An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Eldredge J. Evidence Based Practice: A Decision-Making Guide for Health Information Professionals [Internet]. Albuquerque (NM): University of New Mexico Health Sciences Library and Informatics Center; 2024.

Evidence Based Practice: A Decision-Making Guide for Health Information Professionals [Internet].

Critical appraisal.

Critical Appraisal: Wall Street. Bryce Canyon National Park. Utah

The goal of researchers should be to create accurate and unbiased representations of selected parts of reality. The goal of HIPs should be to critically examine how well these researchers achieve those representations of reality. Simultaneously, HIPs should gauge how relevant these studies are to answering their own EBP questions. In short, HIPs need to be skeptical consumers of the evidence produced by researchers.

This skepticism needs to be governed by critical thinking while recognizing that there are no perfect research studies . The expression, “The search for perfectionism is the enemy of progress,” 1 certainly applies when critically appraising evidence. HIPs should engage in “Proportional Skepticism,” meaning that finding minor flaws in a specific study does not automatically disqualify it from consideration in the EBP process. Research studies also vary in quality of implementation, regardless of whether they are systematic reviews or randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Proportional Skepticism acknowledges that some study designs are better than others at accurately representing parts of reality and answering different types of EBP questions. 2

This chapter provides tips for readers in their roles as consumers of evidence, particularly evidence produced by research studies. First, this chapter explores the various forms of bias that can cloud the representation of reality in research studies. It then presents a brief overview of common pitfalls in research studies. Many of these biases and pitfalls can easily be identified by how they might manifest in various forms of evidence, including local evidence, regional or national comparative data, and the grey literature. The emphasis in this chapter, however, is on finding significant weaknesses in research-generated evidence, as these can be more challenging to detect than in the other forms of evidence. Next, the chapter further outlines the characteristics of various research studies that might produce relevant evidence. Tables summarizing the major advantages and disadvantages of specific research designs appear throughout the chapter. Finally, critical appraisal sheets serve as appendices to the chapter. These sheets provide key questions to consider when evaluating evidence produced by the most common EBP research study designs.

- 4.1 Forms of Bias

Researchers and their research studies can be susceptible to many forms of bias, including implicit, structural, and systemic biases. These biases are deeply embedded in society and can inadvertently appear within research studies. 3 , 4 Bias in research studies can be defined as the “error in collecting or analyzing data that systematically over- or underestimates what the researcher is interested in studying.” 5 In simpler terms, bias results from an error in the design or conduct of a study. 6 As George Orwell reminds us, “..we are all capable of believing things we know to be untrue….” 7 Most experienced researchers are vigilant to avoid these types of biases, but biases can unintentionally permeate study designs or protocols irrespective of the researcher’s active vigilance. If researchers recognize these biases, they can mitigate them during their analyses or, at the very least, they should account for them in the limitations section of their research studies.

Expectancy Effect

For at least 60 years, behavioral scientists have observed a consistent phenomenon: when a researcher anticipates a particular response from someone, the likelihood of that person responding in the expected manner significantly increases. 8 This phenomenon, known as the Expectancy Effect, can be observed across research studies, ranging from interviews to experiments. In everyday life, we can observe the Expectancy Effect in action, such as when instructors selectively call on specific students in a classroom 9 , 10 or when the President or Press Secretary at a White House press conference chooses certain reporters while ignoring others. In both instances, individuals encouraged to interact with either the teacher or those conducting the press conference are more likely to seek future interactions. Robert Rosenthal, the psychologist most closely associated with uncovering and examining instances of the Expectancy Effect, has extensively documented these self-fulfilling prophecies in various everyday situations and within controlled research contexts. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 It is important to recognize that HIP research studies have the potential to be influenced by the Expectancy Effect.

Hawthorne Effect

Participants in a research study, when aware of being observed by researchers, tend to behave differently than they would in other circumstances. 15 , 16 This phenomenon, known as the Hawthorne Effect, was initially discovered in an obscure management study conducted at the Hawthorne Electric Plant in Chicago. 17 , 18

The Hawthorne Effect might be seen in HIP participant-observer research studies where researchers monitor interactions such as help calls, chat sessions, and visits to a reference desk. In such studies, the employees responding to these requests might display heightened levels of patience, friendliness, or accommodation due to their awareness of being observed, which aligns with the Hawthorne Effect. It is important to note that the Hawthorne Effect is not inevitable, 19 and there are ways for researchers to mitigate its impact. 20

Historical events have the power to significantly shape research results. A compelling illustration of this can be found in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which left a profound mark on society. The impact of this crisis was so significant that a research study on attitudes toward infectious respiratory disease conducted in 2018 would likely yield different results compared to an identical study conducted in 2021, when society was cautiously emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic. Another instance demonstrating the impact of historical events is the banking crisis and recession of 2008-2009. Notably, two separate research studies on the most important research questions facing HIPs, conducted in 2008 and 2011, respectively, for the Medical Library Association Research Agenda, had unexpected differences in results. 21 The 2011 study identified HIPs as far more concerned about issues of economic and job security than the 2008 study. 22 The authors of the 2011 study specifically attributed the increased apprehension regarding financial insecurity to these historical events related to the economy. Additionally, historical events also can affect research results over the course of a long-term study. 23

During the course of longitudinal research studies, participants might experience changes in their attitudes or their knowledge. These changes, known as Maturation Effects, can sometimes be mistaken as outcomes resulting from specific events or interventions within the research study. 24 For instance, this might happen when a HIP provides instruction to first-year students aimed at fostering a positive attitude toward conducting literature searches. Following a second session on literature searching for second-year students, an attitudinal survey might indicate a higher opinion of this newly-learned skill among medical students. At this point, one might consider whether this attitude change resulted from the two instructional sessions or if there were other factors at play, such as a separate required course on research methods or other experiences of the students between the two searching sessions. In such a case, one would have to consider attributing the change to the Maturation Effect. 25

Misclassification

Misclassification can occur at multiple junctures in a research study, including when enrolling the participants, collecting data from participants, measuring exposures or interventions, or recording outcomes. 26 Minor misclassifications can introduce outsized distortions in any one of these junctures due to the multiple instances involved. The simple task of defining a research population can introduce the risk of misclassification, even among conscientious HIP researchers. 27

HIPs work with emerging information technologies far more than any other health sciences profession. Part of this work involves assessing the performance of these new information technologies as well as working on making adaptations to these technologies. Given the frequency that HIPs work with these new technologies, there remains the potential for novelty bias to arise, which refers to the initial fascination and perhaps even an enthusiasm towards innovations during their early phases of introduction and initial use. 28 This bias has been observed in publications from various health professions, spanning a wide range of innovations, such as dentistry tooth implants 29 or presentation software. 30

Many HIPs engage in partnerships with corporate information technology firms or other external organizations to pilot new platforms. These partnerships often result in reports on these technologies, typically case reports or new product reviews. Given the nature of these relationships, it is important for all authors to provide clear conflict of interest statements. For many HIPs, however, novelty bias is still an occupational risk due to their close involvement with information technologies. To mitigate this bias, HIPs can implement two strategies: increasing the number of participants in studies and continuing to try (often unsuccessfully) to replicate any initial rosy reports. 31

Recall Bias

Recall Bias poses a risk to study designs such as surveys and interviews, which heavily rely on the participants’ ability to recollect past events accurately. The wording of surveys and questions posed by interviewers can inadvertently direct participants’ attention to certain memories, thereby distorting the information provided to researchers. 32

Scalability Bias

Scalability Bias fails to consider the applicability of a study carried out in one specific context when transferred to another context. Shadish et al 33 identify two forms: Narrow-to-Broad Bias and Broad-to-Narrow Bias.

Narrow-to-Broad Bias applies findings in one setting and suggests that these findings apply to many other settings. For example, a researcher might attempt to depict the attitudes of all students on a large campus based on the interview of a single student or by surveying only five to 15 students who belong to a student interest group. Broad-to-Narrow Bias makes the inverse mistake by assuming that what generally applies to a large population should apply to an individual or a subset of that population. In this case, a researcher might conduct a survey on a campus to gauge attitudes toward a subject and assume that the general findings apply to every individual student. Readers familiar with classical training in logic or rhetoric will recognize these two biases as the Fallacy of Composition and the Fallacy of Hasty Generalization, respectively. 34

Selection Bias

Selection Bias happens when information or data collected in a research study does not accurately or fully represent the population of interest. It emerges when a sample distorts the realities of a larger population. For example, if a survey or a series of interviews with users only include friends of the researcher, it would be susceptible to Selection Bias, as it fails to encompass the broader range of attitudes present in the entire population. Recruitment into a study might occur only through media that are followed by a subset of the larger demographic profile needed. Engagement with an online patient portal, originally designed to mitigate Selection Bias in a particular study, unexpectedly gave rise to racial disparities instead. 35

Selection Bias can originate from within the study population itself, leading to potential distortions in the findings. For example, only those who feel strongly, either negatively or positively, towards a technology might volunteer to offer opinions on it. Selection Bias also might occur when an interviewer, for instance, either encourages interviewees or discourages interviewees from speaking on a subject. In all these cases, someone exerts control over the focus of the study that then misrepresents the actual experiences of the population. Rubin 36 reminds us that systemic and structural power structures in society exert control over what perspectives are heard in a research study.

While there are many other types of bias, the descriptions explained thus far should equip the vigilant consumer of research evidence with the ability to detect potential weaknesses across a wide range of HIP research articles.

- 4.2 Other Research Pitfalls

A cause is “an antecedent event, condition, or characteristic” that precedes an outcome. A sufficient cause provides the prerequisites for an outcome to occur, while a necessary cause must exist before the outcome can occur. 37 These definitions rely on the event, condition, or characteristic to precede the outcome temporally. At the same time, the cause and its outcome must comply with biological and physical laws. There must also be a plausible strength of the association, and the link between the putative cause and the outcome must be replicable across varied instances. 38 , 39 In the past century, philosophers and physicists have examined the concept of causality exhaustively, while 40 the concept of causality has been articulated over the past 70 years in the health sciences. 41 HIPs should keep these guidelines in mind when critically appraising any claims that an identified factor “caused” a specific outcome.

Confounding

Confounding relates to the inaccurate linkage of a possible cause to an identified outcome. It means that another concurrent event, condition, or characteristic actually caused the outcome. One instance of confounding might be an advertised noontime training on a new information platform that also features a highly desirable lunch buffet. The event planners might mistakenly assume that the high attendance rate stemmed from the perceived need for the training, while the primary motivation actually was the lunch buffet. In this case, the lunch served as a confounder.

Confounding presents the most significant alternative explanation to biases when trying to determine causation. 42 One recurring EBP question that arises among HIPs and academic librarians pertains to whether student engagement with HIPs and the use of information resources leads to student success and higher graduation rates. A research team investigated this issue and found that student engagement with HIPs and information resources did indeed predict student success. During the process, they were able to identify and eliminate potential confounders that might explain student success, such as high school grade point average, standardized exams, or socioeconomic status. 43 It turns out that even artificial intelligence can be susceptible to confounding, although it can “learn” to overcome those confounders. 44 Identifying and controlling for potential confounders can even resolve seemingly intractable questions. 45 RCTs are considered far superior in controlling for known or unknown confounders than other study designs, so they are often considered to be the highest form of evidence for a single intervention study. 46

Study Population

When considering a research study as evidence for making an EBP decision, it is crucial to evaluate whether the study population closely and credibly resembles your own user population. Each study design has specific features that can help answer this question. There are some general questions to consider that will sharpen one’s critical appraisal skills.

One thing to consider is whether the study population accurately represents the population it was drawn from. Are there any concerns regarding the sample size, which might make it insufficient to represent the larger population? Alternatively, were there issues with how the researchers publicized or recruited participants? 47 Selection Bias, mentioned earlier in this chapter, might contribute to the misrepresentation of a population if the researchers improperly included or excluded potential participants. It is also important to evaluate the response rate—was it too low, which could potentially introduce a nonresponse bias? Furthermore, consider whether the researchers’ specific incentives to enroll in the study attracted nonrepresentative participants.

HIPs should carefully analyze how research study populations align with their own user populations. In other words, what are the essential relevant traits that a research population might share or not share with a user population?

Validity refers to the use of an appropriate study design with measurements that are suitable for studying the subject. 48 , 49 It also applies to the appropriateness of the conclusions drawn from the research results. 50 Researchers devote considerable energy to examining the validity of their own studies as well as those conducted by others, so validity generally resides outside the scope of this guide intended for consumers of the research evidence.

Two brief examples might convey the concept of validity. In the first example, instructors conducting a training program on a new electronic health record system might claim success based on the number of providers they train. A more valid study, however, would include clear learning objectives that lead to demonstratable skills, which can be assessed after the training. Researchers could further extend the validity by querying trainees about their satisfaction or evaluating these trainees’ skills two weeks later to gauge the retention of the training. As a second example, a research study on a new platform might increase its validity by merely not reporting the number of visits to the platform. Instead, the study could gauge the level of user engagement through factors such as downloads, time spent on the platform, or the diversity of users.

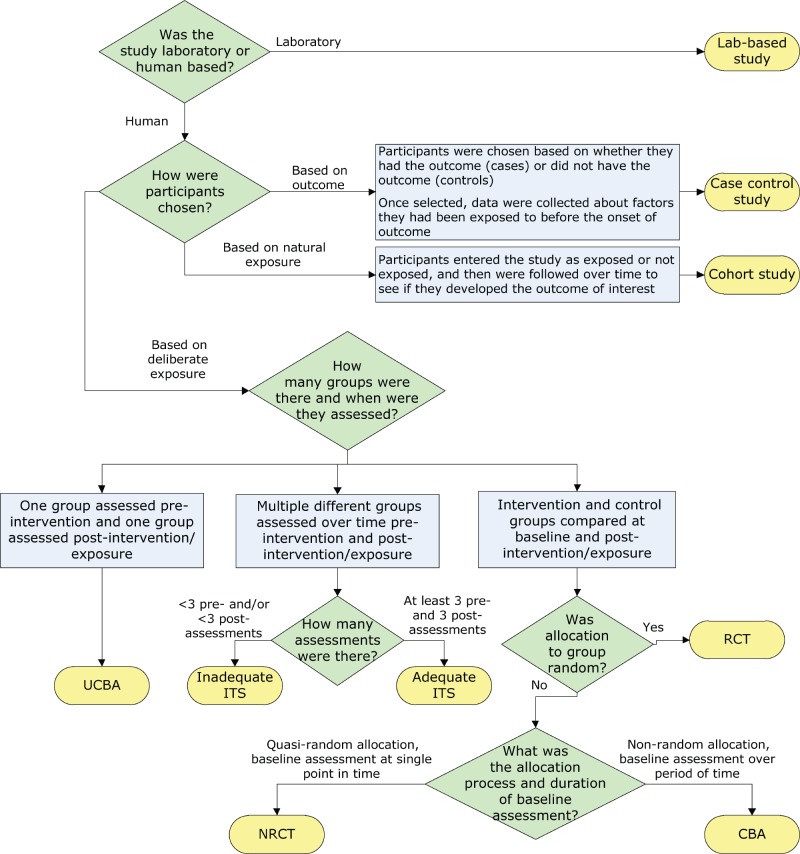

- 4.3 Study Designs

Study designs, often referred to as “research methods” in journal articles or presentations, serve as the means to test researchers’ hypotheses. Study designs can be compared to tools such as hammers, screwdrivers, saws, or utensils used in a kitchen. Both analogies emphasize the importance of using the appropriate tool or utensil for the task at hand. One would not use a hammer when a saw would be a better choice, nor would one use a spatula to ladle a cup of soup from a pot. Similarly, researchers need to take care to use study designs best suited for the research question. Likewise, HIPs engaged in EBP should recognize the suitability of study designs in answering their EBP questions. The following section provides a review of the most common study designs 51 employed to answer EBP questions, which will be further discussed in the subsequent chapter on decision making.

Types of EBP Questions

There are three major types of EBP questions that repeatedly emerge from participants in continuing education courses: Exploration, Prediction, and Intervention. Coincidentally, these major types of questions also exist in research agendas for our profession. 52 Different study designs have optimal applicability in addressing the aforementioned issues of validity and in controlling biases for each type of question.

Exploration Questions

Exploration questions are frequently concerned with understanding the reasons behind certain phenomena and often begin with “Why.” For example, a central exploration question could be, “Why do health care providers seek health information?” Paradoxically, exploration “Why” research studies often do not ask participants direct “why” questions because this approach often leads to unproductive participant responses. 53 Other exploration questions might include:

- What are the specific Point-of-Care information needs of our front-line providers?

- Why do some potential users choose never to use the journals, books, and other electronic resources that we provide?

- Do our providers find the alerts that automatically populate their electronic health records useful?

Prediction Questions

Prediction questions aim to forecast future needs based on past patterns, and HIPs frequently pose such inquiries. These questions attempt to draw a causal connection between events, conditions, or characteristics in the present with outcomes in the future. Examples of prediction questions might include:

- To what extent do students retain their EBP question formulation and searching skills after two years?

- Do hospitals that employ HIPs produce better patient outcomes, as indicated by measures such as length of stay, mortality rates, or infection rates?

- Which archived committee meeting minutes within my organization are likely to be utilized within the next 30 years?

Intervention Questions

Intervention questions aim to distinguish between different potential courses of action to determine their effectiveness in achieving specific desirable outcomes. Examples of intervention questions might include:

- Does providing training on EBP question formulation and searching lead to an increase in information-seeking behavior among public health providers in rural practices?

- Which instructional approach yields better performance among medical students on standardized national licensure exams: didactic lecture or active learning with application exercises?

- Which Point-of-Care tool, DynaMed or UpToDate, generates more answers to patient care questions and higher provider satisfaction?

Case Reports

Case reports ( Table 1 ) are prevalent in the HIP literature and are often referred to interchangeably as “Case Studies.” 54 They are records of a single program, project, or experience, 55 with a particular focus on new developments or programs. These reports provide rich details on a single instance in a narrative format that is easy to understand. When done correctly, they can be far more challenging to develop than expected, contrary to the misconception that they are easy to assemble. 56 The most popular case reports revolve around innovation, which is broadly defined as “an idea, practice, or object” perceived to be new.” 57 A HIP innovation might be a new information technology, management initiative, or outreach program. A case report might also be the only available evidence due to the newness of the innovation, and in some rare instances, a case report might be the only usable evidence. For this reason, case reports hold the potential to point to new directions or emerging trends in the profession.

While case reports can serve an educational purpose and are generally interesting to read, they are not without controversy. Some researchers do not consider case reports as legitimate sources of research evidence, 58 and practitioners often approach them with skepticism. There are many opportunities for authors to unintentionally introduce biases into case reports. Skeptical practitioners criticize the unrealistic and overly positive accounts of innovations found in some case reports.

Case reports focus solely on a single instance of an innovation or noteworthy experience. 59 As a pragmatic matter, it can be difficult to justify adopting a program based on a case report carried out in one specific and different context. To illustrate the challenges of using case reports statistically, consider a hypothetical scenario: HIPs at 100 institutions might attempt to implement a highly publicized new information technology. HIPs at 96 of those institutions experience frustration at the poor performance of the new technology, and many eventually abandon it. Meanwhile, in this scenario, HIPs at four institutions present their highly positive case reports on their experiences with the new technology at an annual conference. These reports subsequently appear in the literature six months later. While these four case reports do not even reach the minimum standard for statistical significance, they become part of the only evidence base available for the new technology, thereby gaining prominence solely from “Survivor Bias” as they alone continued when most efforts to implement the new technology had failed. 60 , 61

Defenders of case reports argue that some of these issues can be mitigated when the reports include more rigorous elements. 62 , 63 For instance, a featured program in a case report might detail how carefully the authors evaluated the program using multiple meaningful measurements. 64 Another case report might document a well-conducted survey that provides plausible results in order to gauge peoples’ opinions. Practitioners tend to view case reports more favorably when they provide negative aspects of the program or innovation, framing them as “lessons learned.” Multiple authors representing different perspectives or institutions 65 seem to garner greater credibility. Full transparency, where authors make foundational documents and data available to readers, further bolsters potential applicability. Finally, a thorough literature review of other research studies, providing context and perhaps even external support for the case report’s results, can further increase credibility. 66 All of these elements increase the likelihood that the featured case report experience could potentially be transferred to another institution.

Case reports gain greater credibility, statistical probability, and transferability when combined with other case reports on the same innovation or similar experience, forming a related, although separate, study design known as a case series. Similar to case reports, case series gain greater credibility when their observations across cases are accompanied by literature reviews. 67

Interviews ( Table 2 ) are another common HIP research design. Interviews aim to understand the thoughts, preferences, or feelings of others. Interviews take different forms, including in-person or remote settings, as well as structured or unstructured questionnaires. They can involve one interviewer and one interviewee or a small team of interviewers who conduct group interviews, often referred to as a focus group. 68 , 69 , 70 While interviews technically fall under the category of surveys, they are discussed separately here due to their popularity in the HIP literature and the unique role of the interviewer in mediating and responding to interviewees.

Interviews can be highly exploratory, allowing researchers to discover unrecognized patterns or sentiments regardless of format. They might uniquely be able to answer “why?” research questions or probe interviewees’ motivations. 71 Interviews can sometimes lead to associations that can be further tested using other study designs. For instance, a set of interviews with non-hospital-affiliated practitioners about their information needs 72 can lead to an RCT comparing preferences for two different Point-of-Care tools. 73

Interviews have the potential to introduce various forms of biases. To minimize bias, researchers can employ strategies such as recruiting a representative sample of participants, using a neutral party to conduct the interviews, following a standardized protocol to ensure participants are interviewed equitably, and avoiding leading questions. The flexibility for interviewers to mediate and respond offers the strength to discover new insights. On balance, this flexibility also carries the risk of introducing bias if interviewers inject their own agendas into the interaction. Considering these potential biases, interviews are ranked below descriptive surveys in the Levels of Evidence discussed later in this chapter. To address concerns about bias, researchers should ensure that interviews thoroughly document and analyze all de-identified data collected in a transparent manner, allowing practitioners reviewing these studies to detect and mitigate any potential biases.

Descriptive Surveys

Surveys are an integral part of our society. Every ten years, Article 1, Section 2 of the United States Constitution requires everyone living in the United States to report demographic and other information about themselves as part of the Census. Governments have been taking censuses ever since ancient times in Babylon, Egypt, China, and India. 74 , 75 While censuses might offer highly accurate portrayals, they are time-consuming, complex, and expensive endeavors.

Most descriptive surveys involve polling a finite sample of the population, making sample surveys less time-consuming and less expensive compared to censuses. Surveys involving samples, however, are still complex. Surveys can be defined as a method for collecting information about a population of people. 76 They aim to describe, compare, or explain individual and societal knowledge, feelings, values, preferences, and behaviors.” 77 Surveys are accessed by respondents without a live intermediary administering them. For participants, surveys are almost always confidential and are often anonymous. There are three basic types of surveys: descriptive, change metric, and consensus.

Descriptive surveys ( Table 3 ) elicit respondents’ thoughts, emotions, or experiences regarding a subject or situation. Cross-sectional studies are one type of descriptive survey. 78 , 79 Change metric surveys are part of a cohort or experimental study where at least one survey takes place prior to an exposure or intervention. Later on during the study, the same participants are surveyed again to assess any changes or the extent of change. Sometimes, change metric surveys gauge the differences between user expectations and actual user experiments in surveys, known as Gap Analyses. Change metric surveys resemble descriptive surveys. They are discussed in subsequent study designs later in this chapter. The aim of consensus surveys is to facilitate agreement among groups regarding collective preferences or goals, even in situations where initial consensus might seem elusive. Consensus survey techniques on decision-making in EBP will be discussed in the next chapter.

Descriptive surveys are likely the most utilized research study design employed by HIPs. 80 The common use of surveys by HIP researchers and in society at large is one of the greatest weaknesses of descriptive surveys. While surveys are familiar, they have numerous pitfalls and limitations. 81 , 82 , 83 Even when large-scale public opinion surveys are conducted by experts, discrepancies often exist between survey results and actual population behavior, as evidenced by repeated erroneous election predictions by veteran pollsters. 84

Beyond the inherent limitations of survey designs, there are multiple points where researchers can unintentionally introduce bias or succumb to other pitfalls. Problems can arise at the outset when researchers design a survey without conducting an adequate literature review to consider the previous research on the subject. The survey instrument itself might contain confusing or misleading questions, including asking leading questions that elicit a “correct” answer rather than a truthful response. 85 , 86 For example, a question about alcohol consumption in a week might face validity issues due to social stigma. The recruitment process and the characteristics of participants can also introduce Selection Bias. 87 The introduction of the survey of the medium through which participants interact with the survey might underrepresent some demographic groups based on age, gender, class, or ethnicity. It is also important to consider the representativeness of the sample in relation to the target population. Is the sample large enough? 88 Interpreting survey results, particularly answers to open-ended questions, can also distort the study results. Regardless of how straightforward surveys might appear to participants or to the casual observer, they are oftentimes complex endeavors. 89 It is no wonder that the classic Survey Kit consists of 10 volumes to explain all the details that need to be attended to for a more successful survey. 90

Cohort Studies

Cohort studies ( Table 4 ) are one of several observational study designs that focus on observing possible causes (referred to as “exposures”) and their potential outcomes within a specific population. In cohort studies, investigators collect observations, usually in the form of data, without directly interjecting themselves into the situation. Cohort members are identified without the need for the explicit enrollment typically required in other designs. Figure 1 depicts the elements of a defined population, the exposure of interest, and the hypothesized outcome(s) in cohort studies. Cohort studies are fairly popular HIP research designs, although they are rarely labeled as such in the research literature. Cohort studies can be either prospective or retrospective. Retrospective cohort studies are conducted after the exposure has already occurred to some members of a cohort. These studies focus on examining past exposures and their impact on outcomes. 91

Cohort Study Design. Copyright Jonathan Eldredge. © 2023.

Many HIPs conducting studies on resource usage employ the retrospective cohort design. These studies link resource usage patterns to past exposures that might explain the observed patterns. That exposure might be a feature in the curriculum that requires learners to use that resource, or it could be an institutional expectation for employees to complete an online training module, which affects the volume of traffic on the module. On the other hand, prospective cohort studies begin in the present by identifying a cohort within the larger population and observing the exposure of interest and whether this exposure leads to an identified outcome. The researchers are collecting specific data as the cohort study progresses, including whether cohort members have been exposed and, if so, the duration or intensity of the exposure. These varied levels of exposure might be likened to different drug dosages.

Prospective cohort studies are generally regarded as less prone to bias or confounding than retrospective studies because researchers are intentional about collecting all measures throughout the study period. In contrast, retrospective studies are dependent on data collected in the past for other purposes. Those pre-existing compiled data sets might have missing elements necessary for the retrospective study. For example, in a retrospective cohort study, usage or traffic data on an online resource might have been originally collected by an institution to monitor the maintenance, increase, or decrease in the number of licensed simultaneous users. These data were originally gathered for administrative purposes, rather than for the primary research objectives of the study. Similarly, in a retrospective cohort study investigating the impact of providing tablets (exposure) to overcome barriers in using a portal (outcome), there might be a situation where the inventory system, initially created to track the distribution of tablets, is repurposed for a different objective, such as video conferencing. 92 Cohort studies regularly use change metric surveys, as discussed above. Prospective cohort studies are better at monitoring cohort members over the study duration, while retrospective cohort studies do not always have a clearly identified cohort membership due to the possible participant attrition not recorded in the outcomes. For this reason, plus the potentially higher integrity of the intentionally collected data, prospective cohort studies tend to be considered a higher form of evidence. The increased use of electronic inventories and the collection of greater amounts of data sometimes means that a data set created for one purpose can still be repurposed for a retrospective cohort study.

Quasi-Experiment

In contrast to observational studies like cohort studies, which involve researchers simply observing exposures and then measuring outcomes, quasi-experiments ( Table 5 ) include the active involvement of researchers in an intervention that is an intentional exposure. In quasi-experiments, researchers deliberately intervene and engage all members of a group of participants. 93 These interventions can take the form of training programs or work requirements that involve participants interacting with a new electronic resource, for example. Quasi-experiments are often employed by instructors who pre-test a group of learners, provide them with training on a specific skill or subject, and then conduct a post-test to measure the learners’ improved level of comprehension. 94 In this scenario, there is usually no explicit comparison with another untrained group of learners. The researchers’ active involvement tends to reduce some forms of bias and other pitfalls. Confounding, nevertheless, represents one looming potential weakness in quasi-experiments since a third unknown factor, a confounder, might be associated with the training and outcome but goes unrecognized by the researchers. 95 Quasi-experiments do not use randomization, which also can eliminate most confounders.

Quasi-Experiments

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

RCTs ( Table 6 ) are highly effective in resolving a choice between two seemingly reasonable courses of action. RCTs have helped answer some seemingly unresolvable HIP decisions in the past, including:

Randomized Controlled Trails (RCTs)

- Do embedded clinical librarians OR the availability of a reference service improve physician information-seeking behavior? 96 , 97

- Does weeding OR not weeding a collection lead to higher usage in a physical book collection? 98

- Does training in Evidence Based Public Health skills OR the lack of this training lead to an increase in public health practitioners’ formulated questions? 99

Paradoxically, RCTs are relatively uncommon in the HIP evidence base despite their powerful potential to resolve challenging decisions. 100 One explanation might be that, in the minds of the public and many health professionals, RCTs are often associated with pharmaceutical treatments. Researchers, however, have used RCTs far more broadly to resolve questions about devices, lifestyle modifications, or counseling in the realm of health care. Some HIP researchers believe that RCTs are too complex to implement, and some even consider RCTs to be unethical. These misapprehensions should be resolved by a closer reading about RCTs in this section and in the referenced sources.

Some HIPs, in their roles as consumers of research evidence, consider RCTs too difficult to interpret. This misconception might stem from the HIPs’ past involvement in systematic review teams that have evaluated pharmaceutical RCTs. Typically, these teams use risk-of-bias tools, which might appear overly complex to many HIPs. The most commonly used risk-of-bias tool 101 for critically appraising pharmaceutical RCTs appears to be published by Cochrane, particularly its checklist for identifying sources of bias. 102 Those HIPs involved with evaluating pharmaceutical RCTs should familiarize themselves with this resource. This section of Chapter 4 focuses instead on aspects of RCTs that HIPs might encounter in the HIP evidence base.

A few basic concepts and explanations of RCT protocols should alleviate any reluctance to use RCTs in the EBP Process. The first concept of equipoise means that researchers undertook the RCT because they were genuinely uncertain about which course of action among the two choices would lead to the more desired outcomes. Equipoise has practical and ethical dimensions. If prior studies have demonstrated a definitively superior course of action between the two choices, researchers would not invest their time and effort in pursuing an already answered question unless they needed to replicate the study. From an ethical perspective, why would researchers subject control group participants to a clearly inferior choice? 103 , 104 The background or introduction section of an article about RCTs should establish equipoise by drawing on evidence from past studies.

Figure 2 illustrates that an RCT begins with a representative sample of the larger population. Many consumers of RCTs should bear in mind that the number of participants in a study depends on more than a “magic number”; it also relies on the availability of eligible participants and the statistical significance of any differences measured. 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 Editors, peer reviewers, and statistical consultants at peer-reviewed journals play a key role in screening manuscripts for any major statistical problems.

Randomized Controlled Trial.

Recruiting a representative sample can be a challenge for researchers due to the various communication channels used by different people. Consumers of RCTs should be aware of these issues since they affect the applicability of any RCT to one’s local setting. Several studies have documented age, gender, socioeconomic, and ethnic underrepresentation in RCTs. 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 One approach to addressing this issue is to tailor the incentives for participation based on the appeals to different underrepresented groups. 114 Close collaboration with underrepresented groups through community outreach also can help increase participation. Many RCTs include a table that records the demographic representation of participants in the study, along with the demographic composition of those who dropped out. HIPs evaluating an RCT can scrutinize this table to assess how closely the study’s population aligns with their own user population. RCTs oftentimes screen out potential participants who are unlikely to adhere to the study protocol or who are likely to drop out. Participants who will be unavailable during key study dates might also be removed. HIP researchers might want to exclude potential participants who have prior knowledge of a platform under study or who might be repeating an academic course where they were previously exposed to the same content. These preliminary screening measures cannot anticipate all eventualities, which is why some articles include a CONSORT diagram to provide a comprehensive overview of the study design. 115

RCTs often control for most biases and confounding through randomization . Imagine you’re in the tenth car in a right-hand lane approaching a traffic signal at an intersection, and no one ahead of you uses their turn signal. You want to take a right turn immediately after the upcoming intersection. In this situation, you don’t know which cars will actually turn right and which ones will proceed straight. If you want to stay in the right-hand lane without turning right, you can’t predict who will slow you down by taking a right or who will continue at a faster pace straight ahead to your own turnoff. This scenario is similar to randomization in RCTs because, just like in the traffic situation, you don’t know in advance which participants will be assigned to each course of action. Randomization ensures that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to either group regardless of the allocation of others before them, effectively eliminating the influence of bias, confounding, or any other unknown factors that could impact the study’s outcomes.

Contamination poses a threat to the effectiveness of the randomization. It occurs when members of the intervention or control groups interact and collaborate, thereby inadvertently altering the intended effects of the study. RCTs normally have an intervention group that receives a new experience, which will possibly lead to more desired outcomes. The intervention can involve accessing new technology, piloting a new teaching style, receiving specialized training content, or other deliberate actions by the researchers. On the other hand, control group members typically receive the established technology, experience the usual teaching techniques, receive standard training content, or have the usual set of experiences.

Contamination might arise when members of the intervention and control groups exchange information about their group’s experiences. Contamination interferes with the researchers deliberately treating the intervention and control groups differently. For example, in an academic setting, contamination might happen if the intervention group receives new training while the control group receives traditional training. In a contamination scenario, members of the two groups would exchange information. When their knowledge or skills are tested at the end of the study, the assessment might not accurately reflect their comparative progress since both groups have been exposed to each other’s training. A Delphi Study generated a list of common sources of contamination in RCTs, including participants’ physical proximity, frequent interaction, and high desirability of the intervention. 116 Information technology can assist researchers in avoiding, or at least countering, contamination by interacting with study participants virtually rather than in a physical environment. Additionally, electronic health records can similarly be employed in studies while minimizing contamination. 117

RCTs often employ concealment (“blinding”) techniques to ensure that participants, researchers, statisticians, and other analysts are unaware of which participants are enrolled in either the intervention or control groups. Concealment prevents participants from deviating from the protocols. Concealment also reduces the likelihood that the researchers, statisticians, or analysts interject their views into the study protocol, leading to unintended effects or biases. 118

Systematic Reviews

Systematic reviews ( Table 7 ) strive to offer a transparent and replicable synthesis of the best evidence to answer a narrowly focused question. They often involve exhaustive searches of the peer-reviewed literature. While many HIPs have participated in teams conducting systematic reviews, these efforts primarily serve health professions outside of HIP subject areas. 119 Systematic reviews can be time-consuming and labor-intensive endeavors. They rely on a number of the same critical appraisal skills covered in this chapter and its appendices to evaluate multiple studies.

Systematic reviews can include evidence produced by any study design except other reviews. Producers of systematic reviews often exclude study designs more prone to biases or confounding when a sufficient number of studies with fewer similar limitations are available. Systematic reviews are popular despite being relatively limited in number. If well-conducted, they can bypass the first three steps of the EBP Process and position the practitioner well to make an informed decision. The narrow scope of systematic reviews, however, does limit their applicability to a broad range of decisions.

Nearly all HIPs have used the findings of systematic reviews for their own EBP questions. 120 Since much of the HIP evidence base exists outside of the peer-reviewed literature, systematic reviews on HIP subjects can include grey literature, such as presented papers or posters from conferences or white papers from organizations. The MEDLINE database has a filter for selecting systematic reviews as an article type when searching the peer-reviewed literature. Unfortunately, this filter sometimes mistakenly includes meta-analyses and narrative review articles due to the likely confusion among indexers regarding the differences between these article types. It is important to note that meta-analyses are not even a design type; instead, they are a statistical method used to aggregate data sets from more than one study. They can be used for comparative study or systematic review study design types, but some people equate them solely to systematic reviews.

Narrative reviews, on the other hand, are an article type that provides a broad overview of a topic and often lacks the more rigorous features of a systematic review. Scoping reviews have increased in popularity in recent years but have a descriptive purpose that contrasts with systematic reviews. Sutton et al 121 have published an impressive inventory of the many types of reviews that might be confused with systematic reviews. The authors of systematic reviews themselves might contribute to the confusion by mislabeling these studies. The Library, Information Science, and Technology Abstracts database does not offer a filter for systematic reviews, so a keyword approach should be used when searching, followed by a manual screening of the resulting references.

Systematic reviews offer the potential to avoid many of the biases and pitfalls described at the beginning of this chapter.

In actuality, they can fall short of this potential to varying degrees, ranging from minor to monumental ways. The question being addressed needs to be narrowly focused to make the subsequent process manageable, which might disqualify some systematic reviews from application to HIPs’ actual EBP questions. The literature search might not be comprehensive, either due to limited sources searched or inadequately executed searches, leading to the possibility of missing important evidence. The searches might not be documented well enough to be reproduced by other researchers. The exclusion and inclusion criteria for identified studies might not calibrate with the needs of HIPs. The critical appraisal in some systematic reviews might exclude reviewed studies for trivial deficiencies or include studies with major flaws. The recommendations of some systematic reviews, therefore, might not be supported by the identified best available evidence.

Levels of Evidence

The Levels of Evidence, also known as “Hierarchies of Evidence,” are valuable sources of guidance in EBP. They serve as a reminder to busy practitioners that study designs at lower levels have difficulty in avoiding, controlling, or compensating for the many forms of bias or confounding that can affect research studies. Study designs at higher levels tend to be better at controlling biases. For example, higher-level study designs like RCTs can effectively control confounding. Table 8 organizes study designs according to EBP question type and arrays them into their approximate levels. In Table 8 , the “Intervention Question” column recognizes that a properly conducted systematic review incorporating multiple studies is generally more desirable for making an EBP decision compared to a case report. This is because the latter can be vulnerable to many forms of bias and confounding that rely on findings from a single instance. A systematic review, on the other hand, is ranked higher than even an RCT because it combines all available evidence from multiple studies and subjects them to a critical review, leading to a recommendation for making a decision.

Levels of Evidence: An Approximate Hierarchy Linked to Question Type

There are several important caveats to consider when using the Levels of Evidence. As noted earlier in this chapter, no perfect research study exists, and even higher-level of evidence research studies can have weaknesses. Hypothetically, an RCT could be so poorly executed that a well-conducted case report on the same topic could outshine it. While this is possible, it is highly unlikely due to the superior design of an RCT for controlling confounding or biases. Sometimes, a case report might be slightly more relevant than an RCT in answering an Intervention-type of EBP question. For these reasons, one cannot abandon their critical thinking skills even with a tacit acceptance of the Levels of Evidence.

The Levels of Evidence have been widely endorsed by HIP leaders for many years. 122 , 123 They undergo occasional adjustments, but their general organizing principles of controlling biases and other pitfalls remain intact. On balance, two of my otherwise respected colleagues have misinterpreted aspects of the early Levels of Evidence and made that the basis of their criticism. 124 , 125 A fair reading of the evolution of the Levels of Evidence over the years 126 , 127 , 128 , 129 should convince most readers that, when coupled with critical thinking, the underlying principles of the Levels of Evidence continue to provide HIPs with sound guidance.

Critical Appraisal Sheets

The critical appraisal sheets appended to this chapter are intended to serve as a guide for HIPs as they engage in critical appraisal of their potential evidence. The development of these sheets has been a culmination of over 20 years of effort. They draw upon my doctoral training in research methods, as well as my extensive experience conducting research using various study designs. Additionally, I have insights from multiple authorities. While it is impossible to credit all sources that have influenced the development of these sheets over the years, I have cited the readily recognized ones at the end of this sentence. 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 , 134 , 135 , 136 , 137 , 138 , 139 , 140 , 141

- Critical Appraisal Worksheets

Appendix 1: Case Reports

Instructions: Answer the following questions to critically appraise this piece of evidence.

Appendix 2: Interviews

Appendix 3: descriptive surveys.

Instructions: Answer the following questions to critically appraise this piece of evidence

Appendix 4: Cohort Studies

Appendix 5: quasi-experiments, appendix 6: randomized controlled trials, appendix 7: systematic reviews.

This is an open access publication. Except where otherwise noted, this work is distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED), a copy of which is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ .

This open access peer-reviewed Book is brought to you at no cost to you by the Health Sciences Center at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in the Faculty Book Display Case by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected].

- Cite this Page Eldredge J. Evidence Based Practice: A Decision-Making Guide for Health Information Professionals [Internet]. Albuquerque (NM): University of New Mexico Health Sciences Library and Informatics Center; 2024. Critical Appraisal.

- PDF version of this title (32M)

In this Page

Related information.

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Recent Activity

- Critical Appraisal - Evidence Based Practice Critical Appraisal - Evidence Based Practice

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Mayo Clinic Libraries

- Evidence Synthesis Guide

- Risk of Bias by Study Design

Evidence Synthesis Guide : Risk of Bias by Study Design

- Review Types & Decision Tree

- Standards & Reporting Results

- Materials in the Mayo Clinic Libraries

- Training Resources

- Review Teams

- Develop & Refine Your Research Question

- Develop a Timeline

- Project Management

- Communication

- PRISMA-P Checklist

- Eligibility Criteria

- Register your Protocol

- Other Screening Tools

- Grey Literature Searching

- Citation Searching

- Minimize Bias

- GRADE & GRADE-CERQual

- Data Extraction Tools

- Synthesis & Meta-Analysis

- Publishing your Review

- Mayo Clinic Libraries Evidence Synthesis Service

Risk of Bias of Individual Studies

““Assessment of risk of bias is a key step that informs many other steps and decisions made in conducting systematic reviews. It plays an important role in the final assessment of the strength of the evidence.” 1

Risk of Bias by Study Design (featured tools)

- Systematic Reviews

- Non-RCTs or Observational Studies

- Diagnostic Accuracy

- Animal Studies

- Qualitative Research

- Tool Repository

- AMSTAR 2 The original AMSTAR was developed to assess the risk of bias in systematic reviews that included only randomized controlled trials. AMSTAR 2 was published in 2017 and allows researchers to identify high quality systematic reviews, including those based on non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions. more... less... AMSTAR 2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews)

- ROBIS ROBIS is a tool designed specifically to assess the risk of bias in systematic reviews. The tool is completed in three phases: (1) assess relevance(optional), (2) identify concerns with the review process, and (3) judge risk of bias in the review. Signaling questions are included to help assess specific concerns about potential biases with the review. more... less... ROBIS (Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews)

- BMJ Framework for Assessing Systematic Reviews This framework provides a checklist that is used to evaluate the quality of a systematic review.

- CASP Checklist for Systematic Reviews This CASP checklist is not a scoring system, but rather a method of appraising systematic reviews by considering: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What are the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CEBM Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance, and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools, Checklist for Systematic Reviews JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- RoB 2 RoB 2 provides a framework for assessing the risk of bias in a single estimate of an intervention effect reported from a randomized trial, rather than the entire trial. more... less... RoB 2 (revised tool to assess Risk of Bias in randomized trials)

- CASP Randomised Controlled Trials Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of an RCT that require critical appraisal: 1. Is the basic study design valid for a randomized controlled trial? 2. Was the study methodologically sound? 3. What are the results? 4. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CONSORT Statement The CONSORT checklist includes 25 items to determine the quality of randomized controlled trials. Critical appraisal of the quality of clinical trials is possible only if the design, conduct, and analysis of RCTs are thoroughly and accurately described in the report. more... less... CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials)

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- ROBINS-I ROBINS-I is a tool for evaluating risk of bias in estimates of the comparative effectiveness… of interventions from studies that did not use randomization to allocate units to comparison groups. more... less... ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias in Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions)

- NOS This tool is used primarily to evaluate and appraise case-control or cohort studies. more... less... NOS (Newcastle-Ottawa Scale)

- AXIS Cross-sectional studies are frequently used as an evidence base for diagnostic testing, risk factors for disease, and prevalence studies. The AXIS tool focuses mainly on the presented study methods and results. more... less... AXIS (Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies)

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment Tools for Non-Randomized Studies The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. • Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies • Quality Assessment of Case-Control Studies • Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies With No Control Group • Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series Studies more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- Case Series Studies Quality Appraisal Checklist Developed by the Institute of Health Economics (Canada), the checklist is comprised of 20 questions to assess the robustness of the evidence of uncontrolled case series studies.

- Methodological Quality and Synthesis of Case Series and Case Reports In this paper, Dr. Murad and colleagues present a framework for appraisal, synthesis and application of evidence derived from case reports and case series.

- MINORS The MINORS instrument contains 12 items and was developed for evaluating the quality of observational or non-randomized studies. This tool may be of particular interest to researchers who would like to critically appraise surgical studies. more... less... MINORS (Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools for Non-Randomized Trials JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis. • Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies • Checklist for Case Control Studies • Checklist for Case Reports • Checklist for Case Series • Checklist for Cohort Studies

- QUADAS-2 The QUADAS-2 tool is designed to assess the quality of primary diagnostic accuracy studies it consists of 4 key domains that discuss patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow of patients through the study and timing of the index tests and reference standard. more... less... QUADAS-2 (a revised tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools Checklist for Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- STARD 2015 The authors of the standards note that essential elements of diagnostic accuracy study methods are often poorly described and sometimes completely omitted, making both critical appraisal and replication difficult, if not impossible. The Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies was developed to help improve completeness and transparency in reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies. more... less... STARD 2015 (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies)

- CASP Diagnostic Study Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of diagnostic test studies including: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What were the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CEBM Diagnostic Critical Appraisal Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance, and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- SYRCLE’s RoB Implementation of SYRCLE’s RoB tool will facilitate and improve critical appraisal of evidence from animal studies. This may enhance the efficiency of translating animal research into clinical practice and increase awareness of the necessity of improving the methodological quality of animal studies. more... less... SYRCLE’s RoB (SYstematic Review Center for Laboratory animal Experimentation’s Risk of Bias)

- ARRIVE 2.0 The ARRIVE 2.0 guidelines are a checklist of information to include in a manuscript to ensure that publications on in vivo animal studies contain enough information to add to the knowledge base. more... less... ARRIVE 2.0 (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments)

- Critical Appraisal of Studies Using Laboratory Animal Models This article provides an approach to critically appraising papers based on the results of laboratory animal experiments, and discusses various bias domains in the literature that critical appraisal can identify.

- CEBM Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of qualitative research studies including: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What were the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias Tool Repository Created by librarians at Duke University, this extensive listing contains over 100 commonly used risk of bias tools that may be sorted by study type.

- Latitudes Network A library of risk of bias tools for use in evidence syntheses that provides selection help and training videos.

References & Recommended Reading

1. Viswanathan, M., Patnode, C. D., Berkman, N. D., Bass, E. B., Chang, S., Hartling, L., ... & Kane, R. L. (2018). Recommendations for assessing the risk of bias in systematic reviews of health-care interventions . Journal of clinical epidemiology , 97 , 26-34.

2. Kolaski, K., Logan, L. R., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2024). Guidance to best tools and practices for systematic reviews . British Journal of Pharmacology , 181 (1), 180-210

3. Fowkes FG, Fulton PM. Critical appraisal of published research: introductory guidelines. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1991;302(6785):1136-1140.

4. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2017;358:j4008.

5.. Whiting P, Savovic J, Higgins JPT, et al. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016;69:225-234.

6. Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2019;366:l4898.

7. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2010;63(8):e1-37.

8.. Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2016;355:i4919.

9. Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ open. 2016;6(12):e011458.

10. Guo B, Moga C, Harstall C, Schopflocher D. A principal component analysis is conducted for a case series quality appraisal checklist. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016;69:199-207.e192.

11. Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ evidence-based medicine. 2018;23(2):60-63.

12. Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ journal of surgery. 2003;73(9):712-716.

13. Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Annals of internal medicine. 2011;155(8):529-536.

14. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2015;351:h5527.

15. Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RBM, Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Langendam MW. SYRCLE's risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC medical research methodology. 2014;14:43.

16. Percie du Sert N, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, et al. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS biology. 2020;18(7):e3000411.

17. O'Connor AM, Sargeant JM. Critical appraisal of studies using laboratory animal models. ILAR journal. 2014;55(3):405-417.

- << Previous: Minimize Bias

- Next: GRADE & GRADE-CERQual >>

- Last Updated: Oct 23, 2024 2:48 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.mayo.edu/systematicreviewprocess

- University of Texas Libraries

- UT Libraries

Systematic Reviews & Evidence Synthesis Methods

Critical appraisal.

- Types of Reviews

- Formulate Question

- Find Existing Reviews & Protocols

- Register a Protocol

- Searching Systematically

- Search Hedges and Filters

- Supplementary Searching

- Managing Results

- Deduplication

- Glossary of Terms

- Librarian Support

- Systematic Review & Evidence Synthesis Boot Camp

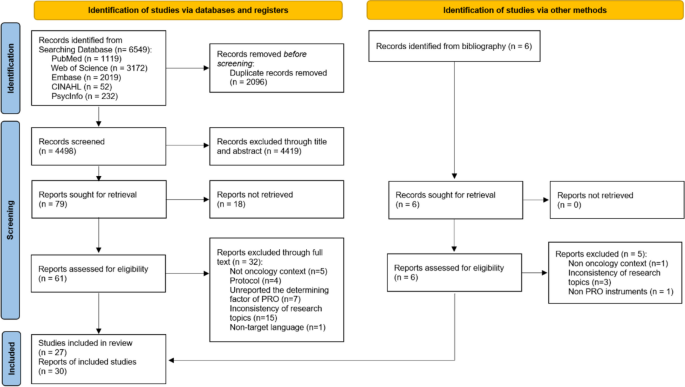

Some reviews require a critical appraisal for each study that makes it through the screening process. This involves a risk of bias assessment and/or a quality assessment. The goal of these reviews is not just to find all of the studies, but to determine their methodological rigor, and therefore, their credibility.

"Critical appraisal is the balanced assessment of a piece of research, looking for its strengths and weaknesses and them coming to a balanced judgement about its trustworthiness and its suitability for use in a particular context." 1

It's important to consider the impact that poorly designed studies could have on your findings and to rule out inaccurate or biased work.

Selection of a valid critical appraisal tool, testing the tool with several of the selected studies, and involving two or more reviewers in the appraisal are good practices to follow.

1. Purssell E, McCrae N. How to Perform a Systematic Literature Review: A Guide for Healthcare Researchers, Practitioners and Students. 1st ed. Springer ; 2020.

Evaluation Tools

- The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation Instrument (AGREE II) The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation Instrument (AGREE II) was developed to address the issue of variability in the quality of practice guidelines.

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM). Critical Appraisal Tools "contains useful tools and downloads for the critical appraisal of different types of medical evidence. Example appraisal sheets are provided together with several helpful examples."

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Checklists Critical Appraisal checklists for many different study types

- Critical Review Form for Qualitative Studies Version 2, developed out of McMaster University

- Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS) Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, et al. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016;6:e011458. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458

- Downs & Black Checklist for Assessing Studies Downs, S. H., & Black, N. (1998). The Feasibility of Creating a Checklist for the Assessment of the Methodological Quality Both of Randomised and Non-Randomised Studies of Health Care Interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (1979-), 52(6), 377–384.

- GRADE The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group "has developed a common, sensible and transparent approach to grading quality (or certainty) of evidence and strength of recommendations."

- Grade Handbook Full handbook on the GRADE method for grading quality of evidence.

- MAGIC (Making GRADE the Irresistible choice) Clear succinct guidance in how to use GRADE

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools "JBI’s critical appraisal tools assist in assessing the trustworthiness, relevance and results of published papers." Includes checklists for 13 types of articles.

- Latitudes Network This is a searchable library of validity assessment tools for use in evidence syntheses. This website also provides access to training on the process of validity assessment.

- Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool A tool that can be used to appraise a mix of studies that are included in a systematic review - qualitative research, RCTs, non-randomized studies, quantitative studies, mixed methods studies.

- RoB 2 Tool Higgins JPT, Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Hróbjartsson A, Boutron I, Reeves B, Eldridge S. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials In: Chandler J, McKenzie J, Boutron I, Welch V (editors). Cochrane Methods. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 10 (Suppl 1). dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD201601.

- ROBINS-I Risk of Bias for non-randomized (observational) studies or cohorts of interventions Sterne J A, Hernán M A, Reeves B C, Savović J, Berkman N D, Viswanathan M et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions BMJ 2016; 355 :i4919 doi:10.1136/bmj.i4919

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Critical Appraisal Notes and Checklists "Methodological assessment of studies selected as potential sources of evidence is based on a number of criteria that focus on those aspects of the study design that research has shown to have a significant effect on the risk of bias in the results reported and conclusions drawn. These criteria differ between study types, and a range of checklists is used to bring a degree of consistency to the assessment process."

- The TREND Statement (CDC) Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N, and the TREND Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: The TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:361-366.

- Assembling the Pieces of a Systematic Reviews, Chapter 8: Evaluating: Study Selection and Critical Appraisal.

- How to Perform a Systematic Literature Review, Chapter: Critical Appraisal: Assessing the Quality of Studies.

Other library guides

- Duke University Medical Center Library. Systematic Reviews: Assess for Quality and Bias

- UNC Health Sciences Library. Systematic Reviews: Assess Quality of Included Studies

- Last Updated: Oct 31, 2024 7:47 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/systematicreviews

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 25, Issue 1

- Critical appraisal of qualitative research: necessity, partialities and the issue of bias

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5660-8224 Veronika Williams ,

- Anne-Marie Boylan ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4597-1276 David Nunan

- Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences , University of Oxford, Radcliffe Observatory Quarter , Oxford , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Veronika Williams, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford OX2 6GG, UK; veronika.williams{at}phc.ox.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2018-111132

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

- qualitative research

Introduction

Qualitative evidence allows researchers to analyse human experience and provides useful exploratory insights into experiential matters and meaning, often explaining the ‘how’ and ‘why’. As we have argued previously 1 , qualitative research has an important place within evidence-based healthcare, contributing to among other things policy on patient safety, 2 prescribing, 3 4 and understanding chronic illness. 5 Equally, it offers additional insight into quantitative studies, explaining contextual factors surrounding a successful intervention or why an intervention might have ‘failed’ or ‘succeeded’ where effect sizes cannot. It is for these reasons that the MRC strongly recommends including qualitative evaluations when developing and evaluating complex interventions. 6

Critical appraisal of qualitative research

Is it necessary.