Finding the Thesis

You have plucked one idea (or closely related group of ideas) out of all of your possible ideas to focus on. Congratulations! Now what? Well, now you might write about that topic to explore what you want to say about it. Or, you might already have some idea about what point you want to make about it. If you are in the latter position, you may want to develop a working thesis to guide your drafting process.

What Is a Working Thesis?

A thesis is the controlling idea of a text (often an arguable idea—you will learn more about this in a bit). Depending on the type of text you are creating, all of the discussion in that text will serve to develop, explore multiple angles of, and/or support that thesis.

But how can we know, before getting any of the paper written, exactly what thesis the sources we find and the conversations we have will support? Often, we can’t. The closest we can get in these cases is a working thesis, which is a best guess at what the thesis is likely to be based on the information we are working with at this time. The main idea of it may not change, but the specifics are probably going to be tweaked a bit as you complete a draft and do research.

So, let’s look at one of the examples from “ Strategies for Getting Started ” from the “Prewriting—Generating Ideas” section of this book: the cluster about the broad central idea of danger. If the main idea is “danger,” maybe the conversation you decide you want to have about it after clustering is that sometimes people step into danger intentionally in order to prove ourselves in some way. Next, you might make a list of possible thesis statements. For the sake of example, let’s say this is for an assignment in response to the film The Hunger Games . Some thesis statements that fit this situation might look like this:

- Ultimately, The Hunger Games is a film about facing fears.

- In the 2012 film The Hunger Games , the main character’s fear of losing her sister drives her to face a different set of dangers.

- Katniss Everdeen, the heroine of The Hunger Games , creates as much danger for herself as she faces from others over the course of the film.

If you were writing a summary, the first example in that list might be a good thesis to work with. If you were writing a review, the second one might be the better option. Let’s say, though, that you’ve been assigned to write a more traditional college essay, something a little more focused on analysis. In that case, the final example in this list looks like a good working thesis. It might not be quite the same as the thesis you end up with in later drafts, but it looks like a strong idea to focus your ideas around while you’re first getting them on the page.

The Word on College Reading and Writing Copyright © by Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Page Content

- Sidebar Content

- Main Navigation

- Quick links

- All TIP Sheets

- Writing a Summary

- Writing Paragraphs

- Writing an Analogy

- Writing a Descriptive Essay

- Writing a Persuasive Essay

- Writing a Compare/Contrast Paper

- Writing Cause and Effect Papers

- Writing a Process Paper

- Writing a Classification Paper

- Definitions of Writing Terms

- How to Write Clearly

- Active and Passive Voice

- Developing a Thesis and Supporting Arguments

- Writing Introductions & Conclusions

- How to Structure an Essay: Avoiding Six Weaknesses in Papers

- Writing Book Reports

- Writing about Literature

- Writing about Non-Fiction Books

- Poetry: Meter and Related Topics

- Revising and Editing

- Proofreading

Writing About Non-Fiction Books

TIP Sheet WRITING ABOUT NON-FICTION BOOKS

At some point in your college career you may be asked to review a non-fiction book to enable you to learn more about some aspect of your course work. The assignment is demanding because you are required to describe and evaluate an author's contribution to a subject that you may know little about. How should you proceed?

Your instructor will usually offer some guidance, such as a suggested list of books or some guidelines to follow in selecting a work. Generally, you should try to find a relatively recent work of about 200-350 pages on some aspect of the course that particularly interests you.

Describe and evaluate You are expected to describe the book, that is, to summarize some major points of interest, and to evaluate it, that is, to make judgments about it. The areas to address include the following:

Description

- Information about the author

- Background information about the book

- Author's purpose-to inform? Entertain? Persuade?

- Author's thesis

- Organization

- Other reviews

- Scholarship

- Strengths and weaknesses

Later you may decide to omit some of these points. Their order may be changed, with more important or striking matters appearing first. Usually the descriptive section appears first in non-fiction reviews, especially in scholarly journals. All these organizational decisions are subjective and can be revised as needed.

While reading the book, take notes of the passages and their page numbers that relate to how you can describe and evaluate the work. In particular, be on the lookout for thesis statements, chapter summaries, striking quotations, discussions of methodology, conclusions, and author's recommendations. If you question whether or not to take a particular note, remember that it would be wiser to err on the side of having too many, rather than too few. You can always eliminate notes that appear unnecessary.

Points of description Information about the author may appear on the book jacket or may be obtained or inferred from what is written in the preface. In order to determine to what extent the author is an authority on the subject, you should do some library research into the author's present position, background, experience, and qualifications. Biographical sources such as the Biography Center in the GaleNet database will help you find this information. It need not be much, perhaps just a sentence; at most, it might consist of a short paragraph.

Background information about a book consists of the historical, sociological, economic, scientific or other circumstances that may have influenced or contributed to its publication. This information may have some bearing on the book's importance or interest.

Often the author's purpose –to amuse, inform, persuade-will be apparent from the preface or introduction.

The thesis or central idea of the book will probably be stated in the introduction or the conclusion. To gain an overview of the book that will help you realize its purpose and main ideas, read the preface and the introductory and concluding chapters first.

The organization of non-fiction depends partly on what kind of non-fiction it is-philosophy? Biology?–and partly on the author's purpose. History, for example, might be organized either chronologically or around central issues. Or, if the author's purpose is to challenge a widely-held position, he may choose to refute ideas point-by-point. Look at the table of contents and, as you read, refer back to it.

Because so much depends on your audience, the summary may be one of the most difficult parts of the review to write. Are you writing only for your instructor who has probably already read, or is familiar with, the book? Are you writing for your classmates who have not read it? Or are you writing for other people who are not in the course and are therefore unfamiliar with the subject? Your instructor can tell you what audience the paper should address. Then you will be able to judge how thorough your summary should be and whether or not terms should be defined and points explained in detail.

Points of evaluation At the same time that you gather information to describe the work, you should be thinking about your evaluation of it. Read a few other reviews of this book to inform your own opinion–what points did other reviewers address? Were professional reviewers unanimous in their evaluations, or did their opinions differ? Of course, any ideas or quotations obtained from these reviews should be attributed to their owners in your paper. To consult published reviews of the book, ask the reference librarian to help you find an appropriate index, or check an online database. Following is a partial list of the databases available to Butte College students:

- Proquest Direct–for general disciplines including health, humanities, sciences, social sciences, arts, business, education, women's and multicultural issues.

- SIRS Researcher–for topics including science, history, politics, and global issues.

- Wilson Web–for biographies, obituaries, science, education, current events, and social science.

- GaleNet–for biographies, authors, history, science, and literature.

- Health Reference Center–for topics in health, medicine, and nursing.

Some online databases offer full text articles; others offer abstracts (summaries) and information on how to find the full text in other publications; you can quickly scan abstracts to determine which articles are most likely to be useful to you. Advanced search features allow you to search using Boolean operators (and, or, not) for either full texts or abstracts. You can also narrow your search to scholarly journals for better search results. (From the Butte College home page, http://www.butte.edu, use the library links-search For Articles and select a database from the alphabetical list.)

The print-version Reader's Guide to Periodical Literature (in the Butte College Library, 1959 to the present) may also be helpful. This index also summarizes and tells you where to find the texts. The names and dates of the publications in which they appear are listed, and you should be able to refer to your selected reviews with little effort. The different indexes are usually organized by year, but keep in mind that a work published late in the year might not be reviewed until the following year.

You may find it difficult to judge the scholarship of a work or an author's expertise because of your limited understanding of the subject. But it does not require highly specialized knowledge to note what sources the author uses (look for the notes or bibliography sections), how much and what kind of evidence he provides, or how he analyzes data and justifies his conclusions. Read carefully to identify omissions, discernible bias, or unsupported generalizations. For example, someone reviewing a work entitled War in the Falklands would have little difficulty pointing out that this account of the 1982 war between Britain and Argentina is pro-British, containing little information about the Argentine politicians, participants, and purposes.

When considering a book's strengths and weaknesses , discuss the following points:

- The tone and style of the writing

- The importance of the book in its field

- The value of the book for its intended audience

- The effectiveness of the author's argument

- The soundness of the author's conclusions

- The practicality of the author's recommendations.

Your discussion the book's strengths and weaknesses may overlap with your discussion of scholarship. Plan to sort this out when revising your review so that your paper concludes with your general reaction. If your overall evaluation is favorable, admit the book's few weaknesses first and conclude with its many strong areas. If unfavorable, name the book's strengths first and conclude with its numerous weaknesses.

Mention any particularly interesting or memorable points or passages, and support your opinions with references to the book, but use quotations sparingly.

In your evaluation, you might reflect on how the book relates to your course. Consider what issues, ideas, or institutions the author criticizes or defends. Note the methodology and evaluate how it shapes or restricts the topic. Also, evaluate how well the author has added to your knowledge and understanding of the subject, particularly how it supplements the ideas in the textbook and the views of your instructor.

Home | Calendars | Library | Bookstore | Directory | Apply Now | Search for Classes | Register | Online Classes | MyBC Portal MyBC -->

Butte College | 3536 Butte Campus Drive, Oroville CA 95965 | General Information (530) 895-2511

Reading Skills

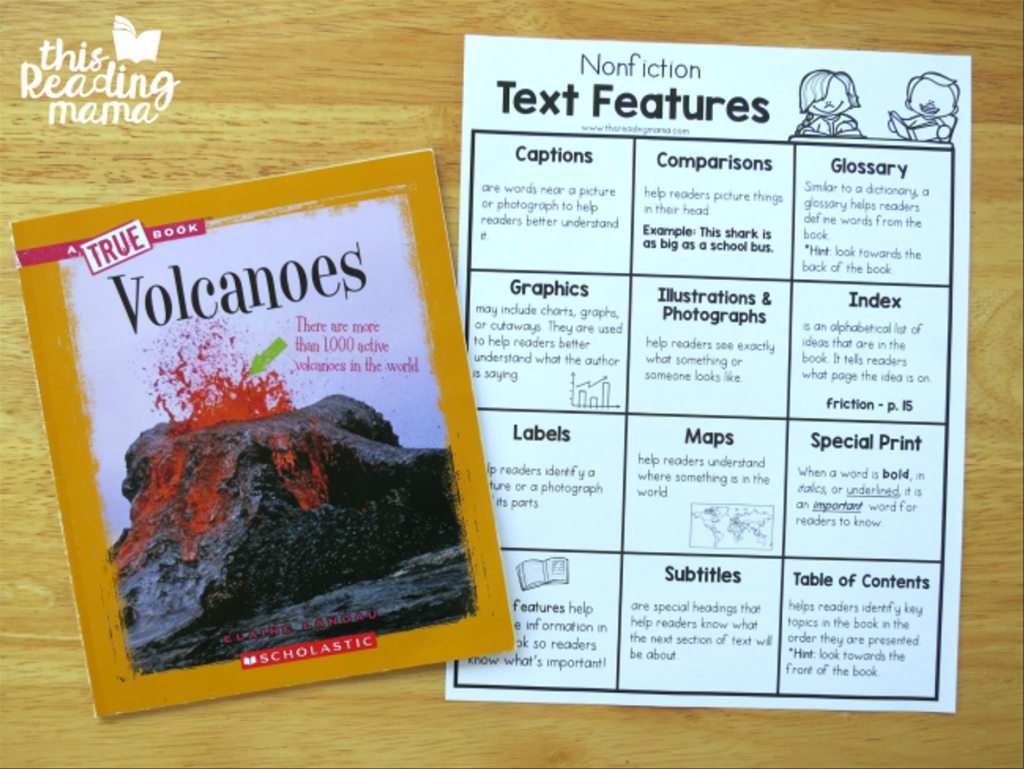

Analyzing the text structure of non-fiction texts.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: June 26, 2023

Introduction

Exploring the world of non-fiction is like embarking on an exciting treasure hunt. Each piece of non-fiction literature presents a wealth of knowledge and perspectives to uncover. A crucial tool on this quest? Understanding non-fiction text structure. Grasping this concept can transform your reading experience, providing you a map to navigate the text’s content more efficiently.

What is Text Structure?

Text structure is how an author sets up what they’re writing. Think of it like a builder using a plan to make a house. An author uses a certain structure to share their thoughts in a clear way. This could be telling events in order they happened for a history story, showing a cause and then its effect for a science paper, laying out a problem and then its solution for a persuasive article, or looking at similarities and differences in a critical review.

Authors use these structures to make their text make sense and guide their readers. Knowing the text structure helps readers guess what comes next, understand complex ideas, and connect better with the text. It’s like a hidden support that keeps a text together and gives it its aim and meaning.

Why Should Readers Analyze Text Structure?

Analyzing text structure is like looking under the hood of a car; it shows us how things work and lets us see the hard work that goes into making it. When we look into how a text is structured, we get a chance to understand how the author thinks and how they built their story or argument. This doesn’t just help us understand the text better; it also improves our ability to think critically and relate to others

By spotting patterns, picking out main ideas, and getting the flow of thoughts, readers can feel more connected to the text, making reading more enjoyable. Plus, analyzing text structure helps readers have good conversations, write better essays, and, in a bigger sense, be more critical when they take in information. So, looking at text structure gives readers useful skills that they can use not just in school, but also in their daily life.

Common Text Structures

Understanding non-fiction texts involves recognizing their underlying structure. Let’s explore five of the most common text structures found in non-fiction:

- Cause and Effect

- Problem and Solution

- Description

- Compare and Contrast

Cause and Effect Text Structure

This kind of text shows how one thing leads to another. The cause is why something happened, and the effect is what happened as a result. You might see this in science or history books. These books carefully link an action or event (the cause) with what changed or happened afterward (the effect). Spotting this structure helps you understand the reason behind different events and processes.

Problem- Solution Text Structure

Texts using the problem-solution structure talk about a problem, then suggest ways to solve it. You’ll see this a lot in work about social, political, or environmental problems. These texts discuss a problem and then suggest possible ways to fix it. Knowing this structure lets you think critically about the suggested solutions to different problems

Sequence Text Structure

The sequence structure puts information in a certain order, often the order things happened. This structure is used a lot in history books, biographies, how-to guides, or instructions. It gives readers a step-by-step rundown or timeline of events. Spotting this structure can help you follow the chain of events or steps accurately.

Description Text Structure

Texts with a description structure give lots of information about a topic, often using words that paint a picture for the reader. These texts can be about anything from scientific ideas to historical events. They dive into the details to give readers a full understanding of the subject. Knowing this structure helps you visualize and understand complex ideas.

Compare and Contrast Text Structure

This structure analyzes the similarities and differences between two or more topics. It’s used to provide nuanced perspectives on multiple subjects. Non-fiction authors often use this structure to compare different theories, concepts, events, or entities. Understanding this structure can help you see different perspectives and make informed comparisons.

How to Analyze the Structure of Non-Fiction Texts

Now that you’ve learned about the different types of text structures, it’s important to understand how to determine the structure of a particular text. Analyzing the structure of non-fiction texts involves a few important steps.

Step 1 : Begin with an open mind and read through the text. Try to understand the big picture without focusing too much on little details.

Step 2 : Pay attention to how the author shares information. Are events told in the order they happened? Does the author talk about a problem and then suggest a solution? Or maybe the text gives a lot of information about one subject? Spotting these patterns will help you figure out the text’s structure.

Step 3: Try to think about why the author picked this structure. How does it help get the main ideas and themes across? How does it change how you understand the text as a reader?

Step 4: Link the text structure to the author’s goal or point of view. Ask yourself, “How does this structure support what the author is trying to say or do?”

By following these steps, you’ll get a deeper understanding of the text, which will help you understand what you’re reading and think critically about it. If you do this often, you’ll become a stronger, more analytical reader.

How Text Structure Contributes to the Author’s Purpose

A non-fiction author’s purpose or point of view can shape their text structures. For instance, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” is a complex piece of non-fiction writing that integrates various text structures, as it addresses different aspects of the civil rights struggle. King’s purpose is shaped by the use of two primary text structures: problem-solution and cause and effect.

- Problem-Solution: Throughout the letter, King identifies various problems related to racial injustice and segregation. For instance, he discusses the problem of unjust laws and racial discrimination. He then proposes nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience as solutions to these problems.

- Cause and Effect: King also uses the cause and effect structure to demonstrate the relationship between racial discrimination (cause) and the resulting civil unrest and protest (effect). He explains how systemic oppression leads to nonviolent resistance and protests, emphasizing that these actions are the effects of ongoing racial prejudice and inequality.

Understanding the structure of non-fiction texts allows you to appreciate these nuances and gain a more profound insight into the author’s message. Just like each author’s personal background and purpose shape a novel, these factors influence the structure and presentation of non-fiction works, making each one a unique contribution to our collective knowledge.

Text Structure Practice: Analyzing George Bush’s 9/11 Speech

Let’s use what we know about text structures to look at George W. Bush’s speech after the 9/11 attacks.

Read through the speech carefully. While you read, underline or mark important points and transitions.

Think about possible text structures. Think about whether ‘Cause and Effect’ or ‘Chronological’ structures might apply. In ‘Cause and Effect’, we would expect the text to talk about a cause (like the terrorist attacks) and then focus on what happened because of it. In a ‘Chronological’ structure, the speech would mostly be organized by time. However, while there are pieces of these structures, the speech doesn’t mainly follow them.

Confirm the text structure. Based on what you’ve looked at, figure out the main text structure. In this case, the speech’s focus on a problem (the attacks) and the suggested solution (actions for safety and unity) fits the ‘Problem and Solution’ structure.

Spot the ‘Problem’. In Bush’s speech, this is the 9/11 attacks. Pay attention to how he talks about the events and how they’ve affected the country. For example, the quote “Today, our fellow citizens, our way of life, our very freedom came under attack in a series of deliberate and deadly terrorist acts.” identifies the problem.

Look for the ‘Solution’. Bush talks about this when he shares the steps being taken for the country’s safety and his call for unity and strength. A good example of this is in the line: “We go forward to defend freedom and all that is good and just in our world.” This is where Bush is discussing bringing the country together, promoting unity, and encouraging strength.

By following these steps, you can dissect the ‘Problem and Solution’ structure of Bush’s speech. This approach will help you understand the speech’s purpose, see how it was designed to reassure a shocked nation, and grasp how the speaker encouraged unity and resilience in a time of crisis. Applying these steps to other non-fiction texts will enhance your comprehension and analytical skills, revealing deeper layers of understanding.

In this digital age, understanding how to analyze and comprehend non-fiction text structures is a crucial skill for students. By recognizing and understanding structures like Cause and Effect, Problem- Solution, Sequence, Description, and Compare and Contrast, you can unlock a deeper understanding of the texts you encounter.

Whether it’s a novel by a renowned author, an informative article, or a powerful speech like George W. Bush’s 9/11 address, recognizing these structures will empower you to grasp an author’s purpose, viewpoint, and strategy more fully.

Practice Makes Perfect

By analyzing non-fiction texts, you not only develop your reading comprehension skills but also gain a deeper understanding of the underlying ideas and themes. However, just like any skill, effective analysis of text structure requires regular practice.

Here at Albert, we offer engaging and comprehensive resources to help you perfect this skill. Our practice questions and reading exercises are specifically designed to hone your understanding of different non-fiction text structures.

For more practice with this essential skill, check out our Text Structure Practice Questions in our Short Readings course , designed to provide thorough, step-by-step practice. Readers at all ability levels may enjoy our Leveled Readings course, which offers Lexile® leveled passages focused on a unifying essential question that keeps all students on the same page regardless of reading level. Learn more about the Lexile Framework here !

So, keep practicing, keep breaking down texts, and keep working on this important skill. Remember, every new text you read is a chance to get even better at analyzing.

Interested in a school license?

Popular posts.

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write a Thesis

I. What is a Thesis?

The thesis (pronounced thee -seez), also known as a thesis statement, is the sentence that introduces the main argument or point of view of a composition (formal essay, nonfiction piece, or narrative). It is the main claim that the author is making about that topic and serves to summarize and introduce that writing that will be discussed throughout the entire piece. For this reason, the thesis is typically found within the first introduction paragraph.

II. Examples of Theses

Here are a few examples of theses which may be found in the introductions of a variety of essays :

In “The Mending Wall,” Robert Frost uses imagery, metaphor, and dialogue to argue against the use of fences between neighbors.

In this example, the thesis introduces the main subject (Frost’s poem “The Mending Wall”), aspects of the subject which will be examined (imagery, metaphor, and dialogue) and the writer’s argument (fences should not be used).

While Facebook connects some, overall, the social networking site is negative in that it isolates users, causes jealousy, and becomes an addiction.

This thesis introduces an argumentative essay which argues against the use of Facebook due to three of its negative effects.

During the college application process, I discovered my willingness to work hard to achieve my dreams and just what those dreams were.

In this more personal example, the thesis statement introduces a narrative essay which will focus on personal development in realizing one’s goals and how to achieve them.

III. The Importance of Using a Thesis

Theses are absolutely necessary components in essays because they introduce what an essay will be about. Without a thesis, the essay lacks clear organization and direction. Theses allow writers to organize their ideas by clearly stating them, and they allow readers to be aware from the beginning of a composition’s subject, argument, and course. Thesis statements must precisely express an argument within the introductory paragraph of the piece in order to guide the reader from the very beginning.

IV. Examples of Theses in Literature

For examples of theses in literature, consider these thesis statements from essays about topics in literature:

In William Shakespeare’s “ Sonnet 46,” both physicality and emotion together form powerful romantic love.

This thesis statement clearly states the work and its author as well as the main argument: physicality and emotion create romantic love.

In The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne symbolically shows Hester Prynne’s developing identity through the use of the letter A: she moves from adulteress to able community member to angel.

In this example, the work and author are introduced as well as the main argument and supporting points: Prynne’s identity is shown through the letter A in three ways: adulteress, able community member, and angel.

John Keats’ poem “To Autumn” utilizes rhythm, rhyme, and imagery to examine autumn’s simultaneous birth and decay.

This thesis statement introduces the poem and its author along with an argument about the nature of autumn. This argument will be supported by an examination of rhythm, rhyme, and imagery.

V. Examples of Theses in Pop Culture

Sometimes, pop culture attempts to make arguments similar to those of research papers and essays. Here are a few examples of theses in pop culture:

America’s food industry is making a killing and it’s making us sick, but you have the power to turn the tables.

The documentary Food Inc. examines this thesis with evidence throughout the film including video evidence, interviews with experts, and scientific research.

Orca whales should not be kept in captivity, as it is psychologically traumatizing and has caused them to kill their own trainers.

Blackfish uses footage, interviews, and history to argue for the thesis that orca whales should not be held in captivity.

VI. Related Terms

Just as a thesis is introduced in the beginning of a composition, the hypothesis is considered a starting point as well. Whereas a thesis introduces the main point of an essay, the hypothesis introduces a proposed explanation which is being investigated through scientific or mathematical research. Thesis statements present arguments based on evidence which is presented throughout the paper, whereas hypotheses are being tested by scientists and mathematicians who may disprove or prove them through experimentation. Here is an example of a hypothesis versus a thesis:

Hypothesis:

Students skip school more often as summer vacation approaches.

This hypothesis could be tested by examining attendance records and interviewing students. It may or may not be true.

Students skip school due to sickness, boredom with classes, and the urge to rebel.

This thesis presents an argument which will be examined and supported in the paper with detailed evidence and research.

Introduction

A paper’s introduction is its first paragraph which is used to introduce the paper’s main aim and points used to support that aim throughout the paper. The thesis statement is the most important part of the introduction which states all of this information in one concise statement. Typically, introduction paragraphs require a thesis statement which ties together the entire introduction and introduces the rest of the paper.

VII. Conclusion

Theses are necessary components of well-organized and convincing essays, nonfiction pieces, narratives , and documentaries. They allow writers to organize and support arguments to be developed throughout a composition, and they allow readers to understand from the beginning what the aim of the composition is.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

How to Find the Main Idea in a Nonfiction Book

To be a machine: adventures among cyborgs, utopians, hackers, and the futurists solving the modest problem of death, in non-fiction books, especially the well-written ones, authors have a main idea and secondary ideas that support it. to understand the text, you need to identify and understand the main idea., additionally, think of the main idea as the author's message. but how does a reader find what the message is for a while now, i've been writing about inspecting or previewing a book before you read it. this will help you to identify the thesis of the book..

During the preview stage, it's important that you understand the author's main idea. Most times I find the main idea in the Introduction section of the book or in the first few paragraphs of the first chapter. However, I also get a sense of what the book is about when I'm reviewing the Table of Contents.

The Title and Subtitle and book description are usually helpful as well. But there are times when things aren’t that straightforward, so what do you do?

Have you read?

What You Need to Know About Effective Reading

How to Find the Main Idea in a Nonfiction Book: To Be a Machine as an Example

And here is the book description that I pulled from Amazon to give you more information and context. What do you think?

- In your opinion, what is the key message in the book?

- Do you have enough information to make a guess?

- What are some words that stand out for you?

I got the book because some key words stood out for me. And I also have some big questions. In the title, there is solving the modest problem of death, what does that mean? Can death be solved? Is this about extending life? Was he thinking about the bionic man?

When I read the book description, transhumanism popped out for me. And also the sentence about your body as a device stood out. I started to get an inkling of what the book was about. And I wanted to learn more.

“Transhumanism is a movement pushing the limits of our bodies—our capabilities, intelligence, and lifespans—in the hopes that, through technology, we can become something better than ourselves. It has found support among Silicon Valley billionaires and some of the world’s biggest businesses.” Amazon Book Description

Possible Main Idea of To Be a Machine

After inspecting the book, I concluded that the main idea of the book is to extend human life with the use of technology. More than likely I'll have to refine it, but this is a good place to start. It took me about 15 minutes to inspect the book. And I had to make do with the information I readily had access to.

The table of contents does not give you much to work with. You have two choices. You can choose to read the entire book. Or you can read the first and last paragraph of each chapter. The question for me is, “How serious am I about reading up on transhumanism?” And, “Will the book help me in any way?” For me, these are two very important questions.

How to Find the Main Idea in a Nonfiction Book: The Food Revolution Another Example

And here is the Table of Contents.

The main idea of The Food Revolution is that when you move away from high-fat, animal-based diet to a low-fat, plant-based diet, living a healthier lifestyle, you can heal your body and the world. Doing this helps you to create a more sustainable way of life. The two introductions gave you insights into how changing the way yo eat can heal the planet.

“I have written The Food Revolution to provide solid, reliable information for the struggle to achieve a world where the health of people and the Earth community is more important than the profit margins of any industry, where basic human needs take precedence over corporate greed. I have written this book so that you might have clear information on which to base your food choices. It will show you how to attain greater health and respond more deeply from your connection to all of life.” John Robbins.

How to Find the Main Idea in a Nonfiction Book: The Thing About Reading Books

As I learn more about effective reading, I realize that you often have to figure out things for yourself. As I illustrated above with To Be a Machine and The Food Revolution, you'll never have what you expect when you inspect a book. And that's the way it's with life. You have to make choices. And you have to work with what you have. It balances out in the end. You'll figure out what the main idea is of the book. It may take longer to do so, based on how much information you have.

It's important to invest the time to figure out the main idea of the nonfiction book that you plan to read. Think of the main idea as a skeleton. You add the content of the book to the skeleton. However, how much content you add to the skeleton will determine how lean or fat the final form will be. Not every piece of information in the book will add to your understanding of the text.

Having a purpose for reading the book, as well as understanding the main idea that the author is trying to communicate allows you to decide what's essential information. I'm building a tribe, Read a Book Solve a Problem , so I want to read as much of the book as I need to. And no more than that. This gives me the time I need to process more books.

Read a Book Solve a Problem: Join the Community Today!

Final Thoughts on How to Find the Main Idea in a Nonfiction Book

As mentioned above, it's important to understand what a book is about before you start reading it. The main idea helps you to do that. Sometimes it's much easier to determine the message the author is trying to communicate. Providing the two examples show how much time it will take. Don't skip this step though, even if it will take more effort on your part.

In summary, here are the steps to find the main idea in a nonfiction book:

- State your one-sentence purpose for reading the book. This is the first time I'm mentioning this in the post because I've said it enough times in other posts.

- Book Description

- Introduction

- Table of Contents

If the book doesn't have all of the above sections, then you have to get creative. It may mean reading the first and last paragraph of every chapter. Do what you need to find the main idea in a nonfiction book. This will aid your understanding of the text when you decide to explore more deeply.

How Avil Can Help You!

If you do not want to gamify your reading, I invite you to Join the Performance Accelerator Plan that walks you through the process of learning key skills and more. You’ll be reading books to build skills and develop intercultural awareness. Get more reading and learning tips here .

In December 2020, I published two books on Amazon. I would greatly appreciate your support if you bought my two short e-books Read 30 Books in 30 Days Like Francis Bacon and Performance Accelerator Plan: Guide to Learning and Mastering Key Skills for the Future .

Read 30 Books in 30 Days Like Francis Bacon is not about speed reading. It’s about approaching every book differently and reading only the sections that align with your purpose.

The Performance Accelerator Plan book is a stripped-down version of the paid reading challenge of the same name. Obviously, you won’t get all the resources that come with the program that I sell on my website . But if you are a self-directed learner, it will help you tremendously.

If someone clicks on a link and buy something from Amazon, the company will pay me a small commission.

About the Author Avil Beckford

Hello there! I am Avil Beckford, the founder of The Invisible Mentor. I am also a published author, writer, expert interviewer host of The One Problem Podcast and MoreReads Success Blueprint, a movement to help participants learn in-demand skills for future jobs. Sign-up for MoreReads: Blueprint to Change the World today! In the meantime, Please support me by buying my e-books Visit My Shop , and thank you for connecting with me on LinkedIn , Facebook , Twitter and Pinterest !

Enjoyed this article?

Find more great content here:

Act Now: Do You Act Quickly on Opportunities Or Take Your Time

Curate this: the hands-on, how-to guide to content curation by steven rosenbaum, organizing and prioritizing information from nonfiction books: a comprehensive guide.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Non Fiction Book Report: How to Write the Perfect Paper

The thought of a non fiction book report may bring to mind early school days. In fact, a parent could easily use this article to help their kids complete one of these report assignments. However, even college students may be asked to review or report on a nonfiction book. Thankfully, the standards for what makes a perfect analysis paper doesn’t change across grade levels. The content itself becomes more complicated but the principles stay the same.

There are two main principles to writing a perfect book report: describe and evaluate. Knowing how to perform each and how to balance them can help you, your students, or your kids write the best paper they can.

Describe: The Facts of the Non Fiction Book Report

Description in a book report includes names and major points in the book. This is not the time to state your analysis of the work but simply to list the relevant information so the reader knows where your analysis will go.

The information in the description portion of a nonfiction book report includes background on the author and relevant information on the creation of the book. State how the book has been assembled or organized, especially if it takes a unique genre form. This includes the author’s intention with the book as a thesis or a statement of purpose. Let the reader know that you have a big picture of the nonfiction book being discussed.

Finally, offer a summary of the nonfiction book to get your readers on the same “page” for your evaluation. By selectively summarizing information, the reader (or grader) knows what they should take from your analysis.

Evaluate: Make Your Points

When you begin evaluating, use the information you reviewed and summarized in the description section. Evaluation involves your opinion, but a supported opinion that includes relevant scholarship. This means that other writers’ reviews and journal articles that discuss the nonfiction book you’re studying can come in handy to back up your points.

You can observe the strengths and faults of the book based on your observations and experience. However, the more you can support your statements with the words of others and of the book itself, the better your report will be.

How to Start Writing a Book Report

As you read, you have to read the right way ! This means observing the author’s purpose quickly, learning the background information that will go into your report beforehand, and taking notes. As you read, note the author’s expertise and how they incorporate their thesis. When you see quotes that support the author’s ideas (or yours), take note of where they occur. This can only make writing the report easier in the long run.

The Takeaway

A non fiction book report sounds like a hefty obligation. However, whether it’s a college paper or a child’s school project, a book report doesn’t have to be a burden. Get the two qualities of description and evaluation clearly distinct in your head so that when you read, you can already sort and note the informtation that will make your paper work.

Like it? Share it!

Get Updates Right to Your Inbox

Further insights.

Privacy Overview

How to Research a Nonfiction Book: 5 Tips for Writers

That you’ve landed here tells me you have a message you want to share in a book.

You’re eager to start writing, but you first need to conduct some research.

Problem is, you’re not sure how to research for a nonfiction book .

You may even wonder whether research is all that important.

You may be an excellent writer, but even a small factual mistake can cost you the credibility of your readers.

Over the last half-century, I’ve written over 200 books, 21 of them New York Times bestsellers. So I ought to be able to write a book on my area of expertise — writing and publishing — based on my experience alone, right?

I wouldn’t dare write such a book without carefully researching every detail. Because if I get one fact wrong, my credibility goes out the window. And I’d have only my own laziness to blame.

Thorough research can set your book — your message — apart from the competition.

As you research, carefully determine:

- How much detail should go into your book

- Whether even if it’s interesting, is it relevant?

- To remain objective and not skew the results to favor your opinions

- To use research as seasoning rather than the main course (your message)

As you weave in your findings, always think reader-first. This is the golden rule of writing.

Your job is to communicate so compellingly that readers are captivated from the get-go. This is as important to how-to manuals and self-help books as it is to a memoir .

- 5 Tips for Researching Your Nonfiction Book

1. Start With an Outline

While the half or so population of novelists who call themselves Pantsers (like me), who write by the seat of their pants as a process of discovery, can get away without an outline, such is not true of nonfiction authors.

There is no substitute for an outline if you’re writing nonfiction .

Once you’ve determined what you’d like to say and to whom you want to say it, it’s time to start building your outline.

Not only do agents and acquisitions editors require this, but also you can’t draft a proposal without an outline.

Plus, an outline will keep you on track when the writing gets tough. Best of all, it can serve as your research guide to keep you focused on finding what you really need for your project.

That said, don’t become a slave to your outline. If in the process of writing you find you need the flexibility to add or subtract something from your manuscript, adjust your outline to accommodate it.

The key, again, is reader-first, and that means the best final product you can create .

Read my blog post How to Outline a Nonfiction Book in 5 Steps for a more in depth look at the outlining process.

2. Employ a Story Structure

Yes, even for nonfiction, and not only for memoirs or biographies.

I recommend the novel structure below for fiction, but — believe it or not — with only slight adaptations, roughly the same structure can turn mediocre nonfiction to something special.

While in a novel (and in biographical nonfiction), the main character experiences all these steps, they can also apply to self-help and how-to books.

Just be sure to sequence your points and evidence to promise a significant payoff, then be sure to deliver.

You or your subject becomes the main character in a memoir or a biography. Craft a sequence of life events the way a novelist would, and your true story can read like fiction.

Even a straightforward how-to or self-help book can follow this structure as you make promises early, triggering readers to anticipate fresh ideas, secrets, inside information — things you pay off in the end.

While you may not have as much action or dialogue or character development as your novelist counterpart, your crises and tension can come from showing where people have failed before and how you’re going to ensure your readers will succeed.

You might even make a how-to project look impossible until you pay off that setup with your unique solution.

Once you’ve mapped out your story structure, determine:

- What parts of my book need more evidence?

- Would another point of view lend credibility?

- What experts do I need to interview?

3. Research Your Genre

I say often that writers are readers.

Good writers are good readers.

Great writers are great readers.

Learn the conventions and expectations of your genre by reading as many books as you can get your hands on. That means dozens and dozens to learn what works, what doesn’t, and how to make your nonfiction book the best it can be.

4. Use the Right Research Tools

Don’t limit yourself to a single research source. Instead, consult a range of sources.

For a memoir or biography, brush up on the geography and time period of where your story took place. Don’t depend on your memory alone, because if you get a detail wrong, some readers are sure to know.

So, what sources?

There’s no substitute for an in-person interview with an expert. People love to talk about their work, and about themselves.

How do you land an appointment with an expert? Just ask. You’d be surprised how accessible and helpful most people are.

Be respectful of their time, and of course, promise to credit them on your Acknowledgments page.

Before you meet, learn as much as you can about them online so you don’t waste their time asking questions you could’ve easily answered another way.

Ask deep, fresh, personal questions unique to your subject. Plan ahead, but also allow the conversation to unfold naturally as you listen and respond with additional questions.

Most importantly, record every interview and transcribe it — or have it transcribed — for easy reference as you write.

World Almanacs

Online versions save you time and include just about anything you would need: facts, data, government information, and more. Some are free, some require a subscription. Try the free version first to be sure you’ll benefit from this source.

On WorldAtlas.com , you’ll find nearly limitless information about any continent, country, region, city, town, or village.

Names, time zones, monetary units, weather patterns, tourism info, data on natural resources, and even facts you wouldn’t have thought to search for.

I get ideas when I’m digging here, for both my novels and my nonfiction books.

Encyclopedias

If you don’t own a set, you can access one at a library or online . Encyclopedia Britannica has just about anything you’d need.

Here, you can learn a ton about people, places, addictions, hobbies, neuroses — you name it. (Just be careful to avoid getting drawn into clickbait videos.)

Search Engines

Google, Bing, DuckDuckGo, and the like have become the most powerful book research tools of all — the internet has revolutionized my research.

Type in any number of research terms and you’ll find literally (and I don’t say that lightly) millions of resources.

That gives you plenty of opportunity to confirm and corroborate anything you find by comparing it to at least 2 or 3 additional sources.

The Merriam Webster online thesaurus is great, because it’s lightning fast. You couldn’t turn the pages of a hard copy as quickly as you can get where you need to onscreen.

One caution: Never let it be obvious you’ve consulted a thesaurus. Too many writers use them to search for an exotic word to spice up their prose.

Don’t. Rather, look for that normal word that was on the tip of your tongue. Just say what you need to say.

Use powerful nouns and verbs, not fancy adjectives and adverbs.

Wolfram Alpha

View this website as the genius librarian who can immediately answer almost any question.

Google Scholar

This website offers high quality, in depth academic information that far exceeds any regular search engine.

Library of Congress

A rich source of American history that allows you to view photos, other media, and ask a librarian for help if necessary.

Your Local Library

The convenience of the internet has caused too many to abandon their local library. But that’s a mistake. Many local libraries offer all sorts of hands-on tools to enhance your research effort.

Evaluating your sources

When researching your nonfiction book, be aware that not all sources are equal, especially online.

Bias and misinformation run rampant, making it hard to distinguish between fact and misinformation.

Simply Googling your topic can lead to an array of conflicting sources with varying messages.

Be judicious by comparing with other sources what you’ve gleaned so you can determine the most prevalent and plausible result.

Primary vs. secondary sources

First-hand accounts from witnesses to or participants in an event or with full knowledge of an area of discipline are ideal. Live or online interviews, autobiographies, diaries, original documents, data reports, video/photographs/audio, etc., are best as primary sources

Secondary sources are comprised of interpretations of, commentary on, or conjecture related to primary sources. Examples: books, analysis of data, scholarly articles, and documentaries.

Source Evaluation Checklist

1. How new is the information?

Relevancy is important.

If your research results in contradictory information because some sources are old, it might make sense to cite both the old and the new in your book to show how things have evolved. But also be careful not to assume the latest information is more reliable. If it’s merely trendy, it might soon become obsolete.

2. Who’s the intended audience?

Consider the intended audience of the source itself.

Is the material meant to educate? Entertain? Is it an overview or is it someone’s thesis?

3. Is the source really an expert?

What do their reputation and credentials say about them? How long have they studied their discipline? Do other experts back their views?

4. Can you verify the source?

Trustworthy sources don’t exist in vacuums.

Do your due diligence to be sure your source is generally accepted and trusted. Are they associated with a well-known institution or are they board-certified in their area of expertise? Are they quoted by fellow experts?

5. Who published the source?

Take into consideration any bias on the part of the source that may affect their trustworthiness.

In the 1950s, before it was widely accepted that smoking was harmful, tobacco companies funded research to counter mounting scientific evidence that cigarettes were linked to serious health problems.

So look beyond the author of your source and investigate who funded and published it.

The bias may not be as obvious as misrepresenting the health effects of tobacco, but it will affect the credibility of the information.

5. Avoid Procrastination: Set a Deadline

At first glance, researching for your nonfiction book may sound like homework, but it can be fun. So fun it can be addicting — the more we learn, the more we tend to want to know.

Many writers use research as an excuse to procrastinate from writing.

To avoid this, set a firm deadline for your research, and get to your writing. If you need further research, you can always take a break and conduct it.

- Time to Get Started

There’s no substitute for meticulous research and the richness it lends to your nonfiction writing. The trust it builds with readers alone is worth the effort.

Start with your outline, and before you know it, you’ll be immersed in research and ready to begin writing.

I can’t wait to see what you come up with!

Are You Making This #1 Amateur Writing Mistake?

Faith-Based Words and Phrases

What You and I Can Learn From Patricia Raybon

Before you go, be sure to grab my FREE guide:

How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps

Just tell me where to send it:

- Why Wonderwell

- Author Testimonials

- The Big Leap Book-Planning Program & VIP Retreat

- Hybrid Publishing

- Assisted Self-Publishing

- Big Ideas Blog

- Submissions

A Nonfiction Author’s Guide to Citation Notes and Bibliographies

by Maggie Langrick Sep 14, 2020 Author Resources

Planning to refer to studies, articles, books, websites, or other published works in your book? You’ll need to provide full bibliographic information for each of your references. Compiling this material can feel like a chore when your attention is focused on completing your manuscript, but it’s a good idea to make it a regular part of your writing practice. By keeping accurate, comprehensive notes while you write, you’ll save yourself stress and aggravation when it comes time to format your citation notes and bibliography.

Why cite your sources?

The reason your readers have picked up your book is to learn about the subject matter, and by sharing your sources, you direct them as to where you learned a fact, quote, or idea, and enable them to find out more context about that fact, quote, or idea.

Citations also give your work authority. It’s necessary to check the accuracy of the cited material and the suitability of how you’re using it to prove your argument/illustrate your ideas—not to mention you have a moral imperative to credit your sources.

What sources do you cite?

- All direct quotations*

- All tables, graphs, illustrations reproduced from another’s work

- All facts and statistics (and sometimes conclusions) obtained from another’s work

- You may decide to cite beyond the three categories listed above depending on the audience or the conventions of a certain subject area

*You must cite or provide in-line attribution (ie. explicit acknowledgement of the source of a quote or fact in the text) for all direct quotations. In-line attribution is a very common and acceptable form of citation, particularly for famous quotations. If you plan to repurpose longer passages of a previously published work, you may need to request permission from the copyright holder .

Widely known and easily verified facts do not need to be cited, nor do proverbs, idioms, and jokes (unless the joke is part of a comedian’s act).

How do you cite your sources?

One common approach is to put all references in a “Notes” section at the back of the book (called endnotes)—this is ideal if there are many notes per chapter. Another option is to put references that appear on a specific page at the bottom of that page (known as footnotes).

Examples of citation notes follow below. They include the same information as the entries in the bibliography (see below), but in a different format and with one additional, crucial piece of information for printed works: a page number or page range, which points readers to where exactly within the source material they can find the specific information being cited.

John Schwartz, Bicycle Days (New York: Summit Books, 1989), p.7.

Walter Blair, “Americanized Comic Braggarts,” Critical Inquiry 4, no. 2 (1977).

[article online]

Tanya Basu, “Why More Girls—and Women—Than Ever Are Now Being Diagnosed with ADHD,” New York, January 20, 2016, http://nymag.com/scienceofus/2016/01/why-more-girls-are-being-diagnosed-with-adhd.html. Accessed April 10, 2017.

[blog entry]

Rhian Ellis and Ed Skoog. Ward Six (blog). http//wardsix.blogspot.com/.

[online encyclopedia]

Wikipedia , s.v. “Bullying,” last modified April 14, 2016, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bullying.

[online dictionary]

Merriam-Webster Online , s.v. “romanticism,” https://merriam-webster.com/dictionary/romanticism.

[online media]

Trisha Prabhu, “Rethink before You Type,” TEDxTeen, October 2014, video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YkzwHuf6C2U.

What information goes into an entry in the bibliography?

When the source material is a book , gather and record:

- Author of book

- Title and subtitle

- Secondary responsibility people (editor, translator, illustrator, etc.)

- Edition (if it’s the first edition, don’t mention it)

Most of your book entries will look like this:

Jones, Edward P. The Known World. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 2003.

If there is more than one author, invert the first author’s name only, e.g. Glazer, Brian, and Charles Fishman.

When the source material is an article , gather and record:

- Author of part

- Title of part

- Title of serial

- Sponsoring body

- Issue designation (e.g., volume, season, year)

- Location of part within serial issue

Your article entries will look like this:

Kingston, Anne, “Could the Queen of Green be Mean?” Maclean’s. 29 October 2007, p. 22.

Frechette, Louis. “Canada and the 1995 G7 Halifax Summit.” Canadian Foreign Policy. Norman Paterson School of International Affairs, Carleton University. Vol. 3, no. 1 (Spring 1995), pp. 1–4.

What is the difference between notes and a bibliography? Why is it important to include both?

A note documents a specific quotation of text or the paraphrasing of ideas from a source. It is depicted with the use of a superscript number in the text and includes a page reference so that readers may find the exact location of the cited material in the source.

A bibliography is a list of all the sources you either cited from or consulted during the research for your book. It presents a far more rounded picture of the research you have done. A good bibliography should contain the sources that you consulted but did not necessarily cite from during your research (though this, too, can be selective—you don’t have to list everything, just the ones that informed your research). It may also include books that are relevant to the subject matter of your book and that you think the reader should know about—or these can be included as a list called “recommended reading,” which would come after the bibliography.

Many readers find it easier to locate a source in the bibliography. They may not remember where the note appeared in the book, but they may remember the author or the title of the book if it is mentioned in the text.

For each note, there should be a corresponding entry in the bibliography. Bibliographic entries are listed alphabetically by author name and do not include page references.

Now that you understand the necessity of citation notes and bibliographies, you can get into the practice of tracking your sources as you do your research. Proper formatting isn’t important at this point; your citation notes and bibliography can always be cleaned up during the copy editing stage. But by capturing this information early on, you’ll be doing yourself—and your editor—a big favor.

To receive more writing, marketing, and publishing advice, sign up to our mailing list here .

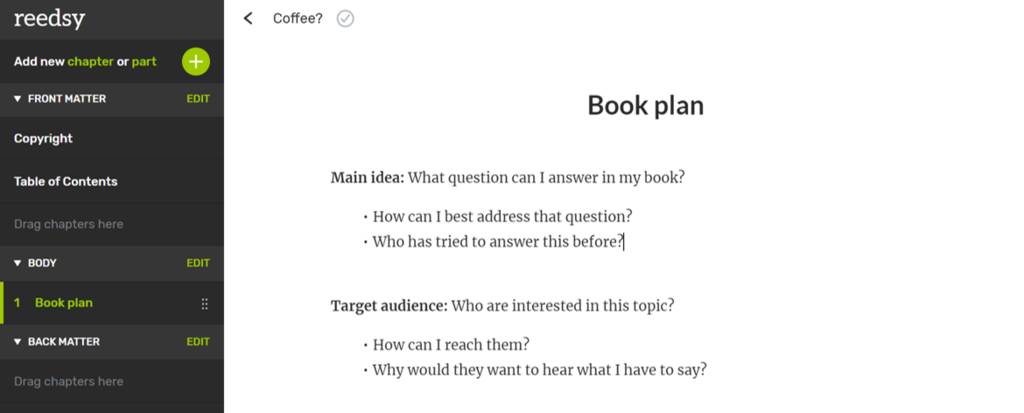

All the building blocks of your nonfiction book in one handy reference guide.

Are you writing your book without a Book Plan in place? If so, do yourself a favor and download our Book Plan Template before writing another word! It will guide you through capturing and organizing the 8 critical elements of any nonfiction book. Just subscribe here, and we'll send you the download link.

Head over to your inbox to confirm signup, and you're in.

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from Wonderwell, 811 Wilshire Blvd. 17th Floor, Los Angeles, CA, 90017. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the "unsubscribe" link found at the bottom of each email.

Here's what I learned TOTALLY by accident. Personal story sells.

How to write a (prescriptive) non-fiction book introduction.

September 18, 2023

The introduction to your non-fiction book is your chance to make a good impression on potential readers and convince them to keep reading. We’re all busy people, so we need to know, straight out of the gate, that our precious time will not be wasted.

These first few pages are where you’ll introduce your topic, explain why it’s important, and give readers a preview of what they’ll learn in the rest of the book.

Here are some key things to include in your introduction:

Grab the reader’s attention . The first few sentences of your introduction should be strong and engaging, so that readers want to keep reading. You can do this by telling a story (my favorite method), asking a question, or sharing a surprising fact. For instance: According to a study by Author Marketing Club, only 3% of people who start writing a book actually finish it. (Bet that got you to sit up!)

Introduce your topic . What is your book about? Managing anxiety in the workplace? Starting a business with $100? Saving your child from addiction? Why is the topic important? What new knowledge or insights will readers gain from reading it?

Give us a clear problem the reader will fess up to : We need a clear problem that is being addressed and solved. What does it feel like for a person to have this problem in a very visceral way? How is this problem not about personal failings, but a societal issue? How can we make it OK for our reader to fess up to having this problem so they can address it, not pretend they don’t have it? What kind of social proof can you offer? Statistics, a reference to other experts, scientific studies that expand on this. So we know that this is a common issue.

Give us an enemy or a myth that must be debunked : What is the mistaken thinking that has gotten the reader into hot water? What do they believe needs to be turned around so they can fix the problem? What do they, wrongly, think is the solution?

Offer us your thesis statement . A thesis statement is a concise statement that expresses the main argument or claim of your book. A good thesis statement is clear, concise, and arguable, meaning that it should be a statement that people could disagree with. It should also be supported by the evidence presented in the book.

Here are some examples of good (arguable) thesis statements for non-fiction books:

- Children should have an equal say in all family decisions to reduce their need to act out.

- You will save yourself years if you commit to writing a first shitty draft instead of trying to write the perfect book in one go.

- Climate change is a real and urgent threat to our planet, and it is caused by animal product consumption.

- Yo-yo dieters are food addicts.

Establish your credibility . Why are you the right person to write this book? What expertise or experience do you have on the topic? If you have both personal and professional experience, all the better. If you were your own first client, then used your methodology to help hundreds of other people to overcome the problem that you address, well, we want to know about this right here. Why are you the person who not only gets it, but has the solution, has fought to figure out a solution? Have you developed a system to fix this problem? How did it come about?

Outline the structure of your book. Is the book comprised of short readable chapters? Is it divided into three main sections? Does each chapter contain exercises that the reader can do along the way? What will readers learn in each chapter?

Clarify the outcome . What are the main takeaways from the book? By the time they finish reading this book, how will the reader’s life be different? How will their life improve physically, finically, emotionally, and spiritually?

To help you organize your thoughts so you can dive into your first draft, here are a few questions to consider:

- Who are you (the author) and why are you the person who not only gets it, but has the solution, has fought to figure out a solution?

- What does it feel like for a person to have this problem in a very visceral way? How is this problem not about personal failings, but a societal issue? How can we make it OK for our reader to fess up to having this problem so they can address it, not pretend they don’t have it?

- What kind of social proof can you offer? Statistics, a reference to other experts, scientific studies that expand on this. So we know that this is a common issue.

- What is the mistaken thinking that has got the reader into hot water? What do they believe that needs to be turned around so they can fix the problem? What do they, wrongly, think is the solution?

- Have you developed a system to fix this problem? How did it come about?

- What are you going to teach them?

- What polarizing statement do you mean to support with your book? What will other experts in your field likely disagree with?

- By the time they finish reading this book, how will the reader’s life be different? How will their life improve physically, finically, emotionally, and spiritually?

[…] Restate your thesis or main message: Begin your conclusion by revisiting the main point or argument you made in your introduction. This reminds your readers of the central focus of your piece. (If you don’t know what I’m referring to, go HERE.) […]

Subscribe to my newsletter

Subscribe to my newsletter. Want to know my deal? Well, these are some of my stories. This is my take on life, writing, and reading.

Check out my book

Straight-talking, funny and brutally honest, How To Eat The Elephant will give you--yes, you--the push you need to haul your ass off the sofa and position it in front of your computer long enough to produce a real, live book.

The Influential Author Formula

If you’d like to clarify your message and be seen as an expert in your field so you can make some hardcore sexy cash before the onset of the next ice age, you’re in the right place.

check it out

Three narrative-driven nonfiction genres

© 2024 Ann Sheybani. design by Joana Galvão | Terms and conditions

- Work with me

- Translate Page

Scroll to find the Learn to and Resources boxes

Nonfiction Books

Nonfiction books are based on facts and cover virtually any topic. For research purposes, you will probably be looking for books that synthesize all the information on one topic to support a particular argument or thesis. Nonfiction books are often designed to be read cover to cover and even "enjoyed," although you may only need to use one portion for your research. While reference books and encyclopedias are also nonfiction, they are designed for the user to read sections as needed, and they often present information in a straight scholarly manner.

When do I use a nonfiction book? Use nonfiction books when you need the following:

- to find lots of information on a topic

- to put your topic in context with other important issues

- to find historical information

- to find summaries of research to support an argument

Where do I find a nonfiction book? They can be found in print, online, or in a periodicals database. Many are available at your local school or public library. Libraries organize and store their book collections on shelves called "stacks." Use an online catalog to find the call number. Most public and school libraries use the Dewey Decimal system to organize their books while most college libraries use the Library of Congress system.

How is a nonfiction book organized? Nonfiction books have a title page, verso (back of the title page that has publication information), table of contents, chapters that divide the book's content into sections (topics, time periods, etc.), notes, bibliography (sources the author used), and an index.

How do I use a print nonfiction book? They typically have a table of contents near the front of the book. This can give you a good overview of how the book is arranged and what is covered. Think about what information you need. Typically the last several pages of a nonfiction book contain the index. This is an alphabetical listing of the topics in the books, and on what pages they can be found. There may be more than one index, e.g. subject index, geographical index, personal name index. Use the index to locate the section or pages you need.

How do I use an online nonfiction book (eBook)? Online nonfiction books may be exact replicas of the equivalent print book, while some are published exclusively online. Online nonfiction books often have a searchable index, or a typical index that links automatically to the page indicated. They are also either usually searchable by keyword and sometimes subject.

How do I use a database to find a nonfiction book (eBook)? Searching a database by topic will result in sources from magazines, journals, newspapers, eBooks, and more. Most databases' advanced search feature allows your search to be limited by the type of source you are looking for. You can also limit your source by date or title of publication.

- Accessibility

- Powered by Plone & Python

login (staff only)

Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing group!

Nonfiction Writing Checklist for Your Book

by Fija Callaghan

Taking the plunge into nonfiction writing? Writing true-to-life stories from the heart can be incredibly rewarding, whether it’s a 1000-word blog post or a 100,000-word memoir. Or maybe you’re beginning your journey into traditional nonfiction, in which you help the reader learn something new.

Regardless of what message you’re trying to send, there are a few things you’ll need to have in place so that your core focus and main idea comes across in the most compelling way possible. Let’s dive in.

Why write nonfiction?

First of all, why leap into writing nonfiction? If you’re a born storyteller, moving from fiction to nonfiction might seem uninspired or dull.

Not so, writerly friends. Writing nonfiction books can be a great way to communicate big ideas with a wide range of readers. No longer limited to technical manuals and history texts, nonfiction writing encompasses a variety of powerful mediums through which to educate, incite, and inspire.

Plus, nonfiction can help you process your own feelings and experiences, too. Some writers turn to nonfiction, such as memoirs or personal essays, to address trauma and understand complex relationships. The great thing about these is that while they’re helping you heal, learn, and grow, they’re helping your readers heal, learn, and grow too.

Traditional nonfiction vs. creative nonfiction

When we talk about nonfiction, we generally mean one of two distinct subgenres: traditional nonfiction and creative—or narrative—nonfiction.

Traditional nonfiction is rooted in fact. These are usually designed to teach the reader something new. Most “How To” books fall under traditional nonfiction, as do scholarly and academic writings.

Creative nonfiction—sometimes called narrative nonfiction or literary nonfiction—is a personal piece of writing that tells a story. This might be a story of the writer’s entire life, or it may be an article, blog post, or essay that talks about one particular experience.

More and more, the line between traditional and creative nonfiction is becoming blurred. When contemporary readers turn to traditional nonfiction texts, they often expect the information to be held together by personal experiences. This is a good thing to keep in mind in your own work—readers will absorb key ideas better if they’re able to connect to the humanity behind the words.

You can learn more about the difference between creative and traditional nonfiction in our dedicated lesson here .

The ultimate checklist for nonfiction writing

Ready to begin your nonfiction project? Here are some tips to keep in mind during the writing process to make your work the very best it can be.

Before writing your nonfiction book

Nail down your core idea. Many nonfiction books, essays, and articles fail because they meander away from what they’re really trying to say. Before you begin writing, look at your central theme, argument, perspective, or idea that you want your reader to come away with. Knowing this from the beginning helps keep your piece of writing strong and focused.

Consider your target audience. Who are you writing for? A research paper meant for graduate students will likely read differently than a blog post for a layperson just learning about your niche. Is your nonfiction work going to be read by people who are already familiar with industry jargon, or are they discovering something new for the first time? Try to come up with a clear idea of who will be reading your work.

Write a chapter outline. If you’re writing a longer form nonfiction manuscript, you’ll find designing an outline of all your chapters before beginning your first draft incredibly helpful. This gives you a “bird’s eye view” of your entire book so you can see each of the important points and ideas you’re planning to explore. When you create an outline, you’ll have a clear road map of your writing process.

You can check out our full guide on creating a nonfiction outline here !

Research obsessively. No matter what you’re writing, you’ll need it to be backed by supporting research. This is as true in a memoir as it is in a history text—your story will be more powerful if you have clear dates, locations, and references to all the people you’re writing about. Remember, readers are turning to you to understand something they didn’t understand before. Make sure you have a broad, well-researched base of knowledge to draw from in your work.

While writing your nonfiction book

Set manageable goals. It’s easy to get overwhelmed starting a new project. Try organising your time into manageable bites so you don’t get discouraged. For a nonfiction book, this might be something like 500 words per day or one chapter every two weeks. If it’s something like an article or personal essay, break it down into simple steps: introduction, body paragraphs, conclusion, at a pace that works for you.

Make notes for supplementary research. Even though you’ve already done a lot of research on this project, you’ll inevitably run into things you’re not sure of as you go. Instead of stopping to check every few hours—thereby disrupting your precious creative flow—keep notes on things you need to verify later. You can use notes on the page like “FTT” ( fact check this ), or keep a running list of details to look into at the end. This helps keep you organised while maintaining your forward motion.

Close each chapter with a call to action. In a shorter form piece, you’ll do this just once at the very end. A call to action is a suggestion to the reader to absorb what you have taught them and incorporate it into their own life. Sometimes, you might do this directly by making suggestions at the end of a section; other times it might be subtler, implied through the emotions you’ve raised and the ideas you’ve presented. Every time you end a chapter or article, think about what you want your audience to do once they put down your book.

After writing your nonfiction book