Research Committees

- First Online: 01 January 2024

Cite this chapter

- Robert S. Fleming 2

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

135 Accesses

Many graduate programs require that their students complete a significant research project in their field of study. While these requirements differ between programs and institutions, they frequently involve the successful preparation and completion of a comprehensive research project as well as submitting and defending an appropriate master’s thesis or doctoral dissertation as the culminating requirement of one’s academic program. Variations may exist between the curriculum requirements and expectations of different programs and institutions. It is also important to be aware that the research expectations and deliverables of particular programs and institutions will often also differ by country. Understanding the specifics of each program is an important responsibility of both students completing these requirements and faculty members that supervise and guide their research activities in completing program and degree requirements.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Rohrer College of Business, Rowan University, Glassboro, NJ, USA

Robert S. Fleming

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Fleming, R.S. (2023). Research Committees. In: Preparing for a Successful Faculty Career. Springer Texts in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-50161-6_29

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-50161-6_29

Published : 01 January 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-50160-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-50161-6

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Global navigation

- Site navigation

School of Education Graduate Bulletin 2012-2014

- IU Bulletins

- IU

Degree Programs

- Certificate Programs

- Licensure Programs

- Policies & Procedures

- Master of Science in Education Degree

- Adult Education

- Art Education

- Counseling and Counselor Education

- Educational Leadership

- Elementary and Early Childhood Education

- Higher Education and Student Affairs

- History and Philosophy of Education

- Instructional Systems Technology

- International and Comparative Education

- Literacy, Culture, and Language Education

- Learning and Developmental Sciences

- Secondary Education

- Social Studies Education

- Special Education

- Master of Arts in Teaching (M.A.T.)

- Specialist in Education Degree

Doctoral Degrees in Education

- Getting Started In Your Doctoral Program

- Guidelines For Maintaining Doctoral Progress

Forming Your Research Committee

- Completing Your Doctoral Program

- Online Programs

After admission to candidacy, the student must assemble a research committee. The doctoral research committee has the responsibility to guide the student through the dissertation process and to conduct the final oral defense.

Ph.D.: Each research committee must have at least four members. Two must be from the student's major area of study and one from the minor. For an interdepartmental minor, the minor member must be from outside the major area. If the minor is not pertinent to the topic of the dissertation, the student may petition to substitute another member from outside the major area. The committee chair must be a faculty member in the student's major area. Usually, the committee chair is also the dissertation director. However, it is acceptable for another committee member with particular expertise in the area of study to direct the dissertation. The Nomination of Research Committee, an electronic form, is available in OneStart. All members of Ph.D. research committees must be members of the University Graduate School faculty.

The committee chair and the dissertation director must be endorsed members of the University Graduate School faculty. If a regular member of the University Graduate School faculty has special expertise in the area of the student's research, the research committee chair and the associate dean for graduate studies may petition the University Graduate School to allow the regular faculty member to direct the student's dissertation.

Ed.D.: For 90 credit hour and 60 credit hour Ed.D. programs, research committees must have at least three members. Two of these must be from the major field of study, of which one must be a tenure-line faculty from the core campus. The third member cannot be from the major field of study. One member may be from the faculty of a campus of Indiana University outside the core campus. At least two of the committee members must be tenure-line faculty members. The committee chair must be an associate or full professor in the student's major area of study. The dissertation director must be a regular or endorsed member of the University Graduate School faculty.

In some instances it is possible to include a committee member who is not an Indiana University faculty member, such as a faculty member at another university, on a doctoral committee. To receive approval for such an addition, two conditions must be met:

- the substitute member must have special expertise not available among University Graduate School faculty, either in the substantive area of the study or in the research methodology, and

- the substitute member must supply evidence of published research.

A copy of the Human Subjects Committee approval must be submitted with the Research Committee form. For further information on the Human Subjects approval process, please see the section titled "Use of Human Subjects" below.

Forming a Committee

The procedure for selecting a research committee chair and research committee members varies considerably from student to student. Ideally, the research question that becomes the focus of the dissertation study stems naturally from research experiences, course work, or graduate assistantship assignments that the student has had during the program of studies. Often the advisory committee chair is the student's mentor and becomes the research committee chair. In such a case, the student and chair typically have had discussions about tentative dissertation topics prior to admission to candidacy and prior to the selection of other research committee members.

It is not required that the advisory committee chair be asked to chair the research committee, nor that the advisory committee chair agree to chair the research committee, if asked. Ultimately, the choice of a research chair involves a combination of personal compatibility and compatibility of the research interests of the student and the chair. The student and the committee chair typically confer regarding the selection of other research committee members.

Prospectus/Summary

A one- to two-page dissertation prospectus/ summary must be submitted with the Nomination of Research Committee form. This prospectus/summary should include a clear statement of the questions to be addressed in the study, an outline of the design of the study, the research methods to be used, and a discussion of the contribution of the study to theory and/or to practice. The prospectus/ summary should play an important role in the selection of a research committee. This document allows prospective members to decide whether to participate in the study, based on the area of focus and the integrity of the prospectus. It is generally unwise for faculty members to make a commitment to serve on a student's research committee before a written prospectus/summary is presented for examination.

Dissertation Proposal

After submitting the prospectus/summary, students are next required to submit a dissertation proposal, a document that is considerably more detailed than the prospectus/ summary. The proposal should contain the following elements: a statement of purpose, rationale, literature review, research questions, proposed procedures, the source of data, methods of data collection, methods of data analysis or data reduction, and the contribution of the study to theory and/or to practice. Frequently, students are advised by their research committee to write a draft of the first three chapters of the dissertation (purpose and rationale, literature review, and method) as their research proposal.

A meeting of the research committee must be held to discuss and approve the dissertation proposal. A dissertation proposal approval form is available in the Office of Graduate Studies. When committee approval has been secured, the form must be filed with the Office of Graduate Studies. If the proposed research has changed since submission of the Nomination of Research Committee form, then a new two-page summary must be attached to the Dissertation Proposal Form.

Use of Human Subjects

If the proposed research involves the use of human subjects, a research review form for the use of human subjects must be completed. This form must be approved by the Campus Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects before the data collection begins. Prior to applying for human subjects approval and before the research review form for the use of human subjects can be reviewed, students will need to document that they have been trained to involve humans in research by passing the IU test for using humans in research. The tutorial and test can be found at http://researchadmin.iu.edu/HumanSubjects/index.html . Proof of having passed the test must accompany the application at the time of submission. Failure to provide proof with the application will delay the review until the following month. This applies to all submissions (new, continuation, and/or amendment) regardless of funding or rank of the primary investigator, sponsor, and co-investigators.

If the proposed research does not involve the use of human subjects, the School of Education requiries verification from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) that their oversight is not required.

The Human Subjects Committee office is located at the Carmichael Center 103, 530 E. Kirkwood Avenue, Bloomington, IN 47408, (812) 855-3067, [email protected]. Office hours are 8 a.m. to noon and 1 to 5 p.m., Monday-Friday.

In Indianapolis, students should contact the Office of Research Risk Administration at (317) 274-8289. The research review form for the use of human subjects can be viewed and downloaded from the Web at http://researchadmin.iu.edu/HumanSubjects/index.html.

Academic Bulletins

- Indiana University

PDF Version

Contact information for:

- School of Education

- Program Coordinators

Additional program information can be found at the Office of Graduate Studies .

Copyright © 2024 The Trustees of Indiana University , Copyright Complaints

Create an Account

Research Committee

The Research Committee shall be responsible for fostering research in neuroradiology, for overseeing researchers and research activities funded by or through the Society. As directed by the Advisory Council, the Research Committee shall be responsible for supervising and judging the application or competition for grants and prizes bestowed by the Society that are research related. The Research Committee shall recommend recipients to the Foundation Board of Trustees, which must approve all grants and monitor the progress of funded individuals or proposals as appropriate.

- Support collaboration amongst basic science (Ph.D scientists) and clinical research (MD scientists) in the Society for educational and research opportunities.

- Develop a strategy for increasing NIH funding for neuroradiology-oriented projects.

- Provide educational and other support activities to encourage research by ASNR members.

- Develop initiatives to enhance the value of the Annual Meeting for neuroimaging investigators, and attract their participation

- Develop a strategy that encourages good quality submissions to the AJNR and to the Foundation-sponsored grants.

- Revise Foundation grant guidelines to enhance greater participation in the wide range of experience of ASNR members.

- Make recommendations to the Foundation regarding the support of research, including specific projects, through Foundation funding of the ASNR.

- Maintain documentation on all current and former funded projects through the Foundation.

- Update and maintain the Research Committee website, such that it is a useful tool for Society members seeking information regarding neuroradiology research.

- Fosters relationships with external organizations in order to advise, recommend, and support clinical trials that assess neuroradiology techniques or procedures.

- Foster collaboration with other organizations involved in Neuroimaging research, including the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA), International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM), Organization for Human Brain Mapping (OHBM), and the Society for Neurosciences (SfN).

- Foster health services research in neuroradiology by collaborating with the Committee for Evidence Based Medicine.).

- To maintain contact with NIH agencies which support neuroradiological research, so as to influence submissions of RFAs and RFPs.

Time Commitment

The committee shall hold conference calls as needed.

Committee Roster

Click here to view ASNR Committee Rosters

American Society of Neuroradiology proudly includes:

Research organisations and research ethics committees - ESRC

Our principles: research ethics committees.

All parties involved in research have an active role to play in creating and sustaining a culture of rigorous ethical reflection.

We acknowledge that RECs have many competing obligations, with duties to protect participants, researchers and research organisations which mean they are constantly working to achieve many goals; we encourage RECs to engage with researchers in all stages of a project’s research lifecycle.

The principles below should also be considered during any ongoing monitoring of ESRC-funded projects.

Research should aim to maximise benefit for individuals and society and minimise risk and harm

A REC review of a project should consider the ethical conduct of the research whilst also facilitating high quality ethical research; this includes high-impact activities and new forms of research, for example, co-production. The review should be proportionate to the potential benefits and level of risk of the proposed research. RECs should determine the degree of risk and potential harm that may be tolerable in relation to the potential benefits.

The rights and dignity of individuals and groups should be respected

The primary role of the REC review is to ensure that the research will respect the dignity, rights, welfare and, where possible, the autonomy of participants and all parties involved in and potentially affected by the research.

Wherever possible, participation should be voluntary and appropriately informed

The REC should consider the information provided by the researchers regarding consent and voluntary participation, and evaluate how researchers justify and mitigate risks associated with withholding information and the adequacy of any proposed debriefing.

Participants should, wherever possible, take part in research voluntarily and there should not be any coercion or inappropriate influence.

The REC should be confident that participants will be given sufficient information about the research to enable them to make an informed decision about their participation. REC members should also be aware that there may be instances where this is not practical or desirable (for example, for methodological reasons, or covert or crowd research).

Research should be conducted with integrity and transparency

RECs should ensure that they fulfil their role and responsibilities with integrity and record their decisions and feedback in a transparent way.

Lines of responsibility and accountability should be clearly defined

The remit and responsibilities of the RECs should be clear; RECs should be committed to training and development to enable them to fulfil their role. Where the REC feels that it does not have the expertise to review a proposal, it should seek the help of independent bodies or external members. The REC’s performance is subject to review by the research organisation.

The independence of research should be maintained, and where conflicts of interest cannot be avoided they should be made explicit

RECs should be able to conduct ethics review in a wholly independent and impartial manner without any conflicts of interest and with a focus clearly on the ethics of research proposals.

Independence can be achieved by a committee composed of members from a wide range of disciplines and includes external members, within a policy and governance structure that establishes the right of the REC to pass opinions free of influence.

Secondary RECs that comprise members from only one discipline or a small number of closely related disciplines may be regarded as too closely aligned with the interests of researchers.

Further information

Criteria for research ethics committee review

Conflicts of interest, complaints and appeals

Last updated: 15 October 2021

This is the website for UKRI: our seven research councils, Research England and Innovate UK. Let us know if you have feedback or would like to help improve our online products and services .

- Subscribe to our Newsletter

popular searches

The Concordat to Support Research Integrity

Upcoming Webinar Series

Publications

Annual Conference

Research Ethics Support and Review

Code of Practice for Research

Checklist for Researchers

Checklist during COVID-19

Case Study Packs

Researcher Checklist of Ethics Applications

Concordat Self-Assessment Tool

What is a Research Ethics Committee?

- Newsletter issues

Research ethics committees (RECs) are an important part of a healthy research culture. Their role is to consider the ethical implications of research. Traditionally this has focussed on the need to protect research participants (both human and animal), but in recent years their role in supporting researchers, and promoting research integrity more generally, has been increasingly recognised.

Two types of RECs

It is important to distinguish two types of research ethics committees. The first type is often set up to consider ethical issues that may be relevant to researchers working in specific areas. These might include the ethics of research into genetic modification, climate engineering, dual-use research (e.g., research with military applications), or research using potentially contentious methodologies such as “ human challenge ” trials (where participants are intentionally infected with diseases such as COVID). As these are difficult and complex areas, the main output is often in the form of guidance or position statements that can be applied by researchers, their institutions, funders, and ultimately policymakers. Consequently, these committees are convened at a fairly high level by organisations with an interest in the area of research being considered. They normally include scientific and legal experts alongside those with a specific interest in the topic under consideration (such as patient groups).

But the second, and far more common, type of research ethics committee is those set up by universities, research organisations, or health care providers (such as the NHS) to consider the ethical issues relating to individual, and often very specific, research projects. These Research Ethics Committees — abbreviated as RECs and referred to as Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) in the United States — provide a point-in-time review of a very detailed research protocol before the research is allowed to start. They aim to provide an opinion as to whether the research, if carried out in accordance with the detailed protocol, will meet accepted ethical norms. Exactly what these norms are, and how they can be addressed, is a complex question that may need to take into account guidance created by the first type of ethics committee described above. As such, although RECs still need to have suitably experienced individuals, it is more important that they are also suitably independent from the researcher (and their funder) to ensure they give an ethical opinion that is free from as many conflicts of interest as possible. Scientific or research expertise is important, but so is the voice of non-expert members. Quite often researchers will not be allowed to publish their work if they cannot prove it was reviewed by a REC before it started.

REC review supports research and researchers

REC review is criticised by researchers as being too lengthy, burdensome, or bureaucratic. This is often because it is confused with wider governance processes relating to issues such as data protection, health and safety, financial management, etc. While such issues are important, the fact that they are related to specific, often legally prescribed, arrangements means that they are governance issues that are the responsibility of the research institution (e.g., the university) to review and approve. The distinction between governance approvals , and ethics opinion , is extremely important if the aim is to create systems that provide robust, but proportionate, support to research and researchers. While in some contexts committees are expected to review both governance and ethics issues, there is an increasing recognition that governance is best handled separately by expert research officers, freeing RECs to consider the more complex ethical issues that may arise in any given research project.

Written by Dr Simon Kolstoe, UKRIO Trustee .

Research Review Committee

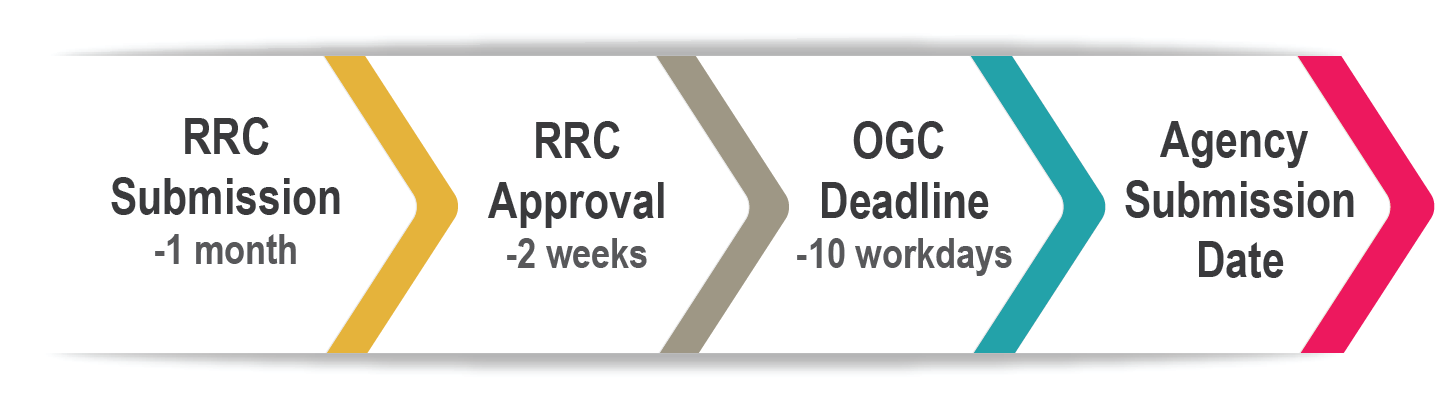

The Research Review Committee (RRC) is the Department of Psychiatry’s internal grant review committee and helps to ensure that research proposals prepared by investigators affiliated with our Department meet the highest scientific and ethical standards.

Prior to submission to external funding agencies or initiation of internally supported research, the RRC evaluates the scientific and technical merits of all research proposals planned by faculty within the Department, collaborating faculty from outside the Department, fellows, students, and staff. In addition, the RRC provides a preliminary evaluation of potential risks and benefits to human participants and of the welfare of animal subjects.

All Department faculty and postdoctoral trainees submitting grant applications (as the PI) to external funding agencies must have their proposals reviewed by the RRC (even senior faculty and the Department Chair). For faculty who want to read about our internal submission guidelines and access the RRC materials (policy, coversheet, rating forms, etc.), please visit the faculty intranet site, Psy Hub . For postdocs interested in submitting a K award, please visit the CARDS SharePoint site.

The RRC requests that investigators submit proposals for review as early as possible and that they work proactively with us throughout the process, especially when questions or special circumstances arise.

To learn more about the role of the RRC, you can read the committee’s paper in Academic Psychiatry and/or contact one of the RRC Co-Chairs below.

RRC Co-Directors

Judy L Cameron, PhD

Contact details.

Paul A Pilkonis, PhD

Rrc co-chairs.

David A Brent, MD

Brant P Hasler, PhD

Cynthia A Conklin, PhD

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Institutional Review Boards

Purpose and Challenges

Christine Grady , PhD, RN

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

CORRESPONDENCE TO: Christine Grady, PhD, RN, Department of Bioethics, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, Building 10/1C118, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Received 2015 Mar 23; Accepted 2015 Apr 30; Issue date 2015 Nov.

Institutional review boards (IRBs) or research ethics committees provide a core protection for human research participants through advance and periodic independent review of the ethical acceptability of proposals for human research. IRBs were codified in US regulation just over three decades ago and are widely required by law or regulation in jurisdictions globally. Since the inception of IRBs, the research landscape has grown and evolved, as has the system of IRB review and oversight. Evidence of inconsistencies in IRB review and in application of federal regulations has fueled dissatisfaction with the IRB system. Some complain that IRB review is time-consuming and burdensome without clear evidence of effectiveness at protecting human subjects. Multiple proposals have been offered to reform or update the current IRB system, and many alternative models are currently being tried. Current focus on centralizing and sharing reviews requires more attention and evidence. Proposed changes to the US federal regulations may bring more changes. Data and resourcefulness are needed to further develop and test review and oversight models that provide adequate and respectful protections of participant rights and welfare and that are appropriate, efficient, and adaptable for current and future research.

Institutional review boards (IRBs) or equivalent bodies provide a core protection for human participants in biomedical and behavioral research in the United States and > 80 other countries around the world. 1 IRBs are charged with providing an independent evaluation that proposed research is ethically acceptable, checking clinical investigators’ potential biases, and evaluating compliance with regulations and laws designed to protect human subjects.

Independent review of clinical research by an IRB is required for US studies funded by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and other US federal agencies, as well as for research testing interventions—such as drugs, biologics, and devices—that are under the jurisdiction of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ( Table 1 2 , 3 ). US research institutions can and often do extend federal regulatory requirements to all of their human subjects research. Research conducted outside of the United States but funded by the US government is subject to the same US federal regulations and so requires IRB review or equivalent protections. 4 Research conducted outside of the United States, not under an investigational new drug that submits data to the FDA for a new drug or biologic license application, must comply with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, which include review and approval by an independent review committee and informed consent. 5 Regulations and laws in many other jurisdictions around the world also require review by an independent research ethics committee or IRB. 6 Regulatory bodies in the European Union, Japan, United States, Canada, Australia, and Nordic countries, among others, follow Good Clinical Practice guidelines such as those delineated by the International Conference on Harmonisation, which require approval by an independent ethics committee or IRB. 7 IRBs or research ethics committees, composed of a group of people independent of the specific research, review proposed research plans and related documents before a study can begin and then periodically (usually annually) for the study duration. The goal of IRB review is to assure that the rights and welfare of participating research subjects will be adequately protected in the pursuit of the proposed research study. To be ethically acceptable and comply with regulatory requirements, the IRB determines that risks to subjects are minimized and reasonable in relation to the importance of the knowledge the study is expected to produce, that the process and outcomes of subject selection are fair (including delineated inclusion and exclusion criteria), and that there are adequate plans for obtaining informed consent.

TABLE 1 ] .

Selected US Regulatory Requirements for IRBs (Paraphrased)

| Regulation | Requirements |

| Membership (45CFR.46 107; 21CFR.56.107) | At least 5 members of varying backgrounds, both sexes, and > 1 profession |

| At least 1 scientific member, 1 nonscientific member, and 1 unaffiliated member | |

| Members sufficiently qualified through diverse experience and expertise to safeguard subjects’ rights and welfare and to evaluate research acceptability related to laws, regulations, institutional commitments, and professional standards | |

| At least 1 member knowledgeable about any regularly researched vulnerable groups | |

| Members report and recusal for conflicts of interest | |

| Ad hoc experts as needed | |

| Functions/operations (45CFR.46 108; 21CFR.56.108) | Follow written procedures for initial and continuing review and for any changes and amendments |

| Written procedures for reporting unanticipated problems, risks, and noncompliance | |

| Quorum of majority at convened meetings. Approval requires majority vote | |

| Review (45CFR.46 109; 21CFR.56.109) | Authority to approve, require modifications of, or disapprove research |

| Require informed consent and documentation (or approve a waiver ) | |

| Notify investigators in writing | |

| At least annual continuing review | |

| Criteria for approval (45CFR.46 111; 21CFR.56.111) | IRB should determine that risks are minimized; risks are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, if any, and the importance of the expected knowledge; subject selection is equitable and attention to vulnerable populations; informed consent will be sought and documented; adequate provisions for monitoring; adequate provisions to protect confidentiality; additional safeguards for subjects vulnerable to coercion or undue influence |

| Authority (45CFR.46. 113; 21CFR.56.113) | Institutional officials cannot approve research that is disapproved by the IRB (45CFR.46 only) |

| The IRB can suspend or terminate research for serious harm or noncompliance | |

| Records (45CFR.46. 115, 21CFR.56.115) | Records of research proposals, meetings, actions, correspondence, members, and so forth |

CFR = Code of Federal Regulations; IRB = institutional review board.

History of IRBs in the United States

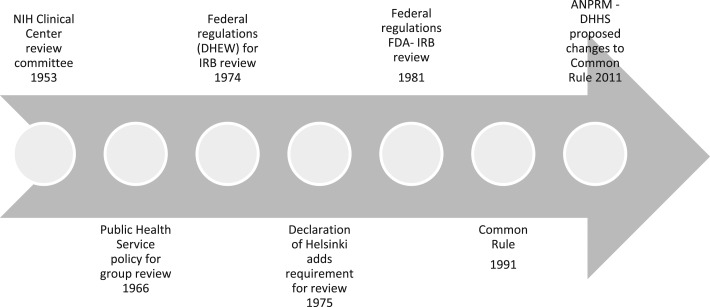

Recognizing that review by impartial others might mitigate conflicting differences in the ethical responsibilities of physician-investigators to research subjects from those of physicians to their patients and, thus, help to protect the rights and welfare of research subjects, James Shannon, MD, Director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), in 1965 proposed that all NIH research involving human subjects be evaluated by an impartial panel of peers to ensure its ethical integrity. His idea derived, at least in part, from a model that began at the NIH Clinical Center when it opened in 1953, which was a model of group peer review for research involving healthy volunteers. 1 In 1966, US Public Health Service policy requirements for ethical review, which were expanded to all Department of Health Education and Welfare (the DHHS predecessor) research by 1971, were not well enforced. 1 Regulations for the protection of human subjects for DHHS, published in 1974 (45CFR.46), included a requirement for group ethics review and the term “institutional review board” was introduced. The World Medical Association also introduced review by an independent committee for oversight of science and ethics into the 1975 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki. 8 The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, established by the US Congress after revelations of the US Public Health Service syphilis studies at Tuskegee, authored the Belmont Report which explicated ethical principles underlying the conduct of human subjects research. 9 The Commission’s contributions, including integration of the Belmont principles, were incorporated into updated US regulations in 1981. The 1981 DHHS regulations were subsequently adopted by 16 federal agencies (not including the FDA) in 1991 as the Common Rule. The FDA required an IRB beginning in 1981 (Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations, part 56), although some investigators funded by pharmaceutical companies already used oversight committees. 10 The most extensive proposed changes to the Common Rule since 1991 were issued by the DHHS in an Advance Notice of Proposed Rule Making in 2011 in an effort to enhance protections and efficiency. 11 , 12 Public comments were solicited and a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking is under development, but as of this writing has not been published ( Fig 1 ).

Timeline of regulations and guidance regarding IRB review. ANPRM = Advance Notice of Proposed Rule Making; DHEW = US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; DHHS = Department of Health and Human Services; FDA = US Food and Drug Administration; IRB = institutional review board; NIH = National Institutes of Health.

US regulations at 45CFR.46 subpart E and 21CFR.56.106 require IRBs to be registered with the DHHS Office of Human Research Protections (OHRP), which is responsible for monitoring compliance with the Common Rule. Research institutions that receive DHHS funds file with OHRP an assurance that the institution will comply with federal regulations, called a Federal Wide Assurance. 13 Each assurance has to include at least one internal or external IRB registered with OHRP. The FDA requires registration of IRBs but does not require prospective assurances of compliance; sponsors and investigators include evidence of IRB review when they submit data to the FDA.

Changes to Research

At the time that IRBs were codified in regulation, single-site clinical research was the predominant paradigm. Advances in knowledge, technology, and resources over the subsequent decades have significantly changed the face of research. Growth in public and private spending 14 , 15 as well as evolving scientific opportunities have created novel challenges for IRBs. The majority of clinical trials are now multisite, and some include > 100 sites, often with sites in multiple countries. 16 In addition to multicenter and multinational research, IRBs review, for example, proposals for research with stored samples and data, cell-based and stem cell therapies, emergency research, social science research, and community-based research. IRBs operate under the same regulatory structure and use similar procedures despite a wide range of types of research posing disparate risks to subjects’ rights and welfare. Furthermore, the complexity of oversight has changed with the development of new entities involved in clinical research, such as contract research organizations, data and safety monitoring committees, clinical trial coordinating centers, accrediting associations, and commercial IRBs, among others.

Changes to IRBs

Concurrently, the number of, investment in, and responsibilities of IRBs have continued to increase. Most research institutions, universities, and health-care facilities have at least one IRB, and the majority has more than one. 17 In addition, there are a number of independent or commercial IRBs. 18 Increasingly, IRBs are tasked with responsibilities beyond those required by federal regulation, including, for example, review of conflicts of interest, compliance with privacy regulations, training of investigators, scientific review, and monitoring of clinical trial registration, among others. IRBs do indeed have responsibility for reviewing the science to assess the soundness of the design and the risks and benefits of the proposed research, however, many institutions have a separate scientific review process that precedes and complements IRB review.

Dissatisfaction and concern about what is perceived as an expansive mission and bureaucracy of IRBs has also mounted. Investigators and others criticize the IRB system as dysfunctional and “more concerned with protecting the institution than research participants.” 19 Some claim that IRBs are overburdened 20 and overreaching. Researchers, institutions, and some IRB members complain about burden: excessive paperwork, inflexible interpretation of regulatory requirements, attention to inconsequential details, and “mission creep”—the expanding obligations of IRBs that seem to have little to do with protection of research participants. 21 Fear of regulatory admonition has fueled a focus on compliance with regulations. 22 Some perceive the excessive or “hyper” regulation as seriously affecting or stifling research productivity and adding cost without adding meaningful protections for participants. 23 , 24 Clinical investigators complain that the IRB review process is inefficient and delays their research for what seem like minor modifications. 25 The public hears about problems and fears that research might be unsafe and existing protections ineffective or inadequate. 26 , 27

Charles McCarthy, the first director of the US Office for Protection from Research Risks (the OHRP predecessor) noted, “[IRBs] have become more insightful and sophisticated…But unless [the Human Research Protection System] is considered to be an evolving and expanding mechanism, adapting to the problems of each period of history, it is in danger of becoming fossilized and ineffective.” 28 Flexibility and adaptability are important characteristics not usually attributed to IRBs. The challenge is how to evolve, expand, and adapt IRBs to the current exigencies of research in a rational and meaningful way. As noted by Cohen and Lynch, 29 the system is “ripe for a major course correction.”

Reform: Needs, Attempts, and Challenges

Recognition of the need for a robust system of protecting human research subjects within the changing research landscape has led to various proposals for reform and suggestions for alternative models. 30 ‐ 35

Reform proposals offer changes to address some of the various factors that are problematic for IRBs and for those who use them. Yet, reform efforts have been somewhat paralyzed by the tension between those who find the current system inadequate and those who find it too overreaching. 36 , 37 Nonetheless, many grant that multiple reviews for a single study are duplicative, lead to significant delays in research without adding meaningful protections, and can result in inconsistencies that bias the science. 38 , 39 Additional reasons for considering reform of the current oversight system include inherent conflicts of interest, inadequate resources, the emergence of new research methodologies, and insufficient expertise of members, among others. 40 IRBs also grapple with how to respond to evolving research methods, and high profile cases in which regulators disagree with or disapprove of IRB decisions can fuel uncertainty and anxiety. 41 , 42

Various systems of pre-IRB review have gained traction as a way to improve IRB efficiency: Major issues and gaps can be identified and corrected through prereview before an IRB sees the proposal. Institutions are also adopting a framework that more explicitly recognizes the essential roles of the institution, investigators, and research teams in addition to IRBs in protecting human subjects. 43 Several alternatives to the traditional model of single IRB review or review at each site of a multisite study have been developed and tried ( Table 2 ). 44 ‐ 53 Proposed revisions to the Common Rule include a recommendation for a single IRB of record for domestic multisite trials. 9 More recently, the NIH called for comments on a draft proposal for a single IRB review for NIH-funded multisite trials. 54 NIH is also currently funding several empirical studies of central IRBs with the goal of informing policy development relevant to central IRBs. 55 Despite these significant efforts, many challenges remain in changing the process of IRB review, including questions of liability, cost structures, and incentives, and uncertainty about the relative merits of proposed models. 56

TABLE 2 ] .

Alternative Models for IRB Review

| Type | Explanation | Examples |

| Local IRB review | Single-site study or review at each site for single site or multisite studies | Most research institutions have ≥ 1 IRB at the site that review research conducted at that site. |

| Shared IRB review | ||

| Reliance | An institution formally “relies” on the IRB of another institution for review of a particular study or set of studies. | Increasingly ≥ 1 site partner with another IRB through a reliance agreement. See, for example NIAID, CHOP, and others. |

| Shared review | Concurrent regional or central and local review | Indian Health Service |

| Centralized review | ||

| Central IRB | Central IRB established to review all studies of a type, each site accepts the central review | National Cancer Institute’s Central IRB (2 adult, 1 pediatric, 1 cancer prevention and control) |

| American Academy of Family Physicians National Research Network IRB | ||

| Veterans Administration central IRB | ||

| A group of institutions form an alliance and create a new central IRB to serve as IRB for group. | Biomedical Research Alliance of New York (BRANY) | |

| OR | The IRB at Massachusetts General Hospital is designated as IRB of record for all NINDS-funded NeuroNext institutions. | |

| An existing IRB is designated as the central IRB for all sites of a network. | ||

| One of the existing NIH intramural IRBs is designated as the central PHERRB for public health emergencies. | ||

| Independent/commercial | A freestanding IRB (not part of an institution) is employed to review single or multiple site studies. | Western IRB, Chesapeake IRB, many others |

| Federated model | Allows sites to choose among multiple options including reliance, shared review, local review, or facilitated review. All options include a commitment to sharing IRB submissions and determinations among study sites. | National Children’s Study (NICHD) |

CHOP = Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; NIAID = National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; NICHD = National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NIH = National Institutes of Health; NINDS = National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; PHERRB = Public Health Emergency Research Review Board. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviation. (Adapted from the Alternative Models Table in “Summary of the 2006 National Conference on Alternative IRB Models: Optimizing Human Subject Protection.” 31 )

Need for Evidence

Reform proposals often recognize the need for data about what works and for creative and testable ways of achieving the appropriate combination of protecting the rights and welfare of participants with meaningful and efficient IRB review that promotes high quality, relevant, and timely research. Evidence about how well IRBs are functioning, how effective they are, and how they could be more efficient would provide useful guidance for reform efforts. 57 Existing studies describe IRB structure, process, or outcomes and show that IRB judgments are inconsistent, as is their application of a standard set of regulations. 58 , 59 Practices and decisions vary between and within IRBs often without justification, including determinations about risk level, inclusion criteria, and the appropriateness of methods of recruitment and consent. 55 , 60 Despite complaints about inconsistency, independence and local evaluation make some IRB variation inevitable. Moreover, it is difficult to find a study or to identify metrics able to measure how effective IRBs are at ensuring the ethical conduct of research or protecting research participants. 61 Improving effectiveness requires clear and measurable goals for IRBs and ethical justification for regulatory requirements. 62

Many of these factors converge for critics of the IRB system: growing requirements and costs, 63 , 64 bureaucratic burden, vague goals, and limited evidence of effectiveness.

“The available evidence indicates that there are substantial direct and indirect costs associated with IRB oversight of research. IRBs also operate inconsistently and inefficiently, and focus their attention on paperwork and bureaucratic compliance. Despite their prevalence, there is no empirical evidence that IRB oversight has any benefit whatsoever—let alone benefit that exceeds the cost.” 65

Both normative analysis and empirical evidence are needed to understand how to improve the current system and optimize protections for contemporary research. If the goal is primarily to protect research participants from risk, for example, then more analysis of what risks count and more empirical evidence about research risks would provide direction for how we are doing and where the gaps are. As Taylor 66 notes, “whether and how to protect is inescapably normative and inescapably empirical.” In its 2011 report Moral Science: Protecting Human Participants in Human Subjects Research , the President’s Commission recommended that federal agencies involved in the funding of human subjects research “develop systematic approaches to assess the effectiveness of human subject protections and expand support for research related to the ethical and social considerations of human subject protections.” 67

Centralizing IRB Review

Primarily driven by concerns about redundant review, burden, and delay, much attention has been given to the idea of single or central IRB review for multisite studies as an alternative to local IRB review at each site. Multiple reviews also have the possibility of jeopardizing the science by introducing bias. 37 Institutions participating in multisite studies are permitted by federal regulations 68 to use arrangements that centralize or share reviews, yet relatively few employ these options. Many proposals for reforming or updating guidance and regulations have recommended single or central review for multisite studies. 10 , 28 ‐ 31 , 35 Lingering resistance to adopting central or single review for multisite trials appears to be based on concerns about the importance of local context, local accountability and liability, discomfort with relinquishing control over the review, uncertainty about the quality of review by other IRBs, and logistical concerns such as cost-sharing. 30 , 54 There is a paucity of data evaluating how single or central review compares to review at local sites regarding quality of review, satisfaction, resource use, or efficiency.

Conclusions

IRBs have an important role in protecting human research participants from possible harm and exploitation. Independent review by an IRB or equivalent is an important part of a system of protections aiming to ensure that ethical principles are followed and that adequate and appropriate safeguards are in place to protect subjects’ rights and welfare while they contribute to ethically and scientifically rigorous research. Over the four decades since IRBs were codified into regulations, IRB review and oversight has developed and matured as part of a robust system that provides “substantial protections for the health, rights, and welfare of research subjects.” 69 However, during that same period, research methods and opportunities have evolved, the domains of oversight have expanded, and the research enterprise has grown and diversified. The rules, norms, procedures, and even articulation of the goals of IRB review have not kept pace. Although ethical principles underlying research with human subjects have not changed, their implementation and actualization requires refinement and adaptation to respond to changing scientific and social contexts. Data, creativity, regulatory flexibility, and continued dialogue are needed to optimize the implementation of principles and to help shape the future structure, organization, processes, and outcomes of review and oversight by IRBs and related players. These efforts will support progress in clinical research, public trust in the enterprise, and protection of the participants that make research possible.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Other contributions: Views expressed are the author’s and do not necessarily represent those of the National Institutes of Health or the Department of Health and Human Services. The author is grateful for the review and helpful suggestions of Scott Kim, MD, PhD, and Charlotte Holden, JD.

ABBREVIATIONS

Department of Health and Human Services

US Food and Drug Administration

institutional review board

National Institutes of Health

Office of Human Research Protections

FUNDING/SUPPORT: Work on this article was supported by the Clinical Center, Department of Bioethics, in the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program.

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians. See online for more details.

- 1. McCarthy C. The origins and policies that govern institutional review boards. In: Emanuel E, Grady C, Crouch R, Lie R, Miller F, Wendler D, eds. The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008:541-550. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. US Code of Federal Regulations. Title 45CFR, part 46. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.html . Accessed January 5, 2015.

- 3. US Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21CFR, part 56. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=56 . Accessed January 5, 2015.

- 4. US Code of Federal Regulations. Title 45CFR.46.101 (h).

- 5. US Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21 CFR 312.120; guidance for industry and FDA staff FDA acceptance of foreign clinical studies not conducted under an IND frequently asked questions.US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM294729.pdf . Accessed April 12, 2015.

- 6. US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Human Research Protections (OHRP). International compilation of human subjects standards. US Department of Health and Human Services website. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/international/intlcompilation/intlcompilation.html . Accessed March 1, 2015.

- 7. ICH guidelines: E6. good clinical practice. International Conference on Harmonisation website. http://www.ich.org/products/guidelines/efficacy/efficacy-single/article/good-clinical-practice.html . Accessed February 2, 2015.

- 8. Riis P. Letter from...Denmark. Planning of scientific-ethical committees. BMJ. 1977;2(6080):173-174. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. Washington, DC: Department of Health Education and Welfare; 1979. DHEW Publication OS 78-0012 1978. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Bowen A. Models of institutional review board function. In: Emanuel E, Grady C, Crouch R, Lie R, Miller F, Wendler D, eds. The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008:552-559. [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Office of Human Subjects Protection. Advanced notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPRM) for revision to Common Rule. US Department of Health and Human Services website. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/anprm2011page.html . 2011. Accessed February 10, 2015.

- 12. Emanuel EJ, Menikoff J. Reforming the regulations governing research with human subjects. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1145-1150. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Office of Human Research Protections. IRBs and assurances. US Department of Health and Human Services website. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/assurances/index.html . Accessed February 2, 2015.

- 14. Office of Budget: appropriations history by institute/center (1938 to present). National Institutes of Health, Office of Budget website. http://officeofbudget.od.nih.gov/approp_hist.html . Accessed March 3, 2015.

- 15. Pharmaceutical R&D and the evolving market for prescription drugs. Congressional Budget Office website. http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/106xx/doc10681/10-26-drugr&d.pdf . 2009. Accessed March 3, 2015.

- 16. Mascette AM, Bernard GR, Dimichele D, et al. Are central institutional review boards the solution? The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group’s report on optimizing the IRB process. Acad Med. 2012;87(12):1710-1714. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Association for the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs. 2013 Metrics on Human Research Protection Program Performance. Washington, DC: Association for the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs; 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Commercial institutional review boards (IRBs). Citizens for Responsible Care and Research website. http://www.circare.org/info/commercialirb.htm . Accessed March 3, 2015.

- 19. Fost N, Levine RJ. The dysregulation of human subjects research. JAMA. 2007;298(18):2196-2198. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Burman WJ, Reves RR, Cohn DL, Schooley RT. Breaking the camel’s back: multicenter clinical trials and local institutional review boards. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(2):152-157. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Gunsalus CK, Bruner EM, Burbules NC, et al. Mission creep in the IRB world. Science. 2006;312(5779):1441. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Weil C, Rooney L, McNeilly P, Cooper K, Borror K, Andreason P. OHRP compliance oversight letters: an update. IRB. 2010;32(2):1-6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Grinding to a halt: the effects of the increasing regulatory burden on research and quality improvement efforts. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(3):328-335. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Silberman G, Kahn KL. Burdens on research imposed by institutional review boards: the state of the evidence and its implications for regulatory reform. Milbank Q. 2011;89(4):599-627. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Whitney SN, Alcser K, Schneider C, McCullough LB, McGuire AL, Volk RJ. Principal investigator views of the IRB system. Int J Med Sci. 2008;5(2):68-72. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Lemonick M, Goldstein A, Park A. Human guinea pigs. Time. April 22, 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Gilbert S. Trials and tribulations. Hastings Cent Rep. 2008;38(2):14-18. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. McCarthy C. The origins and policies that govern institutional review boards. In: Emanuel E, Grady C, Crouch R, Lie R, Miller F, Wendler D, eds. The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008:550. [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Cohen IG, Lynch HF, eds. Introduction. Human Subjects Research Regulation, Perspectives on the Future. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2014:2. [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Association of American Medical Colleges.Alternative Models of IRB Review Workshop summary. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Summary of the 2006 National Conference on Alternative IRB Models: optimizing human subject protection. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/download/75240/data/irbconf06rpt.pdf . November 2006. Accessed January 5, 2015.

- 32. Mascette AM, Bernard GR, Dimichele D, et al. Are central institutional review boards the solution? The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group’s report on optimizing the IRB process. Acad Med. 2012;87(12):1710-1714. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Federman D, Hanna K, Rodriguez L, eds. Responsible Research: A Systems Approach to Protecting Research Participants. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Klitzman R, Appelbaum PS. Research ethics. To protect human subjects, review what was done, not proposed. Science. 2012;335(6076):1576-1577. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Wood A, Grady C, Emanuel EJ. Regional ethics organizations for protection of human research participants. Nat Med. 2004;10(12):1283-1288. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Kim S, Ubel P, DeVries R. Pruning the regulatory tree. Nature. 2009;457(29):534-535. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Check DK, Weinfurt KP, Dombeck CB, Kramer JM, Flynn KE. Use of central institutional review boards for multicenter clinical trials in the United States: a review of the literature. Clin Trials. 2013;10(4):560-567. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Ledford H. Human-subjects research: trial and error. Nature. 2007;448(7153):530-532. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Menikoff J. The paradoxical problem with multiple-IRB review. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(17):1591-1593. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Emanuel EJ, Wood A, Fleischman A, et al. Oversight of human participants research: identifying problems to evaluate reform proposals. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(4):282-291. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Wilfond BS, Magnus D, Antommaria AH, et al. The OHRP and SUPPORT. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):e36. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Fanaroff JM. Ethical support for surfactant, positive pressure, and oxygenation randomized trial (SUPPORT). J Pediatr. 2013;163(5):1498-1499. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Speers M. Evaluating the effectiveness of institutional review boards. In: Emanuel E, Grady C, Crouch R, Lie R, Miller F, Wendler D, eds. The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008:560-568. [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Christian MC, Goldberg JL, Killen J, et al. A central institutional review board for multi-institutional trials. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(18):1405-1408. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. National Cancer Institute Central IRB Initiative. National Cancer Institute website. https://ncicirb.org/cirb . Accessed March 1, 2015.

- 46. Graham DG, Spano MS, Manning B. The IRB challenge for practice-based research: strategies of the American Academy of Family Physicians National Research Network (AAFP NRN). J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(2):181-187. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Office of Research and Development. VA central institutional review board (IRB). US Department of Veterans Affairs website. http://www.research.va.gov/programs/pride/cirb . Accessed March 1, 2015.

- 48. BRANY institutional review board services. Biomedical Research Alliance of New York (BRANY) website. http://www.branyirb.com . Accessed February 3, 2015.

- 49. Kaufmann P, O’Rourke PP. Central institutional review board review for an academic trial network. Acad Med. 2015;90(3):321-323. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Transformation solutions: about us. WIRB-Copernicus Group website. http://wcgclinical.com/about-us/transformational-solutions . Accessed March 10, 2015.

- 51. Why choose Chesapeake IRB? Chesapeake IRB website. https://www.chesapeakeirb.com . Accessed March 10, 2015.

- 52. Tip sheet 24 relying on an external IRB. Association for the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs website. http://www.aahrpp.org/apply/resources/tip-sheets?docSortBy=Updated&docFilterBy=&docStart=5 . Accessed March 10, 2015. See also http://www.niaid.nih.gov/LabsAndResources/resources/toolkit/Pages/faq.aspx , https://irb.research.chop.edu/irb-reliance-agreements , and others.

- 53. Slutsman J, Hirschfeld S. A federated model of IRB review for multisite studies: a report on the National Children’s Study federated IRB initiative. IRB. 2014;36(6):1-6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Request for comments on the draft NIH policy on the use of a single institutional review board for multi-site research. National Institutes of Health website. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-15-026.html . Published December 3, 2014. Accessed March 2, 2015.

- 55. Empirical research on ethical issues related to central IRBs and consent for research using clinical records and data (R01). National Institutes of Health website. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-OD-14-002.html and http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-OD-15-002.html . Accessed April 12, 2015.

- 56. Flynn KE, Hahn CL, Kramer JM, et al. Using central IRBs for multicenter clinical trials in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e54999. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Coleman CH, Bouësseau MC. How do we know that research ethics committees are really working? The neglected role of outcomes assessment in research ethics review. BMC Med Ethics. 2008;9:6. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Abbott L, Grady C. A systematic review of the empirical literature evaluating IRBs: what we know and what we still need to learn. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2011;6(1):3-19. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Lidz CW, Appelbaum PS, Arnold R, et al. How closely do institutional review boards follow the common rule? Acad Med. 2012;87(7):969-974. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Shah S, Whittle A, Wilfond B, Gensler G, Wendler D. How do institutional review boards apply the federal risk and benefit standards for pediatric research? JAMA. 2004;291(4):476-482. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 61. Grady C. Do IRBs protect human research participants? JAMA. 2010;304(10):1122-1123. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 62. Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues. Further analysis and recommendations: recommendation 5. In: Moral Science: Protecting Participants in Human Subjects Research. http://bioethics.gov/sites/default/files/Moral%20Science%20June%202012.pdf . 2011. Accessed February 10, 2015.

- 63. Wagner T, Murray C, Goldberg J, Adler J, Abrams J. Costs and benefits of the National Cancer Institute Central Institutional Review Board. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(4):662-666. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 64. Sugarman J, Getz K, Speckman JL, Byrne MM, Gerson J, Emanuel EJ; Consortium to Evaluate Clinical Research Ethics. The cost of institutional review boards in academic medical centers. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(17):1825-1827. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 65. Hyman D. Institutional review boards: is this the least worst we can do? Northwestern University Law Review. 2007;101(2):749-774. [ Google Scholar ]

- 66. Taylor P. Introduction to part II—protection of vulnerable populations. In: Cohen G, Lynch H, eds. Human Subjects Research Regulation, Perspectives on the Future. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2014:63. [ Google Scholar ]

- 67. Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues. Recommendation 2. In: Moral Science: Protecting Participants in Human Subjects Research. http://bioethics.gov/sites/default/files/Moral%20Science%20June%202012.pdf . 2011. Accessed February 10, 2015.

- 68. US Code of Federal Regulations at 45CFR.46 and 21CFR56.

- 69. Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues. Executive summary. In: Moral Science: Protecting Participants in Human Subjects Research. http://bioethics.gov/sites/default/files/Moral%20Science%20June%202012.pdf . 2011. Accessed February 10, 2015.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (893.6 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Institutional Review Boards: Purpose and Challenges

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Bioethics, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 26042632

- PMCID: PMC4631034

- DOI: 10.1378/chest.15-0706

Institutional review boards (IRBs) or research ethics committees provide a core protection for human research participants through advance and periodic independent review of the ethical acceptability of proposals for human research. IRBs were codified in US regulation just over three decades ago and are widely required by law or regulation in jurisdictions globally. Since the inception of IRBs, the research landscape has grown and evolved, as has the system of IRB review and oversight. Evidence of inconsistencies in IRB review and in application of federal regulations has fueled dissatisfaction with the IRB system. Some complain that IRB review is time-consuming and burdensome without clear evidence of effectiveness at protecting human subjects. Multiple proposals have been offered to reform or update the current IRB system, and many alternative models are currently being tried. Current focus on centralizing and sharing reviews requires more attention and evidence. Proposed changes to the US federal regulations may bring more changes. Data and resourcefulness are needed to further develop and test review and oversight models that provide adequate and respectful protections of participant rights and welfare and that are appropriate, efficient, and adaptable for current and future research.

PubMed Disclaimer

Timeline of regulations and…

Timeline of regulations and guidance regarding IRB review. ANPRM = Advance Notice…

- McCarthy C. The origins and policies that govern institutional review boards. In: Emanuel E, Grady C, Crouch R, Lie R, Miller F, Wendler D, eds. The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008:541-550.

- US Code of Federal Regulations. Title 45CFR, part 46. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.html . Accessed January 5, 2015.

- US Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21CFR, part 56. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CF... . Accessed January 5, 2015.

- US Code of Federal Regulations. Title 45CFR.46.101 (h). - PubMed

- US Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21 CFR 312.120; guidance for industry and FDA staff FDA acceptance of foreign clinical studies not conducted under an IND frequently asked questions.US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM294729.pdf . Accessed April 12, 2015.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Grants and funding

- Intramural NIH HHS/United States

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- ClinicalKey

- Elsevier Science

- Europe PubMed Central

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- PubMed Central

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- JME Commentaries

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 35, Issue 6

- Standards for research ethics committees: purpose, problems and the possibilities of other approaches

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- M Czarkowski

- European Forum for Good Clinical Practice, Brussels, Belgium

- H Davies, National Research Ethics Service, 4–8 Maple Street, London W1T 5HD, UK; Hugh.davies{at}nres.npsa.nhs.uk

Criticism of ethical review of research continues and research ethics committees (RECs) need to demonstrate that they are “fit for purpose” by meeting acknowledged standards of process, debate and outcome. This paper reports a workshop in Warsaw in April 2008, organised by the European Forum for Good Clinical Practice, on the problems of setting standards for RECs in the European Union. Representatives from 27 countries were invited; 16 were represented. Problems identified were the limited and variable resources, difficulties of setting standards for ethical debate and its outcomes and that REC members, as volunteers, may resent the imposition of standards. Other ways to set standards were discussed, including analysis of current multicentre review, collecting REC member reports for review, learning from appeals and feedback from applicants, and use of other regional and national meetings. The place of a central, national board or ethics committee was debated as was the need for collaborating with partners in other fields.

https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2008.027722

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and Peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Linked Articles

- The concise argument The concise argument Soren Holm Journal of Medical Ethics 2009; 35 337-337 Published Online First: 29 May 2009.

- Commentaries Testing children for adult onset conditions: the importance of contextual clinical judgement Anneke Lucassen Angela Fenwick Journal of Medical Ethics 2012; 38 531-532 Published Online First: 04 Jul 2012. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2012-100678

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Formation of a Library Committee in Academic and Research Institutions

A Library Committee is a governing body within academic and research institutions tasked with overseeing the library’s development, management, and strategic direction. Typically composed of faculty members, librarians, administrators, and sometimes students, the committee ensures that the library’s resources, services, and policies align with the institution’s educational and research objectives. The Library Committee plays a vital role in shaping the library’s collection, guiding budget allocations, implementing technology, and establishing policies that govern access and usage. Its importance lies in ensuring that the library remains a dynamic, well-managed, and essential resource supporting the entire institution’s academic and research needs. Formation of a Library Committee

Purpose of Forming a Library Committee

A Library Committee serves as a vital governing body within academic and research institutions, overseeing the development and management of the library’s resources, services, and policies. As libraries evolve from physical spaces housing collections of books to dynamic centers of information and technology, the role of the Library Committee becomes increasingly important. The purpose of forming a Library Committee is multifaceted, ensuring that the library remains aligned with the institution’s academic and research objectives while effectively serving the needs of students, faculty, and researchers. By forming a library committee, institutions can:

- Ensuring Alignment with Academic and Research Goals: One of the primary purposes of a Library Committee is to ensure that the library’s resources and services are aligned with the institution’s academic curriculum and research priorities. Faculty, students, and researchers rely on the library to provide access to a wide range of materials, from books and journals to databases and digital tools. A Library Committee, which often includes representatives from different academic departments, ensures that the library’s collection reflects the institution’s current and future needs. The committee plays a key role in guiding the acquisition of new resources, evaluating the relevance and quality of materials, and advising on subscription renewals for journals and databases. By continuously assessing the needs of faculty and students, the Library Committee ensures that the library stays current and supports both teaching and research endeavors.

- Overseeing Budget Allocation and Financial Management: Effective financial management is crucial for the operation of any library. Much of the library’s budget goes toward acquiring new materials, renewing journal subscriptions, investing in technology, and maintaining infrastructure. The Library Committee is responsible for overseeing the allocation of this budget and ensuring that resources are used efficiently. The committee provides guidance on which library areas require priority funding, such as expanding digital collections, acquiring specialized research materials, or upgrading technology. By managing the budget wisely, the Library Committee ensures that the library remains well-equipped to support the academic and research community without exceeding financial constraints. Additionally, the committee often seeks external funding opportunities, such as grants or partnerships, to supplement the library’s budget.

- Formulating and Reviewing Library Policies: A crucial function of the Library Committee is to establish and regularly review policies that govern the library’s operation. These policies cover many areas, including resource access, borrowing privileges, copyright compliance, and data management. By formulating clear and fair policies, the committee ensures that the library operates smoothly and serves the needs of all users. For example, policies on borrowing materials, interlibrary loans, and digital access ensure that students and faculty can access the resources they need fairly and equitably. Additionally, policies related to user behavior and the use of library spaces help maintain a productive and respectful environment for all patrons. The committee also establishes policies to ensure the ethical use of resources, such as adherence to copyright laws and appropriate handling of sensitive research data.

- Encouraging Technological Integration and Digital Transformation: In today’s digital age, libraries are no longer limited to physical collections. They have become digital learning and research centers, providing access to online databases, e-books, digital journals, and research tools. The Library Committee is critical in integrating these technologies, ensuring the library remains relevant and accessible in the modern academic landscape. The committee advises adopting digital platforms, developing online services, and implementing new technologies such as research data management tools, virtual reference systems, and digital repositories. By supporting digital transformation, the Library Committee ensures that the library continues to meet the evolving needs of students and researchers who increasingly rely on remote access to resources and tools.