Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) for Outpatients With Borderline Personality Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial and 1-Year Follow-Up

Information & authors, metrics & citations, view options, assessments, treatment assignment, stepps program.

Treatment as Usual

Statistical analysis.

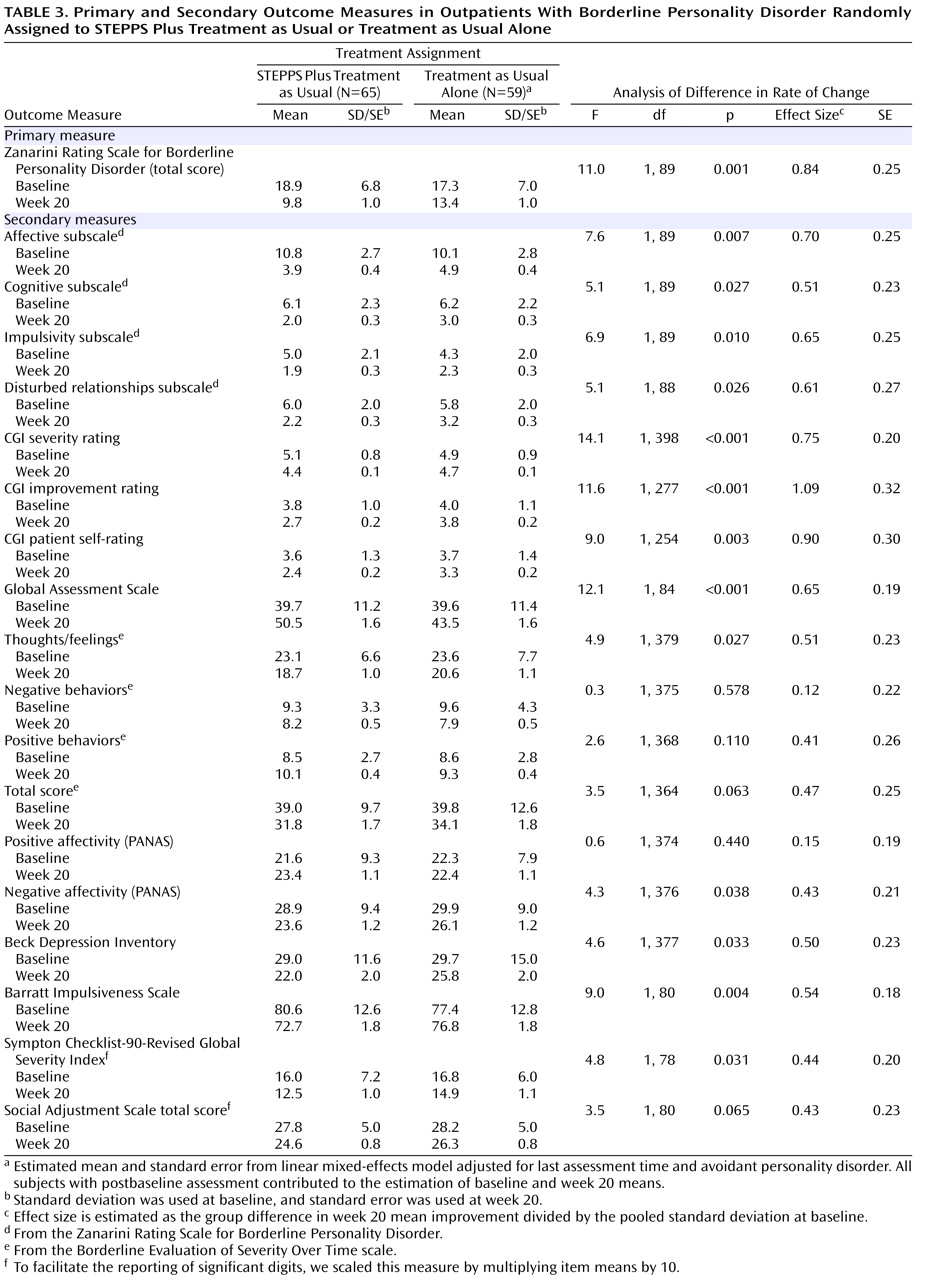

Assessment of Efficacy: Treatment Period

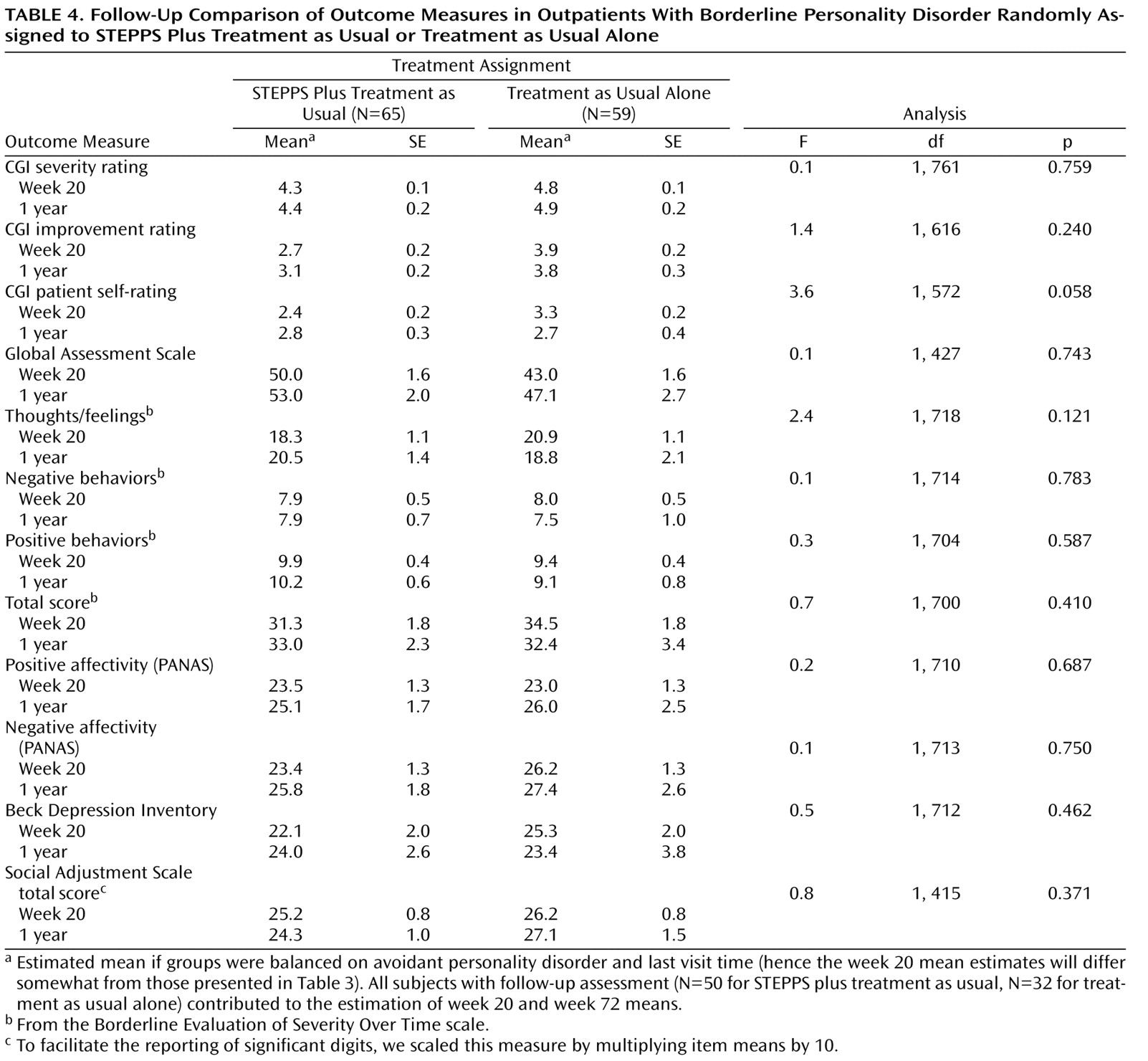

Assessment of Efficacy: 1-Year Follow-Up

Medication and Individual Psychotherapy

Indirect indicators of efficacy.

Information

Published in.

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download. For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu .

| Format | |

|---|---|

| Citation style | |

| Style | |

View options

Login options.

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Purchase Options

Purchase this article to access the full text.

PPV Articles - American Journal of Psychiatry

Not a subscriber?

Subscribe Now / Learn More

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR ® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).

Share article link

Copying failed.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

Next article, request username.

Can't sign in? Forgot your username? Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Create a new account

Change password, password changed successfully.

Your password has been changed

Reset password

Can't sign in? Forgot your password?

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password.

Your Phone has been verified

As described within the American Psychiatric Association (APA)'s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences. Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS)

- First Online: 01 January 2014

Cite this chapter

- Renee Harvey 3 ,

- Nancee Blum 4 , 5 ,

- Donald W. Black 4 , 5 ,

- Jo Burgess 6 &

- Paula Henley-Cragg 7

6634 Accesses

2 Citations

STEPPS (Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving) is a manualized, cognitive-behavioral, skills-based group treatment program originally developed in the USA for adults with borderline personality disorder (BPD) (Black, Blum, Pfohl, & St. John, 2004, 2012; Blum, Bartels, St. John, & Pfohl, 2002); the manual was also adapted for use in the UK (Blum, Bartels, St. John, & Pfohl, 2009), and the program is widely used in the Netherlands under the title VERS (Van Wel et al., 2006). The program is evidence based, as designated by the National Registry for Evidence-Based Practices (NREPP 2012). Although it was originally conceptualized as an outpatient program, STEPPS has been successfully adapted and implemented in a variety of settings, including inpatient units, partial hospital, day treatment programs, residential treatment facilities, substance abuse treatment, and correctional settings, including both male and female offenders in prisons and community corrections. In this chapter, an adaptation of STEPPS for adolescents in the UK will be described.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Battles of the Comfort Zone: Modelling Therapeutic Strategy, Alliance, and Epistemic Trust—A Qualitative Study of Mentalization-Based Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder

Advancing the treatment of long-lasting borderline personality disorder: a feasibility and acceptability study of an expanded DBT-based skills intervention

The effects of on-line systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving (stepps) on impulsivity and self-destructive behaviors of women with borderline personality disorder.

American Psychiatric Association, (2004). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th Ed. Text Revision) (DSM-IV-TR). Arlington: American Psychiatric Press.

Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th Ed.) (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Black, D. W., Blum, N., McCormick, B., & Allen, J. (2013). Systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving (STEPPS) group treatment for offenders with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 201 , 1–6.

Black, D. W., Blum, N., Eichinger, L., McCormick, B., Allen, J., & Sieleni, B. (2008). STEPPS: Systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving in women offenders with borderline personality disorder in prison—A pilot study. CNS Spectrums, 13 , 881–886.

PubMed Google Scholar

Black, D. W., Blum, N., Pfohl, B., & St. John, D. (2004). The STEPPS Group Treatment Program for Outpatients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 34 , 193–210.

Article Google Scholar

Blum, N. S., Bartels, N. E, St. John, D., & Pfohl, B. (2009). Systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving (STEPPS UK): Group treatment program for borderline personality disorder. Coralville, IA: Level One Publishing (Blums Books). Retrieved from www.steppsforbpd.com

Blum, N. S., Bartels, N. E, St. John, D., & Pfohl, B. (2012). Systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving (STEPPS second edition): Group treatment program for borderline personality disorder . Coralville, IA: Level One Publishing (Blums Books). Retrieved from www.steppsforbpd.com

Blum, N., Bartels, N., St. John, D., & Pfohl, B. (2002). STEPPS: Systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving: group treatment for borderline personality disorder . Coralville, IA: Blum’s Books.

Blum, N., Pfohl, B., St. John, D., Monahan, P., & Black, D. W. (2002). STEPPS: A cognitive behavioral systems-based group treatment for outpatients with borderline personality disorder—A preliminary report. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 43 , 301–310.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Blum, N., & St. John, D. (2008) . STAIRWAYS—The next step in treatment for borderline personality disorder . Coralville, IA: Level One Publishing (Blums Books). Retrieved from www.steppsforbpdcom

Blum, N., St. John, D., Pfohl, B., Stuart, S., McCormick, B., Allen, J., et al. (2008). Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial and 1-year follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165 , 468–478.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Boccalon, S., Alesiani, R., Giarolli, L., Franchini, C., Columbo, C., Blum, N., et al. (2012). Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS): theoretical model, clinical applications and preliminary efficacy data in a sample of inpatients with personality disorders in comorbidity with mood disorders. Giornale di Psicopatologia . Retrieved from www.jpsychopathol.net

Freije, H., Dietz, B., & Appelo, M. (2002). Behandeling van de borderline persoonlijkheidsstoornis met de Vers: de Vaardigheidstraining emotionele regulatiestoornis. Directive Therapies, 4 , 367–378.

Harvey, R., Black, D. W., & Blum, N. (2010). Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) in the United Kingdom: A preliminary report. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 40 , 225–232.

Linehan, M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder . New York: Guilford.

Schuppert, H. M., Giesen-Bloo, J., van Gemert, T. G., Wiersema, H. M., Minderaa, R. B., Emmelkamp, P. M., et al. (2009). Effectiveness of an emotion regulation group training for adolescents—A randomized controlled pilot study. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy., 16 (6), 467.

Millon, T., Millon, C., Davis, R., & Grossman, S. (1993/2006). The Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory (MACI™). Pearson. Retrieved from http://www.pearsonassessments.com/HAIWEB/Cultures/en-us/Productdetail.htm?Pid=PAg501

Pfohl, B., Blum, N., McCormick, B., St. John, D., Allen, J., & Black, D. W. (2009). Reliability and validity of the borderline evaluation of severity over time: A new scale to measure severity and change in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 23 , 281–293.

Sperry, L. (2003). Handbook of diagnosis and treatment of DSM-IV-TR personality disorders (2nd ed.). New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Van Wel, B., Bos, E. H., Appelo, M. T., Berendsen, E. M., Willgeroth, F. C., & Verbraak, M. J. P. M. (2009). De effectiviteit van de vaardigheidstraining Emotieregulatiestoornis (VERS) in de behandeling van de Borderlinepersoonlijkheidsstoornis; een gerandomiseerd onderzoek. Tijdschrift voor psychiatrie, 51 , 5.

Van Wel, B., Kockmann, I., Blum, N., Pfohl, B., Black, D. W., & Heesterman, W. (2006). STEPPS group treatment for borderline personality disorder in The Netherlands. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 18 , 63–67.

Yeomans, F. E., Gutfreund, J., Selzer, M. A., Clarkin, J. F., Hull, J. W., & Smith, T. E. (1994). Factors related to drop-outs by borderline patients. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 3 , 16–24.

PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Suggested Reading

Blum, N., & Black, D. W. (2008). The STEPPS group treatment for borderline personality disorder. In P. D. Hoffman, & P. Steiner-Grossman (Eds.), Borderline personality disorder: meeting the challenges to successful treatment (published simultaneously as Social Work in Mental Health 2008, 6, 171–186). Binghampton, NY: The Haworth Press.

Blum, N., & Pfohl, B. (2006). Volatile Vivian (Borderline Personality Disorder). In R. Spitzer, J. Williams, M. Gibbon, & M. First (Eds.), DSM-IV-TR treatment casebook: Experts tell how they treated their patients (pp. 391–402). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Dowrick, C., Blum, N., & Pfohl, B. (2008). Psychoeducational treatments. In: P. Tyrer, & K. Silk (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of effective treatments in psychiatry (pp. 116–131). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Download references

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Charlotte Wilcox, Research Assistant, Group co-facilitators Jude Jarrett (Clinical Psychologist) and Tansy Walker (Clinical Psychologist), and Stephanie Field who provided administrative support.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Bluebell House, Recovery Support Centre, Royal George Road, Burgess Hill, RH15 9NZ, West Sussex, Great Britain

Renee Harvey

Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, IA, USA

Nancee Blum & Donald W. Black

Iowa Department of Corrections, Des Moines, IA, USA

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service, Sussex Partnership NHs Foundation Trust, Burgess Hill, West Sussex, Great Britain

Worthing Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service, Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, Burgess Hill, West Sussex, Great Britain

Paula Henley-Cragg

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Renee Harvey .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Dept. Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, Texas, USA

Carla Sharp

Jennifer L. Tackett

Appendix: A “Typical” STEPPS Lesson

Every STEPPS lesson is structured according to an agenda, which is handed out with the notes. The agendas are all broadly similar. This provides a predicable pattern, which helps the participant to feel less anxious and enables them to concentrate on the new material being presented each week.

Described here is Lesson 10, which is the first of two on “Managing Problems.” By this stage, the participant has been introduced to the concept of emotional intensity difficulties (as an alternative to a diagnosis of BPD) and has been given a series of emotion management skills to underpin the work on behavior change to follow (See Chap. 27 for a description of these). Comments in square brackets explain the process.

Complete a QuEST scale and record the score [Symptom measure which is done weekly]

Relaxation [A brief relaxation session, each week introducing a different method so that participants have a choice]

Review EIC [Here there is an opportunity for participants to describe how the past week has been, and for the group to share how they have filled in the 5-point EIC form relative to any incidents they experienced. There is usually an example done in the lesson on the whiteboard, with all encouraged to comment, make suggestions, and share their own responses.]

Review Skills Monitoring Card [Participants have been encouraged to use a tick list of skills every day.]

Review of homework exercises from the previous week.

Presentation of the week’s lesson and homework exercises.

In the Managing Problems lesson, participants begin with problem identification and potential solution strategies, but with particular attention paid to understanding the role of “filters” (schemas/core beliefs) in contributing to the intensity of their reactions and the obstacles in their way. All the skills learned so far are brought to bear in understanding how they might find a possible solution and how to overcome resistances and self-sabotaging which may have played a role in past failures. The group contributes by making suggestions, encouraging each other, and sharing experiences of what has been helpful for them. In the lessons to come, feedback from each of the previous lesson is used to build the skills of the next.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Harvey, R., Blum, N., Black, D.W., Burgess, J., Henley-Cragg, P. (2014). Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS). In: Sharp, C., Tackett, J. (eds) Handbook of Borderline Personality Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-0591-1_26

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-0591-1_26

Published : 28 March 2014

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4939-0590-4

Online ISBN : 978-1-4939-0591-1

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving in older adults with personality disorders: a pilot study

Affiliations.

- 1 PersonaCura, Clinical Center of Excellence for Personality Disorders and Autism in Older Adults, GGz Breburg, Tilburg, The Netherlands.

- 2 Tranzo, Scientific Centre for Care and Wellbeing of the Tilburg School of Social and Behavioral Sciences of Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands.

- 3 Clinical Center of Excellence for Personality Disorders in Older Adults, Mondriaan Mental Health Center, Heerlen-Maastricht, The Netherlands.

- 4 Personality and Psychopathology research group (PEPS), Department of Psychology (PE), Vrije Universiteit Brussels (VUB), Brussels, Belgium.

- 5 Department of Medical and Clinical Psychology, Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands.

- PMID: 36258278

- DOI: 10.1017/S1352465822000443

Background: Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) is a cognitive behavioural therapy-based group treatment programme for patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD). STEPPS has demonstrated its effectiveness for (younger) adults. However, there are no studies into the effects of STEPPS for older adults.

Aim: The aim was to explore the outcome of STEPPS in older adults with personality disorders.

Method: In this naturalistic pre- vs post-treatment study, older patients with a personality disorder, reporting emotion regulation difficulties, were included. The primary outcome was BPD symptoms. Secondary outcomes included psychological distress and maladaptive personality functioning.

Results: Twenty-four patients, with a mean age of 63.9 years ( SD =4.6), completed the 19-week programme. Nine patients (23.1%) did not complete the treatment. There were no significant differences in age, gender or global severity between completers and patients dropping out. There was a significant pre- vs post-treatment decrease of BPD symptoms, with a large effect size (Cohen's d =1.577). Self-control improved significantly and demonstrated a large effect size ( r =.576). Furthermore, identity integration improved significantly, with a medium effect size (Cohen's d =.509). No significant differences were reported for most domains of psychological distress and maladaptive interpersonal personality functioning.

Conclusions: The findings in this pilot study suggest STEPPS is a feasible treatment programme for older adults with personality disorders and emotion regulation difficulties. Adaptations to the program, for a better fit for older adults, however, might be needed.

Keywords: STEPPS; borderline personality disorder; emotion regulation; older adults.

PubMed Disclaimer

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Cambridge University Press

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) is a group treatment program for patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD). The program was intended to be highly accessible, both for patients and therapists.

STEPPS (Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving) is a manualized, cognitive-behavioral, skills-based group treatment program originally developed in the USA for adults with borderline personality disorder (BPD) (Black, Blum, Pfohl, & St....

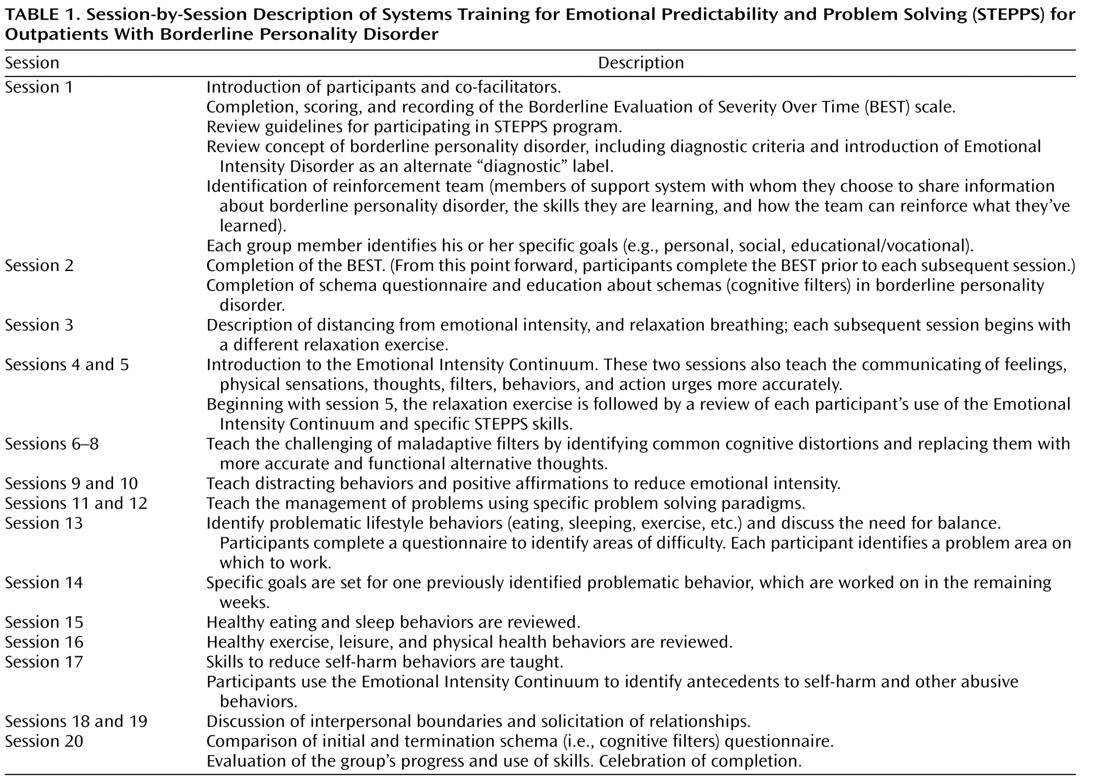

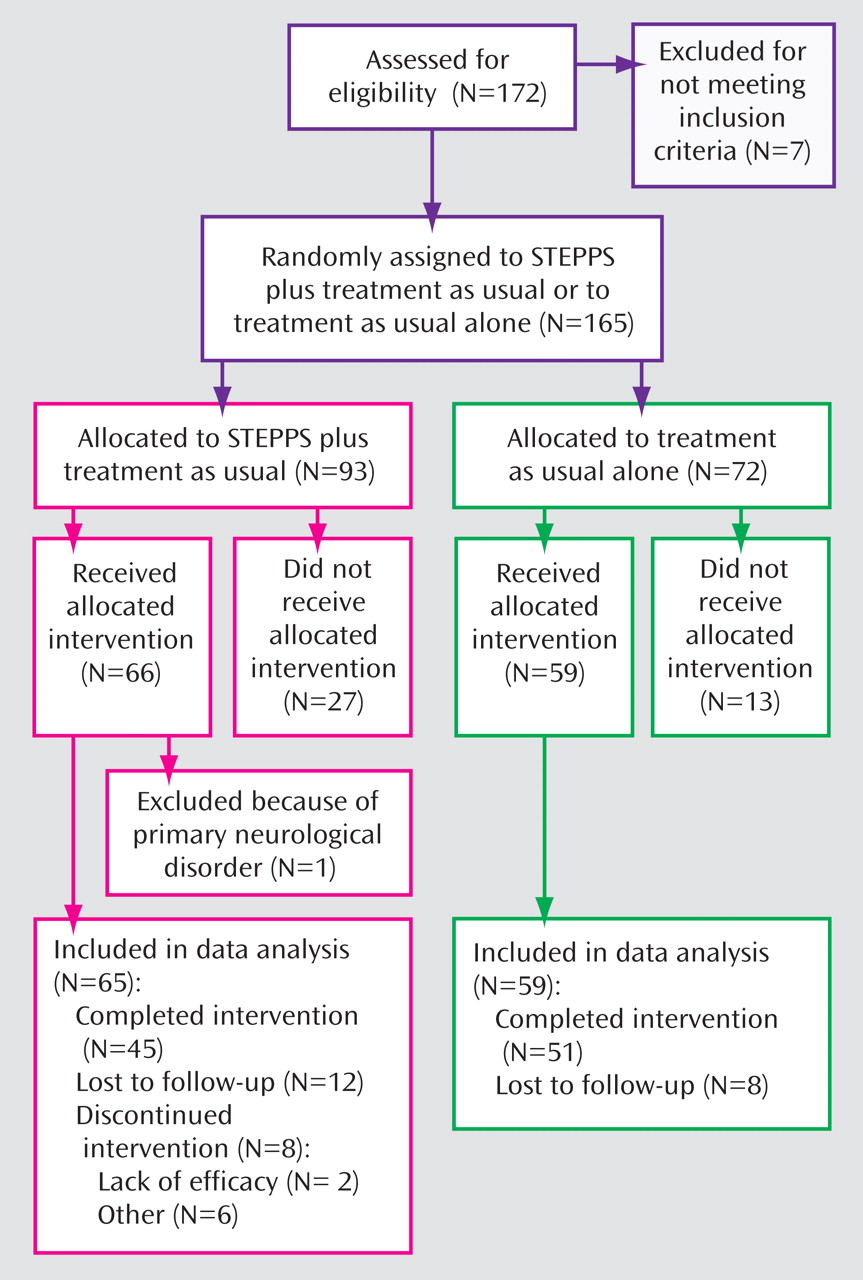

Objective: Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) is a 20-week manual-based group treatment program for outpatients with borderline personality disorder that combines cognitive behavioral elements and skills training with a systems component.

Nancee Blum, Donald W. Black, Jo Burgess, and Paula Henley-CraggIntroductionSTEPPS (Systems Training for Emotional Pre-dictability and Problem Solving) is a manualized, cognitive-behavioral, skills-based group treat-ment program originally developed in the USA for adults with borderline personality disorder (BPD) (Black, Blum, Pfohl, & St. John ...

Background: Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) is a cognitive behavioural therapy-based group treatment programme for patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD). STEPPS has demonstrated its effectiveness for (younger) adults.

Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS; Blum et al., 2002) is a manualized, cognitive behavioural therapy-based group treatment programme for patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD). STEPPS is based on the premise that patients with BPD lack skills to deal with their emotion instability.