Home > Blog > Tips for Online Students > Why Is Critical Thinking Important and How to Improve It

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

Why Is Critical Thinking Important and How to Improve It

Updated: July 8, 2024

Published: April 2, 2020

In this article

Why is critical thinking important? The decisions that you make affect your quality of life. And if you want to ensure that you live your best, most successful and happy life, you’re going to want to make conscious choices. That can be done with a simple thing known as critical thinking. Here’s how to improve your critical thinking skills and make decisions that you won’t regret.

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is the process of analyzing facts to form a judgment. Essentially, it involves thinking about thinking. Historically, it dates back to the teachings of Socrates , as documented by Plato.

Today, it is seen as a complex concept understood best by philosophers and psychologists. Modern definitions include “reasonable, reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do” and “deciding what’s true and what you should do.”

The Importance Of Critical Thinking

Why is critical thinking important? Good question! Here are a few undeniable reasons why it’s crucial to have these skills.

1. Critical Thinking Is Universal

Critical thinking is a domain-general thinking skill. What does this mean? It means that no matter what path or profession you pursue, these skills will always be relevant and will always be beneficial to your success. They are not specific to any field.

2. Crucial For The Economy

Our future depends on technology, information, and innovation. Critical thinking is needed for our fast-growing economies, to solve problems as quickly and as effectively as possible.

3. Improves Language & Presentation Skills

In order to best express ourselves, we need to know how to think clearly and systematically — meaning practice critical thinking! Critical thinking also means knowing how to break down texts, and in turn, improve our ability to comprehend.

4. Promotes Creativity

By practicing critical thinking, we are allowing ourselves not only to solve problems but also to come up with new and creative ideas to do so. Critical thinking allows us to analyze these ideas and adjust them accordingly.

5. Important For Self-Reflection

Without critical thinking, how can we really live a meaningful life? We need this skill to self-reflect and justify our ways of life and opinions. Critical thinking provides us with the tools to evaluate ourselves in the way that we need to.

Photo by Marcelo Chagas from Pexels

6. the basis of science & democracy.

In order to have a democracy and to prove scientific facts, we need critical thinking in the world. Theories must be backed up with knowledge. In order for a society to effectively function, its citizens need to establish opinions about what’s right and wrong (by using critical thinking!).

Benefits Of Critical Thinking

We know that critical thinking is good for society as a whole, but what are some benefits of critical thinking on an individual level? Why is critical thinking important for us?

1. Key For Career Success

Critical thinking is crucial for many career paths. Not just for scientists, but lawyers , doctors, reporters, engineers , accountants, and analysts (among many others) all have to use critical thinking in their positions. In fact, according to the World Economic Forum, critical thinking is one of the most desirable skills to have in the workforce, as it helps analyze information, think outside the box, solve problems with innovative solutions, and plan systematically.

2. Better Decision Making

There’s no doubt about it — critical thinkers make the best choices. Critical thinking helps us deal with everyday problems as they come our way, and very often this thought process is even done subconsciously. It helps us think independently and trust our gut feeling.

3. Can Make You Happier!

While this often goes unnoticed, being in touch with yourself and having a deep understanding of why you think the way you think can really make you happier. Critical thinking can help you better understand yourself, and in turn, help you avoid any kind of negative or limiting beliefs, and focus more on your strengths. Being able to share your thoughts can increase your quality of life.

4. Form Well-Informed Opinions

There is no shortage of information coming at us from all angles. And that’s exactly why we need to use our critical thinking skills and decide for ourselves what to believe. Critical thinking allows us to ensure that our opinions are based on the facts, and help us sort through all that extra noise.

5. Better Citizens

One of the most inspiring critical thinking quotes is by former US president Thomas Jefferson: “An educated citizenry is a vital requisite for our survival as a free people.” What Jefferson is stressing to us here is that critical thinkers make better citizens, as they are able to see the entire picture without getting sucked into biases and propaganda.

6. Improves Relationships

While you may be convinced that being a critical thinker is bound to cause you problems in relationships, this really couldn’t be less true! Being a critical thinker can allow you to better understand the perspective of others, and can help you become more open-minded towards different views.

7. Promotes Curiosity

Critical thinkers are constantly curious about all kinds of things in life, and tend to have a wide range of interests. Critical thinking means constantly asking questions and wanting to know more, about why, what, who, where, when, and everything else that can help them make sense of a situation or concept, never taking anything at face value.

8. Allows For Creativity

Critical thinkers are also highly creative thinkers, and see themselves as limitless when it comes to possibilities. They are constantly looking to take things further, which is crucial in the workforce.

9. Enhances Problem Solving Skills

Those with critical thinking skills tend to solve problems as part of their natural instinct. Critical thinkers are patient and committed to solving the problem, similar to Albert Einstein, one of the best critical thinking examples, who said “It’s not that I’m so smart; it’s just that I stay with problems longer.” Critical thinkers’ enhanced problem-solving skills makes them better at their jobs and better at solving the world’s biggest problems. Like Einstein, they have the potential to literally change the world.

10. An Activity For The Mind

Just like our muscles, in order for them to be strong, our mind also needs to be exercised and challenged. It’s safe to say that critical thinking is almost like an activity for the mind — and it needs to be practiced. Critical thinking encourages the development of many crucial skills such as logical thinking, decision making, and open-mindness.

11. Creates Independence

When we think critically, we think on our own as we trust ourselves more. Critical thinking is key to creating independence, and encouraging students to make their own decisions and form their own opinions.

12. Crucial Life Skill

Critical thinking is crucial not just for learning, but for life overall! Education isn’t just a way to prepare ourselves for life, but it’s pretty much life itself. Learning is a lifelong process that we go through each and every day.

How To Improve Your Critical Thinking

Now that you know the benefits of thinking critically, how do you actually do it?

- Define Your Question: When it comes to critical thinking, it’s important to always keep your goal in mind. Know what you’re trying to achieve, and then figure out how to best get there.

- Gather Reliable Information: Make sure that you’re using sources you can trust — biases aside. That’s how a real critical thinker operates!

- Ask The Right Questions: We all know the importance of questions, but be sure that you’re asking the right questions that are going to get you to your answer.

- Look Short & Long Term: When coming up with solutions, think about both the short- and long-term consequences. Both of them are significant in the equation.

- Explore All Sides: There is never just one simple answer, and nothing is black or white. Explore all options and think outside of the box before you come to any conclusions.

How Is Critical Thinking Developed At School?

Critical thinking is developed in nearly everything we do, but much of this essential skill is encouraged and practiced in school. Fostering a culture of inquiry is crucial, encouraging students to ask questions, analyze information, and evaluate evidence.

Teaching strategies like Socratic questioning, problem-based learning, and collaborative discussions help students think for themselves. When teachers ask questions, students can respond critically and reflect on their learning. Group discussions also expand their thinking, making them independent thinkers and effective problem solvers.

How Does Critical Thinking Apply To Your Career?

Critical thinking is a valuable asset in any career. Employers value employees who can think critically, ask insightful questions, and offer creative solutions. Demonstrating critical thinking skills can set you apart in the workplace, showing your ability to tackle complex problems and make informed decisions.

In many careers, from law and medicine to business and engineering, critical thinking is essential. Lawyers analyze cases, doctors diagnose patients, business analysts evaluate market trends, and engineers solve technical issues—all requiring strong critical thinking skills.

Critical thinking also enhances your ability to communicate effectively, making you a better team member and leader. By analyzing and evaluating information, you can present clear, logical arguments and make persuasive presentations.

Incorporating critical thinking into your career helps you stay adaptable and innovative. It encourages continuous learning and improvement, which are crucial for professional growth and success in a rapidly changing job market.

Photo by Oladimeji Ajegbile from Pexels

Critical thinking is a vital skill with far-reaching benefits for personal and professional success. It involves systematic skills such as analysis, evaluation, inference, interpretation, and explanation to assess information and arguments.

By gathering relevant data, considering alternative perspectives, and using logical reasoning, critical thinking enables informed decision-making. Reflecting on and refining these processes further enhances their effectiveness.

The future of critical thinking holds significant importance as it remains essential for adapting to evolving challenges and making sound decisions in various aspects of life.

What are the benefits of developing critical thinking skills?

Critical thinking enhances decision-making, problem-solving, and the ability to evaluate information critically. It helps in making informed decisions, understanding others’ perspectives, and improving overall cognitive abilities.

How does critical thinking contribute to problem-solving abilities?

Critical thinking enables you to analyze problems thoroughly, consider multiple solutions, and choose the most effective approach. It fosters creativity and innovative thinking in finding solutions.

What role does critical thinking play in academic success?

Critical thinking is crucial in academics as it allows you to analyze texts, evaluate evidence, construct logical arguments, and understand complex concepts, leading to better academic performance.

How does critical thinking promote effective communication skills?

Critical thinking helps you articulate thoughts clearly, listen actively, and engage in meaningful discussions. It improves your ability to argue logically and understand different viewpoints.

How can critical thinking skills be applied in everyday situations?

You can use critical thinking to make better personal and professional decisions, solve everyday problems efficiently, and understand the world around you more deeply.

What role does skepticism play in critical thinking?

Skepticism encourages questioning assumptions, evaluating evidence, and distinguishing between facts and opinions. It helps in developing a more rigorous and open-minded approach to thinking.

What strategies can enhance critical thinking?

Strategies include asking probing questions, engaging in reflective thinking, practicing problem-solving, seeking diverse perspectives, and analyzing information critically and logically.

At UoPeople, our blog writers are thinkers, researchers, and experts dedicated to curating articles relevant to our mission: making higher education accessible to everyone. Read More

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 11 January 2023

The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving in promoting students’ critical thinking: A meta-analysis based on empirical literature

- Enwei Xu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6424-8169 1 ,

- Wei Wang 1 &

- Qingxia Wang 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 16 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

25k Accesses

26 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely embraced in the classroom instruction of critical thinking, which is regarded as the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education as well as a key competence for learners in the 21st century. However, the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking remains uncertain. This current research presents the major findings of a meta-analysis of 36 pieces of the literature revealed in worldwide educational periodicals during the 21st century to identify the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and to determine, based on evidence, whether and to what extent collaborative problem solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. The findings show that (1) collaborative problem solving is an effective teaching approach to foster students’ critical thinking, with a significant overall effect size (ES = 0.82, z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]); (2) in respect to the dimensions of critical thinking, collaborative problem solving can significantly and successfully enhance students’ attitudinal tendencies (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.87, 1.47]); nevertheless, it falls short in terms of improving students’ cognitive skills, having only an upper-middle impact (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.58, 0.82]); and (3) the teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), and learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01) all have an impact on critical thinking, and they can be viewed as important moderating factors that affect how critical thinking develops. On the basis of these results, recommendations are made for further study and instruction to better support students’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Similar content being viewed by others

A meta-analysis of the effects of design thinking on student learning

Fostering twenty-first century skills among primary school students through math project-based learning

A meta-analysis to gauge the impact of pedagogies employed in mixed-ability high school biology classrooms

Introduction.

Although critical thinking has a long history in research, the concept of critical thinking, which is regarded as an essential competence for learners in the 21st century, has recently attracted more attention from researchers and teaching practitioners (National Research Council, 2012 ). Critical thinking should be the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education (Peng and Deng, 2017 ) because students with critical thinking can not only understand the meaning of knowledge but also effectively solve practical problems in real life even after knowledge is forgotten (Kek and Huijser, 2011 ). The definition of critical thinking is not universal (Ennis, 1989 ; Castle, 2009 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). In general, the definition of critical thinking is a self-aware and self-regulated thought process (Facione, 1990 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). It refers to the cognitive skills needed to interpret, analyze, synthesize, reason, and evaluate information as well as the attitudinal tendency to apply these abilities (Halpern, 2001 ). The view that critical thinking can be taught and learned through curriculum teaching has been widely supported by many researchers (e.g., Kuncel, 2011 ; Leng and Lu, 2020 ), leading to educators’ efforts to foster it among students. In the field of teaching practice, there are three types of courses for teaching critical thinking (Ennis, 1989 ). The first is an independent curriculum in which critical thinking is taught and cultivated without involving the knowledge of specific disciplines; the second is an integrated curriculum in which critical thinking is integrated into the teaching of other disciplines as a clear teaching goal; and the third is a mixed curriculum in which critical thinking is taught in parallel to the teaching of other disciplines for mixed teaching training. Furthermore, numerous measuring tools have been developed by researchers and educators to measure critical thinking in the context of teaching practice. These include standardized measurement tools, such as WGCTA, CCTST, CCTT, and CCTDI, which have been verified by repeated experiments and are considered effective and reliable by international scholars (Facione and Facione, 1992 ). In short, descriptions of critical thinking, including its two dimensions of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, different types of teaching courses, and standardized measurement tools provide a complex normative framework for understanding, teaching, and evaluating critical thinking.

Cultivating critical thinking in curriculum teaching can start with a problem, and one of the most popular critical thinking instructional approaches is problem-based learning (Liu et al., 2020 ). Duch et al. ( 2001 ) noted that problem-based learning in group collaboration is progressive active learning, which can improve students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Collaborative problem-solving is the organic integration of collaborative learning and problem-based learning, which takes learners as the center of the learning process and uses problems with poor structure in real-world situations as the starting point for the learning process (Liang et al., 2017 ). Students learn the knowledge needed to solve problems in a collaborative group, reach a consensus on problems in the field, and form solutions through social cooperation methods, such as dialogue, interpretation, questioning, debate, negotiation, and reflection, thus promoting the development of learners’ domain knowledge and critical thinking (Cindy, 2004 ; Liang et al., 2017 ).

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely used in the teaching practice of critical thinking, and several studies have attempted to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature on critical thinking from various perspectives. However, little attention has been paid to the impact of collaborative problem-solving on critical thinking. Therefore, the best approach for developing and enhancing critical thinking throughout collaborative problem-solving is to examine how to implement critical thinking instruction; however, this issue is still unexplored, which means that many teachers are incapable of better instructing critical thinking (Leng and Lu, 2020 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). For example, Huber ( 2016 ) provided the meta-analysis findings of 71 publications on gaining critical thinking over various time frames in college with the aim of determining whether critical thinking was truly teachable. These authors found that learners significantly improve their critical thinking while in college and that critical thinking differs with factors such as teaching strategies, intervention duration, subject area, and teaching type. The usefulness of collaborative problem-solving in fostering students’ critical thinking, however, was not determined by this study, nor did it reveal whether there existed significant variations among the different elements. A meta-analysis of 31 pieces of educational literature was conducted by Liu et al. ( 2020 ) to assess the impact of problem-solving on college students’ critical thinking. These authors found that problem-solving could promote the development of critical thinking among college students and proposed establishing a reasonable group structure for problem-solving in a follow-up study to improve students’ critical thinking. Additionally, previous empirical studies have reached inconclusive and even contradictory conclusions about whether and to what extent collaborative problem-solving increases or decreases critical thinking levels. As an illustration, Yang et al. ( 2008 ) carried out an experiment on the integrated curriculum teaching of college students based on a web bulletin board with the goal of fostering participants’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These authors’ research revealed that through sharing, debating, examining, and reflecting on various experiences and ideas, collaborative problem-solving can considerably enhance students’ critical thinking in real-life problem situations. In contrast, collaborative problem-solving had a positive impact on learners’ interaction and could improve learning interest and motivation but could not significantly improve students’ critical thinking when compared to traditional classroom teaching, according to research by Naber and Wyatt ( 2014 ) and Sendag and Odabasi ( 2009 ) on undergraduate and high school students, respectively.

The above studies show that there is inconsistency regarding the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking. Therefore, it is essential to conduct a thorough and trustworthy review to detect and decide whether and to what degree collaborative problem-solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. Meta-analysis is a quantitative analysis approach that is utilized to examine quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. This approach characterizes the effectiveness of its impact by averaging the effect sizes of numerous qualitative studies in an effort to reduce the uncertainty brought on by independent research and produce more conclusive findings (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ).

This paper used a meta-analytic approach and carried out a meta-analysis to examine the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking in order to make a contribution to both research and practice. The following research questions were addressed by this meta-analysis:

What is the overall effect size of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and its impact on the two dimensions of critical thinking (i.e., attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills)?

How are the disparities between the study conclusions impacted by various moderating variables if the impacts of various experimental designs in the included studies are heterogeneous?

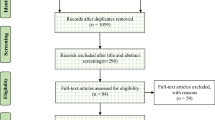

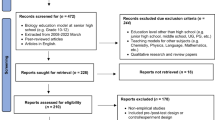

This research followed the strict procedures (e.g., database searching, identification, screening, eligibility, merging, duplicate removal, and analysis of included studies) of Cooper’s ( 2010 ) proposed meta-analysis approach for examining quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. The relevant empirical research that appeared in worldwide educational periodicals within the 21st century was subjected to this meta-analysis using Rev-Man 5.4. The consistency of the data extracted separately by two researchers was tested using Cohen’s kappa coefficient, and a publication bias test and a heterogeneity test were run on the sample data to ascertain the quality of this meta-analysis.

Data sources and search strategies

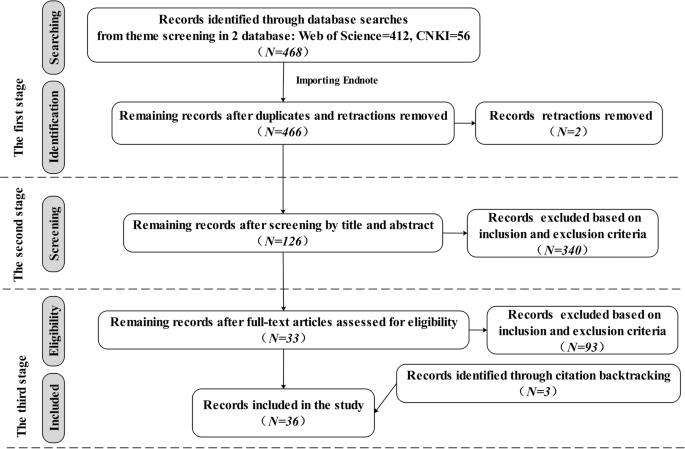

There were three stages to the data collection process for this meta-analysis, as shown in Fig. 1 , which shows the number of articles included and eliminated during the selection process based on the statement and study eligibility criteria.

This flowchart shows the number of records identified, included and excluded in the article.

First, the databases used to systematically search for relevant articles were the journal papers of the Web of Science Core Collection and the Chinese Core source journal, as well as the Chinese Social Science Citation Index (CSSCI) source journal papers included in CNKI. These databases were selected because they are credible platforms that are sources of scholarly and peer-reviewed information with advanced search tools and contain literature relevant to the subject of our topic from reliable researchers and experts. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the Web of Science was “TS = (((“critical thinking” or “ct” and “pretest” or “posttest”) or (“critical thinking” or “ct” and “control group” or “quasi experiment” or “experiment”)) and (“collaboration” or “collaborative learning” or “CSCL”) and (“problem solving” or “problem-based learning” or “PBL”))”. The research area was “Education Educational Research”, and the search period was “January 1, 2000, to December 30, 2021”. A total of 412 papers were obtained. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the CNKI was “SU = (‘critical thinking’*‘collaboration’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘collaborative learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘CSCL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem solving’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem-based learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘PBL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem oriented’) AND FT = (‘experiment’ + ‘quasi experiment’ + ‘pretest’ + ‘posttest’ + ‘empirical study’)” (translated into Chinese when searching). A total of 56 studies were found throughout the search period of “January 2000 to December 2021”. From the databases, all duplicates and retractions were eliminated before exporting the references into Endnote, a program for managing bibliographic references. In all, 466 studies were found.

Second, the studies that matched the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the meta-analysis were chosen by two researchers after they had reviewed the abstracts and titles of the gathered articles, yielding a total of 126 studies.

Third, two researchers thoroughly reviewed each included article’s whole text in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Meanwhile, a snowball search was performed using the references and citations of the included articles to ensure complete coverage of the articles. Ultimately, 36 articles were kept.

Two researchers worked together to carry out this entire process, and a consensus rate of almost 94.7% was reached after discussion and negotiation to clarify any emerging differences.

Eligibility criteria

Since not all the retrieved studies matched the criteria for this meta-analysis, eligibility criteria for both inclusion and exclusion were developed as follows:

The publication language of the included studies was limited to English and Chinese, and the full text could be obtained. Articles that did not meet the publication language and articles not published between 2000 and 2021 were excluded.

The research design of the included studies must be empirical and quantitative studies that can assess the effect of collaborative problem-solving on the development of critical thinking. Articles that could not identify the causal mechanisms by which collaborative problem-solving affects critical thinking, such as review articles and theoretical articles, were excluded.

The research method of the included studies must feature a randomized control experiment or a quasi-experiment, or a natural experiment, which have a higher degree of internal validity with strong experimental designs and can all plausibly provide evidence that critical thinking and collaborative problem-solving are causally related. Articles with non-experimental research methods, such as purely correlational or observational studies, were excluded.

The participants of the included studies were only students in school, including K-12 students and college students. Articles in which the participants were non-school students, such as social workers or adult learners, were excluded.

The research results of the included studies must mention definite signs that may be utilized to gauge critical thinking’s impact (e.g., sample size, mean value, or standard deviation). Articles that lacked specific measurement indicators for critical thinking and could not calculate the effect size were excluded.

Data coding design

In order to perform a meta-analysis, it is necessary to collect the most important information from the articles, codify that information’s properties, and convert descriptive data into quantitative data. Therefore, this study designed a data coding template (see Table 1 ). Ultimately, 16 coding fields were retained.

The designed data-coding template consisted of three pieces of information. Basic information about the papers was included in the descriptive information: the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper.

The variable information for the experimental design had three variables: the independent variable (instruction method), the dependent variable (critical thinking), and the moderating variable (learning stage, teaching type, intervention duration, learning scaffold, group size, measuring tool, and subject area). Depending on the topic of this study, the intervention strategy, as the independent variable, was coded into collaborative and non-collaborative problem-solving. The dependent variable, critical thinking, was coded as a cognitive skill and an attitudinal tendency. And seven moderating variables were created by grouping and combining the experimental design variables discovered within the 36 studies (see Table 1 ), where learning stages were encoded as higher education, high school, middle school, and primary school or lower; teaching types were encoded as mixed courses, integrated courses, and independent courses; intervention durations were encoded as 0–1 weeks, 1–4 weeks, 4–12 weeks, and more than 12 weeks; group sizes were encoded as 2–3 persons, 4–6 persons, 7–10 persons, and more than 10 persons; learning scaffolds were encoded as teacher-supported learning scaffold, technique-supported learning scaffold, and resource-supported learning scaffold; measuring tools were encoded as standardized measurement tools (e.g., WGCTA, CCTT, CCTST, and CCTDI) and self-adapting measurement tools (e.g., modified or made by researchers); and subject areas were encoded according to the specific subjects used in the 36 included studies.

The data information contained three metrics for measuring critical thinking: sample size, average value, and standard deviation. It is vital to remember that studies with various experimental designs frequently adopt various formulas to determine the effect size. And this paper used Morris’ proposed standardized mean difference (SMD) calculation formula ( 2008 , p. 369; see Supplementary Table S3 ).

Procedure for extracting and coding data

According to the data coding template (see Table 1 ), the 36 papers’ information was retrieved by two researchers, who then entered them into Excel (see Supplementary Table S1 ). The results of each study were extracted separately in the data extraction procedure if an article contained numerous studies on critical thinking, or if a study assessed different critical thinking dimensions. For instance, Tiwari et al. ( 2010 ) used four time points, which were viewed as numerous different studies, to examine the outcomes of critical thinking, and Chen ( 2013 ) included the two outcome variables of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, which were regarded as two studies. After discussion and negotiation during data extraction, the two researchers’ consistency test coefficients were roughly 93.27%. Supplementary Table S2 details the key characteristics of the 36 included articles with 79 effect quantities, including descriptive information (e.g., the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper), variable information (e.g., independent variables, dependent variables, and moderating variables), and data information (e.g., mean values, standard deviations, and sample size). Following that, testing for publication bias and heterogeneity was done on the sample data using the Rev-Man 5.4 software, and then the test results were used to conduct a meta-analysis.

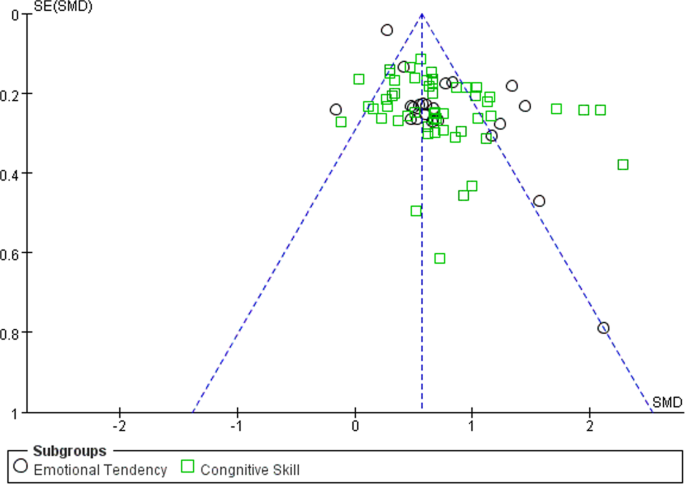

Publication bias test

When the sample of studies included in a meta-analysis does not accurately reflect the general status of research on the relevant subject, publication bias is said to be exhibited in this research. The reliability and accuracy of the meta-analysis may be impacted by publication bias. Due to this, the meta-analysis needs to check the sample data for publication bias (Stewart et al., 2006 ). A popular method to check for publication bias is the funnel plot; and it is unlikely that there will be publishing bias when the data are equally dispersed on either side of the average effect size and targeted within the higher region. The data are equally dispersed within the higher portion of the efficient zone, consistent with the funnel plot connected with this analysis (see Fig. 2 ), indicating that publication bias is unlikely in this situation.

This funnel plot shows the result of publication bias of 79 effect quantities across 36 studies.

Heterogeneity test

To select the appropriate effect models for the meta-analysis, one might use the results of a heterogeneity test on the data effect sizes. In a meta-analysis, it is common practice to gauge the degree of data heterogeneity using the I 2 value, and I 2 ≥ 50% is typically understood to denote medium-high heterogeneity, which calls for the adoption of a random effect model; if not, a fixed effect model ought to be applied (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ). The findings of the heterogeneity test in this paper (see Table 2 ) revealed that I 2 was 86% and displayed significant heterogeneity ( P < 0.01). To ensure accuracy and reliability, the overall effect size ought to be calculated utilizing the random effect model.

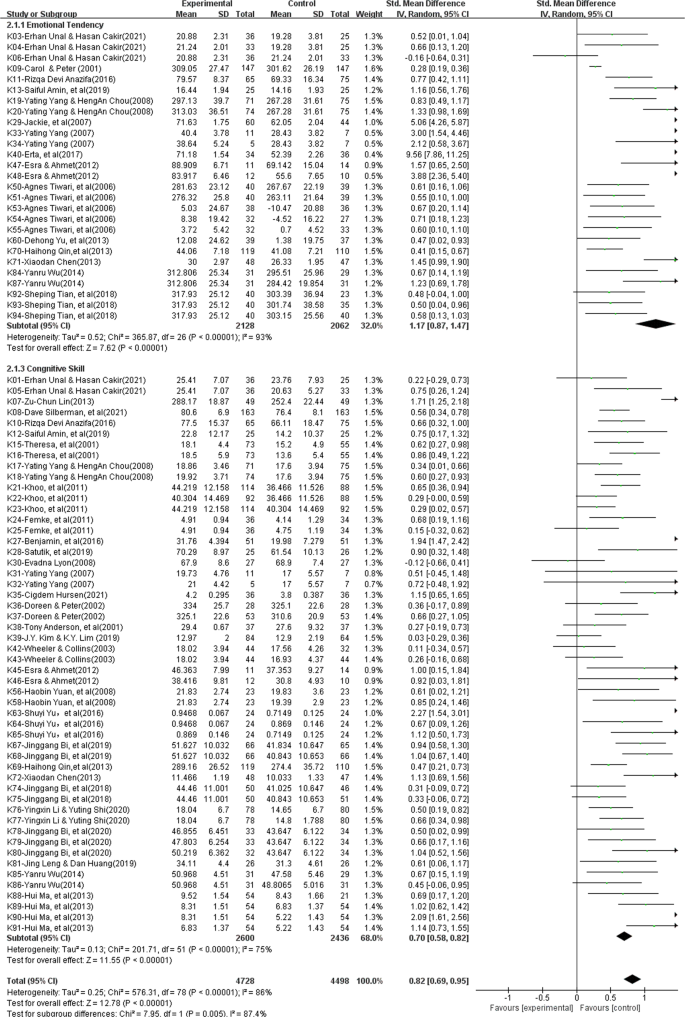

The analysis of the overall effect size

This meta-analysis utilized a random effect model to examine 79 effect quantities from 36 studies after eliminating heterogeneity. In accordance with Cohen’s criterion (Cohen, 1992 ), it is abundantly clear from the analysis results, which are shown in the forest plot of the overall effect (see Fig. 3 ), that the cumulative impact size of cooperative problem-solving is 0.82, which is statistically significant ( z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]), and can encourage learners to practice critical thinking.

This forest plot shows the analysis result of the overall effect size across 36 studies.

In addition, this study examined two distinct dimensions of critical thinking to better understand the precise contributions that collaborative problem-solving makes to the growth of critical thinking. The findings (see Table 3 ) indicate that collaborative problem-solving improves cognitive skills (ES = 0.70) and attitudinal tendency (ES = 1.17), with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.95, P < 0.01). Although collaborative problem-solving improves both dimensions of critical thinking, it is essential to point out that the improvements in students’ attitudinal tendency are much more pronounced and have a significant comprehensive effect (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.87, 1.47]), whereas gains in learners’ cognitive skill are slightly improved and are just above average. (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.58, 0.82]).

The analysis of moderator effect size

The whole forest plot’s 79 effect quantities underwent a two-tailed test, which revealed significant heterogeneity ( I 2 = 86%, z = 12.78, P < 0.01), indicating differences between various effect sizes that may have been influenced by moderating factors other than sampling error. Therefore, exploring possible moderating factors that might produce considerable heterogeneity was done using subgroup analysis, such as the learning stage, learning scaffold, teaching type, group size, duration of the intervention, measuring tool, and the subject area included in the 36 experimental designs, in order to further explore the key factors that influence critical thinking. The findings (see Table 4 ) indicate that various moderating factors have advantageous effects on critical thinking. In this situation, the subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01), and teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05) are all significant moderators that can be applied to support the cultivation of critical thinking. However, since the learning stage and the measuring tools did not significantly differ among intergroup (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05, and chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05), we are unable to explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These are the precise outcomes, as follows:

Various learning stages influenced critical thinking positively, without significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05). High school was first on the list of effect sizes (ES = 1.36, P < 0.01), then higher education (ES = 0.78, P < 0.01), and middle school (ES = 0.73, P < 0.01). These results show that, despite the learning stage’s beneficial influence on cultivating learners’ critical thinking, we are unable to explain why it is essential for cultivating critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Different teaching types had varying degrees of positive impact on critical thinking, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05). The effect size was ranked as follows: mixed courses (ES = 1.34, P < 0.01), integrated courses (ES = 0.81, P < 0.01), and independent courses (ES = 0.27, P < 0.01). These results indicate that the most effective approach to cultivate critical thinking utilizing collaborative problem solving is through the teaching type of mixed courses.

Various intervention durations significantly improved critical thinking, and there were significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01). The effect sizes related to this variable showed a tendency to increase with longer intervention durations. The improvement in critical thinking reached a significant level (ES = 0.85, P < 0.01) after more than 12 weeks of training. These findings indicate that the intervention duration and critical thinking’s impact are positively correlated, with a longer intervention duration having a greater effect.

Different learning scaffolds influenced critical thinking positively, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01). The resource-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.69, P < 0.01) acquired a medium-to-higher level of impact, the technique-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.63, P < 0.01) also attained a medium-to-higher level of impact, and the teacher-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.92, P < 0.01) displayed a high level of significant impact. These results show that the learning scaffold with teacher support has the greatest impact on cultivating critical thinking.

Various group sizes influenced critical thinking positively, and the intergroup differences were statistically significant (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05). Critical thinking showed a general declining trend with increasing group size. The overall effect size of 2–3 people in this situation was the biggest (ES = 0.99, P < 0.01), and when the group size was greater than 7 people, the improvement in critical thinking was at the lower-middle level (ES < 0.5, P < 0.01). These results show that the impact on critical thinking is positively connected with group size, and as group size grows, so does the overall impact.

Various measuring tools influenced critical thinking positively, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05). In this situation, the self-adapting measurement tools obtained an upper-medium level of effect (ES = 0.78), whereas the complete effect size of the standardized measurement tools was the largest, achieving a significant level of effect (ES = 0.84, P < 0.01). These results show that, despite the beneficial influence of the measuring tool on cultivating critical thinking, we are unable to explain why it is crucial in fostering the growth of critical thinking by utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

Different subject areas had a greater impact on critical thinking, and the intergroup differences were statistically significant (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05). Mathematics had the greatest overall impact, achieving a significant level of effect (ES = 1.68, P < 0.01), followed by science (ES = 1.25, P < 0.01) and medical science (ES = 0.87, P < 0.01), both of which also achieved a significant level of effect. Programming technology was the least effective (ES = 0.39, P < 0.01), only having a medium-low degree of effect compared to education (ES = 0.72, P < 0.01) and other fields (such as language, art, and social sciences) (ES = 0.58, P < 0.01). These results suggest that scientific fields (e.g., mathematics, science) may be the most effective subject areas for cultivating critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving with regard to teaching critical thinking

According to this meta-analysis, using collaborative problem-solving as an intervention strategy in critical thinking teaching has a considerable amount of impact on cultivating learners’ critical thinking as a whole and has a favorable promotional effect on the two dimensions of critical thinking. According to certain studies, collaborative problem solving, the most frequently used critical thinking teaching strategy in curriculum instruction can considerably enhance students’ critical thinking (e.g., Liang et al., 2017 ; Liu et al., 2020 ; Cindy, 2004 ). This meta-analysis provides convergent data support for the above research views. Thus, the findings of this meta-analysis not only effectively address the first research query regarding the overall effect of cultivating critical thinking and its impact on the two dimensions of critical thinking (i.e., attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills) utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving, but also enhance our confidence in cultivating critical thinking by using collaborative problem-solving intervention approach in the context of classroom teaching.

Furthermore, the associated improvements in attitudinal tendency are much stronger, but the corresponding improvements in cognitive skill are only marginally better. According to certain studies, cognitive skill differs from the attitudinal tendency in classroom instruction; the cultivation and development of the former as a key ability is a process of gradual accumulation, while the latter as an attitude is affected by the context of the teaching situation (e.g., a novel and exciting teaching approach, challenging and rewarding tasks) (Halpern, 2001 ; Wei and Hong, 2022 ). Collaborative problem-solving as a teaching approach is exciting and interesting, as well as rewarding and challenging; because it takes the learners as the focus and examines problems with poor structure in real situations, and it can inspire students to fully realize their potential for problem-solving, which will significantly improve their attitudinal tendency toward solving problems (Liu et al., 2020 ). Similar to how collaborative problem-solving influences attitudinal tendency, attitudinal tendency impacts cognitive skill when attempting to solve a problem (Liu et al., 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2022 ), and stronger attitudinal tendencies are associated with improved learning achievement and cognitive ability in students (Sison, 2008 ; Zhang et al., 2022 ). It can be seen that the two specific dimensions of critical thinking as well as critical thinking as a whole are affected by collaborative problem-solving, and this study illuminates the nuanced links between cognitive skills and attitudinal tendencies with regard to these two dimensions of critical thinking. To fully develop students’ capacity for critical thinking, future empirical research should pay closer attention to cognitive skills.

The moderating effects of collaborative problem solving with regard to teaching critical thinking

In order to further explore the key factors that influence critical thinking, exploring possible moderating effects that might produce considerable heterogeneity was done using subgroup analysis. The findings show that the moderating factors, such as the teaching type, learning stage, group size, learning scaffold, duration of the intervention, measuring tool, and the subject area included in the 36 experimental designs, could all support the cultivation of collaborative problem-solving in critical thinking. Among them, the effect size differences between the learning stage and measuring tool are not significant, which does not explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

In terms of the learning stage, various learning stages influenced critical thinking positively without significant intergroup differences, indicating that we are unable to explain why it is crucial in fostering the growth of critical thinking.

Although high education accounts for 70.89% of all empirical studies performed by researchers, high school may be the appropriate learning stage to foster students’ critical thinking by utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving since it has the largest overall effect size. This phenomenon may be related to student’s cognitive development, which needs to be further studied in follow-up research.

With regard to teaching type, mixed course teaching may be the best teaching method to cultivate students’ critical thinking. Relevant studies have shown that in the actual teaching process if students are trained in thinking methods alone, the methods they learn are isolated and divorced from subject knowledge, which is not conducive to their transfer of thinking methods; therefore, if students’ thinking is trained only in subject teaching without systematic method training, it is challenging to apply to real-world circumstances (Ruggiero, 2012 ; Hu and Liu, 2015 ). Teaching critical thinking as mixed course teaching in parallel to other subject teachings can achieve the best effect on learners’ critical thinking, and explicit critical thinking instruction is more effective than less explicit critical thinking instruction (Bensley and Spero, 2014 ).

In terms of the intervention duration, with longer intervention times, the overall effect size shows an upward tendency. Thus, the intervention duration and critical thinking’s impact are positively correlated. Critical thinking, as a key competency for students in the 21st century, is difficult to get a meaningful improvement in a brief intervention duration. Instead, it could be developed over a lengthy period of time through consistent teaching and the progressive accumulation of knowledge (Halpern, 2001 ; Hu and Liu, 2015 ). Therefore, future empirical studies ought to take these restrictions into account throughout a longer period of critical thinking instruction.

With regard to group size, a group size of 2–3 persons has the highest effect size, and the comprehensive effect size decreases with increasing group size in general. This outcome is in line with some research findings; as an example, a group composed of two to four members is most appropriate for collaborative learning (Schellens and Valcke, 2006 ). However, the meta-analysis results also indicate that once the group size exceeds 7 people, small groups cannot produce better interaction and performance than large groups. This may be because the learning scaffolds of technique support, resource support, and teacher support improve the frequency and effectiveness of interaction among group members, and a collaborative group with more members may increase the diversity of views, which is helpful to cultivate critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

With regard to the learning scaffold, the three different kinds of learning scaffolds can all enhance critical thinking. Among them, the teacher-supported learning scaffold has the largest overall effect size, demonstrating the interdependence of effective learning scaffolds and collaborative problem-solving. This outcome is in line with some research findings; as an example, a successful strategy is to encourage learners to collaborate, come up with solutions, and develop critical thinking skills by using learning scaffolds (Reiser, 2004 ; Xu et al., 2022 ); learning scaffolds can lower task complexity and unpleasant feelings while also enticing students to engage in learning activities (Wood et al., 2006 ); learning scaffolds are designed to assist students in using learning approaches more successfully to adapt the collaborative problem-solving process, and the teacher-supported learning scaffolds have the greatest influence on critical thinking in this process because they are more targeted, informative, and timely (Xu et al., 2022 ).

With respect to the measuring tool, despite the fact that standardized measurement tools (such as the WGCTA, CCTT, and CCTST) have been acknowledged as trustworthy and effective by worldwide experts, only 54.43% of the research included in this meta-analysis adopted them for assessment, and the results indicated no intergroup differences. These results suggest that not all teaching circumstances are appropriate for measuring critical thinking using standardized measurement tools. “The measuring tools for measuring thinking ability have limits in assessing learners in educational situations and should be adapted appropriately to accurately assess the changes in learners’ critical thinking.”, according to Simpson and Courtney ( 2002 , p. 91). As a result, in order to more fully and precisely gauge how learners’ critical thinking has evolved, we must properly modify standardized measuring tools based on collaborative problem-solving learning contexts.

With regard to the subject area, the comprehensive effect size of science departments (e.g., mathematics, science, medical science) is larger than that of language arts and social sciences. Some recent international education reforms have noted that critical thinking is a basic part of scientific literacy. Students with scientific literacy can prove the rationality of their judgment according to accurate evidence and reasonable standards when they face challenges or poorly structured problems (Kyndt et al., 2013 ), which makes critical thinking crucial for developing scientific understanding and applying this understanding to practical problem solving for problems related to science, technology, and society (Yore et al., 2007 ).

Suggestions for critical thinking teaching

Other than those stated in the discussion above, the following suggestions are offered for critical thinking instruction utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

First, teachers should put a special emphasis on the two core elements, which are collaboration and problem-solving, to design real problems based on collaborative situations. This meta-analysis provides evidence to support the view that collaborative problem-solving has a strong synergistic effect on promoting students’ critical thinking. Asking questions about real situations and allowing learners to take part in critical discussions on real problems during class instruction are key ways to teach critical thinking rather than simply reading speculative articles without practice (Mulnix, 2012 ). Furthermore, the improvement of students’ critical thinking is realized through cognitive conflict with other learners in the problem situation (Yang et al., 2008 ). Consequently, it is essential for teachers to put a special emphasis on the two core elements, which are collaboration and problem-solving, and design real problems and encourage students to discuss, negotiate, and argue based on collaborative problem-solving situations.

Second, teachers should design and implement mixed courses to cultivate learners’ critical thinking, utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving. Critical thinking can be taught through curriculum instruction (Kuncel, 2011 ; Leng and Lu, 2020 ), with the goal of cultivating learners’ critical thinking for flexible transfer and application in real problem-solving situations. This meta-analysis shows that mixed course teaching has a highly substantial impact on the cultivation and promotion of learners’ critical thinking. Therefore, teachers should design and implement mixed course teaching with real collaborative problem-solving situations in combination with the knowledge content of specific disciplines in conventional teaching, teach methods and strategies of critical thinking based on poorly structured problems to help students master critical thinking, and provide practical activities in which students can interact with each other to develop knowledge construction and critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

Third, teachers should be more trained in critical thinking, particularly preservice teachers, and they also should be conscious of the ways in which teachers’ support for learning scaffolds can promote critical thinking. The learning scaffold supported by teachers had the greatest impact on learners’ critical thinking, in addition to being more directive, targeted, and timely (Wood et al., 2006 ). Critical thinking can only be effectively taught when teachers recognize the significance of critical thinking for students’ growth and use the proper approaches while designing instructional activities (Forawi, 2016 ). Therefore, with the intention of enabling teachers to create learning scaffolds to cultivate learners’ critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem solving, it is essential to concentrate on the teacher-supported learning scaffolds and enhance the instruction for teaching critical thinking to teachers, especially preservice teachers.

Implications and limitations

There are certain limitations in this meta-analysis, but future research can correct them. First, the search languages were restricted to English and Chinese, so it is possible that pertinent studies that were written in other languages were overlooked, resulting in an inadequate number of articles for review. Second, these data provided by the included studies are partially missing, such as whether teachers were trained in the theory and practice of critical thinking, the average age and gender of learners, and the differences in critical thinking among learners of various ages and genders. Third, as is typical for review articles, more studies were released while this meta-analysis was being done; therefore, it had a time limit. With the development of relevant research, future studies focusing on these issues are highly relevant and needed.

Conclusions

The subject of the magnitude of collaborative problem-solving’s impact on fostering students’ critical thinking, which received scant attention from other studies, was successfully addressed by this study. The question of the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking was addressed in this study, which addressed a topic that had gotten little attention in earlier research. The following conclusions can be made:

Regarding the results obtained, collaborative problem solving is an effective teaching approach to foster learners’ critical thinking, with a significant overall effect size (ES = 0.82, z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]). With respect to the dimensions of critical thinking, collaborative problem-solving can significantly and effectively improve students’ attitudinal tendency, and the comprehensive effect is significant (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.87, 1.47]); nevertheless, it falls short in terms of improving students’ cognitive skills, having only an upper-middle impact (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.58, 0.82]).

As demonstrated by both the results and the discussion, there are varying degrees of beneficial effects on students’ critical thinking from all seven moderating factors, which were found across 36 studies. In this context, the teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), and learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01) all have a positive impact on critical thinking, and they can be viewed as important moderating factors that affect how critical thinking develops. Since the learning stage (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05) and measuring tools (chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05) did not demonstrate any significant intergroup differences, we are unable to explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included within the article and its supplementary information files, and the supplementary information files are available in the Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/IPFJO6 .

Bensley DA, Spero RA (2014) Improving critical thinking skills and meta-cognitive monitoring through direct infusion. Think Skills Creat 12:55–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2014.02.001

Article Google Scholar

Castle A (2009) Defining and assessing critical thinking skills for student radiographers. Radiography 15(1):70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2007.10.007

Chen XD (2013) An empirical study on the influence of PBL teaching model on critical thinking ability of non-English majors. J PLA Foreign Lang College 36 (04):68–72

Google Scholar

Cohen A (1992) Antecedents of organizational commitment across occupational groups: a meta-analysis. J Organ Behav. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030130602

Cooper H (2010) Research synthesis and meta-analysis: a step-by-step approach, 4th edn. Sage, London, England

Cindy HS (2004) Problem-based learning: what and how do students learn? Educ Psychol Rev 51(1):31–39

Duch BJ, Gron SD, Allen DE (2001) The power of problem-based learning: a practical “how to” for teaching undergraduate courses in any discipline. Stylus Educ Sci 2:190–198

Ennis RH (1989) Critical thinking and subject specificity: clarification and needed research. Educ Res 18(3):4–10. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x018003004

Facione PA (1990) Critical thinking: a statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. Research findings and recommendations. Eric document reproduction service. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ed315423

Facione PA, Facione NC (1992) The California Critical Thinking Dispositions Inventory (CCTDI) and the CCTDI test manual. California Academic Press, Millbrae, CA

Forawi SA (2016) Standard-based science education and critical thinking. Think Skills Creat 20:52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2016.02.005

Halpern DF (2001) Assessing the effectiveness of critical thinking instruction. J Gen Educ 50(4):270–286. https://doi.org/10.2307/27797889

Hu WP, Liu J (2015) Cultivation of pupils’ thinking ability: a five-year follow-up study. Psychol Behav Res 13(05):648–654. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2015.05.010

Huber K (2016) Does college teach critical thinking? A meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res 86(2):431–468. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315605917

Kek MYCA, Huijser H (2011) The power of problem-based learning in developing critical thinking skills: preparing students for tomorrow’s digital futures in today’s classrooms. High Educ Res Dev 30(3):329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.501074

Kuncel NR (2011) Measurement and meaning of critical thinking (Research report for the NRC 21st Century Skills Workshop). National Research Council, Washington, DC

Kyndt E, Raes E, Lismont B, Timmers F, Cascallar E, Dochy F (2013) A meta-analysis of the effects of face-to-face cooperative learning. Do recent studies falsify or verify earlier findings? Educ Res Rev 10(2):133–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.02.002

Leng J, Lu XX (2020) Is critical thinking really teachable?—A meta-analysis based on 79 experimental or quasi experimental studies. Open Educ Res 26(06):110–118. https://doi.org/10.13966/j.cnki.kfjyyj.2020.06.011

Liang YZ, Zhu K, Zhao CL (2017) An empirical study on the depth of interaction promoted by collaborative problem solving learning activities. J E-educ Res 38(10):87–92. https://doi.org/10.13811/j.cnki.eer.2017.10.014

Lipsey M, Wilson D (2001) Practical meta-analysis. International Educational and Professional, London, pp. 92–160

Liu Z, Wu W, Jiang Q (2020) A study on the influence of problem based learning on college students’ critical thinking-based on a meta-analysis of 31 studies. Explor High Educ 03:43–49

Morris SB (2008) Estimating effect sizes from pretest-posttest-control group designs. Organ Res Methods 11(2):364–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106291059

Article ADS Google Scholar

Mulnix JW (2012) Thinking critically about critical thinking. Educ Philos Theory 44(5):464–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2010.00673.x

Naber J, Wyatt TH (2014) The effect of reflective writing interventions on the critical thinking skills and dispositions of baccalaureate nursing students. Nurse Educ Today 34(1):67–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.04.002

National Research Council (2012) Education for life and work: developing transferable knowledge and skills in the 21st century. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Niu L, Behar HLS, Garvan CW (2013) Do instructional interventions influence college students’ critical thinking skills? A meta-analysis. Educ Res Rev 9(12):114–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2012.12.002

Peng ZM, Deng L (2017) Towards the core of education reform: cultivating critical thinking skills as the core of skills in the 21st century. Res Educ Dev 24:57–63. https://doi.org/10.14121/j.cnki.1008-3855.2017.24.011

Reiser BJ (2004) Scaffolding complex learning: the mechanisms of structuring and problematizing student work. J Learn Sci 13(3):273–304. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1303_2

Ruggiero VR (2012) The art of thinking: a guide to critical and creative thought, 4th edn. Harper Collins College Publishers, New York

Schellens T, Valcke M (2006) Fostering knowledge construction in university students through asynchronous discussion groups. Comput Educ 46(4):349–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2004.07.010

Sendag S, Odabasi HF (2009) Effects of an online problem based learning course on content knowledge acquisition and critical thinking skills. Comput Educ 53(1):132–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.01.008

Sison R (2008) Investigating Pair Programming in a Software Engineering Course in an Asian Setting. 2008 15th Asia-Pacific Software Engineering Conference, pp. 325–331. https://doi.org/10.1109/APSEC.2008.61

Simpson E, Courtney M (2002) Critical thinking in nursing education: literature review. Mary Courtney 8(2):89–98

Stewart L, Tierney J, Burdett S (2006) Do systematic reviews based on individual patient data offer a means of circumventing biases associated with trial publications? Publication bias in meta-analysis. John Wiley and Sons Inc, New York, pp. 261–286

Tiwari A, Lai P, So M, Yuen K (2010) A comparison of the effects of problem-based learning and lecturing on the development of students’ critical thinking. Med Educ 40(6):547–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02481.x

Wood D, Bruner JS, Ross G (2006) The role of tutoring in problem solving. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 17(2):89–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x

Wei T, Hong S (2022) The meaning and realization of teachable critical thinking. Educ Theory Practice 10:51–57

Xu EW, Wang W, Wang QX (2022) A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of programming teaching in promoting K-12 students’ computational thinking. Educ Inf Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11445-2

Yang YC, Newby T, Bill R (2008) Facilitating interactions through structured web-based bulletin boards: a quasi-experimental study on promoting learners’ critical thinking skills. Comput Educ 50(4):1572–1585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.04.006

Yore LD, Pimm D, Tuan HL (2007) The literacy component of mathematical and scientific literacy. Int J Sci Math Educ 5(4):559–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-007-9089-4

Zhang T, Zhang S, Gao QQ, Wang JH (2022) Research on the development of learners’ critical thinking in online peer review. Audio Visual Educ Res 6:53–60. https://doi.org/10.13811/j.cnki.eer.2022.06.08

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the graduate scientific research and innovation project of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region named “Research on in-depth learning of high school information technology courses for the cultivation of computing thinking” (No. XJ2022G190) and the independent innovation fund project for doctoral students of the College of Educational Science of Xinjiang Normal University named “Research on project-based teaching of high school information technology courses from the perspective of discipline core literacy” (No. XJNUJKYA2003).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Educational Science, Xinjiang Normal University, 830017, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China

Enwei Xu, Wei Wang & Qingxia Wang

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Enwei Xu or Wei Wang .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Additional information.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary tables, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Xu, E., Wang, W. & Wang, Q. The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving in promoting students’ critical thinking: A meta-analysis based on empirical literature. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 16 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01508-1

Download citation

Received : 07 August 2022

Accepted : 04 January 2023

Published : 11 January 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01508-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Impacts of online collaborative learning on students’ intercultural communication apprehension and intercultural communicative competence.

- Hoa Thi Hoang Chau

- Hung Phu Bui

- Quynh Thi Huong Dinh

Education and Information Technologies (2024)

Exploring the effects of digital technology on deep learning: a meta-analysis

The influence of scaffolding for computational thinking on cognitive load and problem-solving skills in collaborative programming.

- Yoonhee Shin

- Jaewon Jung

- Bokmoon Jung

The impacts of computer-supported collaborative learning on students’ critical thinking: a meta-analysis

- Yoseph Gebrehiwot Tedla

- Hsiu-Ling Chen

Sustainable electricity generation and farm-grid utilization from photovoltaic aquaculture: a bibliometric analysis

- A. A. Amusa

- M. Alhassan

International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Eight Instructional Strategies for Promoting Critical Thinking

- Share article

(This is the first post in a three-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom?

This three-part series will explore what critical thinking is, if it can be specifically taught and, if so, how can teachers do so in their classrooms.

Today’s guests are Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

You might also be interested in The Best Resources On Teaching & Learning Critical Thinking In The Classroom .

Current Events

Dara Laws Savage is an English teacher at the Early College High School at Delaware State University, where she serves as a teacher and instructional coach and lead mentor. Dara has been teaching for 25 years (career preparation, English, photography, yearbook, newspaper, and graphic design) and has presented nationally on project-based learning and technology integration:

There is so much going on right now and there is an overload of information for us to process. Did you ever stop to think how our students are processing current events? They see news feeds, hear news reports, and scan photos and posts, but are they truly thinking about what they are hearing and seeing?

I tell my students that my job is not to give them answers but to teach them how to think about what they read and hear. So what is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom? There are just as many definitions of critical thinking as there are people trying to define it. However, the Critical Think Consortium focuses on the tools to create a thinking-based classroom rather than a definition: “Shape the climate to support thinking, create opportunities for thinking, build capacity to think, provide guidance to inform thinking.” Using these four criteria and pairing them with current events, teachers easily create learning spaces that thrive on thinking and keep students engaged.

One successful technique I use is the FIRE Write. Students are given a quote, a paragraph, an excerpt, or a photo from the headlines. Students are asked to F ocus and respond to the selection for three minutes. Next, students are asked to I dentify a phrase or section of the photo and write for two minutes. Third, students are asked to R eframe their response around a specific word, phrase, or section within their previous selection. Finally, students E xchange their thoughts with a classmate. Within the exchange, students also talk about how the selection connects to what we are covering in class.

There was a controversial Pepsi ad in 2017 involving Kylie Jenner and a protest with a police presence. The imagery in the photo was strikingly similar to a photo that went viral with a young lady standing opposite a police line. Using that image from a current event engaged my students and gave them the opportunity to critically think about events of the time.

Here are the two photos and a student response:

F - Focus on both photos and respond for three minutes

In the first picture, you see a strong and courageous black female, bravely standing in front of two officers in protest. She is risking her life to do so. Iesha Evans is simply proving to the world she does NOT mean less because she is black … and yet officers are there to stop her. She did not step down. In the picture below, you see Kendall Jenner handing a police officer a Pepsi. Maybe this wouldn’t be a big deal, except this was Pepsi’s weak, pathetic, and outrageous excuse of a commercial that belittles the whole movement of people fighting for their lives.

I - Identify a word or phrase, underline it, then write about it for two minutes

A white, privileged female in place of a fighting black woman was asking for trouble. A struggle we are continuously fighting every day, and they make a mockery of it. “I know what will work! Here Mr. Police Officer! Drink some Pepsi!” As if. Pepsi made a fool of themselves, and now their already dwindling fan base continues to ever shrink smaller.

R - Reframe your thoughts by choosing a different word, then write about that for one minute

You don’t know privilege until it’s gone. You don’t know privilege while it’s there—but you can and will be made accountable and aware. Don’t use it for evil. You are not stupid. Use it to do something. Kendall could’ve NOT done the commercial. Kendall could’ve released another commercial standing behind a black woman. Anything!

Exchange - Remember to discuss how this connects to our school song project and our previous discussions?

This connects two ways - 1) We want to convey a strong message. Be powerful. Show who we are. And Pepsi definitely tried. … Which leads to the second connection. 2) Not mess up and offend anyone, as had the one alma mater had been linked to black minstrels. We want to be amazing, but we have to be smart and careful and make sure we include everyone who goes to our school and everyone who may go to our school.

As a final step, students read and annotate the full article and compare it to their initial response.

Using current events and critical-thinking strategies like FIRE writing helps create a learning space where thinking is the goal rather than a score on a multiple-choice assessment. Critical-thinking skills can cross over to any of students’ other courses and into life outside the classroom. After all, we as teachers want to help the whole student be successful, and critical thinking is an important part of navigating life after they leave our classrooms.

‘Before-Explore-Explain’

Patrick Brown is the executive director of STEM and CTE for the Fort Zumwalt school district in Missouri and an experienced educator and author :

Planning for critical thinking focuses on teaching the most crucial science concepts, practices, and logical-thinking skills as well as the best use of instructional time. One way to ensure that lessons maintain a focus on critical thinking is to focus on the instructional sequence used to teach.

Explore-before-explain teaching is all about promoting critical thinking for learners to better prepare students for the reality of their world. What having an explore-before-explain mindset means is that in our planning, we prioritize giving students firsthand experiences with data, allow students to construct evidence-based claims that focus on conceptual understanding, and challenge students to discuss and think about the why behind phenomena.

Just think of the critical thinking that has to occur for students to construct a scientific claim. 1) They need the opportunity to collect data, analyze it, and determine how to make sense of what the data may mean. 2) With data in hand, students can begin thinking about the validity and reliability of their experience and information collected. 3) They can consider what differences, if any, they might have if they completed the investigation again. 4) They can scrutinize outlying data points for they may be an artifact of a true difference that merits further exploration of a misstep in the procedure, measuring device, or measurement. All of these intellectual activities help them form more robust understanding and are evidence of their critical thinking.

In explore-before-explain teaching, all of these hard critical-thinking tasks come before teacher explanations of content. Whether we use discovery experiences, problem-based learning, and or inquiry-based activities, strategies that are geared toward helping students construct understanding promote critical thinking because students learn content by doing the practices valued in the field to generate knowledge.

An Issue of Equity