A brief history of globalization

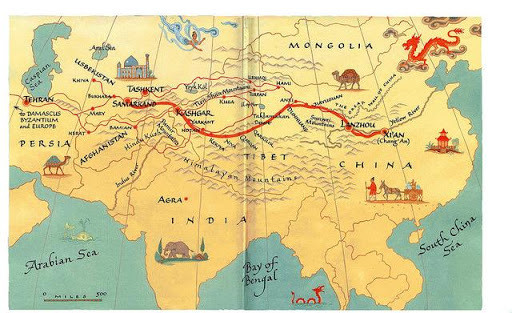

Past and present: A Silk Road-inspired installation outside the National Convention Centre in Beijing Image: REUTERS/Stringer

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Peter Vanham

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} United States is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, united states.

When Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba in 2018 announced it had chosen the ancient city of Xi’an as the site for its new regional headquarters, the symbolic value wasn’t lost on the company: it had brought globalization to its ancient birthplace, the start of the old Silk Road. It named its new offices aptly: “ Silk Road Headquarters ”. The city where globalization had started more than 2,000 years ago would also have a stake in globalization’s future.

Alibaba shouldn’t be alone in looking back. As we are entering a new, digital-driven era of globalization – we call it “Globalization 4.0” – it is worthwhile that we do the same. When did globalization start? What were its major phases? And where is it headed tomorrow?

This piece also caps our series on globalization. The series was written ahead of the 2019 Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, which focuses on “Globalization 4.0”. In previous pieces, we looked at some winners and losers of economic globalization, the environmental aspect of globalization, cultural globalization and digital globalization . Now we look back at its history. So, when did international trade start and how did it lead to globalization?

Silk roads (1st century BC-5th century AD, and 13th-14th centuries AD)

People have been trading goods for almost as long as they’ve been around. But as of the 1st century BC , a remarkable phenomenon occurred. For the first time in history, luxury products from China started to appear on the other edge of the Eurasian continent – in Rome. They got there after being hauled for thousands of miles along the Silk Road. Trade had stopped being a local or regional affair and started to become global.

That is not to say globalization had started in earnest. Silk was mostly a luxury good, and so were the spices that were added to the intercontinental trade between Asia and Europe. As a percentage of the total economy, the value of these exports was tiny, and many middlemen were involved to get the goods to their destination. But global trade links were established, and for those involved, it was a goldmine. From purchase price to final sales price, the multiple went in the dozens.The Silk Road could prosper in part because two great empires dominated much of the route. If trade was interrupted, it was most often because of blockades by local enemies of Rome or China. If the Silk Road eventually closed, as it did after several centuries, the fall of the empires had everything to do with it. And when it reopened in Marco Polo’s late medieval time, it was because the rise of a new hegemonic empire: the Mongols. It is a pattern we’ll see throughout the history of trade: it thrives when nations protect it, it falls when they don’t.

Spice routes (7th-15th centuries)

The next chapter in trade happened thanks to Islamic merchants. As the new religion spread in all directions from its Arabian heartland in the 7th century, so did trade. The founder of Islam, the prophet Mohammed, was famously a merchant, as was his wife Khadija. Trade was thus in the DNA of the new religion and its followers, and that showed. By the early 9th century, Muslim traders already dominated Mediterranean and Indian Ocean trade; afterwards, they could be found as far east as Indonesia, which over time became a Muslim-majority country, and as far west as Moorish Spain.

The main focus of Islamic trade in those Middle Ages were spices. Unlike silk, spices were traded mainly by sea since ancient times. But by the medieval era they had become the true focus of international trade. Chief among them were the cloves, nutmeg and mace from the fabled Spice islands – the Maluku islands in Indonesia. They were extremely expensive and in high demand, also in Europe. But as with silk, they remained a luxury product, and trade remained relatively low volume. Globalization still didn’t take off, but the original Belt (sea route) and Road (Silk Road) of trade between East and West did now exist.

Age of Discovery (15th-18th centuries)

Truly global trade kicked off in the Age of Discovery . It was in this era, from the end of the 15th century onwards, that European explorers connected East and West – and accidentally discovered the Americas. Aided by the discoveries of the so-called “ Scientific Revolution ” in the fields of astronomy, mechanics, physics and shipping, the Portuguese, Spanish and later the Dutch and the English first “discovered”, then subjugated, and finally integrated new lands in their economies.

The Age of Discovery rocked the world. The most (in)famous “discovery” is that of America by Columbus, which all but ended pre-Colombian civilizations. But the most consequential exploration was the circumnavigation by Magellan: it opened the door to the Spice islands, cutting out Arab and Italian middlemen. While trade once again remained small compared to total GDP, it certainly altered people’s lives. Potatoes, tomatoes, coffee and chocolate were introduced in Europe, and the price of spices fell steeply.

Yet economists today still don’t truly regard this era as one of true globalization. Trade certainly started to become global, and it had even been the main reason for starting the Age of Discovery. But the resulting global economy was still very much siloed and lopsided. The European empires set up global supply chains, but mostly with those colonies they owned. Moreover, their colonial model was chiefly one of exploitation, including the shameful legacy of the slave trade. The empires thus created both a mercantilist and a colonial economy, but not a truly globalized one.

First wave of globalization (19th century-1914)

This started to change with the first wave of globalization, which roughly occurred over the century ending in 1914. By the end of the 18th century, Great Britain had started to dominate the world both geographically, through the establishment of the British Empire, and technologically, with innovations like the steam engine, the industrial weaving machine and more. It was the era of the First Industrial Revolution .

The “British” Industrial Revolution made for a fantastic twin engine of global trade. On the one hand, steamships and trains could transport goods over thousands of miles, both within countries and across countries. On the other hand, its industrialization allowed Britain to make products that were in demand all over the world, like iron, textiles and manufactured goods . “With its advanced industrial technologies,” the BBC recently wrote , looking back to the era, “Britain was able to attack a huge and rapidly expanding international market.”

Have you read?

The future of jobs report 2023, how to follow the growth summit 2023, growth summit 2023: here's what to expect.

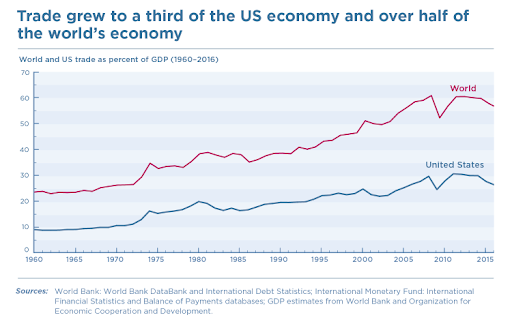

The resulting globalization was obvious in the numbers. For about a century, trade grew on average 3% per year. That growth rate propelled exports from a share of 6% of global GDP in the early 19th century, to 14% on the eve of World War I. As John Maynard Keynes, the economist, observed : “The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole Earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep.”

And, Keynes also noted, a similar situation was also true in the world of investing. Those with the means in New York, Paris, London or Berlin could also invest in internationally active joint stock companies. One of those, the French Compagnie de Suez, constructed the Suez Canal, connecting the Mediterranean with the Indian Ocean and opened yet another artery of world trade. Others built railways in India, or managed mines in African colonies. Foreign direct investment, too, was globalizing.

While Britain was the country that benefited most from this globalization, as it had the most capital and technology, others did too, by exporting other goods. The invention of the refrigerated cargo ship or “reefer ship” in the 1870s, for example, allowed for countries like Argentina and Uruguay, to enter their golden age. They started to mass export meat, from cattle grown on their vast lands. Other countries, too, started to specialize their production in those fields in which they were most competitive.

But the first wave of globalization and industrialization also coincided with darker events, too. By the end of the 19th century, the Khan Academy notes, “most [globalizing and industrialized] European nations grabbed for a piece of Africa, and by 1900 the only independent country left on the continent was Ethiopia”. In a similarly negative vein, large countries like India, China, Mexico or Japan, which were previously powers to reckon with, were not either not able or not allowed to adapt to the industrial and global trends. Either the Western powers put restraints on their independent development, or they were otherwise outcompeted because of their lack of access to capital or technology. Finally, many workers in the industrialized nations also did not benefit from globalization, their work commoditized by industrial machinery, or their output undercut by foreign imports.

The world wars

It was a situation that was bound to end in a major crisis, and it did. In 1914, the outbreak of World War I brought an end to just about everything the burgeoning high society of the West had gotten so used to, including globalization. The ravage was complete. Millions of soldiers died in battle, millions of civilians died as collateral damage, war replaced trade, destruction replaced construction, and countries closed their borders yet again.

In the years between the world wars, the financial markets, which were still connected in a global web, caused a further breakdown of the global economy and its links. The Great Depression in the US led to the end of the boom in South America, and a run on the banks in many other parts of the world. Another world war followed in 1939-1945. By the end of World War II, trade as a percentage of world GDP had fallen to 5% – a level not seen in more than a hundred years.

Second and third wave of globalization

The story of globalization, however, was not over. The end of the World War II marked a new beginning for the global economy. Under the leadership of a new hegemon, the United States of America, and aided by the technologies of the Second Industrial Revolution, like the car and the plane, global trade started to rise once again. At first, this happened in two separate tracks, as the Iron Curtain divided the world into two spheres of influence. But as of 1989, when the Iron Curtain fell, globalization became a truly global phenomenon.

In the early decades after World War II, institutions like the European Union, and other free trade vehicles championed by the US were responsible for much of the increase in international trade. In the Soviet Union, there was a similar increase in trade, albeit through centralized planning rather than the free market. The effect was profound. Worldwide, trade once again rose to 1914 levels: in 1989, export once again counted for 14% of global GDP. It was paired with a steep rise in middle-class incomes in the West.

Then, when the wall dividing East and West fell in Germany, and the Soviet Union collapsed, globalization became an all-conquering force. The newly created World Trade Organization (WTO) encouraged nations all over the world to enter into free-trade agreements, and most of them did , including many newly independent ones. In 2001, even China, which for the better part of the 20th century had been a secluded, agrarian economy, became a member of the WTO, and started to manufacture for the world. In this “new” world, the US set the tone and led the way, but many others benefited in their slipstream.

At the same time, a new technology from the Third Industrial Revolution, the internet, connected people all over the world in an even more direct way. The orders Keynes could place by phone in 1914 could now be placed over the internet. Instead of having them delivered in a few weeks, they would arrive at one’s doorstep in a few days. What was more, the internet also allowed for a further global integration of value chains. You could do R&D in one country, sourcing in others, production in yet another, and distribution all over the world.

The result has been a globalization on steroids. In the 2000s, global exports reached a milestone, as they rose to about a quarter of global GDP . Trade, the sum of imports and exports, consequentially grew to about half of world GDP. In some countries, like Singapore, Belgium, or others, trade is worth much more than 100% of GDP. A majority of global population has benefited from this: more people than ever before belong to the global middle class, and hundred of millions achieved that status by participating in the global economy.

Globalization 4.0

That brings us to today, when a new wave of globalization is once again upon us. In a world increasingly dominated by two global powers, the US and China, the new frontier of globalization is the cyber world. The digital economy, in its infancy during the third wave of globalization, is now becoming a force to reckon with through e-commerce, digital services, 3D printing. It is further enabled by artificial intelligence, but threatened by cross-border hacking and cyberattacks.

At the same time, a negative globalization is expanding too, through the global effect of climate change. Pollution in one part of the world leads to extreme weather events in another. And the cutting of forests in the few “green lungs” the world has left, like the Amazon rainforest, has a further devastating effect on not just the world’s biodiversity, but its capacity to cope with hazardous greenhouse gas emissions.

Globalization 4.0 – what it means and how it could benefit us all

What a football shirt tells us about globalization 4.0, here’s what a korean boy band can teach us about globalization 4.0, we can make sure globalization 4.0 leaves no one behind. this is how.

But as this new wave of globalization is reaching our shores, many of the world’s people are turning their backs on it. In the West particularly, many middle-class workers are fed up with a political and economic system that resulted in economic inequality, social instability, and – in some countries – mass immigration, even if it also led to economic growth and cheaper products. Protectionism, trade wars and immigration stops are once again the order of the day in many countries.

As a percentage of GDP, global exports have stalled and even started to go in reverse slightly. As a political ideology, “globalism”, or the idea that one should take a global perspective, is on the wane. And internationally, the power that propelled the world to its highest level of globalization ever, the United States, is backing away from its role as policeman and trade champion of the world.

It was in this world that Chinese president Xi Jinping addressed the topic globalization in a speech in Davos in January 2017. “Some blame economic globalization for the chaos in the world,” he said . “It has now become the Pandora’s box in the eyes of many.” But, he continued, “we came to the conclusion that integration into the global economy is a historical trend. [It] is the big ocean that you cannot escape from.” He went on the propose a more inclusive globalization, and to rally nations to join in China’s new project for international trade, “Belt and Road”.

It was in this world, too, that Alibaba a few months later opened its Silk Road headquarters in Xi’an. It was meant as the logistical backbone for the e-commerce giant along the new “Belt and Road”, the Paper reported . But if the old Silk Road thrived on the exports of luxurious silk by camel and donkey, the new Alibaba Xi’an facility would be enabling a globalization of an entirely different kind. It would double up as a big data college for its Alibaba Cloud services.

Technological progress, like globalization, is something you can’t run away from, it seems. But it is ever changing. So how will Globalization 4.0 evolve? We will have to answer that question in the coming years.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Geo-Economics and Politics .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

9 ways national security and economic cooperation are evolving

Simon Lacey and Don Rodney Junio

June 3, 2024

'Cautious optimism': Here's what chief economists think about the state of the global economy

Aengus Collins and Kateryna Karunska

May 29, 2024

European financial institutions are confronting new challenges. Here's how

Kalin Anev Janse and Kim Skov Jensen

May 22, 2024

The ZiG: Zimbabwe rolls out world’s newest currency. Here’s what to know

Spencer Feingold

May 17, 2024

Scale matters more than ever for European competitiveness. Here's why

Sven Smit and Jan Mischke

May 15, 2024

How wind energy is reshaping the future of global power and politics

Rishabh Mishra

May 14, 2024

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Globalization and Economic Growth: Empirical Evidence on the Role of Complementarities

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Faculty of Management, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM), Johor, Malaysia, Department of Management, Mobarakeh Branch, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan, Iran

Affiliation Applied Statistics Department, Economics and Administration Faculty, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- Parisa Samimi,

- Hashem Salarzadeh Jenatabadi

- Published: April 10, 2014

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824

- Reader Comments

This study was carried out to investigate the effect of economic globalization on economic growth in OIC countries. Furthermore, the study examined the effect of complementary policies on the growth effect of globalization. It also investigated whether the growth effect of globalization depends on the income level of countries. Utilizing the generalized method of moments (GMM) estimator within the framework of a dynamic panel data approach, we provide evidence which suggests that economic globalization has statistically significant impact on economic growth in OIC countries. The results indicate that this positive effect is increased in the countries with better-educated workers and well-developed financial systems. Our finding shows that the effect of economic globalization also depends on the country’s level of income. High and middle-income countries benefit from globalization whereas low-income countries do not gain from it. In fact, the countries should receive the appropriate income level to be benefited from globalization. Economic globalization not only directly promotes growth but also indirectly does so via complementary reforms.

Citation: Samimi P, Jenatabadi HS (2014) Globalization and Economic Growth: Empirical Evidence on the Role of Complementarities. PLoS ONE 9(4): e87824. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824

Editor: Rodrigo Huerta-Quintanilla, Cinvestav-Merida, Mexico

Received: November 5, 2013; Accepted: January 2, 2014; Published: April 10, 2014

Copyright: © 2014 Samimi, Jenatabadi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The study is supported by the Ministry of Higher Education of Malaysia, Malaysian International Scholarship (MIS). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Globalization, as a complicated process, is not a new phenomenon and our world has experienced its effects on different aspects of lives such as economical, social, environmental and political from many years ago [1] – [4] . Economic globalization includes flows of goods and services across borders, international capital flows, reduction in tariffs and trade barriers, immigration, and the spread of technology, and knowledge beyond borders. It is source of much debate and conflict like any source of great power.

The broad effects of globalization on different aspects of life grab a great deal of attention over the past three decades. As countries, especially developing countries are speeding up their openness in recent years the concern about globalization and its different effects on economic growth, poverty, inequality, environment and cultural dominance are increased. As a significant subset of the developing world, Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) countries are also faced by opportunities and costs of globalization. Figure 1 shows the upward trend of economic globalization among different income group of OIC countries.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824.g001

Although OICs are rich in natural resources, these resources were not being used efficiently. It seems that finding new ways to use the OICs economic capacity more efficiently are important and necessary for them to improve their economic situation in the world. Among the areas where globalization is thought, the link between economic growth and globalization has been become focus of attention by many researchers. Improving economic growth is the aim of policy makers as it shows the success of nations. Due to the increasing trend of globalization, finding the effect of globalization on economic growth is prominent.

The net effect of globalization on economic growth remains puzzling since previous empirical analysis did not support the existent of a systematic positive or negative impact of globalization on growth. Most of these studies suffer from econometrics shortcoming, narrow definition of globalization and small number of countries. The effect of economic globalization on the economic growth in OICs is also ambiguous. Existing empirical studies have not indicated the positive or negative impact of globalization in OICs. The relationship between economic globalization and economic growth is important especially for economic policies.

Recently, researchers have claimed that the growth effects of globalization depend on the economic structure of the countries during the process of globalization. The impact of globalization on economic growth of countries also could be changed by the set of complementary policies such as improvement in human capital and financial system. In fact, globalization by itself does not increase or decrease economic growth. The effect of complementary policies is very important as it helps countries to be successful in globalization process.

In this paper, we examine the relationship between economic globalization and growth in panel of selected OIC countries over the period 1980–2008. Furthermore, we would explore whether the growth effects of economic globalization depend on the set of complementary policies and income level of OIC countries.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section consists of a review of relevant studies on the impact of globalization on growth. Afterward the model specification is described. It is followed by the methodology of this study as well as the data sets that are utilized in the estimation of the model and the empirical strategy. Then, the econometric results are reported and discussed. The last section summarizes and concludes the paper with important issues on policy implications.

Literature Review

The relationship between globalization and growth is a heated and highly debated topic on the growth and development literature. Yet, this issue is far from being resolved. Theoretical growth studies report at best a contradictory and inconclusive discussion on the relationship between globalization and growth. Some of the studies found positive the effect of globalization on growth through effective allocation of domestic resources, diffusion of technology, improvement in factor productivity and augmentation of capital [5] , [6] . In contrast, others argued that globalization has harmful effect on growth in countries with weak institutions and political instability and in countries, which specialized in ineffective activities in the process of globalization [5] , [7] , [8] .

Given the conflicting theoretical views, many studies have been empirically examined the impact of the globalization on economic growth in developed and developing countries. Generally, the literature on the globalization-economic growth nexus provides at least three schools of thought. First, many studies support the idea that globalization accentuates economic growth [9] – [19] . Pioneering early studies include Dollar [9] , Sachs et al. [15] and Edwards [11] , who examined the impact of trade openness by using different index on economic growth. The findings of these studies implied that openness is associated with more rapid growth.

In 2006, Dreher introduced a new comprehensive index of globalization, KOF, to examine the impact of globalization on growth in an unbalanced dynamic panel of 123 countries between 1970 and 2000. The overall result showed that globalization promotes economic growth. The economic and social dimensions have positive impact on growth whereas political dimension has no effect on growth. The robustness of the results of Dreher [19] is approved by Rao and Vadlamannati [20] which use KOF and examine its impact on growth rate of 21 African countries during 1970–2005. The positive effect of globalization on economic growth is also confirmed by the extreme bounds analysis. The result indicated that the positive effect of globalization on growth is larger than the effect of investment on growth.

The second school of thought, which supported by some scholars such as Alesina et al. [21] , Rodrik [22] and Rodriguez and Rodrik [23] , has been more reserve in supporting the globalization-led growth nexus. Rodriguez and Rodrik [23] challenged the robustness of Dollar (1992), Sachs, Warner et al. (1995) and Edwards [11] studies. They believed that weak evidence support the idea of positive relationship between openness and growth. They mentioned the lack of control for some prominent growth indicators as well as using incomprehensive trade openness index as shortcomings of these works. Warner [24] refuted the results of Rodriguez and Rodrik (2000). He mentioned that Rodriguez and Rodrik (2000) used an uncommon index to measure trade restriction (tariffs revenues divided by imports). Warner (2003) explained that they ignored all other barriers on trade and suggested using only the tariffs and quotas of textbook trade policy to measure trade restriction in countries.

Krugman [25] strongly disagreed with the argument that international financial integration is a major engine of economic development. This is because capital is not an important factor to increase economic development and the large flows of capital from rich to poor countries have never occurred. Therefore, developing countries are unlikely to increase economic growth through financial openness. Levine [26] was more optimistic about the impact of financial liberalization than Krugman. He concluded, based on theory and empirical evidences, that the domestic financial system has a prominent effect on economic growth through boosting total factor productivity. The factors that improve the functioning of domestic financial markets and banks like financial integration can stimulate improvements in resource allocation and boost economic growth.

The third school of thoughts covers the studies that found nonlinear relationship between globalization and growth with emphasis on the effect of complementary policies. Borensztein, De Gregorio et al. (1998) investigated the impact of FDI on economic growth in a cross-country framework by developing a model of endogenous growth to examine the role of FDI in the economic growth in developing countries. They found that FDI, which is measured by the fraction of products produced by foreign firms in the total number of products, reduces the costs of introducing new varieties of capital goods, thus increasing the rate at which new capital goods are introduced. The results showed a strong complementary effect between stock of human capital and FDI to enhance economic growth. They interpreted this finding with the observation that the advanced technology, brought by FDI, increases the growth rate of host economy when the country has sufficient level of human capital. In this situation, the FDI is more productive than domestic investment.

Calderón and Poggio [27] examined the structural factors that may have impact on growth effect of trade openness. The growth benefits of rising trade openness are conditional on the level of progress in structural areas including education, innovation, infrastructure, institutions, the regulatory framework, and financial development. Indeed, they found that the lack of progress in these areas could restrict the potential benefits of trade openness. Chang et al. [28] found that the growth effects of openness may be significantly improved when the investment in human capital is stronger, financial markets are deeper, price inflation is lower, and public infrastructure is more readily available. Gu and Dong [29] emphasized that the harmful or useful growth effect of financial globalization heavily depends on the level of financial development of economies. In fact, if financial openness happens without any improvement in the financial system of countries, growth will replace by volatility.

However, the review of the empirical literature indicates that the impact of the economic globalization on economic growth is influenced by sample, econometric techniques, period specifications, observed and unobserved country-specific effects. Most of the literature in the field of globalization, concentrates on the effect of trade or foreign capital volume (de facto indices) on economic growth. The problem is that de facto indices do not proportionally capture trade and financial globalization policies. The rate of protections and tariff need to be accounted since they are policy based variables, capturing the severity of trade restrictions in a country. Therefore, globalization index should contain trade and capital restrictions as well as trade and capital volume. Thus, this paper avoids this problem by using a comprehensive index which called KOF [30] . The economic dimension of this index captures the volume and restriction of trade and capital flow of countries.

Despite the numerous studies, the effect of economic globalization on economic growth in OIC is still scarce. The results of recent studies on the effect of globalization in OICs are not significant, as they have not examined the impact of globalization by empirical model such as Zeinelabdin [31] and Dabour [32] . Those that used empirical model, investigated the effect of globalization for one country such as Ates [33] and Oyvat [34] , or did it for some OIC members in different groups such as East Asia by Guillaumin [35] or as group of developing countries by Haddad et al. [36] and Warner [24] . Therefore, the aim of this study is filling the gap in research devoted solely to investigate the effects of economic globalization on growth in selected OICs. In addition, the study will consider the impact of complimentary polices on the growth effects of globalization in selected OIC countries.

Model Specification

Methodology and Data

This paper applies the generalized method of moments (GMM) panel estimator first suggested by Anderson and Hsiao [38] and later developed further by Arellano and Bond [39] . This flexible method requires only weak assumption that makes it one of the most widely used econometric techniques especially in growth studies. The dynamic GMM procedure is as follow: first, to eliminate the individual effect form dynamic growth model, the method takes differences. Then, it instruments the right hand side variables by using their lagged values. The last step is to eliminate the inconsistency arising from the endogeneity of the explanatory variables.

The consistency of the GMM estimator depends on two specification tests. The first is a Sargan test of over-identifying restrictions, which tests the overall validity of the instruments. Failure to reject the null hypothesis gives support to the model. The second test examines the null hypothesis that the error term is not serially correlated.

The GMM can be applied in one- or two-step variants. The one-step estimators use weighting matrices that are independent of estimated parameters, whereas the two-step GMM estimator uses the so-called optimal weighting matrices in which the moment conditions are weighted by a consistent estimate of their covariance matrix. However, the use of the two-step estimator in small samples, as in our study, has problem derived from proliferation of instruments. Furthermore, the estimated standard errors of the two-step GMM estimator tend to be small. Consequently, this paper employs the one-step GMM estimator.

In the specification, year dummies are used as instrument variable because other regressors are not strictly exogenous. The maximum lags length of independent variable which used as instrument is 2 to select the optimal lag, the AR(1) and AR(2) statistics are employed. There is convincing evidence that too many moment conditions introduce bias while increasing efficiency. It is, therefore, suggested that a subset of these moment conditions can be used to take advantage of the trade-off between the reduction in bias and the loss in efficiency. We restrict the moment conditions to a maximum of two lags on the dependent variable.

Data and Empirical Strategy

We estimated Eq. (1) using the GMM estimator based on a panel of 33 OIC countries. Table S1 in File S1 lists the countries and their income groups in the sample. The choice of countries selected for this study is primarily dictated by availability of reliable data over the sample period among all OIC countries. The panel covers the period 1980–2008 and is unbalanced. Following [40] , we use annual data in order to maximize sample size and to identify the parameters of interest more precisely. In fact, averaging out data removes useful variation from the data, which could help to identify the parameters of interest with more precision.

The dependent variable in our sample is logged per capita real GDP, using the purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates and is obtained from the Penn World Table (PWT 7.0). The economic dimension of KOF index is derived from Dreher et al. [41] . We use some other variables, along with economic globalization to control other factors influenced economic growth. Table S2 in File S2 shows the variables, their proxies and source that they obtain.

We relied on the three main approaches to capture the effects of economic globalization on economic growth in OIC countries. The first one is the baseline specification (Eq. (1)) which estimates the effect of economic globalization on economic growth.

The second approach is to examine whether the effect of globalization on growth depends on the complementary policies in the form of level of human capital and financial development. To test, the interactions of economic globalization and financial development (KOF*FD) and economic globalization and human capital (KOF*HCS) are included as additional explanatory variables, apart from the standard variables used in the growth equation. The KOF, HCS and FD are included in the model individually as well for two reasons. First, the significance of the interaction term may be the result of the omission of these variables by themselves. Thus, in that way, it can be tested jointly whether these variables affect growth by themselves or through the interaction term. Second, to ensure that the interaction term did not proxy for KOF, HCS or FD, these variables were included in the regression independently.

In the third approach, in order to study the role of income level of countries on the growth effect of globalization, the countries are split based on income level. Accordingly, countries were classified into three groups: high-income countries (3), middle-income (21) and low-income (9) countries. Next, dummy variables were created for high-income (Dum 3), middle-income (Dum 2) and low-income (Dum 1) groups. Then interaction terms were created for dummy variables and KOF. These interactions will be added to the baseline specification.

Findings and Discussion

This section presents the empirical results of three approaches, based on the GMM -dynamic panel data; in Tables 1 – 3 . Table 1 presents a preliminary analysis on the effects of economic globalization on growth. Table 2 displays coefficient estimates obtained from the baseline specification, which used added two interaction terms of economic globalization and financial development and economic globalization and human capital. Table 3 reports the coefficients estimate from a specification that uses dummies to capture the impact of income level of OIC countries on the growth effect of globalization.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824.t001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824.t002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824.t003

The results in Table 1 indicate that economic globalization has positive impact on growth and the coefficient is significant at 1 percent level. The positive effect is consistent with the bulk of the existing empirical literature that support beneficial effect of globalization on economic growth [9] , [11] , [13] , [19] , [42] , [43] .

According to the theoretical literature, globalization enhances economic growth by allocating resources more efficiently as OIC countries that can be specialized in activities with comparative advantages. By increasing the size of markets through globalization, these countries can be benefited from economic of scale, lower cost of research and knowledge spillovers. It also augments capital in OICs as they provide a higher return to capital. It has raised productivity and innovation, supported the spread of knowledge and new technologies as the important factors in the process of development. The results also indicate that growth is enhanced by lower level of government expenditure, lower level of inflation, higher level of human capital, deeper financial development, more domestic investment and better institutions.

Table 2 represents that the coefficients on the interaction between the KOF, HCS and FD are statistically significant at 1% level and with the positive sign. The findings indicate that economic globalization not only directly promotes growth but also indirectly does via complementary reforms. On the other hand, the positive effect of economic globalization can be significantly enhanced if some complementary reforms in terms of human capital and financial development are undertaken.

In fact, the implementation of new technologies transferred from advanced economies requires skilled workers. The results of this study confirm the importance of increasing educated workers as a complementary policy in progressing globalization. However, countries with higher level of human capital can be better and faster to imitate and implement the transferred technologies. Besides, the financial openness brings along the knowledge and managerial for implementing the new technology. It can be helpful in improving the level of human capital in host countries. Moreover, the strong and well-functioned financial systems can lead the flow of foreign capital to the productive and compatible sectors in developing countries. Overall, with higher level of human capital and stronger financial systems, the globalized countries benefit from the growth effect of globalization. The obtained results supported by previous studies in relative to financial and trade globalization such as [5] , [27] , [44] , [45] .

Table (3 ) shows that the estimated coefficients on KOF*dum3 and KOF*dum2 are statistically significant at the 5% level with positive sign. The KOF*dum1 is statistically significant with negative sign. It means that increase in economic globalization in high and middle-income countries boost economic growth but this effect is diverse for low-income countries. The reason might be related to economic structure of these countries that are not received to the initial condition necessary to be benefited from globalization. In fact, countries should be received to the appropriate income level to be benefited by globalization.

The diagnostic tests in tables 1 – 3 show that the estimated equation is free from simultaneity bias and second-order correlation. The results of Sargan test accept the null hypothesis that supports the validity of the instrument use in dynamic GMM.

Conclusions and Implications

Numerous researchers have investigated the impact of economic globalization on economic growth. Unfortunately, theoretical and the empirical literature have produced conflicting conclusions that need more investigation. The current study shed light on the growth effect of globalization by using a comprehensive index for globalization and applying a robust econometrics technique. Specifically, this paper assesses whether the growth effects of globalization depend on the complementary polices as well as income level of OIC countries.

Using a panel data of OIC countries over the 1980–2008 period, we draw three important conclusions from the empirical analysis. First, the coefficient measuring the effect of the economic globalization on growth was positive and significant, indicating that economic globalization affects economic growth of OIC countries in a positive way. Second, the positive effect of globalization on growth is increased in countries with higher level of human capital and deeper financial development. Finally, economic globalization does affect growth, whether the effect is beneficial depends on the level of income of each group. It means that economies should have some initial condition to be benefited from the positive effects of globalization. The results explain why some countries have been successful in globalizing world and others not.

The findings of our study suggest that public policies designed to integrate to the world might are not optimal for economic growth by itself. Economic globalization not only directly promotes growth but also indirectly does so via complementary reforms.

The policy implications of this study are relatively straightforward. Integrating to the global economy is only one part of the story. The other is how to benefits more from globalization. In this respect, the responsibility of policymakers is to improve the level of educated workers and strength of financial systems to get more opportunities from globalization. These economic policies are important not only in their own right, but also in helping developing countries to derive the benefits of globalization.

However, implementation of new technologies transferred from advanced economies requires skilled workers. The results of this study confirm the importance of increasing educated workers as a complementary policy in progressing globalization. In fact, countries with higher level of human capital can better and faster imitate and implement the transferred technologies. The higher level of human capital and certain skill of human capital determine whether technology is successfully absorbed across countries. This shows the importance of human capital in the success of countries in the globalizing world.

Financial openness in the form of FDI brings along the knowledge and managerial for implementing the new technology. It can be helpful in upgrading the level of human capital in host countries. Moreover, strong and well-functioned financial systems can lead the flow of foreign capital to the productive and compatible sectors in OICs.

In addition, the results show that economic globalization does affect growth, whether the effect is beneficial depends on the level of income of countries. High and middle income countries benefit from globalization whereas low-income countries do not gain from it. As Birdsall [46] mentioned globalization is fundamentally asymmetric for poor countries, because their economic structure and markets are asymmetric. So, the risks of globalization hurt the poor more. The structure of the export of low-income countries heavily depends on primary commodity and natural resource which make them vulnerable to the global shocks.

The major research limitation of this study was the failure to collect data for all OIC countries. Therefore future research for all OIC countries would shed light on the relationship between economic globalization and economic growth.

Supporting Information

Sample of Countries.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824.s001

The Name and Definition of Indicators.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824.s002

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: PS. Performed the experiments: PS. Analyzed the data: PS. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: PS HSJ. Wrote the paper: PS HSJ.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 2. Bhandari AK, Heshmati A (2005) Measurement of Globalization and its Variations among Countries, Regions and over Time. IZA Discussion Paper No.1578.

- 3. Collins W, Williamson J (1999) Capital goods prices, global capital markets and accumulation: 1870–1950. NBER Working Paper No.7145.

- 4. Obstfeld M, Taylor A (1997) The great depression as a watershed: international capital mobility over the long run. In: D M, Bordo CG, and Eugene N White, editors. The Defining Moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press: NBER Project Report series. 353–402.

- 7. De Melo J, Gourdon J, Maystre N (2008) Openness, Inequality and Poverty: Endowments Matter. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No.3981.

- 8. Berg A, Krueger AO (2003) Trade, growth, and poverty: a selective survey. IMF Working Papers No.1047.

- 16. Barro R, Sala-i-Martin X (2004) Economic Growth. New York: McGraw Hill.

- 21. Alesina A, Grilli V, Milesi-Ferretti G, Center L, del Tesoro M (1994) The political economy of capital controls. In: Leiderman L, Razin A, editors. Capital Mobility: The Impact on Consumption, Investment and Growth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 289–321.

- 22. Rodrik D (1998) Who needs capital-account convertibility? In: Fischer S, editor. Should the IMF Pursue Capital Account Convertibility?, Essays in international finance. Princeton: Department of Economics, Princeton University. 55–65.

- 25. Krugman P (1993) International Finance and Economic Development. In: Giovannini A, editor. Finance and Development: Issues and Experience. Cambridge Cambridge University Press. 11–24.

- 27. Calderón C, Poggio V (2010) Trade and Economic Growth Evidence on the Role of Complementarities for CAFTA-DR Countries. World Bank Policy Research, Working Paper No.5426.

- 30. Samimi P, Lim GC, Buang AA (2011) Globalization Measurement: Notes on Common Globalization Indexes. Knowledge Management, Economics and Information Technology 1(7).

- 36. Haddad ME, Lim JJ, Saborowski C (2010) Trade Openness Reduces Growth Volatility When Countries are Well Diversified. Policy Research Working Paper Series NO. 5222.

- 37. Mammi I (2012) Essays in GMM estimation of dynamic panel data models. Lucca, Italy: IMT Institute for Advanced Studies.

- 41. Dreher A, Gaston N, Martens P (2008) Measuring globalisation: Gauging its consequences: Springer Verlag.

- 42. Brunner A (2003) The long-run effects of trade on income and income growth. IMF Working Papers No. 03/37.

- 44. Alfaro L, Chanda A, Kalemli-Ozcan S, Sayek S (2006) How does foreign direct investment promote economic growth? Exploring the effects of financial markets on linkages. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper.

- 46. Birdsall N (2002) A stormy day on an open field: asymmetry and convergence in the global economy. In: Gruen D, O'Brien T, Lawson J, editors. Globalisation, living standards and inequality. Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia and Australian. 66–87.

- 47. Solt F (2009) Standardizing the World Income Inequality Database. Social Science Quarterly 90: 231–242 SWIID Version 233.230, July 2010.

- 48. Beck T, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Levine R (2009) Financial Institutions and Markets across Countries and over Time. Policy Research Working Paper No.4943.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

Globalization: A Very Short Introduction (5th edn)

Author webpage

A newer edition of this book is available.

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Globalization: A Very Short Introduction looks at the interconnected and accelerated processes changing how we see and experience the world. Is globalization really a new phenomenon? Is increased connection between people and nations inevitable, or are we witnessing the beginning of an era of ‘deglobalization’ or ‘anti-globalization’? Updated with new developments including advancing climate change, the Trump presidency, and the Mexico–USA border, this VSI explores the history and impact of globalization. Chapters on the cultural, economic, political, and ecological dimensions of globalization investigate the impact of new technologies, economic deregulation, and mass migration on our world and consider what we might expect from the future of globalization.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.