Biography Online

Top 10 Greatest Scientists

- The story of chemists, physicists, biologists and remarkable scientists who increased our grasp of almost everything around us.

A list of the top 10 scientists of all time with short profiles on their most significant achievements.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “Ten Greatest Scientists” Oxford, UK – www.biographyonline.net . Published 12th Jan. 2011. Last updated 2 March 2018.

Notable missing scientists

100 Scientists Who Shaped World History

100 Scientists Who Shaped World History at Amazon

Related pages

Inventions that changed the world – Famous inventions that made a great difference to the progress of the world, including aluminium, the telephone and the printing press.

81 Comments

Alfred Russel Wallace should be given credit equivalent to Charles Darwin.

- January 03, 2019 12:28 PM

- By Satya Prakash Chaurasia

They positively contributed greatly to our world’ Thanks to them.

- January 01, 2019 8:36 PM

- By Tut Lony

- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

10 Famous Scientists and Their Contributions

Get to know the greatest scientists in the world. learn how these famous scientists changed the world as we know it through their contributions and discoveries..

From unraveling the mysteries of the cosmos to unearthing the origins of humanity, these famous scientists have not only expanded the boundaries of human knowledge but have also profoundly altered the way we live, work, and perceive the world around us. The relentless pursuit of knowledge by these visionary thinkers has propelled humanity forward in ways that were once unimaginable.

These exceptional individuals have made an extraordinary impact on fields including physics, chemistry, biology, astronomy, and numerous others. Their contributions stand as a testament to the transformative power of human curiosity and the enduring impact of those who dared to ask questions, challenge the status quo, and change the world. Join us as we embark on a journey through the lives and legacies of the greatest scientists of all time.

1. Albert Einstein: The Whole Package

Albert Einstein was not only a scientific genius but also a figure of enduring popularity and intrigue. His remarkable contributions to science, which include the famous equation E = mc2 and the theory of relativity , challenged conventional notions and reshaped our understanding of the universe.

Born in Ulm, Germany, in 1879, Einstein was a precocious child. As a teenager, he wrote a paper on magnetic fields. (Einstein never actually failed math, contrary to popular lore.) His career trajectory began as a clerk in the Swiss Patent Office in 1905, where he published his four groundbreaking papers, including his famous equation, E = mc2, which described the relationship between matter and energy.

Contributions

Einstein's watershed year of 1905 marked the publication of his most important papers, addressing topics such as Brownian motion , the photoelectric effect and special relativity. His work in special relativity introduced the idea that space and time are interwoven, laying the foundation for modern astronomy. In 1916, he expanded on his theory of relativity with the development of general relativity, proposing that mass distorts the fabric of space and time.

Although Einstein received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921, it wasn't for his work on general relativity but rather for his discovery of the photoelectric effect. His contributions to science earned him a prestigious place in the scientific community.

Key Moment

A crowd barged past dioramas, glass displays, and wide-eyed security guards in the American Museum of Natural History. Screams rang out as some runners fell and were trampled. Upon arriving at a lecture hall, the mob broke down the door.

The date was Jan. 8, 1930, and the New York museum was showing a film about Albert Einstein and his general theory of relativity. Einstein was not present, but 4,500 mostly ticketless people still showed up for the viewing. Museum officials told them “no ticket, no show,” setting the stage for, in the words of the Chicago Tribune , “the first science riot in history.”

Such was Einstein’s popularity. As a publicist might say, he was the whole package: distinctive look (untamed hair, rumpled sweater), witty personality (his quips, such as God not playing dice, would live on) and major scientific cred (his papers upended physics).

Read More: 5 Interesting Things About Albert Einstein

Einstein, who died of heart failure in 1955 , left behind a profound legacy in the world of science. His life's work extended beyond scientific discoveries, encompassing his role as a public intellectual, civil rights advocate, and pacifist.

Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity remains one of his most celebrated achievements. It predicted the existence of black holes and gravitational waves, with physicists recently measuring the waves from the collision of two black holes over a billion light-years away. General relativity also underpins the concept of gravitational lensing, enabling astronomers to study distant cosmic objects in unprecedented detail.

“Einstein remains the last, and perhaps only, physicist ever to become a household name,” says James Overduin, a theoretical physicist at Towson University in Maryland.

Einstein's legacy goes beyond his scientific contributions. He is remembered for his imaginative thinking, a quality that led to his greatest insights. His influence as a public figure and his advocacy for civil rights continue to inspire generations.

“I am enough of an artist to draw freely upon my imagination,” he said in a Saturday Evening Post interview. “Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.”

— Mark Barna

Read More: 20 Brilliant Albert Einstein Quotes

2. Marie Curie: She Went Her Own Way

Marie Curie's remarkable journey to scientific acclaim was characterized by determination and a thirst for knowledge. Living amidst poverty and political turmoil, her unwavering passion for learning and her contributions to the fields of physics and chemistry have made an everlasting impact on the world of science.

Marie Curie , born as Maria Salomea Sklodowska in 1867 in Warsaw, Poland, faced immense challenges during her early life due to both her gender and her family's financial struggles. Her parents, fervent Polish patriots, sacrificed their wealth in support of their homeland's fight for independence from Russian, Austrian, and Prussian rule. Despite these hardships, Marie's parents, who were educators themselves, instilled a deep love for learning and Polish culture in her.

Marie and her sisters were initially denied higher education opportunities due to societal restrictions and lack of financial resources. In response, Marie and her sister Bronislawa joined a clandestine organization known as the Flying University, aimed at providing Polish education, forbidden under Russian rule.

Marie Curie's path to scientific greatness began when she arrived in Paris in 1891 to pursue higher education. Inspired by the work of French physicist Henri Becquerel, who discovered the emissions of uranium, Marie chose to explore uranium's rays for her Ph.D. thesis. Her research led her to the groundbreaking discovery of radioactivity, revealing that matter could undergo atomic-level transformations.

Marie Curie collaborated with her husband, Pierre Curie, and together they examined uranium-rich minerals, ultimately discovering two new elements, polonium and radium. Their work was published in 1898, and within just five months, they announced the discovery of radium.

In 1903, Marie Curie, Pierre Curie, and Henri Becquerel were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their pioneering work in radioactivity. Marie became the first woman to receive a Nobel Prize, marking a historic achievement.

Read More: 5 Things You Didn't Know About Marie Curie

Tragedy struck in 1906 when Pierre Curie died suddenly in a carriage accident. Despite her grief, Marie Curie persevered and continued her research, taking over Pierre's position at the University of Paris. In 1911, she earned her second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry, for her remarkable contributions to the fields of polonium and radium.

Marie Curie's legacy extended beyond her Nobel Prizes. She made significant contributions to the fields of radiology and nuclear physics. She founded the Radium Institute in Paris, which produced its own Nobel laureates, and during World War I, she led France's first military radiology center, becoming the first female medical physicist.

Marie Curie died in 1934 from a type of anemia that likely stemmed from her exposure to such extreme radiation during her career. In fact, her original notes and papers are still so radioactive that they’re kept in lead-lined boxes, and you need protective gear to view them

Marie Curie's legacy endures as one of the greatest scientists of all time. She remains the only person to receive Nobel Prizes in two different scientific fields, a testament to her exceptional contributions to science. Her groundbreaking research in radioactivity revolutionized our understanding of matter and energy, leaving her mark on the fields of physics, chemistry, and medicine.

— Lacy Schley

Read More: Marie Curie: Iconic Scientist, Nobel Prize Winner … War Hero?

3. Isaac Newton: The Man Who Defined Science on a Bet

Isaac Newton was an English mathematician, physicist and astronomer who is widely recognized as one of the most influential scientists in history. He made groundbreaking contributions to various fields of science and mathematics and is considered one of the key figures in the scientific revolution of the 17th century.

Isaac Newton was born on Christmas Day in 1642. Despite being a sickly infant, his survival was an achievement in itself. Just 23 years later, with Cambridge University closed due to the plague, Newton embarked on groundbreaking discoveries that would bear his name. He invented calculus, a new form of mathematics, as part of his scientific journey.

Newton's introverted nature led him to withhold his findings for decades. It was only through the persistent efforts of his friend, Edmund Halley, who was famous for discovering comets, that Newton finally agreed to publish. Halley's interest was piqued due to a bet about planetary orbits, and Newton, having already solved the problem, astounded him with his answer.

Read More: 5 Eccentric Facts About Isaac Newton

The culmination of Newton's work was the "Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica," commonly known as the Principia , published in 1687. This monumental work not only described the motion of planets and projectiles but also revealed the unifying force of gravity, demonstrating that it governed both heavenly and earthly bodies. Newton's laws became the key to unlocking the universe's mysteries.

Newton's dedication to academia was unwavering. He rarely left his room except to deliver lectures, even if it meant addressing empty rooms. His contributions extended beyond the laws of motion and gravitation to encompass groundbreaking work in optics, color theory, the development of reflecting telescopes bearing his name, and fundamental advancements in mathematics and heat.

In 1692, Newton faced a rare failure and experienced a prolonged nervous breakdown, possibly exacerbated by mercury poisoning from his alchemical experiments. Although he ceased producing scientific work, his influence in the field persisted.

Achievements

Newton spent his remaining three decades modernizing England's economy and pursuing criminals. In 1696, he received a royal appointment as the Warden of the Mint in London. Despite being viewed as a cushy job with a handsome salary, Newton immersed himself in the role. He oversaw the recoinage of English currency, provided economic advice, established the gold standard, and introduced ridged coins that prevented the tampering of precious metals. His dedication extended to pursuing counterfeiters vigorously, even infiltrating London's criminal networks , and witnessing their executions.

Newton's reputation among his peers was marred by his unpleasant demeanor. He had few close friends, never married, and was described as "insidious, ambitious, and excessively covetous of praise, and impatient of contradiction" by Astronomer Royal John Flamsteed. Newton held grudges for extended periods and engaged in famous feuds, notably with German scientist Gottfried Leibniz over the invention of calculus and English scientist Robert Hooke.

Isaac Newton's legacy endures as one of the world's greatest scientists. His contributions to physics, mathematics, and various scientific disciplines shifted human understanding. Newton's laws of motion and gravitation revolutionized the field of physics and continue to be foundational principles.

His work in optics and mathematics laid the groundwork for future scientific advancements. Despite his complex personality, Newton's legacy as a scientific visionary remains unparalleled.

How fitting that the unit of force is named after stubborn, persistent, amazing Newton, himself a force of nature.

— Bill Andrews

Read More: Isaac Newton, World's Most Famous Alchemist

4. Charles Darwin: Delivering the Evolutionary Gospel

Charles Darwin has become one of the world's most renowned scientists. His inspiration came from a deep curiosity about beetles and geology, setting him on a transformative path. His theory of evolution through natural selection challenged prevailing beliefs and left an enduring legacy that continues to shape the field of biology and our understanding of life on Earth.

Charles Darwin , an unlikely revolutionary scientist, began his journey with interests in collecting beetles and studying geology. As a young man, he occasionally skipped classes at the University of Edinburgh Medical School to explore the countryside. His path to becoming the father of evolutionary biology took an unexpected turn in 1831 when he received an invitation to join a world-spanning journey aboard the HMS Beagle .

During his five-year voyage aboard the HMS Beagle, Darwin observed and documented geological formations, various habitats and the diverse flora and fauna across the Southern Hemisphere. His observations led to a paradigm-shifting realization that challenged the prevailing Victorian-era theories of animal origins rooted in creationism.

Darwin noticed subtle variations within the same species based on their environments, exemplified by the unique beak shapes of Galapagos finches adapted to their food sources. This observation gave rise to the concept of natural selection, suggesting that species could change over time due to environmental factors, rather than divine intervention.

Read More: 7 Things You May Not Know About Charles Darwin

Upon his return, Darwin was initially hesitant to publish his evolutionary ideas, instead focusing on studying his voyage samples and producing works on geology, coral reefs and barnacles. He married his first cousin, Emma Wedgwood, and they had ten children, with Darwin actively engaging as a loving and attentive father — an uncommon practice among eminent scientists of his era.

Darwin's unique interests in taxidermy , unusual food and his struggle with ill health did not deter him from his evolutionary pursuits. Over two decades, he meticulously gathered overwhelming evidence in support of evolution.

Publication

All of his observations and musings eventually coalesced into the tour de force that was On the Origin of Species , published in 1859 when Darwin was 50 years old. The 500-page book sold out immediately, and Darwin would go on to produce six editions, each time adding to and refining his arguments.

In non-technical language, the book laid out a simple argument for how the wide array of Earth’s species came to be. It was based on two ideas: that species can change gradually over time, and that all species face difficulties brought on by their surroundings. From these basic observations, it stands to reason that those species best adapted to their environments will survive and those that fall short will die out.

Despite facing fierce criticism from proponents of creationism and the religious establishment, Darwin's theory of natural selection and evolution eventually gained acceptance in the 1930s. His work revolutionized scientific thought and remains largely intact to this day.

His theory, meticulously documented and logically sound, has withstood the test of time and scrutiny. Jerry Coyne, a professor emeritus at the University of Chicago, emphasizes the profound impact of Darwin's theory, stating that it "changed people’s views in so short a time" and that "there’s nothing you can really say to go after the important aspects of Darwin’s theory."

— Nathaniel Scharping

Read More: 8 Inspirational Sayings From Charles Darwin

5. Nikola Tesla: Wizard of the Industrial Revolution

Nikola Tesla grips his hat in his hand. He points his cane toward Niagara Falls and beckons bystanders to turn their gaze to the future. This bronze Tesla — a statue on the Canadian side — stands atop an induction motor, the type of engine that drove the first hydroelectric power plant.

Nikola Tesla exhibited a remarkable aptitude for science and invention from an early age. His work in electricity, magnetism and wireless power transmission concepts, established him as an eccentric but brilliant pioneer in the field of electrical engineering.

Nikola Tesla , a Serbian-American engineer, was born in 1856 in what is now Croatia. His pioneering work in the field of electrical engineering laid the foundation for our modern electrified world. Tesla's groundbreaking designs played a crucial role in advancing alternating current (AC) technology during the early days of the electric age, enabling the transmission of electric power over vast distances, ultimately lighting up American homes.

One of Tesla's most significant contributions was the development of the Tesla coil , a high-voltage transformer that had a profound impact on electrical engineering. His innovative techniques allowed for wireless transmission of power, a concept that is still being explored today, particularly in the field of wireless charging, including applications in cell phones.

Tesla's visionary mind led him to propose audacious ideas, including a grand plan involving a system of towers that could harness energy from the environment and transmit both signals and electricity wirelessly around the world. While these ideas were intriguing, they were ultimately deemed impractical and remained unrealized. Tesla also claimed to have invented a "death ray," adding to his mystique.

Read More: What Did Nikola Tesla Do? The Truth Behind the Legend

Tesla's eccentric genius and prolific inventions earned him widespread recognition during his lifetime. He held numerous patents and made significant contributions to the field of electrical engineering. While he did not invent alternating current (AC), he played a pivotal role in its development and promotion. His ceaseless work and inventions made him a household name, a rare feat for scientists in his era.

In recent years, Tesla's legacy has taken on a life of its own, often overshadowing his actual inventions. He has become a symbol of innovation and eccentricity, inspiring events like San Diego Comic-Con, where attendees dress as Tesla. Perhaps most notably, the world's most famous electric car company bears his name, reflecting his ongoing influence on the electrification of transportation.

While Tesla's mystique sometimes veered into the realm of self-promotion and fantastical claims, his genuine contributions to electrical engineering cannot be denied. He may not have caused earthquakes with his inventions or single handedly discovered AC, but his visionary work and impact on the electrification of the world continue to illuminate our lives.

— Eric Betz

Read More: These 7 Famous Physicists Are Still Alive Today

6. Galileo Galilei: Discoverer of the Cosmos

Galileo Galilei , an Italian mathematician, made a pivotal contribution to modern astronomy around December 1609. At the age of 45, he turned a telescope towards the moon and ushered in a new era in the field.

His observations unveiled remarkable discoveries, such as the presence of four large moons orbiting Jupiter and the realization that the Milky Way's faint glow emanated from countless distant stars. Additionally, he identified sunspots on the surface of the sun and observed the phases of Venus, providing conclusive evidence that Venus orbited the sun within Earth's own orbit.

While Galileo didn't invent the telescope and wasn't the first to use one for celestial observations, his work undeniably marked a turning point in the history of science. His groundbreaking findings supported the heliocentric model proposed by Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, who had revolutionized astronomy with his sun-centered solar system model .

Beyond his astronomical observations, Galileo made significant contributions to the understanding of motion. He demonstrated that objects dropped simultaneously would hit the ground at the same time, irrespective of their size, illustrating that gravity isn't dependent on an object's mass. His law of inertia also played a critical role in explaining the Earth's rotation.

Read More: 12 Fascinating Facts About Galileo Galilei You May Not Know

Galileo's discoveries, particularly his support for the Copernican model of the solar system, brought him into conflict with the Roman Catholic Church. In 1616, an inquisition ordered him to cease promoting heliocentrism, as it contradicted the church's geocentric doctrine based on Aristotle's outdated views of the cosmos.

The situation worsened in 1633 when Galileo published a work comparing the Copernican and Ptolemaic systems, further discrediting the latter. Consequently, the church placed him under house arrest, where he remained until his death in 1642.

Galileo's legacy endured despite the challenges he faced from religious authorities. His observations and pioneering work on celestial bodies and motion laid the foundation for modern astronomy and physics.

His law of inertia, in particular, would influence future scientists, including Sir Isaac Newton, who built upon Galileo's work to formulate a comprehensive set of laws of motion that continue to guide spacecraft navigation across the solar system today. Notably, NASA's Galileo mission to Jupiter, launched centuries later, demonstrated the enduring relevance of Galileo's contributions to the field of space exploration.

Read More: Galileo Galilei's Legacy Went Beyond Science

7. Ada Lovelace: The Enchantress of Numbers

Ada Lovelace defied the conventions of her era and transformed the world of computer science. She is known as the world's first computer programmer. Her legacy endures, inspiring generations of computer scientists and earning her the title of the "Enchantress of Numbers.”

Ada Lovelace, born Ada Byron, made history as the world's first computer programmer, a remarkable achievement considering she lived a century before the advent of modern computers. Her journey into the world of mathematics and computing began in the early 1830s when she was just 17 years old.

Ada, the only legitimate child of the poet Lord Byron, entered into a pivotal collaboration with British mathematician, inventor, and engineer Charles Babbage. Babbage had conceived plans for an intricate machine called the Difference Engine — essentially a massive mechanical calculator.

Read More: Meet Ada Lovelace, The First Computer Programmer

At a gathering in the 1830s, Babbage exhibited an incomplete prototype of his Difference Engine. Among the attendees was the young Ada Lovelace, who, despite her age, grasped the workings of the machine. This encounter marked the beginning of a profound working relationship and close friendship between Lovelace and Babbage that endured until her untimely death in 1852 at the age of 36. Inspired by Babbage's innovations, Lovelace recognized the immense potential of his latest concept, the Analytical Engine.

The Analytical Engine was more than a mere calculator. Its intricate mechanisms, coupled with the ability for users to input commands through punch cards, endowed it with the capacity to perform a wide range of mathematical tasks. Lovelace, in fact, went a step further by crafting instructions for solving a complex mathematical problem, effectively creating what many historians later deemed the world's first computer program. In her groundbreaking work, Lovelace laid the foundation for computer programming, defining her legacy as one of the greatest scientists.

Ada Lovelace's contributions to the realm of "poetical science," as she termed it, are celebrated as pioneering achievements in computer programming and mathematics. Despite her tumultuous personal life marked by gambling and scandal, her intellectual brilliance and foresight into the potential of computing machines set her apart. Charles Babbage himself described Lovelace as an "enchantress" who wielded a remarkable influence over the abstract realm of science, a force equivalent to the most brilliant male intellects of her time.

Read More: Meet 10 Women in Science Who Changed the World

8. Pythagoras: Math's Mystery Man

Pythagoras left an enduring legacy in the world of mathematics that continues to influence the field to this day. While his famous Pythagorean theorem , which relates the sides of a right triangle, is well-known, his broader contributions to mathematics and his belief in the fundamental role of numbers in the universe shaped the foundations of geometry and mathematical thought for centuries to come.

Pythagoras , a Greek philosopher and mathematician, lived in the sixth century B.C. He is credited with the Pythagorean theorem, although the origins of this mathematical concept are debated.

Pythagoras is most famous for the Pythagorean theorem, which relates the lengths of the sides of a right triangle. While he may not have been the first to discover it, he played a significant role in its development. His emphasis on the importance of mathematical concepts laid the foundation for modern geometry.

Pythagoras did not receive formal awards, but his legacy in mathematics and geometry is considered one of the cornerstones of scientific knowledge.

Pythagoras' contributions to mathematics, particularly the Pythagorean theorem, have had a lasting impact on science and education. His emphasis on the importance of mathematical relationships and the certainty of mathematical proofs continues to influence the way we understand the world.

Read More: The Origin Story of Pythagoras and His Cult Followers

9. Carl Linnaeus: Say His Name(s)

Carl Linnaeus embarked on a mission to improve the chaos of naming living organisms. His innovative system of binomial nomenclature not only simplified the process of scientific communication but also laid the foundation for modern taxonomy, leaving an enduring legacy in the field of biology.

It started in Sweden: a functional, user-friendly innovation that took over the world, bringing order to chaos. No, not an Ikea closet organizer. We’re talking about the binomial nomenclature system , which has given us clarity and a common language, devised by Carl Linnaeus.

Linnaeus, born in southern Sweden in 1707, was an “intensely practical” man, according to Sandra Knapp, a botanist and taxonomist at the Natural History Museum in London. He lived at a time when formal scientific training was scant and there was no system for referring to living things. Plants and animals had common names, which varied from one location and language to the next, and scientific “phrase names,” cumbersome Latin descriptions that could run several paragraphs.ccjhhg

While Linnaeus is often hailed as the father of taxonomy, his primary focus was on naming rather than organizing living organisms into evolutionary hierarchies. The task of ordering species would come later, notably with the work of Charles Darwin in the following century. Despite advancements in our understanding of evolution and the impact of genetic analysis on biological classification, Linnaeus' naming system endures as a simple and adaptable means of identification.

The 18th century was also a time when European explorers were fanning out across the globe, finding ever more plants and animals new to science.

“There got to be more and more things that needed to be described, and the names were becoming more and more complex,” says Knapp.

Linnaeus, a botanist with a talent for noticing details, first used what he called “trivial names” in the margins of his 1753 book Species Plantarum . He intended the simple Latin two-word construction for each plant as a kind of shorthand, an easy way to remember what it was.

“It reflected the adjective-noun structure in languages all over the world,” Knapp says of the trivial names, which today we know as genus and species. The names moved quickly from the margins of a single book to the center of botany, and then all of biology. Linnaeus started a revolution — positioning him as one of the greatest scientists — but it was an unintentional one.

Today we regard Linnaeus as the father of taxonomy, which is used to sort the entire living world into evolutionary hierarchies, or family trees. But the systematic Swede was mostly interested in naming things rather than ordering them, an emphasis that arrived the next century with Charles Darwin.

As evolution became better understood and, more recently, genetic analysis changed how we classify and organize living things, many of Linnaeus’ other ideas have been supplanted. But his naming system, so simple and adaptable, remains.

“It doesn’t matter to the tree in the forest if it has a name,” Knapp says. “But by giving it a name, we can discuss it. Linnaeus gave us a system so we could talk about the natural world.”

— Gemma Tarlach

Read More: Is Plant Communication a Real Thing?

10. Rosalind Franklin: The Hero Denied Her Due

Rosalind Franklin, a brilliant and tenacious scientist, transformed the world of molecular biology. Her pioneering work in X-ray crystallography and groundbreaking research on the structure of DNA propelled her to the forefront of scientific discovery. Yet, her remarkable contributions were often overshadowed, and her legacy is not only one of scientific excellence but also a testament to the persistence and resilience of a scientist who deserved greater recognition in her time.

Rosalind Franklin , one of the greatest scientists of her time, was a British-born firebrand and perfectionist. While she had a reputation for being somewhat reserved and difficult to connect with, those who knew her well found her to be outgoing and loyal. Franklin's brilliance shone through in her work, particularly in the field of X-ray crystallography , an imaging technique that revealed molecular structures based on scattered X-ray beams. Her early research on the microstructures of carbon and graphite remains influential in the scientific community.

However, it was Rosalind Franklin's groundbreaking work with DNA that would become her most significant contribution. During her time at King's College London in the early 1950s, she came close to proving the double-helix theory of DNA. Her achievement was epitomized in "photograph #51," which was considered the finest image of a DNA molecule at that time. Unfortunately, her work was viewed by others, notably James Watson and Francis Crick.

Watson saw photograph #51 through her colleague Maurice Wilkins, and Crick received unpublished data from a report Franklin had submitted to the council. In 1953, Watson and Crick published their iconic paper in "Nature," loosely citing Franklin's work, which also appeared in the same issue.

Rosalind Franklin's pivotal role in elucidating the structure of DNA was overlooked when the Nobel Prize was awarded in 1962 to James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins. This omission is widely regarded as one of the major snubs of the 20th century in the field of science.

Despite her groundbreaking work and significant contributions to science, Franklin's life was tragically cut short. In 1956, at the height of her career, she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, possibly linked to her extensive X-ray work. Remarkably, she continued to work in the lab until her passing in 1958 at the young age of 37.

Rosalind Franklin's legacy endures not only for her achievements but also for the recognition she deserved but did not receive during her lifetime. She was known for her extreme clarity and perfectionism in all her scientific endeavors, changing the field of molecular biology. While many remember her for her contributions, she is also remembered for how her work was overshadowed and underappreciated, a testament to her enduring influence on the world of science.

“As a scientist, Miss Franklin was distinguished by extreme clarity and perfection in everything she undertook,” Bernal wrote in her obituary, published in Nature . Though it’s her achievements that close colleagues admired, most remember Franklin for how she was forgotten.

— Carl Engelking

Read More: The Unsung Heroes of Science

More Greatest Scientists: Our Personal Favorites

Isaac Asimov (1920–1992) Asimov was my gateway into science fiction, then science, then everything else. He penned some of the genre’s most iconic works — fleshing out the laws of robotics, the messiness of a galactic empire, the pitfalls of predicting the future — in simple, effortless prose. A trained biochemist, the Russian-born New Yorker wrote prolifically, producing over 400 books, not all science-related: Of the 10 Dewey Decimal categories, he has books in nine. — B.A.

Richard Feynman (1918–1988) Feynman played a part in most of the highlights of 20th-century physics. In 1941, he joined the Manhattan Project. After the war, his Feynman diagrams — for which he shared the ’65 Nobel Prize in Physics — became the standard way to show how subatomic particles interact. As part of the 1986 space shuttle Challenger disaster investigation, he explained the problems to the public in easily understandable terms, his trademark. Feynman was also famously irreverent, and his books pack lessons I live by. — E.B.

Robert FitzRoy (1805–1865) FitzRoy suffered for science, and for that I respect him. As captain of the HMS Beagle , he sailed Charles Darwin around the world, only to later oppose his shipmate’s theory of evolution while waving a Bible overhead. FitzRoy founded the U.K.’s Met Office in 1854, and he was a pioneer of prediction; he coined the term weather forecast. But after losing his fortunes, suffering from depression and poor health, and facing fierce criticism of his forecasting system, he slit his throat in 1865. — C.E.

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) Lamarck may be remembered as a failure today, but to me, he represents an important step forward for evolutionary thinking . Before he suggested that species could change over time in the early 19th century, no one took the concept of evolution seriously. Though eventually proven wrong, Lamarck’s work brought the concept of evolution into the light and would help shape the theories of a young Charles Darwin. Science isn’t all about dazzling successes; it’s also a story of failures surmounted and incremental advances. — N.S.

Lucretius (99 B.C.–55 B.C.) My path to the first-century B.C. Roman thinker Titus Lucretius Carus started with Ralph Waldo Emerson and Michele de Montaigne, who cited him in their essays. Lucretius’ only known work, On the Nature of Things, is remarkable for its foreshadowing of Darwinism, humans as higher primates, the study of atoms and the scientific method — all contemplated in a geocentric world ruled by eccentric gods. — M.B.

Katharine McCormick (1875–1967) McCormick planned to attend medical school after earning her biology degree from MIT in 1904. Instead, she married rich. After her husband’s death in 1947, she used her inheritance to provide crucial funding for research on the hormonal birth control pill . She also fought to make her alma mater more accessible to women, leading to an all-female dormitory, allowing more women to enroll. As a feminist interested in science, I’d love to be friends with this badass advocate for women’s rights. — L.S.

John Muir (1838–1914) In 1863, Muir abandoned his eclectic combination of courses at the University of Wisconsin to wander instead the “University of the Wilderness” — a school he never stopped attending. A champion of the national parks (enough right there to make him a hero to me!), Muir fought vigorously for conservation and warned, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” It’s a reminder we need today, more than ever. — Elisa Neckar

Rolf O. Peterson (1944–) Peterson helms the world’s longest-running study of the predator-prey relationship in the wild, between wolves and moose on Isle Royale in the middle of Lake Superior. He’s devoted more than four decades to the 58-year wildlife ecology project, a dedication and passion indicative, to me, of what science is all about. As the wolf population has nearly disappeared and moose numbers have climbed, patience and emotional investment like his are crucial in the quest to learn how nature works. — Becky Lang

Marie Tharp (1920–2006) I love maps. So did geologist and cartographer Tharp . In the mid-20th century, before women were permitted aboard research vessels, Tharp explored the oceans from her desk at Columbia University. With the seafloor — then thought to be nearly flat — her canvas, and raw data her inks, she revealed a landscape of mountain ranges and deep trenches. Her keen eye also spotted the first hints of plate tectonics at work beneath the waves. Initially dismissed, Tharp’s observations would become crucial to proving continental drift. — G.T.

Read more: The Dynasties That Changed Science

Making Science Popular With Other Greatest Scientists

Science needs to get out of the lab and into the public eye. Over the past hundred years or so, these other greatest scientists have made it their mission. They left their contributions in multiple sciences while making them broadly available to the general public.

Sean M. Carroll (1966– ) : The physicist (and one-time Discover blogger) has developed a following among space enthusiasts through his lectures, television appearances and books, including The Particle at the End of the Universe, on the Higgs boson .

Rachel Carson (1907–1964) : With her 1962 book Silent Spring , the biologist energized a nascent environmental movement. In 2006, Discover named Silent Spring among the top 25 science books of all time.

Richard Dawkins (1941– ) : The biologist, a charismatic speaker, first gained public notoriety in 1976 with his book The Selfish Gene , one of his many works on evolution .

Jane Goodall (1934– ) : Studying chimpanzees in Tanzania, Goodall’s patience and observational skills led to fresh insights into their behavior — and led her to star in a number of television documentaries.

Stephen Jay Gould (1941–2002) : In 1997, the paleontologist Gould was a guest on The Simpson s, a testament to his broad appeal. Among scientists, Gould was controversial for his idea of evolution unfolding in fits and starts rather than in a continuum.

Stephen Hawking (1942–2018) : His books’ titles suggest the breadth and boldness of his ideas: The Universe in a Nutshell, The Theory of Everything . “My goal is simple,” he has said. “It is a complete understanding of the universe, why it is as it is and why it exists at all.”

Aldo Leopold (1887–1948) : If Henry Thoreau and John Muir primed the pump for American environmentalism, Leopold filled the first buckets . His posthumously published A Sand County Almanac is a cornerstone of modern environmentalism.

Bill Nye (1955– ) : What should an engineer and part-time stand-up comedian do with his life? For Nye, the answer was to become a science communicator . In the ’90s, he hosted a popular children’s science show and more recently has been an eloquent defender of evolution in public debates with creationists.

Oliver Sacks (1933–2015) : The neurologist began as a medical researcher , but found his calling in clinical practice and as a chronicler of strange medical maladies, most famously in his book The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.

Carl Sagan (1934–1996) : It’s hard to hear someone say “billions and billions” and not hear Sagan’s distinctive voice , and remember his 1980 Cosmos: A Personal Voyage miniseries. Sagan brought the wonder of the universe to the public in a way that had never happened before.

Neil deGrasse Tyson (1958– ) : The astrophysicist and gifted communicator is Carl Sagan’s successor as champion of the universe . In a nod to Sagan’s Cosmos , Tyson hosted the miniseries Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey in 2014.

E.O. Wilson (1929–2021) : The prolific, Pulitzer Prize-winning biologist first attracted broad public attention with 1975’s Sociobiology: The New Synthesis . His subsequent works have filled many a bookshelf with provocative discussions of biodiversity, philosophy and the animals he has studied most closely: ants. — M.B.

Read More: Who Was Anna Mani, and How Was She a Pioneer for Women in STEM?

Science Stars: The Next Generation

As science progresses, so does the roll call of new voices and greatest scientists serving as bridges between lab and layman. Here are some of our favorite emerging science stars:

British physicist Brian Cox became a household name in the U.K. in less than a decade, thanks to his accessible explanations of the universe in TV and radio shows, books and public appearances.

Neuroscientist Carl Hart debunks anti-science myths supporting misguided drug policies via various media, including his memoir High Price .

From the Amazon forest to the dissecting table, YouTube star and naturalist Emily Graslie brings viewers into the guts of the natural world, often literally.

When not talking dinosaurs or head transplants on Australian radio, molecular biologist Upulie Divisekera coordinates @RealScientists , a rotating Twitter account for science outreach.

Mixing pop culture and chemistry, analytical chemist Raychelle Burks demystifies the molecules behind poisons, dyes and even Game of Thrones via video, podcast and blog.

Climate scientist and evangelical Christian Katharine Hayhoe preaches beyond the choir about the planetary changes humans are causing in PBS’ Global Weirding video series. — Ashley Braun

Read More: 6 Famous Archaeologists You Need to Know About

This article was originally published on April 11, 2017 and has since been updated with new information by the Discover staff.

- solar system

Sign up for our weekly science updates.

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Biographies

Scientists and inventors.

- Benjamin Banneker - Scientist and astronomer from the 1700s who wrote a popular almanac.

- Alexander Graham Bell - Invented the telephone.

- Rachel Carson - Founder of environmental science.

- George Washington Carver - Botanist who was called the "farmers best friend."

- Francis Crick and James Watson - Discovered the structure of the DNA molecule.

- Marie Curie - Physicist who discovered radioactivity.

- Leonardo da Vinci - Inventor and artist from the Renaissance.

- Charles Drew - Doctor and scientist who helped create blood banks for World War II.

- Thomas Edison - Invented the light bulb, phonograph, and the motion picture.

- Albert Einstein - Came up with the Theory of Relativity and the equation E=mc 2 .

- Henry Ford - Invented the Model T Ford, the first mass produced car.

- Ben Franklin - Inventor and Founding Father of the United States.

- Robert Fulton - Built the first commercially successful steamboat.

- Galileo - First used the telescope to view the planets and stars.

- Jane Goodall - Studied chimpanzees in the wild for many years.

- Johannes Gutenberg - Invented the printing press.

- Stephen Hawking - Known for Hawking Radiation and writing A Brief History in Time .

- Antoine Lavoisier - Father of modern chemistry.

- James Naismith - Invented the sport of basketball.

- Isaac Newton - Discovered the theory of gravity and the three laws of motion.

- Louis Pasteur - Discovered pasteurization, vaccines, and founded the science of germ theory.

- Eli Whitney - Invented the cotton gin.

- The Wright Brothers - Invented the first airplane.

- Astronomer - Studies the planets, stars, and galaxies.

- Botanist - Studies plant life.

- Chemist - Studies chemistry and the behavior, properties, and composition of matter.

- Cytologist - Studies cells.

- Ecologist - Studies the relationship between living organisms and the environment.

- Entomologist - Studies insects.

- Geneticist - Studies genes, DNA, and the hereditary characteristics of living organisms.

- Geologist - Studies the properties of matter that makes up Earth as well as the forces that shaped it.

- Marine biologist - Studies the living organisms that live in the ocean and other bodies of water.

- Microbiologist - Studies microscopic life forms such as bacteria and protists.

- Meteorologist - Studies the Earth's atmosphere including the weather.

- Nuclear physicist - Studies the interactions and make up of the atom.

- Ornithologist - Studies birds.

- Paleontologist - Studies prehistoric life and fossils including dinosaurs.

- Pathologist - Studies diseases caused by pathogens such as bacteria and viruses.

- Seismologist - Studies earthquakes and the movements of the Earth's crust.

- Zoologist - Studies animals.

- Art History

- U.S. History

- Famous Scientists

Scientific discoveries over the centuries have helped shape the way we live today. Without pioneering scientists working towards cures for diseases, new inventions, and better ways to do things, life today would be different. Here are some of the most influential visionaries throughout history, organized in chronological order, who have made a significant contribution to the scientific community and to our everyday lives.

Scientists of Antiquity

Scientists of the Middle Ages

Scientists of the Scientific Revolution

Scientists of the Age of Enlightenment

Scientists of the 19th Century

Scientists of the 20th Century

Written by: Chad A. Hagy

- Famous African Americans

- Famous Hispanic Americans

- Famous Astronomers

- Famous Biologists

- Famous Chemists

- Famous Physicists

- Famous Female Scientists

- Famous Mathematicians

- Famous Military Leaders

- Famous Philosophers

- Famous Authors

- Famous Composers

- Famous Golfers

- Famous Explorers

Copyright © 2020 · Totallyhistory.com · All Rights Reserved. | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Contact Us

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Alan Turing

By: Joseph Bennington-Castro

Published: May 30, 2024

Alan Mathison Turing (1912–1954) was a talented British mathematician and logician whose work laid the foundation for modern computer science and artificial intelligence. He made significant contributions to the field of cryptography and codebreaking in World War II , and was instrumental in breaking Nazi communication encryptions. Near the end of his life, he was convicted of homosexuality and was subsequently chemically castrated. He received a royal pardon for this conviction some 60 years after his death.

Alan Turing was born on June 23, 1912, in Paddington, London, to upper-middle-class British parents, Julius Mathison and Ethel Sara Turing. An intelligent child, Turing spent much of his early life fostered in various English homes with his elder brother John—Julius and Ethel lived in India while Julius worked in the Indian Civil Service—and was often a lonely child. As biographer Andrew Hodges put it, Turing’s life was one of “an isolated and autonomous mind.”

Turing was fascinated with science, but he found little encouragement to pursue his interests from his foster homes or even his mother, who was fearful he would not be accepted into English public school. At 13 years old, however, he was accepted into a boarding school called Sherborne School, where he studied advanced scientific concepts like relativity on his own.

At Sherborne School, Turing formed a strong bond with fellow student Christopher Morcom, who inspired him to communicate more and focus on academic success. But Christopher died suddenly of tuberculosis in 1930, devastating Turing, who questioned whether his friend’s mind somehow lived on in matter. He turned to studying quantum mechanics for answers, his emotional pain turning into a scientific and intellectual fascination with the mind and brain that would underlie his later work.

Father of Modern Computer Science

In 1931, Turing began attending King’s College (University of Cambridge), a progressive new home that both fostered his scientific curiosities and helped further define his homosexual identity. Upon graduation, he was elected a Fellow at the college in 1935 and a year later delivered his foundational paper on the universal Turing machine.

This hypothetical singular machine could theoretically compute anything computable or solve any well-defined task when given a set of pre-defined rules or instructions. Impossible to build, his proposed device laid the groundwork for modern computers, earning Turing the posthumous title, “the father of modern computer science.”

Turing left Britain to study cryptography and earn a Ph.D. in mathematics from Princeton University in 1938. He returned to Cambridge to work with the British code-breaking organization, the Government Code and Cypher School, at Bletchley Park (the British government’s wartime communications hub) in September 1939.

World War II Hero

During World War II, Turing devoted his brilliance to code breaking. Somewhat resembling a large typewriter, the German cyphering machine Enigma replaced a text’s letters with random ones selected using a set of internal rotors. It could generate billions of possible combinations, making the German military’s coded messages seemingly impossible to understand.

Turing, joined by other mathematicians at Bletchley Park, cracked the Enigma code quickly after he came to the organization. He and his codebreaking colleagues (Cambridge mathematician W. G. Welchman, especially) developed another machine called the bombe, which mimicked the workings of Enigma’s rotors to test potential ciphers.

Bletchley Park installed a prototype bombe called Victory in the spring of 1940. Within a few years, the bombes were cracking roughly two Enigma messages each minute. The German military would later switch to a more complex device called Lorenz, but Turing developed a technique to crack even these messages. Turing's contributions to the war effort saved millions of lives and shorten the war by two to four years, according to some historians.

Once solitary in his life, Turing became the chief scientific figure at Bletchley Park and had garnered attention and respect from his colleagues, who called him “Prof.” He was known to be eccentric and awkward, with characteristics ranging from solitary and gloomy to eager and vivacious.

He found a strong companionship with fellow mathematician Joan Clarke, to whom he even proposed marriage. Though Joan gladly accepted, Turing quickly retracted, telling her of his homosexuality.

The Turing Test

Following World War II and still working in secret with the government, Turing moved to London to work for the National Physics Laboratory (NPL), where he sought to “build a brain,” a device akin to modern computers that could store programs in its memory. He spearheaded the design for the Automatic Computing Engine—which NPL deemed too complex and expensive to build at the time—that would influence the design of computers to come.

Turing left NPL in 1948 to work on another computer for Manchester University called the Manchester Mark I. While at Manchester in 1950, he published a famous paper in which he proposed an experiment called the “Turing test” to determine whether a computer could imitate human conservation. This test would become a foundational part of the field of artificial intelligence .

He then turned his attention to trying to understand how patterns in nature, such as a zebra’s stripes, arise, publishing a seminal paper on the topic of morphogenesis.

Conviction and Death

Turing's scientific work came to an abrupt end in 1952. Police responded to a burglary at Turing’s home and eventually learned of his sexual relationship with a young man named Arnold Murray, who told Turing he knew the identity of the burglar.

Homosexuality being illegal at the time, Turing and Murray were both charged with “gross indecency,” to which Turing pleaded guilty. Rather than lose his Manchester job by serving jail time, Turing agreed to undergo chemical castration—taking estrogen injections to curb his libido, which eventually rendered him impotent.

However, Turing still lost his security clearances and could no longer continue his code-breaking work with the government. Now a security risk, he was also harassed by police surveillance.

Turing was found dead in his bed, with a partially eaten apple next to him, on June 8, 1954, by his cleaner. He died by cyanide poisoning the day before and the coroner deemed his death suicide, the cyanide believed to have been injected into the apple.

However, the apple was never tested—a 2012 BBC article argues that the case for suicide is unsupported and Turing may have accidentally inhaled cyanide during a chemistry experiment, as Turing’s mother claimed.

Pardoned, Recognized and Honored

In 2013, Alan Turing received a posthumous royal pardon from Queen Elizabeth II for his gross indecency conviction. A few years later, the British government announced “Turing’s Law,” a posthumous pardon of thousands more who suffered the same conviction.

In 2014, Actor Benedict Cumberbatch played Alan Turing in an historical drama film of the mathematician’s life, The Imitation Game . In 2021, Turing became the face of the new 50-pound bank note, which went into circulation on his birthday.

Alan Turing — A Short Biography, by Andrew Hodges . Alan Turing: Creator of modern computing. BBC Teach . Alan Turing. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Alan Turing, by Jacob Aron, New Scientist . Remembering Alan Turing: from codebreaking to AI, Turing made the world what it is today, by Liat Clark and Ian Steadman, Wired . New AI may pass the famed Turing Test. This is the man who created it, by Erin Blakemore, National Geographic . Alan Turing: The codebreaker who saved 'millions of lives,' by Prof Jack Copeland, BBC . Alan Turing: The experiment that shaped artificial intelligence, by Prof Noel Sharkey, BBC . Overlooked No More: Alan Turing, Condemned Code Breaker and Computer Visionary, by Alan Cowell, New York Times . What was Alan Turing really like? by Vincent Dowd, BBC . Alan Turing: Inquest's suicide verdict 'not supportable,' by Roland Pease, BBC . Royal pardon for codebreaker Alan Turing. BBC . New U.K. Currency Honors Alan Turing, Pioneering Computer Scientist And Code-Breaker," by Rachel Treisman, NPR .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

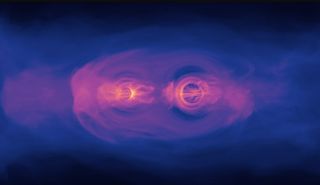

Could these black hole 'morsels' finally prove Stephen Hawking's famous theory?

Stephen Hawking suggested nothing lasts forever, including black holes. Scientists may have a way to prove it at last.

One of the most profound messages Stephen Hawking left humanity with is that nothing lasts forever — and, at last, scientists could be ready to prove it.

This idea was conveyed by what was arguably Hawking's most important work: the hypothesis that black holes "leak" thermal radiation, evaporating in the process and ending their existence with a final explosion. This radiation would eventually come to be known as " Hawking radiation " after the great scientist. To this day, however, it's a concept that remains undetected and purely hypothetical. But now, some scientists think they may have found a way to finally change that; perhaps we'll soon be on our way toward cementing Hawking radiation as fact.

The team suggests that, when larger black holes catastrophically collide and merge, tiny and hot "morsel" black holes may be launched into space — and that could be the key.

Importantly, Hawking had said that the smaller the black hole is, the faster it would leak Hawking radiation. So, supermassive black holes with masses millions or billions of time that of the sun would theoretically take longer than the predicted lifetime of the cosmos to fully "leak." In other words, how would we even detect such immensely long-term leakage? Well, maybe we can't — but when it comes to these asteroid-mass black hole morsels, dubbed "Bocconcini di Buchi Neri" in Italian, we may be in luck.

Tiny black holes like these could evaporate and explode on a time scale that is indeed observable to humans. Plus, the end of these black holes' lifetimes should be marked by a characteristic signal, the team says, that indicates their deflation and death via the leaking of Hawking radiation.

Related: If the Big Bang created miniature black holes, where are they?

"Hawking predicted that black holes evaporate by emitting particles," Francesco Sannino , a scientist behind this proposal and a theoretical physicist at the University of Southern Denmark, told Space.com. "We set out to study this and the observational impact of the production of many black hole morsels, or 'Bocconcini di Buchi Neri,' that we imagined forming during a catastrophic event such as the merger of two astrophysical black holes."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Morsel black holes can't keep their cool

The origin of Hawking radiation dates back to a 1974 letter written by Stephen Hawking called "Black hole explosions?" that was published in Nature. The letter came about when Hawking considered the implications of quantum physics on the formalism of black holes, phenomena that arise from Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity . This was interesting because quantum theory and general relativity are two theories that notoriously resist unification, even today.

Hawking radiation has remained troubling and undetected for 50 years now for two possible reasons — first of all, most black holes might not emit this thermal radiation at all, and second, if they do, it may not be detectable. Plus, in general, black holes are very strange objects to begin with and therefore complex to study.

"What is mind-bending is that black holes have temperatures that are inversely proportional to their masses. This means the more massive they are, the colder they are, and the less massive they are, the hotter they are," Sannino said.

Even in the emptiest regions of space, you'll find temperatures of around minus 454 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 270 degrees Celsius). That's because of a uniform field of radiation left over from just after the Big Bang, called the "cosmic microwave background" or "CMB." This field if often called a "cosmic fossil," too, because of how utterly old it is. Furthermore, according to the second law of thermodynamics , heat should be unable to flow from a colder body to a hotter body.

" Black holes heavier than a few solar masses are stable because they are colder than the CMB," Sannino said. "Therefore, only smaller black holes are expected to emit Hawking radiation that could potentially be observed."

Research author Giacomo Cacciapaglia of the French National Centre for Scientific Research told Space.com that, because the vast majority of black holes in today's universe are of astrophysical origin, with masses exceeding a few times that of the sun, they cannot emit observable Hawking radiation.

"Only black holes lighter than the moon can emit Hawking radiation. We propose that this type of black hole may be produced and ejected during a black hole merger and start radiating right after its production," Cacciapaglia added. "Black hole morsels would produced in large numbers in the vicinity of a black hole merger."

However, these black holes are too small to create effects that allow them to be imaged directly, like the Event Horizon Telescope has been doing for supermassive black holes by focusing on the glowing material that surrounds t hem.

The team suggests there is a unique signature that could be used to indicate the existence of these morsel black holes. This would come in the form of a powerful blast of high-energy radiation called a gamma-ray burst occurring in the same region of the sky where a black hole merger has been detected.

The researchers said these Bocconcini di Buchi Neri black holes would radiate Hawking radiation faster and faster as they lose mass, hastening their explosive demises. Those possessing masses of around 20,000 tons would take an estimated 16 years to evaporate, while examples of morsel black holes with masses of at least 100,000 kilotons would potentially last as long as hundreds of years.

The morsels' evaporation and destruction would produce photons exceeding the trillion electron volts (TeV) energy range. To get an idea of how energetic that is, Sannino said that CERN's Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Europe, the largest particle accelerator on the planet, collides protons head-on with a total energy of 13.6 TeV.

— Black hole-like 'gravastars' could be stacked like Russian tea dolls

— 2nd image of 1st black hole ever pictured confirms Einstein's general relativity (photo)

— Our neighboring galaxy's supermassive black hole would probably be a polite dinner guest

The researchers do have an idea of how to detect these morsel black holes as they evaporate, however. First, black hole mergers could be detected via the emission of gravitational waves , which are tiny ripples in spacetime predicted by Einstein, emitted as the objects collide.

Astronomers could then follow up on those mergers with gamma-ray telescopes, such as the High-Altitude Water Cherenkov gamma-ray Observatory, which can spot photons with energies between 100 Gigaelectron volts (GeV) and 100 TeV.

The team acknowledges there is a long way to go before the existence of morsel black holes can be confirmed, and therefore a long way to go before we can validate Hawking radiation once and for all.

"As this is a new idea, there is a lot of work to do. We plan to better model the Hawking radiation emission at high energies beyond the TeV scale, where our knowledge of particle physics becomes less certain, and this will involve experimental collaborations in searching for these unique signatures within their dataset," Cacciapaglia concluded. "On a longer timeline, we plan to investigate in detail the production of morsels during catastrophic astrophysical events like black hole mergers."

The team's research is available as a pre-print paper on the repository arXiv .

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

Elusive medium-size black holes may form in dense 'birthing nests'

If the Big Bang created miniature black holes, where are they?

NASA will give a Hubble Telescope status update on June 4. Should we be worried?

- danR A brief morsel on the mechanism of the nano-BH production among the 20-odd paragraphs might have been helpful. One shouldn't have to go to the paper; it would be one of the more salient topics for this article. That said, the paper leaves me with the vague apprehension that the authors are papering over a theoretical crack with their proposed morsels. Eg: "...one can still envision that, under certain strong non-linearity in the gravitational field within general relativity or beyond, small BHs may form." "As we remain agnostic about the details of the BH morsel production, we assume the existence of a distribution of masses that escapes the merger." So OK; we'll just bung along with the math and hope it all works out.. Reply

- NickOfTime To suggest that the referenced "morsels" PROVE Hawkings theory is obviously wrong. After all, Black Holes are supposed to be the one thing that doesn't "leak", so to find alleged evidence that a dense, dark object is leaking is NOT even uniquely supporting of the leaking is from black holes. QED. As a further note, which most/all will dismiss without thought, is that the existence of Black Holes, as formally defined with event horizon and singularity (if massive enough), have yet to be PROVED. Yes, large, dense DARK objects have been "observed", but not their alleged singularity which is a defining element. In addition, physicists such as Stephen Crothers and others have shown how the derivation from GR of a Black Hole with singularity is rather obviously flawed. Crothers and others were rewarded by being fired for pointing out flaws in currently accepted theory. Crothers was actually doing GR a favor because if the derivation was accurate, it would have shown that GR was fundamentally flawed. Incidentally, GR's field equations are fine (but not necessarily all interpretations of them), however, some SR flaws and the flawed Equivalence Principle were added to broaden the scope of GR. GPS data has shown light on these flaws, for example, the SR time dilation equation will only give the correct result if one measures velocity with respect to the single preferred frame (in the vicinity of the earth), namely the ECI frame, as noted by THE expert on GPS data, the late great Ron Hatch, and others within GPS and GPS consultants such as Tom van Flandern. Reply

- Unclear Engineer I don't think that black hole requires a singularity at its center. All it requires is enough mass to create a gravitational escape velocity at a radius which is larger than the radius of the physical matter of that mass. A big enough, diffuse cloud of gas could do it, without that gas needing to collapse into a singularity, or even condense. It is not clear that a black hole slightly more massive than a naked neutron star has anything in it other than a neutron star that we can no longer see. Reply

- View All 3 Comments

Most Popular

- 2 SpaceX targeting June 6 for next launch of Starship megarocket (photos)

- 3 India launches nation's 1st 3D-printed rocket engine

- 4 Space shuttle fliers David Hilmers, Marsha Ivins enter Astronaut Hall of Fame

- 5 See a Russian inspector satellite get up close and personal with a spacecraft in orbit

There’s More to Barbie Creator Ruth Handler’s Story than Barbie Shares

Barbie creator Ruth Handler had a surprising inspiration for the iconic Mattel Inc. doll.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

But, surprisingly, the character that inspired Mattel Inc. cofounder Ruth Handler, who’s played by Rhea Perlman in the film, to create Barbie wasn’t meant for kids at all. The doll’s origins stem from comic strips in post–World War II era Germany featuring a risqué character named Bild Lilli. The irreverent and sexually suggestive Lilli inspired a novelty doll for European men, which ultimately caught the eye of Handler and led to Barbie’s creation.

Here’s everything you need to know about Handler, her inspirations, and how she created the Barbie empire.

Handler’s Big Idea

Ruth—born Ruth Mosko on November 4, 1916, in Denver—moved to California at age 19 and married her high school sweetheart, Elliot Handler, in 1938. Their partnership marked the beginning of a toy empire.

After the two launched a successful giftware business from their garage in Los Angeles—making bowls, mirrors, and other household items out of plastic—the Handlers officially co-founded Mattel Creations in 1945 along with industrial engineer Harold Mattson. According to The Los Angeles Times , the company’s early toy successes included a child-size ukulele called the Uke-A-Doodle and a cap gun called the Burp Gun, which it advertised on television.

Looking for another big seller, Elliot focused on developing a talking doll for children, which evolved into Chatty Cathy. But Ruth had a different idea altogether. Seeing her daughter Barbara’s fascination with paper dolls of career women, she wished to create a lifelike, anatomically correct adult doll that would allow young girls to “dream dreams of the future.”

However, male colleagues dismissed the concept, saying it would be too difficult to manufacture and that no mother would buy such a doll for her child. “They were all horrified by the thought… of wanting to make a doll with breasts,” Handler said in M.G. Lord’s 1994 book Forever Barbie: The Unauthorized Biography of a Real Doll .

Although she temporarily cast the project aside, a 1956 vacation to Switzerland would show Handler her idea had potential.

Finding Inspiration in Bild Lilli

While on the trip, Handler and a teenaged Barbara came across a Bild Lilli novelty doll on display.

Created by Reinhard Beuthien, the Lilli character debuted in the comics of German newspaper Bild-Zeitung in 1952. She was portrayed as a “golddigger, exhibitionist, and floozy” according to Lord, and often appeared scantily clad.

Lilli quickly became popular and was turned into a plastic doll—a novelty toy given to men as a gag gift. Lord explained in her book that men would hang the doll off the rearview mirror of their cars and take Lilli to bars, pulling down her pants or lifting up her skirt as a source of humor. At just under a foot tall, Lilli also had an exaggerated physique featuring a disproportionately large bust, blue eye shadow, and a distinctive blonde ponytail. “She was a pornographic caricature,” Lord told The Washington Post .

But Handler saw a source of inspiration for her own doll and quickly amassed a collection of almost two dozen of the European toys upon her return to California. Barbara kept one Lilli in her room, while her mother took the rest to Mattel for a makeover. The company not only changed the doll’s physical characteristics—upgrading her plastic and making alterations to her lips and eyebrows—but also her personality, turning Lilli from a sex object into the fashion-crazed girl next door we all know today.

Barbara Millicent Roberts, named after Handler’s daughter and shortened to Barbie, debuted at the American International Toy Fair in New York in 1959. Her male counterpart—Kenneth Sean Carson, or simply “Ken”— appeared two years later and was named after the Handlers’ son.

And the Rest Is History, Right?

Not quite. Barbie quickly became popular, with 300,000 dolls sold in just the first year of production, but Mattel soon faced a legal challenge from Bild Lilli’s manufacturer.

German toymaker Greiner & Hausser sued Mattel in 1961, alleging infringement of its patent for the “doll hip joint” used on the Lilli doll. According to The Los Angeles Times , the two sides settled out of court in 1963, and Mattel purchased the German company’s copyright and patent rights in 1964. Decades later, in 2001, the court-appointed liquidator for then-bankrupt Greiner & Hausse sued Mattel in Germany and sought royalties for every Barbie doll sold after their sale agreement. However, the case was eventually dismissed.

Get the latest from Biography.com delivered straight to your inbox .

Additionally, a former designer at Mattel, Jack Ryan, sued the company in 1980 after claiming he, not Handler, actually created Barbie and named the doll after his wife. Mattel settled, and Ryan later died by suicide in 1991 following a stroke.

Despite all these setbacks, Mattel’s flagship product has flourished with well over 1 billion dolls sold. By 1966, Mattel controlled 12 percent of the $2 billion toy market in the United States, according to The Los Angeles Times . However, Handler’s position within the company wouldn’t last.

Leaving Mattel and Handler’s Next Act

Handler served as Mattel president until her resignation in 1973. New managers began to diversify the brand beyond toys soon after, and she and Elliot were out of the company altogether by 1975.

Handler’s health had presented challenges, as she underwent a mastectomy for breast cancer in 1970. With discussion around the disease still limited at that time, she admitted years later the diagnosis left her unfocused and contributed to her exit from Mattel. Additionally, Handler was indicted on charges of fraud and false reporting to the Securities and Exchange Commission in 1978, pleading no contest. She was sentenced to 2,500 hours of community service and a $57,000 fine.

Still, Handler sought to be a force for good up until her death from colon surgery complications at age 85 in April 2002. She founded Ruthton Corp. in 1976 and, inspired by her own cancer recovery process, created and manufactured the Nearly Me prosthetic breast to help other survivors of the disease. She made talk show appearances and crafted handwritten invitations to market the product, and her sales team trained department store workers to fit patients for the prosthetic. Former First Lady Betty Ford , who also underwent a mastectomy, was even fit for a Nearly Me.

Even after selling the company in 1991, Handler continued to educate women about the importance of screenings for early detection of breast cancer. “I didn’t make a lot of money in it,” she said of her post-Mattel venture. “It sure rebuilt my self-esteem, and I think I rebuilt the self-esteem of others.”

See Barbie in Theaters Now

Barbie ( Margot Robbie ) and Ken ( Ryan Gosling ) leave Barbie Land and venture into the human world for the first time in Barbie , directed by Greta Gerwig .

Tyler Piccotti first joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor in February 2023, and before that worked almost eight years as a newspaper reporter and copy editor. He is a graduate of Syracuse University. When he's not writing and researching his next story, you can find him at the nearest amusement park, catching the latest movie, or cheering on his favorite sports teams.

Entrepreneurs

The True Story of Pop-Tarts and ‘Unfrosted’

The Life and Hip-Hop Legacy of DJ Mister Cee

The Truth About Walt Disney’s Frozen Head

Frederick Jones

Lonnie Johnson

Oprah Winfrey

Madam C.J. Walker

Enzo Ferrari

The Tragic True Story of the ‘Ferrari’ Movie

Suge Knight

Jimmy Buffett

Could the world famous Roman Baths help scientists counter the challenge of antibiotic resistance?

The world-famous Roman Baths are home to a diverse range of microorganisms which could be critical in the global fight against antimicrobial resistance, a new study suggests.

The research, published in the journal The Microbe , is the first to provide a detailed examination of the bacterial and archaeal communities found within the waters of the popular tourist attraction in the city of Bath (UK).

Scientists collected samples of water, sediment and biofilm from locations within the Roman Baths complex including the King's Spring (where the waters reach around 45°C) and the Great Bath, where the temperatures are closer to 30°C.

The samples were then analysed using cutting edge sequencing technology and traditional culturing techniques were employed to isolate bacteria with antibiotic activity.

Around 300 distinct types of bacteria were isolated across the Roman Baths site -- among them the key candidate groups, Actinobacteria and Myxococcota , known for antibiotic production -- with different examples being more prominent within the varying water temperatures.

Further tests showed 15 of these isolates -- including examples of Proteobacteria and Firmicutes -- showed varying levels of inhibition against human pathogens including E.coli, Staphylococcus Aureus and Shigella flexneri.

The research comes at a time when the need for new sources of antibiotics is at unprecedented levels, with resistance of bacteria to currently used medication estimated to be responsible for more than 1.25million deaths globally each year.

Writing in the study, scientists say a significant amount of additional investigation is required before the microorganisms found in the Roman Baths can be applied in the fight against disease and infection globally.

However, they add that this initial study has shown there is clear potential for novel natural products contained within its hot springs to be explored further for that purpose.