Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on September 5, 2024.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organizations to understand their cultures. | |

| Action research | Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

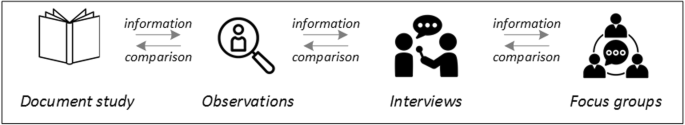

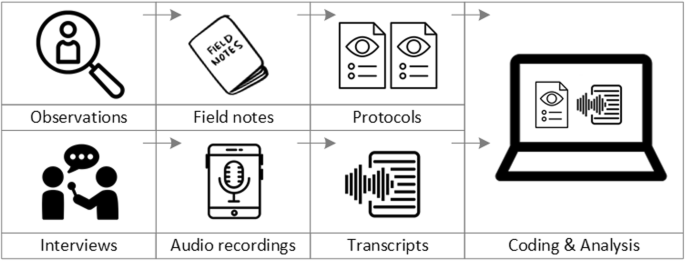

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorize common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

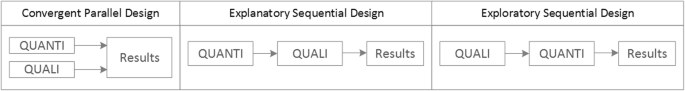

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2024, September 05). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 23, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

- Regular Article

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 679–689, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Drishti Yadav ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2974-0323 1

104k Accesses

49 Citations

70 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review aims to synthesize a published set of evaluative criteria for good qualitative research. The aim is to shed light on existing standards for assessing the rigor of qualitative research encompassing a range of epistemological and ontological standpoints. Using a systematic search strategy, published journal articles that deliberate criteria for rigorous research were identified. Then, references of relevant articles were surveyed to find noteworthy, distinct, and well-defined pointers to good qualitative research. This review presents an investigative assessment of the pivotal features in qualitative research that can permit the readers to pass judgment on its quality and to condemn it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the necessity to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. It also offers some prospects and recommendations to improve the quality of qualitative research. Based on the findings of this review, it is concluded that quality criteria are the aftereffect of socio-institutional procedures and existing paradigmatic conducts. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single and specific set of quality criteria is neither feasible nor anticipated. Since qualitative research is not a cohesive discipline, researchers need to educate and familiarize themselves with applicable norms and decisive factors to evaluate qualitative research from within its theoretical and methodological framework of origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Good Qualitative Research: Opening up the Debate

Beyond qualitative/quantitative structuralism: the positivist qualitative research and the paradigmatic disclaimer.

What is Qualitative in Research

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“… It is important to regularly dialogue about what makes for good qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 , p. 837)

To decide what represents good qualitative research is highly debatable. There are numerous methods that are contained within qualitative research and that are established on diverse philosophical perspectives. Bryman et al., ( 2008 , p. 262) suggest that “It is widely assumed that whereas quality criteria for quantitative research are well‐known and widely agreed, this is not the case for qualitative research.” Hence, the question “how to evaluate the quality of qualitative research” has been continuously debated. There are many areas of science and technology wherein these debates on the assessment of qualitative research have taken place. Examples include various areas of psychology: general psychology (Madill et al., 2000 ); counseling psychology (Morrow, 2005 ); and clinical psychology (Barker & Pistrang, 2005 ), and other disciplines of social sciences: social policy (Bryman et al., 2008 ); health research (Sparkes, 2001 ); business and management research (Johnson et al., 2006 ); information systems (Klein & Myers, 1999 ); and environmental studies (Reid & Gough, 2000 ). In the literature, these debates are enthused by the impression that the blanket application of criteria for good qualitative research developed around the positivist paradigm is improper. Such debates are based on the wide range of philosophical backgrounds within which qualitative research is conducted (e.g., Sandberg, 2000 ; Schwandt, 1996 ). The existence of methodological diversity led to the formulation of different sets of criteria applicable to qualitative research.

Among qualitative researchers, the dilemma of governing the measures to assess the quality of research is not a new phenomenon, especially when the virtuous triad of objectivity, reliability, and validity (Spencer et al., 2004 ) are not adequate. Occasionally, the criteria of quantitative research are used to evaluate qualitative research (Cohen & Crabtree, 2008 ; Lather, 2004 ). Indeed, Howe ( 2004 ) claims that the prevailing paradigm in educational research is scientifically based experimental research. Hypotheses and conjectures about the preeminence of quantitative research can weaken the worth and usefulness of qualitative research by neglecting the prominence of harmonizing match for purpose on research paradigm, the epistemological stance of the researcher, and the choice of methodology. Researchers have been reprimanded concerning this in “paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences” (Lincoln & Guba, 2000 ).

In general, qualitative research tends to come from a very different paradigmatic stance and intrinsically demands distinctive and out-of-the-ordinary criteria for evaluating good research and varieties of research contributions that can be made. This review attempts to present a series of evaluative criteria for qualitative researchers, arguing that their choice of criteria needs to be compatible with the unique nature of the research in question (its methodology, aims, and assumptions). This review aims to assist researchers in identifying some of the indispensable features or markers of high-quality qualitative research. In a nutshell, the purpose of this systematic literature review is to analyze the existing knowledge on high-quality qualitative research and to verify the existence of research studies dealing with the critical assessment of qualitative research based on the concept of diverse paradigmatic stances. Contrary to the existing reviews, this review also suggests some critical directions to follow to improve the quality of qualitative research in different epistemological and ontological perspectives. This review is also intended to provide guidelines for the acceleration of future developments and dialogues among qualitative researchers in the context of assessing the qualitative research.

The rest of this review article is structured in the following fashion: Sect. Methods describes the method followed for performing this review. Section Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies provides a comprehensive description of the criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. This section is followed by a summary of the strategies to improve the quality of qualitative research in Sect. Improving Quality: Strategies . Section How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings? provides details on how to assess the quality of the research findings. After that, some of the quality checklists (as tools to evaluate quality) are discussed in Sect. Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality . At last, the review ends with the concluding remarks presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook . Some prospects in qualitative research for enhancing its quality and usefulness in the social and techno-scientific research community are also presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook .

For this review, a comprehensive literature search was performed from many databases using generic search terms such as Qualitative Research , Criteria , etc . The following databases were chosen for the literature search based on the high number of results: IEEE Explore, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The following keywords (and their combinations using Boolean connectives OR/AND) were adopted for the literature search: qualitative research, criteria, quality, assessment, and validity. The synonyms for these keywords were collected and arranged in a logical structure (see Table 1 ). All publications in journals and conference proceedings later than 1950 till 2021 were considered for the search. Other articles extracted from the references of the papers identified in the electronic search were also included. A large number of publications on qualitative research were retrieved during the initial screening. Hence, to include the searches with the main focus on criteria for good qualitative research, an inclusion criterion was utilized in the search string.

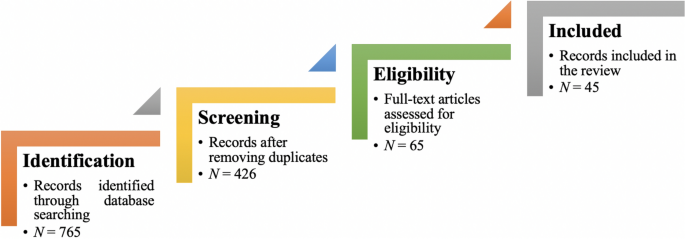

From the selected databases, the search retrieved a total of 765 publications. Then, the duplicate records were removed. After that, based on the title and abstract, the remaining 426 publications were screened for their relevance by using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 2 ). Publications focusing on evaluation criteria for good qualitative research were included, whereas those works which delivered theoretical concepts on qualitative research were excluded. Based on the screening and eligibility, 45 research articles were identified that offered explicit criteria for evaluating the quality of qualitative research and were found to be relevant to this review.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete review process in the form of PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, i.e., “preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” is employed in systematic reviews to refine the quality of reporting.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the search and inclusion process. N represents the number of records

Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies

Fundamental criteria: general research quality.

Various researchers have put forward criteria for evaluating qualitative research, which have been summarized in Table 3 . Also, the criteria outlined in Table 4 effectively deliver the various approaches to evaluate and assess the quality of qualitative work. The entries in Table 4 are based on Tracy’s “Eight big‐tent criteria for excellent qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 ). Tracy argues that high-quality qualitative work should formulate criteria focusing on the worthiness, relevance, timeliness, significance, morality, and practicality of the research topic, and the ethical stance of the research itself. Researchers have also suggested a series of questions as guiding principles to assess the quality of a qualitative study (Mays & Pope, 2020 ). Nassaji ( 2020 ) argues that good qualitative research should be robust, well informed, and thoroughly documented.

Qualitative Research: Interpretive Paradigms

All qualitative researchers follow highly abstract principles which bring together beliefs about ontology, epistemology, and methodology. These beliefs govern how the researcher perceives and acts. The net, which encompasses the researcher’s epistemological, ontological, and methodological premises, is referred to as a paradigm, or an interpretive structure, a “Basic set of beliefs that guides action” (Guba, 1990 ). Four major interpretive paradigms structure the qualitative research: positivist and postpositivist, constructivist interpretive, critical (Marxist, emancipatory), and feminist poststructural. The complexity of these four abstract paradigms increases at the level of concrete, specific interpretive communities. Table 5 presents these paradigms and their assumptions, including their criteria for evaluating research, and the typical form that an interpretive or theoretical statement assumes in each paradigm. Moreover, for evaluating qualitative research, quantitative conceptualizations of reliability and validity are proven to be incompatible (Horsburgh, 2003 ). In addition, a series of questions have been put forward in the literature to assist a reviewer (who is proficient in qualitative methods) for meticulous assessment and endorsement of qualitative research (Morse, 2003 ). Hammersley ( 2007 ) also suggests that guiding principles for qualitative research are advantageous, but methodological pluralism should not be simply acknowledged for all qualitative approaches. Seale ( 1999 ) also points out the significance of methodological cognizance in research studies.

Table 5 reflects that criteria for assessing the quality of qualitative research are the aftermath of socio-institutional practices and existing paradigmatic standpoints. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single set of quality criteria is neither possible nor desirable. Hence, the researchers must be reflexive about the criteria they use in the various roles they play within their research community.

Improving Quality: Strategies

Another critical question is “How can the qualitative researchers ensure that the abovementioned quality criteria can be met?” Lincoln and Guba ( 1986 ) delineated several strategies to intensify each criteria of trustworthiness. Other researchers (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016 ; Shenton, 2004 ) also presented such strategies. A brief description of these strategies is shown in Table 6 .

It is worth mentioning that generalizability is also an integral part of qualitative research (Hays & McKibben, 2021 ). In general, the guiding principle pertaining to generalizability speaks about inducing and comprehending knowledge to synthesize interpretive components of an underlying context. Table 7 summarizes the main metasynthesis steps required to ascertain generalizability in qualitative research.

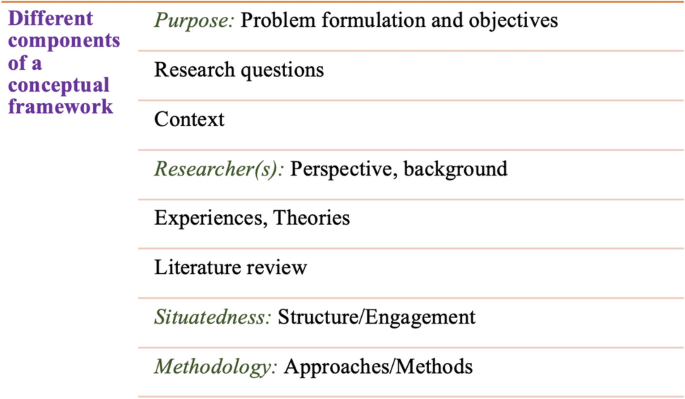

Figure 2 reflects the crucial components of a conceptual framework and their contribution to decisions regarding research design, implementation, and applications of results to future thinking, study, and practice (Johnson et al., 2020 ). The synergy and interrelationship of these components signifies their role to different stances of a qualitative research study.

Essential elements of a conceptual framework

In a nutshell, to assess the rationale of a study, its conceptual framework and research question(s), quality criteria must take account of the following: lucid context for the problem statement in the introduction; well-articulated research problems and questions; precise conceptual framework; distinct research purpose; and clear presentation and investigation of the paradigms. These criteria would expedite the quality of qualitative research.

How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings?

The inclusion of quotes or similar research data enhances the confirmability in the write-up of the findings. The use of expressions (for instance, “80% of all respondents agreed that” or “only one of the interviewees mentioned that”) may also quantify qualitative findings (Stenfors et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, the persuasive reason for “why this may not help in intensifying the research” has also been provided (Monrouxe & Rees, 2020 ). Further, the Discussion and Conclusion sections of an article also prove robust markers of high-quality qualitative research, as elucidated in Table 8 .

Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality

Numerous checklists are available to speed up the assessment of the quality of qualitative research. However, if used uncritically and recklessly concerning the research context, these checklists may be counterproductive. I recommend that such lists and guiding principles may assist in pinpointing the markers of high-quality qualitative research. However, considering enormous variations in the authors’ theoretical and philosophical contexts, I would emphasize that high dependability on such checklists may say little about whether the findings can be applied in your setting. A combination of such checklists might be appropriate for novice researchers. Some of these checklists are listed below:

The most commonly used framework is Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007 ). This framework is recommended by some journals to be followed by the authors during article submission.

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is another checklist that has been created particularly for medical education (O’Brien et al., 2014 ).

Also, Tracy ( 2010 ) and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2021 ) offer criteria for qualitative research relevant across methods and approaches.

Further, researchers have also outlined different criteria as hallmarks of high-quality qualitative research. For instance, the “Road Trip Checklist” (Epp & Otnes, 2021 ) provides a quick reference to specific questions to address different elements of high-quality qualitative research.

Conclusions, Future Directions, and Outlook

This work presents a broad review of the criteria for good qualitative research. In addition, this article presents an exploratory analysis of the essential elements in qualitative research that can enable the readers of qualitative work to judge it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. In this review, some of the essential markers that indicate high-quality qualitative research have been highlighted. I scope them narrowly to achieve rigor in qualitative research and note that they do not completely cover the broader considerations necessary for high-quality research. This review points out that a universal and versatile one-size-fits-all guideline for evaluating the quality of qualitative research does not exist. In other words, this review also emphasizes the non-existence of a set of common guidelines among qualitative researchers. In unison, this review reinforces that each qualitative approach should be treated uniquely on account of its own distinctive features for different epistemological and disciplinary positions. Owing to the sensitivity of the worth of qualitative research towards the specific context and the type of paradigmatic stance, researchers should themselves analyze what approaches can be and must be tailored to ensemble the distinct characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation. Although this article does not assert to put forward a magic bullet and to provide a one-stop solution for dealing with dilemmas about how, why, or whether to evaluate the “goodness” of qualitative research, it offers a platform to assist the researchers in improving their qualitative studies. This work provides an assembly of concerns to reflect on, a series of questions to ask, and multiple sets of criteria to look at, when attempting to determine the quality of qualitative research. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the need to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. Bringing together the vital arguments and delineating the requirements that good qualitative research should satisfy, this review strives to equip the researchers as well as reviewers to make well-versed judgment about the worth and significance of the qualitative research under scrutiny. In a nutshell, a comprehensive portrayal of the research process (from the context of research to the research objectives, research questions and design, speculative foundations, and from approaches of collecting data to analyzing the results, to deriving inferences) frequently proliferates the quality of a qualitative research.

Prospects : A Road Ahead for Qualitative Research

Irrefutably, qualitative research is a vivacious and evolving discipline wherein different epistemological and disciplinary positions have their own characteristics and importance. In addition, not surprisingly, owing to the sprouting and varied features of qualitative research, no consensus has been pulled off till date. Researchers have reflected various concerns and proposed several recommendations for editors and reviewers on conducting reviews of critical qualitative research (Levitt et al., 2021 ; McGinley et al., 2021 ). Following are some prospects and a few recommendations put forward towards the maturation of qualitative research and its quality evaluation:

In general, most of the manuscript and grant reviewers are not qualitative experts. Hence, it is more likely that they would prefer to adopt a broad set of criteria. However, researchers and reviewers need to keep in mind that it is inappropriate to utilize the same approaches and conducts among all qualitative research. Therefore, future work needs to focus on educating researchers and reviewers about the criteria to evaluate qualitative research from within the suitable theoretical and methodological context.

There is an urgent need to refurbish and augment critical assessment of some well-known and widely accepted tools (including checklists such as COREQ, SRQR) to interrogate their applicability on different aspects (along with their epistemological ramifications).

Efforts should be made towards creating more space for creativity, experimentation, and a dialogue between the diverse traditions of qualitative research. This would potentially help to avoid the enforcement of one's own set of quality criteria on the work carried out by others.

Moreover, journal reviewers need to be aware of various methodological practices and philosophical debates.

It is pivotal to highlight the expressions and considerations of qualitative researchers and bring them into a more open and transparent dialogue about assessing qualitative research in techno-scientific, academic, sociocultural, and political rooms.

Frequent debates on the use of evaluative criteria are required to solve some potentially resolved issues (including the applicability of a single set of criteria in multi-disciplinary aspects). Such debates would not only benefit the group of qualitative researchers themselves, but primarily assist in augmenting the well-being and vivacity of the entire discipline.

To conclude, I speculate that the criteria, and my perspective, may transfer to other methods, approaches, and contexts. I hope that they spark dialog and debate – about criteria for excellent qualitative research and the underpinnings of the discipline more broadly – and, therefore, help improve the quality of a qualitative study. Further, I anticipate that this review will assist the researchers to contemplate on the quality of their own research, to substantiate research design and help the reviewers to review qualitative research for journals. On a final note, I pinpoint the need to formulate a framework (encompassing the prerequisites of a qualitative study) by the cohesive efforts of qualitative researchers of different disciplines with different theoretic-paradigmatic origins. I believe that tailoring such a framework (of guiding principles) paves the way for qualitative researchers to consolidate the status of qualitative research in the wide-ranging open science debate. Dialogue on this issue across different approaches is crucial for the impending prospects of socio-techno-educational research.

Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16 (10), 1472–1482.

Article Google Scholar

Barker, C., & Pistrang, N. (2005). Quality criteria under methodological pluralism: Implications for conducting and evaluating research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (3–4), 201–212.

Bryman, A., Becker, S., & Sempik, J. (2008). Quality criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research: A view from social policy. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11 (4), 261–276.

Caelli, K., Ray, L., & Mill, J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2 (2), 1–13.

CASP (2021). CASP checklists. Retrieved May 2021 from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Cohen, D. J., & Crabtree, B. F. (2008). Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: Controversies and recommendations. The Annals of Family Medicine, 6 (4), 331–339.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Sage Publications Ltd.

Google Scholar

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38 (3), 215–229.

Epp, A. M., & Otnes, C. C. (2021). High-quality qualitative research: Getting into gear. Journal of Service Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520961445

Guba, E. G. (1990). The paradigm dialog. In Alternative paradigms conference, mar, 1989, Indiana u, school of education, San Francisco, ca, us . Sage Publications, Inc.

Hammersley, M. (2007). The issue of quality in qualitative research. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 30 (3), 287–305.

Haven, T. L., Errington, T. M., Gleditsch, K. S., van Grootel, L., Jacobs, A. M., Kern, F. G., & Mokkink, L. B. (2020). Preregistering qualitative research: A Delphi study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406920976417.

Hays, D. G., & McKibben, W. B. (2021). Promoting rigorous research: Generalizability and qualitative research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 99 (2), 178–188.

Horsburgh, D. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12 (2), 307–312.

Howe, K. R. (2004). A critique of experimentalism. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 42–46.

Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84 (1), 7120.

Johnson, P., Buehring, A., Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (2006). Evaluating qualitative management research: Towards a contingent criteriology. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8 (3), 131–156.

Klein, H. K., & Myers, M. D. (1999). A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 23 (1), 67–93.

Lather, P. (2004). This is your father’s paradigm: Government intrusion and the case of qualitative research in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 15–34.

Levitt, H. M., Morrill, Z., Collins, K. M., & Rizo, J. L. (2021). The methodological integrity of critical qualitative research: Principles to support design and research review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68 (3), 357.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986 (30), 73–84.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 163–188). Sage Publications.

Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91 (1), 1–20.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2020). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Health Care . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119410867.ch15

McGinley, S., Wei, W., Zhang, L., & Zheng, Y. (2021). The state of qualitative research in hospitality: A 5-year review 2014 to 2019. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62 (1), 8–20.

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, US.

Meyer, M., & Dykes, J. (2019). Criteria for rigor in visualization design study. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 26 (1), 87–97.

Monrouxe, L. V., & Rees, C. E. (2020). When I say… quantification in qualitative research. Medical Education, 54 (3), 186–187.

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52 (2), 250.

Morse, J. M. (2003). A review committee’s guide for evaluating qualitative proposals. Qualitative Health Research, 13 (6), 833–851.

Nassaji, H. (2020). Good qualitative research. Language Teaching Research, 24 (4), 427–431.

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406919899220.

Reid, A., & Gough, S. (2000). Guidelines for reporting and evaluating qualitative research: What are the alternatives? Environmental Education Research, 6 (1), 59–91.

Rocco, T. S. (2010). Criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. Human Resource Development International . https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2010.501959

Sandberg, J. (2000). Understanding human competence at work: An interpretative approach. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (1), 9–25.

Schwandt, T. A. (1996). Farewell to criteriology. Qualitative Inquiry, 2 (1), 58–72.

Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 5 (4), 465–478.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 (2), 63–75.

Sparkes, A. C. (2001). Myth 94: Qualitative health researchers will agree about validity. Qualitative Health Research, 11 (4), 538–552.

Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2004). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence.

Stenfors, T., Kajamaa, A., & Bennett, D. (2020). How to assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher, 17 (6), 596–599.

Taylor, E. W., Beck, J., & Ainsworth, E. (2001). Publishing qualitative adult education research: A peer review perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 33 (2), 163–179.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19 (6), 349–357.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16 (10), 837–851.

Download references

Open access funding provided by TU Wien (TUW).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Informatics, Technische Universität Wien, 1040, Vienna, Austria

Drishti Yadav

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Drishti Yadav .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Yadav, D. Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 31 , 679–689 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Download citation

Accepted : 28 August 2021

Published : 18 September 2021

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Evaluative criteria

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Qualitative Research Methods: A Practice-Oriented Introduction

- February 2023

- University of Hamburg

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

Supplementary resource (1)

- Simanga Phillip Lukhele

- LDM Lebeloane

- Nonzukiso Tyilo

- Thobeka Matshoba

- Kingsley Afful

- Int J Econ Bus Res

- Muhammad Yusry Affandy bin Md Isa

- Muhammad Syahmi bin Shakhruddin

- Maryuni Maryuni

- Sabarinah Prasetyo

- Arinza Justistio

- Amiruddin Amiruddin

- Junaidah Junaidah

- SCI JUSTICE

- Carlos Miguel Ibaviosa

- Firas Khatib

- Leon Festinger

- Kenneth L. Pike

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

18 Qualitative Research Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Qualitative research is an approach to scientific research that involves using observation to gather and analyze non-numerical, in-depth, and well-contextualized datasets.

It serves as an integral part of academic, professional, and even daily decision-making processes (Baxter & Jack, 2008).

Methods of qualitative research encompass a wide range of techniques, from in-depth personal encounters, like ethnographies (studying cultures in-depth) and autoethnographies (examining one’s own cultural experiences), to collection of diverse perspectives on topics through methods like interviewing focus groups (gatherings of individuals to discuss specific topics).

Qualitative Research Examples

1. ethnography.

Definition: Ethnography is a qualitative research design aimed at exploring cultural phenomena. Rooted in the discipline of anthropology , this research approach investigates the social interactions, behaviors, and perceptions within groups, communities, or organizations.

Ethnographic research is characterized by extended observation of the group, often through direct participation, in the participants’ environment. An ethnographer typically lives with the study group for extended periods, intricately observing their everyday lives (Khan, 2014).

It aims to present a complete, detailed and accurate picture of the observed social life, rituals, symbols, and values from the perspective of the study group.

| The key advantage of ethnography is its depth; it provides an in-depth understanding of the group’s behaviour, lifestyle, culture, and context. It also allows for flexibility, as researchers can adapt their approach based on their observations (Bryman, 2015) | There are issues regarding the subjective interpretation of data, and it’s time-consuming. It also requires the researchers to immerse themselves in the study environment, which might not always be feasible. |

Example of Ethnographic Research

Title: “ The Everyday Lives of Men: An Ethnographic Investigation of Young Adult Male Identity “

Citation: Evans, J. (2010). The Everyday Lives of Men: An Ethnographic Investigation of Young Adult Male Identity. Peter Lang.

Overview: This study by Evans (2010) provides a rich narrative of young adult male identity as experienced in everyday life. The author immersed himself among a group of young men, participating in their activities and cultivating a deep understanding of their lifestyle, values, and motivations. This research exemplified the ethnographic approach, revealing complexities of the subjects’ identities and societal roles, which could hardly be accessed through other qualitative research designs.

Read my Full Guide on Ethnography Here

2. Autoethnography

Definition: Autoethnography is an approach to qualitative research where the researcher uses their own personal experiences to extend the understanding of a certain group, culture, or setting. Essentially, it allows for the exploration of self within the context of social phenomena.

Unlike traditional ethnography, which focuses on the study of others, autoethnography turns the ethnographic gaze inward, allowing the researcher to use their personal experiences within a culture as rich qualitative data (Durham, 2019).

The objective is to critically appraise one’s personal experiences as they navigate and negotiate cultural, political, and social meanings. The researcher becomes both the observer and the participant, intertwining personal and cultural experiences in the research.

| One of the chief benefits of autoethnography is its ability to bridge the gap between researchers and audiences by using relatable experiences. It can also provide unique and profound insights unaccessible through traditional ethnographic approaches (Heinonen, 2012). | The subjective nature of this method can introduce bias. Critics also argue that the singular focus on personal experience may limit the contributions to broader cultural or social understanding. |

Example of Autoethnographic Research

Title: “ A Day In The Life Of An NHS Nurse “

Citation: Osben, J. (2019). A day in the life of a NHS nurse in 21st Century Britain: An auto-ethnography. The Journal of Autoethnography for Health & Social Care. 1(1).

Overview: This study presents an autoethnography of a day in the life of an NHS nurse (who, of course, is also the researcher). The author uses the research to achieve reflexivity, with the researcher concluding: “Scrutinising my practice and situating it within a wider contextual backdrop has compelled me to significantly increase my level of scrutiny into the driving forces that influence my practice.”

Read my Full Guide on Autoethnography Here

3. Semi-Structured Interviews

Definition: Semi-structured interviews stand as one of the most frequently used methods in qualitative research. These interviews are planned and utilize a set of pre-established questions, but also allow for the interviewer to steer the conversation in other directions based on the responses given by the interviewee.

In semi-structured interviews, the interviewer prepares a guide that outlines the focal points of the discussion. However, the interview is flexible, allowing for more in-depth probing if the interviewer deems it necessary (Qu, & Dumay, 2011). This style of interviewing strikes a balance between structured ones which might limit the discussion, and unstructured ones, which could lack focus.

| The main advantage of semi-structured interviews is their flexibility, allowing for exploration of unexpected topics that arise during the interview. It also facilitates the collection of robust, detailed data from participants’ perspectives (Smith, 2015). | Potential downsides include the possibility of data overload, periodic difficulties in analysis due to varied responses, and the fact they are time-consuming to conduct and analyze. |

Example of Semi-Structured Interview Research

Title: “ Factors influencing adherence to cancer treatment in older adults with cancer: a systematic review “

Citation: Puts, M., et al. (2014). Factors influencing adherence to cancer treatment in older adults with cancer: a systematic review. Annals of oncology, 25 (3), 564-577.

Overview: Puts et al. (2014) executed an extensive systematic review in which they conducted semi-structured interviews with older adults suffering from cancer to examine the factors influencing their adherence to cancer treatment. The findings suggested that various factors, including side effects, faith in healthcare professionals, and social support have substantial impacts on treatment adherence. This research demonstrates how semi-structured interviews can provide rich and profound insights into the subjective experiences of patients.

4. Focus Groups

Definition: Focus groups are a qualitative research method that involves organized discussion with a selected group of individuals to gain their perspectives on a specific concept, product, or phenomenon. Typically, these discussions are guided by a moderator.

During a focus group session, the moderator has a list of questions or topics to discuss, and participants are encouraged to interact with each other (Morgan, 2010). This interactivity can stimulate more information and provide a broader understanding of the issue under scrutiny. The open format allows participants to ask questions and respond freely, offering invaluable insights into attitudes, experiences, and group norms.

| One of the key advantages of focus groups is their ability to deliver a rich understanding of participants’ experiences and beliefs. They can be particularly beneficial in providing a diverse range of perspectives and opening up new areas for exploration (Doody, Slevin, & Taggart, 2013). | Potential disadvantages include possible domination by a single participant, groupthink, or issues with confidentiality. Additionally, the results are not easily generalizable to a larger population due to the small sample size. |

Example of Focus Group Research

Title: “ Perspectives of Older Adults on Aging Well: A Focus Group Study “

Citation: Halaweh, H., Dahlin-Ivanoff, S., Svantesson, U., & Willén, C. (2018). Perspectives of older adults on aging well: a focus group study. Journal of aging research .

Overview: This study aimed to explore what older adults (aged 60 years and older) perceived to be ‘aging well’. The researchers identified three major themes from their focus group interviews: a sense of well-being, having good physical health, and preserving good mental health. The findings highlight the importance of factors such as positive emotions, social engagement, physical activity, healthy eating habits, and maintaining independence in promoting aging well among older adults.

5. Phenomenology

Definition: Phenomenology, a qualitative research method, involves the examination of lived experiences to gain an in-depth understanding of the essence or underlying meanings of a phenomenon.

The focus of phenomenology lies in meticulously describing participants’ conscious experiences related to the chosen phenomenon (Padilla-Díaz, 2015).

In a phenomenological study, the researcher collects detailed, first-hand perspectives of the participants, typically via in-depth interviews, and then uses various strategies to interpret and structure these experiences, ultimately revealing essential themes (Creswell, 2013). This approach focuses on the perspective of individuals experiencing the phenomenon, seeking to explore, clarify, and understand the meanings they attach to those experiences.

| An advantage of phenomenology is its potential to reveal rich, complex, and detailed understandings of human experiences in a way other research methods cannot. It encourages explorations of deep, often abstract or intangible aspects of human experiences (Bevan, 2014). | Phenomenology might be criticized for its subjectivity, the intense effort required during data collection and analysis, and difficulties in replicating the study. |

Example of Phenomenology Research

Title: “ A phenomenological approach to experiences with technology: current state, promise, and future directions for research ”

Citation: Cilesiz, S. (2011). A phenomenological approach to experiences with technology: Current state, promise, and future directions for research. Educational Technology Research and Development, 59 , 487-510.

Overview: A phenomenological approach to experiences with technology by Sebnem Cilesiz represents a good starting point for formulating a phenomenological study. With its focus on the ‘essence of experience’, this piece presents methodological, reliability, validity, and data analysis techniques that phenomenologists use to explain how people experience technology in their everyday lives.

6. Grounded Theory

Definition: Grounded theory is a systematic methodology in qualitative research that typically applies inductive reasoning . The primary aim is to develop a theoretical explanation or framework for a process, action, or interaction grounded in, and arising from, empirical data (Birks & Mills, 2015).

In grounded theory, data collection and analysis work together in a recursive process. The researcher collects data, analyses it, and then collects more data based on the evolving understanding of the research context. This ongoing process continues until a comprehensive theory that represents the data and the associated phenomenon emerges – a point known as theoretical saturation (Charmaz, 2014).

| An advantage of grounded theory is its ability to generate a theory that is closely related to the reality of the persons involved. It permits flexibility and can facilitate a deep understanding of complex processes in their natural contexts (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). | Critics note that it can be a lengthy and complicated process; others critique the emphasis on theory development over descriptive detail. |

Example of Grounded Theory Research

Title: “ Student Engagement in High School Classrooms from the Perspective of Flow Theory “

Citation: Shernoff, D. J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Shneider, B., & Shernoff, E. S. (2003). Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. School Psychology Quarterly, 18 (2), 158–176.

Overview: Shernoff and colleagues (2003) used grounded theory to explore student engagement in high school classrooms. The researchers collected data through student self-reports, interviews, and observations. Key findings revealed that academic challenge, student autonomy, and teacher support emerged as the most significant factors influencing students’ engagement, demonstrating how grounded theory can illuminate complex dynamics within real-world contexts.

7. Narrative Research

Definition: Narrative research is a qualitative research method dedicated to storytelling and understanding how individuals experience the world. It focuses on studying an individual’s life and experiences as narrated by that individual (Polkinghorne, 2013).

In narrative research, the researcher collects data through methods such as interviews, observations , and document analysis. The emphasis is on the stories told by participants – narratives that reflect their experiences, thoughts, and feelings.

These stories are then interpreted by the researcher, who attempts to understand the meaning the participant attributes to these experiences (Josselson, 2011).

| The strength of narrative research is its ability to provide a deep, holistic, and rich understanding of an individual’s experiences over time. It is well-suited to capturing the complexities and intricacies of human lives and their contexts (Leiblich, Tuval-Mashiach, & Zilber, 2008). | Narrative research may be criticized for its highly interpretive nature, the potential challenges of ensuring reliability and validity, and the complexity of narrative analysis. |

Example of Narrative Research

Title: “Narrative Structures and the Language of the Self”

Citation: McAdams, D. P., Josselson, R., & Lieblich, A. (2006). Identity and story: Creating self in narrative . American Psychological Association.

Overview: In this innovative study, McAdams et al. (2006) employed narrative research to explore how individuals construct their identities through the stories they tell about themselves. By examining personal narratives, the researchers discerned patterns associated with characters, motivations, conflicts, and resolutions, contributing valuable insights about the relationship between narrative and individual identity.

8. Case Study Research

Definition: Case study research is a qualitative research method that involves an in-depth investigation of a single instance or event: a case. These ‘cases’ can range from individuals, groups, or entities to specific projects, programs, or strategies (Creswell, 2013).

The case study method typically uses multiple sources of information for comprehensive contextual analysis. It aims to explore and understand the complexity and uniqueness of a particular case in a real-world context (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). This investigation could result in a detailed description of the case, a process for its development, or an exploration of a related issue or problem.

| Case study research is ideal for a holistic, in-depth investigation, making complex phenomena understandable and allowing for the exploration of contexts and activities where it is not feasible to use other research methods (Crowe et al., 2011). | Critics of case study research often cite concerns about the representativeness of a single case, the limited ability to generalize findings, and potential bias in data collection and interpretation. |

Example of Case Study Research

Title: “ Teacher’s Role in Fostering Preschoolers’ Computational Thinking: An Exploratory Case Study “

Citation: Wang, X. C., Choi, Y., Benson, K., Eggleston, C., & Weber, D. (2021). Teacher’s role in fostering preschoolers’ computational thinking: An exploratory case study. Early Education and Development , 32 (1), 26-48.

Overview: This study investigates the role of teachers in promoting computational thinking skills in preschoolers. The study utilized a qualitative case study methodology to examine the computational thinking scaffolding strategies employed by a teacher interacting with three preschoolers in a small group setting. The findings highlight the importance of teachers’ guidance in fostering computational thinking practices such as problem reformulation/decomposition, systematic testing, and debugging.

Read about some Famous Case Studies in Psychology Here

9. Participant Observation

Definition: Participant observation has the researcher immerse themselves in a group or community setting to observe the behavior of its members. It is similar to ethnography, but generally, the researcher isn’t embedded for a long period of time.

The researcher, being a participant, engages in daily activities, interactions, and events as a way of conducting a detailed study of a particular social phenomenon (Kawulich, 2005).

The method involves long-term engagement in the field, maintaining detailed records of observed events, informal interviews, direct participation, and reflexivity. This approach allows for a holistic view of the participants’ lived experiences, behaviours, and interactions within their everyday environment (Dewalt, 2011).

| A key strength of participant observation is its capacity to offer intimate, nuanced insights into social realities and practices directly from the field. It allows for broader context understanding, emotional insights, and a constant iterative process (Mulhall, 2003). | The method may present challenges including potential observer bias, the difficulty in ensuring ethical standards, and the risk of ‘going native’, where the boundary between being a participant and researcher blurs. |

Example of Participant Observation Research

Title: Conflict in the boardroom: a participant observation study of supervisory board dynamics

Citation: Heemskerk, E. M., Heemskerk, K., & Wats, M. M. (2017). Conflict in the boardroom: a participant observation study of supervisory board dynamics. Journal of Management & Governance , 21 , 233-263.

Overview: This study examined how conflicts within corporate boards affect their performance. The researchers used a participant observation method, where they actively engaged with 11 supervisory boards and observed their dynamics. They found that having a shared understanding of the board’s role called a common framework, improved performance by reducing relationship conflicts, encouraging task conflicts, and minimizing conflicts between the board and CEO.

10. Non-Participant Observation

Definition: Non-participant observation is a qualitative research method in which the researcher observes the phenomena of interest without actively participating in the situation, setting, or community being studied.

This method allows the researcher to maintain a position of distance, as they are solely an observer and not a participant in the activities being observed (Kawulich, 2005).

During non-participant observation, the researcher typically records field notes on the actions, interactions, and behaviors observed , focusing on specific aspects of the situation deemed relevant to the research question.

This could include verbal and nonverbal communication , activities, interactions, and environmental contexts (Angrosino, 2007). They could also use video or audio recordings or other methods to collect data.

| Non-participant observation can increase distance from the participants and decrease researcher bias, as the observer does not become involved in the community or situation under study (Jorgensen, 2015). This method allows for a more detached and impartial view of practices, behaviors, and interactions. | Criticisms of this method include potential observer effects, where individuals may change their behavior if they know they are being observed, and limited contextual understanding, as observers do not participate in the setting’s activities. |

Example of Non-Participant Observation Research

Title: Mental Health Nurses’ attitudes towards mental illness and recovery-oriented practice in acute inpatient psychiatric units: A non-participant observation study

Citation: Sreeram, A., Cross, W. M., & Townsin, L. (2023). Mental Health Nurses’ attitudes towards mental illness and recovery‐oriented practice in acute inpatient psychiatric units: A non‐participant observation study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing .

Overview: This study investigated the attitudes of mental health nurses towards mental illness and recovery-oriented practice in acute inpatient psychiatric units. The researchers used a non-participant observation method, meaning they observed the nurses without directly participating in their activities. The findings shed light on the nurses’ perspectives and behaviors, providing valuable insights into their attitudes toward mental health and recovery-focused care in these settings.

11. Content Analysis

Definition: Content Analysis involves scrutinizing textual, visual, or spoken content to categorize and quantify information. The goal is to identify patterns, themes, biases, or other characteristics (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

Content Analysis is widely used in various disciplines for a multitude of purposes. Researchers typically use this method to distill large amounts of unstructured data, like interview transcripts, newspaper articles, or social media posts, into manageable and meaningful chunks.

When wielded appropriately, Content Analysis can illuminate the density and frequency of certain themes within a dataset, provide insights into how specific terms or concepts are applied contextually, and offer inferences about the meanings of their content and use (Duriau, Reger, & Pfarrer, 2007).

| The application of Content Analysis offers several strengths, chief among them being the ability to gain an in-depth, contextualized, understanding of a range of texts – both written and multimodal (Gray, Grove, & Sutherland, 2017) – see also: . | Content analysis is dependent on the descriptors that the researcher selects to examine the data, potentially leading to bias. Moreover, this method may also lose sight of the wider social context, which can limit the depth of the analysis (Krippendorff, 2013). |

Example of Content Analysis

Title: Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news .

Citation: Semetko, H. A., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2000). Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news. Journal of Communication, 50 (2), 93-109.

Overview: This study analyzed press and television news articles about European politics using a method called content analysis. The researchers examined the prevalence of different “frames” in the news, which are ways of presenting information to shape audience perceptions. They found that the most common frames were attribution of responsibility, conflict, economic consequences, human interest, and morality.

Read my Full Guide on Content Analysis Here

12. Discourse Analysis

Definition: Discourse Analysis, a qualitative research method, interprets the meanings, functions, and coherence of certain languages in context.

Discourse analysis is typically understood through social constructionism, critical theory , and poststructuralism and used for understanding how language constructs social concepts (Cheek, 2004).

Discourse Analysis offers great breadth, providing tools to examine spoken or written language, often beyond the level of the sentence. It enables researchers to scrutinize how text and talk articulate social and political interactions and hierarchies.

Insight can be garnered from different conversations, institutional text, and media coverage to understand how topics are addressed or framed within a specific social context (Jorgensen & Phillips, 2002).

| Discourse Analysis presents as its strength the ability to explore the intricate relationship between language and society. It goes beyond mere interpretation of content and scrutinizes the power dynamics underlying discourse. Furthermore, it can also be beneficial in discovering hidden meanings and uncovering marginalized voices (Wodak & Meyer, 2015). | Despite its strengths, Discourse Analysis possesses specific weaknesses. This approach may be open to allegations of subjectivity due to its interpretive nature. Furthermore, it can be quite time-consuming and requires the researcher to be familiar with a wide variety of theoretical and analytical frameworks (Parker, 2014). |

Example of Discourse Analysis

Title: The construction of teacher identities in educational policy documents: A critical discourse analysis

Citation: Thomas, S. (2005). The construction of teacher identities in educational policy documents: A critical discourse analysis. Critical Studies in Education, 46 (2), 25-44.

Overview: The author examines how an education policy in one state of Australia positions teacher professionalism and teacher identities. While there are competing discourses about professional identity, the policy framework privileges a narrative that frames the ‘good’ teacher as one that accepts ever-tightening control and regulation over their professional practice.

Read my Full Guide on Discourse Analysis Here

13. Action Research

Definition: Action Research is a qualitative research technique that is employed to bring about change while simultaneously studying the process and results of that change.

This method involves a cyclical process of fact-finding, action, evaluation, and reflection (Greenwood & Levin, 2016).

Typically, Action Research is used in the fields of education, social sciences , and community development. The process isn’t just about resolving an issue but also developing knowledge that can be used in the future to address similar or related problems.

The researcher plays an active role in the research process, which is normally broken down into four steps:

- developing a plan to improve what is currently being done

- implementing the plan

- observing the effects of the plan, and

- reflecting upon these effects (Smith, 2010).

| Action Research has the immense strength of enabling practitioners to address complex situations in their professional context. By fostering reflective practice, it ignites individual and organizational learning. Furthermore, it provides a robust way to bridge the theory-practice divide and can lead to the development of best practices (Zuber-Skerritt, 2019). | Action Research requires a substantial commitment of time and effort. Also, the participatory nature of this research can potentially introduce bias, and its iterative nature can blur the line between where the research process ends and where the implementation begins (Koshy, Koshy, & Waterman, 2010). |

Example of Action Research

Title: Using Digital Sandbox Gaming to Improve Creativity Within Boys’ Writing

Citation: Ellison, M., & Drew, C. (2020). Using digital sandbox gaming to improve creativity within boys’ writing. Journal of Research in Childhood Education , 34 (2), 277-287.

Overview: This was a research study one of my research students completed in his own classroom under my supervision. He implemented a digital game-based approach to literacy teaching with boys and interviewed his students to see if the use of games as stimuli for storytelling helped draw them into the learning experience.

Read my Full Guide on Action Research Here

14. Semiotic Analysis

Definition: Semiotic Analysis is a qualitative method of research that interprets signs and symbols in communication to understand sociocultural phenomena. It stems from semiotics, the study of signs and symbols and their use or interpretation (Chandler, 2017).

In a Semiotic Analysis, signs (anything that represents something else) are interpreted based on their significance and the role they play in representing ideas.

This type of research often involves the examination of images, sounds, and word choice to uncover the embedded sociocultural meanings. For example, an advertisement for a car might be studied to learn more about societal views on masculinity or success (Berger, 2010).

| The prime strength of the Semiotic Analysis lies in its ability to reveal the underlying ideologies within cultural symbols and messages. It helps to break down complex phenomena into manageable signs, yielding powerful insights about societal values, identities, and structures (Mick, 1986). | On the downside, because Semiotic Analysis is primarily interpretive, its findings may heavily rely on the particular theoretical lens and personal bias of the researcher. The ontology of signs and meanings can also be inherently subject to change, in the analysis (Lannon & Cooper, 2012). |

Example of Semiotic Research

Title: Shielding the learned body: a semiotic analysis of school badges in New South Wales, Australia

Citation: Symes, C. (2023). Shielding the learned body: a semiotic analysis of school badges in New South Wales, Australia. Semiotica , 2023 (250), 167-190.

Overview: This study examines school badges in New South Wales, Australia, and explores their significance through a semiotic analysis. The badges, which are part of the school’s visual identity, are seen as symbolic representations that convey meanings. The analysis reveals that these badges often draw on heraldic models, incorporating elements like colors, names, motifs, and mottoes that reflect local culture and history, thus connecting students to their national identity. Additionally, the study highlights how some schools have shifted from traditional badges to modern logos and slogans, reflecting a more business-oriented approach.

15. Qualitative Longitudinal Studies

Definition: Qualitative Longitudinal Studies are a research method that involves repeated observation of the same items over an extended period of time.

Unlike a snapshot perspective, this method aims to piece together individual histories and examine the influences and impacts of change (Neale, 2019).

Qualitative Longitudinal Studies provide an in-depth understanding of change as it happens, including changes in people’s lives, their perceptions, and their behaviors.

For instance, this method could be used to follow a group of students through their schooling years to understand the evolution of their learning behaviors and attitudes towards education (Saldaña, 2003).

| One key strength of Qualitative Longitudinal Studies is its ability to capture change and continuity over time. It allows for an in-depth understanding of individuals or context evolution. Moreover, it provides unique insights into the temporal ordering of events and experiences (Farrall, 2006). | Qualitative Longitudinal Studies come with their own share of weaknesses. Mainly, they require a considerable investment of time and resources. Moreover, they face the challenges of attrition (participants dropping out of the study) and repeated measures that may influence participants’ behaviors (Saldaña, 2014). |

Example of Qualitative Longitudinal Research

Title: Patient and caregiver perspectives on managing pain in advanced cancer: a qualitative longitudinal study

Citation: Hackett, J., Godfrey, M., & Bennett, M. I. (2016). Patient and caregiver perspectives on managing pain in advanced cancer: a qualitative longitudinal study. Palliative medicine , 30 (8), 711-719.

Overview: This article examines how patients and their caregivers manage pain in advanced cancer through a qualitative longitudinal study. The researchers interviewed patients and caregivers at two different time points and collected audio diaries to gain insights into their experiences, making this study longitudinal.

Read my Full Guide on Longitudinal Research Here

16. Open-Ended Surveys

Definition: Open-Ended Surveys are a type of qualitative research method where respondents provide answers in their own words. Unlike closed-ended surveys, which limit responses to predefined options, open-ended surveys allow for expansive and unsolicited explanations (Fink, 2013).

Open-ended surveys are commonly used in a range of fields, from market research to social studies. As they don’t force respondents into predefined response categories, these surveys help to draw out rich, detailed data that might uncover new variables or ideas.

For example, an open-ended survey might be used to understand customer opinions about a new product or service (Lavrakas, 2008).

Contrast this to a quantitative closed-ended survey, like a Likert scale, which could theoretically help us to come up with generalizable data but is restricted by the questions on the questionnaire, meaning new and surprising data and insights can’t emerge from the survey results in the same way.