The research should be well-designed, with appropriate research methods and techniques.

- Evidence-Based : A thesis should be based on evidence, which means that all claims made in the thesis should be supported by data or literature. The evidence should be properly cited using appropriate citation styles.

- Critical Thinking: A thesis should demonstrate the student’s ability to critically analyze and evaluate information. It should present the student’s own ideas and arguments, and engage with existing literature in the field.

- Academic Style : A thesis should adhere to the conventions of academic writing. It should be well-structured, with clear headings and subheadings, and should use appropriate academic language.

Advantages of Thesis

There are several advantages to writing a thesis, including:

- Development of Research Skills: Writing a thesis requires extensive research and analytical skills. It helps to develop the student’s research skills, including the ability to formulate research questions, design and execute research methodologies, collect and analyze data, and draw conclusions based on their findings.

- Contribution to Knowledge: Writing a thesis provides an opportunity for the student to contribute to the knowledge in their field of study. By conducting original research, they can add new insights and perspectives to the existing body of knowledge.

- Preparation for Future Research: Completing a thesis prepares the student for future research projects. It provides them with the necessary skills to design and execute research methodologies, analyze data, and draw conclusions based on their findings.

- Career Advancement: Writing a thesis can help to advance the student’s career. It demonstrates their research skills and dedication to their field of study, and provides a basis for future publications, presentations, or research projects.

- Personal Growth: Completing a thesis can be a challenging and rewarding experience. It requires dedication, hard work, and perseverance. It can help the student to develop self-confidence, independence, and a sense of accomplishment.

Limitations of Thesis

There are also some limitations to writing a thesis, including:

- Time and Resources: Writing a thesis requires a significant amount of time and resources. It can be a time-consuming and expensive process, as it may involve conducting original research, analyzing data, and producing a lengthy document.

- Narrow Focus: A thesis is typically focused on a specific research question or topic, which may limit the student’s exposure to other areas within their field of study.

- Limited Audience: A thesis is usually only read by a small number of people, such as the student’s thesis advisor and committee members. This limits the potential impact of the research findings.

- Lack of Real-World Application : Some thesis topics may be highly theoretical or academic in nature, which may limit their practical application in the real world.

- Pressure and Stress : Writing a thesis can be a stressful and pressure-filled experience, as it may involve meeting strict deadlines, conducting original research, and producing a high-quality document.

- Potential for Isolation: Writing a thesis can be a solitary experience, as the student may spend a significant amount of time working independently on their research and writing.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

- About English Wizard Online

- Parts of Speech, Phrases, Sentences

- Spelling/ Vocabulary

- Research/ Thesis Writing

- Lesson Plans

- Worksheets, eBooks, Workbooks, Printables

- Poems (Text and Video)

- Speech/ Pronunciation Lessons

- Classroom Ideas/ Materials

- Teacher's Comments

- Creative and Technical Writing

- Teaching Articles/ Teaching Strategies

- Essays/ Book and Movie Reviews

- Yearbook/ Student Publication/ Magazine/ Newsletter

Sample Locale of the Study in Chapter 3 (Thesis Writing)

No comments:

Post a comment.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write the Rationale of the Study in Research (Examples)

What is the Rationale of the Study?

The rationale of the study is the justification for taking on a given study. It explains the reason the study was conducted or should be conducted. This means the study rationale should explain to the reader or examiner why the study is/was necessary. It is also sometimes called the “purpose” or “justification” of a study. While this is not difficult to grasp in itself, you might wonder how the rationale of the study is different from your research question or from the statement of the problem of your study, and how it fits into the rest of your thesis or research paper.

The rationale of the study links the background of the study to your specific research question and justifies the need for the latter on the basis of the former. In brief, you first provide and discuss existing data on the topic, and then you tell the reader, based on the background evidence you just presented, where you identified gaps or issues and why you think it is important to address those. The problem statement, lastly, is the formulation of the specific research question you choose to investigate, following logically from your rationale, and the approach you are planning to use to do that.

Table of Contents:

How to write a rationale for a research paper , how do you justify the need for a research study.

- Study Rationale Example: Where Does It Go In Your Paper?

The basis for writing a research rationale is preliminary data or a clear description of an observation. If you are doing basic/theoretical research, then a literature review will help you identify gaps in current knowledge. In applied/practical research, you base your rationale on an existing issue with a certain process (e.g., vaccine proof registration) or practice (e.g., patient treatment) that is well documented and needs to be addressed. By presenting the reader with earlier evidence or observations, you can (and have to) convince them that you are not just repeating what other people have already done or said and that your ideas are not coming out of thin air.

Once you have explained where you are coming from, you should justify the need for doing additional research–this is essentially the rationale of your study. Finally, when you have convinced the reader of the purpose of your work, you can end your introduction section with the statement of the problem of your research that contains clear aims and objectives and also briefly describes (and justifies) your methodological approach.

When is the Rationale for Research Written?

The author can present the study rationale both before and after the research is conducted.

- Before conducting research : The study rationale is a central component of the research proposal . It represents the plan of your work, constructed before the study is actually executed.

- Once research has been conducted : After the study is completed, the rationale is presented in a research article or PhD dissertation to explain why you focused on this specific research question. When writing the study rationale for this purpose, the author should link the rationale of the research to the aims and outcomes of the study.

What to Include in the Study Rationale

Although every study rationale is different and discusses different specific elements of a study’s method or approach, there are some elements that should be included to write a good rationale. Make sure to touch on the following:

- A summary of conclusions from your review of the relevant literature

- What is currently unknown (gaps in knowledge)

- Inconclusive or contested results from previous studies on the same or similar topic

- The necessity to improve or build on previous research, such as to improve methodology or utilize newer techniques and/or technologies

There are different types of limitations that you can use to justify the need for your study. In applied/practical research, the justification for investigating something is always that an existing process/practice has a problem or is not satisfactory. Let’s say, for example, that people in a certain country/city/community commonly complain about hospital care on weekends (not enough staff, not enough attention, no decisions being made), but you looked into it and realized that nobody ever investigated whether these perceived problems are actually based on objective shortages/non-availabilities of care or whether the lower numbers of patients who are treated during weekends are commensurate with the provided services.

In this case, “lack of data” is your justification for digging deeper into the problem. Or, if it is obvious that there is a shortage of staff and provided services on weekends, you could decide to investigate which of the usual procedures are skipped during weekends as a result and what the negative consequences are.

In basic/theoretical research, lack of knowledge is of course a common and accepted justification for additional research—but make sure that it is not your only motivation. “Nobody has ever done this” is only a convincing reason for a study if you explain to the reader why you think we should know more about this specific phenomenon. If there is earlier research but you think it has limitations, then those can usually be classified into “methodological”, “contextual”, and “conceptual” limitations. To identify such limitations, you can ask specific questions and let those questions guide you when you explain to the reader why your study was necessary:

Methodological limitations

- Did earlier studies try but failed to measure/identify a specific phenomenon?

- Was earlier research based on incorrect conceptualizations of variables?

- Were earlier studies based on questionable operationalizations of key concepts?

- Did earlier studies use questionable or inappropriate research designs?

Contextual limitations

- Have recent changes in the studied problem made previous studies irrelevant?

- Are you studying a new/particular context that previous findings do not apply to?

Conceptual limitations

- Do previous findings only make sense within a specific framework or ideology?

Study Rationale Examples

Let’s look at an example from one of our earlier articles on the statement of the problem to clarify how your rationale fits into your introduction section. This is a very short introduction for a practical research study on the challenges of online learning. Your introduction might be much longer (especially the context/background section), and this example does not contain any sources (which you will have to provide for all claims you make and all earlier studies you cite)—but please pay attention to how the background presentation , rationale, and problem statement blend into each other in a logical way so that the reader can follow and has no reason to question your motivation or the foundation of your research.

Background presentation

Since the beginning of the Covid pandemic, most educational institutions around the world have transitioned to a fully online study model, at least during peak times of infections and social distancing measures. This transition has not been easy and even two years into the pandemic, problems with online teaching and studying persist (reference needed) .

While the increasing gap between those with access to technology and equipment and those without access has been determined to be one of the main challenges (reference needed) , others claim that online learning offers more opportunities for many students by breaking down barriers of location and distance (reference needed) .

Rationale of the study

Since teachers and students cannot wait for circumstances to go back to normal, the measures that schools and universities have implemented during the last two years, their advantages and disadvantages, and the impact of those measures on students’ progress, satisfaction, and well-being need to be understood so that improvements can be made and demographics that have been left behind can receive the support they need as soon as possible.

Statement of the problem

To identify what changes in the learning environment were considered the most challenging and how those changes relate to a variety of student outcome measures, we conducted surveys and interviews among teachers and students at ten institutions of higher education in four different major cities, two in the US (New York and Chicago), one in South Korea (Seoul), and one in the UK (London). Responses were analyzed with a focus on different student demographics and how they might have been affected differently by the current situation.

How long is a study rationale?

In a research article bound for journal publication, your rationale should not be longer than a few sentences (no longer than one brief paragraph). A dissertation or thesis usually allows for a longer description; depending on the length and nature of your document, this could be up to a couple of paragraphs in length. A completely novel or unconventional approach might warrant a longer and more detailed justification than an approach that slightly deviates from well-established methods and approaches.

Consider Using Professional Academic Editing Services

Now that you know how to write the rationale of the study for a research proposal or paper, you should make use of our free AI grammar checker , Wordvice AI, or receive professional academic proofreading services from Wordvice, including research paper editing services and manuscript editing services to polish your submitted research documents.

You can also find many more articles, for example on writing the other parts of your research paper , on choosing a title , or on making sure you understand and adhere to the author instructions before you submit to a journal, on the Wordvice academic resources pages.

How to Write a Research Paper

- Smodin Editorial Team

- Updated: May 17, 2024

Most students hate writing research papers. The process can often feel long, tedious, and sometimes outright boring. Nevertheless, these assignments are vital to a student’s academic journey. Want to learn how to write a research paper that captures the depth of the subject and maintains the reader’s interest? If so, this guide is for you.

Today, we’ll show you how to assemble a well-organized research paper to help you make the grade. You can transform any topic into a compelling research paper with a thoughtful approach to your research and a persuasive argument.

In this guide, we’ll provide seven simple but practical tips to help demystify the process and guide you on your way. We’ll also explain how AI tools can expedite the research and writing process so you can focus on critical thinking.

By the end of this article, you’ll have a clear roadmap for tackling these essays. You will also learn how to tackle them quickly and efficiently. With time and dedication, you’ll soon master the art of research paper writing.

Ready to get started?

What Is a Research Paper?

A research paper is a comprehensive essay that gives a detailed analysis, interpretation, or argument based on your own independent research. In higher-level academic settings, it goes beyond a simple summarization and includes a deep inquiry into the topic or topics.

The term “research paper” is a broad term that can be applied to many different forms of academic writing. The goal is to combine your thoughts with the findings from peer-reviewed scholarly literature.

By the time your essay is done, you should have provided your reader with a new perspective or challenged existing findings. This demonstrates your mastery of the subject and contributes to ongoing scholarly debates.

7 Tips for Writing a Research Paper

Often, getting started is the most challenging part of a research paper. While the process can seem daunting, breaking it down into manageable steps can make it easier to manage. The following are seven tips for getting your ideas out of your head and onto the page.

1. Understand Your Assignment

It may sound simple, but the first step in writing a successful research paper is to read the assignment. Sit down, take a few moments of your time, and go through the instructions so you fully understand your assignment.

Misinterpreting the assignment can not only lead to a significant waste of time but also affect your grade. No matter how patient your teacher or professor may be, ignoring basic instructions is often inexcusable.

If you read the instructions and are still confused, ask for clarification before you start writing. If that’s impossible, you can use tools like Smodin’s AI chat to help. Smodin can help highlight critical requirements that you may overlook.

This initial investment ensures that all your future efforts will be focused and efficient. Remember, thinking is just as important as actually writing the essay, and it can also pave the wave for a smoother writing process.

2. Gather Research Materials

Now comes the fun part: doing the research. As you gather research materials, always use credible sources, such as academic journals or peer-reviewed papers. Only use search engines that filter for accredited sources and academic databases so you can ensure your information is reliable.

To optimize your time, you must learn to master the art of skimming. If a source seems relevant and valuable, save it and review it later. The last thing you want to do is waste time on material that won’t make it into the final paper.

To speed up the process even more, consider using Smodin’s AI summarizer . This tool can help summarize large texts, highlighting key information relevant to your topic. By systematically gathering and filing research materials early in the writing process, you build a strong foundation for your thesis.

3. Write Your Thesis

Creating a solid thesis statement is the most important thing you can do to bring structure and focus to your research paper. Your thesis should express the main point of your argument in one or two simple sentences. Remember, when you create your thesis, you’re setting the tone and direction for the entire paper.

Of course, you can’t just pull a winning thesis out of thin air. Start by brainstorming potential thesis ideas based on your preliminary research. And don’t overthink things; sometimes, the most straightforward ideas are often the best.

You want a thesis that is specific enough to be manageable within the scope of your paper but broad enough to allow for a unique discussion. Your thesis should challenge existing expectations and provide the reader with fresh insight into the topic. Use your thesis to hook the reader in the opening paragraph and keep them engaged until the very last word.

4. Write Your Outline

An outline is an often overlooked but essential tool for organizing your thoughts and structuring your paper. Many students skip the outline because it feels like doing double work, but a strong outline will save you work in the long run.

Here’s how to effectively structure your outline.

- Introduction: List your thesis statement and outline the main questions your essay will answer.

- Literature Review: Outline the key literature you plan to discuss and explain how it will relate to your thesis.

- Methodology: Explain the research methods you will use to gather and analyze the information.

- Discussion: Plan how you will interpret the results and their implications for your thesis.

- Conclusion: Summarize the content above to elucidate your thesis fully.

To further streamline this process, consider using Smodin’s Research Writer. This tool offers a feature that allows you to generate and tweak an outline to your liking based on the initial input you provide. You can adjust this outline to fit your research findings better and ensure that your paper remains well-organized and focused.

5. Write a Rough Draft

Once your outline is in place, you can begin the writing process. Remember, when you write a rough draft, it isn’t meant to be perfect. Instead, use it as a working document where you can experiment with and rearrange your arguments and evidence.

Don’t worry too much about grammar, style, or syntax as you write your rough draft. Focus on getting your ideas down on paper and flush out your thesis arguments. You can always refine and rearrange the content the next time around.

Follow the basic structure of your outline but with the freedom to explore different ways of expressing your thoughts. Smodin’s Essay Writer offers a powerful solution for those struggling with starting or structuring their drafts.

After you approve the outline, Smodin can generate an essay based on your initial inputs. This feature can help you quickly create a comprehensive draft, which you can then review and refine. You can even use the power of AI to create multiple rough drafts from which to choose.

6. Add or Subtract Supporting Evidence

Once you have a rough draft, but before you start the final revision, it’s time to do a little cleanup. In this phase, you need to review all your supporting evidence. You want to ensure that there is nothing redundant and that you haven’t overlooked any crucial details.

Many students struggle to make the required word count for an essay and resort to padding their writing with redundant statements. Instead of adding unnecessary content, focus on expanding your analysis to provide deeper insights.

A good essay, regardless of the topic or format, needs to be streamlined. It should convey clear, convincing, relevant information supporting your thesis. If you find some information doesn’t do that, consider tweaking your sources.

Include a variety of sources, including studies, data, and quotes from scholars or other experts. Remember, you’re not just strengthening your argument but demonstrating the depth of your research.

If you want comprehensive feedback on your essay without going to a writing center or pestering your professor, use Smodin. The AI Chat can look at your draft and offer suggestions for improvement.

7. Revise, Cite, and Submit

The final stages of crafting a research paper involve revision, citation, and final review. You must ensure your paper is polished, professionally presented, and plagiarism-free. Of course, integrating Smodin’s AI tools can significantly streamline this process and enhance the quality of your final submission.

Start by using Smodin’s Rewriter tool. This AI-powered feature can help rephrase and refine your draft to improve overall readability. If a specific section of your essay just “doesn’t sound right,” the AI can suggest alternative sentence structures and word choices.

Proper citation is a must for all academic papers. Thankfully, thanks to Smodin’s Research Paper app, this once tedious process is easier than ever. The AI ensures all sources are accurately cited according to the required style guide (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

Plagiarism Checker:

All students need to realize that accidental plagiarism can happen. That’s why using a Plagiarism Checker to scan your essay before you submit it is always useful. Smodin’s Plagiarism Checker can highlight areas of concern so you can adjust accordingly.

Final Submission

After revising, rephrasing, and ensuring all citations are in order, use Smodin’s AI Content Detector to give your paper one last review. This tool can help you analyze your paper’s overall quality and readability so you can make any final tweaks or improvements.

Mastering Research Papers

Mastering the art of the research paper cannot be overstated, whether you’re in high school, college, or postgraduate studies. You can confidently prepare your research paper for submission by leveraging the AI tools listed above.

Research papers help refine your abilities to think critically and write persuasively. The skills you develop here will serve you well beyond the walls of the classroom. Communicating complex ideas clearly and effectively is one of the most powerful tools you can possess.

With the advancements of AI tools like Smodin , writing a research paper has become more accessible than ever before. These technologies streamline the process of organizing, writing, and revising your work. Write with confidence, knowing your best work is yet to come!

How Much Research Is Being Written by Large Language Models?

New studies show a marked spike in LLM usage in academia, especially in computer science. What does this mean for researchers and reviewers?

In March of this year, a tweet about an academic paper went viral for all the wrong reasons. The introduction section of the paper, published in Elsevier’s Surfaces and Interfaces , began with this line: Certainly, here is a possible introduction for your topic.

Look familiar?

It should, if you are a user of ChatGPT and have applied its talents for the purpose of content generation. LLMs are being increasingly used to assist with writing tasks, but examples like this in academia are largely anecdotal and had not been quantified before now.

“While this is an egregious example,” says James Zou , associate professor of biomedical data science and, by courtesy, of computer science and of electrical engineering at Stanford, “in many cases, it’s less obvious, and that’s why we need to develop more granular and robust statistical methods to estimate the frequency and magnitude of LLM usage. At this particular moment, people want to know what content around us is written by AI. This is especially important in the context of research, for the papers we author and read and the reviews we get on our papers. That’s why we wanted to study how much of those have been written with the help of AI.”

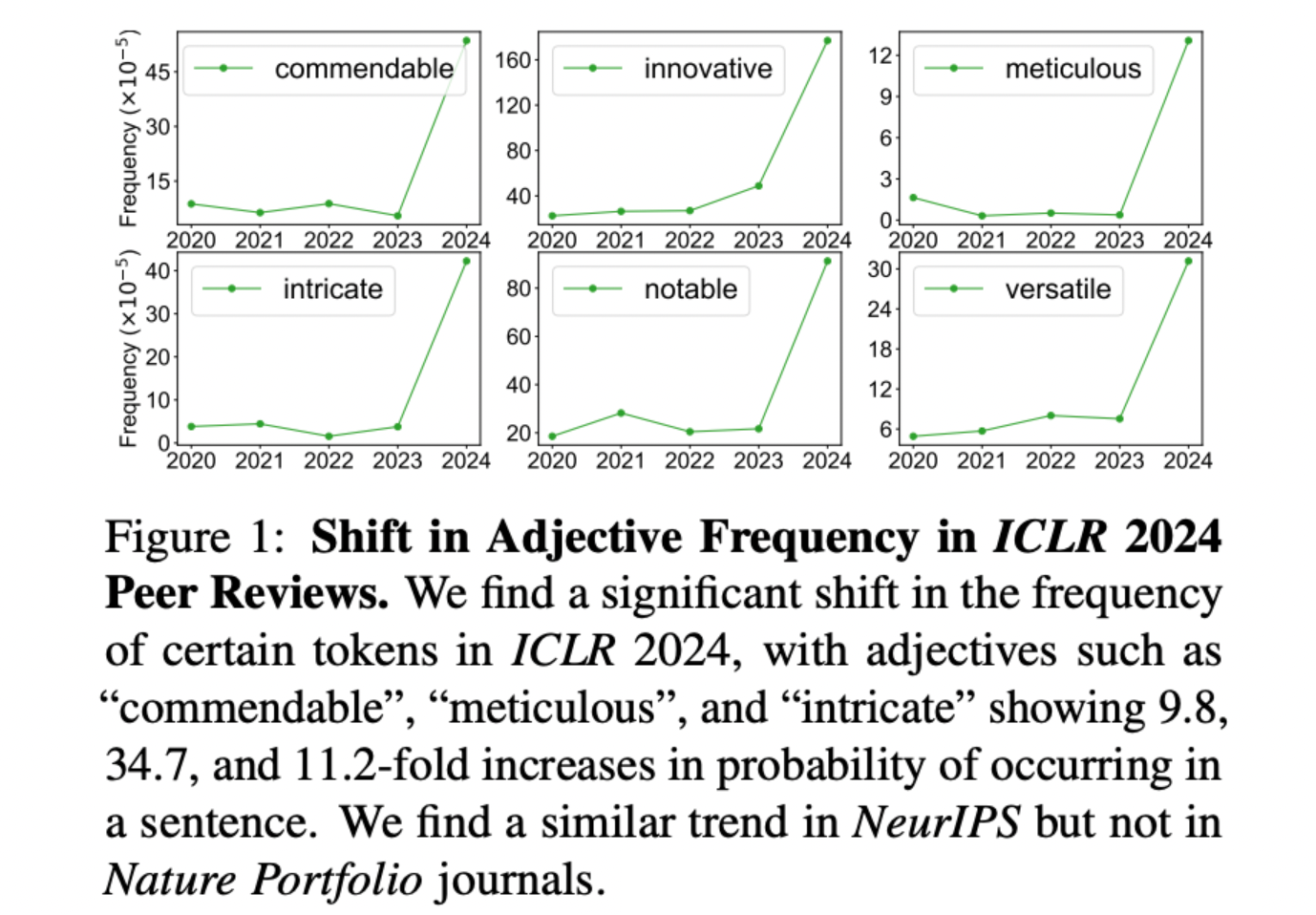

In two papers looking at LLM use in scientific publishings, Zou and his team* found that 17.5% of computer science papers and 16.9% of peer review text had at least some content drafted by AI. The paper on LLM usage in peer reviews will be presented at the International Conference on Machine Learning.

Read Mapping the Increasing Use of LLMs in Scientific Papers and Monitoring AI-Modified Content at Scale: A Case Study on the Impact of ChatGPT on AI Conference Peer Reviews

Here Zou discusses the findings and implications of this work, which was supported through a Stanford HAI Hoffman Yee Research Grant .

How did you determine whether AI wrote sections of a paper or a review?

We first saw that there are these specific worlds – like commendable, innovative, meticulous, pivotal, intricate, realm, and showcasing – whose frequency in reviews sharply spiked, coinciding with the release of ChatGPT. Additionally, we know that these words are much more likely to be used by LLMs than by humans. The reason we know this is that we actually did an experiment where we took many papers, used LLMs to write reviews of them, and compared those reviews to reviews written by human reviewers on the same papers. Then we quantified which words are more likely to be used by LLMs vs. humans, and those are exactly the words listed. The fact that they are more likely to be used by an LLM and that they have also seen a sharp spike coinciding with the release of LLMs is strong evidence.

Some journals permit the use of LLMs in academic writing, as long as it’s noted, while others, including Science and the ICML conference, prohibit it. How are the ethics perceived in academia?

This is an important and timely topic because the policies of various journals are changing very quickly. For example, Science said in the beginning that they would not allow authors to use language models in their submissions, but they later changed their policy and said that people could use language models, but authors have to explicitly note where the language model is being used. All the journals are struggling with how to define this and what’s the right way going forward.

You observed an increase in usage of LLMs in academic writing, particularly in computer science papers (up to 17.5%). Math and Nature family papers, meanwhile, used AI text about 6.3% of the time. What do you think accounts for the discrepancy between these disciplines?

Artificial intelligence and computer science disciplines have seen an explosion in the number of papers submitted to conferences like ICLR and NeurIPS. And I think that’s really caused a strong burden, in many ways, to reviewers and to authors. So now it’s increasingly difficult to find qualified reviewers who have time to review all these papers. And some authors may feel more competition that they need to keep up and keep writing more and faster.

You analyzed close to a million papers on arXiv, bioRxiv, and Nature from January 2020 to February 2024. Do any of these journals include humanities papers or anything in the social sciences?