Cookies on this website

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you click 'Accept all cookies' we'll assume that you are happy to receive all cookies and you won't see this message again. If you click 'Reject all non-essential cookies' only necessary cookies providing core functionality such as security, network management, and accessibility will be enabled. Click 'Find out more' for information on how to change your cookie settings.

Critical Appraisal tools

Critical appraisal worksheets to help you appraise the reliability, importance and applicability of clinical evidence.

Critical appraisal is the systematic evaluation of clinical research papers in order to establish:

- Does this study address a clearly focused question ?

- Did the study use valid methods to address this question?

- Are the valid results of this study important?

- Are these valid, important results applicable to my patient or population?

If the answer to any of these questions is “no”, you can save yourself the trouble of reading the rest of it.

This section contains useful tools and downloads for the critical appraisal of different types of medical evidence. Example appraisal sheets are provided together with several helpful examples.

Critical Appraisal Worksheets

- Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Diagnostics Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Prognosis Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Randomised Controlled Trials (RCT) Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies Sheet

- IPD Review Sheet

Chinese - translated by Chung-Han Yang and Shih-Chieh Shao

- Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Diagnostic Study Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Prognostic Critical Appraisal Sheet

- RCT Critical Appraisal Sheet

- IPD reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Qualitative Studies Critical Appraisal Sheet

German - translated by Johannes Pohl and Martin Sadilek

- Systematic Review Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Diagnosis Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Prognosis Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Therapy / RCT Critical Appraisal Sheet

Lithuanian - translated by Tumas Beinortas

- Systematic review appraisal Lithuanian (PDF)

- Diagnostic accuracy appraisal Lithuanian (PDF)

- Prognostic study appraisal Lithuanian (PDF)

- RCT appraisal sheets Lithuanian (PDF)

Portugese - translated by Enderson Miranda, Rachel Riera and Luis Eduardo Fontes

- Portuguese – Systematic Review Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – Diagnostic Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – Prognostic Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – RCT Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – Systematic Review Evaluation of Individual Participant Data Worksheet

- Portuguese – Qualitative Studies Evaluation Worksheet

Spanish - translated by Ana Cristina Castro

- Systematic Review (PDF)

- Diagnosis (PDF)

- Prognosis Spanish Translation (PDF)

- Therapy / RCT Spanish Translation (PDF)

Persian - translated by Ahmad Sofi Mahmudi

- Prognosis (PDF)

- PICO Critical Appraisal Sheet (PDF)

- PICO Critical Appraisal Sheet (MS-Word)

- Educational Prescription Critical Appraisal Sheet (PDF)

Explanations & Examples

- Pre-test probability

- SpPin and SnNout

- Likelihood Ratios

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 20 January 2009

How to critically appraise an article

- Jane M Young 1 &

- Michael J Solomon 2

Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology volume 6 , pages 82–91 ( 2009 ) Cite this article

52k Accesses

99 Citations

421 Altmetric

Metrics details

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article in order to assess the usefulness and validity of research findings. The most important components of a critical appraisal are an evaluation of the appropriateness of the study design for the research question and a careful assessment of the key methodological features of this design. Other factors that also should be considered include the suitability of the statistical methods used and their subsequent interpretation, potential conflicts of interest and the relevance of the research to one's own practice. This Review presents a 10-step guide to critical appraisal that aims to assist clinicians to identify the most relevant high-quality studies available to guide their clinical practice.

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article

Critical appraisal provides a basis for decisions on whether to use the results of a study in clinical practice

Different study designs are prone to various sources of systematic bias

Design-specific, critical-appraisal checklists are useful tools to help assess study quality

Assessments of other factors, including the importance of the research question, the appropriateness of statistical analysis, the legitimacy of conclusions and potential conflicts of interest are an important part of the critical appraisal process

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Making sense of the literature: an introduction to critical appraisal for the primary care practitioner

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 2: systematic reviews and meta-analyses

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 1: randomised controlled trials

Druss BG and Marcus SC (2005) Growth and decentralisation of the medical literature: implications for evidence-based medicine. J Med Libr Assoc 93 : 499–501

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Glasziou PP (2008) Information overload: what's behind it, what's beyond it? Med J Aust 189 : 84–85

PubMed Google Scholar

Last JE (Ed.; 2001) A Dictionary of Epidemiology (4th Edn). New York: Oxford University Press

Google Scholar

Sackett DL et al . (2000). Evidence-based Medicine. How to Practice and Teach EBM . London: Churchill Livingstone

Guyatt G and Rennie D (Eds; 2002). Users' Guides to the Medical Literature: a Manual for Evidence-based Clinical Practice . Chicago: American Medical Association

Greenhalgh T (2000) How to Read a Paper: the Basics of Evidence-based Medicine . London: Blackwell Medicine Books

MacAuley D (1994) READER: an acronym to aid critical reading by general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract 44 : 83–85

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hill A and Spittlehouse C (2001) What is critical appraisal. Evidence-based Medicine 3 : 1–8 [ http://www.evidence-based-medicine.co.uk ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Public Health Resource Unit (2008) Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) . [ http://www.phru.nhs.uk/Pages/PHD/CASP.htm ] (accessed 8 August 2008)

National Health and Medical Research Council (2000) How to Review the Evidence: Systematic Identification and Review of the Scientific Literature . Canberra: NHMRC

Elwood JM (1998) Critical Appraisal of Epidemiological Studies and Clinical Trials (2nd Edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2002) Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence? Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 47, Publication No 02-E019 Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Crombie IK (1996) The Pocket Guide to Critical Appraisal: a Handbook for Health Care Professionals . London: Blackwell Medicine Publishing Group

Heller RF et al . (2008) Critical appraisal for public health: a new checklist. Public Health 122 : 92–98

Article Google Scholar

MacAuley D et al . (1998) Randomised controlled trial of the READER method of critical appraisal in general practice. BMJ 316 : 1134–37

Article CAS Google Scholar

Parkes J et al . Teaching critical appraisal skills in health care settings (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 3. Art. No.: cd001270. 10.1002/14651858.cd001270

Mays N and Pope C (2000) Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 320 : 50–52

Hawking SW (2003) On the Shoulders of Giants: the Great Works of Physics and Astronomy . Philadelphia, PN: Penguin

National Health and Medical Research Council (1999) A Guide to the Development, Implementation and Evaluation of Clinical Practice Guidelines . Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council

US Preventive Services Taskforce (1996) Guide to clinical preventive services (2nd Edn). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins

Solomon MJ and McLeod RS (1995) Should we be performing more randomized controlled trials evaluating surgical operations? Surgery 118 : 456–467

Rothman KJ (2002) Epidemiology: an Introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: sources of bias in surgical studies. ANZ J Surg 73 : 504–506

Margitic SE et al . (1995) Lessons learned from a prospective meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 43 : 435–439

Shea B et al . (2001) Assessing the quality of reports of systematic reviews: the QUORUM statement compared to other tools. In Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Context 2nd Edition, 122–139 (Eds Egger M. et al .) London: BMJ Books

Chapter Google Scholar

Easterbrook PH et al . (1991) Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 337 : 867–872

Begg CB and Berlin JA (1989) Publication bias and dissemination of clinical research. J Natl Cancer Inst 81 : 107–115

Moher D et al . (2000) Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUORUM statement. Br J Surg 87 : 1448–1454

Shea BJ et al . (2007) Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 7 : 10 [10.1186/1471-2288-7-10]

Stroup DF et al . (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283 : 2008–2012

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: evaluating surgical effectiveness. ANZ J Surg 73 : 507–510

Schulz KF (1995) Subverting randomization in controlled trials. JAMA 274 : 1456–1458

Schulz KF et al . (1995) Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 273 : 408–412

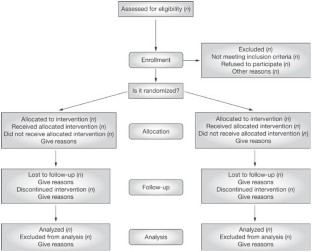

Moher D et al . (2001) The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology 1 : 2 [ http://www.biomedcentral.com/ 1471-2288/1/2 ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Rochon PA et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 1. Role and design. BMJ 330 : 895–897

Mamdani M et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ 330 : 960–962

Normand S et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 3. Analytical strategies to reduce confounding. BMJ 330 : 1021–1023

von Elm E et al . (2007) Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 335 : 806–808

Sutton-Tyrrell K (1991) Assessing bias in case-control studies: proper selection of cases and controls. Stroke 22 : 938–942

Knottnerus J (2003) Assessment of the accuracy of diagnostic tests: the cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol 56 : 1118–1128

Furukawa TA and Guyatt GH (2006) Sources of bias in diagnostic accuracy studies and the diagnostic process. CMAJ 174 : 481–482

Bossyut PM et al . (2003)The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 138 : W1–W12

STARD statement (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies). [ http://www.stard-statement.org/ ] (accessed 10 September 2008)

Raftery J (1998) Economic evaluation: an introduction. BMJ 316 : 1013–1014

Palmer S et al . (1999) Economics notes: types of economic evaluation. BMJ 318 : 1349

Russ S et al . (1999) Barriers to participation in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 52 : 1143–1156

Tinmouth JM et al . (2004) Are claims of equivalency in digestive diseases trials supported by the evidence? Gastroentrology 126 : 1700–1710

Kaul S and Diamond GA (2006) Good enough: a primer on the analysis and interpretation of noninferiority trials. Ann Intern Med 145 : 62–69

Piaggio G et al . (2006) Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA 295 : 1152–1160

Heritier SR et al . (2007) Inclusion of patients in clinical trial analysis: the intention to treat principle. In Interpreting and Reporting Clinical Trials: a Guide to the CONSORT Statement and the Principles of Randomized Controlled Trials , 92–98 (Eds Keech A. et al .) Strawberry Hills, NSW: Australian Medical Publishing Company

National Health and Medical Research Council (2007) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 89–90 Canberra: NHMRC

Lo B et al . (2000) Conflict-of-interest policies for investigators in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 343 : 1616–1620

Kim SYH et al . (2004) Potential research participants' views regarding researcher and institutional financial conflicts of interests. J Med Ethics 30 : 73–79

Komesaroff PA and Kerridge IH (2002) Ethical issues concerning the relationships between medical practitioners and the pharmaceutical industry. Med J Aust 176 : 118–121

Little M (1999) Research, ethics and conflicts of interest. J Med Ethics 25 : 259–262

Lemmens T and Singer PA (1998) Bioethics for clinicians: 17. Conflict of interest in research, education and patient care. CMAJ 159 : 960–965

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

JM Young is an Associate Professor of Public Health and the Executive Director of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney,

Jane M Young

MJ Solomon is Head of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre and Director of Colorectal Research at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney, Australia.,

Michael J Solomon

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jane M Young .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Young, J., Solomon, M. How to critically appraise an article. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 6 , 82–91 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Download citation

Received : 10 August 2008

Accepted : 03 November 2008

Published : 20 January 2009

Issue Date : February 2009

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Emergency physicians’ perceptions of critical appraisal skills: a qualitative study.

- Sumintra Wood

- Jacqueline Paulis

- Angela Chen

BMC Medical Education (2022)

An integrative review on individual determinants of enrolment in National Health Insurance Scheme among older adults in Ghana

- Anthony Kwame Morgan

- Anthony Acquah Mensah

BMC Primary Care (2022)

Autopsy findings of COVID-19 in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Anju Khairwa

- Kana Ram Jat

Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology (2022)

The use of a modified Delphi technique to develop a critical appraisal tool for clinical pharmacokinetic studies

- Alaa Bahaa Eldeen Soliman

- Shane Ashley Pawluk

- Ousama Rachid

International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy (2022)

Critical Appraisal: Analysis of a Prospective Comparative Study Published in IJS

- Ramakrishna Ramakrishna HK

- Swarnalatha MC

Indian Journal of Surgery (2021)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Critical Appraisal Tools

- Introduction

- Related Guides

- Getting Help

Critical Appraisal of Studies

Critical appraisal is the process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, and its value/relevance in a particular context by providing a framework to evaluate the research. During the critical appraisal process, researchers can:

- Decide whether studies have been undertaken in a way that makes their findings reliable as well as valid and unbiased

- Make sense of the results

- Know what these results mean in the context of the decision they are making

- Determine if the results are relevant to their patients/schoolwork/research

Burls, A. (2009). What is critical appraisal? In What Is This Series: Evidence-based medicine. Available online at What is Critical Appraisal?

Critical appraisal is included in the process of writing high quality reviews, like systematic and integrative reviews and for evaluating evidence from RCTs and other study designs. For more information on systematic reviews, check out our Systematic Review guide.

- Next: Critical Appraisal Tools >>

- Last Updated: Nov 16, 2023 1:27 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.duq.edu/critappraise

Critical Appraisal: Assessing the Quality of Studies

- First Online: 05 August 2020

Cite this chapter

- Edward Purssell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3748-0864 3 &

- Niall McCrae ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9776-7694 4

8748 Accesses

There is great variation in the type and quality of research evidence. Having completed your search and assembled your studies, the next step is to critically appraise the studies to ascertain their quality. Ultimately you will be making a judgement about the overall evidence, but that comes later. You will see throughout this chapter that we make a clear differentiation between the individual studies and what we call the body of evidence , which is all of the studies and anything else that we use to answer the question or to make a recommendation. This chapter deals with only the first of these—the individual studies. Critical appraisal, like everything else in systematic literature reviewing, is a scientific exercise that requires individual judgement, and we describe some tools to help you.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM) (2016) OCEBM levels of evidence. In: CEBM. https://www.cebm.net/2016/05/ocebm-levels-of-evidence/ . Accessed 17 Apr 2020

Aromataris E, Munn Z (eds) (2017) Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute, Adelaide

Google Scholar

Daly J, Willis K, Small R et al (2007) A hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research. J Clin Epidemiol 60:43–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.014

Article PubMed Google Scholar

EQUATOR Network (2020) What is a reporting guideline?—The EQUATOR Network. https://www.equator-network.org/about-us/what-is-a-reporting-guideline/ . Accessed 7 Mar 2020

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19:349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al (2007) The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med 4:e296. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296

Article Google Scholar

Brouwers MC, Kerkvliet K, Spithoff K, AGREE Next Steps Consortium (2016) The AGREE reporting checklist: a tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 352:i1152. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1152

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Boutron I, Page MJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Lundh A, Hróbjartsson A (2019) Chapter 7: Considering bias and conflicts of interest among the included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019), Cochrane. https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018) CASP checklists. In: CASP—critical appraisal skills programme. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ . Accessed 7 Mar 2020

Higgins JPT, Savović J, Page MJ et al (2019) Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J et al (eds) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane, London

Chapter Google Scholar

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al (2011) GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence—imprecision. J Clin Epidemiol 64:1283–1293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.012

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ et al (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC et al (2016) ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 355:i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D et al (2019) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp . Accessed 7 Mar 2020

Cochrane Community (2020) Glossary—Cochrane community. https://community.cochrane.org/glossary#letter-R . Accessed 8 Mar 2020

Messick S (1989) Meaning and values in test validation: the science and ethics of assessment. Educ Res 18:5–11. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X018002005

Sparkes AC (2001) Myth 94: qualitative health researchers will agree about validity. Qual Health Res 11:538–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973230101100409

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Aguinis H, Solarino AM (2019) Transparency and replicability in qualitative research: the case of interviews with elite informants. Strat Manag J 40:1291–1315. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3015

Lincoln YS, Guba EG (1985) Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA

Book Google Scholar

Hannes K (2011) Chapter 4: Critical appraisal of qualitative research. In: Noyes J, Booth A, Hannes K et al (eds) Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group, London

Munn Z, Porritt K, Lockwood C et al (2014) Establishing confidence in the output of qualitative research synthesis: the ConQual approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 14:108. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-108

Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N et al (2013) ‘Trying to pin down jelly’—exploring intuitive processes in quality assessment for meta-ethnography. BMC Med Res Methodol 13:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-46

Katikireddi SV, Egan M, Petticrew M (2015) How do systematic reviews incorporate risk of bias assessments into the synthesis of evidence? A methodological study. J Epidemiol Community Health 69:189–195. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204711

McKenzie JE, Brennan SE, Ryan RE et al (2019) Chapter 9: Summarizing study characteristics and preparing for synthesis. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J et al (eds) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane, London

Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG (2019) Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J et al (eds) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane, London

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Health Sciences, City, University of London, London, UK

Edward Purssell

Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery & Palliative Care, King’s College London, London, UK

Niall McCrae

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Edward Purssell .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Purssell, E., McCrae, N. (2020). Critical Appraisal: Assessing the Quality of Studies. In: How to Perform a Systematic Literature Review. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49672-2_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49672-2_6

Published : 05 August 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-49671-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-49672-2

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Geoffrey R. Weller Library

View complete hours

- Subject Guides

Knowledge Synthesis Guide

- Critical Appraisal

- What is Knowledge Synthesis?

- Developing your question

- Consider Eligibility Criteria

- Grey Literature

- Create Search Terms for Each Concept

- Identify Controlled Vocabulary for Each Concept

- Building Your Search

- Translating a Search Strategy

- Run Your Searches

- Reporting Your Results with PRISMA

- Utilize a Screening Tool

- Data Extraction

- Information About Publishing This link opens in a new window

Tools for Critical Appraisal

Critical appraisal is the careful analysis of a study to assess trustworthiness, relevance and results of published research. Here are some tools to guide you.

- JBI Critical Appraisal

- CASP Checklists

- The AACODS checklist

Appraisal Resources - Grey Literature

Appraising Grey Literature:

- Guide to Appraising Grey Literature ( Public Health Ontario)

- << Previous: Utilize a Screening Tool

- Next: Data Extraction >>

- Last Updated: Sep 20, 2024 9:48 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unbc.ca/KnowledgeSynthesis

Geoffrey R. Weller Library University of Northern British Columbia 3333 University Way Prince George, B.C. V2N 4Z9

Circulation: (250) 960-6613 Reference: (250) 960-6475 Regional Services: 1-888-440-3440 (toll free within 250 area code)

- Suggestions Form

- Planning & Policies

- Staff Directory

- Frequently Called Numbers

- Citation Management

- Course Reserves

- Faculty Services

- Interlibrary Loans

- Open Access

- Data & Statistics

- Maps & Photos

- Research Help

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

- Submit a Manuscript

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Critical appraisal of a clinical research paper

What one needs to know.

Manjali, Jifmi Jose; Gupta, Tejpal

Department of Radiation Oncology, Tata Memorial Centre, Homi Bhabha National Institute, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Address for correspondence: Dr. Tejpal Gupta, ACTREC, Tata Memorial Centre, Homi Bhabha National Institute, Kharghar, Navi Mumbai - 410 210, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: [email protected]

Received May 25, 2020

Received in revised form June 11, 2020

Accepted June 19, 2020

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

In the present era of evidence-based medicine (EBM), integrating best research evidence into the clinical practice necessitates developing skills to critically evaluate and analyze the scientific literature. Critical appraisal is the process of systematically examining research evidence to assess its validity, results, and relevance to inform clinical decision-making. All components of a clinical research article need to be appraised as per the study design and conduct. As research bias can be introduced at every step in the flow of a study leading to erroneous conclusions, it is essential that suitable measures are adopted to mitigate bias. Several tools have been developed for the critical appraisal of scientific literature, including grading of evidence to help clinicians in the pursuit of EBM in a systematic manner. In this review, we discuss the broad framework for the critical appraisal of a clinical research paper, along with some of the relevant guidelines and recommendations.

INTRODUCTION

Medical research information is ever growing and branching day by day. Despite the vastness of medical literature, it is necessary that as clinicians we offer the best treatment to our patients as per the current knowledge. Integrating best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values has led to the concept of evidence-based medicine (EBM).[ 1 ] Although this philosophy originated in the middle of the 19 th century,[ 2 ] it first appeared in its current form in the modern medical literature in 1991.[ 3 ] EBM is defined as the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of the current best evidence in making decisions about the care of an individual patient.[ 1 ] The essentials of EBM include generating a clinical question, tracking the best available evidence, critically evaluating the evidence for validity and clinical usefulness, further applying the results to clinical practice, and evaluating its performance. Appropriate application of EBM can result in cost-effectiveness and improve health-care efficiency.[ 4 ] Without continual accumulation of new knowledge, existing dogmas and paradigms quickly become outdated and may prove detrimental to the patients. The current growth of medical literature with 1.8 million scientific articles published in the year 2012,[ 5 ] often makes it difficult for the clinicians to keep pace with the vast amount of scientific data, thus making foraging (alerts to new information) and hunting (finding answers to clinical questions) essential skills to help navigate the so-called “jungle” of information.[ 6 ] Therefore, it is essential that health-care professionals read medical literature selectively to effectively utilize their limited time and assiduously imbibe new knowledge to improve decision-making for their patients. To practice EBM in its true sense, a clinician not only needs to devote time to develop the skill of effectively searching the literature, but also needs to learn to evaluate the significance, methodology, outcomes, and transparency of the study.[ 4 ] Along with the evaluation and interpretation of a study, a thorough understanding of its methodology is necessary. It is common knowledge that studies with positive results are relatively easy to publish.[ 7 8 ] However, it is the critical appraisal of any research study (even those with negative results) that helps us to understand the science better and ask relevant questions in future using an appropriate study design and endpoints. Therefore, this review is focused on the framework for the critical appraisal of a clinical research paper. In addition, we have also discussed some of the relevant guidelines and recommendations for the critical appraisal of clinical research papers.

CRITICAL APPRAISAL

Critical appraisal is the process of systematically examining the research evidence to assess its validity, results, and relevance before using it to inform a decision.[ 9 ] It entails the following:

- Balanced assessment of the benefits/strengths and flaws/weaknesses of a study

- Assessment of the research process and results

- Consideration of quantitative and qualitative aspects.

Critical appraisal is performed to assess the following

aspects of a study:

- Validity – Is the methodology robust?

- Reliability – Are the results credible?

- Applicability– Do the results have the potential to change the current practice?

Contrary to the common belief, a critical appraisal is not the negative dismissal of any piece of research or an assessment of the results alone; it is neither solely based on a statistical analysis nor a process undertaken by the experts only. When performing a critical appraisal of a scientific article, it is essential that we know its basic composition and assess every section meticulously.

Initial assessment

This involves taking a generalized look at the details of the article. The journal it was published in holds special value – a peer reviewed, indexed journal with a good impact factor adds robustness to the paper. The setting, timeline, and year of publication of the study also need to be noted, as they provide a better understanding of the evolution of thoughts in that particular subject. Declaration of the conflicts of interest by the authors, the role of the funding source if any, and any potential commercial bias should also be noted.[ 10 ]

COMPONENTS OF A CLINICAL RESEARCH PAPER

The components of any scientific article or clinical research paper remain largely the same. An article begins with a title, abstract, and keywords, which are followed by the main text, which includes the IMRAD – introduction, methods, results and discussion, and ends with the conclusion and references.

It is a brief summary of the research article which helps the readers understand the purpose, methods, and results of the study. Although an abstract may provide a brief overview of the study, the full text of the article needs to be read and evaluated for a thorough understanding. There are two types of abstracts, namely structured and unstructured. A structured abstract comprises different sections typically labelled as background/purpose, methods, results, and conclusion, whereas an unstructured abstract is not divided into these sections.

Introduction

The introduction of a research paper familiarizes the reader with the topic. It refers to the current evidence in the particular subject and the possible lacunae which necessitate the present study. In other words, the introduction puts the study in perspective. The findings of other related studies have to be quoted and referenced, especially their central statements. The introduction also needs to justify the appropriateness of the chosen study.[ 11 ]

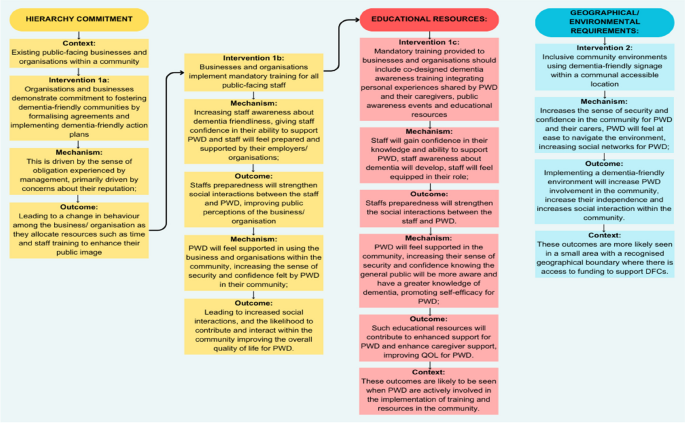

This section highlights the procedure followed while conducting the study. It provides all the data necessary for the study's appraisal and lays out the study design which is paramount. For clinical research articles, this section should describe the participant or patient/population/problem (P), intervention (I), comparison (C), outcome (O), and study design (S) PICO(S), generally referred to as the PICO(S) framework [ Table 1 ].

Study designs and levels of evidence

Study designs are broadly divided into descriptive and interventional studies,[ 12 ] which can be further subdivided as shown in Figure 1 . Each study design has its own characteristics and should be used in the appropriate setting. The various study designs form the building blocks of evidence. This in turn justifies the need for a hierarchical classification of evidence, referred to as “Levels of Evidence,” as it forms the cornerstone of EBM [ Table 2 ]. Most medical journals now mandate that the submitted manuscript conform to and comply with the clinical research reporting statements and guidelines as applicable to the study design [ Table 3 ] to maintain clarity, transparency, and reproducibility and ensure comparability across different studies asking the same research question. As per the study design, the appropriate descriptive and inferential statistical analyses should be specified in the statistical plan. For prospective studies, a clear mention of sample size calculation (depending on the type of study, power, alpha error, meaningful difference, and variance) is mandatory, so as to identify whether the study was adequately powered.[ 13 ] The endpoints (primary, secondary, and exploratory, if any) should be mentioned clearly along with the exact methods used for the measurement of the variables.

Statistical testing

The statistical framework of any research study is commonly based on testing the null hypothesis, wherein the results are deemed significant by comparing P values obtained from an experimental dataset to a predefined significance level (0.05 being the most popular choice). By definition, P value is the probability under the specified statistical model to obtain a statistical summary equal to or more extreme than the one computed from the data and can range from 0 to 1. P < 0.05 indicates that results are unlikely to be due to chance alone. Unfortunately, P value does not indicate the magnitude of the observed difference, which may also be desirable. An alternative and complementary approach is the use of confidence intervals (CI), which is a range of values calculated from the observed data, that is likely to contain the true value at a specified probability. The probability is chosen by the investigator, and it is set customarily at 95% (1– alpha error of 0.05). CI provides information that may be used to test hypotheses; additionally, they provide information related to the precision, power, sample size, and effect size.

This section contains the findings of the study, presented clearly and objectively. The results obtained using the descriptive and inferential statistical analyses (as mentioned in the methods section) should be described. The use of tables and figures, including graphical representation [ Table 4 ], is encouraged to improve the clarity;[ 14 ] however, the duplication of these data in the text should be avoided.

The discussion section presents the authors' interpretations of the obtained results. This section includes:

- A comparison of the study results with what is currently known, drawing similarities and differences

- Novel findings of the study that have added to the existing body of knowledge

- Caveats and limitations.

It is imperative that the key relevant references are cited in any research paper in the appropriate format which allows the readers to access the original source of the specified statement or evidence. A brief look at the reference list gives an overview of how well the indexed medical literature was searched for the purpose of writing the manuscript.

Overall assessment

After a careful assessment of the various sections of a research article, it is necessary to assess the relevance of the study findings to the present scenario and weigh the potential benefits and drawbacks of its application to the population. In this context, it is necessary that the integrity of the intervention be noted. This can be verified by assessing the factors such as adherence to the specified program, the exposure needed, quality of delivery, participant responsiveness, and potential contamination. This relates to the feasibility of applying the intervention to the community.

BIAS IN CLINICAL RESEARCH

Research articles are the media through which science is communicated, and it is necessary that we adhere to the basic principles of transparency and accuracy when communicating our findings. Any such trend or deviation from the truth in data collection, analysis, interpretation, or publication is called bias.[ 15 ] This may lead to erroneous conclusions, and hence, all scientists and clinicians must be aware of the bias and employ all possible measures to mitigate it.

The extent to which a study is free from bias defines its internal validity. Internal validity is different from the external validity and precision. The external validity of a study is about its generalizability or applicability (depends on the purpose of the study), while precision is the extent to which a study is free from random errors (depends on the number of participants). A study is irrelevant without internal validity even if it is applicable and precise.[ 16 ] A bias can be introduced at every step in the flow of a study [ Figure 2 ].

The various types of biases in clinical research include:

- Selection bias: This happens while recruiting patients. This may lead to the differences in the way patients are accepted or rejected for a trial and the way in which interventions are assigned to the individuals. We need to assess whether the study population is a true representative of the target population. Furthermore, when there is no or an inadequate sequence generation, it can result in the over-estimation of treatment effects compared to randomized trials.[ 14 ] This can be mitigated by using a process called randomization. Randomization is the process of assigning clinical trial participants to treatment groups, such that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to a particular group. This process should be completely random (e.g., tossing a coin, using a computer program, and throwing dice). When the process is not exactly random (e.g., randomization by date of birth, odd-even numbers, alternation, registration date, etc.), there is a significant potential for a selection bias

- Allocation bias: This is a bias that sets in when the person responsible for the study also allocates the treatment. It is known that inadequate or unclear concealment of allocation can lead to an overestimation of the treatment effects.[ 17 ] Adequate allocation concealment helps in mitigating this bias. This can be done by sequentially numbering identical drug containers or through central allocation by a person not involved in study enrollment

- Confounding bias: Having an effect on the dependent and independent variables through a spurious association, confounding factors can introduce a significant bias. Hence, the baseline characteristics need to be similar in the groups being compared. Known confounders can be managed during the selection process by stratified randomization (in randomized trials) and matching (in observational studies) or during analysis by meta-regression.[ 18 ] However, the unknown confounders can be minimized only through randomization

- Performance bias: This is a bias that is introduced because of the knowledge about the intervention allocation in the patient, investigator, or outcome assessor. This results in ascertainment or recall bias (patient), reporting bias (investigator), and detection bias (outcome assessor), all of which can lead to an overestimation of the treatment effects.[ 17 ] This can be mitigated by blinding – a process in which the treatment allocation is hidden from the patient, investigator, and/or outcome assessor. However, it has to be noted that blinding may not be practical or possible in all kinds of clinical trials

- Method bias: In clinical trials, it is necessary that the outcomes be assessed and recorded using valid and reliable tools, the lack of which can introduce a method bias[ 19 ]

- Attrition bias: This is a bias that is introduced because of the systematic differences between the groups in the loss of participants from the study. It is necessary to describe the completeness of the outcomes including the exclusions (along with the reasons), loss to follow-up, and drop-outs from the analysis

- Other bias: This includes any important concerns about biases not covered in the other domains.

Trial registration

In the recent times, it has become an ethical as well as a regulatory requirement in most countries to register the clinical trials prospectively before the enrollment of the first subject. Registration of a clinical trial is defined as the publication of an internationally agreed upon set of information about the design, conduct, and administration of any clinical trial on a publicly accessible website managed by a registry conforming to international standards. Apart from improving the awareness and visibility of the study, registration ensures transparency in the conduct and reduces publication bias and selective reporting. Some of the common sites are the ClinicalTrials. gov run by the National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health (), Clinical Trials Registry-India () run by the Indian Council of Medical Research, and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform () run by the World Health Organization.

Tools for critical appraisal

Several tools have been developed to assess the transparency of the scientific research papers and the degree of congruence of the research question with the study in the context of the various sections listed above [ Table 5 ].

Ethical considerations

Bad ethics cannot produce good science. Therefore, all scientific research must follow the ethical principles laid out in the declaration of Helsinki. For clinical research, it is mandatory that team members be trained in good clinical practice, familiarize themselves with clinical research methodology, and follow standard operating procedures as prescribed. Although the regulatory framework and landscape may vary to a certain extent depending upon the country where the research work is conducted, it is the responsibility of the Institutional Review Boards/Institutional Ethics Committees to provide study oversight such that the safety, well-being, and rights of the participants are adequately protected.

CONCLUSIONS

Critical appraisal is the systematic examination of the research evidence reported in the scientific articles to assess their validity, reliability, and applicability before using their findings to inform decision-making. It should be considered as the first step to grade the quality of evidence.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- Cited Here |

- Google Scholar

Appraisal; bias; clinical study; evidence-based medicine; guidelines; tools

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Epidemiological studies of risk factors could aid in designing risk....

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 16 September 2004

A systematic review of the content of critical appraisal tools

- Persis Katrak 1 ,

- Andrea E Bialocerkowski 2 ,

- Nicola Massy-Westropp 1 ,

- VS Saravana Kumar 1 &

- Karen A Grimmer 1

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 4 , Article number: 22 ( 2004 ) Cite this article

160k Accesses

208 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

Consumers of research (researchers, administrators, educators and clinicians) frequently use standard critical appraisal tools to evaluate the quality of published research reports. However, there is no consensus regarding the most appropriate critical appraisal tool for allied health research. We summarized the content, intent, construction and psychometric properties of published, currently available critical appraisal tools to identify common elements and their relevance to allied health research.

A systematic review was undertaken of 121 published critical appraisal tools sourced from 108 papers located on electronic databases and the Internet. The tools were classified according to the study design for which they were intended. Their items were then classified into one of 12 criteria based on their intent. Commonly occurring items were identified. The empirical basis for construction of the tool, the method by which overall quality of the study was established, the psychometric properties of the critical appraisal tools and whether guidelines were provided for their use were also recorded.

Eighty-seven percent of critical appraisal tools were specific to a research design, with most tools having been developed for experimental studies. There was considerable variability in items contained in the critical appraisal tools. Twelve percent of available tools were developed using specified empirical research. Forty-nine percent of the critical appraisal tools summarized the quality appraisal into a numeric summary score. Few critical appraisal tools had documented evidence of validity of their items, or reliability of use. Guidelines regarding administration of the tools were provided in 43% of cases.

Conclusions

There was considerable variability in intent, components, construction and psychometric properties of published critical appraisal tools for research reports. There is no "gold standard' critical appraisal tool for any study design, nor is there any widely accepted generic tool that can be applied equally well across study types. No tool was specific to allied health research requirements. Thus interpretation of critical appraisal of research reports currently needs to be considered in light of the properties and intent of the critical appraisal tool chosen for the task.

Peer Review reports

Consumers of research (clinicians, researchers, educators, administrators) frequently use standard critical appraisal tools to evaluate the quality and utility of published research reports [ 1 ]. Critical appraisal tools provide analytical evaluations of the quality of the study, in particular the methods applied to minimise biases in a research project [ 2 ]. As these factors potentially influence study results, and the way that the study findings are interpreted, this information is vital for consumers of research to ascertain whether the results of the study can be believed, and transferred appropriately into other environments, such as policy, further research studies, education or clinical practice. Hence, choosing an appropriate critical appraisal tool is an important component of evidence-based practice.

Although the importance of critical appraisal tools has been acknowledged [ 1 , 3 – 5 ] there appears to be no consensus regarding the 'gold standard' tool for any medical evidence. In addition, it seems that consumers of research are faced with a large number of critical appraisal tools from which to choose. This is evidenced by the recent report by the Agency for Health Research Quality in which 93 critical appraisal tools for quantitative studies were identified [ 6 ]. Such choice may pose problems for research consumers, as dissimilar findings may well be the result when different critical appraisal tools are used to evaluate the same research report [ 6 ].

Critical appraisal tools can be broadly classified into those that are research design-specific and those that are generic. Design-specific tools contain items that address methodological issues that are unique to the research design [ 5 , 7 ]. This precludes comparison however of the quality of different study designs [ 8 ]. To attempt to overcome this limitation, generic critical appraisal tools have been developed, in an attempt to enhance the ability of research consumers to synthesise evidence from a range of quantitative and or qualitative study designs (for instance [ 9 ]). There is no evidence that generic critical appraisal tools and design-specific tools provide a comparative evaluation of research designs.

Moreover, there appears to be little consensus regarding the most appropriate items that should be contained within any critical appraisal tool. This paper is concerned primarily with critical appraisal tools that address the unique properties of allied health care and research [ 10 ]. This approach was taken because of the unique nature of allied health contacts with patients, and because evidence-based practice is an emerging area in allied health [ 10 ]. The availability of so many critical appraisal tools (for instance [ 6 ]) may well prove daunting for allied health practitioners who are learning to critically appraise research in their area of interest. For the purposes of this evaluation, allied health is defined as encompassing "...all occasions of service to non admitted patients where services are provided at units/clinics providing treatment/counseling to patients. These include units primarily concerned with physiotherapy, speech therapy, family panning, dietary advice, optometry occupational therapy..." [ 11 ].

The unique nature of allied health practice needs to be considered in allied health research. Allied health research thus differs from most medical research, with respect to:

• the paradigm underpinning comprehensive and clinically-reasoned descriptions of diagnosis (including validity and reliability). An example of this is in research into low back pain, where instead of diagnosis being made on location and chronicity of pain (as is common) [ 12 ], it would be made on the spinal structure and the nature of the dysfunction underpinning the symptoms, which is arrived at by a staged and replicable clinical reasoning process [ 10 , 13 ].

• the frequent use of multiple interventions within the one contact with the patient (an occasion of service), each of which requires appropriate description in terms of relationship to the diagnosis, nature, intensity, frequency, type of instruction provided to the patient, and the order in which the interventions were applied [ 13 ]

• the timeframe and frequency of contact with the patient (as many allied health disciplines treat patients in episodes of care that contain multiple occasions of service, and which can span many weeks, or even years in the case of chronic problems [ 14 ])

• measures of outcome, including appropriate methods and timeframes of measuring change in impairment, function, disability and handicap that address the needs of different stakeholders (patients, therapists, funders etc) [ 10 , 12 , 13 ].

Search strategy

In supplementary data [see additional file 1 ].

Data organization and extraction

Two independent researchers (PK, NMW) participated in all aspects of this review, and they compared and discussed their findings with respect to inclusion of critical appraisal tools, their intent, components, data extraction and item classification, construction and psychometric properties. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third member of the team (KG).

Data extraction consisted of a four-staged process. First, identical replica critical appraisal tools were identified and removed prior to analysis. The remaining critical appraisal tools were then classified according to the study design for which they were intended to be used [ 1 , 2 ]. The scientific manner in which the tools had been constructed was classified as whether an empirical research approach has been used, and if so, which type of research had been undertaken. Finally, the items contained in each critical appraisal tool were extracted and classified into one of eleven groups, which were based on the criteria described by Clarke and Oxman [ 4 ] as:

• Study aims and justification

• Methodology used , which encompassed method of identification of relevant studies and adherence to study protocol;

• Sample selection , which ranged from inclusion and exclusion criteria, to homogeneity of groups;

• Method of randomization and allocation blinding;

• Attrition : response and drop out rates;

• Blinding of the clinician, assessor, patient and statistician as well as the method of blinding;

• Outcome measure characteristics;

• Intervention or exposure details;

• Method of data analyses ;

• Potential sources of bias ; and

• Issues of external validity , which ranged from application of evidence to other settings to the relationship between benefits, cost and harm.

An additional group, " miscellaneous ", was used to describe items that could not be classified into any of the groups listed above.

Data synthesis

Data was synthesized using MS Excel spread sheets as well as narrative format by describing the number of critical appraisal tools per study design and the type of items they contained. Descriptions were made of the method by which the overall quality of the study was determined, evidence regarding the psychometric properties of the tools (validity and reliability) and whether guidelines were provided for use of the critical appraisal tool.

One hundred and ninety-three research reports that potentially provided a description of a critical appraisal tool (or process) were identified from the search strategy. Fifty-six of these papers were unavailable for review due to outdated Internet links, or inability to source the relevant journal through Australian university and Government library databases. Of the 127 papers retrieved, 19 were excluded from this review, as they did not provide a description of the critical appraisal tool used, or were published in languages other than English. As a result, 108 papers were reviewed, which yielded 121 different critical appraisal tools [ 1 – 5 , 7 , 9 , 15 – 102 , 116 ].

Empirical basis for tool construction

We identified 14 instruments (12% all tools) which were reported as having been constructed using a specified empirical approach [ 20 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 35 , 40 , 49 , 51 , 70 – 72 , 79 , 103 , 116 ]. The empirical research reflected descriptive and/or qualitative approaches, these being critical review of existing tools [ 40 , 72 ], Delphi techniques to identify then refine data items [ 32 , 51 , 71 ], questionnaires and other forms of written surveys to identify and refine data items [ 70 , 79 , 103 ], facilitated structured consensus meetings [ 20 , 29 , 30 , 35 , 40 , 49 , 70 , 72 , 79 , 116 ], and pilot validation testing [ 20 , 40 , 72 , 103 , 116 ]. In all the studies which reported developing critical appraisal tools using a consensus approach, a range of stakeholder input was sought, reflecting researchers and clinicians in a range of health disciplines, students, educators and consumers. There were a further 31 papers which cited other studies as the source of the tool used in the review, but which provided no information on why individual items had been chosen, or whether (or how) they had been modified. Moreover, for 21 of these tools, the cited sources of the critical appraisal tool did not report the empirical basis on which the tool had been constructed.

Critical appraisal tools per study design

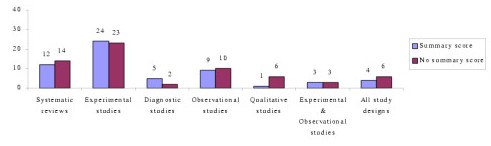

Seventy-eight percent (N = 94) of the critical appraisal tools were developed for use on primary research [ 1 – 5 , 7 , 9 , 18 , 19 , 25 – 27 , 34 , 37 – 41 ], while the remainder (N = 26) were for secondary research (systematic reviews and meta-analyses) [ 2 – 5 , 15 – 36 , 116 ]. Eighty-seven percent (N = 104) of all critical appraisal tools were design-specific [ 2 – 5 , 7 , 9 , 15 – 90 ], with over one third (N = 45) developed for experimental studies (randomized controlled trials, clinical trials) [ 2 – 4 , 25 – 27 , 34 , 37 – 73 ]. Sixteen critical appraisal tools were generic. Of these, six were developed for use on both experimental and observational studies [ 9 , 91 – 95 ], whereas 11 were purported to be useful for any qualitative and quantitative research design [ 1 , 18 , 41 , 96 – 102 , 116 ] (see Figure 1 , Table 1 ).

Number of critical appraisal tools per study design [1,2]

Critical appraisal items

One thousand, four hundred and seventy five items were extracted from these critical appraisal tools. After grouping like items together, 173 different item types were identified, with the most frequently reported items being focused towards assessing the external validity of the study (N = 35) and method of data analyses (N = 28) (Table 2 ). The most frequently reported items across all critical appraisal tools were:

Eligibility criteria (inclusion/exclusion criteria) (N = 63)

Appropriate statistical analyses (N = 47)

Random allocation of subjects (N = 43)

Consideration of outcome measures used (N = 43)

Sample size justification/power calculations (N = 39)

Study design reported (N = 36)

Assessor blinding (N = 36)

Design-specific critical appraisal tools

Systematic reviews.

Eighty-seven different items were extracted from the 26 critical appraisal tools, which were designed to evaluate the quality of systematic reviews. These critical appraisal tools frequently contained items regarding data analyses and issues of external validity (Tables 2 and 3 ).

Items assessing data analyses were focused to the methods used to summarize the results, assessment of sensitivity of results and whether heterogeneity was considered, whereas the nature of reporting of the main results, interpretation of them and their generalizability were frequently used to assess the external validity of the study findings. Moreover, systematic review critical appraisal tools tended to contain items such as identification of relevant studies, search strategy used, number of studies included and protocol adherence, that would not be relevant for other study designs. Blinding and randomisation procedures were rarely included in these critical appraisal tools.

Experimental studies

One hundred and twenty thirteen different items were extracted from the 45 experimental critical appraisal tools. These items most frequently assessed aspects of data analyses and blinding (Tables 1 and 2 ). Data analyses items were focused on whether appropriate statistical analysis was performed, whether a sample size justification or power calculation was provided and whether side effects of the intervention were recorded and analysed. Blinding was focused on whether the participant, clinician and assessor were blinded to the intervention.

Diagnostic studies

Forty-seven different items were extracted from the seven diagnostic critical appraisal tools. These items frequently addressed issues involving data analyses, external validity of results and sample selection that were specific to diagnostic studies (whether the diagnostic criteria were defined, definition of the "gold" standard, the calculation of sensitivity and specificity) (Tables 1 and 2 ).

Observational studies

Seventy-four different items were extracted from the 19 critical appraisal tools for observational studies. These items primarily focused on aspects of data analyses (see Tables 1 and 2 , such as whether confounders were considered in the analysis, whether a sample size justification or power calculation was provided and whether appropriate statistical analyses were preformed.

Qualitative studies

Thirty-six different items were extracted from the seven qualitative study critical appraisal tools. The majority of these items assessed issues regarding external validity, methods of data analyses and the aims and justification of the study (Tables 1 and 2 ). Specifically, items were focused to whether the study question was clearly stated, whether data analyses were clearly described and appropriate, and application of the study findings to the clinical setting. Qualitative critical appraisal tools did not contain items regarding sample selection, randomization, blinding, intervention or bias, perhaps because these issues are not relevant to the qualitative paradigm.

Generic critical appraisal tools

Experimental and observational studies.

Forty-two different items were extracted from the six critical appraisal tools that could be used to evaluate experimental and observational studies. These tools most frequently contained items that addressed aspects of sample selection (such as inclusion/exclusion criteria of participants, homogeneity of participants at baseline) and data analyses (such as whether appropriate statistical analyses were performed, whether a justification of the sample size or power calculation were provided).

All study designs

Seventy-eight different items were contained in the ten critical appraisal tools that could be used for all study designs (quantitative and qualitative). The majority of these items focused on whether appropriate data analyses were undertaken (such as whether confounders were considered in the analysis, whether a sample size justification or power calculation was provided and whether appropriate statistical analyses were preformed) and external validity issues (generalization of results to the population, value of the research findings) (see Tables 1 and 2 ).

Allied health critical appraisal tools

We found no critical appraisal instrument specific to allied health research, despite finding at least seven critical appraisal instruments associated with allied health topics (mostly physiotherapy management of orthopedic conditions) [ 37 , 39 , 52 , 58 , 59 , 65 ]. One critical appraisal development group proposed two instruments [ 9 ], specific to quantitative and qualitative research respectively. The core elements of allied health research quality (specific diagnosis criteria, intervention descriptions, nature of patient contact and appropriate outcome measures) were not addressed in any one tool sourced for this evaluation. We identified 152 different ways of considering quality reporting of outcome measures in the 121 critical appraisal tools, and 81 ways of considering description of interventions. Very few tools which were not specifically targeted to diagnostic studies (less than 10% of the remaining tools) addressed diagnostic criteria. The critical appraisal instrument that seemed most related to allied health research quality [ 39 ] sought comprehensive evaluation of elements of intervention and outcome, however this instrument was relevant only to physiotherapeutic orthopedic experimental research.

Overall study quality

Forty-nine percent (N = 58) of critical appraisal tools summarised the results of the quality appraisal into a single numeric summary score [ 5 , 7 , 15 – 25 , 37 – 59 , 74 – 77 , 80 – 83 , 87 , 91 – 93 , 96 , 97 ] (Figure 2 ). This was achieved by one of two methods:

Number of critical appraisal tools with, and without, summary quality scores

An equal weighting system, where one point was allocated to each item fulfilled; or

A weighted system, where fulfilled items were allocated various points depending on their perceived importance.

However, there was no justification provided for any of the scoring systems used. In the remaining critical appraisal tools (N = 62), a single numerical summary score was not provided [ 1 – 4 , 9 , 25 – 36 , 60 – 73 , 78 , 79 , 84 – 90 , 94 , 95 , 98 – 102 ]. This left the research consumer to summarize the results of the appraisal in a narrative manner, without the assistance of a standard approach.

Psychometric properties of critical appraisal tools

Few critical appraisal tools had documented evidence of their validity and reliability. Face validity was established in nine critical appraisal tools, seven of which were developed for use on experimental studies [ 38 , 40 , 45 , 49 , 51 , 63 , 70 ] and two for systematic reviews [ 32 , 103 ]. Intra-rater reliability was established for only one critical appraisal tool as part of its empirical development process [ 40 ], whereas inter-rater reliability was reported for two systematic review tools [ 20 , 36 ] (for one of these as part of the developmental process [ 20 ]) and seven experimental critical appraisal tools [ 38 , 40 , 45 , 51 , 55 , 56 , 63 ] (for two of these as part of the developmental process [ 40 , 51 ]).

Critical appraisal tool guidelines

Forty-three percent (N = 52) of critical appraisal tools had guidelines that informed the user of the interpretation of each item contained within them (Table 2 ). These guidelines were most frequently in the form of a handbook or published paper (N = 31) [ 2 , 4 , 9 , 15 , 20 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 36 , 37 , 41 , 50 , 64 – 67 , 69 , 80 , 84 – 87 , 89 , 90 , 95 , 100 , 116 ], whereas in 14 critical appraisal tools explanations accompanied each item [ 16 , 26 , 27 , 40 , 49 , 51 , 57 , 59 , 79 , 83 , 91 , 102 ].

Our search strategy identified a large number of published critical appraisal tools that are currently available to critically appraise research reports. There was a distinct lack of information on tool development processes in most cases. Many of the tools were reported to be modifications of other published tools, or reflected specialty concerns in specific clinical or research areas, without attempts to justify inclusion criteria. Less than 10 of these tools were relevant to evaluation of the quality of allied health research, and none of these were based on an empirical research approach. We are concerned that although our search was systematic and extensive [ 104 , 105 ], our broad key words and our lack of ready access to 29% of potentially useful papers (N = 56) potentially constrained us from identifying all published critical appraisal tools. However, consumers of research seeking critical appraisal instruments are not likely to seek instruments from outdated Internet links and unobtainable journals, thus we believe that we identified the most readily available instruments. Thus, despite the limitations on sourcing all possible tools, we believe that this paper presents a useful synthesis of the readily available critical appraisal tools.

The majority of the critical appraisal tools were developed for a specific research design (87%), with most designed for use on experimental studies (38% of all critical appraisal tools sourced). This finding is not surprising as, according to the medical model, experimental studies sit at or near the top of the hierarchy of evidence [ 2 , 8 ]. In recent years, allied health researchers have strived to apply the medical model of research to their own discipline by conducting experimental research, often by using the randomized controlled trial design [ 106 ]. This trend may be the reason for the development of experimental critical appraisal tools reported in allied health-specific research topics [ 37 , 39 , 52 , 58 , 59 , 65 ].

We also found a considerable number of critical appraisal tools for systematic reviews (N = 26), which reflects the trend to synthesize research evidence to make it relevant for clinicians [ 105 , 107 ]. Systematic review critical appraisal tools contained unique items (such as identification of relevant studies, search strategy used, number of studies included, protocol adherence) compared with tools used for primary studies, a reflection of the secondary nature of data synthesis and analysis.

In contrast, we identified very few qualitative study critical appraisal tools, despite the presence of many journal-specific guidelines that outline important methodological aspects required in a manuscript submitted for publication [ 108 – 110 ]. This finding may reflect the more traditional, quantitative focus of allied health research [ 111 ]. Alternatively, qualitative researchers may view the robustness of their research findings in different terms compared with quantitative researchers [ 112 , 113 ]. Hence the use of critical appraisal tools may be less appropriate for the qualitative paradigm. This requires further consideration.

Of the small number of generic critical appraisal tools, we found few that could be usefully applied (to any health research, and specifically to the allied health literature), because of the generalist nature of their items, variable interpretation (and applicability) of items across research designs, and/or lack of summary scores. Whilst these types of tools potentially facilitate the synthesis of evidence across allied health research designs for clinicians, their lack of specificity in asking the 'hard' questions about research quality related to research design also potentially precludes their adoption for allied health evidence-based practice. At present, the gold standard study design when synthesizing evidence is the randomized controlled trial [ 4 ], which underpins our finding that experimental critical appraisal tools predominated in the allied health literature [ 37 , 39 , 52 , 58 , 59 , 65 ]. However, as more systematic literature reviews are undertaken on allied health topics, it may become more accepted that evidence in the form of other research design types requires acknowledgement, evaluation and synthesis. This may result in the development of more appropriate and clinically useful allied health critical appraisal tools.

A major finding of our study was the volume and variation in available critical appraisal tools. We found no gold standard critical appraisal tool for any type of study design. Therefore, consumers of research are faced with frustrating decisions when attempting to select the most appropriate tool for their needs. Variable quality evaluations may be produced when different critical appraisal tools are used on the same literature [ 6 ]. Thus, interpretation of critical analysis must be carefully considered in light of the critical appraisal tool used.

The variability in the content of critical appraisal tools could be accounted for by the lack of any empirical basis of tool construction, established validity of item construction, and the lack of a gold standard against which to compare new critical tools. As such, consumers of research cannot be certain that the content of published critical appraisal tools reflect the most important aspects of the quality of studies that they assess [ 114 ]. Moreover, there was little evidence of intra- or inter-rater reliability of the critical appraisal tools. Coupled with the lack of protocols for use, this may mean that critical appraisers could interpret instrument items in different ways over repeated occasions of use. This may produce variable results [123].

Based on the findings of this evaluation, we recommend that consumers of research should carefully select critical appraisal tools for their needs. The selected tools should have published evidence of the empirical basis for their construction, validity of items and reliability of interpretation, as well as guidelines for use, so that the tools can be applied and interpreted in a standardized manner. Our findings highlight the need for consensus to be reached regarding the important and core items for critical appraisal tools that will produce a more standardized environment for critical appraisal of research evidence. As a consequence, allied health research will specifically benefit from having critical appraisal tools that reflect best practice research approaches which embed specific research requirements of allied health disciplines.

National Health and Medical Research Council: How to Review the Evidence: Systematic Identification and Review of the Scientific Literature. Canberra. 2000

Google Scholar

National Health and Medical Research Council: How to Use the Evidence: Assessment and Application of Scientific Evidence. Canberra. 2000

Joanna Briggs Institute. [ http://www.joannabriggs.edu.au ]

Clarke M, Oxman AD: Cochrane Reviewer's Handbook 4.2.0. 2003, Oxford: The Cochrane Collaboration

Crombie IK: The Pocket Guide to Critical Appraisal: A Handbook for Health Care Professionals. 1996, London: BMJ Publishing Group

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Systems to Rate the Strength of Scientific Evidence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 47, Publication No. 02-E016. Rockville. 2002

Elwood JM: Critical Appraisal of Epidemiological Studies and Clinical Trials. 1998, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2

Sackett DL, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB: Evidence Based Medicine. How to Practice and Teach EBM. 2000, London: Churchill Livingstone

Critical literature reviews. [ http://www.cotfcanada.org/cotf_critical.htm ]

Bialocerkowski AE, Grimmer KA, Milanese SF, Kumar S: Application of current research evidence to clinical physiotherapy practice. J Allied Health Res Dec.

The National Health Data Dictionary – Version 10. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/hwi/nhdd12/nhdd12-v1.pdf and http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/hwi/nhdd12/nhdd12-v2.pdf