Warning: The NCBI web site requires JavaScript to function. more...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Lau F, Kuziemsky C, editors. Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet]. Victoria (BC): University of Victoria; 2017 Feb 27.

Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet].

Chapter 9 methods for literature reviews.

Guy Paré and Spyros Kitsiou .

9.1. Introduction

Literature reviews play a critical role in scholarship because science remains, first and foremost, a cumulative endeavour ( vom Brocke et al., 2009 ). As in any academic discipline, rigorous knowledge syntheses are becoming indispensable in keeping up with an exponentially growing eHealth literature, assisting practitioners, academics, and graduate students in finding, evaluating, and synthesizing the contents of many empirical and conceptual papers. Among other methods, literature reviews are essential for: (a) identifying what has been written on a subject or topic; (b) determining the extent to which a specific research area reveals any interpretable trends or patterns; (c) aggregating empirical findings related to a narrow research question to support evidence-based practice; (d) generating new frameworks and theories; and (e) identifying topics or questions requiring more investigation ( Paré, Trudel, Jaana, & Kitsiou, 2015 ).

Literature reviews can take two major forms. The most prevalent one is the “literature review” or “background” section within a journal paper or a chapter in a graduate thesis. This section synthesizes the extant literature and usually identifies the gaps in knowledge that the empirical study addresses ( Sylvester, Tate, & Johnstone, 2013 ). It may also provide a theoretical foundation for the proposed study, substantiate the presence of the research problem, justify the research as one that contributes something new to the cumulated knowledge, or validate the methods and approaches for the proposed study ( Hart, 1998 ; Levy & Ellis, 2006 ).

The second form of literature review, which is the focus of this chapter, constitutes an original and valuable work of research in and of itself ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Rather than providing a base for a researcher’s own work, it creates a solid starting point for all members of the community interested in a particular area or topic ( Mulrow, 1987 ). The so-called “review article” is a journal-length paper which has an overarching purpose to synthesize the literature in a field, without collecting or analyzing any primary data ( Green, Johnson, & Adams, 2006 ).

When appropriately conducted, review articles represent powerful information sources for practitioners looking for state-of-the art evidence to guide their decision-making and work practices ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Further, high-quality reviews become frequently cited pieces of work which researchers seek out as a first clear outline of the literature when undertaking empirical studies ( Cooper, 1988 ; Rowe, 2014 ). Scholars who track and gauge the impact of articles have found that review papers are cited and downloaded more often than any other type of published article ( Cronin, Ryan, & Coughlan, 2008 ; Montori, Wilczynski, Morgan, Haynes, & Hedges, 2003 ; Patsopoulos, Analatos, & Ioannidis, 2005 ). The reason for their popularity may be the fact that reading the review enables one to have an overview, if not a detailed knowledge of the area in question, as well as references to the most useful primary sources ( Cronin et al., 2008 ). Although they are not easy to conduct, the commitment to complete a review article provides a tremendous service to one’s academic community ( Paré et al., 2015 ; Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). Most, if not all, peer-reviewed journals in the fields of medical informatics publish review articles of some type.

The main objectives of this chapter are fourfold: (a) to provide an overview of the major steps and activities involved in conducting a stand-alone literature review; (b) to describe and contrast the different types of review articles that can contribute to the eHealth knowledge base; (c) to illustrate each review type with one or two examples from the eHealth literature; and (d) to provide a series of recommendations for prospective authors of review articles in this domain.

9.2. Overview of the Literature Review Process and Steps

As explained in Templier and Paré (2015) , there are six generic steps involved in conducting a review article:

- formulating the research question(s) and objective(s),

- searching the extant literature,

- screening for inclusion,

- assessing the quality of primary studies,

- extracting data, and

- analyzing data.

Although these steps are presented here in sequential order, one must keep in mind that the review process can be iterative and that many activities can be initiated during the planning stage and later refined during subsequent phases ( Finfgeld-Connett & Johnson, 2013 ; Kitchenham & Charters, 2007 ).

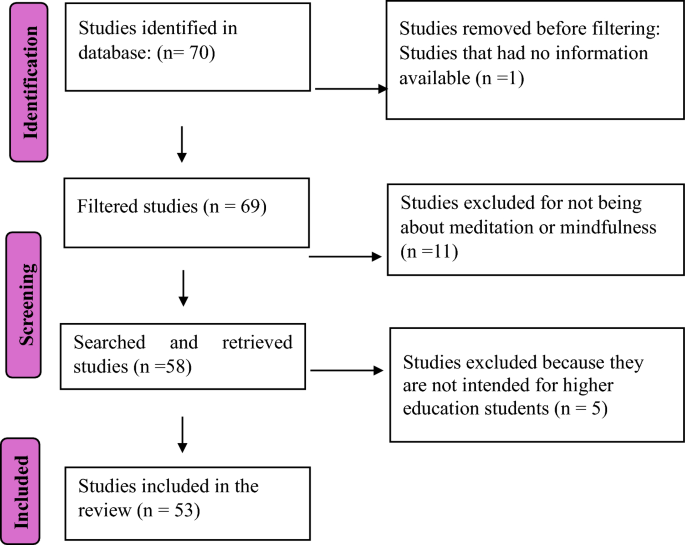

Formulating the research question(s) and objective(s): As a first step, members of the review team must appropriately justify the need for the review itself ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ), identify the review’s main objective(s) ( Okoli & Schabram, 2010 ), and define the concepts or variables at the heart of their synthesis ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ; Webster & Watson, 2002 ). Importantly, they also need to articulate the research question(s) they propose to investigate ( Kitchenham & Charters, 2007 ). In this regard, we concur with Jesson, Matheson, and Lacey (2011) that clearly articulated research questions are key ingredients that guide the entire review methodology; they underscore the type of information that is needed, inform the search for and selection of relevant literature, and guide or orient the subsequent analysis. Searching the extant literature: The next step consists of searching the literature and making decisions about the suitability of material to be considered in the review ( Cooper, 1988 ). There exist three main coverage strategies. First, exhaustive coverage means an effort is made to be as comprehensive as possible in order to ensure that all relevant studies, published and unpublished, are included in the review and, thus, conclusions are based on this all-inclusive knowledge base. The second type of coverage consists of presenting materials that are representative of most other works in a given field or area. Often authors who adopt this strategy will search for relevant articles in a small number of top-tier journals in a field ( Paré et al., 2015 ). In the third strategy, the review team concentrates on prior works that have been central or pivotal to a particular topic. This may include empirical studies or conceptual papers that initiated a line of investigation, changed how problems or questions were framed, introduced new methods or concepts, or engendered important debate ( Cooper, 1988 ). Screening for inclusion: The following step consists of evaluating the applicability of the material identified in the preceding step ( Levy & Ellis, 2006 ; vom Brocke et al., 2009 ). Once a group of potential studies has been identified, members of the review team must screen them to determine their relevance ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). A set of predetermined rules provides a basis for including or excluding certain studies. This exercise requires a significant investment on the part of researchers, who must ensure enhanced objectivity and avoid biases or mistakes. As discussed later in this chapter, for certain types of reviews there must be at least two independent reviewers involved in the screening process and a procedure to resolve disagreements must also be in place ( Liberati et al., 2009 ; Shea et al., 2009 ). Assessing the quality of primary studies: In addition to screening material for inclusion, members of the review team may need to assess the scientific quality of the selected studies, that is, appraise the rigour of the research design and methods. Such formal assessment, which is usually conducted independently by at least two coders, helps members of the review team refine which studies to include in the final sample, determine whether or not the differences in quality may affect their conclusions, or guide how they analyze the data and interpret the findings ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). Ascribing quality scores to each primary study or considering through domain-based evaluations which study components have or have not been designed and executed appropriately makes it possible to reflect on the extent to which the selected study addresses possible biases and maximizes validity ( Shea et al., 2009 ). Extracting data: The following step involves gathering or extracting applicable information from each primary study included in the sample and deciding what is relevant to the problem of interest ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ). Indeed, the type of data that should be recorded mainly depends on the initial research questions ( Okoli & Schabram, 2010 ). However, important information may also be gathered about how, when, where and by whom the primary study was conducted, the research design and methods, or qualitative/quantitative results ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ). Analyzing and synthesizing data : As a final step, members of the review team must collate, summarize, aggregate, organize, and compare the evidence extracted from the included studies. The extracted data must be presented in a meaningful way that suggests a new contribution to the extant literature ( Jesson et al., 2011 ). Webster and Watson (2002) warn researchers that literature reviews should be much more than lists of papers and should provide a coherent lens to make sense of extant knowledge on a given topic. There exist several methods and techniques for synthesizing quantitative (e.g., frequency analysis, meta-analysis) and qualitative (e.g., grounded theory, narrative analysis, meta-ethnography) evidence ( Dixon-Woods, Agarwal, Jones, Young, & Sutton, 2005 ; Thomas & Harden, 2008 ).

9.3. Types of Review Articles and Brief Illustrations

EHealth researchers have at their disposal a number of approaches and methods for making sense out of existing literature, all with the purpose of casting current research findings into historical contexts or explaining contradictions that might exist among a set of primary research studies conducted on a particular topic. Our classification scheme is largely inspired from Paré and colleagues’ (2015) typology. Below we present and illustrate those review types that we feel are central to the growth and development of the eHealth domain.

9.3.1. Narrative Reviews

The narrative review is the “traditional” way of reviewing the extant literature and is skewed towards a qualitative interpretation of prior knowledge ( Sylvester et al., 2013 ). Put simply, a narrative review attempts to summarize or synthesize what has been written on a particular topic but does not seek generalization or cumulative knowledge from what is reviewed ( Davies, 2000 ; Green et al., 2006 ). Instead, the review team often undertakes the task of accumulating and synthesizing the literature to demonstrate the value of a particular point of view ( Baumeister & Leary, 1997 ). As such, reviewers may selectively ignore or limit the attention paid to certain studies in order to make a point. In this rather unsystematic approach, the selection of information from primary articles is subjective, lacks explicit criteria for inclusion and can lead to biased interpretations or inferences ( Green et al., 2006 ). There are several narrative reviews in the particular eHealth domain, as in all fields, which follow such an unstructured approach ( Silva et al., 2015 ; Paul et al., 2015 ).

Despite these criticisms, this type of review can be very useful in gathering together a volume of literature in a specific subject area and synthesizing it. As mentioned above, its primary purpose is to provide the reader with a comprehensive background for understanding current knowledge and highlighting the significance of new research ( Cronin et al., 2008 ). Faculty like to use narrative reviews in the classroom because they are often more up to date than textbooks, provide a single source for students to reference, and expose students to peer-reviewed literature ( Green et al., 2006 ). For researchers, narrative reviews can inspire research ideas by identifying gaps or inconsistencies in a body of knowledge, thus helping researchers to determine research questions or formulate hypotheses. Importantly, narrative reviews can also be used as educational articles to bring practitioners up to date with certain topics of issues ( Green et al., 2006 ).

Recently, there have been several efforts to introduce more rigour in narrative reviews that will elucidate common pitfalls and bring changes into their publication standards. Information systems researchers, among others, have contributed to advancing knowledge on how to structure a “traditional” review. For instance, Levy and Ellis (2006) proposed a generic framework for conducting such reviews. Their model follows the systematic data processing approach comprised of three steps, namely: (a) literature search and screening; (b) data extraction and analysis; and (c) writing the literature review. They provide detailed and very helpful instructions on how to conduct each step of the review process. As another methodological contribution, vom Brocke et al. (2009) offered a series of guidelines for conducting literature reviews, with a particular focus on how to search and extract the relevant body of knowledge. Last, Bandara, Miskon, and Fielt (2011) proposed a structured, predefined and tool-supported method to identify primary studies within a feasible scope, extract relevant content from identified articles, synthesize and analyze the findings, and effectively write and present the results of the literature review. We highly recommend that prospective authors of narrative reviews consult these useful sources before embarking on their work.

Darlow and Wen (2015) provide a good example of a highly structured narrative review in the eHealth field. These authors synthesized published articles that describe the development process of mobile health (m-health) interventions for patients’ cancer care self-management. As in most narrative reviews, the scope of the research questions being investigated is broad: (a) how development of these systems are carried out; (b) which methods are used to investigate these systems; and (c) what conclusions can be drawn as a result of the development of these systems. To provide clear answers to these questions, a literature search was conducted on six electronic databases and Google Scholar . The search was performed using several terms and free text words, combining them in an appropriate manner. Four inclusion and three exclusion criteria were utilized during the screening process. Both authors independently reviewed each of the identified articles to determine eligibility and extract study information. A flow diagram shows the number of studies identified, screened, and included or excluded at each stage of study selection. In terms of contributions, this review provides a series of practical recommendations for m-health intervention development.

9.3.2. Descriptive or Mapping Reviews

The primary goal of a descriptive review is to determine the extent to which a body of knowledge in a particular research topic reveals any interpretable pattern or trend with respect to pre-existing propositions, theories, methodologies or findings ( King & He, 2005 ; Paré et al., 2015 ). In contrast with narrative reviews, descriptive reviews follow a systematic and transparent procedure, including searching, screening and classifying studies ( Petersen, Vakkalanka, & Kuzniarz, 2015 ). Indeed, structured search methods are used to form a representative sample of a larger group of published works ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Further, authors of descriptive reviews extract from each study certain characteristics of interest, such as publication year, research methods, data collection techniques, and direction or strength of research outcomes (e.g., positive, negative, or non-significant) in the form of frequency analysis to produce quantitative results ( Sylvester et al., 2013 ). In essence, each study included in a descriptive review is treated as the unit of analysis and the published literature as a whole provides a database from which the authors attempt to identify any interpretable trends or draw overall conclusions about the merits of existing conceptualizations, propositions, methods or findings ( Paré et al., 2015 ). In doing so, a descriptive review may claim that its findings represent the state of the art in a particular domain ( King & He, 2005 ).

In the fields of health sciences and medical informatics, reviews that focus on examining the range, nature and evolution of a topic area are described by Anderson, Allen, Peckham, and Goodwin (2008) as mapping reviews . Like descriptive reviews, the research questions are generic and usually relate to publication patterns and trends. There is no preconceived plan to systematically review all of the literature although this can be done. Instead, researchers often present studies that are representative of most works published in a particular area and they consider a specific time frame to be mapped.

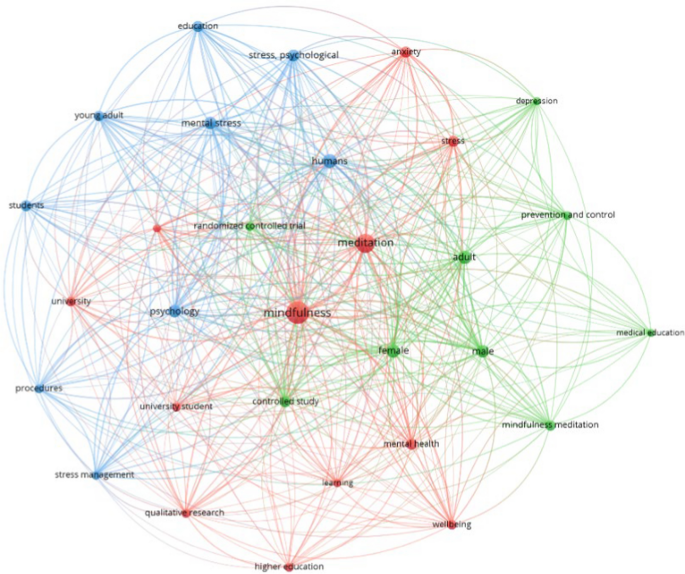

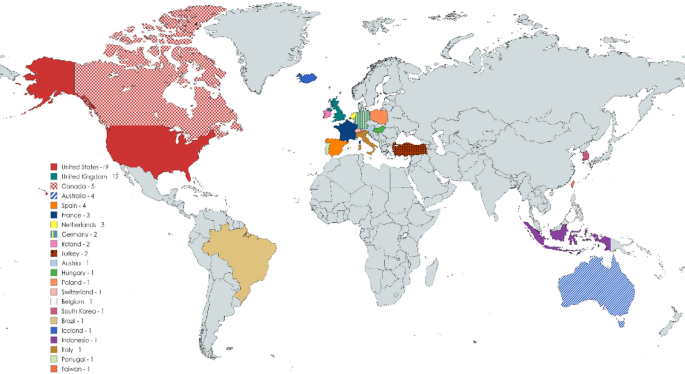

An example of this approach in the eHealth domain is offered by DeShazo, Lavallie, and Wolf (2009). The purpose of this descriptive or mapping review was to characterize publication trends in the medical informatics literature over a 20-year period (1987 to 2006). To achieve this ambitious objective, the authors performed a bibliometric analysis of medical informatics citations indexed in medline using publication trends, journal frequencies, impact factors, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) term frequencies, and characteristics of citations. Findings revealed that there were over 77,000 medical informatics articles published during the covered period in numerous journals and that the average annual growth rate was 12%. The MeSH term analysis also suggested a strong interdisciplinary trend. Finally, average impact scores increased over time with two notable growth periods. Overall, patterns in research outputs that seem to characterize the historic trends and current components of the field of medical informatics suggest it may be a maturing discipline (DeShazo et al., 2009).

9.3.3. Scoping Reviews

Scoping reviews attempt to provide an initial indication of the potential size and nature of the extant literature on an emergent topic (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Daudt, van Mossel, & Scott, 2013 ; Levac, Colquhoun, & O’Brien, 2010). A scoping review may be conducted to examine the extent, range and nature of research activities in a particular area, determine the value of undertaking a full systematic review (discussed next), or identify research gaps in the extant literature ( Paré et al., 2015 ). In line with their main objective, scoping reviews usually conclude with the presentation of a detailed research agenda for future works along with potential implications for both practice and research.

Unlike narrative and descriptive reviews, the whole point of scoping the field is to be as comprehensive as possible, including grey literature (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). Inclusion and exclusion criteria must be established to help researchers eliminate studies that are not aligned with the research questions. It is also recommended that at least two independent coders review abstracts yielded from the search strategy and then the full articles for study selection ( Daudt et al., 2013 ). The synthesized evidence from content or thematic analysis is relatively easy to present in tabular form (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Thomas & Harden, 2008 ).

One of the most highly cited scoping reviews in the eHealth domain was published by Archer, Fevrier-Thomas, Lokker, McKibbon, and Straus (2011) . These authors reviewed the existing literature on personal health record ( phr ) systems including design, functionality, implementation, applications, outcomes, and benefits. Seven databases were searched from 1985 to March 2010. Several search terms relating to phr s were used during this process. Two authors independently screened titles and abstracts to determine inclusion status. A second screen of full-text articles, again by two independent members of the research team, ensured that the studies described phr s. All in all, 130 articles met the criteria and their data were extracted manually into a database. The authors concluded that although there is a large amount of survey, observational, cohort/panel, and anecdotal evidence of phr benefits and satisfaction for patients, more research is needed to evaluate the results of phr implementations. Their in-depth analysis of the literature signalled that there is little solid evidence from randomized controlled trials or other studies through the use of phr s. Hence, they suggested that more research is needed that addresses the current lack of understanding of optimal functionality and usability of these systems, and how they can play a beneficial role in supporting patient self-management ( Archer et al., 2011 ).

9.3.4. Forms of Aggregative Reviews

Healthcare providers, practitioners, and policy-makers are nowadays overwhelmed with large volumes of information, including research-based evidence from numerous clinical trials and evaluation studies, assessing the effectiveness of health information technologies and interventions ( Ammenwerth & de Keizer, 2004 ; Deshazo et al., 2009 ). It is unrealistic to expect that all these disparate actors will have the time, skills, and necessary resources to identify the available evidence in the area of their expertise and consider it when making decisions. Systematic reviews that involve the rigorous application of scientific strategies aimed at limiting subjectivity and bias (i.e., systematic and random errors) can respond to this challenge.

Systematic reviews attempt to aggregate, appraise, and synthesize in a single source all empirical evidence that meet a set of previously specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a clearly formulated and often narrow research question on a particular topic of interest to support evidence-based practice ( Liberati et al., 2009 ). They adhere closely to explicit scientific principles ( Liberati et al., 2009 ) and rigorous methodological guidelines (Higgins & Green, 2008) aimed at reducing random and systematic errors that can lead to deviations from the truth in results or inferences. The use of explicit methods allows systematic reviews to aggregate a large body of research evidence, assess whether effects or relationships are in the same direction and of the same general magnitude, explain possible inconsistencies between study results, and determine the strength of the overall evidence for every outcome of interest based on the quality of included studies and the general consistency among them ( Cook, Mulrow, & Haynes, 1997 ). The main procedures of a systematic review involve:

- Formulating a review question and developing a search strategy based on explicit inclusion criteria for the identification of eligible studies (usually described in the context of a detailed review protocol).

- Searching for eligible studies using multiple databases and information sources, including grey literature sources, without any language restrictions.

- Selecting studies, extracting data, and assessing risk of bias in a duplicate manner using two independent reviewers to avoid random or systematic errors in the process.

- Analyzing data using quantitative or qualitative methods.

- Presenting results in summary of findings tables.

- Interpreting results and drawing conclusions.

Many systematic reviews, but not all, use statistical methods to combine the results of independent studies into a single quantitative estimate or summary effect size. Known as meta-analyses , these reviews use specific data extraction and statistical techniques (e.g., network, frequentist, or Bayesian meta-analyses) to calculate from each study by outcome of interest an effect size along with a confidence interval that reflects the degree of uncertainty behind the point estimate of effect ( Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009 ; Deeks, Higgins, & Altman, 2008 ). Subsequently, they use fixed or random-effects analysis models to combine the results of the included studies, assess statistical heterogeneity, and calculate a weighted average of the effect estimates from the different studies, taking into account their sample sizes. The summary effect size is a value that reflects the average magnitude of the intervention effect for a particular outcome of interest or, more generally, the strength of a relationship between two variables across all studies included in the systematic review. By statistically combining data from multiple studies, meta-analyses can create more precise and reliable estimates of intervention effects than those derived from individual studies alone, when these are examined independently as discrete sources of information.

The review by Gurol-Urganci, de Jongh, Vodopivec-Jamsek, Atun, and Car (2013) on the effects of mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at healthcare appointments is an illustrative example of a high-quality systematic review with meta-analysis. Missed appointments are a major cause of inefficiency in healthcare delivery with substantial monetary costs to health systems. These authors sought to assess whether mobile phone-based appointment reminders delivered through Short Message Service ( sms ) or Multimedia Messaging Service ( mms ) are effective in improving rates of patient attendance and reducing overall costs. To this end, they conducted a comprehensive search on multiple databases using highly sensitive search strategies without language or publication-type restrictions to identify all rct s that are eligible for inclusion. In order to minimize the risk of omitting eligible studies not captured by the original search, they supplemented all electronic searches with manual screening of trial registers and references contained in the included studies. Study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias assessments were performed independently by two coders using standardized methods to ensure consistency and to eliminate potential errors. Findings from eight rct s involving 6,615 participants were pooled into meta-analyses to calculate the magnitude of effects that mobile text message reminders have on the rate of attendance at healthcare appointments compared to no reminders and phone call reminders.

Meta-analyses are regarded as powerful tools for deriving meaningful conclusions. However, there are situations in which it is neither reasonable nor appropriate to pool studies together using meta-analytic methods simply because there is extensive clinical heterogeneity between the included studies or variation in measurement tools, comparisons, or outcomes of interest. In these cases, systematic reviews can use qualitative synthesis methods such as vote counting, content analysis, classification schemes and tabulations, as an alternative approach to narratively synthesize the results of the independent studies included in the review. This form of review is known as qualitative systematic review.

A rigorous example of one such review in the eHealth domain is presented by Mickan, Atherton, Roberts, Heneghan, and Tilson (2014) on the use of handheld computers by healthcare professionals and their impact on access to information and clinical decision-making. In line with the methodological guidelines for systematic reviews, these authors: (a) developed and registered with prospero ( www.crd.york.ac.uk/ prospero / ) an a priori review protocol; (b) conducted comprehensive searches for eligible studies using multiple databases and other supplementary strategies (e.g., forward searches); and (c) subsequently carried out study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias assessments in a duplicate manner to eliminate potential errors in the review process. Heterogeneity between the included studies in terms of reported outcomes and measures precluded the use of meta-analytic methods. To this end, the authors resorted to using narrative analysis and synthesis to describe the effectiveness of handheld computers on accessing information for clinical knowledge, adherence to safety and clinical quality guidelines, and diagnostic decision-making.

In recent years, the number of systematic reviews in the field of health informatics has increased considerably. Systematic reviews with discordant findings can cause great confusion and make it difficult for decision-makers to interpret the review-level evidence ( Moher, 2013 ). Therefore, there is a growing need for appraisal and synthesis of prior systematic reviews to ensure that decision-making is constantly informed by the best available accumulated evidence. Umbrella reviews , also known as overviews of systematic reviews, are tertiary types of evidence synthesis that aim to accomplish this; that is, they aim to compare and contrast findings from multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses ( Becker & Oxman, 2008 ). Umbrella reviews generally adhere to the same principles and rigorous methodological guidelines used in systematic reviews. However, the unit of analysis in umbrella reviews is the systematic review rather than the primary study ( Becker & Oxman, 2008 ). Unlike systematic reviews that have a narrow focus of inquiry, umbrella reviews focus on broader research topics for which there are several potential interventions ( Smith, Devane, Begley, & Clarke, 2011 ). A recent umbrella review on the effects of home telemonitoring interventions for patients with heart failure critically appraised, compared, and synthesized evidence from 15 systematic reviews to investigate which types of home telemonitoring technologies and forms of interventions are more effective in reducing mortality and hospital admissions ( Kitsiou, Paré, & Jaana, 2015 ).

9.3.5. Realist Reviews

Realist reviews are theory-driven interpretative reviews developed to inform, enhance, or supplement conventional systematic reviews by making sense of heterogeneous evidence about complex interventions applied in diverse contexts in a way that informs policy decision-making ( Greenhalgh, Wong, Westhorp, & Pawson, 2011 ). They originated from criticisms of positivist systematic reviews which centre on their “simplistic” underlying assumptions ( Oates, 2011 ). As explained above, systematic reviews seek to identify causation. Such logic is appropriate for fields like medicine and education where findings of randomized controlled trials can be aggregated to see whether a new treatment or intervention does improve outcomes. However, many argue that it is not possible to establish such direct causal links between interventions and outcomes in fields such as social policy, management, and information systems where for any intervention there is unlikely to be a regular or consistent outcome ( Oates, 2011 ; Pawson, 2006 ; Rousseau, Manning, & Denyer, 2008 ).

To circumvent these limitations, Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey, and Walshe (2005) have proposed a new approach for synthesizing knowledge that seeks to unpack the mechanism of how “complex interventions” work in particular contexts. The basic research question — what works? — which is usually associated with systematic reviews changes to: what is it about this intervention that works, for whom, in what circumstances, in what respects and why? Realist reviews have no particular preference for either quantitative or qualitative evidence. As a theory-building approach, a realist review usually starts by articulating likely underlying mechanisms and then scrutinizes available evidence to find out whether and where these mechanisms are applicable ( Shepperd et al., 2009 ). Primary studies found in the extant literature are viewed as case studies which can test and modify the initial theories ( Rousseau et al., 2008 ).

The main objective pursued in the realist review conducted by Otte-Trojel, de Bont, Rundall, and van de Klundert (2014) was to examine how patient portals contribute to health service delivery and patient outcomes. The specific goals were to investigate how outcomes are produced and, most importantly, how variations in outcomes can be explained. The research team started with an exploratory review of background documents and research studies to identify ways in which patient portals may contribute to health service delivery and patient outcomes. The authors identified six main ways which represent “educated guesses” to be tested against the data in the evaluation studies. These studies were identified through a formal and systematic search in four databases between 2003 and 2013. Two members of the research team selected the articles using a pre-established list of inclusion and exclusion criteria and following a two-step procedure. The authors then extracted data from the selected articles and created several tables, one for each outcome category. They organized information to bring forward those mechanisms where patient portals contribute to outcomes and the variation in outcomes across different contexts.

9.3.6. Critical Reviews

Lastly, critical reviews aim to provide a critical evaluation and interpretive analysis of existing literature on a particular topic of interest to reveal strengths, weaknesses, contradictions, controversies, inconsistencies, and/or other important issues with respect to theories, hypotheses, research methods or results ( Baumeister & Leary, 1997 ; Kirkevold, 1997 ). Unlike other review types, critical reviews attempt to take a reflective account of the research that has been done in a particular area of interest, and assess its credibility by using appraisal instruments or critical interpretive methods. In this way, critical reviews attempt to constructively inform other scholars about the weaknesses of prior research and strengthen knowledge development by giving focus and direction to studies for further improvement ( Kirkevold, 1997 ).

Kitsiou, Paré, and Jaana (2013) provide an example of a critical review that assessed the methodological quality of prior systematic reviews of home telemonitoring studies for chronic patients. The authors conducted a comprehensive search on multiple databases to identify eligible reviews and subsequently used a validated instrument to conduct an in-depth quality appraisal. Results indicate that the majority of systematic reviews in this particular area suffer from important methodological flaws and biases that impair their internal validity and limit their usefulness for clinical and decision-making purposes. To this end, they provide a number of recommendations to strengthen knowledge development towards improving the design and execution of future reviews on home telemonitoring.

9.4. Summary

Table 9.1 outlines the main types of literature reviews that were described in the previous sub-sections and summarizes the main characteristics that distinguish one review type from another. It also includes key references to methodological guidelines and useful sources that can be used by eHealth scholars and researchers for planning and developing reviews.

Typology of Literature Reviews (adapted from Paré et al., 2015).

As shown in Table 9.1 , each review type addresses different kinds of research questions or objectives, which subsequently define and dictate the methods and approaches that need to be used to achieve the overarching goal(s) of the review. For example, in the case of narrative reviews, there is greater flexibility in searching and synthesizing articles ( Green et al., 2006 ). Researchers are often relatively free to use a diversity of approaches to search, identify, and select relevant scientific articles, describe their operational characteristics, present how the individual studies fit together, and formulate conclusions. On the other hand, systematic reviews are characterized by their high level of systematicity, rigour, and use of explicit methods, based on an “a priori” review plan that aims to minimize bias in the analysis and synthesis process (Higgins & Green, 2008). Some reviews are exploratory in nature (e.g., scoping/mapping reviews), whereas others may be conducted to discover patterns (e.g., descriptive reviews) or involve a synthesis approach that may include the critical analysis of prior research ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Hence, in order to select the most appropriate type of review, it is critical to know before embarking on a review project, why the research synthesis is conducted and what type of methods are best aligned with the pursued goals.

9.5. Concluding Remarks

In light of the increased use of evidence-based practice and research generating stronger evidence ( Grady et al., 2011 ; Lyden et al., 2013 ), review articles have become essential tools for summarizing, synthesizing, integrating or critically appraising prior knowledge in the eHealth field. As mentioned earlier, when rigorously conducted review articles represent powerful information sources for eHealth scholars and practitioners looking for state-of-the-art evidence. The typology of literature reviews we used herein will allow eHealth researchers, graduate students and practitioners to gain a better understanding of the similarities and differences between review types.

We must stress that this classification scheme does not privilege any specific type of review as being of higher quality than another ( Paré et al., 2015 ). As explained above, each type of review has its own strengths and limitations. Having said that, we realize that the methodological rigour of any review — be it qualitative, quantitative or mixed — is a critical aspect that should be considered seriously by prospective authors. In the present context, the notion of rigour refers to the reliability and validity of the review process described in section 9.2. For one thing, reliability is related to the reproducibility of the review process and steps, which is facilitated by a comprehensive documentation of the literature search process, extraction, coding and analysis performed in the review. Whether the search is comprehensive or not, whether it involves a methodical approach for data extraction and synthesis or not, it is important that the review documents in an explicit and transparent manner the steps and approach that were used in the process of its development. Next, validity characterizes the degree to which the review process was conducted appropriately. It goes beyond documentation and reflects decisions related to the selection of the sources, the search terms used, the period of time covered, the articles selected in the search, and the application of backward and forward searches ( vom Brocke et al., 2009 ). In short, the rigour of any review article is reflected by the explicitness of its methods (i.e., transparency) and the soundness of the approach used. We refer those interested in the concepts of rigour and quality to the work of Templier and Paré (2015) which offers a detailed set of methodological guidelines for conducting and evaluating various types of review articles.

To conclude, our main objective in this chapter was to demystify the various types of literature reviews that are central to the continuous development of the eHealth field. It is our hope that our descriptive account will serve as a valuable source for those conducting, evaluating or using reviews in this important and growing domain.

- Ammenwerth E., de Keizer N. An inventory of evaluation studies of information technology in health care. Trends in evaluation research, 1982-2002. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2004; 44 (1):44–56. [ PubMed : 15778794 ]

- Anderson S., Allen P., Peckham S., Goodwin N. Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2008; 6 (7):1–12. [ PMC free article : PMC2500008 ] [ PubMed : 18613961 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Archer N., Fevrier-Thomas U., Lokker C., McKibbon K. A., Straus S.E. Personal health records: a scoping review. Journal of American Medical Informatics Association. 2011; 18 (4):515–522. [ PMC free article : PMC3128401 ] [ PubMed : 21672914 ]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005; 8 (1):19–32.

- A systematic, tool-supported method for conducting literature reviews in information systems. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 19th European Conference on Information Systems ( ecis 2011); June 9 to 11; Helsinki, Finland. 2011.

- Baumeister R. F., Leary M.R. Writing narrative literature reviews. Review of General Psychology. 1997; 1 (3):311–320.

- Becker L. A., Oxman A.D. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Higgins J. P. T., Green S., editors. Hoboken, nj : John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2008. Overviews of reviews; pp. 607–631.

- Borenstein M., Hedges L., Higgins J., Rothstein H. Introduction to meta-analysis. Hoboken, nj : John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2009.

- Cook D. J., Mulrow C. D., Haynes B. Systematic reviews: Synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997; 126 (5):376–380. [ PubMed : 9054282 ]

- Cooper H., Hedges L.V. In: The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. 2nd ed. Cooper H., Hedges L. V., Valentine J. C., editors. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2009. Research synthesis as a scientific process; pp. 3–17.

- Cooper H. M. Organizing knowledge syntheses: A taxonomy of literature reviews. Knowledge in Society. 1988; 1 (1):104–126.

- Cronin P., Ryan F., Coughlan M. Undertaking a literature review: a step-by-step approach. British Journal of Nursing. 2008; 17 (1):38–43. [ PubMed : 18399395 ]

- Darlow S., Wen K.Y. Development testing of mobile health interventions for cancer patient self-management: A review. Health Informatics Journal. 2015 (online before print). [ PubMed : 25916831 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Daudt H. M., van Mossel C., Scott S.J. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. bmc Medical Research Methodology. 2013; 13 :48. [ PMC free article : PMC3614526 ] [ PubMed : 23522333 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Davies P. The relevance of systematic reviews to educational policy and practice. Oxford Review of Education. 2000; 26 (3-4):365–378.

- Deeks J. J., Higgins J. P. T., Altman D.G. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Higgins J. P. T., Green S., editors. Hoboken, nj : John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2008. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses; pp. 243–296.

- Deshazo J. P., Lavallie D. L., Wolf F.M. Publication trends in the medical informatics literature: 20 years of “Medical Informatics” in mesh . bmc Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2009; 9 :7. [ PMC free article : PMC2652453 ] [ PubMed : 19159472 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dixon-Woods M., Agarwal S., Jones D., Young B., Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2005; 10 (1):45–53. [ PubMed : 15667704 ]

- Finfgeld-Connett D., Johnson E.D. Literature search strategies for conducting knowledge-building and theory-generating qualitative systematic reviews. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2013; 69 (1):194–204. [ PMC free article : PMC3424349 ] [ PubMed : 22591030 ]

- Grady B., Myers K. M., Nelson E. L., Belz N., Bennett L., Carnahan L. … Guidelines Working Group. Evidence-based practice for telemental health. Telemedicine Journal and E Health. 2011; 17 (2):131–148. [ PubMed : 21385026 ]

- Green B. N., Johnson C. D., Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine. 2006; 5 (3):101–117. [ PMC free article : PMC2647067 ] [ PubMed : 19674681 ]

- Greenhalgh T., Wong G., Westhorp G., Pawson R. Protocol–realist and meta-narrative evidence synthesis: evolving standards ( rameses ). bmc Medical Research Methodology. 2011; 11 :115. [ PMC free article : PMC3173389 ] [ PubMed : 21843376 ]

- Gurol-Urganci I., de Jongh T., Vodopivec-Jamsek V., Atun R., Car J. Mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at healthcare appointments. Cochrane Database System Review. 2013; 12 cd 007458. [ PMC free article : PMC6485985 ] [ PubMed : 24310741 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hart C. Doing a literature review: Releasing the social science research imagination. London: SAGE Publications; 1998.

- Higgins J. P. T., Green S., editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: Cochrane book series. Hoboken, nj : Wiley-Blackwell; 2008.

- Jesson J., Matheson L., Lacey F.M. Doing your literature review: traditional and systematic techniques. Los Angeles & London: SAGE Publications; 2011.

- King W. R., He J. Understanding the role and methods of meta-analysis in IS research. Communications of the Association for Information Systems. 2005; 16 :1.

- Kirkevold M. Integrative nursing research — an important strategy to further the development of nursing science and nursing practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997; 25 (5):977–984. [ PubMed : 9147203 ]

- Kitchenham B., Charters S. ebse Technical Report Version 2.3. Keele & Durham. uk : Keele University & University of Durham; 2007. Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering.

- Kitsiou S., Paré G., Jaana M. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of home telemonitoring interventions for patients with chronic diseases: a critical assessment of their methodological quality. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2013; 15 (7):e150. [ PMC free article : PMC3785977 ] [ PubMed : 23880072 ]

- Kitsiou S., Paré G., Jaana M. Effects of home telemonitoring interventions on patients with chronic heart failure: an overview of systematic reviews. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2015; 17 (3):e63. [ PMC free article : PMC4376138 ] [ PubMed : 25768664 ]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O’Brien K. K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science. 2010; 5 (1):69. [ PMC free article : PMC2954944 ] [ PubMed : 20854677 ]

- Levy Y., Ellis T.J. A systems approach to conduct an effective literature review in support of information systems research. Informing Science. 2006; 9 :181–211.

- Liberati A., Altman D. G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P. C., Ioannidis J. P. A. et al. Moher D. The prisma statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009; 151 (4):W-65. [ PubMed : 19622512 ]

- Lyden J. R., Zickmund S. L., Bhargava T. D., Bryce C. L., Conroy M. B., Fischer G. S. et al. McTigue K. M. Implementing health information technology in a patient-centered manner: Patient experiences with an online evidence-based lifestyle intervention. Journal for Healthcare Quality. 2013; 35 (5):47–57. [ PubMed : 24004039 ]

- Mickan S., Atherton H., Roberts N. W., Heneghan C., Tilson J.K. Use of handheld computers in clinical practice: a systematic review. bmc Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2014; 14 :56. [ PMC free article : PMC4099138 ] [ PubMed : 24998515 ]

- Moher D. The problem of duplicate systematic reviews. British Medical Journal. 2013; 347 (5040) [ PubMed : 23945367 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Montori V. M., Wilczynski N. L., Morgan D., Haynes R. B., Hedges T. Systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study of location and citation counts. bmc Medicine. 2003; 1 :2. [ PMC free article : PMC281591 ] [ PubMed : 14633274 ]

- Mulrow C. D. The medical review article: state of the science. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1987; 106 (3):485–488. [ PubMed : 3813259 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Evidence-based information systems: A decade later. Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems ; 2011. Retrieved from http://aisel .aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent .cgi?article =1221&context =ecis2011 .

- Okoli C., Schabram K. A guide to conducting a systematic literature review of information systems research. ssrn Electronic Journal. 2010

- Otte-Trojel T., de Bont A., Rundall T. G., van de Klundert J. How outcomes are achieved through patient portals: a realist review. Journal of American Medical Informatics Association. 2014; 21 (4):751–757. [ PMC free article : PMC4078283 ] [ PubMed : 24503882 ]

- Paré G., Trudel M.-C., Jaana M., Kitsiou S. Synthesizing information systems knowledge: A typology of literature reviews. Information & Management. 2015; 52 (2):183–199.

- Patsopoulos N. A., Analatos A. A., Ioannidis J.P. A. Relative citation impact of various study designs in the health sciences. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005; 293 (19):2362–2366. [ PubMed : 15900006 ]

- Paul M. M., Greene C. M., Newton-Dame R., Thorpe L. E., Perlman S. E., McVeigh K. H., Gourevitch M.N. The state of population health surveillance using electronic health records: A narrative review. Population Health Management. 2015; 18 (3):209–216. [ PubMed : 25608033 ]

- Pawson R. Evidence-based policy: a realist perspective. London: SAGE Publications; 2006.

- Pawson R., Greenhalgh T., Harvey G., Walshe K. Realist review—a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 2005; 10 (Suppl 1):21–34. [ PubMed : 16053581 ]

- Petersen K., Vakkalanka S., Kuzniarz L. Guidelines for conducting systematic mapping studies in software engineering: An update. Information and Software Technology. 2015; 64 :1–18.

- Petticrew M., Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. Malden, ma : Blackwell Publishing Co; 2006.

- Rousseau D. M., Manning J., Denyer D. Evidence in management and organizational science: Assembling the field’s full weight of scientific knowledge through syntheses. The Academy of Management Annals. 2008; 2 (1):475–515.

- Rowe F. What literature review is not: diversity, boundaries and recommendations. European Journal of Information Systems. 2014; 23 (3):241–255.

- Shea B. J., Hamel C., Wells G. A., Bouter L. M., Kristjansson E., Grimshaw J. et al. Boers M. amstar is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009; 62 (10):1013–1020. [ PubMed : 19230606 ]

- Shepperd S., Lewin S., Straus S., Clarke M., Eccles M. P., Fitzpatrick R. et al. Sheikh A. Can we systematically review studies that evaluate complex interventions? PLoS Medicine. 2009; 6 (8):e1000086. [ PMC free article : PMC2717209 ] [ PubMed : 19668360 ]

- Silva B. M., Rodrigues J. J., de la Torre Díez I., López-Coronado M., Saleem K. Mobile-health: A review of current state in 2015. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2015; 56 :265–272. [ PubMed : 26071682 ]

- Smith V., Devane D., Begley C., Clarke M. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. bmc Medical Research Methodology. 2011; 11 (1):15. [ PMC free article : PMC3039637 ] [ PubMed : 21291558 ]

- Sylvester A., Tate M., Johnstone D. Beyond synthesis: re-presenting heterogeneous research literature. Behaviour & Information Technology. 2013; 32 (12):1199–1215.

- Templier M., Paré G. A framework for guiding and evaluating literature reviews. Communications of the Association for Information Systems. 2015; 37 (6):112–137.

- Thomas J., Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. bmc Medical Research Methodology. 2008; 8 (1):45. [ PMC free article : PMC2478656 ] [ PubMed : 18616818 ]

- Reconstructing the giant: on the importance of rigour in documenting the literature search process. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 17th European Conference on Information Systems ( ecis 2009); Verona, Italy. 2009.

- Webster J., Watson R.T. Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. Management Information Systems Quarterly. 2002; 26 (2):11.

- Whitlock E. P., Lin J. S., Chou R., Shekelle P., Robinson K.A. Using existing systematic reviews in complex systematic reviews. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008; 148 (10):776–782. [ PubMed : 18490690 ]

This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons License, Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0): see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

- Cite this Page Paré G, Kitsiou S. Chapter 9 Methods for Literature Reviews. In: Lau F, Kuziemsky C, editors. Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet]. Victoria (BC): University of Victoria; 2017 Feb 27.

- PDF version of this title (4.5M)

In this Page

- Introduction

- Overview of the Literature Review Process and Steps

- Types of Review Articles and Brief Illustrations

- Concluding Remarks

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Recent Activity

- Chapter 9 Methods for Literature Reviews - Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Ev... Chapter 9 Methods for Literature Reviews - Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Ask the publishers to restore access to 500,000+ books.

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Systematic approaches to a successful literature review

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

2 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station33.cebu on July 11, 2023

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 73, Issue 10

- The road to a world-unified approach to the management of patients with gastric intestinal metaplasia: a review of current guidelines

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0121-6850 Mario Dinis-Ribeiro 1 , 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2049-9959 Shailja Shah 3 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5964-7579 Hashem El-Serag 4 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9137-2779 Matthew Banks 5 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3029-9272 Noriya Uedo 6 ,

- Hisao Tajiri 7 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8721-7696 Luiz Gonzaga Coelho 8 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2691-7522 Diogo Libanio 1 , 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9503-8639 Edith Lahner 9 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4997-4098 Antonio Rollan 10 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2282-0248 Jing-Yuan Fang 11 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4518-8591 Leticia Moreira 12 , 13 ,

- Jan Bornschein 14 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8439-9036 Peter Malfertheiner 15 ,

- Ernst J Kuipers 15 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0011-3924 Emad M El-Omar 16

- 1 Department of Gastroenterology , Porto Comprehensive Cancer Center & RISE@CI-IPO, University of Porto , Porto , Portugal

- 2 MEDCIDS (Department of Community Medicine, Health Information, and Decision) , University of Porto , Porto , Portugal

- 3 Division of Gastroenterology , University of California and Jennifer Moreno Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System , San Diego , California , USA

- 4 Gastroenterology and Hepatology , Baylor College of Medicine , Houston , Texas , USA

- 5 University College London Hospital , University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust , London , UK

- 6 Gastrointestinal Oncology , Osaka International Cancer Institute , Osaka , Japan

- 7 Endoscopy , The Jikei University School of Medicine , Tokyo , Japan

- 8 Instituto Alfa de Gastrenterologia , Hospital das Clínicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais , Belo Horizonte , Brazil

- 9 Department of Medical-Surgical Sciences and Translational Medicine , Sant'Andrea Hospital , Rome , Italy

- 10 Facultad de Medicina Clinica Alemana-Universidad del Desarrollo , Santiago , Chile

- 11 Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology , Shanghai Institute of Digestive Disease , Shanghai , China

- 12 Gastroenterology , Hospital Clinic de Barcelona , Barcelona , Spain

- 13 Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBEREHD) , Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS) , Barcelona , Spain

- 14 MRC Translational Immune Discovery Unit , MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, John Radcliffe Hospital, University of Oxford , Oxford , UK

- 15 Medical Department II , LMU University Clinic , München , Germany

- 16 UNSW Microbiome Research Centre , University of New South Wales , Sydney , New South Wales , Australia

- Correspondence to Professor Mario Dinis-Ribeiro, Department of Gastroenterology, RISE—Health Research Network, Porto, 4200-072, Portugal; mario.ribeiro{at}ipoporto.min-saude.pt

Objective During the last decade, the management of gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM) has been addressed by several distinct international evidence-based guidelines. In this review, we aimed to synthesise these guidelines and provide clinicians with a global perspective of the current recommendations for managing patients with GIM, as well as highlight evidence gaps that need to be addressed with future research.

Design We conducted a systematic review of the literature for guidelines and consensus statements published between January 2010 and February 2023 that address the diagnosis and management of GIM.

Results From 426 manuscripts identified, 16 guidelines were assessed. There was consistency across guidelines regarding the purpose of endoscopic surveillance of GIM, which is to identify prevalent neoplastic lesions and stage gastric preneoplastic conditions. The guidelines also agreed that only patients with high-risk GIM phenotypes (eg, corpus-extended GIM, OLGIM stages III/IV, incomplete GIM subtype), persistent refractory Helicobacter pylori infection or first-degree family history of gastric cancer should undergo regular-interval endoscopic surveillance. In contrast, low-risk phenotypes, which comprise most patients with GIM, do not require surveillance. Not all guidelines are aligned on histological staging systems. If surveillance is indicated, most guidelines recommend a 3-year interval, but there is some variability. All guidelines recommend H. pylori eradication as the only non-endoscopic intervention for gastric cancer prevention, while some offer additional recommendations regarding lifestyle modifications. While most guidelines allude to the importance of high-quality endoscopy for endoscopic surveillance, few detail important metrics apart from stating that a systematic gastric biopsy protocol should be followed. Notably, most guidelines comment on the role of endoscopy for gastric cancer screening and detection of gastric precancerous conditions, but with high heterogeneity, limited guidance regarding implementation, and lack of robust evidence.

Conclusion Despite heterogeneous populations and practices, international guidelines are generally aligned on the importance of GIM as a precancerous condition and the need for a risk-stratified approach to endoscopic surveillance, as well as H. pylori eradication when present. There is room for harmonisation of guidelines regarding (1) which populations merit index endoscopic screening for gastric cancer and GIM detection/staging; (2) objective metrics for high-quality endoscopy; (3) consensus on the need for histological staging and (4) non-endoscopic interventions for gastric cancer prevention apart from H. pylori eradication alone. Robust studies, ideally in the form of randomised trials, are needed to bridge the ample evidence gaps that exist.

- surveillance

- gastric carcinoma

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. All data analysed are available in proper databases depending on publisher.

https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2024-333029

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC