Action Research

Ai generator.

Understanding and analyzing your actions is vital for self-improvement. It would help if you recognized how your actions affect your future. Examining your progress is called action research. This method applies to psychology, marketing, and education. Action research is used by teachers to find solutions to problem areas or formulate research plans for factors that need improvement. The results of action research are useful to the participants since it helps them better themselves for the next tasks. This research has guaranteed relevance because the researchers get to decide what the focus of the study is. They are also the ones who will make use of the results.

Every action someone makes has a ripple effect on the future. One small act of kindness can lead to great fortunes. Likewise, any lousy act can turn into something terrible. A person’s mistakes are what makes him who he is today. Ziad K. Abdelnour even said, “Never erase your past. It shapes who you are today and will help you to be the person you’ll be tomorrow.” For one to grow as a person, one needs to be able to recognize one’s mistakes and learn from them. Perhaps you need to create an action plan or conduct action research to help yourself out.

The Power of Three

Not all types of research are useful for all fields; some are effective only on specific studies. Luckily, action research can serve many disciplines. Although most applicable to educational research settings, the action research design works for an endless variation of studies. This research approach can also be used by individuals or by groups of researchers. The difference in researchers also signifies a difference in purpose.

Reflective Practitioner When an individual practitioner decides to look into his way of teaching, he unconsciously analyzes his actions to improve the instruction. The more he studies himself, the more he masters the science and process of it all.

Large-Scale Progress In education, as the school progresses, the students progress with it. That is why many schools continuously seek ways to strengthen their instruction to build schoolwide improvement. When instructors come together to fix a single issue, organizational growth is bound to occur.

Professional Culture Medical and educational professionals don’t always agree on particular methods. Sometimes they need to do what they think is appropriate. The only important thing is that they lean towards the same organizational goal . With their differing approaches, they can share their own discoveries to their colleagues, making for more holistic improvement.

13+ Action Research Examples

The best way to improve yourself is by analyzing your actions and making adjustments along the way. This is a research method called action research. To help you further understand what action research is, here are multiple action research examples you can check out.

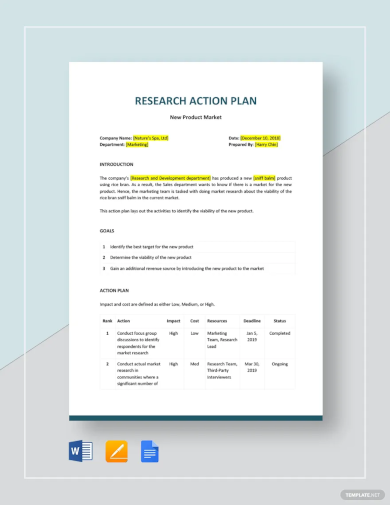

1. Research Action Plan Template

- Google Docs

- Apple Pages

Size: 63 KB

2. Research Corrective Action Plan Template

Size: 26 KB

3. Research Project Action Plan Template

Size: 32 KB

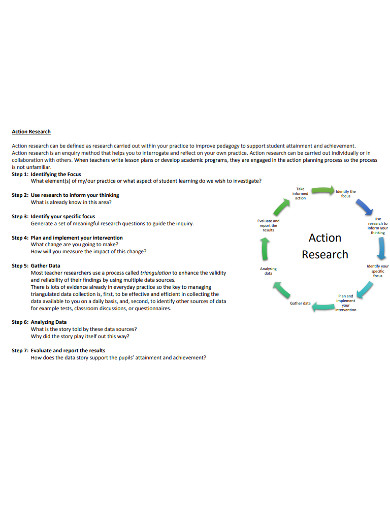

4. Sample Action Research Example

Size: 260 KB

5. Action Orientation Research Example

Size: 296 KB

6. Art Article Action Research Example

Size: 179 KB

7. Basic Action Research Example

Size: 327 KB

8. Five Phases of Action Research Example

Size: 61 KB

9. Standard Action Research Example

Size: 182 KB

10. Action Research in Teacher Education Example

Size: 263 KB

11. Action Research Support Notes Example

Size: 441 KB

12. Handbook for Action Research Example

13. Action Research in PDF

Size: 52 KB

14. Action Research for Professional Development Example

Size: 25 KB

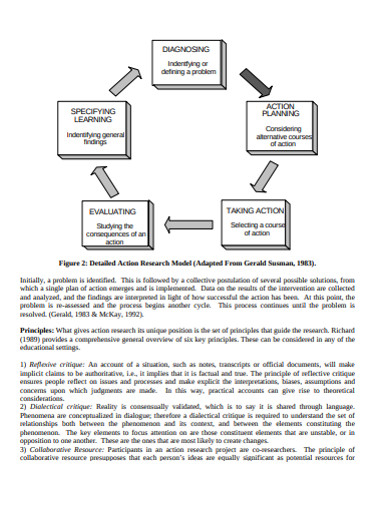

Segments of a Cycle

Action research is an approach that lets an individual study one’s action to help enhance their basic skills and knowledge of a given task or topic. There is a cycle that this research follows to make continuous improvements to a group or individual. As with any research projects, there are steps you need to follow to accomplish your project goals.

1. Selecting Focus

The action research cycle begins with identifying an area that you think needs improvement. Only the researcher can assess if the research focus is worth the time. The outcome of the focus should be the betterment of a practitioner’s work. Thus, picking the right center is extremely important.

2. Clarifying Theories

The next step is figuring out what approach works best for the problem area. You can try out different methods to solve your problem. This way, you can identify what process flow you are going to follow for the duration of the research. Studying various methods, beliefs, and theories can help you decide what you feel is most effective.

3. Collecting data

Your data should be valid and reliable to guarantee improvement. That is why it would be wrong to just stick to one source of data. If you can find various academic references to answer any of your questions, you should utilize them. This way, you can match the right technique with the unique qualities your research holds.

4. Analyzing Data

When conducting data analysis , you need not use complex calculations and statistical methods; you just need to examine the data you have collected. In studying the patterns and trends in your research data, you just need to answer two questions. What story does the data tell? Why is the story executed this way?

In a day, teachers face more students than fellow teachers. That’s why, given a chance to speak with their colleagues, teachers make share their discoveries from their research. This way, they get to express organizational knowledge they think is useful for other teachers while gaining insight as well.

The last step of the research action plan is, of course, to take action. This part is where teachers make their lesson plans . This part is satisfying to teachers because they feel they have gotten wiser with every piece of knowledge they have uncovered.

Everyone should learn from their mistakes. With every trial and error is a new way of looking at things. You just need to be vigilant with all your actions and know that there is always a better way of doing things. Once you’ve refined your skills, you are sure to become a master.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Action Research: What it is, Types, Stages & Examples

The best way to get things accomplished is to do it yourself. This statement is utilized in corporations, community projects, and national governments. These organizations are relying on action research to cope with their continuously changing and unstable environments as they function in a more interdependent world.

By engaging in cycles of planning, observation, action, and reflection, action research enables participants to identify challenges, implement solutions, and evaluate outcomes. This approach generates practical knowledge and empowers individuals and organizations to effect meaningful change in their contexts.

In practical educational contexts, this involves using systematic inquiry and reflective practice to address real-world challenges, improve teaching and learning, enhance student engagement, and drive positive changes within the educational system .

What is Action Research?

Action research is a strategy that tries to find realistic solutions to organizations’ difficulties and issues. It is similar to applied research.

Action research refers basically learning by doing. First, a problem is identified, then some actions are taken to address it, then how well the efforts worked are measured, and if the results are not satisfactory, the steps are applied again.

It can be put into three different groups:

- Positivist: This type of research is also called “classical action research.” It considers research a social experiment. This research is used to test theories in the actual world.

- Interpretive: This kind of research is called “contemporary action research.” It thinks that business reality is socially made, and when doing this research , it focuses on the details of local and organizational factors.

- Critical: This action research cycle takes a critical reflection approach to corporate systems and tries to enhance them.

Important Types of Action Research

Here are the main types of action research:

1. Practical Action Research

It focuses on solving specific problems within a local context, often involving teachers or practitioners seeking to improve practices.

2. Participatory Action Research (PAR)

A research process in which people, staff, and activists work together to generate knowledge from a study on an issue that adds value and supports their actions for social change.

3. Critical Action Research

Built to address power and social injustices in light of the Hegemonic Underpinnings, this research facilitates a callback, self-reflection, and thorough societal reformations.

4. Collaborative Action Research

In this form of research, a team of practitioners joins to do project work as part of an overall effort to improve. The work continues into the analysis phase with these same folks across all stages.

5. Reflective Action Research

This kind of research emphasizes individual or group reflection on practices. The key to this model is that it encourages reflective and deliberate practice, thus promoting learning and unfolding within ongoing experiences.

6. Transformative Action Research

This model empowers participants to address issues within their communities related to social justice and transformation.

Each type serves different contexts and goals, contributing to the overall effectiveness of action research.

Stages of Action Research

All research is about learning new things. Collaborative action research contributes knowledge based on investigations in particular and frequently useful circumstances. It starts with identifying a problem. After that, the research process is followed by the below stages:

Stage 1: Plan

For an action research project to go well, the researcher needs to plan it well. After coming up with an educational research topic or question after a research study, the first step is to develop an action plan to guide the research process. The research design aims to address the study’s question. The research strategy outlines what to undertake, when, and how.

Stage 2: Act

The next step is implementing the plan and gathering data. At this point, the researcher must select how to collect and organize research data . The researcher also needs to examine all tools and equipment before collecting data to ensure they are relevant, valid, and comprehensive.

Stage 3: Observe

Data observation is vital to any investigation. The action researcher needs to review the project’s goals and expectations before data observation . This is the final step before drawing conclusions and taking action.

Different kinds of graphs, charts, and networks can be used to represent the data. It assists in making judgments or progressing to the next stage of observing.

Stage 4: Reflect

This step involves applying a prospective solution and observing the results. It’s essential to see if the possible solution found through research can really solve the problem being studied.

The researcher must explore alternative ideas when the action research project’s solutions fail to solve the problem.

The Steps of Conducting Action Research

Action research is a systematic approach researchers, educators, and practitioners use to identify and address problems or challenges within a specific context. It involves a cyclical process of planning, implementing, reflecting, and adjusting actions based on the data collected. Here are the general steps involved in conducting an action research process:

Identify the action research question or problem

1. Identify The Action Research Question or Problem

Clearly define the issue or problem you want to address through your research. It should be specific, actionable, and relevant to your working context.

2. Review Existing Knowledge

Conduct a literature review to understand what research has already been done on the topic. This will help you gain insights, identify gaps, and inform your research design .

3. Plan The Research

Develop a research plan outlining your study’s objectives, methods, data collection tools , and timeline. Determine the scope of your research and the participants or stakeholders involved.

4. Collect Data

Implement your research plan by collecting relevant data. This can involve various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, document analysis, or focus groups . Ensure that your data collection methods align with your research objectives and allow you to gather the necessary information.

5. Analyze The Data

Once you have collected the data, analyze it using appropriate qualitative or quantitative techniques. Look for patterns, themes, or trends in the data that can help you understand the problem better.

6. Reflect on The Findings

Reflect on the analyzed data and interpret the results in the context of your research question. Consider the implications and possible solutions that emerge from the data analysis. This reflection phase is crucial for generating insights and understanding the underlying factors contributing to the problem.

7. Develop an Action Plan

Based on your analysis and reflection, develop an action plan that outlines the steps you will take to address the identified problem. The plan should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART goals). Consider involving relevant stakeholders in planning to ensure their buy-in and support.

8. Implement The Action Plan

Put your action plan into practice by implementing the identified strategies or interventions. This may involve making changes to existing practices, introducing new approaches, or testing alternative solutions. Document the implementation process and any modifications made along the way.

9. Evaluate and Monitor Progress

Continuously monitor and evaluate the impact of your actions. Collect additional data, assess the effectiveness of the interventions, and measure progress towards your goals. This evaluation will help you determine if your actions have the desired effects and inform any necessary adjustments.

10. Reflect and Iterate

Reflect on the outcomes of your actions and the evaluation results. Consider what worked well, what did not, and why. Use this information to refine your approach, make necessary adjustments, and plan for the next cycle of action research if needed.

Remember that participatory action research is an iterative process, and multiple cycles may be required to achieve significant improvements or solutions to the identified problem. Each cycle builds on the insights gained from the previous one, fostering continuous learning and improvement.

Explore Insightfully Contextual Inquiry in Qualitative Research

Examples of Action Research

Here are two real-life examples of action research.

Action research initiatives are frequently situation-specific. Still, other researchers can adapt the techniques. The example is from a researcher’s (Franklin, 1994) report about a project encouraging nature tourism in the Caribbean.

In 1991, this was launched to study how nature tourism may be implemented on the four Windward Islands in the Caribbean: St. Lucia, Grenada, Dominica, and St. Vincent.

For environmental protection, a government-led action study determined that the consultation process needs to involve numerous stakeholders, including commercial enterprises.

First, two researchers undertook the study and held search conferences on each island. The search conferences resulted in suggestions and action plans for local community nature tourism sub-projects.

Several islands formed advisory groups and launched national awareness and community projects. Regional project meetings were held to discuss experiences, self-evaluations, and strategies. Creating a documentary about a local initiative helped build community. And the study was a success, leading to a number of changes in the area.

Lau and Hayward (1997) employed action research to analyze Internet-based collaborative work groups.

Over two years, the researchers facilitated three action research problem -solving cycles with 15 teachers, project personnel, and 25 health practitioners from diverse areas. The goal was to see how Internet-based communications might affect their virtual workgroup.

First, expectations were defined, technology was provided, and a bespoke workgroup system was developed. Participants suggested shorter, more dispersed training sessions with project-specific instructions.

The second phase saw the system’s complete deployment. The final cycle witnessed system stability and virtual group formation. The key lesson was that the learning curve was poorly misjudged, with frustrations only marginally met by phone-based technical help. According to the researchers, the absence of high-quality online material about community healthcare was harmful.

Role clarity, connection building, knowledge sharing, resource assistance, and experiential learning are vital for virtual group growth. More study is required on how group support systems might assist groups in engaging with their external environment and boost group members’ learning.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Action Research

Action research has both good and bad points.

- It is very flexible, so researchers can change their analyses to fit their needs and make individual changes.

- It offers a quick and easy way to solve problems that have been going on for a long time instead of complicated, long-term solutions based on complex facts.

- If It is done right, it can be very powerful because it can lead to social change and give people the tools to make that change in ways that are important to their communities.

Disadvantages

- These studies have a hard time being generalized and are hard to repeat because they are so flexible. Because the researcher has the power to draw conclusions, they are often not thought to be theoretically sound.

- Setting up an action study in an ethical way can be hard. People may feel like they have to take part or take part in a certain way.

- It is prone to research errors like selection bias , social desirability bias, and other cognitive biases.

Why QuestionPro Research Suite is Great for Action Research?

QuestionPro Research Suite is an ideal choice for action research, which typically involves multiple rounds of data collection , analysis, and intervention cycles. This is one reason it might be great for that:

01. Data Collection

QuestionPro offers flexible and adaptable methods for data dissemination. You can collect and store crucial business data from secure, personalized questionnaires , and distribute them through emails, SMSs, or even popular social media platforms and mobile apps.

This adaptability is particularly useful for action research, which often requires a variety of data collection techniques.

02. Advanced Analysis Tools

- Efficient Data Analysis: Built-in tools simplify both quantitative and qualitative analysis.

- Powerful Segmentation: Cross-tabulation lets you compare and track changes across cycles.

- Reliable Insights: This robust toolset enhances confidence in research outcomes.

03. Collaboration and Real-Time Reporting

Multiple researchers can collaborate within the platform, sharing permissions and changes in real-time while creating reports. Asynchronous collaboration: Conversation threads and comments can be in one place, ensuring all team members stay updated and are aligned with stakeholders throughout each action research phase.

04. User-Friendly Interface

At the user level, what kind of data visualization charts/graphs, tables, etc., should be provided to visualize the complex findings most often done through these)? Across all solutions, we need fully customizable dashboards to offer perfect vision to different people so they can make decisions and take action based on this data.

05. Automation and Integration Capabilities

- Workflow Automation: Enables recurring surveys or updates to run seamlessly.

- Time Savings: Frees up time in long-term research projects.

- Integrations: Connects with popular CRMs and other applications.

- Simplified Data Addition: This makes incorporating data from external sources easy.

These features make QuestionPro Research Suite a powerful tool for action research. It makes it easy to manage data, conduct analyses, and drive actionable insights through iterative research cycles.

Action research is a dynamic and participatory approach that empowers individuals and communities to address real-world challenges through systematic inquiry and reflection.

The methods used in action research help gather valuable insights and foster continuous improvement, leading to meaningful change across various fields. By promoting iterative cycles, action research generates knowledge and encourages a culture of learning and adaptation, making it a crucial tool for driving transformation.

At QuestionPro, we give researchers tools for collecting data, like our survey software, and a library of insights for any long-term study. Go to the Research Suite if you want to see a demo or learn more about it.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

Frequently Asked Questions(FAQ’s)

Action research is a systematic approach to inquiry that involves identifying a problem or challenge in a practical context, implementing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, and using the findings to inform decision-making and drive positive change.

Action research can be conducted by various individuals or groups, including teachers, administrators, researchers, and educational practitioners. It is often carried out by those directly involved in the educational setting where the research takes place.

The steps of action research typically include identifying a problem, reviewing relevant literature, designing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, reflecting on findings, and implementing improvements based on the results.

MORE LIKE THIS

Maximize Employee Feedback with QuestionPro Workforce’s Slack Integration

Nov 6, 2024

2024 Presidential Election Polls: Harris vs. Trump

Nov 5, 2024

Your First Question Should Be Anything But, “Is The Car Okay?” — Tuesday CX Thoughts

QuestionPro vs. Qualtrics: Who Offers the Best 360-Degree Feedback Platform for Your Needs?

Nov 4, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

IMAGES

VIDEO