Essay on Smoking

500 words essay on smoking.

One of the most common problems we are facing in today’s world which is killing people is smoking. A lot of people pick up this habit because of stress , personal issues and more. In fact, some even begin showing it off. When someone smokes a cigarette, they not only hurt themselves but everyone around them. It has many ill-effects on the human body which we will go through in the essay on smoking.

Ill-Effects of Smoking

Tobacco can have a disastrous impact on our health. Nonetheless, people consume it daily for a long period of time till it’s too late. Nearly one billion people in the whole world smoke. It is a shocking figure as that 1 billion puts millions of people at risk along with themselves.

Cigarettes have a major impact on the lungs. Around a third of all cancer cases happen due to smoking. For instance, it can affect breathing and causes shortness of breath and coughing. Further, it also increases the risk of respiratory tract infection which ultimately reduces the quality of life.

In addition to these serious health consequences, smoking impacts the well-being of a person as well. It alters the sense of smell and taste. Further, it also reduces the ability to perform physical exercises.

It also hampers your physical appearances like giving yellow teeth and aged skin. You also get a greater risk of depression or anxiety . Smoking also affects our relationship with our family, friends and colleagues.

Most importantly, it is also an expensive habit. In other words, it entails heavy financial costs. Even though some people don’t have money to get by, they waste it on cigarettes because of their addiction.

How to Quit Smoking?

There are many ways through which one can quit smoking. The first one is preparing for the day when you will quit. It is not easy to quit a habit abruptly, so set a date to give yourself time to prepare mentally.

Further, you can also use NRTs for your nicotine dependence. They can reduce your craving and withdrawal symptoms. NRTs like skin patches, chewing gums, lozenges, nasal spray and inhalers can help greatly.

Moreover, you can also consider non-nicotine medications. They require a prescription so it is essential to talk to your doctor to get access to it. Most importantly, seek behavioural support. To tackle your dependence on nicotine, it is essential to get counselling services, self-materials or more to get through this phase.

One can also try alternative therapies if they want to try them. There is no harm in trying as long as you are determined to quit smoking. For instance, filters, smoking deterrents, e-cigarettes, acupuncture, cold laser therapy, yoga and more can work for some people.

Always remember that you cannot quit smoking instantly as it will be bad for you as well. Try cutting down on it and then slowly and steadily give it up altogether.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conclusion of the Essay on Smoking

Thus, if anyone is a slave to cigarettes, it is essential for them to understand that it is never too late to stop smoking. With the help and a good action plan, anyone can quit it for good. Moreover, the benefits will be evident within a few days of quitting.

FAQ of Essay on Smoking

Question 1: What are the effects of smoking?

Answer 1: Smoking has major effects like cancer, heart disease, stroke, lung diseases, diabetes, and more. It also increases the risk for tuberculosis, certain eye diseases, and problems with the immune system .

Question 2: Why should we avoid smoking?

Answer 2: We must avoid smoking as it can lengthen your life expectancy. Moreover, by not smoking, you decrease your risk of disease which includes lung cancer, throat cancer, heart disease, high blood pressure, and more.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Health Education Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, conflict of interest statement.

- < Previous

The impact of school smoking policies and student perceptions of enforcement on school smoking prevalence and location of smoking

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

C. Y. Lovato, C. M. Sabiston, V. Hadd, C. I. J. Nykiforuk, H. S. Campbell, The impact of school smoking policies and student perceptions of enforcement on school smoking prevalence and location of smoking, Health Education Research , Volume 22, Issue 6, December 2007, Pages 782–793, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyl102

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The purpose of this study was to comprehensively assess the impact of school tobacco policy intention, implementation and students' perceptions of policy enforcement on smoking rates and location of tobacco use during the school day. Data were obtained from all students in Grades 10–11 ( n = 22 318) in 81 randomly selected schools from five Canadian provinces. Policy intention was assessed by coding written school tobacco policies. School administrators most familiar with the tobacco policy completed a survey to assess policy implementation. Results revealed policy intention and implementation subscales did not significantly predict school smoking prevalence but resulted in moderate prediction of tobacco use on school property ( R 2 = 0.21–0.27). Students' perceptions of policy enforcement significantly predicted school smoking prevalence ( R 2 = 0.36) and location of tobacco use ( R 2 = 0.23–0.63). The research findings emphasize: (i) the need to consider both written policy intention and actual policy implementation and (ii) the existence of a policy is not effective in controlling tobacco use unless the policy is implemented and is perceived to be strongly enforced.

School-based strategies are a key element in adolescent tobacco control because school environments are established systems in which adolescent behavior can be targeted and in which social behaviors are reinforced [ 1 , 2]. School tobacco policies are critical to a comprehensive adolescent tobacco control program, yet research to date shows inconsistencies in the way policies are measured and evaluated. Furthermore, little is known about the most effective strategies linking characteristics of school tobacco policies to adolescent tobacco use.

There has been an increased interest and emphasis on tobacco policies and their impact on youth tobacco use. Studies have shown that school tobacco policies are effective only if they are strongly enforced [ 3 , 4 ]. A comprehensive review of the effects of school policies on youth smoking rates shows inconclusive findings [ 4–11 ]. Some of the ambiguity in strength of relations between policies and smoking behavior is likely a result of the differences in dates when the research was conducted (spanning the 17 years from 1989 to 2006), geography (i.e. Australia, Canada, Scotland and the United States), definitions of smoking behavior used as the outcome variable (i.e. current smoker, daily smoker, occasional smoker, susceptible smoker), sample size, operationalization of tobacco policies (i.e. intention, implementation, enforcement) and conceptualization of tobacco policy strength (i.e. students' versus teachers' perceptions of the policies and/or coded written policies). Based on these observations, it is important to identify consistencies in the way school policies are examined and to determine the relationships among policy intentions, implementation, enforcement and smoking behaviors during adolescence.

Policies that prohibit tobacco use vary in their target application, location of application and timing of enforcement. It is understood that strong policy intention and implementation should include emphases on comprehensiveness, prevention, cessation, punishment, consistency of enforcement, strength and visibility [ 3 , 11–13 ]. The difficulty in exploring distinctions between strength of policy intention and implementation lies in the assessment of written policies with inherent intention to curtail smoking behaviors, and in exploring school informants' strategies to implement written policies. The application of these assessments to research and practice is of value to understanding policy impact.

A written policy can be viewed as a statement of intent addressing tobacco control in the school environment. The application of the written policy is not actualized in practice until the policy is implemented at the school. Furthermore, this actualization may not impact the school environment unless compliance is ensured through enforcement. This level of distinction is often overlooked in policy reviews, yet the use of consistent definitions of policy intention and implementation is critical to the examination of policy content, enforcement and effectiveness. One method of ensuring consistency of policy evaluation is to employ coding rubrics that capture the complexities of both policy intention and implementation. For example, a comprehensive coding rubric for written tobacco policies has been developed to include the main factors critical to strong policies [ 13 ]. The coding system includes five main components: developing, overseeing and communicating the policy, purpose and goals, tobacco-free environments (including prohibition, strength and characteristics of enforcement), tobacco use prevention education and assistance to overcome tobacco addictions. Despite some initial testing of the rubric [ 13 ] it has seen limited use. More importantly, the different roles that school policy components play in influencing adolescent smoking behaviors remains elusive.

In addition to the lack of consistent evaluation strategies associated with written tobacco policies, the other main limitations in research linking policies and smoking behavior include: (i) the dependence on adolescents' perceptions of the strength of school policies; (ii) limited assessments of the consistency between policy intention and implementation and (iii) unclear conceptual links between the tobacco policy variables and youth smoking classifications. Specifically, in research linking tobacco policies and smoking behavior, it is not necessarily that tobacco policies will directly impact whether an individual is a daily or an occasional smoker, or whether they have ever tried a cigarette, but rather they will impact how the school environment contributes to shaping these behaviors. School-based policies should, at minimum, impact the frequency and location of smoking behavior that occurs around and at school. Efforts should be focused on characteristics of smoking behavior that are likely to be influenced, both directly and indirectly, by school-based tobacco policies.

The purpose of this paper is to (i) describe an approach for assessing school smoking policies, (ii) examine differences between school written policy (intention) and reported implementation; (iii) examine characteristics of school written (indention) policies and reported implementation as predictors of school smoking prevalence, as well as smoking prevalence at school, on and off school property and (iv) examine students' perceptions of policy enforcement as predictors of school smoking prevalence.

Participants

Following ethics approvals from the University and Secondary School Districts, a multi-site cross-sectional study was conducted in 81 randomly selected secondary schools from British Columbia, Manitoba, Newfoundland, Ontario and Quebec. The five provinces represent a reasonable geographical balance and have smoking rates that span the range of Canada's overall smoking rate for youth aged 15–19 years (15–24%) [ 14 ].

Following a passive parental consent approach, all students in Grades 10 and 11 ( n = 22 318) within the 81 sampled schools were asked to complete a questionnaire about their smoking attitudes and behavior. From each school, a senior school administrator with extensive knowledge of the tobacco policy was recruited to complete a questionnaire about the implementation of the school smoking policy (i.e. survey on school smoking policies). In the final sample, administrators included principals (50%), vice principals (47.4%), assistant vice principals (1.3%) and teachers (1.3%). Written tobacco policies were also collected from each school and each corresponding school district board for assessment of policy intention.

Data sources and measures

Written school tobacco policies (intention).

To assess policy intention, school policies were collected from administrators, official policy documents or web pages. In the event that schools did not have a written policy, the district policy was obtained since it was the school's official tobacco control document. To assess the strength of policy, the hard copies were coded by two trained researchers using a theoretical and conceptually derived rating scheme [ 13 ]. Modifications to the existing rubric were made to reflect the Canadian context and recent theoretical findings [ 3 , 15 , 16 ]. Several Canadian experts on policy evaluation and implementation were also consulted during this process. Modifications to Stephens and English rubric [ 13 ] involved creating separate subscales for prohibition, strength and characteristics of enforcement instead of using the broader category of ‘tobacco-free environments’. The final rating system was composed of seven policy components that were derived from a number of items: developing, overseeing and communicating the policy; purpose and goals; prohibition; strength of enforcement; characteristics of enforcement; tobacco use prevention education and assistance to overcome tobacco addictions (see Table I for sample items). Two trained researchers used the rating system as a directed assessment instrument to code to the policies. The coders read through the school and district written policies and rated each policy components from ‘poor’ to ‘outstanding’ using a combination of Likert scale and dichotomous response sets. When rating discrepancies occurred, they were discussed until consensus was established.

Sample questions from the policy intention and implementation subscales

School tobacco policy implementation

To assess the implementation of school tobacco policies, it was necessary to develop a structured survey that supported the main policy rubric informing this study. Development of the survey incorporated school health questionnaires [ 17 , 18 ] and guidelines from prominent policy research [ 3 , 13 ]. The survey was pilot tested by three school administrators (not included in our sample) before it was finalized to a total of 41 items (survey can be obtained from first author).

The resulting survey of school smoking policies was completed by school administrators who were knowledgeable about tobacco policies. The responses were coded using the same protocol and scoring system was described for the written school policies (see Table I ). Similar procedures were used to ensure comparability between written policies (intention) and the structured interviews (implementation). The final rating system for policy implementation included an additional subscale for consistency of enforcement.

Student smoking and perceptions of policy enforcement

Student smoking behaviors were assessed using the tobacco module of the School Health Action, Planning and Evaluation System (SHAPES) [ 19 ] which is a research-supported machine readable survey designed to collect perceptions related to multiple characteristics of youth tobacco use [ 19 ]. For this study, questions pertaining to frequency and quantity of tobacco consumption were used to define smoking behavior. A smoker was defined as an adolescent who had smoked at least a few puffs of a cigarette on ≥2 days in the last month. The individual data were used to create two dependent variables. First, a composite score assessing smoking status, which was then converted into a school prevalence rate by adding the number of smokers at each of the schools represented, divided by the total students at the school. Second, prevalence of smokers who smoke at school both on and off the property (location of smoking behavior) was calculated. Prevalence of smoking behavior location was calculated as a ratio of smokers indicating they smoked on and/or off school property divided by the total number of smokers at each school.

Items from SHAPES were also used to create five independent variables related to student perceptions of policy enforcement at the school: (i) perception regarding the percentage of students who smoke (10-point Likert scale ranging from 0–10% to 91–100%); (ii) whether there are punishments for smoking on school property (percentage of students reporting ‘true’ and ‘usually true’); (iii) existence of a clear set of tobacco use rules at school (percentage of students reporting ‘true’ and ‘usually true’); (iv) strong sanctions for breaking the tobacco rules (percentage of students reporting ‘true’ and ‘usually true’) and (v) whether students smoke where they are not allowed (four-point Likert scale ranging from none to a lot).

Data analyses

Prior to main analyses, it was important to assess the validity of the instruments used to code the policies. Nine completed surveys assessing both policy intention and implementation were randomly selected and given to six experts in the field of tobacco policy who were asked to rank order them in terms of strength, and to include rationale for their decisions. This rank ordering was compared with the strength of scores generated from the developed rating system as coded by the trained researchers. The survey and the rater's rankings elicited the same policy strength scores 83.4% of the time.

Following the validation of the policy measures, the psychometrics of the policy scale scores and aggregated data from SHAPES (i.e. smoking behaviors and students' perceptions of policy enforcement) were examined. Descriptive analyses were conducted to examine correlations, means and standard deviations (SDs). t -tests were conducted to examine significant mean differences and between policy intention and implementation. The main analyses involved independent multiple linear regressions conducted to examine (i) policy implementation (reported by school administrators), (ii) policy intention (from written policies) and (iii) students' perceptions of policy enforcement, as predictors of school smoking prevalence and smoking behaviors occurring on and off school property during the school day. No simultaneous models including intention, implementation and perceptions of enforcement were conducted due to the limited power resulting from the small sample size. Since there were no theoretical or conceptual reasons to expect differences among the predictors, all policy subscales were entered in step one. For all analyses, the significance level was set at 0.05. Given the number of predictors and sample size, we recognize the possibility of inflated Type I errors. However, the exploratory nature of this study begins to address an existing gap in the literature. It was desirable to use this approach to identify the majority of factors that may influence school smoking rates.

The majority of schools (80%) had their own tobacco policy, with the remaining schools reporting use of the district policy (see Table II ). The policy intention subscales for tobacco use prevention education and assistance to overcome tobacco addiction were indiscriminant across the schools and were not included in the main regression analyses.

Means and SDs for the policy data

The relationships among smoking prevalence and school-based tobacco control policies are presented in Table III . Very few of the policy implementation subscales were related to policy intention. The majority of students' perceptions of policy enforcement items was significantly correlated with the intention and implementation subscales. None of the policy intention and implementation subscales was related to smoking prevalence. However, student perceptions regarding the percentage of smokers attending the school were related to school smoking prevalence. There were many significant relationships among policy intention, implementation and students' perceptions of school tobacco policy enforcement and smoking prevalence (at school) on and off school property.

Correlations among the policy subscales and smoking prevalence

1, school smoking prevalence; 2, off school property smoking prevalence; 3, on school property smoking prevalence; 4–10, policy intention subscales (4, developing, overseeing and communicating policy; 5, purpose and goal; 6, prohibition; 7, strength; 8, characteristics; 9, tobacco use prevention education; 10, assistance to overcome tobacco addiction); 11–17, policy implementation subscales (11, developing, overseeing and communicating policy; 12, purpose and goal; 13, prohibition; 14, strength; 15, characteristics; 16, consistency; 17, tobacco use prevention education; 18, assistance to overcome tobacco addiction); 18, perception of smoking where not allowed; 19, perception of smoking prevalence; 20, prevalence perception that students can be fined; 21, prevalence perception of clear set of rules; 22, prevalence perception consequences of breaking rules.

P < 0.05.

Differences between intention and implementation subscales

To explore the differences in intention and implementation subscales, a number of t -tests were conducted using a Bonferroni technique to protect against Type 1 errors. Implementation subscales were significantly higher than intention subscales: developing, overseeing and communicating policy, t (1, 76) = 22.50, P < 0.001; prohibition, t (1, 76) = 12.79, P < 0.001; strength of enforcement, t (1, 76) = 9.64, P < 0.001; characteristics of enforcement, t (1, 76) = 9.31, P < 0.001; tobacco use and prevention education, t (1, 76) = 3.04, P < 0.001 and assistance to overcome tobacco addiction, t (1, 76) = 10.82, P < 0.001. The subscales for purpose and goals were not significantly different. Policy implementation had an additional subscale (consistency of enforcement) that was not included in comparative analyses.

Predictors of school smoking prevalence and location of smoking behavior

School smoking prevalence.

To examine policy intention and implementation as predictors of school smoking prevalence, a multiple regression was planned. However, the correlations among both policy implementation and intention showed little, if any, relationships and no further analyses were conducted. The model predicting school smoking prevalence from students' perceptions of school policy was significant, F (5, 72) = 7.86, P < 0.001, R 2 = 0.36, with perception of smokers emerging as an independent predictor (see Table IV ).

Regression analyses predicting school smoking prevalence from perceptions of policy enforcement

Smoking location: at school, on school property

To test the hypothesis that schools with weaker policy intention and implementation would have more smokers using tobacco at school, separate regressions were conducted with location of smoking as the dependent variable (see Table V ). For policy intention, the model was significant, F (5, 70) = 5.17, P < 0.05. The policy intention subscales accounted for 27% of the variance in on school property tobacco use, with prohibition, strength and purpose and goals emerging as significant individual predictors. For policy implementation, the model was also significant, F (8, 69) = 2.28, P < 0.05, R 2 = 0.21. The individual significant predictors included prohibition, consistency of enforcement and tobacco use prevention education. Finally, the model examining adolescents' perceptions of policy enforcement predicting smoking on school property was also significant, F (5, 72) = 22.72, P < 0.001, R 2 = 0.62. The significant independent predictors in the model included perceptions that students can be fined, breaking the rules leads to consequences and prevalence of smokers at school.

Regression analyses predicting tobacco use on school property from policy intention (Model 1), policy implementation (Model 2) and perceptions of policy enforcement (Model 3)

Smoking location: at school, off school property

Regressions were also conducted with smoking on school property as the dependent variable (see Table VI ). The first regression included all policy intention subscales as predictors of smoking at school but off property. The model was not significant, F (5, 70) = 0.190, P > 0.05, R 2 = 0.01. The second regression included the policy implementation subscales as predictors of smoking off school property. The model was not significant, F (8, 69) = 1.85, P = 0.09, R 2 = 0.17. Finally, the model exploring adolescents' perceptions of policy enforcement as predictors of smoking off school property was tested. In this model, adolescents' perceptions of more students smoking where they are not allowed and greater perception of smokers at the school were significant independent predictors in the model, F (5, 72) = 4.11, P < 0.001, R 2 = 0.23.

Regression analyses predicting tobacco use off school property from policy intention (Model 1), policy implementation (Model 2) and perceptions of policy enforcement (Model 3)

The coding scheme developed in this study was used to explore school written tobacco policy intention and administrator-reported policy implementation in secondary schools across Canada. Results revealed few of the school policy implementation subscales were related to written policies (intention) and none of the policy subscales was correlated to smoking prevalence. However, there were many significant relationships among policy intention, implementation and students' perceptions of school tobacco policy enforcement and smoking prevalence at school (both on and off school property). Several moderate predictive models exploring characteristics of adolescent smoking behaviors were observed.

Comparing the strength of the policies, implementation scores were significantly higher than intention for all but one subscale (i.e. purpose/goals). In particular, it is encouraging to note that strength and characteristics of enforcement were higher than the intention subscales since tobacco policies have maximum benefit only when they are strongly enforced [ 3 , 4 ]. The differences may be due to the length of time that the written policy has been in place at the school. However, it may also be that administrators were more optimistic in their reporting of implementation; thus this finding should be interpreted with caution. This result highlights the need to assess both policy intention and implementation.

School smoking prevalence was not significantly related to policy intention or implementation. This suggests that school policies do not have direct consistent effects on smoking prevalence. A number of researchers have noted similar relationships among school tobacco use policies and adolescent smoking prevalence [i.e. 5, 8–11]. Conceptually, it is not surprising that a school policy alone fails to impact school smoking prevalence unless part of a comprehensive tobacco control program. The synergistic impact of tobacco control policies, prevention and cessation programs and other forms of tobacco control approaches in the school (such as health education curriculum and anti-smoking campaigns and promotions) are likely to be most influential and require further investigation for the impact on school smoking.

Students' perceptions of policy enforcement were moderately linked to smoking prevalence. In the predictive model, a perception that there were a higher number of smokers at school was the strongest predictor of smoking prevalence. This finding is supported in research using social cognitive frameworks, where observational learning is a strong predictor of behavior [ 20 , 21 ]. These types of modeled behaviors should be considered when policies are developed and enforced. Furthermore, teacher and staff smoking prevalence were not explored in this study but have the potential to impact student smoking through modeling mechanisms and should be included in future studies. There are reports to suggest that teacher smoking during school hours is associated with adolescent smoking [ 22 ]. If schools can reduce the visibility of tobacco use, both by students and teachers, it will likely have positive effects on controlling the prevalence of adolescent smoking behaviors. This is a potent area for developing awareness and influencing behavior.

None of the school policy intention or implementation subscales significantly predicted smoking prevalence off school property. This finding was expected since school policies likely have more influence on smoking behaviors exhibited on school property. Alternatively, schools with written policies (intention) describing low prohibition, greater strength of enforcement and clearly established purpose and goals had higher smoking rates on school property. For administrator-reported implementation, low prohibition, greater consistency of enforcement and the absence of tobacco use prevention education were related to high smoking rates on school property. These results suggest that further work is needed to decipher the complex interrelationships among prohibition, enforcement, prevention education and school environment when examining smoking on school property. For example, if schools have designated smoking areas (i.e. smoking pit), the higher strength and consistency of enforcement of tobacco policies may be propagating tobacco use on school property but limiting smoking to specific areas. In this case, further research is needed to examine smoking on school property and the possible covariance associated with designated smoking areas. Additionally, students' knowledge and understanding of their school policy is unknown and may interact with smoking behavior. It would be beneficial to assess students' recall and recognition of school-based tobacco policies and to control for these effects when examining smoking behavior.

Students' perceptions of policy enforcement were strongly predictive of smoking on school property. Specifically, in schools where punishment was not perceived a consequence of smoking, there were more students smoking on school grounds. This finding is consistent with previous research [ 5 , 7 ] and highlights the importance of communicating the consequences of breaking the tobacco policy rules. We also found that schools where adolescents' perceived more student smokers had high smoking rates on school property. This finding may again illustrate the power of observational learning and highlights the importance of reducing the visibility and awareness of adolescent smoking behaviors at school.

There are a number of limitations associated with this study. First, the coding rubrics and surveys developed for this project need to be further tested for their reliability and validity. Also, confirmatory factor analyses are needed to examine the factor structure of tobacco policies. The cross-sectional design and relatively small sample of schools in this study preclude more advanced analyses and limit the power to detect statistical results. Future research should explore the longitudinal relationships among tobacco policies and characteristics of smoking behaviors during adolescence.

Despite its limitations, this study makes important contributions to research on school tobacco policies. The conceptualization of policies as intention and implementation, coupled with the development of a coding paradigm used to assess policies, begins to address the need for consistent definition and evaluation of tobacco policies. A cost-effective and practical approach to measure policy implementation reliably is a challenge. Developing student items for cross-validation with administrator reports may be one approach to addressing this challenge. Future studies should continue to move beyond simple classification of smokers and non-smokers and examine conceptually plausible relationships between policy and different smoking behaviors. There are many more opportunities for intervention when we consider location and timing of tobacco use among student smokers at school. In conclusion, exploring the differences between policy intention and implementation highlights the need to further examine inconsistencies in the way tobacco policies are written and the strategies used to implement them. As practitioners, it is important to focus on bridging this gap to ensure consistent and clearly communicated tobacco use prohibition strategies.

None declared.

This research was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant no. 62748. We are pleased to acknowledge the contribution of Helen Hsu and Jane Shen who assisted in reviewing the literature. Technical assistance was also provided by Tamiza Abji and Sarah Lockman. Above all, we thank the high school administrators and students who completed the surveys. The research presented in this article is part of a larger study which along with school-based smoking policies is examining the relationship between adolescent tobacco use, school-based programs and factors in the community environment.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

- tobacco use

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-3648

- Print ISSN 0268-1153

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

School smoking bans reduce teen smoking

An international study of junior high- and high school-aged students who attended schools where smoking was banned were less likely to smoke than those where smoking was permitted, according to a study led by researchers at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Smoking bans also were found more effective in preventing students from smoking than just classroom-based tobacco education in the study, which did not include U.S. schools.

Researchers, led by Israel Agaku of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Center for Global Tobacco Control , compared data gathered from 2005 to 2011 on students, ages 13 to 15, in 43 nations. In countries with moderate-to-strongly enforced smoke-free-school policies, kids were 41% less likely to smoke than kids in countries with poorly enforced or no smoke-free-school policies.

Olubode Olufajo, research fellow in the School’ s Department of Epidemiology , was a co-author.

Read a Globe and Mail January 13, 2015 article about the study: Tobacco bans in school linked to lower smoking levels

Read the study in the European Journal of Public Health .

E-cigarettes in Europe used mostly by the young, current smokers, would-be quitters

Teens who use smokeless tobacco often smoke

Reducing smoking in youth by a smoke-free school environment: A stratified cluster randomized controlled trial of Focus, a multicomponent program for alternative high schools

Affiliations.

- 1 National Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 2 Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 3 Center for Clinical Research and Prevention, Bispebjerg-Frederiksberg University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- PMID: 34131598

- PMCID: PMC8171329

- DOI: 10.18332/tpc/133934

Youth smoking remains a major challenge for public health. Socioeconomic position influences the initiation and maintenance of smoking, and alternative high school students are at particularly high risk. The school environment is an important setting to promote health, however there is a lack of evidence-based school intervention programs. This article presents the Focus study, which aims to test the implementation and effectiveness of a school-based intervention integrating 1 a comprehensive school smoking policy [i.e. smoke-free school hours (SFSH)] 2 , a course for school staff in short motivational conversations 3 , school class-based teaching material 4 , an edutainment session5, a class-based competition, and6 access to smoking cessation support. Together these intervention components address students' acceptability of smoking, social influences, attitudes, motivation, and opportunities for smoking. The setting is alternative high schools across Denmark, and the evaluation design is based on a stratified cluster randomized controlled trial comparing the intervention group to a control group. Outcome data is collected at baseline, midway, and at the end of the intervention period. Moreover, a detailed process evaluation, using qualitative and quantitative methods, is conducted among students, teachers, and school principals. The results from this trial will provide important knowledge on the effectiveness of a smoke-free school environment. The findings will lead to a better understanding of which policies, environments, and cognitions, contribute to preventing and reducing cigarette use among young people in a diverse and high-risk school setting, and illuminate which complementary factors are significant to achieve success when implementing SFSH.

Keywords: adolescents; alternative high school; intervention studies; school tobacco policies; social environment; tobacco prevention.

© 2021 Jakobsen G. S. et al.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

School smoking policies and health science students' use of cigarettes, shisha, and dipping tombak in sudan.

- Faculty of Social Sciences, Health Sciences, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland

The relationship between school smoking policies and students' tobacco use is ambiguous, and little is known about the effect of these policies in low- and middle-income countries. This study was designed to assess the effects of schools' smoking policies and the exposure to residential smoking on cigarette smoking and the use of different kinds of tobacco products by Health Science students. Self-reports of cigarette smoking, use of shisha (smoking of fruits-mixed tobacco using a bowl and a connected hose); dipping tombak (local smokeless tobacco that users usually place inside oral cavity in the groove behind the lower lip), and tobacco use on school premises are analyzed. A cross-sectional survey was carried out using a modified self-report questionnaire, originally developed by WHO, among a representative sample of 1,590 third-year HSS from 25 schools drawn from 13 universities, using a multi-stages sampling technique. The response rate was 100% for schools and 68% for students. A multilevel analysis was performed by nesting student-level in school-level variables. Results from the adjusted models revealed that, when students reported awareness of smoking restriction, they were more likely to be current smokers (OR = 2.91; 95% CI: 1.68–5.02; p = 0.021) and shisha users (OR = 2.17; 95% CI: 1.54–3.06; p = 0.021). Results from additional analysis performed among tobacco users only, showed increased risk of smokers and tombak dippers who smoked or dipped on school premises (OR = 2.38; 95% CI: 1.34–4.25; p = 0.003, OR = 2.60; 95% CI: 1.22–5.56; p = 0.013, respectively). Current smokers (OR = 3.12; 95% CI: 1.98–4.92; p = ≤ 0.001), ever smokers (OR = 1.66; 95% CI: 1.31–2.10; p = ≤ 0.001) and shisha users (OR = 1.73; 95% CI: 1.36–2.21; p = ≤ 0.001) were exposed to residential smoking on one or more days during the previous 7 days. High percentages of those who used any kind of tobacco products reported being aware of school smoking policies, indicating no clear evidence that school smoking policies had an effect on use of any of the mentioned tobacco products. The lack of compliance with school policies shows the need for further policy enforcement and sustainability, taking into account the effect of residential smoking and social influences.

Introduction

Tobacco use is one of the greatest challenges to public health, with steadily increasing consumption and a rapidly growing epidemic in the low- and middle-income countries ( 1 ). It has been well documented with overwhelming scientific evidence that trends of tobacco product use are increasing for some sub-groups within the global population, and its effect on health is undeniable. The available data demonstrate that about one quarter of the world's adult population currently smokes, and several million people become fatally addicted every year ( 2 – 4 ). Most documented successes in reducing tobacco use have occurred in developed countries by effective tobacco control policies ( 5 , 6 ). In contrast, most of the developing countries require more efforts to reach a comparable level. Despite the evidence, some policy-makers in low-income countries have failed to regard tobacco use as a health priority and do not fully appreciate the essential influence of public policies related to tobacco control ( 7 ). This lack of understanding is one partial explanation for the near absence of adequate prevention measures in these countries ( 8 ).

The problem is particularly challenging in Africa, which presents a great risk in tobacco use. Cigarettes are becoming increasingly affordable, and there are limited strategies to combat the increasing trends in use of shisha ( 1 , 9 ), use of smokeless tobacco ( 10 ), and their harmful effects on future morbidity and mortality ( 1 , 11 ). This shift to developing settings is partly because of the global tobacco industry fierce marketing strategies and partly due to lack of adequate tobacco control measures ( 7 , 12 , 13 ). In Sudan, as one example of a sub-Saharan African country, smoking cigarettes, shisha use, and tombak dipping are widely spread among adolescents and young adults ( 14 , 15 ).

Schools are particularly important and considered to be the best places where students' tobacco use can be targeted. Schools represent a key environment where prevention and control strategies can be implemented ( 16 , 17 ). Anti-smoking policies can reduce the prevalence of smoking by promoting prevention, restriction, cessation, and by preventing students from using tobacco on school premises and protecting non-smokers ( 18 – 20 ). Well-known statements document that smoking behavior is mainly recognized and established at or before the age of 18 ( 21 ). Consequently, smoking prevention programs have been focused on adolescents, mainly within school settings. Other researchers have suggested that college students might be an important audience in initiation and in the development of regular smoking ( 22 ), whatever the age of the students. In addition to schools, a better understanding of the main factors that affect students' tobacco habits in other environments would be useful for policy formulation in tobacco control programs. For instance, exposure to smoking in students' neighborhoods and residential areas can have an important role in their tobacco use ( 23 ).

Regardless of the methodological issues or the heterogeneity of exposure definitions in observational studies, various researchers have evaluated the effectiveness of school tobacco policies ( 20 , 24 ). Some of them revealed a significant association between student smoking on school premises and weak policy ( 25 ). Others concluded that perceptions of students' smoking on the school premises also varied according to enforcement of smoking restrictions ( 20 , 26 ).

These policies are particularly important in Health Science students' schools, where students are trained and seeking careers in the health professions. Ideally, they will be role models for patients. The extent to which they effectively guide tobacco users may largely depend on their own tobacco use behavior ( 27 ). In Africa, doctors are regarded as the most likely persons from whom advice about tobacco use would be accepted by both users and non-users. Very brief advice from the doctor yields positive 1-year quit rates ( 28 ).

Within a multilevel context, the study reported here was designed to examine the effects of university policies and residential smoking on smoking and the use of different kinds of tobacco products by students studying in the Health Science disciplines of medicine, dentistry, nursing, and pharmacy. Third-year students were asked to self-report their use of cigarettes, tombak dipping, and shisha, as well as their awareness of school policies that banned or restricted use of tobacco products, and their exposure to smoking in places where they live.

The current study used cross sectional collection of data as part of the Global Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS) 2007. Full details of the surveys can be found elsewhere ( Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2006 ) ( 29 ). Newer data, targeting the same student population, can not be obtained because the conditions of the country have changed, Sudan split into two countries.

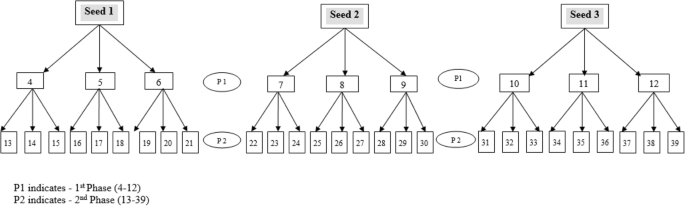

A multi-stage cluster sampling design was used in the first part of the sampling technique . The first stage : from a total number of 39 public and private universities, 13 universities were selected based upon having a school of medicine, dentistry, nursing, or pharmacy, or any combination of these four schools (one university might have one or more Health Science schools). The rest, 26 universities, were eliminated because they did not meet the selection criteria. The second stage : all Health Science schools ( N = 29) were drawn from the 13 universities. Four of the 29 Health Science schools were eliminated because they were new and did not have a third class at the time of the survey. Thus, the final sample became 25 schools (Medicine 10; Dentistry 6; Nursing 4; and Pharmacy 5). The third year classes in the 25 schools were selected purposively. All students who were enrolled and present in these classes, regardless of their age, were eligible to participate in the study.

The Health Science schools had a 100% school response rate. All third-year students were eligible and invited to complete the survey, with a 67% student response rate from dental schools; 64% from medical schools; 83% from nursing schools; and 71% from schools of pharmacy. On the day of the survey, students who had left the classroom (21 students) or those who were absent for any other reasons were not followed up. From the 2,344 registered eligible students, 1,590 students responded, giving an overall response rate of 68%.

The survey was an anonymous, modified self-reported questionnaire originally developed by the Tobacco Free Initiative and the World Health Organization (WHO) in collaboration with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The questionnaire used was originally in English, and later translated into Arabic by an expert team from the Sudan Ministry of Health (SMOH).

The Sudanese research coordinators, including the author of this study, trained the data collectors from the Ministry of Health, and supervised the data collection. The survey was first piloted among 50 non-Health Science students to determine clarity of questions and to ensure feasibility of administration and the accuracy of translation. After incorporating the corrections, the process resulted in removing, adding or changing some questions, resulting in a final set of 44 questions. These were then back-translated into English, by an independent professional person who was not part of the first translation or study, to check for validity and to avoid bias and/or misunderstanding. The questionnaires were distributed during regular lectures and class sessions. Completion time was about 40–45 min.

Ethical Approval

Permission to conduct the study was sought from the Ministry of High Education and the Ministry of Health Research Ethics Board, the university authorities' board, and the Dean of each school. The entry point for conducting the student survey for each school was through a designated faculty member to identify the student subject pool. Informed consent was obtained for all eligible students and for each student. This process involved explaining the purpose of the research, and why they had been selected. Their consents were obtained verbally; no written permission was required of individuals at the age of 18 and above, for those who were younger than age 18, parental consents were obtained. Participation was voluntary and confidential, with the option of declining without penalty or loss of benefits to which the student would be otherwise entitled.

Definitions of Variables and Outcome Measures

The selected questions for this study included demographic characteristics, questions related to school policy and use of three types of tobacco products (cigarettes, shisha and tombak), and a final question related to smoking in places where students live.

Tobacco Products

Cigarettes are the most common type of tobacco used throughout the world. Although cigarettes come in a variety of strengths and styles, the questions on the survey did not differentiate type of cigarettes smoked.

Tombak is a loose, moist form of smokeless tobacco. The plant is of the species Nicotiana Rustica and/or glauca , with a high content of nicotine. Soute /saΩt/ is another local name for tombak. The leaves are ground for maturation for up to 1 year for uniform drying and storage for aging ( 30 ). Then they are mixed with “ Atrun or Natrun ,” which is a kind of raw alkaline material, consisting of naturally occurring chemical substances, including sodium bicarbonate. The ingredients are then mixed with water and rubbed by hand for blending and constantly tested with the tips of the fingers in a process called “ Tatmeer / ta:tæm.i r /.” The final product “tombak” will be ready for dipping after many hours (up to 1-day) of being sealed in an airtight container. tæm tiǝr tiǝr tiǝr Tombak is highly addictive because of its high nicotine content. Its use results in serious health problems that are related to several forms of oral cancer ( 10 ). The dip in Sudan is named suffa /sǝ’f’fǝ/, which is a small moist lump/ball that is made by rolling a small amount of tombak repeatedly on the palm using the thumb, index, and middle fingers of the other hand in a circular manner. Suffa is usually placed in the lower labial groove between the lower lip and the gum ( usual site of cancer in Sudan ), or under the tongue or upper lip.

Shisha is another name for “oriental water-pipe” that is well known and popular in the Middle East and North Africa. Shisha is an instrument used for smoking, consisting of a head, body, water bowl, and rubber-pipe (hose). The smoking involves heating the fruit-flavored tobacco, usually with charcoal, cooled down by passing through the water chamber at the bottom of shisha prior to inhalation. Users believe that shisha is safer than cigarettes because the smoke passes through water before inhalation ( 9 ). Shisha use is becoming increasingly popular in Sudan among young people sitting for hours at Internet cafes. Its use is also increasing among young girls and women in some beauty centers and hair styling saloons (unpublished document, SMOH, 2007).

Tobacco Use Variables

Ever tobacco user included anyone who tried any kind of tobacco products, those who had smoked, dipped tombak, or used shisha at least one time, during the course of her/his life. Each question in these categories was treated independently. The question was “ Have you ever tried or experimented with cigarette smoking/shisha/tombak dipping, even if it was one puff/dip or two? ” Responses were “Never”/“Yes.”

Current smoking question was “ During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes ?” Students were classified as “current smokers” if they reported smoking on any day of the previous month. Questions about current use of other kinds of tobacco ( shisha and tombak ) were not available in the survey therefore were not measured.

School Smoking Policy Variables

For ease of use, the term “school” was used in the text and the tables to refer to all colleges; faculties; and school under study (Dental schools, Colleges of Medicine, Nursing schools, and Faculties of Pharmacy).

Smoking on school premises

Smoking on schools' premises question was “ Have you smoked cigarettes on school premises during the last 1-year?” Responses were “Not-smoked”/“smoked.”

Dipping on schools' premises question was “ Have you dipped tombak on school premises during the last 1-year?” Responses were “Not-dipped”/“dipped.”

Two additional variables were created from the above two questions, included only the users (the current smokers and tombak dippers) who responded to the questions; and only those who reported “Yes” they had smoked or dipped on school premises were counted.

Smokers who smoked on school premises included both current and ever smokers who smoked during the prior 1-year.

Current smoking on school premises includes only current smokers who smoked on school premises during the prior 1-year.

Ever dippers on school premises includes only those who dipped tombak for the first time on school premises during prior 1-year. The variables about school policy were based on the responses to two questions; the answers were further categorized for purpose of the analysis.

Policy banning smoking

(PBS) “Does your school have an official policy banning smoking in school buildings and clinics?” Responses were “No official policy”/“exists in either of them”/“exists in both.”

Smoking restriction

Which of the following best describes your school's official smoking policy for public places or common areas “lobbies, restrooms & dining areas”? Responses were “No official policy”/“complete restriction”/“partial restriction.”

Complete restriction: Smoking not allowed in any of the mentioned places.

Partial restriction: Smoking is allowed in one of the mentioned places.

Residential Smoking Variable

The residential smoking question was “ Has anyone smoked in your presence in places where you live, on one or more days during the last 7-days ?” “No” = 0 days, “Yes” = 1–7 days. The terms of “residential smoking” and “smoking where student lives” are used interchangeably throughout this paper.

Data Analyses

Pearson's χ 2 test was performed to examine the descriptive analysis for frequencies, differences in proportion, and associations between variables. Statistical significance is reported two sided: p < 0.05. IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 was used for the preliminary analysis.

Due to the hierarchical and the tiered nature of the data, multilevel logistic regression was used to examine the relationship between school policy and residential smoking ( exposure ) and the use of tobacco by students ( outcome ). The dataset was assumed to have a two-level data structure, where individual cases (students) are nested in a higher-level group (schools). The individual-level of students' behavior related to tobacco use ( smoking cigarettes, dipping tombak, shisha, and “smoking and dipping” on school premises ) was nested at a higher-level group (25 schools) that simultaneously included policy and residential smoking in the multivariate model with the students as the unit of analysis.

Before conducting the analysis, the outcome tobacco variables were dichotomized. The data were exported to Statistical Package for Stata' gllamm (Generalized Linear Latent and Mixed Stata/SE 14.0) for multilevel logistic regression to fit random-intercept logistic models and to determine the strength of the hypothesized relationships between school policy and student tobacco behavior. A null model was first fitted and included only a random intercept to estimate the variations in the use of tobacco across schools (this model is not presented in the tables). A subsequent unadjusted model was separately fitted for each smoking policy in relation to tobacco use outcomes. A final adjusted model was fitted, adjusted for age and sex, with school level as a random effect. Student reporting about smoking on school premises was analyzed separately. The odds ratios for the fixed part of the models were estimated using 95% confidence intervals. To estimate the differences between schools, the school level variance (SE) were also measured.

Descriptive Analysis

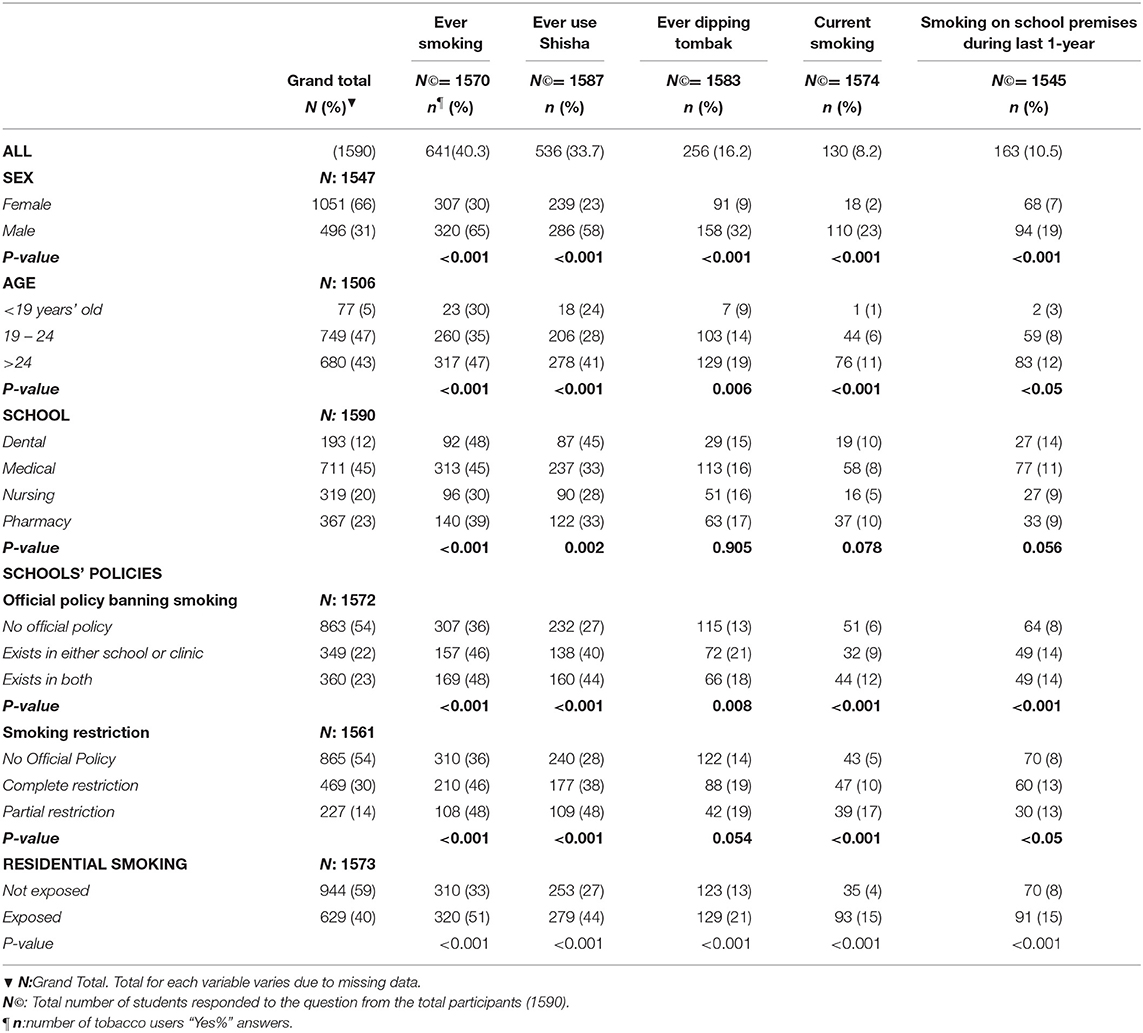

Tables 1 , 2 provide a summary of the numbers and percentages arranged by tobacco use. Students' reporting about schools' smoking policies are presented as policy banning smoking and restriction, together with exposure to residential smoking. Sample sizes differ slightly among the analyses due to differences in the patterns of missing data.

Table 1 . Percentage of tobacco users by age, sex, type of school, school smoking policies, and residential smoking.

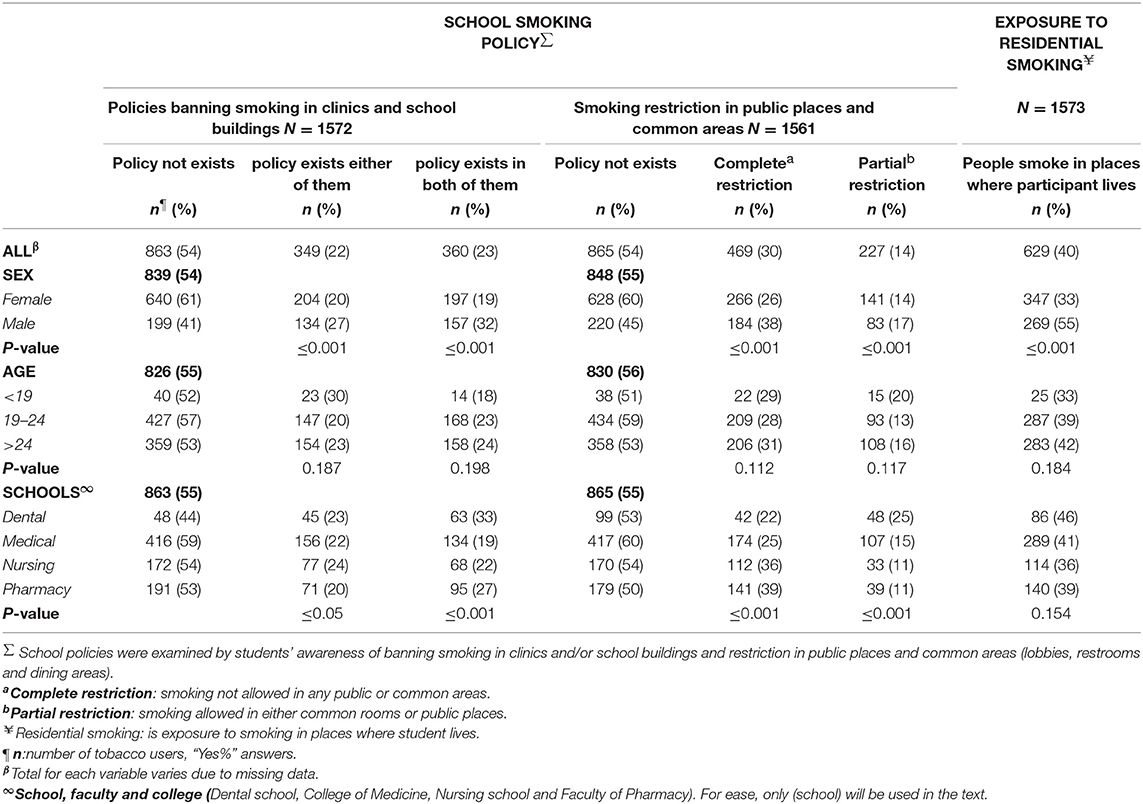

Table 2 . Percentages of students' awareness of school smoking policies as well as residential smoking by basic demographic characteristics and school type.

The 1,590 participants included more females (66%) than male students, the majority were between the ages of 19 to 24 years. Overall prevalence of ever smoking was 40.3%, more among males than females. Ever smoking, increased with age and varied between schools (ranging from 30 to 48%). The pattern was similar for shisha use. Overall prevalence of shisha use was 33.8%, dippers (16.2%) and current smokers (8.3%), more among male students. Strikingly, 10.5% of all students smoked on school premises. They were also more male students, older, and from dental schools. Those who reported that a policy existed and that smoking was restricted were more likely to smoke on school premises ( Table 1 ).

Most of ever smokers (52%), shisha users (44%), dippers (21%), and 15% of current smokers were exposed to residential smoking on any days of the previous 1 week ( Table 1 ). That means 40% of all participants were exposed to smoking where they live; more than half were male students (55%) and older (42%) ( Table 2 ).

As shown in Table 2 , more than half the students reported the non-existence of school smoking policy (54%), and there were no big differences in the percentages between schools. As reported, more nursing students than the rest reported that smoking was completely restricted in public places and common areas (39%).

Multi-Level Analysis

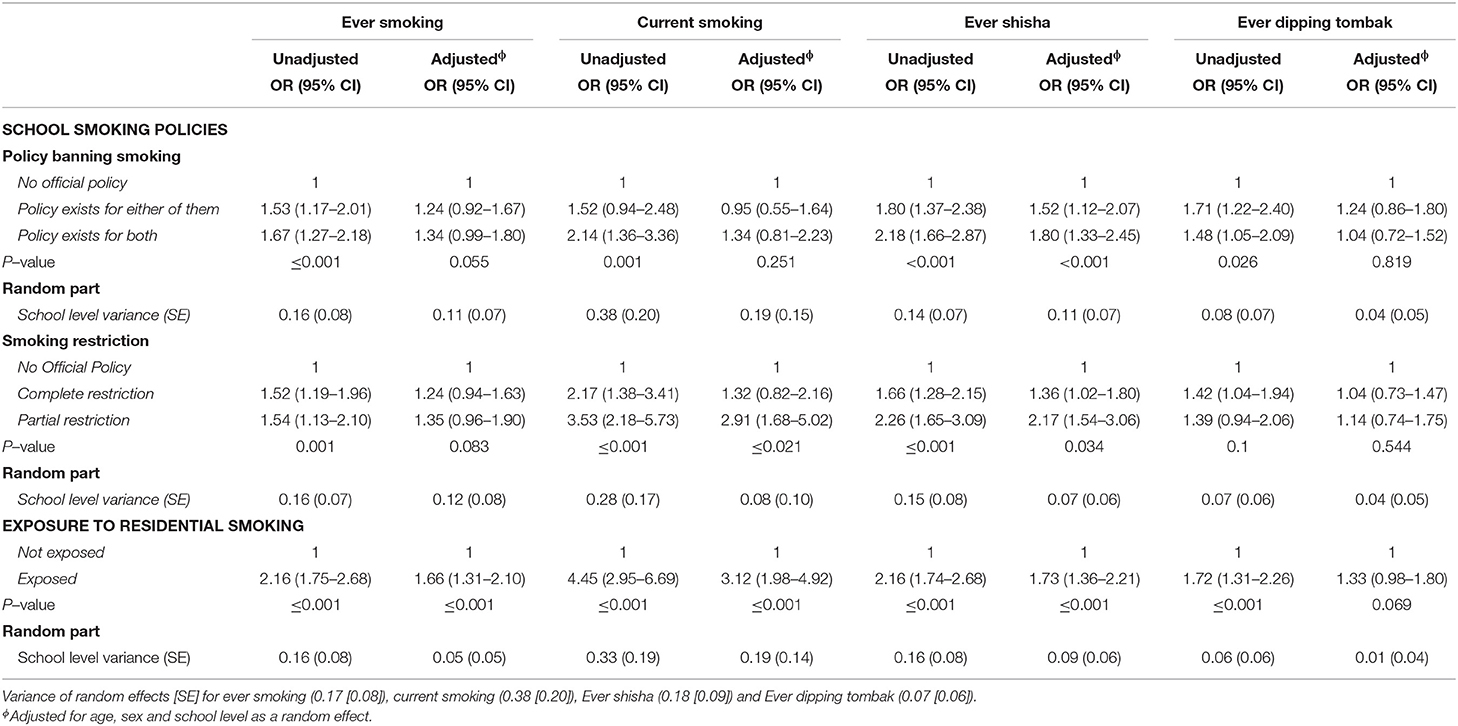

School smoking policy.

As indicated in Table 3 , the existence of policy was significantly associated with ever smoking and shisha use after adjusting for age and sex. Odds ratios declined but remained significant compared to non-smokers, with small reduction of school variance. Partial smoking restriction was significantly associated with increased risk of current-smoking (Adjusted OR (A-OR) 2.91), and shisha use (A-OR 2.17), with small reduction of school level variance. School policy and smoking restrictions appeared to be unrelated to dipping behavior.

Table 3 . Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for tobacco use by school smoking policies and exposure to residential smoking in unadjusted and adjusted models; adjusted for age, sex, and school level as random effects.

A third model was fit and further adjusted for school types and residential smoking as confounders in addition to age and sex. The adjusted odds ratio remained almost the same when adjusted for school types, but when adjusted for residential smoking, the odds ratio decreased and the results lost their significances. The results of this analysis were not presented in the tables. This may underestimate the importance of school factors influencing students' tobacco use ( 31 ).

Exposure to Residential Smoking

In the adjusted model, exposure to smoking during the last 7-days was significantly associated with increased risk of ever smoking (A-OR 1.66), current smoking (A-OR 3.12), and shisha use (A-OR 1.73), and marginally ( P -value 0.06) related to dipping tombak ( Table 3 ).

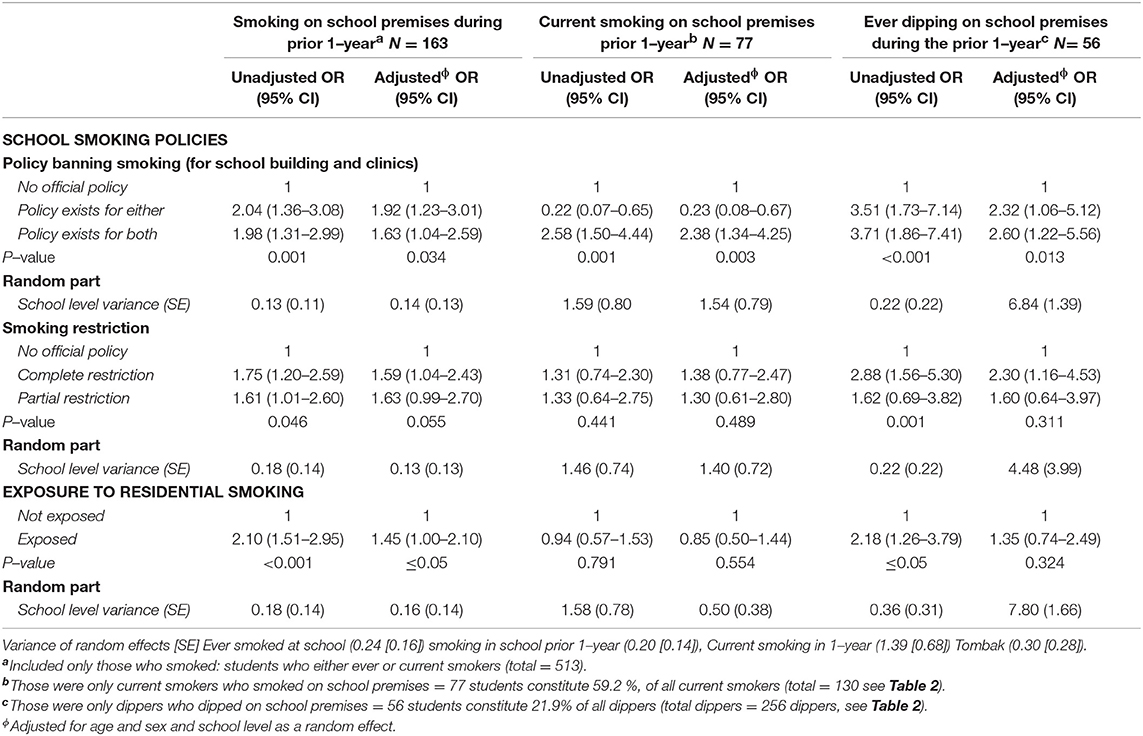

Smoking on School Premises

The results shown in Table 4 are consistent with the previous results of the multi-level analysis. The awareness of an official policy did not appear to stop students from dipping or smoking on school premises, when the students reported the existence of policies, the risk increased for tobacco use (A-OR 2.38, for current smoking and 2.60 for ever dipping) . Regarding smoking restriction, it was significant only with complete restriction.

Table 4 . Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for tobacco use on school premises during the prior 1–year by school smoking policies and exposure to residential smoking among smokers and tombak dippers; adjusted for age, sex, and school level as random effects.

The present study reveals new information about the pattern of tobacco use among Sudanese university students and its association with school anti-smoking policies. The study makes an important contribution to what is known about the tobacco habits of youth by including tombak dipping and shisha use in addition to cigarette smoking. No known study to date has been published in which the researcher compared these three types of tobacco use among youth or has considered the effect of school smoking policy on dipping tombak and/or using shisha and the effect of residential smoking on using different kinds of tobacco products.

Current smoking was observed in 8.3% of the Health Sciences students, compared to 13.7% among university students in Sudan in a study conducted in 2016 ( 32 ). Another study conducted in 2013 among 302 Sudanese Health Professional students from private schools ( 33 ) showed the prevalence of current smoking and ever smoking to be 9.6 and 26%, respectively, and 34.5% were exposed to residential smoking (compared to 40.8% of the present sample). Comparing the findings of current smoking from the three studies shows no significant reduction among current smoking in terms of policy measures, and strategic efforts to prohibit smoking among students during the period in between the three studies (2007, 2013, and 2016) do not appear to have been effective.

Regarding the students' reports about school policy, the results demonstrate a considerable diversity between schools. The kinds of tobacco product used were quite different among students. More than half of all students reported the non-existence of school policy (54%). Most of the tobacco users were aware of the existence of policy and the restriction of smoking in common areas and in school buildings. It would seem that tobacco users are more aware of school smoking policies than non-users, even though they may choose to ignore the policies.

With additional analysis, the awareness of existence of school policies diminished and lost its significant results except for shisha users. On the other hand, awareness of smoking restriction was significantly and reversely associated with increasing risk of current smokers and with shisha users. This implies either the policy was not well-enforced ( 26 ), or there was a lack of student commitment to school policy ( 34 ).

With respect to the shisha use category, shisha users were more aware of the policy existence and the restricted areas. That might be because it is inconvenient to use shisha inside a school compared to cigarette smoking and dipping. The size of the shisha, the strong smell of fruit-flavored tobacco, and the fact that shisha is usually smoked in groups ( 35 ) would collectively hinder the use of shisha inside the school. In addition, there is lack of literature about policy concerning shisha use ( 36 ). In contrast, the “dip” can be hidden behind the lips and remain hidden for several minutes ( 14 ), which makes it easier for dippers to dip inside schools. Unlike smoking cigarettes or using shisha, dippers were more aware of smoking and restriction zones only if they reported being dual users ( 37 ).

With regard to smoking on school premises, 31.8% of all smokers and 21.8% of dippers have smoked or dipped on school premises ( Table 4 , footnote). Specifically, more than half of the current smokers (59.2%) have smoked inside the school they attend ( Table 4 , footnote). Results of multi-level analysis showed that despite knowing the existence of a non-smoking policy, students continued to smoke and dip on school premises, meaning that the awareness of the policy had no effect on their smoking or dipping, or they knew that it was not vigorously enforced.

Students' reports about their school policy is quite ambiguous. Their responses varied greatly, despite the fact that they may be in the same schools ( 31 , 38 ). Awareness of the policy and enforcement are essential to help ensure compliance ( 39 ). Various researchers have shown that the relationship between school policies and students' -smoking are mixed ( 20 , 40 ). Some indicate a weak-to moderate relationship between policies and student smoking, while other studies indicate no effects ( 41 ). Other researchers suggest that changing a school environment represents a broader yet appropriate and effective factor in prevention and protection ( 26 , 42 ).

More than half of ever smokers and 44% of shisha users; at least on 1 day of the previous week, were exposed to smoking in places where they are living, more among older male students (55%). Those exposed to residential smoking were more susceptible to start smoking, and they were more than three times at risk to be current smokers and twice as likely to be shisha users ( 14 ). Exposure to residential smoking did not affect a student's risk of dipping tombak, and it was also not found to be related to smoking on school premises. Most researchers who examined smoking among young revealed that ever smokers initiated their smoking early in adolescence ( 43 , 44 ), raising a question of the possibility of exposure to residential smoking perhaps some time before getting into their current university. Therefore, it made it crucial, in the present study, to consider the exposure to residential smoking as one of the main factors behind starting to use cigarettes when students were already adults. Accordingly, this finding itself is an indicator of many other unmeasured influences on student tobacco use. Further research in the low- and middle-income countries is needed to explore other factors, possibly imitating friends ( 45 ) or socio-economic background ( 46 ), or exposure to smoking in places other than the places where they live.

Tombak dipping is a normative behavior among Sudanese. The product is cheap, easily available, and widely used. Some smokers have adopted it as an alternative to smoking tobacco ( 14 ). Results of the present study indicated that tombak is less used among Health Science students (16%) compared to the 45% prevalence of tombak among the adult population ( 47 ). This might be explained in that tombak is less prestigious among young university students and is less accepted, especially among females.

Strengths and Limitations

This study makes an important contribution to researches about school tobacco policies in Africa. The findings could be taken as a baseline for school policies in Sudan and other Sub-Saharan countries targeting the same group, although it was carried out in a country which is now two separate countries. Several factors may cause different students in different schools in different countries to experience the effect of tobacco use in different ways, but a baseline is important for the future researchers to measure the effect of changes over time. One of the most important strengths of the present study is that the researcher considered different kinds of tobacco products, and similarly assessed use of those products. By understanding the use of varied tobacco products and their associations with school policy, the results can be used to target future policy programs that address use of different kinds of tobacco products in the developing world and in establishing a school-based tobacco policy. Another important strength of the present study was the use of a standardized questionnaire for data collection; it was based on the international core questionnaire. The original questionnaire was translated by expert persons, piloted, and back-translated by an independent professional person who was not part of the first translation or the study to minimize bias and misunderstanding. More questions were also asked about local tobacco products. The overall response rate of school was 100%, and 68% for students, yet non-response bias might have affected the results. Some researchers have found that non-respondents are more likely to be smokers than respondents ( 48 ), the author does not expect that non-response rate (32%) of the students had a major role on influencing the results of this study.

The most important limitations of this study included its cross-sectional design ( 49 ); therefore, a causal relationship cannot be determined. For instance, from the findings obtained in this study, the direction of causality of the association between tobacco use by students and their attitudes toward anti-smoking policy was not clear. Longitudinal studies are required to make the direction of this kind of causality clear. The data for this study were only collected from third year Health Sciences Students; therefore, it cannot be assumed that the sample is representative of other students at the same age at other universities or in other academic disciplines of study. Other measures, such as school written policies from the schools, to validate the students' reports were not available. More information would be valuable in supporting the findings, since the official written policy and the students' perception of policy might be different. The data used in the present study were collected in 2007. To conduct another study; targeting the same study population would not be easy because the country has subsequently divided into two countries. However, findings from data collected among some Health Science students in the northern part of Sudan in 2013 and 2016 ( 32 , 33 ), showed that situation about tobacco use is worse than in 2007.

Conclusions

Despite the limitations, the results of this study provide important information as research about use of tobacco products continues. The present study was designed to examine the relationship between tobacco control activities and tobacco use prevalence among young adults, confirming the importance of continuous review of policies and prevention programs. Although school policies banning or restricting tobacco use seemed to be largely ignored, no specific elements with significant effects were found in the school context that would lead to specific suggestions for improvement of the policies. Yet, strategies for tobacco control must be extended to cover school, societal, and individual levels. From a research perspective, the high prevalence of tobacco use by the study population calls into question what other factors in the environment, including cultural norms, seem to promote smoking and result in such a high percentage of future health professional being tobacco users.

Recommendations

Based on the findings from this study, opportunities for schools to have a significant role in preventing tobacco use should be pursued. Further work is needed with emphasis on students' tobacco use attitudes and behavior for every form of tobacco product. More attention should be given to enforcement of school smoking policies, to help dissuade smoking initiation. Future researchers who use the questionnaire from this study in school settings should include a random sample of students from preparatory to finalist classes, representing a wider life span and geographical representation than in the present study. Researchers studying tobacco use and prevention should examine all major kinds of tobacco products, as the results here indicated that use of different types of tobacco is associated with different individual characteristics and environmental contexts. Different stages in a student's life should also be considered, including the socio-cultural background of the student, the school environment, residential and neighborhoods' smoking, and financial accessibility that might have effect on a student's initiating or continuing use of any kind of tobacco product.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

SE conceived the study, collected the data, conducted the analysis, drafted, and finalized the manuscript.

The data collection for this study was financially supported by the WHO and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), USA and Khartoum Ministry of Health. Part of the author's salary was been paid by grants from the Competitive Research Fund of Tampere University Hospital (9P041), the Doctoral Programs in Public Health, and University of Tampere, during the conduct of the study.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the Federal and Khartoum State Ministries of Health for their contribution to the successful implementation of the study fieldwork. My sincere thanks to my supervisor Prof. Arja Rimpela for her support and advice. I also wish to thank my former colleague Bright Nwaru, who assisted me with data management.

1. WHO Regional Office for Africa. The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: 10 Years of Implementation in the African Region (2015). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/164353/9789290232773_eng.pdf;jsessionid=7C3274962D21FF70AA7A2F14DAD186A4?sequence=1 (accessed April, 2019).

Google Scholar

2. World Health Organization. WHO Tobacco Fact Sheet (2017). Available online at: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco (accessed May, 2019).

3. Benjamin RM. Exposure to tobacco smoke causes immediate damage: a report of the surgeon general. Public Health Rep . (2011) 2:158. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600202

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Critchley JA, Unal B. Health effects associated with smokeless tobacco. A systematic review. Thorax . (2003) 5:435–43. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.5.435

5. Hyland A, Barnoya J, Corral J. Smoke-free air policies: past, present and future. Tobacco Control . (2012) 2:154–61. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050389

6. Chapman S, Freeman B. Markers of the renormalization of smoking and the tobacco industry. Tobacco Control. (2008) 1:25–31. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.021386

7. Abdullah A, Husten C. Promotion of smoking cessation in developing countries: a framework for urgent public health interventions. Thorax. (2004) 7:623–30. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.018820

8. Tumwine J. Implementation of the framework convention on tobacco control in Africa: current status of legislation. Int J Environ Res Public Health . (2011)11:4312–31. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8114312

9. Daniels K, Roman N. A descriptive study of the perceptions and behaviors of waterpipe use by university students in the Western Cape, South Africa. Tobacco Induced Dis . (2013) 1:4. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-11-4

10. Idris A, Warnakulasuriya K, Ibrahim Y, Nielsen R, Cooper D, Johnson N. Toombak-associated oral mucosal lesions in Sudanese show a low prevalence of epithelial dysplasia. J Oral Pathol Med . (1996) 5:239–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb01378.x

11. Pampel F. Tobacco use in sub-Sahara Africa: estimates from the demographic health surveys. Soc Sci Med . (2008) 8:1772–83. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.003

12. Mathers C, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med . (2006) 11:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442

13. World Health Organization. WHO A Policy Package to Reverse the Tobacco Epidemic (2008). Available online at: http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/mpower_english.pdf (accessed December 2018).

14. El-Amin E, Nwaru B, Ginawi I, Pisani P, Hakama M. The role of parents, friends and teachers in adolescents' cigarette smoking and tombak dipping in Sudan. Tobacco Control. (2011) 2:94–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.038091

15. Almahdi H, Åstrøm N, Ali R, Nasir E. School workers' knowledge, attitude and behaviour related to use of Toombak. A cross sectional study from Khartoum state, Sudan. BMC Oral Health . (2017) 1:160. doi: 10.1186/s12903-017-0460-8

16. Thomas RE, McLellan J, Perera R. School-based programs for preventing smoking. Eviden Based Child Health Cochrane Rev J . (2013) 5:1616–2040. doi: 10.1002/ebch.1937

17. Jackson CA, Henderson M, Frank JW, Haw SJ. An overview of prevention of multiple risk behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. J Public Health . (2012) 1:i31–40. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr113

18. Campbell R, Starkey F, Holliday J, Audrey S, Bloor M, Parry-Langdon N, et al. An informal school-based peer-led intervention for smoking prevention in adolescence (ASSIST): a cluster randomized trial. Lancet . (2008) 624:1595–602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60692-3