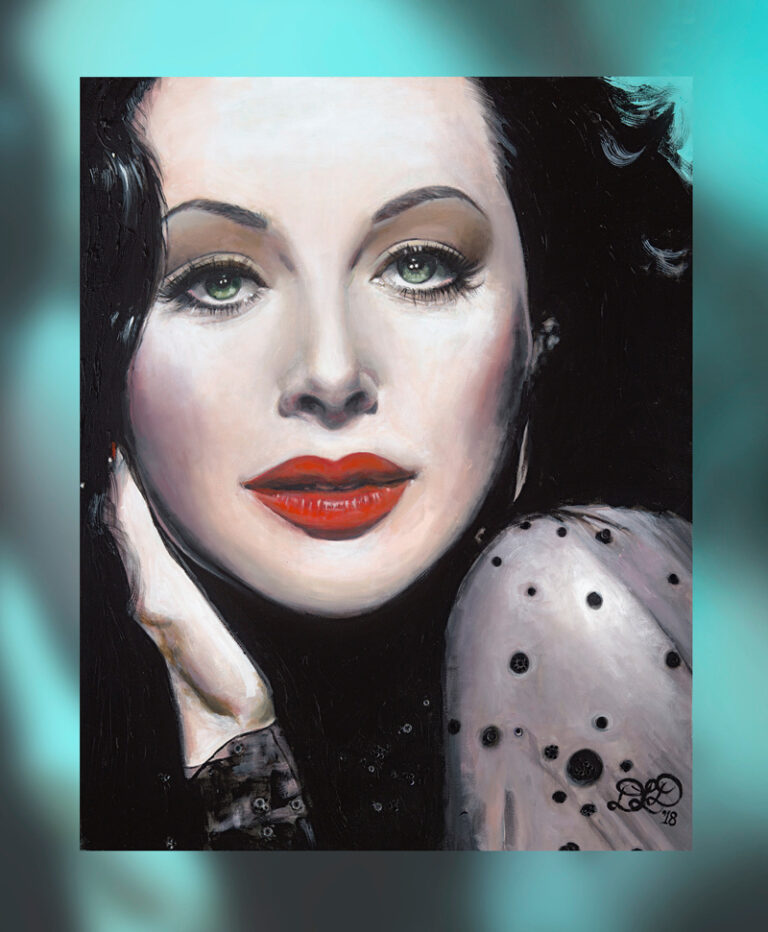

Hedy Lamarr

Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian American actress during MGM's "Golden Age" who also left her mark on technology. She helped develop an early technique for spread spectrum communications.

(1914-2000)

Who Was Hedy Lamarr?

Hedy Lamarr was an actress during MGM's "Golden Age." She starred in such films as Tortilla Flat, Lady of the Tropics, Boom Town and Samson and Delilah , with the likes of Clark Gable and Spencer Tracey. Lamarr was also a scientist, co-inventing an early technique for spread spectrum communications — the key to many wireless communications of our present day. A recluse later in life, Lamarr died in her Florida home in 2000.

Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler on November 9, 1914, in Vienna, Austria. Discovered by an Austrian film director as a teenager, she gained international notice in 1933, with her role in the sexually charged Czech film Ecstasy . After her unhappy marriage ended with Fritz Mandl, a wealthy Austrian munitions manufacturer who sold arms to the Nazis, she fled to the United States and signed a contract with the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio in Hollywood under the name Hedy Lamarr. Upon the release of her first American film, Algiers , co-starring Charles Boyer, Lamarr became an immediate box-office sensation.

'Secret Communications System'

In 1942, during the heyday of her career, Lamarr earned recognition in a field quite different from entertainment. She and her friend, the composer George Antheil, received a patent for an idea of a radio signaling device, or "Secret Communications System," which was a means of changing radio frequencies to keep enemies from decoding messages. Originally designed to defeat the German Nazis, the system became an important step in the development of technology to maintain the security of both military communications and cellular phones.

Lamarr wasn't instantly recognized for her communications invention since its wide-ranging impact wasn't understood until decades later. However, in 1997, Lamarr and Antheil were honored with the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) Pioneer Award, and that same year Lamarr became the first female to receive the BULBIE™ Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award, considered the "Oscars" of inventing.

Later Career

Lamarr's film career began to decline in the 1950s; her last film was 1958's The Female Animal , with Jane Powell. In 1966, she published a steamy best-selling autobiography, Ecstasy and Me , but later sued the publisher for what she saw as errors and distortions perpetrated by the book's ghostwriter. She was arrested twice for shoplifting, once in 1966 and once in 1991, but neither arrest resulted in a conviction.

Personal Life, Death and Legacy

Lamarr was married six times. She adopted a son, James, in 1939, during her second marriage to Gene Markey. She went on to have two biological children, Denise (b. 1945) and Anthony (b. 1947), with her third husband, actor John Loder, who also adopted James.

In 1953, Lamarr completed the naturalization process and became a U.S. citizen.

In her later years, Lamarr lived a reclusive life in Casselberry, a community just north of Orlando, Florida, where she died on January 19, 2000, at the age of 85.

Documentary and Pop Culture

In 2017, director Alexandra Dean shined a light on the Hollywood starlet/unlikely inventor with a new documentary, Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story . Along with delving into her pioneering technological work, the documentary explores other examples in which Lamarr proved to be far more than just a pretty face, as well as her struggles with crippling drug addiction.

A dramatized version of Lamarr featured in a March 2018 episode of the TV series Timeless , which centered on her efforts to help the time-traveling team recover a stolen workprint of the 1941 classic Citizen Kane .

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Hedy Lamarr

- Birth Year: 1914

- Birth date: November 9, 1914

- Birth City: Vienna

- Birth Country: Austria

- Best Known For: Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian American actress during MGM's "Golden Age" who also left her mark on technology. She helped develop an early technique for spread spectrum communications.

- Astrological Sign: Scorpio

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Hedy Lamarr was arrested twice for shoplifting, in 1966 and 1991, though neither arrest resulted in a conviction.

- Death Year: 2000

- Death date: January 19, 2000

- Death State: Florida

- Death City: Casselberry

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Hedy Lamarr Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/actors/hedy-lamarr

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: April 19, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Famous Actors

Jesse Plemons

Did You Know George Clooney Is a Director?

Get to Know ‘Bridgerton’ Star Nicola Coughlan

George Takei

Jackie Chan

Jason Momoa

Michelle Yeoh

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- What are some of the major film festivals?

Hedy Lamarr

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Jewish Women's Archive - Biography of Hedy Lamarr

- American Physical Society - Hedy Lamarr and George Antheil submit patent for radio frequency hopping

- Warfare History Network - Hedy Lamarr: Allied Inventor and Actress

- National Women's History Museum - Biograpghy of Hedy Lamarr

- Official Site of Hedy Lamarr

- PBS - Amercian Masters - Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story

- Famous Scientists - Biography of Hedy Lamarr

- Turner Classic Movies - Hedy Lamarr

- Hedy Lamarr - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Hedy Lamarr (born November 9, 1913/14, Vienna , Austria—died January 19, 2000, near Orlando , Florida , U.S.) was an Austrian-born American film star who was often typecast as a provocative femme fatale . Years after her screen career ended, she achieved recognition as a noted inventor of a radio communications device.

The daughter of a prosperous Viennese banker, Lamarr was privately tutored from age 4; by the time she was 10, she was a proficient pianist and dancer and could speak four languages. At age 16 she enrolled in Max Reinhardt ’s Berlin-based dramatic school, and within a year she made her motion picture debut in Geld auf der Strasse (1930; Money on the Street ). She achieved both stardom and notoriety in the Czech film Extase (1932; Ecstasy ), in which she briefly but tastefully appeared in the nude. Her burgeoning career was halted by her 1933 marriage to Austrian munitions manufacturer Fritz Mandl, who not only prohibited her from further stage and screen appearances but also tried unsuccessfully to destroy all existing prints of Extase . After leaving the possessive Mandl, she went to Hollywood in 1937, where she appeared in her first English-language film, the classic romantic drama Algiers (1938). Lamarr became a U.S. citizen in 1953.

Under contract to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer from 1938 to 1945, she displayed her acting skills in such films as H.M. Pulham, Esq. (1941) and Tortilla Flat (1942). For the most part, however, she was confined to mostly decorative roles, such as that of Tondelayo in White Cargo (1942). Hoping to secure more substantial parts, she set up her own production company in 1946, but within three years she returned to her exotic stock-in-trade in Cecil B. DeMille ’s Samson and Delilah (1949), her most commercially successful film.

Lamarr once insisted, “Any girl can be glamorous; all you have to do is stand still and look stupid.” That she herself was anything but stupid was unequivocally proved during World War II when, in collaboration with the avant-garde composer George Antheil , she invented an electronic device that minimized the jamming of radio signals. Though it was never used in wartime, this device is a component of present-day satellite and cellular phone technology .

Retiring from movies in 1958 (except for a cameo appearance in Instant Karma , 1990), Lamarr subsequently resurfaced in 1966 and 1991 when she was arrested on, and later cleared of, shoplifting charges; when she sued the collaborators on her 1966 autobiography Ecstasy and Me for misrepresentation; and when she took director Mel Brooks to court for including a character named Hedley Lamarr in his western spoof Blazing Saddles (1974). She was married six times (her husbands included screenwriter Gene Markey and actor John Loder) but was living alone at the time of her death.

Hedy Lamarr

Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian-American actress and inventor who pioneered the technology that would one day form the basis for today’s WiFi, GPS, and Bluetooth communication systems. As a natural beauty seen widely on the big screen in films like Samson and Delilah and White Cargo , society has long ignored her inventive genius.

Lamarr was originally Hedwig Eva Kiesler, born in Vienna, Austria on November 9 th , 1914 into a well-to-do Jewish family. An only child, Lamarr received a great deal of attention from her father, a bank director and curious man, who inspired her to look at the world with open eyes. He would often take her for long walks where he would discuss the inner-workings of different machines, like the printing press or street cars. These conversations guided Lamarr’s thinking and at only 5 years of age, she could be found taking apart and reassembling her music box to understand how the machine operated. Meanwhile, Lamarr’s mother was a concert pianist and introduced her to the arts, placing her in both ballet and piano lessons from a young age.

Lamarr’s brilliant mind was ignored, and her beauty took center stage when she was discovered by director Max Reinhardt at age 16. She studied acting with Reinhardt in Berlin and was in her first small film role by 1930, in a German film called Geld auf der Stra βe (“Money on the Street”). However, it wasn’t until 1932 that Lamarr gained name recognition as an actress for her role in the controversial film, Ecstasy .

Austrian munitions dealer, Fritz Mandl, became one of Lamarr’s adoring fans when he saw her in the play Sissy . Lamarr and Mandl married in 1933 but it was short-lived. She once said, “I knew very soon that I could never be an actress while I was his wife … He was the absolute monarch in his marriage … I was like a doll. I was like a thing, some object of art which had to be guarded—and imprisoned—having no mind, no life of its own.” She was incredibly unhappy, as she was forced to play host and smile on demand amongst Mandl’s friends and scandalous business partners, some of whom were associated with the Nazi party. She escaped from Mandl’s grasp in 1937 by fleeing to London but took with her the knowledge gained from dinner-table conversation over wartime weaponry.

While in London, Lamarr’s luck took a turn when she was introduced to Louis B. Mayer, of the famed MGM Studios. With this meeting, she secured her ticket to Hollywood where she mystified American audiences with her grace, beauty, and accent. In Hollywood, Lamarr was introduced to a variety of quirky real-life characters, such as businessman and pilot Howard Hughes.

Lamarr dated Hughes but was most notably interested with his desire for innovation. Her scientific mind had been bottled-up by Hollywood but Hughes helped to fuel the innovator in Lamarr, giving her a small set of equipment to use in her trailer on set. While she had an inventing table set up in her house, the small set allowed Lamarr to work on inventions between takes. Hughes took her to his airplane factories, showed her how the planes were built, and introduced her to the scientists behind process. Lamarr was inspired to innovate as Hughes wanted to create faster planes that could be sold to the US military. She bought a book of fish and a book of birds and looked at the fastest of each kind. She combined the fins of the fastest fish and the wings of the fastest bird to sketch a new wing design for Hughes’ planes. Upon showing the design to Hughes, he said to Lamarr, “You’re a genius.”

Lamarr was indeed a genius as the gears in her inventive mind continued to turn. She once said, “Improving things comes naturally to me.” She went on to create an upgraded stoplight and a tablet that dissolved in water to make a soda similar to Coca-Cola. However, her most significant invention was engineered as the United States geared up to enter World War II.

In 1940 Lamarr met George Antheil at a dinner party. Antheil was another quirky yet clever force to be reckoned with. Known for his writing, film scores, and experimental music compositions, he shared the same inventive spirit as Lamarr. She and Antheil talked about a variety of topics but of their greatest concerns was the looming war. Antheil recalled, “Hedy said that she did not feel very comfortable, sitting there in Hollywood and making lots of money when things were in such a state.” After her marriage to Mandl, she had knowledge on munitions and various weaponry that would prove beneficial. And so, Lamarr and Antheil began to tinker with ideas to combat the axis powers.

The two came up with an extraordinary new communication system used with the intention of guiding torpedoes to their targets in war. The system involved the use of “frequency hopping” amongst radio waves, with both transmitter and receiver hopping to new frequencies together. Doing so prevented the interception of the radio waves, thereby allowing the torpedo to find its intended target. After its creation, Lamarr and Antheil sought a patent and military support for the invention. While awarded U.S. Patent No. 2,292,387 in August of 1942, the Navy decided against the implementation of the new system. The rejection led Lamarr to instead support the war efforts with her celebrity by selling war bonds. Happy in her adopted country, she became an American citizen in April 1953.

Meanwhile, Lamarr’s patent expired before she ever saw a penny from it. While she continued to accumulate credits in films until 1958, her inventive genius was yet to be recognized by the public. It wasn’t until Lamarr’s later years that she received any awards for her invention. The Electronic Frontier Foundation jointly awarded Lamarr and Antheil with their Pioneer Award in 1997. Lamarr also became the first woman to receive the Invention Convention’s Bulbie Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award. Although she died in 2000, Lamarr was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for the development of her frequency hopping technology in 2014. Such achievement has led Lamarr to be dubbed “the mother of Wi-Fi” and other wireless communications like GPS and Bluetooth.

Bedi, Joyce. “A Movie Star, Some Player Pianos, and Torpedoes.” Smithsonian National Museum of American History: Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation, November 12, 2015.

Camhi, Leslie. “Hedy Lamarr’s Forgotten, Frustrated Career as a Wartime Inventor.” The New Yorker , December 3, 2017.

DeFore, John. “'Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story': Film Review | Tribeca 2017.” The Hollywood Reporter , April 25, 2017.

“Hedy Lamarr: Biography.” IMDb.com.

“Hedy Lamarr Biography.” Biography.com. April 2, 2014.

“'Most Beautiful Woman' By Day, Inventor By Night.” All Things Considered , NPR, November 22, 2011.

“Women in Science: How Hedy Lamarr Pioneered Modern Wi-Fi Technology.” TEDxUCLWomen. July 30, 2017.

Y.F.. “The incredible inventiveness of Hedy Lamarr.” The Economist, November 23, 2017.

APA: Cheslak, C. (2018, August 30). Hedy Lamarr. Retrieved from https://www.womenshistory.org/students-and-educators/biographies/hedy-lamarr

MLA: Cheslak, Colleen. “Hedy Lamarr.” Hedy Lamarr , National Women's History Museum, 30 Aug. 2018, www.womenshistory.org/students-and-educators/biographies/hedy-lamarr.

Chicago:Cheslak, Colleen. "Hedy Lamarr." Hedy Lamarr. August 30, 2018. https://www.womenshistory.org/students-and-educators/biographies/hedy-lamarr.

Rhodes, Richard. Hedy's Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World . New York: Doubleday, 2011.

Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story. Directed by Alexandra Dean. New York: Zeitgeist Films, November 24, 2017.

Related Biographies

Stacey Abrams

Abigail Smith Adams

Jane Addams

Toshiko Akiyoshi

Related background, mary church terrell , belva lockwood and the precedents she set for women’s rights, faith ringgold and her fabulous quilts, educational equality & title ix:.

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- What Is Cinema?

The Beautiful Brilliance of Hedy Lamarr

By Hadley Hall Meares

“I’ve never been satisfied. I’ve no sooner done one thing than I am seething inside me to do another thing,” Golden Age screen siren Hedy Lamarr once said .

And do things Lamarr did. The stunning star of classics including Algiers and Samson and Delilah was much more than the label she was given, “the most beautiful woman in the world.” Married six times, she was an actress, pioneering female producer, ski-resort impresario , painter, art collector, and groundbreaking inventor, whose important innovations are meticulously cataloged in Pulitzer Prize winner Richard Rhodes ’s 2012 book, Hedy’s Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World .

However, it was another book that would alter the course of Lamarr’s life. Ecstasy and Me: My Life as a Woman , ghostwritten by Cy Rice and Leo Guild (who was also ghostwriter of the notorious Barbara Payton tell-all I Am Not Ashamed ), was released in 1966 and immediately became a best seller.

Based on 50 hours of taped conversations with the eccentric, vulnerable Lamarr, Ecstasy and Me is a grotesquely fascinating chronicle of the way women have been sexualized, minimized, and trivialized throughout history. Though it’s classified as an autobiography, the book starts with a male psychologist proclaiming that the sex-positive Lamarr is “blissfully unaffected by moral standards that our contemporary culture declares acceptable,” and goes on nauseatingly from there.

Lurid, amorous encounters right out of a Roger Corman sexploitation film and sexual trauma disguised as titillation are the main foci of this supposed autobiography, though sometimes it breaks, bizarrely, for transcripts of conversations Lamarr recorded with a psychiatrist. Sprinkled in are standard Hollywood gossip—sometimes catty, occasionally kind portraits of everyone from Judy Garland and Clark Gable to Ingrid Bergman—and inane pronouncements such as “Why Americans suspect bidets, I’ll never know. They are the last word in cleanliness.”

In 2010’s definitive Beautiful: The Life of Hedy Lamarr , biographer Stephen Michael Shearer writes that those close to Lamarr believed some of the nonsexual stories in Ecstasy and Me were accurate, with Lamarr’s own voice occasionally breaking through the sensationalist muddle. But they also felt the outlandish sexual stories were complete lies. The reader gets the sense that while Lamarr may have said the things she’s quoted as saying, statements made while she might have been high shouldn’t have been taken at face value. It’s no wonder Lamarr would sue unsuccessfully in an attempt to stop the publication of Ecstasy and Me , which she labeled “fictional, false, vulgar, scandalous, libelous, and obscene.” As she told Merv Griffin in 1969, “That’s not my book.”

Lamarr was born Hedwig Kiesler in Vienna, Austria, in 1914, to an assimilated Jewish family . In Hedy’s Folly , Rhodes paints a captivating picture of the artistic, intellectual Vienna of Lamarr’s youth, exploring the forces that would shape her (and making the reader wish they could step back in time). While Lamarr’s cultured mother worried that her extraordinarily beautiful, bright, and headstrong only child would grow spoiled, her father, Emil, a prominent banker, coddled and cultivated his precious daughter. “He made me understand that I must make my own decisions, mold my own character, think my own thoughts,” Lamarr later recalled, per Rhodes.

Ecstasy and Me describes Lamarr’s adolescence as a tumultuous time, filled with the trauma of attempted rape, lurid sexual exploits at boarding school, and an affair with her friend’s father that produced “uncountable” orgasms. It fails to mention, though, that when she was a teenager, she was already learning mechanics, and had become a fearless self-promoter and a protégé of theatrical impresario Max Reinhardt.

Buy Ecstasy and Me on Amazon .

At the age of 17, Lamarr was cast in the film that catapulted her to international stardom and infamy: Ecstasy , the project that gave her purported autobiography its title. The movie includes a scene in which Lamarr (who was unaccompanied by her parents during shooting) swimming nude and simulating an orgasm—a first in film history. Some of the only affecting passages in Ecstasy and Me come when Lamarr describes the exploitation she suffered at the hands of powerful men while making films like these.

By Chris Murphy

By Julie Miller

By Ramin Setoodeh

Most disturbing are her allegations that Ecstasy director Gustav Machatý resorted to cruel methods to get the teenager’s reactive face during her love scene with costar Aribert Mog:

Aribert took over me, and the scene began again. Aribert slipped down out of range on one side. From down out of range on the other side, the director jabbed that pin into my buttocks “a little” and I reacted…. I remember one shot when the close-up camera caught my face in a distortion of real agony…and the director yelled happily “Ya, goot!”

In 1933, Lamarr married munitions manufacturer Fritz Mandl. “He had the most amazing brain…. There was nothing he did not know…. Ask him a formula in chemistry and he would give it to you,” she said, per Rhodes.

The union was an unhappy one, though Ecstasy and Me conveniently leaves out crucial details about her relationship to make Lamarr appear blameless. That book describes her marriage as a perverse fairy tale. The much older Mandl did not allow her to act; Lamarr soon found that life with him was little more than a prison, a “gilded cage.”

All of Lamarr’s biographers agree that Mandl was insanely controlling and jealous of his wife’s beauty and infamy. Incensed and embarrassed by Lamarr’s nudity in Ecstasy , he spent a large sum of money in an attempt to buy up all existing copies of the film (he failed).

But Lamarr was not entirely as hopeless as she is portrayed in Ecstasy and Me . Shearer writes in Beautiful that while married, Lamarr had an affair with her husband’s best friend, Prince Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg. And according to Rhodes, she was far from the stereotypical trophy wife. Lamarr listened carefully to talk of the German military’s technological innovations as she presided over grand dinners in Starhemberg’s home. One of the most intriguing aspects of Hedy’s Folly is the detailed insight it gives into the big-business world of munitions and armaments, and how it may have influenced Lamarr’s future inventions.

If both Ecstasy and Me and Hedy’s Folly sometimes read more like spy thrillers than nonfiction, it is because what came next for Lamarr was incontestably dramatic. Always a fabulist, Lamarr would tell numerous stories of her attempts to flee Mandl. In Ecstasy and Me, the chosen version is particularly outrageous: that Lamarr hired a maid who looked like her so that she could steal the maid’s identity and sneak out of the house using the servants’ entrance. Lamarr’s son would corroborate this unbelievable story in the excellent, nuanced 2017 documentary Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story .

Whatever the truth, though, she did escape—first to Paris, then to London. By 1937, Lamarr was headed to Hollywood, with a contract from MGM’s Louis B. Mayer. Ecstasy and Me paints the exec as a phony, lecherous ham whom Lamarr constantly outsmarts. One can only hope that is true.

By 1940, the newly christened Hedy Lamarr was a bona fide movie star. Disdainful of the Hollywood social whirl, she preferred painting or swimming with her good friend Ann Sothern. “Any girl can be glamorous,” she later said . “All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.”

Ecstasy and Me presents these years as times of endless lovemaking and rehashes tired tropes about movie making. But according to Rhodes, Lamarr’s real passions were her inventions. She spent countless nights tinkering in a corner of her Benedict Canyon mansion, which contained drafting boards and gadgets galore. “My mother was very bright minded,” her son Anthony Loder later told the L.A. Times . “She always had solutions. Anytime someone complained about anything, boom, her mind came up with a solution.”

According to that same paper, while dating Howard Hughes, Lamarr worked on plans to streamline his airplanes. She also invented a bouillon cube that produced cola when dropped in plain water. But her real contribution to science arose out of a chance meeting with the flamboyant avant-garde composer and amateur inventor George Antheil (who is heavily profiled in Hedy’s Folly —so much that it makes the reader wish Rhodes would just get back to Lamarr’s story) at the home of movie star Janet Gaynor.

Antheil would later say that Lamarr was initially interested in his claim that he could make her breasts bigger (bosoms are a preoccupation in Ecstasy and Me as well). But the two soon turned their focus to helping the war effort, and began work on an invention based on Lamarr’s theory of “frequency hopping,” which could stop radio systems from being jammed by the enemy, aiding in torpedo launches. In August 1942, the government issued its “secret communication system,” U.S. patent No. 2,292,387. This system would later be used by the U.S. Navy and would be highly influential.

If Hedy’s Folly is sometimes bogged down by scientific and mechanical details, it is at least an overdue overcorrection. Books like Rhodes’s are a necessary revaluation of historical women’s roles as thinkers and game changers, contrasting the narrative that their lives were guided only by romance, physical appearance, and children. It is almost impossible to believe that in 50 hours of interviews, Lamarr never mentioned inventing—but in Ecstasy and Me , her passion is not mentioned once.

So why did this curious, ingenious woman agree to participate in Ecstasy and Me in the first place? By the mid-1960s, Lamarr’s movie stardom and six tumultuous marriages were firmly in the past. She claimed to be broke, and according to the documentary Bombshell, was addicted to methamphetamines ( she was a patient of Max Jacobson, the notorious “ Dr. Feelgood ”). In 1966, Lamarr was arrested at the May Company department store in Los Angeles for allegedly stealing items including two strings of beads, a lipstick brush, and an eye makeup brush. She was later acquitted .

According to Beautiful: The Life of Hedy Lamarr , Lamarr received a total of $80,000 for Ecstasy and Me . She signed off on the manuscript without reading it, legally paving the way for its publication.

It was a grave error. The book’s torrid passages are written like classic pornography; they include tales of orgies on sets with starlets and assistant directors, sadomasochism, and a strange story of one lover who had sex with a doll that he had made to look like Lamarr while she watched in horror.

It also includes a few interesting passages discussing her role as a groundbreaking film producer, and defensive yet amusing retellings of her bizarre behavior during her divorce from millionare Texas oilman W. Howard Lee (she sent her stand-in to testify for her in court). But the sex is was what stuck.

Once Lamarr actually bothered to read Ecstasy and Me , she knew her career was done. “I was there when she read Ecstasy and Me for the first time,” TCM’s Robert Osborne recalls in Beautiful . “She was shocked by it. But that was the foolish side of her. She wanted money. They simply made up passages in that book and she allowed them to…. It was part of her capriciousness, giving away parts of her life for a book and not worrying about the consequences.”

Although presiding judge Ralph H. Nutter believed Ecstasy and Me was “filthy, nauseating, and revolting,” he ruled against Lamarr, and the book was published anyway. “The damage it did to Hedy’s career and reputation was irreversible,” Shearer writes in Beautiful . Reading it, one instantly understands why. The cool Austrian film goddess had been knocked off her pedestal, presenting herself (intentionally or not) as a self-professed “nymphomaniac” and an irrational, self-obsessed has-been who bemoans the curse of her great beauty one too many times.

Lamarr eventually moved to Florida. Unable to cope with aging, she became a recluse, obsessed with plastic surgery and pushing her doctors to innovate new techniques in the field. “Hedy retreated from the gazes of those who didn’t look deeper. She…filled her days with activities (and lawsuits) and, with the humor still intact, tolerated the rest of us,” Osborne writes in the forward to Beautiful .

Lamarr rarely saw her children or friends, but instead talked to them on the telephone for hours every day. She also claimed she was writing her autobiography, seemingly trying to erase the pain and embarrassment of Ecstasy and Me from her memory.

As Lamarr hid away, her wartime work in frequency hopping was becoming extremely important. It paved the way for Wi-Fi, cellular technology, and modern satellite systems. Lamarr was aware of these uses, and bitter that her work had not been recognized—nor had she received a cent for her contributions. “I can’t understand why there’s no acknowledgment when it’s used all over the world,” she said in an influential 1990 Forbes interview , which slowly began to wake the world up to her accomplishments.

In 1997, three years before her death, Lamarr was finally honored with the prestigious Pioneer Award from the Electronic Frontier Foundation. When she heard of the award, she said to her son simply this: “It’s about time.”

Perhaps it is fitting that it has been so hard to tell Lamarr’s entire story until recently; an extraordinarily beautiful, troubled, brilliant, sexually liberated woman has long been too much for patriarchal society to handle. This is something Lamarr seemed to understand. In a 1969 interview, she explained it to a befuddled Merv Griffin: “I’m a very simple, complicated person.”

All products featured on Vanity Fair are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

— “Who the Fuck Cares About Adam McKay?” (We Do, and With Good Reason) — The 10 Best Movies of 2021 — The Goldbergs Actor Jeff Garlin Responds to Talk of Misbehavior on Set — We Still Love 30 Rock , but Its Foundation Is Shaky — Our TV Critic’s Favorite Shows of the Year — Mel Brooks Went Too Far —But Only Once — Lady Gaga’s House of Gucci Character Is Even Wilder in Real Life — From the Archive: Inside the Crazy Ride of Producing The Producers — Sign up for the “HWD Daily” newsletter for must-read industry and awards coverage—plus a special weekly edition of “Awards Insider.”

Hadley Hall Meares

By David Canfield

By Silvana Paternostro

By Tara Ariano

By Donald Liebenson

By Joy Press

By Keziah Weir

By Dan Adler

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How Hollywood Star Hedy Lamarr Invented the Tech Behind WiFi

By: Dave Roos

Published: March 5, 2024

In the 1940s, few Hollywood actresses were more famous and more famously beautiful than Hedy Lamarr. Yet despite starring in dozens of films and gracing the cover of every Hollywood celebrity magazine, few people knew Hedy was also a gifted inventor. In fact, one of the technologies she co-invented laid a key foundation for future communication systems, including GPS, Bluetooth and WiFi.

“Hedy always felt that people didn't appreciate her for her intelligence—that her beauty got in the way,” says Richard Rhodes, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian who wrote a biography about Hedy.

After working 12- or 15-hour days at MGM Studios, Hedy would often skip the Hollywood parties or carousing with one of her many suitors and instead sit down at her “inventing table.”

“Hedy had a drafting table and a whole wall full of engineering books. It was a serious hobby,” says Rhodes, author of Hedy's Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World .

While not a trained engineer or mathematician, Hedy Lamarr was an ingenious problem-solver. Most of her inventions were practical solutions to everyday problems, like a tissue box attachment for depositing used tissues or a glow-in-the-dark dog collar.

It was during World War II , that she developed “frequency hopping,” an invention that’s now recognized as a fundamental technology for secure communications. She didn’t receive credit for the innovation until very late in life.

Hedy Lamarr's Childhood in Austria

Hedy Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Kiesler in Vienna, Austria in 1914. She was the only child of a wealthy secular Jewish family. From her father, a bank director, and her mother, a concert pianist, Hedy received a debutante’s education—ballet classes, piano lessons and equestrian training.

There were signs at a young age that Hedy had an engineer’s natural curiosity. On long walks through the bustling streets of Vienna, Hedy’s father would explain how the streetcars worked and how their electricity was generated at the power plant. At five years old, Hedy took apart a music box and reassembled it piece by piece.

“Hedy did not grow up with any technical education, but she did have this personal connection,” says Rhodes. “She loved her father dearly, so it’s easy to see how from that she might have developed an interest in the subject. And also it prepared her to be what she really was, a kind of amateur inventor.”

Hedy's Movie Debut as Teen

Even if Hedy had wanted to be a professional engineer or scientist, that career path wasn’t available to Viennese girls in the 1930s. Instead, teenage Hedy set her sights on the movie industry.

“At 16,” says Rhodes, “Hedy forged a note to her teachers in Vienna saying, ‘My daughter won’t be able to come to school today,’ so she could go down to the biggest movie studio in Europe and walk in the door and say, ‘Hi, I want to be a movie star.’”

Hedy started as a script girl, but quickly earned some walk-on parts. The Austrian director Max Reinhardt took Hedy to Berlin when she starred in a few forgettable films before landing a role at age 18 in a racy film called Ecstasy by the Czech director Gustav Machatý. The film was denounced by Pope Pious XI, banned from Germany and blocked by US Customs authorities for being “dangerously indecent.”

Reinhardt called Hedy “the most beautiful woman in Europe,” and even before Ecstasy , Hedy was turning heads in theater productions across Europe. It was during the Viennese run of a popular play called Sissy that Hedy caught the eye of a wealthy Austrian munitions baron named Fritz Mandl. Hedy and Mandl married in 1933, but the union was stifling from the start. Mandl forced his wife to accompany him as he struck deals with customers, including officials from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, including Mussolini himself.

“She would sit at dinner bored out of her mind with discussions of bombs and torpedoes, and yet she was also absorbing it,” says Rhodes. “Of course, nobody asked her any questions. She was supposed to be beautiful and silent. But I think it was through that experience that she developed her considerable knowledge about how torpedo guidance worked.”

In 1937, Hedy fled her unhappy marriage (Mandl was deeply paranoid that Hedy was cheating on him) and also fled Austria, a country aligned with Adolf Hitler’s anti-Jewish policies.

A New Country and a New Name

Hedy landed in London, where Louis B. Mayer of MGM Studios was actively buying up the contracts of Jewish actors who could no longer work safely in Europe. Hedy met with Mayer, but refused his lowball offer of $125 a week for an exclusive MGM contract. In a savvy move, Hedy booked passage to the United States on the luxury liner SS Normandie , the same ship on which Mayer was traveling home.

“She made a point of being seen on deck looking beautiful and playing tennis with some of the handsome guys on board,” says Rhodes. “By the time they got to New York, Hedy had cut a much better deal with Mayer”—$500 a week—“with the proviso that she’d learn how to speak English in six months.”

Mayer had another demand—she had to change her name. Hedwig Kiesler was too German-sounding. Mayer’s wife was a fan of 1920s actress Barbara La Marr (who died tragically at 29 years old), so Mayer decided that his new MGM actor would now be known as Hedy Lamarr.

Actress by Day, Inventor by Night

It didn’t take long for Hedy to emerge as a bright new star in Hollywood. Her breakout role was alongside Charles Boyer (another European transplant) in Algiers (1938). From there, the MGM machine put Hedy to work cranking out multiple feature films a year throughout the 1940s.

“Any girl can be glamorous,” Hedy once quipped. “All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.”

As much as Hedy enjoyed her Hollywood stardom, her first love was still tinkering and problem-solving. She found a kindred spirit in Howard Hughes, the film producer and aeronautical engineer. When Hedy shared an idea for a dissolvable tablet that could turn a soldier’s canteen into a soft drink, Hughes lent her a few of his chemists.

But most of Hedy’s work was done at home at her engineering table where she’d sketch designs for creative solutions to practical problems. In addition to the tissue box attachment and the light-up dog collar, Hedy devised a special shower seat for the elderly that swiveled safely out of a bathtub.

“She was an inventor,” says Rhodes. “If you’ve ever been around real inventors, they’re often not people with a particularly deep education. They’re people who think about the world in a certain way. When they find something that doesn’t work right, instead of just swearing or whatever the rest of us do, they figure out how to fix it.”

Lamarr Takes on German U-Boats

In 1940, Hedy was distraught by the news coming out of Europe, where the Nazi war machine was steadily gaining territory and German U-boat submarines were wreaking havoc in the Atlantic. This was a far more difficult problem to fix, but Hedy was determined to do her part in the war effort.

The turning point came when Hedy met a man at a dinner party. George Antheil was an avante-garde music composer who lost his brother in the earliest days of the war. Antheil and Hedy were kindred spirits—two brilliant, if unconventional minds dead set on finding a way to defeat Hitler. But how?

That’s when Rhodes thinks Hedy leaned on the knowledge she picked up years earlier during those boring client dinners with her first husband in Vienna.

“She knew about torpedoes,” says Rhodes. “She knew there was a problem aiming torpedoes. If the British could take out German submarines with torpedoes launched from surface ships or airplanes, they might be able to prevent all of this slaughter that was going on.”

The answer was clearly some type of radio-controlled torpedo, but how would they stop the Germans from simply jamming the radio signal? Hedy and Antheil’s creative solution was inspired, Rhodes believes, by their mutual love of the piano.

Lamarr, Antheil Harness Music to Inspire Invention

During their late-night brainstorming sessions, Hedy and Antheil played a musical game. They’d sit down at the piano together, one person would start playing a popular song and the other would see how quickly they could recognize it and start playing along.

It was here, Rhodes thinks, that Hedy and Antheil first happened upon the idea of frequency hopping. If two musicians are playing the same music, they can hop around the keyboard together in perfect sync. However, if someone listening doesn’t know the song, they have no idea what keys will be pressed next. The “signal,” in other words, was hidden in the constantly changing frequencies.

How did this apply to radio-controlled torpedoes? The Germans could easily jam a single radio frequency, but not a constantly changing “symphony” of frequencies.

In his experimental musical compositions, Antheil had written songs for multiple synchronized player pianos. The pianos played in sync because they were fed the same piano rolls—a type of primitive, cut-out paper program—that controlled which keys were played and when. What if he and Hedy could invent a similar method for synchronizing communications between a torpedo and its controller on a nearby ship?

“All you need are two synchronized clocks that start a tape going at the same moment on the ship and inside the torpedo,” says Rhodes. “The signal between the ship and the torpedo would be continuous, even though it was traveling across a new frequency every split second. The effect for anyone trying to jam the signal is that they wouldn’t know where it was from one moment to the next, because it would ‘hopping’ all over the radio.”

It was Hedy who named their clever system “frequency hopping.”

Navy Rejects Invention

Hedy and Antheil developed their idea with the help of a wartime agency called the National Inventors’ Council , tasked with applying civilian inventions to the war effort. The Council connected Hedy and Antheil with a physicist from the California Institute of Technology who figured out the complex electronics to make it all work.

When their frequency hopping patent was finalized in 1942, Antheil pitched the idea to the U.S. Navy, which was less than receptive.

“What do you want to do, put a player piano in a torpedo? Get out of here!” is how Rhodes describes the Navy’s knee-jerk rejection. It was never given a chance.

Hedy and Antheil’s patent was locked in a safe and labeled “top secret” for the remainder of the war. The two entertainers went back to their day jobs, thinking that was the end of their inventing days. Little did they know that their patent would have a second life.

Frequency Hopping Tech Takes Off

In the 1950s, the electrical manufacturer Sylvania employed frequency hopping to build a secure system for communicating with submarines. And in the early 1960s, the technology was deployed on U.S. warships to prevent Soviet signal jamming during the Cuban Missile Crisis .

Antheil died in 1959, but Hedy lived on, unaware that her ingenious idea was about to take off in a big way.

When car phones first became popular in the 1970s, carriers used frequency hopping to enable hundreds of callers to share a limited spectrum of radio frequencies. The same technology was rolled out for the earliest cell phone networks.

By the 1990s, frequency hopping was so ubiquitous that it became the technology standard required by the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for secure radio communications. That’s why Bluetooth, WiFi and other essential technologies are based, at their core, on an idea dreamed up by Hedy Lamarr and George Antheil.

“It’s a really deep and fundamental idea,” says Rhodes. “It has broad applications all over the place.”

Over time, Hedy’s Hollywood star fizzled and she retired to Florida, where she continued to tinker with new inventions, including a more “driver-friendly” type of traffic light. It wasn’t until Hedy was in her 80s that a group of engineers realized that the “Hedwig Kiesler Mackay” listed on the frequency hopping patent was none other than the Hollywood legend, Hedy Lamarr.

“Hedy didn’t want money, but she did want recognition,” says Rhodes, “and it really angered her that nobody gave her credit for this important invention. In the 1990s, she finally got an award for her contribution. And Hedy being Hedy, what did she say? ‘Well, it’s about time.’”

HISTORY Vault: Women's History

Stream acclaimed women's history documentaries in HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Site Navigation

Hedy Lamarr: Golden Age Film Star—and Important Inventor

Actor Hedy Lamarr (1914–2000) had a fascinating life, including her scandalous debut in the Czech film Ecstasy, discovery (and renaming) by Louis B. Mayer, persona as the most glamorous woman of Hollywood's Golden Age, and relative obscurity in her later years.

But far beyond the Hollywood image, Lamarr was an inventor.

She was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Vienna, Austria. Her father was the director of a bank and her Hungarian mother was a concert pianist.

During a small dinner party in 1940, Lamarr met a kindred inventive spirit in George Antheil. The Trenton, New Jersey, native was known for his writing, his film scores—especially his avant-garde music compositions—but he was also an inventor.

Lamarr wanted to aid the Allied forces during World War II. She explored potential military applications for radio technology. She theorized that varying radio frequencies at irregular intervals would prevent interception or jamming of transmissions, thereby creating an innovative communication system.

Lamarr shared her concept for using “frequency hopping” with the U.S. Navy and codeveloped a patent with Antheil 1941. Today, her innovation helped make possible a wide range of wireless communications technologies, including Wi-Fi, GPS, and Bluetooth.

This image is in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Read more about Lamarr’s story and inventions in this blog post by Joyce Bedi for the museum’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation.

An image of Lamarr’s patent can be viewed online at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

Collections

- Open Access

Billions and Billions of Periodical Cicadas

Hedy Lamarr

Celebrated as “the most beautiful woman in the world” during her Hollywood heyday in the 1940s, film star Hedy Lamarr (1914–2000) ultimately proved that her brain was even more extraordinary than her beauty. Eager to aid Allied forces during World War II, she explored potential military applications for radio technology. She theorized that varying radio frequencies at irregular intervals would prevent interception or jamming of transmissions, thereby creating an innovative communication system. Lamarr shared her concept for utilizing “frequency hopping” with the U.S. Navy and codeveloped a patent in 1941. Today, Lamarr’s innovation makes possible a wide range of wireless communications technologies, including Wi-Fi, GPS, and Bluetooth.

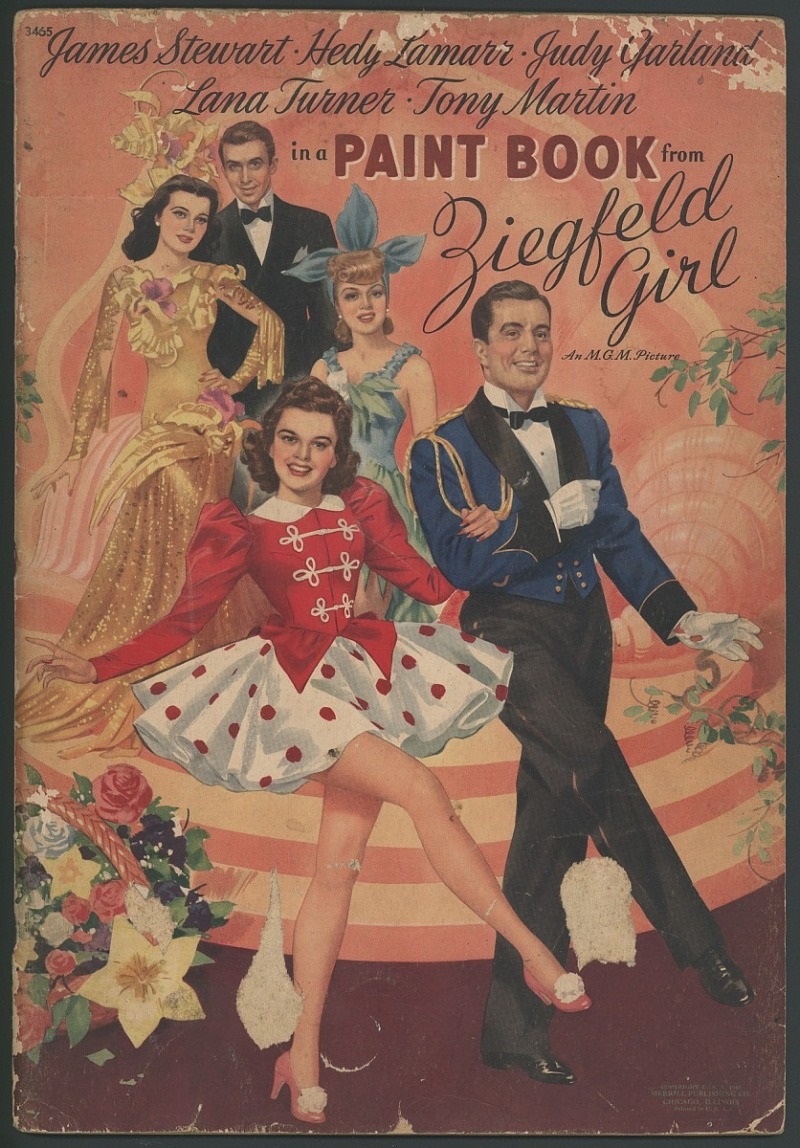

James Stewart, Hedy Lamarr, Judy Garland, Lana Turner, and Tony Martin in a Paint Book from Ziegfeld Girl

Object details.

Hedy Lamarr (1914-2000)

Additional crew.

IMDbPro Starmeter Top 5,000 231

- 4 wins & 1 nomination

- Jenny Hager

- Princess Veronica

- Dolores Sweets Ramirez

- Vanessa Windsor

- Consuela Bowers

- Joan of Arc

- (scenes deleted)

- Imperatrice Giuseppina

- Genoveffa di Brabante

- Hedy Windsor

- Elana di Troia

- Empress Josephine ...

- Lily Dalbray

- Marianne Lorress

- Lisa Roselle

- Dr. J.O. Loring

- Madeleine Damien

- executive producer

- stand-in: Nancy Kelly (uncredited)

Personal details

- Official Site

- Hedwig Kiesler

- 5′ 7″ (1.70 m)

- November 9 , 1914

- Vienna, Austria-Hungary [now Austria]

- January 19 , 2000

- Casselberry, Florida, USA (natural causes)

- Spouses Lewis William Boies Jr. March 4, 1963 - June 21, 1965 (divorced)

- Children James Lamarr Markey

- Parents Emil Kiesler

- Other works (7/13/42) Radio: Appeared in a "Lux Radio Theater" production of "H.M. Pulham, Esq."

- 3 Biographical Movies

- 9 Print Biographies

- 4 Portrayals

- 17 Articles

- 28 Pictorials

- 18 Magazine Cover Photos

Did you know

- Trivia Inspired by an early Philco wireless radio remote and player piano rolls, she worked with composer George Antheil (who created a symphony played by eight synchronized player pianos) she invented a frequency-hopping system for remotely controlling torpedoes during World War II. (The frequency hopping concept appeared as early as 1903 in a U.S. Patent by Nikola Tesla). The invention was examined superficially and filed away. At the time, Allied torpedoes, as well as those of the Axis powers, were unguided. Input for depth, speed, and direction were made moments before launch but once leaving the submarine the torpedo received no further input. In 1959 it was developed for controlling drones that would later be used in Viet Nam. Frequency hopping radio became a Navy standard by 1960. Due to the expiration of the patent and Lamarr's unawareness of time limits for filing claims, she was never compensated. Her invention is used today for WiFi, Bluetooth, and even top secret military defense satellites. While the current estimate of the value of the invention is approximately $30 billion, during her final years she was getting by on SAG and social security checks totaling only $300 a month.

- Quotes I must quit marrying men who feel inferior to me. Somewhere, there must be a man who could be my husband and not feel inferior. I need a superior inferior man.

- Trademarks Natural brunette hair

- Hollywood's Loveliest Legendary Lady

- Queen of Glamour

- Salaries A Lady Without Passport ( 1950 ) $90,000

- When did Hedy Lamarr die?

- How did Hedy Lamarr die?

- How old was Hedy Lamarr when she died?

Related news

Contribute to this page.

- Learn more about contributing

More to explore

Recently viewed.

Hedy Lamarr

Golden Age Film Actress and Inventor of Frequency-Hopping Technology

Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

- People & Events

- Fads & Fashions

- Early 20th Century

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- Women's History

Hedy Lamarr was a film actress of Jewish heritage during MGM ’s “Golden Age.” Deemed “the most beautiful woman in the world” by MGM publicists, Lamarr shared the silver screen with stars like Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy. Yet Lamarr was much more than a pretty face, she also is credited with inventing frequency-hopping technology.

Early Life and Career

Hedy Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler on November 9, 1914, in Vienna, Austria. Her parents were Jewish, with her mother, Gertrud (née Lichtwitz) being a pianist (rumored to have converted to Catholicism ) and her father Emil Kiesler, a successful banker. Lamarr’s father loved technology and would explain how everything from streetcars to printing presses worked. His influence no doubt led to Lamarr’s own enthusiasm for technology later in life.

As a teen Lamarr became interested in acting and in 1933 she starred in a film titled " Ecstasy ." She played a young wife, named Eva, who is trapped in a loveless marriage to an older man and who eventually begins an affair with a young engineer. The film generated controversy because it included scenes that would be tame by modern standards: a glance of Eva’s breasts, a shot of her running naked through the forest, and an up close shot of her face during a love scene.

Also in 1933, Lamarr married a wealthy, Vienna-based arms manufacturer named Friedrich Mandl. Their marriage was an unhappy one, with Lamarr reporting in her autobiography that Mandl was extremely possessive and isolated Lamarr from other people. She would later remark that during their marriage she was given every luxury except freedom. Lamarr despised their life together and after attempting to leave him in 1936, fled to France in 1937 disguised as one of her maids.

The Most Beautiful Woman in the World

From France, she went on to London, where she met Louis B. Mayer, who offered her an acting contract in the United States.

Before long, Mayer convinced her to change her name from Hedwig Kiesler to Hedy Lamarr, inspired by a silent film actress who had died in 1926. Hedy signed a contract with the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) studio, which dubbed her “The Most Beautiful Woman in the World." Her first American film, Algiers , was a box office hit.

Lamarr went on to make many other films with Hollywood stars such as Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy ( Boom Town ) and Victor Mature ( Samson and Delilah ). During this period, she married screenwriter Gene Markey, though their relationship ended in divorce in 1941.

Lamarr would eventually have six husbands in all. After Mandl and Markey, she married John Lodger (1943-47, actor), Ernest Stauffer (1951-52, restaurateur), W. Howard Lee (1953-1960, Texas oilman), and Lewis J. Boies (1963-1965, lawyer). Lamarr had two children with her third husband, John Lodger: a daughter named Denise and a son named Anthony. Hedy kept her Jewish heritage a secret throughout her life. In fact, it was only after her death that her children learned they were Jewish.

The Invention of Frequency Hopping

One of Lamarr’s greatest regrets was that people rarely recognized her intelligence. “Any girl can be glamorous,” she once said. “All you have to do is stand still and look stupid."

Lamarr was a naturally gifted mathematician and during her marriage to Mandl had become familiar with concepts related to military technology. This background came to the forefront in 1941 when Lamarr came up with the concept of frequency hopping. In the midst of World War II , radio-guided torpedoes did not have a high success rate when it came to hitting their targets. Lamarr thought frequency hopping would make it harder for enemies to detect a torpedo or intercept its signal. She shared her idea with a composer named George Antheil (who at one time had been a government inspector of U.S. munitions and who had already composed music that used the remote control of automated instruments), and together they submitted her idea to the U.S. Patent Office. The patent was filed in 1942 and published in 1942 under H.K. Markey et. al.

Though Lamarr's concept would ultimately revolutionize technology, at the time the military did not want to accept military advice from a Hollywood starlet. As a result, her idea was not put into practice until the 1960s after her patent had expired. Today, Lamarr’s concept is the basis of spread-spectrum technology, which is used for everything from Bluetooth and Wi-Fi to satellites and wireless phones.

Later Life and Death

Lamarr’s film career began to slow in the 1950s. Her last movie was The Female Animal with Jane Powell. In 1966, she published an autobiography titled Ecstasy and Me, which went on to become a best seller. She also received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

In the early 1980s, Lamarr moved to Florida where she died, largely a recluse, of heart disease on January 19, 2000, at the age of 86. She was cremated and her ashes were scattered in the Vienna Woods.

- History's 15 Most Famous Inventors

- Who Invented Bluetooth?

- Sarah Bernhardt: Groundbreaking Actress of the 19th Century

- Women Celebrities of World War II

- Biography of Arthur Miller, Major American Playwright

- Biography of Lillian Hellman, Playwright Who Stood Up to the HUAC

- Achievements and Inventions of Women in History

- Interracial Celebrity Couples Today and in History

- Black American Firsts in Film and Theatre

- Biography of Margaret Bourke-White

- Biography of Lena Horne

- Eliza Haywood

- Biography of Cary Grant, Famous Leading Man

- Biography of Helen of Troy, Cause of the Trojan War

- Biography of Dorothy Parker, American Poet and Humorist

- Biography of Anne Frank, Writer of Powerful Wartime Diary

Watch CBS News

Actress Hedy Lamarr Dead At 86

January 19, 2000 / 2:42 PM EST / AP

Hedy Lamarr, the Austrian-born actress whose exotic glamour and sex appeal sparked a string of hit films of the '30s and '40s, was found dead in her home Wednesday. She was 86.

Lamarr's death was being investigated, a routine manner in an unattended death, said Steve Olson, a spokesman for the Seminole County Sheriff's Office. The death was not suspicious, he said.

She was billed as the world's most beautiful woman. Her pale skin, almond eyes and dark hair gave her an exotic look, and her films included Tortilla Flat, in which she played a part-Mexican woman; White Cargo, playing the slave woman Tondelayo; and Lady of the Tropics.

She was reputedly producer Hal Wallis' first choice for the heroine Ilsa in the 1943 classic Casablanca, the part that eventually went to Ingrid Bergman.

But she claimed to scorn the glamorous image. In a 1942 Associated Press interview, she showed a reporter her house, complete with hen house and homemade curtains, and implored: "Now you will not write I am a glamour girl?" '

"Any girl can be glamorous," she once said. "All you have to do is stand still and look stupid."

Among Lamarr's leading men were William Powell ( Crossroads, The Heavenly Body ); Spencer Tracy ( Boom Town, Tortilla Flat ); Clark Gable ( Comrade X, also in Boom Town ); Robert Taylor ( Lady of the Tropics ); and Ray Milland ( Copper Canyon ).

She first achieved international fame and notoriety as a result of the 1933 Czech film Ecstasy, in which she acted in a steamy love scene and appeared nude in a 10-minute swimming sequence.

Hollywood was decades away from such frankness, but it knew a beautiful face and it knew the value of the publicity Ecstasy engendered.

After a few years away from the camera as the wife of Fritz Mandl, an Austrian munitions magnate, Lamarr was signed by MGM and brought to the United States in 1937. Her new screen name was said to be an homage to the 1920s screen beauty Barbara La Marr.

Her American film debut came in 1938 with Algiers, co-starring Charles Boyer. She played a wealthy adventuress and became a box-office sensation despite grousing by Boyer that she couldn't act.

In its review, the show biz paper Variety disagreed. "She brings to the picture an abundance of good looks, acting talent and enticement," its review said, praising her mastery of English and adding that with a little encouragement, "nothing apparently stands between her and success in Hollywood films."

One of her most successful films was Paramount's 1949 Samson and Delilah, directed by Cecil B. DeMille with Victor Mature as Samson. She got a rare chance to try her hand at comedy in My Favorite Spy, a 1951 Bob Hope film.

Her career faded in the middle '50s, when she appeared in some Italian productions. Her lasfilm was The Female Animal with Jane Powell in 1958.

She said her career suffered because she wouldn't sleep with a VIP just to get ahead. "My problem is I'm a hell of a nice dame," she said in a 1970 interview. "The most horrible whores are famous. I did what I did for love. The others did it for money."

Her lurid 1966 autobiography Ecstasy and Me, filled with sexy anecdotes including a couple involving other women, became a best-seller. But she later sued, saying the manuscript prepared by the ghostwriter was full of distortions and outright errors.

Another side of her was described in the 1992 book Feminine Ingenuity. Drawing upon knowledge about military products that she picked up while married to Mandl, Lamarr came up with the idea of a radio signaling device that would reduce the danger of detection or jamming. She and a friend, composer George Antheil, developed the idea further and received a patent in 1942.

The method was not used in the war, but since the '80s, high-tech versions of the concept, called "spread spectrum," have been used in some cordless phones, military radios and wireless computer links.

Lamarr is a "huge part of the history of this industry," Proxim Inc. Chief Executive David C. King told The Wall Street Journal in 1997. His company introduced a circuit board with spread spectrum in 1989 and later put out hundreds of products using the technology.

The daughter of a banker, Lamarr was born Hedwig Kiesler in Vienna on Nov. 9, 1913, although some references say 1914 or 1915. Discovered as a teen-ager by Austrian director Max Reinhardt, she began in films as a script secretary and bit player.

She was married and divorced six times to Mandl, screenwriter Gene Markey, actor John Loder, nightclub owner Ernest Stauffer, oil millionaire W. Howard Lee, and lawyer Lewis W. Boies Jr.

She adopted a son, James, and had two children with Loder, Anthony and Denise.

A pair of shoplifting arrests (neither of which resulted in convictions) caused headlines in her later years.

She was acquitted by a jury in Los Angeles on charges of stealing $86 worth of merchandise from a department store in 1966.

In August 1991, she was arrested and accused of stealing $21.48 worth of merchandise from a drugstore in Casselberry, Fla. She said she and a companion forgot to put the items in their shopping cart. Lamarr was never formally charged.

"I'm sick and tired of being in the limelight," Lamarr told a New York radio station after the second incident.

Her daughter, Denise Loder Deluca, said her mother was deluged by sympathetic calls after the Florida arrest. "It warms my heart that people care," she said at the time. "But she isn't down and out, and she doesn't need help."

In recent years, the once-celebrated movie queen lived quietly in a suburb of Orlando. Friends had said she ws legally blind and did not venture out on her own.

More from CBS News

- World Biography

- Supplement (Ka-Mé)

Hedy Lamarr Biography

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); Austrian-born American actress Hedy Lamarr (1913–2000) was among the leading screen sirens of Hollywood in the 1940s. Her life was an eventful one that involved six marriages, a groundbreaking electronic invention, and several cinematic milestones.

Born to Bank Director and Pianist

Lamarr was born Hedwig Kiesler in Vienna, Austria, on November 9, 1913. Her family was Jewish and well off; her father was a Bank of Vienna director and her mother a concert pianist. Lamarr attended schools in Vienna and was sent to a finishing school in Switzerland as a teenager. By that time she was already unusually beautiful, attracting the attention of both prospective lovers and film producers. After an unsuccessful audition with famed stage director, Max Reinhardt, from whom she had taken acting lessons, Lamarr moved into films. Her screen career began in 1930 with a pair of Austrian films, Money on the Street and Storm in a Waterglass .

She had several other small roles in German-language films, but it took controversy to put Lamarr on the cinematic map. In 1932 she made a film called Extase (or Ecstasy) in Czechoslovakia; it was released the following year. The film told the simple story of a young woman whose husband is impotent, causing her to seek out the companionship of a younger man. Two scenes were responsible for the film's notoriety and quick banning by Austrian censors: one in which Lamarr runs nude through a sunlit forest, the other a sex scene in which she seems to experience orgasm (her intense facial expressions actually resulted from the application of a safety pin to her buttock by director Gustav Machaty). Lamarr later said that she had been a naive young woman pressured into doing these scenes, but cameraman Jan Stallich told Jan Christopher Horak of CineAction that "as the star of the picture, she knew she would have to appear naked in some scenes. She never made any fuss about it during the production."

Controversy and condemnation from Pope Pius XI temporarily halted Lamarr's film career, but Extase did attract the attention of millionaire Austrian arms dealer Fritz Mandl, whom Lamarr met in December of 1933 and then married. Mandl had converted from Judaism to Catholicism in order to be able to do business with Germany's fascist regime (he was nevertheless exiled to Argentina after Austria came under German control in 1938), and Lamarr also made her religious conversion in 1933. An often-repeated story holds that Mandl tried to buy and destroy every outstanding copy of Extase , but this is thought to be legend rather than fact. Whether out of revulsion toward her husband's politics or from sheer restlessness, Lamarr packed a single suitcase with jewelry, drugged her maid, and fled to Paris and then London in 1937. That September she sailed for New York.

On board, she began negotiating with producer Louis B. Mayer of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (M-G-M) studio, who had signed Swedish actress Greta Garbo several years earlier and was on the lookout for exotic European talent. Lamarr had refused Mayer's contract offer in London, but by the time the ship docked in New York she had a $500-a-week contract and the new name of Hedy Lamarr—up to that point she had used Hedi Kiesler. Mayer devised the name, inspired by that of silent film actress Barbara La Marr.

Starred Opposite Charles Boyer

Lamarr's first film in the United States was Algiers (1938), in which she played opposite French actor Charles Boyer as a woman who, though engaged to another man, has an affair with an escaped thief (Boyer). The film was a successful launch for Lamarr's American career, but it was followed by two flops, Lady of the Tropics (1939) and I Take This Woman (1940), the latter co-starring Spencer Tracy and dubbed I Re-Take This Woman after Mayer demanded numerous changes in the script. The actress's fortunes turned around later in 1940 with Boom Town , with Clark Gable in the lead role, and Comrade X , a sort of anti-Communist romance in which Lamarr played a Soviet streetcar driver who falls in love with an American reporter (Clark Gable).

Throughout World War II, Lamarr was a fixture on American movie screens with such films as Come Live with Me (1941), Ziegfeld Girl (1941), and the steamy White Cargo (1943), in which Lamarr played a mixed-race prostitute on an African rubber plantation (although censors demanded that references to her character's ethnicity be removed from the script). With such films as 1943's The Heavenly Body (the title ostensibly referred to astronomy), Lamarr emerged in the first rank of screen sex symbols. A poll of Columbia University male undergraduates ranked Lamarr as the actress they would most like to be marooned with on an island, and in 1942 Lamarr participated in the World War II mobilization effort by offering to kiss any man who would purchase $25,000 in War Bonds. She raised $17 million with 680 kisses. In 1943, Lamarr was rumored to have been in the running for (or to have turned down) the role that eventually went to Swedish actress Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca .

Lamarr had plenty of space in celebrity gossip columns to go with her screen stardom. She dated silent comedian Charlie Chaplin in 1941, and had flings with Burgess Meredith and several other actors. Lamarr married producer Gene Markey in 1939, divorcing him the following year. For four years she was married to English actor John Loder and had two children by him. Later in life Lamarr was married three more times, to bandleader Teddy Stauffer, Texas oil magnate Howard Lee, and lawyer Lewis Boles. All her marriages ended in divorce. Another man with whom Lamarr may have been romantically involved was composer George Antheil.

Antheil played an important role in Lamarr's life in another way as well—as a collaborator on an important electronics innovation. Lamarr was slightly dismissive of her glamorous image, saying (according to her U.S. News & World Report obituary), "Any girl can be glamorous. All you have to do is stand still and look stupid." Lamar, by contrast, had been astute enough to pick up a good deal of practical knowledge pertaining to munitions engineering during her marriage to Mandl. In 1940 she had the idea for a solution to the problem of controlling a radio-guided torpedo. At that time, electronic data broadcast on a specific frequency could easily be jammed by enemy transmitters. Lamarr suggested rapid changes in the broadcast frequency, and Antheil, who had experimented with electronic musical instruments, devised a punch-card-like device, similar to a player-piano roll, that could synchronize a transmitter and receiver. The system Lamarr and Antheil invented relied on using 88 frequencies, equivalent to the number of keys on a piano.

Realized No Money from Invention

The pair were jointly awarded a patent for their discovery, but Antheil later credited the original idea entirely to Lamarr. Credit did not matter, however, for the idea, later given the name of frequency hopping, was never applied by the military during World War II. It was later rediscovered independently and used in ships sent to Cuba during the missile crisis of 1962. The real payoff of frequency hopping came only decades later, when it became integral to the operation of cellular telephones and Bluetooth systems that enabled computers to communicate with peripheral devices. By that time, Lamarr and Antheil's patent had long since expired.

Experiment Perilous (1944), directed by Jacques Tourneur, was considered one of Lamarr's best films, but her career gradually declined after World War II. The most visible outing from this phase of her career was the Cecil B. DeMille-produced Samson and Delilah (1949), with Victor Mature and Lamarr in the title roles. The film, in Horak's words, "marries an Old Testament-style, evangelical Christian moralism with the theatrical exploitation of unadulterated sex." For David Thomson of London's Independent on Sunday , the film had "many moments where [Lamarr's] foreign voice, her basilisk gaze, and her sinful body combine to magnificent effect."

Lamarr made several films in the 1950s, mostly operating outside of the Hollywood system. In the 1954 Italian-made feature The Loves of Three Queens she played Helen of Troy, and she took on another historical role as Joan of Arc in The Story of Mankind (1958). Her heyday was past, however, and she stayed away from Hollywood for much of the time. In 1950 she sold off all of her possessions in an auction and announced that she was moving to Mexico. A marriage brought her back to the United States and to Texas in 1955, and in retirement she moved to Florida. Occasionally she appeared on television. In 1967 she published an autobiography, Ecstasy and Me: My Life as a Woman , but sued the ghostwriters she had employed, claiming (according to Thomson), that the book was "fictional, false, vulgar, scandalous, libelous, and obscene."

That was one of several episodes that saw Lamarr entering courtrooms in her later years. Lamarr was arrested in 1966 for shoplifting at Macy's department store, but was acquitted. She complained to a columnist that she had once had a $7 million income but by the late 1960s was subsisting on a $48-a-week pension. Another round of litigation came after the release of director Mel Brooks's Western film parody Blazing Saddles in 1974; the actress objected to the fanciful "Hedley Lamarr" name of one of the movie's characters.

Lamarr lived mostly in isolation in a small house in Orlando in the last years of her life, reportedly staying out of the spotlight partly because of unsuccessful plastic surgery. She antagonized the organizers of a film festival with unreasonable demands for a makeup retinue. In 1990, however, she had a cameo role in the satire Instant Karma , and she lived long enough to see a modest renewal of interest in the sexually independent persona she had often projected on film. The story of her radio transmission invention also became widely publicized in the 1990s, and she received an Electronic Frontier Foundation Pioneer Award in 1997, although she never received any monetary award for her ingenuity. On January 19, 2000, Hedy Lamarr died at her home in Orlando.

Lamarr, Hedy, Ecstasy and Me: My Life as a Woman , Fawcett, 1967.

World of Invention , 2nd ed., Gale, 1999.

Young, Christopher, The Films of Hedy Lamarr , Citadel, 1978.

Periodicals

CineAction , Spring 2001.

Economist , June 21, 2003.

Entertainment Weekly , February 4, 2000.

Forbes , May 14, 1990.

Independent on Sunday (London, England), January 30, 2005.

People , February 7, 2000.

U.S. News & World Report , January 31, 2000.

"Hedy Lamarr," All Movie Guide , http://www.allmovie.com (January 20, 2007).

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

Famous Scientists

Hedy Lamarr

Beautiful Hedy Lamarr was known mostly for being an elegant actress, being one of the MGM stars during the “Golden Age” and a well-known face during those years. Apart from being a crowd darling, she helped invent spread-spectrum communication techniques using frequency hopping. This technology is still used today, and it was the Austrian actress and inventor who contributed to its pilot development.

Hedy Lamarr was the stage by which she was known. Hedy was born on the 9th of November in 1914 to parents Emil Kiesler and Gertrud or “Trude” Kiesler in Vienna, Austria-Hungary. Her birth name was Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler. She was of Jewish descent, her mother being a Budapest native who originally came from the “Jewish haute bourgeoisie.” Her father, who was born in Lemberg, was a secular Jew.

Early Career in Entertainment

She was 17 when Lamarr first appeared in a film, called “Geld Auf Der Strase” (Money On The Road). Her career in entertainment made a strong presence in the Czechoslovakian and German productions of that time. The German film “Extase” in 1932 brought Hedy to the attention of Hollywood producers. A few years later, she became an MGM contract star.

When Lamarr entered Hollywood, she adopted her stage name and her first Hollywood film, “Algiers” was released in 1938. Lamarr had a successful career in entertainment and was known as “the most beautiful woman in films”. She wrote an autobiography called “Ecstasy and Me” which detailed her private life.

She married her first husband, Friedrich Mandl, a wealthy Austrian in 1933. Lamarr’s autobiography described her husband as an extremely controlling man who prevented her growing her acting career. She stated that she felt imprisoned in their castle-like home where parties were held and where notable people like Hitler and Mussolini attended. Also in her autobiography, she stated that she devised a plan to escape her controlling marriage by disguising herself as her maid and then leaving for Paris, where she subsequently blossomed as an actress. They were divorced in 1937.

Secret Communications System

George Anthiel, an avant-garde composer happened to be Lamarr’s neighbor when she lived in California. The son of German immigrants, he had been experimenting with the automated controls of musical instruments, especially for the music he composed for the Ballet “Mecanique”.

During the Second World War, Lamarr and Antheil discussed how radio-controlled torpedoes that were being used by the navy could be disrupted by broadcasting a particular interference at the signal’s frequency control, which would ultimately lead the torpedo off target.

Together with Anthiel, Lamarr developed the “Secret Communications System”, a patented device which manipulated the radio frequencies at irregular intervals during reception or transmission. Their invention formed a kind of unbreakable code which prevented classified information and message transmissions from being intercepted by the enemy.

Lamarr obtained her knowledge about torpedoes from her first husband, Mandl, and she used her knowledge to help develop this invention. With Anthiel who incorporated the use of a piano roll, they were successfully able to devise frequency hopping. They used the 88 piano keys to randomly change the signals within the range of 88 frequencies.