- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Lessons from Toyota’s Long Drive

- Thomas A. Stewart and Anand P. Raman

As Toyota becomes the world’s biggest automaker, the company finds its much-heralded ways of managing for the long term to be more important—and under greater pressure—than ever before.

Reprint: R0707E

Last December the Toyota Motor Corporation officially forecast that it would sell 9.34 million cars in 2007—which could make it the world’s largest automaker. However, rapid growth and globalization have created many pressures for the company, and the strain of success is already beginning to show. Two HBR editors interviewed Toyota’s president, Katsuaki Watanabe, and several top executives to learn about the strategies they’re developing to cope in the future.

For well over a decade, J.D. Power and other research firms have consistently rated Toyotas among the top automobiles for quality, reliability, and durability. But in 2006 a series of problems with its cars threatened to sully the company’s reputation. What’s more, speedy expansion to meet demand and the struggle to keep pace with technological change have combined to challenge Toyota’s grand ambitions and its famed “Toyota Way.”

For Watanabe, being number one means “being the best in the world in terms of quality.” If Toyota’s quality continues to improve, he says, volume and revenues will follow. If problems arise from overstretching, he wants them made visible, because then his people will “rack their brains” to solve them—and if that means postponing growth, so be it.

Toyota’s long-term strategy involves developing both global and regional car models in order to compete worldwide with a full line of products. Watanabe aims to achieve his goals through a combination of kaizen (“continuous improvement”) and kakushin (“radical innovation”). One of his visions for the future is a “dream car”: a vehicle that cleans the air, prevents accidents, promotes health, evokes excitement, and can drive around the world on a single tank of gas.

Partner Center

Welcome to the MIT CISR website!

This site uses cookies. Review our Privacy Statement.

Digital in the Driver’s Seat: Accelerating Toyota’s Transformation to Mobility Services

An in-depth description of a firm’s approach to an IT management issue (intended for MBA and executive education)

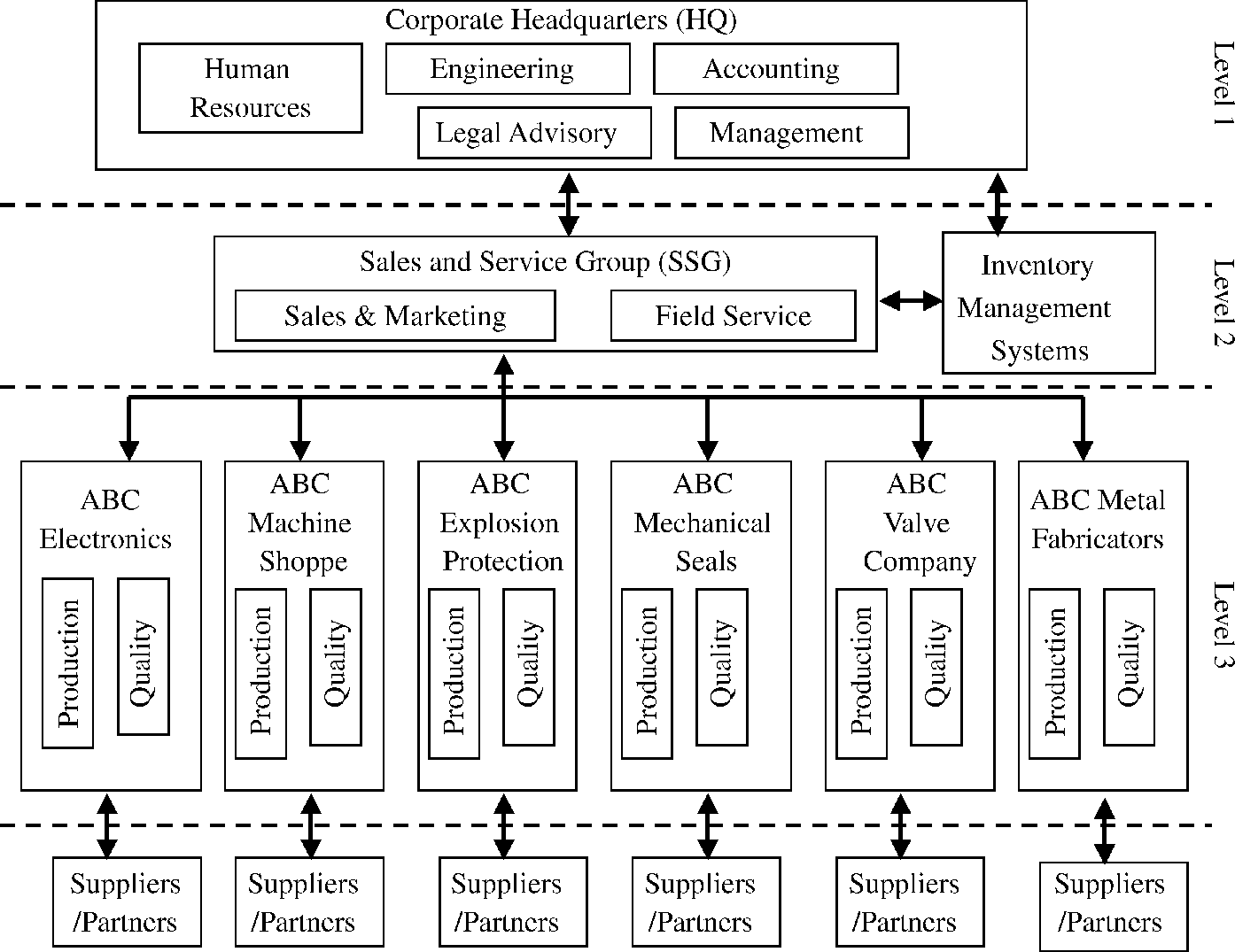

In 2020 Toyota Motor Corporation (TMC) was the world’s top-selling car manufacturer. Despite this, the company was being driven to excel further in response to changing consumer expectations, technological developments, and new kinds of entrants into the automotive industry. Toyota’s leaders sought to accelerate the company’s culture of incremental innovation and realize a bold new future centered on mobility services. They pursued this by launching Toyota Connected, a new organization with its own decision rights and ways of working and a mandate to create new digital offerings for Toyota. In parallel, a new division within Toyota Motor North America called Connected Technologies facilitated the company-wide diffusion and commercialization of the offerings Toyota Connected created. This case describes what it took to empower the small, independent, agile Toyota Connected and how the entity collaborated with Connected Technologies to design and scale new digital offerings and new ways of working for TMC globally.

Access More Research!

Any registered, logged-in user of the website can read many MIT CISR Working Papers in the webpage from 90 days after publication, plus download a PDF of the publication. Employees of MIT CISR members organizations get access to additional content.

Related Publications

Research Briefing

Digital disruption without organizational upheaval.

Working Paper: Case Study

Digital innovation at toyota motor north america: revamping the role of it.

Designed for Digital: How to Architect Your Business for Sustained Success

About the Authors

Nick van der Meulen, Research Scientist, MIT Center for Information Systems Research (CISR)

John G. Mooney, Professor, Pepperdine Graziadio Business School

Cynthia M. Beath, Professor Emerita, University of Texas and Research Collaborator, MIT CISR

Mit center for information systems research (cisr).

Founded in 1974 and grounded in MIT's tradition of combining academic knowledge and practical purpose, MIT CISR helps executives meet the challenge of leading increasingly digital and data-driven organizations. We work directly with digital leaders, executives, and boards to develop our insights. Our consortium forms a global community that comprises more than seventy-five organizations.

MIT CISR Associate Members

MIT CISR wishes to thank all of our associate members for their support and contributions.

MIT CISR's Mission Expand

MIT CISR helps executives meet the challenge of leading increasingly digital and data-driven organizations. We provide insights on how organizations effectively realize value from approaches such as digital business transformation, data monetization, business ecosystems, and the digital workplace. Founded in 1974 and grounded in MIT’s tradition of combining academic knowledge and practical purpose, we work directly with digital leaders, executives, and boards to develop our insights. Our consortium forms a global community that comprises more than seventy-five organizations.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Case Analysis, Toyota: "The Lean Mind" 70 Years of innovation

This case study aims to reveal the reasons for Toyota's success and make its experience guide the developing brands to success.

Related Papers

helen turner

Long Range Planning

Peter J. Buckley

Mossimo Sesom

Deborah Nightingale

This Transition-To-Lean Guide is intended to help your enterprise leadership navigate your enterprise’s challenging journey into the promising world of “lean.” You have opened this guide because, in some fashion, you have come to realize that your enterprise must undertake a fundamental transformation in how it sees the world, what it values, and the principles that will become its guiding lights if it is to prosper — or even survive — in this new era of “clock-speed” competition. However you may have been introduced to “lean,” you have undertaken to benefit from its implementation.

Ayesha Majid , Yahya Rehman

Toyota is a name almost everyone is familiar with. It has been the market leader in automobiles specially hybrid and electric automobiles. It has been operational in Pakistan since 1989. Toyota is a one of a kind Japanese multinational automotive manufacturer. As of September 2018, it was the sixth largest company in the world in terms of revenue. The economic conditions however have not been very favorable for the automotive industry. The economy of Pakistan and the consistent increase in dollar rates has taken a huge toll on the sales of the multinational manufacturer. Focus group analysis show that majority of the people preferred Honda over Toyota due to several reasons including near to none change in the designs of Toyota Corolla’s variants. Another factor was that Toyota was seen more as a car for the rural areas which was best suited for a rugged terrain. Although the general perception is that Toyota has better car suspension and fuel efficiency, people would still prefer Honda and other Japanese cars. Respondents said that advertisements played a crucial role but they do not compel the customer to buy a product like a car, there are other factors that are taken under consideration. Pakwheels and olx were the first two online platforms that they mentioned when asked about their go to online source. Family and friends advice played a major role in deciding which car to buy. According to the research conducted by our group through questionnaire, a regression was done and seen that the general perception that a reduction in prices will increase sales was not true because people usually associate low prices with low quality products. According to the regression, only advertisement and product have a significant result. All the variables are positively correlated with each other and less than one and positive indicating a formative relationship to the dependent variable. Branding has an insignificant positive relationship with purchase intention because consumers are only considering three competitors; Honda, Suzuki and Japanese cars.

Volume III of this guide may be used as an in-depth reference source for acquiring deep knowledge about many of the aspects of transitioning to lean. Lean change agents and lean implementation leaders should find this volume especially valuable in preparing their organizations for the lean transformation and in developing and implementing an enterprise level lean implementation plan. The richness and depth of the discussions in this volume should be helpful in charting a course, avoiding pitfalls, and making in-course corrections during implementation. We assume that the reader of Volume III is familiar with the history and general principles of the lean paradigm that are presented in Volume I, Executive Overview. A review of Volume II, Transition to Lean Roadmap may be helpful prior to launching into Volume III. For those readers most heavily involved in the lean transformation, all three volumes should be understood and referenced frequently.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

THE ESSENCE OF JUST-IN-TIME: PRACTICE-IN-USE AT TOYOTA PRODUCTION SYSTEM MANAGED ORGANIZATIONS - How Toyota Turns Workers Into Problem Solvers

by Sarah Jane Johnston, HBS Working Knowledge

When HBS professor Steven Spear recently released an abstract on problem solving at Toyota, HBS Working Knowledge staffer Sarah Jane Johnston e-mailed off some questions. Spear not only answered the questions, but also asked some of his own—and answered those as well.

Sarah Jane Johnston: Why study Toyota? With all the books and articles on Toyota, lean manufacturing, just-in-time, kanban systems, quality systems, etc. that came out in the 1980s and 90s, hasn't the topic been exhausted?

Steven Spear: Well, this has been a much-researched area. When Kent Bowen and I first did a literature search, we found nearly 3,000 articles and books had been published on some of the topics you just mentioned.

However, there was an apparent discrepancy. There had been this wide, long-standing recognition of Toyota as the premier automobile manufacturer in terms of the unmatched combination of high quality, low cost, short lead-time and flexible production. And Toyota's operating system—the Toyota Production System—had been widely credited for Toyota's sustained leadership in manufacturing performance. Furthermore, Toyota had been remarkably open in letting outsiders study its operations. The American Big Three and many other auto companies had done major benchmarking studies, and they and other companies had tried to implement their own forms of the Toyota Production System. There is the Ford Production System, the Chrysler Operating System, and General Motors went so far as to establish a joint venture with Toyota called NUMMI, approximately fifteen years ago.

However, despite Toyota's openness and the genuinely honest efforts by other companies over many years to emulate Toyota, no one had yet matched Toyota in terms of having simultaneously high-quality, low-cost, short lead-time, flexible production over time and broadly based across the system.

It was from observations such as these that Kent and I started to form the impression that despite all the attention that had already been paid to Toyota, something critical was being missed. Therefore, we approached people at Toyota to ask what they did that others might have missed.

What did they say?

To paraphrase one of our contacts, he said, "It's not that we don't want to tell you what TPS is, it's that we can't. We don't have adequate words for it. But, we can show you what TPS is."

Over about a four-year period, they showed us how work was actually done in practice in dozens of plants. Kent and I went to Toyota plants and those of suppliers here in the U.S. and in Japan and directly watched literally hundreds of people in a wide variety of roles, functional specialties, and hierarchical levels. I personally was in the field for at least 180 working days during that time and even spent one week at a non-Toyota plant doing assembly work and spent another five months as part of a Toyota team that was trying to teach TPS at a first-tier supplier in Kentucky.

What did you discover?

We concluded that Toyota has come up with a powerful, broadly applicable answer to a fundamental managerial problem. The products we consume and the services we use are typically not the result of a single person's effort. Rather, they come to us through the collective effort of many people each doing a small part of the larger whole. To a certain extent, this is because of the advantages of specialization that Adam Smith identified in pin manufacturing as long ago as 1776 in The Wealth of Nations . However, it goes beyond the economies of scale that accrue to the specialist, such as skill and equipment focus, setup minimization, etc.

The products and services characteristic of our modern economy are far too complex for any one person to understand how they work. It is cognitively overwhelming. Therefore, organizations must have some mechanism for decomposing the whole system into sub-system and component parts, each "cognitively" small or simple enough for individual people to do meaningful work. However, decomposing the complex whole into simpler parts is only part of the challenge. The decomposition must occur in concert with complimentary mechanisms that reintegrate the parts into a meaningful, harmonious whole.

This common yet nevertheless challenging problem is obviously evident when we talk about the design of complex technical devices. Automobiles have tens of thousands of mechanical and electronic parts. Software has millions and millions of lines of code. Each system can require scores if not hundreds of person-work-years to be designed. No one person can be responsible for the design of a whole system. No one is either smart enough or long-lived enough to do the design work single handedly.

Furthermore, we observe that technical systems are tested repeatedly in prototype forms before being released. Why? Because designers know that no matter how good their initial efforts, they will miss the mark on the first try. There will be something about the design of the overall system structure or architecture, the interfaces that connect components, or the individual components themselves that need redesign. In other words, to some extent the first try will be wrong, and the organization designing a complex system needs to design, test, and improve the system in a way that allows iterative congruence to an acceptable outcome.

The same set of conditions that affect groups of people engaged in collaborative product design affect groups of people engaged in the collaborative production and delivery of goods and services. As with complex technical systems, there would be cognitive overload for one person to design, test-in-use, and improve the work systems of factories, hotels, hospitals, or agencies as reflected in (a) the structure of who gets what good, service, or information from whom, (b) the coordinative connections among people so that they can express reliably what they need to do their work and learn what others need from them, and (c) the individual work activities that create intermediate products, services, and information. In essence then, the people who work in an organization that produces something are simultaneously engaged in collaborative production and delivery and are also engaged in a collaborative process of self-reflective design, "prototype testing," and improvement of their own work systems amidst changes in market needs, products, technical processes, and so forth.

It is our conclusion that Toyota has developed a set of principles, Rules-in-Use we've called them, that allow organizations to engage in this (self-reflective) design, testing, and improvement so that (nearly) everyone can contribute at or near his or her potential, and when the parts come together the whole is much, much greater than the sum of the parts.

What are these rules?

We've seen that consistently—across functional roles, products, processes (assembly, equipment maintenance and repair, materials logistics, training, system redesign, administration, etc.), and hierarchical levels (from shop floor to plant manager and above) that in TPS managed organizations the design of nearly all work activities, connections among people, and pathways of connected activities over which products, services, and information take form are specified-in-their-design, tested-with-their-every-use, and improved close in time, place, and person to the occurrence of every problem.

That sounds pretty rigorous.

It is, but consider what the Toyota people are attempting to accomplish. They are saying before you (or you all) do work, make clear what you expect to happen (by specifying the design), each time you do work, see that what you expected has actually occurred (by testing with each use), and when there is a difference between what had actually happened and what was predicted, solve problems while the information is still fresh.

That reminds me of what my high school lab science teacher required.

Exactly! This is a system designed for broad based, frequent, rapid, low-cost learning. The "Rules" imply a belief that we may not get the right solution (to work system design) on the first try, but that if we design everything we do as a bona fide experiment, we can more rapidly converge, iteratively, and at lower cost, on the right answer, and, in the process, learn a heck of lot more about the system we are operating.

You say in your article that the Toyota system involves a rigorous and methodical problem-solving approach that is made part of everyone's work and is done under the guidance of a teacher. How difficult would it be for companies to develop their own program based on the Toyota model?

Your question cuts right to a critical issue. We discussed earlier the basic problem that for complex systems, responsibility for design, testing, and improvement must be distributed broadly. We've observed that Toyota, its best suppliers, and other companies that have learned well from Toyota can confidently distribute a tremendous amount of responsibility to the people who actually do the work, from the most senior, expeirenced member of the organization to the most junior. This is accomplished because of the tremendous emphasis on teaching everyone how to be a skillful problem solver.

How do they do this?

They do this by teaching people to solve problems by solving problems. For instance, in our paper we describe a team at a Toyota supplier, Aisin. The team members, when they were first hired, were inexperienced with at best an average high school education. In the first phase of their employment, the hurdle was merely learning how to do the routine work for which they were responsible. Soon thereafter though, they learned how to immediately identify problems that occurred as they did their work. Then they learned how to do sophisticated root-cause analysis to find the underlying conditions that created the symptoms that they had experienced. Then they regularly practiced developing counter-measures—changes in work, tool, product, or process design—that would remove the underlying root causes.

Sounds impressive.

Yes, but frustrating. They complained that when they started, they were "blissful in their ignorance." But after this sustained development, they could now see problems, root down to their probable cause, design solutions, but the team members couldn't actually implement these solutions. Therefore, as a final round, the team members received training in various technical crafts—one became a licensed electrician, another a machinist, another learned some carpentry skills.

Was this unique?

Absolutely not. We saw the similar approach repeated elsewhere. At Taiheiyo, another supplier, team members made sophisticated improvements in robotic welding equipment that reduced cost, increased quality, and won recognition with an award from the Ministry of Environment. At NHK (Nippon Spring) another team conducted a series of experiments that increased quality, productivity, and efficiency in a seat production line.

What is the role of the manager in this process?

Your question about the role of the manager gets right to the heart of the difficulty of managing this way. For many people, it requires a profound shift in mind-set in terms of how the manager envisions his or her role. For the team at Aisin to become so skilled as problem solvers, they had to be led through their training by a capable team leader and group leader. The team leader and group leader were capable of teaching these skills in a directed, learn-by-doing fashion, because they too were consistently trained in a similar fashion by their immediate senior. We found that in the best TPS-managed plants, there was a pathway of learning and teaching that cascaded from the most senior levels to the most junior. In effect, the needs of people directly touching the work determined the assistance, problem solving, and training activities of those more senior. This is a sharp contrast, in fact a near inversion, in terms of who works for whom when compared with the more traditional, centralized command and control system characterized by a downward diffusion of work orders and an upward reporting of work status.

And if you are hiring a manager to help run this system, what are the attributes of the ideal candidate?

We observed that the best managers in these TPS managed organizations, and the managers in organizations that seem to adopt the Rules-in-Use approach most rapidly are humble but also self-confident enough to be great learners and terrific teachers. Furthermore, they are willing to subscribe to a consistent set of values.

How do you mean?

Again, it is what is implied in the guideline of specifying every design, testing with every use, and improving close in time, place, and person to the occurrence of every problem. If we do this consistently, we are saying through our action that when people come to work, they are entitled to expect that they will succeed in doing something of value for another person. If they don't succeed, they are entitled to know immediately that they have not. And when they have not succeeded, they have the right to expect that they will be involved in creating a solution that makes success more likely on the next try. People who cannot subscribe to these ideas—neither in their words nor in their actions—are not likely to manage effectively in this system.

That sounds somewhat high-minded and esoteric.

I agree with you that it strikes the ear as sounding high principled but perhaps not practical. However, I'm fundamentally an empiricist, so I have to go back to what we have observed. In organizations in which managers really live by these Rules, either in the Toyota system or at sites that have successfully transformed themselves, there is a palpable, positive difference in the attitude of people that is coupled with exceptional performance along critical business measures such as quality, cost, safety, and cycle time.

Have any other research projects evolved from your findings?

We titled the results of our initial research "Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System." Kent and I are reasonably confident that the Rules-in-Use about which we have written are a successful decoding. Now, we are trying to "replicate the DNA" at a variety of sites. We want to know where and when these Rules create great value, and where they do, how they can be implemented most effectively.

Since we are empiricists, we are conducting experiments through our field research. We are part of a fairly ambitious effort at Alcoa to develop and deploy the Alcoa Business System, ABS. This is a fusion of Alcoa's long standing value system, which has helped make Alcoa the safest employer in the country, with the Rules in Use. That effort has been going on for a number of years, first with the enthusiastic support of Alcoa's former CEO, Paul O'Neill, now Secretary of the Treasury (not your typical retirement, eh?) and now with the backing of Alain Belda, the company's current head. There have been some really inspirational early results in places as disparate as Hernando, Mississippi and Poces de Caldas, Brazil and with processes as disparate as smelting, extrusion, die design, and finance.

We also started creating pilot sites in the health care industry. We started our work with a "learning unit" at Deaconess-Glover Hospital in Needham, not far from campus. We've got a series of case studies that captures some of the learnings from that effort. More recently, we've established pilot sites at Presbyterian and South Side Hospitals, both part of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. This work is part of a larger, comprehensive effort being made under the auspices of the Pittsburgh Regional Healthcare Initiative, with broad community support, with cooperation from the Centers for Disease Control, and with backing from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Also, we've been testing these ideas with our students: Kent in the first year Technology and Operations Management class for which he is course head, me in a second year elective called Running and Growing the Small Company, and both of us in an Executive Education course in which we participate called Building Competitive Advantage Through Operations.

· · · ·

Steven Spear is an Assistant Professor in the Technology and Operations Management Unit at the Harvard Business School.

Other HBS Working Knowledge stories featuring Steven J. Spear: Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System Why Your Organization Isn't Learning All It Should

Developing Skillful Problem Solvers: Introduction

Within TPS-managed organizations, people are trained to improve the work that they perform, they learn to do this with the guidance of a capable supplier of assistance and training, and training occurs by solving production and delivery-related problems as bona fide, hypothesis-testing experiments. Examples of this approach follow.

- A quality improvement team at a Toyota supplier, Taiheiyo, conducted a series of experiments to eliminate the spatter and fumes emitted by robotic welders. The quality circle members, all line workers, conducted a series of complex experiments that resulted in a cleaner, safer work environment, equipment that operated with less cost and higher reliability, and relief for more technically-skilled maintenance and engineering specialists from basic equipment maintenance and repair.

- A work team at NHK (Nippon Spring) Toyota, were taught to conduct a series of experiments over many months to improve the process by which arm rest inserts were "cold molded." The team reduced the cost, shortened the cycle time, and improved the quality while simultaneously developing the capability to take a similar experimental approach to process improvement in the future.

- At Aisin, a team of production line workers progressed from having the skills to do only routine production work to having the skills to identify problems, investigate root causes, develop counter-measures, and reconfigure equipment as skilled electricians and machinists. This transformation occurred primarily through the mechanism of problem solving-based training.

- Another example from Aisin illustrates how improvement efforts—in this case of the entire production system by senior managers—were conducted as a bona fide hypothesis-refuting experiment.

- The Acme and Ohba examples contrast the behavior of managers deeply acculturated in Toyota with that of their less experienced colleagues. The Acme example shows the relative emphasis one TPS acculturated manager placed on problem solving as a training opportunity in comparison to his colleagues who used the problem-solving opportunity as a chance to first make process improvements. An additional example from a Toyota supplier reinforces the notion of using problem solving as a vehicle to teach.

- The data section concludes with an example given by a former employee of two companies, both of which have been recognized for their efforts to be a "lean manufacturer" but neither of which has been trained in Toyota's own methods. The approach evident at Toyota and its suppliers was not evident in this person's narrative.

Defining conditions as problematic

We concluded that within Toyota Production System-managed organizations three sets of conditions are considered problematic and prompt problem-solving efforts. These are summarized here and are discussed more fully in a separate paper titled "Pursuing the IDEAL: Conditions that Prompt Problem Solving in Toyota Production System-Managed Organizations."

Failure to meet a customer need

It was typically recognized as a problem if someone was unable to provide the good, service, or information needed by an immediate or external customer.

Failure to do work as designed

Even if someone was able to meet the need of his or her customers without fail (agreed upon mix, volume, and timing of goods and services), it was typically recognized as a problem if a person was unable to do his or her own individual work or convey requests (i.e., "Please send me this good or service that I need to do my work.") and responses (i.e., "Here is the good or service that you requested, in the quantity you requested.").

Failure to do work in an IDEAL fashion

Even if someone could meet customer needs and do his or her work as designed, it was typically recognized as a problem if that person's work was not IDEAL. IDEAL production and delivery is that which is defect-free, done on demand, in batches of one, immediate, without waste, and in an environment that is physically, emotionally, and professionally safe. The improvement activities detailed in the cases that follow, the reader will see, were motivated not so much by a failure to meet customer needs or do work as designed. Rather, they were motivated by costs that were too high (i.e., Taiheiyo robotic welding operation), batch sizes that were too great (i.e., the TSSC improvement activity evaluated by Mr. Ohba), lead-times that were too long, processes that were defect-causing (i.e., NHK cold-forming process), and by compromises to safety (i.e., Taiheiyo).

Our field research suggests that Toyota and those of its suppliers that are especially adroit at the Toyota Production System make a deliberate effort to develop the problem-solving skills of workers—even those engaged in the most routine production and delivery. We saw evidence of this in the Taiheiyo, NHK, and Aisin quality circle examples.

Forums are created in which problem solving can be learned in a learn-by-doing fashion. This point was evident in the quality circle examples. It was also evident to us in the role played by Aisin's Operations Management Consulting Division (OMCD), Toyota's OMCD unit in Japan, and Toyota's Toyota Supplier Support Center (TSSC) in North America. All of these organizations support the improvement efforts of the companies' factories and those of the companies' suppliers. In doing so, these organizations give operating managers opportunities to hone their problem-solving and teaching skills, relieved temporarily of day to day responsibility for managing, production and delivery of goods and services to external customers.

Learning occurs with the guidance of a capable teacher. This was evident in that each of the quality circles had a specific group leader who acted as coach for the quality circle's team leader. We also saw how Mr. Seto at NHK defined his role as, in part, as developing the problem-solving and teaching skills of the team leader whom he supervised.

Problem solving occurs as bona fide experiments. We saw this evident in the experience of the quality circles who learned to organize their efforts as bona fide experiments rather than as ad hoc attempts to find a feasible, sufficient solution. The documentation prepared by the senior team at Aisin is organized precisely to capture improvement ideas as refutable hypotheses.

Broadly dispersed scientific problem solving as a dynamic capability

Problem solving, as illustrated in this paper, is a classic example of a dynamic capability highlighted in the "resource-based" view of the firm literature.

Scientific problem solving—as a broadly dispersed skill—is time consuming to develop and difficult to imitate. Emulation would require a similar investment in time, and, more importantly, in managerial resources available to teach, coach, assist, and direct. For organizations currently operating with a more traditional command and control approach, allocating such managerial resources would require more than a reallocation of time across a differing set of priorities. It would also require an adjustment of values and the processes through which those processes are expressed. Christensen would argue that existing organizations are particularly handicapped in making such adjustments.

Excerpted with permission from "Developing Skillful Problem Solvers in Toyota Production System-Managed Organizations: Learning to Problem Solve by Solving Problems," HBS Working Paper , 2001.

(Still) learning from Toyota

In the two years since I retired as president and CEO of Canadian Autoparts Toyota (CAPTIN), I’ve had the good fortune to work with many global manufacturers in different industries on challenges related to lean management. Through that exposure, I’ve been struck by how much the Toyota production system has already changed the face of operations and management, and by the energy that companies continue to expend in trying to apply it to their own operations.

Yet I’ve also found that even though companies are currently benefiting from lean, they have largely just scratched the surface, given the benefits they could achieve. What’s more, the goal line itself is moving—and will go on moving—as companies such as Toyota continue to define the cutting edge. Of course, this will come as no surprise for any student of the Toyota production system and should even serve as a challenge. After all, the goal is continuous improvement.

Room to improve

The two pillars of the Toyota way of doing things are kaizen (the philosophy of continuous improvement) and respect and empowerment for people, particularly line workers. Both are absolutely required in order for lean to work. One huge barrier to both goals is complacency. Through my exposure to different manufacturing environments, I’ve been surprised to find that senior managers often feel they’ve been very successful in their efforts to emulate Toyota’s production system—when in fact their progress has been limited.

The reality is that many senior executives—and by extension many organizations—aren’t nearly as self-reflective or objective about evaluating themselves as they should be. A lot of executives have a propensity to talk about the good things they’re doing rather than focus on applying resources to the things that aren’t what they want them to be.

When I recently visited a large manufacturer, for example, I compared notes with a company executive about an evaluation tool it had adapted from Toyota. The tool measures a host of categories (such as safety, quality, cost, and human development) and averages the scores on a scale of zero to five. The executive was describing how his unit scored a five—a perfect score. “Where?” I asked him, surprised. “On what dimension?”

“Overall,” he answered. “Five was the average.”

When he asked me about my experiences at Toyota over the years and the scores its units received, I answered candidly that the best score I’d ever seen was a 3.2—and that was only for a year, before the unit fell back. What happens in Toyota’s culture is that as soon as you start making a lot of progress toward a goal, the goal is changed and the carrot is moved. It’s a deep part of the culture to create new challenges constantly and not to rest when you meet old ones. Only through honest self-reflection can senior executives learn to focus on the things that need improvement, learn how to close the gaps, and get to where they need to be as leaders.

A self-reflective culture is also likely to contribute to what I call a “no excuse” organization, and this is valuable in times of crisis. When Toyota faced serious problems related to the unintended acceleration of some vehicles, for example, we took this as an opportunity to revisit everything we did to ensure quality in the design of vehicles—from engineering and production to the manufacture of parts and so on. Companies that can use crises to their advantage will always excel against self-satisfied organizations that already feel they’re the best at what they do.

A common characteristic of companies struggling to achieve continuous improvement is that they pick and choose the lean tools they want to use, without necessarily understanding how these tools operate as a system. (Whenever I hear executives say “we did kaizen ,” which in fact is an entire philosophy, I know they don’t get it.) For example, the manufacturer I mentioned earlier had recently put in an andon system, to alert management about problems on the line. 1 1. Many executives will have heard of the andon cord, a Toyota innovation now common in many automotive and assembly environments: line workers are empowered to address quality or other problems by stopping production. Featuring plasma-screen monitors at every workstation, the system had required a considerable development and programming effort to implement. To my mind, it represented a knee-buckling amount of investment compared with systems I’d seen at Toyota, where a new tool might rely on sticky notes and signature cards until its merits were proved.

An executive was explaining to me how successful the implementation had been and how well the company was doing with lean. I had been visiting the plant for a week or so. My back was to the monitor out on the shop floor, and the executive was looking toward it, facing me, when I surprised him by quoting a series of figures from the display. When he asked how I’d done so, I pointed out that the tool was broken; the numbers weren’t updating and hadn’t since Monday. This was no secret to the system’s operators and to the frontline workers. The executive probably hadn’t been visiting with them enough to know what was happening and why. Quite possibly, the new system receiving such praise was itself a monument to waste.

Room to reflect

At the end of the day, stories like this underscore the fact that applying lean is a leadership challenge, not just an operational one. A company’s senior executives often become successful as leaders through years spent learning how to contribute inside a particular culture. Indeed, Toyota views this as a career-long process and encourages it by offering executives a diversity of assignments, significant amounts of training, and even additional college education to help prepare them as lean leaders. It’s no surprise, therefore, that should a company bring in an initiative like Toyota’s production system—or any lean initiative requiring the culture to change fundamentally—its leaders may well struggle and even view the change as a threat. This is particularly true of lean because, in many cases, rank-and-file workers know far more about the system from a “toolbox standpoint” than do executives, whose job is to understand how the whole system comes together. This fact can be intimidating to some executives.

Senior executives who are considering lean management (or are already well into a lean transformation and looking for ways to get more from the effort and make it stick) should start by recognizing that they will need to be comfortable giving up control. This is a lesson I’ve learned firsthand. I remember going to CAPTIN as president and CEO of the company and wanting to get off to a strong start. Hoping to figure out how to get everyone engaged and following my initiatives, I told my colleagues what I wanted. Yet after six or eight months, I wasn’t getting where I wanted to go quickly enough. Around that time, a Japanese colleague told me, “Deryl, if you say ‘do this’ everybody will do it because you’re president, whether you say ‘go this way,’ or ‘go that way.’ But you need to figure out how to manage these issues having absolutely no power at all.”

So with that advice in mind, I stepped back and got a core group of good people together from all over the company—a person from production control, a night-shift supervisor, a manager, a couple of engineers, and a person in finance—and challenged them to develop a system. I presented them with the direction but asked them to make it work.

And they did. By the end of the three-year period we’d set as a target, for example, we’d dramatically improved our participation rate in problem-solving activities—going from being one of the worst companies in Toyota Motor North America to being one of the best. The beauty of the effort was that the team went about constructing the program in ways I never would have thought of. For example, one team member (the production-control manager) wanted more participation in a survey to determine where we should spend additional time training. So he created a storyboard highlighting the steps of problem solving and put it on the shop floor with questionnaires that he’d developed. To get people to fill them out, his team offered the respondents a hamburger or a hot dog that was barbecued right there on the shop floor. This move was hugely successful.

Another tip whose value I’ve observed over the years is to find a mentor in the company, someone to whom you can speak candidly. When you’re the president or CEO, it can be kind of lonely, and you won’t have anyone to talk with. I was lucky because Toyota has a robust mentorship system, which pairs retired company executives with active ones. But executives anywhere can find a sounding board—someone who speaks the same corporate language you do and has a similar background. It’s worth the effort to find one.

Finally, if you’re going to lead lean, you need knowledge and passion. I’ve been around leaders who had plenty of one or the other, but you really need both. It’s one thing to create all the energy you need to start a lean initiative and way of working, but quite another to keep it going—and that’s the real trick.

Room to run

Even though I’m retired from Toyota, I’m still engaged with the company. My experiences have given me a unique vantage point to see what Toyota is doing to push the boundaries of lean further still.

For example, about four years ago Toyota began applying lean concepts from its factories beyond the factory floor—taking them into finance, financial services, the dealer networks, production control, logistics, and purchasing. This may seem ironic, given the push so many companies outside the auto industry have made in recent years to drive lean thinking into some of these areas. But that’s very consistent with the deliberate way Toyota always strives to perfect something before it’s expanded, looking to “add as you go” rather than “do it once and stop.”

Of course, Toyota still applies lean thinking to its manufacturing operations as well. Take major model changes, which happen about every four to eight years. They require a huge effort—changing all the stamping dies, all the welding points and locations, the painting process, the assembly process, and so on. Over the past six years or so, Toyota has nearly cut in half the time it takes to do a complete model change.

Similarly, Toyota is innovating on the old concept of a “single-minute exchange of dies” 2 2. Quite honestly, the single-minute exchange of dies aspiration is really just that—a goal. The fastest I ever saw anyone do it during my time at New United Motor Manufacturing (NUMMI) was about 10 to 15 minutes. and applying that thinking to new areas, such as high-pressure injection molding for bumpers or the manufacture of alloy wheels. For instance, if you were making an aluminum-alloy wheel five years ago and needed to change from one die to another, that would require about four or five hours because of the nature of the smelting process. Now, Toyota has adjusted the process so that the changeover time is down to less than an hour.

Finally, Toyota is doing some interesting things to go on pushing the quality of its vehicles. It now conducts surveys at ports, for example, so that its workers can do detailed audits of vehicles as they are funneled in from Canada, the United States, and Japan. This allows the company to get more consistency from plant to plant on everything from the torque applied to lug nuts to the gloss levels of multiple reds so that color standards for paint are met consistently.

The changes extend to dealer networks as well. When customers take delivery of a car, the salesperson is accompanied by a technician who goes through it with the new owner, in a panel-by-panel and option-by-option inspection. They’re looking for actionable information: is an interior surface smudged? Is there a fender or hood gap that doesn’t look quite right? All of this checklist data, fed back through Toyota’s engineering, design, and development group, can be sent on to the specific plant that produced the vehicle, so the plant can quickly compare it with other vehicles produced at the same time.

All of these moves to continue perfecting lean are consistent with the basic Toyota approach I described: try and perfect anything before you expand it. Yet at the same time, the philosophy of continuous improvement tells us that there’s ultimately no such thing as perfection. There’s always another goal to reach for and more lessons to learn.

Deryl Sturdevant, a senior adviser to McKinsey, was president and CEO of Canadian Autoparts Toyota (CAPTIN) from 2006 to 2011. Prior to that, he held numerous executive positions at Toyota, as well as at the New United Motor Manufacturing (NUMMI) plant (a joint venture between Toyota and General Motors), in Fremont, California.

Explore a career with us

Managing Sustainability to Be First: The Toyota Case

- Conference paper

- Cite this conference paper

- Maria Garbelli 7

Part of the book series: Eurasian Studies in Business and Economics ((EBES,volume 2/2))

1296 Accesses

Sustainability matters along with attention to a company’s social and environmental commitment and the related (complex) performance is far from new in the literature, but the last years have pressed both academics and managers by urgent issues such as climate changes and disasters, poverty, economic and social crisis in many countries, human rights violations, health concerns and so on. Also, the end of twentieth century saw unprecedented changes in corporate strategy and management towards sustainable thinking—the emergence of sustainability as corporate strategy, and making sustainability an integral part of a company’s business strategy in order to gain bottom-line benefits and to accomplish new law requirements. In such a global, unstable, market, sustainability becomes an investable concept, crucial in driving interest and investments to the mutual benefit of companies and investors. Toyota’s commitment for a sustainable management has been developed since decades ago and continues nowadays, representing a perfect example for the whole market, and witnessing the urgency of an integrated approach along the supply chain, in order to gain competitive advantage through ‘sustainability’.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

‘The greatest pressure, at least externally, is coming from national regulators in the countries where firms operate. But pression is also coming from stakeholders—shareholders, business partners, and employees—and increasingly, from the companies themselves as they struggle to successfully combine performance and purpose in the post-recession world’ (The Economist 2010 ).

The stakeholders approach indicates that organisations are not only accountable to its shareholders but should also balance a multiplicity of stakeholders interests that can affect or are affected by the achievement of an organisation’s objectives (Freeman 1984 ).

One remanufactured part uses 80 % less energy, 88 % less water, 92 % fewer chemical products and generates 70 % less waste during production compared to a new part (Perella 2014 ).

Toyota seems to be the leader on the movement from a traditional transport way, the so called ‘conventional approach—transport planning and engineering, to a new, unconventional one: sustainable mobility (Banister 2008 ). Despite a lack of clear definition on the wider concept of sustainable transportation, we can adopt the Sustainable mobility one, which fits our research aim:it ‘means transporting people in eco-friendly ways. It means using mass transit in urban environments, particularly electrified trams and trolleys and light rail trains for beyond downtown. As it relates to personal transportation, it’s using electric drivetrains—all-electric vehicles, hybrids, plug-in hybrids and fuel cell hybrid vehicles—as well as alternative liquid and gaseous fuels for internal combustion engine vehicles. The goal: To reduce the impact of transportation on the climate and eventually replace petroleum-based fuels—also mitigating the global strife associated with petroleum-based fuels’ (Gable 2014 ).

Banister, D. (2008). The sustainable mobility paradigm. Transport Policy, 15 , 73–80.

Article Google Scholar

Basak, D., Haider, M. T., & Shrivastava, A. K. (2013). Lean manufacturing in practice a case study of Toyota Motors Company. International Journal of Computer Science and Management Studies, 13 (5), 2231–5268.

Google Scholar

Bottero, M., & Mondini, G. (2008). An appraisal of analytic network process and its role in sustainability assessment in Northern Italy. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 19 (6), 642–660.

Drexhage, J., & Murphy, D. (2010). Sustainable development: From Brundtland to Rio 2012 . Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD).

Dyllick, T., & Hockerts, K. (2002). Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 11 , 130–141.

Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business . Oxford: Capstone.

Fiksel, J., McDaniel, J., & Mendenhall, C. (1999). Measuring progress towards sustainability: Principles, process, and best practices. In Greening of Industry Network Conference. Best Practice Proceedings . Battelle Memorial Institute, OH: Life Cycle Management Group Columbus.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach . London: Pitman Publishing.

Gable, C. (2014). Toyota embraces sustainable mobility . Accessed September 22, 2014, from http://www.alternativefuels.about.com

Gladwin, T., Kennelly, J., & Krause, T. S. (1995). Shifting paradigms for sustainable developments implications for management theory and research. Academy of Management Review, 20 (4), 874–907.

Klassen, R. D., & McLaughlin, C. P. (1996). The impact of environmental performance on firm performance. Management Science, 42 (8), 1199–1214.

Article MATH Google Scholar

Kolk, A. (2010). Social and sustainability dimensions of regionalization and (semi) globalization. Multinational Business Review, 18 (1), 51–72.

Miles, M. P., & Covin, J. G. (2000). Environmental marketing: A source of reputational. Competitive and Financial Advantage, Journal of Business Ethics, 23 , 299–311.

Patari, S., Jantunen, A., Kylaheiko, K., & Sandstrom, J. (2012). Does sustainable development foster value creation? Empirical evidence from the global energy industry. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 19 (6), 317–326.

Perella, M. (2014, March 14). Renault, JLR, Nissan and Toyota drive car industry towards sustainability. The Guardian. Accessed September 15, 2014, from http://www.theguardian.com

Ricotti, P. (2010). Sostenibilità e green economy—Quarto settore. Competitività, strategie e valoreaggiunto per le impresedelterzomillennio . Torino: Franco Angeli.

Schaltegger, S., & Wagner, S. M. (2006). Integrative management of sustainability performance, measurement and reporting. International Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Performance Evaluation, 3 (1), 1–19.

Sharpley, R. (2000). Tourism and sustainable development: Exploring the theoretical divide. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 8 (1), 1–19.

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Sharpley, R. (2010). The myth of sustainable tourism. CSD Working Papers Series 2009/2010 – No. 4.

The Economist. (2010). Global trends in sustainability performance management . Economist Intelligence Unit Limited. Accessed September 20, 2014, from http://fm.sap.com

WCED. (1987). World commission on environment and development, Our common future . Oxford: Oxford Paperbacks.

Womack, J. T., Jones, D. T., & Roos, D. (1990). The machine that changed the world: The story of Lean Production . London: The Free Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, Management and Statistics, UniversitàdegliStudi di Milano Bicocca, Milan, Italy

Maria Garbelli

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Maria Garbelli .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Istanbul Medeniyet University, Faculty of Economics, Istanbul, Turkey

Mehmet Huseyin Bilgin

MUFG Union Bank, San Francisco, California, USA

Hakan Danis

Istanbul Medeniyet University, Faculty of Tourism, Istanbul, Turkey

Ender Demir

Eurasia Business & Economic Society, Fatih Istanbul, Turkey

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Garbelli, M. (2016). Managing Sustainability to Be First: The Toyota Case. In: Bilgin, M., Danis, H., Demir, E., Can, U. (eds) Business Challenges in the Changing Economic Landscape - Vol. 2. Eurasian Studies in Business and Economics, vol 2/2. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22593-7_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22593-7_4

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-22592-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-22593-7

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance Economics and Finance (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My Portfolio

- Latest News

- Stock Market

- Premium News

- Biden Economy

- EV Deep Dive

- Stocks: Most Actives

- Stocks: Gainers

- Stocks: Losers

- Trending Tickers

- World Indices

- US Treasury Bonds

- Top Mutual Funds

- Highest Open Interest

- Highest Implied Volatility

- Stock Comparison

- Advanced Charts

- Currency Converter

- Basic Materials

- Communication Services

- Consumer Cyclical

- Consumer Defensive

- Financial Services

- Industrials

- Real Estate

- Mutual Funds

- Credit cards

- Balance Transfer Cards

- Cash-back Cards

- Rewards Cards

- Travel Cards

- Personal Loans

- Student Loans

- Car Insurance

- Morning Brief

- Market Domination

- Market Domination Overtime

- Opening Bid

- Stocks in Translation

- Lead This Way

- Good Buy or Goodbye?

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

- Newsletters

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

Yahoo Finance

Esg case study – toyota motor corporation.

This article was originally published on ETFTrends.com.

By Sara Rodriguez, Sage ESG Research Analyst

About Toyota Motor Corporation

Toyota Motor Corporation is a Japanese multinational automotive company that designs, manufacturers, and sells passenger and commercial vehicles. The company also has a financial services branch that offers financing to vehicle dealers and customers. Toyota is the second-largest car manufacturer in the world and ranked the 11th largest company by Forbes — and produces vehicles under five brands: Toyota, Hino, Lexus, Ranz, and Daihatsu. Toyota also partners with Subaru, Isuzu, and Mazda.

Environmental

Motor vehicles are one of the largest contributors to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and, as a result, climate change, with the transportation sector accounting for a third of U.S. GHG emissions in 2018. Although most emissions come from vehicle usage rather than the process of manufacturing vehicles, government regulations place the burden on auto companies to improve fuel efficiency and reduce overall emissions. While climate change regulations present financial risk to automakers, they also offer opportunities; increased fuel efficiency requirements are likely to lead to more sales of electric vehicles and hybrid systems. Toyota pioneered the first popular hybrid vehicle with the 1997 release of the Prius, the world’s first mass-produced hybrid. Since then, Toyota has sold 15 million hybrids worldwide . In 2018, hybrids accounted for 58% of Toyota’s sales, contributing to Toyota reaching substantially better carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from new vehicles than regulatory standards and the best levels in the industry (102.1g/km compared to U.S. regulation of 119g/km). In 2020, Toyota reduced global average CO2 emissions from new vehicles by 22% compared to 2010 levels by improving vehicle performance and expanding its lineup. Toyota’s goal is to increase that number to 30% by 2025, with the goal of 90% total reduction by 2050. The company aims to offer an electric version of all Toyota and Lexus models worldwide by 2025. (Toyota does not yet sell any all-electric vehicles to the U.S., but it does outside the U.S.)

In addition to greenhouse gases, cars emit smog-forming pollutants that contribute to poor air quality and trigger negative health effects. Recently, a London court ruled that air pollution significantly contributed to the death of a nine-year-old girl with asthma who had been exposed to excessive nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels. NO2 is a toxic gas emitted by cars that use diesel fuel, and although European Union laws set regulatory levels for NO2 in the air, Britain has missed its targets for a decade due to a lack of enforcement. As Toyota expands into European markets, the smog rating of its cars will be financially material and an important aspect of risk management.

Compared to industry peers, Toyota excels in addressing emissions and fuel efficiency. In 2014 Toyota Motor Credit Corporation, the financial arm of Toyota Motor Corporation, introduced the auto industry’s first-ever asset-backed green bond and has since issued five total green bonds. The newest $750 million bond will go toward developing new Toyota and Lexus vehicles to possess a hybrid or alternative fuel powertrain, achieve a minimum of 40 highway and city miles per gallon, and receive an EPA Smog Rating of 7/10 or better. The bond program was reviewed by Sustainalytics, which found that Toyota leads its competitors in supporting its carbon transition through green bond investments.

In addition to curbing emissions caused by Toyota’s vehicles, the company seeks to reduce plant emissions to zero by 2050 by utilizing renewable energy and equipment optimization. In automaking, water is used in painting and other manufacturing processes. Toyota has implemented initiatives to reduce the amount of water used in manufacturing and has developed technology that allows the painting process to require no water. In 2019, Toyota reduced water usage by 5% per vehicle, with the goal of 3% further reduction by 2025, for an overall reduction of 34% from 2001 levels. To reduce the environmental impact of materials purchased from suppliers, Toyota has launched Green Purchasing Guidelines to prioritize the purchase of parts and equipment with a low environmental footprint. We would like to see Toyota continue to develop its supply chain environmental policies.

As the global population grows, so does number of cars on the road, which creates waste when they’ve reached the end of their useful lives. Toyota’s Global 100 Dismantlers Project was created to establish systems for appropriate treatment of end-of-life vehicles through battery collection and car recycling. Toyota aims to have 15 vehicle recycling facilities by 2025. Toyota is also working to minimize waste by prolonging the useful life of its vehicles. Toyota has a strong reputation for producing quality, reliable vehicles. Consumer Reports lists Toyota’s overall reliability as superb, and Toyota and Lexus often take the top spots in Consumer Reports Annual Auto Reliability Survey. An Iseecars.com study found that Toyota full-size SUV models are the longest-lasting vehicles and most likely to reach over 200,000 miles.

Driving is an activity with inherent risk. The World Health Organization estimates that 1.35 million people die in car accidents each year. Accidents are worse in emerging nations where transportation infrastructure has not kept up with the increase in the number of cars on the road; without countermeasures, traffic fatalities are predicted to become the seventh-leading cause of death worldwide by 2030. Demand for personal vehicles will continue to increase as developing countries experience higher standards of living, and product safety will be paramount to automaker’s reputations and brand values. Toyota has put forth a goal of Zero Casualties from Traffic Accidents and adopted an Integrated Safety Management Concept to work toward eliminating traffic fatalities by providing driver support at each stage of driving: from parking to normal operation, the accident itself, and the post-crash. Toyota and Lexus models regularly earn top safety ratings by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. In addition to traditional safety features, Toyota actively invests in the development of autonomous vehicles, including a $500 million investment in Uber and autonomous ridesharing. If fully developed, autonomous driving can offer increased safety to passengers, lower accident rates, and provide mobility for the elderly and physically disabled.

Accidents caused by defective vehicles can have significant financial repercussions for auto manufacturers. Toyota experienced significant damage to its reputation and brand value in 2009 when unintended acceleration caused a major accident that killed four people riding in a dealer-loaned Lexus in San Diego. Toyota subsequently began recalling millions of vehicles, citing problems of pedal entrapment from unsecured floor mats and “sticky gas pedals.” Toyota’s failure to quickly respond resulted in a $1.2 billion settlement with the Justice Department and $50 million in fines from the NHTSA. The scandal generated an extraordinary amount of news coverage, and the Toyota recall story ranked among the top 10 news stories across all media in January and February 2010. Litigation costs, warranty costs, and increased marketing to counter the negative publicity of the event were estimated to cost Toyota over $5 billion (annual sales are about $275 billion). As a result of bad press, Toyota’s 2010 sales fell 16% from the previous year and its stock price fell 10% overall, while competitors like Ford benefitted and experienced stock price growth of 80% over the same period. Future recalls and quality issues are certain to prove costly for Toyota and may continue to negatively impact its consumer reputation.

Another social issue that can be financially material for automakers is human rights. Automobiles consist of about 30,000 parts, making their supply chain extensive and at high risk for human rights abuses. Toyota addresses human rights concerns in its Corporate Sustainability Report (CSR) and cites Migrant Workers and Responsible Sourcing of Cobalt as its priorities for 2020; however, Toyota does not have a clean labor record. A 2008 report published by the Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights accused Toyota of a catalog of human rights abuses, including stripping foreign workers of their passports and forcing them to work grueling hours without days off for less than half of the legal minimum wage. Toyota was also accused of involvement in the suppression of freedom of association at its plant in the Philippines. Toyota’s CSR lists a host of external nongovernmental organizations the company partners with to promote fair working conditions, however; due to the high-risk present in its supply chain and its past offenses, we would like to see the company further develop its labor and human rights policies.

Lastly, we would mention that Toyota has been accused of discriminatory practices. In 2016, Toyota Motor Credit Corporation, the financial arm of Toyota Motor Corporation, agreed to pay 21.9 million in restitution to thousands of African American, Asian, and Pacific Islander customers for charging them higher interest rates on auto loans than their white counterparts with comparable creditworthiness. Toyota has since taken measures to change its pricing and compensation system to reduce incentives to mark up interest rates.

Toyota shows strength in its transparency, and its Corporate Sustainability Report (CSR) is prepared in accordance with multiple sustainability reporting agencies, including the Global Reporting Initiative, Sustainable Accounting Standards Board, and the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures; the CSR data is also verified by a third party. Starting in 2021, Toyota’s CSR will be updated whenever necessary to ensure timely disclosure, rather than annually. In 2019 Toyota created a Sustainability Management Department and added the role of Chief Sustainability Officer to its executive management team in 2020. Toyota’s CSR offers thorough information on its executive compensation policies, however; the composition of Toyota’s board of directors is an area of weakness for the company. There is a lack of independence among board members, and the chair of the board is not independent. In general, when compared to the U.S., Japanese companies have a smaller percentage of outside directors due to a history of corporate governance emphasizing incumbency and promotion from within. However, since the release of the Japanese Corporate Governance Code in 2015, companies have felt pressure to make meaningful board composition changes. We hope to see Toyota strengthen its board composition and adopt executive renumeration policies that are tied to sustainability performance.

Like other automakers, Toyota has lobbied aggressively to weaken Obama-era fuel economy standards. In 2017, the Environmental Protection Agency announced plans to work with Toyota to overhaul internal management practices at the agency. Inviting a company regulated by the agency to alter internal practices has been previously unprecedented and raises concerns over how Toyota could wield influence over EPA functions. Toyota is a member of the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers, the most powerful automotive industry lobbying association, which has strongly opposed climate change motivated regulation since 2016, contradicting the company’s public stance on emissions.

Risk & Outlook

Sage believes Toyota to be well adapted to manage sustainability challenges, despite the high environmental and social risks in the automotive industry. We expect the auto industry to see an increase in regulatory risk surrounding vehicle emissions and fuel efficiency; however, we believe Toyota will continue to innovate to meet and exceed emission standards and the company is well positioned to benefit from future fuel efficiency regulations. We hope to see Toyota continue to improve its social performance and expand on its recently introduced human capital policies. In addition to regulation, the auto industry faces disruption caused by new areas of technology such as automated driving, electrification, and shared mobility, and these areas will be important to monitor. Toyota’s strong management of ESG issues makes the company a leader amongst its peers; however, due to risk present in the automotive industry we rank Toyota a 3/5 for its Sage ESG Leaf Score.

Sage ESG Leaf Score Methodology

No two companies are alike. This is exceptionally apparent from an ESG perspective, where the challenge lies not only in assessing the differences between companies, but also in the differences across industries. Although a company may be a leader among its peer group, the industry in which it operates may expose it to risks that cannot be mitigated through company management. By combining an ESG macro industry risk analysis with a company-level sustainability evaluation, the Sage Leaf Score bridges this gap, enabling investors to quickly assess companies across industries. Our Sage Leaf Score, which is based on a 1 to 5 scale (with 5 leaves representing ESG leaders), makes it easy for investors to compare a company in, for example, the energy industry to a company in the technology industry, and to understand that all 5-leaf companies are leaders based on their individual company management and the level of industry risk that they face.

For more information on Sage’s Leaf Score, click here.

Originally published by Sage Advisory

ISS ESG Corporate Rating Report on Toyota Motor Corporation.

Environmental Report 2020 Toyota Motor Corporation.

Sustainability Data Book 2020 Toyota Motor Corporation.

Lambert, Lisa. “Toyota Motor Credit settles with U.S. over racial bias in auto loans” February 2, 2016.

“Automobiles” Sustainability Accounting Standards Board. September, 2014.

Kaufman, Alexander. “Scott Pruitt’s Plan to Outsource Part Of EPA Overhaul to Automaker Raises Concerns” December 12, 2017.

“How the US auto industry accelerated lobbying under President Trump” November, 2017.

Charles Kernaghan, Barbara Briggs, Xiaomin Zhang, et al. “The Toyota You Don’t Know” Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights. 2008.

Road Safety World Health Organization.

Toyota Motor Credit Corporation Green Bond Framework Second-Party Opinion January 21, 2020.

Toshihiko Hiura and Junya Ishikawa. "Corporate Governance in Japan: Board Membership and Beyond" Bain & Company. February 23, 2016.

Taylor, Lin. ”Landmark ruling links death of UK schoolgirl to pollution" December 16, 2020.

Disclosures

Sage Advisory Services, Ltd. Co. is a registered investment adviser that provides investment management services for a variety of institutions and high net worth individuals. The information included in this report constitute Sage’s opinions as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice due to various factors, such as market conditions. This report is for informational purposes only and is not intended as investment advice or an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any security, strategy or investment product. Investors should make their own decisions on investment strategies based on their specific investment objectives and financial circumstances. All investments contain risk and may lose value. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Sustainable investing limits the types and number of investment opportunities available, this may result in the Fund investing in securities or industry sectors that underperform the market as a whole or underperform other strategies screened for sustainable investing standards. No part of this Material may be produced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without our express written permission. For additional information on Sage and its investment management services, please view our web site at www.sageadvisory.com, or refer to our Form ADV, which is available upon request by calling 512.327.5530.

POPULAR ARTICLES AND RESOURCES FROM ETFTRENDS.COM

SPY ETF Quote

VOO ETF Quote

QQQ ETF Quote

VTI ETF Quote

JNUG ETF Quote

Top 34 Gold ETFs

Top 34 Oil ETFs

Top 57 Financials ETFs

Crude Oil ETFs Continue to Rally Despite Surprise Inventory Build

Biotech ETFs Pop Amid Pending J&J Vaccine Approval

Stock ETFs Reverse Their Slump on Powell Comments

What GameStop’s Crazy Ride Can Teach Us About Investing

Bitcoin and Tesla Are Both Falling

READ MORE AT ETFTRENDS.COM >

- About / Contact

- Privacy Policy

- Alphabetical List of Companies

- Business Analysis Topics

Toyota’s Operations Management, 10 Critical Decisions, Productivity

Toyota Motor Corporation’s operations management (OM) covers the 10 decisions for effective and efficient operations. With the global scale of its automobile business and facilities around the world, the company uses a wide set of strategies for the 10 critical decisions of operations management. These strategies account for local and regional automotive market conditions, including the trends examined in the PESTLE analysis (PESTEL analysis) of Toyota . The automaker is an example of successful multinational operations management. These 10 decisions indicate the different areas of the business that require strategic approaches. Toyota also succeeds in emphasizing productivity in all the 10 decisions of operations management.

Toyota’s approaches for the 10 strategic decisions of operations management show the importance of coordinated efforts for ensuring streamlined operations and high productivity in international business. Successful operations management leads to high productivity, which supports competitive advantages over other automakers, such as Ford , General Motors , Tesla , BMW , and Hyundai. Nonetheless, these competitors continuously enhance their operations and create challenges to Toyota’s competitive advantages.

Toyota’s Operations Management, 10 Critical Decision Areas

1. Design of Goods and Services . Toyota addresses this strategic decision area of operations management through technological advancement and quality. The company uses its R&D investments to ensure advanced features in its products. Toyota’s mission statement and vision statement provide a basis for the types and characteristics of these products. Moreover, the automaker accounts for the needs and qualities of dealership personnel in designing after-sales services. Despite its limited influence on dealership employment, Toyota’s policies and guidelines ensure the alignment between dealerships and this area of the company’s operations management.

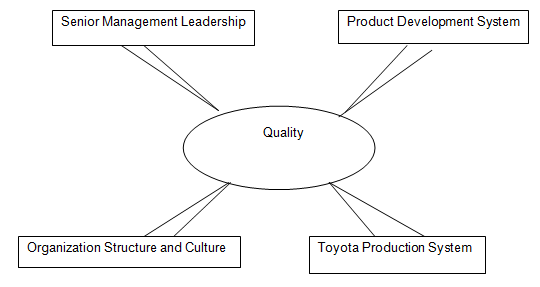

2. Quality Management . To maximize quality, the company uses its Toyota Production System (TPS). Quality is one of the key factors in TPS. Also, the firm addresses this strategic decision area of operations management through continuous improvement, which is covered in The Toyota Way, a set of management principles. These principles and TPS lead to high-quality processes and outputs, which enable innovation capabilities and other strengths shown in the SWOT analysis of Toyota . In this regard, quality is a critical success factor in the automotive company’s operations.

3. Process and Capacity Design . For this strategic decision area of operations management, Toyota uses lean manufacturing, which is also embodied in TPS. The company emphasizes waste minimization to maximize process efficiency and capacity utilization. Lean manufacturing helps minimize costs and supports business growth, which are objectives of Toyota’s generic strategy for competitive advantage and intensive strategies for growth . Thus, the car manufacturer supports business efficiency and cost-effectiveness in its process and capacity design. Cost-effective processes support the competitive selling prices that the company uses for most of its automobiles.