| > > > Structure of U.S. Education Structure of U.S. Education The structure of the U.S. Education System includes information on the types and levels of education offered, how people progress through the system, and the characteristics of recognized degree programs and other programs of study. Similar structural principles apply to all U.S. education. For specific information on alternative types of educational provision, such as distance learning, go to . provides a chart of the U.S. education system and basic information and resources about how students progress. provides information and resources for how students are examined and graded, both to measure progress and to gain access to higher levels. provides information and resources for preschool, primary, and secondary education. provides information and resources for occupationally oriented education and training at the secondary and postsecondary levels, but below the bachelor's degree level. provides information and resources for associate and bachelor's degree programs and other undergraduate (first degree level) education. provides information and resources for first professional degree programs, master's degrees, research doctorate degrees, and other advanced studies. | | Information on this section is not intended to constitute advice nor is it to be used as a substitute for specific counsel from a licensed professional. You should not act (or refrain from acting) based upon information in this section without independently verifying the original source information and, as necessary, obtaining professional advice regarding your particular facts and circumstances. |  - History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Prehistoric and primitive cultures- Mesopotamia

- North China

- The Hindu tradition

- The introduction of Buddhist influences

- Classical India

- Indian influences on Asia

- Xi (Western) Zhou (1046–771 bce )

- Dong (Eastern) Zhou (770–256 bce )

- Qin autocracy (221–206 bce )

- Scholarship under the Han (206 bce –220 ce )

- Introduction of Buddhism

- Ancient Hebrews

- Education of youth

- Higher education

- The institutions

- Physical education

- The primary school

- Secondary education

- Early Roman education

- Roman modifications

- Education in the later Roman Empire

- Ancient Persia

- Elementary education

- Professional education

- Early Russian education: Kiev and Muscovy

- Influences on Muslim education and culture

- Aims and purposes of Muslim education

- Organization of education

- Major periods of Muslim education and learning

- Influence of Islamic learning on the West

- From the beginnings to the 4th century

- From the 5th to the 8th century

- The Irish and English revivals

- The cultural revival under Charlemagne and his successors

- Influences of the Carolingian renaissance abroad

- Education of the laity in the 9th and 10th centuries

- Monastic schools

- Urban schools

- New curricula and philosophies

- Thomist philosophy

- The Italian universities

- The French universities

- The English universities

- Universities elsewhere in Europe

- General characteristics of medieval universities

- Lay education and the lower schools

- The foundations of Muslim education

- The Mughal period

- The Tang dynasty (618–907 ce )

- The Song (960–1279)

- The Mongol period (1206–1368)

- The Ming period (1368–1644)

- The Manchu period (1644–1911/12)

- The ancient period to the 12th century

- Education of the warriors

- Education in the Tokugawa era

- Effect of early Western contacts

- The Muslim influence

- The secular influence

- Early influences

- Emergence of the new gymnasium

- Nonscholastic traditions

- Dutch humanism

- Juan Luis Vives

- The early English humanists

- Luther and the German Reformation

- The English Reformation

- The French Reformation

- The Calvinist Reformation

- The Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation

- The legacy of the Reformation

- The new scientism and rationalism

- The Protestant demand for universal elementary education

- The pedagogy of Ratke

- The pedagogy of Comenius

- The schools of Gotha

- Courtly education

- The teaching congregations

- Female education

- The Puritan reformers

- Royalist education

- The academies

- John Locke’s empiricism and education as conduct

- Giambattista Vico, critic of Cartesianism

- The condition of the schools and universities

- August Hermann Francke

- Johann Julius Hecker

- The Sensationists

- The Rousseauists

- National education under enlightened rulers

- Spanish and Portuguese America

- French Québec

- New England

- The new academies

- The middle colonies

- The Southern colonies

- Newfoundland and the Maritime Provinces.

- The social and historical setting

- The pedagogy of Pestalozzi

- The influence of Pestalozzi

- The pedagogy of Froebel

- The kindergarten movement

- The psychology and pedagogy of Herbart

- The Herbartians

- Other German theorists

- French theorists

- Spencer’s scientism

- Humboldt’s reforms

- Developments after 1815

- Girls’ schools

- The new German universities

- Development of state education

- Elementary Education Act

- Secondary and higher education

- The educational awakening

- Education for females

- New Zealand

- Education under the East India Company

- Indian universities

- The Meiji Restoration and the assimilation of Western civilization

- Establishment of a national system of education

- The conservative reaction

- Establishment of nationalistic education systems

- Promotion of industrial education

- Social and historical background

- Influence of psychology and other fields on education

- Traditional movements

- Progressive education

- Child-centred education

- Scientific-realist education

- Social-reconstructionist education

- Major trends and problems

- Early 19th to early 20th century

- Education Act of 1944

- The comprehensive movement

- Further education

- Imperial Germany

- Weimar Republic

- Nazi Germany

- Changes after World War II

- The Third Republic

- The Netherlands

- Switzerland

- Expansion of American education

- Curriculum reforms

- Federal involvement in local education

- Changes in higher education

- Professional organizations

- Canadian educational reforms

- The administration of public education

- Before 1917

- The Stalinist years, 1931–53

- The Khrushchev reforms

- From Brezhnev to Gorbachev

- Perestroika and education

- The modernization movement

- Education in the republic

- Education under the Nationalist government

- Education under communism

- Post-Mao education

- Communism and the intellectuals

- Education at the beginning of the century

- Education to 1940

- Education changes during World War II

- Education after World War II

- Pre-independence period

- The postindependence period in India

- The postindependence period in Pakistan

- The postindependence period in Bangladesh

- The postindependence period in Sri Lanka

- South Africa

- General influences and policies of the colonial powers

- Education in Portuguese colonies and former colonies

- German educational policy in Africa

- Education in British colonies and former colonies

- Education in French colonies and former colonies

- Education in Belgian colonies and former colonies

- Problems and tasks of African education in the late 20th century

- Colonialism and its consequences

- The second half of the 20th century

- The Islamic revival

- Migration and the brain drain

- The heritage of independence

- Administration

- Primary education and literacy

- Reform trends

- Malaysia and Singapore

- Philippines

- Education and social cohesion

- Education and social conflict

- Education and personal growth

- Education and civil society

- Education and economic development

- Primary-level school enrollments

- Secondary-level school enrollments

- Tertiary-level school enrollments

- Other developments in formal education

- Literacy as a measure of success

- Access to education

- Implications for socioeconomic status

- Social consequences of education in developing countries

- The role of the state

- Social and family interaction

- Alternative forms of education

What was education like in ancient Athens?How does social class affect education attainment, when did education become compulsory, what are alternative forms of education, do school vouchers offer students access to better education.  Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article. - World History Encyclopedia - Education in the Elizabethan Era

- Academia - Return on Education Using the Concept of Opportunity Cost

- National Geographic - Geography

- Table Of Contents

What does education mean?Education refers to the discipline that is concerned with methods of teaching and learning in schools or school-like environments, as opposed to various nonformal and informal means of socialization . Beginning approximately at the end of the 7th or during the 6th century, Athens became the first city-state in ancient Greece to renounce education that was oriented toward the future duties of soldiers. The evolution of Athenian education reflected that of the city itself, which was moving toward increasing democratization. Research has found that education is the strongest determinant of individuals’ occupational status and chances of success in adult life. However, the correlation between family socioeconomic status and school success or failure appears to have increased worldwide. Long-term trends suggest that as societies industrialize and modernize, social class becomes increasingly important in determining educational outcomes and occupational attainment. While education is not compulsory in practice everywhere in the world, the right of individuals to an educational program that respects their personality, talents, abilities, and cultural heritage has been upheld in various international agreements, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948; the Declaration of the Rights of the Child of 1959; and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966. Alternative forms of education have developed since the late 20th century, such as distance learning , homeschooling , and many parallel or supplementary systems of education often designated as “nonformal” and “popular.” Religious institutions also instruct the young and old alike in sacred knowledge as well as in the values and skills required for participation in local, national, and transnational societies. School vouchers have been a hotly debated topic in the United States. Some parents of voucher recipients reported high levels of satisfaction, and studies have found increased voucher student graduation rates. Some studies have found, however, that students using vouchers to attend private schools instead of public ones did not show significantly higher levels of academic achievement. Learn more at ProCon.org. Should corporal punishment be used in elementary education settings?Whether corporal punishment should be used in elementary education settings is widely debated. Some say it is the appropriate discipline for certain children when used in moderation because it sets clear boundaries and motivates children to behave in school. Others say can inflict long-lasting physical and mental harm on students while creating an unsafe and violent school environment. For more on the corporal punishment debate, visit ProCon.org . Should dress codes be implemented and enforced in education settings?Whether dress codes should be implemented and enforced in education settings is hotly debated. Some argue dress codes enforce decorum and a serious, professional atmosphere conducive to success, as well as promote safety. Others argue dress codes reinforce racist standards of beauty and dress and are are seldom uniformly mandated, often discriminating against women and marginalized groups. For more on the dress code debate, visit ProCon.org . Recent Newseducation , discipline that is concerned with methods of teaching and learning in schools or school-like environments as opposed to various nonformal and informal means of socialization (e.g., rural development projects and education through parent-child relationships). (Read Arne Duncan’s Britannica essay on “Education: The Great Equalizer.”) Education can be thought of as the transmission of the values and accumulated knowledge of a society. In this sense, it is equivalent to what social scientists term socialization or enculturation. Children—whether conceived among New Guinea tribespeople, the Renaissance Florentines, or the middle classes of Manhattan—are born without culture . Education is designed to guide them in learning a culture , molding their behaviour in the ways of adulthood , and directing them toward their eventual role in society. In the most primitive cultures , there is often little formal learning—little of what one would ordinarily call school or classes or teachers . Instead, the entire environment and all activities are frequently viewed as school and classes, and many or all adults act as teachers. As societies grow more complex, however, the quantity of knowledge to be passed on from one generation to the next becomes more than any one person can know, and, hence, there must evolve more selective and efficient means of cultural transmission. The outcome is formal education—the school and the specialist called the teacher. As society becomes ever more complex and schools become ever more institutionalized, educational experience becomes less directly related to daily life, less a matter of showing and learning in the context of the workaday world, and more abstracted from practice, more a matter of distilling, telling, and learning things out of context. This concentration of learning in a formal atmosphere allows children to learn far more of their culture than they are able to do by merely observing and imitating. As society gradually attaches more and more importance to education, it also tries to formulate the overall objectives, content, organization, and strategies of education. Literature becomes laden with advice on the rearing of the younger generation. In short, there develop philosophies and theories of education. This article discusses the history of education, tracing the evolution of the formal teaching of knowledge and skills from prehistoric and ancient times to the present, and considering the various philosophies that have inspired the resulting systems. Other aspects of education are treated in a number of articles. For a treatment of education as a discipline, including educational organization, teaching methods, and the functions and training of teachers, see teaching ; pedagogy ; and teacher education . For a description of education in various specialized fields, see historiography ; legal education ; medical education ; science, history of . For an analysis of educational philosophy , see education, philosophy of . For an examination of some of the more important aids in education and the dissemination of knowledge, see dictionary ; encyclopaedia ; library ; museum ; printing ; publishing, history of . Some restrictions on educational freedom are discussed in censorship . For an analysis of pupil attributes, see intelligence, human ; learning theory ; psychological testing . Education in primitive and early civilized culturesThe term education can be applied to primitive cultures only in the sense of enculturation , which is the process of cultural transmission. A primitive person, whose culture is the totality of his universe, has a relatively fixed sense of cultural continuity and timelessness. The model of life is relatively static and absolute, and it is transmitted from one generation to another with little deviation. As for prehistoric education, it can only be inferred from educational practices in surviving primitive cultures.  The purpose of primitive education is thus to guide children to becoming good members of their tribe or band. There is a marked emphasis upon training for citizenship , because primitive people are highly concerned with the growth of individuals as tribal members and the thorough comprehension of their way of life during passage from prepuberty to postpuberty.  Because of the variety in the countless thousands of primitive cultures, it is difficult to describe any standard and uniform characteristics of prepuberty education. Nevertheless, certain things are practiced commonly within cultures. Children actually participate in the social processes of adult activities, and their participatory learning is based upon what the American anthropologist Margaret Mead called empathy , identification, and imitation . Primitive children, before reaching puberty, learn by doing and observing basic technical practices. Their teachers are not strangers but rather their immediate community . In contrast to the spontaneous and rather unregulated imitations in prepuberty education, postpuberty education in some cultures is strictly standardized and regulated. The teaching personnel may consist of fully initiated men, often unknown to the initiate though they are his relatives in other clans. The initiation may begin with the initiate being abruptly separated from his familial group and sent to a secluded camp where he joins other initiates. The purpose of this separation is to deflect the initiate’s deep attachment away from his family and to establish his emotional and social anchorage in the wider web of his culture. The initiation “curriculum” does not usually include practical subjects. Instead, it consists of a whole set of cultural values, tribal religion, myths , philosophy, history, rituals, and other knowledge. Primitive people in some cultures regard the body of knowledge constituting the initiation curriculum as most essential to their tribal membership. Within this essential curriculum, religious instruction takes the most prominent place. The Education System of the United States of America: Overview and Foundations- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2022

- pp 1015–1042

- Cite this reference work entry

Part of the book series: Global Education Systems ((GES)) 2189 Accesses Prevailing discourse in the USA about the country’s teachers, educational institutions, and instructional approaches is a conversation that is national in character. Yet the structures and the administrative and governance apparatuses themselves are strikingly local in character across the USA. Public understanding and debate about education can be distorted in light of divergence between the country’s educational aspirations and the vehicles in place for pursuing those aims. In addressing its purpose as a survey of US education, the following chapter interrogates this apparent contradiction, first discussing historical and social factors that help account for a social construction of the USA as singular and national system. Discussion then moves to a descriptive analysis of education in the USA as institutionalized at the numerous levels – aspects that often reflect local prerogative and difference more so than a uniform national character. The chapter concludes with summary points regarding US federalism as embodied in the country’s oversight and conduct of formal education. This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access. Access this chapterSubscribe and save. - Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout Purchases are for personal use only Institutional subscriptions Similar content being viewed by others The Education System of the United States of America School Education Systems and Policies in South Asia Barber, B. R. (1993). America skips school: Why we talk so much about education and do so little. Harper’s Magazine, 287 (1722), 39–46. Google Scholar Beck, R. (1990). Vocational preparation and general education . Berkeley: National Center for Research in Vocational Education. Berliner, D. C. (2011). The context for interpreting PISA results in the USA. In M. A. Pereyra, H.-G. Kotthoff, & R. Cowen (Eds.), PISA under examination: Changing knowledge, changing tests, changing schools (pp. 77–96). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. Chapter Google Scholar Berliner, D. C., & Biddle, B. (1995). The manufactured crisis: Myths, fraud, and the attack on America’s public schools . Reading: Addison-Wesley. Brubacher, J. S., & Rudy, W. (1997). Higher education in transition: A history of American colleges and universities . Transaction Publishers. Piscataway, New Jersey [NJ], United States. Carson, C. C., Huelskamp, R., & Woodall, T. (1993). Perspectives on education in America: An annotated briefing. Sandia report. Journal of Educational Research, 86 (5), 259–310. Article Google Scholar Center for Postsecondary Research. (2019). Carnegie classification of institutions of higher education . School of Education, Indiana University. http://carnegieclassifications.iu.edu/ Clauset, A., Arbesman, S., & Larremore, D. B. (2015). Systematic inequality and hierarchy in faculty hiring networks. Science Advances, 1 (1), 1–6. Commission on the Reorganization of Secondary Education, National Education Association. (1918). Cardinal principles of secondary education, Bureau of Education bulletin . Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Cremin, L. A. (1957). The republic and the school: Horace Mann on the education of free men . New York: Teachers College Press. Cremin, L. A. (1961). The transformation of the American school: Progressivism in American education, 1876–1957 . New York: Alfred A. Knopf. Cremin, L. A. (1988). American education: The metropolitan experience, 1876–1980 . New York: Harper-Collins. Crowley, S., & Green, E. L. (2019). A college chain crumbles, and millions in student loan cash disappears. New York Times , March 7. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/07/business/argosy-college-art-insititutes-south-university.html Curti, M. (1943). The growth of American thought . New York: Harper and Brothers. Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). The flat world and education: How America’s commitment to equity will determine our future . New York: Teachers College Press. Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education . New York: The Free Press. Diffey, L. (2018). 50-state comparison: State Kindergarten-through-third-grade policies . Denver: Education Commission of the States. https://www.ecs.org/kindergarten-policies/ . Last accessed 12 Mar 2019. Finn, C. E., Julian, L., & Petrilli, M. J. (Eds.). (2006). The state of state standards 2006 . Washington, DC: Thomas B. Fordham Foundation. Fischer, K. (2019). It’s a New Assault on the University. Chronicle of Higher Education (February 17). https://www.chronicle.com/article/its-anew-assault-on-the-university/ Flaherty, C. (2017). Killing tenure. Inside Higher Ed (January 13). https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/01/13/legislation-two-statesseeks-eliminate-tenure-publichigher-education . Friedman-Krauss, A. H., Steven Barnett, W., Garver, K. A., Hodges, K. S., Weisenfeld, G. G., & DiCrecchio, N. (2019). The state of preschool 2018: State preschool yearbook . New Brunswick: Rutgers University, National Institute for Early Education Research. http://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/YB2018_Full-ReportR3wAppendices.pdf . Last accessed 30 Apr 2019. Fulton, M. (2019). 50-state comparison: State postsecondary governance structures . Denver: Education Commission of the States. https://www.ecs.org/50-state-comparison-postsecondary-governance-structures/ . Last accessed 15 Nov 2019. Gerstle, G. (2015). Liberty and coercion: The paradox of American government from the founding to the present . Princeton: Princeton University Press. Gutek, G. L. (2013). An historical introduction to American education (2nd ed.). Long Grove: Waveland. Hartong, S. (2016). New structures of power and regulation within ‘distributed’ education policy: The example of the US Common Core State Standards Initiative. Journal of Education Policy, 31 (2), 213–225. Hemelt, S. W., & Marcotte, D. E. (2016). The changing landscape of tuition and enrollment in American Public Higher Education. Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2 (1), 42–68. Henig, J. R. (2013). The end of exceptionalism in American education: The changing politics of school reform . Cambridge: Harvard Education Press. Herman, J., Post, S., & O’Halloran, S. (2013). The United States is far behind other countries on pre-K . Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. Hyslop-Margison, E. J. (1999). An assessment of the historical arguments in vocational education reform. Journal of Career and Technical Education, 17 (1), 23–30. Hu, W. (2008). New horizons in high school classrooms. New York Times , October 26. A-21. Kaestle, C. F. (1983). Pillars of the republic: common schools and American Society, 1780–1860 . New York: Hill and Wang. Kaestle, C. F. (1988). Public education in the old northwest: “necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind”. Indiana Magazine of History, 84 (1), 60–74. Katz, M. B. (1968). The irony of early school reform: Educational innovation in mid-nineteenth century Massachusetts . Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Kozol, J. (1991). Savage inequalities: Children in America’s schools . New York: Crown Publishing. Labaree, D. F. (2010). How Dewey lost: The victory of David Snedden and social efficiency in the reform of American education. In D. Trohler, T. Schlag, & F. Osterwalder (Eds.), Pragmatism and modernities (pp. 163–188). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. LaMorte, M. W. (2012). School law: Cases and concepts (10th ed.). Boston: Pearson. Lannie, V. P. (1968). Public money and parochial education: Bishop Hughes, Governor Seward, and the New York school controversy . Cleveland: Case Western Reserve University Press. Lattuca, L. R., & Stark, J. S. (2011). External influences on curriculum: Sociocultural contact. In S. R. Harper & J. F. L. Jackson (Eds.), An introduction to American higher education (pp. 93–128). New York: Routledge. Lazerson, M., & Norton Grubb, W. (1974). Introduction. In M. Lazerson & W. N. Grubb (Eds.), American education and vocationalism: A documentary history 1870–1970 (pp. 1–56). New York: Teachers College Press. Lynch, M. (2018). 10 (more) reasons why the U.S. education system is failing. Education Week , January 26. https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2018/01/29/10-more-reasons-why-the-us-education.html . Last accessed 18 June 2020. Malkin, M. (2013). Lessons from Texas and the revolt against Common Core power grab. Noozhawk , March 3. https://www.noozhawk.com/article/030313_michelle_malkin_texas_common_core_education_standards . Last accessed June 18, 2020. McLaren, P. (2015). Life in schools: An introduction to critical pedagogy in the foundations of education (6th ed.). New York: Routledge. Book Google Scholar Messerli, J. (1971). Horace Mann: A biography . New York: Alfred A. Knopf. Miller, C. C. (2017). Do Preschool Teachers Really Need to Be College Graduates? (April 7). https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/07/upshot/dopreschool-teachers-really-need-to-be-college-graduates.html . National Center for Education Statistics. (2017a). Table 202.20, Percentage of 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old children enrolled in preprimary programs, by level of program, attendance status, and selected child and family characteristics: 2017. Digest of Education Statistics. Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/tables/dt18_202.20.asp . Last accessed 15 Jan 2019. National Center for Education Statistics. (2017b). Table 205.10, Private elementary and secondary school enrollment and private enrollment as a percentage of total enrollment in public and private schools, by region and grade level: Selected years, fall 1995 through fall 2015. Digest of Education Statistics. Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_205.10.asp . Last accessed 29 Jan 2019. National Center for Education Statistics. (2017c). Table 214.10, Number of public school districts and public and private elementary and secondary schools: Selected years, 1869–70 through 2015–16. Digest of Education Statistics. Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_214.10.asp . Last accessed 21 Jan 2019. National Center for Education Statistics. (2018a). NCES Blog: National spending for public schools increases for third consecutive year in school year, 2015–16. https://nces.ed.gov/blogs/nces/post/national-spending-for-public-schools-increases-for-third-consecutive-year-in-school-year-2015-16 . Last accessed 7 Jan 2019. National Center for Education Statistics. (2018b). National postsecondary student aid study: Student financial aid estimates for 2015–16. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018466.pdf . Last accessed 7 Nov 2019. National Center for Education Statistics. (2018c). Number of educational institutions, by level and control of institution: Selected years, 1980–81 through 2016–17. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/tables/dt18_105.50.asp . Last accessed 7 Nov 2019. National Center for Education Statistics. (2019a). Characteristics of postsecondary faculty. The condition of education: letter from the commissioner. Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_csc.asp . Last accessed 20 June 2019. National Center for Education Statistics. (2019b). The condition of education: Preschool and Kindergarten enrollment. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cfa.asp . Last accessed 21 Jan 2019. National Center for Education Statistics. (2019c). The condition of education: Public charter school enrollment. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgb.asp . Last accessed 20 June 2019. National Center for Education Statistics. (2019d). Digest of Education Statistics, 2017 (NCES 2018-070), Chapter 3. U.S. Department of Education. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/ch_3.asp . Last accessed 20 Nov 2019. Newman, A. (2013). Common core: A scheme to rewrite education. New American , August 8. Retrieved 20 Sept 2019, from https://www.thenewamerican.com/culture/education/item/16192-common-core-a-scheme-to-rewrite-education . Last accessed 20 Sept 2019. Newfield, C. (2008). Unmaking the public university: The forty-year assault on the middle class . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Oakes, J. (1985). Keeping track: How schools structure inequality . New Haven: Yale University Press. Office of Postsecondary Education. (2017). Institutional eligibility. In 2017–18 Federal student aid handbook (Vol. 2). Washington, DC: United States Department of Education. https://ifap.ed.gov/ifap/byAwardYear.jsp?type=fsahandbook&awardyear=2017-2018 Oprisko, R. (2012). Superpowers: The American academic elite. Georgetown Public Policy Review , December 3. http://gppreview.com/2012/12/03/superpowers-the-american-academic-elite/ Phi Delta Kappa. (2019). Fifty-first annual poll of the public’s attitudes toward the public schools . Arlington: PDK International. https://pdkpoll.org/ Povich, E. S. (2018). More community colleges are offering bachelor’s degrees – and four-year universities aren’t happy about it. Stateline , April 26. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2018/04/26/more-community-colleges-are-offering-bachelors-degrees Pulliam, J. D., & Van Patten, J. J. (2013). History and social foundations of education (10th ed.). New York: Pearson. Ravitch, D. (1977). The revisionists revised: A critique on the radical attack on the schools . New York: Basic Books. Ravitch, D. (1983). The troubled crusade: American education, 1945–1980 . New York: Basic Books. Reitman, S. W. (1992). The educational messiah complex: American faith in the culturally redemptive power of schooling . Sacramento: Caddo Gap Press. Ross, D. (1991). The origins of American social science . New York: Cambridge University Press. Schaefer, M. B., Malu, K. F., & Yoon, B. (2016). An historical overview of the middle school movement, 1963–2015. Research on Middle Level Education Online, 39 (5), 1–27. Schneider, J. K. (2016). America’s not-so-broken education system: Do U.S. schools really need to be disrupted? The Atlantic.com , June 22. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/06/everything-in-american-education-is-broken/488189/ Schimmel, D., Stellman, L., Conlon, C. K., & Fischer, L. (2015). Teachers and the law (9th ed.). New York: Pearson. Spring, J. H. (1994). Deculturalization and the struggle for equality: A brief history of the education of dominated cultures of the United States . New York: McGraw Hill. Spring, J. H. (2013). The American school, a global context: From the puritans to the Obama administration (9th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. Stewart, K. (2012). The good news club: The Christian right’s stealth assault on America’s children . New York: Public Affairs. United States Department of Education, Office of Innovation and Improvement. (2009). State regulation of private schools . Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www2.ed.gov/admins/comm/choice/regprivschl/regprivschl.pdf United States National Commission on Excellence in Education. (1983). A nation at risk: The imperative for educational reform. A report to the Nation and the Secretary of Education, United States Department of Education . Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Urban, W. J., Wagoner, J. L., Jr., & Gaither, M. (2019). American education: A history (6th ed.). New York: Routledge. White House Initiative on American Indian and Alaska Native Education. (2019). Tribal colleges and universities, U.S. Department of Education. https://sites.ed.gov/whiaiane/tribes-tcus/tribal-colleges-and-universities/ Williams, J. (1983). Reagan blames courts for education decline. Washington Post , June 30. A-2. Yin, A. (2017). Education by the numbers: Statistics show just how profound the inequalities in America’s education system have become. New York Times Magazine , September 8. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/08/magazine/education-by-the-numbers.html Download references AcknowledgmentsFunding from the University of Michigan’s Horace Rackham Graduate School and the UM’s Life Sciences Values and Society Program supported archival research and reproduction contributing to this work. Author informationAuthors and affiliations. College of Education, Health, and Human Services, University of Michigan-Dearborn, Dearborn, MI, USA Paul R. Fossum You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar Corresponding authorCorrespondence to Paul R. Fossum . Editor informationEditors and affiliations. DIPF - Leibniz Institute for Research and Information in Education, Frankfurt/Main, Germany Sieglinde Jornitz Institute of Education, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Münster, Germany Marcelo Parreira do Amaral Rights and permissionsReprints and permissions Copyright information© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG About this entryCite this entry. Fossum, P.R. (2021). The Education System of the United States of America: Overview and Foundations. In: Jornitz, S., Parreira do Amaral, M. (eds) The Education Systems of the Americas. Global Education Systems. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41651-5_14 Download citationDOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41651-5_14 Published : 01 January 2022 Publisher Name : Springer, Cham Print ISBN : 978-3-030-41650-8 Online ISBN : 978-3-030-41651-5 eBook Packages : Education Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education Share this entryAnyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative Policies and ethics - Find a journal

- Track your research

You have successfully logged in but...... your login credentials do not authorize you to access this content in the selected format. Access to this content in this format requires a current subscription or a prior purchase. Please select the WEB or READ option instead (if available). Or consider purchasing the publication. Education at a Glance 2021Characteristics of education systems, oecd indicators.  Education at a Glance is the authoritative source for information on the state of education around the world. It provides data on the structure, finances and performance of education systems across OECD countries and a number of partner economies. More than 100 charts and tables in this publication – as well as links to much more available on the educational database – provide key information on the output of educational institutions; the impact of learning across countries; access, participation and progression in education; the financial resources invested in education; and teachers, the learning environment and the organisation of schools. The 2021 edition includes a focus on equity, investigating how progress through education and the associated learning and labour market outcomes are impacted by dimensions such as gender, socio-economic status, country of birth and regional location. A specific chapter is dedicated to Target 4.5 of the Sustainable Development Goal 4 on equity in education, providing an assessment of where OECD and partner countries stand in providing equal access to quality education at all levels. Two new indicators on the mechanisms and formulas used to allocate public funding to schools and on teacher attrition rate complement this year's edition. English Also available in: French , German  - The State of Global Education

- Money matters for global education

- https://doi.org/10.1787/b35a14e5-en

- Click to access:

- Click to access in HTML WEB

- Click to download PDF - 7.24MB PDF

- Click to download EPUB - 64.13MB ePUB

English Also available in: French - Click to download PDF - 405.67KB PDF

Cite this content as:Author(s) OECD 16 Sept 2021 Typical graduation ages, by level of education (2019) - Click to download XLS XLS

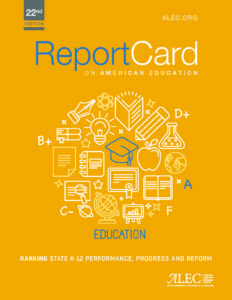

Typical age of entry, by level of education (2019) School year and financial year used for the calculation of indicators, OECD countries School year and financial year used for the calculation of indicators, partner countries Starting and ending age for students in compulsory education and by level of education (2019)  Show/Hide Columns: | State | Overall Grade | ALEC Rank | NAEP Rank | School Choice

Grade | Charter School

Grade | Digital

Learning | Homeschool

Burden | Teacher

Quality | Academic

Standards | Special Award | Per-Pupil

Spending | | | | 47 | -- | F | F | D+ | A | D- | B+ | | $17,510 | | | | 26 | -- | C- | D | D- | B | C | B- | | $9,258 | | | | 22 | -- | D- | D | C | B | C+ | A | | $9,900 | | | | 1 | -- | A | A | C+ | B | D | B | | $7,772 | | | | 25 | -- | F | B | D- | B | D+ | B | | $11,420 | | | | 27 | -- | F | B | D+ | C | D+ | A | | $9,619 | | | | 36 | -- | F | D | F | A | C+ | B | | $19,615 | | | | 5 | -- | C- | A | -- | C | D+ | A | | $21,134 | | | | 37 | -- | F | D | D- | B | B- | B- | | $14,397 | | | | 2 | -- | A | B | A- | C | B+ | A | | $9,176 | | | | 4 | -- | B+ | C | B | B | B- | B+ | | $9,835 | | | | 49 | -- | F | D | D | C | D+ | B | | $13,748 | | | | 41 | -- | C- | F | D | A | D+ | D+ | | $11,148 | | | | 18 | -- | F | C | C | A | C | B+ | | $7,178 | | | | 14 | -- | C+ | D | D- | A | C+ | A | | $14,327 | | | | 3 | -- | B+ | A | B- | A | B- | C+ | | $9,691 | | | | 33 | -- | D- | F | B- | B | D+ | A | | $10,216 | | | | 44 | -- | F | D | D | B | C- | B- | | $9,831 | | | | 11 | -- | D+ | C | B- | C | B+ | B- | | $11,169 | | | | 21 | -- | F | B | D+ | D | B- | A | | $16,986 | | | | 35 | -- | D | D | C | C | D+ | A | | $14,523 | | | | 31 | -- | D | D | C | C | D+ | B+ | | $14,202 | | | | 10 | -- | F | B | C | A | C | B+ | | $11,051 | | | | 15 | -- | F | A | B+ | C | C- | B- | | $12,364 | | | | 30 | -- | F | C | D+ | A | C | C | | $10,385 | | | | 32 | -- | D- | D | D- | B | C | B+ | | $8,692 | | | | 43 | -- | C | F | F | B | F | B+ | | $11,374 | | | | 13 | -- | D+ | C | C | C | C+ | B+ | | $8,717 | | | | 1 | -- | F | F | F | C | D | C+ | | $13,358 | | | | 51 | -- | F | F | F | B | D | C+ | | $12,379 | | | | 38 | -- | D- | D | D | C | D+ | B+ | | $15,535 | | | | 16 | -- | F | C | D- | A | B | A | | $19,041 | | | | 20 | -- | F | C | C | B | C | A | | $9,959 | | | | 6 | -- | B+ | C | B+ | B | C- | B+ | | $8,753 | | | | 23 | -- | F | B | D- | D | B | A | | $22,231 | | | | 28 | -- | D- | C | D | C | B- | C+ | | $11,933 | | | | 8 | -- | C- | C | C+ | A | D+ | A | | $8,091 | | | | 46 | -- | F | D | C | C | D- | B | | $10,823 | | | | 17 | -- | C+ | C | D | D | C | B | | $15,165 | | | | 29 | -- | D- | D | C | D | B | A | | $16,082 | | | | 12 | -- | D- | B | B- | C | C+ | B | | $10,045 | | | | 48 | -- | D | F | C | C | F | B | | $9,355 | | | | 24 | -- | D- | C | F | C | B | A | | $8,876 | | | | 19 | -- | F | C | B- | A | B- | C- | | $9,352 | | | | 9 | -- | D- | C | A- | B | C | A- | | $7,006 | | | | 42 | -- | D- | F | B | D | C+ | C- | | $11,435 | | | | 40 | -- | C+ | F | D- | D | D | B+ | | $19,023 | | | | 34 | -- | F | D | B- | D | C- | B | | $11,484 | | | | 7 | -- | A | C | D | B | D+ | A | | $11,664 | | | | 45 | -- | F | F | B- | D | C+ | B | | $11,424 | | | | 39 | -- | F | D | C- | B | D | B | | $16,431 |  Featured Publication:Report card on american education: 22nd edition. The status quo is not working. Whether by international comparisons, state and national proficiency measures, civic literacy rates, or career preparedness, American students are falling behind. The 22nd edition of the Report Card on American Education ranks states on their K-12 education and policy performance. Keep up-to-date on the latest campaigns & news The World Bank Group is the largest financier of education in the developing world, working in 94 countries and committed to helping them reach SDG4: access to inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all by 2030. Education is a human right, a powerful driver of development, and one of the strongest instruments for reducing poverty and improving health, gender equality, peace, and stability. It delivers large, consistent returns in terms of income, and is the most important factor to ensure equity and inclusion. For individuals, education promotes employment, earnings, health, and poverty reduction. Globally, there is a 9% increase in hourly earnings for every extra year of schooling . For societies, it drives long-term economic growth, spurs innovation, strengthens institutions, and fosters social cohesion. Education is further a powerful catalyst to climate action through widespread behavior change and skilling for green transitions. Developing countries have made tremendous progress in getting children into the classroom and more children worldwide are now in school. But learning is not guaranteed, as the 2018 World Development Report (WDR) stressed. Making smart and effective investments in people’s education is critical for developing the human capital that will end extreme poverty. At the core of this strategy is the need to tackle the learning crisis, put an end to Learning Poverty , and help youth acquire the advanced cognitive, socioemotional, technical and digital skills they need to succeed in today’s world. In low- and middle-income countries, the share of children living in Learning Poverty (that is, the proportion of 10-year-old children that are unable to read and understand a short age-appropriate text) increased from 57% before the pandemic to an estimated 70% in 2022. However, learning is in crisis. More than 70 million more people were pushed into poverty during the COVID pandemic, a billion children lost a year of school , and three years later the learning losses suffered have not been recouped . If a child cannot read with comprehension by age 10, they are unlikely to become fluent readers. They will fail to thrive later in school and will be unable to power their careers and economies once they leave school. The effects of the pandemic are expected to be long-lasting. Analysis has already revealed deep losses, with international reading scores declining from 2016 to 2021 by more than a year of schooling. These losses may translate to a 0.68 percentage point in global GDP growth. The staggering effects of school closures reach beyond learning. This generation of children could lose a combined total of US$21 trillion in lifetime earnings in present value or the equivalent of 17% of today’s global GDP – a sharp rise from the 2021 estimate of a US$17 trillion loss. Action is urgently needed now – business as usual will not suffice to heal the scars of the pandemic and will not accelerate progress enough to meet the ambitions of SDG 4. We are urging governments to implement ambitious and aggressive Learning Acceleration Programs to get children back to school, recover lost learning, and advance progress by building better, more equitable and resilient education systems. Last Updated: Mar 25, 2024 The World Bank’s global education strategy is centered on ensuring learning happens – for everyone, everywhere. Our vision is to ensure that everyone can achieve her or his full potential with access to a quality education and lifelong learning. To reach this, we are helping countries build foundational skills like literacy, numeracy, and socioemotional skills – the building blocks for all other learning. From early childhood to tertiary education and beyond – we help children and youth acquire the skills they need to thrive in school, the labor market and throughout their lives. Investing in the world’s most precious resource – people – is paramount to ending poverty on a livable planet. Our experience across more than 100 countries bears out this robust connection between human capital, quality of life, and economic growth: when countries strategically invest in people and the systems designed to protect and build human capital at scale, they unlock the wealth of nations and the potential of everyone. Building on this, the World Bank supports resilient, equitable, and inclusive education systems that ensure learning happens for everyone. We do this by generating and disseminating evidence, ensuring alignment with policymaking processes, and bridging the gap between research and practice. The World Bank is the largest source of external financing for education in developing countries, with a portfolio of about $26 billion in 94 countries including IBRD, IDA and Recipient-Executed Trust Funds. IDA operations comprise 62% of the education portfolio. The investment in FCV settings has increased dramatically and now accounts for 26% of our portfolio. World Bank projects reach at least 425 million students -one-third of students in low- and middle-income countries. The World Bank’s Approach to Education Five interrelated pillars of a well-functioning education system underpin the World Bank’s education policy approach: - Learners are prepared and motivated to learn;

- Teachers are prepared, skilled, and motivated to facilitate learning and skills acquisition;

- Learning resources (including education technology) are available, relevant, and used to improve teaching and learning;

- Schools are safe and inclusive; and

- Education Systems are well-managed, with good implementation capacity and adequate financing.

The Bank is already helping governments design and implement cost-effective programs and tools to build these pillars. Our Principles: - We pursue systemic reform supported by political commitment to learning for all children.

- We focus on equity and inclusion through a progressive path toward achieving universal access to quality education, including children and young adults in fragile or conflict affected areas , those in marginalized and rural communities, girls and women , displaced populations, students with disabilities , and other vulnerable groups.

- We focus on results and use evidence to keep improving policy by using metrics to guide improvements.

- We want to ensure financial commitment commensurate with what is needed to provide basic services to all.

- We invest wisely in technology so that education systems embrace and learn to harness technology to support their learning objectives.

Laying the groundwork for the future Country challenges vary, but there is a menu of options to build forward better, more resilient, and equitable education systems. Countries are facing an education crisis that requires a two-pronged approach: first, supporting actions to recover lost time through remedial and accelerated learning; and, second, building on these investments for a more equitable, resilient, and effective system. Recovering from the learning crisis must be a political priority, backed with adequate financing and the resolve to implement needed reforms. Domestic financing for education over the last two years has not kept pace with the need to recover and accelerate learning. Across low- and lower-middle-income countries, the average share of education in government budgets fell during the pandemic , and in 2022 it remained below 2019 levels. The best chance for a better future is to invest in education and make sure each dollar is put toward improving learning. In a time of fiscal pressure, protecting spending that yields long-run gains – like spending on education – will maximize impact. We still need more and better funding for education. Closing the learning gap will require increasing the level, efficiency, and equity of education spending—spending smarter is an imperative. - Education technology can be a powerful tool to implement these actions by supporting teachers, children, principals, and parents; expanding accessible digital learning platforms, including radio/ TV / Online learning resources; and using data to identify and help at-risk children, personalize learning, and improve service delivery.

Looking ahead We must seize this opportunity to reimagine education in bold ways. Together, we can build forward better more equitable, effective, and resilient education systems for the world’s children and youth. Accelerating Improvements Supporting countries in establishing time-bound learning targets and a focused education investment plan, outlining actions and investments geared to achieve these goals. Launched in 2020, the Accelerator Program works with a set of countries to channel investments in education and to learn from each other. The program coordinates efforts across partners to ensure that the countries in the program show improvements in foundational skills at scale over the next three to five years. These investment plans build on the collective work of multiple partners, and leverage the latest evidence on what works, and how best to plan for implementation. Countries such as Brazil (the state of Ceará) and Kenya have achieved dramatic reductions in learning poverty over the past decade at scale, providing useful lessons, even as they seek to build on their successes and address remaining and new challenges. Universalizing Foundational Literacy Readying children for the future by supporting acquisition of foundational skills – which are the gateway to other skills and subjects. The Literacy Policy Package (LPP) consists of interventions focused specifically on promoting acquisition of reading proficiency in primary school. These include assuring political and technical commitment to making all children literate; ensuring effective literacy instruction by supporting teachers; providing quality, age-appropriate books; teaching children first in the language they speak and understand best; and fostering children’s oral language abilities and love of books and reading. Advancing skills through TVET and Tertiary Ensuring that individuals have access to quality education and training opportunities and supporting links to employment. Tertiary education and skills systems are a driver of major development agendas, including human capital, climate change, youth and women’s empowerment, and jobs and economic transformation. A comprehensive skill set to succeed in the 21st century labor market consists of foundational and higher order skills, socio-emotional skills, specialized skills, and digital skills. Yet most countries continue to struggle in delivering on the promise of skills development. The World Bank is supporting countries through efforts that address key challenges including improving access and completion, adaptability, quality, relevance, and efficiency of skills development programs. Our approach is via multiple channels including projects, global goods, as well as the Tertiary Education and Skills Program . Our recent reports including Building Better Formal TVET Systems and STEERing Tertiary Education provide a way forward for how to improve these critical systems. Addressing Climate Change Mainstreaming climate education and investing in green skills, research and innovation, and green infrastructure to spur climate action and foster better preparedness and resilience to climate shocks. Our approach recognizes that education is critical for achieving effective, sustained climate action. At the same time, climate change is adversely impacting education outcomes. Investments in education can play a huge role in building climate resilience and advancing climate mitigation and adaptation. Climate change education gives young people greater awareness of climate risks and more access to tools and solutions for addressing these risks and managing related shocks. Technical and vocational education and training can also accelerate a green economic transformation by fostering green skills and innovation. Greening education infrastructure can help mitigate the impact of heat, pollution, and extreme weather on learning, while helping address climate change. Examples of this work are projects in Nigeria (life skills training for adolescent girls), Vietnam (fostering relevant scientific research) , and Bangladesh (constructing and retrofitting schools to serve as cyclone shelters). Strengthening Measurement Systems Enabling countries to gather and evaluate information on learning and its drivers more efficiently and effectively. The World Bank supports initiatives to help countries effectively build and strengthen their measurement systems to facilitate evidence-based decision-making. Examples of this work include: (1) The Global Education Policy Dashboard (GEPD) : This tool offers a strong basis for identifying priorities for investment and policy reforms that are suited to each country context by focusing on the three dimensions of practices, policies, and politics. - Highlights gaps between what the evidence suggests is effective in promoting learning and what is happening in practice in each system; and

- Allows governments to track progress as they act to close the gaps.

The GEPD has been implemented in 13 education systems already – Peru, Rwanda, Jordan, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Mozambique, Islamabad, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sierra Leone, Niger, Gabon, Jordan and Chad – with more expected by the end of 2024. (2) Learning Assessment Platform (LeAP) : LeAP is a one-stop shop for knowledge, capacity-building tools, support for policy dialogue, and technical staff expertise to support student achievement measurement and national assessments for better learning. Supporting Successful Teachers Helping systems develop the right selection, incentives, and support to the professional development of teachers. Currently, the World Bank Education Global Practice has over 160 active projects supporting over 18 million teachers worldwide, about a third of the teacher population in low- and middle-income countries. In 12 countries alone, these projects cover 16 million teachers, including all primary school teachers in Ethiopia and Turkey, and over 80% in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Vietnam. A World Bank-developed classroom observation tool, Teach, was designed to capture the quality of teaching in low- and middle-income countries. It is now 3.6 million students. While Teach helps identify patterns in teacher performance, Coach leverages these insights to support teachers to improve their teaching practice through hands-on in-service teacher professional development (TPD). Our recent report on Making Teacher Policy Work proposes a practical framework to uncover the black box of effective teacher policy and discusses the factors that enable their scalability and sustainability. Supporting Education Finance Systems Strengthening country financing systems to mobilize resources for education and make better use of their investments in education. Our approach is to bring together multi-sectoral expertise to engage with ministries of education and finance and other stakeholders to develop and implement effective and efficient public financial management systems; build capacity to monitor and evaluate education spending, identify financing bottlenecks, and develop interventions to strengthen financing systems; build the evidence base on global spending patterns and the magnitude and causes of spending inefficiencies; and develop diagnostic tools as public goods to support country efforts. Working in Fragile, Conflict, and Violent (FCV) Contexts The massive and growing global challenge of having so many children living in conflict and violent situations requires a response at the same scale and scope. Our education engagement in the Fragility, Conflict and Violence (FCV) context, which stands at US$5.35 billion, has grown rapidly in recent years, reflecting the ever-increasing importance of the FCV agenda in education. Indeed, these projects now account for more than 25% of the World Bank education portfolio. Education is crucial to minimizing the effects of fragility and displacement on the welfare of youth and children in the short-term and preventing the emergence of violent conflict in the long-term. Support to Countries Throughout the Education Cycle Our support to countries covers the entire learning cycle, to help shape resilient, equitable, and inclusive education systems that ensure learning happens for everyone. The ongoing Supporting Egypt Education Reform project , 2018-2025, supports transformational reforms of the Egyptian education system, by improving teaching and learning conditions in public schools. The World Bank has invested $500 million in the project focused on increasing access to quality kindergarten, enhancing the capacity of teachers and education leaders, developing a reliable student assessment system, and introducing the use of modern technology for teaching and learning. Specifically, the share of Egyptian 10-year-old students, who could read and comprehend at the global minimum proficiency level, increased to 45 percent in 2021. In Nigeria , the $75 million Edo Basic Education Sector and Skills Transformation (EdoBESST) project, running from 2020-2024, is focused on improving teaching and learning in basic education. Under the project, which covers 97 percent of schools in the state, there is a strong focus on incorporating digital technologies for teachers. They were equipped with handheld tablets with structured lesson plans for their classes. Their coaches use classroom observation tools to provide individualized feedback. Teacher absence has reduced drastically because of the initiative. Over 16,000 teachers were trained through the project, and the introduction of technology has also benefited students. Through the $235 million School Sector Development Program in Nepal (2017-2022), the number of children staying in school until Grade 12 nearly tripled, and the number of out-of-school children fell by almost seven percent. During the pandemic, innovative approaches were needed to continue education. Mobile phone penetration is high in the country. More than four in five households in Nepal have mobile phones. The project supported an educational service that made it possible for children with phones to connect to local radio that broadcast learning programs. From 2017-2023, the $50 million Strengthening of State Universities in Chile project has made strides to improve quality and equity at state universities. The project helped reduce dropout: the third-year dropout rate fell by almost 10 percent from 2018-2022, keeping more students in school. The World Bank’s first Program-for-Results financing in education was through a $202 million project in Tanzania , that ran from 2013-2021. The project linked funding to results and aimed to improve education quality. It helped build capacity, and enhanced effectiveness and efficiency in the education sector. Through the project, learning outcomes significantly improved alongside an unprecedented expansion of access to education for children in Tanzania. From 2013-2019, an additional 1.8 million students enrolled in primary schools. In 2019, the average reading speed for Grade 2 students rose to 22.3 words per minute, up from 17.3 in 2017. The project laid the foundation for the ongoing $500 million BOOST project , which supports over 12 million children to enroll early, develop strong foundational skills, and complete a quality education. The $40 million Cambodia Secondary Education Improvement project , which ran from 2017-2022, focused on strengthening school-based management, upgrading teacher qualifications, and building classrooms in Cambodia, to improve learning outcomes, and reduce student dropout at the secondary school level. The project has directly benefited almost 70,000 students in 100 target schools, and approximately 2,000 teachers and 600 school administrators received training. The World Bank is co-financing the $152.80 million Yemen Restoring Education and Learning Emergency project , running from 2020-2024, which is implemented through UNICEF, WFP, and Save the Children. It is helping to maintain access to basic education for many students, improve learning conditions in schools, and is working to strengthen overall education sector capacity. In the time of crisis, the project is supporting teacher payments and teacher training, school meals, school infrastructure development, and the distribution of learning materials and school supplies. To date, almost 600,000 students have benefited from these interventions. The $87 million Providing an Education of Quality in Haiti project supported approximately 380 schools in the Southern region of Haiti from 2016-2023. Despite a highly challenging context of political instability and recurrent natural disasters, the project successfully supported access to education for students. The project provided textbooks, fresh meals, and teacher training support to 70,000 students, 3,000 teachers, and 300 school directors. It gave tuition waivers to 35,000 students in 118 non-public schools. The project also repaired 19 national schools damaged by the 2021 earthquake, which gave 5,500 students safe access to their schools again. In 2013, just 5% of the poorest households in Uzbekistan had children enrolled in preschools. Thanks to the Improving Pre-Primary and General Secondary Education Project , by July 2019, around 100,000 children will have benefitted from the half-day program in 2,420 rural kindergartens, comprising around 49% of all preschool educational institutions, or over 90% of rural kindergartens in the country. In addition to working closely with governments in our client countries, the World Bank also works at the global, regional, and local levels with a range of technical partners, including foundations, non-profit organizations, bilaterals, and other multilateral organizations. Some examples of our most recent global partnerships include: UNICEF, UNESCO, FCDO, USAID, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: Coalition for Foundational Learning The World Bank is working closely with UNICEF, UNESCO, FCDO, USAID, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation as the Coalition for Foundational Learning to advocate and provide technical support to ensure foundational learning. The World Bank works with these partners to promote and endorse the Commitment to Action on Foundational Learning , a global network of countries committed to halving the global share of children unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10 by 2030. Australian Aid, Bernard van Leer Foundation, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Canada, Echida Giving, FCDO, German Cooperation, William & Flora Hewlett Foundation, Conrad Hilton Foundation, LEGO Foundation, Porticus, USAID: Early Learning Partnership The Early Learning Partnership (ELP) is a multi-donor trust fund, housed at the World Bank. ELP leverages World Bank strengths—a global presence, access to policymakers and strong technical analysis—to improve early learning opportunities and outcomes for young children around the world. We help World Bank teams and countries get the information they need to make the case to invest in Early Childhood Development (ECD), design effective policies and deliver impactful programs. At the country level, ELP grants provide teams with resources for early seed investments that can generate large financial commitments through World Bank finance and government resources. At the global level, ELP research and special initiatives work to fill knowledge gaps, build capacity and generate public goods. UNESCO, UNICEF: Learning Data Compact UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank have joined forces to close the learning data gaps that still exist and that preclude many countries from monitoring the quality of their education systems and assessing if their students are learning. The three organizations have agreed to a Learning Data Compact , a commitment to ensure that all countries, especially low-income countries, have at least one quality measure of learning by 2025, supporting coordinated efforts to strengthen national assessment systems. UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS): Learning Poverty Indicator Aimed at measuring and urging attention to foundational literacy as a prerequisite to achieve SDG4, this partnership was launched in 2019 to help countries strengthen their learning assessment systems, better monitor what students are learning in internationally comparable ways and improve the breadth and quality of global data on education. FCDO, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: EdTech Hub Supported by the UK government’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), in partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the EdTech Hub is aimed at improving the quality of ed-tech investments. The Hub launched a rapid response Helpdesk service to provide just-in-time advisory support to 70 low- and middle-income countries planning education technology and remote learning initiatives. MasterCard Foundation Our Tertiary Education and Skills global program, launched with support from the Mastercard Foundation, aims to prepare youth and adults for the future of work and society by improving access to relevant, quality, equitable reskilling and post-secondary education opportunities. It is designed to reframe, reform, and rebuild tertiary education and skills systems for the digital and green transformation.  Choosing our Future: Education for Climate Action Bridging the AI divide: Breaking down barriers to ensure women’s leadership and participation in the Fifth Industrial Revolution Common challenges and tailored solutions: How policymakers are strengthening early learning systems across the world Compulsory education boosts learning outcomes and climate actionAreas of focus. Data & Measurement Early Childhood Development Financing Education Foundational Learning Fragile, Conflict & Violent Contexts Girls’ Education Inclusive Education Skills Development Technology (EdTech) Tertiary Education Initiatives- Show More +

- Invest in Childcare

- Global Education Policy Dashboard

- Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel

- Show Less -

Collapse and Recovery: How the COVID-19 Pandemic Eroded Human Capital and What to Do About It BROCHURES & FACT SHEETSFlyer: Education Factsheet - May 2024 Publication: Realizing Education's Promise: A World Bank Retrospective – August 2023 Flyer: Education and Climate Change - November 2022 Brochure: Learning Losses - October 2022 STAY CONNECTED Human Development TopicsAround the bank group. Find out what the Bank Group's branches are doing in education  Global Education Newsletter - June 2024What's happening in the World Bank Education Global Practice? Read to learn more.  Learning Can't Wait: A commitment to education in Latin America and the ...A new IDB-World Bank report describes challenges and priorities to address the educational crisis.  Human Capital ProjectThe Human Capital Project is a global effort to accelerate more and better investments in people for greater equity and economic growth.  Impact EvaluationsResearch that measures the impact of education policies to improve education in low and middle income countries.  Education VideosWatch our latest videos featuring our projects across the world Additional ResourcesSkills & Workforce Development Technology (EdTech) This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .  The State of Education: Rebuilding a More Equitable SystemCovid-19 has exposed long-standing inequities in america’s education system.. The pandemic’s toll on our education system has had a broader effect on academic regressions than initially predicted. And the most vulnerable learners—students of color, those from low socioeconomic backgrounds, and students with additional learning needs—have been impacted the most. While the pandemic has exacerbated existing disparities, it’s also presented a unique opportunity to dramatically overhaul our education system. We convened education advocates and practitioners, from both K–12 and higher education, to explain how the disruption of the pandemic is pushing forward long-overdue pedagogical reform. And we outlined the innovative solutions that should be implemented to create an equitable learning environment for all students. Atlantic subscribers enjoy access to exclusive sessions and experiences.Sign up to receive updates. Subject to The Atlantic's Privacy Policy and Terms and Conditions . Underwritten by Dr. Mildred GarcíaPresident, American Association of State Colleges and Universities Adam HarrisStaff writer, The Atlantic Dr. John B. King, Jr.President and CEO, The Education Trust Dr. Sonja SantelisesCEO, Baltimore City Schools Susan SaulnyContributor, AtlanticLIVE Agenda Mar 3Virtual or in-person. Virtual / In-Person Where Does Education Reform Go from Here?A session presented by bill & melinda gates foundation. Produced by our underwriter and not The Atlantic ’s editorial team.  Implementing SolutionsClosing remarks, event details, virtual event. Wednesday, March 3, 2021 1:00 pm EDT Subscribe to The AtlanticUnlock unlimited access to The Atlantic, including exclusive events for subscribers. Join us today and help ensure a bright future for independent journalism. Related EventsThe education summit. October 27, 2022 Washington, D.C. or Virtual October 26, 2021 Virtual Event May 14, 2019 Washington, D.C. Education Summit 2018May 1, 2018 Washington, D.C. Understanding the American Education System The American education system offers a rich field of choices for international students. There is such an array of schools, programs and locations that the choices may overwhelm students, even those from the U.S. As you begin your school search, it’s important to familiarize yourself with the American education system. Understanding the system will help you narrow your choices and develop your education plan. The Educational StructurePrimary and secondary school. Prior to higher education, American students attend primary and secondary school for a combined total of 12 years. These years are referred to as the first through twelfth grades.  Around age six, U.S. children begin primary school, which is most commonly called “elementary school.” They attend five or six years and then go onto secondary school. Secondary school consists of two programs: the first is “middle school” or “junior high school” and the second program is “high school.” A diploma or certificate is awarded upon graduation from high school. After graduating high school (12th grade), U.S. students may go on to college or university. College or university study is known as “higher education.” Grading SystemJust like American students, you will have to submit your academic transcripts as part of your application for admission to university or college. Academic transcripts are official copies of your academic work. In the U.S. this includes your “grades” and “grade point average” (GPA), which are measurements of your academic achievement. Courses are commonly graded using percentages, which are converted into letter grades. The grading system and GPA in the U.S. can be confusing, especially for international students. The interpretation of grades has a lot of variation. For example, two students who attended different schools both submit their transcripts to the same university. They both have 3.5 GPAs, but one student attended an average high school, while the other attended a prestigious school that was academically challenging. The university might interpret their GPAs differently because the two schools have dramatically different standards. Therefore, there are some crucial things to keep in mind: - You should find out the U.S. equivalent of the last level of education you completed in your home country.

- Pay close attention to the admission requirements of each university and college, as well as individual degree programs, which may have different requirements than the university.

- Regularly meet with an educational advisor or guidance counselor to make sure you are meeting the requirements.

Your educational advisor or guidance counselor will be able to advise you on whether or not you must spend an extra year or two preparing for U.S. university admission. If an international student entered a U.S. university or college prior to being eligible to attend university in their own country, some countries’ governments and employers may not recognize the students’ U.S. education. Academic YearThe school calendar usually begins in August or September and continues through May or June. The majority of new students begin in autumn, so it is a good idea for international students to also begin their U.S. university studies at this time. There is a lot of excitement at the beginning of the school year and students form many great friendships during this time, as they are all adjusting to a new phase of academic life. Additionally, many courses are designed for students to take them in sequence, starting in autumn and continuing through the year. The academic year at many schools is composed of two terms called “semesters.” (Some schools use a three-term calendar known as the “trimester” system.) Still, others further divide the year into the quarter system of four terms, including an optional summer session. Basically, if you exclude the summer session, the academic year is either comprised of two semesters or three quarter terms. The U.S. Higher Education System: Levels of Study- First Level: Undergraduate