- Conversations

- Photo essays

- Exhibitions

- TKC Archive

- NuktaArt archive

- contributors

- partner with us

The Indian subcontinent in 1947 was divided into two countries and three parts: India, West Pakistan and East Pakistan. My essay aims to look into the development of the film industries of the subcontinent, with a focus on Pakistan. Moreover, when in 1971 Pakistan was fractured, and East Pakistan was lost, how did it affect Pakistan’s films culturally and socially?

The Beginnings of Pakistan’s Film Industry

The British divided the subcontinent in a casual and sloppy manner, leaving it in shambles. We know about the blood bath that followed and the migration that took place on both sides. In July 1947, five weeks before the British were to leave the subcontinent, a British lawyer, Cyril Radcliffe, was commissioned to draw the borders that would divide British India into two countries.

“Partition’s effect on the film industries of the two countries was radically different. While India lost some good talent, Pakistan had to literally restart from scratch.” 1

Even though the film industry in India, particularly in Bombay, was truly cosmopolitan and secular in nature, some people from the industry did relocate. Those who chose to come to Pakistan did so because of their own personal sentiments. Though there was loss of some good talent in India, it was pretty much business as usual in Bombay and in other film centres across the country. However, the Bengali film industry of Calcutta (Kolkata) did suffer, as a large portion of its market got taken away by the East wing of Pakistan.

Singing star Noor Jehan, who was born in Qasur, Punjab, and actor Swaran Lata who was born in Rawalpindi, were both Hindi cinema’s top female stars, who opted to return to this side of the border where they were born. Writer Saadat Hasan Manto, filmmakers Shaukat Hussain Rizvi (who was married to Noor Jehan), WZ Ahmed, Zia Sarhadi, and actor, director, producer Nazir Ahmed Khan (he was married to Swaran Lata), as well as composers Feroz Nizami, Ghulam Haider, and later Khwaja Khurshid Anwar also migrated to Pakistan. Nonetheless, these were rare instances of big names within the Indian film industry who opted for Pakistan, as most of the others who left, had played character roles, or whose careers had begun to decline. Many Muslim actors, technicians, etc. who were doing well for themselves preferred to stay back in India. There were also some prominent Hindu artists who left for India from Lahore, including actors Pran and Om Prakash, and filmmakers Dalsukh M Pancholi and Roop K Shorey.

However, a Hindu distributor, Jagdish Chand Anand (better known as JC Anand), preferred to stay back in Pakistan, and went on to become one of the most successful producer-distributors across the border. In 1946, he had formed his own company, Eveready Pictures, and after 1947, by distributing Indian films – in particular the hit Mahal (1949) from Bombay Talkies, and Raj Kapoor’s films, including Barsaat (1949) and Awara (1951), he did not look back.

Eveready Pictures was the only film company operating across East and West Pakistan. JC Anand died in Karachi in 1977. He left behind a rich cinematic legacy, and his son, Satish Anand has been running the Eveready Group of Companies in Karachi ever since. I met Satish Anand in his office a few years ago, and learnt that in the last 70 + years his company has released over 650 Hollywood, Bollywood and Pakistani feature films.

Unlike India, where there were film centres in Bombay, Calcutta and Madras, Pakistan only had Lahore for making films. The two major studios there, owned by Pancholi Art Pictures and Shorey Pictures, were razed to the ground in the communal riots of 1947. The Pakistani film industry therefore had no proper funding or any technical infrastructure. It struggled to make its first film, Teri Yaad, directed by Dawood Chand, which was released on Eid-ul-Fitr in August 1948. But despite Dilip Kumar’s brother Nasir Khan, and Asha Posley (who also sang her own songs in the film) starring in it, the film failed completely. It had very poor production and technical standards. Yet, Teri Yaad signaled the birth of a new film industry in South Asia.

The film-going audience, who now lived in Pakistan, was used to watching better films from the pre-Partition era. Not only were the stories, songs and dances more commendable, but also the technical expertise of Indian films was better. From the mid-1950s onwards, in order to cater to that taste, some ground-breaking efforts of dedicated filmmakers such as Nazir, WZ Ahmed, Anwar Kamal Pasha and Sibtain Fazli made it possible for the Pakistani cinema to move forward. They overcame huge obstacles to create a feasible industry by giving opportunities to new actors. These included Santosh Kumar (whose real name was Moosa Raza), and Sabiha Khanum, who later became his life partner. The two can be termed as the first film couple/family of Pakistan. While Santosh was the romantic hero, Sudhir, better known as Lala Sudhir, was the action hero of several Urdu and Punjabi films.

Some years after Independence, there was an effort to ban the exhibition of Hindi films in Pakistan in order to help the indigenous film industry to flourish. Finally, in 1965, after the second war between Pakistan and India was fought, Indian films were banned by General Mohammad Ayub Khan. It was after more than 40 years that another military ruler, General Pervez Musharraf, removed that ban.

It is interesting to note that despite the diplomatic tensions, as hot and cold winds have kept blowing between the two nuclear-armed countries, Pakistani and Indian actors, singers and writers have had a long history of collaboration. These include actors Zia Mohyeddin, Nadeem, Talat Hussain, Zeba Bakhtiar, Javed Sheikh, Salman Shahid, Saba Qamar, Humaima Malick, Sajal Ali, Fawad Khan and Mahira Khan; singers Ghulam Ali, Nusrat Fateh Ali, Rahat Fateh Ali, Shafqat Amanat Ali Khan, Atif Aslam, and Ali Zafar; writers Haseena Moin and Syed Mohammed Ahmed. They were all invited to work for the Indian cinema on various projects.

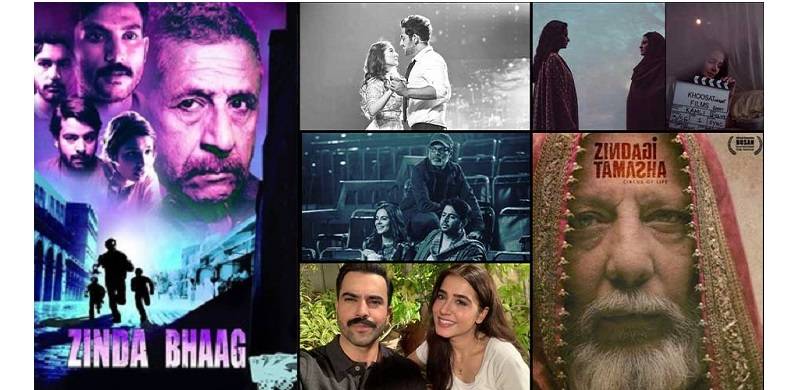

Indian actors who have worked in Pakistani films include Kirron Kher, Nandita Das, Naseeruddin Shah, Johnny Lever, Om Puri, Vinod Khanna, Shweta, Arbaaz Khan, Gulshan Grover and Neha Dhupia, and singers Talat Mehmood Hemant Kumar, Asha Bhosle, Sonu Nigam and Mika Singh who lent their voices to Pakistani films.

Fast forward to 2016, the Uri attack happened in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir in which 19 Indian soldiers were killed. Three years later, in 2019, India accused Pakistan for the Pulwama attack – a charge Pakistan denies, but after Pulwama the All Indian Cine Workers Association announced a total ban on Pakistani artists from working in Bollywood. In 2017 the famous Pakistani actor Mahira Khan had made her Bollywood debut opposite India’s Shahrukh Khan in Raees but she could not travel to India to promote the film. Similarly, popular Pakistani hero Fawad Khan’s career in Indian films also came to a sudden halt.

As compared to other arts, especially through literature, filmmakers on either side of the border have only occasionally explored the subject of Partition. This is especially true in the early years following independence. Lahore (1949), starring Nargis and Karan Dewan was the earliest Indian film that had Partition as its backdrop, while Pakistan first explored it in Masud Parvaiz’s Beli (1950), written by Sadat Hasan Manto, in which Sabiha and Santosh had acted.

“Around a dozen (Pakistani) movies have been made on the issue of Partition: Kartar Singh (Saifudin Saif -1959), Khaak aur Khoon (Masud Pervaiz -1979), Tauba (S A Hafiz -1964), Lakhon Mein Eik (Raza Mir -1967), Behen Bhai (Hasan Tariq -1968) and Pehli Nazar (Islam Dar – 1977). All these movies fared well on the commercial circuits, with Kartar Singh becoming a record breaker and very popular in India as well. 2

Until 1971, Pakistan had three main film production centers – Lahore, Karachi and Dhaka. Lollywood, based in Lahore, has been the largest. By and large, Bollywood and Lollywood films are formulaic entertaining appropriations of drama, comedy, music, and dance – popularly known as masala films, but several others have also been made that explore unusual, off-the-beaten-track stories.

According to a Pakistani film analyst Omar Adil, “this lack of cinematic coverage of the Partition of Bengal largely was due to the fact that mainstream moviemakers were not only based in Lahore and Bombay, but also that the bulk of people associated with cinema in the shape of writers, directors, actors and lyricists also hailed largely from Punjab, and what they brought out on cinema appealed to an audience that could personally as well as culturally identify itself with the milieu.”

It must be mentioned that in 1959, film Jago Hua Savera , for which the screenplay was written by none other than Faiz Ahmed Faiz, was shot in East Pakistan, and directed by A. J. Kardar, who was from West Pakistan. He selected Zahir Raihan from Dhaka as his assistant. The film was made in both Urdu and Bengali.

East Pakistan produced some riveting Urdu films in the ‘60s, with actor Rahman making his Urdu film debut in 1962 in Chanda , directed by Ehtesham, who presented in the film a new actor, Jharna Basak as ‘Shabnam’. She became a superstar of the industry as she gave one hit after another. The talented Robin Ghosh (who married Shabnam) had composed the music of Chanda. The success of that film as well as several others made both of them stars, and they were advised to work in West Pakistan. Shabnam ruled the hearts of movie-goers, and remained active in Dhaka, then Lollywood in the late 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. In the late 1990s she relocated to Dhaka.

In the same year as Chanda , i.e. 1962, in West Pakistan actor Waheed Murad, who later came to be dubbed ‘the chocolate hero’ made his debut as a supporting actor in Aulad. Waheed Murad’s father Nisar Murad was a film distributor, and Waheed had entered the industry as a producer when in 1960 he produced Insaan Badalta Hai , starring Santosh Kumar’s younger brother Darpan opposite Shamim Ara in the lead.

Actors Waheed Murad and Zeba, music director Sohail Rana, singers Mala and Ahmed Rushdi, writer Masroor Anwar and director Pervez Malik emerged as a team of unbeatable artistes who gave the Pakistani film industry some unforgettable films, including its first platinum jubilee feature film, Armaan (1966), which also introduced audiences to the first South Asian pop song: “ Ko ko ko rina… ” creating a new genre of Pakistani disco music.

Another movie that became a milestone in Waheed Murad’s career was film Anjuman (1970), with Rani playing the role of a courtesan opposite him. Zeba married another popular Lollywood actor, Mohammad Ali.

In 1967 the film audiences of East and West Pakistan were introduced to singer and actor Nadeem, who made his debut in Chakori, a film by Ehtesham – the acclaimed director from Dhaka. Like the numerous other movies for which Robin Ghosh continued to compose music, Chakori also had lilting songs. Nadeem had joined the industry wanting to be a singer, but as luck would have it, he became an extremely successful actor instead.

The Loss of East Pakistan in 1971: Consequences on Pakistan’s Film Industry

Similar to the physical distance of over 2,000 kms between East and West Pakistan, there was a stark difference between the Bengali and West Pakistani culture as well as sensibilities, even if the films from the east or the west wing depicted some common subjects such as class divides, rural and urban struggles, college romance, or love between a rich girl and poor boy (or vice versa).

On December 16, 1971, after a bloody and tragic civil war, Pakistan lost its Eastern wing, which gained independence as Bangladesh.

“The loss of East Pakistan was not just devastating on a psychological, economic or political level. In very real terms, it also affected Pakistan culturally and socially.” 3

Zahir Raihan had been one of the most promising directors of united Pakistan. A prolific writer and journalist himself, Zahir had practical filmmaking experience as chief assistant director of Jago Hua Savera . He produced and directed Pakistan’s first colour film Sangam (1964), which was possible to make since the first colour-film processing laboratory was set up in Dhaka. Sangam was shot in Eastman Colour on location in the beautiful Chittagong Hill Tracts and Kaptai Lake. It is pertinent to mention here that the West Pakistani colour film Naila was released in 1965. It was shot in Agfa Colour. Raihan also made Pakistan’s first Cinemascope movie Bahana (1965), and he directed a number of artistic Bengali films too. He was not only a film director but also a politically charged novelist. His novels provided excruciating portrayals of social injustice, raising the consciousness of his readers; motivating them to protest against those injustices.

For Pakistan, together with the loss of a brilliant director, many other creative people, including other directors, actors, writers, lyricists, singers, and skilled technicians, as also a major production centre and market was lost.

The Bengali-Muslim cultural identity portrayed idyllic East Bengal settings in the Urdu films, showing rustic villages, serene rivers and boats, accompanied by enchanting music. There were saree-wearing women who adorned their long lustrous hair with flowers, and their foreheads with bindis as this had nothing to do with religion, but were purely secular cultural statements. It was all quite simple and basic, and those films were watched in the entire country. But after the fall of Dhaka, it took over a decade for the Pakistan film industry to recover.

In 1977, another disaster struck the country in the form of General Zia-ul-Haq. He seized power in a military coup and enforced an ultra-conservative Islamisation agenda, bringing in strict censorship laws. Due to the stifling overall environment for creative pursuits, there was lack of quality films.

“Contrary to popular belief, the collapse of the Pakistan film industry was not a gradual process. In fact the crumbling was a rather sudden happening. 4

“This was also the time when the practice of turning cinemas into ‘shopping plazas’ kicked in, with Karachi’s famous Naz Cinema becoming the first casualty.

“Interestingly though, these policies and restrictions that barred filmmakers from showing ‘excessive sexual content and violence,’ seemed only to have been targeted at Urdu films because there was a two-fold growth in the number of Punjabi and Pushtu films, in spite of the fact that they were studded with sexual raunchiness and anarchic violence.”

In August 1988, after General Zia was killed in a plane crash, the democratic government of Benazir Bhutto was established, and a few gallant filmmakers made some very good films on contemporary issues; thereof the middle-classes started to return to the cinema in the 1990s. There are innumerable eminent actors, producers, directors, composers, singers and cinematographers who have been associated with the Pakistani film industry, but unfortunately it is not possible to name them all in this essay.

In the new millennium, multiplex cinemas started coming up in major cities of Pakistan, which further prompted the return of the film-goers, albeit those who could afford the price of the tickets. It wasn’t only the venues either, but the kind of cinema that was being offered by a class of filmmakers who were from educated, modern middle-class backgrounds that was appealing for the audience.

At the end, I would like to quote this line written in an article by a former student of mine: “…instead of a New Wave, or the even more abused term Revival, let me christen this moment the Return of Cinema to Pakistan.” 5

Director-producer Mushtaq Gazdar founded Films d’Art in 1967 when there wasn’t much interest in Pakistan for documentaries and independent films. He wrote, directed and produced almost 200 short films, documentaries and newsreels during his career. His seminal work, a voluminous hard-cover book titled ‘Pakistan Cinema 1947-1997’ was published by Oxford University Press to mark Pakistan’s fifty years. He wrote about the dislocation of people at Partition, the military rulers of Pakistan, and how those socio-cultural-political developments impacted the Pakistani society, and its cinema. Gazdar passed away in the year 2000. The book was later updated by his children Aisha and Haris for its second edition. Aisha Gazdar is herself a producer-director, and Haris Gazdar is a social scientist, and they have included in it a sociopolitical analysis of the films made after 1997.

Two other books, ‘The Cinema of Pakistan’ (1969) and ‘Film in Bangladesh’ (1979) by film-maker and critic Alamgir Kabir – he died in 1989 – present a wealth of historical detail. And more recently, in 2016 a book titled ‘Cinema and Society: Film and Social Change in Pakistan’, edited by two academics, Ali Khan and Ali Nobil Ahmad was also published by Oxford University Press. This book has several essays, memoirs, journalistic and scholarly writings.

- The break in the script: How did Partition affect the film industry?’ by Karan Bali, Hindustan Times, updated on August 14, 2016.

- ‘Revisiting 1947 through Popular Cinema: A Comparative Study of India and Pakistan’, author(s): Gita Viswanath and Salma Malik, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 44, No. 36 (September 5-11, 2009).

- ‘What Pakistan’s film industry lost in 1971’ by Asif Noorani, December 15, 2016, DAWN.

- ‘New-wave of Pakistani cinema: Zinda and kicking’ by Nadeem F. Paracha, September 26, 2013, DAWN.

- ‘A Return to Cinema’ by Ahmer Naqvi.

Rumana Husain

Rumana Husain is a writer, artist and educator. She is the author of two coffee-table books on Karachi, and has authored and illustrated over 80 children’s books. Four of her books have won awards in Pakistan, Nepal and India. She has been a contributor to various newspapers and magazines, and written hundreds of articles, travelogues, art and book reviews, and has also conducted numerous interviews in the print and electronic media.

There are no comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related Post

Understanding Installation Art

Understanding Installation Art Author: Sangeeta Thapa Originally published in NuktaArt, Vol 1, Two, October 2006 Cover Design: Sabiha…

The Virtuosity of ‘Visual Zikr’

Erving Goffman, the venerated Canadian sociologist, is renowned for his profound insights into human interaction through his dramaturgical…

Start typing and press Enter to search

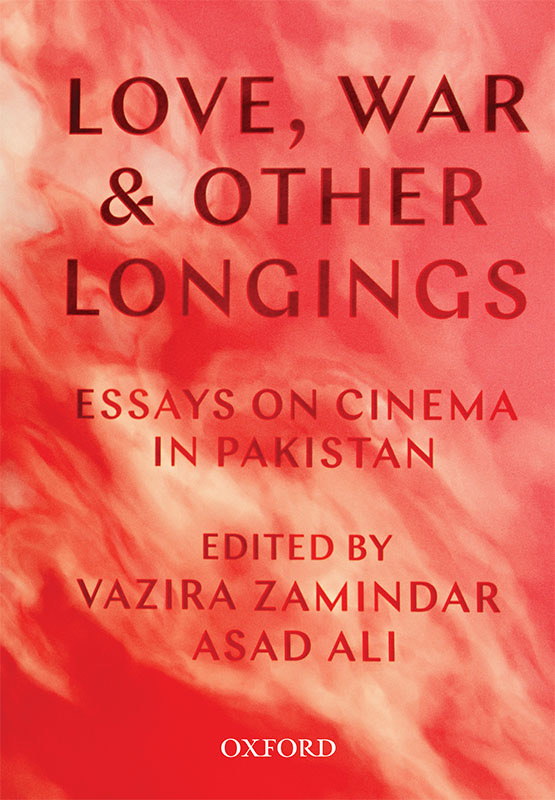

Love, War And Other Longings: Essays On Cinema In Pakistan

- Features , Film , Books

The authors in this publication boldly take on various hidden nuances in film from Pakistan – they address the use of nationalistic propaganda via film for example in Waar, as well as the financial difficulties filmmakers and production houses face while producing films

UK To Bar Entry To 'Hate Preachers' From Pakistan, Afghanistan And Other Countries

Zahra Khan is a curator of contemporary South Asian art. She is the Creative Director of Foundation Art Divvy, an art and culture foundation that supports contemporary art and independent film from South Asia. Amongst other projects, it curated the first Pakistani pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2019

Subscribe Newsletter

Facebook comments, related news, shahid jalal's journey from corporate life to artistic mastery, pakistani and other foreign students were targeted by xenophobic ..., debates and superstars at quetta's own pakistan literature festival, a tribute to shaheed zulfiqar ali bhutto, amid israel's onslaught on gaza, the threat of war with iran remains, a trend-setting book on welfare and political economy, in pakistan's ..., elections 2024: militablishment should accept defeat, reform is a political process. unelected elites and technocrats will ..., nawaz sharif will return to imran khan's pakistan, with fractured civil society & complicit politicians, there's little ..., a coup that failed, fact-check: is govt considering taxes for solar panel users, did the punjab govt buy 2 air ambulances.

- Tahir Imran Mian

Fact-Check: Did Nawaz Win Or Lose NA-15?

Fact-check: did caretaker info minister murtaza solangi meet with mqm ..., fact-check: has miftah ismail joined pti, government apathy is leading to heritage sites disappearing in both ....

- Shahzad Naveed

PK8303: How Sky Cowboys Brought Doom To 100 Passengers And Crew

Is modi’s india fated.

- Mohammed Anas

How The Right Came To Power Through The Struggles Of The Left

- Nadeem Farooq Paracha

Understanding The Protest Movement In Azad Jammu & Kashmir

- Dr Danish Khan

Climate Crisis

Heatwave to persist in punjab till may 27: pdma, gwadar: a sinking city.

- Javed Baloch

Climate Emergency Is Health Emergency, UK Veteran Doctor Says

Temperature to soar up to 46°c in several areas of karachi, ensuring climate resilience in pakistan.

- Aiyza Javaid

Follow Us On Twitter

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish with Screen?

- About Screen

- Screen at the University of Glasgow

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Explorations into Pakistani cinema: introduction

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Ali Nobil Ahmad, Explorations into Pakistani cinema: introduction, Screen , Volume 57, Issue 4, Winter 2016, Pages 468–479, https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjw053

- Permissions Icon Permissions

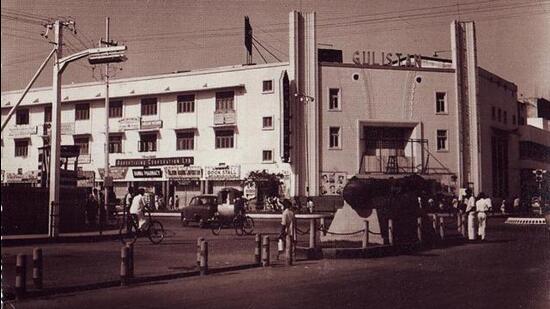

Friday 21 September 2012 in Pakistan was officially designated ‘Youm-e Ishq-e Rasool’, a national ‘Day of Love for the Prophet’, marking the country’s formal participation in a wave of angry protests that swept the Muslim world in response to the uploading of an ‘anti-Islamic’ film clip on YouTube. Amidst the globally televised demonstrations that ensued, nine of Karachi and Peshawar’s most cherished cinema halls were vandalized by rioters. Despite the dramatic spectacle of these attacks, which drew global attention to the apparently abysmal plight of cinema in Pakistan, their impact was minor in comparison with an older and deeper structural assault on traditional film-viewing venues. These have virtually disappeared since the 1990s, largely due to their conversion into shopping malls on prime sites of urban real estate. 1 Dwindling supply and demand for locally made films has reinforced this downward spiral, with production plummeting from well over a hundred films per year between the 1960s and 1980s to less than twenty at recent points in the new millennium. 2

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2474

- Print ISSN 0036-9543

- Copyright © 2024 University of Glasgow

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Subscribe Now! Get features like

- Latest News

- Entertainment

- Real Estate

- KKR vs SRH Live Score

- Election News Live

- My First Vote

- IPL Match Today

- IPL Final Live

- IPL Purple Cap

- IPL Orange Cap

- The Interview

- IPL Points Table

- Web Stories

- Virat Kohli

- Mumbai News

- Bengaluru News

- Daily Digest

- Election Schedule 2024

Review: Love, War and Other Longings; Essays on Cinema in Pakistan

A collection of essays on cinema in pakistan edited by vazira zamindar and asad ali includes pieces on its troubled history, its iconic cinema halls, and the impact of the blockbuster maula jatt.

One of my most memorable cinematic experiences came early in life when, as a seven year old, I first visited a drive-in cinema in Karachi. My cousins there, not very well off, hired taxis and cars and took us to one more than once. The magic of a giant screen in open air, of families sitting in cars enjoying a picnic while watching a film, alongside its beaches and joyrides at Clifton, made Karachi a particularly unforgettable experience. I remember that one of those films starred Nadeem and Shabnam, who, along with Mohammed Ali and Zeba, were the star pair that then dominated the Pakistani film industry. My other memory of Pakistani films is an afternoon at Oxford 25 years ago where a bunch of us Indians and Pakistanis watched Sholay and Maula Jatt back to back, courtesy Osama Siddique, now a famous Lahori writer, and had many laughs together. The recent humongous success of the Fawad Khan-starrer Maula Jatt redux seems to be Sultan Rahi’s (the star of the original film made in 1979) revenge against us for laughing at him that afternoon. Further, before I get to the book, here is another conundrum. We are all fans of Pakistani television serials, which became familiar to us with the arrival of the VHS and which brought Dhoop Kinare and Tanhaiyan , along with Moin Akhtar and Umar Sharif to our homes. Their continuing popularity even recently impelled Zee, one of India’s largest networks, to dedicate an entire channel to them. So why does a people who so excel in television, and generate such progressive content, consistently fail in cinema? Or do they? 2022 was a great year for Pakistani cinema. Apart from the worldwide success of The Legend of Maula Jatt , another film won an award at Cannes, an unprecedented feat. The recent revival of the Pakistani film industry, as well as its changing fortunes down the decades is the subject of this marvellous collection of essays which emerged out of two film festivals at the Universities of Harvard and Brown in the US.

Yes, there was once a thriving culture of making and watching films in Pakistan. At its height in the 1960s and 1970s there were more than a thousand cinema halls in Pakistan, and hundreds of films were produced every year, mostly in Urdu, which rather resembled the socials produced in Bombay, an industry which has, understandably, ever haunted Pakistani cinema. Until 1947, Lahore was one of the major centres of film production in India and Manto, who forms the subject of an incisive essay by niece Ayesha Jalal in this collection, has written about his struggles there after he migrated to Pakistan. Much of the Bombay film industry was and remains dominated by people of Pakistani Punjabi origin, including the triumvirate of Dilip-Dev-Raj, the Kapoors of several hues, the Chopras, the Sagars et al . Indian films found a steady release in Pakistan until the 1965 war. The ban imposed thereafter further propelled the Pakistani film industry.

This highly readable collection comprises many different kinds of essays. One of the editors Vazira Zamindar, is the author of an outstanding monograph on Partition ( http://cup.columbia.edu/book/the-long-partition-and-the-making-of-modern-south-asia/9780231138475 ) and took the lead in organising the festivals that produced this volume. She contributes two wonderful essays including one on an incredible one-man film archive run by Guddu Khan in his bare two rooms in Karachi. This is a rather different effort from another one man archive on music which is globally celebrated – the much more resourceful one put together by Lutfullah Khan in Karachi too. Iftikhar Dadi, one of the founders of Karachi pop and a highly distinguished artist and art historian who has lectured extensively in India, writes about the aesthetics of Pakistani cinema and its interactions with art and the cinematic limitations of its TV industry, despite its progressivism. The journalist Fahad Naveed puts together a poignant photo essay about cinema halls. There is a delightful photo essay by Bani Abidi, one of the pioneers of video art in Pakistan, about the burnt reels of Nishat cinema after it was attacked by a mob. In a brilliant essay on death and hauntings and rebirths, Meenu Gaur – one of the great anomalies of subcontinental cinema, a Calcutta born, Delhi trained filmmaker who makes breakthrough films set in Pakistan – and Asad Ali write about the contradictions surrounding Maula Jatt , which ran continuously for 216 weeks until martial law authorities took it down.

In their introduction the editors spell out the conventional periodization of Pakistani cinema as follows:

“one can speak of (a) Karachi and the Urdu Social until the mid-1970s, (b) the emergence of Lollywood from roughly the mid-1970s to the late 1990s, and (c) a new constellation once again centred on Karachi, from roughly 2013 onwards.”

It turns out that the cult status of Maula Jatt marks a cleavage between two Karachi-dominated epochs. The original Maula Jatt was released in 1978 and the story of its success and how its producer fought the censors is the centrepiece of this history. Sultan Rahi, its protagonist, became a one-man industry and spawned two decades of violence and revenge-based films that were too risqué for the middle classes who abandoned the cinema. Sultan Rahi’s angry young man persona brought a new kind of angst and irreverence to the screen, in common with the rise of the anti-hero around the world in that decade. The rise of the Punjabi film industry and Lahore’s dominance coincided with the Zia years and its intense censorship when cinema became an object of condemnation and censure. The authorities tried to ban Maula Jatt but they were too late.

“The story in which the hero, Maula Jatt, delivers justice to the doorstep of the poor had already become the stuff of legends. Nearly 25 years later, the imagery of Maula Jatt remains deeply engraved in Pakistani pop culture iconography. The film is also well-remembered for setting a trend in movie making that would not entice the urban, educated audiences. A sea of films would copy its blueprint for decades, and as Pakistani cinema became violent, alienating skilled talent and regular family audiences, so did Pakistani society. Quality declined, and so did the Pakistani film industry.”

A year after we watched Maula Jatt at Oxford, Sultan Rahi was assassinated for reasons that still remain unknown. Official news reports claim it was a robbery; others believe the cause to have been a land dispute; yet others believe he was killed by religious bigots because of his imminent plans to reconvert to the religion of his birth, ie Christianity.

“This sudden death also more or less coincided with another untimely death, that of the Pakistani film industry itself. While several factors were responsible for the decline of the industry — including the creation of Bangladesh and the consequent loss of film personnel and market territory, the military dictatorship of General Zia and its oppressive censorship policies, and the proliferation of VHS — Sultan Rahi’s passing most definitely heralded the end of an era, after which Lollywood more or less struggled with its own extinction.”

Yet, Pakistani cinema also has an ideological battle to fight for legitimacy, a battle that cinema in India had appeared to conquer before recent ideological assaults on Bollywood. In 2012, a series of attacks by rioters resulted in six cinemas being burnt in Karachi and Peshawar. Ali Nobil Ahmad, one of its foremost scholars of cinema has gone so far as to call Pakistan “one of most cinephobic nations on earth.” Discussing the classic text Pakistan Cinema 1947–1997 by Mushtaq Gazdar, Ahmed argues that this disowning of Lollywood (the Lahore-based film industry) and its culture by the state and society is not a result of the Islamization of the Zia years, but was, in fact, the official position of the early Pakistani state, which viewed cinema as “sinful”. As a cinema owner states, “Our biggest misfortune is that we Pakistanis are making films in a country in which watching films is seen as a crime. People ask us why our industry is not prospering, and I always tell them that this industry cannot prosper until film and filmmakers are given their due respect. A nation that addresses its musicians as marasi , film personnel as kanjar , and film heroines as gashti (ie prostitute) — how can the industry of that country prosper?”

While there was a steady decline in the number of films being produced annually from 1989 onwards, it became especially acute after 2003, when, despite 50 films being released, there were fewer blockbusters. The slump continued until it reached a production low of 23 films in 2012, which coincidentally was the year when religio-political protestors attacked and burned five cinemas in Karachi. Hence 2012 is widely perceived as the nadir for film in Pakistan. As many have noted, the following year marked a revival in both the number of productions (up to 37) and box office success. What is notable, especially since 2015, is the decline in the number of Punjabi films, and the increasing production and dominance of Urdu. Karachi has once again emerged as the capital of the Pakistani film industry where television giants such as Geo, Hum and ARY are based and it is the talent and financial muscle of its TV industry that is now helping revive its cinema. This revival is also linked to the decision by General Parvez Musharraf to re-allow the screening of Indian films and the liberalisation of the TV industry that he promoted. One of the early outcomes of this was Khuda Kay Liye , a film which enjoyed great success upon this theatrical release in India. Another recent success was Zinda Bhag , directed by Meenu Gaur mentioned above, which Iftikhar Dadi discusses in detail in this book. In 2015, a war film actually called Waar reversed the conventional Bollywood gaze and projected India as a terrorist disrupter in Pakistan and enjoyed huge success. Its Director Bilal Lashari went on to remake Maula Jatt starring Fawad Khan which has, once again, become the greatest hit of Pakistani cinema. Further, Joyland by Karachi-based Saim Sadiq became the first Pakistani film to win the Jury Prize of the Un Certain Regard section at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival.

The conventional view in Pakistan laments the decline of bourgeois national Urdu cinema’s golden age, which was eclipsed by the dark age of bawdy and violent Punjabi cinema. This also resulted in a shift in audiences from the urban middle classes to the working class, until the last decade when new multiplexes and new policies — such as not allowing stags to enter alone — has resulted in a new gentrification. Yet, as Faiz’ granddaughter Mira Hashmi remembers here, the experience of single screen cinema halls remains unparalleled. She refers to the cinema of the time — that is, of the late 1970s and early 1980s — as the “great leveller”. English speaking upper-middle-class people, rickshaw drivers, factory workers, all would see the same film in the same hall, “pay the same amount of money for the same snacks, and immerse themselves in the same cultural conversations.” It was the same in India too, until the 1980s, a decade that comes in for universal flak here. Yet, the cinema of that time depicted the poor and their lack of faith in the system, and was watched by the poor. At the same time, as the poor and the working classes disappeared from the screen — one would be hard pressed to remember a working class hero in any film thereafter — they also simultaneously disappeared from the cinema halls in India. Both became more purely bourgeois. And still, if one were to compile a list of the best Indian films of the 1980s, it is possible that it might remain unsurpassed by all the best films made in India in the subsequent three decades. Just off the cuff let me start listing, outside of the parallel cinema, Masoom, Ijazat, Mr India, Parinda, Karz, Sadma, Khoobsurat, Bazar, Naram Garam, Umrao Jaan, Saransh, and I am not even mentioning some of the great Amitabh Bachhcan hits such as Namak Halal, Yarana, Aakhri Rasta or the arthouse films such as Katha, Chasme Buddoor, Ardh Satya, Saleem Langde Pe Mat Ro, Sparsh and innumerable others. The range and quality of these films has remained unsurpassed in my opinion.

While cinema remains popular it has begun to see huge dents from digital platforms and is no longer the mass phenomenon that it once was in South Asia. Still, the revival of the Pakistani film industry, and conversations around it alert us not just to the commonalities we share but also that our post-colonial trajectories, despite our different political experiences, may not be so dissimilar after all. One must remember that the entitled bourgeoisie in all of South Asia aspire to and consider themselves to be organically linked to the universal Enlightenment values of Europe, and, in fact, it is Maula Jatt who challenges this hegemony.

Mahmood Farooqui is best known for reviving Dastangoi, the lost Art of Urdu storytelling.

Join Hindustan Times

Create free account and unlock exciting features like.

- Terms of use

- Privacy policy

- Weather Today

- HT Newsletters

- Subscription

- Print Ad Rates

- Code of Ethics

- IPL Live Score

- T20 World Cup Schedule

- IPL 2024 Auctions

- T20 World Cup 2024

- Cricket Teams

- Cricket Players

- ICC Rankings

- Cricket Schedule

- T20 World Cup Points Table

- Other Cities

- Income Tax Calculator

- Budget 2024

- Petrol Prices

- Diesel Prices

- Silver Rate

- Relationships

- Art and Culture

- Taylor Swift: A Primer

- Telugu Cinema

- Tamil Cinema

- Board Exams

- Exam Results

- Competitive Exams

- BBA Colleges

- Engineering Colleges

- Medical Colleges

- BCA Colleges

- Medical Exams

- Engineering Exams

- Horoscope 2024

- Festive Calendar 2024

- Compatibility Calculator

- The Economist Articles

- Lok Sabha Election Live

- Delhi Election 2024 Live

- Odisha Election 2024 Live

- Lok Sabha States

- Lok Sabha Parties

- Lok Sabha Candidates

- Explainer Video

- On The Record

- Vikram Chandra Daily Wrap

- EPL 2023-24

- ISL 2023-24

- Asian Games 2023

- Public Health

- Economic Policy

- International Affairs

- Climate Change

- Gender Equality

- future tech

- Daily Sudoku

- Daily Crossword

- Daily Word Jumble

- HT Friday Finance

- Explore Hindustan Times

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Subscription - Terms of Use

- EXPRESS NEWS

- URDU E-PAPER

- ENGLISH E-PAPER

- SINDHI E-PAPER

- CRICKET PAKISTAN

- EXPRESS LIVE

- CAMPUS GURU

- EXPRESS ENTERTAINMENT

- FOOD TRIBUNE

Pakistan demands Afghanistan to hand over TTP terrorists involved in Besham attack

Interior minister asks Afghan interim govt to act against terror network on its soil

Gandapur, Centre to ‘jointly address’ K-P power woes

55% of govt scheme pilgrims in Saudi Arabia

Panic in Bishkek

City under siege

Doctors ‘arm-twisted’ into discharging PTI’s Yasmin Rashid

PM lauds Norway’s landmark decision to recognise Palestine

Loss of Raisi, Abdollahian truly tragic and irreparable: COAS

Hamas fires missiles at Tel Aviv, prompting first sirens in months

Army officer, soldier martyred in Peshawar IBO: ISPR

Kuwait, Qatar emirs to visit Pakistan on PM’s invite

FIR registered against 400 suspects in connection with Sargodha violence

Police have arrested over 28 individuals in connection with the mob violence so far

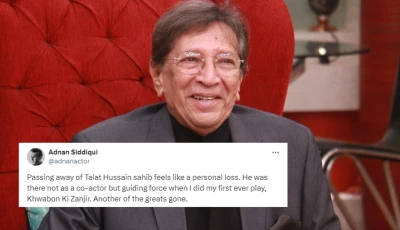

Talat Hussain, celebrated Pakistani actor, passes away at 83

Veteran star breathed his last in Karachi after prolonged illness

Cyclone hits Bangladesh as nearly a million flee inland for shelter

Experts recorded maximum wind speeds of 90 kilometres from the severe Cyclone Remal so far

1716728587-0/Papua-New-Guinea-landslide-(2)1716728587-0-196x127.webp)

More than 670 feared dead in Papua New Guinea landslide

Only five bodies retrieved from rubble so far, remoteness and tough terrain are slowing rescue and aid efforts

55% of capacity of major sectors couldn’t be traced

It leads to evasion of income tax, sales tax and federal excise duty

Experts back soilless crop growing technique

In hydroponics, crops can be produced in any season with less input, output

Deep reforms agenda proposed

PIDE for dismantling outdated institutions that hinder research, tech advancement

Pakistani rupee beats Asian peers

Declared best performing currency in region as RDA inflows surge beyond $8b

PSX cheers IMF loan, UAE investment

KSE-100 index jumps 641 points, or 0.85% WoW, settles at 75,983.04

LIFE & STYLE

Another of the greats gone: Tributes pour in as Pakistan bids farewell to acting titan Talat Hussain

Icon passed away at 83 on Sunday in Karachi after prolonged illness

Remembering Talat Hussain: Five performances that left a mark

Veteran actor passed away at the age of 83 in Karachi

‘Anora’, a raucous comedy about an exotic dancer, wins Cannes top prize

Sean Baker directorial beat 21 other films, including Francis Ford Coppola’s ‘Megalopolis’, to clinch Palme d'Or

Five times Nancy Tyagi recreated celebrity looks to perfection

From Alia Bhatt to Taylor Swift, these fashion icons inspired some of the best work by the Indian influencer

Decision would send strong message of hope and solidarity to brave Palestinian people, says Shehbaz

Lawyer claims neither legal counsel nor family permitted to visit hospital

GPS system being used for first time to track Pakistanis going from Madinah to Makkah

Tarar condemns PTI’s ‘malicious’ SIFC attack

SIFC, economy are Pakistan’s lifeline, minister tells party

Safe City Project launched in Dasu, Chilas to protect foreign nationals

Committee formed, directed to submit its final recommendations within 15 days

Gen Munir expresses deep condolences over sad and unfortunate incident of helicopter crash on May 19

PTI MPA-led protesters storm Peshawar grid station

Demonstrators turn on feeders; PESCO seeks FIR against lawmaker

The final 15

Regulating AI

UAE’s largesse

Poverty in Pakistan

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall

New ‘axis of evil’ and Global North

Skincare 101

The Home Edit

7 Wardrobe Colour Schemes to Embrace This Spring

Israeli military say eight projectiles were identified crossing from the area of Rafah

Twelve injured as Qatar Airways Dublin flight hits turbulence

The turbulence incident lasted less than 20 seconds and occurred during food and drinks service

US expected to lift ban on sale of offensive weapons to Saudi Arabia, FT reports

Saudi Arabia, the biggest US arms customer, has chafed under those restrictions from previous US administrations

Fire at entertainment venue kills at least 24 people in western India

With rescue efforts continuing in Rajkot district of Gujarat province, local mayor says death toll is expected to rise

Fire kills six newborns at baby hospital in India's capital

Fire department says six more children were rescued and taken to a different hospital, with one on a ventilator

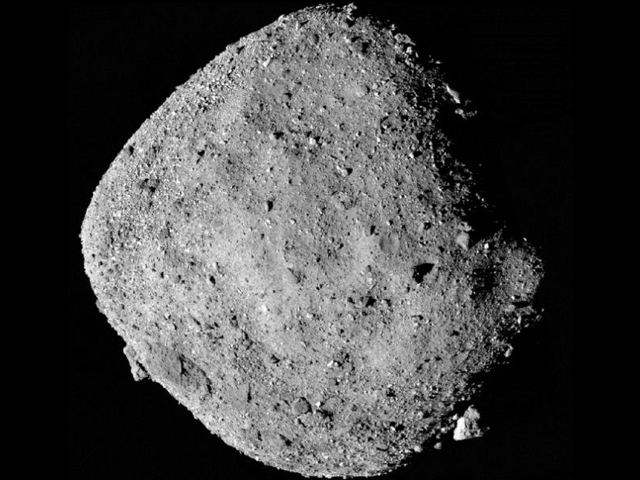

Astronomers develop new observation technique to mitigate asteroid risks

The new rotating-drift-scan (RDS) charge-coupled device (CCD) technique, allows asteroid as a point source

Tesla's ‘milestone’ Shanghai battery factory breaks ground

Mass production is set to start in Q1 2025, with an initial capacity of 10,000 Megapack units annually

Elon Musk plans xAI supercomputer, The Information reports

The supercomputer will power the next version of AI chatbot Grok in late 2025

Chinese scientists 'successfully' undertake world's 1st liver xenotransplantation surgery for human

7 days after surgery, 71-year-old patient can move freely without acute or hyperacute rejection reactions

NASA, Boeing clear two technical hurdles for Starliner's debut crew flight

Starliner's first crewed flight is final test mission before NASA can certify spacecraft for routine astronaut trips

1st PNSC Inter-Provincial Women Softball Championship kits unveiled

The event is a great opportunity for softball players to make it to the international level, Ronak Lakhani

Ruud dreams of French Open title

World number seven beat 44th-ranked Czech 7-5, 6-3 in Saturday's final to add to Geneva trophies won in 2021 and 2022

Marchand continues Olympic build-up with 100 fly win in California

Five-time world champion secured the 100m butterfly title with a time of 52.56 seconds

Osaka, Alcaraz bring curtain up on French Open

Japanese star meets Italy's Lucia Bronzetti, while Alcaraz faces J.J. Wolf

PSG win French Cup final on Mbappe's farewell appearance

Goals from Ousmane Dembele and Fabian Ruiz led the team to 2-1 victory against Lyon

ENTERTAINMENT

Bethenny Frankel furious over denied entry to Chanel

Returns in designer attire and gains access.

Bradley Cooper joins Pearl Jam for surprise performance at BottleRock

Bradley Cooper joined Pearl Jam onstage at BottleRock for a surprise acoustic duet of "Maybe It's Time".

Princess Charlene poses with twins before joining Prince Albert at Monaco Grand Prix

Princess Charlene celebrated Mother's Day with her twins before joining Prince Albert at the Monaco Grand Prix

George Floyd biopic titled "Daddy Changed the World" is officially in the works

George Floyd biopic "Daddy Changed the World" with his daughter's involvement aims to explore his life and legacy.

Elsa Hosk stuns in double dose of retro glamor at Cannes film festival

Elsa Hosk wows Cannes in retro glam: Marilyn Monroe vibes in Prabal Gurung & Saint Laurent halter.

AI: A friend or a foe?

For Pakistan, this power, if harnessed responsibly, could be a game-changer; but it can also be a missed opportunity.

Punjab: Revolutionising healthcare and youth engagement

The Punjab govt, under CM Maryam, is investing heavily in the healthcare sector across 36 districts of the province.

Combatting agricultural fraud

This alarming trend not only undermines the economic sustainability of farming but also exacerbates food insecurity.

DHA and JBS partner to equip students with cutting-edge tech skills for future career

With this program, students are well prepared to cope with the ever-changing digital landscape

RECENT BLOGS

Updated May 22, 2024

Updated May 20, 2024

Punjab's plastic ban: A commendable step for the future

This is not just about banning plastic bags; it is about fostering a culture of responsibility and sustainability.

The future of Pak-Iran relations after Ebrahim Raisi

The death of Ebrahim Raisi injects a substantial degree of uncertainty into the future of Pakistan-Iran relations.

IMF's tax demands leave PM in a bind

Updated May 25, 2024

No dice with foreign lenders unless all exemptions are axed first, PM briefed

Poverty is costing the country on socioeconomic, political, technological and developmental fronts

By calling ISI official, IHC judges making a point

Usually superior courts avoid summoning serving military officers

Western media calls Russia-China visit a part of ‘a partnership against the West’

Pakistan seeks $17b from China

Proposes ambitious plans to expand CPEC, requests funding for nine key projects

Updated 14 hours ago

Gandapur-COAS interaction limited to pleasantries

Updated 22 hours ago

K-P CM says Imran open to negotiation for country’s sake

Malik Riaz says under immense pressure, 'will not allow anyone to use me as pawn'

Updated 16 hours ago

I've been punished for contributing towards the progress of the country, says Bahria Town chairman

Police thwart another Jaranwala-like tragedy

Cops rescue Christian man in Sargodha before mob lynches him over allegation of blasphemy

Pakistani students who returned from Kyrgyzstan share harrowing stories of the mob violence they faced last week

Former Sindh governor decides to return home

To take active part in national politics without any pressure

Missing Algerian man found alive from neighbour's cellar after 26 years

Missing since 1998, now 45 years old Omar B was found being held by neighbour 200 metres away from home

Miftah takes a dig at Imran for his anti-establishment narrative

Former finance minister says given the signal, PTI founder would align with the establishment again

Sindh vows to provide up to 100 units of free electricity

Updated May 24, 2024

Will leave country, but won’t become slaves to establishment: Fazl

JUI-F chief announces initiation of nationwide movement, with a public rally scheduled for June 1 in Muzaffargarh

Third ‘Congo virus’ case reported in Attock

Authorities confirm presence of virus in first two patients after their deaths

6 NATO countries to create ‘drone wall’ for border protection: media

Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, as well as Poland, Finland, and Norway, will join initiative

E-Publications

Khurram Manzoor Predicted 4 Semi Finalist Of T20 World Cup 2024 | Pakistan News

Pakistani Spent Millions Of Dollars On Tea | Kosmopolitan | Pakistan News

Dost Ki Biwi Say Chakar - Jan Le Gaya | Pakistan News | Express News

PTI take Big decision | News Headlines 3 AM | Pakistan News | Latest News

Mirza Akhtiyar Baig Gives Big News regrading Car Manufacturers in Pakistan | KosmoPolitan

Pakistan Sab Sy Dil kash Mohalla Sethiya Ki Tareekh | Mustansar Hussain Tarrar | Pakistan News

Saim Ayub Ki Chutti Babar Azam bhe Mushkil Mein !Khurram Manzoor Bari Khabar Le Aye| Pakistan News

Jail Janay Ka Shauq Mehnga Par Gaya | Sansi Khez Dastan | Pakistan News

PM big announcement | News Headlines 1 AM | Pakistan News | Latest News

How China Beat Pakistan in Car Manufacturers ? | Syed Nabeel Hussain reveals | KosmoPolitan

- Life & Style

- Prayer Timing Pakistan

- Weather Forecast Pakistan

- Online Advertising

- Subscribe to the Paper

- Style Guide

- Privacy Policy

- Code of ethics

This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, redistributed or derived from. Unless otherwise stated, all content is copyrighted © 2024 The Express Tribune.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

EFFECTS OF GLOBALIZATION ON THE PAKISTANI FILM INDUSTRY

Related Papers

Abdalla Uba Adamu

Communication, Culture & Critique

Azmat Rasul

Elvin Amerigo Valerio

In the last ten years – as Hollywood movies continue to dominate the Philippine cultural landscape and the output of the Filipino mainstream movie industry continues to decline – the Philippines has seen a surge of films produced by so-called " indie " or independent filmmakers. Unfortunately, while independent films are popular among a few upper and middle class audiences, it has yet to create a major impact on the wider movie-going public. As a result, independent filmmakers bring their works to international film festivals, mostly in Europe and the United States. Questions arise as to whether these filmmakers create films that cater more to Western tastes than to that of Filipinos. This paper argues that independent films can also be used as an " alternative " to counter the global hegemonic dominance of Western cinema, particularly those of Hollywood. It adopts as its primary framework the post-colonial theories of Renato Constantino and Bienvenido L. Lumbera. The essay proposes two questions that can serve as a guide for Filipino filmmakers: (a) Cinema for whom? (b) How can cinema serve the Filipino masses? It further suggests that Filipino filmmakers can make use of movie genres already embraced by the masses, subtly subverting and re-inventing its form in order to address the Filipinos' " colonial mentality " brought about by decades of U.S. cultural imperialism and neo-colonialism. In other words, filmmakers can foster counter-hegemonic ideas under the guise of the popular melodrama, comedy or fantasy genre; hence creating a truly Filipino alternative cinema.

Mudassir Mukhtar

As the nexus between film industry and state apparatus has grown critical and complex in the wake of war on terror, academic circle have paid attention to identify the patterns of relationship between entertainment industry of a country and its foreign policy. To understand the role of the soft power in assisting governments to secure their interests at international level, this article examines the relationship between Bollywood and the Indian foreign policy through the lens of critical political economy of communication approach. Popular films portraying tension and cooperation between the South Asian neighbors were critically analyzed, and the results indicated that Bollywood closely followed the foreign policy initiative of the Indian government. Keywords: Bollywood; media and foreign policy; political economy of communication; entertainment industry; South Asia

Jigna Desai

Chronicle: A Journal of Technology, Design, and Culture

Throughout most of the 20th century, the dominance of Hollywood hindered the development of a distinct film identity and tradition within Philippine cinema. However, from this seemingly uninspiring state, a vibrant independent film community emerged and thrived during the first decade of the 21st century. This transformation was made possible by the introduction of more accessible digital video cameras in the 1990s. The digital medium provided independent filmmakers with the opportunity to explore various storytelling approaches centered around Philippine realities, which resonated with younger audiences. This paper posits that Filipino independent, or “indie,” cinema experienced a surge in creativity during the first decade of the 21st century and established what I refer to as a “postcolonial aesthetic” to counter the dominance of the Hollywood cinematic structure. I draw upon the ideas of Renato Constantino and Bienvenido Lumbera as my primary framework to trace the trajectory of independent and mainstream Filipino cinema during this period. Through an examination of two films from that era—one independent (Ded na si Lolo [Grandpa is Dead], 2009) and one mainstream (Baler, 2008)—I argue that Philippine cinema truly came into its own between 2000 and 2010, and its unique characteristics continue to influence the post-Covid era.

Sangjoon Lee

This dissertation explores the ways in which postwar East Asian cinema was shaped by the practice of transnational collaborations and competitions between newly independent and still existing colonial states at the height of Cold War cultural politics. More specifically, my aim is to elucidate the extent to which postwar film studios aspired to rationalize and industrialize the system of mass-production by way of co-producing, expanding the market, and co-hosting film festivals. I argue that the emergence of these motion picture studios was the offspring of the Cold War and American hegemony. While providing financial aids to film industries and supporting the cultural elite, U.S. agencies helped to initiate the first postwar inter-Asian film studio network. It is a new attempt to reconstruct East Asian film history. By unveiling these cinematic links, the previously unquestioned history of quintessential national cinema is reassessed. I claim that the concept of national cinema is a fictional construct precariously built upon the denial of the regional cinematic sphere.

Elisa Costa-Villaverde

IBA Business Review

Dr Erum Hafeez

This study aims to examine and analyze role of motion pictures as an agent of socialization. It focuses the contribution of Indian movies to the increase of violent crimes and criminals in Pakistani society across the four decades (i.e. 1970s, 1980s, 1990s and 2000s) through favorable rather glamorized depiction of violence and perpetrators of violence. It is arbitrarily assumed that violence is often projected on silver screen as a quick and easy solution to social injustice and class discrimination in the blockbusters of Bollywood and Lollywood. Five top grossing Indian films selected through popularity charts and youth polls are thus content analyzed from the four decades under study for the census and portrayal of both perpetrators and subjects of violence, following sampling techniques of Shipley and Cavendar, 2001. Subsequently, four samples of one month issues of the largest circulated Daily Jang __ from each decade (1976-2006) __ were carefully content analyzed to identify the population, age, gender, class and depiction of criminals and victims as a representative day-to-day record of social crime scene.

Faryal Jogezai

Film and Cinema are a vast producer of art and aesthetics. The world cinema displays cultural diversity and creativity through film and cinema. The term globalization helps us explore the world cinema as well as compare them. This paper looks at a comparative analysis of East Asian cinema and Hollywood. The paper consists of a brief introduction, objective of the study and literature review through the perspective of aestheticism in both cinemas. Relevant research studies and movie comparison is offering an insight to which cinema is more aesthetically strong and dominant. The paper also offers the limitations of the study along with considering the potential for future research on this topic. Keywords: Film Studies, Film Aesthetics, Hollywood, East Asian Cinema

RELATED PAPERS

Stephen Teo

Media in the Middle East: Activism, Politics, and Culture

Dale Hudson

deborah shaw

Critical Studies in Media Communication

Indian Media: Global Approaches

adrian athique

andrew alibbi

Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies

Dolores Tierney

Asian Cinema

Lori Morimoto

Chanda Kapemba

Adam Muller, ed., Concepts of Culture: Art, Politics, and Society (Calgary: U of Calgary Press), 2005

Martin Roberts

Tanner Mirrlees

Horizons in Humanities and Social Sciences

Doris Hambuch

Mark Lorenzen

The Journal of Political Science

Sanwal Kharl

Mediated Geographies and Geographies of Media

Michael Curtin , Chris Lukinbeal

Dolores Tierney , Ana Lopez

International Journal of English Studies

International Journal of English Studies (IJES) , Elena Oliete

International Journal of Media and Cultural Politics

Diana Coryat, Ph.D. , noah zweig

Shilpakala Annual Journal 2014

Fahmida Akhter

Kaia Shivers

Patricia White

Bweseh Shitta

Karl Schoonover , Rosalind Galt

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences

Tesfaye Bezabih

Gustavo Herrera Taboada

BioScope: South Asian Screen Studies

A Companion to the Horror Film

Alessandro Jedlowski

Dale W Russell

Korea Journal

Munib Rezaie

kevin robins

Vicente Rodríguez Ortega

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

The many stories of cinema and cinephilia in Pakistan

In the area of South Asian film studies, Pakistani cinema has rarely been the subject of focused and dedicated scholarship. As such, Mushtaq Gazdar’s Pakistan Cinema 1947-1997 has remained the only historical study of Pakistani cinema, its disputed origins, and its evolution from the creation of Pakistan in 1947 until the late 20 th century. In what has since become a seminal text, Gazdar imagines and constructs the category of ‘Pakistani cinema’ along linguistic and nationalistic axes, a history which has since been debated and contested by a series of publications on Pakistani film history in the past decade. With the publication of Ali Nobil Ahmad and Ali Khan’s Cinema and Society and Ahmad’s dossier on Pakistani cinema for Screen in 2016, there has been a renewed scholarly interest in Pakistani film cultures, and in the fundamental question of the limits of a Pakistani national cinema. Recent scholarship on Pakistani cinema, therefore, has been preoccupied with questions of film historiography and with thinking beyond the national cinema model which informed Gazdar’s work.

It is within these debates of film historiography and national film cultures that Ali Nobil Ahmad and Ali Khan’s recent volume Film and Cinephilia: Beyond Life and Death (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2020) situates itself. Compared to their previous volume, [1] Film and Cinephilia is a more focused endeavor in making visible alternative histories of Pakistani cinema as well as regional film cultures that were excluded from Gazdar’s history. In a similar vein, another recent publication on Pakistani cinema which offers alternative historiographical models is Vazira Zamindar and Asad Ali’s edited volume Love, War, & Other Longings: Essays on Cinema in Pakistan (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2020). This review focuses on these two volumes and explores the ways in which they each tell particular stories of cinema in Pakistan, stories that seem to be in conversation with each other about Pakistan’s cinematic pasts and its evolving present.

Film and cinephilia in Pakistan: Beyond death and revival

As noted above, recent publications on Pakistani film cultures have been in conversation with Mushtaq Gazdar’s history of Pakistani cinema and its claims about the decline of the film industry during the 1970s. Gazdar associated this decline to the strict censorship policies introduced by General Zia-ul-Haq’s military coup, as well as to technological and industrial transformations brought about by the rise of VHS and television. As a result, there was a marked decline in the number of Urdu-language films produced after Zia’s coup which, according to Gazdar, heralded the death of the Pakistani film industry. It is this account of death and decline which Ahmad and Khan attempt to re-narrativise in their volume by focusing instead on regional Punjabi and Pashto film cultures which not only survived the Zia years but also sustained cinemagoing culture in Pakistan. In doing so, their intervention lies primarily in national cinema debates and the so-called ‘national question’ (p. 3) which foregrounds studies of postcolonial cinemas.

For where Gazdar saw Pakistani cinema declining after the decrease in the number of Urdu-language films in the 1970s, there was a specific Pakistani cinema he was imagining that was Urdu and decidedly upper-middle class. Ahmad and Khan’s intervention then lies in thinking beyond Gazdar’s idea of the national, as they argue: ‘In South Asia’s multilinguistic societies, where borders of every kind are contentious and porous, it is problematic to speak of language, territory, and nationality as neatly interchangeable and overlapping entities.’ (pp. 3-4).

Film and Cinephilia thus takes the frameworks of the regional and the vernacular to think about what can possibly constitute a Pakistani cinema. Furthermore, rather than thinking of regional film cultures as disparate and discrete, Ahmad and Khan’s invitation to think transregionally and transcolonially also frames several of the contributions in the volume. In this respect, Iftikhar Dadi thinks about the linguistic fluidity and the inherent connections between Pakistani Urdu and Indian Hindi cinema, and thus offers a transnational mode of approaching the question of film history and canon formation. If Gazdar had constructed the idea of a discrete Pakistani cinema based on Urdu-language films, Dadi explores the ‘intimate connections between Pakistani “Urdu” cinema and Indian “Hindi” cinema’ (p. 25) to problematise such nationalist constructions. In a similar vein, Lotte Hoek’s two essays in the volume take a similar transcolonial and inter-regional approach in exploring the entangled histories of cinema in Pakistan and Bangladesh. In tracing ‘the long-term impact of the interactions between East and West Pakistan on the histories of cinema in Pakistan and Bangladesh’ (p. 37), Hoek is similarly preoccupied with questions of film historiography and in thinking beyond discrete national boundaries.

In conversation with Dadi and Hoek’s emphasis on historical connections, Julien Levesque and Camille Bui’s essay focuses on regional Sindhi cinema and its tenuous relationship to constructions of Pakistani nationhood in the decade immediately preceding Partition. As Pakistani cinema as a nationalist category was emerging in opposition to a mutually discrete Indian cinema, regional cinemas like Sindhi cinema built their identity in opposition to Pakistani nationalism and yet were subsumed in the expansion of Pakistani cinema (pp. 90-91). The early essays in Film and Cinephilia therefore offer alternative historical and theoretical frameworks for not simply approaching Pakistani film history but also to think about the category of Pakistani cinema itself.

As mentioned earlier, Film and Cinephilia takes the question of what has historically constituted Pakistani cinema as one of its central concerns. For this purpose, Ahmad and Khan have further included early writings on Pakistani cinema which think about the emergence of a distinct national cinema in Pakistan and what that might mean and include after Partition. In this respect, the translations of the writings of Urdu intellectuals like Saadat Hassan Manto, Muhammad Askari, and Faiz Ahmad Faiz offer insight into how the idea of cinema in Pakistan has evolved over time. Where for Manto, a Pakistani cinema had yet to emerge that had ‘a stamp of its own’ (p. 98), the question of what might be considered authentically ‘Pakistani’ has driven conversations on Pakistani film studies in the past two decades. Askari and Faiz might be less invested in the questions of national cinema, but their writings on technological advancements like the use of colour in Pakistani cinema and the culture of film criticism in Pakistan offer different entry points in thinking about the constitution of a Pakistani film culture. By bringing these early writings on Pakistani cinema in conversation with filmmaker Sabiha Sumar’s interview on contemporary debates regarding the absence of a world-class cinema in Pakistan, Film and Cinephilia offers a unique archive where past debates and contemporary discussions on Pakistani film cultures are brought in dialogue.

Considering the absence of official film archives in Pakistan, Film and Cinephilia further offers unique approaches to thinking about what archives can look like in the context of Pakistani film culture. In this respect, Ali Khan’s essay on Pakistani film poster art is at once an exercise in thinking about archival ephemera and furthermore also comments on the importance of an industry that has slowly become obsolete. In the same vein, Timothy P. A. Cooper’s essay on film circulation and unlikely archives of pirated media continues the conversation on thinking about archival practice in the context of Pakistan. Returning to Ali Khan’s essay on the labor and craft involved in the Pakistani film poster art industry, he makes prominent the issues of an industry gradually becoming obsolete. This is further echoed by Gwendolyn S. Kirk’s essay which traces the impact of digital technologies on Punjabi filmmaking and the ways in which traditional technologies are slowly becoming replaced. In this respect, both essays look at issues of craft, labor, and class politics as central to discussions of marginal film cultures and practices.

As Film and Cinephilia centers discussions of marginal film cultures and especially their relation to class politics, it would be remiss to not mention films like Yunus Malik’s Maula Jatt (1979) which found success and notoriety during General Zia’s military regime, and which have enjoyed immense cultural longevity. Maula Jatt is mentioned throughout the volume, but it is in Iqbal Sevea’s essay that it gets focused attention as Sevea explores constructions of masculinity and competing discourses of class and caste in his reading of the film. While Sevea looks at a film from the past to think about marginal film cultures, Gwendolyn S. Kirk, in her second essay for the volume, analyses the Pakistani slasher film Zibahkhana (Omar Ali Khan, 2007) in terms of its class politics and representations of Muslim identity. Both essays serve as theoretical models for analysing specific Pakistani film genres and the aesthetic conventions that have emerged in marginal Pakistani film cultures.

Overall, Film and Cinephilia is a timely intervention in the field of Pakistani film studies. The limitations of this volume are limitations that come from being one of the few scholarly publications dedicated to the theorisation of a subject still vastly under-researched. Therefore, it might be generative to approach this volume from a methodological lens and analyse whether the frameworks offered in these essays are adequate to lend themselves to the study of Pakistani film cultures, histories, and traditions excluded in the volume. However, the importance of this volume cannot be overstated for initiating conversations about a still nascent and emerging field, as Kamran Asdar Ali’s afterword further emphasises. This is also made evident in Vazira Zamindar and Asad Ali’s Love, War, and Other Longings , a volume which continues these conversations and theorisations of film historiography, archival practice, and bygone film cultures in Pakistan.

Love, War, & Other Longings : Essays on cinema in Pakistan

If Film and Cinephilia thinks about the so-called ‘death’ of Pakistani cinema and theorises beyond such historiographies, then Love, War, & Other Longings thinks about potential revivals. The revival of cinema in Pakistan in recent years begs the question of what exactly it was that had died. To think of the death or so-called revival of cinema in Pakistan then becomes a question of what has historically constituted Pakistani cinema? What does it mean to long for something that might have never died or might have never existed in the first place?

Vazira Zamindar and Asad Ali’s introduction to their edited volume begins with the question of desire, of collective loss, and of trauma. Their story of cinema in Pakistan takes the late 1990s and the early 2000s as a starting point and thinks about industrial transformations which brought about the so-called revival of film culture in the beginning of the present century. To think about Pakistani cinema’s assumed decline at the turn of the 20 th century and its revival in the age of multiplexes and digital technologies is to fundamentally think about what the category of Pakistani cinema even means, what it contains, and what such nationalist constructions exclude. Zamindar and Ali explore this important ontological question early in their introduction and yet theirs is a project less interested in defining the scope of a Pakistani cinema and more preoccupied with the representational and the affective dimensions of New Cinema in Pakistan. They write: ‘Film’s inherent capaciousness, its proliferating significations, ensures it necessarily gestures to forms of being, belonging, and politics that exceed the frame of the nation.’ (p. 11) This volume therefore is an offering to think beyond the nationalist limits and the historiographical impasses which contain film histories.

The volume consists of a compilation of nine essays, all of which take a unique approach not simply in methodological terms but also in subject matter. Fahad Naveed’s chapter, titled ‘After the Interval’, is an ethnographic study of cinema spaces in Lahore and Karachi. Naveed’s respondents, which vary from cinema operators to spectators to small business owners, ruminate on Pakistan’s transition from single-screen celluloid theatres to multiplexes in the last two decades. Many of his respondents speak of this transition in a language of nostalgia and loss (p. 29), while others mention the possibilities in newer technologies to make cinemagoing accessible and affordable for audiences and yet lucrative business for investors (pp. 38, 40). As the aim of this collection is to theorise Pakistani cinema’s turn towards the digital and the new film culture which has emerged in the past two decades, Naveed’s essay complicates a linear historical telling of Pakistan’s lost cinematic past and the recent emergence of something new. The awaami or local film culture still persists from the time of General Zia’s military coup in the late 1970s (p. 30), and so Naveed’s ethnography complicates frameworks of decline and revival.

Similarly, Meenu Gaur and Adnan Madani in their chapter ‘The Ghost in the Projector: New Pakistani Cinema & its Hauntings’ explore frameworks of decline and revival that have marked Pakistani film historiography but offer a different conceptualisation of Pakistan’s cinematic past. They theorise Pakistan’s current film culture as one haunted by the specters and ghosts of the past. If Naveed’s essay shows the persistence and survival of regional film cultures in terms of physical spaces of the awaami theatres and their audiences that have survived the difficult years of Zia’s military dictatorship, Gaur and Madani focus on the film texts, generic codes, and icons themselves that continue to haunt contemporary cinema in Pakistan today. They think through the lens of hauntology and trace the hauntings of one of Pakistan’s most important films, Maula Jatt (Yunus Malik, 1979) and the continued legacy of its star, Sultan Rahi. Released during the time of martial law, Gaur and Madani’s retrospective on Maula Jatt foregrounds the cultural impact as well as the influential role the film played in terms of heralding a new cinematic form which would become the template for Pakistani films for decades to come. In this respect, Gaur and Madani are in direct conversation with Iqbal Sevea’s essay in Film and Cinephilia where he explores the figure of the new film hero cemented by the success of Maula Jatt . Instead of frameworks of death and revival, their essay then thinks through the language of possession which disrupts the linear temporal progression of Pakistani film histories.

Following Gaur and Madani’s articulation of the specters of cinema’s past is Bani Abidi’s photo-essay showing a series of burnt film reels from a fire which decimated one of Pakistan’s oldest cinemas in Karachi. The burnt film reels, symbolising that which has simultaneously been erased but which still persists, perfectly encapsulates Gaur and Madani’s theorisation of the haunting presence of Pakistan’s forgotten cinematic worlds. Abidi’s photo-essay is followed by Iftikhar Dadi’s analysis of Zinda Bhaag (Gaur and Nabi, 2013) and his reading of formal conventions and thematic tropes which define New Pakistani Cinema. In his critique of the formulaic nature of recent Pakistani films, Dadi sees a future for Pakistani cinema in the form and thematic engagement of Zinda Bhaag , ‘a future in which narrative form is critically rethought, where a fuller range of social, cultural, and media references are engaged reflexively and intelligently rather than resorting to congealed stereotypes’ (p. 110).

In a similar vein, Ayesha Jalal’s contribution on the different biopics of Saadat Hassan Manto and Vazira Zamindar’s essay on Waar (Bilal Lashari, 2013) and New Cinema’s relation to the Pakistani military are provocative invitations for thinking about New Cinema’s ideological frameworks and representational politics. Asad Ali’s essay ‘Pissing Men, Dancing Women, and Censuring Oneself’ takes the case of gender constructions and class dynamics in his analysis of two major New Cinema films. These essays provide useful theoretical frameworks that can lend themselves to the study of other New Cinema films that have not found focal attention in this volume.

Finally, Kamran Asdar Ali’s essay on finding a queer archive of female friendships in Pakistani visual culture and Vazira Zamindar’s essay on the Guddu Film Archive both rethink modes of archiving in a country that is marked by the absence of official film archives. Zamindar’s conversations with Guddu Khan, who collects film ephemera, reveal other histories of Pakistan’s cinematic pasts, ones outside narratives of death and decline; and Asdar Ali’s reading of Saheli (S. M. Yusuf, 1960) makes visible a queer archive of desire that at once remained illegible to the state and yet which left its fugitive traces across history. The volume concludes with Rachel Dwyer’s afterword which makes a compelling case for further engagement on the cinematic traditions of Pakistan not simply for its own sake but to also account for the continued transnational linkages Pakistan has had with Indian cinema and the cinemas in South Asia.